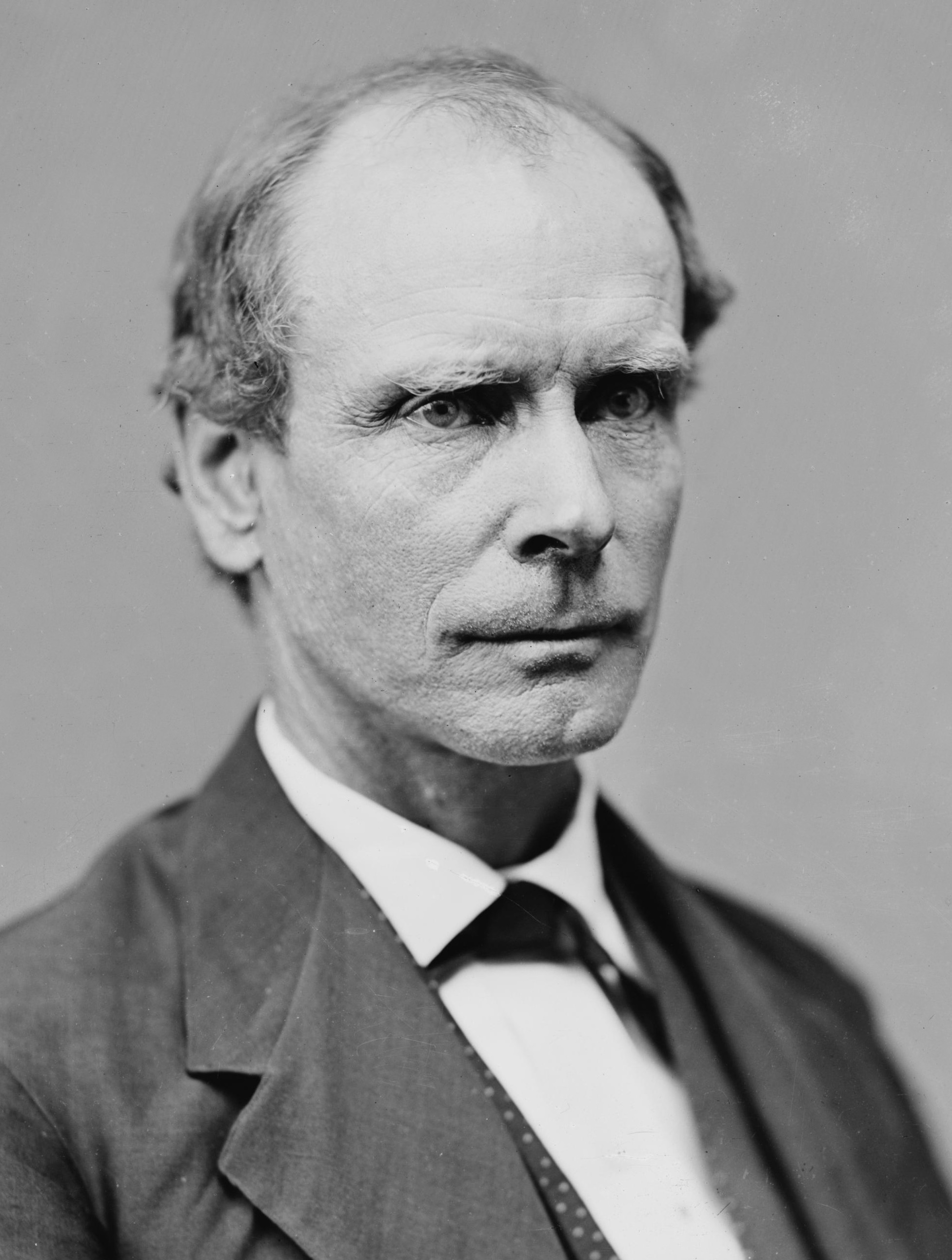

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th

president of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United Stat ...

from 1869 to 1877. As

commanding general, Grant led the

Union Army

During the American Civil War, the Union Army, also known as the Federal Army and the Northern Army, referring to the United States Army, was the land force that fought to preserve the Union (American Civil War), Union of the collective U.S. st ...

to victory in the

American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

in 1865 and briefly served as

U.S. secretary of war

The secretary of war was a member of the U.S. president's Cabinet, beginning with George Washington's administration. A similar position, called either "Secretary at War" or "Secretary of War", had been appointed to serve the Congress of the ...

. An effective civil rights executive, Grant signed a bill to create the

United States Department of Justice

The United States Department of Justice (DOJ), also known as the Justice Department, is a federal executive department of the United States government tasked with the enforcement of federal law and administration of justice in the United State ...

and worked with

Radical Republicans to protect African Americans during

Reconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

*Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*''Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Union ...

.

Grant was born in Ohio and graduated from

West Point in 1843. He served with distinction in the

Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War, also known in the United States as the Mexican War and in Mexico as the (''United States intervention in Mexico''), was an armed conflict between the United States and Mexico from 1846 to 1848. It followed the 1 ...

, but resigned from the army in 1854 and returned to civilian life impoverished. In 1861, shortly after the Civil War began, Grant joined the Union Army and rose to prominence after securing Union victories in

the western theater. In 1863, he led the

Vicksburg campaign

The Vicksburg campaign was a series of maneuvers and battles in the Western Theater of the American Civil War directed against Vicksburg, Mississippi, a fortress city that dominated the last Confederate-controlled section of the Mississippi Riv ...

that gave Union forces control of the

Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson Bay drainage system. From its traditional source of Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota, it f ...

and dealt a major strategic blow to the Confederacy. President

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

promoted Grant to

lieutenant general

Lieutenant general (Lt Gen, LTG and similar) is a three-star military rank (NATO code OF-8) used in many countries. The rank traces its origins to the Middle Ages, where the title of lieutenant general was held by the second-in-command on the ...

and command of all Union armies after

his victory at Chattanooga. For thirteen months, Grant fought

Robert E. Lee

Robert Edward Lee (January 19, 1807 – October 12, 1870) was a Confederate general during the American Civil War, towards the end of which he was appointed the overall commander of the Confederate States Army. He led the Army of Nort ...

during the high-casualty

Overland Campaign which ended with the capture of Lee's army

at Appomattox, where he formally surrendered to Grant. In 1866, President

Andrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson (December 29, 1808July 31, 1875) was the 17th president of the United States, serving from 1865 to 1869. He assumed the presidency as he was vice president at the time of the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. Johnson was a Dem ...

promoted Grant to

General of the Army. Later, Grant broke with Johnson over Reconstruction policies. A war hero, drawn in by his sense of duty, Grant was unanimously nominated by the Republican Party and then

elected president in 1868.

As president, Grant stabilized the post-war national economy, supported congressional Reconstruction and

the Fifteenth Amendment, and prosecuted the

Ku Klux Klan

The Ku Klux Klan (), commonly shortened to the KKK or the Klan, is an American white supremacist, right-wing terrorist, and hate group whose primary targets are African Americans, Jews, Latinos, Asian Americans, Native Americans, and ...

. Under Grant, the Union was completely restored. He appointed African Americans and Jewish Americans to prominent federal offices. In 1871, he created the

first Civil Service Commission, advancing the civil service more than any prior president. Grant was re-elected in

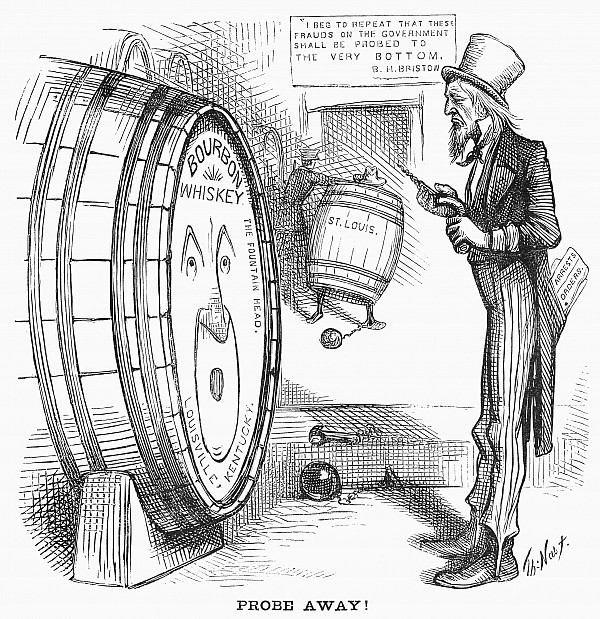

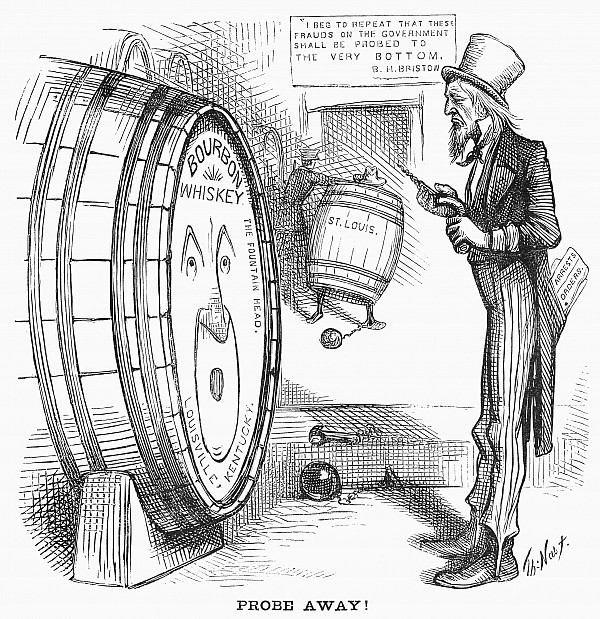

the 1872 presidential election, but was inundated by executive scandals during his second term. His response to the

Panic of 1873 was ineffective in halting the

Long Depression, which contributed to the Democrats

winning the House majority in 1874. Grant's Native American policy was to assimilate Indians into Anglo-American culture. In Grant's foreign policy, the

''Alabama'' Claims against Britain were peacefully resolved, but the Senate rejected Grant's

annexation of Santo Domingo. In the

disputed 1876 presidential election, Grant facilitated the approval by Congress of a peaceful compromise.

