United States Populist Party on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The People's Party, also known as the Populist Party or simply the Populists, was a

The Farmer's Alliance had initially sought to work within the two-party system, but by 1891 many party leaders had become convinced of the need for a third party that could challenge the conservatism of both major parties. In the

The Farmer's Alliance had initially sought to work within the two-party system, but by 1891 many party leaders had become convinced of the need for a third party that could challenge the conservatism of both major parties. In the  The February 1892 Farmer's Alliance convention was attended by supporters of

The February 1892 Farmer's Alliance convention was attended by supporters of

The initial front-runner for the Populist Party's presidential nomination was Leonidas Polk, who had served as the chairman of the convention in St. Louis, but he died of an illness weeks before the Populist convention. The party instead turned to former Union General and 1880 Greenback presidential nominee James B. Weaver of Iowa, nominating him on a ticket with former Confederate army officer James G. Field of Virginia. The convention agreed to a

The initial front-runner for the Populist Party's presidential nomination was Leonidas Polk, who had served as the chairman of the convention in St. Louis, but he died of an illness weeks before the Populist convention. The party instead turned to former Union General and 1880 Greenback presidential nominee James B. Weaver of Iowa, nominating him on a ticket with former Confederate army officer James G. Field of Virginia. The convention agreed to a

In the lead-up to the

In the lead-up to the

The Populist movement never recovered from the failure of 1896, and national fusion with the Democrats proved disastrous to the party. In the Midwest, the Populist Party essentially merged into the Democratic Party before the end of the 1890s. In the South, the National alliance with the Democrats sapped the Populists' ability to remain independent. Tennessee's Populist Party was demoralized by a diminishing membership, and puzzled and split by the dilemma of whether to fight the state-level enemy (the Democrats) or the national foe (the Republicans and

The Populist movement never recovered from the failure of 1896, and national fusion with the Democrats proved disastrous to the party. In the Midwest, the Populist Party essentially merged into the Democratic Party before the end of the 1890s. In the South, the National alliance with the Democrats sapped the Populists' ability to remain independent. Tennessee's Populist Party was demoralized by a diminishing membership, and puzzled and split by the dilemma of whether to fight the state-level enemy (the Democrats) or the national foe (the Republicans and

in JSTOR

* Hicks, John D. ''The Populist Revolt: A History of the Farmers' Alliance and the People's Party'' Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 1931. * * Hild, Matthew. ''Arkansas's Gilded Age: The Rise, Decline, and Legacy of Populism and Working-Class Protest'' (U of Missouri Press, 2018

online review

* * * * * * Knoles, George Harmon. "Populism and Socialism, with Special Reference to the Election of 1892," ''Pacific Historical Review,'' vol. 12, no. 3 (Sept. 1943), pp. 295–304

In JSTOR

* Kuzminski, Adrian. Fixing the System: A History of Populism, Ancient & Modern. New York: Continuum Books, 2008. * * * * Miller, Worth Robert. "A Centennial Historiography of American Populism." ''Kansas History'' 1993 16(1): 54–69

* Miller, Worth Robert. "Farmers and Third-Party Politics in Late Nineteenth Century America," in Charles W. Calhoun, ed. ''The Gilded Age: Essays on the Origins of Modern America'' (1995

online edition

* * * * Peterson, James. "The Trade Unions and the Populist Party," ''Science & Society,'' vol. 8, no. 2 (Spring 1944), pp. 143–160

In JSTOR

* * * * * * *

online edition

* Woodward, C. Vann. "Tom Watson and the Negro in Agrarian Politics," ''The Journal of Southern History,'' Vol. 4, No. 1 (Feb., 1938), pp. 14–3

in JSTOR

* ttps://web.archive.org/web/20110304043632/http://clio.missouristate.edu/wrmiller/Populism/2scartoon/index.htm 40 original Populist cartoons primary sources * Peffer, William A. "The Mission of the Populist Party," ''The North American Review'' (Dec 1993) v. 157 #445 pp 665–679

full text online

important policy statement by leading Populist senator

official party pamphlet for North Carolina election of 1898

primary sources

secondary and primary sources Party publications and materials

The People's Advocate (1892-1900)

digitized copies of the Populist Party's newspaper in Washington State, from

Populist Cartoon Index

Archived at Missouri State University. Retrieved August 24, 2006.

Reprinted from Issue 19, ''Buttons and Ballots'', Fall 1998. Retrieved August 26, 2006.

Electronic Edition. Populist Party (N.C.). State Executive Committee. Reformated and reprinted by the University Library, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

courtesy University Library, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Secondary sources

''The Populist Movement in the United States''

by Anna Rochester, 1943.

'. By Kenneth G. McCarty. Published b

a project of the Mississippi Historical Society. Retrieved August 24, 2006.

Published by the ttp://www.nebraskastudies.org/ Nebraskastudies.org a project of th

Nebraska Department of Education

''Fusion Politics''

The Populist Party in North Carolina. A project of the

''The Decline of the Cotton Farmer''

Anecdotal account of rise and fall of Farmers Alliance and Populist Party in Texas. * {{Authority control Populism Political parties established in 1887 Political parties disestablished in 1908 Progressive Era in the United States Political parties in the United States Defunct agrarian political parties Left-wing populism in the United States

left-wing

Left-wing politics describes the range of political ideologies that support and seek to achieve social equality and egalitarianism, often in opposition to social hierarchy. Left-wing politics typically involve a concern for those in so ...

agrarian

Agrarian means pertaining to agriculture, farmland, or rural areas.

Agrarian may refer to:

Political philosophy

*Agrarianism

*Agrarian law, Roman laws regulating the division of the public lands

*Agrarian reform

*Agrarian socialism

Society

...

populist

Populism refers to a range of political stances that emphasize the idea of "the people" and often juxtapose this group against " the elite". It is frequently associated with anti-establishment and anti-political sentiment. The term develope ...

