United Australia Party on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The United Australia Party (UAP) was an Australian

The UAP was formed in 1931 by Labor dissidents and a conservative coalition as a response to the more radical economic proposals of Labor Party members to deal with the Great Depression in Australia. Lyons and Fenton's opposition to the economic policies of the Scullin Labor Government had attracted the support of a circle of socially prominent Melburnians known as "the Group" or "Group of Six", comprising stockbroker Staniforth Ricketson, insurance company president Charles Arthur Norris, metallurgist and businessman

The UAP was formed in 1931 by Labor dissidents and a conservative coalition as a response to the more radical economic proposals of Labor Party members to deal with the Great Depression in Australia. Lyons and Fenton's opposition to the economic policies of the Scullin Labor Government had attracted the support of a circle of socially prominent Melburnians known as "the Group" or "Group of Six", comprising stockbroker Staniforth Ricketson, insurance company president Charles Arthur Norris, metallurgist and businessman

Lyons favoured the tough economic measures of the "Premiers' Plan", pursued an orthodox fiscal policy and refused to accept NSW Premier Jack Lang's proposals to default on overseas debt repayments. A dramatic episode in Australian history followed Lyons' first electoral victory when NSW Premier Jack Lang refused to pay interest on overseas State debts. The Lyons government stepped in and paid the debts and then passed the Financial Agreement Enforcement Act to recover the money it had paid. In an effort to frustrate this move, Lang ordered State departments to pay all receipts directly to the Treasury instead of into Government bank accounts. The

Lyons favoured the tough economic measures of the "Premiers' Plan", pursued an orthodox fiscal policy and refused to accept NSW Premier Jack Lang's proposals to default on overseas debt repayments. A dramatic episode in Australian history followed Lyons' first electoral victory when NSW Premier Jack Lang refused to pay interest on overseas State debts. The Lyons government stepped in and paid the debts and then passed the Financial Agreement Enforcement Act to recover the money it had paid. In an effort to frustrate this move, Lang ordered State departments to pay all receipts directly to the Treasury instead of into Government bank accounts. The

Defence issues became increasingly dominant in public affairs with the rise of

Defence issues became increasingly dominant in public affairs with the rise of

The growing threat of war dominated politics through 1939. Menzies supported British policy against Hitler's Germany (negotiate for peace, but prepare for war) and – fearing Japanese intentions in the Pacific – established independent embassies in Tokyo and Washington to receive independent advice about developments. Menzies announced Australia's entry into World War Two on 3 September 1939 as a consequence of Nazi Germany's invasion of Poland. Australia was ill-prepared for war. A National Security Act was passed, the recruitment of a volunteer military force for service at home and abroad was announced, the

The growing threat of war dominated politics through 1939. Menzies supported British policy against Hitler's Germany (negotiate for peace, but prepare for war) and – fearing Japanese intentions in the Pacific – established independent embassies in Tokyo and Washington to receive independent advice about developments. Menzies announced Australia's entry into World War Two on 3 September 1939 as a consequence of Nazi Germany's invasion of Poland. Australia was ill-prepared for war. A National Security Act was passed, the recruitment of a volunteer military force for service at home and abroad was announced, the

Having spent all but eight months of its existence prior to 1941 in government, the UAP was ill-prepared for a role in opposition. Curtin proved a popular leader, rallying the nation in the face of the danger of invasion by the Japanese after Japan's entry into the war in December 1941. Even allowing for the advantages a sitting government has in wartime, the Labor government seemed more effective than its predecessor, while Fadden and Hughes were unable to get the better of Curtin. By the time the writs were issued for the 1943 federal election, the Coalition had sunk into a state of near paralysis, and at the election, suffered a landslide defeat, being reduced to only 23 seats nationwide, including 14 for the UAP.

After this election defeat, Menzies returned to the UAP leadership, and Fadden handed the post of opposition leader to him as well. However, as the Nationalists had a decade earlier, the party and its organisation now seemed moribund, particularly in NSW. UAP branches tended to become inactive between elections, and its politicians were seen as compromised by their reliance on large donations from business and financial organisations. In New South Wales, the party merged with the Commonwealth Party to form the

Having spent all but eight months of its existence prior to 1941 in government, the UAP was ill-prepared for a role in opposition. Curtin proved a popular leader, rallying the nation in the face of the danger of invasion by the Japanese after Japan's entry into the war in December 1941. Even allowing for the advantages a sitting government has in wartime, the Labor government seemed more effective than its predecessor, while Fadden and Hughes were unable to get the better of Curtin. By the time the writs were issued for the 1943 federal election, the Coalition had sunk into a state of near paralysis, and at the election, suffered a landslide defeat, being reduced to only 23 seats nationwide, including 14 for the UAP.

