United States Whig Party on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Whig Party was a

In the years following the 1824 election, former members of the Democratic-Republican Party split into hostile factions. Supporters of President Adams and Clay joined with many former Federalists such as

In the years following the 1824 election, former members of the Democratic-Republican Party split into hostile factions. Supporters of President Adams and Clay joined with many former Federalists such as

Shortly after Jackson's re-election, South Carolina passed a measure to " nullify" the Tariff of 1832, beginning the Nullification Crisis. Jackson strongly denied the right of South Carolina to nullify federal law, but the crisis was resolved after Congress passed the

Shortly after Jackson's re-election, South Carolina passed a measure to " nullify" the Tariff of 1832, beginning the Nullification Crisis. Jackson strongly denied the right of South Carolina to nullify federal law, but the crisis was resolved after Congress passed the

Early successes in various states made many Whigs optimistic about victory in 1836, but an improving economy bolstered Van Buren's standing ahead of the election. The Whigs also faced the difficulty of uniting former National Republicans, Anti-Masons, and states' rights Southerners around one candidate, and the party suffered an early blow when Calhoun announced that he would refuse to support any candidate opposed to the doctrine of nullification. Northern Whigs cast aside both Clay and Webster in favor of General

Early successes in various states made many Whigs optimistic about victory in 1836, but an improving economy bolstered Van Buren's standing ahead of the election. The Whigs also faced the difficulty of uniting former National Republicans, Anti-Masons, and states' rights Southerners around one candidate, and the party suffered an early blow when Calhoun announced that he would refuse to support any candidate opposed to the doctrine of nullification. Northern Whigs cast aside both Clay and Webster in favor of General  By early 1838, Clay had emerged as the front-runner due to his support in the South and his spirited opposition to Van Buren's Independent Treasury. A recovering economy convinced other Whigs to support Harrison, who was generally seen as the Whig candidate best able to win over Democrats and new voters. With the crucial support of Thaddeus Stevens of Pennsylvania and Thurlow Weed of New York, Harrison won the presidential nomination on the fifth ballot of the 1839 Whig National Convention.

For vice president, the Whigs nominated John Tyler, a former states' rights Democrat selected for the Whig ticket primarily because other Southern supporters of Clay refused to serve as Harrison's running mate. Log cabins and hard cider became the dominant symbols of the Whig campaign as the party sought to portray Harrison as a man of the people. The Whigs also assailed Van Buren's handling of the economy and argued that traditional Whig policies such as the restoration of a national bank and the implementation of protective tariff rates would help to restore the economy. With the economy still in a downturn, Harrison decisively defeated Van Buren, taking a wide majority of the electoral vote and just under 53 percent of the popular vote.

By early 1838, Clay had emerged as the front-runner due to his support in the South and his spirited opposition to Van Buren's Independent Treasury. A recovering economy convinced other Whigs to support Harrison, who was generally seen as the Whig candidate best able to win over Democrats and new voters. With the crucial support of Thaddeus Stevens of Pennsylvania and Thurlow Weed of New York, Harrison won the presidential nomination on the fifth ballot of the 1839 Whig National Convention.

For vice president, the Whigs nominated John Tyler, a former states' rights Democrat selected for the Whig ticket primarily because other Southern supporters of Clay refused to serve as Harrison's running mate. Log cabins and hard cider became the dominant symbols of the Whig campaign as the party sought to portray Harrison as a man of the people. The Whigs also assailed Van Buren's handling of the economy and argued that traditional Whig policies such as the restoration of a national bank and the implementation of protective tariff rates would help to restore the economy. With the economy still in a downturn, Harrison decisively defeated Van Buren, taking a wide majority of the electoral vote and just under 53 percent of the popular vote.

With the election of the first Whig presidential administration in the party's history, Clay and his allies prepared to pass ambitious domestic policies such as the restoration of the national bank, the distribution of federal land sales revenue to the states, a national bankruptcy law, and increased tariff rates. Harrison died just one month into his term, thereby elevating Vice President Tyler to the presidency.Holt (1999), pp. 127–128. Tyler had never accepted much of the Whig economic program and he soon clashed with Clay and other congressional Whigs. In August 1841, Tyler vetoed Clay's national bank bill, holding that the bill was unconstitutional.

Congress passed a second bill based on an earlier proposal made by Treasury Secretary Ewing that was tailored to address Tyler's constitutional concerns, but Tyler vetoed that bill as well. In response, every Cabinet member but Webster resigned, and the Whig congressional caucus expelled Tyler from the party on September 13, 1841. The Whigs later began impeachment proceedings against Tyler, but they ultimately declined to impeach him because they believed that his likely acquittal would devastate the party.

Beginning in mid-1842, Tyler increasingly began to court Democrats, appointing them to his Cabinet and other positions. At the same time, many Whig state organizations repudiated the Tyler administration and endorsed Clay as the party's candidate in the 1844 presidential election. After Webster resigned from the Cabinet in May 1843 following the conclusion of the Webster-Ashburton Treaty, Tyler made the annexation of Texas his key priority. The annexation of Texas was widely viewed as a pro-slavery initiative as it would add another slave state to the union, and most leaders of both parties opposed opening the question of annexation in 1843 due to the fear of stoking the debate over slavery. Tyler was nonetheless determined to pursue annexation because he believed that the British conspired to abolish slavery in Texas and because he saw the issue as a means to reelection, either through the Democratic Party or through a new party. In April 1844, Secretary of State John C. Calhoun reached a treaty with Texas providing for the annexation of that country.

Clay and Van Buren, the two front-runners for major-party presidential nominations in the 1844 election, both announced their opposition to annexation, and the Senate blocked the annexation treaty. To the surprise of Clay and other Whigs, the

With the election of the first Whig presidential administration in the party's history, Clay and his allies prepared to pass ambitious domestic policies such as the restoration of the national bank, the distribution of federal land sales revenue to the states, a national bankruptcy law, and increased tariff rates. Harrison died just one month into his term, thereby elevating Vice President Tyler to the presidency.Holt (1999), pp. 127–128. Tyler had never accepted much of the Whig economic program and he soon clashed with Clay and other congressional Whigs. In August 1841, Tyler vetoed Clay's national bank bill, holding that the bill was unconstitutional.

Congress passed a second bill based on an earlier proposal made by Treasury Secretary Ewing that was tailored to address Tyler's constitutional concerns, but Tyler vetoed that bill as well. In response, every Cabinet member but Webster resigned, and the Whig congressional caucus expelled Tyler from the party on September 13, 1841. The Whigs later began impeachment proceedings against Tyler, but they ultimately declined to impeach him because they believed that his likely acquittal would devastate the party.

Beginning in mid-1842, Tyler increasingly began to court Democrats, appointing them to his Cabinet and other positions. At the same time, many Whig state organizations repudiated the Tyler administration and endorsed Clay as the party's candidate in the 1844 presidential election. After Webster resigned from the Cabinet in May 1843 following the conclusion of the Webster-Ashburton Treaty, Tyler made the annexation of Texas his key priority. The annexation of Texas was widely viewed as a pro-slavery initiative as it would add another slave state to the union, and most leaders of both parties opposed opening the question of annexation in 1843 due to the fear of stoking the debate over slavery. Tyler was nonetheless determined to pursue annexation because he believed that the British conspired to abolish slavery in Texas and because he saw the issue as a means to reelection, either through the Democratic Party or through a new party. In April 1844, Secretary of State John C. Calhoun reached a treaty with Texas providing for the annexation of that country.

Clay and Van Buren, the two front-runners for major-party presidential nominations in the 1844 election, both announced their opposition to annexation, and the Senate blocked the annexation treaty. To the surprise of Clay and other Whigs, the

In the final weeks of Tyler's presidency, a small group of Southern Whigs joined with congressional Democrats to pass a joint resolution providing for the annexation of Texas, and Texas subsequently became a state in 1845. Following the annexation of Texas, Polk began preparations for a potential war with

In the final weeks of Tyler's presidency, a small group of Southern Whigs joined with congressional Democrats to pass a joint resolution providing for the annexation of Texas, and Texas subsequently became a state in 1845. Following the annexation of Texas, Polk began preparations for a potential war with  During the war, Whig leaders like John J. Crittenden of Kentucky began to look to General Taylor as a presidential candidate in the hopes that the party could run on Taylor's personal popularity rather than economic issues. Taylor's candidacy faced significant resistance in the Whig Party due to his lack of public commitment to Whig policies and his association with the Mexican-American War. In late 1847, Clay emerged as Taylor's main opponent for the Whig nomination, appealing especially to Northern Whigs with his opposition to the war and the acquisition of new territory.

With strong backing from slave state delegates, Taylor won the presidential nomination on the fourth ballot of the 1848 Whig National Convention. For vice president, the Whigs nominated Millard Fillmore of New York, a pro-Clay Northerner. Anti-slavery Northern Whigs disaffected with Taylor joined with Democratic supporters of Martin Van Buren and some members of the Liberty Party to found the new

During the war, Whig leaders like John J. Crittenden of Kentucky began to look to General Taylor as a presidential candidate in the hopes that the party could run on Taylor's personal popularity rather than economic issues. Taylor's candidacy faced significant resistance in the Whig Party due to his lack of public commitment to Whig policies and his association with the Mexican-American War. In late 1847, Clay emerged as Taylor's main opponent for the Whig nomination, appealing especially to Northern Whigs with his opposition to the war and the acquisition of new territory.

