Vine–Matthews–Morley Hypothesis on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Vine–Matthews–Morley hypothesis, also known as the Morley–Vine–Matthews hypothesis, was the first key scientific test of the

The Vine–Matthews–Morley hypothesis, also known as the Morley–Vine–Matthews hypothesis, was the first key scientific test of the

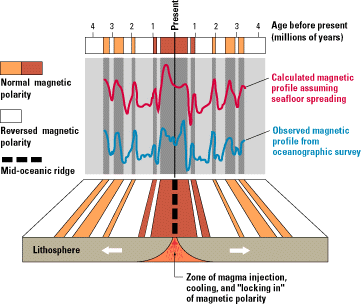

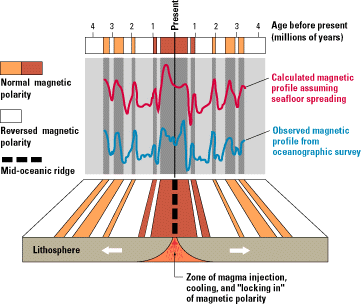

The Vine–Matthews-Morley hypothesis correlates the symmetric magnetic patterns seen on the seafloor with geomagnetic field reversals. At mid-ocean ridges, new crust is created by the injection, extrusion, and solidification of magma. After the magma has cooled through the

The Vine–Matthews-Morley hypothesis correlates the symmetric magnetic patterns seen on the seafloor with geomagnetic field reversals. At mid-ocean ridges, new crust is created by the injection, extrusion, and solidification of magma. After the magma has cooled through the

The Vine–Matthews–Morley hypothesis, also known as the Morley–Vine–Matthews hypothesis, was the first key scientific test of the

The Vine–Matthews–Morley hypothesis, also known as the Morley–Vine–Matthews hypothesis, was the first key scientific test of the seafloor spreading

Seafloor spreading, or seafloor spread, is a process that occurs at mid-ocean ridges, where new oceanic crust is formed through volcanic activity and then gradually moves away from the ridge.

History of study

Earlier theories by Alfred Wegener ...

theory of continental drift

Continental drift is a highly supported scientific theory, originating in the early 20th century, that Earth's continents move or drift relative to each other over geologic time. The theory of continental drift has since been validated and inc ...

and plate tectonics

Plate tectonics (, ) is the scientific theory that the Earth's lithosphere comprises a number of large tectonic plates, which have been slowly moving since 3–4 billion years ago. The model builds on the concept of , an idea developed durin ...

. Its key impact was that it allowed the rates of plate motions at mid-ocean ridge

A mid-ocean ridge (MOR) is a undersea mountain range, seafloor mountain system formed by plate tectonics. It typically has a depth of about and rises about above the deepest portion of an ocean basin. This feature is where seafloor spreading ...

s to be computed. It states that the Earth's oceanic crust acts as a recorder of reversals in the geomagnetic field direction as seafloor spreading takes place.

History

Harry Hess proposed theseafloor spreading

Seafloor spreading, or seafloor spread, is a process that occurs at mid-ocean ridges, where new oceanic crust is formed through volcanic activity and then gradually moves away from the ridge.

History of study

Earlier theories by Alfred Wegener ...

hypothesis in 1960 (published in 1962); the term "spreading of the seafloor" was introduced by geophysicist Robert S. Dietz in 1961. According to Hess, seafloor was created at mid-oceanic ridges by the convection of the Earth's mantle, pushing and spreading the older crust away from the ridge. Geophysicist Frederick John Vine and the Canadian geologist Lawrence W. Morley independently realized that if Hess's seafloor spreading theory was correct, then the rocks surrounding the mid-oceanic ridges should show symmetric patterns of magnetization reversals using newly collected magnetic surveys. Both of Morley's letters to ''Nature

Nature is an inherent character or constitution, particularly of the Ecosphere (planetary), ecosphere or the universe as a whole. In this general sense nature refers to the Scientific law, laws, elements and phenomenon, phenomena of the physic ...

'' (February 1963) and ''Journal of Geophysical Research

The ''Journal of Geophysical Research'' is a peer-reviewed scientific journal. It is the flagship journal of the American Geophysical Union. It contains original research on the physical, chemical, and biological processes that contribute to the u ...

'' (April 1963) were rejected, hence Vine and his PhD adviser at Cambridge University, Drummond Hoyle Matthews, were first to publish the theory in September 1963. Some colleagues were skeptical of the hypothesis because of the numerous assumptions made—seafloor spreading, geomagnetic reversals, and remanent magnetism—all hypotheses that were still not widely accepted. The Vine–Matthews–Morley hypothesis describes the magnetic reversals of oceanic crust. Further evidence for this hypothesis came from Allan V. Cox and colleagues (1964) when they measured the remanent magnetization of lavas from land sites. Walter C. Pitman and J. R. Heirtzler offered further evidence with a remarkably symmetric magnetic anomaly profile from the Pacific-Antarctic Ridge.

