Union Army Balloon Corps on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Union Army Balloon Corps was a branch of the

Professor

Professor

was an early pioneer of American ballooning born in 1808. Although he made great contributions to the then newborn science of aeronautics, he was more a showman than a scientist. His attempts at free flight in preparation for a transatlantic crossing were less than successful, and he did not receive the same type of financial support from the patrons of the sciences, nor did he carry the overall scientific credibility of Lowe. Wise was, however, taken seriously enough by the

The generators were built at the

The generators were built at the  Lowe built seven balloons, six of which were put into service. Each balloon was accompanied by two gas generating sets. The smaller balloons were used in windier weather, or for quick, one-man, low altitude ascents. They inflated quickly since they required less gas. They were:

:*''Eagle''

:*''Constitution''

:*''Washington''

The larger balloons were used for carrying more weight, such as a telegraph key set and an additional man as an operator. They could also ascend higher. They were:

:*''Union''

:*'' Intrepid'' (Lowe's favorite balloon)

:*''Excelsior''

:*''United States''

The latter two balloons were held in storage in a Washington warehouse. Eventually the ''Excelsior'' was sent to Camp Lowe, a high altitude observation point, as a back-up balloon to the ''Intrepid'' during harsh winter weather, but the ''United States'' was never put into service. LaMountain made reference to these two balloons in his diatribes against Lowe as "being hoarded" by Lowe so he could buy them unused at the end of the war.

Lowe built seven balloons, six of which were put into service. Each balloon was accompanied by two gas generating sets. The smaller balloons were used in windier weather, or for quick, one-man, low altitude ascents. They inflated quickly since they required less gas. They were:

:*''Eagle''

:*''Constitution''

:*''Washington''

The larger balloons were used for carrying more weight, such as a telegraph key set and an additional man as an operator. They could also ascend higher. They were:

:*''Union''

:*'' Intrepid'' (Lowe's favorite balloon)

:*''Excelsior''

:*''United States''

The latter two balloons were held in storage in a Washington warehouse. Eventually the ''Excelsior'' was sent to Camp Lowe, a high altitude observation point, as a back-up balloon to the ''Intrepid'' during harsh winter weather, but the ''United States'' was never put into service. LaMountain made reference to these two balloons in his diatribes against Lowe as "being hoarded" by Lowe so he could buy them unused at the end of the war.

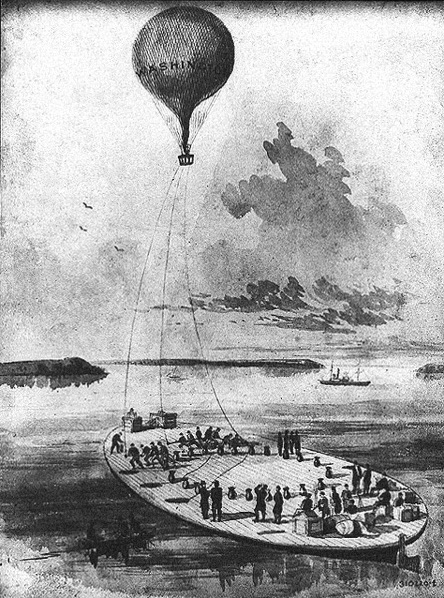

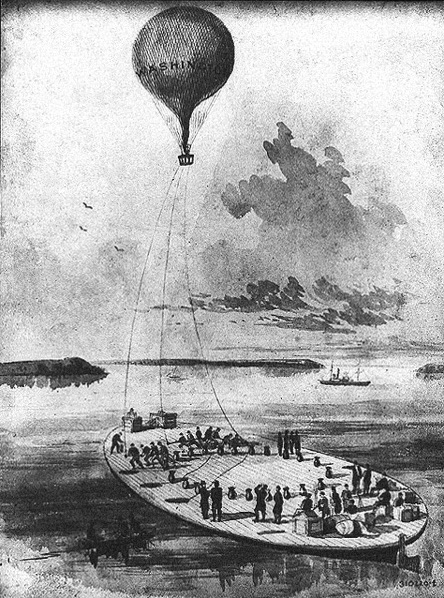

The ''General Washington Parke Custis'', a converted coal barge, had its deck cleared of all items that could entangle the ropes and nets of the balloons, and it was used as a river transport for the Corps. Lowe had two gas generators and a balloon loaded aboard and later reported:

The ''General Washington Parke Custis'', a converted coal barge, had its deck cleared of all items that could entangle the ropes and nets of the balloons, and it was used as a river transport for the Corps. Lowe had two gas generators and a balloon loaded aboard and later reported:

The battlefront turned toward

The battlefront turned toward  A small contingent from Gen.

A small contingent from Gen.

Manned air-war mechanisms became important again to the Army when the

Manned air-war mechanisms became important again to the Army when the Balloon Bombs

I

(#11 & #12) O.R. - Series III - Volume III #124Correspondence, Orders, Reports, and Returns of the Union Authorities From 1 January to 31 December 1863''. * Manning, Mike, ''Intrepid, An Account of Prof. T.S.C. Lowe, Civil War Aeronaut and Hero'', self-published 2005. * Poleskie, Stephen, ''The Balloonist: The Story of T. S. C. Lowe—Inventor, Scientist, Magician, and Father of the U.S. Air Force'', Frederic C. Beil, 2007. * Seims, Charles, ''Mount Lowe, The Railway in the Clouds'', Golden West Books,

Thaddeus Lowe website

{{American Civil War Balloon Corps Aviation units and formations of the United States Army Reconnaissance units and formations of the United States Army Balloon weaponry Balloons (aeronautics) Military units and formations established in 1861 1861 establishments in the United States Military units and formations disestablished in 1863

Union Army

During the American Civil War, the Union Army, also known as the Federal Army and the Northern Army, referring to the United States Army, was the land force that fought to preserve the Union (American Civil War), Union of the collective U.S. st ...

during the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

, established by presidential appointee Thaddeus S. C. Lowe

Thaddeus Sobieski Constantine Lowe (August 20, 1832 – January 16, 1913), also known as Professor T. S. C. Lowe, was an American Civil War aeronaut, scientist and inventor, mostly self-educated in the fields of chemistry, meteorology, and ...