With strong backing from slave state delegates, Taylor won the presidential nomination on the fourth ballot of the 1848 Whig National Convention. For vice president, the Whigs nominated Millard Fillmore of New York, a pro-Clay Northerner. Anti-slavery Northern Whigs disaffected with Taylor joined with Democratic supporters of Martin Van Buren and some members of the Liberty Party to found the new

Reflecting the Taylor administration's desire to find a middle ground between traditional Whig and Democratic policies, Secretary of the Treasury William M. Meredith issued a report calling for an increase in tariff rates, but not to the levels seen under the Tariff of 1842. Even Meredith's moderate policies were not adopted, and, partly due to the strong economic growth of the late 1840s and late 1850s, traditional Whig economic stances would increasingly lose their salience after 1848. When Taylor assumed office, the organization of state and territorial governments and the status of slavery in the Mexican Cession remained the major issue facing Congress.

To sidestep the issue of the Wilmot Proviso, the Taylor administration proposed that the lands of the Mexican Cession be admitted as states without first organizing territorial governments; thus, slavery in the area would be left to the discretion of state governments rather than the federal government. In January 1850, Senator Clay introduced a separate proposal which included the admission of California as a free state, the cession by Texas of some of its northern and western territorial claims in return for debt relief, the establishment of

Reflecting the Taylor administration's desire to find a middle ground between traditional Whig and Democratic policies, Secretary of the Treasury William M. Meredith issued a report calling for an increase in tariff rates, but not to the levels seen under the Tariff of 1842. Even Meredith's moderate policies were not adopted, and, partly due to the strong economic growth of the late 1840s and late 1850s, traditional Whig economic stances would increasingly lose their salience after 1848. When Taylor assumed office, the organization of state and territorial governments and the status of slavery in the Mexican Cession remained the major issue facing Congress.

To sidestep the issue of the Wilmot Proviso, the Taylor administration proposed that the lands of the Mexican Cession be admitted as states without first organizing territorial governments; thus, slavery in the area would be left to the discretion of state governments rather than the federal government. In January 1850, Senator Clay introduced a separate proposal which included the admission of California as a free state, the cession by Texas of some of its northern and western territorial claims in return for debt relief, the establishment of  Taylor died in July 1850 and was succeeded by Vice President Fillmore. In contrast to John Tyler, Fillmore's legitimacy and authority as president were widely accepted by members of Congress and the public.. Fillmore accepted the resignation of Taylor's entire Cabinet and appointed Whig leaders like Crittenden,

Taylor died in July 1850 and was succeeded by Vice President Fillmore. In contrast to John Tyler, Fillmore's legitimacy and authority as president were widely accepted by members of Congress and the public.. Fillmore accepted the resignation of Taylor's entire Cabinet and appointed Whig leaders like Crittenden,

The Whigs celebrated Clay's vision of the American System, which promoted rapid economic and industrial growth in the United States through support for a national bank, high tariffs, a distribution policy, and federal funding for infrastructure projects. After the Second Bank of the United States lost its federal charter in 1836, the Whigs favored the restoration of a national bank that could provide a uniform currency, ensure a consistent supply of credit, and attract private investors. Through high tariffs, Clay and other Whigs hoped to generate revenue and encourage the establishment of domestic manufacturing, thereby freeing the United States from dependence on foreign imports.

High tariffs were also designed to prevent a negative

The Whigs celebrated Clay's vision of the American System, which promoted rapid economic and industrial growth in the United States through support for a national bank, high tariffs, a distribution policy, and federal funding for infrastructure projects. After the Second Bank of the United States lost its federal charter in 1836, the Whigs favored the restoration of a national bank that could provide a uniform currency, ensure a consistent supply of credit, and attract private investors. Through high tariffs, Clay and other Whigs hoped to generate revenue and encourage the establishment of domestic manufacturing, thereby freeing the United States from dependence on foreign imports.

High tariffs were also designed to prevent a negative

Political scientist A. James Reichley writes that the Democrats and Whigs were "political institutions of a kind that had never existed before in history" because they commanded mass membership among voters and continued to function between elections. Both parties drew support from voters of various classes, occupations, religions, and ethnicities. Nonetheless, the Whig Party was based among middle-class conservatives. The central fault line between the parties concerned the emerging

Political scientist A. James Reichley writes that the Democrats and Whigs were "political institutions of a kind that had never existed before in history" because they commanded mass membership among voters and continued to function between elections. Both parties drew support from voters of various classes, occupations, religions, and ethnicities. Nonetheless, the Whig Party was based among middle-class conservatives. The central fault line between the parties concerned the emerging

