Vestments controversy on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The vestments controversy or vestarian controversy arose in the English Reformation, ostensibly concerning

While under arrest, Crowley published three editions (including one in

While under arrest, Crowley published three editions (including one in

Early English Books Online

(EEBO).'' * John Hooper, "Ex libro D. Hoperi, Reg. Consiliarijs ab ipso. exhibiti. 3. October. 1550. contra vsum vestium quibis in sacro Ministerio vitur Ecclesia Anglicana. quem librum sic orditur". Text printed in C. Hopf, "Bishop Hooper's 'Notes' to the King's Council", ''Journal of Theological Studies'' 44 (January–April, 1943): 194–99. * Nicholas Ridley, "Reply of Bishop Ridley to Bishop Hooper on the Vestment Controversy, 1550", in John Bradford, ''Writings'', ed. A. Townsend for the Parker Society (Cambridge, 1848, 1853): 2.373–95. * * John Stow, ''Historical Memoranda'' (

In Pursuit of Plainness: The Puritan Principle of Worship

English Reformation Elizabethan Puritanism Protestantism-related controversies

vestment

Vestments are liturgical garments and articles associated primarily with the Christian religion, especially by Eastern Churches, Catholics (of all rites), Anglicans, and Lutherans. Many other groups also make use of liturgical garments; this ...

s or clerical dress. Initiated by John Hooper's rejection of clerical vestments in the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Britai ...

under Edward VI

Edward VI (12 October 1537 – 6 July 1553) was King of England and King of Ireland, Ireland from 28 January 1547 until his death in 1553. He was crowned on 20 February 1547 at the age of nine. Edward was the son of Henry VIII and Jane Seymour ...

as described by the 1549 ''Book of Common Prayer'' and 1550 ordinal, it was later revived under Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was Queen of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. Elizabeth was the last of the five House of Tudor monarchs and is sometimes referred to as the "Virgin Queen".

Eli ...

. It revealed concerns within the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Britai ...

over ecclesiastical identity, doctrine and church practices.

Formulations

The vestments controversy is also known as the ''vestiarian crisis'' or, especially in its Elizabethan manifestation, the ''edification crisis''. The latter term arose from the debate over whether or not vestments, if they are deemed a "thing indifferent" (''adiaphoron

Adiaphoron (; plural: adiaphora; from the Greek (pl. ), meaning "not different or differentiable") is the negation of ''diaphora'', "difference".

In Cynicism, adiaphora represents indifference to the s of life. In Pyrrhonism, it indicates thing ...

''), should be tolerated if they are "edifying"—that is, beneficial. Their indifference and beneficial status were key points of disagreement. The term ''edification'' comes from 1 Corinthians

The First Epistle to the Corinthians ( grc, Α΄ ᾽Επιστολὴ πρὸς Κορινθίους) is one of the Pauline epistles, part of the New Testament of the Christian Bible. The epistle is attributed to Paul the Apostle and a co-auth ...

14:26, which reads in the 1535 Coverdale Bible: "How is it then brethren? Whan ye come together, euery one hath a psalme, hath doctryne, hath a tunge, hath a reuelacion, hath an interpretacion. Let all be done to edifyenge."

As Norman Jones writes:

In section 13 of the Act of Uniformity 1559

The Act of Uniformity 1558 was an Act of the Parliament of England, passed in 1559, to regularise prayer, divine worship and the administration of the sacraments in the Church of England. The Act was part of the Elizabethan Religious Settlemen ...

, if acting on the advice of her commissioners for ecclesiastical causes or the metropolitan, the monarch had the authority "to ordeyne and publishe suche further Ceremonies or rites as maye bee most meet for the advancement of Goddes Glorye, the edifieing of his church and the due Reverance of Christes holye mistries and Sacramentes."

During the reign of Edward VI

John Hooper, having been exiled during King Henry's reign, returned to England in 1548 from the churches inZürich

, neighboring_municipalities = Adliswil, Dübendorf, Fällanden, Kilchberg, Maur, Oberengstringen, Opfikon, Regensdorf, Rümlang, Schlieren, Stallikon, Uitikon, Urdorf, Wallisellen, Zollikon

, twintowns = Kunming, San Francisco

Zürich () i ...

that had been reformed by Zwingli

Huldrych or Ulrich Zwingli (1 January 1484 – 11 October 1531) was a leader of the Reformation in Switzerland, born during a time of emerging Swiss patriotism and increasing criticism of the Swiss mercenary system. He attended the Unive ...

and Bullinger in a highly iconoclastic fashion. Hooper became a leading Protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

reformer in England under the patronage of Edward Seymour, 1st Duke of Somerset

Edward Seymour, 1st Duke of Somerset (150022 January 1552) (also 1st Earl of Hertford, 1st Viscount Beauchamp), also known as Edward Semel, was the eldest surviving brother of Queen Jane Seymour (d. 1537), the third wife of King Henry ...

and subsequently John Dudley, 1st Duke of Northumberland. Hooper's fortunes were unchanged when power shifted from Somerset to Northumberland, since Northumberland also favoured Hooper's reformist agenda.

When Hooper was invited to give a series of Lenten

Lent ( la, Quadragesima, 'Fortieth') is a solemn religious observance in the liturgical calendar commemorating the 40 days Jesus spent fasting in the desert and enduring temptation by Satan, according to the Gospels of Matthew, Mark and Luke, ...

sermons

A sermon is a religious discourse or oration by a preacher, usually a member of clergy. Sermons address a scriptural, theological, or moral topic, usually expounding on a type of belief, law, or behavior within both past and present contexts. El ...

before the king in February 1550, he spoke against the 1549 ordinal whose oath mentioned "all saints" and required newly elected bishops and those attending the ordination ceremony to wear a cope

The cope (known in Latin as ''pluviale'' 'rain coat' or ''cappa'' 'cape') is a liturgical vestment, more precisely a long mantle or cloak, open in front and fastened at the breast with a band or clasp. It may be of any liturgical colours, litu ...

and surplice

A surplice (; Late Latin ''superpelliceum'', from ''super'', "over" and ''pellicia'', "fur garment") is a liturgical vestment of Western Christianity. The surplice is in the form of a tunic of white linen or cotton fabric, reaching to th ...

. In Hooper's view, these requirements were vestiges of Judaism

Judaism ( he, ''Yahăḏūṯ'') is an Abrahamic, monotheistic, and ethnic religion comprising the collective religious, cultural, and legal tradition and civilization of the Jewish people. It has its roots as an organized religion in the ...

and Roman Catholicism

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

, which had no biblical warrant for authentic Christians since they were not used in the early Christian church.

Summoned to answer to the Privy Council and archbishop—who were primarily concerned with Hooper's willingness to accept the royal supremacy, which was also part of the oath for newly ordained clergy—Hooper evidently made sufficient reassurances, as he was soon appointed to the bishopric

In church governance, a diocese or bishopric is the ecclesiastical district under the jurisdiction of a bishop.

