Underground Publications on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The terms underground press or clandestine press refer to periodicals and publications that are produced without official approval, illegally or against the wishes of a dominant (governmental, religious, or institutional) group.

In specific recent (post-World War II) Asian, American and Western European context, the term "underground press" has most frequently been employed to refer to the independently published and distributed underground papers associated with the

The terms underground press or clandestine press refer to periodicals and publications that are produced without official approval, illegally or against the wishes of a dominant (governmental, religious, or institutional) group.

In specific recent (post-World War II) Asian, American and Western European context, the term "underground press" has most frequently been employed to refer to the independently published and distributed underground papers associated with the

In Western Europe, a century after the invention of the printing press, a widespread underground press emerged in the mid-16th century with the clandestine circulation of

In Western Europe, a century after the invention of the printing press, a widespread underground press emerged in the mid-16th century with the clandestine circulation of

' s broadsheet format). Very quickly, the relaunched ''Oz'' shed its more austere satire magazine image and became a mouthpiece of the underground. It was the most colourful and visually adventurous of the alternative press (sometimes to the point of near-illegibility), with designers like

"The Underground Press and Its Extraordinary Moment in US History,"

''

University of Missouri Libraries. Accessed Dec. 29, 2016. The Rip Off Press Syndicate was launched 1973 to compete in selling underground comix content to the underground press and student publications.Fox, M. Steven

"Rip Off Comix — 1977-1991 / Rip Off Press,"

Comixjoint. Retrieved Dec. 5, 2022. Each Friday, the company sent out a distribution sheet with the strips it was selling, by such cartoonists as Gilbert Shelton, Bill Griffith, Joel Beck, Dave Sheridan (cartoonist), Dave Sheridan, Ted Richards (artist), Ted Richards, and Harry Driggs. The Liberation News Service (LNS), co-founded in the summer of 1967 by Ray Mungo and Marshall Bloom, "provided coverage of events to which most papers would have otherwise had no access." In a similar vein, John Berger (author), John Berger, Lee Marrs, and others co-founded Alternative Features Service, Inc. in 1970 to supply the underground and college press, as well as independent radio stations, with syndicated press materials that especially highlighted the creation of alternative institutions, such as free clinics, community bank, people's banks, free universities, and alternative housing. By 1973, many underground papers had folded, at which point the Underground Press Syndicate acknowledged the passing of the undergrounds and renamed itself the Alternative Press Syndicate (APS). After a few years, APS also foundered, to be supplanted in 1978 by the Association of Alternative Newsweeklies.

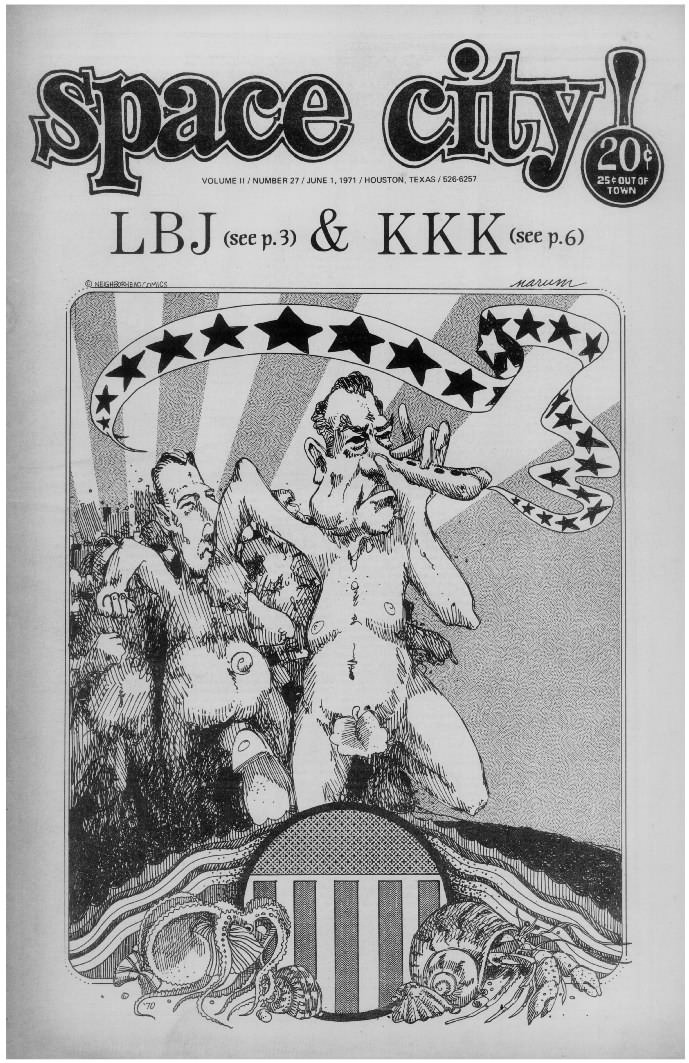

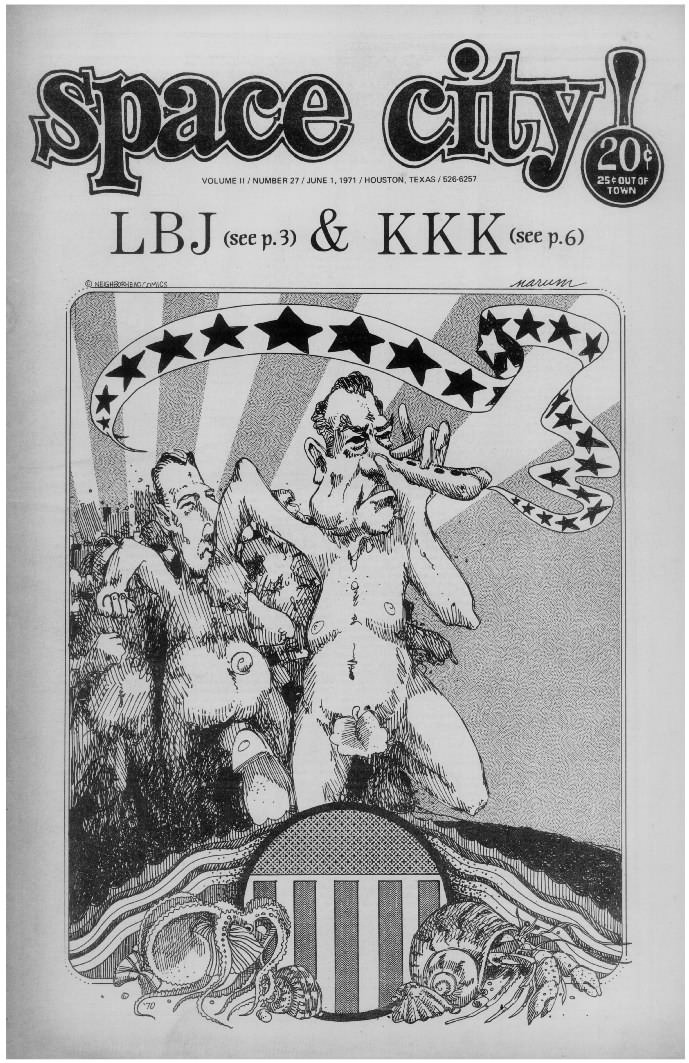

Drive-by shootings, firebombings, break-ins, and trashings were carried out on the offices of many underground papers around the country, fortunately without causing any fatalities. The offices of Houston's ''Space City (newspaper), Space City!'' were bombed and its windows repeatedly shot out. In Houston, as in many other cities, the attackers, never identified, were suspected of being off-duty military or police personnel, or members of the Ku Klux Klan or Minutemen (anti-Communist organization), Minuteman organizations.

Some of the most violent attacks were carried out against the underground press in San Diego. In 1976 the ''San Diego Union-Tribune, San Diego Union'' reported that the attacks in 1971 and 1972 had been carried out by a right-wing paramilitary group calling itself the Secret Army Organization, which had ties to the local office of the FBI.

The U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) conducted surveillance and disruption activities on the underground press in the United States, including a campaign to destroy the News agency (alternative), alternative agency Liberation News Service. As part of its COINTELPRO designed to discredit and infiltrate radical New Left groups, the FBI also launched phony underground newspapers such as the ''Armageddon News'' at Indiana University Bloomington, ''The Longhorn Tale'' at the University of Texas at Austin, and the ''Rational Observer'' at American University in Washington, D.C. The FBI also ran the Pacific International News Service in San Francisco, the Chicago Midwest News, and the New York Press Service. Many of these organizations consisted of little more than a post office box and a letterhead, designed to enable the FBI to receive exchange copies of underground press publications and send undercover observers to underground press gatherings.

Drive-by shootings, firebombings, break-ins, and trashings were carried out on the offices of many underground papers around the country, fortunately without causing any fatalities. The offices of Houston's ''Space City (newspaper), Space City!'' were bombed and its windows repeatedly shot out. In Houston, as in many other cities, the attackers, never identified, were suspected of being off-duty military or police personnel, or members of the Ku Klux Klan or Minutemen (anti-Communist organization), Minuteman organizations.

