Virginia v. John Brown on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Virginia v. John Brown'' was a criminal trial held in

Brown faced a

Brown faced a

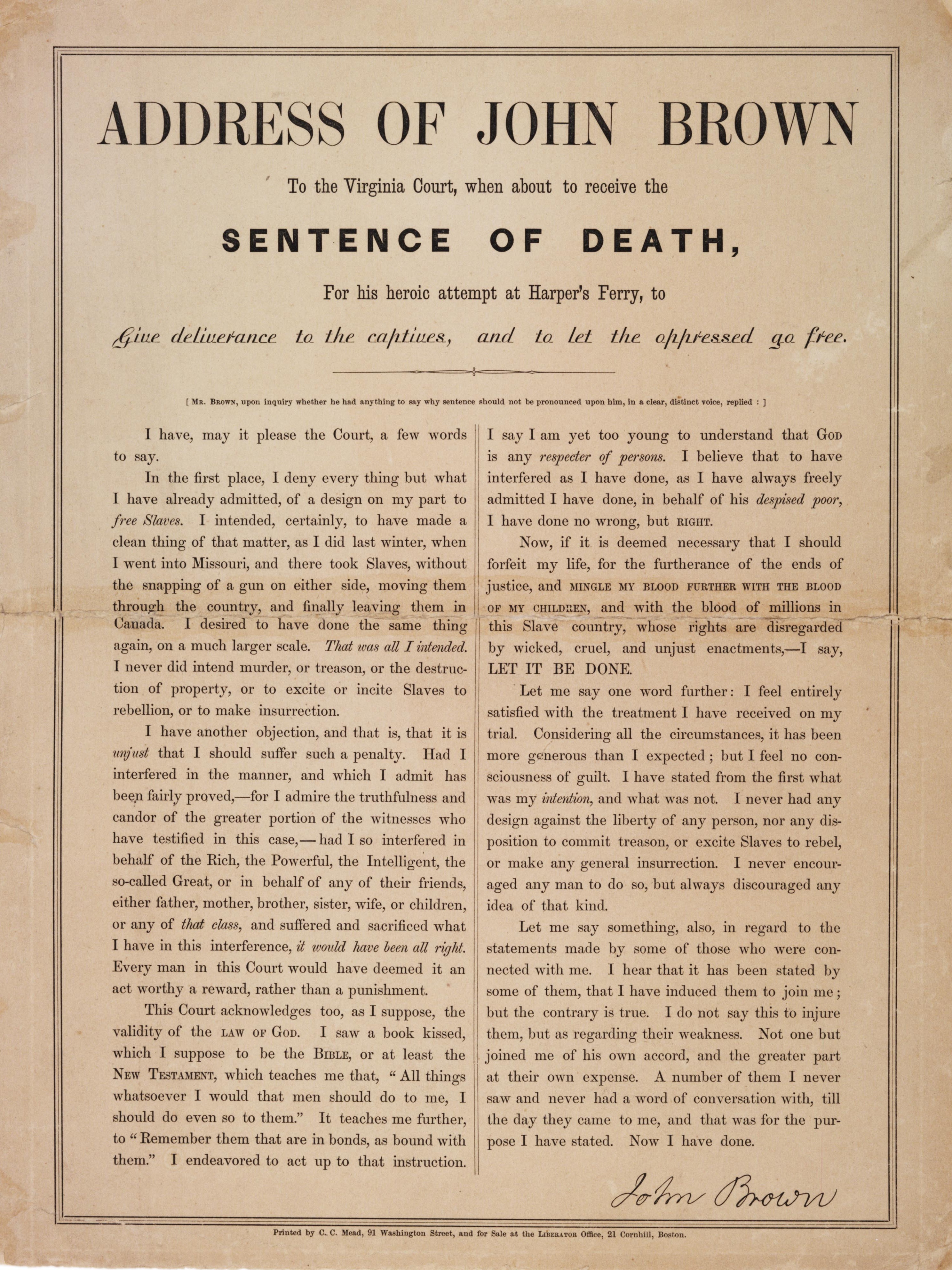

Brown's sentencing took place on November 2, 1859. As Virginia court procedure required, Brown was first asked to stand and say if there was reason sentence should not be passed upon him. He arosehe could now stand unassistedand made what his first biographer called " islast speech". He said his only goal was to free slaves, not start a revolt, that it was God's work, that if he had been helping the rich instead of the poor he would not be in court, and that the criminal trial had been more fair than he expected. According to

Brown's sentencing took place on November 2, 1859. As Virginia court procedure required, Brown was first asked to stand and say if there was reason sentence should not be passed upon him. He arosehe could now stand unassistedand made what his first biographer called " islast speech". He said his only goal was to free slaves, not start a revolt, that it was God's work, that if he had been helping the rich instead of the poor he would not be in court, and that the criminal trial had been more fair than he expected. According to

Brown made a second will, the morning of his execution, in which he authorized the Sheriff of Jefferson County to sell his pikes and guns, if they could be found, and give the money to his wife.

In his correspondence Brown mentioned several times how well he was treated by Avis, who was also in charge of Brown's execution and the one who put the noose around his neck. Avis was described by a visitor to the jail as Brown's friend. Brown's wife had arrived on November 30, and the couple had their last dinner with Avis's family in their apartment at the jail. That is where they last saw each other. According to Andrew Hunter,

Brown made a second will, the morning of his execution, in which he authorized the Sheriff of Jefferson County to sell his pikes and guns, if they could be found, and give the money to his wife.

In his correspondence Brown mentioned several times how well he was treated by Avis, who was also in charge of Brown's execution and the one who put the noose around his neck. Avis was described by a visitor to the jail as Brown's friend. Brown's wife had arrived on November 30, and the couple had their last dinner with Avis's family in their apartment at the jail. That is where they last saw each other. According to Andrew Hunter,

Brown was well read and knew that the last words of prominent people are often given special attention. Just before his execution he wrote his final words on a piece of paper and gave it to his kind jailor, Avis, who conserved it as a treasure:

Brown was well read and knew that the last words of prominent people are often given special attention. Just before his execution he wrote his final words on a piece of paper and gave it to his kind jailor, Avis, who conserved it as a treasure:

When the four collaborators arrested and convicted with Brown were hung two weeks later, on December 16, there were no restrictions, and 1,600 spectators came to Charles Town "to witness the last act of the Harpers Ferry tragedy".

When the four collaborators arrested and convicted with Brown were hung two weeks later, on December 16, there were no restrictions, and 1,600 spectators came to Charles Town "to witness the last act of the Harpers Ferry tragedy".

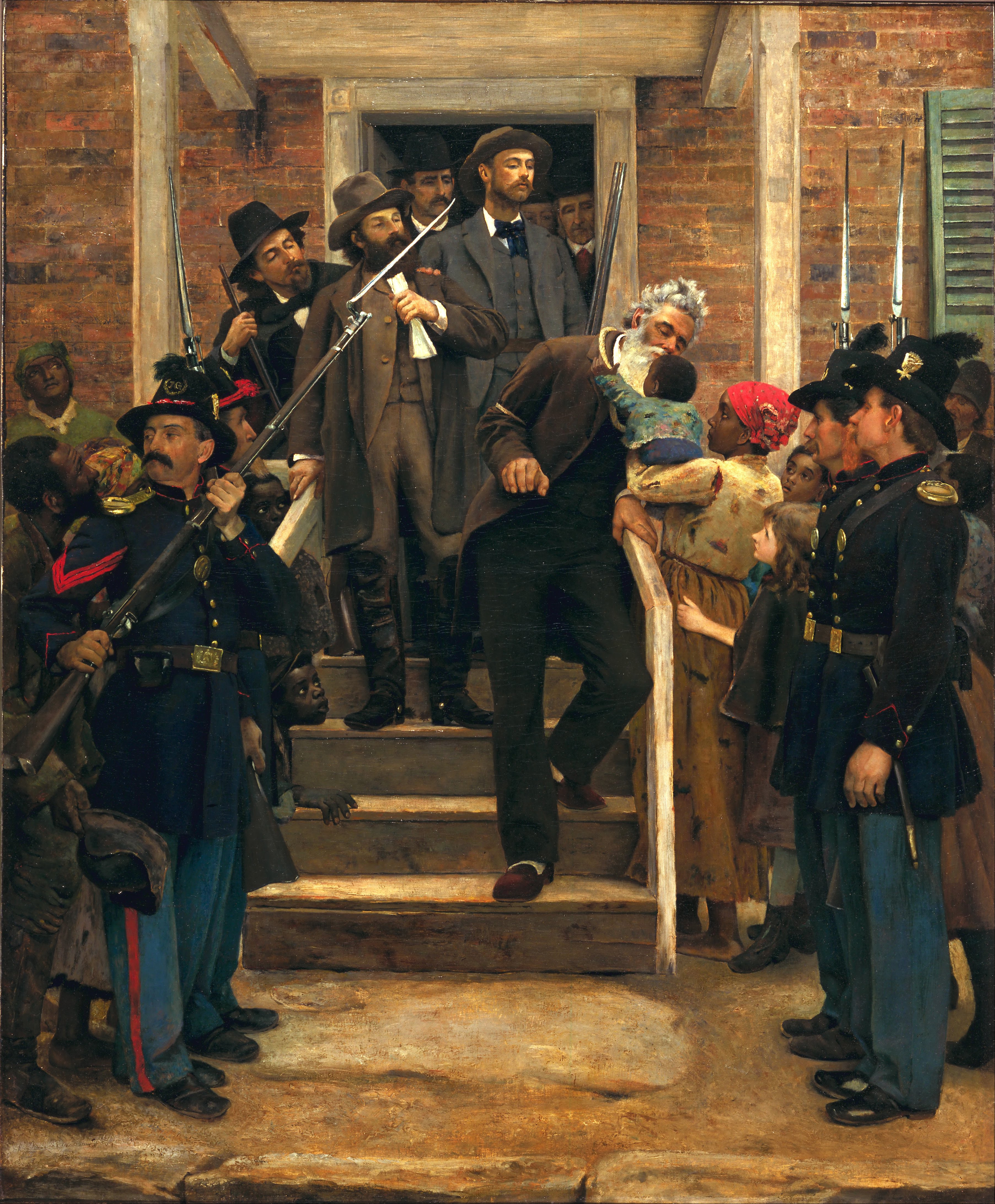

According to legend, Brown kissed a black baby when leaving the jail en route to the gallows. Several men who were present specifically deny it. For example, Prosecuting Attorney Andrew Hunter: "That whole story about his kissing a negro child as he went out of the jail is utterly and absolutely false from beginning to end. Nothing of the kind occurrednothing of the sort could have occurred. He was surrounded by soldiers and no negro could get access to him."

On the short trip from the jail to the gallows, during which he sat on his coffin in a furniture wagon, Brown was protected on both sides by lines of troops, to prevent an armed rescue. As Governor Wise did not want Brown making another speech, after leaving the jail and on the gallows, spectators and reporters were kept far enough away that Brown could not have been heard.

