Vortigern Gwrtheneu on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Vortigern (; owl, Guorthigirn, ; cy, Gwrtheyrn; ang, Wyrtgeorn;

Vortigern (; owl, Guorthigirn, ; cy, Gwrtheyrn; ang, Wyrtgeorn;

The '' Historia Brittonum'' (History of the Britons) was attributed until recently to

The '' Historia Brittonum'' (History of the Britons) was attributed until recently to

/ref> The ''Historia Brittonum'' relates four battles occurring in Kent, apparently related to material in the ''

The story of Vortigern adopted its best-known form in Geoffrey's pseudohistorical '' Historia Regum Britanniae''. Geoffrey names Constans the older brother of

The story of Vortigern adopted its best-known form in Geoffrey's pseudohistorical '' Historia Regum Britanniae''. Geoffrey names Constans the older brother of

/ref>

''Vortigern Studies'' website

* {{Authority control 5th-century English monarchs 5th-century Welsh monarchs Arthurian characters Arthurian legend English folklore English mythology House of Gwertherion Legendary British kings Merlin People whose existence is disputed Sub-Roman monarchs Welsh folklore Welsh mythology

Vortigern (; owl, Guorthigirn, ; cy, Gwrtheyrn; ang, Wyrtgeorn;

Vortigern (; owl, Guorthigirn, ; cy, Gwrtheyrn; ang, Wyrtgeorn; Old Breton

Breton (, ; or in Morbihan) is a Southwestern Brittonic language of the Celtic language family spoken in Brittany, part of modern-day France. It is the only Celtic language still widely in use on the European mainland, albeit as a member of t ...

: ''Gurdiern'', ''Gurthiern''; gle, Foirtchern; la, Vortigernus, , , etc.), also spelled Vortiger, Vortigan, Voertigern and Vortigen, was a 5th-century warlord in Britain, known perhaps as a king of the Britons

The title King of the Britons ( cy, Brenin y Brythoniaid, la, Rex Britannorum) was used (often retrospectively) to refer to the most powerful ruler among the Celtic Britons, both before and after the period of Roman Britain up until the Norma ...

or at least connoted as such in the writings of Bede

Bede ( ; ang, Bǣda , ; 672/326 May 735), also known as Saint Bede, The Venerable Bede, and Bede the Venerable ( la, Beda Venerabilis), was an English monk at the monastery of St Peter and its companion monastery of St Paul in the Kingdom o ...

and Gildas. His existence is contested by scholars and information about him is obscure.

He may have been the "superbus tyrannus" said to have invited Hengist and Horsa to aid him in fighting the Picts and the Scots, whereupon they revolted, killing his son in the process and forming the Kingdom of Kent. It is said that he took refuge in North Wales, and that his grave was in Dyfed or the Llŷn Peninsula. Gildas later denigrated Vortigern for his misjudgement and also blamed him for the loss of Britain. He is cited at the beginning of the genealogy of the early Kings of Powys

Before the Conquest of Wales by Edward I, Conquest of Wales, completed in 1282, Wales consisted of a number of independent monarchy, kingdoms, the most important being Kingdom of Gwynedd, Gwynedd, Kingdom of Powys, Powys, Deheubarth (originally ...

.