Some of the most violent attacks were carried out against the underground press in San Diego. In 1976 the ''San Diego Union-Tribune, San Diego Union'' reported that the attacks in 1971 and 1972 had been carried out by a right-wing paramilitary group calling itself the Secret Army Organization, which had ties to the local office of the FBI.

The U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) conducted surveillance and disruption activities on the underground press in the United States, including a campaign to destroy the News agency (alternative), alternative agency Liberation News Service. As part of its COINTELPRO designed to discredit and infiltrate radical New Left groups, the FBI also launched phony underground newspapers such as the ''Armageddon News'' at Indiana University Bloomington, ''The Longhorn Tale'' at the University of Texas at Austin, and the ''Rational Observer'' at American University in Washington, D.C. The FBI also ran the Pacific International News Service in San Francisco, the Chicago Midwest News, and the New York Press Service. Many of these organizations consisted of little more than a post office box and a letterhead, designed to enable the FBI to receive exchange copies of underground press publications and send undercover observers to underground press gatherings.

See Table: GI Underground Press (United States Military)#Table: GI Underground Press During the Vietnam War (U.S. Military), GI Underground Press During the Vietnam War (U.S. Military)

See Table: GI Underground Press (United States Military)#Table: GI Underground Press During the Vietnam War (U.S. Military), GI Underground Press During the Vietnam War (U.S. Military)

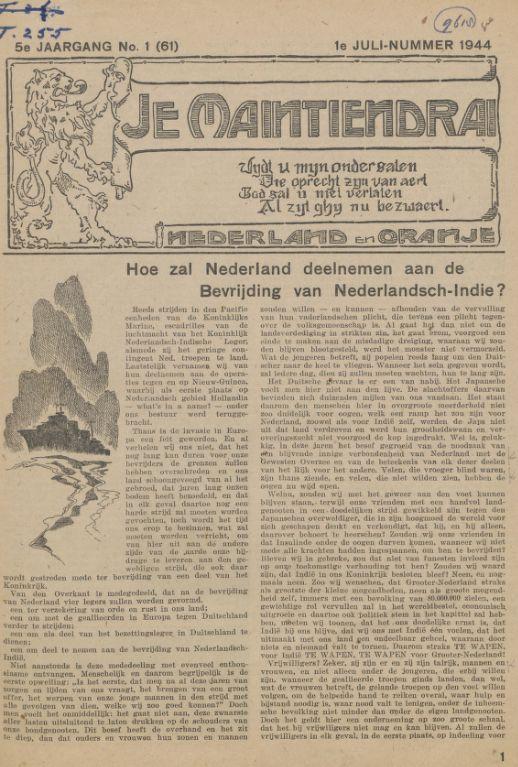

Clandestine press in the Netherlands is related to the second World War, which ran from 10 May 1940 until 5 May 1945 in the Netherlands.

* See the :w:nl:Lijst van verzetsbladen uit de Tweede Wereldoorlog, list of 1300 Dutch illegal WW2 newspapers on Dutch Wikipedia

* See also on Dutch Wikipedia

:* :w:nl:Lijst van uitgaveplaatsen van verzetsbladen tijdens de Tweede Wereldoorlog, List of places of publication of Dutch illegal WW2 newspapers

:* :w:nl:Lijst van drukkerijen en uitgeverijen van verzetsbladen gedurende de Tweede Wereldoorlog, List of printers and publishers of Dutch illegal WW2 newspapers

:* :w:nl:Lijst van legaal voortgezette verzetsbladen na de Tweede Wereldoorlog, List of legally continued Dutch WW2 newspapers

Clandestine press in the Netherlands is related to the second World War, which ran from 10 May 1940 until 5 May 1945 in the Netherlands.

* See the :w:nl:Lijst van verzetsbladen uit de Tweede Wereldoorlog, list of 1300 Dutch illegal WW2 newspapers on Dutch Wikipedia

* See also on Dutch Wikipedia

:* :w:nl:Lijst van uitgaveplaatsen van verzetsbladen tijdens de Tweede Wereldoorlog, List of places of publication of Dutch illegal WW2 newspapers

:* :w:nl:Lijst van drukkerijen en uitgeverijen van verzetsbladen gedurende de Tweede Wereldoorlog, List of printers and publishers of Dutch illegal WW2 newspapers

:* :w:nl:Lijst van legaal voortgezette verzetsbladen na de Tweede Wereldoorlog, List of legally continued Dutch WW2 newspapers

"The Underground GI Press: Pens Against the Pentagon,"

''Commonweal''. Reprinted in ''Duck Power'' vol. 1, no. 4.

''Voices from the Underground (Vol. 1): Insider Histories of the Vietnam Era Underground Press''

* Holhut, Randolph T. [http://www.brasscheck.com/seldes/history.html "A Brief History of American Alternative Journalism in the Twentieth Century,"] BrassCheck.com. Retrieved Dec. 15, 2022. * Thorne Webb Dreyer, Dreyer, Thorne and Victoria Smith

"The Movement and the New Media,"

Liberation News Service (1969).

Underground/Alternative Newspapers History and Geography

Maps and databases showing over 2,000 underground/alternative newspapers between 1965 and 1975 in the U.S. From the Mapping American Social Movements project at the University of Washington. * A number of libraries have extensive microfilm collections of underground newspapers. For example, th

University of Oregon

library has a collection that consists of mostly, but not exclusively North American underground papers.

Chicano Newspapers and Periodicals 1966-1979

Maps and charts showing over 300 Chicano newspapers from the 1960s and 70s

"Voices from the Underground," an exhibition of the North American underground press of the 1960s; includes a substantial gallery of color images

A digitally scanned archive of the first twelve issues (1966-67) of ''The Rag'', from Austin, Texas

Articles about the underground press at ''The Rag Blog''

(While ''The Avatar'' shared its design approach and many social concerns with other underground papers of the time, in one important respect it was completely atypical: it served as a platform for self-proclaimed "world saviour" Mel Lyman, leader of the Fort Hill Community.)

A collection of ''Space City News'' covers

by underground artist Bill Narum

The website for the film ''Sir! No Sir!''

has an extensive collection of primary source materials from the GI underground press

''The Truth''

, a specimen high school underground paper from 1969 ; U.K. underground press

by Gerry Carlin and Mark Jones

''International Times'' archive

''OZ magazine'', London, 1967-1973

online at the University of Wollongong Library ; Australian underground press

''The Digger'', 1972-1975

online at the University of Wollongong Library

''Nexus'' magazine (Australia)

''OZ magazine'', Sydney, 1963-1969

online at the University of Wollongong Library

Ozit.org

— history of ''OZ Magazine'' (archived site) ; European underground press

at stampamusicale.altervista.org

Underground press historian Sean Stewart on Rag Radio

Interviewed by Thorne Dreyer, August 31, 2010 (57:17)

Historian John McMillian, author of ''Smoking Typewriters: The Sixties Underground Press and the Rise of Alternative Media in America'' on Rag Radio

Interviewed by Thorne Dreyer, March 4, 2011 (42:18)

Thorne Dreyer's 24 hour-long Rag Radio interviews with veterans of the Sixties underground press

{{DEFAULTSORT:Underground press Underground press, Alternative press Alternative media

The terms underground press or clandestine press refer to periodicals and publications that are produced without official approval, illegally or against the wishes of a dominant (governmental, religious, or institutional) group.

In specific recent (post-World War II) Asian, American and Western European context, the term "underground press" has most frequently been employed to refer to the independently published and distributed underground papers associated with the

The terms underground press or clandestine press refer to periodicals and publications that are produced without official approval, illegally or against the wishes of a dominant (governmental, religious, or institutional) group.

In specific recent (post-World War II) Asian, American and Western European context, the term "underground press" has most frequently been employed to refer to the independently published and distributed underground papers associated with the counterculture

A counterculture is a culture whose values and norms of behavior differ substantially from those of mainstream society, sometimes diametrically opposed to mainstream cultural mores.Eric Donald Hirsch. ''The Dictionary of Cultural Literacy''. Hou ...

of the late 1960s and early 1970s in India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

and Bangladesh

Bangladesh (}, ), officially the People's Republic of Bangladesh, is a country in South Asia. It is the eighth-most populous country in the world, with a population exceeding 165 million people in an area of . Bangladesh is among the mos ...

in Asia, in the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

and Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by tot ...

in North America, and the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and North ...

and other western nations. It can also refer to the newspapers produced independently in repressive regimes. In German occupied Europe

German-occupied Europe refers to the sovereign countries of Europe which were wholly or partly occupied and civil-occupied (including puppet governments) by the military forces and the government of Nazi Germany at various times between 1939 an ...

, for example, a thriving underground press operated, usually in association with the Resistance. Other notable examples include the '' samizdat'' and ''bibuła

Polish underground press, devoted to prohibited materials ( sl. pl, bibuła, lit. semitransparent blotting paper or, alternatively, pl, drugi obieg, lit. second circulation), has a long history of combatting censorship of oppressive regimes in ...

'', which operated in the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

and Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populous ...

respectively, during the Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because the ...

.