On his way to the gallows he remarked to the Sheriff on the beauty of the country and the excellence of the soil. "This is the first time I have had the pleasure of seeing it." He asked the Sheriff and Avis not to make him wait. He "walked to the scaffold as coolly as if going to dinner", according to Hunter. Also available a

According to legend, Brown kissed a black baby when leaving the jail en route to the gallows. Several men who were present specifically deny it. For example, Prosecuting Attorney Andrew Hunter: "That whole story about his kissing a negro child as he went out of the jail is utterly and absolutely false from beginning to end. Nothing of the kind occurrednothing of the sort could have occurred. He was surrounded by soldiers and no negro could get access to him."

On the short trip from the jail to the gallows, during which he sat on his coffin in a furniture wagon, Brown was protected on both sides by lines of troops, to prevent an armed rescue. As Governor Wise did not want Brown making another speech, after leaving the jail and on the gallows, spectators and reporters were kept far enough away that Brown could not have been heard.

On his way to the gallows he remarked to the Sheriff on the beauty of the country and the excellence of the soil. "This is the first time I have had the pleasure of seeing it." He asked the Sheriff and Avis not to make him wait. He "walked to the scaffold as coolly as if going to dinner", according to Hunter. Also available a

VirginiaChronicle

After some twenty minutes, Spectators took pieces of the gallows, or a lock of Brown's hair. The rope, specially made for the execution out of South Carolina cotton, was cut up into pieces and distributed "to those that were anxious to have it". A different report says that the South Carolina rope was not strong enough, and a hemp rope from Kentucky was used instead; a rope had also been sent from Missouri. The gallows were built into the porch of a house under construction in Charles Town "to hide them from the Yankees". Twenty-five years later, "a syndicate of relic hunters" purchased them from the house owner. They were shown at the 1893

"In the minds of Southerners, Brown was the greatest threat to slavery the South had ever witnessed." His execution on December 2 was what most white Southerners wanted, but it gave them little relief from their panic. "The South was visibly beside itself with rage and terror." According to Dennis Frye, formerly the chief historian at the

"In the minds of Southerners, Brown was the greatest threat to slavery the South had ever witnessed." His execution on December 2 was what most white Southerners wanted, but it gave them little relief from their panic. "The South was visibly beside itself with rage and terror." According to Dennis Frye, formerly the chief historian at the

published

in

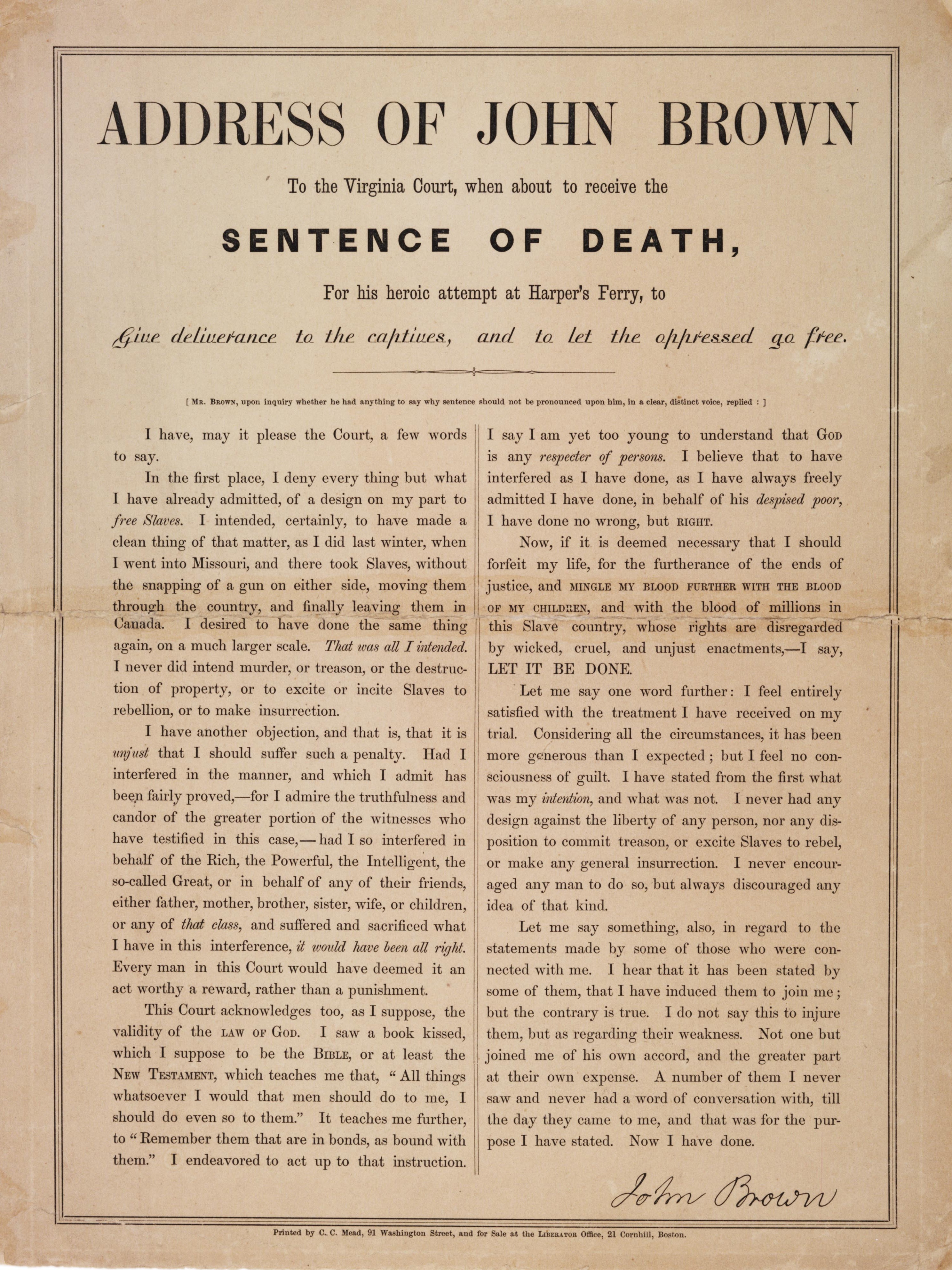

Newspapers and magazines had whole sections on the episode. A poster (broadside) was made of Brown's last speech (see left). As there was as yet no process to print a photograph, a

Newspapers and magazines had whole sections on the episode. A poster (broadside) was made of Brown's last speech (see left). As there was as yet no process to print a photograph, a

It is no coincidence that the preface of the fourth, by the family's preferred biographer,

It is no coincidence that the preface of the fourth, by the family's preferred biographer,

File:John brown interior engine house.jpg, Interior of the engine house at the armory, just before the door is broken down. Note hostages on the left.

File:John Brown at his arraignment.jpg, John Brown at his arraignment before a grand jury, drawing dated 1899

File:John Brown on trial.jpg, John Brown at his trial, unable to stand or sit

File:John Brown - Treason broadside, 1859.png, Request for prayers for Brown, dated November 4.

File:Broadside warning re John Brown's hanging.jpg, A warning to citizens of

Charles Town, Virginia

Charles Town is a city in Jefferson County, West Virginia, United States, and is also the county seat. The population was 5,259 at the 2010 census. It is named for its founder Charles Washington, youngest brother of President George Washington ...

, in October 1859. The abolitionist

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The British ...

John Brown was quickly prosecuted for treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its diplo ...

against the Commonwealth of Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth are ...

, murder, and inciting a slave insurrection, all part of his raid on the United States federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia

Harpers Ferry is a historic town in Jefferson County, West Virginia. It is located in the lower Shenandoah Valley. The population was 285 at the 2020 census. Situated at the confluence of the Potomac and Shenandoah rivers, where the U.S. state ...

. (Since 1863, both Charles Town and Harpers Ferry are in West Virginia.) He was found guilty of all charges, sentenced to death, and was executed by hanging on December 2. He was the first person executed for treason in the United States.

During most of the trial Brown, unable to stand, lay on a pallet

A pallet (also called a skid) is a flat transport structure, which supports goods in a stable fashion while being lifted by a forklift, a pallet jack, a front loader, a jacking device, or an erect crane. A pallet is the structural found ...

.

Background

On October 16, 1859, Brown led (counting himself) 22 armed men, 5 black and 17 white, toHarpers Ferry

Harpers Ferry is a historic town in Jefferson County, West Virginia. It is located in the lower Shenandoah Valley. The population was 285 at the 2020 census. Situated at the confluence of the Potomac and Shenandoah rivers, where the U.S. state ...

, an important railroad

Rail transport (also known as train transport) is a means of transport that transfers passengers and goods on wheeled vehicles running on rails, which are incorporated in tracks. In contrast to road transport, where the vehicles run on a pre ...

, river, and canal junction. His goal was to seize the federal arsenal there and then, using the captured arms, lead a slave insurrection across the South. Brown and his men engaged in a two-day standoff with local militia and federal troops, in which ten of his men were shot or killed, five were captured, and five escaped. Of Brown's three sons participating, Oliver and Watson were killed during the fight, Watson

Watson may refer to:

Companies

* Actavis, a pharmaceutical company formerly known as Watson Pharmaceuticals

* A.S. Watson Group, retail division of Hutchison Whampoa

* Thomas J. Watson Research Center, IBM research center

* Watson Systems, maker ...

surviving in agony for another day. Owen escaped and later fought in the Union Army

During the American Civil War, the Union Army, also known as the Federal Army and the Northern Army, referring to the United States Army, was the land force that fought to preserve the Union of the collective states. It proved essential to th ...

.

Reporting on the trial

Thanks to the recently-inventedtelegraph

Telegraphy is the long-distance transmission of messages where the sender uses symbolic codes, known to the recipient, rather than a physical exchange of an object bearing the message. Thus flag semaphore is a method of telegraphy, whereas ...

, Brown's trial was the first to be reported nationally. In attendance, among others, were a reporter from the ''New York Herald

The ''New York Herald'' was a large-distribution newspaper based in New York City that existed between 1835 and 1924. At that point it was acquired by its smaller rival the ''New-York Tribune'' to form the ''New York Herald Tribune''.

Hist ...

'' and another from '' The Daily Exchange'' of Baltimore, both of whom had been in Harpers Ferry since October 18; reports on the trial, including Brown's remarks, differ in details, showing the work of more than one hand. The coverage was so intense that reporters could dedicate whole paragraphs to the weather, and the visit of Brown's wife, the night before his execution, was the subject of lengthy articles. Reprinted from ''The Independent (New York City) ''The Independent'' was a weekly magazine published in New York City between 1848 and 1928. It was founded in order to promote Congregationalism and was also an important voice in support of abolitionism and women's suffrage. In 1924 it moved to ...

''. Reprinted from the ''New York Tribune

The ''New-York Tribune'' was an American newspaper founded in 1841 by editor Horace Greeley. It bore the moniker ''New-York Daily Tribune'' from 1842 to 1866 before returning to its original name. From the 1840s through the 1860s it was the domi ...

'' "Telegraphed expressly for the '' Cincinnati Gazette''."

The stories in the ''Herald'' were published unsigned, as the reporter, Edward Howard House, was in Charles Town ''incognito

Incognito is an English adjective meaning "in disguise", "having taken steps to conceal one's identity".

Incognito may also refer to:

Film and television

* ''Incognito'' (1937 film), a Danish film

* ''Incognito'' (1997 film), an American crime ...