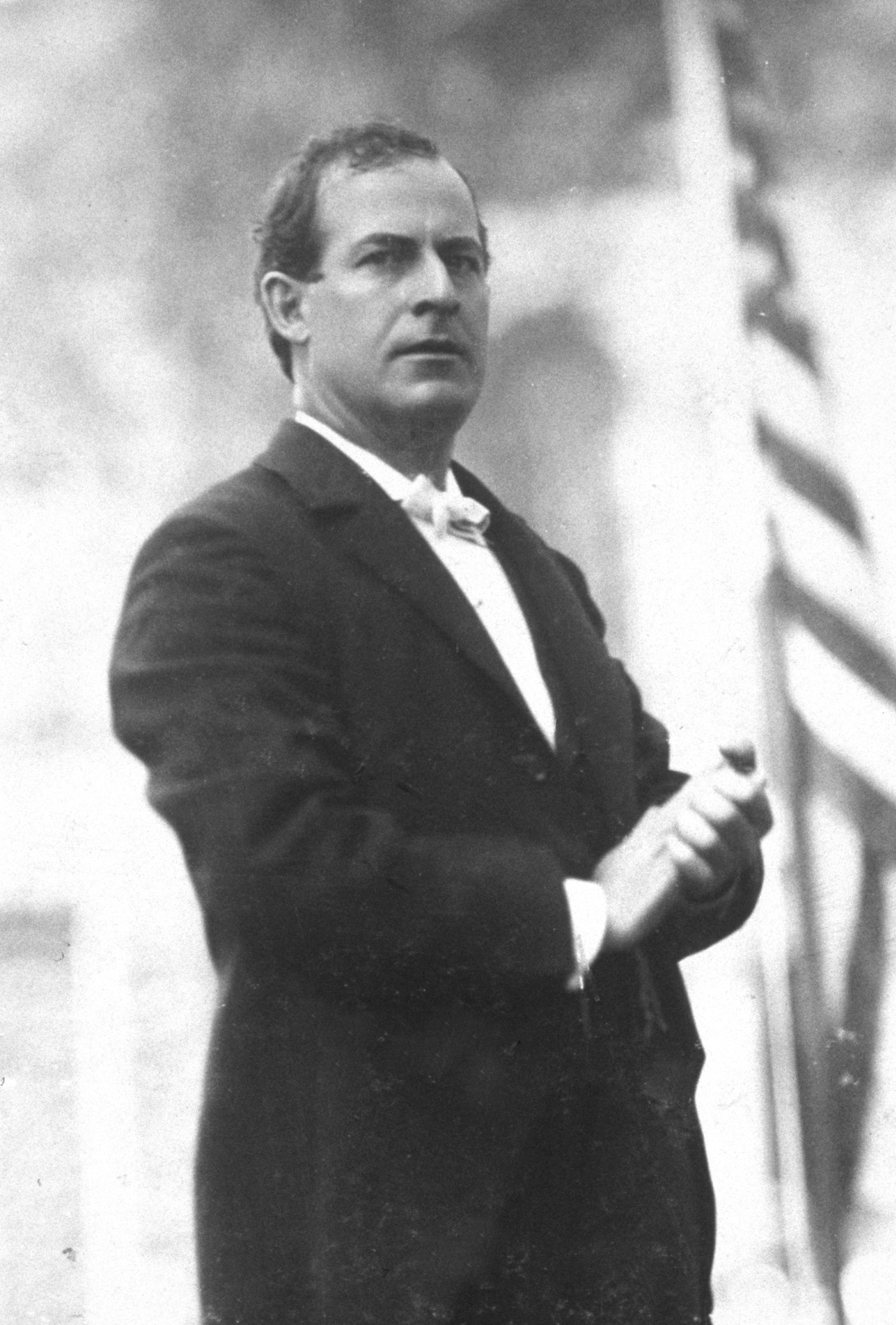

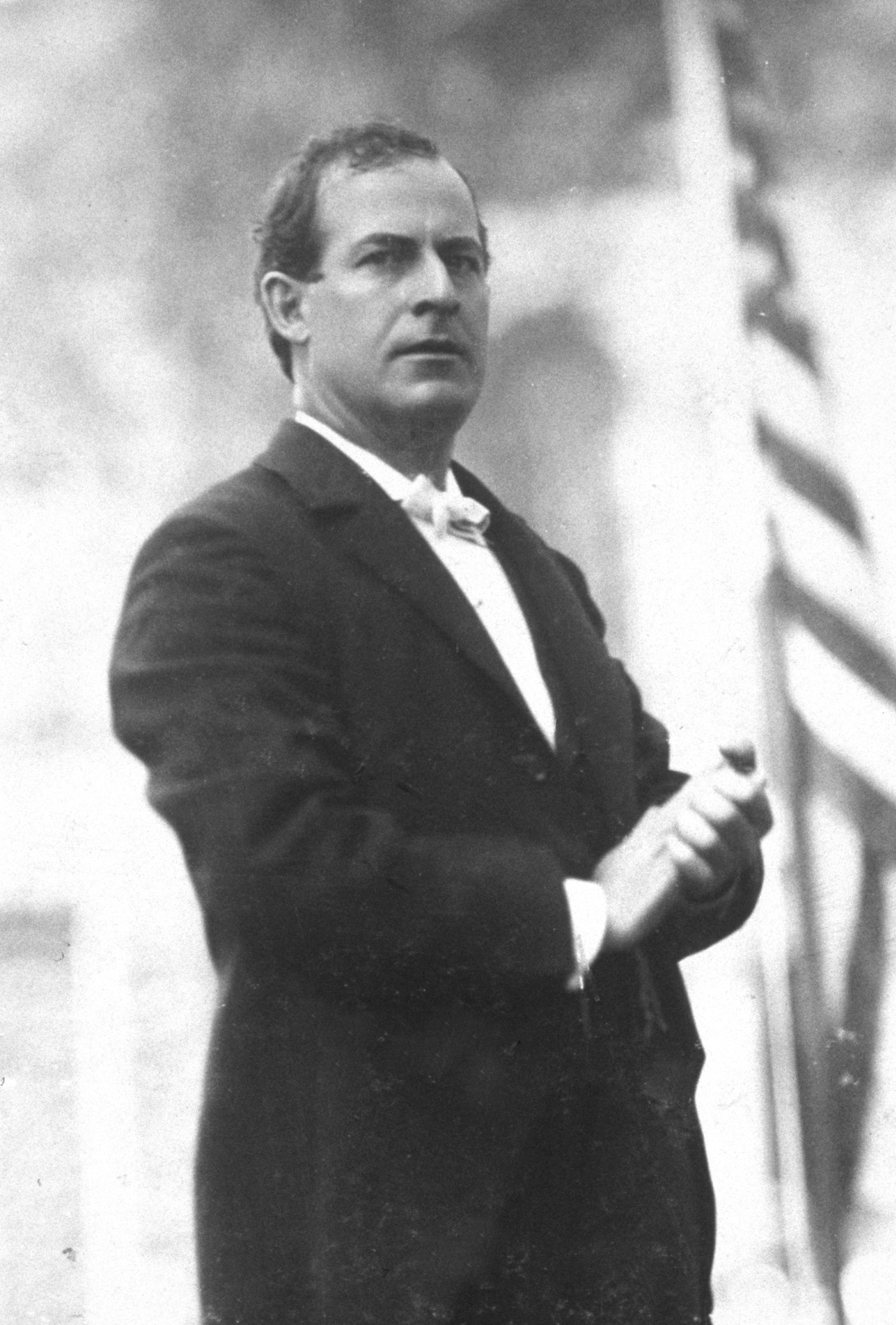

political party in the United States in the late 19th century. The Populist Party emerged in the early 1890s as an important force in the Southern and Western United States, but collapsed after it nominated Democrat William Jennings Bryan

William Jennings Bryan (March 19, 1860 – July 26, 1925) was an American lawyer, orator and politician. Beginning in 1896, he emerged as a dominant force in the Democratic Party, running three times as the party's nominee for President ...

in the 1896 United States presidential election

The 1896 United States presidential election was the 28th quadrennial presidential election, held on Tuesday, November 3, 1896. Former Governor William McKinley, the Republican candidate, defeated former Representative William Jennings Brya ...

. A rump faction of the party continued to operate into the first decade of the 20th century, but never matched the popularity of the party in the early 1890s.

The Populist Party's roots lay in the Farmers' Alliance

The Farmers' Alliance was an organized agrarian economic movement among American farmers that developed and flourished ca. 1875. The movement included several parallel but independent political organizations — the National Farmers' Alliance and ...

, an agrarian movement that promoted economic action during the Gilded Age

In United States history, the Gilded Age was an era extending roughly from 1877 to 1900, which was sandwiched between the Reconstruction era and the Progressive Era. It was a time of rapid economic growth, especially in the Northern and We ...

, as well as the Greenback Party

The Greenback Party (known successively as the Independent Party, the National Independent Party and the Greenback Labor Party) was an American political party with an anti-monopoly ideology which was active between 1874 and 1889. The party ran ...

, an earlier third party that had advocated fiat money

Fiat money (from la, fiat, "let it be done") is a type of currency that is not backed by any commodity such as gold or silver. It is typically designated by the issuing government to be legal tender. Throughout history, fiat money was sometim ...

. The success of Farmers' Alliance candidates in the 1890 elections

Year 189 ( CLXXXIX) was a common year starting on Wednesday (link will display the full calendar) of the Julian calendar. At the time, it was known as the Year of the Consulship of Silanus and Silanus (or, less frequently, year 942 ''Ab urbe ...

, along with the conservatism of both major parties, encouraged Farmers' Alliance leaders to establish a full-fledged third party

Third party may refer to:

Business

* Third-party source, a supplier company not owned by the buyer or seller

* Third-party beneficiary, a person who could sue on a contract, despite not being an active party

* Third-party insurance, such as a Veh ...

before the 1892 elections

Year 189 ( CLXXXIX) was a common year starting on Wednesday (link will display the full calendar) of the Julian calendar. At the time, it was known as the Year of the Consulship of Silanus and Silanus (or, less frequently, year 942 ''Ab urbe c ...

. The Ocala Demands

The Ocala Demands was a platform for economic and political reform that was later adopted by the People's Party.

In December, 1890, the National Farmers' Alliance and Industrial Union, more commonly known as the Southern Farmers' Alliance, its af ...

laid out the Populist platform: collective bargaining, federal regulation of railroad rates, an expansionary monetary policy, and a Sub-Treasury Plan that required the establishment of federally controlled warehouses to aid farmers. Other Populist-endorsed measures included bimetallism, a graduated income tax

An income tax is a tax imposed on individuals or entities (taxpayers) in respect of the income or profits earned by them (commonly called taxable income). Income tax generally is computed as the product of a tax rate times the taxable income. Tax ...

, direct election of Senators, a shorter workweek, and the establishment of a postal savings system

Postal savings systems provide depositors who do not have access to banks a safe and convenient method to save money. Many nations have operated banking systems involving post offices to promote saving money among the poor.

History

In 1861, G ...

. These measures were collectively designed to curb the influence of monopolistic corporate and financial interests and empower small businesses, farmers and laborers.

In the 1892 presidential election

The following elections occurred in the year 1892.

{{TOC right

Asia Japan

* 1892 Japanese general election

Europe Denmark

* 1892 Danish Folketing election

Portugal

* 1892 Portuguese legislative election

United Kingdom

* 1892 Chelmsford by-elec ...