. It was organized as a civilian operation, which employed a group of prominent American aeronaut

Aeronautics is the science or art involved with the study, design, and manufacturing of air flight–capable machines, and the techniques of operating aircraft and rockets within the atmosphere. The British Royal Aeronautical Society identifie ...

s and seven specially built, gas-filled balloons

A balloon is a flexible bag that can be inflated with a gas, such as helium, hydrogen, nitrous oxide, oxygen

Oxygen is the chemical element with the symbol O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the chalcogen group in the per ...

to perform aerial reconnaissance

Aerial reconnaissance is reconnaissance for a military or strategic purpose that is conducted using reconnaissance aircraft. The role of reconnaissance can fulfil a variety of requirements including artillery spotting, the collection of ima ...

on the Confederate States Army

The Confederate States Army, also called the Confederate Army or the Southern Army, was the military land force of the Confederate States of America (commonly referred to as the Confederacy) during the American Civil War (1861–1865), fighting ...

.

Lowe was one of a few veteran balloonists who was working on an attempt to make a transatlantic crossing

Transatlantic crossings are passages of passengers and cargo across the Atlantic Ocean between Europe or Africa and the Americas. The majority of passenger traffic is across the North Atlantic between Western Europe and North America. Centuries ...

by balloon. His efforts were interrupted by the onset of the Civil War, which broke out one week before one of his most important test flights. Subsequently, he offered his aviation expertise to the development of an air-war mechanism through the use of aerostat

An aerostat (, via French) is a lighter-than-air aircraft that gains its lift through the use of a buoyant gas. Aerostats include unpowered balloons and powered airships. A balloon may be free-flying or tethered. The average density of the cra ...

s for reconnaissance

In military operations, reconnaissance or scouting is the exploration of an area by military forces to obtain information about enemy forces, terrain, and other activities.

Examples of reconnaissance include patrolling by troops (skirmisher ...

purposes. Lowe met with U.S. President

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United States ...

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

on 11 June 1861, and proposed a demonstration with his own balloon, the ''Enterprise

Enterprise (or the archaic spelling Enterprize) may refer to:

Business and economics

Brands and enterprises

* Enterprise GP Holdings, an energy holding company

* Enterprise plc, a UK civil engineering and maintenance company

* Enterpris ...

'', from the lawn of the armory directly across the street from the White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. It is located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW in Washington, D.C., and has been the residence of every U.S. president since John Adams in 1800. ...

. From a height of he telegraphed a message to the President describing his view of the Washington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

, countryside. Eventually he was chosen over other candidates to be chief aeronaut of the newly formed Union Army Balloon Corps.

The Balloon Corps with a hand-selected team of expert aeronauts served at Yorktown, Seven Pines, Antietam

The Battle of Antietam (), or Battle of Sharpsburg particularly in the Southern United States, was a battle of the American Civil War fought on September 17, 1862, between Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia and Union G ...

, Fredericksburg, and other major battles of the Potomac River

The Potomac River () drains the Mid-Atlantic United States, flowing from the Potomac Highlands into Chesapeake Bay. It is long,U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map. Retrieved Augus ...

and the Virginia Peninsula

The Virginia Peninsula is a peninsula in southeast Virginia, USA, bounded by the York River, James River, Hampton Roads and Chesapeake Bay. It is sometimes known as the ''Lower Peninsula'' to distinguish it from two other peninsulas to the ...

. The Balloon Corps served the Union Army from October 1861 until the summer of 1863, when it was disbanded following the resignation of Lowe.

Selecting a Chief Aeronaut

The use of balloons as an air-war mechanism was first recorded in France by theFrench Aerostatic Corps

The French Aerostatic Corps or Company of Aeronauts (french: compagnie d'aérostiers) was the world's first balloon unit, Jeremy Beadle and Ian Harrison, ''First, Lasts & Onlys: Military'', p. 42 founded in 1794 to use balloons, primarily for rec ...

at the Battle of Fleurus in 1794. U. S. President Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

became interested in an air-war mechanism for reconnaissance purposes. This created a notion at the War Department and at the Treasury that some sort of balloon aviation unit need be established and headed by a "Chief Aeronaut". Several top American balloonists traveled to Washington

Washington commonly refers to:

* Washington (state), United States

* Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States

** A metonym for the federal government of the United States

** Washington metropolitan area, the metropolitan area centered o ...

in hopes of obtaining just such a position. However, there were no proposed details to the establishment of such a unit, or whether it would even be a military or civilian operation. Nor was there any set method to the process of selecting a Chief Aeronaut, rather it became a free-for-all in attempts to attract the attention of any officials in either the government or the military. In actuality the use of balloons was left to the discretion of the commanding generals through a process of trial and error based on the best recommendations of the balloonists themselves. Of those seeking the position, only two were given actual opportunities to perform combat aerial reconnaissance, Prof. Thaddeus Lowe and Mr. John LaMountain.

Thaddeus Lowe

Professor

Professor Thaddeus S. C. Lowe

Thaddeus Sobieski Constantine Lowe (August 20, 1832 – January 16, 1913), also known as Professor T. S. C. Lowe, was an American Civil War aeronaut, scientist and inventor, mostly self-educated in the fields of chemistry, meteorology, and ...

was one of the top American balloonists who sought the position of Chief Aeronaut for the Union Army. Also vying for the position were Prof. John Wise, Prof. John LaMountain, and Ezra and James Allen. All these men were aeronauts of extraordinary qualification in aviation of the day. Among them Lowe stood out as the most successful in balloon building and the closest to making a transatlantic flight. His scientific record was held in high regard among colleagues of the day, to include one Prof. Joseph Henry

Joseph Henry (December 17, 1797– May 13, 1878) was an American scientist who served as the first Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution. He was the secretary for the National Institute for the Promotion of Science, a precursor of the Smith ...

of the Smithsonian Institution

The Smithsonian Institution ( ), or simply the Smithsonian, is a group of museums and education and research centers, the largest such complex in the world, created by the U.S. government "for the increase and diffusion of knowledge". Founded ...

, who became his greatest benefactor.

On Henry's and others' recommendations, Lowe was contacted by Secretary of the Treasury

The United States secretary of the treasury is the head of the United States Department of the Treasury, and is the chief financial officer of the federal government of the United States. The secretary of the treasury serves as the principal a ...

Salmon P. Chase

Salmon Portland Chase (January 13, 1808May 7, 1873) was an American politician and jurist who served as the sixth chief justice of the United States. He also served as the 23rd governor of Ohio, represented Ohio in the United States Senate, a ...

, who invited him to Washington for an audience with Secretary of War

The secretary of war was a member of the U.S. president's Cabinet, beginning with George Washington's administration. A similar position, called either "Secretary at War" or "Secretary of War", had been appointed to serve the Congress of the ...

Simon Cameron

Simon Cameron (March 8, 1799June 26, 1889) was an American businessman and politician who represented Pennsylvania in the United States Senate and served as United States Secretary of War under President Abraham Lincoln at the start of the Americ ...

and the President. On 11 June 1861, Lowe was received by Lincoln and immediately offered to give the President a live demonstration with the balloon.