After this election defeat, Menzies returned to the UAP leadership, and Fadden handed the post of opposition leader to him as well. However, as the Nationalists had a decade earlier, the party and its organisation now seemed moribund, particularly in NSW. UAP branches tended to become inactive between elections, and its politicians were seen as compromised by their reliance on large donations from business and financial organisations. In New South Wales, the party merged with the Commonwealth Party to form the

Australian Dictionary of Biography – Joseph LyonsAustralian Dictionary of Biography – Robert MenziesAustralian Dictionary of Biography – Billy Hughes

{{New South Wales political parties Defunct political parties in Australia Political parties established in 1931 Political parties disestablished in 1945 1931 establishments in Australia 1945 disestablishments in Australia Australian Labor Party breakaway groups

political party

A political party is an organization that coordinates candidates to compete in a particular country's elections. It is common for the members of a party to hold similar ideas about politics, and parties may promote specific political ideology ...

that was founded in 1931 and dissolved in 1945. The party won four federal elections in that time, usually governing in coalition with the Country Party. It provided two prime ministers: Joseph Lyons

Joseph Aloysius Lyons (15 September 1879 – 7 April 1939) was an Australian politician who served as the 10th Prime Minister of Australia, in office from 1932 until his death in 1939. He began his career in the Australian Labor Party (ALP), ...

( 1932–1939) and Robert Menzies

The name Robert is an ancient Germanic given name, from Proto-Germanic "fame" and "bright" (''Hrōþiberhtaz''). Compare Old Dutch ''Robrecht'' and Old High German ''Hrodebert'' (a compound of '' Hruod'' ( non, Hróðr) "fame, glory, honou ...

( 1939–1941).

The UAP was created in the aftermath of the 1931 split in the Australian Labor Party

The Australian Labor Party (ALP), also simply known as Labor, is the major centre-left political party in Australia, one of two major parties in Australian politics, along with the centre-right Liberal Party of Australia. The party forms ...

. Six fiscally conservative Labor MPs left the party to protest the Scullin Government's financial policies during the Great Depression. Led by Joseph Lyons, a former Premier of Tasmania

The premier of Tasmania is the head of the executive government in the Australian state of Tasmania. By convention, the leader of the party or political grouping which has majority support in the House of Assembly is invited by the governor of T ...

, the defectors initially sat as independent

Independent or Independents may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Artist groups

* Independents (artist group), a group of modernist painters based in the New Hope, Pennsylvania, area of the United States during the early 1930s

* Independe ...

s, but then agreed to merge with the Nationalist Party and form a united opposition. Lyons was chosen as the new party's leader due to his popularity among the general public, with former Nationalist leader John Latham becoming his deputy. He led the UAP to a landslide victory at the 1931 federal election, where the party secured an outright majority in the House of Representatives

House of Representatives is the name of legislative bodies in many countries and sub-national entitles. In many countries, the House of Representatives is the lower house of a bicameral legislature, with the corresponding upper house often c ...

and was able to form government in its own right.

After the 1934 election, the UAP entered into a coalition with the Country Party; it retained government at the 1937 election

The following elections occurred in the year 1937.

Asia

* 1937 Philippine local elections

* 1937 Iranian legislative election

* 1937 Soviet Union legislative election

India

* 1937 Indian provincial elections

* 1937 Madras Presidency legislative ...

. After Lyons' death in April 1939, the UAP elected Robert Menzies as its new leader. This resulted in the Country Party leaving the coalition, but a new coalition agreement was reached in March 1940. The 1940 election resulted in a hung parliament

A hung parliament is a term used in legislatures primarily under the Westminster system to describe a situation in which no single political party or pre-existing coalition (also known as an alliance or bloc) has an absolute majority of legisl ...

and the formation of a minority government with support from two independents. In August 1941, Menzies was forced to resign as prime minister in favour of Arthur Fadden, the Country Party leader; he in turn survived only 40 days before losing a confidence motion and making way for a Labor government under John Curtin. Fadden continued on as Leader of the Opposition

The Leader of the Opposition is a title traditionally held by the leader of the largest political party not in government, typical in countries utilizing the parliamentary system form of government. The leader of the opposition is typically se ...

, with Billy Hughes

William Morris Hughes (25 September 1862 – 28 October 1952) was an Australian politician who served as the seventh prime minister of Australia, in office from 1915 to 1923. He is best known for leading the country Military history of Austra ...

replacing Menzies as UAP leader. Hughes resigned after the 1943 election, and Menzies subsequently returned as UAP leader and Leader of the Opposition. The UAP ceased to exist as a parliamentary party in February 1945, when its members joined the new Liberal Party of Australia

The Liberal Party of Australia is a centre-right political party in Australia, one of the two major parties in Australian politics, along with the centre-left Australian Labor Party. It was founded in 1944 as the successor to the United Aus ...

