USS Pennsylvania (BB-38) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

USS ''Pennsylvania'' (BB-38) was the lead ship of the of super-dreadnought battleships built for the

Part of the

Part of the

The

The

''Pennsylvania'' and the rest of the Atlantic Fleet departed on 19 February, bound for the Caribbean for another round of exercises in Cuban waters. The ship arrived back in New York on 14 April, and while there on 30 June, Mayo was replaced by Vice Admiral

''Pennsylvania'' and the rest of the Atlantic Fleet departed on 19 February, bound for the Caribbean for another round of exercises in Cuban waters. The ship arrived back in New York on 14 April, and while there on 30 June, Mayo was replaced by Vice Admiral

The ship arrived in San Francisco on 3 March, where she loaded ammunition before joining the Battle Fleet in San Diego on 9 March. The fleet cruised south to the

The ship arrived in San Francisco on 3 March, where she loaded ammunition before joining the Battle Fleet in San Diego on 9 March. The fleet cruised south to the  ''Pennsylvania'' remained at San Pedro from 11 December to 11 January 1927 when she left for another refit at Puget Sound that lasted until 12 March. She returned to San Francisco on 15 March and then moved to San Pedro the next day. She left to join training exercises off Cuba on 17 March; she passed through the canal between 29 and 31 March and arrived in

''Pennsylvania'' remained at San Pedro from 11 December to 11 January 1927 when she left for another refit at Puget Sound that lasted until 12 March. She returned to San Francisco on 15 March and then moved to San Pedro the next day. She left to join training exercises off Cuba on 17 March; she passed through the canal between 29 and 31 March and arrived in

The ship departed San Pedro on 9 February to participate in

The ship departed San Pedro on 9 February to participate in

On 1 August, ''Pennsylvania'' left San Francisco, bound for Pearl Harbor. She arrived there on 14 August and took part in further training, including guard tactics for aircraft carrier task forces. Another overhaul followed in San Francisco from 3 to 10 January 1943. After further training and tests at San Francisco and

On 1 August, ''Pennsylvania'' left San Francisco, bound for Pearl Harbor. She arrived there on 14 August and took part in further training, including guard tactics for aircraft carrier task forces. Another overhaul followed in San Francisco from 3 to 10 January 1943. After further training and tests at San Francisco and

Late on 28 October, ''Pennsylvania'' shot down a torpedo bomber. The ship remained on station off Leyte until 25 November, when she departed for Manus, from which she steamed to

Late on 28 October, ''Pennsylvania'' shot down a torpedo bomber. The ship remained on station off Leyte until 25 November, when she departed for Manus, from which she steamed to

''Pennsylvania'' was taken under tow by a pair of tugboats on 18 August, bound for Apra Harbor, Guam, where they arrived on 6 September. The next day, she was taken into a floating drydock, where a large steel patch was welded over the torpedo hole, which would allow the ship to make the voyage back for permanent repairs. The battleship relieved ''Pennsylvania'' as flagship on 15 September, and on 2 October, she was able to leave the drydock. Two days later, ''Pennsylvania'' steamed out of Guam, bound for Puget Sound, where repairs would be effected. She was escorted by the

''Pennsylvania'' was taken under tow by a pair of tugboats on 18 August, bound for Apra Harbor, Guam, where they arrived on 6 September. The next day, she was taken into a floating drydock, where a large steel patch was welded over the torpedo hole, which would allow the ship to make the voyage back for permanent repairs. The battleship relieved ''Pennsylvania'' as flagship on 15 September, and on 2 October, she was able to leave the drydock. Two days later, ''Pennsylvania'' steamed out of Guam, bound for Puget Sound, where repairs would be effected. She was escorted by the

United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

in the 1910s. The ''Pennsylvania''s were part of the standard-type battleship

The Standard-type battleship was a series of twelve battleships across five classes ordered for the United States Navy between 1911 and 1916 and commissioned between 1916 and 1923. These were considered super-dreadnoughts, with the ships of the ...

series, and marked an incremental improvement over the preceding , carrying an extra pair of guns for a total of twelve guns. Named for the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; (Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, Ma ...

, she was laid down

Laying the keel or laying down is the formal recognition of the start of a ship's construction. It is often marked with a ceremony attended by dignitaries from the shipbuilding company and the ultimate owners of the ship.

Keel laying is one ...

at the Newport News Shipbuilding and Drydock Company in October 1913, was launched in March 1915, and was commissioned in June 1916. Equipped with an oil-burning propulsion system, ''Pennsylvania'' was not sent to European waters during World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

, since the necessary fuel oil

Fuel oil is any of various fractions obtained from the distillation of petroleum (crude oil). Such oils include distillates (the lighter fractions) and residues (the heavier fractions). Fuel oils include heavy fuel oil, marine fuel oil (MFO), bu ...

was not as readily available as coal. Instead, she remained in American waters and took part in training exercises; in 1918, she escorted President Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was an American politician and academic who served as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. A member of the Democratic Party, Wilson served as the president of P ...

to France to take part in peace negotiations.

