''Maine'' was a

United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

ship that sank in

Havana Harbor on February 15, 1898, contributing to the outbreak of the

Spanish–American War

, partof = the Philippine Revolution, the decolonization of the Americas, and the Cuban War of Independence

, image = Collage infobox for Spanish-American War.jpg

, image_size = 300px

, caption = (clock ...

in April. U.S. newspapers, engaging in

yellow journalism

Yellow journalism and yellow press are American terms for journalism and associated newspapers that present little or no legitimate, well-researched news while instead using eye-catching headlines for increased sales. Techniques may include ...

to boost circulation, claimed that the

Spanish were responsible for the ship's destruction. The phrase, "Remember the ''Maine!'' To hell with Spain!" became a rallying cry for action. Although the ''Maine'' explosion was not a direct cause, it served as a catalyst that accelerated the events leading up to the war.

''Maine'' is described as an

armored cruiser

The armored cruiser was a type of warship of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It was designed like other types of cruisers to operate as a long-range, independent warship, capable of defeating any ship apart from a battleship and fast eno ...

or second-class

battleship

A battleship is a large armour, armored warship with a main artillery battery, battery consisting of large caliber guns. It dominated naval warfare in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The term ''battleship'' came into use in the late 1 ...

, depending on the source. Commissioned in 1895, she was the first U.S. Navy ship to be named after the state of

Maine

Maine () is a state in the New England and Northeastern regions of the United States. It borders New Hampshire to the west, the Gulf of Maine to the southeast, and the Canadian provinces of New Brunswick and Quebec to the northeast and nor ...

. ''Maine'' and the similar battleship were both represented as an advance in American warship design, reflecting the latest European naval developments. Both ships had two gun turrets staggered

''en échelon'', and full sailing masts were omitted due to the increased reliability of steam engines.

Due to a protracted 9-year construction period, ''Maine'' and ''Texas'' were obsolete by the time of completion.

Far more advanced vessels were either in service or nearing completion that year.

''Maine'' was sent to Havana Harbor to protect U.S. interests during the

Cuban War of Independence

The Cuban War of Independence (), fought from 1895 to 1898, was the last of three liberation wars that Cuba fought against Spain, the other two being the Ten Years' War (1868–1878) and the Little War (1879–1880). The final three months ...

. She exploded and sank on the evening of 15 February 1898, killing 268 sailors, or three-quarters of her crew. In 1898, a U.S. Navy board of inquiry ruled that the ship had been sunk by an external explosion from a mine. However, some U.S. Navy officers disagreed with the board, suggesting that the ship's magazines had been ignited by a spontaneous fire in a coal bunker. The coal used in ''Maine'' was bituminous, which is known for releasing

firedamp, a mixture of gases composed primarily of flammable

methane

Methane ( , ) is a chemical compound with the chemical formula (one carbon atom bonded to four hydrogen atoms). It is a group-14 hydride, the simplest alkane, and the main constituent of natural gas. The relative abundance of methane ...

that is prone to spontaneous explosions. An investigation by Admiral

Hyman Rickover

Hyman G. Rickover (January 27, 1900 – July 8, 1986) was an admiral in the U.S. Navy. He directed the original development of naval nuclear propulsion and controlled its operations for three decades as director of the U.S. Naval Reactors off ...

in 1974 agreed with the coal fire hypothesis. The cause of her sinking remains a subject of debate.

The ship lay at the bottom of the harbor until 1911, when a

cofferdam

A cofferdam is an enclosure built within a body of water to allow the enclosed area to be pumped out. This pumping creates a dry working environment so that the work can be carried out safely. Cofferdams are commonly used for construction or re ...

was built around it.

The hull was patched up until the ship was afloat, then she was towed to sea and sunk. ''Maine'' now lies on the sea-bed below the surface. The ship's main mast is now

a memorial in Arlington National Cemetery.

Background

In response to the delivery of the in 1883 and the acquisition of other modern armored warships from Europe by Brazil, Argentina and

Chile

Chile, officially the Republic of Chile, is a country in the western part of South America. It is the southernmost country in the world, and the closest to Antarctica, occupying a long and narrow strip of land between the Andes to the eas ...

, the head of the House Naval Affairs Committee,

Hilary A. Herbert

Hilary Abner Herbert (March 12, 1834 – March 6, 1919) was Secretary of the Navy in the second administration of President Grover Cleveland. He also served as a member of the United States House of Representatives from Alabama.

Biography ...

, stated to Congress: "if all this old navy of ours were drawn up in battle array in mid-ocean and confronted by ''Riachuelo'' it is doubtful whether a single vessel bearing the American flag would get into port." These developments helped bring to a head a series of discussions that had been taking place at the Naval Advisory Board since 1881. The board knew at that time that the U.S. Navy could not challenge any major European fleet; at best, it could wear down an opponent's merchant fleet and hope to make some progress through general attrition there. Moreover, projecting naval force abroad through the use of battleships ran counter to the government policy of

isolationism

Isolationism is a political philosophy advocating a national foreign policy that opposes involvement in the political affairs, and especially the wars, of other countries. Thus, isolationism fundamentally advocates neutrality and opposes entangl ...

. While some on the board supported a strict policy of commerce raiding, others argued it would be ineffective against the potential threat of enemy battleships stationed near the American coast. The two sides remained essentially deadlocked until ''Riachuelo'' manifested.

The board, now confronted with the concrete possibility of hostile warships operating off the American coast, began planning for ships to protect it in 1884. The ships had to fit within existing docks and had to have a shallow

draft to enable them to use all the major American ports and bases. The maximum

beam was similarly fixed, and the board concluded that at a length of about , the maximum displacement would be about 7,000 tons. A year later the

Bureau of Construction and Repair The Bureau of Construction and Repair (BuC&R) was the part of the United States Navy which from 1862 to 1940 was responsible for supervising the design, construction, conversion, procurement, maintenance, and repair of ships and other craft for the ...

(C & R) presented two designs to Secretary of the Navy

William Collins Whitney

William Collins Whitney (July 5, 1841February 2, 1904) was an American political leader and financier and a prominent descendant of the John Whitney family. He served as Secretary of the Navy in the first administration of President Grover Cl ...

, one for a 7,500-ton battleship and one for a 5,000-ton

armored cruiser

The armored cruiser was a type of warship of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It was designed like other types of cruisers to operate as a long-range, independent warship, capable of defeating any ship apart from a battleship and fast eno ...

. Whitney decided instead to ask Congress for two 6,000-ton warships, and they were authorized in August 1886. A design contest was held, asking

naval architect This is the top category for all articles related to architecture and its practitioners.

{{Commons category, Architecture occupations

Design occupations

Occupations ...

s to submit designs for the two ships: armored cruiser ''Maine'' and battleship . It was specified that ''Maine'' had to have a speed of , a

ram bow

A ram was a weapon fitted to varied types of ships, dating back to antiquity. The weapon comprised an underwater prolongation of the bow of the ship to form an armoured beak, usually between 2 and 4 meters (6–12 ft) in length. This would be dri ...

, and a double bottom, and be able to carry two

torpedo boat

A torpedo boat is a relatively small and fast naval ship designed to carry torpedoes into battle. The first designs were steam-powered craft dedicated to ramming enemy ships with explosive spar torpedoes. Later evolutions launched variants of ...

s. Her armament was specified as: four guns, six guns, various light weapons, and four torpedo tubes. It was specifically stated that the main guns "must afford heavy bow and stern fire." Armor thickness and many details were also defined. Specifications for ''Texas'' were similar, but demanded a main battery of two guns and slightly thicker armor.

The winning design for ''Maine'' was from

Theodore D. Wilson, who served as chief constructor for C & R and was a member on the Naval Advisory Board in 1881. He had designed a number of other warships for the navy. The winning design for ''Texas'' was from a British designer, William John, who was working for the

Barrow Shipbuilding Company

Vickers Shipbuilding and Engineering, Ltd (VSEL) was a shipbuilding company based at Barrow-in-Furness, Cumbria in northwest England that built warships, civilian ships, submarines and armaments. The company was historically the Naval Construct ...

at that time. Both designs resembled the Brazilian battleship ''Riachuelo'', having the main gun turrets sponsoned out over the sides of the ship and

echeloned. The winning design for ''Maine'', though conservative and inferior to other contenders, may have received special consideration due to a requirement that one of the two new ships be American–designed.