. The contemporary United Australia Party (2013)

The United Australia Party (UAP), formerly known as Clive Palmer's United Australia Party and the Palmer United Party (PUP), is a currently deregistered Australian political party formed by mining magnate Clive Palmer in April 2013. The part ...

has no connection or relationship with the former party.

History

Background

Joseph Lyons

Joseph Aloysius Lyons (15 September 1879 – 7 April 1939) was an Australian politician who served as the 10th Prime Minister of Australia, in office from 1932 until his death in 1939. He began his career in the Australian Labor Party (ALP), ...

began his political career as an Australian Labor Party

The Australian Labor Party (ALP), also simply known as Labor, is the major centre-left political party in Australia, one of two major parties in Australian politics, along with the centre-right Liberal Party of Australia. The party forms ...

politician and served as Premier of Tasmania

The premier of Tasmania is the head of the executive government in the Australian state of Tasmania. By convention, the leader of the party or political grouping which has majority support in the House of Assembly is invited by the governor of T ...

. Lyons was elected to the Australian Federal Parliament in 1929 and served in Prime Minister James Scullin's Labor Cabinet. Lyons became acting Treasurer in 1930 and helped negotiate the government's strategies for dealing with the Great Depression. With Scullin temporarily absent in London, Lyons and acting Prime Minister James Fenton

James is a common English language surname and given name:

*James (name), the typically masculine first name James

* James (surname), various people with the last name James

James or James City may also refer to:

People

* King James (disambiguat ...

clashed with the Labor Cabinet and Caucus over economic policy, and grappled with the differing proposals of the Premier's Plan, Lang Labor, the Commonwealth Bank and British adviser Otto Niemeyer.

While Health Minister Frank Anstey supported Premier of New South Wales

The premier of New South Wales is the head of government in the state of New South Wales

)

, nickname =

, image_map = New South Wales in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of New South Wales in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_ ...

Jack Lang's bid to default on debt repayments, Lyons advocated orthodox fiscal management. When Labor reinstated the more radical Ted Theodore

Edward Granville Theodore (29 December 1884 – 9 February 1950) was an Australian politician who served as Premier of Queensland from 1919 to 1925, as leader of the state Labor Party. He later entered federal politics, serving as Treasurer in ...

as Treasurer in 1931, Lyons and Fenton resigned from Cabinet.

Foundation

The UAP was formed in 1931 by Labor dissidents and a conservative coalition as a response to the more radical economic proposals of Labor Party members to deal with the Great Depression in Australia. Lyons and Fenton's opposition to the economic policies of the Scullin Labor Government had attracted the support of a circle of socially prominent Melburnians known as "the Group" or "Group of Six", comprising stockbroker Staniforth Ricketson, insurance company president Charles Arthur Norris, metallurgist and businessman

The UAP was formed in 1931 by Labor dissidents and a conservative coalition as a response to the more radical economic proposals of Labor Party members to deal with the Great Depression in Australia. Lyons and Fenton's opposition to the economic policies of the Scullin Labor Government had attracted the support of a circle of socially prominent Melburnians known as "the Group" or "Group of Six", comprising stockbroker Staniforth Ricketson, insurance company president Charles Arthur Norris, metallurgist and businessman John Michael Higgins

John Michael Higgins (born February 12, 1963) is an American actor and comedian whose film credits include Christopher Guest's mockumentaries, the role of David Letterman in HBO's ''The Late Shift'', and a starring role in the American vers ...

, writer Ambrose Pratt, state attorney-general Robert Menzies

The name Robert is an ancient Germanic given name, from Proto-Germanic "fame" and "bright" (''Hrōþiberhtaz''). Compare Old Dutch ''Robrecht'' and Old High German ''Hrodebert'' (a compound of '' Hruod'' ( non, Hróðr) "fame, glory, honou ...

, and architect Kingsley Henderson

Kingsley Anketell Henderson (15 December 1883 – 6 April 1942) was an Australian architect and businessman. He ran a successful firm in Melbourne that specialised in commercial buildings. He was involved in the creation of the United Australi ...