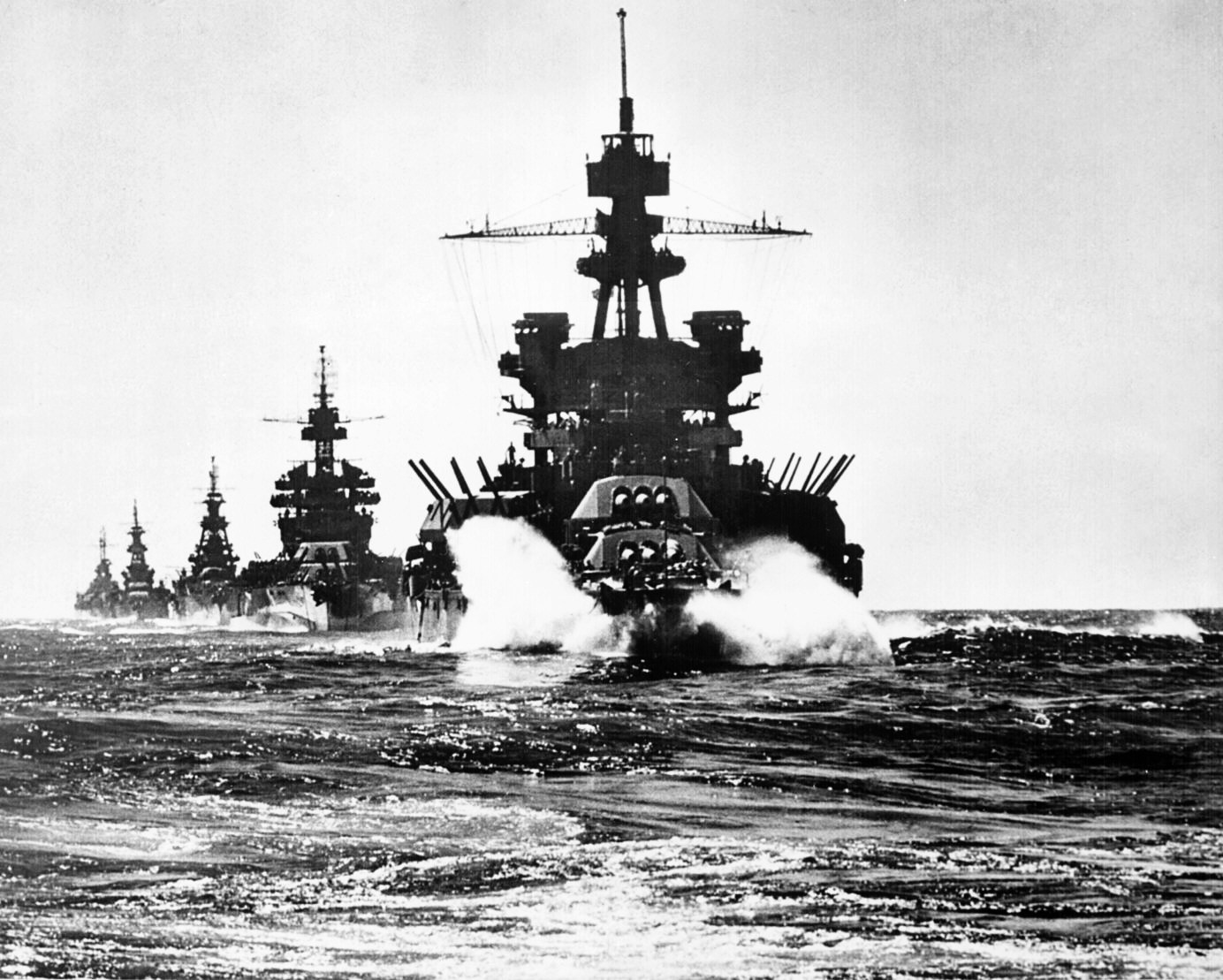

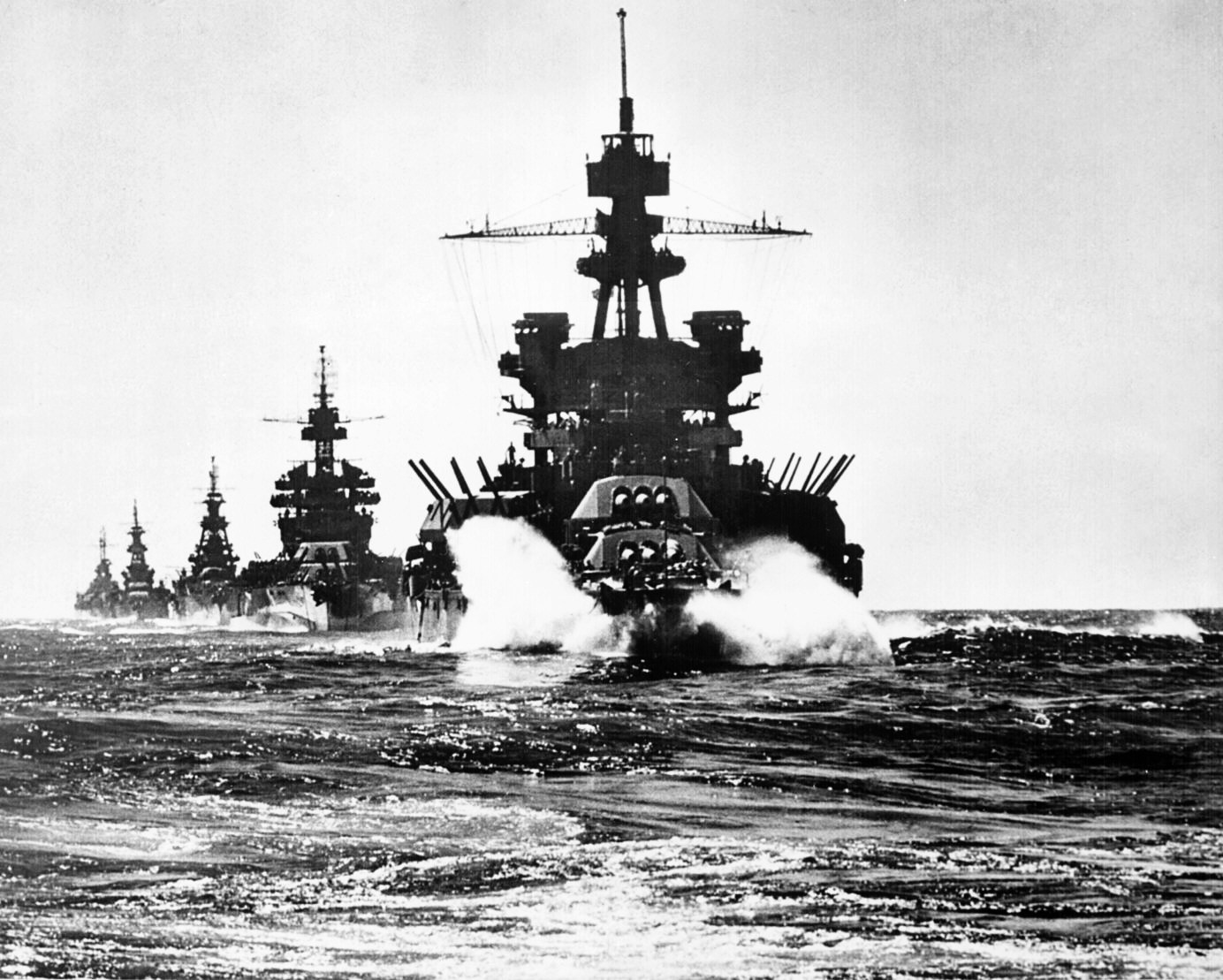

During the 1920s and 1930s, ''Pennsylvania'' served as the flagship

A flagship is a vessel used by the commanding officer of a group of naval ships, characteristically a flag officer entitled by custom to fly a distinguishing flag. Used more loosely, it is the lead ship in a fleet of vessels, typically the f ...

of first the Atlantic Fleet, and after it was merged with the Pacific Fleet in 1921, the Battle Fleet. For the majority of this period, the ship was stationed in California, based in San Pedro. ''Pennsylvania'' was occupied with a peacetime routine of training exercises (including the annual Fleet problem The Fleet Problems are a series of naval exercises of the United States Navy conducted in the interwar period, and later resurrected by Pacific Fleet around 2014.

The first twenty-one Fleet Problems — labeled with roman numerals as Fleet Probl ...

s), port visits, and foreign cruises, including a visit to Australia in 1925. The ship was modernized in 1929–1931. The ship was present in Pearl Harbor

Pearl Harbor is an American lagoon harbor on the island of Oahu, Hawaii, west of Honolulu. It was often visited by the Naval fleet of the United States, before it was acquired from the Hawaiian Kingdom by the U.S. with the signing of the ...

on the morning of 7 December 1941; she was in drydock with a pair of destroyers when the Japanese launched their surprise attack on the port. She suffered relatively minor damage in the attack, being protected from torpedoes by the drydock. While repairs were effected, the ship received a modernized anti-aircraft battery to prepare her for operations in the Pacific War.

''Pennsylvania'' joined the fleet in a series of amphibious operations, primarily tasked with providing gunfire support. The first of these, the Aleutian Islands Campaign, took place in mid-1943, and was followed by an attack on Makin later that year. During 1944, she supported the landings on Kwajalein and Eniwetok

