Ulster Loyalist on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Ulster loyalism is a strand of Ulster unionism associated with

Ulster loyalism is a strand of Ulster unionism associated with

.

The Unionist governments of Northern Ireland were accused of discrimination against the Irish nationalist and Catholic minority. A non-violent campaign to end discrimination began in the late 1960s. This civil rights campaign was opposed by loyalists, who accused it of being a republican front. Loyalist opposition was led primarily by

The Unionist governments of Northern Ireland were accused of discrimination against the Irish nationalist and Catholic minority. A non-violent campaign to end discrimination began in the late 1960s. This civil rights campaign was opposed by loyalists, who accused it of being a republican front. Loyalist opposition was led primarily by

Loyalist representatives had helped negotiate the

Loyalist representatives had helped negotiate the

Loyalist paramilitary and vigilante groups have been active since the early 20th century. In 1912, the Ulster Volunteers were formed to stop the British Government granting self-rule to Ireland, or to exclude Ulster from it. This led to the Home Rule Crisis, which was defused by the onset of

Loyalist paramilitary and vigilante groups have been active since the early 20th century. In 1912, the Ulster Volunteers were formed to stop the British Government granting self-rule to Ireland, or to exclude Ulster from it. This led to the Home Rule Crisis, which was defused by the onset of

In Northern Ireland there are a number of Protestant fraternities and marching bands who hold yearly parades. They include the

In Northern Ireland there are a number of Protestant fraternities and marching bands who hold yearly parades. They include the

Progressive Unionist Party

{{Ethnic nationalism Ethnicity in politics Identity politics Loyalist Religious nationalism The Troubles (Northern Ireland)

Ulster loyalism is a strand of Ulster unionism associated with

Ulster loyalism is a strand of Ulster unionism associated with working class

The working class (or labouring class) comprises those engaged in manual-labour occupations or industrial work, who are remunerated via waged or salaried contracts. Working-class occupations (see also " Designation of workers by collar colo ...

Ulster Protestants

Ulster Protestants ( ga, Protastúnaigh Ultach) are an ethnoreligious group in the Irish province of Ulster, where they make up about 43.5% of the population. Most Ulster Protestants are descendants of settlers who arrived from Britain in the e ...

in Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland ( ga, Tuaisceart Éireann ; sco, label=Ulster-Scots, Norlin Airlann) is a part of the United Kingdom, situated in the north-east of the island of Ireland, that is variously described as a country, province or region. North ...

. Like other unionists, loyalists support the continued existence of Northern Ireland within the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the European mainland, continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

, and oppose a united Ireland. Unlike other strands of unionism, loyalism has been described as an ethnic nationalism

Ethnic nationalism, also known as ethnonationalism, is a form of nationalism wherein the nation and nationality are defined in terms of ethnicity, with emphasis on an ethnocentric (and in some cases an ethnocratic) approach to various polit ...

of Ulster Protestants and "a variation of British nationalism". Loyalists are often said to have a conditional loyalty to the British state so long as it defends their interests.Smithey, Lee. ''Unionists, Loyalists, and Conflict Transformation in Northern Ireland''. Oxford University Press, 2011. pp.56–58 They see themselves as loyal primarily to the Protestant British monarchy

The monarchy of the United Kingdom, commonly referred to as the British monarchy, is the constitutional form of government by which a hereditary sovereign reigns as the head of state of the United Kingdom, the Crown Dependencies (the Bailiw ...

rather than to British governments and institutions, while Garret FitzGerald

Garret Desmond FitzGerald (9 February 192619 May 2011) was an Irish Fine Gael politician, economist and barrister who served twice as Taoiseach, serving from 1981 to 1982 and 1982 to 1987. He served as Leader of Fine Gael from 1977 to 1987, a ...

argued they are loyal to 'Ulster' over 'the Union'. A small minority of loyalists have called for an independent Ulster Protestant state, believing they cannot rely on British governments to support them (see Ulster nationalism). The term 'loyalism' is usually associated with paramilitarism.Glossary of terms on the Northern Ireland conflict.

Conflict Archive on the Internet

CAIN (Conflict Archive on the Internet) is a database containing information about Conflict and Politics in Northern Ireland from 1968 to the present. The project began in 1996, with the website launching in 1997. The project is based within U ...

(CAIN)

Ulster loyalism emerged in the late 19th century, in reaction to the Irish Home Rule movement

The Irish Home Rule movement was a movement that campaigned for self-government (or "home rule") for Ireland within the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. It was the dominant political movement of Irish nationalism from 1870 to the ...

and the rise of Irish nationalism

Irish nationalism is a nationalist political movement which, in its broadest sense, asserts that the people of Ireland should govern Ireland as a sovereign state. Since the mid-19th century, Irish nationalism has largely taken the form of cu ...

. Although Ireland’s native population were almost exclusively Irish speaking Catholics

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

who were deeply committed to the reestablishment of self-government, the population of four counties in the northeast of the province

A province is almost always an administrative division within a country or state. The term derives from the ancient Roman ''provincia'', which was the major territorial and administrative unit of the Roman Empire's territorial possessions outsi ...

of Ulster

Ulster (; ga, Ulaidh or ''Cúige Uladh'' ; sco, label=Ulster Scots, Ulstèr or ''Ulster'') is one of the four traditional Irish provinces. It is made up of nine counties: six of these constitute Northern Ireland (a part of the United Kin ...

had been so thoroughly replaced by colonists from Britain that unionist Protestants ultimately established majorities, largely due to the Plantation of Ulster

The Plantation of Ulster ( gle, Plandáil Uladh; Ulster-Scots: ''Plantin o Ulstèr'') was the organised colonisation ('' plantation'') of Ulstera province of Irelandby people from Great Britain during the reign of King James I. Most of the se ...