On Saturday, 16 June, with his own balloon, the ''Enterprise'', Lowe ascended some above the Columbian Armory with a telegraph

Telegraphy is the long-distance transmission of messages where the sender uses symbolic codes, known to the recipient, rather than a physical exchange of an object bearing the message. Thus flag semaphore is a method of telegraphy, whereas p ...

key and operator, and a wire following a tether line to the White House across the street. From aloft he transmitted the message:

Lowe's first assignment was with the Topographical Engineers, where his balloon was used for aerial observations and map making. Eventually he worked with Major General Irvin McDowell

Irvin McDowell (October 15, 1818 – May 4, 1885) was a career American army officer. He is best known for his defeat in the First Battle of Bull Run, the first large-scale battle of the American Civil War. In 1862, he was given command ...

, who rode along with Lowe making preliminary observations over the battlefield at Bull Run. McDowell became impressed with Lowe and his balloon, and a good word reached the President, who personally introduced Lowe to Union General-in-Chief Winfield Scott

Winfield Scott (June 13, 1786May 29, 1866) was an American military commander and political candidate. He served as a general in the United States Army from 1814 to 1861, taking part in the War of 1812, the Mexican–American War, the early s ...

. "General, this is my friend Professor Lowe who is organizing an aeronautics corps and who is to be its chief. I wish you would facilitate his work in every way." This introduction fairly well settled the selection of Lowe as Chief Aeronaut. The details of establishing the corps and its method of operation were left up to Lowe. The misunderstanding that the Balloon Corps would remain a civilian contract lasted its duration, and neither Lowe nor any of his men ever received commissions.

John Wise

John WiseCentennial of flightwas an early pioneer of American ballooning born in 1808. Although he made great contributions to the then newborn science of aeronautics, he was more a showman than a scientist. His attempts at free flight in preparation for a transatlantic crossing were less than successful, and he did not receive the same type of financial support from the patrons of the sciences, nor did he carry the overall scientific credibility of Lowe. Wise was, however, taken seriously enough by the

Topographical Engineers

The U.S. Army Corps of Topographical Engineers was a branch of the United States Army authorized on 4 July 1838. It consisted only of officers who were handpicked from West Point and was used for mapping and the design and construction of federal ...

to be asked to build a balloon. Mary Hoehling indicated that Captain Whipple of the Topographical Engineers told Lowe that Wise was preparing to bring up his own balloon, supposedly the ''Atlantic.'' Other accounts state that John LaMountain had taken possession of the ''Atlantic'' after a failed flight he made with Wise in 1859, and later place the ''Atlantic'' with LaMountain at Fort Monroe. Lowe's report says that Captain Whipple indicated they had instructed Mr. Wise to construct a new balloon. He also proposed that Lowe pilot the new balloon. Prof. Lowe was vehemently opposed to flying one of Wise's old-style balloons.

The engineers waited the whole month of July for Wise to arrive on scene. By 19 July 1861, McDowell started calling for a balloon to be brought to the front at First Bull Run

The First Battle of Bull Run (the name used by Union forces), also known as the Battle of First Manassas

( Centreville). As Wise was not to be found, Whipple sent Lowe out to inflate his balloon and prepare to set out for Falls Church. Mary Hoehling tells of the sudden appearance of John Wise who demanded that Lowe stop his inflating of the ''Enterprise'' and let him inflate his balloon instead. Wise had legal papers upholding his purported authority. Although Wise's arrival on the scene was tardy, he did inflate his balloon and proceeded toward the battlefield. On the way the balloon became caught in the brush and was permanently disabled. This ended Wise's bid for the position, and Lowe was at last unencumbered from taking up the task.

Lowe describes the inflation incident in his official report less dramatically, saying that he was told by the gas plant supervisor to disconnect and let another balloon go first. Lowe did not name names, but it is not likely that it was anyone other than Wise. Lowe's report about a new balloon has to be considered over Hoehling's account of the ''Atlantic.''

John LaMountain

John LaMountain, born in 1830, had accrued quite a reputation in the field of aeronautics. He had joined company with Wise at one time to help with the plans for a transatlantic flight. Their attempt failed miserably, wrecked their balloon, the ''Atlantic'', and ended their partnership. LaMountain took possession of the balloon. LaMountain's contributions and successes were minimal. However, he did attract the attention of GeneralBenjamin Butler

Benjamin Franklin Butler (November 5, 1818 – January 11, 1893) was an American major general of the Union Army, politician, lawyer, and businessman from Massachusetts. Born in New Hampshire and raised in Lowell, Massachusetts, Butler is best ...

at Fort Monroe

Fort Monroe, managed by partnership between the Fort Monroe Authority for the Commonwealth of Virginia, the National Park Service as the Fort Monroe National Monument, and the City of Hampton, is a former military installation in Hampton, Virgi ...

. LaMountain operated at Fort Monroe for a while with the battered ''Atlantic'' and was actually accredited with having made the first effective wartime observations from an aerial position. He also obtained use of a balloon, the ''Saratoga'', which he soon lost in a windstorm. LaMountain advocated free flight balloon reconnaissance, whereas Lowe used captive or tethered flight, remaining always attached to a ground crew who could reel him in.

Wise and LaMountain had been longtime detractors of Prof. Lowe, but LaMountain maintained a vitriolic campaign against Lowe to discredit him and usurp his position as Chief Aeronaut. He used the arena of public opinion to revile Lowe. But as Gen. Butler was replaced at Fort Monroe, LaMountain was assigned to the Balloon Corps under Lowe's command. LaMountain continued his public derogation of Lowe as well as creating ill-will among the other men in the Corps. Lowe lodged a formal complaint to Gen. George B. McClellan

George Brinton McClellan (December 3, 1826 – October 29, 1885) was an American soldier, Civil War Union general, civil engineer, railroad executive, and politician who served as the 24th governor of New Jersey. A graduate of West Point, McCl ...

, and by February 1862 LaMountain was discharged from military service.