Medieval accounts

Gildas

The 6th-century cleric and historian Gildas wrote '' De Excidio et Conquestu Britanniae'' ( en, On the Ruin and Conquest of Britain) in the first decades of the 6th century. In Chapter 23, he tells how "all the councillors, together with ''that proud usurper''" 'omnes consiliarii una cum superbo tyranno''made the mistake of inviting "the fierce and impious Saxons" to settle in Britain. According to Gildas, apparently, a small group came at first and was settled "on the eastern side of the island, by the invitation of the unlucky 'infaustus''usurper". This small group invited more of their countrymen to join them, and the colony grew. Eventually the Saxons demanded that "their monthly allotments" be increased and, when their demands were eventually refused, broke their treaty and plundered the lands of the Romano-British. It is not clear whether Gildas used the name Vortigern. Most editions published currently omit the name. Two manuscripts name him: ''MS. A'' (Avranches MS 162, 12th century), refers to ''Uortigerno''; and ''Mommsen's MS. X'' (Cambridge University Library MS. Ff. I.27) (13th century) calls him ''Gurthigerno''. Gildas never addresses Vortigern as the king of Britain. He is termed a usurper (''tyrannus''), but not solely responsible for inviting the Saxons. To the contrary, he is portrayed as being aided by or aiding a "Council", which may be a government based on the representatives of all the "cities" (''civitates'') or a part thereof. Gildas also does not consider Vortigern as bad; he simply qualifies him as "unlucky" (''infaustus'') and lacking judgement, which is understandable, as these mercenaries proved to be faithless. Gildas adds several small details that suggest either he or his source received at least part of the story from the Anglo-Saxons. The first is when he describes the size of the initial party of Saxons, stating that they came in three (or "keels"), "as they call ships of war". This may be the earliest recovered word of English. The second detail is his repetition that the visiting Saxons were "told by a certain soothsayer among them, that they should occupy the country to which they were sailing three hundred years, and half of that time, a hundred and fifty years, should plunder and despoil the same." Both of these details are unlikely to have been invented by a Roman or Brittonic source. Modern scholars have debated the various details of Gildas' story. One topic of discussion has been about the words Gildas uses to describe the Saxons' subsidies (''annonas'', ''epimenia'') and whether they are legal terms used in a treaty of ''foederati

''Foederati'' (, singular: ''foederatus'' ) were peoples and cities bound by a treaty, known as ''foedus'', with Rome. During the Roman Republic, the term identified the ''socii'', but during the Roman Empire, it was used to describe foreign stat ...

'', a late Roman political practice of settling allied barbarian peoples within the boundaries of the empire to furnish troops to aid the defence of the empire. Gildas describes how their raids took them "sea to sea, heaped up by the eastern band of impious men; and as it devastated all the neighbouring cities and lands, did not cease after it had been kindled, until it burnt nearly the whole surface of the island, and licked the western ocean with its red and savage tongue" (chapter 24).

Bede

The first extant text considering Gildas' account isBede

Bede ( ; ang, Bǣda , ; 672/326 May 735), also known as Saint Bede, The Venerable Bede, and Bede the Venerable ( la, Beda Venerabilis), was an English monk at the monastery of St Peter and its companion monastery of St Paul in the Kingdom o ...

, writing in the early- to mid-8th century. He mostly paraphrases Gildas in his '' Ecclesiastical History of the English People'' and '' The Reckoning of Time'', adding several details, perhaps most importantly the name of this "proud tyrant", whom he first calls ''Vertigernus'' (in his ) and later ''Vurtigernus'' (in his ). The ''Vertigernus'' form may reflect an earlier Celtic

Celtic, Celtics or Keltic may refer to:

Language and ethnicity

*pertaining to Celts, a collection of Indo-European peoples in Europe and Anatolia

**Celts (modern)

*Celtic languages

**Proto-Celtic language

* Celtic music

*Celtic nations

Sports Fo ...

source or a lost version of Gildas. Bede also gives names in the to the leaders of the Saxons, Hengist and Horsa, specifically identifying their tribes as the Saxons, Angles and Jutes (''H.E.'', 1.14–15). Another significant detail that Bede adds to Gildas' account is calling Vortigern the king of the British people.

Bede also supplies the date, 449, which was traditionally accepted but has been considered suspect since the late 20th century: "Marcian

Marcian (; la, Marcianus, link=no; grc-gre, Μαρκιανός, link=no ; 392 – 27 January 457) was Roman emperor of the East from 450 to 457. Very little of his life before becoming emperor is known, other than that he was a (personal as ...

being made emperor with Valentinian, and the forty-sixth from Augustus, ruled the empire seven years." Michael Jones notes that there are several arrival dates in Bede. In H.E. 1.15 the arrival occurs within the period 449–455; in 1.23 and 5.23 another date, c. 446, is given; and in 2.14 the same event is dated 446 or 447, suggesting that these dates are calculated approximations.