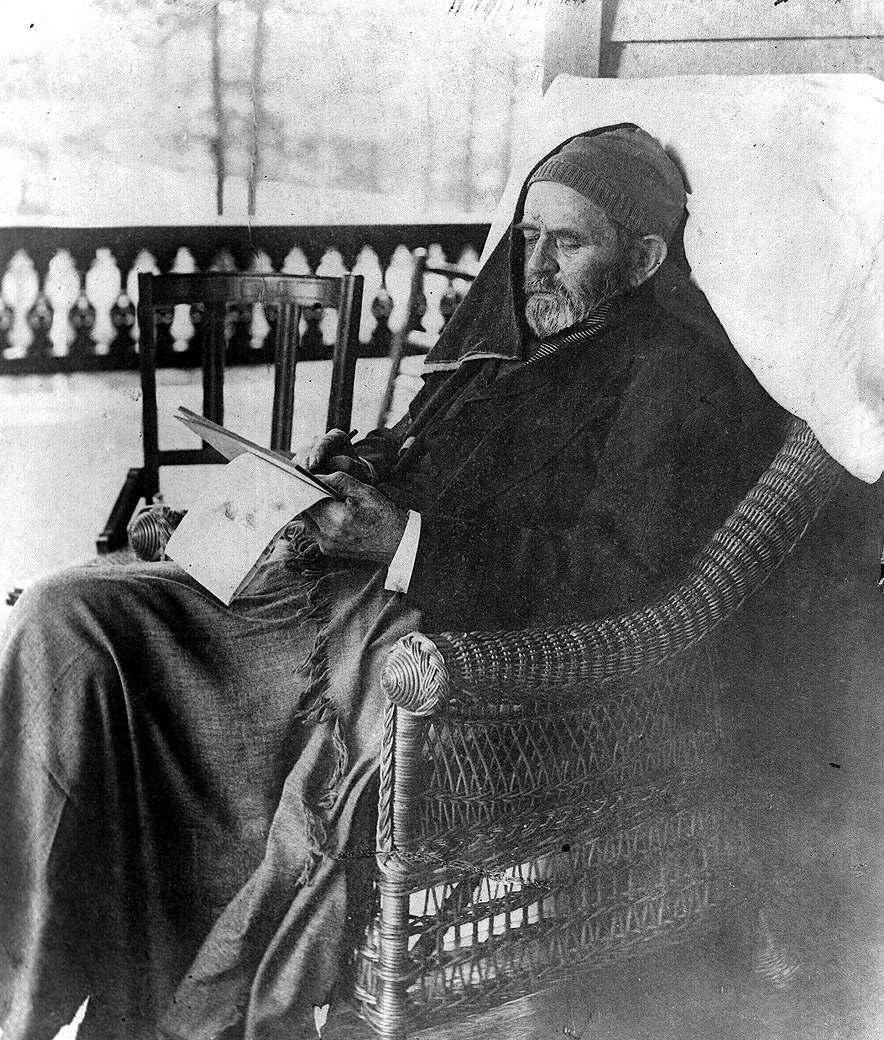

Leaving office in 1877, Grant undertook

a world tour, meeting prominent figures and becoming the first president to circumnavigate the world. In 1880, he

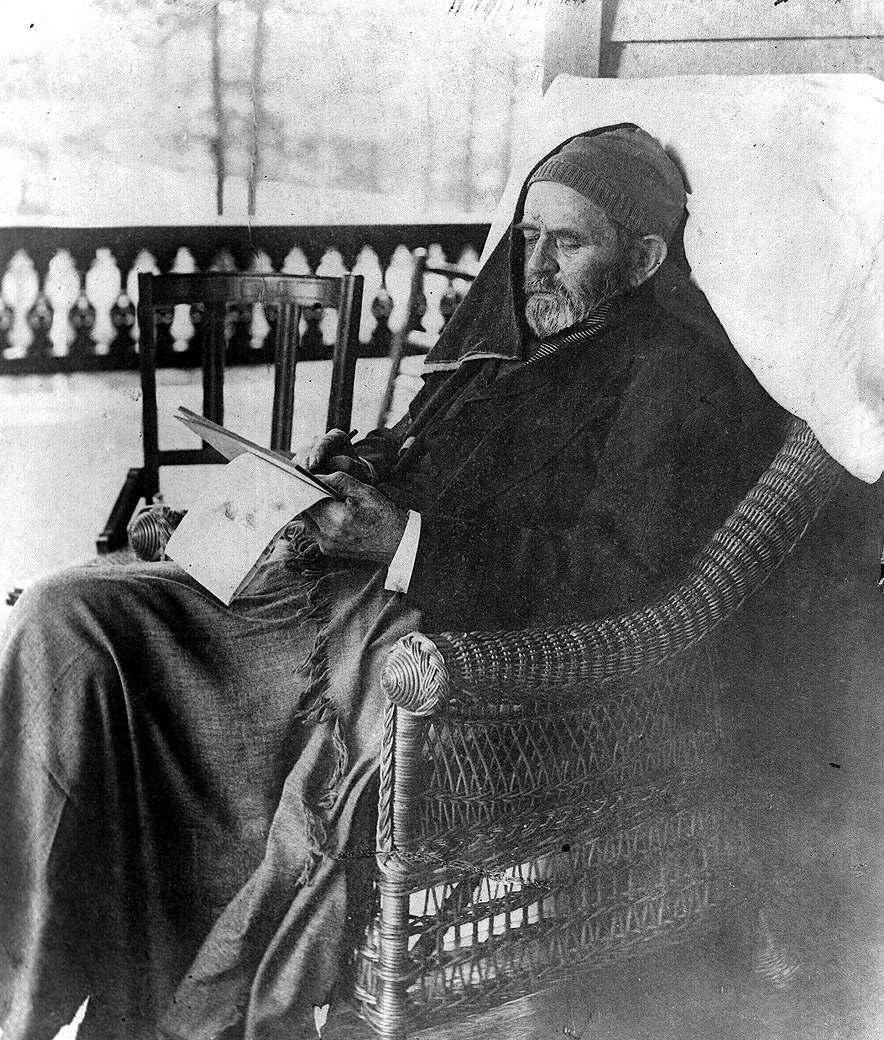

was unsuccessful in obtaining the Republican nomination for a third term. In 1885, facing severe financial reversals and dying of throat cancer, Grant wrote

his memoirs, covering his life through the Civil War, which were posthumously published and became a major critical and financial success. At his death, Grant was the most popular American and was memorialized as a symbol of national unity. Due to the

pseudohistorical and

negationist

Historical negationism, also called denialism, is falsification or distortion of the historical record. It should not be conflated with ''historical revisionism'', a broader term that extends to newly evidenced, fairly reasoned academic reinterp ...

mythology of the

Lost Cause of the Confederacy

The Lost Cause of the Confederacy (or simply Lost Cause) is an History of the United States, American pseudohistorical historical negationist, negationist mythology that claims the cause of the Confederate States during the American Civil Wa ...

spread by Confederate sympathizers around the turn of the 20th century,

historical assessments and

rankings

A ranking is a relationship between a set of items such that, for any two items, the first is either "ranked higher than", "ranked lower than" or "ranked equal to" the second.

In mathematics, this is known as a weak order or total preorder of o ...

of Grant's presidency suffered considerably before they began recovering in the 21st century. Grant's critics take a negative view of his economic mismanagement and the corruption within his administration, while his admirers emphasize his

policy towards Native Americans,

vigorous enforcement of civil and voting rights for African Americans, and securing North and South as a single nation within the Union. Modern scholarship has better appreciated Grant's appointments of Cabinet reformers.

Early life and education

Grant's father

Jesse Root Grant

Jesse Root Grant (January 23, 1794 – June 29, 1873) was an American farmer, tanner and successful leather merchant who owned tanneries and leather goods shops in several different states throughout his adult life. He is best known as the ...

was a

Whig Party supporter and a fervent abolitionist.

Jesse and

Hannah Simpson were married on June 24, 1821, and their first child, Hiram Ulysses Grant, was born on April 27, 1822. The name Ulysses was drawn from ballots placed in a hat. To honor his father-in-law, Jesse named the boy "Hiram Ulysses", though he would always refer to him as "Ulysses". In 1823, the family moved to

Georgetown, Ohio

Georgetown is a village (United States)#Ohio, village in Brown County, Ohio, Brown County, Ohio, United States located about 36 miles southeast of Cincinnati. The population was 4,331 at the 2010 United States Census, 2010 census. It is the count ...