. In parliament on 13 March 1931, though still a member of the ALP, Lyons supported a no confidence motion against the Scullin Labor government. Soon afterward, Lyons, Fenton and four other right-wing Labor MPs-- Moses Gabb, Allan Guy, Charles McGrath

David Charles McGrath (10 November 1872 – 31 July 1934) was an Australian politician. Originally a member of the Australian Labor Party, he joined Joseph Lyons in the 1931 Labor split that led to the formation of the United Australia Party ...

and John Price—resigned from the ALP in protest of the Scullin government's economic policies. Five of the six Labor dissidents–all except Gabb–formed the '' All for Australia League'' and crossed over to the opposition benches. On 7 May, the All for Australia League, the Nationalist opposition (hitherto led by John Latham) and former Prime Minister Billy Hughes

William Morris Hughes (25 September 1862 – 28 October 1952) was an Australian politician who served as the seventh prime minister of Australia, in office from 1915 to 1923. He is best known for leading the country Military history of Austra ...

' Australian Party

The Australian Party was a political party founded and led by Billy Hughes after his expulsion from the Nationalist Party. The party was formed in 1929, and at its peak had four members of federal parliament. It was merged into the new Unit ...

(a group of former Nationalists who had been expelled for crossing the floor and bringing down Stanley Bruce

Stanley Melbourne Bruce, 1st Viscount Bruce of Melbourne, (15 April 1883 – 25 August 1967) was an Australian politician who served as the eighth prime minister of Australia from 1923 to 1929, as leader of the Nationalist Party.

Bor ...

's Nationalist government in 1929), merged to form the UAP. Although the new party was dominated by former Nationalists, Lyons was chosen as the new party's leader, and thus became Leader of the Opposition

The Leader of the Opposition is a title traditionally held by the leader of the largest political party not in government, typical in countries utilizing the parliamentary system form of government. The leader of the opposition is typically se ...

, with Latham as his deputy. The Western Australia

Western Australia (commonly abbreviated as WA) is a state of Australia occupying the western percent of the land area of Australia excluding external territories. It is bounded by the Indian Ocean to the north and west, the Southern Ocean to ...

branch of the Nationalists, however, retained the Nationalist name.

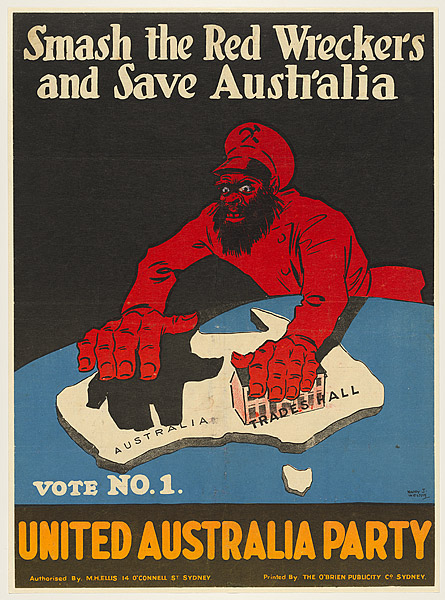

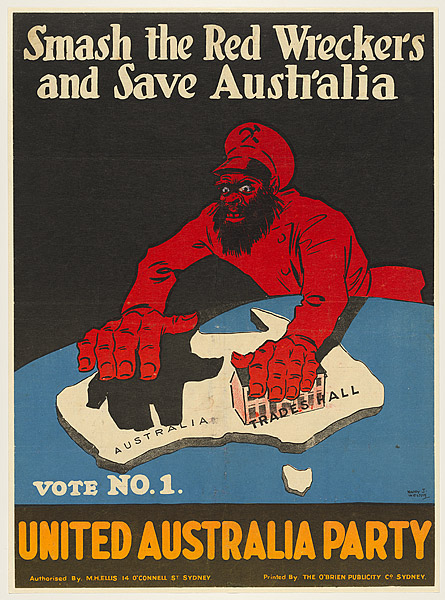

Claiming that the Scullin government was incapable of managing the economy, it offered traditional deflationary economic policies in response to Australia's economic crisis. Though it was basically an upper- and middle-class conservative party, the presence of ex-Labor MPs with working-class backgrounds allowed the party to present a convincing image of national unity transcending class barriers. This was especially true of the party leader, Lyons. Indeed, he had been chosen as the merged party's leader because he was thought to be more electorally appealing than the aloof Latham, and was thus better suited to win over traditional Labor supporters to the UAP. Its slogan was "All for Australia and the Empire".

A further split, this time of left-wing NSW Labor MPs who supported the unorthodox economic policies of NSW Premier Jack Lang, cost the Scullin government its parliamentary majority. In November 1931, Lang Labor dissidents broke with the Scullin government and joined with the UAP opposition to pass a no-confidence motion, forcing an early election.