''Historia Brittonum''

The '' Historia Brittonum'' (History of the Britons) was attributed until recently to

The '' Historia Brittonum'' (History of the Britons) was attributed until recently to Nennius

Nennius – or Nemnius or Nemnivus – was a Welsh monk of the 9th century. He has traditionally been attributed with the authorship of the ''Historia Brittonum'', based on the prologue affixed to that work. This attribution is widely considered ...

, a monk from Bangor, Gwynedd

Bangor (; ) is a cathedral city and community

A community is a social unit (a group of living things) with commonality such as place, norms, religion, values, customs, or identity. Communities may share a sense of place situated ...

, and was probably compiled during the early 9th century. The writer mentions a great number of sources. Nennius wrote more negatively of Vortigern, accusing him of incest (perhaps confusing Vortigern with the Welsh king Vortiporius, accused by Gildas of the same crime), oath-breaking, treason, love for a pagan woman, and lesser vices such as pride.

The ''Historia Brittonum'' recounts many details about Vortigern and his sons. Chapters 31–49 tell how Vortigern (Guorthigirn) deals with the Saxons and Saint Germanus of Auxerre. Chapters 50–55 deal with Saint Patrick

Saint Patrick ( la, Patricius; ga, Pádraig ; cy, Padrig) was a fifth-century Romano-British Christian missionary and bishop in Ireland. Known as the "Apostle of Ireland", he is the primary patron saint of Ireland, the other patron saints be ...

. Chapter 56 tells about King Arthur and his battles. Chapters 57–65 mention English genealogies, mingled with English and Welsh history

The history of what is now Wales () begins with evidence of a Neanderthal presence from at least 230,000 years ago, while ''Homo sapiens'' arrived by about 31,000 BC. However, continuous habitation by modern humans dates from the period after ...

. Chapter 66 gives important chronological calculations, mostly on Vortigern and the Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain.

Excluding what is taken from Gildas, there are a number of traditions:

* Material quoted from a ''Life of Saint Germanus''. These excerpts describe Germanus of Auxerre's incident with one Benlli

King Benlli was a British king who ruled part of what is now Wales in the early 5th century. He is notorious for opposing Saint Germanus and was probably a heretical follower of Pelagianism. The story of his admonishment by the saint and eventua ...

, an inhospitable host seemingly unrelated to Vortigern who comes to an untimely end, but his servant provides hospitality and is made the progenitor of the kings of Powys. They also describe Vortigern's son by his own daughter, whom Germanus raises, and Vortigern's own end caused by fire from heaven.

It has been suggested that the saint mentioned here may be no more than a local saint or a tale that had to explain all the holy places dedicated to a St. Germanus or a "Garmon", who may have been a Powys saint or even a bishop from the Isle of Man about the time of writing the ''Historia Brittonum''. The story seems only to be explained as a slur against the rival dynasty of Powys, suggesting that they did not descend from Vortigern but from a mere slave.

* A number of calculations attempting to fix the year when Vortigern invited the Saxons into Britain. These are made by the writer, naming interesting persons and calculating their dates, making several mistakes in the process.

* Genealogical material about Vortigern's ancestry, including the names of his four sons (Vortimer, Pascent, Catigern, and Faustus), his father Vitalis, his grandfather Vitalinus, and his great-grandfather Gloui, who is probably just an eponym which associates Vortigern with Glevum, the civitas of Gloucester.

* The story of why Vortigern granted land in Britain to the Saxons, first to Thanet in exchange for service as ''foederati'' troops, then to the rest of Kent in exchange for marriage to Hengest's daughter, then to Essex and Sussex

Sussex (), from the Old English (), is a historic county in South East England that was formerly an independent medieval Anglo-Saxon kingdom. It is bounded to the west by Hampshire, north by Surrey, northeast by Kent, south by the English ...

after a banquet where the Saxons treacherously slew all of the leaders of the British but saved Vortigern to extract this ransom.