Origins

In Western Europe, a century after the invention of the printing press, a widespread underground press emerged in the mid-16th century with the clandestine circulation of

In Western Europe, a century after the invention of the printing press, a widespread underground press emerged in the mid-16th century with the clandestine circulation of Calvinist

Calvinism (also called the Reformed Tradition, Reformed Protestantism, Reformed Christianity, or simply Reformed) is a major branch of Protestantism that follows the theological tradition and forms of Christian practice set down by John Ca ...

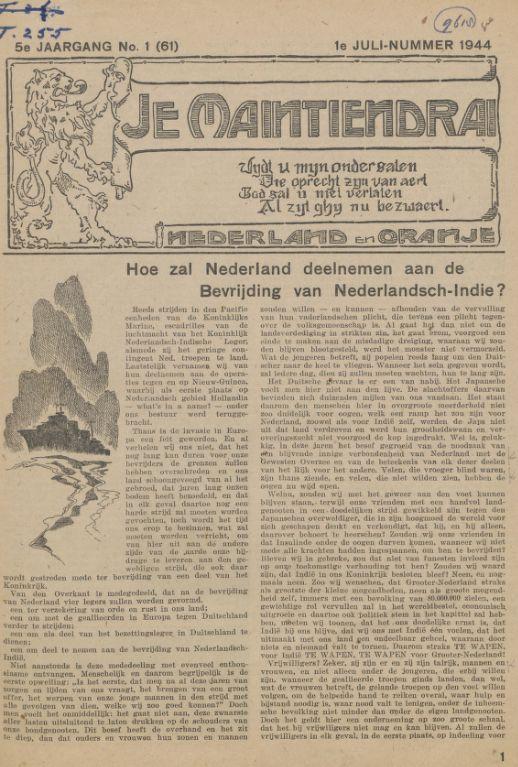

books and broadsides, many of them printed in Geneva, which were secretly smuggled into other nations where the carriers who distributed such literature might face imprisonment, torture or death. Both Protestant and Catholic nations fought the introduction of Calvinism, which with its emphasis on intractable evil made its appeal to alienated, outsider subcultures willing to violently rebel against both church and state. In 18th century France, a large illegal underground press of the Enlightenment emerged, circulating anti-Royalist, anti-clerical and pornographic works in a context where all published works were officially required to be licensed. Starting in the mid-19th century an underground press sprang up in many countries around the world for the purpose of circulating the publications of banned Marxist political parties; during the German Nazi occupation of Europe, clandestine presses sponsored and subsidized by the Allies were set up in many of the occupied nations, although it proved nearly impossible to build any sort of effective underground press movement within Germany itself.

The French resistance

The French Resistance (french: La Résistance) was a collection of organisations that fought the German occupation of France during World War II, Nazi occupation of France and the Collaborationism, collaborationist Vichy France, Vichy régim ...

published a large and active underground press that printed over 2 million newspapers a month; the leading titles were ''Combat

Combat ( French for ''fight'') is a purposeful violent conflict meant to physically harm or kill the opposition. Combat may be armed (using weapons) or unarmed ( not using weapons). Combat is sometimes resorted to as a method of self-defense, or ...

'', ''Libération

''Libération'' (), popularly known as ''Libé'' (), is a daily newspaper in France, founded in Paris by Jean-Paul Sartre and Serge July in 1973 in the wake of the protest movements of May 1968. Initially positioned on the far-left of France's ...

'', '' Défense de la France'', and '' Le Franc-Tireur.'' Each paper was the organ of a separate resistance network, and funds were provided from Allied headquarters in London and distributed to the different papers by resistance leader Jean Moulin

Jean Pierre Moulin (; 20 June 1899 – 8 July 1943) was a French civil servant and resistant who served as the first President of the National Council of the Resistance during World War II from 27 May 1943 until his death less than two months l ...

. Allied prisoners of war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person who is held Captivity, captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold priso ...

(POWs) published an underground newspaper called POW WOW

A powwow (also pow wow or pow-wow) is a gathering with dances held by many Native American and First Nations communities. Powwows today allow Indigenous people to socialize, dance, sing, and honor their cultures. Powwows may be private or pu ...

. In Eastern Europe

Eastern Europe is a subregion of the Europe, European continent. As a largely ambiguous term, it has a wide range of geopolitical, geographical, ethnic, cultural, and socio-economic connotations. The vast majority of the region is covered by Russ ...

, also since approximately 1940, underground publications were known by the name '' samizdat''.

The countercultural underground press movement of the 1960s borrowed the name from previous "underground presses" such as the Dutch underground press during the Nazi

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in ...

occupations of the 1940s. Those predecessors were truly "underground", meaning they were illegal, thus published and distributed covertly. While the countercultural "underground" papers frequently battled with governmental authorities, for the most part they were distributed openly through a network of street vendors, newsstands and head shop

A head shop is a retail outlet specializing in paraphernalia used for consumption of cannabis and tobacco and items related to cannabis culture and related countercultures. They emerged from the hippie counterculture in the late 1960s, and ...

s, and thus reached a wide audience.

The underground press in the 1960s and 1970s existed in most countries with high GDP per capita and freedom of the press

Freedom of the press or freedom of the media is the fundamental principle that communication and expression through various media, including printed and electronic News media, media, especially publication, published materials, should be conside ...

; similar publications existed in some developing countries and as part of the ''samizdat'' movement in the communist state

A communist state, also known as a Marxist–Leninist state, is a one-party state that is administered and governed by a communist party guided by Marxism–Leninism. Marxism–Leninism was the state ideology of the Soviet Union, the Comint ...

s, notably Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

. Published as weeklies, monthlies, or "occasionals", and usually associated with left-wing politics

Left-wing politics describes the range of Ideology#Political%20ideologies, political ideologies that support and seek to achieve social equality and egalitarianism, often in opposition to social hierarchy. Left-wing politics typically in ...

, they evolved on the one hand into today's alternative weeklies and on the other into zine

A zine ( ; short for '' magazine'' or '' fanzine'') is a small-circulation self-published

Self-publishing is the publication of media by its author at their own cost, without the involvement of a publisher. The term usually refers to writ ...

s.

In Australia

The most prominent underground publication in Australia was a satirical magazine called '' OZ'' (1963 to 1969), which initially owed a debt to local university student newspapers such as Honi Soit (University of Sydney) and Tharunka (University of New South Wales), along with the UK magazine ''Private Eye

''Private Eye'' is a British fortnightly satire, satirical and current affairs (news format), current affairs news magazine, founded in 1961. It is published in London and has been edited by Ian Hislop since 1986. The publication is widely r ...

''. The original edition appeared in Sydney on April Fools' Day, 1963 and continued sporadically until 1969. Editions published after February 1966 were edited by Richard Walsh, following the departure for the UK of his original co-editors Richard Neville Richard Neville may refer to:

*Richard Neville, 16th Earl of Warwick (1428–1471), "Warwick the Kingmaker", English noble, fought in the Wars of the Roses

*Richard Neville, 5th Earl of Salisbury (1400–1460), Yorkist leader during the Wars of the ...

and Martin Sharp

Martin Ritchie Sharp (21 January 1942 – 1 December 2013) was an Australian artist, cartoonist, songwriter and film-maker.

Career

Sharp was born in Bellevue Hill, New South Wales in 1942, and educated at Cranbrook private school, where one ...

, who went on to found a British edition (''London Oz'') in January 1967. In Melbourne Phillip Frazer, founder and editor of pop music magazine '' Go-Set'' since January 1966, branched out into alternate, underground publications with ''Revolution

In political science, a revolution (Latin: ''revolutio'', "a turn around") is a fundamental and relatively sudden change in political power and political organization which occurs when the population revolts against the government, typically due ...

'' in 1970, followed by ''High Times

''High Times'' is an American monthly magazine (and cannabis brand) that advocates the Legalization of non-medical cannabis in the United States, legalization of cannabis as well as other counterculture ideas. The magazine was founded in 1974 by ...

'' (1971 to 1972) and ''The Digger

''The Digger'' is a 24-page magazine in Glasgow, Scotland which focusses on crime stories. It is published weekly, in an A5 newsletter format. In 2012, the magazine went from newsprint to glossy.

Background

The magazine was founded by James C ...

'' (1972 to 1975).

List of Australian underground papers

* ''The Digger

''The Digger'' is a 24-page magazine in Glasgow, Scotland which focusses on crime stories. It is published weekly, in an A5 newsletter format. In 2012, the magazine went from newsprint to glossy.

Background

The magazine was founded by James C ...

'' (1972–1975)

* ''The Living Daylights

''The Living Daylights'' is a 1987 spy film, the fifteenth entry in the ''James Bond'' series produced by Eon Productions, and the first of two to star Timothy Dalton as the fictional MI6 agent James Bond. Directed by John Glen, the film's ...

'' (1973-1974)

* ''High Times

''High Times'' is an American monthly magazine (and cannabis brand) that advocates the Legalization of non-medical cannabis in the United States, legalization of cannabis as well as other counterculture ideas. The magazine was founded in 1974 by ...