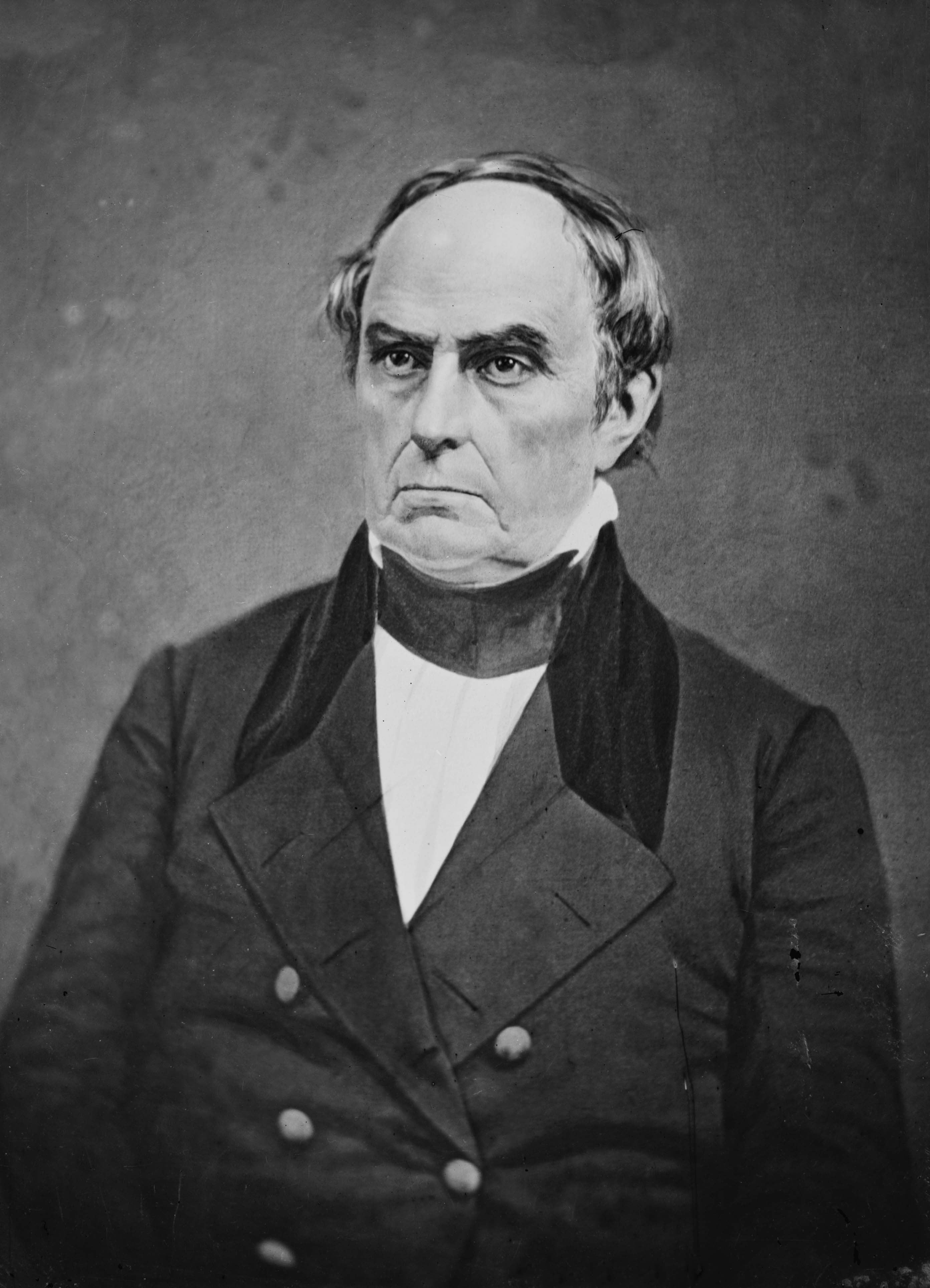

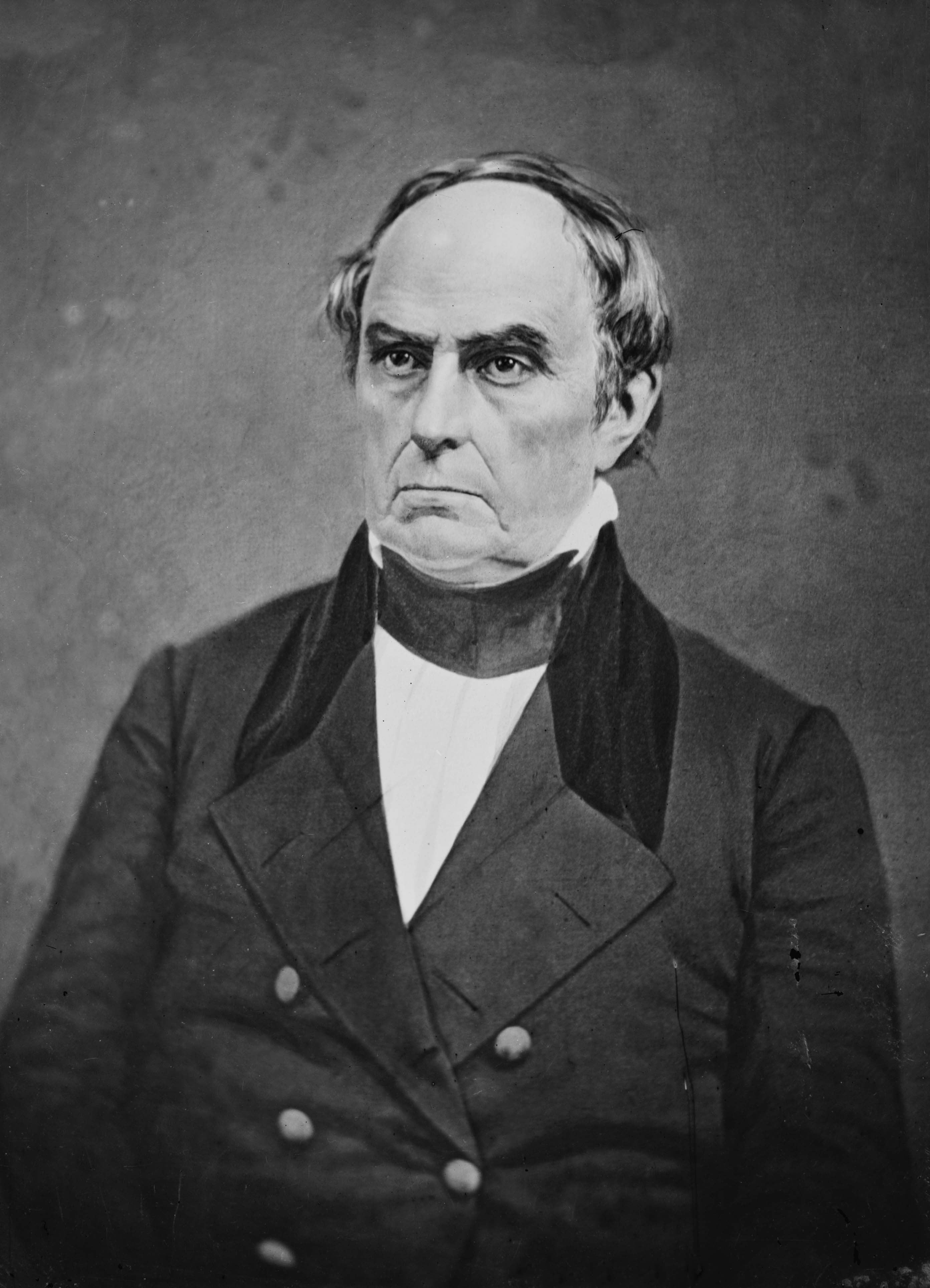

Henry Clay of Kentucky was the congressional leader of the party from the time of its formation in 1833 until his resignation from the Senate in 1842, and he remained an important Whig leader until his death in 1852. His frequent rival for leadership of the party was Daniel Webster, who represented Massachusetts in the Senate and served as Secretary of State under three Whig presidents. Clay and Webster each repeatedly sought the Whig presidential nomination, but, excepting Clay's nomination in 1844, the Whigs consistently nominated individuals who had served as generals, specifically William Henry Harrison, Zachary Taylor, and Winfield Scott. Harrison, Taylor, John Tyler, and Millard Fillmore all served as president, though Tyler was expelled from the Whig Party shortly after taking office in 1841. Benjamin Robbins Curtis was the lone Whig to serve on the

Henry Clay of Kentucky was the congressional leader of the party from the time of its formation in 1833 until his resignation from the Senate in 1842, and he remained an important Whig leader until his death in 1852. His frequent rival for leadership of the party was Daniel Webster, who represented Massachusetts in the Senate and served as Secretary of State under three Whig presidents. Clay and Webster each repeatedly sought the Whig presidential nomination, but, excepting Clay's nomination in 1844, the Whigs consistently nominated individuals who had served as generals, specifically William Henry Harrison, Zachary Taylor, and Winfield Scott. Harrison, Taylor, John Tyler, and Millard Fillmore all served as president, though Tyler was expelled from the Whig Party shortly after taking office in 1841. Benjamin Robbins Curtis was the lone Whig to serve on the

online

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

online

* Carpenter, Daniel, and Benjamin Schneer. "Party formation through petitions: The Whigs and the Bank War of 1832–1834". ''Studies in American Political Development'' 29.2 (2015): 213–234. * Carroll, E. Malcolm. ''Origins of the Whig Party'' (1925

online

* Clauson, Loryn. "The Whigs' America Middle-Class Political Thought in the Age of Jackson and Clay by Joseph W. Pearson." ''Ohio Valley History'' 22.1 (2022): 90-92. * * * * * * Gerring, John. ''Party Ideologies in America, 1828–1996'' (1998). * Gienap, William E. ''The Origins of the Republican Party, 1852–1856'' (Harvard University Press, 1987) * Hammond, Bray. ''Banks and Politics in America from the Revolution to the Civil War'' (1960), Pulitzer prize; the standard history. Pro-Bank * * primary sources * * Husch, Gail E. "George Caleb Bingham’s The County Election: Whig Tribute to the Will of the People." ''Critical Issues in American Art'' (Routledge, 2018) pp. 77-92. * * * * Mueller, Henry R.; ''The Whig Party in Pennsylvania,'' (1922

online

* Nevins, Allan. ''The Ordeal of the Union'' (1947) ''vol 1: Fruits of Manifest Destiny, 1847–1852; vol 2. A House Dividing, 1852–1857''. highly detailed narrative of national politics * Ormsby, Robert McKinley (1859). ''A History of the Whig Party'', Crosby, Nichols & Company, Boston, 377 pages

e-book

* Pearson, Joseph W. ''The Whigs' America: Middle-Class Political Thought in the Age of Jackson and Clay'' (University Press of Kentucky, 2020). * Pegg, Herbert Dale (1932). ''The Whig Party in North Carolina'', Colonial Press, 223 pages

Book

* Poage, George Rawlings. ''Henry Clay and the Whig Party'' (1936) *

online

* * Renda, Lex. "The Dysfunctional Party: Collapse of the New Jersey Whigs, 1849- 1853," ''New Jersey History'' 116 (Spring/Summer, 1998), 3-57. * * Schlesinger, Arthur Meier, Jr. ed. ''History of American Presidential Elections, 1789–2000'' (various multivolume editions, latest is 2001). * * * Sharp, James Roger. ''The Jacksonians Versus the Banks: Politics in the States after the Panic of 1837'' (1970) * * * Smith, Craig R. "Daniel Webster's Epideictic Speaking: A Study in Emerging Whig Virtues

* Trainor, Sean. ''Gale Researcher Guide for: The Second Party System'' (Gale, Cengage Learning, 2018). * * * * Van Deusen, Glyndon G. ''The Jacksonian Era: 1828- 1848'' (1959

online

* Van Deusen, Glyndon G. ''The life of Henry Clay'' (1979

online

* Van Deusen, Glyndon G. ''Thurlow Weed, Wizard of the Lobby'' (1947

online

* Williams, Max R. "The Foundations of the Whig Party in North Carolina: A Synthesis and a Modest Proposal." ''North Carolina Historical Review'' 47.2 (1970): 115-129

online

* Wilson, Major L. ''Space, Time, and Freedom: The Quest for Nationality and the Irrepressible Conflict, 1815–1861'' (1974) intellectual history of Whigs and Democrats

Whig Party in Virginia in ''Encyclopedia Virginia''

The American Presidency Project

contains the text of the national platforms that were adopted by the national conventions (1844–1856). * * {{Authority control Whig Party (United States), 1834 establishments in the United States 1856 disestablishments in the United States Political parties established in 1834 Political parties disestablished in 1856 Defunct conservative parties in the United States Defunct political parties in the United States Second Party System Political parties in the United States Conservatism in the United States

political party

A political party is an organization that coordinates candidates to compete in a particular country's elections. It is common for the members of a party to hold similar ideas about politics, and parties may promote specific political ideology ...

in the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., federal district, five ma ...

during the middle of the 19th century. Alongside the slightly larger Democratic Party Democratic Party most often refers to:

*Democratic Party (United States)

Democratic Party and similar terms may also refer to:

Active parties Africa

*Botswana Democratic Party

*Democratic Party of Equatorial Guinea

*Gabonese Democratic Party

*Demo ...

, it was one of the two major parties

A major party is a political party that holds substantial influence in a country's politics, standing in contrast to a minor party.