* The tale of Ambrosius Aurelianus and the two dragons found beneath Dinas Emrys.Lupack, Alan. "Vortigern", The Camelot Project, University of Rochester/ref> The ''Historia Brittonum'' relates four battles occurring in Kent, apparently related to material in the ''

Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

The ''Anglo-Saxon Chronicle'' is a collection of annals in Old English, chronicling the history of the Anglo-Saxons. The original manuscript of the ''Chronicle'' was created late in the 9th century, probably in Wessex, during the reign of Alf ...

'' (see below). It claims that Vortigern's son Vortimer commanded the Britons against Hengest's Saxons. Moreover, it claims that the Saxons were driven out of Britain, only to return at Vortigern's invitation a few years later, after the death of Vortimer.

The stories preserved in the ''Historia Brittonum'' reveal an attempt by one or more anonymous British scholars to provide more detail to this story, while struggling to accommodate the facts of the British tradition.

The ''Anglo-Saxon Chronicle''

The ''Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

The ''Anglo-Saxon Chronicle'' is a collection of annals in Old English, chronicling the history of the Anglo-Saxons. The original manuscript of the ''Chronicle'' was created late in the 9th century, probably in Wessex, during the reign of Alf ...

'' provides dates and locations of four battles which Hengest and his brother Horsa fought against the British in the county of Kent. Vortigern is said to have been the commander of the British for only the first battle; the opponents in the next three battles are variously termed " British" and " Welsh", which is not unusual for this part of the ''Chronicle''. The ''Chronicle'' locates the Battle of Wippedesfleot

The Battle of Wippedesfleot was a battle in 466 between the Anglo-Saxons (or Jutes), led by Hengest, and the Britons. It is described in the '' Anglo-Saxon Chronicle'' thus:

:465:

:465: Here Hengest and Æsc fought together against Welsh (= ...

as the place where the Saxons first landed, dated 465 in ''Wippedsfleot'' and thought to be Ebbsfleet near Ramsgate

Ramsgate is a seaside resort, seaside town in the district of Thanet District, Thanet in east Kent, England. It was one of the great English seaside towns of the 19th century. In 2001 it had a population of about 40,000. In 2011, according to t ...

. The year 455 is the last date when Vortigern is mentioned.

The annals for the 5th century in the ''Chronicle'' were put into their current form during the 9th century, probably during the reign of Alfred the Great

Alfred the Great (alt. Ælfred 848/849 – 26 October 899) was King of the West Saxons from 871 to 886, and King of the Anglo-Saxons from 886 until his death in 899. He was the youngest son of King Æthelwulf and his first wife Osburh, who bot ...

. The sources are obscure for the fifth century annals; however, an analysis of the text demonstrates some poetic conventions, so it is probable that they were derived from an oral tradition such as saga

is a series of science fantasy role-playing video games by Square Enix. The series originated on the Game Boy in 1989 as the creation of Akitoshi Kawazu at Square (video game company), Square. It has since continued across multiple platforms, ...

s in the form of epic poems.

There is dispute as to when the material was written which comprises the ''Historia Brittonum'', and it could be later than the ''Chronicle''. Some historians argue that the ''Historia Brittonum'' took its material from a source close to the ''Chronicle''.

William of Malmesbury

Writing soon before Geoffrey of Monmouth, William of Malmesbury added much to the unfavourable assessment of Vortigern: William does, however, add some detail, no doubt because of a good local knowledge, in ''De Gestis Regum Anglorum'' book I, chapter 23.Geoffrey of Monmouth

The story of Vortigern adopted its best-known form in Geoffrey's pseudohistorical '' Historia Regum Britanniae''. Geoffrey names Constans the older brother of

The story of Vortigern adopted its best-known form in Geoffrey's pseudohistorical '' Historia Regum Britanniae''. Geoffrey names Constans the older brother of Aurelius Ambrosius

Ambrosius Aurelianus ( cy, Emrys Wledig; Anglicised as Ambrose Aurelian and called Aurelius Ambrosius in the ''Historia Regum Britanniae'' and elsewhere) was a war leader of the Romano-British who won an important battle against the Anglo-Sax ...

and Uther Pendragon. After the death of their father, Constantinus III, Vortigern persuades Constans to leave his monastery and claim the throne. Constans proved a weak and unpopular puppet monarch and Vortigern ruled the country through him until he finally managed Constans' death by insurgent Picts.