Marine magnetic anomalies

The Vine–Matthews-Morley hypothesis correlates the symmetric magnetic patterns seen on the seafloor with geomagnetic field reversals. At mid-ocean ridges, new crust is created by the injection, extrusion, and solidification of magma. After the magma has cooled through the

The Vine–Matthews-Morley hypothesis correlates the symmetric magnetic patterns seen on the seafloor with geomagnetic field reversals. At mid-ocean ridges, new crust is created by the injection, extrusion, and solidification of magma. After the magma has cooled through the Curie point

In physics and materials science, the Curie temperature (''T''C), or Curie point, is the temperature above which certain materials lose their magnet, permanent magnetic properties, which can (in most cases) be replaced by magnetization, induced ...

, ferromagnetism becomes possible and the magnetization direction of magnetic minerals in the newly formed crust orients parallel to the current background geomagnetic field vector

Vector most often refers to:

* Euclidean vector, a quantity with a magnitude and a direction

* Disease vector, an agent that carries and transmits an infectious pathogen into another living organism

Vector may also refer to:

Mathematics a ...

. Once fully cooled, these directions are locked into the crust and it becomes permanently magnetized. Lithospheric creation at the ridge is considered continuous and symmetrical as the new crust intrudes into the diverging plate boundary. The old crust moves laterally and equally on either side of the ridge. Therefore, as geomagnetic reversals occur, the crust on either side of the ridge will contain a record of remanent normal (parallel) or reversed (antiparallel) magnetizations in comparison to the current geomagnetic field. A magnetometer

A magnetometer is a device that measures magnetic field or magnetic dipole moment. Different types of magnetometers measure the direction, strength, or relative change of a magnetic field at a particular location. A compass is one such device, ...

towed above (near bottom, sea surface, or airborne) the seafloor will record positive (high) or negative (low) magnetic anomalies when over crust magnetized in the normal or reversed direction. The ridge crest is analogous to “twin-headed tape recorder”, recording the Earth's magnetic history.

Typically there are positive magnetic anomalies over normally magnetized crust and negative anomalies over reversed crust. Local anomalies with a short wavelength

In physics and mathematics, wavelength or spatial period of a wave or periodic function is the distance over which the wave's shape repeats.

In other words, it is the distance between consecutive corresponding points of the same ''phase (waves ...

also exist, but are considered to be correlated with bathymetry

Bathymetry (; ) is the study of underwater depth of ocean floors ('' seabed topography''), river floors, or lake floors. In other words, bathymetry is the underwater equivalent to hypsometry or topography. The first recorded evidence of wate ...

. Magnetic anomalies over mid-ocean ridges are most apparent at high magnetic latitudes, over north-south trending ridges at all latitudes away from the magnetic equator

Magnetic dip, dip angle, or magnetic inclination is the angle made with the horizontal by Earth's magnetic field, Earth's magnetic field lines. This angle varies at different points on Earth's surface. Positive values of inclination indicate t ...

, and east-west trending spreading ridges at the magnetic equator.

The intensity of the remanent magnetization in the crust is greater than the induced magnetization. Consequently, the shape and amplitude of the magnetic anomaly is controlled predominately by the primary remanent vector in the crust. In addition, where the anomaly is measured on Earth affects its shape when measured with a magnetometer. This is because the field vector generated by the magnetized crust and the direction of the Earth's magnetic field vector are both measured by the magnetometers used in marine surveys. Because the Earth's field vector is much stronger than the anomaly field, a modern magnetometer measures the sum of the Earth's field and the component of the anomaly field in the direction of the Earth's field.

Sections of crust magnetized at high latitudes have magnetic vectors that dip steeply downward in a normal geomagnetic field. However, close to the magnetic south pole, magnetic vectors are inclined steeply upwards in a normal geomagnetic field. Therefore, in both these cases the anomalies are positive. At the equator the Earth's field vector is horizontal so that crust magnetized there will also align horizontal. Here, the orientation of the spreading ridge affects the anomaly shape and amplitude. The component of the vector that effects the anomaly is at a maximum when the ridge is aligned east-west and the magnetic profile crossing is north-south.

Impact

The hypothesis links seafloor spreading and geomagnetic reversals in a powerful manner, with each expanding knowledge of the other. Early in the history of investigating the hypothesis only a short record of geomagnetic field reversals was available for studies of rocks on land. This was sufficient to allow computing of spreading rates over the last 700,000 years on many mid-ocean ridges by locating the closest reversed crust boundary to the crest of a mid-ocean ridge. Marine magnetic anomalies were found later to span the vast flanks of the ridges. Drillcores into the crust on these ridge flanks allowed dating of the early and of the older anomalies. This in turn allowed design of a predicted geomagnetic time scale. With time, investigations married land and marine data to produce an accurate geomagnetic reversal time scale for almost 200 million years.See also

* Edward Bullard * Drummond Matthews * Walter C. Pitman III * Frederick Vine *Geodynamo

In physics, the dynamo theory proposes a mechanism by which a celestial body such as Earth or a star generates a magnetic field. The dynamo theory describes the process through which a rotating, convecting, and electrically conducting fluid can ...

* Lamont–Doherty Earth Observatory

The Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory (LDEO) is a research, research institution specializing in the Earth science and climate change. Though part of Columbia University, it is located on a separate closed campus in Palisades, New York.

The obs ...

References

* * *External links

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Vine-Matthews-Morley hypothesis Geophysics History of Earth science Plate tectonics Geology theories