, where five siblings were born: Simpson, Clara, Orvil, Jennie, and Mary. At the age of five, Ulysses started at a

subscription school and later attended two private schools. In the winter of 1836–1837, Grant was a student at

Maysville Seminary, and in the autumn of 1838, he attended

John Rankin's academy.

In his youth, Grant developed an unusual ability to ride and manage horses. His father put his ability to use by giving him work driving wagon loads of supplies and transporting people. Unlike his siblings, Grant was not forced to attend church by his

Methodist

Methodism, also called the Methodist movement, is a group of historically related denominations of Protestant Christianity whose origins, doctrine and practice derive from the life and teachings of John Wesley. George Whitefield and John's b ...

parents. For the rest of his life, he prayed privately and never officially joined any denomination. To others, including his own son, Grant appeared to be

agnostic

Agnosticism is the view or belief that the existence of God, of the divine or the supernatural is unknown or unknowable. (page 56 in 1967 edition) Another definition provided is the view that "human reason is incapable of providing sufficient ...

. Grant was largely apolitical before the war but wrote, "If I had ever had any political sympathies they would have been with the Whigs. I was raised in that school."

Early military career and personal life

West Point and first assignment

Jesse Grant wrote to Representative

Thomas L. Hamer

Thomas Lyon Hamer (July 1800December 2, 1846) was a United States Democratic congressman and soldier.

Hamer was born in July 1800 in Northumberland County, Pennsylvania. He was a school teacher before being admitted to the bar in 1821. He was a ...

requesting that he nominate Ulysses to the

United States Military Academy

The United States Military Academy (USMA), also known metonymically as West Point or simply as Army, is a United States service academy in West Point, New York. It was originally established as a fort, since it sits on strategic high groun ...

at

West Point, New York

West Point is the oldest continuously occupied military post in the United States. Located on the Hudson River in New York, West Point was identified by General George Washington as the most important strategic position in America during the Ame ...

, which Hamer did in spring 1839. Grant was accepted on July 1. Unfamiliar with Grant, Hamer altered his name, so Grant was enlisted under the name "U. S. Grant". Since the initials "U.S." also stood for "

Uncle Sam", he became known among army colleagues as "Sam."

Initially, Grant was indifferent to military life, but within a year he reexamined his desire to leave the academy and later wrote that "on the whole I like this place very much". He earned a reputation as the

"most proficient" horseman. Seeking relief from military routine, he studied under

Romantic

Romantic may refer to:

Genres and eras

* The Romantic era, an artistic, literary, musical and intellectual movement of the 18th and 19th centuries

** Romantic music, of that era

** Romantic poetry, of that era

** Romanticism in science, of that e ...

artist

Robert Walter Weir

Robert Walter Weir (June 18, 1803 – May 1, 1889) was an American artist and educator and is considered a painter of the Hudson River School. Weir was elected to the National Academy of Design in 1829 and was an instructor at the United States M ...

, producing nine surviving artworks. He spent more time reading books from the library than his academic texts. On Sundays, cadets were required to march to and attend services at the academy's church, which Grant disliked. Quiet by nature, he established a few intimate friends among fellow cadets, including

Frederick Tracy Dent and

James Longstreet

James Longstreet (January 8, 1821January 2, 1904) was one of the foremost Confederate generals of the American Civil War and the principal subordinate to General Robert E. Lee, who called him his "Old War Horse". He served under Lee as a corps ...

. He was inspired both by the Commandant, Captain

Charles Ferguson Smith, and by General

Winfield Scott

Winfield Scott (June 13, 1786May 29, 1866) was an American military commander and political candidate. He served as a general in the United States Army from 1814 to 1861, taking part in the War of 1812, the Mexican–American War, the early s ...

, who visited the academy to review the cadets. Grant later wrote of the military life, "there is much to dislike, but more to like."

Grant graduated on June 30, 1843, ranked 21st out of 39 in his class and was promoted the next day to

brevet

Brevet may refer to:

Military

* Brevet (military), higher rank that rewards merit or gallantry, but without higher pay

* Brevet d'état-major, a military distinction in France and Belgium awarded to officers passing military staff college

* Aircre ...

second lieutenant

Second lieutenant is a junior commissioned officer military rank in many armed forces, comparable to NATO OF-1 rank.

Australia

The rank of second lieutenant existed in the military forces of the Australian colonies and Australian Army until ...

. He planned to resign his commission after his four-year term. He would later write that among the happiest days of his life were the day he left the presidency and the day he left the academy. Despite his excellent horsemanship, he was not assigned to the cavalry, but to the

4th Infantry Regiment. Grant's first assignment was the

Jefferson Barracks near

St. Louis, Missouri

St. Louis () is the second-largest city in Missouri, United States. It sits near the confluence of the Mississippi River, Mississippi and the Missouri Rivers. In 2020, the city proper had a population of 301,578, while the Greater St. Louis, ...

. Commanded by Colonel

Stephen W. Kearny

Stephen Watts Kearny (sometimes spelled Kearney) ( ) (August 30, 1794October 31, 1848) was one of the foremost History of the United States (1789–1849), antebellum frontier officers of the United States Army. He is remembered for his significan ...

, this was the nation's largest military base in the West. Grant was happy with his new commander but looked forward to the end of his military service and a possible teaching career.

Marriage and family

In 1844, Grant accompanied Frederick Dent to Missouri and met his family, including Dent's sister

Julia. The two soon became engaged. On August 22, 1848, they were married at Julia's home in St. Louis. Grant's abolitionist father disapproved of the Dents' owning slaves, and neither of Grant's parents attended the wedding. At the wedding, Grant was flanked by three fellow West Point graduates dressed in their blue uniforms, including Longstreet, Julia's cousin.

The couple had four children:

Frederick,

Ulysses Jr. ("Buck"),

Ellen

Ellen is a female given name, a diminutive of Elizabeth, Eleanor, Elena and Helen. Ellen was the 609th most popular name in the U.S. and the 17th in Sweden in 2004.

People named Ellen include:

* Ellen Adarna (born 1988), Filipino actress

* Elle ...

("Nellie"), and

Jesse II. After the wedding, Grant obtained a two-month extension to his leave and returned to St. Louis, where he decided that, with a wife to support, he would remain in the army.

Mexican–American War

Grant's unit was stationed in Louisiana as part of the

Army of Occupation under Major General

Zachary Taylor

Zachary Taylor (November 24, 1784 – July 9, 1850) was an American military leader who served as the 12th president of the United States from 1849 until his death in 1850. Taylor was a career officer in the United States Army, rising to th ...

. In September 1846, President

James K. Polk

James Knox Polk (November 2, 1795 – June 15, 1849) was the 11th president of the United States, serving from 1845 to 1849. He previously was the 13th speaker of the House of Representatives (1835–1839) and ninth governor of Tennessee (183 ...

ordered Taylor to march 150 miles south to the

Rio Grande

The Rio Grande ( and ), known in Mexico as the Río Bravo del Norte or simply the Río Bravo, is one of the principal rivers (along with the Colorado River) in the southwestern United States and in northern Mexico.

The length of the Rio G ...

. Marching to

Fort Texas

Fort Brown (originally Fort Texas) was a military post of the United States Army in Cameron County, Texas, during the latter half of the 19th century and the early part of the 20th century. Established in 1846, it was the first US Army military ...

, to prevent a Mexican siege, Grant experienced combat for the first time on May 8, 1846, at the

Battle of Palo Alto. Grant served as regimental quartermaster, but yearned for a combat role; when finally allowed, he led a charge at the

Battle of Resaca de la Palma

The Battle of Resaca de la Palma was one of the early engagements of the Mexican–American War, where the United States Army under General Zachary Taylor engaged the retreating forces of the Mexican ''Ejército del Norte'' ("Army of the North ...

. He demonstrated his equestrian ability at the

Battle of Monterrey

In the Battle of Monterrey (September 21–24, 1846) during the Mexican–American War, General Pedro de Ampudia and the Mexican Army of the North was defeated by the Army of Occupation, a force of United States Regulars, Volunteers and ...

by volunteering to carry a dispatch past snipers, where he hung off the side of his horse, keeping the animal between him and the enemy. Polk, wary of Taylor's growing popularity, divided his forces, sending some troops (including Grant's unit) to form a new army under Major General

Winfield Scott

Winfield Scott (June 13, 1786May 29, 1866) was an American military commander and political candidate. He served as a general in the United States Army from 1814 to 1861, taking part in the War of 1812, the Mexican–American War, the early s ...

.

Traveling by sea, Scott's army landed at

Veracruz

Veracruz (), formally Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave (), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave), is one of the 31 states which, along with Me ...

and advanced toward

Mexico City

Mexico City ( es, link=no, Ciudad de México, ; abbr.: CDMX; Nahuatl: ''Altepetl Mexico'') is the capital and largest city of Mexico, and the most populous city in North America. One of the world's alpha cities, it is located in the Valley o ...

. The army met the Mexican forces at the battles of

Molino del Rey

Los Pinos (English: ''The Pines'') was the official residence and office of the President of Mexico from 1934 to 2018. Located in the Bosque de Chapultepec (Chapultepec Forest) in central Mexico City, it became the presidential seat in 1934, wh ...

and

Chapultepec. For his bravery at Molino del Rey, Grant was brevetted first lieutenant on September 30. At San Cosmé, Grant directed his men to drag a disassembled

howitzer

A howitzer () is a long- ranged weapon, falling between a cannon (also known as an artillery gun in the United States), which fires shells at flat trajectories, and a mortar, which fires at high angles of ascent and descent. Howitzers, like ot ...

into a church steeple, then reassembled it and bombarded nearby Mexican troops. His bravery and initiative earned him his brevet promotion to captain. On September 14, 1847, Scott's army marched into the city; Mexico

ceded the vast territory, including

California

California is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States, located along the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the List of states and territori ...