Free flight vs. captive flight

There were two methods of piloting balloons: free flight or captive. Free flight meant that the balloon was able to travel in any direction or distance for as long or as far as the pilot was able to fly it. Captive flight meant that the balloon was retained by a tether or series of tethers manned by ground crews. Free flight required that the pilot ascend and return by his own control. Captive flight used ground crews to assist in altitude control and speedy return to the exact starting point. Tethers also allowed for the stringing of telegraph wires back to the ground. Information gathered from balloon observation was relayed to the ground by various means of signaling. From high altitudes the telegraph was almost always necessary. At closer altitudes a series of prepared flag signals, hand signals, or even a megaphone could be used to communicate with the ground. At night either the telegraph or lamps could be used. In the later battles of Lowe's tenure, all reports and communications were ordered to be made orally by ascending and descending with the balloon. This is notable in Lowe's Official Report II to the Secretary where his usual transcriptions of messages were lacking. Free flight would almost always require the aeronaut to return and make a report. This would be an obvious detriment to timely reporting. LaMountain and Lowe had long argued over free flight and captive flight. In Lowe's first instance of demonstration at Bull Run, he made a free flight which caught him hovering over Union encampments who could not properly identify him. As a civilian he wore no uniform nor insignias. With each descent came the threat of being fired on, and to make each descent Lowe needed to release gas. In one instance Lowe was forced to land behind enemy lines and await being rescued overnight. After this incident he remained tethered to the ground by which he could be reeled in at a moment's notice. Besides, his use of the telegraph from the balloon car required a wire be run along the tether. LaMountain, from his position at Fort Monroe, had the luxury of flying free. When he was enjoined with the Balloon Corps, he began insisting that his reconnaissance flights be made free. Lowe strictly instructed his men against free flight as a matter of policy and procedure. Eventually the two men agreed to a showdown in which LaMountain made one of his free flights. The flight was a success as a reconnaissance flight with LaMountain being able to go where he would. But on his return he was threatened by Union troops who could not identify him. His balloon was shot down, and LaMountain was treated harshly until he was clearly identified. Lowe considered the incident an argument against free flight. LaMountain insisted that the flight was highly successful despite the unfortunate incident. The showdown did nothing to settle the argument, but Lowe's position as Chief Aeronaut allowed him to prevail.Building military balloons

Lowe believed that balloons used for military purposes had to be better constructed than the common balloons used by civilian aeronauts. They also required special handling and care for use on the battlefield. At first the balloons of the day were inflated at municipalcoke gas

Coke usually refers to:

* Coca-Cola, a brand of soft drink

**The Coca-Cola Company

* Slang term for cocaine, a psychoactive substance and illicit drug

Substances Soft drinks

*Cola, any soft drink similar to Coca-Cola

* Generic name for a soft dr ...

supply stations and were towed inflated by ground crews to the field. Lowe recognized the need for the development of portable hydrogen gas generators, by which the balloons could be filled in the field. Lowe had to deal with administrative officers who usually held ranks lower than major and had more interest in accounting than providing for a proper war effort. This caused delays in the funding of materials.

Lowe was called out for another demonstration mission that would change the effective use of field artillery. On 24 September 1861, he was directed to position himself at Fort Corcoran

Fort Corcoran was a wood-and-earthwork fortification constructed by the Union Army in northern Virginia as part of the defenses of Washington, D.C. during the American Civil War. Built in 1861, shortly after the occupation of Arlington, Virginia b ...

, south of Washington, to ascend and overlook the Confederate encampments at Falls Church, Virginia, at a distance further south. A concealed Union artillery battery was remotely located at Camp Advance. Lowe was to give flag signal directions to the artillery, who would fire blindly on Falls Church. Each signal would indicate adjustments to the left, to the right, long or short. Simultaneously reports were telegraphed down to headquarters at the fort. With only a few corrections, the battery was soon landing rounds right on target. This was the precursor to the use of the artillery forward observer (FO).

The next day, Lowe received orders to build four proper balloons with hydrogen gas generators. Lowe went to work at his Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Sinc ...

facility. He was given funding to order India silk

Silk is a natural protein fiber, some forms of which can be woven into textiles. The protein fiber of silk is composed mainly of fibroin and is produced by certain insect larvae to form cocoons. The best-known silk is obtained from the coc ...

and cotton cording he had proposed for their construction. Along with that came Lowe's undisclosed recipe for a varnish

Varnish is a clear transparent hard protective coating or film. It is not a stain. It usually has a yellowish shade from the manufacturing process and materials used, but it may also be pigmented as desired, and is sold commercially in various ...

that would render the balloon envelopes leakproof.

The generators were built at the

The generators were built at the Washington Navy Yard

The Washington Navy Yard (WNY) is the former shipyard and ordnance plant of the United States Navy in Southeast Washington, D.C. It is the oldest shore establishment of the U.S. Navy.

The Yard currently serves as a ceremonial and administrativ ...

by master joiners who fashioned a contraption of copper plumbing and tanks which, when filled with sulfuric acid

Sulfuric acid (American spelling and the preferred IUPAC name) or sulphuric acid ( Commonwealth spelling), known in antiquity as oil of vitriol, is a mineral acid composed of the elements sulfur, oxygen and hydrogen, with the molecular formu ...

and iron filings, would yield hydrogen gas. The generators were Lowe's own design and were considered a marvel of engineering. They were designed to be loaded into box crates that could easily fit on a standard buckboard

A buckboard is a four-wheeled wagon of simple construction meant to be drawn by a horse or other large animal. A distinctly American utility vehicle, the buckboard has no springs between the body and the axles. The suspension is provided by the f ...

. The generators took more time to build than the balloons and were not as readily available as the first balloon.

By 1 October 1861, the first balloon, the ''Union'', was ready for action. Though it lacked a portable gas generator, it was called into immediate service. It was gassed up in Washington and towed overnight to Lewinsville via Chain Bridge

A chain bridge is a historic form of suspension bridge for which chains or eyebars were used instead of wire ropes to carry the bridge deck. A famous example is the Széchenyi Chain Bridge in Budapest.

Construction types are, as for other suspens ...

. The fully covered and trellised bridge required that the towing handlers crawl over the bridge beams and stringers to cross the upper Potomac River

The Potomac River () drains the Mid-Atlantic United States, flowing from the Potomac Highlands into Chesapeake Bay. It is long,U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map. Retrieved Augus ...

into Fairfax County

Fairfax County, officially the County of Fairfax, is a county in the Commonwealth of Virginia. It is part of Northern Virginia and borders both the city of Alexandria and Arlington County and forms part of the suburban ring of Washington, D.C. ...

. The balloon and crew arrived by daylight, exhausted from the nine-hour overnight ordeal, when a gale-force wind took the balloon away. It was later recovered, but not before Lowe, who was humiliated by the incident, went on a tirade about the delays in providing proper equipment.