. Although not all unionists were Protestant, loyalists generally emphasized their British Protestant heritage above all else. During the Home Rule Crisis (1912–14), loyalists founded the paramilitary Ulster Volunteers to prevent northeast Ulster from becoming part of a self-governing Ireland. This was followed by the Irish War of Independence

The Irish War of Independence () or Anglo-Irish War was a guerrilla war fought in Ireland from 1919 to 1921 between the Irish Republican Army (1919–1922), Irish Republican Army (IRA, the army of the Irish Republic) and United Kingdom of Gre ...

(1919–21) and partition of Ireland

The partition of Ireland ( ga, críochdheighilt na hÉireann) was the process by which the Government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland divided History of Ireland (1801–1923), Ireland into two self-governing polities: Northe ...

: most of Ireland became an independent state, while 6 counties Ulster counties were portioned off to create Northern Ireland as “a Protestant state for a Protestant people”. During partition, communal violence raged between loyalists and Irish nationalists in Belfast

Belfast ( , ; from ga, Béal Feirste , meaning 'mouth of the sand-bank ford') is the capital and largest city of Northern Ireland, standing on the banks of the River Lagan on the east coast. It is the 12th-largest city in the United Kingd ...

, and loyalists attacked the Catholic minority in retaliation for civil rights demands and other perceived Irish republican

Irish republicanism ( ga, poblachtánachas Éireannach) is the political movement for the unity and independence of Ireland under a republic. Irish republicans view British rule in any part of Ireland as inherently illegitimate.

The develop ...

activity.

Through various arms their state security services, both the United Kingdom and Northern Ireland governments were accused of systemic discrimination, brutality, unlawful detention (frequently involving torture), and the coordinating of assassinations with loyalist death squads who primarily targeted civilian members of the Irish Catholic minority. Over the past 50 years, dozens of in-depth reports have been published by human rights organizations ranging from Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch

Human Rights Watch (HRW) is an international non-governmental organization, headquartered in New York City, that conducts research and advocacy on human rights. The group pressures governments, policy makers, companies, and individual human ...

, the United Nations’ Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, and The European Convention on Human Rights

The European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR; formally the Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms) is an international convention to protect human rights and political freedoms in Europe. Drafted in 1950 by th ...

documenting the systematic abuse of human rights that took place in Northern Ireland following its formal partitioning and annexation into the United Kingdom. Loyalists opposed the Catholic civil rights movement, accusing it of being a republican front. To create an impression that this was the case and to instill fear among the Protestant population, loyalist terrorists under the leadership of Ian Paisley began a bombing campaign intended to manufacture fear of a resurgent IRA. This unrest led to the Troubles

The Troubles ( ga, Na Trioblóidí) were an ethno-nationalist conflict in Northern Ireland that lasted about 30 years from the late 1960s to 1998. Also known internationally as the Northern Ireland conflict, it is sometimes described as an "i ...

(1969–98). During the conflict, loyalist paramilitaries such as the Ulster Volunteer Force

The Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) is an Ulster loyalism, Ulster loyalist paramilitary group. Formed in 1965, it first emerged in 1966. Its first leader was Gusty Spence, a former British Army soldier from Northern Ireland. The group undertook T ...

(UVF) and Ulster Defence Association

The Ulster Defence Association (UDA) is an Ulster loyalist paramilitary group in Northern Ireland. It was formed in September 1971 as an umbrella group for various loyalist groups and undertook an armed campaign of almost 24 years as one of ...

(UDA) often attacked Catholics in response to a loosening of restrictions on the Irish Catholic population as well as community-based terror attacks in retaliation for republican paramilitary actions. Loyalists undertook major protest campaigns against the 1973 Sunningdale Agreement and 1985 Anglo-Irish Agreement. The paramilitaries called ceasefires in 1994 and their representatives were involved in negotiating the 1998 Good Friday Agreement

The Good Friday Agreement (GFA), or Belfast Agreement ( ga, Comhaontú Aoine an Chéasta or ; Ulster-Scots: or ), is a pair of agreements signed on 10 April 1998 that ended most of the violence of The Troubles, a political conflict in Nor ...

. Since the Agreement, loyalists have been involved in protests against perceived threats to their cultural identity. Sections of the loyalist paramilitaries have attacked Catholics, taken part in loyalist feuds, and withdrawn their support for the Agreement, although their campaigns have not resumed.

In Northern Ireland there is a tradition of loyalist Protestant marching bands. There are hundreds of such bands who hold numerous parades each year. The yearly Eleventh Night (11 July) bonfires and The Twelfth (12 July) parades are associated with loyalism.

History

The term ''loyalist'' was first used in Irish politics in the 1790s to refer to Protestants who opposedCatholic Emancipation

Catholic emancipation or Catholic relief was a process in the kingdoms of Great Britain and Ireland, and later the combined United Kingdom in the late 18th century and early 19th century, that involved reducing and removing many of the restrict ...

and Irish independence from Great Britain.