'' (1971-1972)

* '' OZ Sydney'' (1963-1969)

* ''New Dawn'' magazine

* ''Nexus'' magazine

* ''Revolution

In political science, a revolution (Latin: ''revolutio'', "a turn around") is a fundamental and relatively sudden change in political power and political organization which occurs when the population revolts against the government, typically due ...

'' (1970-1971)

In the United Kingdom

The underground press offered a platform to the socially impotent and mirrored the changing way of life in the UK underground. InLondon

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a majo ...

, Barry Miles, John Hopkins, and others produced ''International Times

''International Times'' (''it'' or ''IT'') is the name of various underground newspapers, with the original title founded in London in 1966 and running until October 1973. Editors included John "Hoppy" Hopkins, David Mair ...

'' from October 1966 which, following legal threats from ''The Times'' newspaper was renamed ''IT''.

Richard Neville Richard Neville may refer to:

*Richard Neville, 16th Earl of Warwick (1428–1471), "Warwick the Kingmaker", English noble, fought in the Wars of the Roses

*Richard Neville, 5th Earl of Salisbury (1400–1460), Yorkist leader during the Wars of the ...

arrived in London from Australia, where he had edited '' Oz'' (1963 to 1969). He launched a British version (1967 to 1973), which was A4 (as opposed to ''IT''Martin Sharp

Martin Ritchie Sharp (21 January 1942 – 1 December 2013) was an Australian artist, cartoonist, songwriter and film-maker.

Career

Sharp was born in Bellevue Hill, New South Wales in 1942, and educated at Cranbrook private school, where one ...

.

Other publications followed, such as ''Friends

''Friends'' is an American television sitcom created by David Crane and Marta Kauffman, which aired on NBC from September 22, 1994, to May 6, 2004, lasting ten seasons. With an ensemble cast starring Jennifer Aniston, Courteney Cox, Lisa ...

'' (later ''Frendz''), based in the Ladbroke Grove

Ladbroke Grove () is an area and a road in West London in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea, passing through Kensal Green and Notting Hill, running north–south between Harrow Road and Holland Park Avenue.

It is also a name given to ...

area of London

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a majo ...

; ''Ink

Ink is a gel, sol, or solution that contains at least one colorant, such as a dye or pigment, and is used to color a surface to produce an image, text, or design. Ink is used for drawing or writing with a pen, brush, reed pen, or quill. Thi ...

'', which was more overtly political; and ''Gandalf's Garden Gandalf's Garden was a mystical community which flourished at the end of the 1960s as part of the London hippie-underground movement, and ran a shop and a magazine of the same name. It emphasised the mystical interests of the period, and advocated m ...

'' which espoused the mystic path.

Legal challenges

The flaunting of sexuality within the underground press provoked prosecution. ''IT'' was taken to court for publishing small ads for homosexuals; despite the 1967legalisation

Legalization is the process of removing a legal prohibition against something which is currently not legal.

Legalization is a process often applied to what are regarded, by those working towards legalization, as victimless crimes, of which one ...

of homosexuality between consenting adults in private, importuning remained subject to prosecution. Publication of the ''Oz'' "School Kids" issue brought charges against the three ''Oz'' editors, who were convicted and given jail sentences. This was the first time the Obscene Publications Act 1959 was combined with a moral conspiracy charge. The convictions were, however, overturned on appeal.

Harassment and intimidation

Police harassment of the British underground, in general, became commonplace, to the point that in 1967 the police seemed to focus in particular on the apparent source of agitation: the underground press. The police campaign may have had an effect contrary to that which was presumably intended. If anything, according to one or two who were there at the time, it actually made the underground press stronger. "It focused attention, stiffened resolve, and tended to confirm that what we were doing was considered dangerous to the establishment", remembered Mick Farren. From April 1967, and for some while later, the police raided the offices of ''International Times'' to try, it was alleged, to force the paper out of business. In order to raise money for ''IT'' a benefit event was put together, "The 14 Hour Technicolor Dream"Alexandra Palace

Alexandra Palace is a Grade II listed entertainment and sports venue in London, situated between Wood Green and Muswell Hill in the London Borough of Haringey. It is built on the site of Tottenham Wood and the later Tottenham Wood Farm. Origi ...

on 29 April 1967.

On one occasion – in the wake of yet another raid on ''IT'' – London's alternative press succeeded in pulling off what was billed as a 'reprisal attack' on the police. The paper ''Black Dwarf'' published a detailed floor-by-floor 'Guide to Scotland Yard

Scotland Yard (officially New Scotland Yard) is the headquarters of the Metropolitan Police, the territorial police force responsible for policing Greater London's 32 boroughs, but not the City of London, the square mile that forms London's ...

', complete with diagrams, descriptions of locks on particular doors, and snippets of overheard conversation. The anonymous author, or 'blue dwarf', as he styled himself, claimed to have perused archive files, and even to have sampled one or two brands of scotch in the Commissioner's office. The London ''Evening Standard

The ''Evening Standard'', formerly ''The Standard'' (1827–1904), also known as the ''London Evening Standard'', is a local free daily newspaper in London, England, published Monday to Friday in tabloid format.

In October 2009, after be ...

'' headlined the incident as "Raid on the Yard". A day or two later ''The Daily Telegraph

''The Daily Telegraph'', known online and elsewhere as ''The Telegraph'', is a national British daily broadsheet newspaper published in London by Telegraph Media Group and distributed across the United Kingdom and internationally.

It was fo ...

'' announced that the prank had resulted in all security passes to the police headquarters having to be withdrawn and then re-issued.

Support from British pop culture

By the end of the decade, community artists and bands such asPink Floyd

Pink Floyd are an English rock band formed in London in 1965. Gaining an early following as one of the first British psychedelic music, psychedelic groups, they were distinguished by their extended compositions, sonic experimentation, philo ...

(before they "went commercial"), The Deviants, Pink Fairies, Hawkwind, Michael Moorcock and Steve Peregrin Took would arise in a symbiotic co-operation with the underground press. The underground press publicised these bands and this made it possible for them to tour and get record deals. The band members travelled around spreading the ethos and the demand for underground newspapers and magazines grew and flourished for a while.

Neville published an account of the counterculture

A counterculture is a culture whose values and norms of behavior differ substantially from those of mainstream society, sometimes diametrically opposed to mainstream cultural mores.Eric Donald Hirsch. ''The Dictionary of Cultural Literacy''. Hou ...

called ''Play Power'', in which he described most of the world's underground publications. He also listed many of the regular key topics from those publications, including the Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (also known by #Names, other names) was a conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. It was the second of the Indochina Wars and was officially fought between North Vie ...

, Black Power, politics, police brutality

Police brutality is the excessive and unwarranted use of force by law enforcement against an individual or a group. It is an extreme form of police misconduct and is a civil rights violation. Police brutality includes, but is not limited to, ...

, hippies

A hippie, also spelled hippy, especially in British English, is someone associated with the counterculture of the 1960s, originally a youth movement that began in the United States during the mid-1960s and spread to different countries around ...

and the lifestyle revolution, drugs, popular music, new society, cinema, theatre, graphics, cartoons, etc.

Local papers

Apart from publications such as ''IT'' and ''Oz'', both of which had a national circulation, the 1960s and 1970s saw the emergence of a whole range of local alternative newspapers, which were usually published monthly. These were largely made possible by the introduction in the 1950s of offset litho printing, which was much cheaper than traditional typesetting and use of the rotary letterpress. Such local papers included: * ''Aberdeen Peoples Press'' * ''Alarm'' (Swansea) * ''Andersonstown News'' (Belfast) * '' Brighton Voice'' * ''Bristol Voice'' * ''Feedback'' (Norwich) * ''Hackney People's Press'' * ''Islington Gutter Press'' * ''Leeds Other Paper'' * ''Response'' (Earl's Court, London) * ''Sheffield Free Press'' * ''West Highland Free Press'' A 1980 review identified some 70 such publications around the United Kingdom but estimated that the true number could well have run into hundreds. Such papers were usually published anonymously, for fear of the UK's draconian libel laws. They followed a broadanarchist

Anarchism is a political philosophy and movement that is skeptical of all justifications for authority and seeks to abolish the institutions it claims maintain unnecessary coercion and hierarchy, typically including, though not neces ...

, libertarian

Libertarianism (from french: libertaire, "libertarian"; from la, libertas, "freedom") is a political philosophy that upholds liberty as a core value. Libertarians seek to maximize autonomy and political freedom, and minimize the state's e ...

, left-wing of the Labour Party, socialist approach but the philosophy of a paper was usually flexible as those responsible for its production came and went. Most papers were run on collective

A collective is a group of entities that share or are motivated by at least one common issue or interest, or work together to achieve a common objective. Collectives can differ from cooperatives in that they are not necessarily focused upon an ...

principles.

List of UK underground papers

North America

Legal definition of "underground"

In the United States, the term ''underground'' did not mean ''illegal'' as it did in many other countries. TheFirst Amendment

First or 1st is the ordinal form of the number one (#1).