Enewetak Atoll (; also spelled Eniwetok Atoll or sometimes Eniewetok; mh, Ānewetak, , or , ; known to the Japanese as Brown Atoll or Brown Island; ja, ブラウン環礁) is a large coral atoll of 40 islands in the Pacific Ocean and with ...

in the Marshall Islands

The Marshall Islands ( mh, Ṃajeḷ), officially the Republic of the Marshall Islands ( mh, Aolepān Aorōkin Ṃajeḷ),'' () is an independent island country and microstate near the Equator in the Pacific Ocean, slightly west of the Internati ...

and the Mariana and Palau Islands campaign

The Mariana and Palau Islands campaign, also known as Operation Forager, was an offensive launched by United States forces against Imperial Japanese forces in the Mariana Islands and Palau in the Pacific Ocean between June and November 1944 d ...

, including the Battles of Saipan, Guam

Guam (; ch, Guåhan ) is an organized, unincorporated territory of the United States in the Micronesia subregion of the western Pacific Ocean. It is the westernmost point and territory of the United States (reckoned from the geographic ce ...

, Peleliu

Peleliu (or Beliliou) is an island in the island nation of Palau. Peleliu, along with two small islands to its northeast, forms one of the sixteen states of Palau. The island is notable as the location of the Battle of Peleliu in World War II.

...

, and Battle of Angaur. During the Philippines campaign, in addition to her typical shore bombardment duties, she took part in the Battle of Surigao Strait, though due to her inadequate radar, she was unable to locate a target and did not fire. During the Battle of Okinawa

The , codenamed Operation Iceberg, was a major battle of the Pacific War fought on the island of Okinawa by United States Army (USA) and United States Marine Corps (USMC) forces against the Imperial Japanese Army (IJA). The initial invasion of ...