Lyons Government

With the Labor Party split between Scullin's supporters and Langites, and with a very popular leader (Lyons had a genial manner and the common touch), the UAP won the elections in December 1931 in a massive landslide which saw the two wings of the Labor Party cut down to 18 seats between them, and Lyons becamePrime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is ...

in January 1932. He took office at the helm of a UAP majority government. The UAP initially hoped to renew the non-Labor Coalition with the Country Party of Earle Page after coming up four seats short of a majority in its own right. However, the five MPs elected from the Emergency Committee of South Australia, which stood in place of the UAP and Country Party in South Australia, joined the UAP party room, giving the UAP a bare majority of two seats. When negotiations with Page broke down, Lyons formed an exclusively UAP government. In 1934, the UAP lost six seats, forcing Lyons to take the Country Party into his government in a full-fledged Coalition.

The Lyons government followed the conservative economic policies it had promised in opposition, and benefited politically from the gradual worldwide economic recovery as the 1930s went on.

Response to Depression

Lyons favoured the tough economic measures of the "Premiers' Plan", pursued an orthodox fiscal policy and refused to accept NSW Premier Jack Lang's proposals to default on overseas debt repayments. A dramatic episode in Australian history followed Lyons' first electoral victory when NSW Premier Jack Lang refused to pay interest on overseas State debts. The Lyons government stepped in and paid the debts and then passed the Financial Agreement Enforcement Act to recover the money it had paid. In an effort to frustrate this move, Lang ordered State departments to pay all receipts directly to the Treasury instead of into Government bank accounts. The

Lyons favoured the tough economic measures of the "Premiers' Plan", pursued an orthodox fiscal policy and refused to accept NSW Premier Jack Lang's proposals to default on overseas debt repayments. A dramatic episode in Australian history followed Lyons' first electoral victory when NSW Premier Jack Lang refused to pay interest on overseas State debts. The Lyons government stepped in and paid the debts and then passed the Financial Agreement Enforcement Act to recover the money it had paid. In an effort to frustrate this move, Lang ordered State departments to pay all receipts directly to the Treasury instead of into Government bank accounts. The New South Wales Governor

The governor of New South Wales is the viceregal representative of the Australian monarch, King Charles III, in the state of New South Wales. In an analogous way to the governor-general of Australia at the national level, the governors of the A ...

, Sir Philip Game, intervened on the basis that Lang had acted illegally in breach of the state Audit Act and sacked the Lang Government, who then suffered a landslide loss at the consequent 1932 state election.Brian Carroll; '' From Barton to Fraser''; Cassell Australia; 1978

Australia entered the Depression with a debt crisis and a credit crisis. According to author Anne Henderson of the Sydney Institute, Lyons held a steadfast belief in "the need to balance budgets, lower costs to business and restore confidence" and the Lyons period gave Australia "stability and eventual growth" between the drama of the Depression and the outbreak of the Second World War. A lowering of wages was enforced and industry tariff protections maintained, which together with cheaper raw materials during the 1930s saw a shift from agriculture to manufacturing as the chief employer of the Australian economy – a shift which was consolidated by increased investment by the commonwealth government into defence and armaments manufacture. Lyons saw restoration of Australia's exports as the key to economic recovery. A devalued Australian currency assisted in restoring a favourable balance of trade. Tariffs had been a point of difference between the Country Party and United Australia Party. The CP opposed high tariffs because they increased costs for farmers, while the UAP had support among manufacturers who supported tariffs. Lyons was therefore happy to be perceived as "protectionist". Australia agreed to give tariff preference to British Empire goods, following the 1932 Imperial economic conference. The Lyons Government lowered interest rates to stimulate expenditure. Another point of difference was the issue of establishing national unemployment insurance. Debate on this issue became strained with the Country Party opposing the plan. On this issue, deputy leader Robert Menzies and Country Party leader Earle Page would have a public falling out.

According to author Brian Carroll, Lyons had been underestimated when he assumed office in 1932 and as leader he demonstrated: "a combination of honesty, native shrewdness, tact, administrative ability, common sense, good luck and good humour that kept him in the job longer than any previous Prime Minister except Hughes". Lyons was assisted in his campaigning by his politically active wife, Enid Lyons. She had a busy official role from 1932 to 1939 and, following her husband's death, stood for Parliament herself, becoming Australia's first female Member of the House of Representatives, and later first woman in Cabinet, joining the Menzies Cabinet in 1951.