History

In the later organization of the Roman Empire, the increasingly subdivided provinces were administratively associate ...

of Gloucester

Gloucester ( ) is a cathedral city and the county town of Gloucestershire in the South West of England. Gloucester lies on the River Severn, between the Cotswolds to the east and the Forest of Dean to the west, east of Monmouth and east of t ...

. Hooper declined the office, however, because of the required vestments and oath by the saints. This action violated the 1549 Act of Uniformity, which made declining the appointment without good cause, a crime against the king and state, so Hooper was called to answer to the king. The king accepted Hooper's position, but the Privy Council did not. Called before them on 15 May 1550, a compromise was reached. Vestments were to be considered a matter of ''adiaphora'', or ''Res Indifferentes'' ("things indifferent", as opposed to an article of faith), and Hooper could be ordained without them at his discretion, but he must allow others wear them.

Hooper passed confirmation of the new office again before the king and council on 20 July 1550, when the issue was raised again, and Archbishop Thomas Cranmer

Thomas Cranmer (2 July 1489 – 21 March 1556) was a leader of the English Reformation and Archbishop of Canterbury during the reigns of Henry VIII, Edward VI and, for a short time, Mary I. He helped build the case for the annulment of Henry ...

was instructed that Hooper was not to be charged "with an oath burdensome to his conscience". Cranmer, however, assigned Nicholas Ridley, Bishop of London

A bishop is an ordained clergy member who is entrusted with a position of Episcopal polity, authority and oversight in a religious institution.

In Christianity, bishops are normally responsible for the governance of dioceses. The role or offic ...

, to perform the consecration, and Ridley refused to do anything but follow the form of the ordinal as it had been prescribed by the Parliament of England

The Parliament of England was the legislature of the Kingdom of England from the 13th century until 1707 when it was replaced by the Parliament of Great Britain. Parliament evolved from the great council of bishops and peers that advised ...

.

A reformist himself, and not always a strict follower of the ordinal, Ridley, it seems likely, had some particular objection to Hooper. It has been suggested that Henrician exiles like Hooper, who had experienced some of the more radically reformed churches on the continent, were at odds with English clergy who had accepted and never left the established church. John Henry Primus

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Seco ...

also notes that on July 24, 1550, the day after receiving instructions for Hooper's unique consecration, the church of the Austin Friars

Austin Friars is a coeducational independent day school located in Carlisle, England. The Senior School provides secondary education for 350 boys and girls aged 11–18. There are 150 children aged 4–11 in the Junior School and the Nursery ha ...

in London had been granted for use as a Stranger church

Strangers' church was a term used by English-speaking people for independent Protestant churches established in foreign lands or by foreigners in England during the Reformation. (The spelling stranger church is also found in texts of the period ...

with the freedom to employ their own rites and ceremonies. This development—the use of a London church virtually outside Ridley's jurisdiction—was one that Hooper had had a hand in.

The Privy Council reiterated its position, and Ridley responded in person, agreeing that vestments are indifferent but making a compelling argument that the monarch may require indifferent things without exception. The council became divided in opinion, and the issue dragged on for months without resolution. Hooper now insisted that vestments were not indifferent, since they obscured the priesthood of Christ by encouraging hypocrisy and superstition

A superstition is any belief or practice considered by non-practitioners to be irrational or supernatural, attributed to fate or magic, perceived supernatural influence, or fear of that which is unknown. It is commonly applied to beliefs an ...

. Warwick disagreed, emphasising that the king must be obeyed in things indifferent, and he pointed to St Paul's concessions to Jewish traditions in the early church. Finally, an acrimonious debate with Ridley went against Hooper. Ridley's position centred on maintaining order and authority; not the vestments themselves, Hooper's primary concern.

Biblical texts cited in this and subsequent debates—and the ways in which they were interpreted—came to be defining features of conservative and puritan Protestant discourse. They were echoed elsewhere, such as the famous glosses of the Geneva Bible

The Geneva Bible is one of the most historically significant translations of the Bible into English, preceding the King James Version by 51 years. It was the primary Bible of 16th-century English Protestantism and was used by William Shakespea ...

.

Hooper–Ridley debate

In aLatin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power ...

letter dated October 3, 1550, Hooper laid out his argument ''contra usum vestium''. He argued that vestments should not be used as they are not indifferent, nor is their use supported by scripture. He contends that church practices must either have express biblical support or be things indifferent, approval for which is implied by scripture. He then all but excludes the possibility of anything being indifferent in the four conditions he sets:

Hooper cites Romans 14:23b (whatsoever is not of faith is sin), Romans 10:17 (faith cometh from hearing, and hearing by the word of God), and Matthew 15:13 (every plant not planted by God will be rooted up) to argue that indifferent things must be done in faith, and since what cannot be proved from scripture is not of faith, indifferent things must be proved from scripture, which is both necessary and sufficient authority, as opposed to tradition. He maintains that priestly garb distinguishing clergy from laity is not indicated by scripture; there is no mention of it in the New Testament

The New Testament grc, Ἡ Καινὴ Διαθήκη, transl. ; la, Novum Testamentum. (NT) is the second division of the Christian biblical canon. It discusses the teachings and person of Jesus, as well as events in first-century Christ ...

as being in use in the early church, and the use of priestly clothing in the Old Testament

The Old Testament (often abbreviated OT) is the first division of the Christian biblical canon, which is based primarily upon the 24 books of the Hebrew Bible or Tanakh, a collection of ancient religious Hebrew writings by the Israelites. The ...

is a Hebrew practice, a type

Type may refer to:

Science and technology Computing

* Typing, producing text via a keyboard, typewriter, etc.

* Data type, collection of values used for computations.

* File type

* TYPE (DOS command), a command to display contents of a file.

* Ty ...

or foreshadowing that finds its antitype in Christ, who abolishes the old order and recognises the spiritual equality, or priesthood, of all Christians. The historicity of these claims is supported by reference to Polydore Vergil

Polydore Vergil or Virgil (Italian: ''Polidoro Virgili''; commonly Latinised as ''Polydorus Vergilius''; – 18 April 1555), widely known as Polydore Vergil of Urbino, was an Italian humanist scholar, historian, priest and diplomat, who spent ...

's ''De Inventoribus Rerum''.

In response, Ridley rejected Hooper's insistence on biblical origins and countered Hooper's interpretations of his chosen biblical texts. He pointed out that many non-controversial practices are not mentioned or implied in scripture. Ridley denied that early church practices are normative for the present situation, and he linked such arguments with the Anabaptists

Anabaptism (from Neo-Latin , from the Greek : 're-' and 'baptism', german: Täufer, earlier also )Since the middle of the 20th century, the German-speaking world no longer uses the term (translation: "Re-baptizers"), considering it biased. ...

. Ridley joked that Hooper's reference to Christ's nakedness on the cross is as insignificant as the clothing King Herod put Christ in and "a jolly argument" for the Adamites.

