USS Thresher (SSN-593) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

USS ''Thresher'' (SSN-593) was the

Created to find and destroy Soviet submarines, ''Thresher'' was the fastest and quietest submarine of its day, matching the smaller, contemporary . She also had the most advanced weapons system, including launchers for the U.S. Navy's newest

Created to find and destroy Soviet submarines, ''Thresher'' was the fastest and quietest submarine of its day, matching the smaller, contemporary . She also had the most advanced weapons system, including launchers for the U.S. Navy's newest

The contract to build ''Thresher'' was awarded to

The contract to build ''Thresher'' was awarded to

The Navy quickly mounted an extensive search with surface ships and support from the

The Navy quickly mounted an extensive search with surface ships and support from the

During the 1963 inquiry, Admiral Hyman Rickover stated:

During the 1963 inquiry, Admiral Hyman Rickover stated:

Loss of USS ''Thresher''

* * First published 1964; reissued in 2001 by Lyons Press (Guilford, Conn) as ''The Death of the USS Thresher'' * *

McCoole's statement re: shutting main steam valves during reactor scram

*

On Eternal Patrol: USS ''Thresher''

USS Thresher 593

Thresher Base United States Submarine Veterans

Memorial Video on YouTube

{{DEFAULTSORT:Thresher (Ssn-593) 1960 ships 1963 in the United States Cold War submarines of the United States Lost submarines of the United States Maritime incidents in 1963 Thresher, USS Permit-class submarines Ships built in Kittery, Maine Warships lost with all hands Thresher, USS Sunken nuclear submarines United States submarine accidents

lead boat

The lead ship, name ship, or class leader is the first of a series or class of ships all constructed according to the same general design. The term is applicable to naval ships and large civilian vessels.

Large ships are very complex and may ...

of her class of nuclear-powered attack submarines in the United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

. She was the U.S. Navy's second submarine to be named after the thresher shark

Thresher sharks are large lamniform sharks of the family Alopiidae found in all temperate and tropical oceans of the world; the family contains three extant species, all within the genus ''Alopias''.

All three thresher shark species have been ...

.

On 10 April 1963, ''Thresher'' sank during deep-diving tests about east of Cape Cod, Massachusetts, killing all 129 crew and shipyard personnel aboard. It is the second-deadliest submarine incident on record, after the 1942 loss of the French submarine ''Surcouf'', in which 130 crew died. Her loss was a watershed for the U.S. Navy, leading to the implementation of a rigorous submarine safety program known as SUBSAFE. The first nuclear submarine lost at sea, ''Thresher'' was also the third of four submarines lost with more than 100 people aboard, the others being ''Argonaut'', lost with 102 aboard in 1943, '' Surcouf'' sinking with 130 personnel in 1942, and ''Kursk

Kursk ( rus, Курск, p=ˈkursk) is a city and the administrative center of Kursk Oblast, Russia, located at the confluence of the Kur, Tuskar, and Seym rivers. The area around Kursk was the site of a turning point in the Soviet–German str ...

'', which sank with 118 aboard in 2000.

Significance of design and loss

Created to find and destroy Soviet submarines, ''Thresher'' was the fastest and quietest submarine of its day, matching the smaller, contemporary . She also had the most advanced weapons system, including launchers for the U.S. Navy's newest

Created to find and destroy Soviet submarines, ''Thresher'' was the fastest and quietest submarine of its day, matching the smaller, contemporary . She also had the most advanced weapons system, including launchers for the U.S. Navy's newest anti-submarine missile An anti-submarine missile is a standoff anti-submarine weapon. Often a variant of anti-ship missile designs, an anti-submarine systems typically use a jet or rocket engine, to deliver an explosive warhead aimed directly at a submarine, a depth c ...

, the SUBROC

The UUM-44 SUBROC (SUBmarine ROCket) was a type of submarine-launched rocket deployed by the United States Navy as an anti-submarine weapon. It carried a 250 kiloton thermonuclear warhead configured as a nuclear depth bomb.

Development

SUBR ...

, as well as passive and active sonar that could detect vessels at unprecedented range. Shortly after her loss, the Commander of Submarine Force Atlantic wrote in the March 1964 issue of the U.S. Naval Institute's monthly journal ''Proceedings'' that "the Navy had depended upon this performance to the extent that it had asked for and received authority to build 14 of these ships, as well as an additional 11 submarines with very much the same characteristics. This was the first time since World War II that we had considered our design sufficiently advanced to embark upon construction of a large class of general-purpose attack submarines."

Following Navy tradition, this class of subs was originally named ''Thresher'' after the lead boat. When ''Thresher'' was struck from the Naval Vessel Register

The ''Naval Vessel Register'' (NVR) is the official inventory of ships and service craft in custody of or titled by the United States Navy. It contains information on ships and service craft that make up the official inventory of the Navy from t ...

on 16 April 1963, the class name was changed to that of the second boat, , and ''Thresher'' is now officially referred to as a ''Permit''-class submarine. Having been lost at sea, ''Thresher'' was not decommissioned by the U.S. Navy and remains on "Eternal Patrol".