Preparation for war

Defence issues became increasingly dominant in public affairs with the rise of

Defence issues became increasingly dominant in public affairs with the rise of fascism

Fascism is a far-right, authoritarian, ultra-nationalist political ideology and movement,: "extreme militaristic nationalism, contempt for electoral democracy and political and cultural liberalism, a belief in natural social hierarchy and th ...

in Europe and militant Japan in Asia. The UAP largely supported the western powers in their policy of appeasement, however veteran UAP minister Billy Hughes was an exception and he embarrassed the government with his 1935 book ''Australia and the War Today'' which exposed a lack of preparation in Australia for what Hughes correctly supposed to be a coming war. Hughes was forced to resign, but the Lyons government tripled its defence budget.Brian Carroll; From Barton to Fraser; Cassell Australia; 1978

On 7 April 1939, with the storm clouds of the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

gathering in Europe and the Pacific, Joseph Lyons became the first Prime Minister of Australia to die in office. Driving from Canberra to Sydney, en route to his home in Tasmania for Easter, he suffered a heart attack, dying soon after in hospital in Sydney, on Good Friday. The UAP's Deputy leader, Robert Menzies, had resigned in March, citing the coalition's failure to implement a plan for national insurance. In the absence of a UAP deputy, the Governor-General, Lord Gowrie, appointed Country Party leader Sir Earle Page as his temporary replacement, pending the selection of Lyons' successor by the UAP.

Menzies Government

Robert Menzies

The name Robert is an ancient Germanic given name, from Proto-Germanic "fame" and "bright" (''Hrōþiberhtaz''). Compare Old Dutch ''Robrecht'' and Old High German ''Hrodebert'' (a compound of '' Hruod'' ( non, Hróðr) "fame, glory, honou ...

defeated Hughes for the UAP leadership and became Prime Minister on 26 April 1939. Page refused to serve under Menzies, leaving the UAP with a minority government.

In addition to the office of Prime Minister, Menzies served as Treasurer. The First Menzies Ministry included the ageing former Prime Minister Billy Hughes and the young future Prime Minister Harold Holt

Harold Edward Holt (5 August 190817 December 1967) was an Australian politician who served as the 17th prime minister of Australia from 1966 until his presumed death in 1967. He held office as leader of the Liberal Party.

Holt was born in ...

. Menzies tried and failed to have the issue of national insurance examined by a committee of parliamentarians. Though no longer in formal coalition, his government survived because the Country Party preferred a UAP government to that of a Labor government.

World War II

The growing threat of war dominated politics through 1939. Menzies supported British policy against Hitler's Germany (negotiate for peace, but prepare for war) and – fearing Japanese intentions in the Pacific – established independent embassies in Tokyo and Washington to receive independent advice about developments. Menzies announced Australia's entry into World War Two on 3 September 1939 as a consequence of Nazi Germany's invasion of Poland. Australia was ill-prepared for war. A National Security Act was passed, the recruitment of a volunteer military force for service at home and abroad was announced, the

The growing threat of war dominated politics through 1939. Menzies supported British policy against Hitler's Germany (negotiate for peace, but prepare for war) and – fearing Japanese intentions in the Pacific – established independent embassies in Tokyo and Washington to receive independent advice about developments. Menzies announced Australia's entry into World War Two on 3 September 1939 as a consequence of Nazi Germany's invasion of Poland. Australia was ill-prepared for war. A National Security Act was passed, the recruitment of a volunteer military force for service at home and abroad was announced, the 2nd Australian Imperial Force

The Second Australian Imperial Force (2nd AIF, or Second AIF) was the name given to the volunteer expeditionary force of the Australian Army in the Second World War. It was formed following the declaration of war on Nazi Germany, with an initial ...

, and a citizen militia was organised for local defence.

Troubled by Britain's failure to increase defences at Singapore, Menzies was cautious in committing troops to Europe, nevertheless in 1940–41, Australian forces played prominent roles in the fighting in the Mediterranean theatre.

A special War Cabinet was created;– initially composed of Menzies and five senior ministers ( RG Casey, GA Street, Senator McLeay, HS Gullet and World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

Prime Minister Billy Hughes). In January 1940, Menzies dispatched potential leadership rival Richard Casey to Washington as Australia's first "Minister to the United States". In a consequent by-election, the UAP suffered a heavy defeat and Menzies re-entered coalition negotiations with the Country Party. In March 1940, troubled negotiations were concluded with the Country Party to re-enter Coalition with the UAP. The replacement of Earle Page as leader by Archie Cameron allowed Menzies to reach accommodation. A new Coalition ministry was formed including a number of Country Party members.

With the 1940 election looming, Menzies lost his Chief of the General Staff and three loyal ministers in the Canberra air disaster

The 1940 Canberra air disaster was an aircraft crash that occurred near Canberra, the capital of Australia, on 13 August 1940, during World War II. All ten people on board were killed: six passengers, including three members of the Australian ...

. The Labor Party meanwhile experienced a split along pro and anti Communist lines over policy towards the Soviet Union for its co-operation with Nazi Germany in the invasion of Poland; this resulted in the formation of the Non-Communist Labor Party. The Communist Party of Australia (CPA) opposed and sought to disrupt Australia's war effort. Menzies banned the CPA after the fall of France in 1940, but by 1941 Stalin was forced to join the allied cause when Hitler reneged on the Pact and invaded the USSR. The USSR came to bear the brunt of the carnage of Hitler's war machine and the Communist Party in Australia lost its early war stigma as a result.