First or 1st may also refer to:

*World record, specifically the first instance of a particular achievement

Arts and media Music

* 1$T, American rapper, singer-songwriter, DJ, and rec ...

and various court decisions (e.g. ''Near v. Minnesota

''Near v. Minnesota'', 283 U.S. 697 (1931), was a List of landmark court decisions in the United States, landmark decision of the US Supreme Court under which prior restraint on publication was found to violate Freedom of the press in the United S ...

'') give very broad rights to anyone to publish a newspaper or other publication, and severely restrict government efforts to close down or censor a private publication. In fact, when censorship attempts are made by government agencies, they are either done in clandestine fashion (to keep it from being known the action is being taken by a government agency) or are usually ordered stopped by the courts when judicial action is taken in response to them.

A publication must, in general, be committing a crime (for example, reporters burglarizing someone's office to obtain information about a news item); violating the law in publishing a particular article or issue (printing obscene material, copyright infringement

Copyright infringement (at times referred to as piracy) is the use of works protected by copyright without permission for a usage where such permission is required, thereby infringing certain exclusive rights granted to the copyright holder, s ...

, libel

Defamation is the act of communicating to a third party false statements about a person, place or thing that results in damage to its reputation. It can be spoken (slander) or written (libel). It constitutes a tort or a crime. The legal defini ...

, breaking a non-disclosure agreement

A non-disclosure agreement (NDA) is a legal contract or part of a contract between at least two parties that outlines confidential material, knowledge, or information that the parties wish to share with one another for certain purposes, but wish ...

); directly threatening national security; or causing or potentially causing an imminent emergency (the " clear and present danger" standard) to be ordered stopped or otherwise suppressed, and then usually only the particular offending article or articles in question will be banned, while the newspaper itself is allowed to continue operating and can continue publishing other articles.

In the U.S. the term "underground newspaper" generally refers to an independent (and typically smaller) newspaper focusing on unpopular themes or counterculture issues. Typically, these tend to be politically to the left or far left. More narrowly, in the U.S. the term "underground newspaper" most often refers to publications of the period 1965–1973, when a sort of boom or craze for local tabloid underground newspapers swept the country in the wake of court decisions making prosecution for obscenity far more difficult. These publications became the voice of the rising New Left

The New Left was a broad political movement mainly in the 1960s and 1970s consisting of activists in the Western world who campaigned for a broad range of social issues such as civil and political rights, environmentalism, feminism, gay rights, g ...

and the hippie

A hippie, also spelled hippy, especially in British English, is someone associated with the counterculture of the 1960s, originally a youth movement that began in the United States during the mid-1960s and spread to different countries around ...

/psychedelic/rock and roll

Rock and roll (often written as rock & roll, rock 'n' roll, or rock 'n roll) is a Genre (music), genre of popular music that evolved in the United States during the late 1940s and early 1950s. It Origins of rock and roll, originated from Africa ...

counterculture

A counterculture is a culture whose values and norms of behavior differ substantially from those of mainstream society, sometimes diametrically opposed to mainstream cultural mores.Eric Donald Hirsch. ''The Dictionary of Cultural Literacy''. Hou ...

of the 1960s in America, and a focal point of opposition to the Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (also known by #Names, other names) was a conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. It was the second of the Indochina Wars and was officially fought between North Vie ...

and the draft.

Origins

The North American countercultural press of the 1960s drew inspiration from predecessors that had begun in the 1950s, such as the ''Village Voice

''The Village Voice'' is an American news and culture paper, known for being the country's first alternative newsweekly. Founded in 1955 by Dan Wolf, Ed Fancher, John Wilcock, and Norman Mailer, the ''Voice'' began as a platform for the creat ...

'' and Paul Krassner's satirical paper '' The Realist.'' Arguably, the first underground newspaper of the 1960s was the '' Los Angeles Free Press'', founded in 1964 and first published under that name in 1965.

1965–1973 boom period

According to Louis Menand, writing in ''The New Yorker

''The New Yorker'' is an American weekly magazine featuring journalism, commentary, criticism, essays, fiction, satire, cartoons, and poetry. Founded as a weekly in 1925, the magazine is published 47 times annually, with five of these issues ...

'', the underground press movement in the United States was "one of the most spontaneous and aggressive growths in publishing history." During the peak years of the phenomenon, there were generally about 100 papers currently publishing at any given time. But the underground press phenomenon proved short-lived.

An Underground Press Syndicate (UPS) roster published in November 1966 listed 14 underground papers, 11 of them in the United States, two in England, and one in Canada. Within a few years the number had mushroomed. A 1971 roster, published in Abbie Hoffman

Abbot Howard "Abbie" Hoffman (November 30, 1936 – April 12, 1989) was an American political and social activist who co-founded the Youth International Party ("Yippies") and was a member of the Chicago Seven. He was also a leading proponen ...

's ''Steal This Book

''Steal This Book'' is a book written by Abbie Hoffman. Written in 1970 and published in 1971, the book exemplified the counterculture of the sixties. The book sold more than a quarter of a million copies between April and November 1971. The numb ...

'', listed 271 UPS-affiliated papers; 11 were in Canada, 23 in Europe, and the remainder in the United States. The underground press' combined readership eventually reached into the millions.

The early papers varied greatly in visual style, content, and even in basic concept — and emerged from very different kinds of communities.Reed, John"The Underground Press and Its Extraordinary Moment in US History,"

''

Hyperallergic

''Hyperallergic'' is an online arts magazine, based in Brooklyn, New York. Founded by the art critic Hrag Vartanian and his husband Veken Gueyikian in October 2009, the site describes itself as a "forum for serious, playful, and radical thinking ...

'' (July 26, 2016). Many were decidedly rough-hewn, learning journalistic and production skills on the run. Some were militantly political while others featured highly spiritual content and were graphically sophisticated and adventuresome.

By 1969, virtually every sizable city or college town in North America boasted at least one underground newspaper. Among the most prominent of the underground papers were the ''San Francisco Oracle

''The Oracle of the City of San Francisco'', also known as the ''San Francisco Oracle,'' was an underground newspaper published in 12 issues from September 20, 1966, to February 1968 in the Haight-Ashbury neighborhood of that city. Allen Cohen (p ...

,'' '' San Francisco Express Times'', the '' Berkeley Barb'' and ''Berkeley Tribe

The ''Berkeley Tribe'' was a radical counterculture weekly underground newspaper published in Berkeley, California from 1969 to 1972. It was formed after a bitter staff dispute with publisher Max Scherr and split the nationally known ''Berkeley B ...

''; ''Open City

In war, an open city is a settlement which has announced it has abandoned all defensive efforts, generally in the event of the imminent capture of the city to avoid destruction. Once a city has declared itself open the opposing military will be ...

'' (Los Angeles

Los Angeles ( ; es, Los Ángeles, link=no , ), often referred to by its initials L.A., is the largest city in the state of California and the second most populous city in the United States after New York City, as well as one of the world' ...

), ''Fifth Estate

The Fifth Estate is a socio-cultural reference to groupings of outlier viewpoints in contemporary society, and is most associated with bloggers, journalists publishing in non-mainstream media outlets, and the social media or "social license". The ...

'' (Detroit

Detroit ( , ; , ) is the largest city in the U.S. state of Michigan. It is also the largest U.S. city on the United States–Canada border, and the seat of government of Wayne County. The City of Detroit had a population of 639,111 at th ...

), ''Other Scenes

John Wilcock (4 August 1927 – 13 September 2018) was a British journalist known for his work in the underground press, as well as his travel guide books.

The first news editor of the New York ''Village Voice'', Wilcock shook up staid publish ...

'' (dispatched from various locations around the world by John Wilcock

John Wilcock (4 August 1927 – 13 September 2018) was a British journalist known for his work in the underground press, as well as his travel guide books.

The first news editor of the New York ''Village Voice'', Wilcock shook up staid publish ...

); '' The Helix'' (Seattle

Seattle ( ) is a seaport city on the West Coast of the United States. It is the seat of King County, Washington. With a 2020 population of 737,015, it is the largest city in both the state of Washington and the Pacific Northwest regio ...

); ''Avatar

Avatar (, ; ), is a concept within Hinduism that in Sanskrit literally means "descent". It signifies the material appearance or incarnation of a powerful deity, goddess or spirit on Earth. The relative verb to "alight, to make one's appearanc ...

'' (Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

); ''The Chicago Seed

''The Chicago Seed'' was an underground newspaper published biweekly in Chicago, Illinois from May 1967 to 1974; there were 121 issues published in all. It was notable for its colorful psychedelic graphics and its eclectic, non-doctrinaire radic ...

''; '' The Great Speckled Bird'' (Atlanta

Atlanta ( ) is the capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Georgia. It is the seat of Fulton County, the most populous county in Georgia, but its territory falls in both Fulton and DeKalb counties. With a population of 498,715 ...

); ''The Rag

''The Rag'' was an underground newspaper published in Austin, Texas from 1966–1977. The weekly paper covered political and cultural topics that the conventional press ignored, such as the growing antiwar movement, the sexual revolution, gay l ...

'' (Austin, Texas

Austin is the capital city of the U.S. state of Texas, as well as the county seat, seat and largest city of Travis County, Texas, Travis County, with portions extending into Hays County, Texas, Hays and Williamson County, Texas, Williamson co ...