, she was torpedoed by a Japanese torpedo bomber

A torpedo bomber is a military aircraft designed primarily to attack ships with aerial torpedoes. Torpedo bombers came into existence just before the First World War almost as soon as aircraft were built that were capable of carrying the weight ...

and badly damaged, forcing her to withdraw for repairs days before the end of the war.

Allocated to the target fleet for the Operation Crossroads

Operation Crossroads was a pair of nuclear weapon tests conducted by the United States at Bikini Atoll in mid-1946. They were the first nuclear weapon tests since Trinity in July 1945, and the first detonations of nuclear devices since the ...

nuclear tests in 1946, ''Pennsylvania'' was repaired only enough to allow her to make the voyage to the test site, Bikini Atoll

Bikini Atoll ( or ; Marshallese: , , meaning "coconut place"), sometimes known as Eschscholtz Atoll between the 1800s and 1946 is a coral reef in the Marshall Islands consisting of 23 islands surrounding a central lagoon. After the Sec ...

. She survived both blasts, but was badly contaminated with radioactive fallout from the second test, and so was towed to Kwajalein

Kwajalein Atoll (; Marshallese language, Marshallese: ) is part of the Marshall Islands, Republic of the Marshall Islands (RMI). The southernmost and largest island in the atoll is named Kwajalein Island, which its majority English-speaking res ...

, where she was studied for the next year and a half. The ship was ultimately scuttled

Scuttling is the deliberate sinking of a ship. Scuttling may be performed to dispose of an abandoned, old, or captured vessel; to prevent the vessel from becoming a navigation hazard; as an act of self-destruction to prevent the ship from being ...

in deep water off the atoll in February 1948.

Description

standard-type battleship

The Standard-type battleship was a series of twelve battleships across five classes ordered for the United States Navy between 1911 and 1916 and commissioned between 1916 and 1923. These were considered super-dreadnoughts, with the ships of the ...

series, the ''Pennsylvania''-class ships were significantly larger than their predecessors, the . ''Pennsylvania'' had an overall length of , a beam of (at the waterline

The waterline is the line where the hull of a ship meets the surface of the water. Specifically, it is also the name of a special marking, also known as an international load line, Plimsoll line and water line (positioned amidships), that ind ...

), and a draft of at deep load

The displacement or displacement tonnage of a ship is its weight. As the term indicates, it is measured indirectly, using Archimedes' principle, by first calculating the volume of water displaced by the ship, then converting that value into we ...

. This was longer than the older ships. She displaced at standard and at deep load, over more than the older ships. The ship had a metacentric height

The metacentric height (GM) is a measurement of the initial static stability of a floating body. It is calculated as the distance between the centre of gravity of a ship and its metacentre. A larger metacentric height implies greater initial stab ...

of at deep load.

The ship had four direct-drive Curtis steam turbine

A steam turbine is a machine that extracts thermal energy from pressurized steam and uses it to do mechanical work on a rotating output shaft. Its modern manifestation was invented by Charles Parsons in 1884. Fabrication of a modern steam turb ...

sets, each of which drove a propeller in diameter. They were powered by twelve Babcock & Wilcox

Babcock & Wilcox is an American renewable, environmental and thermal energy technologies and service provider that is active and has operations in many international markets across the globe with its headquarters in Akron, Ohio, USA. Historicall ...

water-tube boiler

A high pressure watertube boiler (also spelled water-tube and water tube) is a type of boiler in which water circulates in tubes heated externally by the fire. Fuel is burned inside the furnace, creating hot gas which boils water in the steam-gene ...

s. The turbines were designed to produce a total of , for a designed speed of . She was designed to normally carry of fuel oil

Fuel oil is any of various fractions obtained from the distillation of petroleum (crude oil). Such oils include distillates (the lighter fractions) and residues (the heavier fractions). Fuel oils include heavy fuel oil, marine fuel oil (MFO), bu ...

, but had a maximum capacity of . At full capacity, the ship could steam at a speed of for an estimated with a clean bottom. She had four turbo generators.

''Pennsylvania'' carried twelve 45- caliber guns in triple gun turret

A gun turret (or simply turret) is a mounting platform from which weapons can be fired that affords protection, visibility and ability to turn and aim. A modern gun turret is generally a rotatable weapon mount that houses the crew or mechani ...

s. The turrets were numbered from I to IV from front to rear. The guns could not elevate independently and were limited to a maximum elevation of +15° which gave them a maximum range of . The ship carried 100 shells for each gun. Defense against torpedo boat

A torpedo boat is a relatively small and fast naval ship designed to carry torpedoes into battle. The first designs were steam-powered craft dedicated to ramming enemy ships with explosive spar torpedoes. Later evolutions launched variants of s ...

s was provided by twenty-two 51-caliber guns mounted in individual casemate

A casemate is a fortified gun emplacement or armored structure from which guns are fired, in a fortification, warship, or armoured fighting vehicle.Webster's New Collegiate Dictionary

When referring to antiquity, the term "casemate wall" mean ...

s in the sides of the ship's hull. Positioned as they were they proved vulnerable to sea spray and could not be worked in heavy seas. At an elevation of 15°, they had a maximum range of . Each gun was provided with 230 rounds of ammunition. The ship mounted four 50-caliber three-inch guns for anti-aircraft

Anti-aircraft warfare, counter-air or air defence forces is the battlespace response to aerial warfare, defined by NATO as "all measures designed to nullify or reduce the effectiveness of hostile air action".AAP-6 It includes surface based, ...

defense, although only two were fitted when completed. The other pair were added shortly afterward on top of Turret III. ''Pennsylvania'' also mounted two torpedo tube

A torpedo tube is a cylindrical device for launching torpedoes.