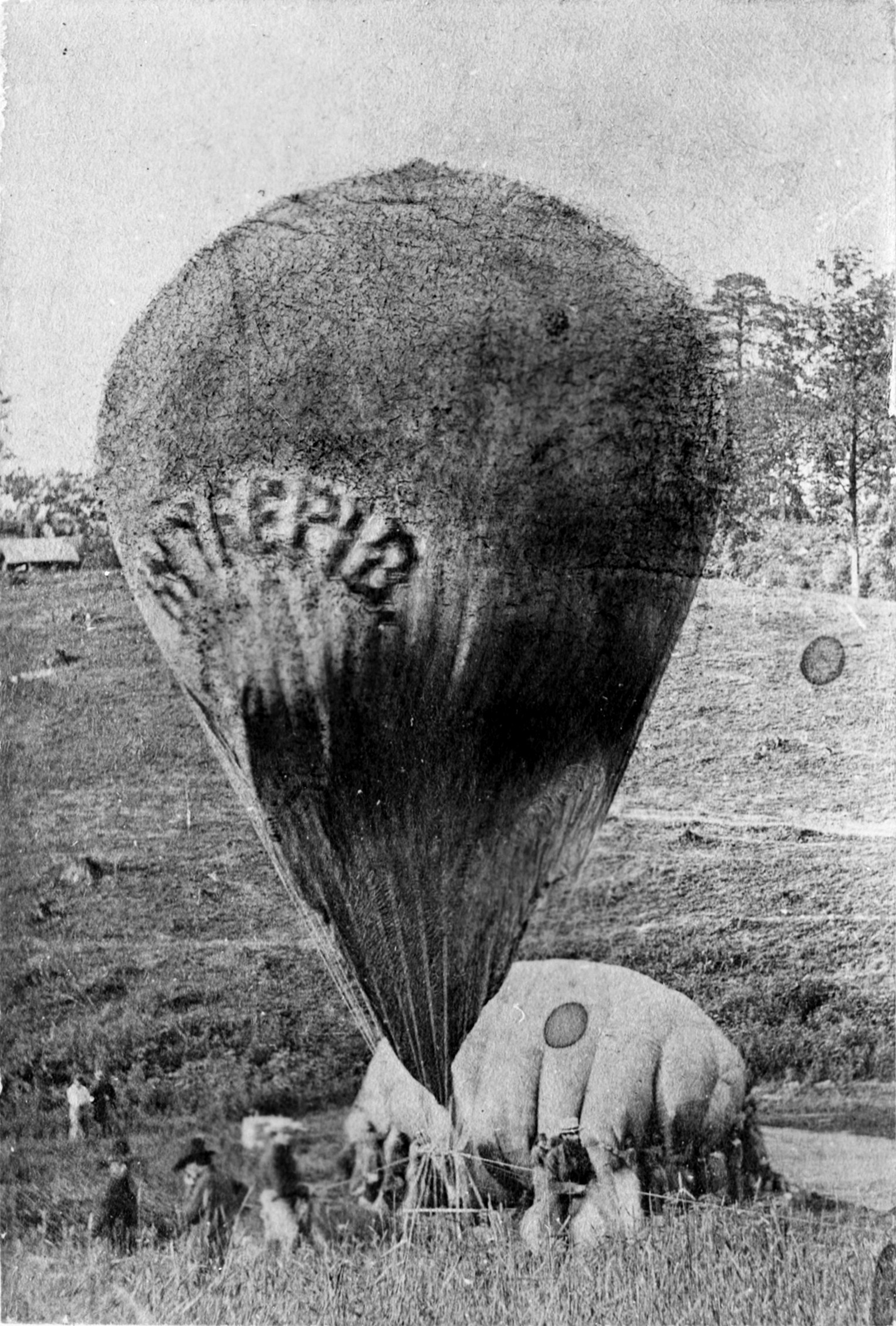

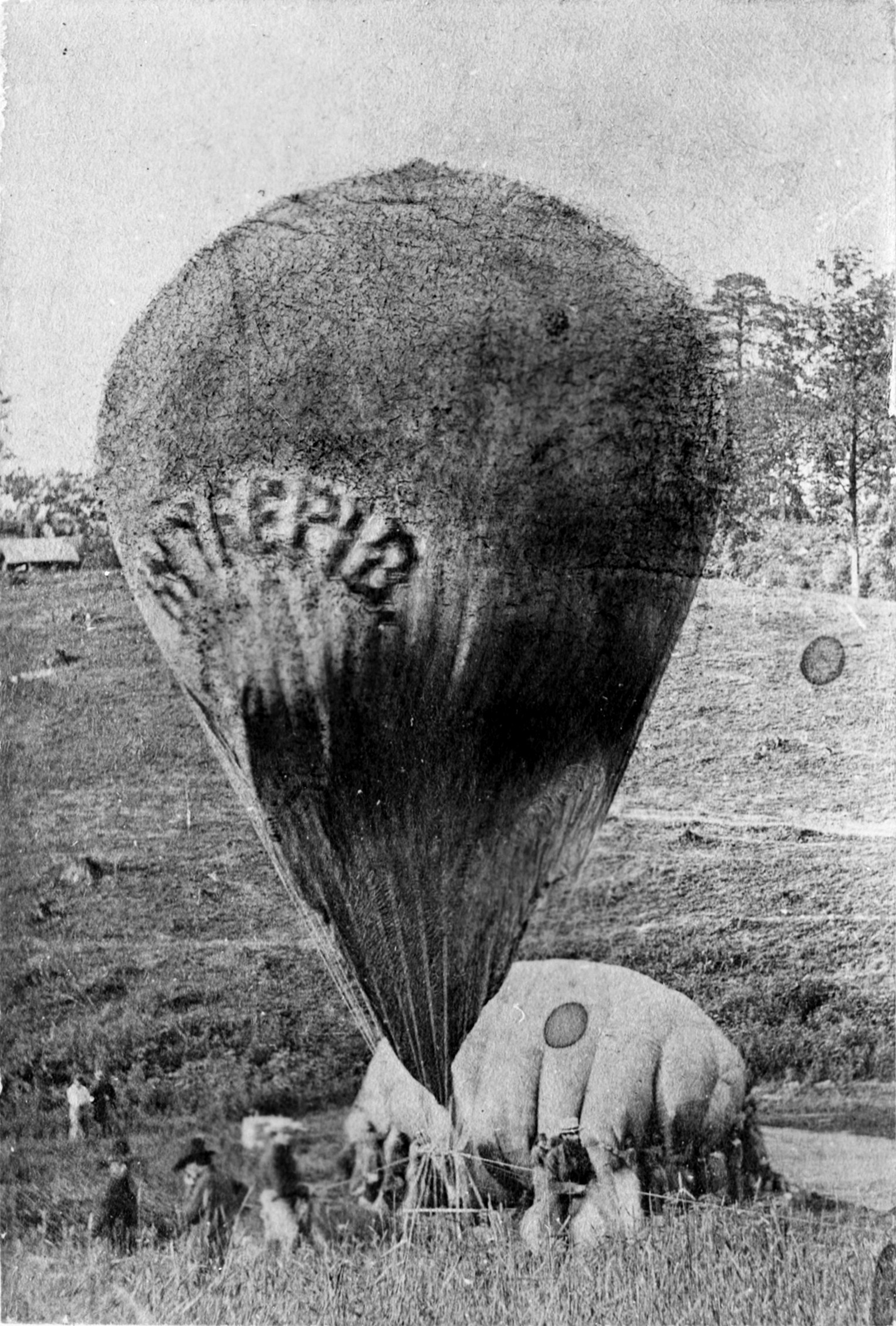

Lowe built seven balloons, six of which were put into service. Each balloon was accompanied by two gas generating sets. The smaller balloons were used in windier weather, or for quick, one-man, low altitude ascents. They inflated quickly since they required less gas. They were:

:*''Eagle''

:*''Constitution''

:*''Washington''

The larger balloons were used for carrying more weight, such as a telegraph key set and an additional man as an operator. They could also ascend higher. They were:

:*''Union''

:*'' Intrepid'' (Lowe's favorite balloon)

:*''Excelsior''

:*''United States''

The latter two balloons were held in storage in a Washington warehouse. Eventually the ''Excelsior'' was sent to Camp Lowe, a high altitude observation point, as a back-up balloon to the ''Intrepid'' during harsh winter weather, but the ''United States'' was never put into service. LaMountain made reference to these two balloons in his diatribes against Lowe as "being hoarded" by Lowe so he could buy them unused at the end of the war.

Lowe built seven balloons, six of which were put into service. Each balloon was accompanied by two gas generating sets. The smaller balloons were used in windier weather, or for quick, one-man, low altitude ascents. They inflated quickly since they required less gas. They were:

:*''Eagle''

:*''Constitution''

:*''Washington''

The larger balloons were used for carrying more weight, such as a telegraph key set and an additional man as an operator. They could also ascend higher. They were:

:*''Union''

:*'' Intrepid'' (Lowe's favorite balloon)

:*''Excelsior''

:*''United States''

The latter two balloons were held in storage in a Washington warehouse. Eventually the ''Excelsior'' was sent to Camp Lowe, a high altitude observation point, as a back-up balloon to the ''Intrepid'' during harsh winter weather, but the ''United States'' was never put into service. LaMountain made reference to these two balloons in his diatribes against Lowe as "being hoarded" by Lowe so he could buy them unused at the end of the war.

Establishing the Corps

Initially, Lowe was offered $30 per day for each day his balloon was in use. Lowe offered to accept $10 gold per day (colonel's pay) if he were to be allowed to build more suitable balloons. He was also allowed to hire as many men as he needed for $3 currency per day. Lowe was able to enlist his father, Clovis Lowe, an accomplished balloonist; Captain Dickinson, a seafaring volunteer from his days of transatlantic attempts; the Allen brothers, who had lost their own balloon when they were vying for the top job; two men the Allen brothers recommended, Eben Seaver and J. B. Starkweather; William Paullin, an older Philadelphia colleague; German balloonist John Steiner; and Ebenezer Mason, Lowe's construction supervisor, who requested active duty. Lowe set up several locations for the balloons—Fort Monroe, Washington D.C., Camp Lowe nearHarpers Ferry

Harpers Ferry is a historic town in Jefferson County, West Virginia. It is located in the lower Shenandoah Valley. The population was 285 at the 2020 census. Situated at the confluence of the Potomac and Shenandoah rivers, where the U.S. stat ...

—but always kept himself at the battle front. He served General McClellan at Yorktown until the Confederates retreated toward Richmond

Richmond most often refers to:

* Richmond, Virginia, the capital of Virginia, United States

* Richmond, London, a part of London

* Richmond, North Yorkshire, a town in England

* Richmond, British Columbia, a city in Canada

* Richmond, California, ...

. The heavily forested Virginia Peninsula

The Virginia Peninsula is a peninsula in southeast Virginia, USA, bounded by the York River, James River, Hampton Roads and Chesapeake Bay. It is sometimes known as the ''Lower Peninsula'' to distinguish it from two other peninsulas to the ...

forced him to take to the waterways. Balloon service was requested at more remote locations as well. Eben Seaver was assigned to take the ''Eagle'' to the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson Bay drainage system. From its traditional source of Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota, it f ...

to assist in battlefronts there. Mr. Starkweather was sent to Port Royal

Port Royal is a village located at the end of the Palisadoes, at the mouth of Kingston Harbour, in southeastern Jamaica. Founded in 1494 by the Spanish, it was once the largest city in the Caribbean, functioning as the centre of shipping and co ...

with the ''Washington'' just prior to the Peninsula Campaign.

First aircraft carrier

The ''General Washington Parke Custis'', a converted coal barge, had its deck cleared of all items that could entangle the ropes and nets of the balloons, and it was used as a river transport for the Corps. Lowe had two gas generators and a balloon loaded aboard and later reported:

The ''General Washington Parke Custis'', a converted coal barge, had its deck cleared of all items that could entangle the ropes and nets of the balloons, and it was used as a river transport for the Corps. Lowe had two gas generators and a balloon loaded aboard and later reported:

Peninsula Campaign

The battlefront turned toward

The battlefront turned toward Richmond

Richmond most often refers to:

* Richmond, Virginia, the capital of Virginia, United States

* Richmond, London, a part of London

* Richmond, North Yorkshire, a town in England

* Richmond, British Columbia, a city in Canada

* Richmond, California, ...

in the Peninsula Campaign. The heavy forestation inhibited the use of balloons, so Lowe and his Balloon Corps, with the use of three of his balloons, the ''Constitution'', the ''Washington'', and the larger ''Intrepid'', used the waterways to make its way inland. In mid May 1862, Lowe arrived at the White House on the Pamunkey River

The Pamunkey River is a tributary of the York River, about long,U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map accessed April 1, 2011 in eastern Virginia in the United States. Via the York Rive ...

. This is the first home of George

George may refer to:

People

* George (given name)

* George (surname)

* George (singer), American-Canadian singer George Nozuka, known by the mononym George

* George Washington, First President of the United States

* George W. Bush, 43rd Presid ...

and Martha Washington

Martha Dandridge Custis Washington (June 21, 1731 — May 22, 1802) was the wife of George Washington, the first president of the United States. Although the title was not coined until after her death, Martha Washington served as the inaugural ...