Geoffrey mentions a similar tale just before that episode, however, which may be an unintentional duplication. Just after the Romans leave, the archbishop of London is put forward by the representatives of Britain to organise the island's defences. To do so, he arranges for continental soldiers to come to Britain. The name of the bishop is Guitelin, a name similar to the Vitalinus mentioned in the ancestry of Vortigern and to the Vitalinus said to have fought with Ambrosius at the Battle of Guoloph

The Battle of Guoloph, also known as the Battle of Wallop, took place in the 5th century. Various dates have been put forward: 440 AD by Alfred Anscombe, 437 AD according to John Morris, and 458 by Nikolai Tolstoy. It took place at what is now ...

. This Guithelin/Vitalinus disappears from the story as soon as Vortigern arrives. All these coincidences imply that Geoffrey duplicated the story of the invitation of the Saxons, and that the tale of Guithelinus the archbishop might possibly give some insight into the background of Vortigern before his acquisition of power.

Geoffrey identifies Hengest's daughter as Rowena. After Vortigern marries her, his sons rebel. Geoffrey adds that Vortigern was succeeded briefly by his son Vortimer, as does the ''Historia Brittonum'', only to assume the throne again when Vortimer is killed.

Pillar of Eliseg

The inscription on the Pillar of Eliseg, a mid-9th centurystone cross

Stone crosses (german: Steinkreuze) in Central Europe are usually bulky Christian monuments, some high and wide, that were almost always hewn from a single block of stone, usually granite, sandstone, limestone or basalt. They are amongst the ...

in Llangollen, northern Wales, gives the Old Welsh

Old Welsh ( cy, Hen Gymraeg) is the stage of the Welsh language from about 800 AD until the early 12th century when it developed into Middle Welsh.Koch, p. 1757. The preceding period, from the time Welsh became distinct from Common Brittonic ...

spelling of Vortigern: Guarthiern

Ern or ERN may refer to:

Transport

* Eirunepé Airport, in Brazil

* Engenho da Rainha Station, on the Rio de Janeiro Metro

* Ernakulam Town railway station, in Kerala, India

* Ernest Airlines, an Italian airline

Other uses

* Ern (given na ...

(the inscription is now damaged and the final letters of the name are missing), believed to be the same person as Gildas's "superbus tyrannus", Vortigern. The pillar also states that he was married to Sevira

Sevira (a Vulgar Latin spelling of the Classical Latin name ''Severa'') was a purported daughter of the Roman Emperor Magnus Maximus and wife of Vortigern. She was mentioned on the fragmentary, mid-ninth century C.E. Latin inscription of the Pill ...

, the daughter of Magnus Maximus, and gave a line of descent leading to the royal family of Powys, who erected the cross.

Vortigern as title rather than personal name

It has occasionally been suggested by scholars that Vortigern might be a royal title, rather than a personal name. The name in Brittonic literally means "Great King" or "Overlord", composed of the elements *''wor-'' "over-, super" and *''tigerno-'' "king, lord, chief, ruler" (compareOld Breton

Breton (, ; or in Morbihan) is a Southwestern Brittonic language of the Celtic language family spoken in Brittany, part of modern-day France. It is the only Celtic language still widely in use on the European mainland, albeit as a member of t ...

, Cornish a type of local ruler - literally "pledge chief") in medieval Brittany and Cornwall.

However, the element *''tigerno-'' was a regular one in Brittonic personal names (compare Kentigern

Kentigern ( cy, Cyndeyrn Garthwys; la, Kentigernus), known as Mungo, was a missionary in the Brittonic Kingdom of Strathclyde in the late sixth century, and the founder and patron saint of the city of Glasgow.

Name

In Wales and England, this s ...

, Catigern, Ritigern, Tigernmaglus, et al.) and, as *''wortigernos'' (or derivatives of it) is not attested as a common noun, there is no reason to suppose that it was used as anything other than a personal name (in fact, an Old Irish cognate of it, , was a fairly common personal name in medieval Ireland, further lending credence to the notion that Vortigern was a personal name and not a title).