Early career

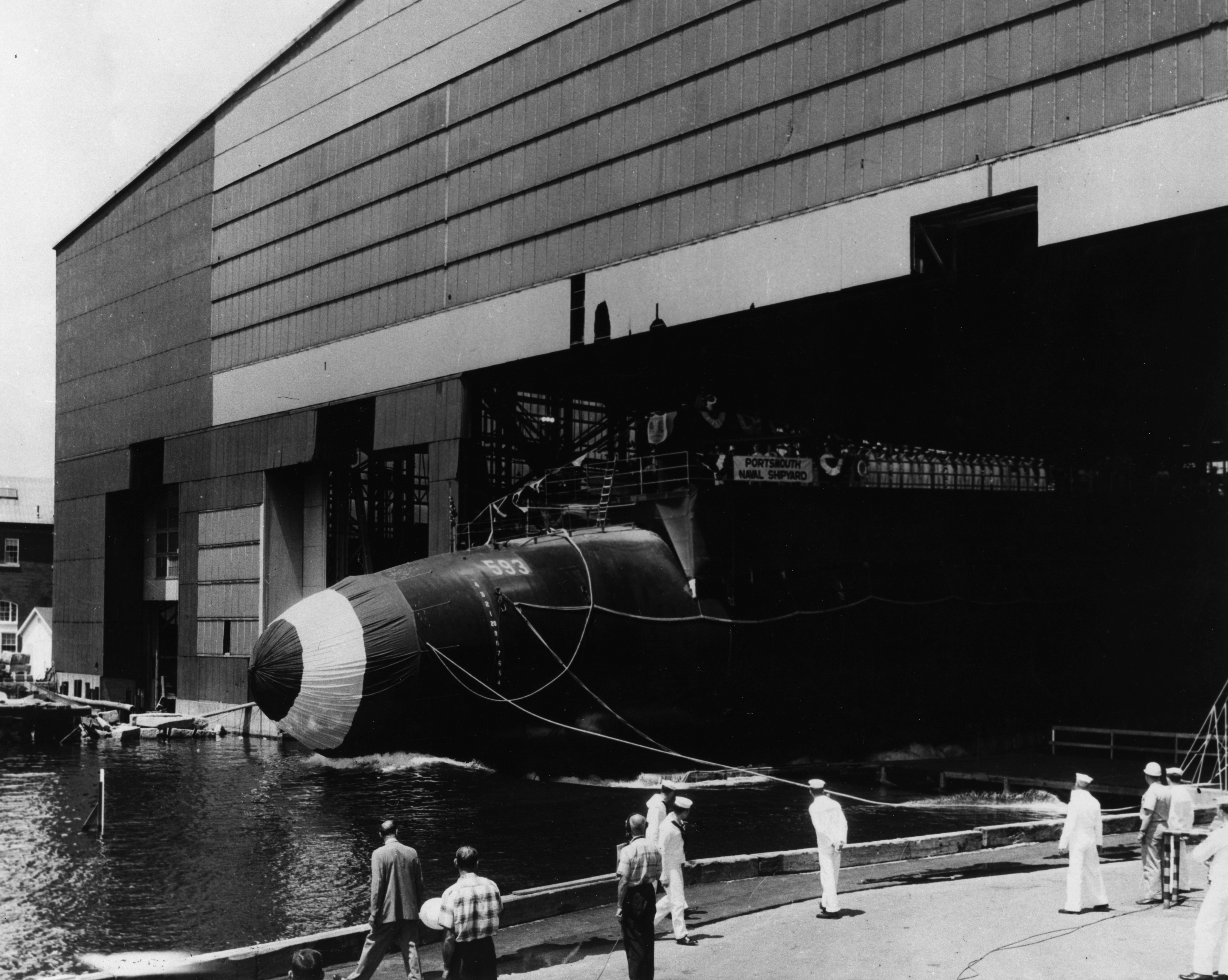

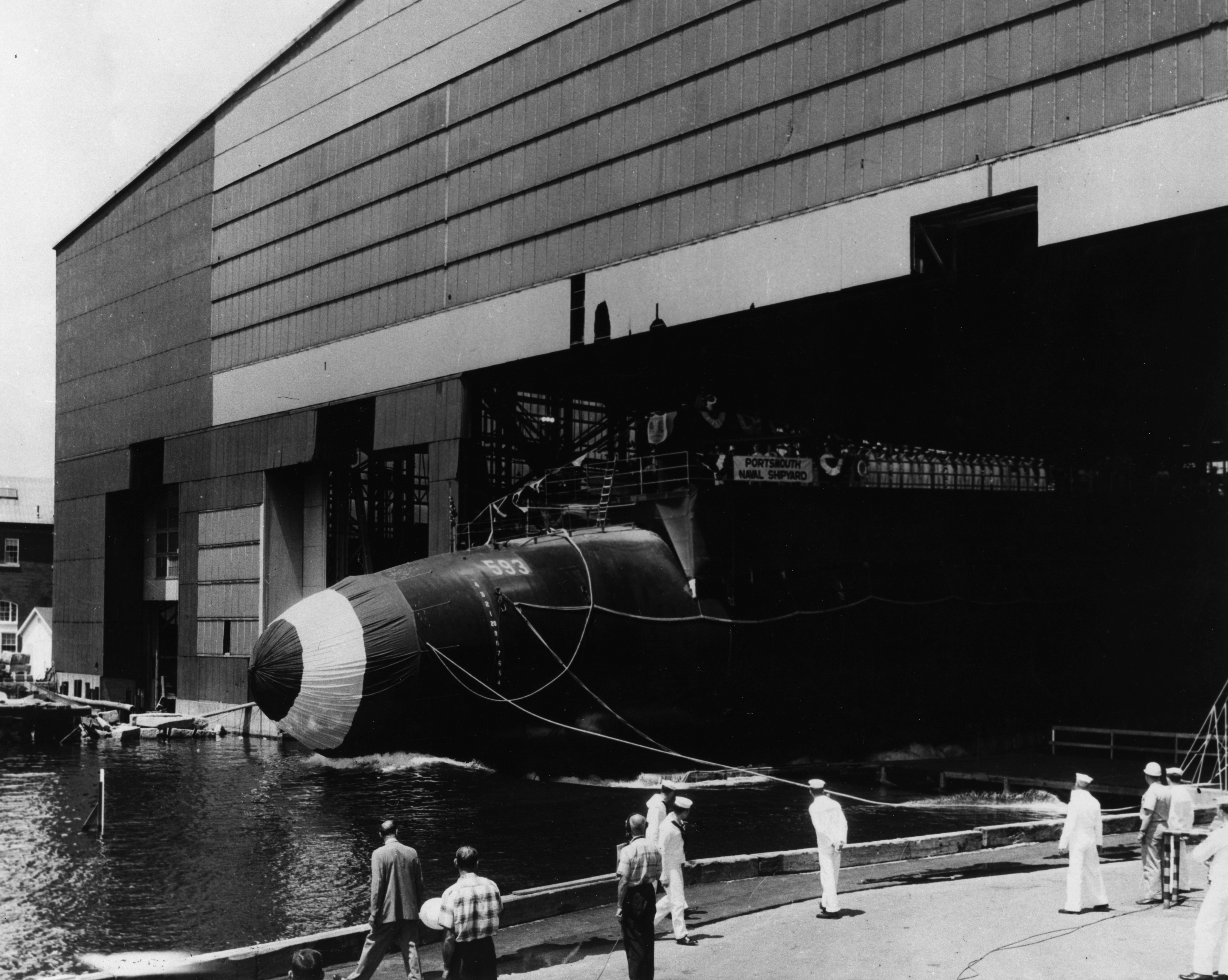

The contract to build ''Thresher'' was awarded to

The contract to build ''Thresher'' was awarded to Portsmouth Naval Shipyard

The Portsmouth Naval Shipyard, often called the Portsmouth Navy Yard, is a United States Navy shipyard in Kittery on the southern boundary of Maine near the city of Portsmouth, New Hampshire.

Founded in 1800, PNS is U.S. Navy's oldest continu ...

on 15 January 1958, and her keel

The keel is the bottom-most longitudinal structural element on a vessel. On some sailboats, it may have a hydrodynamic and counterbalancing purpose, as well. As the laying down of the keel is the initial step in the construction of a ship, in B ...

was laid on 28 May 1958. She was launched bow first on 9 July 1960, was sponsored by Mary B. Warder (wife of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

skipper Frederick B. Warder

Frederick Burdett Warder (March 19, 1904 – February 1, 2000) was a highly decorated United States Navy submarine officer during World War II. He was a two time recipient of the Navy Cross for extraordinary heroism in combat, and a four tim ...

), and was commissioned on 3 August 1961, Commander

Commander (commonly abbreviated as Cmdr.) is a common naval officer rank. Commander is also used as a rank or title in other formal organizations, including several police forces. In several countries this naval rank is termed frigate captain ...

Dean L. Axene commanding.

''Thresher'' conducted lengthy sea trials in the western Atlantic and Caribbean Sea

The Caribbean Sea ( es, Mar Caribe; french: Mer des Caraïbes; ht, Lanmè Karayib; jam, Kiaribiyan Sii; nl, Caraïbische Zee; pap, Laman Karibe) is a sea of the Atlantic Ocean in the tropics of the Western Hemisphere. It is bounded by Mexico ...

areas in 1961–1962. These tests allowed a thorough evaluation of her many new and complex technological features and weapons. She took part in Nuclear Submarine Exercise (NUSUBEX) 3–61 off the northeastern coast of the United States from 18–24 September 1961.

On 18 October 1961, ''Thresher,'' in company with the diesel-electric submarine , headed south on a three-week test and training cruise to San Juan, Puerto Rico

San Juan (, , ; Spanish for "Saint John") is the capital city and most populous municipality in the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, an unincorporated territory of the United States. As of the 2020 census, it is the 57th-largest city under the ju ...