, the Populist ticket of James B. Weaver and James G. Field won 8.5% of the popular vote and carried four Western states, becoming the first third party since the end of the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by state ...

to win electoral votes. Despite the support of labor organizers like Eugene V. Debs

Eugene Victor "Gene" Debs (November 5, 1855 – October 20, 1926) was an American socialist, political activist, trade unionist, one of the founding members of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), and five times the candidate of the Soc ...

and Terence V. Powderly, the party largely failed to win the vote of urban laborers in the Midwest

The Midwestern United States, also referred to as the Midwest or the American Midwest, is one of four census regions of the United States Census Bureau (also known as "Region 2"). It occupies the northern central part of the United States. ...

and the Northeast

The points of the compass are a set of horizontal, radially arrayed compass directions (or azimuths) used in navigation and cartography. A compass rose is primarily composed of four cardinal directions—north, east, south, and west—each sepa ...

. Over the next four years, the party continued to run state and federal candidates, building up powerful organizations in several Southern and Western states. Before the 1896 presidential election

The following elections occurred in 1896:

{{TOC right

North America

Canada

* 1896 Canadian federal election

* December 1896 Edmonton municipal election

* January 1896 Edmonton municipal election

* 1896 Manitoba general election

United States

* ...

, the Populists became increasingly polarized between "fusionists," who wanted to nominate a joint presidential ticket with the Democratic Party, and "mid-roaders," like Mary Elizabeth Lease, who favored the continuation of the Populists as an independent third party. After the 1896 Democratic National Convention

The 1896 Democratic National Convention, held at the Chicago Coliseum from July 7 to July 11, was the scene of William Jennings Bryan's nomination as the Democratic presidential candidate for the 1896 U.S. presidential election.

At age 36, Br ...

nominated William Jennings Bryan

William Jennings Bryan (March 19, 1860 – July 26, 1925) was an American lawyer, orator and politician. Beginning in 1896, he emerged as a dominant force in the Democratic Party, running three times as the party's nominee for President ...

, a prominent bimetallist, the Populists also nominated Bryan but rejected the Democratic vice-presidential nominee in favor of party leader Thomas E. Watson. In the 1896 election, Bryan swept the South and West but lost to Republican William McKinley

William McKinley (January 29, 1843September 14, 1901) was the 25th president of the United States, serving from 1897 until his assassination in 1901. As a politician he led a realignment that made his Republican Party largely dominant in t ...

by a decisive margin.

After the 1896 presidential election, the Populist Party suffered a nationwide collapse. The party nominated presidential candidates in the three presidential elections after 1896, but none came close to matching Weaver's performance in 1892. Former Populists became inactive or joined other parties. Other than Debs and Bryan, few politicians associated with the Populists retained national prominence.

Historians see the Populists as a reaction to the power of corporate interests in the Gilded Age

In United States history, the Gilded Age was an era extending roughly from 1877 to 1900, which was sandwiched between the Reconstruction era and the Progressive Era. It was a time of rapid economic growth, especially in the Northern and We ...

, but they debate the degree to which the Populists were anti-modern and nativist. Scholars also continue to debate the magnitude of influence the Populists exerted on later organizations and movements, such as the progressives

Progressivism holds that it is possible to improve human societies through political action. As a political movement, progressivism seeks to advance the human condition through social reform based on purported advancements in science, techn ...

of the early 20th century. Most of the Progressives, such as Theodore Roosevelt, Robert La Follette, and Woodrow Wilson, were bitter enemies of the Populists. In American political rhetoric, "populist" was originally associated with the Populist Party and related left-wing movements, but beginning in the 1950s it began to take on a more generic meaning, describing any anti-establishment

An anti-establishment view or belief is one which stands in opposition to the conventional social, political, and economic principles of a society. The term was first used in the modern sense in 1958, by the British magazine '' New Statesman' ...

movement regardless of its position on the left–right political spectrum

The left–right political spectrum is a system of classifying political positions characteristic of left-right politics, ideologies and parties with emphasis placed upon issues of social equality and social hierarchy. In addition to positions ...

.

Origins

Third party antecedents

Ideologically, the Populist Party originated in the debate overmonetary policy

Monetary policy is the policy adopted by the monetary authority of a nation to control either the interest rate payable for very short-term borrowing (borrowing by banks from each other to meet their short-term needs) or the money supply, often ...

in the aftermath of the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by state ...

. In order to fund that war, the U.S. government had left the gold standard

A gold standard is a Backed currency, monetary system in which the standard economics, economic unit of account is based on a fixed quantity of gold. The gold standard was the basis for the international monetary system from the 1870s to the ...

by issuing fiat

Fiat Automobiles S.p.A. (, , ; originally FIAT, it, Fabbrica Italiana Automobili di Torino, lit=Italian Automobiles Factory of Turin) is an Italian automobile manufacturer, formerly part of Fiat Chrysler Automobiles, and since 2021 a subsidiary ...

paper currency known as Greenbacks. After the war, the Eastern financial establishment strongly favored a return to the gold standard for both ideological reasons (they believed that money must be backed by gold which, they argued, had intrinsic value) and economic gain (a return to the gold standard would make their government bonds more valuable). Successive presidential administrations favored "hard money" policies that retired the greenbacks, thereby shrinking the amount of currency in circulation. Financial interests also won passage of the Coinage Act of 1873

The Coinage Act of 1873 or Mint Act of 1873, was a general revision of laws relating to the Mint of the United States. By ending the right of holders of silver bullion to have it coined into standard silver dollars, while allowing holders of go ...

, which barred the coinage of silver, thereby ending a policy of bimetallism. The deflation caused by these policies affected farmers especially strongly, since deflation made it more difficult to pay debts and led to lower prices for agricultural products.

Angered by these developments, some farmers and other groups began calling for the government to permanently adopt fiat currency. These advocates of "soft money" were influenced by economist Edward Kellogg and Alexander Campbell, both of whom advocated for fiat money issued by a central bank

A central bank, reserve bank, or monetary authority is an institution that manages the currency and monetary policy of a country or monetary union,

and oversees their commercial banking system. In contrast to a commercial bank, a centra ...

. Despite fierce partisan rivalries, the two major parties were both closely allied with business interests and supported largely similar economic policies, including the gold standard. The Democratic Party Democratic Party most often refers to:

*Democratic Party (United States)

Democratic Party and similar terms may also refer to:

Active parties Africa

*Botswana Democratic Party

*Democratic Party of Equatorial Guinea

*Gabonese Democratic Party

*Demo ...

's 1868 platform endorsed the continued use of greenbacks, but the party embraced hard money policies after the 1868 election.

Though soft money forces were able to win some support in the West, launching a third party

Third party may refer to:

Business

* Third-party source, a supplier company not owned by the buyer or seller

* Third-party beneficiary, a person who could sue on a contract, despite not being an active party

* Third-party insurance, such as a Veh ...

proved difficult in the rest of the country. The United States was deeply polarized by the sectional politics of the post-Civil War era; most Northerners remained firmly attached to the Republican Party, while most Southerners identified with the Democratic Party. In the 1870s advocates of soft money formed the Greenback Party

The Greenback Party (known successively as the Independent Party, the National Independent Party and the Greenback Labor Party) was an American political party with an anti-monopoly ideology which was active between 1874 and 1889. The party ran ...

, which called for the continued use of paper money as well as the restoration of bimetallism.Reichley (2000), pp. 133–134 Greenback nominee James B. Weaver won over three percent of the vote in the 1880 presidential election, but the Greenback Party was unable to build a durable base of support, and it collapsed in the 1880s.Goodwyn (1978), pp. 18–19 Many former Greenback Party supporters joined the Union Labor Party, but it also failed to win widespread support.

Farmer's Alliance

A group of farmers formed theFarmers' Alliance

The Farmers' Alliance was an organized agrarian economic movement among American farmers that developed and flourished ca. 1875. The movement included several parallel but independent political organizations — the National Farmers' Alliance and ...

in Lampasas, Texas

Lampasas ( ) is a city in Lampasas County, Texas, United States. Its population was 7,291 at the 2020 census. It is the seat of Lampasas County.

Lampasas is part of the Killeen–Temple–Fort Hood metropolitan statistical area.

Histor ...

in 1877, and the organization quickly spread to surrounding counties. The Farmers' Alliance promoted collective economic action by farmers in order to cope with the crop-lien system The crop-lien system was a credit system that became widely used by cotton farmers in the United States in the South from the 1860s to the 1940s.

History

Sharecroppers and tenant farmers, who did not own the land they worked, obtained supplie ...