According to the Merriam-Webster Dictionary:

Major parties hold a significant percentage of the vote in elect ...

in the United States between the late 1830s and the early 1850s as part of the Second Party System

Historians and political scientists use Second Party System to periodize the Political parties in the United States, political party system operating in the United States from about 1828 to 1852, after the First Party System ended. The system was ...

. Four presidents were affiliated with the Whig Party for at least part of their terms. Other prominent members of the Whig Party include Henry Clay

Henry Clay Sr. (April 12, 1777June 29, 1852) was an American attorney and statesman who represented Kentucky in both the U.S. Senate and House of Representatives. He was the seventh House speaker as well as the ninth secretary of state, ...

, Daniel Webster

Daniel Webster (January 18, 1782 – October 24, 1852) was an American lawyer and statesman who represented New Hampshire and Massachusetts in the U.S. Congress and served as the U.S. Secretary of State under Presidents William Henry Harri ...

, Rufus Choate, William Seward

William Henry Seward (May 16, 1801 – October 10, 1872) was an American politician who served as United States Secretary of State from 1861 to 1869, and earlier served as governor of New York and as a United States Senator. A determined oppo ...

, John J. Crittenden, and John Quincy Adams

John Quincy Adams (; July 11, 1767 – February 23, 1848) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, and diarist who served as the sixth president of the United States, from 1825 to 1829. He previously served as the eighth United States S ...

. The Whig base of support was centered among entrepreneurs, professionals, planters, social reformers, devout Protestants, and the emerging urban middle class. It had much less backing from poor farmers and unskilled workers.

The party was critical of Manifest Destiny

Manifest destiny was a cultural belief in the 19th-century United States that American settlers were destined to expand across North America.

There were three basic tenets to the concept:

* The special virtues of the American people and th ...

, territorial expansion into Texas and the Southwest, and the Mexican-American War. It disliked strong presidential power as exhibited by Jackson and Polk, and preferred Congressional dominance in lawmaking. Members advocated modernization, meritocracy

Meritocracy (''merit'', from Latin , and ''-cracy'', from Ancient Greek 'strength, power') is the notion of a political system in which economic goods and/or political power are vested in individual people based on talent, effort, and achie ...

, the rule of law, protections against majority tyranny, and vigilance against executive tyranny. They favored an economic program known as the American System, which called for a protective tariff

A tariff is a tax imposed by the government of a country or by a supranational union on imports or exports of goods. Besides being a source of revenue for the government, import duties can also be a form of regulation of foreign trade and p ...

, federal subsidies for the construction of infrastructure, and support for a national bank. The party was active in both the Northern United States

The Northern United States, commonly referred to as the American North, the Northern States, or simply the North, is a geographical or historical region of the United States.

History Early history

Before the 19th century westward expansion, the " ...

and the Southern United States

The Southern United States (sometimes Dixie, also referred to as the Southern States, the American South, the Southland, or simply the South) is a geographic and cultural region of the United States of America. It is between the Atlantic Ocean ...

and did not take a strong stance on slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

, but Northern Whigs tended to be less supportive than their Democratic counterparts.

The Whigs emerged in the 1830s in opposition to President Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was an American lawyer, planter, general, and statesman who served as the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before being elected to the presidency, he gained fame a ...

, pulling together former members of the National Republican Party

The National Republican Party, also known as the Anti-Jacksonian Party or simply Republicans, was a political party in the United States that evolved from a conservative-leaning faction of the Democratic-Republican Party that supported John ...

, the Anti-Masonic Party

The Anti-Masonic Party was the earliest third party in the United States. Formally a single-issue party, it strongly opposed Freemasonry, but later aspired to become a major party by expanding its platform to take positions on other issues. Afte ...

, and disaffected Democrats. The Whigs had some weak links to the defunct Federalist Party

The Federalist Party was a conservative political party which was the first political party in the United States. As such, under Alexander Hamilton, it dominated the national government from 1789 to 1801.

Defeated by the Jeffersonian Repub ...

, but the Whig Party was not a direct successor to that party and many Whig leaders, including Henry Clay, had aligned with the rival Democratic-Republican Party

The Democratic-Republican Party, known at the time as the Republican Party and also referred to as the Jeffersonian Republican Party among other names, was an American political party founded by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison in the early ...

. In the 1836 presidential election, four different regional Whig candidates received electoral votes, but the party failed to defeat Jackson's chosen successor, Martin Van Buren

Martin Van Buren ( ; nl, Maarten van Buren; ; December 5, 1782 – July 24, 1862) was an American lawyer and statesman who served as the eighth president of the United States from 1837 to 1841. A primary founder of the Democratic Party, he ...

. Whig nominee William Henry Harrison

William Henry Harrison (February 9, 1773April 4, 1841) was an American military officer and politician who served as the ninth president of the United States. Harrison died just 31 days after his inauguration in 1841, and had the shortest pres ...

unseated Van Buren in the 1840 presidential election, but died just one month into his term. Harrison's successor, John Tyler

John Tyler (March 29, 1790 – January 18, 1862) was the tenth president of the United States, serving from 1841 to 1845, after briefly holding office as the tenth vice president of the United States, vice president in 1841. He was elected v ...

, a former Democrat, broke with the Whigs in 1841 after clashing with Clay and other Whig Party leaders over economic policies such as the re-establishment of a national bank.

Clay clinched his party's nomination in the 1844 presidential election but was defeated by Democrat James K. Polk, who subsequently presided over the Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War, also known in the United States as the Mexican War and in Mexico as the (''United States intervention in Mexico''), was an armed conflict between the United States and Second Federal Republic of Mexico, Mexico f ...

. Whig nominee Zachary Taylor

Zachary Taylor (November 24, 1784 – July 9, 1850) was an American military leader who served as the 12th president of the United States from 1849 until his death in 1850. Taylor was a career officer in the United States Army, rising to th ...

won the 1848 presidential election, but Taylor died in 1850 and was succeeded by Millard Fillmore

Millard Fillmore (January 7, 1800March 8, 1874) was the 13th president of the United States, serving from 1850 to 1853; he was the last to be a member of the Whig Party while in the White House. A former member of the U.S. House of Represen ...

. Fillmore, Clay, Daniel Webster, and Democrat Stephen A. Douglas led the passage of the Compromise of 1850

The Compromise of 1850 was a package of five separate bills passed by the United States Congress in September 1850 that defused a political confrontation between slave and free states on the status of territories acquired in the Mexican– ...

, which helped to defuse sectional tensions in the aftermath of the Mexican–American War. Nonetheless, the Whigs suffered a decisive defeat in the 1852 presidential election partly due to sectional divisions within the party. The Whigs collapsed following the passage of the Kansas–Nebraska Act in 1854, with most Northern Whigs eventually joining the anti-slavery Republican Party

Republican Party is a name used by many political parties around the world, though the term most commonly refers to the United States' Republican Party.

Republican Party may also refer to:

Africa

*Republican Party (Liberia)

* Republican Part ...

and most Southern Whigs joining the nativist American Party and later the Constitutional Union Party. The last vestiges of the Whig Party faded away after the start of the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by state ...