, to the U.S. on February 2, 1848.

During the war, Grant established a commendable record as a daring and competent soldier, studied the tactics and strategies of Scott and Taylor, and emerged as a seasoned officer, writing in his memoirs that this is how he learned much about military leadership. In retrospect, although he respected Scott, he identified his own leadership style with Taylor's. Grant later believed the Mexican war was morally unjust and that the territorial gains were designed to expand slavery. He opined that the Civil War was divine punishment for U.S. aggression against Mexico. During the war, Grant discovered his "moral courage" and began to consider a career in the army.

Historians have pointed to the importance of Grant's experience as an assistant quartermaster during the war. Although he was initially averse to the position, it prepared Grant in understanding military supply routes, transportation systems, and logistics, particularly with regard to "provisioning a large, mobile army operating in hostile territory", according to biographer Ronald White. Grant came to recognize how wars could be won or lost by crucial factors beyond the tactical battlefield.

Post-war assignments and resignation

Grant's first post-war assignments took him and Julia to

Detroit

Detroit ( , ; , ) is the largest city in the U.S. state of Michigan. It is also the largest U.S. city on the United States–Canada border, and the seat of government of Wayne County. The City of Detroit had a population of 639,111 at th ...

on November 17, 1848, but he was soon transferred to

Madison Barracks, a desolate outpost in upstate New York, in bad need of supplies and repair. After four months, Grant was sent back to his quartermaster job in Detroit. When the discovery of

gold in California

Gold became highly concentrated in California, United States as the result of global forces operating over hundreds of millions of years. Volcanoes, tectonic plates and erosion all combined to concentrate billions of dollars' worth of gold in the ...

brought droves of prospectors and settlers to the territory, Grant and the 4th infantry were ordered to reinforce the small garrison there. Grant was charged with bringing the soldiers and a few hundred civilians from New York City to Panama,

overland to the Pacific and then north to California. Julia, eight months pregnant with Ulysses Jr., did not accompany him.

While Grant was in Panama, a

cholera

Cholera is an infection of the small intestine by some strains of the bacterium ''Vibrio cholerae''. Symptoms may range from none, to mild, to severe. The classic symptom is large amounts of watery diarrhea that lasts a few days. Vomiting and ...

epidemic killed many soldiers and civilians. Grant organized a field hospital in

Panama City

Panama City ( es, Ciudad de Panamá, links=no; ), also known as Panama (or Panamá in Spanish), is the capital and largest city of Panama. It has an urban population of 880,691, with over 1.5 million in its metropolitan area. The city is locat ...

, and moved the worst cases to a hospital barge one mile offshore. When orderlies protested having to attend to the sick, Grant did much of the nursing himself, earning high praise from observers. In August, Grant arrived in San Francisco. His next assignment sent him north to

Vancouver Barracks in the

Oregon Territory.

Grant tried several business ventures but failed, and in one instance his business partner absconded with $800 of Grant's investment, . Concerning

local Indians, Grant assured Julia, by letter, they were harmless. After he witnessed white agents cheating Indians of their supplies, and their devastation by

smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by variola virus (often called smallpox virus) which belongs to the genus Orthopoxvirus. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (WHO) c ...

and

measles

Measles is a highly contagious infectious disease caused by measles virus. Symptoms usually develop 10–12 days after exposure to an infected person and last 7–10 days. Initial symptoms typically include fever, often greater than , cough, ...

transferred to them by white settlers, he developed empathy for their plight.

Promoted to

captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

on August 5, 1853, Grant was assigned to command Company F,

4th Infantry, at the newly constructed

Fort Humboldt

A fortification is a military construction or building designed for the defense of territories in warfare, and is also used to establish rule in a region during peacetime. The term is derived from Latin ''fortis'' ("strong") and ''facere'' ...

in California. Grant arrived at Fort Humboldt on January 5, 1854, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel

Robert C. Buchanan

Robert Christie Buchanan (March 1, 1811 – November 29, 1878) was an American military officer who served in the Mexican–American War and then was a Colonel (United States), colonel in the Union Army during the American Civil War. In 1866, ...

. Separated from his family, Grant began to drink. Colonel Buchanan reprimanded Grant for one drinking episode and told Grant to "resign or reform." Grant told Buchanan he would "resign if I don't reform." On Sunday, Grant was found influenced by alcohol, but not incapacitated, at his company's paytable. Keeping his pledge to Buchanan, Grant resigned, effective July 31, 1854. Buchanan endorsed Grant's letter of resignation but did not submit any report that verified the incident. Grant did not face court-martial, and the War Department said: "Nothing stands against his good name." Grant said years later, "the vice of intemperance (drunkenness) had not a little to do with my decision to resign." With no means of support, Grant returned to St. Louis and reunited with his family.

Civilian struggles, slavery, and politics

In 1854, at age 32, Grant entered civilian life, without any money-making vocation to support his growing family. It was the beginning of seven years of financial struggles, poverty, and instability. Grant's father offered him a place in the

Galena, Illinois, branch of the family's leather business, but demanded Julia and the children stay in Missouri, with the Dents, or with the Grants in Kentucky. Grant and Julia declined. For the next four years, Grant farmed with the help of Julia's slave, Dan, on his brother-in-law's property, ''Wish-ton-wish'', near

St. Louis. The farm was not successful and to earn an alternate living he sold firewood on St. Louis street corners.

In 1856, the Grants moved to land on Julia's father's farm, and built a home called "Hardscrabble" on

Grant's Farm

Grant's Farm is a historic farm, and long-standing landmark in Grantwood Village, Missouri, built by Ulysses S. Grant on land given to him and his wife by his father in law Frederick Fayette Dent shortly after they became married in 1848. It ...

. Julia described the

rustic house as an "unattractive cabin", but made the dwelling as homelike as possible. Grant's family had little money, clothes, and furniture, but always had enough food. During the

Panic of 1857

The Panic of 1857 was a financial panic in the United States caused by the declining international economy and over-expansion of the domestic economy. Because of the invention of the telegraph by Samuel F. Morse in 1844, the Panic of 1857 was ...

, which devastated Grant as it did many farmers, Grant pawned his gold watch to buy Christmas gifts. In 1858, Grant rented out Hardscrabble and moved his family to Julia's father's

850-acre plantation. That fall, after having

malaria

Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects humans and other animals. Malaria causes symptoms that typically include fever, tiredness, vomiting, and headaches. In severe cases, it can cause jaundice, seizures, coma, or death. S ...

, Grant gave up farming.

That same year, Grant acquired a

slave

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

from his father-in-law, a thirty-five-year-old man named William Jones. Although Grant was not an

abolitionist at the time, he disliked slavery and could not bring himself to force an enslaved man to work. In March 1859, Grant freed Jones by a

manumission

Manumission, or enfranchisement, is the act of freeing enslaved people by their enslavers. Different approaches to manumission were developed, each specific to the time and place of a particular society. Historian Verene Shepherd states that t ...

deed, potentially worth at least $1,000 (equivalent to $ in ).

Grant moved to St. Louis, taking on a partnership with Julia's cousin Harry Boggs working in the real estate business as a bill collector, again without success and at Julia's prompting ended the partnership. In August, Grant applied for a position as county engineer. He had thirty-five notable recommendations, but Grant was passed over by the

Free Soil

The Free Soil Party was a short-lived coalition political party in the United States active from 1848 to 1854, when it merged into the Republican Party. The party was largely focused on the single issue of opposing the expansion of slavery into ...

and

Republican county commissioners because he was believed to share his father-in-law's

Democratic sentiments.

In April 1860, Grant and his family moved north to Galena, accepting a position in his father's leather goods business, "Grant & Perkins", run by his younger brothers Simpson and Orvil. In a few months, Grant paid off his debts. The family attended the local Methodist church and he soon established himself as a reputable citizen.

Civil War

On April 12, 1861, the

American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

began when Confederate troops

attacked Fort Sumter in

Charleston, South Carolina

Charleston is the largest city in the U.S. state of South Carolina, the county seat of Charleston County, and the principal city in the Charleston–North Charleston metropolitan area. The city lies just south of the geographical midpoint o ...

. The news came as a shock in Galena, and Grant shared his neighbors' concern about the war. On April 15, Lincoln called for 75,000 volunteers. The next day, Grant attended a mass meeting to assess the crisis and encourage recruitment, and a speech by his father's attorney,

John Aaron Rawlins

John Aaron Rawlins (February 13, 1831 September 6, 1869) was a general officer in the Union Army during the American Civil War and a cabinet officer in the Presidency of Ulysses S. Grant, Grant administration. A longtime confidant of Ulysses S. G ...

, stirred Grant's patriotism. In an April 21 letter to his father, Grant wrote out his views on the upcoming conflict: "We have a government and laws and a flag, and they must all be sustained. There are but two parties now, Traitors and Patriots."

