Valentine Thomas on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Valentine Thomas (died 1603) was an English servant or soldier whose confession in 1598 as a would-be assassin of

Crawforth was encouraged to implicate Thomas and assist in his capture by Edward Grey of

Crawforth was encouraged to implicate Thomas and assist in his capture by Edward Grey of

British Library: Showing Elizabeth I in a new light

/ref>

Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was Queen of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. Elizabeth was the last of the five House of Tudor monarchs and is sometimes referred to as the "Virgin Queen".

El ...

caused tension between England and Scotland. Thomas's confession implicated James VI of Scotland

James VI and I (James Charles Stuart; 19 June 1566 – 27 March 1625) was King of Scotland as James VI from 24 July 1567 and King of England and Ireland as James I from the union of the Scottish and English crowns on 24 March 1603 until hi ...

, who wrote several letters to Elizabeth to ensure his rights to English throne were unharmed.

Arrest and confession

Valentine Thomas was arrested in March 1598 atMorpeth

Morpeth may refer to:

*Morpeth, New South Wales, Australia

** Electoral district of Morpeth, a former electoral district of the Legislative Assembly in New South Wales

* Morpeth, Ontario, Canada

* Morpeth, Northumberland, England, UK

** Morpeth (UK ...

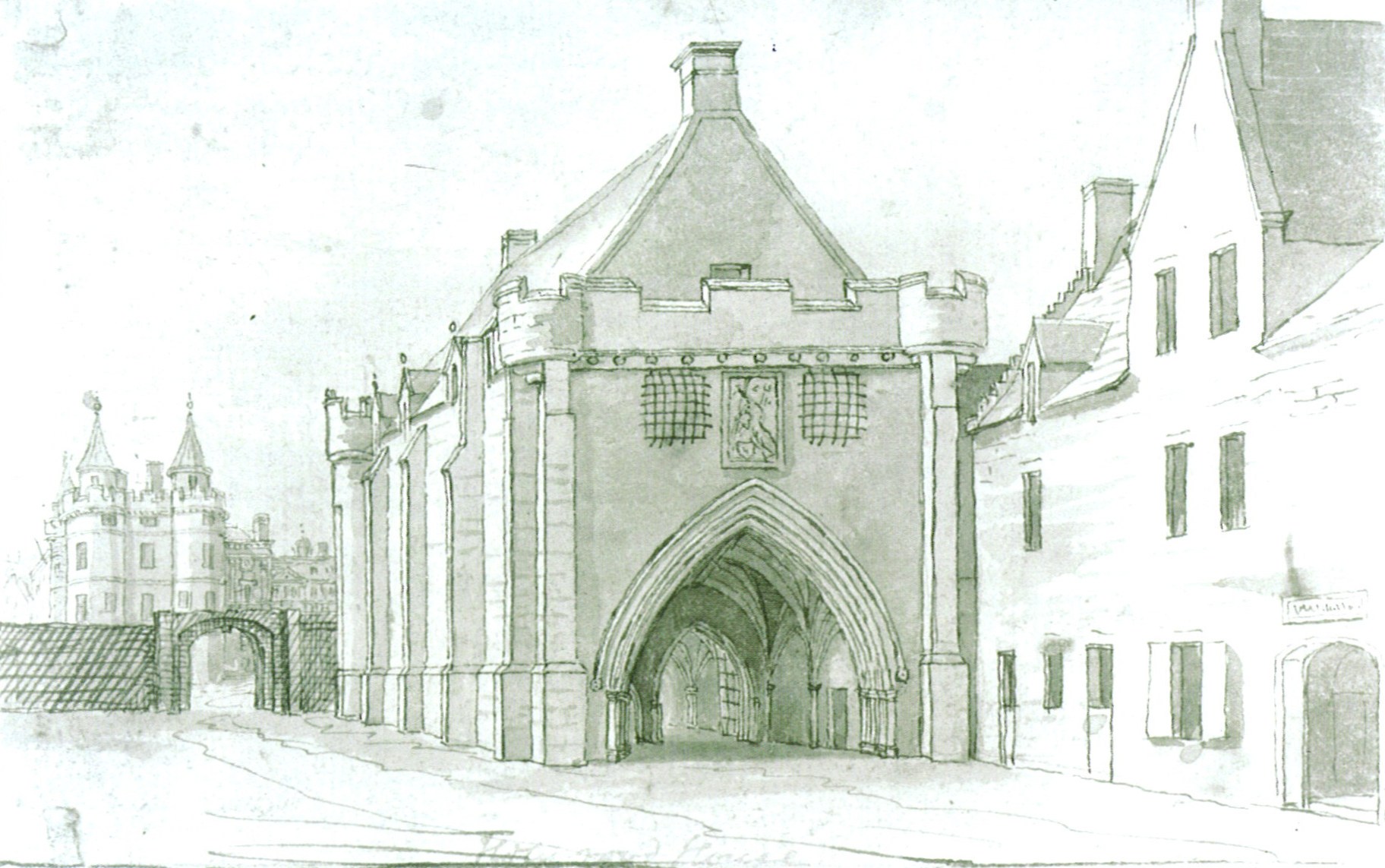

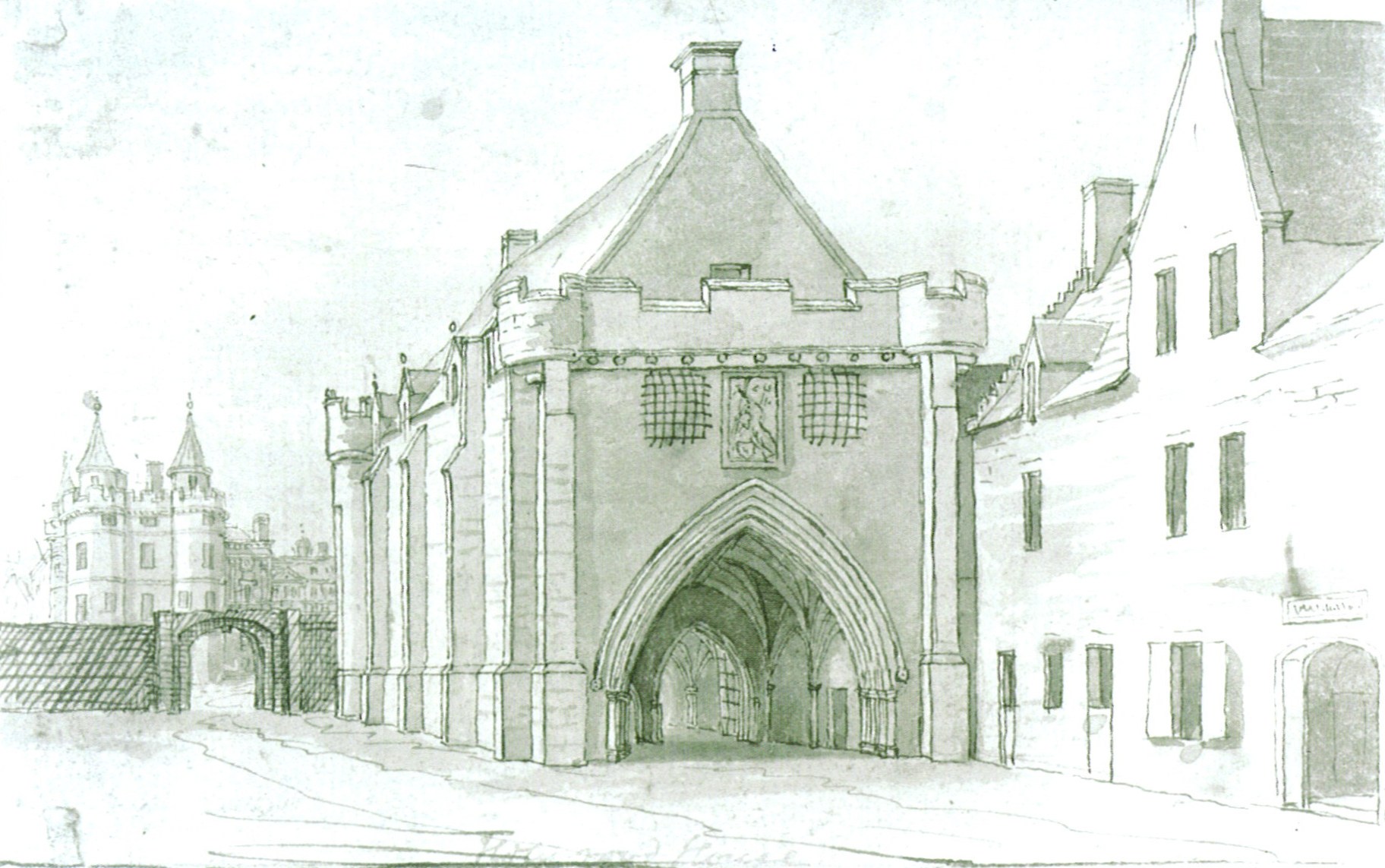

. A Scottish man captured in England, Robert Crawforth, gave testimony that prompted Thomas's arrest. He described meeting Thomas and the usher or door keeper John Stewart at Holyrood Palace