Ulster loyalism emerged in the late 19th century, in response to the Irish Home Rule movement

The Irish Home Rule movement was a movement that campaigned for self-government (or "home rule") for Ireland within the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. It was the dominant political movement of Irish nationalism from 1870 to the ...

and the rise of Irish nationalism

Irish nationalism is a nationalist political movement which, in its broadest sense, asserts that the people of Ireland should govern Ireland as a sovereign state. Since the mid-19th century, Irish nationalism has largely taken the form of cu ...

. At the time, all of Ireland was part of the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the European mainland, continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

. Although the island had a Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwide . It is am ...

majority who wanted self-government, the northeastern portion of the province of Ulster

Ulster (; ga, Ulaidh or ''Cúige Uladh'' ; sco, label=Ulster Scots, Ulstèr or ''Ulster'') is one of the four traditional Irish provinces. It is made up of nine counties: six of these constitute Northern Ireland (a part of the United Kin ...

had a Protestant majority who wanted to maintain Protestant control through a close union with Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* The United Kingdom, a sovereign state in Europe comprising the island of Great Britain, the north-eastern part of the island of Ireland and many smaller islands

* Great Britain, the largest island in the United King ...

, a political tradition called Unionism. This was largely due to the Plantation

''The Plantation'' is the first novel by Chris Kuzneski. First published in 2000, it introduced the characters Jonathon Payne and David Jones, who have been featured in all of Kuzneski's thrillers. The book was endorsed by several notable auth ...

of the province. Eastern Ulster was also more industrialised and dependent on trade with Britain than most other parts of Ireland, where a majority of Irish people had reduced to tenant farming. Although not all Unionists were Protestant or from Ulster, loyalism emphasised what it viewed the superiority of British Protestant heritage above all else.

Home Rule crisis and Partition

The British government's introduction of the Third Home Rule Bill in 1912 sparked the Home Rule Crisis. Ulster unionists signed the Ulster Covenant, pledging to oppose Irish home rule by any means. They founded a large paramilitary force, the Ulster Volunteers, threatening to violently resist the authority of any Irish government over Ulster. The Ulster Volunteers smuggled thousands of rifles and rounds of ammunition into Ulster fromImperial Germany

The German Empire (), Herbert Tuttle wrote in September 1881 that the term "Reich" does not literally connote an empire as has been commonly assumed by English-speaking people. The term literally denotes an empire – particularly a hereditar ...

. In response, Irish nationalists founded the Irish Volunteers

The Irish Volunteers ( ga, Óglaigh na hÉireann), sometimes called the Irish Volunteer Force or Irish Volunteer Army, was a military organisation established in 1913 by Irish nationalists and republicans. It was ostensibly formed in respon ...

to ensure home rule was implemented. Home rule was postponed by the outbreak of the First World War in 1914. Both loyalists and nationalists fought in the war, with many Ulster Volunteers joining the 36th (Ulster) Division.

By the end of the war, most Irish nationalists wanted full independence. After winning most Irish seats in the 1918 general election, Irish republicans declared an Irish Republic

The Irish Republic ( ga, Poblacht na hÉireann or ) was an unrecognised revolutionary state that declared its independence from the United Kingdom in January 1919. The Republic claimed jurisdiction over the whole island of Ireland, but by ...

, leading to the Irish War of Independence

The Irish War of Independence () or Anglo-Irish War was a guerrilla war fought in Ireland from 1919 to 1921 between the Irish Republican Army (1919–1922), Irish Republican Army (IRA, the army of the Irish Republic) and United Kingdom of Gre ...

between the Irish Republican Army

The Irish Republican Army (IRA) is a name used by various paramilitary organisations in Ireland throughout the 20th and 21st centuries. Organisations by this name have been dedicated to irredentism through Irish republicanism, the belief t ...

(IRA) and British forces. Meanwhile, the Fourth Home Rule Bill passed through the British parliament in 1920. It would partition Ireland into two self-governing polities within the UK: a Protestant-majority Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland ( ga, Tuaisceart Éireann ; sco, label=Ulster-Scots, Norlin Airlann) is a part of the United Kingdom, situated in the north-east of the island of Ireland, that is variously described as a country, province or region. North ...

, and a Catholic-majority Southern Ireland. During 1920–22, in what became Northern Ireland, partition was accompanied by violence both in defence of and against partition. Belfast

Belfast ( , ; from ga, Béal Feirste , meaning 'mouth of the sand-bank ford') is the capital and largest city of Northern Ireland, standing on the banks of the River Lagan on the east coast. It is the 12th-largest city in the United Kingd ...

saw "savage and unprecedented" communal violence, mainly between Protestant loyalist and Catholic nationalist civilians. Loyalists attacked the Catholic minority in reprisal for IRA actions. Thousands of Catholics and "disloyal" Protestants were driven from their jobs, and there were mass burnings of Catholic homes and businesses in Lisburn

Lisburn (; ) is a city in Northern Ireland. It is southwest of Belfast city centre, on the River Lagan, which forms the boundary between County Antrim and County Down. First laid out in the 17th century by English and Welsh settlers, with th ...

and Banbridge

Banbridge ( , ) is a town in County Down, Northern Ireland. It lies on the River Bann and the A1 road and is named after a bridge built over the River Bann in 1712. It is situated in the civil parish of Seapatrick and the historic barony of ...

