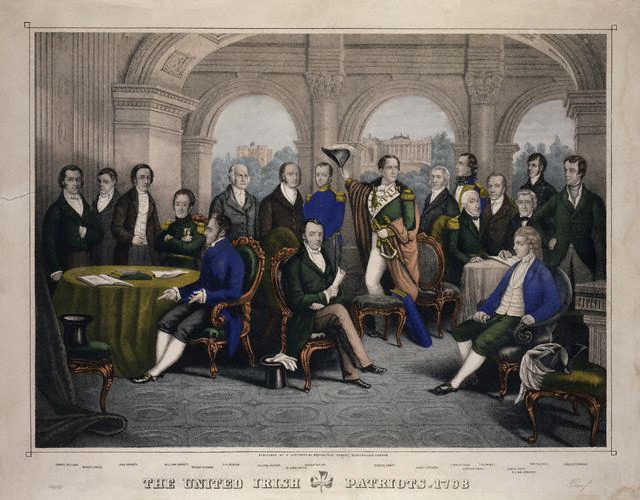

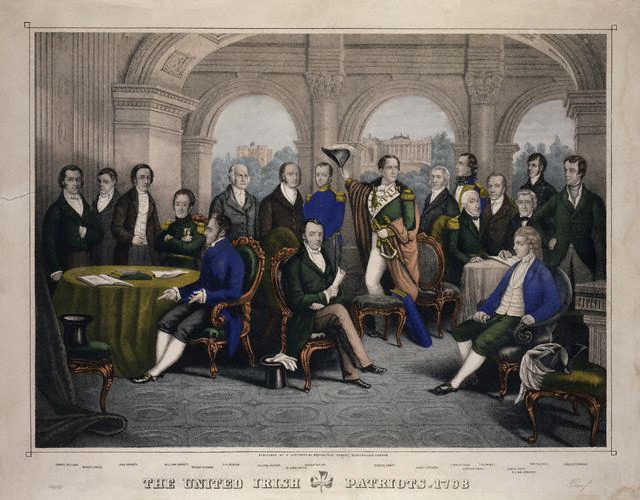

The Society of United Irishmen was a sworn association in the

Kingdom of Ireland formed in the wake of the

French Revolution to secure "an equal representation of all the people" in a national government. Despairing of constitutional reform, in 1798 the United Irishmen instigated

a republican insurrection in defiance of British

Crown forces

The Crown is the state in all its aspects within the jurisprudence of the Commonwealth realms and their subdivisions (such as the Crown Dependencies, overseas territories, provinces, or states). Legally ill-defined, the term has different ...

and of Irish

sectarian division. Their suppression was a prelude to the abolition of the

Protestant Ascendancy Parliament in Dublin and to Ireland's incorporation in a

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and ...

with

Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It ...

. An attempt to revive the movement and renew the insurrection following the

Acts of Union was

defeated in 1803.

Espousing principles they believed had been vindicated by

American independence and by the

French Declaration of the Rights of Man, the Presbyterian merchants who formed the first United society in Belfast in 1791 vowed to make common cause with their Catholic-majority fellow countrymen. Their "cordial union" would upend Ireland's

Protestant (Anglican) Ascendancy and hold her government accountable to a representative Parliament.

As the society replicated in Belfast,

Dublin

Dublin (; , or ) is the capital and largest city of Ireland. On a bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the province of Leinster, bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, a part of the Wicklow Mountains range. At the 2016 ...

, and across rural Ireland, its

membership test was administered to workingmen (and in cases women) who maintained their own democratic clubs, and to tenant farmers organised against the Protestant

gentry

Gentry (from Old French ''genterie'', from ''gentil'', "high-born, noble") are "well-born, genteel and well-bred people" of high social class, especially in the past.

Word similar to gentle imple and decentfamilies

''Gentry'', in its widest c ...

in secret fraternities. The goals of the movement were restated in uncompromising terms:

Catholic emancipation and reform became the call for

universal manhood suffrage

Universal manhood suffrage is a form of voting rights in which all adult male citizens within a political system are allowed to vote, regardless of income, property, religion, race, or any other qualification. It is sometimes summarized by the slo ...

(every man a citizen) and for an Irish republic. Preparations were laid for an insurrection to be assisted by the French and by new United societies in Scotland and England. Plans were disrupted by government infiltration and by martial-law arrests and seizures, so that when it came in the summer of 1798 the call to arms resulted a series of uncoordinated local risings.

The British government seized on the rebellion to argue the greater security of a union with

Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It ...

. In 1800 the

Irish legislature was abolished in favour of a

United Kingdom parliament at

Westminster

Westminster is an area of Central London, part of the wider City of Westminster.

The area, which extends from the River Thames to Oxford Street, has many visitor attractions and historic landmarks, including the Palace of Westminster, B ...

. The attempt to restore the movement by organising on strictly military lines failed to elicit a response in what had been the United heartlands in the north, and misfired in 1803 with

Robert Emmet's rising in Dublin.

Since the rebellion's centenary in 1898,

Irish nationalists

Irish nationalism is a nationalist political movement which, in its broadest sense, asserts that the people of Ireland should govern Ireland as a sovereign state. Since the mid-19th century, Irish nationalism has largely taken the form of cu ...

and

Ulster unionists

The Ulster Unionist Party (UUP) is a unionist political party in Northern Ireland. The party was founded in 1905, emerging from the Irish Unionist Alliance in Ulster. Under Edward Carson, it led unionist opposition to the Irish Home Rule movem ...

have contested its legacy.

Background

Dissenters: "Americans in their hearts"

The Society was formed at a gathering in a

Belfast tavern in October 1791. With the exception of

Thomas Russell, a former

India-service army-officer originally from

Cork

Cork or CORK may refer to:

Materials

* Cork (material), an impermeable buoyant plant product

** Cork (plug), a cylindrical or conical object used to seal a container

***Wine cork

Places Ireland

* Cork (city)

** Metropolitan Cork, also known as G ...

, and

Theobald Wolfe Tone, a Dublin

barrister, the participants who resolved to reform the government of Ireland on "principles of civil, political and religious liberty" were

Presbyterians. As Dissenters from the established

Anglican (

Church of Ireland

The Church of Ireland ( ga, Eaglais na hÉireann, ; sco, label= Ulster-Scots, Kirk o Airlann, ) is a Christian church in Ireland and an autonomous province of the Anglican Communion. It is organised on an all-Ireland basis and is the sec ...

) communion they were conscious of having shared, in part, the

civil and political disabilities of the Kingdom's dispossessed

Roman Catholic majority.

Although open to them as Protestants, the

Parliament in Dublin offered little opportunity for representation or redress. Two-thirds of the

Irish House of Commons represented

boroughs in the pockets of

Lords in the Upper House. Belfast's two

MPs were elected by the thirteen members of the

corporation

A corporation is an organization—usually a group of people or a company—authorized by the state to act as a single entity (a legal entity recognized by private and public law "born out of statute"; a legal person in legal context) and ...

, all nominees of the Chichesters,

Marquesses of Donegall. Swayed by Crown patronage, parliament in any case exercised little hold upon the executive, the

Dublin Castle administration which through the office of the

Lord Lieutenant continued to be appointed by the King's ministers in London. Ireland, the Belfast conferees observed, had "no national government". She was ruled "by Englishmen, and the servants of Englishmen"

Faced with the

tithes,

rack rents and

sacramental tests of this

Ascendancy, and with the supremacy of the English interest, Presbyterians had been voting by leaving Ireland in ever greater numbers. From 1710 to 1775 over 200,000 sailed for the

North American colonies. When the

American Revolutionary War commenced in 1775, there were few Presbyterian households that did not have relatives in America, many of whom would take up arms against

the Crown

The Crown is the state in all its aspects within the jurisprudence of the Commonwealth realms and their subdivisions (such as the Crown Dependencies, overseas territories, provinces, or states). Legally ill-defined, the term has differ ...

.

Most of the Society's founding members and leadership were members of Belfast's first three Presbyterian churches, all in Rosemary Street. The obstetrician

William Drennan, who in Dublin composed the

United Irishmen's first test or oath, was the son of the minister of the First Church;

Samuel Neilson, owner of the largest woollen warehouse in Belfast, was in the Second Church;

Henry Joy McCracken, born into the town's leading fortunes in shipping and linen-manufacture, was a Third Church member. Despite theological differences (the First and Second Churches did not subscribe to the

Westminster Confession of Faith, and the Third sustained an

Old Light evangelical tradition), their elected, Scottish-educated, ministers inclined in their teaching toward conscience rather than doctrine. In itself, this did not imply political radicalism. But it could, and (consistent with the teachings at

Glasgow

Glasgow ( ; sco, Glesca or ; gd, Glaschu ) is the most populous city in Scotland and the fourth-most populous city in the United Kingdom, as well as being the 27th largest city by population in Europe. In 2020, it had an estimated popu ...

of the Ulster divine

Francis Hutcheson) did, lead to acknowledgement from the pulpit of a right of collective resistance to oppressive government. In Rosemary Street's Third Church, Sinclare Kelburn preached in the uniform of an

Irish Volunteer, with his musket propped against the pulpit door.

Assessing security on the eve of the

American War, the

British Viceroy,

Lord Harcourt, described the Presbyterians of

Ulster as Americans "in their hearts".