The Palace of Holyroodhouse ( or ), commonly referred to as Holyrood Palace or Holyroodhouse, is the official residence of the British monarch in Scotland. Located at the bottom of the Royal Mile in Edinburgh, at the opposite end to Edinbu ...

in 1597. John Stewart gave Thomas access to the palace and James VI. James had another servant of that name, John Stewart of Rosland, usually identified as a valet. Crawforth, who was transferred to the Marshalsea

The Marshalsea (1373–1842) was a notorious prison in Southwark, just south of the River Thames. Although it housed a variety of prisoners, including men accused of crimes at sea and political figures charged with sedition, it became known, in ...

prison in London, described one aspect of a conspiracy, that Valentine Thomas had offered to engage the support of English Catholics to put James on the English throne.

Crawforth was encouraged to implicate Thomas and assist in his capture by Edward Grey of

Crawforth was encouraged to implicate Thomas and assist in his capture by Edward Grey of Howick Howick may refer to:

Places

*Howick, KwaZulu-Natal, in South Africa

**Howick Falls

* Howick, Lancashire, a small hamlet (Howick Cross) and former civil parish in England

*Howick, New Zealand

**Howick Historical Village

**Howick (New Zealand electo ...

, constable of Morpeth Castle

Morpeth Castle is a Scheduled Ancient Monument and a Grade I listed building at Morpeth, Northumberland, in northeast England. It has been restored by the Landmark Trust and is now available as a holiday rental home.

History

The original mott ...

and depute Border Warden. Thomas was arrested and taken to the Marshalsea and then questioned in the Tower of London

The Tower of London, officially His Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress of the Tower of London, is a historic castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, which is separa ...

. He was to stand trial for a plot rebel with recusants and Pickering in the north of England. After a time, in his conversations with other prisoners and during further questioning he spoke of meetings with James VI and a plot to kill Elizabeth I.

Thomas said he had used ''alias'' surnames of Anderson and Alderson. Thomas claimed to have had access to the Scottish royal court via John Stewart, an usher or keeper of the king's chamber door. He said that he had heard James VI wish that William Cecil, the English Lord Treasurer was dead. Thomas said he offered to kill Cecil, and after further discussion, James suggested he should stab Queen Elizabeth while delivering a petition.

It was said that Thomas's confessions also described a meeting at Linlithgow Palace

The ruins of Linlithgow Palace are located in the town of Linlithgow, West Lothian, Scotland, west of Edinburgh. The palace was one of the principal residences of the monarchs of Scotland in the 15th and 16th centuries. Although mai ...

. In his description of the conversation, Thomas said he told James that he was to attend the wedding of a kinsman in Glasgow, and James responded mentioning "Sorley Boy", meaning James MacDonald, a brother of Angus MacDonald of Dunyvaig. Thomas mentioned the Campbell laird of Ardkinglas was present at Holyroodhouse or Linlithgow. James MacDonald was understood to be a kinsman of Sorley Boy MacDonnell, who had been regarded by Elizabeth I as rebel in Ireland.

English authorities were keen to investigate those who crossed the border without permission. In 1599, English agents from Berwick-upon-Tweed

Berwick-upon-Tweed (), sometimes known as Berwick-on-Tweed or simply Berwick, is a town and civil parish in Northumberland, England, south of the Anglo-Scottish border, and the northernmost town in England. The 2011 United Kingdom census recor ...

captured an English visitor at the Scottish court, Edmund Ashfield

Edmund Ashfield ( fl. 1660–1690) was an English portrait painter and miniaturist, who worked in both oils and pastels.

Life

Ashfield came from a Buckinghamshire family and was a pupil of John Michael Wright (1617–94). He worked both in oi ...

, and took him back to England. Ashfield, like Thomas, was interested in James's succession and the potential support of Catholic recusants for his rule in England. Elizabeth I wrote that Ashfield was one of her subjects motivated by their "own humour and busy natures". Ashfield was of gentry status, liitle is known of Thomas's background.