, after which the Washington presidential residence is named. At this time, it was the home of the son of Robert E. Lee, whose family fled at the arrival of Lowe. Lowe was met by McClellan's Army a few days later, and by 18 May, he had set up a balloon camp at Gaines' Farm across the Chickahominy River

The Chickahominy is an U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map, accessed April 1, 2011 river in the eastern portion of the U.S. state of Virginia. The river, which serves as the eastern bo ...

north of Richmond, and another at Mechanicsville. From these vantage points, Lowe, his assistant James Allen, and his father Clovis were able to overlook the Battle of Seven Pines

The Battle of Seven Pines, also known as the Battle of Fair Oaks or Fair Oaks Station, took place on May 31 and June 1, 1862, in Henrico County, Virginia, nearby Sandston, as part of the Peninsula Campaign of the American Civil War. It was t ...

.

Samuel P. Heintzelman

Samuel Peter Heintzelman (September 30, 1805 – May 1, 1880) was a United States Army general. He served in the Seminole War, the Mexican–American War, the Yuma War and the Cortina Troubles. During the American Civil War he was a prominent figu ...

's corps crossed the river toward Richmond and was slowly being surrounded by elements of the Confederate Army. McClellan felt that the Confederates were simply feigning an attack. Lowe could see, from his better vantage point, that they were converging on Heintzelman's position. Heintzelman was cut off from the main body because the swollen river had taken out all the bridges. Lowe sent urgent word of Heintzelman's predicament and recommended immediate repair of New Bridge and reinforcements for him.

At the same time, he sent over an order for the inflation of the ''Intrepid'', a larger balloon that could take him higher with telegraph equipment, in order to oversee the imminent battle. When Lowe arrived from Mechanicsville to the site of the ''Intrepid'' at Gaines' Mill, he saw that the aerostat's envelope was an hour away from being fully inflated. He then called for a camp kettle to have the bottom cut out of it, and he hooked the valve ends of the ''Intrepid'' and the ''Constitution'' together. He had the gas of the ''Constitution'' transferred to the ''Intrepid'' and was up in the air in 15 minutes. From this new vantage point, Lowe was able to report on all the Confederate movements. McClellan took Lowe's advice, repaired the bridge, and had reinforcements sent to Heintzelman's aid. An account of the battle was being witnessed by the visiting Count de Joinville who at day's end addressed Lowe with: "You, sir, have saved the day!"

Confederate Army's counter

Because of the effectiveness of the Union Army Balloon Corps, the Confederates felt compelled to incorporate balloons as well. Since coke gas was not readily available in Richmond, the first balloons were made of theMontgolfier

The Montgolfier brothers – Joseph-Michel Montgolfier (; 26 August 1740 – 26 June 1810) and Jacques-Étienne Montgolfier (; 6 January 1745 – 2 August 1799) – were aviation pioneers, balloonists and paper manufacturers from the commune A ...

rigid style: cotton stretched over wood framing and filled with hot smoke from fires made of oil-soaked pine cones. They were piloted by Captain John R. Bryan for use at Yorktown. Bryan's handlers were poorly experienced, and his balloon began spinning in the air. In another incident, one of the handlers became entangled in the ascending tether rope which had to be chopped loose, leaving the captain free-flying over his own Confederate positions whose troops threatened to shoot him down.

Attempts at making gas-filled silk

Silk is a natural protein fiber, some forms of which can be woven into textiles. The protein fiber of silk is composed mainly of fibroin and is produced by certain insect larvae to form cocoons. The best-known silk is obtained from the coc ...

balloons were hampered by the South's inability to obtain any imports at all. They did fashion a balloon from dress silk. Evans cites excerpts from Confederate letters that stated their balloons were made from dress-making silk and not dresses themselves. As it was put: "... not a single Southern Belle

Southern belle () is a colloquialism for a debutante in the planter class of the Antebellum South.

Characteristics

The image of a Southern belle is often characterized by fashion elements such as a hoop skirt, a corset, pantalettes, a wide-b ...

was asked to give up her Sunday best for the cause." Eugene Block quotes a letter that Lowe received from Confederate Major General James Longstreet

James Longstreet (January 8, 1821January 2, 1904) was one of the foremost Confederate generals of the American Civil War and the principal subordinate to General Robert E. Lee, who called him his "Old War Horse". He served under Lee as a corps ...

asserting that they were sent out to gather up all the silk dresses to be found to fashion a balloon:

The silk material balloon used by the Confederates was of a design by Dr. Edward Cheves of Savannah, Georgia. Dr. Cheves had the silk material sewn together by seamstresses and then covered the silk material with a varnish made by melting rubber in oil. The balloon was filled with a coal gas and launched from a railroad car that its pilot, Edward Porter Alexander

Edward Porter Alexander (May 26, 1835 – April 28, 1910) was an American military engineer, railroad executive, planter, and author. He served first as an officer in the United States Army and later, during the American Civil War (1861–1865) ...

, had positioned near the battlefield. In late June 1862, Alexander made a few ascents in the balloon and was able to signal his observations of the battlefield to men on the ground using a wigwag system that he had devised. The coal gas used in the balloon was only able to keep the balloon aloft for about three to four hours at a time.

The patchwork silk was given to Lowe, who had no use for it but to cut it up and distribute it to Congress as souvenirs. The inflated spheres appeared as multi-colored orbs over Richmond and were piloted by Captain Landon Cheeves. The balloon was loaded onto a primitive form of an aircraft carrier, the CSS Teaser

CSS ''Teaser'' had been the aging Georgetown, D.C. tugboat ''York River'' until the beginning of the American Civil War, when she was taken into the Confederate States Navy and took part in the famous Battle of Hampton Roads. Later, she was ...

. Before the first balloon could be used, it was captured by the crew of the USS ''Maratanza'' during transportation on the James River. A second balloon was put into action in the summer of 1863, when it was blown from its mooring and taken by Union forces and divided up as souvenirs for members of the Federal Congress. As the Union Army reduced its use of balloons, so did the Confederates.

Troubled Balloon Corps

During the Seven Days Battles in late June, McClellan's army was forced to retreat from the outskirts of Richmond. Lowe returned to Washington and he contractedmalaria

Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects humans and other animals. Malaria causes symptoms that typically include fever, tiredness, vomiting, and headaches. In severe cases, it can cause jaundice, seizures, coma, or death. S ...

in the swampy conditions and was out of service for a little more than a month. When he returned to duty, he found that all his wagons, mules, and service equipment had been returned to the Army Quartermaster. He was essentially out of a job. Lowe was ordered to join the Army for the Battle of Antietam

The Battle of Antietam (), or Battle of Sharpsburg particularly in the Southern United States, was a battle of the American Civil War fought on September 17, 1862, between Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia and Union G ...

