United Airlines Flight 718 on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Grand Canyon mid-air collision occurred in the western

At about 10:30 a.m. the two aircraft collided over the canyon at an angle of about 25 degrees. Post-crash analysis determined that the United DC-7 was banking to the right and pitching down at the time of the collision, suggesting that one or possibly both of the United pilots spotted the TWA Constellation and attempted evasive action.

The DC-7's upraised left wing clipped the top of the Constellation's

At about 10:30 a.m. the two aircraft collided over the canyon at an angle of about 25 degrees. Post-crash analysis determined that the United DC-7 was banking to the right and pitching down at the time of the collision, suggesting that one or possibly both of the United pilots spotted the TWA Constellation and attempted evasive action.

The DC-7's upraised left wing clipped the top of the Constellation's  The separation of the tail assembly from the Constellation resulted in immediate loss of control, causing the aircraft to enter a near-vertical, terminal velocity dive. Plunging into the Grand Canyon at an estimated speed of more than , the Constellation slammed into the north slope of a ravine on the northeast slope of Temple Butte and disintegrated on impact, instantly killing all aboard. An intense fire, fueled by

The separation of the tail assembly from the Constellation resulted in immediate loss of control, causing the aircraft to enter a near-vertical, terminal velocity dive. Plunging into the Grand Canyon at an estimated speed of more than , the Constellation slammed into the north slope of a ravine on the northeast slope of Temple Butte and disintegrated on impact, instantly killing all aboard. An intense fire, fueled by

However, upon hearing of the missing airliners, Palen decided that what he had seen might have been smoke from a post-crash fire. He and his brother flew a light aircraft (a

However, upon hearing of the missing airliners, Palen decided that what he had seen might have been smoke from a post-crash fire. He and his brother flew a light aircraft (a  The airlines hired the Swiss Air-Rescue and some Swiss mountain climbers to go to the scene where the aircraft fuselages had crashed. They were to gather the remains of the passengers and their personal effects. This was given considerable publicity in U.S. news releases at the time because of the ruggedness of the terrain where the fuselages came to rest.

Owing to the great violence of the impacts, no bodies were recovered intact and positive identification of most of the remains was not possible. On July 9, 1956, a mass funeral for the victims of TWA Flight 2 was held at the canyon's south rim. Twenty-nine unidentified victims of the United flight were interred in four coffins at the

The airlines hired the Swiss Air-Rescue and some Swiss mountain climbers to go to the scene where the aircraft fuselages had crashed. They were to gather the remains of the passengers and their personal effects. This was given considerable publicity in U.S. news releases at the time because of the ruggedness of the terrain where the fuselages came to rest.

Owing to the great violence of the impacts, no bodies were recovered intact and positive identification of most of the remains was not possible. On July 9, 1956, a mass funeral for the victims of TWA Flight 2 was held at the canyon's south rim. Twenty-nine unidentified victims of the United flight were interred in four coffins at the

Alternate URL

wit

PDF

* *

by Jon Proctor

by Gregory Rawlins

Arizona Aircraft Archaeology

What Caused The "Worst Accident In The History" Of Commercial Aviation?

Mayday: Air Disaster - YouTube Channel {{DEFAULTSORT:Grand Canyon mid-air collision, 1956 Airliner accidents and incidents in Arizona Aviation accidents and incidents in the United States in 1956 History of air traffic control History of Coconino County, Arizona Trans World Airlines accidents and incidents United Airlines accidents and incidents 1956 in Arizona Disasters in Arizona Burials in Arizona Grand Canyon Accidents and incidents involving the Douglas DC-7 Accidents and incidents involving the Lockheed Constellation Airliner accidents and incidents caused by pilot error Mid-air collisions Mid-air collisions involving airliners National Historic Landmarks in Arizona National Register of Historic Places in Coconino County, Arizona June 1956 events in the United States 1956 in the United States

United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

on Saturday, June 30, 1956, when a United Airlines

United Airlines, Inc. (commonly referred to as United), is a major American airline headquartered at the Willis Tower in Chicago, Illinois.

Douglas DC-7 struck a Trans World Airlines

Trans World Airlines (TWA) was a major American airline which operated from 1930 until 2001. It was formed as Transcontinental & Western Air to operate a route from New York City to Los Angeles via St. Louis, Kansas City, and other stops, with F ...

Lockheed L-1049 Super Constellation over Grand Canyon National Park

Grand Canyon National Park, located in northwestern Arizona, is the 15th site in the United States to have been named as a national park. The park's central feature is the Grand Canyon, a gorge of the Colorado River, which is often consider ...

, Arizona

Arizona ( ; nv, Hoozdo Hahoodzo ; ood, Alĭ ṣonak ) is a state in the Southwestern United States. It is the 6th largest and the 14th most populous of the 50 states. Its capital and largest city is Phoenix. Arizona is part of the Fou ...

. All 128 on board both airplanes perished, making it the first commercial airline incident to exceed one hundred fatalities. The airplanes had departed Los Angeles International Airport

Los Angeles International Airport , commonly referred to as LAX (with each letter pronounced individually), is the primary international airport serving Los Angeles, California and its surrounding metropolitan area. LAX is located in the W ...

minutes apart for Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name ...

and Kansas City

The Kansas City metropolitan area is a bi-state metropolitan area anchored by Kansas City, Missouri. Its 14 counties straddle the border between the U.S. states of Missouri (9 counties) and Kansas (5 counties). With and a population of more ...

, respectively.

The collision took place in uncontrolled airspace, where it was the pilots' responsibility to maintain separation

Separation may refer to:

Films

* ''Separation'' (1967 film), a British feature film written by and starring Jane Arden and directed by Jack Bond

* ''La Séparation'', 1994 French film

* ''A Separation'', 2011 Iranian film

* ''Separation'' (20 ...

("see and be seen"). This highlighted the antiquated state of air traffic control, which became the focus of major aviation reforms.