, which left economic power in the hands of a mercantile elite that furnished goods on credit. The movement became increasingly popular throughout Texas in the mid-1880s, and membership in the organization grew from 10,000 in 1884 to 50,000 at the end of 1885. At the same time, the Farmer's Alliance became increasingly politicized, with members attacking the "money trust" as the source and beneficiary of both the crop lien system and deflation. In the hopes of cementing an alliance with labor groups, the Farmer's Alliance supported the Knights of Labor

Knights of Labor (K of L), officially Noble and Holy Order of the Knights of Labor, was an American labor federation active in the late 19th century, especially the 1880s. It operated in the United States as well in Canada, and had chapters also ...

in the Great Southwest railroad strike of 1886. That same year, a Farmer's Alliance convention issued the Cleburne Demands, a series of resolutions that called for, among other things, collective bargaining, federal regulation of railroad rates, an expansionary monetary policy, and a national banking system administered by the federal government.

President Grover Cleveland

Stephen Grover Cleveland (March 18, 1837June 24, 1908) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 22nd and 24th president of the United States from 1885 to 1889 and from 1893 to 1897. Cleveland is the only president in American ...

's veto of a Texas seed bill in early 1887 outraged many farmers, encouraging the growth of a northern Farmer's Alliance in states like Kansas and Nebraska. That same year, a prolonged drought began in the West, contributing to the bankruptcy of many farmers. In 1887, the Farmer's Alliance merged with the Louisiana Farmers Union and expanded into the South and the Great Plains. In 1889, Charles Macune launched the ''National Economist

Charles William Macune (May 20, 1851 – November 3, 1940) was the head of the Southern Farmers' Alliance from 1886 to December 1889 and editor of its official organ, the ''National Economist,'' until 1892. He is remembered as the father of a f ...

'', which became the national paper of the Farmer's Alliance.

Macune and other Farmer's Alliance leaders helped organize a December 1889 convention in St. Louis

St. Louis () is the second-largest city in Missouri, United States. It sits near the confluence of the Mississippi and the Missouri Rivers. In 2020, the city proper had a population of 301,578, while the bi-state metropolitan area, which e ...

; the convention met with the goal of forming a confederation of the major farm and labor organizations. Though a full merger was not achieved, the Farmer's Alliance and the Knights of Labor jointly endorsed the St. Louis Platform, which included many of the long-standing demands of the Farmer's Alliance. The Platform added a call for Macune's " Sub-Treasury Plan," under which the federal government would establish warehouses in agricultural counties; farmers would be allowed to store their crops in these warehouses and borrow up to 80 percent of the value of their crops. The movement began to expand into the Northeast

The points of the compass are a set of horizontal, radially arrayed compass directions (or azimuths) used in navigation and cartography. A compass rose is primarily composed of four cardinal directions—north, east, south, and west—each sepa ...

and the Great Lakes region

The Great Lakes region of North America is a binational Canada, Canadian–United States, American region that includes portions of the eight U.S. states of Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Minnesota, New York (state), New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania ...

, while Macune led the establishment of the National Reform Press Association, a network of newspapers sympathetic to the Farmer's Alliance.

Formation

The Farmer's Alliance had initially sought to work within the two-party system, but by 1891 many party leaders had become convinced of the need for a third party that could challenge the conservatism of both major parties. In the

The Farmer's Alliance had initially sought to work within the two-party system, but by 1891 many party leaders had become convinced of the need for a third party that could challenge the conservatism of both major parties. In the 1890 elections

Year 189 ( CLXXXIX) was a common year starting on Wednesday (link will display the full calendar) of the Julian calendar. At the time, it was known as the Year of the Consulship of Silanus and Silanus (or, less frequently, year 942 ''Ab urbe ...

, Farmer's Alliance-backed candidates won dozens of races for the U.S. House of Representatives and gained majorities in several state legislatures. Many of these individuals were elected in coalition with Democrats; in Nebraska, the Farmer's Alliance forged an alliance with newly elected Congressman William Jennings Bryan

William Jennings Bryan (March 19, 1860 – July 26, 1925) was an American lawyer, orator and politician. Beginning in 1896, he emerged as a dominant force in the Democratic Party, running three times as the party's nominee for President ...

, while in Tennessee, local Farmer's Alliance leader John P. Buchanan was elected governor on the Democratic ticket. As most leading Democrats refused to endorse the Sub-Treasury, many leaders of the Farmer's Alliance remained dissatisfied with both major parties.

In December 1890, a Farmer's Alliance convention re-stated the organization's platform with the Ocala Demands

The Ocala Demands was a platform for economic and political reform that was later adopted by the People's Party.

In December, 1890, the National Farmers' Alliance and Industrial Union, more commonly known as the Southern Farmers' Alliance, its af ...

; Farmer's Alliance leaders also agreed to hold another convention in early 1892 to discuss the possibility of establishing a third party if Democrats failed to adopt their policy goals. Among those who favored the establishment of a third party were Farmer's Alliance president Leonidas L. Polk, Georgia newspaper editor Thomas E. Watson, and former Congressman Ignatius L. Donnelly of Minnesota.

The February 1892 Farmer's Alliance convention was attended by supporters of

The February 1892 Farmer's Alliance convention was attended by supporters of Edward Bellamy

Edward Bellamy (March 26, 1850 – May 22, 1898) was an American author, journalist, and political activist most famous for his utopian novel ''Looking Backward''. Bellamy's vision of a harmonious future world inspired the formation of numerou ...

and Henry George

Henry George (September 2, 1839 – October 29, 1897) was an American political economist and journalist. His writing was immensely popular in 19th-century America and sparked several reform movements of the Progressive Era. He inspired the ec ...

, as well as current and former members of the Greenback Party, Prohibition Party

The Prohibition Party (PRO) is a political party in the United States known for its historic opposition to the sale or consumption of alcoholic beverages and as an integral part of the temperance movement. It is the oldest existing third par ...

, Anti-Monopoly Party

The Anti-Monopoly Party was a short-lived American political party. The party nominated Benjamin F. Butler for President of the United States in 1884, as did the Greenback Party, which ultimately supplanted the organization.

Organizational hi ...

, Labor Reform Party, Union Labor Party, United Labor Party, Workingmen Party, and dozens of other minor parties. Delivering the final speech of the convention, Ignatius L. Donnelly, stated, "We meet in the midst of a nation brought to the verge of moral, political, and material ruin. ... We seek to restore the government of the republic to the hands of the 'plain people' with whom it originated. Our doors are open to all points of the compass. ... The interests of rural and urban labor are the same; their enemies are identical."Kazin (1995), pp. 27–29 Following Donnelly's speech, delegates agreed to establish the People's Party and hold a presidential nominating convention

A United States presidential nominating convention is a political convention held every four years in the United States by most of the political parties who will be fielding nominees in the upcoming U.S. presidential election. The formal purpo ...

on July 4 in Omaha, Nebraska

Omaha ( ) is the largest city in the U.S. state of Nebraska and the county seat of Douglas County, Nebraska, Douglas County. Omaha is in the Midwestern United States on the Missouri River, about north of the mouth of the Platte River. List of ...

. Journalists covering the fledgling party began referring to it as the "Populist Party," and that term quickly became widely popular.

1892 election

party platform

A political party platform (US English), party program, or party manifesto (preferential term in British & often Commonwealth English) is a formal set of principle goals which are supported by a political party or individual candidate, in order ...

known as the Omaha Platform, which proposed the implementation of the Sub-Treasury and other longtime Farmer's Alliance goals. The platform also called for a graduated income tax

An income tax is a tax imposed on individuals or entities (taxpayers) in respect of the income or profits earned by them (commonly called taxable income). Income tax generally is computed as the product of a tax rate times the taxable income. Tax ...

, direct election of Senators, a shorter workweek, restrictions on immigration to the United States

Immigration has been a major source of population growth and cultural change throughout much of the history of the United States. In absolute numbers, the United States has a larger immigrant population than any other country in the world, ...

, and public ownership of railroads and communication lines.

The Populists appealed most strongly to voters in the South, the Great Plains, and the Rocky Mountains. In the Rocky Mountains, Populist voters were motivated by support for free silver

Free silver was a major economic policy issue in the United States in the late 19th-century. Its advocates were in favor of an expansionary monetary policy featuring the unlimited coinage of silver into money on-demand, as opposed to strict adhe ...

(bimetallism), opposition to the power of railroads, and clashes with large landowners over water rights. In the South and the Great Plains, Populists had a broad appeal among farmers, but relatively little support in cities and towns. Businessmen and, to a lesser extent, skilled craftsmen were appalled by the perceived radicalism of Populist proposals. Even in rural areas, many voters resisted casting aside their long-standing partisan allegiances. Turner concludes that Populism appealed most strongly to economically distressed farmers who were isolated from urban centers. Linda Slaughter, a prominent women's rights advocate from the Dakota Territory

The Territory of Dakota was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from March 2, 1861, until November 2, 1889, when the final extent of the reduced territory was split and admitted to the Union as the states of ...