There are two main types of torpedo tube: underwater tubes fitted to submarines and some surface ships, and deck-mounted units (also referred to as torpedo launchers) installed abo ...

s submerged, one on each broadside, and carried 24 torpedo

A modern torpedo is an underwater ranged weapon launched above or below the water surface, self-propelled towards a target, and with an explosive warhead designed to detonate either on contact with or in proximity to the target. Historically, s ...

es for them.

The ''Pennsylvania''-class design continued the all-or-nothing principle of armoring only the most important areas of the ship begun in the ''Nevada'' class. The waterline armor belt

Belt armor is a layer of heavy metal armor plated onto or within the outer hulls of warships, typically on battleships, battlecruisers and cruisers, and aircraft carriers.

The belt armor is designed to prevent projectiles from penetrating ...

of Krupp armor measured thick and covered only the ship's machinery spaces and magazines

A magazine is a periodical publication, generally published on a regular schedule (often weekly or monthly), containing a variety of content. They are generally financed by advertising, purchase price, prepaid subscriptions, or by a combina ...

. It had a total height of , of which was below the waterline; beginning below the waterline, the belt tapered to its minimum thickness of . The transverse bulkheads at each end of the ship ranged from 13 to 8 inches in thickness. The faces of the gun turrets were thick while the sides were thick and the turret roofs were protected by of armor. The armor of the barbette

Barbettes are several types of gun emplacement in terrestrial fortifications or on naval ships.

In recent naval usage, a barbette is a protective circular armour support for a heavy gun turret. This evolved from earlier forms of gun protectio ...

s was thick. The conning tower was protected by of armor and had a roof eight inches thick.

The main armor deck was three plates thick with a total thickness of ; over the steering gear the armor increased to in two plates. Beneath it was the splinter deck that ranged from in thickness. The boiler uptakes were protected by a conical mantlet

A mantlet was a portable wall or shelter used for stopping projectiles in medieval warfare. It could be mounted on a wheeled carriage, and protected one or several soldiers.

In the First World War a mantlet type of device was used by the French ...

that ranged from in thickness. A three-inch torpedo bulkhead was placed inboard from the ship's side and the ship was provided with a complete double bottom

A double hull is a ship hull design and construction method where the bottom and sides of the ship have two complete layers of watertight hull surface: one outer layer forming the normal hull of the ship, and a second inner hull which is some dist ...

. Testing in mid-1914 revealed that this system could withstand of TNT.

Service history

Construction and World War I

The

The keel

The keel is the bottom-most longitudinal structural element on a vessel. On some sailboats, it may have a hydrodynamic and counterbalancing purpose, as well. As the laying down of the keel is the initial step in the construction of a ship, in B ...

for ''Pennsylvania'' was laid down

Laying the keel or laying down is the formal recognition of the start of a ship's construction. It is often marked with a ceremony attended by dignitaries from the shipbuilding company and the ultimate owners of the ship.

Keel laying is one ...

on 27 October 1913 at the Newport News Shipbuilding

Newport News Shipbuilding (NNS), a division of Huntington Ingalls Industries, is the largest industrial employer in Virginia, and sole designer, builder and refueler of United States Navy aircraft carriers and one of two providers of U.S. Navy ...

and Dry Dock Company of Newport News, Virginia

Newport News () is an independent city in the U.S. state of Virginia. At the 2020 census, the population was 186,247. Located in the Hampton Roads region, it is the 5th most populous city in Virginia and 140th most populous city in the U ...

. Her completed hull

Hull may refer to:

Structures

* Chassis, of an armored fighting vehicle

* Fuselage, of an aircraft

* Hull (botany), the outer covering of seeds

* Hull (watercraft), the body or frame of a ship

* Submarine hull

Mathematics

* Affine hull, in affi ...

was launched on 16 March 1915, thereafter beginning fitting-out

Fitting out, or outfitting, is the process in shipbuilding that follows the float-out/launching of a vessel and precedes sea trials. It is the period when all the remaining construction of the ship is completed and readied for delivery to her ...

. Work on the ship finished in mid-1916, and she was commissioned on 12 June under the command of Captain Henry B. Wilson. The ship was assigned to the Atlantic Fleet and then completed final fitting out from 1 to 20 July. ''Pennsylvania'' then began sea trials

A sea trial is the testing phase of a watercraft (including boats, ships, and submarines). It is also referred to as a "shakedown cruise" by many naval personnel. It is usually the last phase of construction and takes place on open water, and ...

in 20 July, steaming first to the southern drill grounds off the Virginia Capes

The Virginia Capes are the two capes, Cape Charles to the north and Cape Henry to the south, that define the entrance to Chesapeake Bay on the eastern coast of North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere ...

and then north to the coast of New England

New England is a region comprising six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York to the west and by the Canadian province ...

. Rear Admiral

Rear admiral is a senior naval flag officer rank, equivalent to a major general and air vice marshal and above that of a commodore and captain, but below that of a vice admiral. It is regarded as a two star " admiral" rank. It is often rega ...