Flight history

Trans World Airlines Flight 2, a Lockheed L-1049 Super Constellation named ''Star of the Seine'', withCaptain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

Jack Gandy (age 41), First Officer James Ritner (31), and Flight Engineer

A flight engineer (FE), also sometimes called an air engineer, is the member of an aircraft's flight crew who monitors and operates its complex aircraft systems. In the early era of aviation, the position was sometimes referred to as the "air me ...

Forrest Breyfogle (37), departed Los Angeles on Saturday, June 30, 1956, at 9:01 am PST with 64 passengers (including 11 TWA off-duty employees on free tickets) and six crew members (including two flight attendant

A flight attendant, also known as steward/stewardess or air host/air hostess, is a member of the aircrew aboard commercial flights, many business jets and some government aircraft. Collectively called cabin crew, flight attendants are prima ...

s and an off-duty flight engineer), and headed to Kansas City Downtown Airport, 31 minutes behind schedule. Flight 2, initially flying under instrument flight rules

In aviation, instrument flight rules (IFR) is one of two sets of regulations governing all aspects of civil aviation aircraft operations; the other is visual flight rules (VFR).

The U.S. Federal Aviation Administration's (FAA) ''Instrument Fly ...

(IFR), climbed to an authorized altitude

Altitude or height (also sometimes known as depth) is a distance measurement, usually in the vertical or "up" direction, between a reference datum and a point or object. The exact definition and reference datum varies according to the context ...

of and stayed in controlled airspace as far as Daggett, California. At Daggett, Captain Gandy turned right to a heading of 059 degrees magnetic, toward the radio range

The low-frequency radio range, also known as the four-course radio range, LF/MF four-course radio range, A-N radio range, Adcock radio range, or commonly "the range", was the main Radio navigation, navigation system used by aircraft for instrument ...

near Trinidad, Colorado

Trinidad is the home rule municipality that is the county seat and the most populous municipality of Las Animas County, Colorado, United States. The population was 8,329 as of the 2020 census. Trinidad lies north of Raton, New Mexico, and s ...

.CAB Docket 320, File 1, History of Flights, Section 1, issued 1957/04/17 The Constellation was now "off airways", otherwise known as flying in uncontrolled airspace.CAB Docket 320, File 1, History of Flights, Section 2, issued 1957/04/17

United Airlines Flight 718, a Douglas DC-7 named ''Mainliner Vancouver'', and flown by Captain Robert "Bob" Shirley (age 48), First Officer Robert Harms (36), and Flight Engineer Girardo "Gerard" Fiore (39), departed Los Angeles at 9:04 am PST with 53 passengers and five crew members aboard (including two flight attendants), bound for Chicago's Midway Airport

Chicago Midway International Airport , typically referred to as Midway Airport, Chicago Midway, or simply Midway, is a major commercial airport on the Southwest side of Chicago, Illinois, located approximately 12 miles (19 km) from the Lo ...

. Climbing to an authorized altitude of , Captain Shirley flew under IFR in controlled airspace

Controlled airspace is airspace of defined dimensions within which air traffic control (ATC) services are provided. The level of control varies with different classes of airspace. Controlled airspace usually imposes higher weather minimums tha ...

to a pointThe "Palm Springs" intersection was at about 33.92N 116.28W. northeast of Palm Springs, California

Palm Springs (Cahuilla: ''Séc-he'') is a desert resort city in Riverside County, California, United States, within the Colorado Desert's Coachella Valley. The city covers approximately , making it the largest city in Riverside County by land a ...

, where he turned left toward a radio beacon near Needles, California

Needles is a city in San Bernardino County, California, in the Mojave Desert region of Southern California. Situated on the western banks of the Colorado River, Needles is located near the Californian border with Arizona and Nevada. The city is a ...

, after which his flight plan was direct to Durango in southwestern Colorado.The report says their flight plan was Needles direct to Durango, but it's unclear what "Durango" means. There never was an LF/MF radio range there, and the VOR

VOR or vor may refer to:

Organizations

* Vale of Rheidol Railway in Wales

* Voice of Russia, a radio broadcaster

* Volvo Ocean Race, a yacht race

Science, technology and medicine

* VHF omnidirectional range, a radio navigation aid used in a ...

wasn't there in 1956. (There was an AM radio station.) The DC-7, though still under IFR jurisdiction, was now, like the Constellation, flying in uncontrolled airspace.

Shortly after takeoff TWA's Captain Gandy requested permission to climb to 21,000 feet to avoid thunderheads that were forming near his flight path. As was the practice at the time, his request had to be relayed by a TWA flight dispatcher

A flight dispatcher (also known as an airline dispatcher or flight operations officer) assists in planning flight paths, taking into account aircraft performance and loading, enroute winds, thunderstorm and turbulence forecasts, airspace restricti ...

to air traffic control (ATC), as neither crew was in direct contact with ATC after departure. ATC denied the request; the two airliners would soon be reentering controlled airspace (the Red 15 airway running southeast from Las Vegas) and ATC had no way to provide the horizontal separation required between two aircraft at the same altitude.

Captain Gandy requested "1,000 on top" clearance (flying 1000 feet 00 mabove the clouds), which was still under IFR, not VFR (visual flight rules

In aviation, visual flight rules (VFR) are a set of regulations under which a pilot operates an aircraft in weather conditions generally clear enough to allow the pilot to see where the aircraft is going. Specifically, the weather must be better ...

), which was approved by ATC. The provision to operate 1000'-on-top exists so that separation restrictions normally applied by ATC can be temporarily suspended. An aircraft cleared to operate 1000'-on-top is responsible for maintaining separation from other IFR aircraft – especially useful when two aircraft are transitioning to or from an approach when VFR conditions exist above cloud layers.

Flying under VFR placed the responsibility for maintaining safe separation from other aircraft upon Gandy and Ritner, a procedure referred to as "see and be seen," since changed to "see and avoid." Upon receiving "1,000 on top" clearance, Captain Gandy increased his altitude to .