. More than 500 were killed in Northern Ireland during partition and more than 10,000 became refugees, most of them Catholics.

In 1926, about 33.5% of the Northern Ireland population was Roman Catholic, with 62.2% belonging to the three major Protestant denominations (Presbyterian

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their na ...

31.3%, Church of Ireland

The Church of Ireland ( ga, Eaglais na hÉireann, ; sco, label=Ulster-Scots, Kirk o Airlann, ) is a Christian church in Ireland and an autonomous province of the Anglican Communion. It is organised on an all-Ireland basis and is the second l ...

27%, Methodist

Methodism, also called the Methodist movement, is a group of historically related Christian denomination, denominations of Protestantism, Protestant Christianity whose origins, doctrine and practice derive from the life and teachings of John W ...

3.9%).

The Troubles

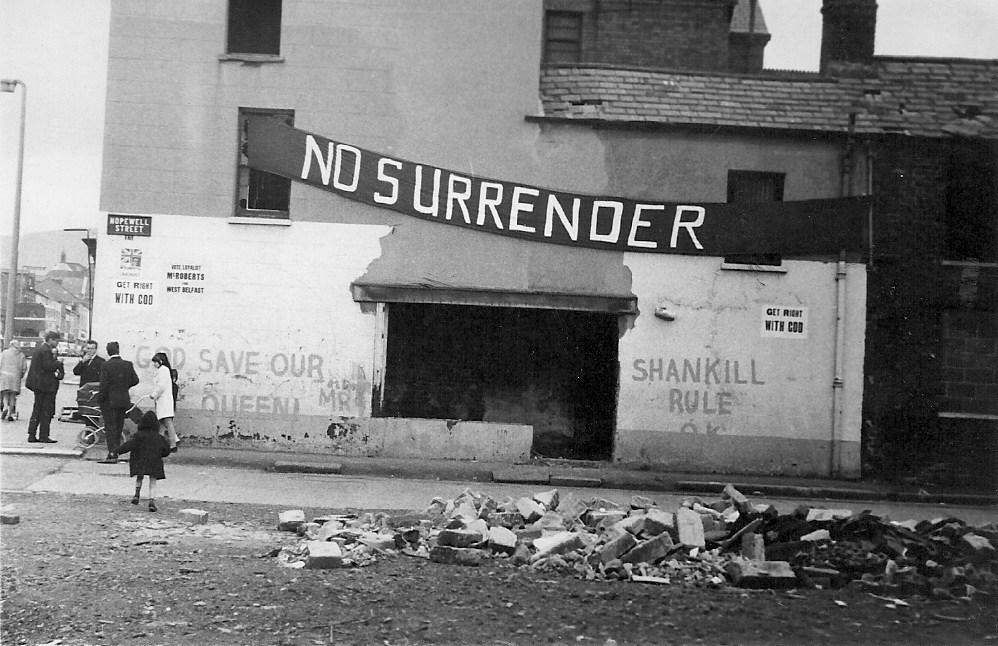

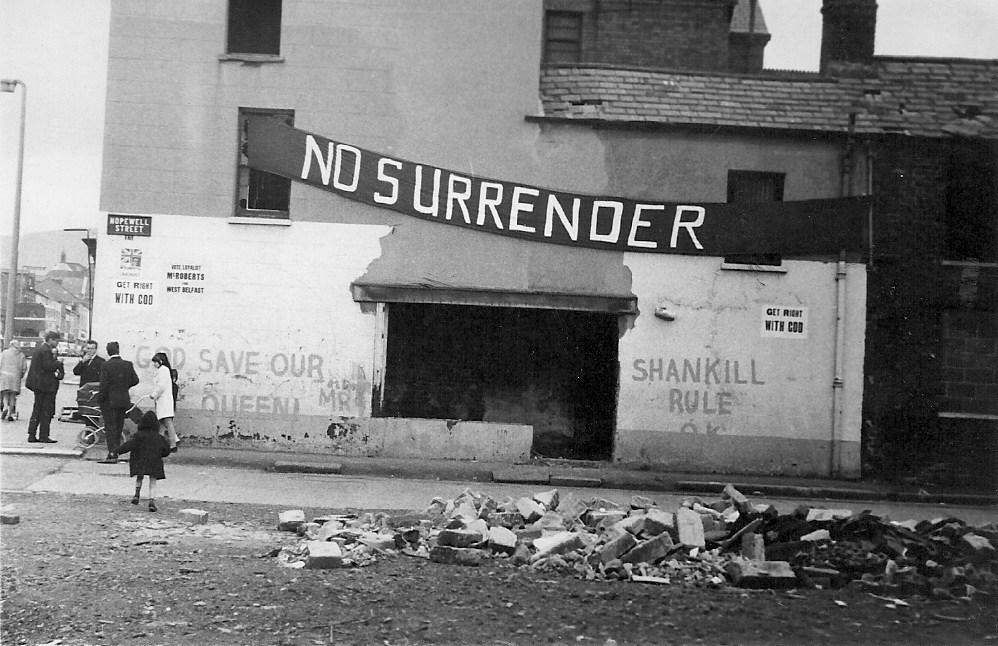

The Unionist governments of Northern Ireland were accused of discrimination against the Irish nationalist and Catholic minority. A non-violent campaign to end discrimination began in the late 1960s. This civil rights campaign was opposed by loyalists, who accused it of being a republican front. Loyalist opposition was led primarily by

The Unionist governments of Northern Ireland were accused of discrimination against the Irish nationalist and Catholic minority. A non-violent campaign to end discrimination began in the late 1960s. This civil rights campaign was opposed by loyalists, who accused it of being a republican front. Loyalist opposition was led primarily by Ian Paisley

Ian Richard Kyle Paisley, Baron Bannside, (6 April 1926 – 12 September 2014) was a Northern Irish loyalist politician and Protestant religious leader who served as leader of the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) from 1971 to 2008 and Firs ...