The Volunteers and Parliamentary Patriots

For the original members of the Society, the

Irish Volunteers were a further source of prior association. Formed to secure

the Kingdom as the British garrison was drawn down for American service, Volunteer companies were often little more than local landlords and their retainers armed and drilled. But in Dublin, and above all in

Ulster (where they convened provincial conventions) they mobilised a much wider section of Protestant society.

In April 1782, with Volunteer cavalry, infantry, and artillery posted on all approaches to the Parliament in Dublin,

Henry Grattan, leader of the Patriot opposition, had a Declaration of Irish Rights carried by acclaim in the Commons. London conceded,

surrendering its powers to legislate for Ireland. In 1783 Volunteers converged again upon Dublin, this time to support a bill presented by Grattan's patriot rival,

Henry Flood, to abolish the proprietary boroughs and to extend the vote to a broader class of Protestant property holders. But the Volunteer moment had passed. Having accepted defeat in America, Britain could again spare troops for Ireland, and the limits of the Ascendancy's patriotism had been reached. Parliament refused to be intimidated.

With the news in 1789 of revolutionary events in France enthusiasm for constitutional reform revived. In

Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen

The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen (french: Déclaration des droits de l'homme et du citoyen de 1789, links=no), set by France's National Constituent Assembly in 1789, is a human civil rights document from the French Revol ...

France, the greatest of the Catholic powers, was seen to be undergoing its own

Glorious Revolution. In his ''

Reflections on the Revolution in France'' (1790),

Edmund Burke

Edmund Burke (; 12 January NS.html"_;"title="New_Style.html"_;"title="/nowiki>New_Style">NS">New_Style.html"_;"title="/nowiki>New_Style">NS/nowiki>_1729_–_9_July_1797)_was_an_NS.html"_;"title="New_Style.html"_;"title="/nowiki>New_Style">N ...

had sought to discredit any analogy with 1688 in England. But on reaching the Belfast in October 1791, Tone found that

Thomas Paine

Thomas Paine (born Thomas Pain; – In the contemporary record as noted by Conway, Paine's birth date is given as January 29, 1736–37. Common practice was to use a dash or a slash to separate the old-style year from the new-style year. In th ...

's response to Burke, the ''

Rights of Man'' (of which the new society was to distribute thousands of copies for as little as a penny apiece), had won the argument.

Three months before, on 14 July, the second anniversary of the

Fall of the Bastille

The Storming of the Bastille (french: Prise de la Bastille ) occurred in Paris, France, on 14 July 1789, when revolutionary insurgents stormed and seized control of the medieval armoury, fortress, and political prison known as the Bastille. At ...

was celebrated with a triumphal Volunteer procession through Belfast and a solemn Declaration to the Great and Gallant people of France: "As Irishmen, We too have a country, and we hold it very dear—so dear... that we wish all Civil and Religious Intolerance annihilated in this land." Bastille Day the following year was greeted with similar scenes and an address to the

French National Assembly hailing the soldiers of the new republic as "the advance guard of the world".

Belfast debates

First resolutions

It was in the midst of this enthusiasm for events in France that

William Drennan proposed to his friends "a benevolent conspiracy—a plot for the people", the "Rights of Man and

mploying the phrase coined by Hutchesonthe Greatest Happiness of the Greater Number its end—its general end Real Independence to Ireland, and Republicanism its particular purpose."

When Drennan's friends gathered in Belfast, they resolved:

--that the weight of English influence in the government of this country is so great as to require a cordial union among all the people of Ireland; nd

--that the sole constitutional mode by which this influence can be opposed, is by complete and radical reform of the representation of the people in parliament.

The "conspiracy", which at Tone's suggestion called itself the Society of the United Irishmen, had moved beyond Flood's Protestant patriotism. English influence, exercised through the

Dublin Castle Executive, would be checked constitutionally by a parliament in which "all the people" would have "an equal representation." Unclear, however, was whether the emancipation of Catholics was to be unqualified and immediate. The previous evening, witnessing a debate over the Catholic Question between the town's leading reformers (members of the Northern

Whig Club) Tone had found himself "teased" by people agreeing in principle to Catholic emancipation, but then proposing that it be delayed or granted only in stages.

The Catholic Question

Thomas Russell had invited Tone to the Belfast gathering in October 1791 as the author of ''An Argument on behalf of the Catholics of Ireland''. In honour of the reformers in Belfast, who arranged for the publication of 10,000 copies, this had been signed A Northern Whig. Being of French

Huguenot descent, Tone may have had an instinctive empathy for the religiously persecuted, but he was "suspicious of the Catholics priests" and hostile to what he saw as "Papal tyranny". (In 1798 Tone applauded

Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader wh ...

's deposition and imprisonment of

Pope Pius VI).

For Tone the argument on behalf of the Catholics was political. The "imaginary Revolution of 1782" had failed to secure a representative and national government for Ireland because Protestants had refused to make common cause with Catholics. In Belfast the objections to doing so were rehearsed for him again by the Reverend

William Bruce. Bruce spoke of the danger of "throwing power into hands" of Catholics who were "incapable of enjoying and extending liberty," and whose first interest would be to reclaim their forfeited lands.

In his ''Argument'' Tone insisted that, as a matter of justice, men cannot be denied rights because an incapacity, whether ignorance or intemperance, for which the laws under which they are made to live are themselves responsible. History, in any case, was reassuring: when they had the opportunity in the

Parliament summoned by

James II in 1689, and clearer title to what had been forfeit not ninety but forty years before (in the

Cromwellian Settlement

The Act for the Setling of Ireland imposed penalties including death and land confiscation against Irish civilians and combatants after the Irish Rebellion of 1641 and subsequent unrest. British historian John Morrill wrote that the Act and a ...

), Catholics did not insist upon a wholesale return of their lost estates. As to the existing Irish Parliament "where no Catholic can by law appear", it was the clearest proof that "Protestantism is no guard against corruption".

Tone cited the examples of the

American Congress

The United States Congress is the legislature of the federal government of the United States. It is bicameral, composed of a lower body, the House of Representatives, and an upper body, the Senate. It meets in the U.S. Capitol in Washingt ...

and

French National Assembly

The National Assembly (french: link=no, italics=set, Assemblée nationale; ) is the lower house of the bicameral French Parliament under the Fifth Republic, the upper house being the Senate (). The National Assembly's legislators are kn ...

where "Catholic and Protestant sit equally" and of the Polish

Constitution of May 1791 (also celebrated in Belfast) with its promise of amity between Catholic, Protestant and Jew. If Irish Protestants remained "illiberal" and "blind" to these precedents, Ireland would continue to be governed in the exclusive interests of England and of the landed Ascendancy.

The Belfast Catholic Society sought to underscore Tone's argument. Meeting in April 1792 they declared their "highest ambition" was "to participate in the constitution" of the kingdom, and disclaimed even "the most distant thought of

..unsettling the landed property thereof".

On Bastille Day 1792 in Belfast, the United Irishmen had occasion to make their position clear. In a public debate on An Address to the People of Ireland, William Bruce and others proposed hedging the commitment to an equality of "all sects and denominations of Irishmen". They had rather anticipate "the gradual emancipation of our Roman Catholic brethren" staggered in line with Protestant concerns for security and with improving Catholic education. Samuel Neilson "expressed his astonishment at hearing... any part of the address called a Catholic question." The only question was "whether Irishmen should be free."

William Steel Dickson

William Steel Dickson (1744–1824) was an Irish Presbyterian minister and member of the Society of the United Irishmen, committed to the cause of Catholic Emancipation, democratic reform, and national independence. He was arrested on the eve ...

, with "keen irony", wondered whether Catholics were to ascend the "ladder" to liberty "by intermarrying with the wise and capable Protestants, and particularly with us Presbyterians,

o thatthey may amend the breed, and produce a race of beings who will inherit the capacity from us?"

The amendment was defeated, but the debate reflected a growing division. The call for Catholic emancipation might find support in Belfast and surrounding Protestant-majority districts. West of the

River Bann

The River Bann (from ga, An Bhanna, meaning "the goddess"; Ulster-Scots: ''Bann Wattèr'') is one of the longest rivers in Northern Ireland, its length, Upper and Lower Bann combined, being 129 km (80 mi). However, the total lengt ...

, and across the south and west of Ireland where Protestants were a distinct minority, veterans of the Volunteer movement were not as easily persuaded.

[Elliott, Marianne (2003), "Religious polarization and sectarianism in the Ulster rebellion", in Thomas Bartlett et al. (eds.)]

''1798: A Bicentenary Perspective'', Dublin

Four Courts Press, , pp. 279-297. The Armagh Volunteers, who had called a Volunteer Convention in 1779, boycotted a third in 1793. Under Ascendancy patronage they were already moving along with the

Peep o' Day Boys

The Peep o' Day Boys was an agrarian Protestant association in 18th-century Ireland. Originally noted as being an agrarian society around 1779–80, from 1785 it became the Protestant component of the sectarian conflict that emerged in County Ar ...

, battling Catholic

Defenders

Defender(s) or The Defender(s) may refer to:

*Defense (military)

*Defense (sports)

**Defender (association football)

Arts and entertainment Film and television

* ''The Defender'' (1989 film), a Canadian documentary

* ''The Defender'' (1994 f ...

in rural districts for tenancies and employment, toward the formation in 1795 of the loyalist

Orange Order

The Loyal Orange Institution, commonly known as the Orange Order, is an international Protestant fraternal order based in Northern Ireland and primarily associated with Ulster Protestants, particularly those of Ulster Scots people, Ulster Sco ...