Both crews had estimated that they would cross the Painted Desert line at about 10:31 am Pacific time. The Painted Desert line was about long, running between the VOR

VOR or vor may refer to:

Organizations

* Vale of Rheidol Railway in Wales

* Voice of Russia, a radio broadcaster

* Volvo Ocean Race, a yacht race

Science, technology and medicine

* VHF omnidirectional range, a radio navigation aid used in a ...

s at Bryce Canyon, Utah, and Winslow Winslow may refer to:

Places United Kingdom

* Winslow, Buckinghamshire, England, a market town and civil parish

* Winslow Rural District, Buckinghamshire, a rural district from 1894 to 1974

United States and Canada

* Rural Municipality of Winslow ...

, Arizona, at an angle of 335 degrees relative to true north – wholly outside of controlled air space. Owing to the different headings taken by the two planes, TWA's crossing of the Painted Desert line, assuming no further course changes, would be at a 13-degree angle relative to that of the United flight, with the Constellation to the left of the DC-7.

As the two aircraft approached the Grand Canyon, now at the same altitude and nearly the same speed, the pilots were likely maneuvering around towering cumulus clouds, though flying VFR required the TWA flight to stay in clear air. As they were maneuvering near the canyon, it is believed the planes passed the same cloud on opposite sides.

Collision

At about 10:30 a.m. the two aircraft collided over the canyon at an angle of about 25 degrees. Post-crash analysis determined that the United DC-7 was banking to the right and pitching down at the time of the collision, suggesting that one or possibly both of the United pilots spotted the TWA Constellation and attempted evasive action.

The DC-7's upraised left wing clipped the top of the Constellation's

At about 10:30 a.m. the two aircraft collided over the canyon at an angle of about 25 degrees. Post-crash analysis determined that the United DC-7 was banking to the right and pitching down at the time of the collision, suggesting that one or possibly both of the United pilots spotted the TWA Constellation and attempted evasive action.

The DC-7's upraised left wing clipped the top of the Constellation's vertical stabilizer

A vertical stabilizer or tail fin is the static part of the vertical tail of an aircraft. The term is commonly applied to the assembly of both this fixed surface and one or more movable rudders hinged to it. Their role is to provide control, sta ...

and struck the fuselage

The fuselage (; from the French ''fuselé'' "spindle-shaped") is an aircraft's main body section. It holds crew, passengers, or cargo. In single-engine aircraft, it will usually contain an engine as well, although in some amphibious aircraft t ...

immediately ahead of the stabilizer's base, causing the tail assembly

The empennage ( or ), also known as the tail or tail assembly, is a structure at the rear of an aircraft that provides stability during flight, in a way similar to the feathers on an arrow.Crane, Dale: ''Dictionary of Aeronautical Terms, third e ...

to break away from the rest of the airframe

The mechanical structure of an aircraft is known as the airframe. This structure is typically considered to include the fuselage, undercarriage, empennage and wings, and excludes the propulsion system.

Airframe design is a field of aerospa ...

. The propeller

A propeller (colloquially often called a screw if on a ship or an airscrew if on an aircraft) is a device with a rotating hub and radiating blades that are set at a pitch to form a helical spiral which, when rotated, exerts linear thrust upon ...

on the DC-7's left outboard, or number one engine

An engine or motor is a machine designed to convert one or more forms of energy into mechanical energy.

Available energy sources include potential energy (e.g. energy of the Earth's gravitational field as exploited in hydroelectric power gen ...

, concurrently chopped a series of gashes into the bottom of the Constellation's fuselage. Explosive decompression

Uncontrolled decompression is an unplanned drop in the pressure of a sealed system, such as an aircraft cabin or hyperbaric chamber, and typically results from human error, material fatigue, engineering failure, or impact, causing a pressure vesse ...

would have instantaneously occurred from the damage, a theory substantiated by light debris, such as cabin furnishings and personal effects, being scattered over a large area.

The separation of the tail assembly from the Constellation resulted in immediate loss of control, causing the aircraft to enter a near-vertical, terminal velocity dive. Plunging into the Grand Canyon at an estimated speed of more than , the Constellation slammed into the north slope of a ravine on the northeast slope of Temple Butte and disintegrated on impact, instantly killing all aboard. An intense fire, fueled by

The separation of the tail assembly from the Constellation resulted in immediate loss of control, causing the aircraft to enter a near-vertical, terminal velocity dive. Plunging into the Grand Canyon at an estimated speed of more than , the Constellation slammed into the north slope of a ravine on the northeast slope of Temple Butte and disintegrated on impact, instantly killing all aboard. An intense fire, fueled by aviation gasoline

Avgas (aviation gasoline, also known as aviation spirit in the UK) is an aviation fuel used in aircraft with spark-ignited internal combustion engines. ''Avgas'' is distinguished from conventional gasoline (petrol) used in motor vehicles, whi ...

, ensued. The severed tail assembly, badly battered but still somewhat recognizable, came to rest nearby.

The DC-7's left wing to the left of the number one engine was mangled by the impact and was no longer capable of producing substantial lift. The engine had been severely damaged as well, and the combined loss of lift and propulsion left the crippled airliner in a rapidly descending left spiral from which recovery was impossible. The ''Mainliner'' collided with the south side cliff

In geography and geology, a cliff is an area of rock which has a general angle defined by the vertical, or nearly vertical. Cliffs are formed by the processes of weathering and erosion, with the effect of gravity. Cliffs are common on co ...

of Chuar Butte

Chuar Butte is a prominent 6,500-foot-elevation (1,981 meter) summit located in the Grand Canyon, in Coconino County of northern Arizona, US. It is situated 1.5 miles northwest of Cape Solitude on the canyon's East Rim, three miles southeas ...

and disintegrated, instantly killing all aboard.

Aftermath

Search and recovery

The airspace over the canyon was not under any type ofradar

Radar is a detection system that uses radio waves to determine the distance (''ranging''), angle, and radial velocity of objects relative to the site. It can be used to detect aircraft, ships, spacecraft, guided missiles, motor vehicles, w ...

observation and there were no homing beacons or "black boxes" ( cockpit voice and flight data recorders) aboard either aircraft. The last position reports received from the flights did not reflect their locations at the time of the collision. Also, there were no credible witnesses to the collision itself or the subsequent crashes.