, arriving 2 November. Following customary procedure while in port, her reactor was shut down. Since no shore power connection was available in San Juan, the ship's backup diesel generator

A diesel generator (DG) (also known as a diesel Genset) is the combination of a diesel engine with an electric generator (often an alternator) to generate electrical energy. This is a specific case of engine generator. A diesel compression-i ...

was used to carry the "hotel" electrical loads. Several hours later, the backup generator broke down and the electrical load was transferred to the ship's battery. As most of the battery power was needed to keep vital systems operating and to restart the reactor, lighting and air conditioning were shut down. Without air conditioning, temperature and humidity in the submarine rose, reaching after about 10 hours. The crew attempted to repair the diesel generator (four men would receive Navy commendation medals for their work that night). After it became apparent that the generator could not be fixed before the battery was depleted, the crew tried to restart the reactor, but the remaining battery charge was insufficient. The captain, returning to the ship from a shore function, arrived just after the battery ran down. The crew eventually borrowed cables from another ship in the harbor and connected them to the adjacent ''Cavalla'', which started her diesels and provided enough power to allow ''Thresher'' to restart her reactor.

''Thresher'' conducted further trials and fired test torpedo

A modern torpedo is an underwater ranged weapon launched above or below the water surface, self-propelled towards a target, and with an explosive warhead designed to detonate either on contact with or in proximity to the target. Historically, s ...

es before returning to Portsmouth on 29 November 1961. The boat remained in port through the end of the year, and spent the first two months of 1962 with her sonar

Sonar (sound navigation and ranging or sonic navigation and ranging) is a technique that uses sound propagation (usually underwater, as in submarine navigation) to navigate, measure distances ( ranging), communicate with or detect objects on ...

and SUBROC systems under evaluation. In March, she participated in NUSUBEX 2–62 (an exercise designed to improve the tactical capabilities of nuclear submarines) and in anti-submarine warfare

Anti-submarine warfare (ASW, or in older form A/S) is a branch of underwater warfare that uses surface warships, aircraft, submarines, or other platforms, to find, track, and deter, damage, or destroy enemy submarines. Such operations are typi ...

training with Task Group ALPHA.