'': in disguise, under a different name, with credentials from a Boston pro-slavery paper. He begged a visitor that knew him, Edward A. Brackett, a sketch artist from ''Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper

''Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper'', later renamed ''Leslie's Weekly'', was an American illustrated literary and news magazine founded in 1855 and published until 1922. It was one of several magazines started by publisher and illustrator Fran ...

'', not to say his real name aloud. Some of his reports, which could not be mailed safely from Charles Town, were transmitted by wrapping them around the legs of this gentleman, which were then hidden from view by his trousers.

A second artist from ''Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper'' was also in attendance, and ''Harper's Weekly

''Harper's Weekly, A Journal of Civilization'' was an American political magazine based in New York City. Published by Harper & Brothers from 1857 until 1916, it featured foreign and domestic news, fiction, essays on many subjects, and humor, ...

'' employed a local artist and nephew of Prosecuting Attorney Andrew Hunter, Porte Crayon (David Hunter Strother);

one of his drawings is in the Gallery, below

Below may refer to:

*Earth

* Ground (disambiguation)

* Soil

* Floor

* Bottom (disambiguation)

* Less than

*Temperatures below freezing

* Hell or underworld

People with the surname

* Ernst von Below (1863–1955), German World War I general

* Fr ...

. Leslie informed his readers that "one of our imitators" was publishing bogus pictures. He described how his paper had engravers and artists standing by in a New York hotel, and once a sketch had arrived from Charles Town, 16 artists worked simultaneously at transforming it (split into 16 segments) into an illustration ready to be printed.

The illustrations were so widely distributed that ''Yale Literary Magazine

The ''Yale Literary Magazine'', founded in 1836, is the oldest student literary magazine in the United States and publishes poetry, fiction, and visual art by Yale undergraduates twice per academic year. Notable alumni featured in the magazine whi ...

'' made fun of them, publishing the drawings of "our own artist on the spot" of "Governor Wise's shoes", "John Brown's watch", and the like.

Significance of the trial

Considering its aftermath, it was arguably the most important criminal trial in the history of the country, for it was closely related to the war that quickly followed. According to historian Karen Whitman, "The conduct of John Brown during his incarceration and trial was so strong and unwavering that slavery went on trial rather than slavery's captive." According to Brian McGinty, the "Brown of history" was thus born in his trial. Had Brown died before his trial, he would have been "condemned as a madman and relegated to a footnote of history". Robert McGlone added that "the trial did magnify and exalt his image. But Brown's own efforts to fashion his ultimate public persona began long before the raid and culminated only in the weeks that followed his dramatic speech at his sentencing." After his arrest, Brown engaged in extensive correspondence. After the conviction and sentencing, the judge permitted him to have visitors, and in his final month aliveVirginia law required that a month elapse between sentencing and executionhe gave interviews to reporters or anyone else who wanted to talk to him. All of this was facilitated by the "just and humane" jailor of Jefferson County, Captain John Avis, who "does all for his prisoners that his duty allows him to", and had a "sincere respect" for Brown. His "humane treatment of Brown called forth the most severe criticisms from the Virginians." Brown's last meal, and the last time he saw his wife, was with the jailer's family, in their apartment at the jail.The trial

Jurisdiction

This was the first criminal case in the United States where there was a question of whether federal courts or state courts had jurisdiction. TheSecretary of War

The secretary of war was a member of the U.S. president's Cabinet, beginning with George Washington's administration. A similar position, called either "Secretary at War" or "Secretary of War", had been appointed to serve the Congress of the ...

, after a lengthy meeting with President Buchanan, telegraphed Lee that the United States Attorney for the District of Columbia, Robert Ould

Robert Ould (January 31, 1820 – December 15, 1882) was a lawyer who served as a Confederate official during the American Civil War. From 1862 to 1865 he was the Confederate agent of exchange for prisoners of war under the Dix–Hill Carte ...

, was being sent to take charge of the prisoners and bring them to justice. However, Governor Wise quickly appeared in person.

President Buchanan

James Buchanan Jr. ( ; April 23, 1791June 1, 1868) was an American lawyer, diplomat and politician who served as the 15th president of the United States from 1857 to 1861. He previously served as secretary of state from 1845 to 1849 and repr ...

was indifferent to where Brown and his men were tried; Ould, in his brief report, did not call for federal prosecutions, as the only relevant crimes were those few that took place within the Armory. "Virginia Governor Henry Wise, on the other hand, was 'adamant' that the insurgents pay for their crimes through his state's local judicial system," "claiming" the prisoners "to be dealt with according to the laws of Virginia". As he put it, after claiming that he remained at Harper's Ferry to prevent the suspects from being lynched

Lynching is an extrajudicial killing by a group. It is most often used to characterize informal public executions by a mob in order to punish an alleged transgressor, punish a convicted transgressor, or intimidate people. It can also be an ex ...

, he "had made up his mind fully, and after determining that the prisoners should be tried in Virginia, he would not have obeyed an order to the contrary from the President of the United States."

In short, Brown and his men did not face federal charges. There were no federal court facilities nearby, and transporting the accused to a federal courthouse in the state capital of Richmond or Washington D.C.the nearest federal courthouse was in Staunton, Virginia, which was briefly mentioned in this regardand maintaining them there would have been difficult and expensive. Because of Senator Mason's resolution setting up a "select committee" to investigate the events at Harpers Ferry, there was no need of a federal venue in order to summon witnesses from other states. Murder was not a federal crime, and a federal indictment for treason or fomenting slave insurrection would have caused a political crisis (because so many abolitionists would have denounced it). Under Virginia law, fomenting a slave insurrection was clearly and unequivocally a crime. And the defendants could be tried where they were, in Charles Town.

The trial, then, took place in the county courthouse in Charles Town, not to be confused with today's capital, Charleston, West Virginia. Charles Town is the county seat of Jefferson County Jefferson County may refer to one of several counties or parishes in the United States, all of which are named directly or indirectly after Thomas Jefferson:

*Jefferson County, Alabama

*Jefferson County, Arkansas

*Jefferson County, Colorado

**Jeffe ...

, about west of Harpers Ferry. The judge was Richard Parker, of Winchester.

Military presence in Harpers Ferry

Between Brown's arrest and his execution, Charles Town was filled with armed forces, both federal and state (militia). "The Governor eptthe state troops constantly on guard. so that from the time Brown and his men were put in jail until after his execution, Charlestown had much the appearance of a military camp." The state was spending almost a thousand dollars a day () on military guards and other items, and after the episode was over the Virginia legislature appropriated $100,000 () to cover these expenditures. Charles Town was described thus by a reporter there at the time: Coordinating local security activities, including keeping non-residents without legitimate business in the city away, was Andrew Hunter, personal attorney of Governor Wise, and the most distinguished attorney in Jefferson County. The main goal was to prevent an armed rescue of Brown, despite the fact that Brown said repeatedly that he did not want to be rescued. According to Hunter in his memoirs, another reason for the heavy military presence, for which Wise was criticized, is that both Wise and Hunter were concerned that a larger battle could take place, beginning the Civil War in Virginia in 1859: Even Hunter's office was put to military use:Grand jury

Brown faced a

Brown faced a grand jury

A grand jury is a jury—a group of citizens—empowered by law to conduct legal proceedings, investigate potential criminal conduct, and determine whether criminal charges should be brought. A grand jury may subpoena physical evidence or a ...

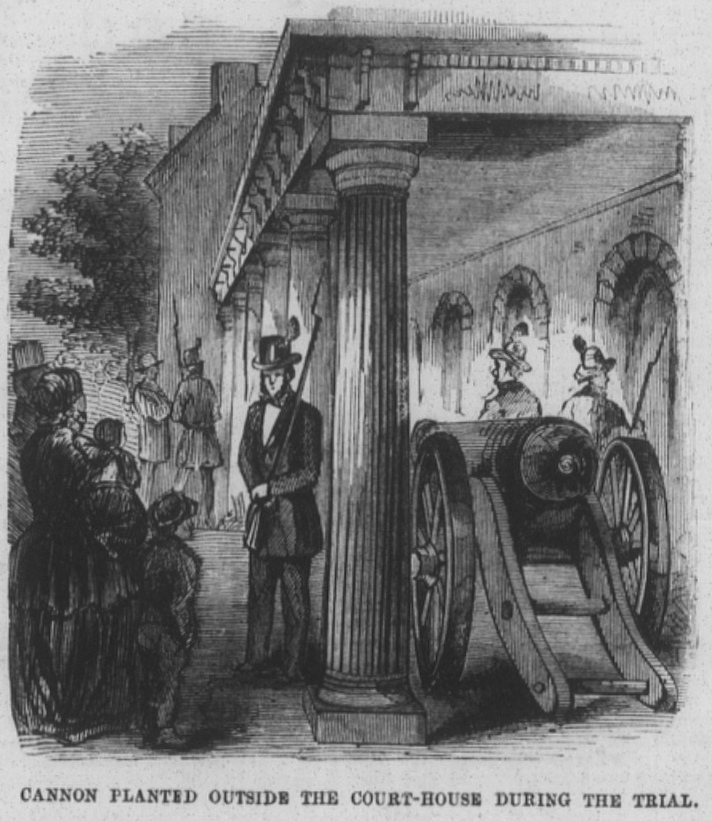

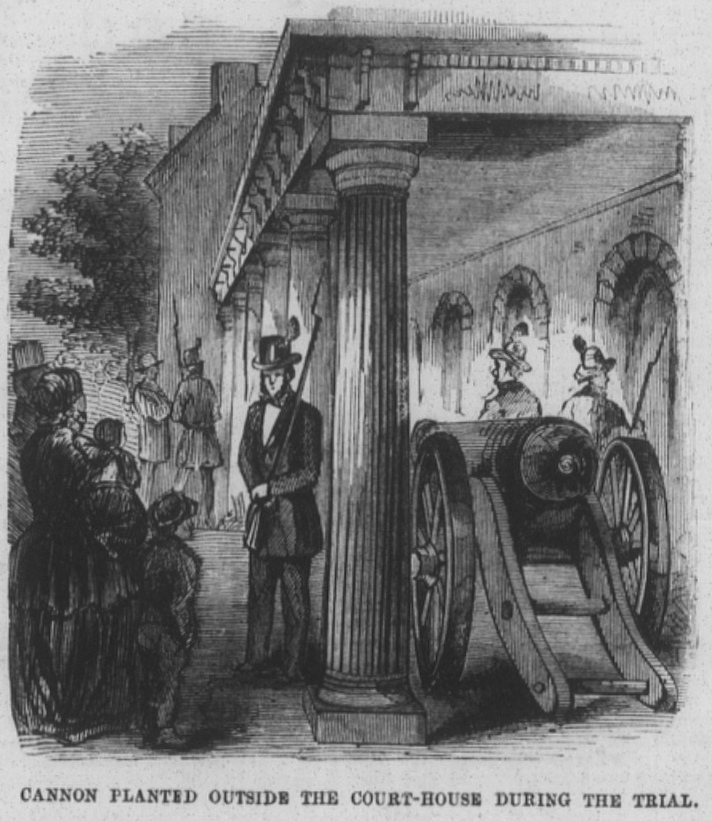

on Tuesday, October 25, 1859, just eight days after his capture in the armory. Brown was brought into court "accompanied by a body of armed men. Cannon were stationed in front of the court house ee illustration and an armed guard were patrolling round the jail."