Local legends

A valley on the north coast of the Llŷn Peninsula, known asNant Gwrtheyrn

Nant Gwrtheyrn is a Welsh Language and Heritage Centre, located near the village of Llithfaen on the northern coast of the Llŷn Peninsula, Gwynedd, in northwest Wales.

It is sometimes referred to as 'the Nant' and is named after the valley wh ...

or "Vortigern's Gorge", is named after Vortigern, and until modern times had a small barrow known locally as "Vortigern's Grave", along with a ruin known as "Vortigern's Fort". However, this conflicts with doubtful reports that he died in his castle on the River Teifi in Dyfed (''"Nennius"'') or his tower at The Doward

The Doward ( cy, Deuarth Fach, "two small hills"), is an area in the parish of Whitchurch in south Herefordshire, England, consisting of the hills of Little Doward and Great Doward and extensive woodland. It is within the Wye Valley Area of O ...

in Herefordshire (''Geoffrey of Monmouth'').

Other fortifications associated with Vortigern are at Arfon in Gwynedd

Gwynedd (; ) is a county and preserved county (latter with differing boundaries; includes the Isle of Anglesey) in the north-west of Wales. It shares borders with Powys, Conwy County Borough, Denbighshire, Anglesey over the Menai Strait, and C ...

, Bradford on Avon in Wiltshire, Carn Fadryn

Carn Fadryn, sometimes Carn Fadrun or Garn Fadryn, is a five-hectare Iron Age hillfort and is the name of the mountain on which the fort is situated. It lies in the centre of the Llŷn Peninsula, Gwynedd, and overlooks the village of Garnfadryn, ...

in Gwynedd, Clwyd

Clwyd ( , ) is a preserved county of Wales, situated in the north-east corner of the country; it is named after the River Clwyd, which runs through the area. To the north lies the Irish Sea, with the English ceremonial counties of Cheshire to ...

in Powys, Llandysul in Dyfed, Old Carlisle

Old Carlisle is a village in the civil parish of Westward in the Allerdale district of Cumbria

Cumbria ( ) is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in North West England, bordering Scotland. The county and Cumbria County Council, its ...

in Cumberland

Cumberland ( ) is a historic county in the far North West England. It covers part of the Lake District as well as the north Pennines and Solway Firth coast. Cumberland had an administrative function from the 12th century until 1974. From 19 ...

, Old Sarum in Wiltshire, Rhayader in Powys, Snowdon

Snowdon () or (), is the highest mountain in Wales, at an elevation of above sea level, and the highest point in the British Isles outside the Scottish Highlands. It is located in Snowdonia National Park (') in Gwynedd (historic ...

and Stonehenge

Stonehenge is a prehistoric monument on Salisbury Plain in Wiltshire, England, west of Amesbury. It consists of an outer ring of vertical sarsen standing stones, each around high, wide, and weighing around 25 tons, topped by connectin ...