, a Protestant fundamentalist preacher. They held counter-protests, attacked civil rights marches, and put pressure on moderate unionists. Loyalist militants carried out false flag

A false flag operation is an act committed with the intent of disguising the actual source of responsibility and pinning blame on another party. The term "false flag" originated in the 16th century as an expression meaning an intentional misr ...

bombings that were blamed on republicans and civil rights activists. This unrest led to the August 1969 riots. Irish nationalists/republicans clashed with both police and with loyalists, who burned hundreds of Catholic homes and businesses. The riots led to the deployment of British troops and are often seen as the beginning of the Troubles

The Troubles ( ga, Na Trioblóidí) were an ethno-nationalist conflict in Northern Ireland that lasted about 30 years from the late 1960s to 1998. Also known internationally as the Northern Ireland conflict, it is sometimes described as an "i ...

.

The beginning of the Troubles saw a revival of loyalist paramilitaries, notably the Ulster Volunteer Force

The Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) is an Ulster loyalism, Ulster loyalist paramilitary group. Formed in 1965, it first emerged in 1966. Its first leader was Gusty Spence, a former British Army soldier from Northern Ireland. The group undertook T ...

(UVF) and Ulster Defence Association

The Ulster Defence Association (UDA) is an Ulster loyalist paramilitary group in Northern Ireland. It was formed in September 1971 as an umbrella group for various loyalist groups and undertook an armed campaign of almost 24 years as one of ...

(UDA). Their stated goals were to defend Protestant areas, to fight those they saw as "enemies of Ulster" (namely republicans),Tonge, Jonathan. ''Northern Ireland''. Polity Press, 2006. pp.153, 156–158 and thwart any step towards Irish unification

United Ireland, also referred to as Irish reunification, is the proposition that all of Ireland should be a single sovereign state. At present, the island is divided politically; the sovereign Republic of Ireland has jurisdiction over the maj ...

. The Provisional Irish Republican Army

The Irish Republican Army (IRA; ), also known as the Provisional Irish Republican Army, and informally as the Provos, was an Irish republican paramilitary organisation that sought to end British rule in Northern Ireland, facilitate Irish reuni ...

waged a paramilitary campaign to force a British withdrawal from Northern Ireland. Loyalist paramilitaries attacked the Catholic community as alleged retaliation for IRA actions, and the vast majority of their victims were random Catholic civilians. During the Troubles there were incidents where some local British soldiers and police colluded with loyalist paramilitaries, such as the attacks by the Glenanne group.

Signed in 1973, the Sunningdale Agreement sought to end the conflict by establishing power-sharing government between unionists and Irish nationalists, and ensuring greater co-operation with the Republic of Ireland. In protest, loyalists organized the Ulster Workers' Council strike in May 1974. It was enforced by loyalist paramilitaries and brought large parts of Northern Ireland to a standstill. During the strike, loyalists detonated a series of car bombs in Dublin and Monaghan, in the Republic. This killed 34 civilians, making it the deadliest attack of the Troubles. The strike brought down the agreement and power-sharing government.

Loyalists were involved in the major protest campaign against the 1985 Anglo-Irish Agreement. They saw it as a breach of sovereignty, because it gave the Republic an advisory role in some Northern Ireland affairs. The many street protests led to loyalist clashes with the Royal Ulster Constabulary

The Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) was the police force in Northern Ireland from 1922 to 2001. It was founded on 1 June 1922 as a successor to the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) Richard Doherty, ''The Thin Green Line – The History of the Roy ...

(RUC), whom loyalists accused of enforcing the Agreement and betraying the Protestant community. This caused a rift between loyalists and the police, and there were numerous loyalist attacks on police officers' homes during the protests.

From the late 1980s, there was a rise in loyalist paramilitary violence, partly due to anger over the Anglo-Irish Agreement. It also resulted from loyalist groups being re-armed with weapons smuggled from South Africa, overseen by British Intelligence agent Brian Nelson. From 1992 to 1994, loyalists carried out more killings than republicans. The deadliest attacks during this period were the Greysteel massacre

The Greysteel massacreCrawford, Colin. ''Inside the UDA''. Pluto Press, 2003. p. 193 was a mass shooting that took place on the evening of 30 October 1993 in Greysteel, County Londonderry, Northern Ireland. Members of the Ulster Defence Associa ...

by the UDA and Loughinisland massacre by the UVF.

The main loyalist paramilitary groups called a ceasefire in 1994, shortly after the Provisional IRA's ceasefire and beginning of the Northern Ireland peace process

The Northern Ireland peace process includes the events leading up to the 1994 Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) ceasefire, the end of most of the violence of the Troubles, the Good Friday Agreement of 1998, and subsequent political developm ...