The grand jury was also considering the other prisoners to be tried with Brown: Aaron Stephens, Edwin Coppie, Shields Green

Shields Green (1836? – December 16, 1859), who also referred to himself as "'Emperor"', was, according to Frederick Douglass, an escaped slave from Charleston, South Carolina, and a leader in John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry, in October 1859 ...

, and John Copeland. The courtroom was so crowded with spectators, all white since Blacks were not admitted, that there was not even standing room. At 5 PM the grand jury reported they had not yet finished questioning of witnesses, and the hearing was adjourned until the next day. On October 26 the grand jury returned a true bill of indictment against Brown and the other defendants, charging them with:

* Conspiring with slaves to produce insurrection,

* Treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its diplo ...

against the Commonwealth

A commonwealth is a traditional English term for a political community founded for the common good. Historically, it has been synonymous with " republic". The noun "commonwealth", meaning "public welfare, general good or advantage", dates from th ...

of Virginia, and

* Murder.

Also on the 26th, M. Johnson, the United States Marshall

The United States Marshals Service (USMS) is a federal law enforcement agency in the United States. The USMS is a bureau within the U.S. Department of Justice, operating under the direction of the Attorney General, but serves as the enforce ...

from Cleveland, Ohio, arrived and identified Copeland as a fugitive from justice in Ohio.

Counsel

The next question was what legal counsel Brown was to have. The Court assigned two "Virginians and pro-slavery men", John Faulkner and Lawson Botts, as counsel for him and the other accused. Brown did not accept them; he told the judge that he had sent for counsel, "who have not had time to reach here". Brown asked for "a delay of two or three days" for his counsel to arrive. The judge turned down Brown's request: "the expectation of other counsel...did not constitute a sufficient cause for delay, as there was no certainty about their coming. ...The brief period remaining before the close of the term of the Court rendered it necessary to proceed as expeditiously as practicable, and to be cautious about granting delays." Brown asked for "a very short delay" so that he could recover his hearing: Prosecuting attorney Hunter said that delay would be dangerous; there was "exceeding pressure on the resources of the community". He asked that Brown's body be examined by a doctor, who did not find that Brown's health required delay. The judge's refusal to postpone the trial even one day to allow Brown's counsel to arrive, or when it did arrive, to allow it to read the indictment and the testimony given so far (see below), and that Brown was being tried when he was too wounded to stand, much less "attend to his own defense", or follow what was being said, contributed to Brown's transformation into a martyr. The remainder of October 26 was used to choose jurors. Also on the 26th, abolitionistLydia Maria Child

Lydia Maria Child ( Francis; February 11, 1802October 20, 1880) was an American abolitionist, women's rights activist, Native American rights activist, novelist, journalist, and opponent of American expansionism.

Her journals, both fiction and ...

sent Wise a letter to deliver to Brown, and asked to be permitted to nurse him. Wise responded that she was free to go to Charles Town, that he had forwarded her letter there, but only the court could allow her access. Child's letter did reach Brown, who replied that he was recovering and did not need nursing. (In fact he didn't want nursing; it felt unmanly and made him uncomfortable.) He suggested instead that she raise funds for the support of his wife and the wives and children of his dead sons. Child sold her piano to raise funds for Brown's family. After publishing it in newspapers, where it was widely read, she also published in book form, to raise money, her correspondence with and relating to Brown. It sold over 300,000 copies, and contributed to the sanctification of Brown.

The trial proper

On Thursday, October 27, the trial proper began. Brown stated that he did not wish to use an insanity defense, as had been proposed by relatives and friends. A court-appointed lawyer said that a Virginia court could only try Brown for acts committed in Virginia, not in Maryland or on federal property (the arsenal). State counsel denied this was relevant. Brown, having received by telegraph news from a lawyer in Ohio, asked for a delay of one day; this was denied. The state attorney said that Brown's real motive was "to give to his friends the time and opportunity to organize a rescue." On Friday, October 28,George Henry Hoyt

George Henry Hoyt (November 25, 1837 – February 2, 1877) was an anti-slavery abolitionist who was attorney for John Brown. During the Civil War, he served as a Union cavalry officer and captain of the Kansas Red Leg scouts, rising to the ra ...

, a young but prominent Boston lawyer, arrived as counsel. One report says that Hoyt was a volunteer, but another that Hoyt was hired to defend Brown by John W. Le Barnes, one of the abolitionists who had given money to Brown in the past.

On that day Brown was described as "walking feebly" from the jail to the courthouse, where he lay down on the cot.

Prosecution

The prosecuting attorney for Jefferson County was Charles R. Harding, "whose daily occupations rinkingare not of the nature to fit for the management of an important case". He was not on the same level as the defense attorneys. He agreed, unhappily, to be replaced for these cases, as Wise wanted, by Wise's personal attorney, Andrew Hunter. A Northern newspaper described Hunter as a "furious advocate of slavery". The prosecuting attorney, then, was Hunter, whose office was in Charles Town, despite the fact that in writing he referred to himself as the ''Assistant'' Prosecuting Attorney. He wrote the indictment. The central prosecution witness in the trial was Colonel Lewis Washington, great-grandnephew of George Washington, who had been kidnapped out of his home, Beall-Air, and held hostage near the Federal Armory. His slaves were militarily " impressed" (conscripted

Conscription (also called the draft in the United States) is the state-mandated enlistment of people in a national service, mainly a military service. Conscription dates back to antiquity and it continues in some countries to the present day und ...

) by Brown, but they took no active part in the insurrection, he said. Other local witnesses testified to the seizure of the federal armory, the appearance of Virginia militia groups, and shootings on the railroad bridge. Other evidence described the U.S. Marines' raid on the fire engine house where Brown and his men were barricaded. U.S. Army Colonel Robert E. Lee

Robert Edward Lee (January 19, 1807 – October 12, 1870) was a Confederate general during the American Civil War, towards the end of which he was appointed the overall commander of the Confederate States Army. He led the Army of Nort ...

and cavalry officer J. E. B. Stuart led the Marine raid, and it freed the hostages and ended the standoff. Lee did not appear at the trial to testify, but instead filed an affidavit to the court with his account of the Marines' raid.

The manuscript evidence was of particular interest to the judge and jury. Many documents were found on the Maryland farm rented by John Brown under the alias Isaac Smith. These included hundreds of undistributed copies of a previously unknown Provisional Constitution A provisional constitution, interim constitution or transitional constitution is a constitution intended to serve during a transitional period until a permanent constitution is adopted. The following countries currently have,had in the past,such a c ...

for an anti-slavery government. These documents clinched the treason and pre-meditated murder charges against Brown.

The prosecution concluded its examination of witnesses. The defense called witnesses, but they did not appear as subpoenas had not been served on them. Mr. Hoyt said that other counsel for Brown would arrive that evening. Both court-appointed attorneys then resigned, and the trial was adjourned until the next day.

Defense

The trial resumed on Saturday, October 29. A lawyer,Samuel Chilton

Samuel Chilton (September 7, 1804January 14, 1867) was a 19th-century politician and lawyer from Virginia.

Biography

Born in Warrenton, Virginia, Chilton moved to Missouri with his family as a child and attended private school there. He studi ...

, arrived from Washington, and asked for a few hours to read the indictment and the testimony so far given; this was denied. The defense called six witnesses.

The defense claimed that the Harpers Ferry Federal Armory was not on Virginia property, but since the murdered townspeople had died in the streets outside the perimeter of the Federal facility, this carried little weight with the jury. John Brown's lack of official citizenship in Virginia was presented as a defense against treason against the State. Judge Parker dispatched this claim by reference to "rights and responsibilities" and the overlapping citizenship requirements between the Federal union and the various states. John Brown, an American citizen, could be found guilty of treason against Virginia on the basis of his temporary residence there during the days of the insurrection.

Three other substantive defense tactics failed. One claimed that since the insurrection was aimed at the U.S. government it could not be proved treason against Virginia. Since Brown and his men had fired upon Virginia troops and police, this point was mooted. His lawyers also said that since no slaves had joined the insurrection, the charge of leading a slave insurrection should be thrown out. The jury apparently did not favor this claim, either.

Extenuating circumstances were claimed by the defense when they stressed that Colonel Washington and the other hostages were not harmed and were in fact protected by Brown during the siege. This claim was not persuasive as Colonel Washington testified that he had seen men die of gunshot wounds and had been confined for days.

A dissenting news story reported Washington having testified on the 28th:

The final plea by the defense team for mercy concerned the circumstances surrounding the death of two of John Brown's men, who were apparently fired upon and killed by the Virginia militia while under a flag of truce. The armed community surrounding the Federal Arsenal did not hold their fire when Brown's men emerged to parley. This incident is noticeable upon a close reading of the published testimony, but is generally neglected in more popular accounts. If the rebels under a flag of truce were deliberately fired upon, it does not appear to have been a major issue to the judge and jury.

The defense's closing argument was given by Hiram Griswold, a lawyer from Cleveland, Ohio, who arrived on October 31. Griswold was well-known as an abolitionist; he had helped fugitive slaves

In the United States, fugitive slaves or runaway slaves were terms used in the 18th and 19th century to describe people who fled slavery. The term also refers to the federal Fugitive Slave Acts of 1793 and 1850. Such people are also called freed ...

, and was representing Brown '' pro bono''. In contrast, Chilton was no abolitionist, and only became involved after supporters of Brown promised to pay a very high fee, $1,000 ().

Brown, while making various suggestions to his attorneys, was frustrated because under Virginia law, defendants were not allowed to testify, the assumption being that they had reason not to tell the truth.

Verdict

The prosecution began its closing argument on Friday, concluding on Monday, October 31. The jury retired to consider its verdict. The jury deliberated for only 45 minutes. When it returned, according to the report in the ''New York Herald

The ''New York Herald'' was a large-distribution newspaper based in New York City that existed between 1835 and 1924. At that point it was acquired by its smaller rival the ''New-York Tribune'' to form the ''New York Herald Tribune''.

Hist ...

'', "the only calm and unruffled countenance there" was that of Brown. When the jury reported that it found him guilty of all charges, "not the slightest sound was heard in the vast crowd".

One of Brown's attorneys made "a motion for an arrest of judgment", but it was not argued. "Counsel on both sides being too much exhausted to go on, the motion was ordered to stand over until tomorrow, and Brown was again removed unsentenced to prison" (actually to the Jefferson County Jefferson County may refer to one of several counties or parishes in the United States, all of which are named directly or indirectly after Thomas Jefferson:

*Jefferson County, Alabama

*Jefferson County, Arkansas

*Jefferson County, Colorado

**Jeffe ...

jail).