Early commands

On April 18, Grant chaired a second recruitment meeting, but turned down a captain's position as commander of the newly formed militia company, hoping his experience would aid him to obtain a more senior rank. His early efforts to be recommissioned were rejected by Major General

George B. McClellan and Brigadier General

Nathaniel Lyon. On April 29, supported by Congressman

Elihu B. Washburne

Elihu Benjamin Washburne (September 23, 1816 – October 22, 1887) was an Americans, American politician and diplomat. A member of the Washburn family, which played a prominent role in the early formation of the Republican Party (United States), ...

of Illinois, Grant was appointed military aide to Governor

Richard Yates and mustered ten regiments into the

Illinois militia. On June 14, again aided by Washburne, Grant was appointed colonel and put in charge of the

21st Illinois Volunteer Infantry Regiment

The 21st Regiment Illinois Volunteer Infantry was a volunteer infantry regiment that served in the Union Army during the American Civil War.

History

The regiment was raised under the Ten Regiment Bill, which anticipated Federal troop requirements ...

; he appointed

John A. Rawlins

John Aaron Rawlins (February 13, 1831 September 6, 1869) was a general officer in the Union Army during the American Civil War and a cabinet officer in the Grant administration. A longtime confidant of Ulysses S. Grant, Rawlins served on Grant's ...

as his

aide-de-camp and brought order and discipline to the regiment. Soon after, Grant and the 21st Regiment were transferred to Missouri to dislodge Confederate forces.

On August 5, with Washburne's aid, Grant was appointed brigadier general of volunteers. Major General

John C. Frémont

John Charles Frémont or Fremont (January 21, 1813July 13, 1890) was an American explorer, military officer, and politician. He was a U.S. Senator from California and was the first Republican nominee for president of the United States in 1856 ...

, Union commander of the West, passed over senior generals and appointed Grant commander of the District of Southeastern Missouri. On September 2, Grant arrived at

Cairo, Illinois

Cairo ( ) is the southernmost city in Illinois and the county seat of Alexander County.

The city is located at the confluence of the Ohio and Mississippi rivers. Fort Defiance, a Civil War camp, was built here in 1862 by Union General Ulysses ...

, assumed command by replacing Colonel

Richard J. Oglesby

Richard James Oglesby (July 25, 1824April 24, 1899) was an American soldier and Republican politician from Illinois, The town of Oglesby, Illinois, is named in his honor, as is an elementary school situated in the Auburn Gresham neighborhoo ...

, and set up his headquarters to plan a campaign down the Mississippi, and up the Tennessee and Cumberland rivers.

After the Confederates moved into western Kentucky, taking Columbus, with designs on southern Illinois, Grant notified Frémont and, without waiting for his reply, advanced on

Paducah, Kentucky, taking it without a fight on September 6. Having understood the importance to Lincoln of Kentucky's neutrality, Grant assured its citizens, "I have come among you not as your enemy, but as your friend." On November 1, Frémont ordered Grant to "

make demonstrations" against the Confederates on both sides of the Mississippi, but prohibited him from attacking.

Belmont (1861), Forts Henry and Donelson (1862)

On November 2, 1861, Lincoln removed Frémont from command, freeing Grant to attack Confederate soldiers encamped in

Cape Girardeau, Missouri. On November 5, Grant, along with Brigadier General

John A. McClernand, landed 2,500 men at Hunter's Point, and on November 7 engaged the Confederates at the

Battle of Belmont. The Union army took the camp, but the reinforced Confederates under Brigadier Generals

Frank Cheatham

Benjamin Franklin "Frank" Cheatham (October 20, 1820 – September 4, 1886) was a Tennessee planter, California gold miner, and a general in the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War. He served in the Army of Tennessee, inflicting ...

and

Gideon J. Pillow

Gideon Johnson Pillow (June 8, 1806 – October 8, 1878) was an American lawyer, politician, speculator, slaveowner, United States Army major general of volunteers during the Mexican–American War and Confederate brigadier general in the Americ ...

forced a chaotic Union retreat. Grant had wanted to destroy Confederate strongholds at

Belmont, Missouri

Belmont is an extinct town in Mississippi County, on the eastern border of the U.S. state of Missouri at the Mississippi River. The GNIS classifies it as a populated place under the name "Belmont Landing".

History

Belmont was platted in 1853, and ...

, and

Columbus, Kentucky, but was not given enough troops and was only able to disrupt their positions. Grant's troops escaped back to Cairo under fire from the fortified stronghold at Columbus. Although Grant and his army retreated, the battle gave his volunteers much-needed confidence and experience.

Columbus blocked Union access to the lower Mississippi. Grant and lieutenant colonel

James B. McPherson

James Birdseye McPherson (November 14, 1828 – July 22, 1864) was a career United States Army officer who served as a general in the Union Army during the American Civil War. McPherson was on the General's staff of Henry Halleck and late ...

planned to bypass Columbus and move against

Fort Henry on the

Tennessee River

The Tennessee River is the largest tributary of the Ohio River. It is approximately long and is located in the southeastern United States in the Tennessee Valley. The river was once popularly known as the Cherokee River, among other names, ...

. They would then march east to

Fort Donelson on the

Cumberland River

The Cumberland River is a major waterway of the Southern United States. The U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map, accessed June 8, 2011 river drains almost of southern Kentucky and ...

, with the aid of gunboats, opening both rivers and allowing the Union access further south. Grant presented his plan to

Henry Halleck, his new commander in the newly created

Department of Missouri. Halleck rebuffed Grant, believing he needed twice the number of troops. However, after consulting McClellan, he finally agreed on the condition that the attack would be in close cooperation with the navy

Flag Officer,

Andrew H. Foote

Andrew Hull Foote (September 12, 1806 – June 26, 1863) was an American naval officer who was noted for his service in the American Civil War and also for his contributions to several naval reforms in the years prior to the war. When the war cam ...

. Foote's gunboats bombarded Fort Henry, leading to its surrender on February 6, 1862, before Grant's infantry even arrived.

Grant ordered an immediate

assault on Fort Donelson, which dominated the Cumberland River. Unaware of the garrison's strength, Grant, McClernand, and Smith positioned their divisions around the fort. The next day McClernand and Smith independently launched probing attacks on apparent weak spots but were forced to retreat. On February 14, Foote's gunboats began bombarding the fort, only to be repulsed by its heavy guns. The next day, Pillow attacked and routed McClernand's division. Union reinforcements arrived, giving Grant a total force of over 40,000 men. Grant was with Foote four miles away when the Confederates attacked. Hearing the battle, Grant rode back and rallied his troop commanders, riding over seven miles of freezing roads and trenches, exchanging reports. When Grant blocked the Nashville Road, the Confederates retreated back into Fort Donelson. On February 16, Foote resumed his bombardment, signaling a general attack. Confederate generals

John B. Floyd

John Buchanan Floyd (June 1, 1806 – August 26, 1863) was the 31st Governor of Virginia, U.S. Secretary of War, and the Confederate general in the American Civil War who lost the crucial Battle of Fort Donelson.

Early family life

John Buchan ...

and Pillow fled, leaving the fort in command of

Simon Bolivar Buckner, who submitted to Grant's demand for "unconditional and immediate surrender".

Grant had won the first major victory for the Union, capturing Floyd's entire army of more than 12,000. Halleck was angry that Grant had acted without his authorization and complained to McClellan, accusing Grant of "neglect and inefficiency". On March 3, Halleck sent a telegram to Washington complaining that he had no communication with Grant for a week. Three days later, Halleck claimed "word has just reached me that ... Grant has resumed his bad habits (of drinking)." Lincoln, regardless, promoted Grant to major general of volunteers and the Northern press treated Grant as a hero. Playing off his initials, they took to calling him "Unconditional Surrender Grant".

Shiloh (1862) and aftermath

Reinstated by Halleck at the urging of Lincoln and Secretary of War

Edwin Stanton, Grant rejoined his army with orders to advance with the

Army of the Tennessee into Tennessee. His main army was located at

Pittsburg Landing

Pittsburg Landing is a river landing on the west bank of the Tennessee River in Hardin County, Tennessee. It was named for "Pitts" Tucker who operated a tavern at the site in the years preceding the Civil War. It is located at latitude 35.15222 ...

, while 40,000 Confederate troops converged at

Corinth, Mississippi. Grant wanted to attack the Confederates at Corinth, but Halleck ordered him not to attack until Major General

Don Carlos Buell arrived with his division of 25,000. Grant prepared for an attack on the Confederate army of roughly equal strength. Instead of preparing defensive fortifications, they spent most of their time drilling the largely inexperienced troops while Sherman dismissed reports of nearby Confederates.

On the morning of April 6, 1862, Grant's troops were taken by surprise when the Confederates, led by Generals

Albert Sidney Johnston

Albert Sidney Johnston (February 2, 1803 – April 6, 1862) served as a general in three different armies: the Texian Army, the United States Army, and the Confederate States Army. He saw extensive combat during his 34-year military career, figh ...

and

P. G. T. Beauregard

Pierre Gustave Toutant-Beauregard (May 28, 1818 - February 20, 1893) was a Confederate general officer of Louisiana Creole descent who started the American Civil War by leading the attack on Fort Sumter on April 12, 1861. Today, he is commonly ...

, struck first "like an Alpine avalanche" near Shiloh church, attacking five divisions of Grant's army and forcing a confused retreat toward the Tennessee River. Johnston was killed and command fell upon Beauregard. One Union line held the Confederate attack off for several hours, giving Grant time to assemble artillery and 20,000 troops near Pittsburg Landing. The Confederates finally broke and captured a Union division, but Grant's newly assembled line held the landing, while the exhausted Confederates, lacking reinforcements, halted their advance.