Ridley did not dispute Hooper's main typological argument, but neither did he accept that vestments are necessarily or exclusively identified with Israel and the Roman Catholic Church. On Hooper's point about the priesthood of all believers, Ridley said it does not follow from this doctrine that all Christians must wear the same clothes.

For Ridley, on matters of indifference, one must defer conscience to the authorities of the church, or else "thou showest thyself a disordered person, disobedient, as contemner of lawful authority, and a wounder of thy weak brother his conscience." For him, the debate was finally about legitimate authority, not the merits and demerits of vestments themselves. He contended that it is only accidental that the compulsory ceases to be indifferent; the degeneration of a practice into non-indifference can be corrected without throwing out the practice. Things are not, "because they have been abused, to be taken away, but to be reformed and amended, and so kept still."

For this point, Hooper cites 1 Corinthians 14 and 2 Corinthians 13. As it contradicts the first point above, Primus contends that Hooper must now refer to indifferent things in the church and earlier meant indifferent things in general, in the abstract. The apparent contradiction was seized by Ridley and undoubtedly hurt Hooper's case with the council.

Ridley warned Hooper of the implications of an attack on English ecclesiastical and civil authority and of the consequences of radical individual liberties, while also reminding him that it was Parliament that established the "Book of Common Prayer

The ''Book of Common Prayer'' (BCP) is the name given to a number of related prayer books used in the Anglican Communion and by other Christianity, Christian churches historically related to Anglicanism. The original book, published in 1549 ...

in the church of England".

Outcome of the Edwardian controversy

Hooper accepted neither Ridley's rejoinder, nor the offer of a compromise.Heinrich Bullinger

Heinrich Bullinger (18 July 1504 – 17 September 1575) was a Swiss Reformer and theologian, the successor of Huldrych Zwingli as head of the Church of Zürich and a pastor at the Grossmünster. One of the most important leaders of the Swiss Ref ...

, Pietro Martire Vermigli, and Martin Bucer, while agreeing with Hooper's views, ceased to support him; only John a Lasco

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Second ...

remained an ally.

Some time in mid-December 1550, Hooper was put under house arrest, during which time he wrote and published ''A godly Confession and of the Christian faith'', an effort at self-vindication in the form of 21 articles in a general confession of faith. In it, Hooper denounced Anabaptism

Anabaptism (from Neo-Latin , from the Greek : 're-' and 'baptism', german: Täufer, earlier also )Since the middle of the 20th century, the German-speaking world no longer uses the term (translation: "Re-baptizers"), considering it biased ...

and emphasised obedience to civil authorities. Because of this publication, his persistent nonconformism, and violations of the terms of his house arrest, Hooper was placed in Thomas Cranmer

Thomas Cranmer (2 July 1489 – 21 March 1556) was a leader of the English Reformation and Archbishop of Canterbury during the reigns of Henry VIII, Edward VI and, for a short time, Mary I. He helped build the case for the annulment of Henry ...

's custody at Lambeth Palace

Lambeth Palace is the official London residence of the Archbishop of Canterbury. It is situated in north Lambeth, London, on the south bank of the River Thames, south-east of the Palace of Westminster, which houses Parliament, on the opposit ...

for two weeks by the Privy Council on January 13, 1551. During this time, Peter Martyr visited Hooper three times in attempts to persuade him to conform but attributed his failure to another visitor, probably John a Lasco, who encouraged the opposite.

Hooper was then sent to Fleet Prison by the council, who made that decision on January 27. John Calvin

John Calvin (; frm, Jehan Cauvin; french: link=no, Jean Calvin ; 10 July 150927 May 1564) was a French theologian, pastor and reformer in Geneva during the Protestant Reformation. He was a principal figure in the development of the system ...

and Bullinger both wrote to him at this time; Calvin counselled Hooper that the issue was not worth such resistance. On February 15, Hooper submitted to consecration in vestments in a letter to Cranmer, was consecrated Bishop of Gloucester on March 8, 1551, and shortly thereafter, preached before the king in vestments. The 1552 revised Prayer Book omitted the vestments rubrics that had been the occasion for the controversy.

Vestments among the Marian exiles

In controversy among the Marian exiles, principally those in Frankfurt, church order and liturgy were the main issues of contention, though vestments were related and debated in their own right. At several points, opponents of the English prayerbook inJohn Knox

John Knox ( gd, Iain Cnocc) (born – 24 November 1572) was a Scottish minister, Reformed theologian, and writer who was a leader of the country's Reformation. He was the founder of the Presbyterian Church of Scotland.

Born in Giffordga ...

's group maligned it by reference to John Hooper's persecution under the Edwardian prayer book and vestments regulations. On the other side, that of Richard Cox, the martyrdom of Hooper and others was blamed on Knox's polemic against Mary I

Mary I (18 February 1516 – 17 November 1558), also known as Mary Tudor, and as "Bloody Mary" by her Protestant opponents, was Queen of England and Ireland from July 1553 and Queen of Spain from January 1556 until her death in 1558. She ...

, Philip II and the emperor, Charles V Charles V may refer to:

* Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor (1500–1558)

* Charles V of Naples (1661–1700), better known as Charles II of Spain

* Charles V of France (1338–1380), called the Wise

* Charles V, Duke of Lorraine (1643–1690)

* Infant ...

.

By 1558, even the supporters of the prayer book had abandoned the Edwardian regulations on clerical dress. All the Marian exiles—even the leading promoters of the English prayer book such as Cox–had given up the use of vestments by the time of their return to England under Elizabeth I, according to John Strype

John Strype (1 November 1643 – 11 December 1737) was an English clergyman, historian and biographer from London. He became a merchant when settling in Petticoat Lane. In his twenties, he became perpetual curate of Theydon Bois, Essex and l ...

's ''Annals of the Reformation''. This seeming unity did not last.

During the troubles in the English exile congregation in Frankfurt, some people shifted sides that would shift again upon their return to England, and certainly, there was no direct correlation between one's views on church order and one's views on clerical dress. Nevertheless, there is a general pattern wherein the members of the "prayer book party" were favoured for high appointments in the church under Elizabeth I that required conformity on vestments, as opposed to the exiles who departed from the order of the English national church in favour of the more international, continental, reformed order. Occupying many lower positions in the Elizabethan church, this latter group grew during the exile period and produced many of the leaders of the Elizabethan anti-vestments faction. As deans, prebends, and parish priests, they were freer to disobey openly, en masse, the requirements for clerical dress.

Notably, some of the leaders of the Elizabethan anti-vestments campaign spent time in Calvin's Geneva

Geneva ( ; french: Genève ) frp, Genèva ; german: link=no, Genf ; it, Ginevra ; rm, Genevra is the second-most populous city in Switzerland (after Zürich) and the most populous city of Romandy, the French-speaking part of Switzerland. Situ ...