Austin M. Knight and officers from the Naval War College

The Naval War College (NWC or NAVWARCOL) is the staff college and "Home of Thought" for the United States Navy at Naval Station Newport in Newport, Rhode Island. The NWC educates and develops leaders, supports defining the future Navy and associ ...

came aboard on 21 August to observe fleet training exercises. Three days later, the ship was visited by Franklin Delano Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

, then the Assistant Secretary of the Navy

Assistant Secretary of the Navy (ASN) is the title given to certain civilian senior officials in the United States Department of the Navy.

From 1861 to 1954, the Assistant Secretary of the Navy was the second-highest civilian office in the Depa ...

.

Rear Admiral Henry T. Mayo

Henry Thomas Mayo (8 December 1856 – 23 February 1937) was an admiral of the United States Navy.

Mayo was born in Burlington, Vermont, 8 December 1856. Upon graduation from the United States Naval Academy in 1876 he experienced a variety of n ...

transferred to ''Pennsylvania'' on 12 October, making her the flagship

A flagship is a vessel used by the commanding officer of a group of naval ships, characteristically a flag officer entitled by custom to fly a distinguishing flag. Used more loosely, it is the lead ship in a fleet of vessels, typically the f ...

of the Atlantic Fleet. At the end of the year, she went into drydock at the New York Navy Yard

The Brooklyn Navy Yard (originally known as the New York Navy Yard) is a shipyard and industrial complex located in northwest Brooklyn in New York City, New York. The Navy Yard is located on the East River in Wallabout Bay, a semicircular bend ...

for maintenance. After emerging from the shipyard in January 1917, she steamed south to join fleet exercises in the Caribbean Sea

The Caribbean Sea ( es, Mar Caribe; french: Mer des Caraïbes; ht, Lanmè Karayib; jam, Kiaribiyan Sii; nl, Caraïbische Zee; pap, Laman Karibe) is a sea of the Atlantic Ocean in the tropics of the Western Hemisphere. It is bounded by Mexico ...

, during which she stopped in: Culebra, Puerto Rico

Isla Culebra (, ''Snake Island'') is an island, town and municipality of Puerto Rico and geographically part of the Spanish Virgin Islands. It is located approximately east of the Puerto Rican mainland, west of St. Thomas and north of Vieque ...

; Santo Domingo

, total_type = Total

, population_density_km2 = auto

, timezone = AST (UTC −4)

, area_code_type = Area codes

, area_code = 809, 829, 849

, postal_code_type = Postal codes

, postal_code = 10100–10699 ( Distrito Nacional)

, webs ...

, Dominican Republic; and Port-au-Prince

Port-au-Prince ( , ; ht, Pòtoprens ) is the capital and most populous city of Haiti. The city's population was estimated at 987,311 in 2015 with the metropolitan area estimated at a population of 2,618,894. The metropolitan area is defin ...

, Haiti. While in Port-au-Prince, ''Pennsylvania'' again hosted Roosevelt, who met with the President of Haiti

The president of Haiti ( ht, Prezidan peyi Ayiti, french: Président d'Haïti), officially called the president of the Republic of Haiti (french: link=no, Président de la République d'Haïti, ht, link=no, Prezidan Repiblik Ayiti), is the head ...

aboard the ship. The battleship arrived back in Yorktown, Virginia

Yorktown is a census-designated place (CDP) in York County, Virginia. It is the county seat of York County, one of the eight original shires formed in colonial Virginia in 1682. Yorktown's population was 195 as of the 2010 census, while York Co ...

on 6 April, the same day the United States declared war on Germany, bringing the country into World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

. Since ''Pennsylvania'' was oil-fired, she did not join the ships of Battleship Division Nine, as the British had asked for coal-burning battleships to reinforce the Grand Fleet

The Grand Fleet was the main battlefleet of the Royal Navy during the First World War. It was established in August 1914 and disbanded in April 1919. Its main base was Scapa Flow in the Orkney Islands.

History

Formed in August 1914 from the ...

. As a result, she stayed in American waters and saw no action during the war.

In August, ''Pennsylvania'' took part in a naval review for President Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was an American politician and academic who served as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. A member of the Democratic Party, Wilson served as the president of P ...

. Foreign naval officers visited the ship in September, including the Japanese Vice Admiral Isamu Takeshita and the Russian Vice Admiral Alexander Kolchak

Alexander Vasilyevich Kolchak (russian: link=no, Александр Васильевич Колчак; – 7 February 1920) was an Imperial Russian admiral, military leader and polar explorer who served in the Imperial Russian Navy and fough ...

. For the rest of the year and into 1918, ''Pennsylvania'' was kept in a state of readiness through fleet exercises and gunnery training in Chesapeake Bay

The Chesapeake Bay ( ) is the largest estuary in the United States. The Bay is located in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region and is primarily separated from the Atlantic Ocean by the Delmarva Peninsula (including the parts: the ...

and Long Island Sound. She was preparing for night battle training on 11 November 1918, when the Armistice with Germany

The Armistice of 11 November 1918 was the armistice signed at Le Francport near Compiègne that ended fighting on land, sea, and air in World War I between the Entente and their last remaining opponent, Germany. Previous armistic ...

came into effect, ending the fighting. She thereafter returned for another stint in the New York Navy Yard for maintenance that was completed on 21 November. She began the voyage to Brest, France

Brest (; ) is a port city in the Finistère department, Brittany. Located in a sheltered bay not far from the western tip of the peninsula, and the western extremity of metropolitan France, Brest is an important harbour and the second French ...