Bolstered by 18,000 troops from the divisions of Major Generals Buell and

Lew Wallace, Grant counterattacked at dawn the next day and regained the field, forcing the disorganized and demoralized rebels to retreat to Corinth. Halleck ordered Grant not to advance more than one day's march from Pittsburg Landing, stopping the pursuit. Although Grant had won the battle, the situation was little changed. Grant, now realizing that the South was determined to fight, would later write, "Then, indeed, I gave up all idea of saving the Union except by complete conquest."

Shiloh was the costliest battle in American history to that point and the staggering 23,746 casualties stunned the nation. Briefly hailed a hero for routing the Confederates, Grant was soon mired in controversy. The Northern press castigated Grant for shockingly high casualties, and accused him of drunkenness during the battle, contrary to the accounts of those with him at the time. Discouraged, Grant considered resigning but Sherman convinced him to stay. Lincoln dismissed Grant's critics, saying "I can't spare this man; he fights." Grant's costly victory at Shiloh ended any chance for the Confederates to prevail in the Mississippi valley or regain its strategic advantage in the West.

Halleck arrived from St. Louis on April 11, took command, and assembled a combined army of about 120,000 men. On April 29, he relieved Grant of field command and replaced him with Major General

George Henry Thomas

George Henry Thomas (July 31, 1816March 28, 1870) was an American general in the Union Army during the American Civil War and one of the principal commanders in the Western Theater.

Thomas served in the Mexican–American War and later chose ...

. Halleck slowly marched his army to take Corinth, entrenching each night. Meanwhile, Beauregard pretended to be reinforcing, sent "deserters" to the Union Army with that story, and moved his army out during the night, to Halleck's surprise when he finally

arrived at Corinth on May 30.

Halleck divided his combined army and reinstated Grant as field commander on July 11. Later that year, on September 19, Grant's army defeated Confederates at the

Battle of Iuka, then successfully

defended Corinth, inflicting heavy casualties. On October 25, Grant assumed command of the District of the Tennessee. In November, after Lincoln's preliminary

Emancipation Proclamation

The Emancipation Proclamation, officially Proclamation 95, was a presidential proclamation and executive order issued by United States President Abraham Lincoln on January 1, 1863, during the Civil War. The Proclamation changed the legal sta ...

, Grant ordered units under his command to incorporate former slaves into the Union Army, giving them clothes, shelter, and wages for their services.

Vicksburg campaign (1862–1863)

The Union capture of

Vicksburg Vicksburg most commonly refers to:

* Vicksburg, Mississippi, a city in western Mississippi, United States

* The Vicksburg Campaign, an American Civil War campaign

* The Siege of Vicksburg, an American Civil War battle

Vicksburg is also the name of ...

, the last Confederate stronghold on the

Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson Bay drainage system. From its traditional source of Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota, it f ...

, was considered vital as it would split the Confederacy in two. Lincoln appointed McClernand for the job, rather than Grant or Sherman. Halleck, who retained power over troop displacement, ordered McClernand to

Memphis, and placed him and his troops under Grant's authority.

On November 13, 1862, Grant captured

Holly Springs and advanced to

Corinth

Corinth ( ; el, Κόρινθος, Kórinthos, ) is the successor to an ancient city, and is a former municipality in Corinthia, Peloponnese, which is located in south-central Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform, it has been part o ...

. His plan was to attack Vicksburg overland, while Sherman would attack Vicksburg from Chickasaw Bayou. However, Confederate cavalry raids on December 11 and 20 broke Union communications and recaptured Holly Springs, preventing Grant and Sherman from converging on Vicksburg. McClernand reached Sherman's army, assumed command, and independently of Grant led a campaign that captured Confederate

Fort Hindman

The Arkansas Post (french: Poste de Arkansea) (Spanish: ''Puesto de Arkansas''), formally the Arkansas Post National Memorial, was the first European settlement in the Mississippi Alluvial Plain and present-day U.S. state of Arkansas. In 168 ...

. After the sack of Holly Springs, Grant considered and sometimes adopted the strategy of foraging the land, rather than exposing long Union supply lines to enemy attack.

Fugitive

African-American

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an Race and ethnicity in the United States, ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American ...

slaves poured into Grant's district, whom he sent north to Cairo to be domestic servants in Chicago. However, Lincoln ended this when Illinois political leaders complained. On his own initiative, Grant set up a pragmatic program and hired Presbyterian chaplain

John Eaton John Eaton may refer to:

* John Eaton (divine) (born 1575), English divine

*John Eaton (pirate) (fl. 1683–1686), English buccaneer

*Sir John Craig Eaton (1876–1922), Canadian businessman

*John Craig Eaton II (born 1937), Canadian businessman an ...

to administer

contraband

Contraband (from Medieval French ''contrebande'' "smuggling") refers to any item that, relating to its nature, is illegal to be possessed or sold. It is used for goods that by their nature are considered too dangerous or offensive in the eyes o ...

camps. Freed slaves picked cotton that was shipped north to aid the Union war effort. Lincoln approved and Grant's program was successful. Grant also worked freed black labor on

a canal to bypass Vicksburg, incorporating the laborers into the Union Army and Navy.

Grant's war responsibilities included combating illegal Northern cotton trade and civilian obstruction. He had received numerous complaints about Jewish speculators in his district. The majority, however, of those involved in illegal trading were not Jewish. To help combat this, Grant required two permits, one from the Treasury and one from the Union Army, to purchase cotton. On December 17, 1862, Grant issued a controversial

General Order No. 11, expelling "Jews, as a class", from his military district. After complaints, Lincoln rescinded the order on January 3, 1863. Grant finally ended the order on January 17. He later described issuing the order as one of his biggest regrets.

On January 29, 1863, Grant assumed overall command. To bypass Vicksburg's guns, Grant slowly advanced his Union army south through water-logged terrain. The plan of attacking Vicksburg from downriver was risky because, east of the river, his army would be distanced from most of its supply lines, and would have to rely on foraging. On April 16, Grant ordered Admiral

David Dixon Porter

David Dixon Porter (June 8, 1813 – February 13, 1891) was a United States Navy admiral and a member of one of the most distinguished families in the history of the U.S. Navy. Promoted as the second U.S. Navy officer ever to attain the rank o ...

's gunboats south under fire from the Vicksburg batteries to meet up with troops who had marched south down the west side of the river. Grant ordered diversionary battles, confusing Pemberton and allowing Grant's army to move east across the Mississippi. Grant's army

captured Jackson. Advancing west, he defeated Pemberton's army at the

Battle of Champion Hill

The Battle of Champion Hill of May 16, 1863, was the pivotal battle in the Vicksburg Campaign of the American Civil War (1861–1865). Union Army commander Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant and the Army of the Tennessee pursued the retreating Confe ...

on May 16, forcing their retreat into Vicksburg.

After Grant's men assaulted the entrenchments twice, suffering severe losses, they settled in for

a siege which lasted seven weeks. During quiet periods of the campaign, Grant would drink on occasion. The personal rivalry between McClernand and Grant continued until Grant removed him from command when he contravened Grant by publishing an order without permission. Pemberton surrendered Vicksburg to Grant on July 4, 1863.

Vicksburg's fall gave Union forces control of the Mississippi River and split the Confederacy. By that time, Grant's political sympathies fully coincided with the

Radical Republicans' aggressive prosecution of the war and emancipation of the slaves. The success at Vicksburg was a morale boost for the Union war effort. When Stanton suggested Grant be brought east to run the

Army of the Potomac

The Army of the Potomac was the principal Union Army in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. It was created in July 1861 shortly after the First Battle of Bull Run and was disbanded in June 1865 following the surrender of the Confedera ...

, Grant demurred, writing that he knew the geography and resources of the West better and he did not want to upset the chain of command in the East.

Chattanooga (1863) and promotion

On October 16, 1863, Lincoln promoted Grant to major general in the regular army and assigned him command of the newly formed

Division of the Mississippi, which comprised the Armies of the

Ohio

Ohio () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. Of the fifty U.S. states, it is the 34th-largest by area, and with a population of nearly 11.8 million, is the seventh-most populous and tenth-most densely populated. The sta ...

, the Tennessee, and the

Cumberland

Cumberland ( ) is a historic county in the far North West England. It covers part of the Lake District as well as the north Pennines and Solway Firth coast. Cumberland had an administrative function from the 12th century until 1974. From 19 ...

. After the

Battle of Chickamauga

The Battle of Chickamauga, fought on September 19–20, 1863, between United States, U.S. and Confederate States of America, Confederate forces in the American Civil War, marked the end of a Union Army, Union offensive, the Chickamauga Campaign ...

, the Army of the Cumberland retreated into Chattanooga, where they were partially besieged. Grant arrived in Chattanooga, where plans to resupply and break the partial siege had already been set. Forces commanded by Major General

Joseph Hooker, which had been sent from the Army of the Potomac, approached from the west and linked up with other units moving east from inside the city, capturing Brown's Ferry and opening a supply line to the railroad at Bridgeport.