, many of them following the successful takeover of the Frankfurt congregation and ouster of John Knox

John Knox ( gd, Iain Cnocc) (born – 24 November 1572) was a Scottish minister, Reformed theologian, and writer who was a leader of the country's Reformation. He was the founder of the Presbyterian Church of Scotland.

Born in Giffordga ...

by the pro-prayerbook group. In Geneva, these men were immersed in a reformed community that had no place for vestments at all, whereas the exiles who became Elizabethan bishops (and thus had to accept the use of vestments) never visited Geneva except for James Pilkington, Thomas Bentham

Thomas Bentham (1513/14–1579) was a scholar and a Protestant minister. One of the Marian exiles, he returned to England to minister to an underground congregation in London. He was made the first Elizabethan bishop of Coventry and Lichfield, se ...

and John Scory. Yet these three, or at least Pilkington for certain, were hostile toward vestments and sympathetic to nonconformists under Elizabeth I, though Cox and Grindal also showed such sympathies.

During the reign of Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I sought unity with her first parliament in 1559 and did not encourage nonconformity. Under herAct of Uniformity 1559

The Act of Uniformity 1558 was an Act of the Parliament of England, passed in 1559, to regularise prayer, divine worship and the administration of the sacraments in the Church of England. The Act was part of the Elizabethan Religious Settlemen ...

, backed by the Act of Supremacy

The Acts of Supremacy are two acts passed by the Parliament of England in the 16th century that established the English monarchs as the head of the Church of England; two similar laws were passed by the Parliament of Ireland establishing the ...

, the 1552 Prayer Book was to be the model for ecclesiastical use, but with a stance on vestments that went back to the second year of Edward VI's reign. The alb, cope

The cope (known in Latin as ''pluviale'' 'rain coat' or ''cappa'' 'cape') is a liturgical vestment, more precisely a long mantle or cloak, open in front and fastened at the breast with a band or clasp. It may be of any liturgical colours, litu ...

and chasuble

The chasuble () is the outermost liturgical vestment worn by clergy for the celebration of the Eucharist in Western-tradition Christian churches that use full vestments, primarily in Roman Catholic, Anglican, and Lutheran churches. In the Easter ...

were all to be brought back into use, where some exiles had even abandoned the surplice

A surplice (; Late Latin ''superpelliceum'', from ''super'', "over" and ''pellicia'', "fur garment") is a liturgical vestment of Western Christianity. The surplice is in the form of a tunic of white linen or cotton fabric, reaching to th ...

. The queen assumed direct control over these rules and all ceremonies or rites.

Anticipating further problems with vestments, Thomas Sampson corresponded with Peter Martyr Vermigli on the matter. Martyr's advice, along with Bullinger's, was to accept vestments but also to preach against them. However, Sampson, Lever, and others were unsatisfied with the lack of such protest from Elizabeth's bishops, such as Cox, Edmund Grindal, Pilkington, Sandys, Jewel, and Parkhurst, even though some, like Sandys and Grindal, were reluctant conformists with nonconformist sympathies. Archbishop Parker, consecrated by the anti-vestiarian Miles Coverdale

Myles Coverdale, first name also spelt Miles (1488 – 20 January 1569), was an English ecclesiastical reformer chiefly known as a Bible translator, preacher and, briefly, Bishop of Exeter (1551–1553). In 1535, Coverdale produced the first c ...

, was also a major source of discontent.

The Convocation of 1563 saw the victory of a conservative position over some proposed anti-vestiarian revisions to the Prayer Book. Thirty-four delegates to the convocation, including many Marian exiles, brought up seven articles altering the Prayer Book. The articles were subsequently reshaped and reduced to six; they failed to be sent to the Upper House by just one vote, with abstention of some of the sponsors of the original draft. The queen backed Parker over uniformity along the lines of the 1559 Prayer Book.

On March 20, 1563, an appeal was made to the ecclesiastical commissioners by twenty petitioners to exempt them from the use of vestments. These included a number of prominent clergy, mainly in the diocese of London, whose bishop, Grindal, had packed his see with former exiles and activists for reform. The petition was approved by all the commissioners except Parker and Guest, who rejected it.

Sampson and Humphrey were then the first nonconformist leaders to be targeted by Parker. Sampson's quick deprivation in 1565 came because he was directly under the queen's authority. Humphrey, under the jurisdiction of Robert Horne, the Bishop of Winchester

The Bishop of Winchester is the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of Winchester in the Church of England. The bishop's seat ('' cathedra'') is at Winchester Cathedral in Hampshire. The Bishop of Winchester has always held '' ex officio'' (except ...

, was able to return to his position as president of Magdalen College, Oxford, and was later offered by Horne a benefice in Sarum, though with Sarum's bishop, Jewel, opposing this. At this time, Bullinger was counselling Horne with a position more tolerant of vestments, while nonconformist agitation was taking place among students at St John's College, Cambridge

St John's College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge founded by the Tudor matriarch Lady Margaret Beaufort. In constitutional terms, the college is a charitable corporation established by a charter dated 9 April 1511. Th ...

.

March 1566 brought the peak of enforcement against nonconformity, with the Diocese of London targeted as an example, despite Parker's expectation that it would leave many churches "destitute for service this Easter, and that many lergywill forsake their livings, and live at printing, teaching their children, or otherwise as they can." The London clergy were assembled at Lambeth Palace

Lambeth Palace is the official London residence of the Archbishop of Canterbury. It is situated in north Lambeth, London, on the south bank of the River Thames, south-east of the Palace of Westminster, which houses Parliament, on the opposit ...

. Parker had requested but failed to gain the attendance of William Cecil, Lord Keeper Nicholas Bacon, and the Lord Marquess of Northampton, so it was left to Parker himself, bishop Grindal, the dean of Westminster, and some canonist

Canon law (from grc, κανών, , a 'straight measuring rod, ruler') is a set of ordinances and regulations made by ecclesiastical authority (church leadership) for the government of a Christian organization or church and its members. It is the ...

s. One former nonconformist, Robert Cole, was stood before the assembly in full canonical habit. There was no discussion. The ultimatum was issued that the clergy would appear as Cole—in a square cap, gown, tippet, and surplice. They would "inviolably observe the rubric of the Book of Common Prayer, and the Queen majesty's injunctions: and the Book of Convocation." The clergy were ordered to commit themselves on the spot, in writing, with only the words ''volo'' or ''nolo''. Sixty-one subscribed; thirty-seven did not and were immediately suspended with their livings sequestered. A three-month grace period was given for these clergy to change their minds before they would be fully deprived.

The deprivations were to be carried out under the authority of Parker's ''Advertisements

Advertising is the practice and techniques employed to bring attention to a product or service. Advertising aims to put a product or service in the spotlight in hopes of drawing it attention from consumers. It is typically used to promote a ...