Congress authorized construction of ''Maine'' on 3 August 1886, and her keel was laid down on 17 October 1888, at the

Brooklyn Navy Yard

The Brooklyn Navy Yard (originally known as the New York Navy Yard) is a shipyard and industrial complex located in northwest Brooklyn in New York City, New York. The Navy Yard is located on the East River in Wallabout Bay, a semicircular bend ...

. She was the largest vessel built in a U.S. Navy yard up to that time.

Design

''Maine''s building time of nine years was unusually protracted, due to the limits of U.S. industry at the time. (The delivery of her armored plating took three years and a fire in the drafting room of the building yard, where ''Maine''s working set of

blueprint

A blueprint is a reproduction of a technical drawing or engineering drawing using a contact print process on light-sensitive sheets. Introduced by Sir John Herschel in 1842, the process allowed rapid and accurate production of an unlimited number ...

s were stored, caused further delay.) In the nine years between her being laid down and her completion, naval tactics and technology changed radically and left ''Maine''s role in the navy ill-defined. At the time she was laid down, armored cruisers such as ''Maine'' were intended to serve as small battleships on overseas service and were built with heavy belt armor. Great Britain, France and Russia had constructed such ships to serve this purpose and sold others of this type, including ''Riachuelo'', to second-rate navies. Within a decade, this role had changed to commerce raiding, for which fast, long-range vessels, with only limited armor protection, were needed. The advent of lightweight armor, such as

Harvey steel, made this transformation possible.

As a result of these changing priorities, ''Maine'' was caught between two separate positions and could not perform either one adequately. She lacked both the armor and firepower to serve as a ship-of-the-line against enemy battleships and the speed to serve as a cruiser. Nevertheless, she was expected to fulfill more than one tactical function. In addition, because of the potential of a warship sustaining blast damage to herself from cross-deck and end-on fire, ''Maine''s main-gun arrangement was obsolete by the time she entered service.

General characteristics

''Maine'' was long

overall, with a beam of , a maximum draft of and a displacement of . She was divided into 214 watertight compartments. A centerline longitudinal watertight

bulkhead separated the engines and a

double bottom

A double hull is a ship hull design and construction method where the bottom and sides of the ship have two complete layers of watertight hull surface: one outer layer forming the normal hull of the ship, and a second inner hull which is some dist ...

covered the hull only from the foremast to the aft end of the armored citadel, a distance of . She had a

metacentric height of as designed and was fitted with a ram bow.

''Maine''s hull was long and narrow, more like a cruiser than that of ''Texas'', which was wide-beamed. Normally, this would have made ''Maine'' the faster ship of the two. ''Maine''s weight distribution was ill-balanced, which slowed her considerably. Her main turrets, awkwardly situated on a cut-away gundeck, were nearly awash in bad weather. Because they were mounted toward the ends of the ship, away from its center of gravity, ''Maine'' was also prone to greater motion in heavy seas. While she and ''Texas'' were both considered seaworthy, the latter's high hull and guns mounted on her main deck made her the drier ship.

The two main gun turrets were

sponson

Sponsons are projections extending from the sides of land vehicles, aircraft or watercraft to provide protection, stability, storage locations, mounting points for weapons or other devices, or equipment housing.

Watercraft

On watercraft, a spon ...

ed out over the sides of the ship and echeloned to allow both to fire fore and aft. The practice of ''en echelon'' mounting had begun with Italian battleships designed in the 1870s by

Benedetto Brin and followed by the British Navy with , which was laid down in 1874 but not commissioned until October 1881. This gun arrangement met the design demand for heavy end-on fire in a ship-to-ship encounter, tactics which involved

ramming

In warfare, ramming is a technique used in air, sea, and land combat. The term originated from battering ram, a siege weapon used to bring down fortifications by hitting it with the force of the ram's momentum, and ultimately from male sheep. Thus, ...

the enemy vessel. The wisdom of this tactic was largely theoretical at the time it was implemented. A drawback of an ''en echelon'' layout limited the ability for a ship to fire

broadside

Broadside or broadsides may refer to:

Naval

* Broadside (naval), terminology for the side of a ship, the battery of cannon on one side of a warship, or their near simultaneous fire on naval warfare

Printing and literature

* Broadside (comic ...

, a key factor when employed in a

line of battle

The line of battle is a tactic in naval warfare in which a fleet of ships forms a line end to end. The first example of its use as a tactic is disputed—it has been variously claimed for dates ranging from 1502 to 1652. Line-of-battle tacti ...

. To allow for at least partial broadside fire, ''Maine''s

superstructure

A superstructure is an upward extension of an existing structure above a baseline. This term is applied to various kinds of physical structures such as buildings, bridges, or ships.

Aboard ships and large boats

On water craft, the superstruct ...

was separated into three structures. This technically allowed both turrets to fire across the ship's deck (cross-deck fire), between the sections. This ability was limited as the superstructure restricted each turret's arc of fire.

This plan and profile view show ''Maine'' with eight six-pounder guns (one is not seen on the port part of the bridge but that is due to the bridge being cut away in the drawing). Another early published plan shows the same. In both cases the photographs show a single extreme bow mounted six-pounder. Careful examination of ''Maine'' photographs confirms that she did not carry that gun. ''Maine''s armament set up in the bow was not identical to the stern which had a single six-pounder mounted at extreme aft of the vessel. ''Maine'' carried two six-pounders forward, two on the bridge and three on the stern section, all one level above the abbreviated gun deck that permitted the ten-inch guns to fire across the deck. The six-pounders located in the bow were positioned more forward than the pair mounted aft which necessitated the far aft single six-pounder.

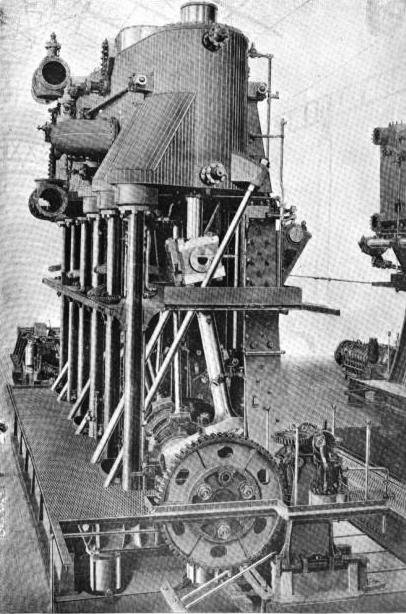

Propulsion

''Maine'' was the first U.S. capital ship to have its power plant given as high a priority as its fighting strength. Her machinery, built by the N. F. Palmer Jr. & Company's Quintard Iron Works of New York, was the first designed for a major ship under the direct supervision of Arctic explorer and soon-to-be

commodore

Commodore may refer to:

Ranks

* Commodore (rank), a naval rank

** Commodore (Royal Navy), in the United Kingdom

** Commodore (United States)

** Commodore (Canada)

** Commodore (Finland)

** Commodore (Germany) or ''Kommodore''

* Air commodore ...

,

George Wallace Melville

George Wallace Melville (January 10, 1841 – March 17, 1912) was an American engineer, Arctic explorer, and author. As chief of the Bureau of Steam Engineering, he headed a time of great expansion, technological progress and change, often ...

. She had two inverted

vertical triple-expansion steam engines, mounted in watertight compartments and separated by a fore-to-aft bulkhead, with a total designed output of . Cylinder diameters were (high-pressure), (intermediate-pressure) and (low-pressure). Stroke for all three pistons was .

Melville mounted ''Maine''s engines with the cylinders in vertical mode, a departure from conventional practice. Previous ships had had their engines mounted in horizontal mode, so that they would be completely protected below the waterline. Melville believed a ship's engines needed ample room to operate and that any exposed parts could be protected by an armored deck. He therefore opted for the greater efficiency, lower maintenance costs and higher speeds offered by the vertical mode.

Also, the engines were constructed with the high-pressure cylinder aft and the low-pressure cylinder forward. This was done, according to the ship's chief engineer, A. W. Morley, so the low-pressure cylinder could be disconnected when the ship was under low power. This allowed the high and intermediate-power cylinders to be run together as a

compound engine

A compound engine is an engine that has more than one stage for recovering energy from the same working fluid, with the exhaust from the first stage passing through the second stage, and in some cases then on to another subsequent stage or even st ...

for economical running.