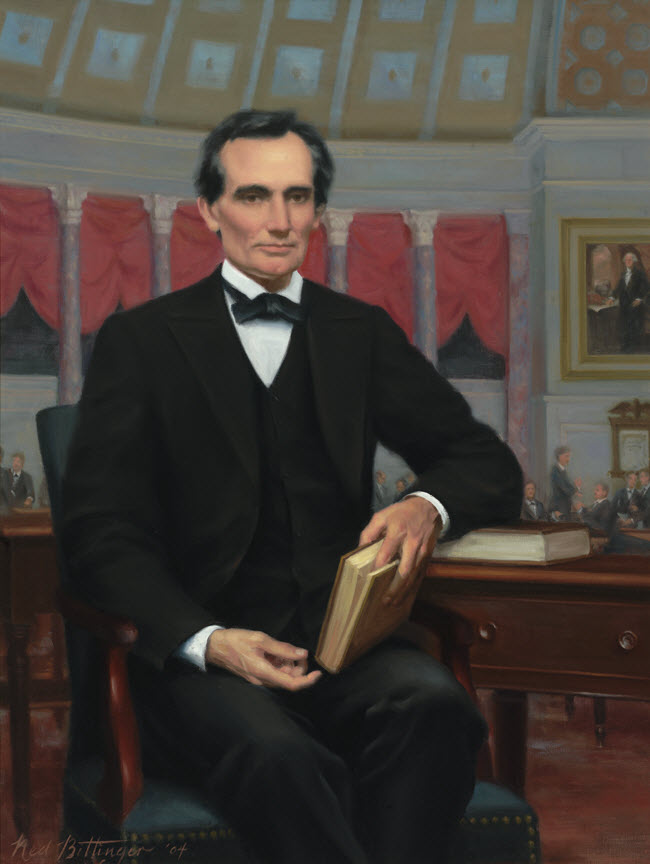

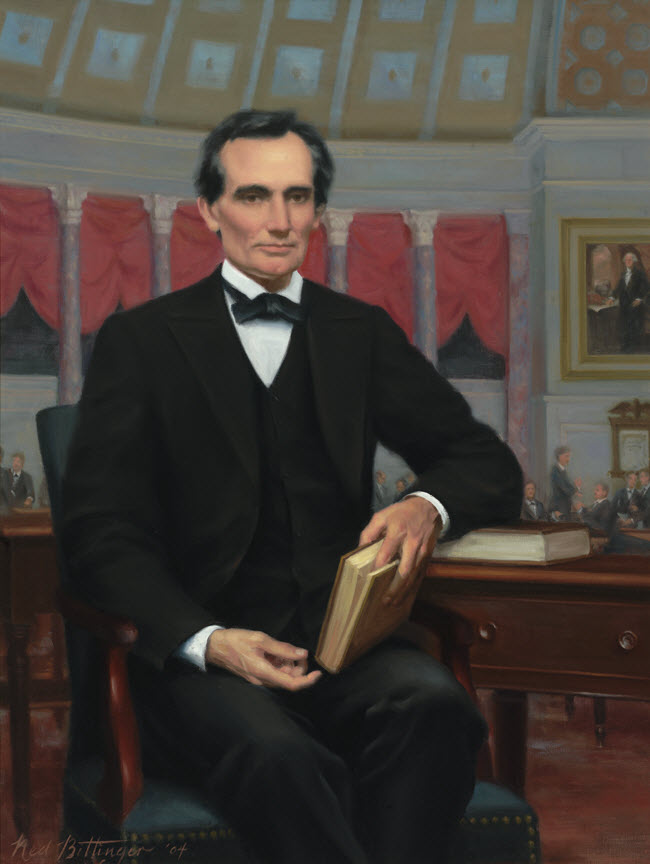

, but Whig ideas remained influential for decades. During the Lincoln Administration, ex-Whigs dominated the Republican Party and enacted much of their American System. Presidents Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

, Rutherford B. Hayes, Chester A. Arthur, and Benjamin Harrison

Benjamin Harrison (August 20, 1833March 13, 1901) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 23rd president of the United States from 1889 to 1893. He was a member of the Harrison family of Virginia–a grandson of the ninth pr ...

were Whigs before switching to the Republican Party, from which they were elected to office. It is considered the primary predecessor party of the modern-day Republicans

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

.

Background

During the 1790s, the first major U.S. parties arose in the form of theFederalist Party

The Federalist Party was a conservative political party which was the first political party in the United States. As such, under Alexander Hamilton, it dominated the national government from 1789 to 1801.

Defeated by the Jeffersonian Repub ...

, led by Alexander Hamilton, and the Democratic-Republican Party

The Democratic-Republican Party, known at the time as the Republican Party and also referred to as the Jeffersonian Republican Party among other names, was an American political party founded by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison in the early ...

, led by Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 1801 to 1809. He was previously the nati ...

. After 1815, the Democratic-Republicans emerged as the sole major party at the national level but became increasingly polarized. A nationalist wing, led by Henry Clay

Henry Clay Sr. (April 12, 1777June 29, 1852) was an American attorney and statesman who represented Kentucky in both the U.S. Senate and House of Representatives. He was the seventh House speaker as well as the ninth secretary of state, ...

, favored policies such as the Second Bank of the United States and the implementation of a protective tariff. A second group, the Old Republicans, opposed these policies, instead favoring a strict interpretation of the Constitution and a weak federal government.Holt (1999), pp. 2–3

In the 1824 presidential election, Speaker of the House Henry Clay

Henry Clay Sr. (April 12, 1777June 29, 1852) was an American attorney and statesman who represented Kentucky in both the U.S. Senate and House of Representatives. He was the seventh House speaker as well as the ninth secretary of state, ...

, Secretary of the Treasury William H. Crawford, Secretary of State John Quincy Adams

John Quincy Adams (; July 11, 1767 – February 23, 1848) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, and diarist who served as the sixth president of the United States, from 1825 to 1829. He previously served as the eighth United States S ...

, and General Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was an American lawyer, planter, general, and statesman who served as the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before being elected to the presidency, he gained fame a ...

all sought the presidency as members of the Democratic-Republican Party. Crawford favored state sovereignty and a strict constructionist view of the Constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When these princip ...

, while Clay and Adams favored high tariffs and the national bank; regionalism played a central role, with Jackson strongest in the West. Jackson won a plurality of the popular and electoral vote in the 1824 election, but not a majority. The House of Representatives had to decide. Speaker Clay supported Adams, who was elected as president by the House, and Clay was appointed as Secretary of State. Jackson called it a "corrupt bargain".

In the years following the 1824 election, former members of the Democratic-Republican Party split into hostile factions. Supporters of President Adams and Clay joined with many former Federalists such as

In the years following the 1824 election, former members of the Democratic-Republican Party split into hostile factions. Supporters of President Adams and Clay joined with many former Federalists such as Daniel Webster

Daniel Webster (January 18, 1782 – October 24, 1852) was an American lawyer and statesman who represented New Hampshire and Massachusetts in the U.S. Congress and served as the U.S. Secretary of State under Presidents William Henry Harri ...

to form a group informally known as the "Adams party". Meanwhile, supporters of Jackson, Crawford, and Vice President John C. Calhoun

John Caldwell Calhoun (; March 18, 1782March 31, 1850) was an American statesman and political theorist from South Carolina who held many important positions including being the seventh vice president of the United States from 1825 to 1832. He ...

joined to oppose the Adams administration's nationalist agenda, becoming informally known as "Jacksonians".Holt (1999), pp. 7–8 Due in part to the superior organization (by Martin Van Buren) of the Jacksonians, Jackson defeated Adams in the 1828 presidential election, taking 56 percent of the popular vote. Clay became the leader of the National Republican Party

The National Republican Party, also known as the Anti-Jacksonian Party or simply Republicans, was a political party in the United States that evolved from a conservative-leaning faction of the Democratic-Republican Party that supported John ...

, which opposed President Jackson. By the early 1830s, the Jacksonians organized into the new Democratic Party Democratic Party most often refers to:

*Democratic Party (United States)

Democratic Party and similar terms may also refer to:

Active parties Africa

*Botswana Democratic Party

*Democratic Party of Equatorial Guinea

*Gabonese Democratic Party

*Demo ...

.Holt (1999), pp. 10–11

Despite Jackson's decisive victory in the 1828 election, National Republicans initially believed that Jackson's party would collapse once Jackson took office. Vice President Calhoun split from the administration in 1831, but differences over the tariff prevented Calhoun's followers from joining the National Republicans. Meanwhile, the Anti-Masonic Party

The Anti-Masonic Party was the earliest third party in the United States. Formally a single-issue party, it strongly opposed Freemasonry, but later aspired to become a major party by expanding its platform to take positions on other issues. Afte ...

formed following the disappearance and possible murder of William Morgan in 1826. The Anti-Masonic movement, strongest in the Northeast, gave rise to or expanded the use of many innovations which became accepted practice among other parties, including nominating conventions and party newspapers. Clay rejected overtures from the Anti-Masonic Party, and his attempt to convince Calhoun to serve as his running mate failed, leaving the opposition to Jackson split among different leaders when the National Republicans nominated Clay for president.

Hoping to make the national bank a key issue of the 1832 election, the National Republicans convinced national bank president Nicholas Biddle to request an extension of the national bank's charter, but their strategy backfired when Jackson successfully portrayed his veto of the recharter as a victory for the people against an elitist institution. Jackson won another decisive victory in the 1832 presidential election, taking 55 percent of the national popular vote and 88 percent of the popular vote in the slave states south of Kentucky and Maryland. Clay's defeat discredited the National Republican Party, encouraging those opposed to Jackson to seek to create a more effective opposition party. Jackson by 1832 was determined to destroy the bank (the Second Bank of the United States), which Whigs supported.

History

Creation, 1833–1836

Shortly after Jackson's re-election, South Carolina passed a measure to " nullify" the Tariff of 1832, beginning the Nullification Crisis. Jackson strongly denied the right of South Carolina to nullify federal law, but the crisis was resolved after Congress passed the

Shortly after Jackson's re-election, South Carolina passed a measure to " nullify" the Tariff of 1832, beginning the Nullification Crisis. Jackson strongly denied the right of South Carolina to nullify federal law, but the crisis was resolved after Congress passed the Tariff of 1833

The Tariff of 1833 (also known as the Compromise Tariff of 1833, ch. 55, ), enacted on March 2, 1833, was proposed by Henry Clay and John C. Calhoun as a resolution to the Nullification Crisis. Enacted under Andrew Jackson's presidency, it was ...

.Holt (1999), p. 20. The Nullification Crisis briefly scrambled the partisan divisions that had emerged after 1824, as many within the Jacksonian coalition opposed President Jackson's threats of force against South Carolina, while some opposition leaders like Daniel Webster supported them. In South Carolina and other states, those opposed to Jackson began to form small "Whig" parties. The Whig label implicitly compared "King Andrew" to King George III

George III (George William Frederick; 4 June 173829 January 1820) was King of Great Britain and of Ireland from 25 October 1760 until the union of the two kingdoms on 1 January 1801, after which he was King of the United Kingdom of Great Br ...

, the King of Great Britain at the time of the American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revolu ...

.