Speech to the court and sentence

Brown's sentencing took place on November 2, 1859. As Virginia court procedure required, Brown was first asked to stand and say if there was reason sentence should not be passed upon him. He arosehe could now stand unassistedand made what his first biographer called " islast speech". He said his only goal was to free slaves, not start a revolt, that it was God's work, that if he had been helping the rich instead of the poor he would not be in court, and that the criminal trial had been more fair than he expected. According to

Brown's sentencing took place on November 2, 1859. As Virginia court procedure required, Brown was first asked to stand and say if there was reason sentence should not be passed upon him. He arosehe could now stand unassistedand made what his first biographer called " islast speech". He said his only goal was to free slaves, not start a revolt, that it was God's work, that if he had been helping the rich instead of the poor he would not be in court, and that the criminal trial had been more fair than he expected. According to Ralph Waldo Emerson

Ralph Waldo Emerson (May 25, 1803April 27, 1882), who went by his middle name Waldo, was an American essayist, lecturer, philosopher, abolitionist, and poet who led the transcendentalist movement of the mid-19th century. He was seen as a cham ...

, this speech's only equal in American oratory is the Gettysburg Address

The Gettysburg Address is a speech that U.S. President Abraham Lincoln delivered during the American Civil War at the dedication of the Soldiers' National Cemetery, now known as Gettysburg National Cemetery, in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania on the ...

. "His own speeches to the court have interested the nation in him," said Emerson.

It was reproduced in full in at least 52 American newspapers, making the front page of the ''New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'', the '' Richmond Dispatch'', and several other papers. Wm. Lloyd Garrison printed it on a broadside and had it for sale in The Liberator's office (reproduced in Gallery, below).

After Brown completed his speech, the entire courtroom sat in silence. According to one journalist news source: "The only demonstration made was by the clapping of the hands pplaudingof one man in the crowd, who is not a resident of Jefferson County. This was promptly suppressed, and much regret is expressed by the citizens at its occurrence." The judge then sentenced Brown to death by hanging, to take place in a month, on December 2. Brown received his death sentence with composure.

November 2December 2

Under Virginia law a month had to separate the sentence of death and its execution. Governor Wise resisted pressures to move up Brown's execution because, he said, he did not want anyone saying that Brown's rights had not been fully respected. The delay meant that the issue grew further; Brown's raid, trial, visitors, correspondence, upcoming execution, and Wise's role in making it happen were reported on constantly in newspapers, both local and national. An appeal to theVirginia Court of Appeals

The Court of Appeals of Virginia, established January 1, 1985, is an intermediate appellate court of 17 judges that hears appeals from decisions of Virginia's circuit courts and the Virginia Workers' Compensation Commission. The Court sits in p ...

(a petition for a Writ of Error

In law, an appeal is the process in which cases are reviewed by a higher authority, where parties request a formal change to an official decision. Appeals function both as a process for error correction as well as a process of clarifying and ...

) was not successful.

Expulsion of Brown's lawyers

After Brown's sentencing on November 2, a Wednesday, the Court proceeded with the trials ofShields Green

Shields Green (1836? – December 16, 1859), who also referred to himself as "'Emperor"', was, according to Frederick Douglass, an escaped slave from Charleston, South Carolina, and a leader in John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry, in October 1859 ...

, John Copeland Jr.

John Anthony Copeland Jr. (August 15, 1834 – December 16, 1859) was born free in Raleigh, North Carolina, one of the eight children born to John Copeland Sr. and his wife Delilah Evans, free mulattos, who married in Raleigh in 1831. Delilah was ...

, John Edwin Cook, and Edwin Coppock

Barclay Coppock (January 4, 1839 – September 4, 1861), also spelled "Coppac", "Coppic", and "Coppoc", was a follower of John Brown and a Union Army soldier in the American Civil War. Along with his brother Edwin Coppock (June 30, 1835 &nd ...

. After conviction they were on Thursday, November 10 sentenced to death a month later. The Court session ended Friday, November 11.

On Saturday, November 12, the mayor of Charles Town, Thomas C. Green, issued a proclamation, presumably written by Hunter, telling "strangers" to leave the town or they would be subject to arrest. Delegations called on both Hoyt and Sennott to warn them of violence if they did not leave; the mayor said he had no force with which to resist the lynch mob

Lynching is an extrajudicial killing by a group. It is most often used to characterize informal public executions by a mob in order to punish an alleged transgressor, punish a convicted transgressor, or intimidate people. It can also be an ex ...

expected to assemble the next day, Sunday. "The people of Charlestown...are wholly given up to hatred of all Northern visitors." Sennott refused, but Hoyt left the same day, together with Mr. Jewett, an artist from ''Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper

''Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper'', later renamed ''Leslie's Weekly'', was an American illustrated literary and news magazine founded in 1855 and published until 1922. It was one of several magazines started by publisher and illustrator Fran ...

'', suspected to have also been the undercover ''New-York Tribune'' reporter.

The question of clemency

Many things that Governor Wise did augmented rather than reduced tensions: by insisting he be tried in Virginia, and by turning Charles Town into an armed camp, full of state militia units. According to Franny Nudelman, "At every juncture he chose to escalate rather than pacify sectional animosity." As he put it: "We are in arms. ...We must demand of each State what position she means to maintain in the future regarding slavery." Wise received many communicationsone source says "thousands", and the Virginia General Assembly's joint committee inspected "near 500"urging him to mitigate Brown's sentence. For example, New York City MayorFernando Wood

Fernando Wood (February 14, 1812 – February 13, 1881) was an American Democratic Party politician, merchant, and real estate investor who served as the 73rd and 75th Mayor of New York City. He also represented the city for several terms in ...

, who would seriously propose that New York City secede from the Union so as to continue the cotton trade with the Confederacy, and who strongly opposed the Thirteenth Amendment ending slavery, wrote Wise on November 2. He advocated sending Brown to prison instead of executing him, saying that it was in the South's interest to do so; it would benefit the South more to behave magnanimously toward a fanatic, with whom there was sympathy, than to execute him.

Wise replied that in his view Brown should be hung, and he regretted not having gotten to Harpers Ferry fast enough to declare martial law

Martial law is the imposition of direct military control of normal civil functions or suspension of civil law by a government, especially in response to an emergency where civil forces are overwhelmed, or in an occupied territory.

Use

Marti ...

and execute the rebels through court-martial. Brown's trial was fair and "it was impossible not to convict him." As Governor, he had nothing to do with Brown's death sentence; he did not have to sign a death warrant. His only possible involvement was from his power to pardon, and he had received "petitions, prayers, threats from almost every Free State in the Union," warning that Brown's execution would turn him into a martyr. But Wise stated that as Governor he did not have authority to pardon a traitor, only the House of Burgesses

The House of Burgesses was the elected representative element of the Virginia General Assembly, the legislative body of the Colony of Virginia. With the creation of the House of Burgesses in 1642, the General Assembly, which had been established ...

could. For the other charges, Wise believed that it would not be wise to "spare a murderer, a robber, a traitor," because of "public sentiment elsewhere". He also refused to declare Brown insane, which would have spared his life and put him in a mental hospital; Brown's supporter Gerrit Smith

Gerrit Smith (March 6, 1797 – December 28, 1874), also spelled Gerritt Smith, was a leading American social reformer, abolitionist, businessman, public intellectual, and philanthropist. Married to Ann Carroll Fitzhugh, Smith was a candida ...

was forced to do that. Public sentiment in Virginia clearly wanted Brown executed. Wise was spoken of as a possible presidential candidate, and a pardon or reprieve could have ended his political career. The ''Richmond Enquirer'', backing Wise as a presidential candidate on November 10, said that because of Wise's handling of "the Harper's Ferry affair" his "stock has gone up one hundred percent".

Plans for a rescue

After a number of other reports of rescue plans from various surrounding states, Hunter received on November 19 a telegraphic dispatch from "United States Marshal Johnson of Ohio," and Governor Wise one from the Governor of Ohio, stating that a large number of men, from 600 to 1,000, were arming under the leadership of John Brown, Jr., to attempt to retake the prisoners. After Hunter informed Governor Wise, and Wise telegraphed President Buchanan, Buchanan sent two companies of artillery fromFort Monroe

Fort Monroe, managed by partnership between the Fort Monroe Authority for the Commonwealth of Virginia, the National Park Service as the Fort Monroe National Monument, and the City of Hampton, is a former military installation in Hampton, Virgi ...

to Harpers Ferry. Wise sent "detectives" to Harpers Ferry, charging Hunter to use them to investigate rescue efforts from Ohio. "I sent one to Oberlin, who joined the party there, slept one night in the same bed as John Brown, Jr., and reported to me their doings out and out," said Hunter. Hunter had "troops" moved to block entry from Ohio into Virginia. Nothing significant came of any of these rescue plans.

Brown friend and admirer Thomas Wentworth Higginson

Thomas Wentworth Higginson (December 22, 1823May 9, 1911) was an American Unitarian minister, author, abolitionist, politician, and soldier. He was active in the American Abolitionism movement during the 1840s and 1850s, identifying himself with ...

traveled to North Elba in November, unsuccessfully seeking Mary Brown's support for a rescue attempt. He and Lysander Spooner

Lysander Spooner (January 19, 1808May 14, 1887) was an American individualist anarchist, abolitionist, entrepreneur, essayist, legal theorist, pamphletist, political philosopher, Unitarian and writer.

Spooner was a strong advocate of the labor ...

, two weeks before the execution, were prevented only by lack of funds from kidnapping Governor Wise and holding him hostage in exchange for Brown's release.

Higginson accompanied Mary to Harpers Ferry to recover John's body.

Brown's numerous visitors and extensive correspondence

During the month between his conviction and the day of his execution, Brown wrote over 100 letters, in which he described his vision of a post-slavery America in eloquent and spiritual terms. Most of them, and a few letters to him, were immediately published in newspapers and pamphlets. They were hugely influential in accelerating the abolition movement and putting slaveholders on the defensive. A version of this article appears in print on November 19, 2020, Section C, Page 5 of the New York edition with the headline: Fact or Fiction, Starring John Brown. He had previously been prevented by the Court from "making a full statement of his motives and intentions through the press", as he desired; the Court had "refused all access to reporters". Now that he had been convicted and sentenced, there were no more restrictions on visitors, and Brown, relishing the publicity his anti-slavery views received, talked to reporters or anyone else that wanted to see him, although abolitionists, like Rebecca Buffum Spring, could only visit him with great difficulty. "I have very many visits from pro-slavery persons almost daily, & I endeavor to Improve them faifthfully, plainly, and kindly." A scholar estimates the number of visitors received during that month as 800: politicians (including Governor Wise and a Virginia senator), reporters, foes, and friends. "I have...had a great many rare opportunities for 'preaching righteousness in the great congregation'" []. He wrote to his wife that he had received so many "kind and encouraging letters" that he could not possibly reply to them all. "I do not think that I ever enjoyed life better than since my confinement here," he wrote on November 24. "I certainly think I was never more cheerful in my life." "My mind is very tranquil, I may say joyous." On November 28, Brown wrote the following to an Ohio friend,Daniel R. Tilden

Daniel Rose Tilden (November 5, 1804 – March 4, 1890) was an American lawyer and politician who served two terms as a U.S. Representative from Ohio from 1843 to 1847.

Biography

Born in Lebanon, Connecticut, Tilden attended the public s ...

:

The published letters were hugely influential in accelerating the abolition movement and putting slaveholders on the defensive.

Contemporary assessments

Northerners commemorated the trial and coming execution with public prayers, church services, marches, and meetings.Ralph Waldo Emerson

Ralph Waldo Emerson (May 25, 1803April 27, 1882), who went by his middle name Waldo, was an American essayist, lecturer, philosopher, abolitionist, and poet who led the transcendentalist movement of the mid-19th century. He was seen as a cham ...