Diplomacy

Although it is unlikely that James VI had instructed Valentine Thomas to assassinate Elizabeth and Cecil, and the allegations were not widely believed, the situation embarrassed James VI. He hoped to succeed Elizabeth (he gained her throne in 1603). Elizabeth had passed laws against plotters in 1585, with an Act of Safety which might work against the Scottish king's ambition. An English diplomat in Edinburgh, George Nicolson, discovered that James VI had heard of Thomas's confession in April and believed Elizabeth I kept it secret in order to use it against him in the future. Nicolson wrote that James was "much troubled and grieved, albeit in secret sort". One of James'scouncillors

A councillor is an elected representative for a local government council in some countries.

Canada

Due to the control that the provinces have over their municipal governments, terms that councillors serve vary from province to province. Unl ...

, Edward Bruce

Edward Bruce, Earl of Carrick ( Norman French: ; mga, Edubard a Briuis; Modern Scottish Gaelic: gd, Eideard or ; – 14 October 1318), was a younger brother of Robert the Bruce, King of Scots. He supported his brother in the 1306–1314 st ...

, advised that Elizabeth would not believe he was at fault. Other courtiers suggested that Bruce made such suggestions because Elizabeth had given him a rich gold chain as a reward.

Nicolson worried that the ambassadors Peter Young Peter or Pete Young may refer to:

Sports

* Peter Dalton Young (1927–2002), English rugby union player

* Peter Young (cricketer, born 1961), Australian cricketer

* Pete Young (born 1968), American baseball player

* Peter Young (rugby league) (fl. ...

and David Cunningham, Bishop of Aberdeen, sent by James VI to Denmark and to German princes in the wake of the visit of Anne of Denmark

Anne of Denmark (; 12 December 1574 – 2 March 1619) was the wife of King James VI and I; as such, she was Queen of Scotland

The monarchy of the United Kingdom, commonly referred to as the British monarchy, is the constitutional fo ...

's brother the Duke of Holstein

The Duchy of Holstein (german: Herzogtum Holstein, da, Hertugdømmet Holsten) was the northernmost state of the Holy Roman Empire, located in the present German state of Schleswig-Holstein. It originated when King Christian I of Denmark had his ...

to request their future support for his succession to the throne of England would now spread news of "griefs and slanders" suffered by James because of the Valentine Thomas affair.

It was reported in June 1598 that James VI had been told that William Cecil thought the issue was of low importance, that Thomas was "but a knave" and could be released. Edward Bruce told George Nicolson that James was still displeased by the affair, focussing on the failure of the English ambassador William Bowes to keep him informed. James thought the business should have been made open, "kindly discovered", to Bowes and himself.

James prepared to send diplomats including David Foulis to London to try and resolve the situation, and ensure that the king's honour was not dented. On 1 July 1598, Elizabeth I wrote to James that she would "make the deviser have his desert" more for impuning James than his other misdemeanours. Thomas was to be found guilty or indicted of plotting with "Pickering of the North" to rebel with Catholic recusants.

James VI was informed that Valentine Thomas had written a poem with charcoal on a chimney breast at the Tower of London:I shot at a fair white: And in loosing of my arrowAnother prisoner, Thomas Madryn, saw the verses and wrote to the

My elbow was wrested. But I melt for grief

To lose such a game: having so fair a mark.

But if I had escaped that wrest, God knoweth without all peradventure

I had won that game: To the great comfort of England

And profit of myself.

Earl of Essex

Earl of Essex is a title in the Peerage of England which was first created in the 12th century by King Stephen of England. The title has been recreated eight times from its original inception, beginning with a new first Earl upon each new cre ...

that Thomas was a "very poor poet". James VI read the verses with George Nicolson at Stirling Castle

Stirling Castle, located in Stirling, is one of the largest and most important castles in Scotland, both historically and architecturally. The castle sits atop Castle Hill, an intrusive crag, which forms part of the Stirling Sill geological ...

on 7 July. They were puzzled, and James "curiously read them saying and studying what meant he by them".

James VI wrote to Elizabeth on 30 July that the "foggy mists of groundless calumnies" were clearing. He hoped that Thomas's execution could be delayed until he was fully satisfied that he was exonerated in the "minds of all men". Nicolson told him that Thomas was still alive in August.

In September, David Foulis discussed the affair the Privy Council of England

The Privy Council of England, also known as His (or Her) Majesty's Most Honourable Privy Council (), was a body of advisers to the sovereign of the Kingdom of England. Its members were often senior members of the House of Lords and the House of ...

at Greenwich Palace

Greenwich ( , ,) is a town in south-east London, England, within the ceremonial county of Greater London. It is situated east-southeast of Charing Cross.