Jackson's decision to remove government deposits from the national bank ended any possibility of a Webster-Jackson alliance and helped to solidify partisan lines. The removal of the deposits drew opposition from both pro-bank National Republicans and states' rights

In American political discourse, states' rights are political powers held for the state governments rather than the federal government according to the United States Constitution, reflecting especially the enumerated powers of Congress and ...

Southerners like Willie Person Mangum of North Carolina, the latter of whom accused Jackson of flouting the Constitution. In late 1833, Clay began to hold a series of dinners with opposition leaders in order to settle on a candidate to oppose Martin Van Buren

Martin Van Buren ( ; nl, Maarten van Buren; ; December 5, 1782 – July 24, 1862) was an American lawyer and statesman who served as the eighth president of the United States from 1837 to 1841. A primary founder of the Democratic Party, he ...

, the likely Democratic nominee in the 1836 presidential election. While Jackson's opponents could not agree on a single presidential candidate, they coordinated in the Senate to oppose Jackson's initiatives. Historian Michael Holt writes that the "birth of the Whig Party" can be dated to Clay and his allies taking control of the Senate in December 1833.Holt (1999), pp. 26–27.

The National Republicans, including Clay and Webster, formed the core of the Whig Party, but many Anti-Masons like William H. Seward of New York and Thaddeus Stevens

Thaddeus Stevens (April 4, 1792August 11, 1868) was a member of the United States House of Representatives from Pennsylvania, one of the leaders of the Radical Republican faction of the Republican Party during the 1860s. A fierce opponent of sla ...

of Pennsylvania also joined. Several prominent Democrats defected to the Whigs, including Mangum, former Attorney General John Berrien, and John Tyler

John Tyler (March 29, 1790 – January 18, 1862) was the tenth president of the United States, serving from 1841 to 1845, after briefly holding office as the tenth vice president of the United States, vice president in 1841. He was elected v ...

of Virginia. The Whig Party's first major action was to censure

A censure is an expression of strong disapproval or harsh criticism. In parliamentary procedure, it is a Debate (parliamentary procedure), debatable main motion that could be adopted by a majority vote. Among the forms that it can take are a ster ...

Jackson for the removal of the national bank deposits, thereby establishing opposition to Jackson's executive power as the organizing principle of the new party.

In doing so, the Whigs were able to shed the elitist image that had persistently hindered the National Republicans. Throughout 1834 and 1835, the Whigs successfully incorporated National Republican and Anti-Masonic state-level organizations and established new state party organizations in Southern states like North Carolina and Georgia. The Anti-Masonic heritage to the Whigs included a distrust of behind-the-scenes political maneuvering by party bosses, instead of encouraging direct appeals to the people through gigantic rallies, parades, and rhetorical rabble-rousing.

Rise, 1836–1841

Early successes in various states made many Whigs optimistic about victory in 1836, but an improving economy bolstered Van Buren's standing ahead of the election. The Whigs also faced the difficulty of uniting former National Republicans, Anti-Masons, and states' rights Southerners around one candidate, and the party suffered an early blow when Calhoun announced that he would refuse to support any candidate opposed to the doctrine of nullification. Northern Whigs cast aside both Clay and Webster in favor of General

Early successes in various states made many Whigs optimistic about victory in 1836, but an improving economy bolstered Van Buren's standing ahead of the election. The Whigs also faced the difficulty of uniting former National Republicans, Anti-Masons, and states' rights Southerners around one candidate, and the party suffered an early blow when Calhoun announced that he would refuse to support any candidate opposed to the doctrine of nullification. Northern Whigs cast aside both Clay and Webster in favor of General William Henry Harrison

William Henry Harrison (February 9, 1773April 4, 1841) was an American military officer and politician who served as the ninth president of the United States. Harrison died just 31 days after his inauguration in 1841, and had the shortest pres ...

, a former senator who had led U.S. forces in the 1811 Battle of Tippecanoe.Holt (1999), pp. 40–42.

Though he had not previously been affiliated with the National Republicans, Harrison indicated that he shared the party's concerns over Jackson's executive power and favored federal investments in infrastructure. Southern Whigs coalesced around Senator Hugh Lawson White, a long-time Jackson ally who opposed Van Buren's candidacy. Ultimately, Van Buren won a majority of the electoral and popular vote in the 1836 election, though the Whigs improved on Clay's 1832 performance in the South and West.

Shortly after Van Buren took office, an economic crisis known as the Panic of 1837 struck the nation. Land prices plummeted, industries laid-off employees, and banks failed. According to historian Daniel Walker Howe, the economic crisis of the late 1830s and early 1840s was the most severe recession in U.S. history until the Great Depression. Van Buren's economic response centered on establishing the Independent Treasury system, essentially a series of vaults that would hold government deposits. As the debate over the Independent Treasury continued, William Cabell Rives and some other Democrats who favored a more activist government defected to the Whig Party, while Calhoun and his followers joined the Democratic Party. Whig leaders agreed to hold the party's first national convention in December 1839 in order to select the Whig presidential nominee.

Harrison and Tyler, 1841–1845

With the election of the first Whig presidential administration in the party's history, Clay and his allies prepared to pass ambitious domestic policies such as the restoration of the national bank, the distribution of federal land sales revenue to the states, a national bankruptcy law, and increased tariff rates. Harrison died just one month into his term, thereby elevating Vice President Tyler to the presidency.Holt (1999), pp. 127–128. Tyler had never accepted much of the Whig economic program and he soon clashed with Clay and other congressional Whigs. In August 1841, Tyler vetoed Clay's national bank bill, holding that the bill was unconstitutional.

Congress passed a second bill based on an earlier proposal made by Treasury Secretary Ewing that was tailored to address Tyler's constitutional concerns, but Tyler vetoed that bill as well. In response, every Cabinet member but Webster resigned, and the Whig congressional caucus expelled Tyler from the party on September 13, 1841. The Whigs later began impeachment proceedings against Tyler, but they ultimately declined to impeach him because they believed that his likely acquittal would devastate the party.

Beginning in mid-1842, Tyler increasingly began to court Democrats, appointing them to his Cabinet and other positions. At the same time, many Whig state organizations repudiated the Tyler administration and endorsed Clay as the party's candidate in the 1844 presidential election. After Webster resigned from the Cabinet in May 1843 following the conclusion of the Webster-Ashburton Treaty, Tyler made the annexation of Texas his key priority. The annexation of Texas was widely viewed as a pro-slavery initiative as it would add another slave state to the union, and most leaders of both parties opposed opening the question of annexation in 1843 due to the fear of stoking the debate over slavery. Tyler was nonetheless determined to pursue annexation because he believed that the British conspired to abolish slavery in Texas and because he saw the issue as a means to reelection, either through the Democratic Party or through a new party. In April 1844, Secretary of State John C. Calhoun reached a treaty with Texas providing for the annexation of that country.

Clay and Van Buren, the two front-runners for major-party presidential nominations in the 1844 election, both announced their opposition to annexation, and the Senate blocked the annexation treaty. To the surprise of Clay and other Whigs, the

With the election of the first Whig presidential administration in the party's history, Clay and his allies prepared to pass ambitious domestic policies such as the restoration of the national bank, the distribution of federal land sales revenue to the states, a national bankruptcy law, and increased tariff rates. Harrison died just one month into his term, thereby elevating Vice President Tyler to the presidency.Holt (1999), pp. 127–128. Tyler had never accepted much of the Whig economic program and he soon clashed with Clay and other congressional Whigs. In August 1841, Tyler vetoed Clay's national bank bill, holding that the bill was unconstitutional.

Congress passed a second bill based on an earlier proposal made by Treasury Secretary Ewing that was tailored to address Tyler's constitutional concerns, but Tyler vetoed that bill as well. In response, every Cabinet member but Webster resigned, and the Whig congressional caucus expelled Tyler from the party on September 13, 1841. The Whigs later began impeachment proceedings against Tyler, but they ultimately declined to impeach him because they believed that his likely acquittal would devastate the party.

Beginning in mid-1842, Tyler increasingly began to court Democrats, appointing them to his Cabinet and other positions. At the same time, many Whig state organizations repudiated the Tyler administration and endorsed Clay as the party's candidate in the 1844 presidential election. After Webster resigned from the Cabinet in May 1843 following the conclusion of the Webster-Ashburton Treaty, Tyler made the annexation of Texas his key priority. The annexation of Texas was widely viewed as a pro-slavery initiative as it would add another slave state to the union, and most leaders of both parties opposed opening the question of annexation in 1843 due to the fear of stoking the debate over slavery. Tyler was nonetheless determined to pursue annexation because he believed that the British conspired to abolish slavery in Texas and because he saw the issue as a means to reelection, either through the Democratic Party or through a new party. In April 1844, Secretary of State John C. Calhoun reached a treaty with Texas providing for the annexation of that country.

Clay and Van Buren, the two front-runners for major-party presidential nominations in the 1844 election, both announced their opposition to annexation, and the Senate blocked the annexation treaty. To the surprise of Clay and other Whigs, the 1844 Democratic National Convention

The 1844 Democratic National Convention was a presidential nominating convention held in Baltimore, Maryland from May 27 through 30. The convention nominated former Governor James K. Polk of Tennessee for president and former Senator George M. Dal ...

rejected Van Buren in favor of James K. Polk and established a platform calling for the acquisition of both Texas and Oregon Country

Oregon Country was a large region of the Pacific Northwest of North America that was subject to a long dispute between the United Kingdom and the United States in the early 19th century. The area, which had been created by the Treaty of 1818, c ...