The only immediate indication of trouble was when United company radio operators in Salt Lake City

Salt Lake City (often shortened to Salt Lake and abbreviated as SLC) is the Capital (political), capital and List of cities and towns in Utah, most populous city of Utah, United States. It is the county seat, seat of Salt Lake County, Utah, Sal ...

and San Francisco

San Francisco (; Spanish language, Spanish for "Francis of Assisi, Saint Francis"), officially the City and County of San Francisco, is the commercial, financial, and cultural center of Northern California. The city proper is the List of Ca ...

heard a garbled transmission from Flight 718, the last from either aircraft. Civil Aeronautics Board (CAB) accident investigation

Accident analysis is carried out in order to determine the cause or causes of an accident (that can result in single or multiple outcomes) so as to prevent further accidents of a similar kind. It is part of ''accident investigation or incident inv ...

engineers later deciphered the transmission – which had been preserved on magnetic tape

Magnetic tape is a medium for magnetic storage made of a thin, magnetizable coating on a long, narrow strip of plastic film. It was developed in Germany in 1928, based on the earlier magnetic wire recording from Denmark. Devices that use magne ...

– as the voice of co-pilot Robert Harms declaring, "Salt Lake, h 718 ... we are going in!" The shrill voice of Captain Shirley was heard in the background as, presumably futilely struggling with the controls, he implored the airplane to "ull

Ull or ULL may refer to:

University:

* University of La Laguna, a university in Canary Islands, Spain

* University of Louisiana at Lafayette, a research university in the USA

Other:

* Ullr or Ull, a Germanic god

* Ull (Greyhawk), a political sta ...

up! ull

Ull or ULL may refer to:

University:

* University of La Laguna, a university in Canary Islands, Spain

* University of Louisiana at Lafayette, a research university in the USA

Other:

* Ullr or Ull, a Germanic god

* Ull (Greyhawk), a political sta ...

up!" (bracketed words were inferred by investigators from the context and circumstances in which they were uttered).

After neither flight reported their current position for some time, the two aircraft were declared to be missing, and search and rescue procedures started. The wreckage was first seen late in the day near the confluence of the Colorado

Colorado (, other variants) is a state in the Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It encompasses most of the Southern Rocky Mountains, as well as the northeastern portion of the Colorado Plateau and the western edge of t ...

and Little Colorado River

The Little Colorado River () is a tributary of the Colorado River in the U.S. state of Arizona, providing the principal drainage from the Painted Desert region. Together with its major tributary, the Puerco River, it drains an area of about in ...

s by Henry and Palen Hudgin, two brothers who operated Grand Canyon Airlines

Grand Canyon Airlines is a 14 CFR Part 135 air carrier headquartered on the grounds of Boulder City Municipal Airport in Boulder City, Nevada, United States. It also has bases at Grand Canyon National Park Airport and Page Municipal Airport, bot ...

, a small air taxi service.''Blind Trust'', by John J. Nance, William Morrow & Co., Inc. (US), 1986, , pp. 96–97 During a trip earlier in the day, Palen had noted dense black smoke rising near Temple Butte, the crash site of the Constellation, but had dismissed it as brush set ablaze by lightning

Lightning is a naturally occurring electrostatic discharge during which two electric charge, electrically charged regions, both in the atmosphere or with one on the land, ground, temporarily neutralize themselves, causing the instantaneous ...

.

However, upon hearing of the missing airliners, Palen decided that what he had seen might have been smoke from a post-crash fire. He and his brother flew a light aircraft (a

However, upon hearing of the missing airliners, Palen decided that what he had seen might have been smoke from a post-crash fire. He and his brother flew a light aircraft (a Piper Tri-Pacer

The PA-20 Pacer and PA-22 Tri-Pacer, Caribbean, and Colt are an American family of light strut-braced high-wing monoplane aircraft built by Piper Aircraft from 1949 to 1964.

The Pacer is essentially a four-place version of the two-place ...

) deep into the canyon and searched near the location of the smoke. The Constellation's empennage

The empennage ( or ), also known as the tail or tail assembly, is a structure at the rear of an aircraft that provides stability during flight, in a way similar to the feathers on an arrow.Crane, Dale: ''Dictionary of Aeronautical Terms, third ed ...

was found, and the brothers reported their findings to authorities. The following day, the two men pinpointed the wreckage of the DC-7. Numerous helicopter

A helicopter is a type of rotorcraft in which lift and thrust are supplied by horizontally spinning rotors. This allows the helicopter to take off and land vertically, to hover, and to fly forward, backward and laterally. These attributes ...

missions were subsequently flown down to the crash sites to find and attempt to identify victims, as well as recover wreckage for accident analysis, a difficult and dangerous process due to the rugged terrain and unpredictable air current

In meteorology, air currents are concentrated areas of winds. They are mainly due to differences in atmospheric pressure or temperature. They are divided into horizontal and vertical currents; both are present at mesoscale while horizontal ones d ...

s.

The airlines hired the Swiss Air-Rescue and some Swiss mountain climbers to go to the scene where the aircraft fuselages had crashed. They were to gather the remains of the passengers and their personal effects. This was given considerable publicity in U.S. news releases at the time because of the ruggedness of the terrain where the fuselages came to rest.