.

Equal representation

In 1793, the Government itself breached the principle of an exclusively Protestant Constitution. Dublin Castle put its weight behind Grattan in the passage of a

Catholic Relief Act

The Roman Catholic Relief Bills were a series of measures introduced over time in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries before the Parliaments of Great Britain and the United Kingdom to remove the restrictions and prohibitions impos ...

. Catholics were admitted to the franchise (but not yet to Parliament itself) on the same terms as Protestants. This courted Catholic opinion, but it also put Protestant reformers on notice. Any further liberalising of the franchise, whether by expunging the pocket boroughs or by lowering of the property threshold, would advance the prospect of a Catholic majority. Outside of Ulster and Dublin City, in 1793 the only popular resolution in favour of "a reform" of the Irish Commons to include "persons of all religious persuasion" was from freeholders gathered in Wexford town.

Beyond the inclusion of Catholics and a re-distribution of seats, Tone and Russell protested that it was unclear what members were pledging themselves to in Drennan's original

"test": "an impartial and adequate representation of the Irish nation in parliament" was too vague and compromising. But within two years, with Drennan they and other leaders were agreed on reforms that went beyond the dispensation they had celebrated in the

French Constitution of 1791

The French Constitution of 1791 (french: Constitution française du 3 septembre 1791) was the first written constitution in France, created after the collapse of the absolute monarchy of the . One of the basic precepts of the French Revolution ...

. In November 1793, they called for equal electoral districts, annual parliaments, paid representatives and ''universal manhood suffrage''.

In the exercise of political rights, property, like religion, was to be excuded from consideration.

The new democratic programme was consistent with the transformation of the society into a broad popular movement.

Thomas Addis Emmet

Thomas Addis Emmet (24 April 176414 November 1827) was an Irish and American lawyer and politician. He was a senior member of the revolutionary Irish republican group United Irishmen in the 1790s. He served as Attorney General of New York from ...

recorded an influx of "mechanics

rtisans,_journeymen_and_their_apprentices.html" ;"title="journeymen.html" ;"title="rtisans, journeymen">rtisans, journeymen and their apprentices">journeymen.html" ;"title="rtisans, journeymen">rtisans, journeymen and their apprentices petty shopkeepers and farmers". In Belfast, Derry, other towns in the North, and in Dublin, some of these had been maintaining their own Jacobin Clubs.

Writing to her brother, William Drennan, in 1795

Martha McTier describes the Irish Jacobins as an established democratic party in Belfast, composed of "persons and rank long kept down" and

William_Tennant.html" ;"title="William Tennant (United Irishmen)">William Tennant">William Tennant (United Irishmen)">William Tennant chaired by a "radical mechanick" (sic).

When April 1795 the new

Lord Lieutenant,

Earl Fitzwilliam

Earl Fitzwilliam (or FitzWilliam) was a title in both the Peerage of Ireland and the Peerage of Great Britain held by the head of the Fitzwilliam family (later Wentworth-Fitzwilliam).

History

The Fitzwilliams acquired extensive holdings in t ...

, after publicly urging Catholic admission to parliament was recalled and replaced by

Ascendancy hard-liner,

Earl Camden, these low-ranked clubists entered United Irish societies in still greater numbers. With the Rev. Kelburn (much admired by Tone as a fervent democrat), they doubted that there "was any such thing" as Ireland's "much boasted constitution." In correspondence with clubs in England and Scotland, some proposed that delegates from all three kingdoms convene to draft a "true constitution". In May, delegates in Belfast representing 72 societies in Down and Antrim rewrote Drennan's test to pledge members to "an equal, full and adequate representation of all the people of Ireland", and to drop the reference to the

Irish Parliament (with its

Lords

Lords may refer to:

* The plural of Lord

Places

*Lords Creek, a stream in New Hanover County, North Carolina

*Lord's, English Cricket Ground and home of Marylebone Cricket Club and Middlesex County Cricket Club

People

*Traci Lords (born 19 ...

and

Commons

The commons is the cultural and natural resources accessible to all members of a society, including natural materials such as air, water, and a habitable Earth. These resources are held in common even when owned privately or publicly. Commons c ...

).

This Painite radicalism had been preceded by an upsurge in trades union activity. In 1792 the

''Northern Star'' reported a "bold and daring spirit of combination" (long in evidence in Dublin) appearing in Belfast and surrounding districts. Breaking out first among cotton weavers, it then communicated to the bricklayers, carpenters and other trades. In the face of "demands made in a tumultuous and illegal manner", Samuel Neilson (who had pledged his woollen business to the paper) proposed that the Volunteers assist the authorities in enforcing the laws against combination.

James (Jemmy) Hope, a self educated weaver, who joined the Society in 1796, nonetheless was to account Neilson, along with Russell (who in the ''Star'' positively urged unions for labourers and

cottiers), McCracken, and

Emmet, the only United Irish leaders "perfectly" understood the real causes of social disorder and conflict: "the conditions of the labouring class".

A Dublin Society handbill of March 1794 made an appeal to "the poorer classes of the community" explicit and direct:

Are you overloaded with burdens you are but little able to bear? Do you feel many grievances, which it would be too tedious, and might be ''unsafe'', to mention? Believe us, they can be redressed by such by such reform as will give you your just proportion of influence in the legislature, AND BY SUCH A MEASURE ONLY.

As a body, however, United Irishmen did not propose the forms that such redress might take in a democratic national assembly. Operating on the principle that they should "attend those things in which we all agree,

ndto exclude those in which we differ", the Society did not itself tie the prospect of popular suffrage to an economic or social programme.

Given the central role it was to play in the eventual development of Irish democracy, the most startling omission was the absence, beyond the disclaimer of wholesale Catholic restitution, of any scheme or principle of

land reform

Land reform is a form of agrarian reform involving the changing of laws, regulations, or customs regarding land ownership. Land reform may consist of a government-initiated or government-backed property redistribution, generally of agricultura ...

. Jemmy Hope might be clear that this should not be "a delusive

fixity of tenure hat allowsthe landlord to continue to draw the last potato out of the warm ashes of the poor man's fire". But for the great rural mass of the Irish people this was an existential question upon which neither he nor any central resolution spoke for the Society.

Women

As were the Presbyteries, Volunteer companies and Masonic lodges through which they recruited, the United Irishmen were a male fraternity. In serialising

William Godwin

William Godwin (3 March 1756 – 7 April 1836) was an English journalist, political philosophy, political philosopher and novelist. He is considered one of the first exponents of utilitarianism and the first modern proponent of anarchism. God ...

's ''Enquiry Concerning political Justice'' (1793), the ''Northern Star'' had advised them of the moral and intellectual enlightenment found in an "equal and liberal intercourse" between men and women. The paper had also reviewed and commended

Mary Wollstonecraft

Mary Wollstonecraft (, ; 27 April 1759 – 10 September 1797) was a British writer, philosopher, and advocate of women's rights. Until the late 20th century, Wollstonecraft's life, which encompassed several unconventional personal relationsh ...

's

Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792). But the call was not made for women's civic and political emancipation. In publishing excerpts from Wollstonecraft's work, the ''Star'' focussed entirely upon issues of female education.

In the rival ''

News Letter

The ''News Letter'' is one of Northern Ireland's main daily newspapers, published from Monday to Saturday. It is the world's oldest English-language general daily newspaper still in publication, having first been printed in 1737.

The newspape ...

'', William Bruce argued that this was disingenuous: the "impartial representation of the Irish nation" the United Irishmen embraced in their test or oath implied, he argued, not only equality for Catholics but also that "every woman, in short every rational being shall have equal weight in electing representatives". Drennan did not seek to disabuse Bruce as to "the principle"—he had never seen "a good argument against the right of women to vote"—but in a plea that recalled objections to immediate Catholic emancipation he argued for a "common sense" reading of the test of which he was the author. It might be some generations, he proposed, before "habits of thought, and the artificial ideas of education" are so "worn out" that it would appear "natural" that women should exercise the same rights as men, and thus attain their "full and proper influence in the world".

In Belfast Drennan's sister

Martha McTier and McCracken's sister

Mary-Ann, and in Dublin Emmett's sister

Mary Anne Holmes

Mary Anne Holmes (née Emmet) (10 October 1773 – 10 March 1805) was an Irish poet and writer, connected by her brothers Thomas Addis, and Robert, Emmet, to the republican politics of the United Irishmen.

Life

Holmes was born Mary Anne Emmet ...

and

Margaret King

Margaret King (1773–1835), also known as Margaret King Moore, Lady Mount Cashell and Mrs Mason, was an Anglo-Irish hostess, and a writer of female-emancipatory fiction and health advice. Despite her wealthy aristocratic background, she had re ...

, shared in the reading of Wollstonecraft and of other progressive women writers. As had Tone on behalf of Catholics, Wollstonecraft argued that the incapacities alleged to deny women equality were those that law and usage themselves impose.

Mary Ann McCracken

Mary Ann McCracken (8 July 1770 – 26 July 1866) was a social activist and campaigner in Belfast, Kingdom of Ireland, Ireland, whose extensive correspondence is cited as an important chronicle of her times. Born to a prominent liberal Presbyter ...

, in particular, was articulate in taking to heart the conclusion that women had to reject "their present abject and dependent situation" and secure the liberty without which they could "neither possess virtue or happiness".