Greenwich is notable for its maritime history and for giving its name to the Greenwich ...

with reference to the " Act of Association". The Council insisted Elizabeth I had not tried to slander James using Thomas's confession, and they believed James had never heard of any such plot. Valentine Thomas had been condemned on other charges. There was no need to make any public declaration. Foulis requested a copy of the legal proceedings against Thomas for James VI.

A letter to Foulis from James Elphinstone mentions proposals to send Thomas as a prisoner to Scotland, where he could be interrogated with torture under English supervision and returned to England for execution. Foulis continued his work in London and sent reports back to Scotland by the usual land route, some countersigned by Sir Robert Cecil

Robert Cecil, 1st Earl of Salisbury, (1 June 156324 May 1612), was an English statesman noted for his direction of the government during the Union of the Crowns, as Tudor England gave way to Stuart rule (1603). Lord Salisbury served as the ...

, and others were sent more securely by sea. He wanted a signed statement, to the effect that Thomas was no more than a vagabond, guilty of various crimes, who had been to Scotland and hoped to avoid execution by making allegations about James VI.

A statement of the key points of the confession dated 20 December 1598 was witnessed by John Peyton, Edward Coke

Edward is an English given name. It is derived from the Anglo-Saxon name ''Ēadweard'', composed of the elements '' ēad'' "wealth, fortune; prosperous" and '' weard'' "guardian, protector”.

History

The name Edward was very popular in Anglo-Sa ...

, Thomas Fleming, Francis Bacon

Francis Bacon, 1st Viscount St Alban (; 22 January 1561 – 9 April 1626), also known as Lord Verulam, was an English philosopher and statesman who served as Attorney General and Lord Chancellor of England. Bacon led the advancement of both ...

, and William Waad

Sir William Wade (or Waad, or Wadd; 154621 October 1623) was an English statesman and diplomat, and Lieutenant of the Tower of London.

Early life and education

Wade was the eldest son of Armagil Wade, the traveller, who sailed with a party of ...

. On the same day, Elizabeth signed a declaration that she did not believe there had been a Scottish plot against her and she would continue her good relations with James.

Elizabeth wrote to Nicolson that she considered that James's propositions made by his ambassadors to Christian IV of Denmark

Christian IV (12 April 1577 – 28 February 1648) was King of Denmark and Norway and Duke of Holstein and Schleswig from 1588 until his death in 1648. His reign of 59 years, 330 days is the longest of Danish monarchs and Scandinavian monar ...

and the German princes (concerning the English succession) were composed when he was "transported at that time with sudden and unjust rumours".

The affair seems nearly to have been resolved, Foulis returned to Scotland with £3,000 subsidy money, but James persisted in his view that Thomas ought to be brought to Scotland and tortured. James sent Elizabeth the "true portrait of my thoughts". Another diplomat, James Sempill

Sir James Sempill (1566–1626) was a Scottish courtier and diplomat.

Early life

James Sempill was the eldest son of John Sempill of Beltrees, and Mary Livingston, one of the "Four Marys", companions of Mary, Queen of Scots.

Sempill was brought ...

, was sent to London. In April, Elizabeth made a statement on the affair for William Bowes to deliver to James. Bowes assured James that Thomas was still alive, indicted, but not convicted.

Execution

Valentine Thomas remained a prisoner. He washanged, drawn and quartered

To be hanged, drawn and quartered became a statutory penalty for men convicted of high treason in the Kingdom of England from 1352 under Edward III of England, King Edward III (1327–1377), although similar rituals are recorded during the rei ...

at Saint Thomas Watering on 7 June 1603 after a trial for treason against Elizabeth and her council. James was crowned in London in July.

Researchers at the British Library

The British Library is the national library of the United Kingdom and is one of the largest libraries in the world. It is estimated to contain between 170 and 200 million items from many countries. As a legal deposit library, the British ...

in 2023 discovered that amongst other revisions the chronicle writer William Camden had abbreviated his account of the Valentine Thomas affair for the publication of his ''Annals of the Reign of Elizabeth I''. The reworking was intended to avoid the king's potential displeasure./ref>

References

{{DEFAULTSORT:Thomas, Valentine 1603 deaths England–Scotland relations 16th-century English people Assassins Prisoners in the Tower of London Inmates of the Marshalsea Succession to Elizabeth I People executed by Stuart England by hanging, drawing and quartering