At the general election in September 1940, there was a large swing to Labor and the UAP-Country Party coalition lost its majority, continuing in office only because of the support of two independent MPs, Arthur Coles and Alexander Wilson. The UAP–Country Party coalition and the Labor parties won 36 seats each. Menzies proposed an all party unity government to break the impasse, but the Labor Party under John Curtin refused to join. Curtin agreed instead to take a seat on a newly created Advisory War Council in October 1940. New Country Party leader Arthur Fadden became Treasurer and Menzies unhappily conceded to allow Earle Page back into his ministry.

In January 1941, Menzies flew to Britain to discuss the weakness of Singapore's defences and sat with Winston Churchill's British War Cabinet. En route he inspected Singapore's defences – finding them alarmingly inadequate – and visited Australian troops in the Mid-East. He at times clashed with Churchill in the War Cabinet, and was unable to achieve significant assurances for increased commitment to Singapore's defences, but undertook morale boosting excursions to war affected cities and factories and was well received by the British press and generally raised awareness in Britain of Australia's contribution to its war effort. He returned to Australia via Canada and the United States – addressing the Canadian parliament and lobbying President Roosevelt for more arms production. After four months, Menzies returned to Australia to face a lack of enthusiasm for his global travels and a war-time minority government under ever increasing strain.

In Menzies's absence, Curtin had co-operated with Fadden in preparing Australia for the expected Pacific War. With the threat of Japan imminent and with the Australian army suffering badly in the Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

and Crete

Crete ( el, Κρήτη, translit=, Modern: , Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the 88th largest island in the world and the fifth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, Sardinia, Cypru ...

campaigns, Menzies re-organised his ministry and announced multiple multi-party committees to advise on war and economic policy. Government critics however called for an all-party government.

Menzies' resignation

In August, Cabinet decided that Menzies should travel back to Britain to represent Australia in the War Cabinet – but this time the Labor caucus refused to support the plan. Menzies announced to his Cabinet that he thought he should resign and advise the Governor General to invite Curtin to form Government. The Cabinet instead insisted he approach Curtin again to form a war cabinet. Unable to secure Curtin's support, and with an unworkable parliamentary majority, Menzies faced continuing problems with the administration of the war effort and the undermining of his leadership by members of his own coalition. Menzies resigned as prime minister on 29 August 1941, but initially stayed on as UAP leader.Fadden Government

Following Menzies' resignation, a joint UAP–Country Party meeting chose Fadden to be his successor as prime minister, even though the Country Party was the junior partner in the coalition. Menzies became Minister for Defence Co-ordination. Australia marked two years of war on 7 September 1941 with a day of prayer, on which Prime Minister Fadden broadcast to the nation an exhortation to be united in the ‘supreme task of defeating the forces of evil in the world". With the Pacific on the brink of war, Opposition leader John Curtin offered friendship and co-operation to Fadden, but refused to join in an all-party wartime national government. Coles and Wilson were angered at how Menzies had been treated, and on 3 October voted with the Opposition in the House of Representatives to reject Fadden's budget; Fadden promptly resigned. This became a rare moment in Parliament in which a sitting government is defeated in the House. This did not occur in Australia again for another 78 years. Under the prodding ofGovernor-General

Governor-general (plural ''governors-general''), or governor general (plural ''governors general''), is the title of an office-holder. In the context of governors-general and former British colonies, governors-general are appointed as viceroy t ...

Lord Gowrie, who wanted to avoid calling an election given the dangerous international situation, Coles and Wilson threw their support to Labor. Gowrie then duly swore Curtin in as prime minister on 7 October 1941. Eight weeks later, Japan attacked Pearl Harbor

The attack on Pearl HarborAlso known as the Battle of Pearl Harbor was a surprise military strike by the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service upon the United States against the naval base at Pearl Harbor in Honolulu, Territory of Hawaii, ...

.

On 9 October, Menzies resigned as UAP leader, but not before calling for a partyroom meeting to determine whether the party should form a united opposition with the Country Party or go it alone. His preferred option was the latter, and he had intended to re-contest the leadership if he was successful. However, the party voted 19–12 to form a united opposition under the leadership of Fadden. Although the UAP had been in government for a decade, Menzies' resignation revealed a party almost completely bereft of leadership. With no obvious successor to Menzies, the UAP was forced to turn to the 79-year-old former prime minister Billy Hughes

William Morris Hughes (25 September 1862 – 28 October 1952) was an Australian politician who served as the seventh prime minister of Australia, in office from 1915 to 1923. He is best known for leading the country Military history of Austra ...

as its new leader. With Menzies out and the aged Hughes seen as a stop-gap leader, UAP members jostled for position.