'', which he had just published as a revised form of the original articles defining ecclesiastical conformity. Parker had not obtained the crown's authorisation for this mandate, however, though he increasingly relied on the authority of the state. The nonconformist reaction was a vociferous assertion of their persecuted status, with some displays of disobedience. John Stow records in his ''Memoranda'' that in most parishes, the sextons did not change the service if they had conducted it without vestments previously: "The clergy themselves did service in the forbidden gowns and cloaks, and preached violently against the order taken by the Queen in Council, not forbearing to censure the bishops for yielding their consent to it."The term "Puritan

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to purify the Church of England of Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should become more Protestant. P ...

" was first recorded at this time as term of abuse for such nonconformists.

Reactions of protest in 1566

One of those who signed ''nolo'' and a former Marian exile, Robert Crowley, vicar of St Giles-without-Cripplegate, instigated the first open protest. Though he was suspended on March 28 for his nonconformity, he was among many who ignored their suspension. On April 23, Crowley confronted six laymen (some sources say choristers) of St Giles who had come to the church in surplices for a funeral. According to John Stow's ''Memoranda'', Crowley stopped the funeral party at the door. Stow says Crowley declared "the church was his, and the queen had given it him during his life and made him vicar thereof, wherefore he would rule that place and would not suffer any such superstitious rags of Rome there to enter." By another account, Crowley was backed by his Curate and one Sayer who was Deputy of the Ward. In this version, Crowley ordered the men in surplices "to take off these porter's coats", with the Deputy threatening to knock them flat if they broke the peace. Either way, it seems Crowley succeeded in driving off the men in vestments. Stow records two other incidents on April 7,Palm Sunday

Palm Sunday is a Christian moveable feast that falls on the Sunday before Easter. The feast commemorates Christ's triumphal entry into Jerusalem, an event mentioned in each of the four canonical Gospels. Palm Sunday marks the first day of Ho ...

. At Little All Hallows on Thames Street, a nonconforming Scot precipitated a fight with his preaching. (Stow notes that the Scot typically preached twice a day at St Magnus-the-Martyr

St Magnus the Martyr, London Bridge, is a Church of England church and parish within the City of London. The church, which is located in Lower Thames Street near The Monument to the Great Fire of London, is part of the Diocese of London and u ...

, where Coverdale was rector. Coverdale was also ministering to a secret congregation at this time.) The sermon was directed against vestments with "bitter and vehement words" for the queen and conforming clergy. The minister of the church had conformed to preserve his vocation, but he was seen smiling at the preacher's "vehement talk". Noticing this, a dyer and a fishmonger questioned the minister, which led to an argument and a fight between pro- and anti-vestment parishioners. Stow mentions that by June 3, this Scot had changed his tune and was preaching in a surplice. For this, he was attacked by women who threw stones at him, pulled him out of the pulpit, tore his surplice, and scratched his face. Similar disturbances over vestments from 1566 to 1567 are described in Stow's ''Memoranda''.

At St Mary Magdalen, where the minister had apparently been suspended, Stow says the parish succeeded in getting a minister appointed to serve communion on Palm Sunday, but when the conforming minister came away from the altar to read the gospel and epistle, a member of the congregation had his servant steal the cup and bread. This and Crowley's actions were related to Cecil in letters by Parker, who reported that the latter disturbance was instigated "because the bread was not common"—i.e. it was not an ordinary loaf of bread but a wafer that was used for the eucharist

The Eucharist (; from Greek , , ), also known as Holy Communion and the Lord's Supper, is a Christian rite that is considered a sacrament in most churches, and as an ordinance in others. According to the New Testament, the rite was institu ...

. Parker also reported that "divers churchwardens to make a trouble and a difficulty, will provide neither surplice nor bread" (''Archbishop Parker's Correspondence'', 278). Stow indicates there were many other such disturbances throughout the city on Palm Sunday and Easter.

At about this time, Bishop Grindal found that one Bartlett, divinity lecturer at St Giles, had been suspended but was still carrying out that office without a licence. "Three-score women of the same parish" appealed to Grindal on Bartlett's behalf but were rebuffed in preference for "a half-dozen of their husbands", as Grindal reported to Cecil (Grindal's ''Remains'', 288–89). Crowley himself assumed this lectureship before the end of the year after being deprived and placed under house arrest, which indicates the cat-and-mouse game being played at the parish level to frustrate the campaign for conformity.

Crowley's actions at St Giles led to a complaint from the Lord Mayor to Archbishop Parker, and Parker summoned Crowley and Sayer, the Deputy of the Ward. Crowley expressed his willingness to go to prison, insisting he would not allow surplices and would not cease his duties unless he was discharged. Parker told him he was indeed discharged, and Crowley then declared he would only accept discharge from a law court, a clear shot at the weakness of Parker's authority. Crowley was put under house arrest in the custody of the bishop of Ely from June to October. Sayer, the Deputy, was bound over for £100 and was required to appear again before Parker if there was more trouble. Crowley stuck to his principles and was fully deprived after Parker's three-month grace period had elapsed, whereupon he was sent to Cox, the Bishop of Ely. On October 28, an order was issued to the Archbishop of Canterbury and the Bishop of London to settle Crowley's case (''Archbishop Parker's Correspondence'', 275f.). By 1568–69, Crowley had resigned or had been stripped of all his preferments. He returned to the printing trade, although that had been his immediate reaction in 1566 when he led the nonconformists in a bout of literary warfare. (See below.) In the face of such strong opposition from his subordinates and the laity, Parker feared for his life and continued to appeal to Cecil for backing from the government.