's prediction, in a lecture on November 8, that Brown, if executed, "would make the gallows glorious, like the cross". "was responded to by the immense audience in the most enthusiastic manner." His quote was reprinted all over the country: By December 2, "the entire nation" was fixated on Brown.

The '' New York Independent'' said the following of him during this month:

In contrast, the '' Richmond Dispatch'' called him a "scoundrel", adding that he was "a cold-blooded, midnight murderer, with not a particle of humanity or generosity belonging to his character." "The recent events at Harper's Ferry have very much roused the military spirit among us."

Help for Mary Brown and other relatives

A meeting was held in theTremont Temple

The Tremont Temple on 88 Tremont Street is a Baptist church in Boston, affiliated with the American Baptist Churches, USA. The existing multi-storey, Renaissance Revival structure was designed by architect Clarence Blackall of Boston, and opened ...

, Boston, on November 19, "in aid of the suffering families of John Brown and his associates". Attendance was over 2,000. Presiding was John A. Andrew; his speech and his other testimony supporting Brown, including "John Brown and John A. Andrew" (pp. 13–15), reprinted from the '' Boston Traveller'', were published in 1860 to help his successful campaign for Governor of Massachusetts.

Visit from Henry Clay Pate

His visitors included his pro-slavery enemy from KansasHenry Clay Pate

Henry Clay Pate (21 April 1833–11 May 1864) was an American writer, newspaper publisher and soldier. A strong advocate of slavery, he was a border ruffian in the " Bleeding Kansas" unrest. He is best known for his conflict with, and capture ...

, who came from his home in Petersburg

Petersburg, or Petersburgh, may refer to:

Places Australia

*Petersburg, former name of Peterborough, South Australia

Canada

* Petersburg, Ontario

Russia

*Saint Petersburg, sometimes referred to as Petersburg

United States

*Peterborg, U.S. Virg ...

to Charles Town to see Brown. They prepared a statement, witnessed by Capt. John Avis and two others, about events at the Battle of Black Jack

The Battle of Black Jack took place on June 2, 1856, when antislavery forces, led by the noted abolitionist John Brown, attacked the encampment of Henry C. Pate near Baldwin City, Kansas. The battle is cited as one incident of "Bleeding Kans ...

.

Visit from his wife Mary

John repeatedly expressed his desire that Mary not visit him, as that would "add to my affliction, & cannot possibly do me any good". It would use some of her scant resources, and subject her to being "a gazing stock throughout the whole journey, to be remarked upon in every look, word and action by all sorts of creatures and all sorts of papers." Despite her husband's words, Mary set out anyway for Charles Town. Brown's friend Thomas Higginson went to North Elba so as to escort her. By the time John heard about her trip, she was in Philadelphia, and he had his lawyer telegraph "Mary's abolitionist hosts in Philadelphia" (James Miller McKim

James Miller McKim (November 10, 1810 – June 13, 1874) was a Presbyterian minister and abolitionist. He was also the father of the architect Charles Follen McKim.

Biography

McKim was born in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, and educated at Dickinson ...

) to detain her.

Mary did, however, reach Charles Town, and was allowed by Virginia Governor Wise WISE may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media

* WISE (AM), a radio station licensed to Asheville, North Carolina

*WISE-FM, a radio station licensed to Wise, Virginia

* WISE-TV, a television station licensed to Fort Wayne, Indiana

Education

* ...

to visit Brown for several hours on November 30, though she was not allowed to stay with him overnight.

His will

John Brown's first will is dated November 18, 1859. According to other sources, the identical document was prepared December 1, in the presence of his wife, by Judge Andrew Hunter, witnessed by Hunter and the jailor Captain John Avis. He distributed his few possessionshis surveyor's tools, his silver watch, the family Bibleto his surviving children. Bibles were to be purchased for each of his children and grandchildren. Brown made a second will, the morning of his execution, in which he authorized the Sheriff of Jefferson County to sell his pikes and guns, if they could be found, and give the money to his wife.

In his correspondence Brown mentioned several times how well he was treated by Avis, who was also in charge of Brown's execution and the one who put the noose around his neck. Avis was described by a visitor to the jail as Brown's friend. Brown's wife had arrived on November 30, and the couple had their last dinner with Avis's family in their apartment at the jail. That is where they last saw each other. According to Andrew Hunter,

Brown made a second will, the morning of his execution, in which he authorized the Sheriff of Jefferson County to sell his pikes and guns, if they could be found, and give the money to his wife.

In his correspondence Brown mentioned several times how well he was treated by Avis, who was also in charge of Brown's execution and the one who put the noose around his neck. Avis was described by a visitor to the jail as Brown's friend. Brown's wife had arrived on November 30, and the couple had their last dinner with Avis's family in their apartment at the jail. That is where they last saw each other. According to Andrew Hunter,

Brown's last words

Brown was well read and knew that the last words of prominent people are often given special attention. Just before his execution he wrote his final words on a piece of paper and gave it to his kind jailor, Avis, who conserved it as a treasure:

Brown was well read and knew that the last words of prominent people are often given special attention. Just before his execution he wrote his final words on a piece of paper and gave it to his kind jailor, Avis, who conserved it as a treasure:

Charlestown, Va. 2nd December, 1859. I John Brown am now quite certain that the crimes of this guilty, land: will never be purged away; but with Blood. I had as I now think: vainly flattered myself that without very much bloodshed; it might be done."Without very much bloodshed" is an allusion to his own failed project to free the slaves, which he in hindsight saw as vanity and self-flattery. This document was reproduced and made available as a souvenir when

John Brown's Fort

John Brown's Fort was originally built in 1848 for use as a guard and fire engine house by the federal Harpers Ferry Armory in Harpers Ferry, Virginia (since 1863, West Virginia). An 1848 military report described the building as "An engine and ...

was exhibited at the Columbian Exposition

The World's Columbian Exposition (also known as the Chicago World's Fair) was a world's fair held in Chicago in 1893 to celebrate the 400th anniversary of Christopher Columbus's arrival in the New World in 1492. The centerpiece of the Fair, hel ...

in Chicago, in 1893.

He gave a similar, even stronger form of the same statement to jailer Hiram O'Bannon:

Execution

Brown was the first person executed for treason in the history of the United States. He was hanged on December 2, 1859, at about 11:15 AM, in a vacant field several blocks away from theJefferson County Jefferson County may refer to one of several counties or parishes in the United States, all of which are named directly or indirectly after Thomas Jefferson:

*Jefferson County, Alabama

*Jefferson County, Arkansas

*Jefferson County, Colorado

**Jeffe ...

jail. According to the correspondent of the ''New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'':

According to jailer John Avis, Brown was the happiest man in Charles Town.

Spectators

Brown was not the only happy man present. For those who supported slavery, the execution of Brown was a momentous event. Finally abolitionists were starting to be dealt with appropriately. The rope with which Brown was to be hung, made of South Carolina cotton, as visitors were told, was on display in the Sheriff's office. The press was there in force. Hundreds of people visited the carpenter making Brown's coffin, asking for a piece of the board. Yet there were "very few strangers", according to a reporter who concealed his name. An article on the mood in Charles Town on the eve of Brown's execution is entitled "Revelry". The day before the execution the military held a dress parade. (Two weeks later, another was held the day before the executions of Brown's four captured allies,Green

Green is the color between cyan and yellow on the visible spectrum. It is evoked by light which has a dominant wavelength of roughly 495570 Nanometre, nm. In subtractive color systems, used in painting and color printing, it is created by ...

, Copeland, Cook, and Coppic.) Members of the Young Guard, from Richmond, went door to door, "treating the fair occupants to some vocal as well as instrumental music." A military band, arrived from Richmond, briefly made everything "gleeful". The fife and kettle-drum were heard "continually".