. This ceasefire came under strain during the Drumcree dispute of the mid-to-late 1990s. The Protestant Orange Order

The Loyal Orange Institution, commonly known as the Orange Order, is an international Protestant fraternal order based in Northern Ireland and primarily associated with Ulster Protestants, particularly those of Ulster Scots people, Ulster Sco ...

was blocked from marching its traditional route through the Catholic part of Portadown

Portadown () is a town in County Armagh, Northern Ireland. The town sits on the River Bann in the north of the county, about southwest of Belfast. It is in the Armagh City, Banbridge and Craigavon Borough Council area and had a population of a ...

. Catholic residents held mass protests against the yearly march, seeing it as triumphalist and supremacist

Supremacism is the belief that a certain group of people is superior to all others. The supposed superior people can be defined by age, gender, race, ethnicity, religion, sexual orientation, language, social class, ideology, nation, culture, ...

, forcing police to halt the march.Kockel, Ullrich. ''Re-Visioning Europe:Frontiers, Place Identities and Journeys in Debatable Lands''. Springer Publishing, 2020. pp.16–20 Loyalists saw this as an assault on Ulster Protestant traditions, and held violent protests throughout Northern Ireland. In Portadown, thousands of loyalists attacked lines of police and soldiers guarding the Catholic district. A new UVF splinter group, the Loyalist Volunteer Force (LVF), attacked Catholics over a two-year period before calling a ceasefire.

After the Good Friday Agreement

Loyalist representatives had helped negotiate the

Loyalist representatives had helped negotiate the Good Friday Agreement

The Good Friday Agreement (GFA), or Belfast Agreement ( ga, Comhaontú Aoine an Chéasta or ; Ulster-Scots: or ), is a pair of agreements signed on 10 April 1998 that ended most of the violence of The Troubles, a political conflict in Nor ...

of 1998, and it was backed by the UVF-linked Progressive Unionist Party

The Progressive Unionist Party (PUP) is a minor unionist political party in Northern Ireland. It was formed from the Independent Unionist Group operating in the Shankill area of Belfast, becoming the PUP in 1979. Linked to the Ulster Volunt ...

and UDA-linked Ulster Democratic Party. However, wider loyalist support for the Agreement was tenuous from the outset,Gillespie, Gordon. "Noises off: Loyalists after the Agreement", in ''A Farewell to Arms?: Beyond the Good Friday Agreement''. Manchester University Press, 2006. pp.139–142 and these parties received many fewer votes than the main unionist parties: the pro-Agreement UUP and anti-Agreement DUP.

Since the Agreement, loyalist paramilitaries have been involved in riots, feuds between loyalist groups, organized crime, vigilantism such as punishment shootings, and racist attacks. Some UDA and LVF brigades broke the ceasefire and attacked Catholics under the name Red Hand Defenders, but the paramilitary campaigns did not resume.

The 2001 Holy Cross protests drew world-wide condemnation as loyalists were shown hurling abuse and missiles, some explosive, others containing excrement, at very young Catholic schoolchildren and parents. Loyalist residents picketed the school in protest at alleged sectarianism from Catholics in the area. Many other loyalist protests and riots have been sparked by restrictions on Orange marches, such as the 2005 Whiterock riots. The widespread loyalist flag protests and riots of 2012–13 followed Belfast City Council voting to limit the flying of the Union Flag from council buildings. Loyalists saw it as an "attack on their cultural identity".

The Loyalist Communities Council was launched in 2015 with the backing of the UVF and UDA. It seeks to reverse what it sees as political and economic neglect of working-class loyalists since the Good Friday Agreement. In 2021, it withdrew its support for the Agreement, due to the creation of a trade border between Northern Ireland and Britain as a result of Brexit

Brexit (; a portmanteau of "British exit") was the withdrawal of the United Kingdom (UK) from the European Union (EU) at 23:00 GMT on 31 January 2020 (00:00 1 February 2020 CET).The UK also left the European Atomic Energy Community (EAE ...

. The fall-out over this partly fuelled loyalist rioting that Spring.

Political parties

Active parties

*Democratic Unionist Party

The Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) is a unionist, loyalist, and national conservative political party in Northern Ireland. It was founded in 1971 during the Troubles by Ian Paisley, who led the party for the next 37 years. Currently led by ...

(DUP), the second-largest party in the Northern Ireland Assembly

sco-ulster, Norlin Airlan Assemblie

, legislature = Seventh Assembly

, coa_pic = File:NI_Assembly.svg

, coa_res = 250px

, house_type = Unicameral

, house1 =

, leader1_type = ...

* Traditional Unionist Voice

The Traditional Unionist Voice (TUV) is a unionist political party in Northern Ireland. In common with all other Northern Irish unionist parties, the TUV's political programme has as its sine qua non the preservation of Northern Ireland's place ...

(TUV)

* Progressive Unionist Party

The Progressive Unionist Party (PUP) is a minor unionist political party in Northern Ireland. It was formed from the Independent Unionist Group operating in the Shankill area of Belfast, becoming the PUP in 1979. Linked to the Ulster Volunt ...

(PUP), which is linked to the Ulster Volunteer Force

The Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) is an Ulster loyalism, Ulster loyalist paramilitary group. Formed in 1965, it first emerged in 1966. Its first leader was Gusty Spence, a former British Army soldier from Northern Ireland. The group undertook T ...