. Having won the presidential nomination at the 1844 Whig National Convention

The 1844 Whig National Convention was a presidential nominating convention held on May 1, 1844 at Universalist Church in Baltimore, Maryland. It nominated the Whig Party's candidates for president and vice president in the 1844 election. The ...

unopposed, Clay and other Whigs were initially confident that they would defeat the divided Democrats and their relatively obscure candidate.

However, Southern voters responded to Polk's calls for annexation, while in the North, Democrats benefited from the growing animosity towards the Whig Party among Catholic and foreign-born voters. Ultimately, Polk won the election, taking 49.5% of the popular vote and a majority of the electoral vote; the swing of just over one percent of the vote in New York would have given Clay the victory.

Polk and the Mexican–American War, 1845–1849

In the final weeks of Tyler's presidency, a small group of Southern Whigs joined with congressional Democrats to pass a joint resolution providing for the annexation of Texas, and Texas subsequently became a state in 1845. Following the annexation of Texas, Polk began preparations for a potential war with

In the final weeks of Tyler's presidency, a small group of Southern Whigs joined with congressional Democrats to pass a joint resolution providing for the annexation of Texas, and Texas subsequently became a state in 1845. Following the annexation of Texas, Polk began preparations for a potential war with Mexico

Mexico ( Spanish: México), officially the United Mexican States, is a country in the southern portion of North America. It is bordered to the north by the United States; to the south and west by the Pacific Ocean; to the southeast by Guate ...

, which still regarded Texas as a part of its republic and contended that Texas's true southern border was the Nueces River rather than the Rio Grande

The Rio Grande ( and ), known in Mexico as the Río Bravo del Norte or simply the Río Bravo, is one of the principal rivers (along with the Colorado River) in the southwestern United States and in northern Mexico.

The length of the Rio ...

.Merry (2009), pp. 188–189. After a skirmish known as the Thornton Affair broke out on the northern side of the Rio Grande,Merry (2009), pp. 240–242. Polk called on Congress to declare war against Mexico, arguing that Mexico had invaded American territory by crossing the Rio Grande.Merry (2009), pp. 244–245.

Many Whigs argued that Polk had provoked war with Mexico by sending a force under General Zachary Taylor

Zachary Taylor (November 24, 1784 – July 9, 1850) was an American military leader who served as the 12th president of the United States from 1849 until his death in 1850. Taylor was a career officer in the United States Army, rising to th ...

to the Rio Grande, but only a minority of Whigs voted against the declaration of war as they feared that opposing the war would be politically unpopular. Polk received the declaration of war against Mexico and also pushed through the restoration of the Independent Treasury System and a bill that reduced tariffs; opposition to the passage of these Democratic policies helped to reunify and reinvigorate the Whigs.

In August 1846, Polk asked Congress to appropriate $2 million in hopes of using that money as a down payment for the purchase of California in a treaty with Mexico.Merry (2009), pp. 283–285. Democratic Congressman David Wilmot of Pennsylvania offered an amendment known as the Wilmot Proviso, which would ban slavery in any newly acquired lands.Merry (2009), pp. 286–289. The Wilmot Proviso passed the House with the support of both Northern Whigs and Northern Democrats, breaking the normal pattern of partisan division in congressional votes, but it was defeated in the Senate.

Nonetheless, clear divisions remained between the two parties on territorial acquisitions, as most Democrats joined Polk in seeking to acquire vast tracts of land from Mexico, but most Whigs opposed territorial growth. In February 1848, Mexican and U.S. negotiators reached the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo ( es, Tratado de Guadalupe Hidalgo), officially the Treaty of Peace, Friendship, Limits, and Settlement between the United States of America and the United Mexican States, is the peace treaty that was signed on 2 ...

, which provided for the cession of Alta California and New Mexico.Merry (2009), pp. 424–426. Despite Whig objections to the acquisition of Mexican territory, the treaty was ratified with the support of a majority of the Democratic and Whig senators; Whigs voted for the treaty largely because ratification brought the war to an immediate end.

During the war, Whig leaders like John J. Crittenden of Kentucky began to look to General Taylor as a presidential candidate in the hopes that the party could run on Taylor's personal popularity rather than economic issues. Taylor's candidacy faced significant resistance in the Whig Party due to his lack of public commitment to Whig policies and his association with the Mexican-American War. In late 1847, Clay emerged as Taylor's main opponent for the Whig nomination, appealing especially to Northern Whigs with his opposition to the war and the acquisition of new territory.

With strong backing from slave state delegates, Taylor won the presidential nomination on the fourth ballot of the 1848 Whig National Convention. For vice president, the Whigs nominated Millard Fillmore of New York, a pro-Clay Northerner. Anti-slavery Northern Whigs disaffected with Taylor joined with Democratic supporters of Martin Van Buren and some members of the Liberty Party to found the new

During the war, Whig leaders like John J. Crittenden of Kentucky began to look to General Taylor as a presidential candidate in the hopes that the party could run on Taylor's personal popularity rather than economic issues. Taylor's candidacy faced significant resistance in the Whig Party due to his lack of public commitment to Whig policies and his association with the Mexican-American War. In late 1847, Clay emerged as Taylor's main opponent for the Whig nomination, appealing especially to Northern Whigs with his opposition to the war and the acquisition of new territory.

With strong backing from slave state delegates, Taylor won the presidential nomination on the fourth ballot of the 1848 Whig National Convention. For vice president, the Whigs nominated Millard Fillmore of New York, a pro-Clay Northerner. Anti-slavery Northern Whigs disaffected with Taylor joined with Democratic supporters of Martin Van Buren and some members of the Liberty Party to found the new Free Soil Party

The Free Soil Party was a short-lived coalition political party in the United States active from 1848 to 1854, when it merged into the Republican Party. The party was largely focused on the single issue of opposing the expansion of slavery i ...

; the party nominated a ticket of Van Buren and Whig Charles Francis Adams Sr. and campaigned against the spread of slavery into the territories.

The Whig campaign in the North received a boost when Taylor released a public letter in which he stated that he favored Whig principles and would defer to Congress after taking office, thereby reassuring some wavering Whigs. During the campaign, Northern Whig leaders touted traditional Whig policies like support for infrastructure spending and increased tariff rates, but Southern Whigs largely eschewed economic policy, instead emphasizing that Taylor's status as a slaveholder meant that he could be trusted on the issue of slavery more so than Democratic candidate Lewis Cass of Michigan. Ultimately, Taylor won the election with a majority of the electoral vote and a plurality of the popular vote. Taylor improved on Clay's 1844 performance in the South and benefited from the defection of many Democrats to Van Buren in the North.

Taylor and Fillmore, 1849–1853

Reflecting the Taylor administration's desire to find a middle ground between traditional Whig and Democratic policies, Secretary of the Treasury William M. Meredith issued a report calling for an increase in tariff rates, but not to the levels seen under the Tariff of 1842. Even Meredith's moderate policies were not adopted, and, partly due to the strong economic growth of the late 1840s and late 1850s, traditional Whig economic stances would increasingly lose their salience after 1848. When Taylor assumed office, the organization of state and territorial governments and the status of slavery in the Mexican Cession remained the major issue facing Congress.

To sidestep the issue of the Wilmot Proviso, the Taylor administration proposed that the lands of the Mexican Cession be admitted as states without first organizing territorial governments; thus, slavery in the area would be left to the discretion of state governments rather than the federal government. In January 1850, Senator Clay introduced a separate proposal which included the admission of California as a free state, the cession by Texas of some of its northern and western territorial claims in return for debt relief, the establishment of

Reflecting the Taylor administration's desire to find a middle ground between traditional Whig and Democratic policies, Secretary of the Treasury William M. Meredith issued a report calling for an increase in tariff rates, but not to the levels seen under the Tariff of 1842. Even Meredith's moderate policies were not adopted, and, partly due to the strong economic growth of the late 1840s and late 1850s, traditional Whig economic stances would increasingly lose their salience after 1848. When Taylor assumed office, the organization of state and territorial governments and the status of slavery in the Mexican Cession remained the major issue facing Congress.

To sidestep the issue of the Wilmot Proviso, the Taylor administration proposed that the lands of the Mexican Cession be admitted as states without first organizing territorial governments; thus, slavery in the area would be left to the discretion of state governments rather than the federal government. In January 1850, Senator Clay introduced a separate proposal which included the admission of California as a free state, the cession by Texas of some of its northern and western territorial claims in return for debt relief, the establishment of New Mexico

)

, population_demonym = New Mexican ( es, Neomexicano, Neomejicano, Nuevo Mexicano)

, seat = Santa Fe, New Mexico, Santa Fe

, LargestCity = Albuquerque, New Mexico, Albuquerque

, LargestMetro = Albuquerque metropolitan area, Tiguex

, Offi ...

and Utah

Utah ( , ) is a state in the Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. Utah is a landlocked U.S. state bordered to its east by Colorado, to its northeast by Wyoming, to its north by Idaho, to its south by Arizona, and to its ...

territories, a ban on the importation of slaves into the District of Columbia for sale, and a more stringent fugitive slave law.