, but he did not reach the battlefield until after the Confederates began their retreat to Virginia. Lowe had to reintroduce himself to the new commanding general of the Army of the Potomac, Ambrose Burnside

Ambrose Everett Burnside (May 23, 1824 – September 13, 1881) was an American army officer and politician who became a senior Union general in the Civil War and three times Governor of Rhode Island, as well as being a successful inventor ...

, who activated Lowe at the Battle of Fredericksburg

The Battle of Fredericksburg was fought December 11–15, 1862, in and around Fredericksburg, Virginia, in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. The combat, between the Union Army of the Potomac commanded by Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnsi ...

.

For all its success, the Balloon Corps was never fully appreciated by the military community. They were still regarded as carnival showmen. Others had little respect for their break-neck operation. The only ones who found any value in them were the generals whose jobs and reputations were on the line. Lower-ranking administrators looked with disdain on this band of civilians who, as they perceived them, had no place in the military. Furthermore, none of the corps ever received a military commission, leaving them facing the dangers of being captured and treated as spies, summarily punishable by death.

The Balloon Corps was eventually assigned to the Army Corps of Engineers and put under the administrative purview of one Captain Cyrus B. Comstock, who did not appreciate a civilian (Lowe) being paid more than he. He reduced Lowe's pay from $10 gold to $6 currency (equal to $3 gold) per day. Lowe posted a letter of outrage and threatened to resign his position. No one came to his support, and Comstock remained unyielding. On 8 April 1863, Lowe left the military service and returned to the private sector. Direction of the Balloon Corps defaulted to the Allen brothers, but they were not as competent as Lowe. By 1 August 1863, the Corps was no longer used.

After the Civil War

airship

An airship or dirigible balloon is a type of aerostat or lighter-than-air aircraft that can navigate through the air under its own power. Aerostats gain their lift from a lifting gas that is less dense than the surrounding air.

In early ...

(a dirigible, blimp

A blimp, or non-rigid airship, is an airship (dirigible) without an internal structural framework or a keel. Unlike semi-rigid and rigid airships (e.g. Zeppelins), blimps rely on the pressure of the lifting gas (usually helium, rather than hydr ...

, or zeppelin

A Zeppelin is a type of rigid airship named after the German inventor Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin () who pioneered rigid airship development at the beginning of the 20th century. Zeppelin's notions were first formulated in 1874Eckener 1938, pp ...

) came into existence with their motorized propulsion and mechanical means of steering. The United States Army Signal Corps

The United States Army Signal Corps (USASC) is a branch of the United States Army that creates and manages communications and information systems for the command and control of combined arms forces. It was established in 1860, the brainchild of Ma ...

established a War Balloon Company in 1893 at Fort Riley

Fort Riley is a United States Army installation located in North Central Kansas, on the Kansas River, also known as the Kaw, between Junction City and Manhattan. The Fort Riley Military Reservation covers 101,733 acres (41,170 ha) in Gear ...

, Kansas

Kansas () is a state in the Midwestern United States. Its capital is Topeka, and its largest city is Wichita. Kansas is a landlocked state bordered by Nebraska to the north; Missouri to the east; Oklahoma to the south; and Colorado to the ...

(at the time, home of the Signal School), and the next year at Fort Logan

Fort Logan was a military installation located eight miles southwest of Denver, Colorado. It was established in October 1887, when the first soldiers camped on the land, and lasted until 1946, when it was closed following the end of World War I ...

, Colorado, using a single balloon (the ''General Myer'') purchased in France. When that balloon deteriorated, members of the company sewed together a silk replacement in 1897. The balloon, dubbed the ''Santiago'', saw limited use in combat in 1898 during the Spanish–American War

, partof = the Philippine Revolution, the decolonization of the Americas, and the Cuban War of Independence

, image = Collage infobox for Spanish-American War.jpg

, image_size = 300px

, caption = (clock ...

.

Reports of Lowe's work in aeronautics and aerial reconnaissance were heard abroad. In 1864, Lowe was offered a Major-General position with the Brazilian Army, which was at war with Paraguay

Paraguay (; ), officially the Republic of Paraguay ( es, República del Paraguay, links=no; gn, Tavakuairetã Paraguái, links=si), is a landlocked country in South America. It is bordered by Argentina to the south and southwest, Brazil to th ...

, but he turned it down.

In the 19th century, the idea of dropping ordnance on the enemy from an aerial station was not seriously considered, although there was a patent issued to a Charles Perley in February 1863 for a bomb-dropping device that could be floated aloft by balloon. The balloon bomb was to be unmanned, and the plan was a theory which had no effective way of assuring that a bomb could be delivered and dropped remotely on the enemy. Also, as a civilian operation the Balloon Corps would have never been expected to drop ordnance.See also

* History of military ballooningNotes and references

Bibliography

* Block, Eugene B., ''Above the Civil War'', Howell-North Book, Berkeley, Ca., 1966. Library of Congress CC# 66-15640. * Evans, Charles M., "Air War over Virginia", ''Civil War Times'', October 1996. * Evans, Charles M., ''The War of the Aeronauts—A History of Ballooning During the Civil War'', Stackpole Books, Mechanicsburg, PA, 2002. * Haydon, F. Stansbury, ''Military Ballooning during the Early Civil War'', Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2000 * Hoehling, Mary, ''Thaddeus Lowe, America's One-Man Air Corps'', Julian Messner, Inc., New York, N. Y., 1958. Library of Congress CC# 58-7260. * Lowe, Thaddeus, ''Official Report (to the Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton) (PartI

(#11 & #12) O.R. - Series III - Volume III #124Correspondence, Orders, Reports, and Returns of the Union Authorities From 1 January to 31 December 1863''. * Manning, Mike, ''Intrepid, An Account of Prof. T.S.C. Lowe, Civil War Aeronaut and Hero'', self-published 2005. * Poleskie, Stephen, ''The Balloonist: The Story of T. S. C. Lowe—Inventor, Scientist, Magician, and Father of the U.S. Air Force'', Frederic C. Beil, 2007. * Seims, Charles, ''Mount Lowe, The Railway in the Clouds'', Golden West Books,

San Marino, California

San Marino is a residential city in Los Angeles County, California, United States. It was incorporated on April 25, 1913. At the 2010 census the population was 13,147. The city is one of the wealthiest places in the nation in terms of househol ...

, 1976. .

External links

Thaddeus Lowe website

{{American Civil War Balloon Corps Aviation units and formations of the United States Army Reconnaissance units and formations of the United States Army Balloon weaponry Balloons (aeronautics) Military units and formations established in 1861 1861 establishments in the United States Military units and formations disestablished in 1863