, also participated in the convention, making her the first American woman to vote for a presidential candidate at a national convention.

One of the Populist Party's central goals was to create a coalition between farmers in the South and West and urban laborers in the Midwest and Northeast. In the latter regions, the Populists received the support of union officials like Knights of Labor leader Terrence Powderly and railroad organizer Eugene V. Debs

Eugene Victor "Gene" Debs (November 5, 1855 – October 20, 1926) was an American socialist, political activist, trade unionist, one of the founding members of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), and five times the candidate of the Soc ...

, as well as author Edward Bellamy

Edward Bellamy (March 26, 1850 – May 22, 1898) was an American author, journalist, and political activist most famous for his utopian novel ''Looking Backward''. Bellamy's vision of a harmonious future world inspired the formation of numerou ...

's Nationalist Clubs. But the Populists lacked compelling campaign planks that appealed specifically to urban laborers, and were largely unable to mobilize support in urban areas. Corporate leaders had largely been successful in preventing labor from organizing politically and economically, and union membership did not rival that of the Farmer's Alliance. Some unions, including the fledgling American Federation of Labor

The American Federation of Labor (A.F. of L.) was a national federation of labor unions in the United States that continues today as the AFL-CIO. It was founded in Columbus, Ohio, in 1886 by an alliance of craft unions eager to provide mutua ...

, refused to endorse any political party. Populists were also largely unable to win the support of farmers in the Northeast and the more developed parts of the Midwest.

In the 1892 presidential election

The following elections occurred in the year 1892.

{{TOC right

Asia Japan

* 1892 Japanese general election

Europe Denmark

* 1892 Danish Folketing election

Portugal

* 1892 Portuguese legislative election

United Kingdom

* 1892 Chelmsford by-elec ...

, Democratic nominee Grover Cleveland

Stephen Grover Cleveland (March 18, 1837June 24, 1908) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 22nd and 24th president of the United States from 1885 to 1889 and from 1893 to 1897. Cleveland is the only president in American ...

, a strong supporter of the gold standard, defeated incumbent Republican President Benjamin Harrison

Benjamin Harrison (August 20, 1833March 13, 1901) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 23rd president of the United States from 1889 to 1893. He was a member of the Harrison family of Virginia–a grandson of the ninth pr ...

. Weaver won over one million votes, carried Colorado

Colorado (, other variants) is a state in the Mountain states, Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It encompasses most of the Southern Rocky Mountains, as well as the northeastern portion of the Colorado Plateau and the wes ...

, Kansas

Kansas () is a state in the Midwestern United States. Its capital is Topeka, and its largest city is Wichita. Kansas is a landlocked state bordered by Nebraska to the north; Missouri to the east; Oklahoma to the south; and Colorado to ...

, Idaho

Idaho ( ) is a state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. To the north, it shares a small portion of the Canada–United States border with the province of British Columbia. It borders the states of Montana and W ...

, and Nevada

Nevada ( ; ) is a state in the Western region of the United States. It is bordered by Oregon to the northwest, Idaho to the northeast, California to the west, Arizona to the southeast, and Utah to the east. Nevada is the 7th-most extensive, ...

, and received electoral votes from Oregon

Oregon () is a state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. The Columbia River delineates much of Oregon's northern boundary with Washington, while the Snake River delineates much of its eastern boundary with Idah ...

and North Dakota

North Dakota () is a U.S. state in the Upper Midwest, named after the indigenous Dakota Sioux. North Dakota is bordered by the Canadian provinces of Saskatchewan and Manitoba to the north and by the U.S. states of Minnesota to the east, S ...

. He was the first third-party candidate since the Civil War to win electoral votes, while Field was first Southern candidate to win electoral votes since the 1872 election. The Populists performed strongly in the West, but many party leaders were disappointed by the results in parts of the South and the entire Great Lakes Region. Weaver failed to win more than 5% of the vote in any state east of the Mississippi River and north of the Mason–Dixon line

The Mason–Dixon line, also called the Mason and Dixon line or Mason's and Dixon's line, is a demarcation line separating four U.S. states, forming part of the borders of Pennsylvania, Maryland, Delaware, and West Virginia (part of Virgini ...

.Reichley (2000), p. 138

Between presidential elections, 1893–1895

Shortly after Cleveland took office, the country fell into a deep recession known as thePanic of 1893

The Panic of 1893 was an economic depression in the United States that began in 1893 and ended in 1897. It deeply affected every sector of the economy, and produced political upheaval that led to the political realignment of 1896 and the pre ...

. In response, Cleveland and his Democratic allies repealed the Sherman Silver Purchase Act

The Sherman Silver Purchase Act was a United States federal law

enacted on July 14, 1890.Charles Ramsdell Lingley, ''Since the Civil War'', first edition: New York, The Century Co., 1920, ix–635 p., . Re-issued: Plain Label Books, unknown date, ...

and passed the Wilson–Gorman Tariff Act

The Revenue Act or Wilson-Gorman Tariff of 1894 (ch. 349, §73, , August 27, 1894) slightly reduced the United States tariff rates from the numbers set in the 1890 McKinley tariff and imposed a 2% tax on income over $4,000. It is named for W ...

, which provided for a minor reduction in tariff rates. The Populists denounced the Cleveland administration's continued adherence to the gold standard, and they angrily attacked the administration's decision to purchase gold from a syndicate led by J. P. Morgan

John Pierpont Morgan Sr. (April 17, 1837 – March 31, 1913) was an American financier and investment banker who dominated corporate finance on Wall Street throughout the Gilded Age. As the head of the banking firm that ultimately became know ...

. Millions fell into unemployment and poverty, and groups like Coxey's Army organized protest marches in Washington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

Party membership grew in several states; historian Lawrence Goodwyn estimates that in the mid-1890s the party had "a following of anywhere from 25 to 45 percent of the electorate in twenty-odd states." Partly due to the growing popularity of the Populist movement, the Democratic Congress included a provision to re-implement a federal income tax in the 1894 Wilson–Gorman Tariff Act

The Revenue Act or Wilson-Gorman Tariff of 1894 (ch. 349, §73, , August 27, 1894) slightly reduced the United States tariff rates from the numbers set in the 1890 McKinley tariff and imposed a 2% tax on income over $4,000. It is named for W ...

.Brands (2010), pp. 485–486

The Populists faced challenges from both the established major parties and the "Silverites," who generally disregarded the Omaha Platform in favor of bimetallism. These Silverites, who formed groups like the Silver Party

The Silver Party was a political party in the United States active from 1892 until 1911 and most successful in Nevada which supported a platform of bimetallism and free silver.

In 1892, several Silver Party candidates were elected to Nevada pub ...

and the Silver Republican Party

The Silver Republican Party, later known as the Lincoln Republican Party, was a United States political party from 1896 to 1901. It was so named because it split from the Republican Party by supporting free silver (effectively, expansionary monetar ...

, became particularly strong in Western mining states like Nevada and Colorado. In Colorado, Populists elected Davis Hanson Waite as governor, but the party divided over the Waite's refusal to break the Cripple Creek miners' strike of 1894

The Cripple Creek miners' strike of 1894 was a five-month strike by the Western Federation of Miners (WFM) in Cripple Creek, Colorado, United States. It resulted in a victory for the union and was followed in 1903 by the Colorado Labor Wars. It ...

. Silverites were also strong in Nebraska, where Democratic Congressman William Jennings Bryan continued to enjoy the support of many Nebraska Populists. A coalition of Democrats and Populists elected Populist William V. Allen to the Senate.Goodwyn (1978), pp. 215–218, 221–222

The 1894 elections

Events January–March

* January 4 – A military alliance is established between the French Third Republic and the Russian Empire.

* January 7 – William Kennedy Dickson receives a patent for motion picture film in the United St ...

were a massive defeat for the Democratic Party throughout the country, and a mixed result for the Populists. Populists performed poorly in the West and Midwest, where Republicans dominated, but won elections in Alabama and other states. In the aftermath, some party leaders, particularly those outside the South, became convinced of the need to fuse with Democrats and adopt bimetallism as the party's key issue. Party chairman Herman Taubeneck declared that the party should abandon the Omaha Platform and "unite the reform forces of the nation" behind bimetallism. Meanwhile, leading Democrats increasingly distanced themselves from Cleveland's gold standard policies in the aftermath of their performance in the 1894 elections.