(UVF) and Red Hand Commando

The Red Hand Commando (RHC) is a small Ulster loyalist paramilitary group in Northern Ireland that is closely linked to the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF). Its aim was to combat Irish republicanism – particularly the Irish Republican Army (IR ...

(RHC)

Former parties

*Protestant Coalition

The Protestant Coalition was an Ulster loyalist political party in Northern Ireland. It was registered on 23 April 2013,Register of political parties aElectoral Commissionwebsite and launched on 24 April at a hotel in Castlereagh, outside Bel ...

(2013-2015)

* Ulster Democratic Party (1981–2001)

* Ulster Vanguard (1972–1978)

* Volunteer Political Party (1974)

* Ulster Protestant League (1930s)

Paramilitary and vigilante groups

Loyalist paramilitary and vigilante groups have been active since the early 20th century. In 1912, the Ulster Volunteers were formed to stop the British Government granting self-rule to Ireland, or to exclude Ulster from it. This led to the Home Rule Crisis, which was defused by the onset of

Loyalist paramilitary and vigilante groups have been active since the early 20th century. In 1912, the Ulster Volunteers were formed to stop the British Government granting self-rule to Ireland, or to exclude Ulster from it. This led to the Home Rule Crisis, which was defused by the onset of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

. Loyalist paramilitaries were again active in Ulster during the Irish War of Independence

The Irish War of Independence () or Anglo-Irish War was a guerrilla war fought in Ireland from 1919 to 1921 between the Irish Republican Army (1919–1922), Irish Republican Army (IRA, the army of the Irish Republic) and United Kingdom of Gre ...

(1919–22), and more prominently during the Troubles

The Troubles ( ga, Na Trioblóidí) were an ethno-nationalist conflict in Northern Ireland that lasted about 30 years from the late 1960s to 1998. Also known internationally as the Northern Ireland conflict, it is sometimes described as an "i ...

(late 1960s–1998). The biggest and most active paramilitary groups existed during the Troubles, and were the Ulster Volunteer Force

The Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) is an Ulster loyalism, Ulster loyalist paramilitary group. Formed in 1965, it first emerged in 1966. Its first leader was Gusty Spence, a former British Army soldier from Northern Ireland. The group undertook T ...

(UVF), and the Ulster Defence Association

The Ulster Defence Association (UDA) is an Ulster loyalist paramilitary group in Northern Ireland. It was formed in September 1971 as an umbrella group for various loyalist groups and undertook an armed campaign of almost 24 years as one of ...

(UDA)/Ulster Freedom Fighters (UFF). They, and most other loyalist paramilitaries, are classified as terrorist organisations.

During the Troubles, their stated goals were to combat Irish republicanism

Irish republicanism ( ga, poblachtánachas Éireannach) is the political movement for the unity and independence of Ireland under a republic. Irish republicans view British rule in any part of Ireland as inherently illegitimate.

The develo ...

– particularly the Provisional Irish Republican Army

The Irish Republican Army (IRA; ), also known as the Provisional Irish Republican Army, and informally as the Provos, was an Irish republican paramilitary organisation that sought to end British rule in Northern Ireland, facilitate Irish reuni ...

(IRA) – and to defend Protestant loyalist areas.Doherty, Barry. ''Northern Ireland since c.1960''. Heinemann, 2001. p15 However, the vast majority of their victims were Irish Catholic

Irish Catholics are an ethnoreligious group native to Ireland whose members are both Catholic and Irish. They have a large diaspora, which includes over 36 million American citizens and over 14 million British citizens (a quarter of the Briti ...

civilians, who were often killed at random in sectarian

Sectarianism is a political or cultural conflict between two groups which are often related to the form of government which they live under. Prejudice, discrimination, or hatred can arise in these conflicts, depending on the political status quo ...

attacks. Whenever they claimed responsibility for attacks, loyalists usually claimed that those targeted were IRA members or were helping the IRA. M. L. R. Smith wrote that "From the outset, the loyalist paramilitaries tended to regard all Catholics as potential rebels".Smith, M L R. ''Fighting for Ireland?''. Psychology Press, 1997. p.118 Other times, attacks on Catholic civilians were claimed as "retaliation" for IRA actions, since the IRA drew most of its support from the Catholic community.Tonge, Jonathan. ''Northern Ireland''. Polity, 2006. p.157 Such retaliation was seen as both collective punishment and an attempt to weaken the IRA's support; some loyalists argued that terrorising the Catholic community and inflicting a high death toll on it would eventually force the IRA to end its campaign. According to then Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is ...

Tony Blair

Sir Anthony Charles Lynton Blair (born 6 May 1953) is a British former politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1997 to 2007 and Leader of the Labour Party from 1994 to 2007. He previously served as Leader of the ...

, "The purpose of loyalist terrorism was to retaliate, to dominate or to clear out Catholics." An editorial in the UVF's official magazine ''Combat'' explained in 1993:

Loyalist paramilitaries were responsible for 29% of all deaths in the Troubles, and were responsible for about 48% of all civilian deaths. Loyalist paramilitaries killed civilians at far higher rates than both Republican paramilitaries and British security forces.