Eight single-ended

Scotch marine boilers provided steam to the engines at a working pressure of at a temperature . On trials, she reached a speed of , failing to meet her contract speed of . She carried a maximum load of of coal in 20 bunkers, 10 on each side, which extended below the protective deck. Wing bunkers at each end of each fire room extended inboard to the front of the boilers. This was a very low capacity for a ship of ''Maine''s rating, which limited her time at sea and her ability to run at

flank speed, when coal consumption increased dramatically. ''Maine''s overhanging main turrets also prevented coaling at sea, except in the calmest of waters; otherwise, the potential for damage to a

collier, herself or both vessels was extremely great.

''Maine'' also carried two small

dynamo

"Dynamo Electric Machine" (end view, partly section, )

A dynamo is an electrical generator that creates direct current using a commutator. Dynamos were the first electrical generators capable of delivering power for industry, and the foundati ...

s to power her searchlights and provide interior lighting.

''Maine'' was designed initially with a three-mast

barque

A barque, barc, or bark is a type of sailing vessel with three or more masts having the fore- and mainmasts rigged square and only the mizzen (the aftmost mast) rigged fore and aft. Sometimes, the mizzen is only partly fore-and-aft rigged, b ...

rig for auxiliary propulsion, in case of engine failure and to aid long-range cruising. This arrangement was limited to "two-thirds" of full sail power, determined by the ship's tonnage and immersed cross-section. The mizzen

mast

Mast, MAST or MASt may refer to:

Engineering

* Mast (sailing), a vertical spar on a sailing ship

* Flagmast, a pole for flying a flag

* Guyed mast, a structure supported by guy-wires

* Mooring mast, a structure for docking an airship

* Radio mas ...

was removed in 1892, after the ship had been launched, but before her completion. ''Maine'' was completed with a two-mast military rig and the ship never spread any canvas.

Armament

Main guns

''Maine''s main armament consisted of four

/30 caliber

In guns, particularly firearms, caliber (or calibre; sometimes abbreviated as "cal") is the specified nominal internal diameter of the gun barrel bore – regardless of how or where the bore is measured and whether the finished bore matc ...

Mark II guns, which had a maximum elevation of 15° and could depress to −3°. Ninety rounds per gun were carried. The ten-inch guns fired a shell at a

muzzle velocity

Muzzle velocity is the speed of a projectile ( bullet, pellet, slug, ball/ shots or shell) with respect to the muzzle at the moment it leaves the end of a gun's barrel (i.e. the muzzle). Firearm muzzle velocities range from approximately ...

of to a range of at maximum elevation. These guns were mounted in twin hydraulically powered Mark 3 turrets, the fore turret sponsoned to starboard and the aft turret sponsoned to port.

The 10" guns were initially to be mounted in open

barbette

Barbettes are several types of gun emplacement in terrestrial fortifications or on naval ships.

In recent naval usage, a barbette is a protective circular armour support for a heavy gun turret. This evolved from earlier forms of gun protectio ...

s (the C & R proposal blueprint shows them as such). During ''Maine''s extended construction, the development of rapid-fire intermediate-caliber guns, which could fire high-explosive shells, became a serious threat and the navy redesigned ''Maine'' with enclosed turrets. Because of the corresponding weight increase, the turrets were mounted one deck lower than planned originally. Even with this modification, the main guns were high enough to fire unobstructed for 180° on one side and 64° on the other side. They could also be loaded at any angle of train; initially the main guns of ''Texas'', by comparison, with external rammers, could be loaded only when trained on the centerline or directly abeam, a common feature in battleships built before 1890. By 1897, ''Texas'' turrets had been modified with internal rammers to permit much faster reloading.

The ''en echelon'' arrangement proved problematic. Because ''Maine''s turrets were not counterbalanced, she heeled over if both were pointed in the same direction, which reduced the range of the guns. Also, cross-deck firing damaged her deck and superstructure significantly due to the vacuum from passing shells.

Because of this, and the potential for undue hull stress if the main guns were fired end-on, the ''en echelon'' arrangement was not used in U.S. Navy designs after ''Maine'' and ''Texas''.

Secondary and light guns

The six

/30 caliber Mark 3 guns were mounted in

casemate

A casemate is a fortified gun emplacement or armored structure from which guns are fired, in a fortification, warship, or armoured fighting vehicle.Webster's New Collegiate Dictionary

When referring to antiquity, the term "casemate wall" me ...

s in the hull, two each at the bow and stern and the last two amidships. Data is lacking, but they could probably depress to −7° and elevate to +12°. They fired shells that weighed with a muzzle velocity of about . They had a maximum range of at full elevation.

The anti-torpedo boat armament consisted of seven

Driggs-Schroeder six-pounder guns mounted on the superstructure deck. They fired a shell weighing about at a muzzle velocity of about at a rate of 20 rounds per minute to a maximum range of . The lighter armament comprised four each

Hotchkiss

Hotchkiss may refer to:

Places Canada

* Hotchkiss, Alberta

* Hotchkiss, Calgary

United States

* Hotchkiss, Colorado

* Hotchkiss, Virginia

* Hotchkiss, West Virginia

Business and industry

* Hotchkiss (car), a French automobile manufacturer ...

and Driggs-Schroeder one-pounder guns. Four of these were mounted on the superstructure deck, two were mounted in small casemates at the extreme stern and one was mounted in each

fighting top

The top on a traditional square rigged ship, is the platform at the upper end of each (lower) mast. This is not the masthead "crow's nest" of the popular imagination – above the mainmast (for example) is the main-topmast, main-topgallant-mast a ...

. They fired a shell weighing about at a muzzle velocity of about at a rate of 30 rounds per minute to a range about .

''Maine'' had four above-water

torpedo tube

A torpedo tube is a cylindrical device for launching torpedoes.

There are two main types of torpedo tube: underwater tubes fitted to submarines and some surface ships, and deck-mounted units (also referred to as torpedo launchers) installed aboa ...

s, two on each broadside. In addition, she was designed to carry two steam-powered torpedo boats, each with a single torpedo tube and a one-pounder gun. Only one was built, but it had a top speed of only a little over so it was transferred to the

Naval Torpedo Station

The Naval Undersea Warfare Center (NUWC) is the United States Navy's full-spectrum research, development, test and evaluation, engineering and fleet support center for submarines, autonomous underwater systems, and offensive and defensive weapons ...

at

Newport, Rhode Island

Newport is an American seaside city on Aquidneck Island in Newport County, Rhode Island. It is located in Narragansett Bay, approximately southeast of Providence, south of Fall River, Massachusetts, south of Boston, and northeast of New Yor ...

, as a training craft.

Armor

The main waterline

belt

Belt may refer to:

Apparel

* Belt (clothing), a leather or fabric band worn around the waist

* Championship belt, a type of trophy used primarily in combat sports

* Colored belts, such as a black belt or red belt, worn by martial arts practiti ...

, made of nickel steel, had a maximum thickness of and tapered to at its lower edge. It was long and covered the machinery spaces and the 10-inch

magazines

A magazine is a periodical publication, generally published on a regular schedule (often weekly or monthly), containing a variety of content. They are generally financed by advertising, purchase price, prepaid subscriptions, or by a combination ...

. It was high, of which was above the design waterline. It angled inwards for at each end, thinning to , to provide protection against

raking fire

In naval warfare during the Age of Sail, raking fire was cannon fire directed parallel to the long axis of an enemy ship from ahead (in front of the ship) or astern (behind the ship). Although each shot was directed against a smaller profile ...

. A 6-inch transverse bulkhead closed off the forward end of the

armored citadel

In a warship an armored citadel is an armored box enclosing the machinery and magazine spaces formed by the armored deck, the waterline belt

Belt may refer to:

Apparel

* Belt (clothing), a leather or fabric band worn around the waist

* C ...