Women formed associations within the movement. In October 1796 the ''Northern Star'' published a letter from the secretary of the Society of United Irishwomen. This blamed the English, who made war on the new republics, for the violence of the American and French Revolutions. Denounced as a "violent republican", Martha McTier was the immediate suspect, but denied any knowledge of the society. The true author may have been her friend

Jane Greg

Jane "Jenny" Greg (1749 - 1817) in the 1790s was an Irish republican agitator with connections to radical political circles in England. Although the extent of her activities are unclear, in suppressing the Society of United Irishmen the British co ...

, described by informants as "very active" in Belfast "at the head of the Female Societies" (and by

General Lake

Gerard Lake, 1st Viscount Lake (27 July 1744 – 20 February 1808) was a British general. He commanded British forces during the Irish Rebellion of 1798 and later served as Commander-in-Chief of the military in British India.

Background

He was ...

as being "the most violent creature possible").

Mary Ann McCracken took Drennan's test but stood aloof from the "female societies." No women with "rational ideas of liberty and equality for themselves", she objected, could consent to a separate organisation. There could be "no other reason having them separate, but keeping the women in the dark" and making "tools of them".

In final months before the rising, the paper of the Dublin society, ''The Press'', published two direct addresses to Irish women, both of which "appealed to women as members of a critically-debating public": the first signed Philoguanikos (probably the paper's founder,

Arthur O'Connor), the second signed Marcus (Drennan).

While both appealed to women to take sides, Philoguanikos was clear that women were being asked to act as political beings. He scorns those "brainless bedlams

hoscream in abhorrence of the idea of a female politician".

The letters of Martha McTier and Mary Ann McCracken testify to the role of women as confidantes, sources of advice and bearers of intelligence. R.R. Madden, one of the earliest historians of the United Irishmen, describes various of their activities in the person of an appropriately named Mrs. Risk. By 1797 the Castle informer Francis Higgins was reporting that "women are equally sworn with men" suggesting that some of the women assuming risks for the United Irish cause were taking places beside men in an increasingly clandestine organisation. Middle-class women, such as Mary Moore, who administered the Drennan's test to

William James MacNeven

William James MacNeven (also sometimes rendered as MacNevin or McNevin) (21 March 1763 Ballinahown, near Aughrim, Co. Galway, Ireland - 12 July 1841 New York City) was an Irish physician forced, as a result of his involvement with insurgent Uni ...

,

were reportedly active in the Dublin United Irishmen.

On the role in the movement of peasant and other working women there are fewer sources.

[Keogh, Daire (2003), "Women of 1798: Explaining the silence", in Thomas Bartlett et al. (eds.)]

''1798: A Bicentenary Perspective'', Dublin

Four Courts Press, , pp. 512-528. But in the 1798 uprising they came forward in many capacities, some, as celebrated in later ballads (''

Betsy Gray'' and ''Brave Mary Doyle, the Heroine of New Ross''), as combatants. Under the command of

Henry Luttrell, Earl Carhampton (who, in a celebrated case in 1788,

Archibald Hamilton Rowan

Archibald Hamilton Rowan (1 May 1751 – 1 November 1834), christened Archibald Hamilton (sometimes referred to as Archibald Rowan Hamilton), was a founding member of the Dublin Society of United Irishmen, a political exile in France and the Unit ...

had accused of child rape), troops treated women, young and old, with great brutality.

Spread and radicalisation

Jacobins, Masons and Covenanters

Jacques-Louis de Bougrenet de La Tocnaye, a

French émigré who walked the length and breadth of Ireland in 1796–7, was appalled to encounter in a cabin upon the banks of the

lower Bann the same "nonsense on which the people of France fed themselves before the Revolution". A young labourer treated him to a disposition on "equality, fraternity, and oppression", "reform of Parliament", "abuses in elections", and "tolerance", and such "philosophical discourse" as he had heard from "foppish talkers" in Paris a decade before. In 1793, a magistrate in that same area, near

Coleraine

Coleraine ( ; from ga, Cúil Rathain , 'nook of the ferns'Flanaghan, Deirdre & Laurence; ''Irish Place Names'', page 194. Gill & Macmillan, 2002. ) is a town and civil parish near the mouth of the River Bann in County Londonderry, Northern ...

, County Londonderry, had been complaining of "daily incursions of disaffected people... disseminating the most seditious principles". Until his arrest in September 1796, Thomas Russell (later celebrated in a popular ballad as ''The man from God-knows-where'') was one such agitator. Recruiting for the Society, he ranged from Belfast as far as

Donegal Donegal may refer to:

County Donegal, Ireland

* County Donegal, a county in the Republic of Ireland, part of the province of Ulster

* Donegal (town), a town in County Donegal in Ulster, Ireland

* Donegal Bay, an inlet in the northwest of Ireland b ...

and

Sligo

Sligo ( ; ga, Sligeach , meaning 'abounding in shells') is a coastal seaport and the county town of County Sligo, Ireland, within the western province of Connacht. With a population of approximately 20,000 in 2016, it is the largest urban ce ...

.

In recruiting the first societies among the tenant farmers and market-townsmen of north Down and Antrim, Jemmy Hope made conscious appeal to what he called "the republican spirit" .of resistance "inherent in the principles of Presbyterian community". While presbyteries were divided politically, as they were theologically, leadership was found among church ministers and their elders, and not least from those who were foremost in championing the Scottish

Covenanting

Covenanters ( gd, Cùmhnantaich) were members of a 17th-century Kingdom of Scotland, Scottish religious and political movement, who supported a Presbyterian polity, Presbyterian Church of Scotland, and the primacy of its leaders in religious af ...

tradition. Of those who—bowing to "no king but Jesus"—were elected to preach by the

Reformed Presbyteries in Ulster, it is estimated that half were implicated in the eventual rebellion. In Antrim thousands filled fields to hear the itinerant Reformed preacher William Gibson prophesy the "immediate destruction of the British monarchy". On the pages of the ''Northern Star'' he was joined by

Thomas Ledlie Birch

Thomas Ledlie Birch (1754–1828) was a Presbyterian minister and radical democrat in the Kingdom of Ireland. Forced into American exile following the suppression of the 1798 rebellion, he wrote ''A Letter from An Irish Emigrant'' (1799).

Ass ...

of

Saintfield

Saintfield () is a village and civil parish in County Down, Northern Ireland. It is about halfway between Belfast and Downpatrick on the A7 road. It had a population of 3,381 in the 2011 Census, made up mostly of commuters working in both south ...

who (although adhering to the

Synod of Ulster The (General) Synod of Ulster was the forerunner of the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church in Ireland. It comprised all the clergy of the church elected by their respective local presbyteries (or church elders) and a section of the laity. ...

) likewise anticipated the "overthrow of the Beast".

Allies were also found in the growing network of

masonic lodge

A Masonic lodge, often termed a private lodge or constituent lodge, is the basic organisational unit of Freemasonry. It is also commonly used as a term for a building in which such a unit meets. Every new lodge must be warranted or chartered ...

s. Although it was the rule that "no politics must be brought within the doors of the Lodge", masons were involved in the Volunteer movement and their lodges remained "a battleground for political ideas".

[David Rudland, "1798 and Freemasonry", ''History Ireland'', Vol. 6, no. 4 (Winter 1998), Letters.](_blank)

/ref> As United Irishmen increasingly attracted the unwelcome attention of Dublin Castle and its network of informants, masonry did become both a cover and a model. Drennan, himself a mason, from the outset had anticipated that his "conspiracy" would have "much of the secrecy and somewhat of the ceremonial of Free-Masonry".

The New System

From February 1793 the Crown was at war with the French Republic. This led immediately to heightened tensions in Belfast. On 9 March a body of dragoon

Dragoons were originally a class of mounted infantry, who used horses for mobility, but dismounted to fight on foot. From the early 17th century onward, dragoons were increasingly also employed as conventional cavalry and trained for combat w ...

s rampaged through the town, purportedly provoked by taverns displaying the likenesses of Dumouriez, Mirabeau and Franklin. They withdrew to barracks when, as related by Martha McTier, about 1,000 armed countrymen came into the town and mustered at McCracken's Third Presbyterian. Further "military provocations" saw attacks on the homes of Neilson and others associated with the ''Northern Star'' (wrecked for the final time, and closed, in May 1797). Legislation impressed from Westminster banned extra-parliamentary conventions and suppressed the Volunteers, by then largely a northern movement. They were replaced by a paid militia, its ranks partially filled with conscripted Catholics, and by Yeomanry

Yeomanry is a designation used by a number of units or sub-units of the British Army Reserve, descended from volunteer cavalry regiments. Today, Yeomanry units serve in a variety of different military roles.

History

Origins

In the 1790s, f ...

, an auxiliary force led by local gentry. In May 1794 the Society itself was proscribed.

Toward the end of year, the leading United men in Belfast drafted a constitution for a "new system". Approved by the May 1795 delegate conference of Down and Antrim societies, it sought to reconcile the democratic principles of the republic to come with the requirements of a coordinated, clandestine, organisation. Local societies were to split and replicate so as to remain within a range of 7 to 35 members, and, through delegate conferences, to commission a new five-man provincial directory. Selection to this "committee of public welfare" was by ballot, but in order to preserve secrecy, returning officers were sworn to inform only those elected of the results. Together with directors' capacity to co-opt additional members, this implied an executive free to take its own counsel.[Curtin, Nancy J. (1993), "United Irish organisation in Ulster, 1795-8", in D. Dickson, D. Keogh and K. Whelan, ''The United Irishmen: Republicanism, Radicalism and Rebellion,'' Dublin: Lilliput Press, , pp. 209-222.]