Literary warfare

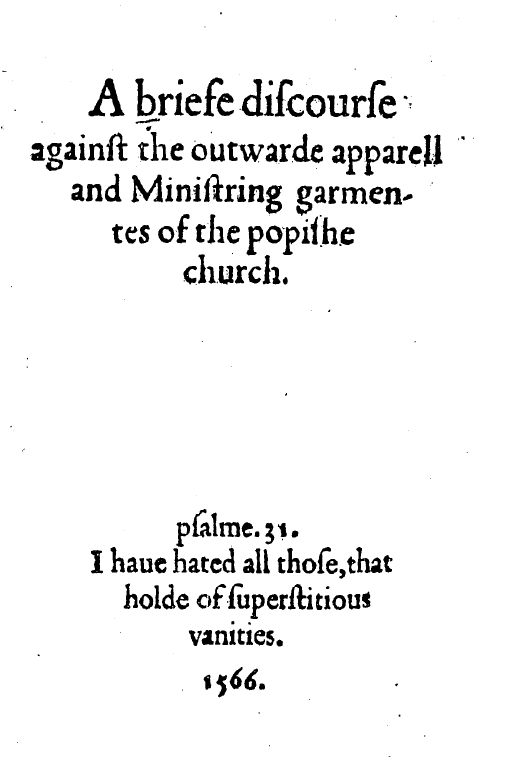

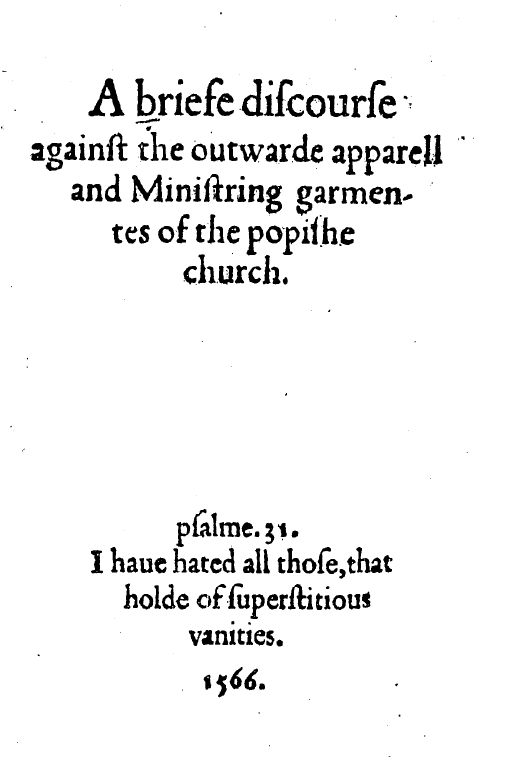

While under arrest, Crowley published three editions (including one in

While under arrest, Crowley published three editions (including one in Emden

Emden () is an independent city and seaport in Lower Saxony in the northwest of Germany, on the river Ems. It is the main city of the region of East Frisia and, in 2011, had a total population of 51,528.

History

The exact founding date of Em ...

) of ''A Briefe Discourse Against the Outwarde Apparel of the Popishe Church'' (1566). Patrick Collinson

Patrick "Pat" Collinson, (10 August 1929 – 28 September 2011) was an English historian, known as a writer on the Elizabethan era, particularly Elizabethan Puritanism. He was emeritus Regius Professor of Modern History, University of Cambridge, ...

has called this "the earliest puritan manifesto". The title page quotes from Psalm

The Book of Psalms ( or ; he, תְּהִלִּים, , lit. "praises"), also known as the Psalms, or the Psalter, is the first book of the ("Writings"), the third section of the Tanakh, and a book of the Old Testament. The title is derived f ...

31; intriguingly, it is closest to the English of the Bishops' Bible (1568): "I have hated all those that holde of superstitious vanities". (See image at right.) Stow claims this work was a collaborative project, with all the nonconforming clergy giving their advice in writing to Crowley. At the same time, many other anti-vestiarian tracts were circulating in the streets and churches. By May, Henry Denham, the printer of ''A briefe Discourse'', had been jailed, but the writers escaped punishment because, according to Stow, "they had friends enough to have set the whole realm together by the ears."

As his title suggests, Crowley inveighed relentlessly against the evil of vestments and stressed the direct responsibility of preachers to God rather than to men. Moreover, he stressed God's inevitable vengeance against the use of vestments and the responsibility of rulers for tolerance of such "vain toys". Arguing for the importance of edification based on 1 Corinthians 13:10, Ephesians 2:19–21 and Ephesians 4:11–17, Crowley states that unprofitable ceremonies and rites must be rejected, including vestments, until it is proved they will edify the church. Taking up the argument that vestments are indifferent, Crowley is clearer than Hooper as he focuses not on indifference in general but indifferent things in the church. Though the tenor of his writing and that of his compatriots is that vestments are inherently evil, Crowley grants that in themselves, they may be things indifferent, but crucially, when their use is harmful, they are no longer indifferent, and Crowley is certain they are harmful in their present use. They are a hindrance to the simple who regard vestments and the office of the priest superstitiously because their use encourages and confirms the papists. Crowley's circumventing of higher ecclesiastical and state authority is the most radical part of the text and defines a doctrine of passive resistance. However, in this, Crowley is close to the "moderate" view espoused by Calvin Calvin may refer to:

Names

* Calvin (given name)

** Particularly Calvin Coolidge, 30th President of the United States

* Calvin (surname)

** Particularly John Calvin, theologian

Places

In the United States

* Calvin, Arkansas, a hamlet

* Calvin T ...

and Bullinger, as opposed to the more radical, active resistance arguments of John Knox

John Knox ( gd, Iain Cnocc) (born – 24 November 1572) was a Scottish minister, Reformed theologian, and writer who was a leader of the country's Reformation. He was the founder of the Presbyterian Church of Scotland.

Born in Giffordga ...

and John Ponet. Nevertheless, Crowley's position was radical enough for his antagonists when he asserted that no human authority may contradict divine disapproval for that which is an abuse, even if the abuse arises from a thing that is indifferent. Crowley presents many other arguments from scripture, and he cites Bucer, Martyr, Ridley and Jewel as anti-vestment supporters. In the end, Crowley attacks his opponents as "bloudy persecuters" whose "purpose is ... to deface the glorious Gospell of Christ Jesus, which thing they shall never be able to bring to passe." A concluding prayer calls to God for the abolition of "al dregs of Poperie and superstition that presently trouble the state of thy Church."

A response to Crowley that is thought to have been commissioned by and/or written by Parker, also in 1566, notes how Crowley's argument challenges the royal supremacy and was tantamount to rebellion. (The full title is ''A Brief Examination for the Tyme of a Certaine Declaration Lately Put in Print in the name and defence of certaine ministers in London, to weare the apparell prescribed by the lawes and orders of the Realme''.) Following an opening that expresses a reluctance to respond to folly, error, ignorance, and arrogance on its own terms, ''A Brief Examination'' engages in a point-by-point refutation of Crowley, wherein Bucer, Martyr and Ridley are marshalled for support. A new development emerges as a rebuttal of Crowley's elaboration of the argument that vestments are wholly negative. Now they are presented as positive goods, bringing more reverence and honor to the sacraments. The evil of disobedience to legitimate authority is a primary theme and is used to respond to the contention that vestments confuse the simple. Rather, it is argued that disobedience to authority is more likely to lead the simple astray. Further, as items conducive to order and decency, vestments are part of the church's general task as defined by Saint Paul

Paul; grc, Παῦλος, translit=Paulos; cop, ⲡⲁⲩⲗⲟⲥ; hbo, פאולוס השליח (previously called Saul of Tarsus;; ar, بولس الطرسوسي; grc, Σαῦλος Ταρσεύς, Saũlos Tarseús; tr, Tarsuslu Pavlus; ...

, though they are not expressly mandated. Appended to the main argument are five translated letters exchanged under Edward VI between Bucer and Cranmer (one has a paragraph omitted that expresses reservations about vestments causing superstition) and between Hooper, a Lasco, Bucer and Martyr.