. The forward portion of the protective deck ran from the bulkhead all the way to the bow and served to stiffen the ram. The deck sloped downwards to the sides, but its thickness increased to . The rear portion of the protective deck sloped downwards towards the stern, going below the waterline, to protect the propeller shafts and steering gear. The sides of the circular

turrets

Turret may refer to:

* Turret (architecture), a small tower that projects above the wall of a building

* Gun turret, a mechanism of a projectile-firing weapon

* Objective turret, an indexable holder of multiple lenses in an optical microscope

* M ...

were 8 inches thick. The barbettes were 12 inches thick, with their lower portions reduced to 10 inches. The

conning tower

A conning tower is a raised platform on a ship or submarine, often armored, from which an officer in charge can conn the vessel, controlling movements of the ship by giving orders to those responsible for the ship's engine, rudder, lines, and gro ...

had 10-inch walls. The ship's

voicepipes and electrical leads were protected by an armored tube thick.

Two flaws emerged in ''Maine''s protection, both due to technological developments between her laying-down and her completion. The first was a lack of adequate topside armor to counter the effects of rapid-fire intermediate-caliber guns and high-explosive shells. This was a flaw she shared with ''Texas''.

[Morrison, p. 17.] The second was the use of nickel-steel armor. Introduced in 1889, nickel steel was the first modern steel

alloy

An alloy is a mixture of chemical elements of which at least one is a metal. Unlike chemical compounds with metallic bases, an alloy will retain all the properties of a metal in the resulting material, such as electrical conductivity, ductili ...

armor and, with a

figure of merit

A figure of merit is a quantity used to characterize the performance of a device, system or method, relative to its alternatives. Examples

*Clock rate of a CPU

*Calories per serving

*Contrast ratio of an LCD

*Frequency response of a speaker

* Fi ...

of 0.67, was an improvement over the 0.6 rating of

mild steel

Carbon steel is a steel with carbon content from about 0.05 up to 2.1 percent by weight. The definition of carbon steel from the American Iron and Steel Institute (AISI) states:

* no minimum content is specified or required for chromium, cobal ...

used until then. Harvey steel and

Krupp armors, both of which appeared in 1893, had merit figures of between 0.9 and 1.2, giving them roughly twice the tensile strength of nickel steel. Although all three armors shared the same density (about 40 pounds per square foot for a one-inch-thick plate), six inches of Krupp or Harvey steel gave the same protection as 10 inches of nickel. The weight thus saved could be applied either to additional hull structure and machinery or to achieving higher speed. The navy would incorporate Harvey armor in the s, designed after ''Maine'', but commissioned at roughly the same time.

Launching and delay

''Maine'' was launched on 18 November 1889, sponsored by Alice Tracey Wilmerding, the granddaughter of Navy Secretary

Benjamin F. Tracy

Benjamin Franklin Tracy (April 26, 1830August 6, 1915) was a United States political figure who served as Secretary of the Navy from 1889 through 1893, during the administration of U.S. President Benjamin Harrison.

Biography

He was born in th ...

. Not long afterwards, a reporter wrote for ''Marine Engineer and Naval Architect'' magazine, "it cannot be denied that the navy of the United States is making rapid strides towards taking a credible position among the navies of the world, and the launch of the new armoured battleship ''Maine'' from the Brooklyn Navy Yard ... has added a most powerful unit to the United States fleet of turret ships."

In his 1890 annual report to congress, the Secretary of the Navy wrote, "the ''Maine'' ... stands in a class by herself" and expected the ship to be

commissioned by July 1892.

A three-year delay ensued, while the shipyard waited for nickel steel plates for ''Maine''s armor.

Bethlehem Steel

The Bethlehem Steel Corporation was an American steelmaking company headquartered in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. For most of the 20th century, it was one of the world's largest steel producing and shipbuilding companies. At the height of its succ ...

had promised the navy 300 tons per month by December 1889 and had ordered heavy

casting

Casting is a manufacturing process in which a liquid material is usually poured into a mold, which contains a hollow cavity of the desired shape, and then allowed to solidify. The solidified part is also known as a ''casting'', which is ejecte ...

s and

forging press

Forging is a manufacturing process involving the shaping of metal using localized compressive forces. The blows are delivered with a hammer (often a power hammer) or a die. Forging is often classified according to the temperature at which ...

es from the British firm of

Armstrong Whitworth

Sir W G Armstrong Whitworth & Co Ltd was a major British manufacturing company of the early years of the 20th century. With headquarters in Elswick, Newcastle upon Tyne, Armstrong Whitworth built armaments, ships, locomotives, automobiles and ...

in 1886 to fulfil its contract. This equipment did not arrive until 1889, pushing back Bethlehem's timetable. In response, Navy Secretary Benjamin Tracy secured a second contractor, the newly expanded

Homestead mill of Carnegie, Phipps & Company. In November 1890, Tracy and

Andrew Carnegie

Andrew Carnegie (, ; November 25, 1835August 11, 1919) was a Scottish-American industrialist and philanthropist. Carnegie led the expansion of the American steel industry in the late 19th century and became one of the richest Americans in ...

signed a contract for Homestead to supply 6000 tons of nickel steel. Homestead was, what author Paul Krause calls, "the last union stronghold in the steel mills of the Pittsburgh district." The mill had already weathered one strike in 1882 and a lockout in 1889 in an effort to break the union there. Less than two years later, came the

Homestead Strike

The Homestead strike, also known as the Homestead steel strike, Homestead massacre, or Battle of Homestead, was an industrial lockout and strike that began on July 1, 1892, culminating in a battle in which strikers defeated private security age ...

of 1892, one of the largest, most serious disputes in

U.S. labor history.

A photo of the christening shows Mrs. Wilmerding striking the bow near the plimsoll line depth of 13 which lead to many comments (much later of course) that the ship was "unlucky" from the launching.

Operations

''Maine'' was commissioned on 17 September 1895, under the command of Captain

Arent S. Crowninshield

Arent Schuyler Crowninshield (March 14, 1843 – May 27, 1908) was a rear admiral of the United States Navy. He saw combat during the Civil War, and after the war held high commands both afloat and ashore.

Early life

Born in New York, he was the ...

. On 5 November 1895, ''Maine'' steamed to

Sandy Hook Bay

The Raritan Bayshore region of New Jersey is a subregion of the larger Jersey Shore. It is the area around Raritan Bay from The Amboys to Sandy Hook, in Monmouth and Middlesex counties, including the towns of Woodbridge, Perth Amboy, South Amboy, ...

,

New Jersey

New Jersey is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern regions of the United States. It is bordered on the north and east by the state of New York; on the east, southeast, and south by the Atlantic Ocean; on the west by the Delawa ...

. She anchored there two days, then proceeded to Newport, Rhode Island, for fitting out and test firing of her torpedoes. After a trip, later that month, to

Portland, Maine

Portland is the largest city in the U.S. state of Maine and the seat of Cumberland County. Portland's population was 68,408 in April 2020. The Greater Portland metropolitan area is home to over half a million people, the 104th-largest metropo ...

, she reported to the

North Atlantic Squadron

The North Atlantic Squadron was a section of the United States Navy operating in the North Atlantic. It was renamed as the North Atlantic Fleet in 1902. In 1905 the European and South Atlantic squadrons were abolished and absorbed into the Nort ...

for operations, training maneuvers and fleet exercises. ''Maine'' spent her active career with the North Atlantic Squadron, operating from

Norfolk, Virginia

Norfolk ( ) is an independent city in the Commonwealth of Virginia in the United States. Incorporated in 1705, it had a population of 238,005 at the 2020 census, making it the third-most populous city in Virginia after neighboring Virginia B ...

along the

East Coast of the United States

The East Coast of the United States, also known as the Eastern Seaboard, the Atlantic Coast, and the Atlantic Seaboard, is the coastline along which the Eastern United States meets the North Atlantic Ocean. The eastern seaboard contains the coa ...

and the

Caribbean

The Caribbean (, ) ( es, El Caribe; french: la Caraïbe; ht, Karayib; nl, De Caraïben) is a region of the Americas that consists of the Caribbean Sea, its islands (some surrounded by the Caribbean Sea and some bordering both the Caribbean ...

. On 10 April 1897, Captain

Charles Dwight Sigsbee relieved Captain Crowninshield as commander of ''Maine''.

Sinking

In January 1898, ''Maine'' was sent from

Key West, Florida

Key West ( es, Cayo Hueso) is an island in the Straits of Florida, within the U.S. state of Florida. Together with all or parts of the separate islands of Sigsbee Park, Dredgers Key, Fleming Key, Sunset Key, and the northern part of Stock Isla ...