In June 1795, four members of the Ulster executive—Neilson, Russell, McCracken and Robert Simms—met with Tone as he passed through Belfast en route to America and atop Cave Hill swore their celebrated oath "never to desist in our efforts until we had subverted the authority of England over our country, and asserted our independence'". In months that followed, while Tone (travelling via Philadelphia to Paris) lobbied for French assistance, they directed the creation of a shadow military organisation. Under elective command, each society was to drill a company, three companies were to form a battalion, and ten battalions, representing thirty societies, were to coordinate, under a "colonel", as a regiment. From a short list drawn up by the colonels, the executive would then appoint an adjutant-general for the county.

Alliance with the Catholic Defenders

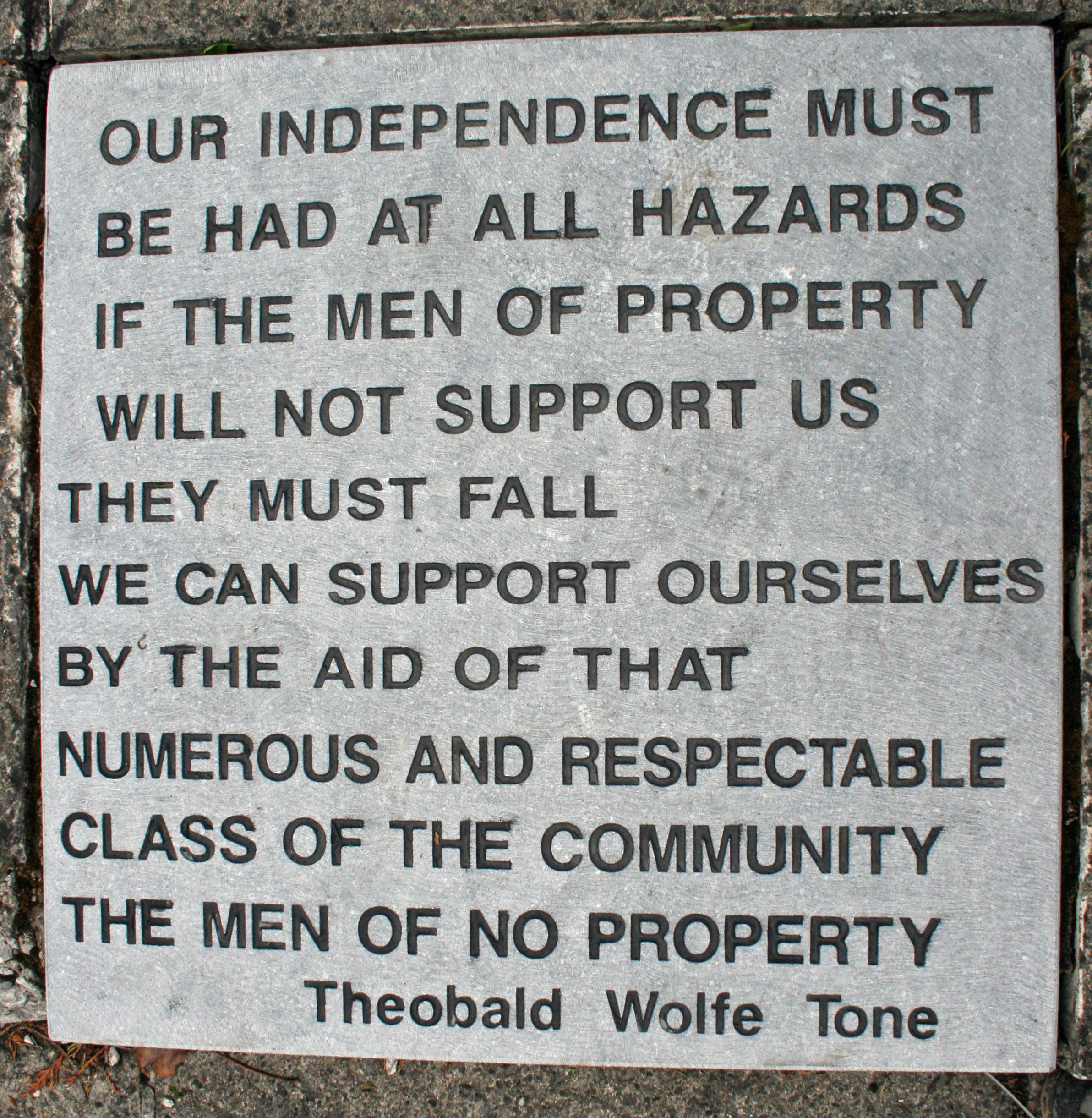

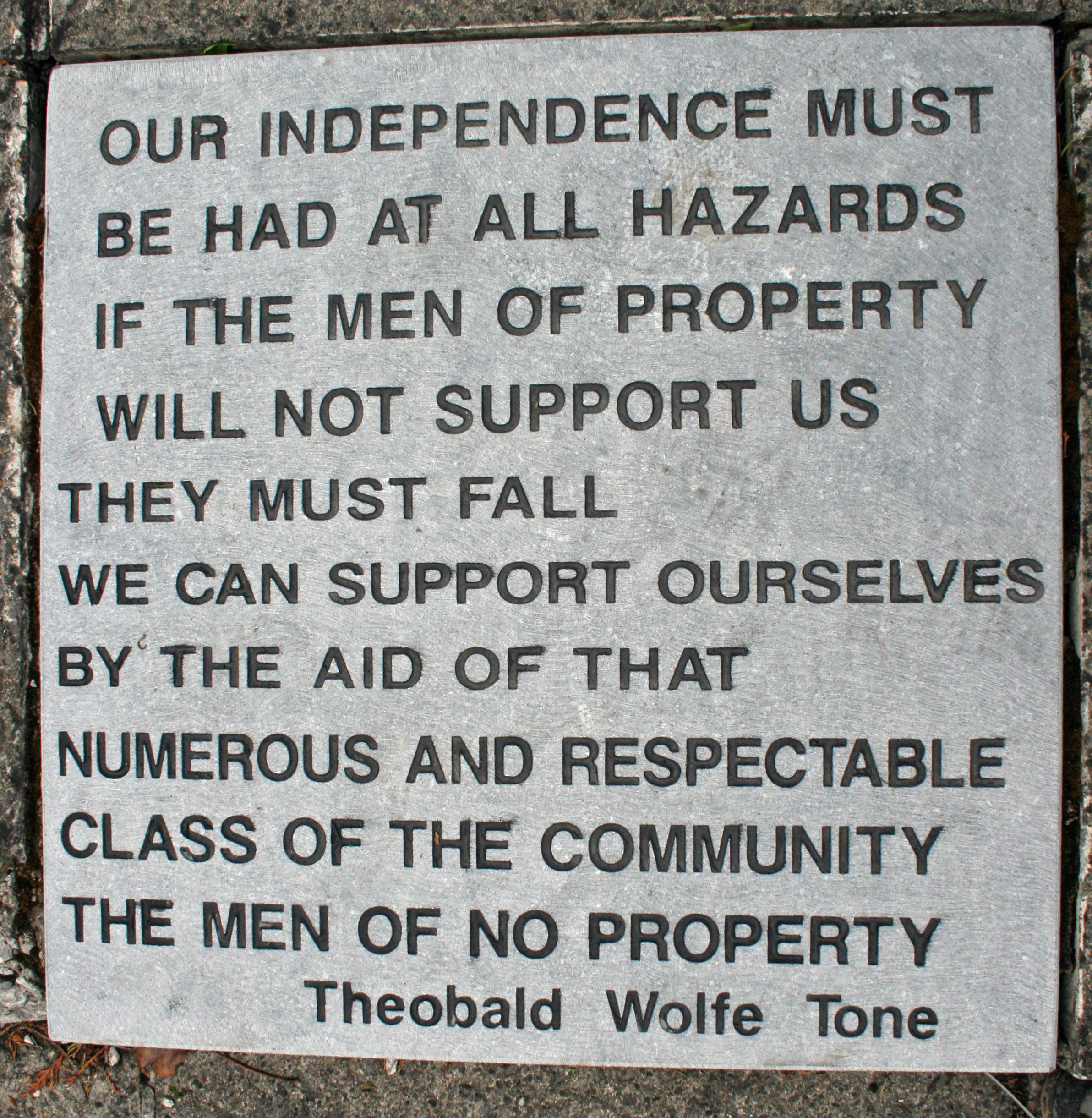

Aware that many of those who had lent their names to the original reform project recoiled from the prospect of insurrection, in March 1796 Tone recorded his understanding of the new resolve: "Our independence must be had at all hazards. If the men of property will not support us, they must fall; we can support ourselves by the aid of that numerous and respectable class of the community, the men of no property".

The greatest body, existing, of men of no property, and with whom alliance was to be sought if a union of Protestant, Catholic and Dissenter was to take to the field, were the

Aware that many of those who had lent their names to the original reform project recoiled from the prospect of insurrection, in March 1796 Tone recorded his understanding of the new resolve: "Our independence must be had at all hazards. If the men of property will not support us, they must fall; we can support ourselves by the aid of that numerous and respectable class of the community, the men of no property".