Off Charleston, South Carolina, ''Thresher'' undertook operations supporting development of the SUBROC anti-submarine missile. She returned briefly to New England

New England is a region comprising six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York to the west and by the Canadian province ...

waters, after which she proceeded to Florida for more SUBROC tests. While moored at Port Canaveral, Florida

Port Canaveral is a cruise, cargo, and naval port in Brevard County, Florida, United States. It is one of the busiest cruise ports in the world with 4.5 million cruise passengers passing through during 2016. Over 5.4 million tonnes of bulk car ...

, the submarine was accidentally struck by a tug, which damaged one of her ballast tanks

A ballast tank is a compartment within a boat, ship or other floating structure that holds water, which is used as ballast to provide hydrostatic stability for a vessel, to reduce or control buoyancy, as in a submarine, to correct trim or list ...

. After repairs at Groton, Connecticut

Groton is a town in New London County, Connecticut located on the Thames River. It is the home of General Dynamics Electric Boat, which is the major contractor for submarine work for the United States Navy. The Naval Submarine Base New London ...

by the Electric Boat

An electric boat is a powered watercraft driven by electric motors, which are powered by either on-board battery packs, solar panels or generators.

While a significant majority of water vessels are powered by diesel engines, with sail po ...

Company, ''Thresher'' went south for more tests and trials off Key West, Florida, then returned northward. The submarine entered Portsmouth Shipyard on 16 July 1962 to begin a scheduled six-month post-shakedown availability to examine systems and make repairs and corrections as necessary. As is typical with a first-of-class boat, the work took longer than expected, lasting nearly nine months. The ship was finally recertified and undocked on 8 April 1963.

Sinking

On 9 April 1963, ''Thresher'', commanded byLieutenant Commander

Lieutenant commander (also hyphenated lieutenant-commander and abbreviated Lt Cdr, LtCdr. or LCDR) is a commissioned officer rank in many navies. The rank is superior to a lieutenant and subordinate to a commander. The corresponding rank i ...

John Wesley Harvey, left from Kittery, Maine

Kittery is a town in York County, Maine, United States. Home to the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard on Seavey's Island, Kittery includes Badger's Island, the seaside district of Kittery Point, and part of the Isles of Shoals. The southernmost tow ...

, at 8:00 a.m. and met with the submarine rescue ship at 11:00 a.m. to begin her initial post-overhaul dive trials, in an area some east of Cape Cod, Massachusetts

Cape Cod is a peninsula extending into the Atlantic Ocean from the southeastern corner of mainland Massachusetts, in the northeastern United States. Its historic, maritime character and ample beaches attract heavy tourism during the summer mont ...

. That afternoon, ''Thresher'' conducted an initial trim-dive test, surfaced, and then performed a second dive to half of her 1,300-foot test depth. She remained submerged overnight and re-established underwater communications with ''Skylark'' at 6:30 a.m. on 10 April to commence deep-dive trials. Following standard practice, ''Thresher'' slowly dove deeper as she traveled in circles under ''Skylark'' – to remain within communications distance – pausing every of depth to check the integrity of all systems. As ''Thresher'' neared her test depth, ''Skylark'' received garbled communications over underwater telephone indicating " ... minor difficulties, have positive up-angle, attempting to blow," and then a final, even more garbled message that included the number "900". When ''Skylark'' received no further communication, surface observers gradually realized ''Thresher'' had sunk.

By mid-afternoon, 15 Navy ships were en route to the search area. At 6:30 p.m., the commander of Submarine Force Atlantic sent word to Portsmouth Naval Shipyard to begin notifying the crew's family members, starting with Commander Harvey's wife Irene, that ''Thresher'' was missing.

Chief of Naval Operations Admiral George W. Anderson Jr.

George Whelan Anderson Jr. (December 15, 1906 – March 20, 1992) was an admiral in the United States Navy and a diplomat. Serving as the Chief of Naval Operations between 1961 and 1963, he was in charge of the US blockade of Cuba during the 1962 ...

went before the press corps at the Pentagon

The Pentagon is the headquarters building of the United States Department of Defense. It was constructed on an accelerated schedule during World War II. As a symbol of the U.S. military, the phrase ''The Pentagon'' is often used as a metonym ...

to announce that the submarine was lost with all hands. President John F. Kennedy ordered all flags to be flown at half staff from 12 to 15 April in honor of the 129 lost submariners and shipyard personnel.

Search and recovery

The Navy quickly mounted an extensive search with surface ships and support from the

The Navy quickly mounted an extensive search with surface ships and support from the Naval Research Laboratory

The United States Naval Research Laboratory (NRL) is the corporate research laboratory for the United States Navy and the United States Marine Corps. It was founded in 1923 and conducts basic scientific research, applied research, technological ...

(NRL), with its deep-search capability. The laboratory's small acoustic research vessel ''Rockville'', with a unique trainable search sonar, left on 12 April 1963 for the search area. ''Rockville'' was to be followed by other personnel with a deep-camera system. , , and became engaged in a close sonar search of an area square. , , and investigated likely contacts found in the sonar search. The NRL deep-towed camera system and personnel later operated from ''James M. Gilliss'' with some success, finding debris later confirmed to be from ''Thresher''. The bathyscaphe ''Trieste'' was alerted on 11 April and brought from San Diego to Boston. It was deployed for two series of dives into the debris field; the first taking place from 24 to 30 June, and the second from late August until early September. The equipment-handling capability of ''Gilliss'' proved inadequate, even hazardous, to handle the towed vehicle, and the entire search was paused in September. By morning on 11 April, submarines USS ''Seawolf'' and USS ''Sea Owl'', both operating near ''Thresher’''s location, were ordered to join in the search for the missing submarine as well.