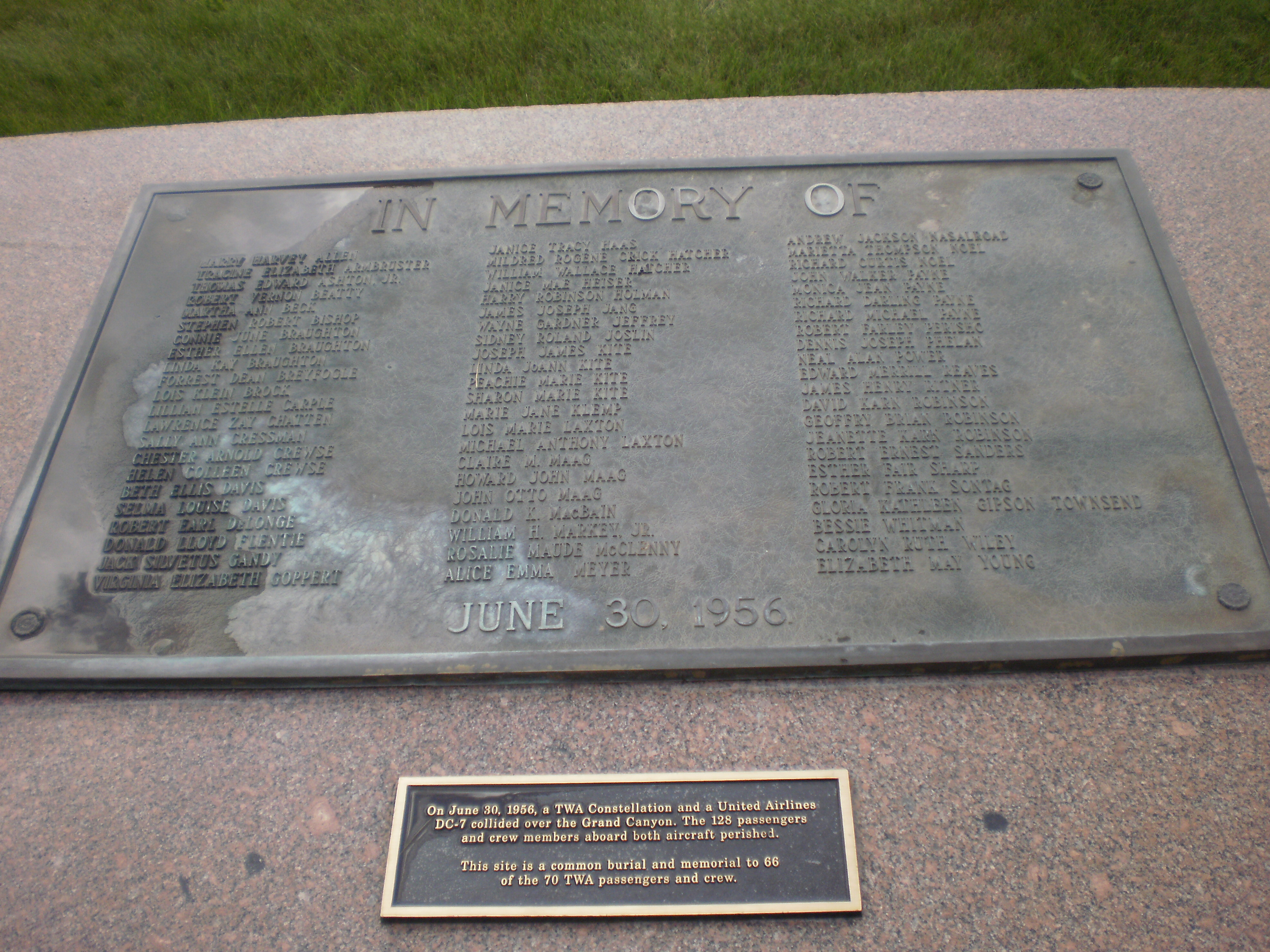

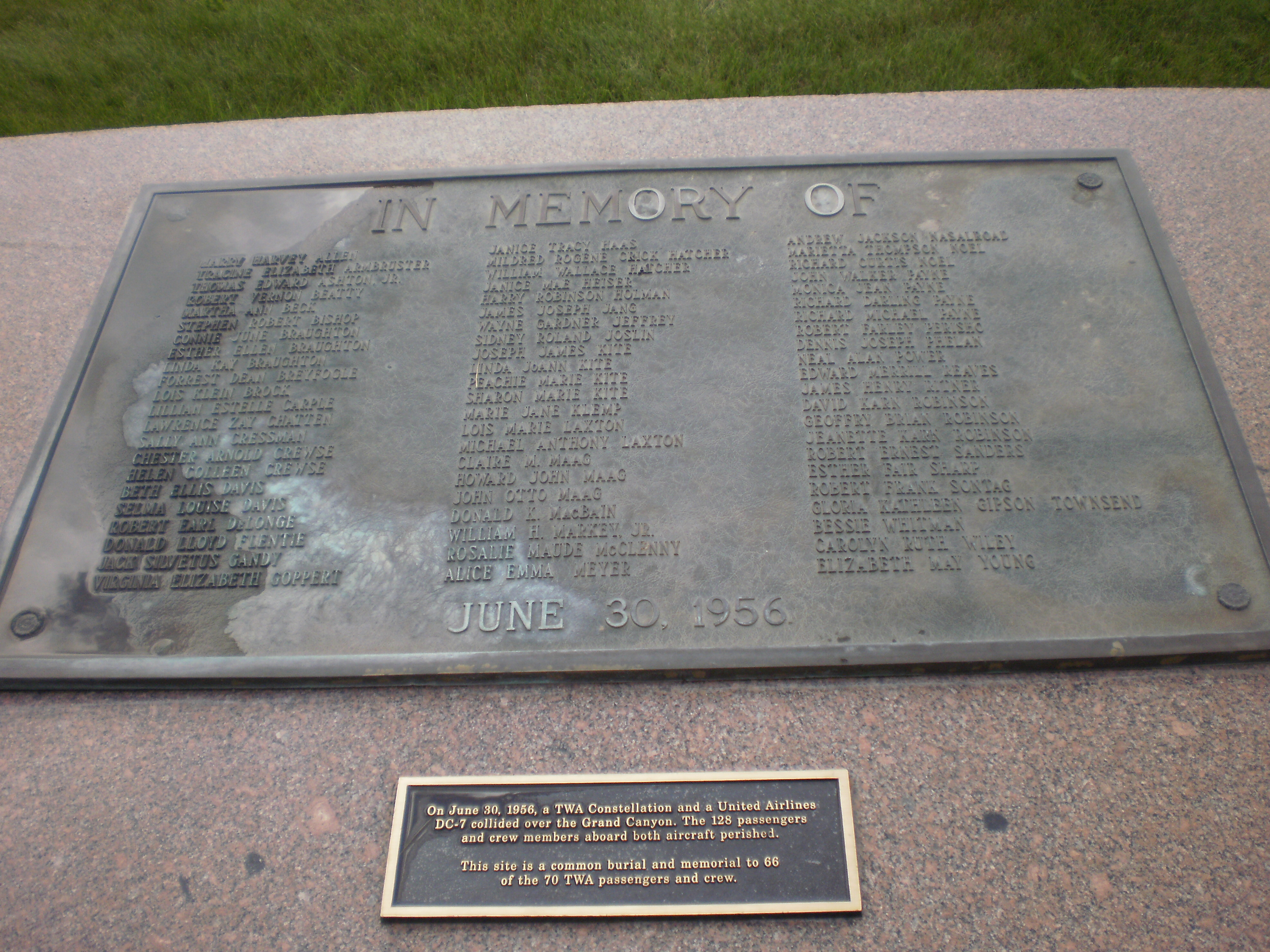

Owing to the great violence of the impacts, no bodies were recovered intact and positive identification of most of the remains was not possible. On July 9, 1956, a mass funeral for the victims of TWA Flight 2 was held at the canyon's south rim. Twenty-nine unidentified victims of the United flight were interred in four coffins at the

The airlines hired the Swiss Air-Rescue and some Swiss mountain climbers to go to the scene where the aircraft fuselages had crashed. They were to gather the remains of the passengers and their personal effects. This was given considerable publicity in U.S. news releases at the time because of the ruggedness of the terrain where the fuselages came to rest.

Owing to the great violence of the impacts, no bodies were recovered intact and positive identification of most of the remains was not possible. On July 9, 1956, a mass funeral for the victims of TWA Flight 2 was held at the canyon's south rim. Twenty-nine unidentified victims of the United flight were interred in four coffins at the Grand Canyon Pioneer Cemetery

Grand Canyon Pioneer Cemetery, also known as Pioneer Cemetery, is a historic cemetery located near the Grand Canyon's South Rim.

It is also known as South Rim Cemetery and the American Legion Cemetery due to its association with the veterans' orga ...

. Sixty-six of the seventy TWA passengers and crew are buried in a mass grave at Citizens Cemetery in Flagstaff, Arizona

Flagstaff ( ) is a city in, and the county seat of, Coconino County, Arizona, Coconino County in northern Arizona, in the southwestern United States. In 2019, the city's estimated population was 75,038. Flagstaff's combined metropolitan area has ...

. A number of years elapsed following this accident before most of the wreckage was removed from the canyon. Some pieces of the aircraft remain at the crash sites.

Investigation

The investigation of this accident was particularly challenging due to the remoteness andtopography

Topography is the study of the forms and features of land surfaces. The topography of an area may refer to the land forms and features themselves, or a description or depiction in maps.

Topography is a field of geoscience and planetary sci ...

of the crash sites, as well as the extent of the destruction of the two airliners and the lack of real-time flight data as might be derived from a modern flight data recorder. Despite the considerable difficulties, CAB experts were able to determine with a remarkable degree of certainty what had transpired and, in their report, issued the following statement as probable cause for the accident:CAB Docket 320, File 1, Probable Cause, issued 1957/04/17

In the report, weather and the airworthiness of the two planes were thought to have played no role in the accident. Lacking credible eyewitnesses and with some uncertainty regarding high altitude visibility at the time of the collision, it was not possible to determine conclusively how much opportunity was available for the TWA and United pilots to see and avoid each other.