, to

Havana

Havana (; Spanish: ''La Habana'' ) is the capital and largest city of Cuba. The heart of the La Habana Province, Havana is the country's main port and commercial center. , Cuba, to protect U.S. interests during the

Cuban War of Independence

The Cuban War of Independence (), fought from 1895 to 1898, was the last of three liberation wars that Cuba fought against Spain, the other two being the Ten Years' War (1868–1878) and the Little War (1879–1880). The final three months ...

. She arrived at 11:00 local time on January 25. Three weeks later, at 21:40, on 15 February, an explosion on board ''Maine'' occurred in the Havana Harbor (). Later investigations revealed that more than of powder charges for the vessel's six- and ten-inch guns had detonated, obliterating the forward third of the ship. The remaining wreckage rapidly settled to the bottom of the harbor.

Most of ''Maine''s crew were sleeping or resting in the enlisted quarters, in the forward part of the ship, when the explosion occurred. The 1898 US Navy Surgeon General Reported that the ship's crew consisted of 355: 26 officers, 290 enlisted sailors, and 39 marines. Of these, there were 261 fatalities:

* Two officers and 251 enlisted sailors and marines either killed by the explosion or drowned

* Seven others were rescued but soon died of their injuries

* One officer later died of "cerebral affection" (shock)

* Of the 94 survivors, 16 were uninjured. In total, 260

men lost their lives as a result of the explosion or shortly thereafter, and six more died later from injuries.

Captain Sigsbee and most of the officers survived, because their quarters were in the aft portion of the ship. Altogether there were 89 survivors, 18 of whom were officers. The ''

City of Washington'', an American merchant steamship, aided in rescuing the crew.

The cause of the accident was immediately debated. Waking up President McKinley to break the news, Commander Francis W. Dickins referred to it as an "accident". Commodore

George Dewey

George Dewey (December 26, 1837January 16, 1917) was Admiral of the Navy, the only person in United States history to have attained that rank. He is best known for his victory at the Battle of Manila Bay during the Spanish–American War, with ...

, Commander of the

Asiatic Squadron

The Asiatic Squadron was a squadron of United States Navy warships stationed in East Asia during the latter half of the 19th century. It was created in 1868 when the East India Squadron was disbanded. Vessels of the squadron were primarily inv ...

, "feared at first that she had been destroyed by the Spanish, which of course meant war, and I was getting ready for it when a later dispatch said it was an accident." Navy Captain Philip R. Alger, an expert on ordnance and explosives, posted a bulletin at the Navy Department the next day saying that the explosion had been caused by a spontaneous fire in the coal bunkers.

Assistant Navy Secretary

Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

wrote a letter protesting this statement, which he viewed as premature. Roosevelt argued that Alger should not have commented on an ongoing investigation, saying, "Mr. Alger cannot possibly know anything about the accident. All the best men in the Department agree that, whether probable or not, it certainly is possible that the ship was blown up by a mine."

Yellow journalism

The ''

New York Journal

:''Includes coverage of New York Journal-American and its predecessors New York Journal, The Journal, New York American and New York Evening Journal''

The ''New York Journal-American'' was a daily newspaper published in New York City from 1937 t ...

'' and ''

New York World

The ''New York World'' was a newspaper published in New York City from 1860 until 1931. The paper played a major role in the history of American newspapers. It was a leading national voice of the Democratic Party. From 1883 to 1911 under pub ...

'', owned respectively by

William Randolph Hearst

William Randolph Hearst Sr. (; April 29, 1863 – August 14, 1951) was an American businessman, newspaper publisher, and politician known for developing the nation's largest newspaper chain and media company, Hearst Communications. His flamboya ...

and

Joseph Pulitzer

Joseph Pulitzer ( ; born Pulitzer József, ; April 10, 1847 – October 29, 1911) was a Hungarian-American politician and newspaper publisher of the '' St. Louis Post-Dispatch'' and the ''New York World''. He became a leading national figure in ...

, gave ''Maine'' intense press coverage, employing tactics that would later be labeled "

yellow journalism

Yellow journalism and yellow press are American terms for journalism and associated newspapers that present little or no legitimate, well-researched news while instead using eye-catching headlines for increased sales. Techniques may include ...

". Both papers exaggerated and distorted any information they could obtain, sometimes even fabricating news when none that fitted their agenda was available. For a week following the sinking, the ''Journal'' devoted a daily average of eight and a half pages of news, editorials and pictures to the event. Its editors sent a full team of reporters and artists to Havana, including

Frederic Remington

Frederic Sackrider Remington (October 4, 1861 – December 26, 1909) was an American painter, illustrator, sculptor, and writer who specialized in the genre of Western American Art. His works are known for depicting the Western United Sta ...

, and Hearst announced a reward of $50,000 "for the conviction of the criminals who sent 258 American sailors to their deaths."

The ''World,'' while overall not as lurid or shrill in tone as the ''Journal,'' nevertheless indulged in similar theatrics, insisting continually that ''Maine'' had been bombed or mined. Privately, Pulitzer believed that "nobody outside a lunatic asylum" really believed that Spain sanctioned ''Maine''s destruction. Nevertheless, this did not stop the ''World'' from insisting that the only "atonement" Spain could offer the U.S. for the loss of ship and life, was the granting of complete Cuban independence. Nor did it stop the paper from accusing Spain of "treachery, willingness, or laxness" for failing to ensure the safety of Havana Harbor. The American public, already agitated over reported Spanish atrocities in Cuba, was driven to increased hysteria.

William Randolph Hearst's reporting on ''Maine'' whipped up support for military action against the Spanish in Cuba regardless of their actual involvement in the sinking. He frequently cited various naval officers saying that the explosion could not have been an on-board accident. He quoted an "officer high in authority" as saying "The idea that the catastrophe resulted from an internal accident is preposterous. In the first place, such a thing has never occurred before that I have ever heard of either in the British navy or ours."

Spanish–American War

''Maine''s destruction did not result in an immediate declaration of war with Spain, but the event created an atmosphere that precluded a peaceful solution. The

Spanish investigation found that the explosion had been caused by spontaneous combustion of the coal bunkers, but the

Sampson Board ruled that the explosion had been caused by an external explosion from a torpedo.

The episode focused national attention on the crisis in Cuba. The

McKinley administration did not cite the explosion as a ''

casus belli

A (; ) is an act or an event that either provokes or is used to justify a war. A ''casus belli'' involves direct offenses or threats against the nation declaring the war, whereas a ' involves offenses or threats against its ally—usually one ...

'', but others were already inclined to go to war with Spain over perceived atrocities and loss of control in Cuba.

Advocates of war used the rallying cry, "Remember the ''Maine!'' To hell with Spain!"

The Spanish–American War began on April 21, 1898, two months after the sinking.

Investigations

In addition to the inquiry commissioned by the Spanish government to naval officers Del Peral and De Salas, two Naval Courts of Inquiry were ordered: The Sampson Board in 1898 and the Vreeland board in 1911. In 1976, Admiral

Hyman G. Rickover commissioned a private investigation into the explosion, and the

National Geographic Society

The National Geographic Society (NGS), headquartered in Washington, D.C., United States, is one of the largest non-profit scientific and educational organizations in the world.

Founded in 1888, its interests include geography, archaeology, ...

did an investigation in 1998, using computer simulations. All investigations agreed that an explosion of the forward magazines caused the destruction of the ship, but different conclusions were reached as to how the magazines could have exploded.

1898 Del Peral and De Salas inquiry

The Spanish inquiry, conducted by Del Peral and De Salas, collected evidence from officers of naval artillery, who had examined the remains of the ''Maine''. Del Peral and De Salas identified the spontaneous combustion of the coal bunker, located adjacent to the munition stores in ''Maine'', as the likely cause of the explosion. The possibility that other combustibles, such as varnish, drier, or alcohol products, had caused the explosion was not discounted. Additional observations included that:

* Had a mine been the cause of the explosion, a column of water would have been observed.

* The wind and the waters were calm on that date and hence a mine could not have been detonated by contact, but only by using electricity, but no cables had been found.

* No dead fish were found in the harbor, as would be expected following an explosion in the water.