The inadequacy of the existing small Auxiliary General Oceanographic Research (AGOR) vessels such as the ''James M. Gilliss'' for handling deep-towed search vehicles led to a search for a vessel of a size and configuration that could handle such equipment in a sheltered area. In late 1963, that search resulted in the acquisition of , with the intent to eventually add a sheltered center well for deploying equipment.

The 1964 search included ''Mizar'' (with partial modifications but not a center well), , and ''Trieste II'', ''Trieste''s successor. That submersible incorporated parts of the original bathyscaphe and was completed in early 1964. The bathyscaphe was placed on board and shipped to Boston. ''Mizar'' did have a system called Underwater Tracking Equipment (UTE) by which it could track its towed vehicle, and it was planned for use to track ''Trieste''. Before her departure from NRL in Washington, ''Mizar'' was equipped with highly sensitive proton magnetometers furnished by the instrument division of Varian Associates

Varian Associates was one of the first high-tech companies in Silicon Valley. It was founded in 1948 by Russell H. and Sigurd F. Varian, William Webster Hansen, and Edward Ginzton to sell the klystron, the first vacuum tube which could amplify ...

in Palo Alto. In use, the magnetometers were suspended on an electrical line that also towed underwater video cameras.

''Mizar'' sailed on 25 June to begin the deep search and found the wreck within two days. The shattered remains of ''Thresher''s hull were on the sea floor, about below the surface, in five major sections. Most of the debris had spread over an area of about . Major sections of ''Thresher'', including the sail

A sail is a tensile structure—which is made from fabric or other membrane materials—that uses wind power to propel sailing craft, including sailing ships, sailboats, windsurfers, ice boats, and even sail-powered land vehicles. Sails ma ...

, sonar dome, bow section, engineering spaces section, operations spaces section, and the stern planes were found. By July 22, most of the lost submarine had been photographed. In early August, the entire task force returned to the area with the submersible. Its first two dives were unsuccessful, but on the third dive, the UTE enabled placement of ''Trieste II'' on the wreck, at first not seeing wreckage because the bathyscaphe was sitting upon it.

''Trieste II'' was commanded by Lieutenant John B. Mooney Jr., with co-pilot Lieutenant John H. Howland and Captain Frank Andrews, in an operation that recovered parts of the wreckage in September 1964.

On 9 July 2021, the United States Navy declassified the narrative of the submarine ''Seawolf'' during the search for the ''Thresher''. The ''Seawolf'' detected acoustic signals at 23.5 kHz and 3.5 kHz as well as metal banging noises which were interpreted at the time as originating from the ''Thresher''. However, after the commander of Task Group 89.7 ordered that echo ranging and fathometers be secured so as to not interfere with the search, no further acoustic signals were detected by the ''Seawolf'' other than those originating from other searching ships and the submarine ''Sea Owl''. Ultimately, the Court of Inquiry determined

Cause

Deep-sea photography, recovered artifacts, and an evaluation of ''Thresher''scram

A scram or SCRAM is an emergency shutdown of a nuclear reactor effected by immediately terminating the fission reaction. It is also the name that is given to the manually operated kill switch that initiates the shutdown. In commercial reactor ...

") of the reactor, which in turn caused loss of propulsion.

The inability to blow the ballast tanks was later attributed to excessive moisture in the submarine's high-pressure air flasks, moisture that froze and plugged the flasks' flowpaths while passing through the valves. This was later simulated in dockside tests on ''Thresher''s sister sub, . During a test to simulate blowing ballast at or near test depth, ice formed on strainers installed in valves; the flow of air lasted only a few seconds. Air dryers were later retrofitted to the high-pressure air compressors, beginning with ''Tinosa'', to permit the emergency blow system to operate properly. Submarines typically rely on speed and deck angle (angle of attack

In fluid dynamics, angle of attack (AOA, α, or \alpha) is the angle between a reference line on a body (often the chord line of an airfoil) and the vector representing the relative motion between the body and the fluid through which it is ...

) rather than deballasting to surface; they are propelled at an angle toward the surface. Ballast tanks were almost never blown at depth, as doing so could cause the submarine to rocket to the surface out of control. Normal procedure was to drive the submarine to periscope

A periscope is an instrument for observation over, around or through an object, obstacle or condition that prevents direct line-of-sight observation from an observer's current position.

In its simplest form, it consists of an outer case with ...

depth, raise the periscope to verify that the area was clear, and then blow the tanks and surface the submarine.

Subsequent study of SOSUS

The Sound Surveillance System (SOSUS) was a submarine detection system based on passive sonar developed by the United States Navy to track Soviet Navy, Soviet submarines. The system's true nature was classified with the name and acronym SOSUS them ...

(sound surveillance system) data from the time of the incident has given rise to doubts as to whether flooding preceded the reactor scram, as no impact sounds of the high pressure water in the compartments of the submarine could be detected on instrument recordings from SOSUS at the time. Such flooding would have caused a significant sonic event, and no evidence of such may be found in the recorded data.

At the time, reactor-plant operating procedures did not allow for a rapid reactor restart following a scram, or even the ability to use steam remaining in the secondary system to propel the submarine to the surface. After a scram, standard procedure was to isolate the main steam system, cutting off the flow of steam to the turbines providing propulsion and electricity. This was done to prevent an overly rapid cool-down of the reactor. ''Thresher''s reactor control officer, Lieutenant Raymond McCoole, was not at his station in the maneuvering room, or indeed on the boat during the fatal dive, as he was at home caring for his wife, who had been injured in a household accident. McCoole's trainee, Jim Henry, fresh from nuclear power school

Nuclear Power School (NPS) is a technical school operated by the U.S. Navy in Goose Creek, South Carolina as a central part of a program that trains enlisted sailors, officers, KAPL civilians and Bettis civilians for shipboard nuclear power ...