in Wiltshire.vortigernstudies.org.uk/ref>

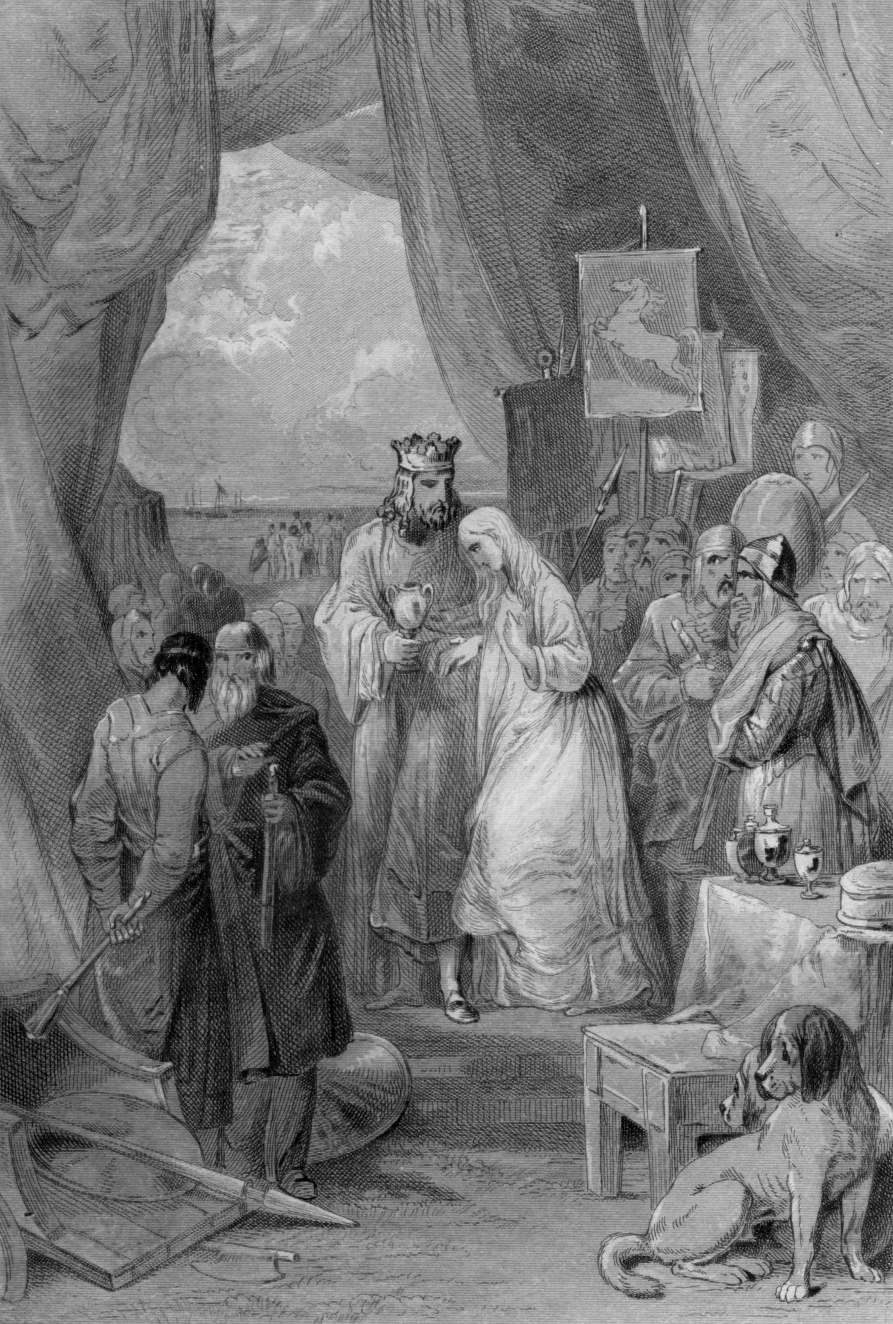

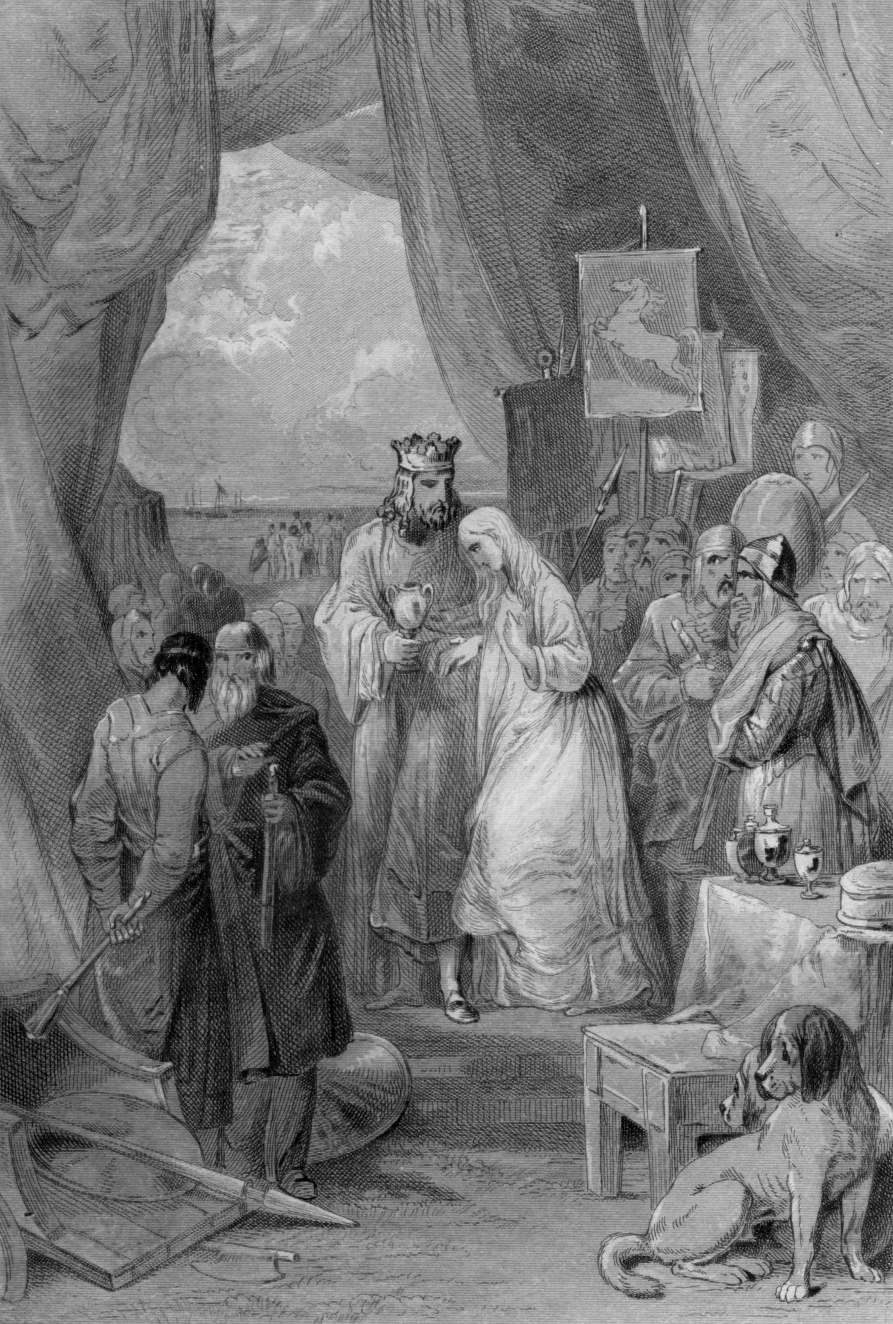

Later portrayals

Vortigern's story remained well known after the Middle Ages, especially in Great Britain. He is a major character in two Jacobean plays, the anonymous '' The Birth of Merlin'' and Thomas Middleton's '' Hengist, King of Kent'', first published in 1661. His meeting with Rowena became a popular subject in 17th-century engraving and painting, e.g. William Hamilton's 1793 work ''Vortigern and Rowena'' (above right). He was also featured in literature, such as John Lesslie Hall's poems about the beginnings of England. One of Vortigern's most notorious literary appearances is in the play '' Vortigern and Rowena'', which was promoted as a lost work of William Shakespeare when it first emerged in 1796. However, it was soon revealed as a literary forgery written by the play's purported discoverer, William Henry Ireland, who had previously forged a number of other Shakespearean manuscripts. The play was at first accepted as Shakespeare's by some in the literary community, and received a performance at London's Drury Lane Theatre on 2 April 1796. The play's crude writing, however, exposed it as a forgery, and it was laughed off stage and not performed again. Ireland eventually admitted to the hoax and tried to publish the play by his own name, but had little success.References

External links

''Vortigern Studies'' website

* {{Authority control 5th-century English monarchs 5th-century Welsh monarchs Arthurian characters Arthurian legend English folklore English mythology House of Gwertherion Legendary British kings Merlin People whose existence is disputed Sub-Roman monarchs Welsh folklore Welsh mythology