Neither flight crew was specifically implicated in the CAB's finding of probable cause, although the decision by TWA's Captain Gandy to cancel his IFR flight plan and fly "1,000 on top" was the likely catalyst for the accident. Also worth noting was that the investigation itself was thorough in all respects, but the final report focused on technical issues and largely ignored contributory human factors, such as why the airlines permitted their pilots to execute maneuvers solely intended to improve the passengers' view of the canyon. It would not be until the late 1970s that human factors would be as thoroughly investigated as technical matters following aerial mishaps.

During the investigation, Milford "Mel" Hunter, a scientific and technical illustrator with ''Life'' magazine, was given early and unrestricted access to the CAB's data and preliminary findings, enabling him to produce an illustration of what likely occurred at the moment of the collision. Hunter's finely detailed gouache

Gouache (; ), body color, or opaque watercolor is a water-medium paint consisting of natural pigment, water, a binding agent (usually gum arabic or dextrin), and sometimes additional inert material. Gouache is designed to be opaque. Gouache h ...

painting first appeared in ''Life'' April 29, 1957, issue and was subsequently included in David Gero's 1996 edition of ''Aviation Disasters II''.

In a letter to Gero in 1995, Hunter wrote:As related by Susan Smith-Hunter, Mel Hunter's widow.

Hunter's recollection of his illustration was not completely accurate. The painting showed the DC-7 below the Constellation, with the former's number one engine beneath the latter's fuselage, which agreed with the CAB technical findings.

Catalyst for change

At 128 fatalities, the Grand Canyon collision became the deadliest U.S. commercial airline disaster and deadliest air crash on U.S. soil of any kind, surpassing United Airlines Flight 409 the year before. It was surpassed in both respects on December 16, 1960, by the1960 New York mid-air collision

On December 16, 1960, a United Airlines Douglas DC-8 bound for Idlewild Airport (now John F. Kennedy International Airport) in New York City collided in midair with a TWA Lockheed L-1049 Super Constellation descending toward LaGuardia Airport. T ...

(also involving United and TWA aircraft).

The accident was covered by the press worldwide, and as the story unfolded, the public learned of the primitive nature of air traffic control (ATC) and how little was being done to modernize it. The air traffic controller who had cleared TWA to "1,000 on top" was severely criticized as he had not advised Captains Gandy and Shirley about the potential for a traffic conflict following the clearance, even though he must have known of the possibility. The controller was publicly blamed for the accident by both airlines and was vilified in the press, but he was cleared of any wrongdoing. As Charles Carmody (the then-assistant ATC director) testified during the investigation, neither flight was legally under the control of ATC when they collided, as both were "off airways." The controller was not required to issue a traffic conflict advisory to either pilot. According to the CAB accident investigation final report, page 8, the en-route controller relayed a traffic advisory regarding United 718 to TWA's ground radio operator: "ATC clears TWA 2, maintain at least 1,000 on top. Advise TWA 2 his traffic is United 718, direct Durango, estimating Needles at 0957." The TWA operator testified that Captain Gandy acknowledged the information on the United flight as "traffic received."