, probably followed standard operating procedures and gave the order to isolate the steam system after the scram, even though ''Thresher'' was at or slightly below its maximum depth. Once closed, the large steam system isolation valves could not be reopened quickly. Reflecting on the situation in later life, McCoole was sure that he would have delayed shutting the valves, thus allowing the boat to "answer bells" and drive itself to the surface, despite the flooding in the engineering spaces. Admiral Rickover noted that the procedures were for normal operating conditions, and not intended to restrict necessary actions in an emergency involving the safety of the ship. After the accident Rickover further reduced plant restart times, which had already been gradually improving with new technology and operating experience, in addition to limiting factors that could cause a shut down. The Fast Recovery Startup involves an immediate reactor restart and allows steam to be withdrawn from the secondary system in limited quantities for several minutes following a scram.

In a dockside simulation of flooding in the engine room, held before ''Thresher'' sailed, the watch in charge took 20 minutes to isolate a simulated leak in the auxiliary seawater system. At test depth with the reactor shut down, ''Thresher'' would not have had 20 minutes to recover. Even after isolating a short circuit in the reactor controls, it would have taken nearly 10 minutes to restart the plant.

It was believed at the time that ''Thresher'' likely imploded at a depth of , though 2013 acoustic analysis concluded implosion occurred at 730 meters.

The U.S. Navy has periodically monitored the environmental conditions of the site since the sinking and has reported the results in an annual public report on environmental monitoring for U.S. naval nuclear-powered craft. These reports provide results of the environmental sampling of sediment

Sediment is a naturally occurring material that is broken down by processes of weathering and erosion, and is subsequently transported by the action of wind, water, or ice or by the force of gravity acting on the particles. For example, sa ...

, water, and marine life, which is performed to ascertain whether ''Thresher''s nuclear reactor has had a significant effect on the deep-ocean environment. The reports also explain the methodology for conducting deep-sea monitoring from both surface vessels and submersibles. The monitoring data confirm that there has been no significant effect on the environment. Nuclear fuel in the submarine remains intact.

Information declassified in the 2008 National Geographic Documentary ''Titanic: Ballard's Secret Mission'' shows that USNR Commander (Dr.) Robert Ballard

Robert Duane Ballard (born June 30, 1942) is an American retired Navy officer and a professor of oceanography at the University of Rhode Island who is most noted for his work in underwater archaeology: maritime archaeology and archaeology ...

, the oceanographer credited with locating the wreck of , was sent by the Navy on a mission under cover of the search for ''Titanic'' to map and collect visual data on the ''Thresher'' and wrecks. Ballard had approached the Navy in 1982 for funding to find ''Titanic'' with his new deep-diving robot submersible. The Navy conditionally granted him the funds if the submarine wrecks were surveyed before ''Titanic''. Ballard's robotic survey showed that the depth at which ''Thresher'' had sunk caused implosion and total destruction; the only recoverable piece was a foot of mangled pipe. His 1985 search for ''Scorpion'' revealed a large debris field "as though it had been put through a shredding machine". His obligation to inspect the wrecks completed, and with the radioactive threat from both established as small, Ballard then searched for ''Titanic''. Financial limitations allowed him 12 days to search, and the debris-field search technique he had used for the two submarines was applied to locate ''Titanic''.

Almost all records of the court of inquiry remain unavailable to the public. In 1998, the Navy began declassifying them, but decided in 2012 that it would not release them to the public. In February 2020, in response to a FOIA lawsuit by military historian James Bryant, a federal court ordered the Navy to begin releasing documents by May 2020.

On May 22, 2020, the Navy stated in a court-mandated status report that due to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, the Navy's Undersea Warfare Division (OPNAV N97) had placed the records review on hold as N97 staff were limited to supporting mission-essential tasks supporting undersea forces and operations only. However, the Navy stated that they "will return to the review and process of Plaintiff’s FOIA request once the office is able to expand beyond mission-essential capabilities". Following the release of the July 18, 2020 court-mandated report the Navy stated that they had identified and approved additional resources and reservists to begin processing the documents in August. The Navy began a rolling release of the records on September 23, 2020.

The aftermath of the public relations aspect of this major disaster has since been part of various case studies.

Disaster sequence of 10 April 1963

During the 1963 inquiry, Admiral Hyman Rickover stated:

During the 1963 inquiry, Admiral Hyman Rickover stated:

I believe the loss of the ''Thresher'' should not be viewed solely as the result of failure of a specific braze, weld, system or component, but rather should be considered a consequence of the philosophy of design, construction and inspection that has been permitted in our naval shipbuilding programs. I think it is important that we re-evaluate our present practices where, in the desire to make advancements, we may have forsaken the fundamentals of good engineering.

Alternative theory of the sinking: electrical failure

On 8 April 2013, Bruce Rule, US Office of Naval Intelligence lead acoustic analyst for over 42 years, published his own analysis of the data collected by USS ''Skylark'' and AtlanticSOSUS

The Sound Surveillance System (SOSUS) was a submarine detection system based on passive sonar developed by the United States Navy to track Soviet Navy, Soviet submarines. The system's true nature was classified with the name and acronym SOSUS them ...

arrays in a paper in the ''Navy Times''. Rule based his analysis on SOSUS data that was highly classified in 1963, was not discussed in open session of the Court of Inquiry and was not revealed at the congressional hearings. A retired Navy captain and former commanding officer of the same class of submarine as ''Thresher'', citing Rule's findings, has called for the U.S. government to declassify the data associated with the boat's sinking, and presented an alternative disaster sequence based upon the acoustic data.