Demise of the party

Having spent all but eight months of its existence prior to 1941 in government, the UAP was ill-prepared for a role in opposition. Curtin proved a popular leader, rallying the nation in the face of the danger of invasion by the Japanese after Japan's entry into the war in December 1941. Even allowing for the advantages a sitting government has in wartime, the Labor government seemed more effective than its predecessor, while Fadden and Hughes were unable to get the better of Curtin. By the time the writs were issued for the 1943 federal election, the Coalition had sunk into a state of near paralysis, and at the election, suffered a landslide defeat, being reduced to only 23 seats nationwide, including 14 for the UAP.

After this election defeat, Menzies returned to the UAP leadership, and Fadden handed the post of opposition leader to him as well. However, as the Nationalists had a decade earlier, the party and its organisation now seemed moribund, particularly in NSW. UAP branches tended to become inactive between elections, and its politicians were seen as compromised by their reliance on large donations from business and financial organisations. In New South Wales, the party merged with the Commonwealth Party to form the

Having spent all but eight months of its existence prior to 1941 in government, the UAP was ill-prepared for a role in opposition. Curtin proved a popular leader, rallying the nation in the face of the danger of invasion by the Japanese after Japan's entry into the war in December 1941. Even allowing for the advantages a sitting government has in wartime, the Labor government seemed more effective than its predecessor, while Fadden and Hughes were unable to get the better of Curtin. By the time the writs were issued for the 1943 federal election, the Coalition had sunk into a state of near paralysis, and at the election, suffered a landslide defeat, being reduced to only 23 seats nationwide, including 14 for the UAP.

After this election defeat, Menzies returned to the UAP leadership, and Fadden handed the post of opposition leader to him as well. However, as the Nationalists had a decade earlier, the party and its organisation now seemed moribund, particularly in NSW. UAP branches tended to become inactive between elections, and its politicians were seen as compromised by their reliance on large donations from business and financial organisations. In New South Wales, the party merged with the Commonwealth Party to form the Democratic Party Democratic Party most often refers to:

*Democratic Party (United States)

Democratic Party and similar terms may also refer to:

Active parties Africa

*Botswana Democratic Party

*Democratic Party of Equatorial Guinea

*Gabonese Democratic Party

*Demo ...

, which merged with the Liberal Democratic Party the following year. In Queensland the state branch was absorbed into the Queensland People's Party.

Menzies became convinced that the UAP was no longer viable, and a new anti-Labor party needed to be formed to replace it. He circulated a confidential memorandum expressing his wish for the UAP to be replaced:

The name United Australia Party has fallen into complete disregard. It no longer means anything. Many of my own strongest supporters in my own electorate decline to have anything to do with the Party as such. ..To establish a new party under a new name, it is, I think, essential to recognise that the new groups and movements which sprang up in the six months before the election were all expressions of dissatisfaction with the existing set-up. ..The time between now and the next election is already beginning to run out!On 31 August 1945, the UAP was absorbed into the newly formed

Liberal Party of Australia

The Liberal Party of Australia is a centre-right political party in Australia, one of the two major parties in Australian politics, along with the centre-left Australian Labor Party. It was founded in 1944 as the successor to the United Aus ...

, with Menzies as its leader. The new party was dominated by former UAP members; with a few exceptions, the UAP party room became the Liberal party room.

The Liberal Party went on to become the dominant centre-right party in Australian politics. After an initial loss to Labor at the 1946 election, Menzies led the new non-Labor Coalition (of the Liberal and Country parties) to victory at the 1949 election, defeating the incumbent Labor government led by Curtin's successor, Ben Chifley

Joseph Benedict Chifley (; 22 September 1885 – 13 June 1951) was an Australian politician who served as the 16th prime minister of Australia from 1945 to 1949. He held office as the leader of the Australian Labor Party (ALP) from 1945, follo ...

. The Coalition stayed in office for a record 23 years.

Electoral performance

Note: the United Australia Party did not run candidates in South Australia in 1931. The Emergency Committee of South Australia was the main anti-Labor party, but five MPs elected under that banner joined the parliamentary UAP after the election.Leaders

Party leaders

Party deputy leaders

Notes

References

Further reading

* * * * * * * *External links

Australian Dictionary of Biography – Joseph Lyons

{{New South Wales political parties Defunct political parties in Australia Political parties established in 1931 Political parties disestablished in 1945 1931 establishments in Australia 1945 disestablishments in Australia Australian Labor Party breakaway groups