); ''Rat Subterranean News, Rat'' (New York City); ''Space City (newspaper), Space City!'' (Houston) and in Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by tot ...

, ''The Georgia Straight'' (Vancouver, BC).

''The Rag

''The Rag'' was an underground newspaper published in Austin, Texas from 1966–1977. The weekly paper covered political and cultural topics that the conventional press ignored, such as the growing antiwar movement, the sexual revolution, gay l ...

'', founded in Austin, Texas

Austin is the capital city of the U.S. state of Texas, as well as the county seat, seat and largest city of Travis County, Texas, Travis County, with portions extending into Hays County, Texas, Hays and Williamson County, Texas, Williamson co ...

, in 1966 by Thorne Dreyer and Carol Neiman, was especially influential. Historian Laurence Leamer called it "one of the few legendary undergrounds,"Leamer, Laurence, ''The Paper Revolutionaries: The Rise of the Underground Press'' (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1972) and, according to John McMillian, it served as a model for many papers that followed. ''The Rag'' was the sixth member of UPS and the first underground paper in the South and, according to historian Abe Peck, it was the "first undergrounder to represent the participatory democracy, community organizing and synthesis of politics and culture that the New Left of the mid-sixties was trying to develop." Leamer, in his 1972 book ''The Paper Revolutionaries'', called ''The Rag'' "one of the few legendary undergrounds". Gilbert Shelton's legendary ''Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers'' comic strip began in ''The Rag'', and thanks in part to UPS, was republished all over the world.

Probably the most graphically innovative of the underground papers was the ''San Francisco Oracle

''The Oracle of the City of San Francisco'', also known as the ''San Francisco Oracle,'' was an underground newspaper published in 12 issues from September 20, 1966, to February 1968 in the Haight-Ashbury neighborhood of that city. Allen Cohen (p ...

''. John Wilcock

John Wilcock (4 August 1927 – 13 September 2018) was a British journalist known for his work in the underground press, as well as his travel guide books.

The first news editor of the New York ''Village Voice'', Wilcock shook up staid publish ...

, a founder of the Underground Press Syndicate, wrote about the ''Oracle'': "Its creators are using color the way Lautrec must once have experimented with lithography – testing the resources of the medium to the utmost and producing what almost any experienced newspaperman would tell you was impossible... it is a creative dynamo whose influence will undoubtedly change the look of American publishing."

In the period 1969–1970, a number of underground papers grew more militant and began to openly discuss armed revolution against the state, some going so far as to print manuals for bombing and urging their readers to arm themselves; this trend, however, soon fell silent after the rise and fall of the Weather Underground and the tragic Kent State shootings, shootings at Kent State.

High school underground press

During this period there was also a widespread underground press movement circulating unauthorized student-published tabloids and mimeographed sheets at hundreds of high schools around the U.S. (In 1968, a survey of 400 high schools in Southern California found that 52% reported student underground press activity in their school.) Most of these papers put out only a few issues, running off a few hundred copies of each and circulating them only at one local school, although there was one system-wide antiwar high school underground paper produced in New York in 1969 with a 10,000-copy press run. Houston's ''Little Red Schoolhouse,'' a citywide underground paper published by high school students, was founded in 1970. For a time in 1968–1969, the high school underground press had its own print syndication, press services: FRED (run by C. Clark Kissinger of Students for a Democratic Society, with its base in Chicago schools) and HIPS (High School Independent Press Service, produced by students working out of Liberation News Service headquarters and aimed primarily but not exclusively at New York City schools). These services typically produced a weekly packet of articles and features mailed to subscribing papers around the country; HIPS reported 60 subscribing papers.G.I. underground press

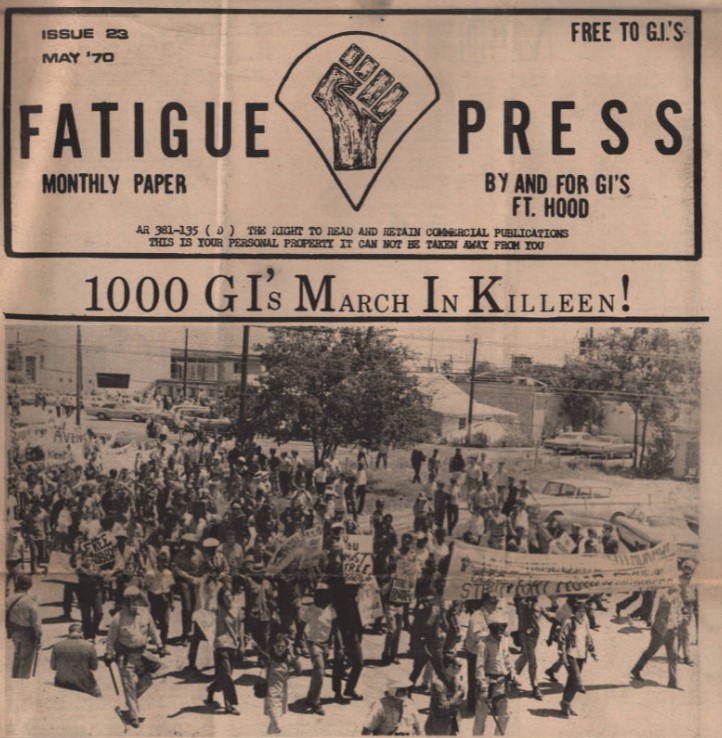

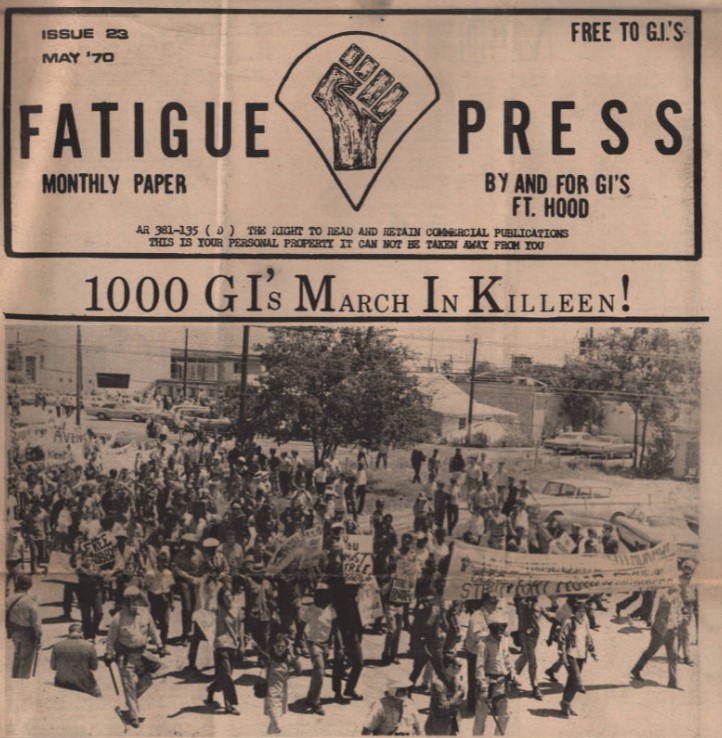

The G.I. underground press in America produced a few hundred titles during the Vietnam War, some produced by antiwar G.I. coffeehouses, and many of them small, crudely produced, low-circulation mimeographed "zines" written by a draftee editor opposed to the war and circulated locally off-base. Three or four G.I. underground papers had large-scale, national distribution of more than 20,000 copies, including thousands of copies mailed to G.I.'s overseas. These papers were produced with the support of civilian anti-war activists, and had to be disguised to be sent through the mail into Vietnam, where soldiers distributing or even possessing them might be subject to harassment, disciplinary action, or arrest. The idea of smuggling a full-size printing press into South Vietnam was determined to be too dangerous to attempt. As an alternative, a few G.I.'s based in South Vietnam were issued small kits to enable them to produce little hektograph-type zines.Technological and financial realities

The boom in the underground press was made practical by the availability of cheap offset printing, which made it possible to print a few thousand copies of a small tabloid paper for a couple of hundred dollars, which a sympathetic printer might extend on credit. Paper was cheap, and many printing firms around the country had over-expanded during the 1950s and had excess capacity on their offset web presses, which could be negotiated for at bargain rates. Most papers operated on a shoestring budget, pasting up camera-ready copy on layout sheets on the editor's kitchen table, with labor performed by unpaid, non-union volunteers. Typesetting costs, which at the time were wiping out many established big city papers, were avoided by typing up copy on a rented or borrowed IBM Selectric typewriter to be pasted-up by hand. As one observer commented with only slight hyperbole, students were financing the publication of these papers out of their lunch money.Syndicates and news services