Following this retort came another nonconformist pamphlet, which J. W. Martin speculatively attributes to Crowley: ''An answere for the Tyme, to the examination put in print, without the author's name, pretending to the prescribed against the declaration of the of London'' (1566). Nothing new is said, but vestments are now emphatically described as idolatrous abuses with reference to radically iconoclastic Old Testament texts. By this point, the idea that vestments are inherently indifferent had been virtually abandoned and seems to be contradicted at one point in the text. The contradiction is resolved, tenuously, with the point that vestments do possess a theoretical indifference apart from all practical considerations, but their past usage (i.e. their abuse) thoroughly determines their present and future evil and non-indifference. The author declares that vestments are monuments "of a thing that is left or set up for a remembraunce, which is Idolatry, and not onely remembraunce, but some aestimacion: therefore they are monumentes of idolatry." The argument in ''A Brief Examination'' for the church's prerogative in establishing practices not expressly mandated in scripture is gleefully attacked as an open door to papistry and paganism: the mass, the pope, purgatory, and even the worship of Neptune are not expressly forbidden, but that does not make them permissible. It becomes clear in the development of this point that the nonconformist faction believed that the Bible always had at least a general relevance to every possible question and activity: "the scripture hath left nothing free or indifferent to mens lawes, but it must agree with those generalle condicions before rehearsed, and such like." On the issue of authority and obedience, the author grants that one should often obey even when evil is commanded by legitimate authorities, but such authority is said not to extend beyond temporal (as opposed to ecclesiastical) matters—a point in which we may see a clear origin of English anti-prelatical/anti-episcopal sentiment and separatism

Separatism is the advocacy of cultural, ethnic, tribal, religious, racial, governmental or gender separation from the larger group. As with secession, separatism conventionally refers to full political separation. Groups simply seeking greate ...

. The author regards it as more dangerous for the monarch to exercise his authority beyond what scripture allows than for subjects to restrain this authority. Every minister must be able to judge the laws to see if they are in line "wyth gods word or no". Moreover, even the lowest in the ecclesiastical hierarchy are ascribed as great an authority regarding "the ministration of the word and sacraments" as any bishop.

Also in 1566, a letter on vestments from Bullinger to Humphrey and Sampson dated May 1 of that year (in response to questions they had posed to him) was published. It was taken as a decisive defence of conformity since it matched the position of the Marian exiles who had accepted bishoprics while hoping for future reforms. Bullinger was incensed by the publication and effect of his letter. It elicited a further nonconformist response in ''The judgement of the Reverend Father Master Henry Bullinger, Pastor of the church of Zurick, in certeyne matters of religion, beinge in controversy in many countreys, even where as the Gospel is taught''. Based on Bullinger's ''Decades'', this tract tried to muster support for nonconformity on vestments from five points not directly related to but underlying that issue: 1) the corrupt nature of traditions and the primacy of scripture, 2) the equality of clergy, 3) the non-exclusive power of the bishops to ordain ministers, 4) the limited scope of the authority of civil magistrates, and 5) the sole headship of Christ in the church—a re-emphasis of the second point.

Two other nonconformist tracts appeared, both deploying established authorities such as St Ambrose

Ambrose of Milan ( la, Aurelius Ambrosius; ), venerated as Saint Ambrose, ; lmo, Sant Ambroeus . was a theologian and statesman who served as Bishop of Milan from 374 to 397. He expressed himself prominently as a public figure, fiercely promo ...

, Theophilactus of Bulgaria, Erasmus

Desiderius Erasmus Roterodamus (; ; English: Erasmus of Rotterdam or Erasmus;''Erasmus'' was his baptismal name, given after St. Erasmus of Formiae. ''Desiderius'' was an adopted additional name, which he used from 1496. The ''Roterodamus'' w ...

, Bucer, Martyr, John Epinus

Johannes Aepinus (Johann Hoeck) (1499–1553) was a German Lutheran theologian, the first Superintendent of Hamburg from 1532 to 1553, presiding as spiritual leader over the Lutheran state church of Hamburg.

Life

He was born at Ziesar or Ziege ...

of Hamburg, Matthias Flacius Illyricus, Philipp Melanchthon

Philip Melanchthon. (born Philipp Schwartzerdt; 16 February 1497 – 19 April 1560) was a German Lutheran reformer, collaborator with Martin Luther, the first systematic theologian of the Protestant Reformation, intellectual leader of the L ...

, a Lasco, Bullinger, Wolfgang Musculus of Bern, and Rodolph Gualter

Rudolf Gwalther (1519–1586) was a Reformed pastor and Protestant reformer who succeeded Heinrich Bullinger as Antistes of the Zurich church.

Life

Gwalther was born the son of a carpenter, who died when he was young. Heinrich Bullinger a ...

. These were ''The mynd and exposition of that excellente learned man Martyn Bucer, upon these wordes of S. Matthew: woo be to the wordle bycause of offences. Matth. xviii'' (1566) and ''The Fortress of Fathers, ernestlie defending the puritie of Religion and Ceremonies, by the trew exposition of certaine places of Scripture: against such as wold bring an Abuse of Idol , and of thinges indifferent, and do th' authority of Princes and Prelates larger than the truth is'' (1566). New developments in these pamphlets are the use of arguments against English prelates that were originally aimed at the Roman church, the labelling of the conformist opposition as Antichrist, and advocacy for separation from such evil. Such sharp material militates in favour of taking 1566 as beginning of English Presbyterianism

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their na ...

, at least in a theoretical sense.

A conformist response answered in the affirmative the question posed in its title, ''Whether it be mortall sinne to transgresse civil lawes, which be the commaundementes of civill Magistrates'' (1566). This text also drew on Melanchthon, Bullinger, Gualter, Bucer, and Martyr. Eight letters between ecclesiastics from the reign of Edward VI to Elizabeth were included, and a no longer extant tract thought to have been written by Cox or Jewel is discussed at some length. Following suit, a non-conformist collection of letters (''To my lovynge brethren that is about the popishe , two short and comfortable Epistels'') by Anthony Gilby and James Pilkington was published in Emden by E. Van der Erve. The collection begins with an undated, unaddressed letter, but it appears in another tract attributed to Gilby (''A pleasaunt Dialogue, betweene a Souldior of Barwicke and an English Chaplaine''), where it is dated May 10, 1566, and is addressed to Miles Coverdale

Myles Coverdale, first name also spelt Miles (1488 – 20 January 1569), was an English ecclesiastical reformer chiefly known as a Bible translator, preacher and, briefly, Bishop of Exeter (1551–1553). In 1535, Coverdale produced the first c ...

, William Turner, Whittingham, Sampson, Humphrey, Lever, Crowley, "and others that labour to roote out the weedes of Poperie." The date of the letter is not certain however, since it also appears under Gilby's name, with the date 1570 in a collection called ''A parte of a register...'', which was printed in Edinburgh by Robert Waldegrave in 1593 but was then suppressed.