The greatest body, existing, of men of no property, and with whom alliance was to be sought if a union of Protestant, Catholic and Dissenter was to take to the field, were the Defenders

Defender(s) or The Defender(s) may refer to:

*Defense (military)

*Defense (sports)

**Defender (association football)

Arts and entertainment Film and television

* ''The Defender'' (1989 film), a Canadian documentary

* ''The Defender'' (1994 f ...

. A vigilante response to Peep O'Day raids upon Catholic homes in the mid 1780s, by the early 1790s the Defenders (drawing, like the United Irishmen, on the lodge structure of the Masons) were a secret oath-bound fraternity ranging across Ulster and the Irish midlands. Despite their professed loyalism (members had originally to swear allegiance to the King) Defenderism developed an increasingly a seditious character. Talk in the lodges was of a release from tithes, rents and taxes, and of a French invasion that might allow the repossession of Protestant estates. Arms-buying delegations were sent to London.

Defenders and United Irishmen began to seek one another out. Religion was not a bar to joining the Defenders. In Dublin, in particular, where the Defenderism appealed strongly to a significant body of radical artisans and shopkeepers, Protestants (Napper Tandy prominent among them) joined in the determination to make common cause. Early in 1796, the Dublin Defenders sent a delegation to Belfast for the purpose of laying a "foundation" for a union between parties that, while equally hostile to the state, had been "kept wholly distinct".liberation theology

Liberation theology is a Christian theological approach emphasizing the liberation of the oppressed. In certain contexts, it engages socio-economic analyses, with "social concern for the poor and political liberation for oppressed peoples". I ...

millenarianism

Millenarianism or millenarism (from Latin , "containing a thousand") is the belief by a religious, social, or political group or movement in a coming fundamental transformation of society, after which "all things will be changed". Millenarian ...

. Apocalyptic biblical allusions and calls to "plant the true religion" sat uneasily with the rhetoric of inalienable rights and fealty to a "United States of France and Ireland". Oblivious to the anti-clericalism of the French Republic, many Defender rank-and-file viewed the French through a Jacobite, not Jacobin, lens, as Catholics at war with Protestants. Although Hope and McCracken did much to reach out to the Defenders, recognising the sectarian tensions (Simms reported to Tone that "it would take a great deal of exertion" to keep the Defenders from "producing feuds"), the Belfast Executive chose emissaries from its small number of Catholics.

With their brother-in-law John Magennis, in 1795 the United Irish brothers, Bartholomew

Bartholomew (Aramaic: ; grc, Βαρθολομαῖος, translit=Bartholomaîos; la, Bartholomaeus; arm, Բարթողիմէոս; cop, ⲃⲁⲣⲑⲟⲗⲟⲙⲉⲟⲥ; he, בר-תולמי, translit=bar-Tôlmay; ar, بَرثُولَماو� ...

and Charles Teeling, sons of a wealthy Catholic linen manufacturer in Lisburn

Lisburn (; ) is a city in Northern Ireland. It is southwest of Belfast city centre, on the River Lagan, which forms the boundary between County Antrim and County Down. First laid out in the 17th century by English and Welsh settlers, with ...

, appear to have had command over the Down, Antrim and Armagh Defenders. United Irishmen were able to offer practical assistance: legal counsel, aid and refuge. Catholic victims of the Armagh disturbances

The Armagh disturbances was a period of intense sectarian fighting in the 1780s and 1790s between the Ulster Protestant Peep o' Day Boys and the Roman Catholic Defenders, in County Armagh, Kingdom of Ireland, culminating in the Battle of the Dia ...

and of the Battle of the Diamond

The Battle of the Diamond was a planned confrontation between the Catholic Defenders and the Protestant Peep o' Day Boys that took place on 21 September 1795 near Loughgall, County Armagh, Ireland. The Peep o' Day Boys were the victors, killin ...

(at which Charles Teeling had been present) were sheltered on Presbyterian farms in Down and Antrim, and the goodwill earned used to open the Defenders to trusted republicans. Emmet records these as being able to convince Defenders of something they had only "vaguely" considered, namely the need to separate Ireland from England and to secure its "real as well as nominal independence".

What was decisive, however, was not their agreed political programme: final emancipation and a complete reform of representation. From Dungannon, where he had command, General John Knox, reported that local republicans had been "obliged to throw in the bait of the Abolition of Titles, Reduction of Rents etc.". Nothing less would rouse "the lower orders of Roman Catholics" (and nothing less, he suggested, would in time reconcile them to the alternative to separation, a union with Great Britain).

Dublin and the Catholic Committee

The Society that Tone had helped establish with Drennan in Dublin on his return from Belfast in November 1791 held themselves aloof from the Jacobin, Defender and other radical clubs in the capital. The city's United men also shied away from the New System adopted in Ulster.John Keogh

John Keogh (1740 – 13 November 1817) was an Irish merchant and political activist. He was a leading campaigner for Catholic Emancipation and reform of the Irish Parliament, active in Dublin on the Catholic Committee and, with some ...

. With Tone as his accompanying secretary, in January 1793 Keogh had led a Committee delegation to London where they had an audience with the king. The Catholic Relief Act

The Roman Catholic Relief Bills were a series of measures introduced over time in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries before the Parliaments of Great Britain and the United Kingdom to remove the restrictions and prohibitions impos ...

followed in April. Having only acquired such recognition, many were loathe to abandon the appearance of strict constitutionality. Announcing that there were paid informers in their midst, as early as January 1794 Neilson had urged the Dublin society to re-form on the Ulster model.[Cullen, Louis (1993), "The internal politics of the United Irishmen", in D. Dickson, D. Keogh and K. Whelan, ''The United Irishmen: Republicanism, Radicalism and Rebellion'' (pp. 176-196)'','' Dublin: Lilliput Press, , p. 180] In October there was discussion of a society of sections of 15 member each, each society returning one representative to a central committee.[Cullen, Louis. (1993), "The internal politics of the United Irishmen", in D. Dickson, D. Keogh and K. Whelan eds., ''The United Irishmen: Republicanism, Radicalism and Rebellion,'' Dublin: Lilliput Press, , (pp. 176-196) pp.190, 192.] But the idea of coordinating behind closed doors was rejected on the grounds that "the United Irishmen, as a legal, constitutional reform movement, would not engage in any activity which could not bear the scrutiny of the public or the Castle".[Curtin (1985), p. 474]

Keogh's dismissal of Edmund Burke

Edmund Burke (; 12 January NS.html"_;"title="New_Style.html"_;"title="/nowiki>New_Style">NS">New_Style.html"_;"title="/nowiki>New_Style">NS/nowiki>_1729_–_9_July_1797)_was_an_NS.html"_;"title="New_Style.html"_;"title="/nowiki>New_Style">N ...

's son, Richard Burke, as Committee secretary in 1792, and his replacement by Tone, a known democrat did suggest a political shift. The British Prime Minister Pitt was already canvassing support for a union of Ireland and Great Britain in which Catholics could be freely—because securely—admitted to Parliament. London might yet be an ally in relieving Catholics of the last of the Penal Law restrictions, but it would be as a permanent minority in the enlarged Kingdom, not as a national majority in Ireland. Even that prospect was uncertain. Although tempered since the Gordon Riots

The Gordon Riots of 1780 were several days of rioting in London motivated by anti-Catholic sentiment. They began with a large and orderly protest against the Papists Act 1778, which was intended to reduce official discrimination against Briti ...

, Anti-Popery remained an important strain in English politics. Meanwhile, Drennan recalls, "Catholics were being driven to despair" and were prepared to "go to extremities" rather than again be denied political equality.

Drennan was nonetheless sceptical of their intentions. Suspecting that their object remained "selfish" (i.e. focused on emancipation rather than on separation and democratic reform) and recognizing their alarm at the anti-clericalism of the French Republic, Drennan, up until his trial for sedition in May 1794, promoted what he called an "inner Society" in Dublin, "''Protestant but National''".Reverend William Jackson

The Reverend William Jackson (1737 – 30 April 1795) was a noted Irish preacher, journalist, playwright, and radical. He was arrested in Dublin in 1794 following meetings with the United Irish leaders Theobald Wolfe Tone and Archibald Hamilt ...

. An agent of the French Committee of Public Safety

The Committee of Public Safety (french: link=no, Comité de salut public) was a committee of the National Convention which formed the provisional government and war cabinet during the Reign of Terror, a violent phase of the French Revolution. S ...

, Jackson had been having meetings with Tone in the prison cell of Archibald Hamilton Rowan

Archibald Hamilton Rowan (1 May 1751 – 1 November 1834), christened Archibald Hamilton (sometimes referred to as Archibald Rowan Hamilton), was a founding member of the Dublin Society of United Irishmen, a political exile in France and the Unit ...

. Whether because of his association with the Catholic Committee or his family's connections, Tone was allowed to go into American exile, while Rowan, who was serving time for distributing Drennan's seditious appeal to Volunteers, managed to flee the country. The scandal induced Thomas Troy, Catholic Archbishop of Dublin

The Archbishop of Dublin is an archepiscopal title which takes its name after Dublin, Ireland. Since the Reformation, there have been parallel apostolic successions to the title: one in the Catholic Church and the other in the Church of Ireland ...

and Papal legate

300px, A woodcut showing Henry II of England greeting the pope's legate.

A papal legate or apostolic legate (from the ancient Roman title '' legatus'') is a personal representative of the pope to foreign nations, or to some part of the Catholic ...