* Munition stores do not usually explode when a ship is sunk by a mine.

The conclusions of the report were not reported at that time by the American press.

1898 Sampson Board's Court of Inquiry

In order to find the cause of the explosion, a naval inquiry was ordered by the United States shortly after the incident, headed by Captain

William T. Sampson.

Ramón Blanco y Erenas, Spanish governor of Cuba, had proposed instead a joint Spanish-American investigation of the sinking. Captain Sigsbee had written that "many Spanish officers, including representatives of General Blanco, now with us to express sympathy." In a cable, the Spanish minister of colonies,

Segismundo Moret

Segismundo Moret y Prendergast (2 June 1833 – 28 January 1913) was a Spanish politician and writer. He was the prime minister of Spain on three occasions and the president of the Congress of Deputies on two occasions.

Biography

Moret was bo ...

, had advised Blanco "to gather every fact you can, to prove the ''Maine'' catastrophe cannot be attributed to us."

According to Dana Wegner, who worked with Rickover on his 1974 investigation of the sinking, the Secretary of the Navy had the option of selecting a board of inquiry personally. Instead, he fell back on protocol and assigned the commander-in-chief of the North Atlantic Squadron to do so. The commander produced a list of junior line officers for the board. The fact that the officer proposed to be court president was junior to the captain of ''Maine'', Wegner writes, "would indicate either ignorance of navy regulations or that, in the beginning, the board did not intend to examine the possibility that the ship was lost by accident and the negligence of her captain." Eventually, navy regulations prevailed in leadership of the board, Captain Sampson being senior to Captain Sigsbee.

The board arrived on 21 February and took testimony from survivors, witnesses, and divers (who were sent down to investigate the wreck). The Sampson Board produced its findings in two parts: the proceedings, which consisted mainly of testimonies, and the findings, which were the facts, as determined by the court. Between the proceedings and the findings, there was what Wegner calls, "a broad gap," where the court "left no record of the reasoning that carried it from the often-inconsistent witnesses to

tsconclusion." Another inconsistency, according to Wegner, was that of only one technical witness, Commander George Converse, from the Torpedo Station at Newport, Rhode Island. Captain Sampson read Commander Converse a hypothetical situation of a coal bunker fire igniting the reserve six-inch ammunition, with a resulting explosion sinking the ship. He then asked Commander Converse about the feasibility of such a scenario. Commander Converse "simply stated, without elaboration, that he could not realize such an event happening."

The board concluded that ''Maine'' had been blown up by a mine, which, in turn, caused the explosion of her forward magazines. They reached this conclusion based on the fact that the majority of witnesses stated that they had heard two explosions and that part of the keel was bent inwards.

The official report from the board, which was presented to the

Navy Department in Washington on 21 March, specifically stated the following:

1911 Vreeland Board's Court of Inquiry

In 1910, the decision was made to have a second Court of Inquiry. Besides the desire for a more thorough investigation, this would also facilitate the recovery of the bodies of the victims, so they could be buried in the United States. The fact that the Cuban government wanted the wreck removed from Havana harbor might also have played a role: it at least offered the opportunity to examine the wreck in greater detail than had been possible in 1898, while simultaneously obliging the now-independent Cubans. Wegner suggests that the fact that this inquiry could be held without the threat of war, which had been the case in 1898, lent it the potential for greater objectivity than had been possible previously. Moreover, since several of the members of the 1910 board would be certified engineers, they would be better qualified to evaluate their findings than the line officers of the 1898 board had been.

Beginning in December 1910, a

cofferdam

A cofferdam is an enclosure built within a body of water to allow the enclosed area to be pumped out. This pumping creates a dry working environment so that the work can be carried out safely. Cofferdams are commonly used for construction or re ...

was built around the wreck and water was pumped out, exposing the wreck by late 1911. Between 20 November and 2 December 1911, a court of inquiry headed by Rear Admiral

Charles E. Vreeland inspected the wreck. They concluded that an external explosion had triggered the explosion of the magazines. This explosion was farther aft and lower powered than concluded by the Sampson Board. The Vreeland Board also found that the bending of frame 18 was caused by the explosion of the magazines, not by the external explosion.

After the investigation, the newly located dead were buried in

Arlington National Cemetery

Arlington National Cemetery is one of two national cemeteries run by the United States Army. Nearly 400,000 people are buried in its 639 acres (259 ha) in Arlington, Virginia. There are about 30 funerals conducted on weekdays and 7 held on Sa ...

and the hollow, intact portion of the hull of ''Maine'' was refloated and ceremoniously scuttled at sea on 16 March 1912.

1974 Rickover investigation

Rickover became intrigued with the disaster and began a private investigation in 1974, using information from the two official inquiries, newspapers, personal papers, and information on the construction and ammunition of ''Maine''. He concluded that the explosion was not caused by a mine, and speculated that spontaneous combustion was the most likely cause, from coal in the bunker next to the magazine. He published a book about this investigation in 1976 entitled ''How the Battleship ''Maine'' Was Destroyed''.

In the 2001 book ''Theodore Roosevelt, the U.S. Navy and the Spanish–American War'', Wegner revisits the Rickover investigation and offers additional details. According to Wegner, Rickover interviewed naval historians at the Energy Research and Development Agency after reading an article in the ''

Washington Star-News

''The Washington Star'', previously known as the ''Washington Star-News'' and the Washington ''Evening Star'', was a daily afternoon newspaper published in Washington, D.C., between 1852 and 1981. The Sunday edition was known as the ''Sunday Star ...

'' by John M. Taylor. The author claimed that the U.S. Navy "made little use of its technically trained officers during its investigation of the tragedy." The historians were working with Rickover on a study of the Navy's nuclear propulsion program, but they said that they knew no details of ''Maine''s sinking. Rickover asked whether they could investigate the matter, and they agreed. Wegner says that all relevant documents were obtained and studied, including the ship's plans and weekly reports of the unwatering of ''Maine'' in 1912 (the progress of the cofferdam) written by William Furgueson, chief engineer for the project. These reports included numerous photos annotated by Furgueson with

frame and

strake numbers on corresponding parts of the wreckage. Two experts were brought in to analyze the naval demolitions and ship explosions. They concluded that the photos showed "no plausible evidence of penetration from the outside," and they believed that the explosion originated inside the ship.

Wegner suggests that a combination of naval ship design and a change in the type of coal used to fuel naval ships might have facilitated the explosion postulated by the Rickover study. Up to the time of the ''Maine''s building, he explains, common bulkheads separated coal bunkers from ammunition lockers, and American naval ships burned smokeless

anthracite

Anthracite, also known as hard coal, and black coal, is a hard, compact variety of coal that has a submetallic luster. It has the highest carbon content, the fewest impurities, and the highest energy density of all types of coal and is the hig ...

coal. With an increase in the number of steel ships, the Navy switched to

bituminous coal

Bituminous coal, or black coal, is a type of coal containing a tar-like substance called bitumen or asphalt. Its coloration can be black or sometimes dark brown; often there are well-defined bands of bright and dull material within the seams. It ...

, which burned at a hotter temperature than anthracite coal and allowed ships to steam faster. Wegner explains that anthracite coal is not subject to spontaneous combustion, but bituminous coal is considerably more volatile and is known for releasing the largest amounts of

firedamp, a dangerous and explosive mixture of gases (chiefly

methane

Methane ( , ) is a chemical compound with the chemical formula (one carbon atom bonded to four hydrogen atoms). It is a group-14 hydride, the simplest alkane, and the main constituent of natural gas. The relative abundance of methane ...

). Firedamp is explosive at concentrations between 4% and 16%, with most violence at around 10%. In addition, there was another potential contributing factor in the bituminous coal:

iron sulfide

Iron sulfide or Iron sulphide can refer to range of chemical compounds composed of iron and sulfur.

Minerals

By increasing order of stability:

* Iron(II) sulfide, FeS

* Greigite, Fe3S4 (cubic)

* Pyrrhotite, Fe1−xS (where x = 0 to 0.2) (mono ...

, also known as

pyrite

The mineral pyrite (), or iron pyrite, also known as fool's gold, is an iron sulfide with the chemical formula Iron, FeSulfur, S2 (iron (II) disulfide). Pyrite is the most abundant sulfide mineral.