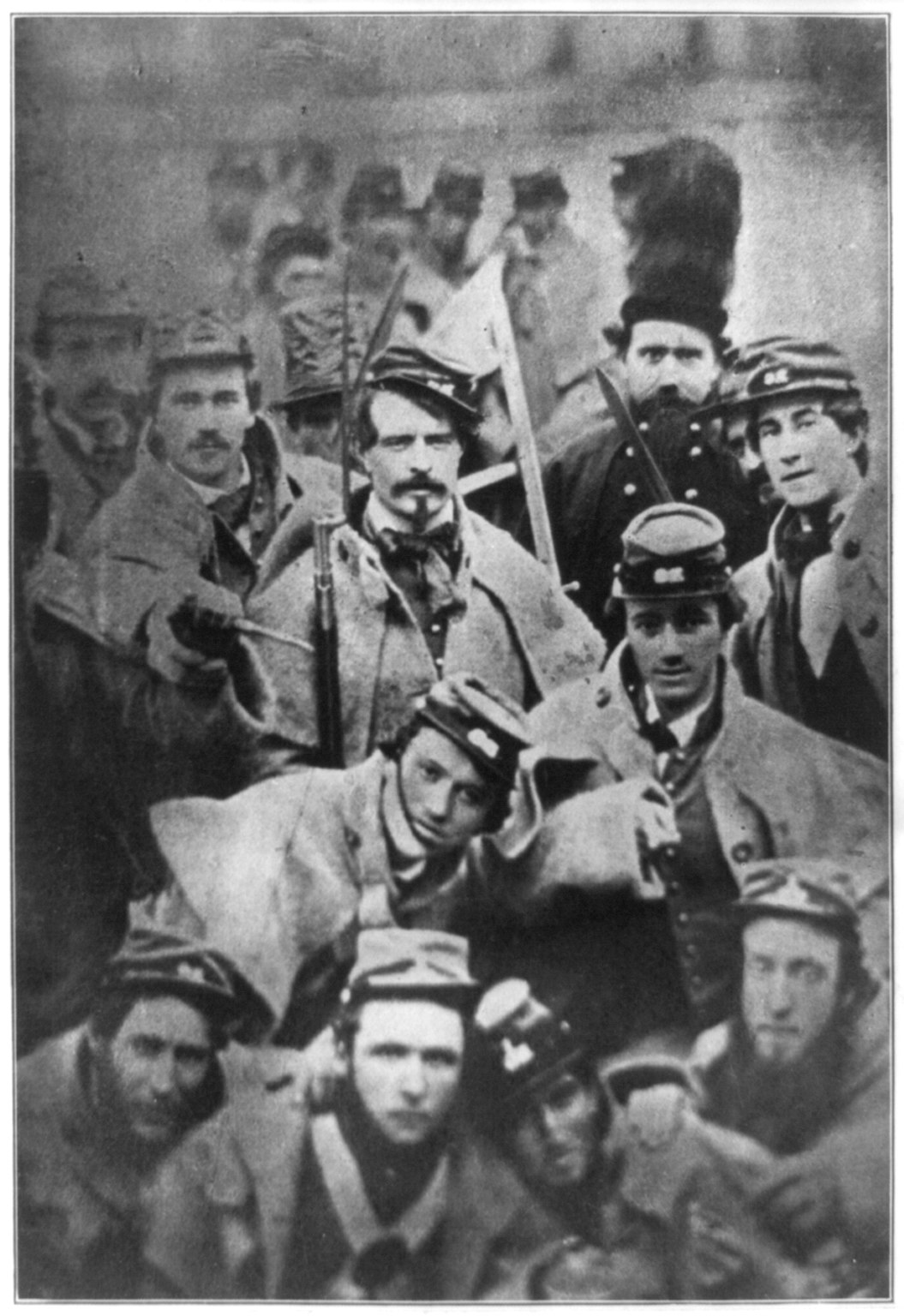

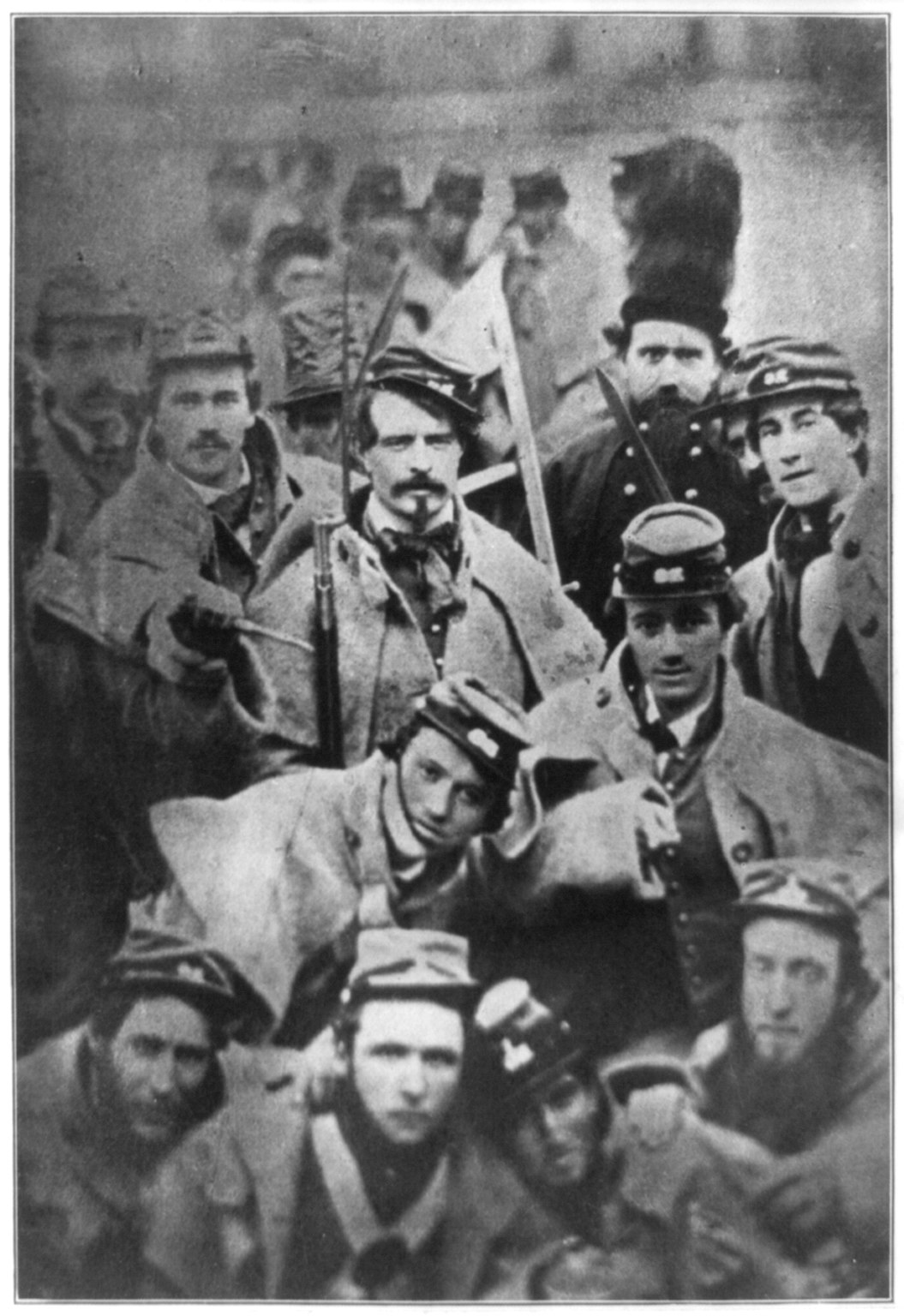

The roster of those present sounds like a foretaste of the Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government polic ...

. Thomas Jackson (the future Stonewall Jackson

Thomas Jonathan "Stonewall" Jackson (January 21, 1824 – May 10, 1863) was a Confederate general during the American Civil War, considered one of the best-known Confederate commanders, after Robert E. Lee. He played a prominent role in nearl ...

) was there, as were Robert E. Lee

Robert Edward Lee (January 19, 1807 – October 12, 1870) was a Confederate general during the American Civil War, towards the end of which he was appointed the overall commander of the Confederate States Army. He led the Army of Nort ...

and 2,000 Federal troops and Virginia militia

A militia () is generally an army or some other fighting organization of non- professional soldiers, citizens of a country, or subjects of a state, who may perform military service during a time of need, as opposed to a professional force of r ...

. The future Civil War poet Walt Whitman

Walter Whitman (; May 31, 1819 – March 26, 1892) was an American poet, essayist and journalist. A humanist, he was a part of the transition between transcendentalism and realism, incorporating both views in his works. Whitman is among ...

was present, as was the actor John Wilkes Booth

John Wilkes Booth (May 10, 1838 – April 26, 1865) was an American stage actor who assassinated United States President Abraham Lincoln at Ford's Theatre in Washington, D.C., on April 14, 1865. A member of the prominent 19th-century Booth the ...

, the latter of whom was such a white supremacist that in five years he would assassinate President Lincoln, after Lincoln supported giving Blacks the vote, which Booth called "nigger citizenship". He had read in a newspaper about the upcoming execution of Brown, whom he called "the grandest character of this century." He was so interested in seeing it that he abandoned rehearsals at the Richmond Theater and travelled to Charles Town specifically for this purpose. So as to gain access that the public would not have, he donned for one day a borrowed uniform of the Richmond Grays

The 1st Virginia Infantry Regiment was an infantry regiment raised in the Commonwealth of Virginia for service in the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War. It fought mostly with the Army of Northern Virginia.

The 1st Virginia ...

, a volunteer militia

A militia () is generally an army or some other fighting organization of non- professional soldiers, citizens of a country, or subjects of a state, who may perform military service during a time of need, as opposed to a professional force of r ...

of 1,500 men traveling to Charles Town for Brown's hanging, to guard against a possible attempt to rescue Brown from the gallows by force. Planter and pro-slavery activist Edmund Ruffin

Edmund Ruffin III (January 5, 1794 – June 18, 1865) was a wealthy Virginia planter who served in the Virginia Senate from 1823 to 1827. In the last three decades before the American Civil War, his pro-slavery writings received more attention tha ...

, traditionally credited with firing the first shot of the Civil War (at Fort Sumter

Fort Sumter is a sea fort built on an artificial island protecting Charleston, South Carolina from naval invasion. Its origin dates to the War of 1812 when the British invaded Washington by sea. It was still incomplete in 1861 when the Battl ...

, where he traveled for the purpose), did the same. That Governor Wise would not be present made the paper, as did the fact that his son, newspaper editor O. Jennings Wise

O is the fifteenth letter of the modern Latin alphabet.

O may also refer to:

Letters

* Օ օ, (Unicode: U+0555, U+0585) a letter in the Armenian alphabet

* Ο ο, Omicron, (Greek), a letter in the Greek alphabet

* O (Cyrillic), a letter of ...

, was there as a militia member.

About 2,000 "excursionists" intended to attend the execution, but the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad

The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad was the first common carrier railroad and the oldest railroad in the United States, with its first section opening in 1830. Merchants from Baltimore, which had benefited to some extent from the construction of ...

refused to transport them, and Governor Wise shut down the Winchester and Potomac Railroad for other than military use. Threatening to invoke martial law

Martial law is the imposition of direct military control of normal civil functions or suspension of civil law by a government, especially in response to an emergency where civil forces are overwhelmed, or in an occupied territory.

Use

Marti ...

, Wise asked all citizens to remain at home, as did the mayor of Charles Town (see below

Below may refer to:

*Earth

* Ground (disambiguation)

* Soil

* Floor

* Bottom (disambiguation)

* Less than

*Temperatures below freezing

* Hell or underworld

People with the surname

* Ernst von Below (1863–1955), German World War I general

* Fr ...

). A prospective visitor from northwestern Pennsylvania, where Brown had lived for 11 years, was told in Philadelphia not to proceed, as martial law had in fact been declared in "the country around Charlestown". Militia had been stationed in Charles Town continuously from the arrest until the execution, to prevent a much-feared armed rescue of Brown.

Military orders for the day of execution had 14 points. The telegraph was restricted to military use.

As further protection, "a field-piece loaded with grape

A grape is a fruit, botanically a berry (botany), berry, of the deciduous woody vines of the flowering plant genus ''Vitis''. Grapes are a non-Climacteric (botany), climacteric type of fruit, generally occurring in clusters.

The cultivation of ...

and canister had been planted directly in front of and aimed at the scaffold, so as to blow poor Brown's body to smithereens in the event of attempted rescue." "The outer line of military will be nearly a mile (1.4 km) from the scaffold, and the inner line so distant that not a word John Brown may speak can be heard."

When the four collaborators arrested and convicted with Brown were hung two weeks later, on December 16, there were no restrictions, and 1,600 spectators came to Charles Town "to witness the last act of the Harpers Ferry tragedy".

When the four collaborators arrested and convicted with Brown were hung two weeks later, on December 16, there were no restrictions, and 1,600 spectators came to Charles Town "to witness the last act of the Harpers Ferry tragedy".