, to caution against the "fascinating illusions" of French principles and, in advance of the Society's proscription, to threaten any Catholic taking the United test with excommunication

Excommunication is an institutional act of religious censure used to end or at least regulate the communion of a member of a congregation with other members of the religious institution who are in normal communion with each other. The purpose ...

. Lingering hopes of a return to open agitation were dashed in March the following year when, after endorsing Catholic admission to Parliament, the newly arrived Lord Lieutenant, William Fitzwilliam was summarily recalled.[Lindsay, Dierdre (1993), "The Fitzwilliam episode revisited", in D. Dickson, D. Keogh and K. Whelan, ''The United Irishmen: Republicanism, Radicalism and Rebellion,'' Dublin: Lilliput Press, , pp.197-208.]

Encouraged by the presence in Dublin of veterans of the northern movement, such as Samuel Nielson, Thomas Russell, and James Hope,

Mobilisation and repression

On 15 December 1796, Tone arrived off Bantry Bay

Bantry Bay ( ga, Cuan Baoi / Inbhear na mBárc / Bádh Bheanntraighe) is a bay located in County Cork, Ireland. The bay runs approximately from northeast to southwest into the Atlantic Ocean. It is approximately 3-to-4 km (1.8-to-2.5 mil ...

with a French fleet carrying about 14,450 men, and a large supply of war material, under the command of Louis Lazare Hoche

Louis Lazare Hoche (; 24 June 1768 – 19 September 1797) was a French military leader of the French Revolutionary Wars. He won a victory over Royalist forces in Brittany. His surname is one of the names inscribed under the Arc de Triomphe, on ...

. A gale prevented a landing. Hoche's unexpected death on his return to France was a blow to what had been Tone's adept handling of the politics of the French Directory

The Directory (also called Directorate, ) was the governing five-member committee in the French First Republic from 2 November 1795 until 9 November 1799, when it was overthrown by Napoleon Bonaparte in the Coup of 18 Brumaire and replaced b ...

. With the forces (and ambition) that might have allowed a second attempt upon Ireland, Hoche's rival, Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader wh ...

, sailed in May 1798 for Egypt.

Bantry Bay nonetheless made real the prospect of French intervention for which it was clear the forces available to the Crown

The Crown is the state in all its aspects within the jurisprudence of the Commonwealth realms and their subdivisions (such as the Crown Dependencies, overseas territories, provinces, or states). Legally ill-defined, the term has differ ...

were unprepared. At the same time, the government was shutting down attempts at political conciliation. In the new year it announced that any further discussion in parliament of grievances serving in the country as "pretexts for treasonable practices" would result in adjournment.

Insurrection Act

with administering the United test to a soldier. The movement's first acclaimed martyr, he was hanged in October. Orr's arrest in Antrim signalled the onset of General Lake

Gerard Lake, 1st Viscount Lake (27 July 1744 – 20 February 1808) was a British general. He commanded British forces during the Irish Rebellion of 1798 and later served as Commander-in-Chief of the military in British India.

Background

He was ...

's "dragooning of Ulster". For the authorities its urgency was underscored by public expressions of solidarity with those detained. The ''Northern Star'' reported that after Orr was detained, between five and six hundred of his neighbours assembled and brought in his entire harvest. When Samuel Nielson was taken in September, fifteen hundred people were said to have dug his potatoes in seven minutes. Such "hasty diggings" (traditionally accorded by families visited by misfortune) often occasioned mustering and drilling —men, shouldering their spades, marching four to six deep accompanied by the sounding of horns.Cavan

Cavan ( ; ) is the county town of County Cavan in Ireland. The town lies in Ulster, near the border with County Fermanagh in Northern Ireland. The town is bypassed by the main N3 road that links Dublin (to the south) with Enniskillen, Bal ...

killing eleven and injurying many more.

With his troops' reputation for half-hanging, pitch-capping and other interrogative refinements travelling before him, at the end of 1797 Lake tuned his attention to disarming Leinster

Leinster ( ; ga, Laighin or ) is one of the provinces of Ireland, situated in the southeast and east of Ireland. The province comprises the ancient Kingdoms of Meath, Leinster and Osraige. Following the 12th-century Norman invasion of ...

and Munster

Munster ( gle, an Mhumhain or ) is one of the provinces of Ireland, in the south of Ireland. In early Ireland, the Kingdom of Munster was one of the kingdoms of Gaelic Ireland ruled by a "king of over-kings" ( ga, rí ruirech). Following t ...

. As in the north, following Bantry societies in the south flooded with new members. In Leinster the new system took hold: the various republican clubs and cover lodges, and much of Defender network, were marshalled through delegate committees under a provincial executive in Dublin[Graham, Thomas. (1993), "'An Union of Power'? The United Irish organisation, 1795-17988", in D. Dickson, D. Keogh and K. Whelan, ''The United Irishmen: Republicanism, Radicalism and Rebellion,'' Dublin: Lilliput Press, , pp. 244-255.] Among others who were to serve on the executive were Thomas Addis Emmet

Thomas Addis Emmet (24 April 176414 November 1827) was an Irish and American lawyer and politician. He was a senior member of the revolutionary Irish republican group United Irishmen in the 1790s. He served as Attorney General of New York from ...

; Richard McCormick, Tone's replacement as secretary to the Catholic Committee; the Sheares brothers

The Sheares Brothers, Henry (1753–98), and John (1766–1798) were Irish lawyers and republicans. After witnessing revolutionary events in Paris, in 1793 they joined the Society of United Irishmen for whom they organised in Cork and in Dubli ...

(witnesses to the execution of Louis XVI

Louis XVI (''Louis-Auguste''; ; 23 August 175421 January 1793) was the last King of France before the fall of the monarchy during the French Revolution. He was referred to as ''Citizen Louis Capet'' during the four months just before he was ...

) and two disillusioned parliamentary patriots: the future Napoleonic general Arthur O'Connor and the popular Lord Edward Fitzgerald

Lord Edward FitzGerald (15 October 1763 – 4 June 1798) was an Irish aristocrat who abandoned his prospects as a distinguished veteran of British service in the American War of Independence, and as an Irish Parliamentarian, to embrace the caus ...

.

"Unionising" in Britain

United Scotsmen

The war with France was also used to crush reformers in Great Britain, costing the United Irishmen the liberty of friends and allies. In 1793 in Edinburgh

Edinburgh ( ; gd, Dùn Èideann ) is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. Historically part of the county of Midlothian (interchangeably Edinburghshire before 1921), it is located in Lothian ...

, Thomas Muir, whom Rowan and Drennan had feted in Dublin, with three other of his Friends of the People were sentenced to transportation

Transport (in British English), or transportation (in American English), is the intentional movement of humans, animals, and goods from one location to another. Modes of transport include air, land ( rail and road), water, cable, pipelin ...

to Botany Bay

Botany Bay ( Dharawal: ''Kamay''), an open oceanic embayment, is located in Sydney, New South Wales, Australia, south of the Sydney central business district. Its source is the confluence of the Georges River at Taren Point and the Cook ...

(Australia). The judge seized on Muir's connection to the "ferocious" Mr. Rowan (Rowan had challenged Robert Dundas, the Lord Advocate

His Majesty's Advocate, known as the Lord Advocate ( gd, Morair Tagraidh, sco, Laird Advocat), is the chief legal officer of the Scottish Government and the Crown in Scotland for both civil and criminal matters that fall within the devolved p ...

of Scotland, to a duel) and on the United Irishmen papers found in his possession.

There followed in England the 1794 Treason Trials

The 1794 Treason Trials, arranged by the administration of William Pitt, were intended to cripple the British radical movement of the 1790s. Over thirty radicals were arrested; three were tried for high treason: Thomas Hardy, John Horne Tooke an ...

and, when these collapsed, the 1795 Treason Act

Treason Act or Treasons Act (and variations thereon) or Statute of Treasons is a stock short title used for legislation in the United Kingdom and in the Republic of Ireland on the subject of treason and related offences.

Several Acts on the ...

and Seditious Meetings Act. The measures were directed at the activities of the London Corresponding Society

The London Corresponding Society (LCS) was a federation of local reading and debating clubs that in the decade following the French Revolution agitated for the democratic reform of the British Parliament. In contrast to other reform associa ...

and other radical groups among whom, as ambassadors for the Irish cause, Roger O'Connor

Roger O'Connor (1762-1834) was an Irish nationalist and writer, known for the controversies surrounding his life and writings, notably his fanciful history of the Irish people, the ''Chronicles of Eri''. He was the brother of the United Irishman ...

and Jane Greg

Jane "Jenny" Greg (1749 - 1817) in the 1790s was an Irish republican agitator with connections to radical political circles in England. Although the extent of her activities are unclear, in suppressing the Society of United Irishmen the British co ...

had been cultivating understanding and support.United Scotsmen

The Society of the United Scotsmen was an organisation formed in Scotland in the late 18th century and sought widespread political reform throughout Great Britain. It grew out of previous radical movements such as the ''Friends of the People Socie ...

early in 1797, in their view it was as little more than a Scottish branch of the United Irishmen. The Resolutions and Constitution of the United Scotsmen (1797) was "a verbatim copy of the constitutional document of the United Irishmen, apart from the substitution of the words 'North Britain' for 'Irishmen'". At their height, during a summer of anti-militia riots, the United Scotsmen counted upwards of 10,000 members, the backbone formed (as had increasingly been the case for Belfast and Dublin societies) by artisan journeymen and weavers.