The Populists became increasingly polarized between moderate "fusionists" like Taubeneck and radical "mid-roaders" (named for their desire to take a middle road between Democrats and Republicans) like Tom Watson. Fusionists believed the perceived radicalism of the Omaha Platform limited the party's appeal, whereas a platform based on free silver would resonate with a wide array of groups. The mid-roaders believed that free silver did not represent serious economic reform, and continued to call for government ownership of railroads, major changes to the financial system, and resistance to the influence of large corporations. One Texas Populist wrote that free silver would "leave undisturbed all the conditions which give rise to the undue concentration of wealth. The so-called silver party may prove a veritable Trojan Horse

The Trojan Horse was a wooden horse said to have been used by the Greeks during the Trojan War to enter the city of Troy and win the war. The Trojan Horse is not mentioned in Homer's ''Iliad'', with the poem ending before the war is concluded, ...

if we are not careful." In an attempt to get the party to repudiate the Omaha Platform in favor of free silver, Taubeneck called a party convention in December 1894. Rather than repudiating the Omaha Platform, the convention expanded it to include a call for the municipal ownership of public utilities.

Populist-Republican fusion in North Carolina

In 1894–1896 the Populist wave of agrarian unrest swept through the cotton and tobacco regions of the South. The most dramatic impact was in North Carolina, where the poor white farmers who comprised the Populist party formed a working coalition with the Republican Party, then largely controlled by blacks in the low country, and poor whites in the mountain districts. They took control of the state legislature in both 1894 and 1896, and the governorship in 1896. Restrictive rules on voting were repealed. In 1895 the legislature rewarded its black allies with patronage, naming 300 black magistrates in eastern districts, as well as deputy sheriffs and city policemen. They also received some federal patronage from the coalition congressman, and state patronage from the governor.Women and African Americans

Due to the prevailing racist attitudes of the late 19th century, any political alliance of Southern blacks and Southern whites was difficult to construct, but shared economic concerns allowed some transracial coalition building. After 1886, black farmers started organizing local agricultural groups along the lines the Farmer's Alliance advocated, and in 1888 the national Colored Alliance was established. Some southern Populists, including Watson, openly spoke of the need for poor blacks and poor whites to set aside their racial differences in the name of shared economic interests. The Populists followed theProhibition Party

The Prohibition Party (PRO) is a political party in the United States known for its historic opposition to the sale or consumption of alcoholic beverages and as an integral part of the temperance movement. It is the oldest existing third par ...

in actively including women in their affairs. But regardless of these appeals, racism did not evade the People's Party. Prominent Populist Party leaders such as Marion Butler at least partially demonstrated a dedication to the cause of white supremacy

White supremacy or white supremacism is the belief that white people are superior to those of other races and thus should dominate them. The belief favors the maintenance and defense of any power and privilege held by white people. White s ...

, and there appears to have been some support for this viewpoint in the party's rank-and-file membership. After 1900 Watson himself became an outspoken white supremacist.

Conspiratorial tendencies

Historians continue to debate the degree to which the Populists were bigoted against foreigners andJews

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""T ...

. Members of the anti-Catholic American Protective Association

The American Protective Association (APA) was an American anti-Catholic secret society established in 1887 by Protestants. The organization was the largest anti-Catholic movement in the United States during the later part of the 19th century, sho ...

were influential in California's Populist Party organization, and some Populists embraced the anti-Semitic conspiracy theory that the Rothschild family

The Rothschild family ( , ) is a wealthy Ashkenazi Jewish family originally from Frankfurt that rose to prominence with Mayer Amschel Rothschild (1744–1812), a court factor to the German Landgraves of Hesse-Kassel in the Free City of F ...

sought to control the United States.Reichley (2000), p. 142 Historian Hasia Diner

Hasia Diner

Hasia R. Diner is an American historian. Diner is the Paul S. and Sylvia Steinberg Professor of American Jewish History; Professor of Hebrew and Judaic Studies, History; Director of the Goldstein-Goren Center for American Jewish His ...

says:

: Some Populists believed that Jews made up a class of international financiers whose policies had ruined small family farms, they asserted, owned the banks and promoted the gold standard, the chief sources of their impoverishment. Agrarian radicalism posited the city as antithetical to American values, asserting that Jews were the essence of urban corruption.

Presidential election of 1896

In the lead-up to the

In the lead-up to the 1896 presidential election

The following elections occurred in 1896:

{{TOC right

North America

Canada

* 1896 Canadian federal election

* December 1896 Edmonton municipal election

* January 1896 Edmonton municipal election

* 1896 Manitoba general election

United States

* ...

, mid-roaders, fusionists, and free silver Democrats all maneuvered to put their favored candidates in the best position to win. Mid-roaders sought to ensure that the Populists would hold their national convention before that of the Democratic Party, thereby ensuring that they could not be accused of dividing "reform" forces.Goodwyn (1978), pp. 247–248 Defying those hopes, Taubeneck arranged for the 1896 Populist National Convention to take place one week after the 1896 Democratic National Convention

The 1896 Democratic National Convention, held at the Chicago Coliseum from July 7 to July 11, was the scene of William Jennings Bryan's nomination as the Democratic presidential candidate for the 1896 U.S. presidential election.

At age 36, Br ...

. Mid-roaders mobilized to defeat the fusionists; the ''Southern Mercury'' urged readers to nominate convention delegates who would "support the Omaha Platform in its entirety." As most of the party's high-ranking officeholders were fusionists, the mid-roaders faced difficulty in uniting around a candidate.

The 1896 Republican National Convention

The 1896 Republican National Convention was held in a temporary structure south of the St. Louis City Hall in Saint Louis, Missouri, from June 16 to June 18, 1896.

Former Governor William McKinley of Ohio was nominated for president on the fir ...

nominated William McKinley

William McKinley (January 29, 1843September 14, 1901) was the 25th president of the United States, serving from 1897 until his assassination in 1901. As a politician he led a realignment that made his Republican Party largely dominant in t ...

, a long-time Republican leader who was best known for leading the passage of 1890 McKinley Tariff

The Tariff Act of 1890, commonly called the McKinley Tariff, was an act of the United States Congress, framed by then Representative William McKinley, that became law on October 1, 1890. The tariff raised the average duty on imports to almost fift ...

. McKinley initially sought to downplay the gold standard in favor of campaigning on higher tariff rates, but he agreed to fully endorse the gold standard at the insistence of Republican donors and party leaders. Meeting later in the year, the 1896 Democratic National Convention

The 1896 Democratic National Convention, held at the Chicago Coliseum from July 7 to July 11, was the scene of William Jennings Bryan's nomination as the Democratic presidential candidate for the 1896 U.S. presidential election.

At age 36, Br ...

nominated William Jennings Bryan for president after Bryan's Cross of Gold speech

The Cross of Gold speech was delivered by William Jennings Bryan, a former United States Representative from Nebraska, at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago on July 9, 1896. In his address, Bryan supported "free silver" (i.e. bimet ...

galvanized the party behind free silver. For vice president, the party nominated conservative shipping magnate Arthur Sewall

Arthur Sewall (November 25, 1835 – September 5, 1900) was an American shipbuilder from Maine, best known as the Democratic nominee for Vice President of the United States in 1896, running mate to William Jennings Bryan. From 1888 to 1896 he ser ...

.

When the Populist convention met, fusionists proposed that the Populists nominate the Democratic ticket, while mid-roaders organized to defeat fusionist efforts. As Sewall was objectionable to many within the party, the mid-roaders successfully moved a motion to nominate the vice president first. Despite a telegram from Bryan indicating that he would not accept the Populist nomination if the party did not also nominate Sewall, the convention chose Tom Watson as the party's vice presidential nominee. The convention also reaffirmed the major planks of the 1892 platform and added support for initiatives and referendums. When the convention's presidential ballot began, it was still unclear whether Bryan would be nominated for president and whether Bryan would accept the nomination if offered. Mid-roaders put forward their own candidate, obscure newspaper editor S. F. Norton, but Norton was unable to win the support of many delegates. After a long and contentious series of roll call votes, Bryan won the Populist presidential nomination, taking 1042 votes to Norton's 321 votes.

Despite his earlier proclamation, Bryan accepted the Populist nomination. Facing a massive financial and organizational disadvantage, Bryan embarked on a campaign that took him across the country. He largely ignored major cities and the Northeast, instead focusing on the Midwest, which he hoped to win in conjunction with the Great Plains, the Far West, and the South.Reichley (2000), pp. 144–146 Watson, ostensibly Bryan's running mate, campaigned on a platform of "Straight Populism" and frequently attacked Sewall as an agent for "the banks and railroads." He delivered several speeches in Texas and the Midwest before returning to his home in Georgia for the remainder of the election.Goodwyn (1978), pp. 274–278

Ultimately, McKinley won a decisive majority of the electoral vote and became the first presidential candidate to win a majority of the popular vote since the 1876 presidential election. Bryan swept the old Populist strongholds in the West and South, and added the silverite states in the West, but did poorly in the industrial heartland. His strength was largely based on the traditional Democratic vote, but he lost many German Catholics and members of the middle class. Historians believe his defeat was partly attributable to the tactics Bryan used; he had aggressively "run" for president, while traditional candidates would use "front porch campaigns." The united opposition of nearly all business leaders and most religious leaders also hurt his candidacy, as did his poor showing among Catholic groups who were alienated by Bryan's emphasis on Protestant moral values.