The ''modus operandi

A ''modus operandi'' (often shortened to M.O.) is someone's habits of working, particularly in the context of business or criminal investigations, but also more generally. It is a Latin phrase, approximately translated as "mode (or manner) of o ...

'' of loyalist paramilitaries involved assassinations, mass shootings, bombings and kidnappings. They used sub machine-guns, assault rifles, pistol

A pistol is a handgun, more specifically one with the chamber integral to its gun barrel, though in common usage the two terms are often used interchangeably. The English word was introduced in , when early handguns were produced in Europe, ...

s, grenade

A grenade is an explosive weapon typically thrown by hand (also called hand grenade), but can also refer to a shell (explosive projectile) shot from the muzzle of a rifle (as a rifle grenade) or a grenade launcher. A modern hand grenade g ...

s (including homemade grenades), incendiary bomb

Incendiary weapons, incendiary devices, incendiary munitions, or incendiary bombs are weapons designed to start fires or destroy sensitive equipment using fire (and sometimes used as anti-personnel weaponry), that use materials such as napalm, ...

s, booby trap

A booby trap is a device or setup that is intended to kill, harm or surprise a human or another animal. It is triggered by the presence or actions of the victim and sometimes has some form of bait designed to lure the victim towards it. The trap m ...

bombs and car bombs. Bomb attacks were usually made without warning. However, gun attacks were more common than bombings. In January 1994, the UDA drew up a 'doomsday plan', to be implemented should the British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gur ...

withdraw from Northern Ireland. It called for ethnic cleansing

Ethnic cleansing is the systematic forced removal of ethnic, racial, and religious groups from a given area, with the intent of making a region ethnically homogeneous. Along with direct removal, extermination, deportation or population trans ...

and re-partition, with the goal of making Northern Ireland wholly Protestant.Wood, Ian S. ''Crimes of Loyalty: A History of the UDA''. Edinburgh University Press, 2006. pp.184–185.

Some loyalist paramilitaries have had links with far-right

Far-right politics, also referred to as the extreme right or right-wing extremism, are political beliefs and actions further to the right of the left–right political spectrum than the standard political right, particularly in terms of bein ...

and Neo-Nazi

Neo-Nazism comprises the post–World War II militant, social, and political movements that seek to revive and reinstate Nazi ideology. Neo-Nazis employ their ideology to promote hatred and racial supremacy (often white supremacy), attack r ...

groups in Britain, including Combat 18, the British National Socialist Movement, and the National Front. Since the 1990s, loyalist paramilitaries have been responsible for numerous racist attacks in loyalist areas. A 2006 report revealed that 90% of racist attacks in the previous two years occurred in mainly loyalist areas.

In the 1990s, the main loyalist paramilitaries called ceasefire

A ceasefire (also known as a truce or armistice), also spelled cease fire (the antonym of 'open fire'), is a temporary stoppage of a war in which each side agrees with the other to suspend aggressive actions. Ceasefires may be between state ac ...

s. Following this, small breakaway groups continued to wage violent campaigns for a number of years, and members of loyalist groups have continued to engage in sporadic violence.

Fraternities and marching bands

Orange Order

The Loyal Orange Institution, commonly known as the Orange Order, is an international Protestant fraternal order based in Northern Ireland and primarily associated with Ulster Protestants, particularly those of Ulster Scots people, Ulster Sco ...

and Apprentice Boys of Derry. These fraternities, often described as the "Loyal Orders", have long been associated with unionism/loyalism. Yearly events such as the Eleventh Night (11 July) bonfires and The Twelfth (12 July) parades are strongly associated with loyalism. A report published in 2013 estimated there were at least 640 marching bands in Northern Ireland with a total membership of around 30,000, an all-time high. According to the Parades Commission, a total of 1,354 loyalist parades (not counting funerals) were held in Northern Ireland in 2007. The Police Service of Northern Ireland

The Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI; ga, Seirbhís Póilíneachta Thuaisceart Éireann; Ulster-Scots: ')

is the police force that serves Northern Ireland. It is the successor to the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) after it was reform ...

uses different statistics, and recorded a total of 2,863 parades in 2007. Of these, 2,270 (approximately 80%) were held by loyalist marching bands.

Other groups

* Third Force * Loyalist Association of Workers * Ulster Workers' Council * Ulster Political Research Group * Tara (Northern Ireland) *Glenanne gang

The Glenanne gang or Glenanne group was a secret informal alliance of Ulster loyalists who carried out shooting and bombing attacks against Catholics and Irish nationalists in the 1970s, during the Troubles.

* Shankill Butchers

* Orange Volunteers

* Orange Volunteers (1972)

* Ulster Resistance

* Ulster Special Constabulary Association

The Ulster Special Constabulary Association (USCA) was a loyalist group active in Northern Ireland during the early 1970s.

The group was established following the dissolution of the Ulster Special Constabulary (commonly known as the B Specials) a ...

* Down Orange Welfare

* Ulster Protestant Volunteers

References

Bibliography

* Potter, John Furniss. ''A Testimony to Courage – the Regimental History of the Ulster Defence Regiment 1969 – 1992'', Pen & Sword Books Ltd, 2001, * Ryder, Chris. ''The Ulster Defence Regiment: An Instrument of Peace?'', 1991External links

Progressive Unionist Party

{{Ethnic nationalism Ethnicity in politics Identity politics Loyalist Religious nationalism The Troubles (Northern Ireland)