Rule concluded that the primary cause of the sinking was a failure of the electrical bus that powered the main coolant pumps. According to Rule, SOSUS data indicates that after two minutes of electrical instability, the bus failed at 09:11 a.m., causing the main coolant pumps to trip off. This caused an immediate reactor scram, resulting in a loss of propulsion. ''Thresher'' could not be deballasted because ice had formed in the high-pressure air pipes, and so she sank. Rule's analysis holds that flooding (whether from a silver brazed joint or anywhere else) played no role in the reactor scram or the sinking, and that ''Thresher'' was intact until she imploded. In addition to the SOSUS data that does not record any sound of flooding, the crew of ''Skylark'' did not report hearing any noise that sounded like flooding, and ''Skylark'' was able to communicate with ''Thresher'', despite the fact that, at test depth, even a small leak would have produced a deafening roar. Additionally, the previous commander of ''Thresher'' testified that he would not have described flooding, even from a small-diameter pipe, as a "minor problem".

Rule interprets the communication "900" from ''Thresher'' at 09:17 a.m. as a reference to test depth, signifying that ''Thresher'' was below her test depth of , or below sea level. According to Rule the SOSUS data indicates an implosion of ''Thresher'' at 09:18:24, at a depth of , below her predicted collapse depth. The implosion took 0.1 seconds, too fast for the human nervous system to perceive.

SUBSAFE legacy

When the Court of Inquiry delivered its final report, it recommended that the Navy implement a more rigorous program of design review and safety inspections during construction. That program, launched in December 1963, was known as SUBSAFE. From 1915 to 1963, the U.S. Navy lost a total of 16 submarines to non-combat accidents. Since the inception of SUBSAFE only one submarine has suffered a similar fate, and that was , which sank in 1968 for reasons still undetermined. ''Scorpion'' was not SUBSAFE certified.Memorials

Permanent

* The chapel atPortsmouth Navy Yard

The Portsmouth Naval Shipyard, often called the Portsmouth Navy Yard, is a United States Navy shipyard in Kittery on the southern boundary of Maine near the city of Portsmouth, New Hampshire.

Founded in 1800, PNS is U.S. Navy's oldest continu ...

, where the submarine was built, was renamed ''Thresher'' Memorial Chapel.

* In Portsmouth, New Hampshire, there is a stone memorial with a plaque honoring all who were lost on ''Thresher''. It is outside the museum.

* Just outside the main gate of the Naval Weapons Station, Seal Beach, California

Seal Beach is a coastal city in Orange County, California, United States. As of the 2020 census, the population was 25,242, up from 24,168 at the 2010 census.

Seal Beach is located in the westernmost corner of Orange County. To the northwest ...

, a ''Thresher''–''Scorpion'' Memorial honors the crews of the two submarines.

* In Eureka, Missouri

Eureka is a city located in St. Louis County, Missouri, United States, adjacent to the cities of Wildwood and Pacific, along Interstate 44. It is in the extreme southwest of the Greater St. Louis metro area. As of the 2020 census, the cit ...

, there is a marble stone at the post office on ''Thresher'' Drive honoring the "officers and crew of the USS ''Thresher,'' lost 10 April 1963."

* Salisbury, Massachusetts

Salisbury is a small coastal beach town and summer tourist destination in Essex County, Massachusetts, United States. The community is a popular summer resort beach town situated on the Atlantic Ocean, north of Boston on the New Hampshire borde ...

, named Robert E. Steinel Memorial Park in honor of ''Thresher'' crewman and Salisbury resident Sonarman First Class Robert Edwin Steinel.

* In Nutley, New Jersey

Nutley is a township in Essex County, New Jersey, United States. As of the 2020 United States census, the township's population was 30,143.

What is now Nutley was originally incorporated as Franklin Township by an act of the New Jersey Legisl ...

, there is a monument to ''Thresher'' crewmember Pervis Robison Jr.

* In Denville, New Jersey, there is a monument to ''Thresher'' crewmember Robert D. Kearney at the Gardner Field recreation area.

* ''Thresher'' Avenue, named for the submarine, serves a residential area in Naval Base Kitsap in Washington state.

* A flagpole at Kittery Memorial Circle in the town of Kittery, Maine

Kittery is a town in York County, Maine, United States. Home to the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard on Seavey's Island, Kittery includes Badger's Island, the seaside district of Kittery Point, and part of the Isles of Shoals. The southernmost tow ...

, was dedicated on 7 April 2013, the 50th anniversary of the loss of ''Thresher'', to honor the 129 lost souls''.''

* There is also a ''Thresher'' monument in Memorial Park next to the Kittery Town Hall.

* There is a memorial monument to the submariners lost in the ''Thresher'' and ''Scorpion'' located on Point Pleasant Road in Mount Pleasant, South Carolina

Mount Pleasant is a large suburban town in Charleston County, South Carolina, United States. In the Low Country, it is the fourth largest municipality and largest town in South Carolina, and for several years was one of the state's fastest-growin ...

.

* Naval Submarine Base New London

Naval Submarine Base New London is the primary United States Navy East Coast submarine base, also known as the "Home of the Submarine Force." It is located in Groton, Connecticut directly across the Thames River from its namesake city of New Lo ...

in Groton, Connecticut

Groton is a town in New London County, Connecticut located on the Thames River. It is the home of General Dynamics Electric Boat, which is the major contractor for submarine work for the United States Navy. The Naval Submarine Base New London ...

, named an enlisted barracks "''Thresher'' Hall" after the submarine, and mounted a plaque in its lobby displaying the names of the crew members, shipyard government employees and contractors that were lost.