Collapse

The Populist movement never recovered from the failure of 1896, and national fusion with the Democrats proved disastrous to the party. In the Midwest, the Populist Party essentially merged into the Democratic Party before the end of the 1890s. In the South, the National alliance with the Democrats sapped the Populists' ability to remain independent. Tennessee's Populist Party was demoralized by a diminishing membership, and puzzled and split by the dilemma of whether to fight the state-level enemy (the Democrats) or the national foe (the Republicans and

The Populist movement never recovered from the failure of 1896, and national fusion with the Democrats proved disastrous to the party. In the Midwest, the Populist Party essentially merged into the Democratic Party before the end of the 1890s. In the South, the National alliance with the Democrats sapped the Populists' ability to remain independent. Tennessee's Populist Party was demoralized by a diminishing membership, and puzzled and split by the dilemma of whether to fight the state-level enemy (the Democrats) or the national foe (the Republicans and Wall Street

Wall Street is an eight-block-long street in the Financial District of Lower Manhattan in New York City. It runs between Broadway in the west to South Street and the East River in the east. The term "Wall Street" has become a metonym for ...

). By 1900 the People's Party of Tennessee was a shadow of what it once was. A similar pattern repeated throughout the South, where the Populist Party had previously sought alliances with the Republican Party against the dominant state Democrats, including in Watson's Georgia.

In North Carolina, the state Democratic Party orchestrated a propaganda campaign in newspapers across the state, and created a brutal and violent white supremacy election campaign to defeat the North Carolina Populists and GOP, the Fusionist revolt in North Carolina collapsed in 1898, and white Democrats returned to power. The gravity of the crisis was underscored by a major race riot in Wilmington in 1898, two days after the election. Knowing they had just retaken control of the state legislature, the Democrats were confident they could not be overcome. They attacked and overcame the Fusionists; mobs roamed the black neighborhoods, shooting, killing, burning buildings, and making a special target of the black newspaper. There were no further insurgencies in any Southern states involving a successful black coalition at the state level. By 1900, the gains of the populist-Republican coalition were reversed, and the Democrats ushered in disfranchisement: practically all blacks lost their vote, and the Populist-Republican alliance fell apart.

In 1900

As of March 1 ( O.S. February 17), when the Julian calendar acknowledged a leap day and the Gregorian calendar did not, the Julian calendar fell one day further behind, bringing the difference to 13 days until February 28 ( O.S. February 15), ...

, many Populist voters supported Bryan again (though Marion Butler's home county of Sampson swung heavily to Republican McKinley in a backlash against the state Democratic party), but the weakened party nominated a separate ticket of Wharton Barker

Wharton Barker (May 1, 1846 – April 9, 1921) was an American financier and publicist who held influence in the Republican presidential selection during the 1880s and was a rival Populist presidential candidate in 1900.

Life

Wharton Barker was ...

and Ignatius L. Donnelly, and disbanded afterward. The prosperity of the first decade of the 1900s helped ensure that the party continued to fade away. Populist activists retired from politics, joined a major party, or followed Debs into the Socialist Party

Socialist Party is the name of many different political parties around the world. All of these parties claim to uphold some form of socialism, though they may have very different interpretations of what "socialism" means. Statistically, most of t ...

.

In 1904, the party was reorganized, and Watson was its nominee for president in 1904

Events

January

* January 7 – The distress signal ''CQD'' is established, only to be replaced 2 years later by ''SOS''.

* January 8 – The Blackstone Library is dedicated, marking the beginning of the Chicago Public Library system.

* ...

and 1908

Events

January

* January 1 – The British ''Nimrod'' Expedition led by Ernest Shackleton sets sail from New Zealand on the ''Nimrod'' for Antarctica.

* January 3 – A total solar eclipse is visible in the Pacific Ocean, and is the 4 ...

, after which the party disbanded again.

In ''A Preface to Politics'', published in 1913, Walter Lippmann

Walter Lippmann (September 23, 1889 – December 14, 1974) was an American writer, reporter and political commentator. With a career spanning 60 years, he is famous for being among the first to introduce the concept of Cold War, coining the t ...

wrote, "As I write, a convention of the Populist Party has just taken place. Eight delegates attended the meeting, which was held in a parlor." This may record the last gasp of the party organization.

Legacy

According to Gene Clanton's study of Kansas, populism and progressivism had a few similarities but different bases of support. Both opposed corruption and trusts. Populism emerged earlier and came out of the farm community. It was radically egalitarian in favor of the disadvantaged classes. It was weak in the towns and cities except in labor unions. Progressivism, on the other hand, was a later movement. It emerged after the 1890s from the urban business and professional communities. Most of its activists had opposed populism. It was elitist, and emphasized education and expertise. Its goals were to enhance efficiency, reduce waste, and enlarge the opportunities for upward social mobility. However, some former Populists changed their emphasis after 1900 and supported progressive reforms.Debate by historians

Since the 1890s historians have vigorously debated the nature of Populism. Some historians see the populists as forward-looking liberal reformers, others as reactionaries trying to recapture an idyllic and utopian past. For some they were radicals out to restructure American life, and for others they were economically hard-pressed agrarians seeking government relief. Much recent scholarship emphasizes Populism's debt to early Americanrepublicanism

Republicanism is a political ideology centered on citizenship in a state organized as a republic. Historically, it emphasises the idea of self-rule and ranges from the rule of a representative minority or oligarchy to popular sovereignty. It ...

. Clanton (1991) stresses that Populism was "the last significant expression of an old radical tradition that derived from Enlightenment sources that had been filtered through a political tradition that bore the distinct imprint of Jeffersonian, Jacksonian, and Lincolnian democracy." This tradition emphasized human rights over the cash nexus of the Gilded Age's dominant ideology.

Frederick Jackson Turner

Frederick Jackson Turner (November 14, 1861 – March 14, 1932) was an American historian during the early 20th century, based at the University of Wisconsin until 1910, and then Harvard University. He was known primarily for his frontier thes ...

and a succession of western historians depicted the Populist as responding to the closure of the frontier. Turner wrote:

: The Farmers' Alliance and the Populist demand for government ownership of the railroad is a phase of the same effort of the pioneer farmer, on his latest frontier. The proposals have taken increasing proportions in each region of Western Advance. Taken as a whole, Populism is a manifestation of the old pioneer ideals of the native American, with the added element of increasing readiness to utilize the national government to effect its ends.

The most influential Turner student of Populism was John D. Hicks, who emphasized economic pragmatism over ideals, presenting Populism as interest group politics, with have-nots demanding their fair share of America's wealth which was being leeched off by nonproductive speculators. Hicks emphasized the drought that ruined so many Kansas farmers, but also pointed to financial manipulations, deflation in prices caused by the gold standard, high interest rates, mortgage foreclosures, and high railroad rates. Corruption accounted for such outrages and Populists presented popular control of government as the solution, a point that later students of republicanism emphasized. In the 1930s, C. Vann Woodward

Comer Vann Woodward (November 13, 1908 – December 17, 1999) was an American historian who focused primarily on the American South and race relations. He was long a supporter of the approach of Charles A. Beard, stressing the influence of un ...

stressed the southern base, seeing the possibility of a black-and-white coalition of poor against the overbearing rich.

In the 1950s, scholars such as Richard Hofstadter

Richard Hofstadter (August 6, 1916October 24, 1970) was an American historian and public intellectual of the mid-20th century.

Hofstadter was the DeWitt Clinton Professor of American History at Columbia University. Rejecting his earlier histor ...

portrayed the Populist movement as an irrational response of backward-looking farmers to the challenges of modernity. Though Hofstadter wrote that the Populists were the "first modern political movement of practical importance in the United States to insist that the federal government had some responsibility for the common weal", he criticized the movement as anti-Semitic, conspiracy-minded, nativist, and grievance-based. According to Hofstadter, the antithesis of anti-modern Populism was the modernizing nature of Progressivism. Hofstadter noted that leading progressives like Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

, Robert La Follette Sr., George Norris and Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was an American politician and academic who served as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. A member of the Democratic Party, Wilson served as the president of P ...

were vehement enemies of Populism, though Bryan cooperated with them and accepted the Populist nomination in 1896. Reichley (1992) sees the Populist Party primarily as a reaction to the decline of the political hegemony of white Protestant farmers; the share of farmers in the workforce had fallen from about 70% in the early 1830s to about 33% in the 1890s. Reichley argues that, while the Populist Party was founded in reaction to economic hardship, by the mid-1890s it was "reacting not simply against the money power but against the whole world of cities and alien customs and loose living they felt was challenging the agrarian way of life."