In mid-1966, the cooperative Underground Press Syndicate (UPS) was formed at the instigation of Walter Bowart, the publisher of another early paper, the ''East Village Other''. The UPS allowed member papers to freely reprint content from any of the other member papers. During this period, there were also a number of left-wing political periodicals with concerns similar to those of the underground press. Some of these periodicals joined the Underground Press Syndicate to gain services such as microfilming, advertising, and the free exchange of articles and newspapers. Examples include ''The Black Panther (newspaper), The Black Panther'' (the paper of the Black Panther Party, Oakland, California), and ''National Guardian, The Guardian'' (New York City), both of which had national distribution. Almost from the outset, UPS supported and distributed underground comix strips to its member papers. Some of the cartoonists syndicated by UPS included Robert Crumb, Jay Lynch, The Mad Peck's ''Burn of the Week'', Ron Cobb, and Frank Stack."Special Collections and Rare Books: Frank Stack Collection,"University of Missouri Libraries. Accessed Dec. 29, 2016. The Rip Off Press Syndicate was launched 1973 to compete in selling underground comix content to the underground press and student publications.Fox, M. Steven

"Rip Off Comix — 1977-1991 / Rip Off Press,"

Comixjoint. Retrieved Dec. 5, 2022. Each Friday, the company sent out a distribution sheet with the strips it was selling, by such cartoonists as Gilbert Shelton, Bill Griffith, Joel Beck, Dave Sheridan (cartoonist), Dave Sheridan, Ted Richards (artist), Ted Richards, and Harry Driggs. The Liberation News Service (LNS), co-founded in the summer of 1967 by Ray Mungo and Marshall Bloom, "provided coverage of events to which most papers would have otherwise had no access." In a similar vein, John Berger (author), John Berger, Lee Marrs, and others co-founded Alternative Features Service, Inc. in 1970 to supply the underground and college press, as well as independent radio stations, with syndicated press materials that especially highlighted the creation of alternative institutions, such as free clinics, community bank, people's banks, free universities, and alternative housing. By 1973, many underground papers had folded, at which point the Underground Press Syndicate acknowledged the passing of the undergrounds and renamed itself the Alternative Press Syndicate (APS). After a few years, APS also foundered, to be supplanted in 1978 by the Association of Alternative Newsweeklies.

Controversies

One of the most notorious underground newspapers to join UPS and rally activists, poets, and artists by giving them an uncensored voice, was the ''NOLA Express'' in New Orleans. Started by Robert Head and Darlene Fife as part of political protests and extending the "mimeo revolution" by protest and freedom-of-speech poets during the 1960s, ''NOLA Express'' was also a member of the Committee of Small Magazine Editors and Publishers (COSMEP). These two affiliations with organizations that were often at cross-purposes made ''NOLA Express'' one of the most radical and controversial publications of the counterculture movement. Part of the controversy about ''NOLA Express'' included graphic photographs and illustrations of which many even in today's society would be banned as pornographic. Charles Bukowski's syndicated column, ''Notes of a Dirty Old Man,'' ran in ''NOLA Express'', and Francisco McBride's illustration for the story "The Fuck Machine" was considered sexist, pornographic, and created an uproar. All of this controversy helped to increase the readership and bring attention to the political causes that editors Fife and Head supported.Harassment and intimidation

Many of the papers faced official harassment on a regular basis; local police repeatedly raided and busted up the offices of ''Dallas Notes'' and jailed editor Stoney Burns on drug charges; charged Atlanta's ''The Great Speckled Bird (newspaper), Great Speckled Bird'' and others with obscenity; arrested street vendors; and pressured local printers not to print underground papers. In Austin, the regents at the University of Texas sued ''The Rag'' to prevent circulation on campus but the American Civil Liberties Union successfully defended the paper's First Amendment rights before the U.S. Supreme Court. In an apparent attempt to shut down ''The Spectator'' in Bloomington, Indiana, editor James Retherford was briefly imprisoned for alleged violations of the Selective Service laws; his conviction was overturned and the prosecutors were rebuked by a federal judge. Drive-by shootings, firebombings, break-ins, and trashings were carried out on the offices of many underground papers around the country, fortunately without causing any fatalities. The offices of Houston's ''Space City (newspaper), Space City!'' were bombed and its windows repeatedly shot out. In Houston, as in many other cities, the attackers, never identified, were suspected of being off-duty military or police personnel, or members of the Ku Klux Klan or Minutemen (anti-Communist organization), Minuteman organizations.

Some of the most violent attacks were carried out against the underground press in San Diego. In 1976 the ''San Diego Union-Tribune, San Diego Union'' reported that the attacks in 1971 and 1972 had been carried out by a right-wing paramilitary group calling itself the Secret Army Organization, which had ties to the local office of the FBI.

The U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) conducted surveillance and disruption activities on the underground press in the United States, including a campaign to destroy the News agency (alternative), alternative agency Liberation News Service. As part of its COINTELPRO designed to discredit and infiltrate radical New Left groups, the FBI also launched phony underground newspapers such as the ''Armageddon News'' at Indiana University Bloomington, ''The Longhorn Tale'' at the University of Texas at Austin, and the ''Rational Observer'' at American University in Washington, D.C. The FBI also ran the Pacific International News Service in San Francisco, the Chicago Midwest News, and the New York Press Service. Many of these organizations consisted of little more than a post office box and a letterhead, designed to enable the FBI to receive exchange copies of underground press publications and send undercover observers to underground press gatherings.

Drive-by shootings, firebombings, break-ins, and trashings were carried out on the offices of many underground papers around the country, fortunately without causing any fatalities. The offices of Houston's ''Space City (newspaper), Space City!'' were bombed and its windows repeatedly shot out. In Houston, as in many other cities, the attackers, never identified, were suspected of being off-duty military or police personnel, or members of the Ku Klux Klan or Minutemen (anti-Communist organization), Minuteman organizations.

Some of the most violent attacks were carried out against the underground press in San Diego. In 1976 the ''San Diego Union-Tribune, San Diego Union'' reported that the attacks in 1971 and 1972 had been carried out by a right-wing paramilitary group calling itself the Secret Army Organization, which had ties to the local office of the FBI.

The U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) conducted surveillance and disruption activities on the underground press in the United States, including a campaign to destroy the News agency (alternative), alternative agency Liberation News Service. As part of its COINTELPRO designed to discredit and infiltrate radical New Left groups, the FBI also launched phony underground newspapers such as the ''Armageddon News'' at Indiana University Bloomington, ''The Longhorn Tale'' at the University of Texas at Austin, and the ''Rational Observer'' at American University in Washington, D.C. The FBI also ran the Pacific International News Service in San Francisco, the Chicago Midwest News, and the New York Press Service. Many of these organizations consisted of little more than a post office box and a letterhead, designed to enable the FBI to receive exchange copies of underground press publications and send undercover observers to underground press gatherings.

Decline of the underground press

By the end of 1972, with the end of the draft and the winding down of the Vietnam War, there was increasingly little reason for the underground press to exist. A number of papers passed out of existence during this time; among the survivors a newer and less polemical view toward middle-class values and working within the system emerged. The underground press began to evolve into the socially conscious, lifestyle-oriented alternative media that currently dominates this form of weekly print media in North America. In 1973, the landmark Supreme Court of the United States, Supreme Court decision in ''Miller v. California'' re-enabled local obscenity prosecutions after a long hiatus. This sounded the death knell for much of the remaining underground press (including underground comix), largely by making the localhead shop

A head shop is a retail outlet specializing in paraphernalia used for consumption of cannabis and tobacco and items related to cannabis culture and related countercultures. They emerged from the hippie counterculture in the late 1960s, and ...

s which stocked underground papers and comix in communities around the country more vulnerable to prosecution.

''The Georgia Straight'' outlived the underground movement, evolving into an alternative weekly still published today; ''Fifth Estate'' survives as an anarchism, anarchist magazine. ''The Rag

''The Rag'' was an underground newspaper published in Austin, Texas from 1966–1977. The weekly paper covered political and cultural topics that the conventional press ignored, such as the growing antiwar movement, the sexual revolution, gay l ...

'' – which was published for 11 years in Austin (1966–1977) – was revived in 2006 as an online publication, ''The Rag Blog'', which now has a wide following in the progressive blogosphere and whose contributors include many veterans of the original underground press.

Given the nature of alternative journalism as a subculture, some staff members from underground newspapers became staff on the newer alternative weeklies, even though there was seldom institutional continuity with management or ownership. An example is the transition in Denver from the underground ''Chinook (newspaper), Chinook'', to ''Chinook (newspaper), Straight Creek Journal'', to ''Westword'', an alternative weekly still in publication. Some underground and alternative reporters, cartoonists, and artists moved on to work in corporate media or in academia.