The accident was particularly alarming in that public confidence in air travel had increased during the 1950s with the introduction of new airliners like the Super Constellation, Douglas DC-7, and Boeing Stratocruiser

The Boeing 377 Stratocruiser was a large long-range airliner developed from the C-97 Stratofreighter military transport, itself a derivative of the B-29 Superfortress. The Stratocruiser's first flight was on July 8, 1947. Its design was advanced ...

. Travel by air had become routine for large corporations and vacationers often considered flying instead of traveling by train

In rail transport, a train (from Old French , from Latin , "to pull, to draw") is a series of connected vehicles that run along a railway track and Passenger train, transport people or Rail freight transport, freight. Trains are typically pul ...

. At the time, a congressional committee was reviewing domestic air travel, as there was growing concern over the number of accidents. However, little progress was being made and the state of ATC at the time of the Grand Canyon accident reflected the methods of the 1930s.

As near-misses and mid-air collisions continued, the public demanded action. Often-contentious congressional hearings followed, and in 1957, increased funding was allocated to modernize ATC, hire and train more air traffic controllers, and procure much-needed radar – initially military surplus equipment.

However, control of American airspace continued to be split between the military

A military, also known collectively as armed forces, is a heavily armed, highly organized force primarily intended for warfare. It is typically authorized and maintained by a sovereign state, with its members identifiable by their distinct ...

and the Civil Aeronautics Administration (CAA, the federal agency in charge of air traffic control at the time). The CAA had no authority over military flights, which could enter controlled airspace with no warning to other traffic. The result was a series of near-misses and collisions involving civil and military aircraft

A military aircraft is any fixed-wing or rotary-wing aircraft that is operated by a legal or insurrectionary armed service of any type. Military aircraft can be either combat or non-combat:

* Combat aircraft are designed to destroy enemy equipm ...

, the latter often flying at much higher speeds than the former. For example, in 1958, the collision of United Airlines Flight 736 flying "on-airways" and an F-100 Super Sabre

The North American F-100 Super Sabre is an American supersonic jet fighter aircraft that served with the United States Air Force (USAF) from 1954 to 1971 and with the Air National Guard (ANG) until 1979. The first of the Century Series of ...

fighter jet near Las Vegas, Nevada

Las Vegas (; Spanish for "The Meadows"), often known simply as Vegas, is the 25th-most populous city in the United States, the most populous city in the state of Nevada, and the county seat of Clark County. The city anchors the Las Vegas ...

, resulted in 49 fatalities.

Again, action was demanded. After more hearings, the Federal Aviation Act of 1958

The Federal Aviation Act of 1958 was an act of the United States Congress, signed by President Dwight D. Eisenhower, that created the Federal Aviation Agency (later the Federal Aviation Administration or the FAA) and abolished its predecessor, th ...

was passed, dissolving the CAA and creating the Federal Aviation Agency (FAA, later renamed the Federal Aviation Administration

The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) is the largest transportation agency of the U.S. government and regulates all aspects of civil aviation in the country as well as over surrounding international waters. Its powers include air traffic m ...

in 1966). The FAA was given total authority over American airspace, including military activity, and as procedures and ATC facilities were modernized, mid-air collisions gradually became less frequent.

National Historic Landmark

On April 22, 2014, the site of the crash was declared aNational Historic Landmark

A National Historic Landmark (NHL) is a building, district, object, site, or structure that is officially recognized by the United States government for its outstanding historical significance. Only some 2,500 (~3%) of over 90,000 places listed ...

, making it the first landmark for an event that happened in the air. The location, in a remote portion of the canyon only accessible to hikers, has been closed to the public since the 1950s.

Dramatizations

In 2006, the story of this disaster was covered in the third season of the History Channel program ''UFO Files

''UFO Files'' is an American television series that was produced from 2004 to 2007 for History (American TV network), The History Channel. The program covers the phenomena of Unidentified flying object, unidentified flying and Unidentified submer ...

''. The episode, entitled "Black Box UFO Secrets", contained the Universal Newsreel footage of the accident narrated by Ed Herlihy

Edward Joseph Herlihy (August 14, 1909 – January 30, 1999)Cox, Jim (2008). ''This Day in Network Radio: A Daily Calendar of Births, Debuts, Cancellations and Other Events in Broadcasting History''. McFarland & Company, Inc. . was an Ameri ...

.

In 2010, the story of the disaster, along with other mid-air collisions, was featured on the eighth season of the National Geographic Channel

National Geographic (formerly National Geographic Channel; abbreviated and trademarked as Nat Geo or Nat Geo TV) is an American pay television television network, network and flagship (broadcasting), flagship channel owned by the National Geograp ...

show ''Mayday

Mayday is an emergency procedure word used internationally as a distress signal in voice-procedure radio communications.

It is used to signal a life-threatening emergency primarily by aviators and mariners, but in some countries local organiza ...

'' (also known as ''Air Emergency'' and ''Air Crash Investigation''). The special episode is entitled "System Breakdown". In 2013, an episode from the twelfth season, entitled "Grand Canyon Disaster", also featured this accident.

It is featured in season 1, episode 5, of the TV show '' Why Planes Crash'', in an episode called "Collision Course".

In 2015, the first season of '' Mysteries at the National Parks'' on the Travel Channel, in the series' seventh episode entitled, "Portal To The Underworld" the crash was also featured and was mentioned as being a "supernatural event."

Literary reference

In his novel ''Skeleton Man

''Skeleton Man'' is a 2004 made-for-tv slasher film directed by Johnny Martin and starring Michael Rooker and Casper Van Dien. It was aired from Sci Fi Channel on March 1, 2004. In the film, the titular Skeleton Man stalks a squad of soldiers.