Pyrite's metallic Luster (mineralogy), lust ...

, was likely present. The presence of pyrites presents two additional risk factors, the first involving

oxidation

Redox (reduction–oxidation, , ) is a type of chemical reaction in which the oxidation states of substrate change. Oxidation is the loss of electrons or an increase in the oxidation state, while reduction is the gain of electrons or ...

. Pyrite oxidation is sufficiently

exothermic

In thermodynamics, an exothermic process () is a thermodynamic process or reaction that releases energy from the system to its surroundings, usually in the form of heat, but also in a form of light (e.g. a spark, flame, or flash), electricity ...

that underground coal mines in high-sulfur coal seams have occasionally experienced spontaneous combustion in the mined-out areas of the mine. This process can result from the disruption caused by mining from the seams, which exposes the sulfides in the ore to air and water. The second risk factor involves an additional capability of pyrites to provide fire ignition under certain conditions. Pyrites derive their name from the Greek root word

pyr, meaning ''fire'', as they can cause sparks when struck by steel or other hard surfaces. Pyrites were used to strike sparks to ignite gunpowder in

wheellock

A wheellock, wheel-lock or wheel lock is a friction-wheel mechanism which creates a spark that causes a firearm to fire. It was the next major development in firearms technology after the matchlock and the first self-igniting firearm. Its name is ...

guns, for example. The pyrites could have provided the ignition capability needed to create an explosion. A number of bunker fires of this type had been reported aboard warships before the ''Maine''s explosion, in several cases nearly sinking the ships. Wegner also cites a 1997

heat transfer

Heat transfer is a discipline of thermal engineering that concerns the generation, use, conversion, and exchange of thermal energy ( heat) between physical systems. Heat transfer is classified into various mechanisms, such as thermal conducti ...

study which concluded that a coal bunker fire could have taken place and ignited the ship's ammunition.

1998 ''National Geographic'' investigation

In 1998, ''

National Geographic

''National Geographic'' (formerly the ''National Geographic Magazine'', sometimes branded as NAT GEO) is a popular American monthly magazine published by National Geographic Partners. Known for its photojournalism, it is one of the most widel ...

'' magazine commissioned an analysis by Advanced Marine Enterprises (AME). This investigation, done to commemorate the centennial of the sinking of USS ''Maine'', was based on computer modeling, a technique unavailable for previous investigations. The results reached were inconclusive. ''National Geographic'' reported that "a fire in the coal bunker could have generated sufficient heat to touch off an explosion in the adjacent magazine

uton the other hand, computer analysis also shows that even a small, handmade mine could have penetrated the ship's hull and set off explosions within." The AME investigation noted that "the size and location of the soil depression beneath the ''Maine'' 'is more readily explained by a mine explosion than by magazine explosions alone'."

The team noted that this was not "definitive in proving that a mine was the cause of the sinking" but it did "strengthen the case."

Some experts, including Rickover's team and several analysts at AME, do not agree with the conclusion.

Wegner claims that technical opinion among the ''Geographic'' team was divided between its younger members, who focused on computer modeling results, and its older ones, who weighed their inspection of photos of the wreck with their own experience. He adds that AME used flawed data concerning the ''Maine''s design and ammunition storage. Wegner was also critical of the fact that participants in the Rickover study were not consulted until AME's analysis was essentially complete, far too late to confirm the veracity of data being used or engage in any other meaningful cooperation.

2002 Discovery Channel ''Unsolved History'' investigation

In 2002, the

Discovery Channel

Discovery Channel (known as The Discovery Channel from 1985 to 1995, and often referred to as simply Discovery) is an American cable channel owned by Warner Bros. Discovery, a publicly traded company run by CEO David Zaslav. , Discovery Chan ...

produced an episode of the ''

Unsolved History

''Unsolved History'' is an American documentary television series that aired from 2002 to 2005. The program was produced by Termite Art Productions, Lions Gate Television, and Discovery Communications for the Discovery Channel. The series las ...

'' documentaries, entitled "Death of the U.S.S. ''Maine''." It used photographic evidence, naval experts, and archival information to argue that the cause of the explosion was a coal bunker fire, and it identified a weakness or gap in the bulkhead separating the coal and powder bunkers that allowed the fire to spread from the former to the latter.

False flag operation conspiracy theories

Several claims have been made in Spanish-speaking media that the sinking was a

false flag

A false flag operation is an act committed with the intent of disguising the actual source of responsibility and pinning blame on another party. The term "false flag" originated in the 16th century as an expression meaning an intentional misr ...

operation conducted by the U.S. and those claims are the official view in Cuba.

The

''Maine'' monument in Havana describes ''Maine''s sailors as "victims sacrificed to the imperialist greed in its fervor to seize control of Cuba," which claims that U.S. agents deliberately blew up their own ship.

Eliades Acosta was the head of the

Cuban Communist Party

The Communist Party of Cuba ( es, Partido Comunista de Cuba, PCC) is the sole ruling party of Cuba. It was founded on 3 October 1965 as the successor to the United Party of the Cuban Socialist Revolution, which was in turn made up of the 2 ...

's Committee on Culture and a former director of the José Martí National Library in Havana. He offered the standard Cuban interpretation in an interview to ''The New York Times'', but he adds that "Americans died for the freedom of Cuba, and that should be recognized."

This claim has also been made in Russia by Mikhail Khazin, a Russian economist who once ran the cultural section at

Komsomolskaya Pravda

''Komsomolskaya Pravda'' (russian: link=no, Комсомольская правда; lit. " Komsomol Truth") is a daily Russian tabloid newspaper, founded on 13 March 1925.

History and profile

During the Soviet era, ''Komsomolskaya Pravda'' w ...

, and in Spain by

Eric Frattini, a Spanish Peruvian journalist in his book ''Manipulando la historia. Operaciones de Falsa Bandera. Del Maine al Golpe de estado de Turquía''.

Operation Northwoods

Operation Northwoods was a proposed false flag operation against American citizens that originated within the US Department of Defense of the United States government in 1962. The proposals called for CIA operatives to both stage and actually co ...

was a series of proposals prepared by Pentagon officials for the Joint Chiefs of Staff in 1962, setting out a number of proposed false flag operations that could be blamed on the Cuban Communists in order to rally support against them.

One of these suggested that a U.S. Navy ship be blown up in Guantanamo Bay deliberately. In an echo of the yellow press headlines of the earlier period, it used the phrase "A 'Remember the ''Maine incident."

Raising and final sinking

For several years, the ''Maine'' was left where she sank in Havana harbor, but it was evident she would have to be removed sometime. It took up valuable space in the harbor, and the buildup of

silt

Silt is granular material of a size between sand and clay and composed mostly of broken grains of quartz. Silt may occur as a soil (often mixed with sand or clay) or as sediment mixed in suspension with water. Silt usually has a floury feel ...

around her hull threatened to create a

shoal

In oceanography, geomorphology, and geoscience, a shoal is a natural submerged ridge, bank, or bar that consists of, or is covered by, sand or other unconsolidated material and rises from the bed of a body of water to near the surface. It ...

. In addition, various patriotic groups wanted mementos of the ship. On 9 May 1910, Congress authorized funds for the removal of the ''Maine'', the proper interment in Arlington National Cemetery of the estimated 70 bodies still inside, and the removal and transport of the main mast to Arlington. Congress did not demand a new investigation into the sinking at that time.

The

Army Corps of Engineers built a cofferdam around the ''Maine'' and pumped water out from inside it.

By 30 June 1911, the ''Maine''s main deck was exposed. The ship forward of frame 41 was entirely destroyed; a twisted mass of steel out of line with the rest of the hull, all that was left of the bow, bore no resemblance to a ship. The rest of the wreck was badly corroded. Army engineers dismantled the damaged superstructure and decks, which were then dumped at sea. About halfway between bow and stern, they built a concrete and wooden bulkhead to seal the after-section, then cut away what was left of the forward portion. Holes were cut in the bottom of the after-section, through which jets of water were pumped, to break the mud seal holding the ship, then plugged, with flood cocks, which would later be used for sinking the ship.

The ''Maine'' had been outfitted with

Worthington steam pumps. After lying on the bottom of Havana harbor for fourteen years these pumps were found to be still operational, and were subsequently used to raise the ship.