, on 2 December by way of Tomkinsville, New York, in company with the transport ship that carried Wilson to France to take part in the peace negotiations; they were escorted by ten destroyers. The ships arrived on 13 December and the next day, ''Pennsylvania'' began the trip back to New York with Battleship Divisions Nine and Six. The battleships reached their destination on 26 December, where they took part in victory celebrations.

Inter-war period

1919–1924

''Pennsylvania'' and the rest of the Atlantic Fleet departed on 19 February, bound for the Caribbean for another round of exercises in Cuban waters. The ship arrived back in New York on 14 April, and while there on 30 June, Mayo was replaced by Vice Admiral

''Pennsylvania'' and the rest of the Atlantic Fleet departed on 19 February, bound for the Caribbean for another round of exercises in Cuban waters. The ship arrived back in New York on 14 April, and while there on 30 June, Mayo was replaced by Vice Admiral Henry Wilson

Henry Wilson (born Jeremiah Jones Colbath; February 16, 1812 – November 22, 1875) was an American politician who was the 18th vice president of the United States from 1873 until his death in 1875 and a senator from Massachusetts from 1855 to ...

. On 8 July at Tomkinsville, a delegation consisting of: Vice President Thomas R. Marshall; Josephus Daniels

Josephus Daniels (May 18, 1862 – January 15, 1948) was an American newspaper editor and publisher from the 1880s until his death, who controlled Raleigh's '' News & Observer'', at the time North Carolina's largest newspaper, for decades. A ...

, the Secretary of the Navy

The secretary of the Navy (or SECNAV) is a statutory officer () and the head (chief executive officer) of the Department of the Navy, a military department (component organization) within the United States Department of Defense.

By law, the se ...

; Carter Glass

Carter Glass (January 4, 1858 – May 28, 1946) was an American newspaper publisher and Democratic politician from Lynchburg, Virginia. He represented Virginia in both houses of Congress and served as the United States Secretary of the Trea ...

, the Secretary of the Treasury

The United States secretary of the treasury is the head of the United States Department of the Treasury, and is the chief financial officer of the federal government of the United States. The secretary of the treasury serves as the principal a ...

; William B. Wilson

William Bauchop Wilson (April 2, 1862 – May 25, 1934) was an American labor leader and progressive politician, who immigrated as a child with his family from Lanarkshire, Scotland. After having worked as a child and adult in the coal mines of ...

, the Secretary of Labor

The United States Secretary of Labor is a member of the Cabinet of the United States, and as the head of the United States Department of Labor, controls the department, and enforces and suggests laws involving unions, the workplace, and all ot ...

; Newton D. Baker

Newton Diehl Baker Jr. (December 3, 1871 – December 25, 1937) was an American lawyer, Georgist,Noble, Ransom E. "Henry George and the Progressive Movement." The American Journal of Economics and Sociology, vol. 8, no. 3, 1949, pp. 259–269. w ...

, the Secretary of War

The secretary of war was a member of the U.S. president's Cabinet, beginning with George Washington's administration. A similar position, called either "Secretary at War" or "Secretary of War", had been appointed to serve the Congress of the ...

; Franklin K. Lane, the Secretary of the Interior; and Senator Champ Clark came aboard the ship for a cruise back to New York. The fleet conducted another set of maneuvers in the Caribbean from 7 January to April 1920, ''Pennsylvania'' returning to her berth in New York on 26 April. Training exercises in the area followed, and on 17 July she received the hull number

Hull number is a serial identification number given to a boat or ship. For the military, a lower number implies an older vessel. For civilian use, the HIN is used to trace the boat's history. The precise usage varies by country and type.

United S ...

BB-38.

On 17 January 1921, ''Pennsylvania'' left New York, passed through the Panama Canal

The Panama Canal ( es, Canal de Panamá, link=no) is an artificial waterway in Panama that connects the Atlantic Ocean with the Pacific Ocean and divides North and South America. The canal cuts across the Isthmus of Panama and is a Channel ( ...

to Balboa, Panama

Balboa is a district of Panama City, located at the Pacific entrance to the Panama Canal.

History

The town of Balboa, founded by the United States during the construction of the Panama Canal, was named after Vasco Núñez de Balboa, the ...

, where she joined the Pacific Fleet, which together with elements of the Atlantic Fleet was re-designated as the Battle Fleet, with ''Pennsylvania'' as its flagship. On 21 January, the fleet left Balboa and steamed south to Callao, Peru, where they arrived ten days later. The ships then steamed north back to Balboa on 2 February, arriving on 14 February. ''Pennsylvania'' crossed back through the canal to take part in maneuvers off Cuba and on 28 April she arrived in Hampton Roads

Hampton Roads is the name of both a body of water in the United States that serves as a wide channel for the James River, James, Nansemond River, Nansemond and Elizabeth River (Virginia), Elizabeth rivers between Old Point Comfort and Sewell's ...

, Virginia, where President Warren G. Harding, Edwin Denby, the Secretary of the Navy, Theodore Roosevelt Jr., the Assistant Secretary of the Navy, and Admiral Robert Coontz, the Chief of Naval Operations (CNO), came aboard the ship. Further training was held from 12 to 21 July in the Caribbean, after which she returned to New York. On 30 July, she proceeded on to Plymouth, Massachusetts

Plymouth (; historically known as Plimouth and Plimoth) is a town in Plymouth County, Massachusetts, United States. Located in Greater Boston, the town holds a place of great prominence in American history, folklore, and culture, and is known a ...

for a visit that lasted until 2 August. Anothery drydock period in New York lasted from 5 to 20 August.