Regarding Gilby's dialogue, the full title reads: ''A pleasaunt Dialogue, betweene a Souldior of Barwicke and an English Chaplaine; wherein are largely handled and laide open, such reasons as are brought in for maintenaunce of Popishe Traditions in our English Church, &c. Togither with a letter of the same Author, placed before this booke in way of a Preface. 1581.'' (This is the only extant version of this tract, barring a later 1642 edition, but it was probably printed earlier as well.) A second title inside the book reads: "A pleasaunt Dialogue, conteining a large discourse betweene a Souldier of Barwick and an English Chaplain, who of a late Souldier was made a Parson, and had gotten a pluralitie of Benefices, and yet had but one eye, and no learning: but he was priestly apparailed in al points, and stoutly maintained his Popish attire, by the authoritie of a booke lately written against London Ministers." In the dialogue, a soldier, Miles Monopodios, is set against Sir Bernarde Blynkarde, who is a corrupt pluralist minister, a former soldier and friend of Monopodios, and a wearer of vestments. In the process of correcting Blynkarde, Monopodios lists 100 vestiges of popery in the English church, including 24 unbiblical "offices".

Emergence of separatism and Presbyterianism

In the summer and autumn of 1566, conformists and nonconformists exchanged letters with continental reformers. The nonconformists looked to Geneva for support, but no real opportunity for change was coming, and the anti-vestments faction of the emerging Puritan element split into separatist and anti-separatist wings. Public debate turned into more and less furtive acts of direct disobedience, with the exception of a brief recurrence of the original issue in communications between Horne and Bullinger, and betweenJerome Zanchi

Girolamo Zanchi (Latin "Hieronymus Zanchius," thus Anglicized to "Jerome Zanchi/Zanchius"; February 2, 1516 – November 19, 1590) was an Italian Protestant Reformation clergyman and educator who influenced the development of Reformed theology ...

and the Queen, though the latter correspondence, held by Grindal, was never delivered.

Despite the appearance of a victory for Parker, Brett Usher

Brett Usher (10 December 1946– 13 June 2013) was an English actor, writer and ecclesiastical historian. Although he appeared frequently on stage and television, it was as a radio actor that he came to be best known. His many radio roles ranged ...

has argued that national uniformity was an impossible goal due to Parker's political and jurisdictional limitations. In Usher's view, the anti-vestments faction did not perceive a defeat in 1566, and it was not until the Presbyterian movements of the next two decades (which Parker's crackdown helped to provoke) that relations really changed between the state and high-ranking clergy who still sought further changes in the church.

After 1566, the most radical figures, the separatists, went underground to organise and lead illegal, secret congregations. One of the first official discoveries of a separatist congregation came on June 19, 1567, in Plumber's Hall in London. Similar discoveries followed, with the separatists usually claiming they were not separatists but the body of the true church. Anti-vestiarians like Humphrey and Sampson who rejected this movement were called "semi-papists" by the new radical vanguard.

Others opposed to vestments elected to try to change the shape of the church and its authority along presbyterian

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their na ...

lines in the early 1570s, and in this, they had continental support. Calvin's successor, Theodore Beza

Theodore Beza ( la, Theodorus Beza; french: Théodore de Bèze or ''de Besze''; June 24, 1519 – October 13, 1605) was a French Calvinist Protestant theologian, reformer and scholar who played an important role in the Protestant Reformation. ...

, had written in implicit support of the presbyterian system in 1566 in a letter to Grindal. This letter was acquired by pro-presbyterian Puritans and was published in 1572 with Thomas Wilcox and John Field John Field may refer to:

*John Field (American football) (1886–1979), American football player and coach

*John Field (brigadier) (1899–1974), Australian Army officer

*John Field (composer) (1782–1837), Irish composer

*John Field (dancer) (192 ...

's ''Admonition to Parliament'', the foundational manifesto and first public manifestation of English Presbyterianism. (The ensuing controversy is sometimes referred to as the Admonition Controversy

Admonition (or "being admonished") is the lightest punishment under Scots law. It occurs when an offender who has been found guilty or who has pleaded guilty, is not given a fine, but instead receives a lesser penalty in the form of a verbal war ...

.) Also included in the ''Admonition'' was another 1566 letter from Gualter to Bishop Parkhurst that was seen as lending support to the nonconformists. By some accounts, Gilby, Sampson, and Lever were indirectly involved in this publication, but the ensuing controversy centred on another public literary exchange between Archbishop John Whitgift and Thomas Cartwright, wherein Whitgift conceded the non-indifference of vestments but insisted on the authority of the church to require them. The issue became deadlocked and explicitly focused on the nature, authority, and legitimacy of the church polity. A primarily liturgical matter had developed into a wholly governmental one. The Separatist Puritans, led by Cartwright, persisted in their rejection of vestments, but the larger political issues had effectively eclipsed it.

In 1574–75, ''A Brieff discours off the troubles begonne at Franckford ... A.D. 1554'' was published. This was a pro-presbyterian historical narrative of the disputes among the Marian exiles in Frankfurt twenty years earlier "about the Booke off common prayer and Ceremonies ... in the which ... the gentle reader shall see the very originall and beginninge off all the contention that hathe byn and what was the cause off the same." This introductory advertisement on the title page is followed by Mark 4:22–23: "For there is nothinge hid that shall not be opened neither is there a secreat that it shall come to light yff anie man have eares to heare let him heare."

See also

* Idolatry **Idolatry in Christianity

Idolatry is the worship of a cult image or "idol" as though it were God. In Abrahamic religions (namely Judaism, Samaritanism, Christianity, the Baháʼí Faith, and Islam) idolatry connotes the worship of something or someone other than the ...

* Elizabethan Religious Settlement

The Elizabethan Religious Settlement is the name given to the religious and political arrangements made for England during the reign of Elizabeth I (1558–1603). Implemented between 1559 and 1563, the settlement is considered the end of the ...

* Ritualism

Ritualism, in the history of Christianity, refers to an emphasis on the rituals and liturgical ceremonies of the church. Specifically, the Christian ritual of Holy Communion.

In the Anglican church in the 19th century, the role of ritual became ...

References

Notes

Citations

Sources

Primary

''Digital facsimiles of many of the primary sources listed in this entry can be accessed througEarly English Books Online

(EEBO).'' * John Hooper, "Ex libro D. Hoperi, Reg. Consiliarijs ab ipso. exhibiti. 3. October. 1550. contra vsum vestium quibis in sacro Ministerio vitur Ecclesia Anglicana. quem librum sic orditur". Text printed in C. Hopf, "Bishop Hooper's 'Notes' to the King's Council", ''Journal of Theological Studies'' 44 (January–April, 1943): 194–99. * Nicholas Ridley, "Reply of Bishop Ridley to Bishop Hooper on the Vestment Controversy, 1550", in John Bradford, ''Writings'', ed. A. Townsend for the Parker Society (Cambridge, 1848, 1853): 2.373–95. * * John Stow, ''Historical Memoranda'' (

Camden Society

The Camden Society was a text publication society founded in London in 1838 to publish early historical and literary materials, both unpublished manuscripts and new editions of rare printed books. It was named after the 16th-century antiquary ...

, 1880; rpt. Royal Historical Society, 1965)

*

Secondary

* * * * * * * * * {{refendExternal links

* R. E. Pot,In Pursuit of Plainness: The Puritan Principle of Worship

English Reformation Elizabethan Puritanism Protestantism-related controversies