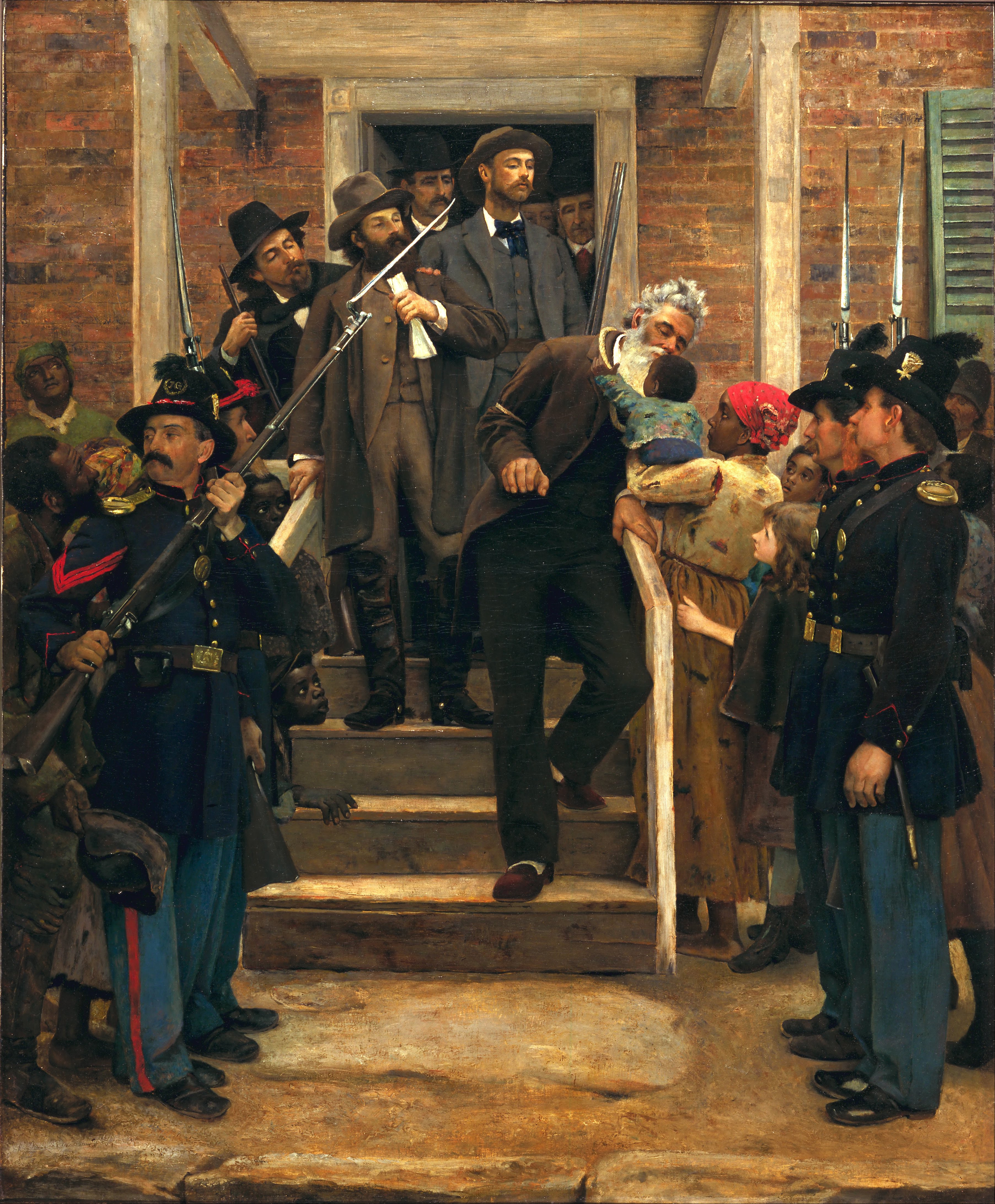

The gallows

According to legend, Brown kissed a black baby when leaving the jail en route to the gallows. Several men who were present specifically deny it. For example, Prosecuting Attorney Andrew Hunter: "That whole story about his kissing a negro child as he went out of the jail is utterly and absolutely false from beginning to end. Nothing of the kind occurrednothing of the sort could have occurred. He was surrounded by soldiers and no negro could get access to him."

On the short trip from the jail to the gallows, during which he sat on his coffin in a furniture wagon, Brown was protected on both sides by lines of troops, to prevent an armed rescue. As Governor Wise did not want Brown making another speech, after leaving the jail and on the gallows, spectators and reporters were kept far enough away that Brown could not have been heard.

On his way to the gallows he remarked to the Sheriff on the beauty of the country and the excellence of the soil. "This is the first time I have had the pleasure of seeing it." He asked the Sheriff and Avis not to make him wait. He "walked to the scaffold as coolly as if going to dinner", according to Hunter. Also available a

According to legend, Brown kissed a black baby when leaving the jail en route to the gallows. Several men who were present specifically deny it. For example, Prosecuting Attorney Andrew Hunter: "That whole story about his kissing a negro child as he went out of the jail is utterly and absolutely false from beginning to end. Nothing of the kind occurrednothing of the sort could have occurred. He was surrounded by soldiers and no negro could get access to him."

On the short trip from the jail to the gallows, during which he sat on his coffin in a furniture wagon, Brown was protected on both sides by lines of troops, to prevent an armed rescue. As Governor Wise did not want Brown making another speech, after leaving the jail and on the gallows, spectators and reporters were kept far enough away that Brown could not have been heard.

On his way to the gallows he remarked to the Sheriff on the beauty of the country and the excellence of the soil. "This is the first time I have had the pleasure of seeing it." He asked the Sheriff and Avis not to make him wait. He "walked to the scaffold as coolly as if going to dinner", according to Hunter. Also available aVirginiaChronicle

After some twenty minutes, Spectators took pieces of the gallows, or a lock of Brown's hair. The rope, specially made for the execution out of South Carolina cotton, was cut up into pieces and distributed "to those that were anxious to have it". A different report says that the South Carolina rope was not strong enough, and a hemp rope from Kentucky was used instead; a rope had also been sent from Missouri. The gallows were built into the porch of a house under construction in Charles Town "to hide them from the Yankees". Twenty-five years later, "a syndicate of relic hunters" purchased them from the house owner. They were shown at the 1893

Columbian Exposition

The World's Columbian Exposition (also known as the Chicago World's Fair) was a world's fair held in Chicago in 1893 to celebrate the 400th anniversary of Christopher Columbus's arrival in the New World in 1492. The centerpiece of the Fair, hel ...

, along with John Brown's Fort

John Brown's Fort was originally built in 1848 for use as a guard and fire engine house by the federal Harpers Ferry Armory in Harpers Ferry, Virginia (since 1863, West Virginia). An 1848 military report described the building as "An engine and ...

.

John Brown's body

Governor Wise had John's body released to his widow Mary, who was awaiting it in Harpers Ferry. She and supporters traveled, via Philadelphia,Troy, New York

Troy is a city in the U.S. state of New York and the county seat of Rensselaer County. The city is located on the western edge of Rensselaer County and on the eastern bank of the Hudson River. Troy has close ties to the nearby cities of Albany ...

, and Rutland, Vermont, to John Brown's Farm

The John Brown Farm State Historic Site includes the home and final resting place of abolitionist John Brown (1800–1859). It is located on John Brown Road in the town of North Elba, 3 miles (5 km) southeast of Lake Placid, New York, where ...

, in North Elba, New York

North Elba is a town in Essex County, New York, United States. The population was 8,957 at the 2010 census.

North Elba is on the western edge of the county. It is by road southwest of Plattsburgh, south-southwest of Montreal, and north of ...

, near the modern village of Lake Placid. The funeral and burial took place there on December 8, 1859. Rev. Joshua Young

Joshua Young (September 23, 1823 – February 7, 1904) was an abolitionist Congregational Unitarian minister who crossed paths with many famous people of the mid-19th century. He received national publicity, and lost his pulpit (job) for presidi ...

presided. Wendell Phillips

Wendell Phillips (November 29, 1811 – February 2, 1884) was an American abolitionist, advocate for Native Americans, orator, and attorney.

According to George Lewis Ruffin, a Black attorney, Phillips was seen by many Blacks as "the one whit ...

spoke.

Aftermath

"In the minds of Southerners, Brown was the greatest threat to slavery the South had ever witnessed." His execution on December 2 was what most white Southerners wanted, but it gave them little relief from their panic. "The South was visibly beside itself with rage and terror." According to Dennis Frye, formerly the chief historian at the

"In the minds of Southerners, Brown was the greatest threat to slavery the South had ever witnessed." His execution on December 2 was what most white Southerners wanted, but it gave them little relief from their panic. "The South was visibly beside itself with rage and terror." According to Dennis Frye, formerly the chief historian at the Harpers Ferry National Historical Park

Harpers Ferry National Historical Park, originally Harpers Ferry National Monument, is located at the confluence of the Potomac and Shenandoah rivers in and around Harpers Ferry, West Virginia. The park includes the historic center of Harpers F ...

, "this was the South's Pearl Harbor

Pearl Harbor is an American lagoon harbor on the island of Oahu, Hawaii, west of Honolulu. It was often visited by the Naval fleet of the United States, before it was acquired from the Hawaiian Kingdom by the U.S. with the signing of the ...

, its ground zero

In relation to nuclear explosions and other large bombs, ground zero (also called surface zero) is the point on the Earth's surface closest to a detonation. In the case of an explosion above the ground, ''ground zero'' is the point on the groun ...

". Northern-inspired revolt of their allegedly happy enslaved was the South's worst nightmare, and it was taken for granted that others would soon follow in Brown's footsteps.

In the North the result was the opposite. "We shall be a thousand times more Anti-Slavery than we ever dared to think of being before," proclaimed a Massachusetts newspaper. "The attempt of Joan Brown has not had much effect, but the manner in which that attempt is received at the North is what has done the injury. The orations, speeches, sympathy, approvals, the proposal to toll bells, close stores, &c., without any public manifestation to the contrary, has created a state of feeling at the South that is not to be described."

Meetings

Across the North, except for the large cities which feared the economic effect of Southern secession (Boston, New York, Philadelphia), the day Brown was hanged was treated as a day of national calamity: bells were rung, meetings held, speeches and sermons given, the flag flown at half-mast. "' The times that tried men's souls' have come again." "Martyr Services, as they were called, were held in many Northern localities." Huge prayer meetings were held inConcord

Concord may refer to:

Meaning "agreement"

* Pact or treaty, frequently between nations (indicating a condition of harmony)

* Harmony, in music

* Agreement (linguistics), a change in the form of a word depending on grammatical features of other ...

, New Bedford

New Bedford (Massachusett: ) is a city in Bristol County, Massachusetts. It is located on the Acushnet River in what is known as the South Coast region. Up through the 17th century, the area was the territory of the Wampanoag Native American pe ...

, and Plymouth, Massachusetts

Plymouth (; historically known as Plimouth and Plimoth) is a town in Plymouth County, Massachusetts, United States. Located in Greater Boston, the town holds a place of great prominence in American history, folklore, and culture, and is known a ...

, and many other cities. Churches and temples were full of mourners. The chapel of Yale College

Yale College is the undergraduate college of Yale University. Founded in 1701, it is the original school of the university. Although other Yale schools were founded as early as 1810, all of Yale was officially known as Yale College until 1887, ...

was draped in mourning. In New York City, "lectures, discourses, speeches and poems are delivered every night everywhere, by everybody, pro and con, on John Brown, on Osawatomie Brown, on Old Brown, on Captain Brown, and on The Hero of Harper's Ferry. ...Truly this old farmer has made such a stir as not all the statesmen, ...little giants, and professional agitators have been able to produce, and which they are much less able to quiet."

In Concord, Massachusetts

Concord () is a town in Middlesex County, Massachusetts, in the United States. At the 2020 census, the town population was 18,491. The United States Census Bureau considers Concord part of Greater Boston. The town center is near where the confl ...

, a ceremony was held at the Town Hall, in which an organ had been placed for the occasion. Henry Thoreau

Henry David Thoreau (July 12, 1817May 6, 1862) was an American naturalist, essayist, poet, and philosopher. A leading transcendentalist, he is best known for his book ''Walden'', a reflection upon simple living in natural surroundings, and h ...

was a key speaker, as was Ralph Waldo Emerson

Ralph Waldo Emerson (May 25, 1803April 27, 1882), who went by his middle name Waldo, was an American essayist, lecturer, philosopher, abolitionist, and poet who led the transcendentalist movement of the mid-19th century. He was seen as a cham ...

. The "celebrated" words of President Thomas Jefferson