* A joint resolution

In the United States Congress, a joint resolution is a legislative measure that requires passage by the Senate and the House of Representatives and is presented to the President for their approval or disapproval. Generally, there is no legal differ ...

was introduced during the 107th United States Congress

The 107th United States Congress was a meeting of the legislative branch of the United States federal government, composed of the United States Senate and the United States House of Representatives. It met in Washington, D.C. from January ...

in 2001 calling for the erection of a memorial in Arlington National Cemetery

Arlington National Cemetery is one of two national cemeteries run by the United States Army. Nearly 400,000 people are buried in its 639 acres (259 ha) in Arlington, Virginia. There are about 30 funerals conducted on weekdays and 7 held on Sa ...

. The formal commemorative monument approval process for Arlington, which began in 2012, received final approval in January 2019. The memorial was approved on January 28, 2019, by the Secretary of the Army, Mark Esper

Mark Thomas Esper (born April 26, 1964) is an American politician and manufacturing executive who served as the 27th United States secretary of defense from 2019 to 2020. A member of the Republican Party, he had previously served as the 23rd U ...

. While a few crew members already had memorials at Arlington, this became the first tribute there to the boat's entire crew and her other passengers. The memorial was dedicated on September 26, 2019.

;Former

* In Carpentersville, Illinois, the Dundee Township Park District named a swimming facility (now closed and demolished) in honor of ''Thresher''.

Other

* On 12 April 1963, President John F. Kennedy issued paying tribute to the crew of ''Thresher'' by ordering all national flags to half-staff. * Five folk music groups or artists have produced songs memorializing ''Thresher''; "Ballad Of The Thresher" byThe Kingston Trio

The Kingston Trio is an American folk and pop music group that helped launch the folk revival of the late 1950s to the late 1960s. The group started as a San Francisco Bay Area nightclub act with an original lineup of Dave Guard, Bob Shane, ...

, "The Thresher Disaster" by Tom Paxton

Thomas Richard Paxton (born October 31, 1937) is an American folk singer-songwriter who has had a music career spanning more than fifty years. In 2009, Paxton received a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award.Phil Ochs

Philip David Ochs (; December 19, 1940 – April 9, 1976) was an American songwriter and protest singer (or, as he preferred, a topical singer). Ochs was known for his sharp wit, sardonic humor, political activism, often alliterative lyrics, and ...

on his 1964 album '' All the News That's Fit to Sing'', "The Thresher" by Pete Seeger

Peter Seeger (May 3, 1919 – January 27, 2014) was an American folk singer and social activist. A fixture on nationwide radio in the 1940s, Seeger also had a string of hit records during the early 1950s as a member of the Weavers, notabl ...

, and "Thresher" by Shovels & Rope.

* ''The Fear-Makers'', an episode in the 1964 season of the television series ''Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea

''Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea'' is a 1961 American science fiction disaster film, produced and directed by Irwin Allen, and starring Walter Pidgeon and Robert Sterling. The supporting cast includes Peter Lorre, Joan Fontaine, Barbara E ...

'', is inspired by the loss of the USS ''Thresher''. Anthony Wilson, a writer for the series, was fascinated by the loss of the USS ''Thresher'' (and with 'fear gas' as an incapacitating chemical weapon aboard the submarines, an agent similar to the contemporary BZ gas), and he wrote a teleplay for the series. In Wilson's teleplay, the submarine, the ''Seaview Seaview or Sea View may refer to:

Places

* Clifton Beach, Karachi, also known as Sea View, a beach in Pakistan

* Sea View, Dorset, a suburb in England

* Seaview, Isle of Wight, a small village in England

* Seaview, Lower Hutt, an industrial suburb ...

'', searches for a missing submarine, the ''Polidor''.

See also

*Deep Submergence Rescue Vehicle

A deep-submergence rescue vehicle (DSRV) is a type of deep-submergence vehicle used for rescue of downed submarines and clandestine missions. While DSRV is the term most often used by the United States Navy, other nations have different desig ...

* , the only other American nuclear-powered submarine to be lost at sea

* John P. Craven, a key individual in the search for ''Thresher''

* ''Kursk'' submarine disaster, next-largest loss of life on a submarine

* List of sunken nuclear submarines

* List of lost United States submarines

* Ship Characteristics Board § USS Thresher loss

Footnotes

References

* One of the earliest and most comprehensive accounts of the loss of the ''Thresher'' was written by Vice Admiral E.W. Grenfell, Commander Submarine Force Atlantic, and published in March 1964 in the U.S. Navy's professional journal ''Proceedings''; on 1 April 2013, on the occasion of the 50th anniversary, the U.S. Naval Institute has re-posted Admiral Grenfell's detailed account:Loss of USS ''Thresher''

* * First published 1964; reissued in 2001 by Lyons Press (Guilford, Conn) as ''The Death of the USS Thresher'' * *

McCoole's statement re: shutting main steam valves during reactor scram

*

Further reading

* * U.S. Atlantic Fleet. Staff, Deputy Commander Submarine Force. (1964) United States Ship ''Thresher'' (SSN 593): In memoriam 10 April 1963. U.S. Navy Atlantic Fleet. No Available ISBN. * ''Thresher''s ship number 593 is interesting as a "good" prime number, as discussed at593

__NOTOC__

Year 593 (Roman numerals, DXCIII) was a common year starting on Thursday (link will display the full calendar) of the Julian calendar. The denomination 593 for this year has been used since the early medieval period, when the Anno Dom ...

.

External links

On Eternal Patrol: USS ''Thresher''

USS Thresher 593

Thresher Base United States Submarine Veterans

Memorial Video on YouTube

{{DEFAULTSORT:Thresher (Ssn-593) 1960 ships 1963 in the United States Cold War submarines of the United States Lost submarines of the United States Maritime incidents in 1963 Thresher, USS Permit-class submarines Ships built in Kittery, Maine Warships lost with all hands Thresher, USS Sunken nuclear submarines United States submarine accidents