P ...

'' (2004), Tony Hillerman uses this event as the backdrop to his story.

In the Arthur Hailey

Arthur Frederick Hailey, AE (5 April 1920 – 24 November 2004) was a British-Canadian novelist whose plot-driven storylines were set against the backdrops of various industries. His books, which include such best sellers as ''Hotel'' (1965), ...

novel ''Airport

An airport is an aerodrome with extended facilities, mostly for commercial air transport. Airports usually consists of a landing area, which comprises an aerially accessible open space including at least one operationally active surface ...

'', Mel thinks that another big disaster like this incident would arouse public awareness about the airport's deficiencies.

In Colin Fletcher

Colin Fletcher (14 March 1922 – 12 June 2007) was a pioneering backpacker and writer.

In 1963, Fletcher walked the length of that portion of Grand Canyon contained within the 1963 boundaries of Grand Canyon National Park. Although hi ...

's 1968 account of walking Grand Canyon National Park end-to-end in 1963, "The Man Who Walked Through Time

''The Man Who Walked Through Time'' (1968) is Colin Fletcher's chronicle of the first person to walk a continuous route through Grand Canyon National Park. The book is credited with "introducing an increasingly nature-hungry public to the spiritua ...

", he gives an account of somberly hiking by the wreckage of the aircraft.

See also

*List of National Historic Landmarks in Arizona

This is a List of National Historic Landmarks in Arizona. There are 47 National Historic Landmarks (NHLs) in Arizona, counting Hoover Dam that spans from Nevada and is listed in Nevada by the National Park Service (NPS), and Yuma Crossing and Assoc ...

* National Register of Historic Places listings in Coconino County, Arizona

* Aeromexico Flight 498

* 1976 Zagreb mid-air collision

The 1976 Zagreb mid-air collision took place on 10 September 1976, when British Airways Flight 476, a Hawker Siddeley Trident en route from London to Istanbul, collided mid-air with Inex-Adria Aviopromet Flight 550, a Douglas DC-9 en route from ...

* Gol Linhas Aéreas Flight 1907

* PSA Flight 182

* Überlingen mid-air collision

Überlingen is a German city on the northern shore of Lake Constance (Bodensee) in Baden-Württemberg near the border with Switzerland. After the city of Friedrichshafen, it is the second largest city in the Bodenseekreis (district), and a centr ...

* 1960 New York mid-air collision

On December 16, 1960, a United Airlines Douglas DC-8 bound for Idlewild Airport (now John F. Kennedy International Airport) in New York City collided in midair with a TWA Lockheed L-1049 Super Constellation descending toward LaGuardia Airport. T ...

* Charkhi Dadri Mid-Air Collision

On 12 November 1996, Saudia Flight 763, a Boeing 747 en route from Delhi, India, to Dhahran, Saudi Arabia, and Kazakhstan Airlines Flight 1907, an Ilyushin Il-76 en route from Chimkent, Kazakhstan, to Delhi, collided over the village of Charkhi ...

* First midair collision of airliners

The 1922 Picardie mid-air collision took place on 7 April 1922 over Picardie, France, involving British and French passenger-carrying biplanes. The midair collision occurred in foggy conditions. A British aircraft flying from Croydon to Paris wit ...

* Free flight (air traffic control)

Free flight is a developing air traffic control method that uses no centralized control (e.g. air traffic controllers). Instead, parts of airspace are reserved dynamically and automatically in a distributed way using computer communication to ens ...

* 1986 Grand Canyon mid-air collision

The Grand Canyon mid-air collision occurred when Grand Canyon Airlines Flight 6, a de Havilland Canada DHC-6 Twin Otter, collided with a Bell 206 helicopter, Helitech Flight 2, over Grand Canyon National Park on June 18, 1986. All 25 passengers a ...

, another airliner involved in a mid-air collision over the Grand Canyon

* Hughes Airwest Flight 706

Hughes Airwest Flight 706 was a regularly scheduled flight operated by American domestic airline Hughes Airwest from Los Angeles, California to Seattle, Washington, with several intermediate stops. On Sunday, June 6, 1971, the McDonnell Douglas D ...

*2001 Japan Airlines mid-air incident

On January 31, 2001, Japan Airlines Flight 907, a Boeing 747-400 en route from Haneda Airport, Japan, to Naha Airport, Okinawa, narrowly avoided a mid-air collision with Japan Airlines Flight 958, a McDonnell Douglas DC-10-40 en route from Gimha ...

Notes

References

Sources

* Civil Aeronautics Board Official Report, Docket 320, File 1, issued on April 17, 1957 * ''Air Disaster, Vol. 4: The Propeller Era'', by Macarthur Job, Aerospace Publications Pty. Ltd. (Australia), 2001. * ''Blind Trust'', byJohn J. Nance

John J. Nance (born July 5, 1946) is an American pilot, attorney, aviation and healthcare safety analyst, and author.

Biography

Nance was born and raised in Dallas, Texas, and graduated from the St. Mark's School of Texas. He earned Bachelor of ...

, William Morrow & Co., Inc. (US), 1986,

External links

*Alternate URL

wit

* *

by Jon Proctor

by Gregory Rawlins

Arizona Aircraft Archaeology

What Caused The "Worst Accident In The History" Of Commercial Aviation?

Mayday: Air Disaster - YouTube Channel {{DEFAULTSORT:Grand Canyon mid-air collision, 1956 Airliner accidents and incidents in Arizona Aviation accidents and incidents in the United States in 1956 History of air traffic control History of Coconino County, Arizona Trans World Airlines accidents and incidents United Airlines accidents and incidents 1956 in Arizona Disasters in Arizona Burials in Arizona Grand Canyon Accidents and incidents involving the Douglas DC-7 Accidents and incidents involving the Lockheed Constellation Airliner accidents and incidents caused by pilot error Mid-air collisions Mid-air collisions involving airliners National Historic Landmarks in Arizona National Register of Historic Places in Coconino County, Arizona June 1956 events in the United States 1956 in the United States