Grant planned to have Sherman's Army of the Tennessee, assisted by the Army of the Cumberland, assault the northern end of

Missionary Ridge

Missionary Ridge is a geographic feature in Chattanooga, Tennessee, site of the Battle of Missionary Ridge, a battle in the American Civil War, fought on November 25, 1863. Union forces under Maj. Gens. Ulysses S. Grant, William T. Sherman, a ...

and roll down it on the enemy's right flank. On November 23, Major General

George Henry Thomas

George Henry Thomas (July 31, 1816March 28, 1870) was an American general in the Union Army during the American Civil War and one of the principal commanders in the Western Theater.

Thomas served in the Mexican–American War and later chose ...

surprised the enemy in open daylight, advancing the Union lines and taking Orchard Knob, between Chattanooga and the ridge. The next day, Sherman failed to get atop Missionary Ridge, which was key to Grant's plan of battle. Hooker's forces took

Lookout Mountain

Lookout Mountain is a mountain ridge located at the northwest corner of the U.S. state of Georgia, the northeast corner of Alabama, and along the southeastern Tennessee state line in Chattanooga. Lookout Mountain was the scene of the 18th-centu ...

in unexpected success. On the 25th, Grant ordered Thomas to advance to the rifle-pits at the base of Missionary Ridge after Sherman's army failed to take Missionary Ridge from the northeast. Four divisions of the Army of the Cumberland, with the center two led by Major General

Philip Sheridan

General of the Army Philip Henry Sheridan (March 6, 1831 – August 5, 1888) was a career United States Army officer and a Union general in the American Civil War. His career was noted for his rapid rise to major general and his close as ...

and Brigadier General

Thomas J. Wood

Thomas John Wood (September 25, 1823 – February 26, 1906) was a career United States Army officer. He served in the Mexican–American War and as a Union (American Civil War), Union General officer, general during the American Civil War.

Duri ...

, chased the Confederates out of the rifle-pits at the base and, against orders, continued the charge up the 45-degree slope and captured the Confederate entrenchments along the crest, forcing a hurried retreat. The decisive battle gave the Union control of Tennessee and opened

Georgia, the Confederate heartland, to Union invasion.

On March 2, 1864, Lincoln promoted Grant to lieutenant general, giving him command of all Union Armies. Grant's new rank had previously been held only by

George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of th ...

. Grant arrived in Washington on March 8 and was formally commissioned by Lincoln the next day at a Cabinet meeting. Grant developed a good working relationship with Lincoln, who allowed Grant to devise his own strategy.

Grant established his headquarters with General

George Meade's Army of the Potomac in

Culpeper, Virginia

Culpeper (formerly Culpeper Courthouse, earlier Fairfax) is an incorporated town in Culpeper County, Virginia, United States. The population was 20,062 at the 2020 census, up from 16,379 at the 2010 census. It is the county seat of Culpeper Coun ...

, and met weekly with Lincoln and Stanton in Washington. After protest from Halleck, Grant scrapped a risky invasion of North Carolina and planned five coordinated Union offensives to prevent Confederate armies from shifting troops along interior lines. Grant and Meade would make a direct frontal attack on

Robert E. Lee

Robert Edward Lee (January 19, 1807 – October 12, 1870) was a Confederate general during the American Civil War, towards the end of which he was appointed the overall commander of the Confederate States Army. He led the Army of Nort ...

's

Army of Northern Virginia, while Sherman—now in command of all western armies—would destroy

Joseph E. Johnston's

Army of Tennessee and take Atlanta. Major General

Benjamin Butler would advance on Lee from the southeast, up the

James River

The James River is a river in the U.S. state of Virginia that begins in the Appalachian Mountains and flows U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map , accessed April 1, 2011 to Chesapea ...

, while Major General

Nathaniel Banks would capture

Mobile. Major General

Franz Sigel was to capture granaries and rail lines in the fertile

Shenandoah Valley

The Shenandoah Valley () is a geographic valley and cultural region of western Virginia and the Eastern Panhandle of West Virginia. The valley is bounded to the east by the Blue Ridge Mountains, to the west by the eastern front of the Ridge- ...

. Grant now commanded 533,000 battle-ready troops spread out over an eighteen-mile front.

Overland Campaign (1864)

The Overland Campaign was a series of brutal battles fought in Virginia during May and June 1864. Sigel's and Butler's efforts failed, and Grant was left alone to fight Lee. On May 4, Grant led the army from his headquarters towards Germanna Ford. They crossed the

Rapidan unopposed. On May 5, the Union army attacked Lee in the

battle of the Wilderness

The Battle of the Wilderness was fought on May 5–7, 1864, during the American Civil War. It was the first battle of Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant's 1864 Virginia Overland Campaign against General Robert E. Lee and the Confederate Arm ...

, a three-day battle with estimated casualties of 17,666 Union and 11,125 Confederate.

Rather than retreat, Grant flanked Lee's army to the southeast and attempted to wedge his forces between Lee and Richmond at

Spotsylvania Court House

The Battle of Spotsylvania Court House, sometimes more simply referred to as the Battle of Spotsylvania (or the 19th-century spelling Spottsylvania), was the second major battle in Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant and Maj. Gen. George G. Meade's 1864 ...

. Lee's army got to Spotsylvania first and a costly battle ensued, lasting thirteen days, with heavy casualties. On May 12, Grant attempted to break through Lee's ''Muleshoe'' salient guarded by Confederate artillery, resulting in one of the bloodiest assaults of the Civil War, known as

the Bloody Angle. Unable to break Lee's lines, Grant again flanked the rebels to the southeast, meeting at

North Anna, where a battle lasted three days.

Cold Harbor

The recent bloody Wilderness campaign had severely diminished Confederate morale; Grant believed breaking through Lee's lines at its weakest point,

Cold Harbor

The Battle of Cold Harbor was fought during the American Civil War near Mechanicsville, Virginia, from May 31 to June 12, 1864, with the most significant fighting occurring on June 3. It was one of the final battles of Union Lt. Gen. Ulysses S ...

, a vital road hub that linked to Richmond, would mean a quick end to the war. Grant already had two corps in position at Cold Harbor with Hancock's corps on the way.

Lee's lines were extended north and east of Richmond and Petersburg for approximately ten miles, but at several points there were no fortifications built yet, including Cold Harbor. On June 1 and 2 both Grant and Lee were waiting for reinforcements to arrive. Hancock's men had marched all night and arrived too exhausted for an immediate attack that morning. Grant postponed the attack until 5 p.m., and then again until 4:30 a.m. on June 3. However, Grant and Meade did not give specific orders for the attack, leaving it up to the corps commanders to coordinate. Grant had not yet learned that overnight Lee had hastily constructed entrenchments to thwart any breach attempt at Cold Harbor. Grant was anxious to make his move before the rest of Lee's army arrived. On the morning of June 3, with a force of more than 100,000 men, against Lee's 59,000, Grant attacked, not realizing that Lee's army was now well entrenched, much of it obscured by trees and bushes. Grant's army suffered 12,000–14,000 casualties, while Lee's army suffered 3,000–5,000 casualties, but Lee was less able to replace them.

The unprecedented number of casualties heightened anti-war sentiment in the North. After the battle, Grant wanted to appeal to Lee under the white flag for each side to gather up their wounded, most of them Union soldiers, but Lee insisted that a total truce be enacted and while they were deliberating all but a few of the wounded died in the field. Without giving an apology for the disastrous defeat in his official military report, Grant confided in his staff after the battle and years later wrote in his memoirs that he "regretted that the last assault at Cold Harbor was ever made."

Siege of Petersburg (1864–1865)

Undetected by Lee, Grant moved his army south of the James River, freed Butler from

the Bermuda Hundred, and advanced toward

Petersburg

Petersburg, or Petersburgh, may refer to:

Places Australia

*Petersburg, former name of Peterborough, South Australia

Canada

* Petersburg, Ontario

Russia

*Saint Petersburg, sometimes referred to as Petersburg

United States

*Peterborg, U.S. Virg ...

, Virginia's central railroad hub, resulting in

a nine-month siege. Northern resentment grew. Sheridan was assigned command of the

Union Army of the Shenandoah

The Army of the Shenandoah was a Union army during the American Civil War. First organized as the ''Department of the Shenandoah'' in 1861 and then disbanded in early 1862, it became most effective after its recreation on August 1, 1864, under Phi ...

and Grant directed him to "follow the enemy to their death" in the Shenandoah Valley. After Grant's abortive attempt to capture Petersburg, Lincoln supported Grant in his decision to continue.

Grant had to commit troops to check Confederate General

Jubal Early's raids in the Shenandoah Valley, which were getting dangerously close to Washington. By late July, at Petersburg, Grant reluctantly approved a plan to

blow up part of the enemy trenches from a tunnel filled with gunpowder. The massive explosion instantly killed an entire Confederate regiment. The poorly led Union troops under Major General

Ambrose Burnside and Brigadier General

James H. Ledlie

James Hewett Ledlie (April 14, 1832 – August 15, 1882) was a civil engineer for American railroads and a general in the Union Army during the American Civil War. He is best known for his dereliction of duty at the Battle of the Crater during t ...

, rather than encircling the crater, rushed into it. Recovering from the surprise, Confederates, led by Major General

William Mahone, surrounded the crater and easily picked off Union troops. The Union's 3,500 casualties outnumbered the Confederates' three-to-one. The battle marked the first time that Union black troops, who endured a large proportion of the casualties, engaged in any major battle in the east. Grant admitted that the tactic had been a "stupendous failure".