On 13 February 1912, the engineers let water back into the interior of the cofferdam. Three days later, the interior of the cofferdam was full and ''Maine'' floated. Two days after that, the ''Maine'' was towed out by the tug . The bodies of its crew were then removed to the armored cruiser for repatriation. During the salvage, the remains of 66 men were found, of whom only one, Harry J. Keys (an engineering officer), was identified and returned to his home town; the rest were reburied at Arlington National Cemetery, making a total of 229 ''Maine'' crew buried there.

On 16 March, the ''Maine'' was towed four miles from the Cuban coast by ''Osceola'', escorted by ''North Carolina'' and the

light cruiser

A light cruiser is a type of small or medium-sized warship. The term is a shortening of the phrase "light armored cruiser", describing a small ship that carried armor in the same way as an armored cruiser: a protective belt and deck. Prior to th ...

. She was loaded with dynamite as a possible aid to her sinking.

Flowers adorned ''Maines deck, and an American flag was strung from her jury mast.

At 5pm local time, with a crowd of over 100,000 persons watching from the shore, her

sea cock

A seacock is a valve on the hull of a boat or a ship, permitting water to flow into the vessel, such as for cooling an engine or for a salt water faucet; or out of the boat, such as for a sink drain or a toilet. Seacocks are often a Kingston val ...

s were opened, and just over twenty minutes later, ''Maine'' sank, bow first, in of water, to the sound of

Taps and the

twenty-one gun salutes of ''Birmingham'' and ''North Carolina''.

Rediscovery

In 2000, the wreck of ''Maine'' was rediscovered by Advanced Digital Communications, a

Toronto

Toronto ( ; or ) is the capital city of the Canadian province of Ontario. With a recorded population of 2,794,356 in 2021, it is the most populous city in Canada and the fourth most populous city in North America. The city is the anch ...

-based expedition company, in about 3,770 feet (1,150 m) of water roughly 3 miles (4.8 km) northeast of Havana Harbor. The company had been working with Cuban scientists and oceanographers from the

University of South Florida

The University of South Florida (USF) is a public research university with its main campus located in Tampa, Florida, and other campuses in St. Petersburg and Sarasota. It is one of 12 members of the State University System of Florida. USF i ...

College of Marine Science, on testing underwater exploration technology. The ship had been discovered east of where it was believed it had been scuttled; according to the researchers, during the sinking ceremony and the time it took the wreck to founder, currents pushed ''Maine'' east until it came to rest at its present location. Before the team identified the site as ''Maine'', they referred to the location as the "square" due to its unique shape, and at first they did not believe it was the ship, due to its unexpected location. The site was explored with a

Remotely operated underwater vehicle

A remotely operated underwater vehicle (technically ROUV or just ROV) is a tethered underwater mobile device, commonly called ''underwater robot''.

Definition

This meaning is different from remote control vehicles operating on land or in the a ...

(ROV). According to Dr. Frank Muller-Karger, the hull was not oxidized and the crew could "see all of its structural parts."

[ The expedition was able to identify the ship due to the doors and hatches on the wreck, as well as the anchor chain, the shape of the propellers, and the holes where the bow was cut off. Due to the 1912 raising of the ship, the wreck was completely missing its bow; this tell-tale feature was instrumental in identifying the ship. The team also located a boiler nearby, and a debris field of coal.][Alt URL]

The wreck lay capsized onto its port side, buried deeply in the mud on the seafloor - all the way up to halfway up the starboard propeller.

Memorials

Arlington, Annapolis, Havana, Key West

In February 1898, the recovered bodies of sailors who died on ''Maine'' were interred in the Colon Cemetery, Havana

El Cementerio de Cristóbal Colón, also called La Necrópolis de Cristóbal Colón, was founded in 1876 in the Vedado neighbourhood of Havana, Cuba to replace the Espada Cemetery in the Barrio de San Lázaro. Named for Christopher Columbus, ...

. Some injured sailors were sent to hospitals in Havana and Key West, Florida. Those who died in hospitals were buried in Key West. In December 1899, the bodies in Havana were disinterred and brought back to the United States for burial at Arlington National Cemetery. In 1915, President Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was an American politician and academic who served as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. A member of the Democratic Party, Wilson served as the president of ...

dedicated the USS ''Maine'' Mast Memorial to those who died. The memorial includes the ship's main mast. Roughly 165 were buried at Arlington, although the remains of one sailor were exhumed for his home town, Indianapolis, Indiana

Indianapolis (), colloquially known as Indy, is the state capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Indiana and the seat of Marion County. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the consolidated population of Indianapolis and Mar ...

. Of the rest, only 62 were known.United States Naval Academy

The United States Naval Academy (US Naval Academy, USNA, or Navy) is a federal service academy in Annapolis, Maryland. It was established on 10 October 1845 during the tenure of George Bancroft as Secretary of the Navy. The Naval Academy ...

, Annapolis, Maryland

Annapolis ( ) is the capital city of the U.S. state of Maryland and the county seat of, and only incorporated city in, Anne Arundel County. Situated on the Chesapeake Bay at the mouth of the Severn River, south of Baltimore and about east ...

File:USS Maine Mast.jpg, Memorial at Arlington National Cemetery centered on the ship's main mast

File:CubanFriendshipUrnWashingtonDC.jpg, The Cuban Friendship Urn on Ohio Drive, Southwest, Washington, D.C.

Southwest (SW or S.W.) is the southwestern quadrant of Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States, and is located south of the National Mall and west of South Capitol Street. It is the smallest quadrant of the city, and contains a small n ...

, East Potomac Park

East Potomac Park is a park located on a man-made island in the Potomac River in Washington, D.C., United States. The island is between the Washington Channel and the Potomac River, and on it the park lies southeast of the Jefferson Memorial and t ...

File:MaineMonument1200.jpg, Monument to victims of ''Maine'' in Havana, Cuba, c. 1930

File:Gun recovered from the USS Maine.jpg, A 6-inch gun from ''Maine'' at Fort Allen Park in Portland, Maine

Portland is the largest city in the U.S. state of Maine and the seat of Cumberland County. Portland's population was 68,408 in April 2020. The Greater Portland metropolitan area is home to over half a million people, the 104th-largest metropo ...

File:U.S. Battleship Maine Monument Key West Cemetery, Florida.jpg, U.S. Battleship ''Maine'' Monument Key West Cemetery, Florida

The explosion-bent fore mast of ''Maine'' is located at the United States Naval Academy.

In 1926, the Cuban government erected a memorial to the victims of ''Maine'' on the Malecon, near the Hotel Nacional

"Hotel Nacional" ("National Hotel") is a song by Cuban-American recording artist Gloria Estefan. It was released as the second single from her studio album '' Miss Little Havana'' (2011). Written by Estefan, the song portrays the need to dance, ...

, to commemorate United States assistance in acquiring Cuban independence from Spain. The monument features two of ''Maine''s four 10-inch guns. In 1961, the memorial was damaged by crowds, following the Bay of Pigs Invasion

The Bay of Pigs Invasion (, sometimes called ''Invasión de Playa Girón'' or ''Batalla de Playa Girón'' after the Playa Girón) was a failed military landing operation on the southwestern coast of Cuba in 1961 by Cuban exiles, covertly fin ...

, and the eagle on top was broken and removed.

USS ''Maine'' Monument, New York City

File:USS Maine Mounment (1913), New York, NY (P1010836).JPG, USS ''Maine'' Monument in New York City

File:USS Maine (ACR-1) Monument Columbus Circle NYC.JPG, USS ''Maine'' Monument, Columbus Circle, NYC

File:USS Maine (ACR-1) Monument Columbus Circle NYC Columbia Triumphant.JPG, Columbia Triumphant

File:USS Maine Monument (1913), New York City (P1000111).JPG, Memorial plaque by Charles Keck, USS ''Maine'' Memorial

File:USS Maine Monument (1913), New York City (P1000124R).JPG, Sculpture group by Attilio Piccirilli

Attilio Piccirilli (May 16, 1866 – October 8, 1945) was an American sculptor. Born in Massa, Italy, he was educated at the Accademia di San Luca of Rome.

Life and career

Piccirilli came to the United States in 1888 and worked for his f ...

at USS ''Maine'' Memorial