United Englishmen, United Britons

With the encouragement of Irish and Scottish visitors, the manufacturing districts of northern England saw the first cells of the United Englishmen formed in late 1796. Their clandestine proceedings, oath taking, and advocacy of physical force "mirrored that of their Irish inspirators", and they followed Ulster system of parish-based cells (societies capped at thirty or thirty-six).James Coigly

Father James Coigly (''aka'' James O'Coigley and Jeremiah Quigley) (1761 – 7 June 1798) was a Roman Catholic priest in Ireland active in the republican movement against the British Crown and the kingdom's Protestant Ascendancy. He serve ...

(a veteran of unionising activities during the Armagh Disturbances

The Armagh disturbances was a period of intense sectarian fighting in the 1780s and 1790s between the Ulster Protestant Peep o' Day Boys and the Roman Catholic Defenders, in County Armagh, Kingdom of Ireland, culminating in the Battle of the Dia ...

)Stockport

Stockport is a town and borough in Greater Manchester, England, south-east of Manchester, south-west of Ashton-under-Lyne and north of Macclesfield. The River Goyt and Tame merge to create the River Mersey here.

Most of the town is withi ...

, Bolton

Bolton (, locally ) is a large town in Greater Manchester in North West England, formerly a part of Lancashire. A former mill town, Bolton has been a production centre for textiles since Flemish weavers settled in the area in the 14th ...

, Warrington

Warrington () is a town and unparished area in the borough of the same name in the ceremonial county of Cheshire, England, on the banks of the River Mersey. It is east of Liverpool, and west of Manchester. The population in 2019 was estimat ...

and Birmingham

Birmingham ( ) is a city and metropolitan borough in the metropolitan county of West Midlands in England. It is the second-largest city in the United Kingdom with a population of 1.145 million in the city proper, 2.92 million in the We ...

.London Corresponding Society

The London Corresponding Society (LCS) was a federation of local reading and debating clubs that in the decade following the French Revolution agitated for the democratic reform of the British Parliament. In contrast to other reform associa ...

: among them United Irishman Edward Despard

Edward Marcus Despard (175121 February 1803), an Kingdom of Ireland, Irish officer in the service of the The Crown, British Crown, gained notoriety as a colonial administrator for refusing to recognise racial distinctions in law and, following his ...

, brothers Benjamin and John Binns, and LCS president Alexander Galloway. Meetings were held at which delegates from London, Scotland and the regions resolved "to overthrow the present Government, and to join the French as soon as they made a landing in England".French Directory

The Directory (also called Directorate, ) was the governing five-member committee in the French First Republic from 2 November 1795 until 9 November 1799, when it was overthrown by Napoleon Bonaparte in the Coup of 18 Brumaire and replaced b ...

a further address from the United Britons. While its suggestion of a mass movement primed for insurrection was scarcely credible, it was deemed sufficient proof of the intention to induce a French invasion. The united movement was broken up by internment

Internment is the imprisonment of people, commonly in large groups, without charges or intent to file charges. The term is especially used for the confinement "of enemy citizens in wartime or of terrorism suspects". Thus, while it can simp ...

and Coigly was hanged.

Alleged role in the 1797 naval mutinies

In justifying the suspension of ''habeas corpus

''Habeas corpus'' (; from Medieval Latin, ) is a recourse in law through which a person can report an unlawful detention or imprisonment to a court and request that the court order the custodian of the person, usually a prison official, ...

'' the authorities were more than ready to see the hand not only of English radicals but also, in the large Irish contingent among the sailors, of United Irishmen in the Spithead and Nore mutinies of April and May 1797. The United Irish were reportedly behind the resolution of the Nore mutineers to hand the fleet over to the French "as the only government that understands the Rights of Man". Much was made of Valentine Joyce, a leader at Spithead, described by Edmund Burke

Edmund Burke (; 12 January NS.html"_;"title="New_Style.html"_;"title="/nowiki>New_Style">NS">New_Style.html"_;"title="/nowiki>New_Style">NS/nowiki>_1729_–_9_July_1797)_was_an_NS.html"_;"title="New_Style.html"_;"title="/nowiki>New_Style">N ...

as a "seditious Belfast clubist", (and recorded by R. R. Madden as having been an Irish Volunteer in 1778).

That the Valentine Joyce in question was Irish and a republican has been disputed, and while that "rebellious paper, the ''Northern Star''" may have circulated as reported among the mutineers, no evidence has emerged of a concerted United Irish plot to subvert the fleet.[Roger, N.A.M.(2003), "Mutiny or subversion? Spithead and the Nore", in Thomas Bartlett et al. (eds.)]

''1798: A Bicentenary Perspective'', Dublin

Four Courts Press, , pp. 549-564. In Ireland there was talk of seizing British warships as part of a general insurrection, but it was only after the Spithead and Nore mutinies that United Irishmen awoke to the effectiveness of formulating sedition within the Royal Navy.

There were a number of mutinies instigated by Irish sailors in 1798. Aboard ''HMS Defiance'' a court martial took evidence of oaths of allegiance to the United Irishmen and sentenced eleven men to hang.

1798 Rebellion

The call from Dublin

The movement never realised the national directory envisaged in constitution of May 1794. Its leadership remained split between the executives of the two organised provinces, Ulster and Leinster. In June 1797, they had met together in Dublin to consider northern demands for an immediate rising. The meeting broke up in disarray, with many of the Ulster delegates, fearful of arrest, fleeing abroad. In the north, the Uniuted societies had not recovered from their decapitation the previous September: from arrests (personally supervised by Castlereagh) that, in addition to Neilson, had netted Thomas Russell, Charles Teeling, Henry Joy McCracken and Robert Simms. Their removal had opened up the leadership in Belfast to less reliable elements, including government informants.Kildare

Kildare () is a town in County Kildare, Ireland. , its population was 8,634 making it the 7th largest town in County Kildare. The town lies on the R445, some west of Dublin – near enough for it to have become, despite being a regional ce ...

and Meath, and broke new ground in the midlands and the south-east.[Graham, Thomas (1993), "A Union of Power: the United Irish Organisation 1795-1798", in David Dickson, Daire Keogh and Kevin Whelan eds., ''The United Irishment, Republicanism, Radicalism and Rebellion'', (pp. 243-255), Dubllin, Liiliput, , pp. 250-253] In February 1798, a return prepared by Fitzgerald computed the number United Irishmen, nationwide, at 269,896. It certain that the figure was not a measure of the number prepared to turn out, particularly in the absence of the French. Most would have been able to arm themselves only with simple pikes (of these the authorities had seized in the previous year 70,630 compared to just 4,183 blunderbuss

The blunderbuss is a firearm with a short, large caliber barrel which is flared at the muzzle and frequently throughout the entire bore, and used with shot and other projectiles of relevant quantity or caliber. The blunderbuss is commonly consid ...

es and 225 musket

A musket is a muzzle-loaded long gun that appeared as a smoothbore weapon in the early 16th century, at first as a heavier variant of the arquebus, capable of penetrating plate armour. By the mid-16th century, this type of musket gradually di ...

barrels). The movement, nonetheless, had withstood the government's countermeasures, and seditious propaganda and preparation continued.Sheares brothers

The Sheares Brothers, Henry (1753–98), and John (1766–1798) were Irish lawyers and republicans. After witnessing revolutionary events in Paris, in 1793 they joined the Society of United Irishmen for whom they organised in Cork and in Dubli ...

, resolved on a general uprising for 23 May. The United army in Dublin was to seize strategic points in the city, while the armies in the surrounding counties would throw up a cordon and advance into its centre. As soon as these developments were signalled by halting mail coaches from the capital, the rest of the country was to rise.

The South

Some historians conclude that what connects the United Irishmen to most widespread and sustained of the uprisings in 1798 are "accidents of time and place, rather than any real community of interest".

Some historians conclude that what connects the United Irishmen to most widespread and sustained of the uprisings in 1798 are "accidents of time and place, rather than any real community of interest". Daniel O'Connell

Daniel O'Connell (I) ( ga, Dónall Ó Conaill; 6 August 1775 – 15 May 1847), hailed in his time as The Liberator, was the acknowledged political leader of Ireland's Roman Catholic majority in the first half of the 19th century. His mobilizat ...

, who abhorred the rebellion, may have been artful in proposing that there had been no United Irishmen in Wexford

Wexford () is the county town of County Wexford, Ireland. Wexford lies on the south side of Wexford Harbour, the estuary of the River Slaney near the southeastern corner of the island of Ireland. The town is linked to Dublin by the M11/N11 ...

. But his view that the uprising in Wexford had been "forced forward by the establishment of Orange lodges and the whipping and torturing and things of that kind" was to be widely accepted

The Wexford Rebellion

The Wexford Rebellion refers to the outbreak in County Wexford, Ireland in May 1798 of the Society of United Irishmen's rebellion against the British rule. It was the most successful and most destructive of all the uprisings that occurred throu ...

broke not in the securely Catholic south of the county, where there had been greater political organisation, but in the sectarian-divided north and centre which had seen previous agrarian disturbances. The absence of an at least belated United organisation is disputed, but it is agreed that the trigger was the arrival on 26 May 1798 of the notorious North Cork Militia.

The insurgents swept south through Wexford Town

Wexford () is the county town of County Wexford, Ireland. Wexford lies on the south side of Wexford Harbour, the estuary of the River Slaney near the southeastern corner of the island of Ireland. The town is linked to Dublin by the M11/N11 ...

meeting their first reversal at New Ross