Goodwyn (1976) and Postel (2007) reject the notion that the Populists were traditionalistic and anti-modern. Rather, they argue, the Populists aggressively sought self-consciously progressive goals. Goodwyn criticizes Hofstadter's reliance on secondary sources to characterize the Populists, working instead with material generated by the Populists themselves. Goodwyn determines that the farmers' cooperatives gave rise to a Populist culture, and their efforts to free farmers from lien merchants revealed to them the political structure of the economy, which propelled them into politics. The Populists sought diffusion of scientific and technical knowledge, formed highly centralized organizations, launched large-scale incorporated businesses, and pressed for an array of state-centered reforms. Hundreds of thousands of women committed to Populism, seeking a more modern life, education, and employment in schools and offices. A large section of the labor movement looked to Populism for answers, forging a political coalition with farmers that gave impetus to the regulatory state. Progress, however, was also menacing and inhumane, Postel notes. White Populists embraced social-Darwinist notions of racial improvement, Chinese exclusion and separate-but-equal.

Influence on later movements

Populist voters remained active in the electorate long after 1896, but historians continue to debate which party, if any, absorbed the largest share of them. In a case study of California Populists, historian Michael Magliari found that Populist voters influenced reform movements in California's Democratic Party and Socialist Party, but had a smaller impact on California's Republican Party. In 1990, historian William F. Holmes wrote, "an earlier generation of historians viewed Populism as the initiator of twentieth-century liberalism as manifested in Progressivism, but over the past two decades we have learned that fundamental differences separated the two movements." Most of the leading progressives (except Bryan) fiercely opposed Populism. Theodore Roosevelt, Norris, La Follette,William Allen White

William Allen White (February 10, 1868 – January 29, 1944) was an American newspaper editor, politician, author, and leader of the Progressive movement. Between 1896 and his death, White became a spokesman for middle America.

At a 1937 ...

and Wilson all strongly opposed Populism. It is debated whether any Populist ideas made their way into the Democratic Party during the New Deal era. The New Deal farm programs were designed by experts (like Henry A. Wallace

Henry Agard Wallace (October 7, 1888 – November 18, 1965) was an American politician, journalist, farmer, and businessman who served as the 33rd vice president of the United States, the 11th U.S. Secretary of Agriculture, and the 10th U.S. ...

) who had nothing to do with Populism. Michael Kazin

Michael Kazin (born June 6, 1948) is an American historian, and professor at Georgetown University. He is co-editor of '' Dissent'' magazine.

Early life

Kazin was born in New York City in 1948 and was raised in Englewood, New Jersey. He is the s ...

's ''The Populist Persuasion'' (1995) argues that Populism reflected a rhetorical style that manifested itself in spokesmen like Father Charles Coughlin

Charles Edward Coughlin ( ; October 25, 1891 – October 27, 1979), commonly known as Father Coughlin, was a Canadian-American Catholic priest based in the United States near Detroit. He was the founding priest of the National Shrine of the ...

in the 1930s and Governor George Wallace

George Corley Wallace Jr. (August 25, 1919 – September 13, 1998) was an American politician who served as the 45th governor of Alabama for four terms. A member of the Democratic Party, he is best remembered for his staunch segregationist an ...

in the 1960s.

Long after the dissolution of the Populist Party, other third parties, including a People's Party founded in 1971 and a Populist Party founded in 1984, took on similar names. These parties were not directly related to the Populist Party.

Populism as a generic term

In the United States, the term "populist" originally referred to the Populist Party and related left-wing movements of the late 19th century that wanted to curtail the power help I've been kidnaped of the corporate and financial establishment. Later the term "populist" began to apply to anyanti-establishment

An anti-establishment view or belief is one which stands in opposition to the conventional social, political, and economic principles of a society. The term was first used in the modern sense in 1958, by the British magazine '' New Statesman' ...

movement. The original generic definition of the term, which has held consistently since the emergence of its post-Populist Party genericness, describes a populist as "a believer in the rights, wisdom, or virtues of the common people." In the 21st century, the term once again began to be used. Politicians as diverse as independent left-wing Senator Bernie Sanders of Vermont and Republican President Donald Trump

Donald John Trump (born June 14, 1946) is an American politician, media personality, and businessman who served as the 45th president of the United States from 2017 to 2021.

Trump graduated from the Wharton School of the University of ...

have been labeled populists.

Electoral history and elected officials

Presidential tickets

Seats in Congress

Governors

*Colorado

Colorado (, other variants) is a state in the Mountain states, Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It encompasses most of the Southern Rocky Mountains, as well as the northeastern portion of the Colorado Plateau and the wes ...

: Davis Hanson Waite, 1893–1895

* Idaho

Idaho ( ) is a state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. To the north, it shares a small portion of the Canada–United States border with the province of British Columbia. It borders the states of Montana and W ...

: Frank Steunenberg, 1897–1901 ( fusion of Democrats and Populists)

* Kansas

Kansas () is a state in the Midwestern United States. Its capital is Topeka, and its largest city is Wichita. Kansas is a landlocked state bordered by Nebraska to the north; Missouri to the east; Oklahoma to the south; and Colorado to ...

: Lorenzo D. Lewelling, 1893–1895

* Kansas: John W. Leedy, 1897–1899

* Nebraska

Nebraska () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. It is bordered by South Dakota to the north; Iowa to the east and Missouri to the southeast, both across the Missouri River; Kansas to the south; Colorado to the so ...

: Silas A. Holcomb

Silas Alexander Holcomb (August 25, 1858 – April 25, 1920) was a Nebraska lawyer and politician elected as the ninth Governor of Nebraska and serving from 1895 to 1899. He ran under a fusion ticket between the Populist and the Democratic Par ...

, 1895–1899 (fusion of Democrats and Populists)

* Nebraska: William A. Poynter, 1899–1901 (fusion of Democrats and Populists)

* North Carolina

North Carolina () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States. The state is the 28th largest and 9th-most populous of the United States. It is bordered by Virginia to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, Georgia a ...

: Daniel Lindsay Russell

Daniel Lindsay Russell Jr. (August 7, 1845May 14, 1908) was the 49th Governor of North Carolina, serving from 1897 to 1901. An attorney, judge, and politician, he had also been elected as state representative and to the United States Congress, ...

, 1897–1901 (coalition of Republicans and Populists)

* Oregon

Oregon () is a state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. The Columbia River delineates much of Oregon's northern boundary with Washington, while the Snake River delineates much of its eastern boundary with Idah ...

: Sylvester Pennoyer

Sylvester Pennoyer (July 6, 1831May 30, 1902) was an American educator, attorney, and politician in Oregon. He was born in Groton, New York, attended Harvard Law School, and moved to Oregon at age 25. A Democrat, he served two terms as the eigh ...

, 1887–1895 (fusion of Democrats and Populists)

* South Dakota

South Dakota (; Sioux language, Sioux: , ) is a U.S. state in the West North Central states, North Central region of the United States. It is also part of the Great Plains. South Dakota is named after the Lakota people, Lakota and Dakota peo ...

: Andrew E. Lee, 1897–1901

* Tennessee

Tennessee ( , ), officially the State of Tennessee, is a landlocked state in the Southeastern region of the United States. Tennessee is the 36th-largest by area and the 15th-most populous of the 50 states. It is bordered by Kentucky to ...

: John P. Buchanan, 1891–1893

* Washington

Washington commonly refers to:

* Washington (state), United States

* Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States

** A metonym for the federal government of the United States

** Washington metropolitan area, the metropolitan area centered o ...

: John Rogers, 1897–1901 (fusion of Democrats and Populists)

Members of Congress

Approximately forty-five members of the party served in the U.S. Congress between 1891 and 1902. These included sixUnited States Senators

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and power ...

:

* William A. Peffer and William A. Harris from Kansas

Kansas () is a state in the Midwestern United States. Its capital is Topeka, and its largest city is Wichita. Kansas is a landlocked state bordered by Nebraska to the north; Missouri to the east; Oklahoma to the south; and Colorado to ...

* Marion Butler of North Carolina

North Carolina () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States. The state is the 28th largest and 9th-most populous of the United States. It is bordered by Virginia to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, Georgia a ...

* James H. Kyle from South Dakota

South Dakota (; Sioux language, Sioux: , ) is a U.S. state in the West North Central states, North Central region of the United States. It is also part of the Great Plains. South Dakota is named after the Lakota people, Lakota and Dakota peo ...

* Henry Heitfeld

Henry Heitfeld (January 12, 1859October 21, 1938) was an American politician. A Populist, he served as a United States Senator from Idaho.

Early life