Taylor died in July 1850 and was succeeded by Vice President Fillmore. In contrast to John Tyler, Fillmore's legitimacy and authority as president were widely accepted by members of Congress and the public.. Fillmore accepted the resignation of Taylor's entire Cabinet and appointed Whig leaders like Crittenden,

Taylor died in July 1850 and was succeeded by Vice President Fillmore. In contrast to John Tyler, Fillmore's legitimacy and authority as president were widely accepted by members of Congress and the public.. Fillmore accepted the resignation of Taylor's entire Cabinet and appointed Whig leaders like Crittenden, Thomas Corwin

Thomas Corwin (July 29, 1794 – December 18, 1865), also known as Tom Corwin, The Wagon Boy, and Black Tom was a politician from the state of Ohio. He represented Ohio in both houses of Congress and served as the 15th governor of Ohio and the 2 ...

of Ohio, and Webster, whose support for the Compromise had outraged his Massachusetts constituents. With the support of Fillmore and an impressing bipartisan and bi-sectional coalition, a Senate bill providing for a final settlement of Texas's borders won passage shortly after Fillmore took office.

The Senate quickly moved onto the other major issues, passing bills that provided for the admission of California, the organization of New Mexico Territory, and the establishment of a new fugitive slave law. Passage of what became known as the Compromise of 1850

The Compromise of 1850 was a package of five separate bills passed by the United States Congress in September 1850 that defused a political confrontation between slave and free states on the status of territories acquired in the Mexican– ...

soon followed in the House of Representatives. Though the future of slavery in New Mexico, Utah, and other territories remained unclear, Fillmore himself described the Compromise of 1850 as a "final settlement" of sectional issues.

Following the passage of the Compromise of 1850, Fillmore's enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850

The Fugitive Slave Act or Fugitive Slave Law was passed by the United States Congress on September 18, 1850, as part of the Compromise of 1850 between Southern interests in slavery and Northern

Northern may refer to the following:

Geogra ...

became the central issue of his administration. The Whig Party became badly split between pro-Compromise Whigs like Fillmore and Webster and anti-Compromise Whigs like William Seward, who demanded the repeal of the Fugitive Slave Act.

Though Fillmore's enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Act made him unpopular among many in the North, he retained considerable support in the South. Meanwhile, Secretary Webster had long coveted the presidency and, though in poor health, planned a final attempt to gain the White House. A third candidate emerged in the form of General Winfield Scott, who won the backing of many Northerners but whose association with Senator William Seward made him unacceptable to Southern Whigs.

On the first presidential ballot of the 1852 Whig National Convention

The 1852 Whig National Convention was a presidential nominating convention held from June 17 to June 20, in Baltimore, Maryland. It nominated the Whig Party's candidates for president and vice president in the 1852 election. The convention s ...

, Fillmore received 133 of the necessary 147 votes, while Scott won 131 and Webster won 29. Fillmore and Webster's supporters were unable to broker a deal to unite behind either candidate, and Scott won the nomination on the 53rd ballot. The 1852 Democratic National Convention

The 1852 Democratic National Convention was a presidential nominating convention that met from June 1 to June 5 in Baltimore, Maryland. It was held to nominate the Democratic Party's candidates for president and vice president in the 1852 elect ...

nominated a dark horse candidate in the form of former New Hampshire senator Franklin Pierce, a Northerner sympathetic to the Southern view on slavery.

As the Whig and Democratic national conventions had approved similar platforms, the 1852 election focused largely on the personalities of Scott and Pierce. The 1852 elections proved to be disastrous for the Whig Party, as Scott was defeated by a wide margin and the Whigs lost several congressional and state elections. Scott amassed more votes than Taylor had in most Northern states, but Democrats benefited from a surge of new voters in the North and the collapse of Whig strength in much of the South.

Collapse, 1853–1856

Despite their decisive loss in the 1852 elections, most Whig leaders believed the party could recover during the Pierce presidency in much the same way that it had recovered under President Polk. However, the strong economy still prevented the Whig economic program from regaining salience, and the party failed to develop an effective platform on which to campaign. The debate over the 1854 Kansas–Nebraska Act, which effectively repealed theMissouri Compromise

The Missouri Compromise was a federal legislation of the United States that balanced desires of northern states to prevent expansion of slavery in the country with those of southern states to expand it. It admitted Missouri as a slave state an ...

by allowing slavery in territories north of the 36°30′ parallel, shook up traditional partisan alignments.Holt (1999), pp. 804–805, 809–810.

Across the Northern states, opposition to the Kansas–Nebraska Act gave rise to anti-Nebraska coalitions consisting of Democrats focused on this opposition along with Free Soilers and Whigs. In Michigan and Wisconsin, these two coalitions labeled themselves as the Republican Party

Republican Party is a name used by many political parties around the world, though the term most commonly refers to the United States' Republican Party.

Republican Party may also refer to:

Africa

*Republican Party (Liberia)

* Republican Part ...

, but similar groups in other states initially took on different names. Like their Free Soil predecessors, Republican leaders generally did not call for the abolition of slavery but instead sought to prevent the extension of slavery into the territories.

Another political coalition appeared in the form of the nativist and anti-Catholic Know Nothing

The Know Nothing party was a nativist political party and movement in the United States in the mid-1850s. The party was officially known as the "Native American Party" prior to 1855 and thereafter, it was simply known as the "American Party". ...

movement, which eventually organized itself into the American Party. Both the Republican Party and the Know-Nothings portrayed themselves as the natural Whig heirs in the battle against Democratic executive tyranny, but the Republicans focused on the " Slave Power" and the Know-Nothings focused on the supposed danger of mass immigration and a Catholic conspiracy. While the Republican Party almost exclusively appealed to Northerners, the Know-Nothings gathered many adherents in both the North and South; some individuals joined both groups even while they remained part of the Whig Party or the Democratic Party.

Congressional Democrats suffered huge losses in the mid-term elections of 1854, as voters provided support to a wide array of new parties opposed to the Democratic Party. Though several successful congressional candidates had campaigned only as Whigs, most congressional candidates who were not affiliated with the Democratic Party had campaigned either independently of the Whig Party or in collusion with another party. As cooperation between Northern and Southern Whigs increasingly appeared to be impossible, leaders from both sections continued to abandon the party. Though he did not share the nativist views of the Know-Nothings, in 1855 Fillmore became a member of the Know-Nothing movement and encouraged his Whig followers to join as well. In September 1855, Seward led his faction of Whigs into the Republican Party, effectively marking the end of the Whig Party as an independent and significant political force.Holt (1999), pp. 947–949. Thus, the 1856 presidential election became a three-sided contest between Democrats, Know-Nothings, and Republicans.

The Know Nothing National Convention nominated Fillmore for president, but disagreements over the party platform's stance on slavery caused many Northern Know-Nothings to abandon the party. Meanwhile, the 1856 Republican National Convention

The 1856 Republican National Convention was a presidential nominating convention that met from June 17 to June 19 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. It was the first national nominating convention of the Republican Party, which had been founded tw ...

chose John C. Frémont as the party's presidential candidate. The defection of many Northern Know-Nothings, combined with the caning of Charles Sumner and other events that stoked sectional tensions, bolstered Republicans throughout the North. During his campaign, Fillmore minimized the issue of nativism, instead of attempting to use his campaign as a platform for unionism and a revival of the Whig Party.

Seeking to rally support from Whigs who had yet to join another party, Fillmore and his allies organized the sparsely-attended 1856 Whig National Convention

The 1856 Whig National Convention was a presidential nominating convention held from September 17 to September 18, in Baltimore, Maryland. Attended by a rump group of Whigs who had not yet left the declining party, the 1856 convention was the l ...

, which nominated Fillmore for president. Ultimately, Democrat James Buchanan

James Buchanan Jr. ( ; April 23, 1791June 1, 1868) was an American lawyer, diplomat and politician who served as the 15th president of the United States from 1857 to 1861. He previously served as secretary of state from 1845 to 1849 and repr ...

won the election with a majority of the electoral vote and 45 percent of the popular vote; Frémont won most of the remaining electoral votes and took 33 percent of the popular vote, while Fillmore won 22 percent of the popular vote and just eight electoral votes. Fillmore largely retained Taylor and Scott voters in the South, but most former Whigs in the North voted for Frémont rather than Fillmore.

Fillmore's American Party collapsed after the 1856 election, and many former Whigs who refused to join the Democratic Party or the Republican Party organized themselves into a loose coalition known as the Opposition Party. For the 1860 presidential election, Senator John J. Crittenden and other unionist conservatives formed the Constitutional Union Party. The party nominated a ticket consisting of John Bell, a long-time Whig senator, and Edward Everett, who had succeeded Daniel Webster as Fillmore's Secretary of State.Green (2007), pp. 234–236 With the nomination of two former Whigs, many regarded the Constitutional Union Party as a continuation of the Whig Party; one Southern newspaper called the new party the "ghost of the old Whig Party".

The party campaigned on preserving the union and took an official non-stance on slavery.Green (2007), pp. 237–238 The Constitutional Union ticket won a plurality of the vote in three states, but Bell finished in fourth place in the national popular vote behind Republican Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...