Grant would later meet with Lincoln and testify at a court of inquiry against Generals Burnside and Ledlie for their incompetence. In his memoirs, he blamed them for that disastrous Union defeat. Rather than fight Lee in a full-frontal attack as he had done at Cold Harbor, Grant continued to force Lee to extend his defenses south and west of Petersburg, better allowing him to capture essential railroad links.

Union forces soon captured

Mobile Bay and

Atlanta

Atlanta ( ) is the capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Georgia. It is the seat of Fulton County, the most populous county in Georgia, but its territory falls in both Fulton and DeKalb counties. With a population of 498,715 ...

and now controlled the Shenandoah Valley, ensuring Lincoln's reelection in November. Sherman convinced Grant and Lincoln to allow his army to

march on Savannah. Sherman cut a path of destruction unopposed, reached the Atlantic Ocean, and captured Savannah on December 22. On December 16, after much prodding by Grant, the Union Army under Thomas smashed

John Bell Hood's Confederates at

Nashville

Nashville is the capital city of the U.S. state of Tennessee and the seat of Davidson County. With a population of 689,447 at the 2020 U.S. census, Nashville is the most populous city in the state, 21st most-populous city in the U.S., and the ...

. These campaigns left Lee's forces at Petersburg as the only significant obstacle remaining to Union victory.

By March 1865, Lee was trapped and his strength severely weakened. He was running out of reserves to replace the high battlefield casualties and remaining Confederate troops, no longer having confidence in their commander and under the duress of trench warfare, deserted by the thousands. On March 25, in a desperate effort, Lee sacrificed his remaining troops (4,000 Confederate casualties) at

Fort Stedman, a Union victory and the last Petersburg line battle.

Surrender of Lee and Union victory (1865)

On April 2, Grant ordered a general assault on Lee's forces; Lee abandoned Petersburg and Richmond, which Grant captured. A desperate Lee and part of his army attempted to link up with the remnants of

Joseph E. Johnston's army. Sheridan's cavalry stopped the two armies from converging, cutting them off from their supply trains. Grant sent his aide

Orville Babcock

Orville Elias Babcock (December 25, 1835 – June 2, 1884) was an American engineer and general in the Union Army during the Civil War. An aide to General Ulysses S. Grant during and after the war, he was President Grant's military private secret ...

to carry his last dispatch to Lee demanding his surrender. Grant immediately rode west, bypassing Lee's army, to join Sheridan who had captured

Appomattox Station

Appomattox Station was located in the town of Appomattox, Virginia (at the time, known as, West Appomattox) and was the site of the Battle of Appomattox Station on the day before General Robert E. Lee surrendered the Army of Northern Virginia to Li ...

, blocking Lee's escape route. On his way, Grant received a letter from Lee stating Lee would surrender his army.

On April 9, Grant and Lee met at

Appomattox Court House Appomattox Court House could refer to:

* The village of Appomattox Court House, now the Appomattox Court House National Historical Park, in central Virginia (U.S.), where Confederate army commander Robert E. Lee surrendered to Union commander Ulyss ...

. Although Grant felt depressed at the fall of "a foe who had fought so long and valiantly," he believed the Southern cause was "one of the worst for which a people ever fought." Grant wrote out the terms of surrender: "each officer and man will be allowed to return to his home, not to be disturbed by U.S. authority so long as they observe their paroles and the laws in force where they may reside." Lee immediately accepted Grant's terms and signed the surrender document, without any diplomatic recognition of the Confederacy. Lee asked that his former Confederate troops keep their horses, which Grant generously allowed. Grant ordered his troops to stop all celebration, saying the "war is over; the rebels are our countrymen again." Johnston's Tennessee army surrendered on April 26, 1865,

Richard Taylor's Alabama army on May 4, and

Kirby Smith's Texas army on May 26, ending the war.

Lincoln's assassination

On April 14, 1865, Grant attended a cabinet meeting in Washington. Lincoln invited him and his wife Julia to

Ford's Theatre but they declined, because they planned to travel to their home in

Burlington

Burlington may refer to:

Places Canada Geography

* Burlington, Newfoundland and Labrador

* Burlington, Nova Scotia

* Burlington, Ontario, the most populous city with the name "Burlington"

* Burlington, Prince Edward Island

* Burlington Bay, no ...

. In a conspiracy that also targeted top cabinet members in one last effort to topple the Union, Lincoln was shot by

John Wilkes Booth at the theater and died the next morning. Many, including Grant himself, thought that Grant had been a target in the plot, and during the subsequent trial, the government tried to prove that Grant had been stalked by Booth's conspirator

Michael O'Laughlen

Michael O'Laughlen, Jr. (pronounced ''Oh-Lock-Lun''; June 3, 1840 – September 23, 1867) was an American Confederate soldier and conspirator in John Wilkes Booth's plot to kidnap U.S. President Abraham Lincoln, and later in the latter's assassi ...

. Stanton notified Grant of the president's death and summoned him to Washington. Vice President

Andrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson (December 29, 1808July 31, 1875) was the 17th president of the United States, serving from 1865 to 1869. He assumed the presidency as he was vice president at the time of the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. Johnson was a Dem ...

was

sworn in

Traditionally an oath (from Anglo-Saxon ', also called plight) is either a statement of fact or a promise taken by a sacrality as a sign of verity. A common legal substitute for those who conscientiously object to making sacred oaths is to giv ...

as president on April 15. Grant was determined to work with Johnson, and he privately expressed "every reason to hope" in the new president's ability to run the government "in its old channel".

Commanding generalship (1865–1869)

At the war's end, Grant remained commander of the army, with duties that included dealing with

Emperor Maximilian and French troops in Mexico, enforcement of Reconstruction in the former Confederate states, and supervision of Indian wars on the western Plains. After the

Grand Review of the Armies

The Grand Review of the Armies was a military procession and celebration in the national capital city of Washington, D.C., on May 23–24, 1865, following the Union victory in the American Civil War (1861–1865). Elements of the Union Army in the ...

, Lee and his generals were indicted for treason in Virginia. Johnson demanded they be put on trial, but Grant insisted that they should not be tried, citing his Appomatox amnesty. Charges against Lee were dropped. Grant secured a house for his family in Georgetown Heights in 1865 but instructed Elihu Washburne that for political purposes his legal residence remained in Galena, Illinois. On July 25, 1866, Congress promoted Grant to the newly created rank of

General of the Army of the United States

General of the Army (abbreviated as GA) is a five-star general officer and the second-highest possible rank in the United States Army. It is generally equivalent to the rank of Field Marshal in other countries. In the United States, a Gener ...

.

Tour of the South

President Johnson's Reconstruction policy included a speedy return of the former Confederates to Congress, reinstating white people to office in the South, and relegating black people to second-class citizenship. On November 27, 1865, Grant was sent by Johnson on a fact-finding mission to the South, to counter a pending less favorable report by Senator

Carl Schurz

Carl Schurz (; March 2, 1829 – May 14, 1906) was a German revolutionary and an American statesman, journalist, and reformer. He immigrated to the United States after the German revolutions of 1848–1849 and became a prominent member of the new ...

which reported that white people in the South harbored resentment of the North, and that black people suffered from violence and fraud. Grant recommended continuation of the

Freedmen's Bureau

The Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands, usually referred to as simply the Freedmen's Bureau, was an agency of early Reconstruction, assisting freedmen in the South. It was established on March 3, 1865, and operated briefly as a ...

, which Johnson opposed, but advised against using black troops.

Grant believed the people of the South were not ready for self-rule and required federal government protection. Concerned that the war led to diminished respect for civil authorities, he continued using the Army to maintain order. Grant's report on the South, which he later recanted, sympathized with Johnson's Reconstruction policies. Although Grant desired former Confederates be returned to Congress, he advocated eventual black citizenship. On December 19, the day after the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment was announced in the Senate, Johnson's response used Grant's report, read aloud to the Senate, to undermine Schurz's final report and Radical opposition to Johnson's policies.

Break from Johnson

Grant was initially optimistic about Johnson. Despite differing styles, the two got along cordially and Grant attended cabinet meetings concerning Reconstruction. By February 1866, the relationship began to break down. Johnson opposed Grant's closure of the ''

Richmond Examiner

The ''Richmond Examiner'', a newspaper which was published before and during the American Civil War under the masthead of ''Daily Richmond Examiner'', was one of the newspapers published in the Confederate capital of Richmond. Its editors viewed ...

'' for disloyal editorials and his enforcement of the

Civil Rights Act of 1866

The Civil Rights Act of 1866 (, enacted April 9, 1866, reenacted 1870) was the first United States federal law to define citizenship and affirm that all citizens are equally protected by the law. It was mainly intended, in the wake of the Amer ...

, passed over Johnson's veto. Needing Grant's popularity, Johnson took Grant on his "

Swing Around the Circle

Swing Around the Circle is the nickname for a speaking campaign undertaken by United States President Andrew Johnson between August 27 and September 15, 1866, in which he tried to gain support for his mild Reconstruction policies and for his prefe ...

" tour, a failed attempt to gain national support for lenient policies toward the South. Grant privately called Johnson's speeches a "national disgrace" and he left the tour early. On March 2, 1867, overriding Johnson's veto, Congress passed the first of three

Reconstruction Acts, using military officers to enforce the policy. Protecting Grant, Congress passed the Command of the Army Act, preventing his removal or relocation, and forcing Johnson to pass orders through Grant.

In August 1867, bypassing the

Tenure of Office Act, Johnson discharged Secretary of War