Lists of underground press papers

United States

More than a thousand underground newspapers were published in the United States during the Vietnam War. The following is a short list of the more widely circulated, longer-lived and notable titles. For a longer, more comprehensive listing sorted by states, see the list of underground newspapers, long list of underground newspapers.U.S. military G.I. papers

See Table: GI Underground Press (United States Military)#Table: GI Underground Press During the Vietnam War (U.S. Military), GI Underground Press During the Vietnam War (U.S. Military)

See Table: GI Underground Press (United States Military)#Table: GI Underground Press During the Vietnam War (U.S. Military), GI Underground Press During the Vietnam War (U.S. Military)

Canada

* ''Canada Goose (newspaper), Canada Goose'', Edmonton, Alberta * ''The Georgia Straight'', Vancouver, British Columbia * ''Guerilla'', Toronto, Ontario * ''Harbinger (Toronto newspaper), Harbinger'', Toronto, Ontario * ''Logos (Montréal newspaper), Logos'', Montreal, Quebec * ''Loving Couch Press'', Winnipeg, Manitoba * ''Mainmise'' (1970–1978), Montreal, Quebec * ''Octopus (newspaper), Octopus'', Ottawa, Ontario (a.k.a. ''Canadian Free Press'', ''Ottawa's Free Press'') * ''Pop-See-Cul'', Montreal, Quebec * ''Sexus'' (1967–1968), and ''Allez chier'' (1969), Montreal, Quebec * ''Yorkville Yawn'' and ''Satyrday'', Yorkville (Toronto), Yorkville, Toronto, OntarioIndia

* ''Hungry Generation weekly bulletins''. Calcutta (1961–1965) The Hungry Generation was a literary movement in the Bengali language launched by what is known today as the ''Hungryalist quartet'', ''i.e.'' Shakti Chattopadhyay, Malay Roy Choudhury, Samir Roychoudhury and Debi Roy (''alias'' Haradhon Dhara), during the 1960s in Kolkata, India. Due to their involvement in this avant garde cultural movement, the leaders lost their jobs and were jailed by the incumbent government. They challenged contemporary ideas about literature and contributed significantly to the evolution of the language and idiom used by contemporaneous artists to express their feelings in literature and painting.Dr Uttam Das, Reader, Calcutta University, in his dissertation 'Hungry Shruti and Shastravirodhi Andolan' This movement is characterized by expression of closeness to nature and sometimes by tenets of Gandhianism and Proudhonianism. Although it originated at Patna, Bihar and was initially based in Kolkata, it had participants spread over North Bengal, Tripura and Benares. According to Dr. Shankar Bhattacharya, Dean (education), Dean at Assam University, as well as Aryanil Mukherjee, editor of Kaurab Literary Periodical, the movement influenced Allen Ginsberg as much as it influenced American poetry through the Beat poets who visited Calcutta, Patna and Benares during the 1960–1970s. Arvind Krishna Mehrotra, now a professor and editor, was associated with the Hungry generation movement. Shakti Chattopadhyay, Saileswar Ghosh, Subhas Ghosh left the movement in 1964. More than 100 manifestos were issued during 1961–1965. Malay's Poetry, poems have been published by Prof P. Lal from his Writers Workshop publication. Howard McCord published Malay Roy Choudhury's controversial poem ''Prachanda Boidyutik Chhutar'' i.e., "Stark Electric Jesus from Washington State University" in 1965. The poem has been translated into several languages of the world; into German language, German by Carl Weissner, into Spanish language, Spanish by Margaret Randall, into Urdu language, Urdu by Ameeq Hanfee, into Assamese language, Assamese by Manik Dass, into Gujarati language, Gujarati by Nalin Patel, into Hindi language, Hindi by Rajkamal Chaudhary, and into English language, English by Howard McCord.In Italy

* (Turin) * (Milan) * (Turin)In the Netherlands

Clandestine press in the Netherlands is related to the second World War, which ran from 10 May 1940 until 5 May 1945 in the Netherlands.

* See the :w:nl:Lijst van verzetsbladen uit de Tweede Wereldoorlog, list of 1300 Dutch illegal WW2 newspapers on Dutch Wikipedia

* See also on Dutch Wikipedia

:* :w:nl:Lijst van uitgaveplaatsen van verzetsbladen tijdens de Tweede Wereldoorlog, List of places of publication of Dutch illegal WW2 newspapers

:* :w:nl:Lijst van drukkerijen en uitgeverijen van verzetsbladen gedurende de Tweede Wereldoorlog, List of printers and publishers of Dutch illegal WW2 newspapers

:* :w:nl:Lijst van legaal voortgezette verzetsbladen na de Tweede Wereldoorlog, List of legally continued Dutch WW2 newspapers

Clandestine press in the Netherlands is related to the second World War, which ran from 10 May 1940 until 5 May 1945 in the Netherlands.

* See the :w:nl:Lijst van verzetsbladen uit de Tweede Wereldoorlog, list of 1300 Dutch illegal WW2 newspapers on Dutch Wikipedia

* See also on Dutch Wikipedia

:* :w:nl:Lijst van uitgaveplaatsen van verzetsbladen tijdens de Tweede Wereldoorlog, List of places of publication of Dutch illegal WW2 newspapers

:* :w:nl:Lijst van drukkerijen en uitgeverijen van verzetsbladen gedurende de Tweede Wereldoorlog, List of printers and publishers of Dutch illegal WW2 newspapers

:* :w:nl:Lijst van legaal voortgezette verzetsbladen na de Tweede Wereldoorlog, List of legally continued Dutch WW2 newspapers

See also

* Alternative media ** Alternative media (U.S. political left) ** Alternative media (U.S. political right) * Clandestine literature * List of underground newspapers (by country and state) * List of underground newspapers of the 1960s counterculture * News agency (alternative) * , Italian alternative editor) * Jeff Sharlet (Vietnam antiwar activist) * , Italian underground activist) * , (co-editor, Italian ''Re Nudo'')Further reading

* Leamer, Lawrence. ''The Paper Revolutionaries''. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster, 1972. * Lewes, James. ''Protest and Survive: Underground GI Newspapers during the Vietnam War''. Westport: Praeger Publishers, 2003. . * Mackenzie, Angus, "Sabotaging the Dissident Press", ''Columbia Journalism Review'', March–April 1981, pp. 57–63, Center for Investigative Reporting, 1983. * Mungo, Raymond. ''Famous Long Ago: My Life and Hard Times With the Liberation News Service''. Boston: Beacon Press, 1970. * Peck, Abe. ''Uncovering the Sixties''. New York, NY: Pantheon Books, 1985. * Rips, Geoffrey, ''The Campaign Against the Underground Press'', San Francisco, City Lights Books, 1981. * Verzuh, Ron, "Underground Times: Canada's Flower-Child Revolutionaries", Toronto: Deneau, 1989. * Wachsberger, Ken, editor. ''Voices From the Underground''. Tempe, AZ: Mica Press, 1993.Notes

References

Citations

Sources

"The Underground GI Press: Pens Against the Pentagon,"

''Commonweal''. Reprinted in ''Duck Power'' vol. 1, no. 4.

''Voices from the Underground (Vol. 1): Insider Histories of the Vietnam Era Underground Press''

* Holhut, Randolph T. [http://www.brasscheck.com/seldes/history.html "A Brief History of American Alternative Journalism in the Twentieth Century,"] BrassCheck.com. Retrieved Dec. 15, 2022. * Thorne Webb Dreyer, Dreyer, Thorne and Victoria Smith

"The Movement and the New Media,"

Liberation News Service (1969).

External links

* ; U.S. underground pressUnderground/Alternative Newspapers History and Geography

Maps and databases showing over 2,000 underground/alternative newspapers between 1965 and 1975 in the U.S. From the Mapping American Social Movements project at the University of Washington. * A number of libraries have extensive microfilm collections of underground newspapers. For example, th

University of Oregon

library has a collection that consists of mostly, but not exclusively North American underground papers.

Chicano Newspapers and Periodicals 1966-1979

Maps and charts showing over 300 Chicano newspapers from the 1960s and 70s

"Voices from the Underground," an exhibition of the North American underground press of the 1960s; includes a substantial gallery of color images

A digitally scanned archive of the first twelve issues (1966-67) of ''The Rag'', from Austin, Texas

Articles about the underground press at ''The Rag Blog''

(While ''The Avatar'' shared its design approach and many social concerns with other underground papers of the time, in one important respect it was completely atypical: it served as a platform for self-proclaimed "world saviour" Mel Lyman, leader of the Fort Hill Community.)

A collection of ''Space City News'' covers

by underground artist Bill Narum

The website for the film ''Sir! No Sir!''

has an extensive collection of primary source materials from the GI underground press

''The Truth''

, a specimen high school underground paper from 1969 ; U.K. underground press

by Gerry Carlin and Mark Jones

''International Times'' archive

''OZ magazine'', London, 1967-1973

online at the University of Wollongong Library ; Australian underground press

''The Digger'', 1972-1975

online at the University of Wollongong Library

''Nexus'' magazine (Australia)

''OZ magazine'', Sydney, 1963-1969

online at the University of Wollongong Library

Ozit.org

— history of ''OZ Magazine'' (archived site) ; European underground press

at stampamusicale.altervista.org

Interviews

Underground press historian Sean Stewart on Rag Radio

Interviewed by Thorne Dreyer, August 31, 2010 (57:17)

Historian John McMillian, author of ''Smoking Typewriters: The Sixties Underground Press and the Rise of Alternative Media in America'' on Rag Radio

Interviewed by Thorne Dreyer, March 4, 2011 (42:18)

Thorne Dreyer's 24 hour-long Rag Radio interviews with veterans of the Sixties underground press

{{DEFAULTSORT:Underground press Underground press, Alternative press Alternative media