''Pennsylvania'' departed New York thereafter, bound for the Pacific; she passed through the Panama Canal on 30 August and remained at Balboa for two weeks. On 15 September, she resumed the voyage and steamed north to San Pedro, Los Angeles, which she reached on 26 September. The ship spent most of 1922 visiting ports along the US west coast, including San Francisco

San Francisco (; Spanish language, Spanish for "Francis of Assisi, Saint Francis"), officially the City and County of San Francisco, is the commercial, financial, and cultural center of Northern California. The city proper is the List of Ca ...

, Seattle

Seattle ( ) is a port, seaport city on the West Coast of the United States. It is the county seat, seat of King County, Washington, King County, Washington (state), Washington. With a 2020 population of 737,015, it is the largest city in bo ...

, Port Angeles, and San Diego

San Diego ( , ; ) is a city on the Pacific Ocean coast of Southern California located immediately adjacent to the Mexico–United States border. With a 2020 population of 1,386,932, it is the eighth most populous city in the United States ...

, and from 6 March to 19 April, she underwent a refit at the Puget Sound Navy Yard. She won the Battle Efficiency Award for the 1922 training year. She went back to Puget Sound on 18 December, and remained there into 1923. She left the shipyard on 28 January and steamed south to San Diego, where she stayed from 2 to 8 February, before continuing on to the Panama Canal. After passing through, she steamed to Culebra for a short visit. The ship then passed back through the canal and arrived back in San Pedro on 13 April. Beginning in May, she visited various ports in the area over the course of the rest of 1923, apart from a round of fleet training from 27 November to 7 December. She ended the year with another stint in Puget Sound from 22 December until 1 March 1924.

1924–1931

The ship arrived in San Francisco on 3 March, where she loaded ammunition before joining the Battle Fleet in San Diego on 9 March. The fleet cruised south to the

The ship arrived in San Francisco on 3 March, where she loaded ammunition before joining the Battle Fleet in San Diego on 9 March. The fleet cruised south to the Gulf of Fonseca

The Gulf of Fonseca ( es, Golfo de Fonseca; ), a part of the Pacific Ocean, is a gulf in Central America, bordering El Salvador, Honduras, and Nicaragua.

History

Fonseca Bay was discovered for Europeans in 1522 by Gil González de Ávila ...

, then continued south and passed through the Panama Canal to Limon Bay

Limon Bay (''Bahía Limón'' in the original Spanish) is a natural harbor located at the north end of the Panama Canal, west of the cities of Cristóbal, Colón, Cristóbal and Colón, Panama, Colón. Ships waiting to enter the canal stay here, pro ...

. The ships visited several ports in the Caribbean, including in the US Virgin Islands

The United States Virgin Islands,. Also called the ''American Virgin Islands'' and the ''U.S. Virgin Islands''. officially the Virgin Islands of the United States, are a group of Caribbean islands and an unincorporated and organized territory ...

and Puerto Rico before returning to the Pacific in early April. ''Pennsylvania'' arrived back in San Pedro on 22 April, where she remained until 25 June, when she steamed north to Seattle. By this time, she was serving as the flagship of Battle Division 3 of the Battle Fleet. While in the Seattle area, she took part in training exercises with the ships of her division that lasted until 1 September. Further training exercises took place from 12 to 22 September off San Francisco. She thereafter took part in joint training with the coastal defenses around San Francisco from 26 to 29 September. The ship underwent a pair of overhauls from 1 to 13 October and 13 December to 5 January 1925. ''Pennsylvania'' then steamed to Puget Sound on 21 January for a third overhaul that lasted from 25 January to 24 March.

''Pennsylvania'' returned to San Pedro on 27 March and then joined the fleet in San Francisco on 5 April. The ships then steamed to Hawaii for training exercises before departing on 1 July for a major cruise across the Pacific to Australia. They reached Melbourne

Melbourne ( ; Boonwurrung/ Woiwurrung: ''Narrm'' or ''Naarm'') is the capital and most populous city of the Australian state of Victoria, and the second-most populous city in both Australia and Oceania. Its name generally refers to a me ...

on 22 July, and on 6 August ''Pennsylvania'' steamed to Wellington

Wellington ( mi, Te Whanganui-a-Tara or ) is the capital city of New Zealand. It is located at the south-western tip of the North Island, between Cook Strait and the Remutaka Range. Wellington is the second-largest city in New Zealand by m ...

, New Zealand, where she stayed from 11 to 22 August. On the voyage back to the United States, they stopped in Pago Pago

Pago Pago ( ; Samoan: )Harris, Ann G. and Esther Tuttle (2004). ''Geology of National Parks''. Kendall Hunt. Page 604. . is the territorial capital of American Samoa. It is in Maoputasi County on Tutuila, which is American Samoa's main island ...

in American Samoa

American Samoa ( sm, Amerika Sāmoa, ; also ' or ') is an unincorporated territory of the United States located in the South Pacific Ocean, southeast of the island country of Samoa. Its location is centered on . It is east of the Internation ...

and Hawaii, before reaching San Pedro on 26 September. ''Pennsylvania'' went to San Diego for target practice from 5 to 8 October, thereafter returning to San Pedro, where she remained largely idle for the rest of 1925. She left San Pedro with the Battle Fleet on 1 February 1926 for another visit to Balboa, during which the ships conducted tactical training from 15 to 27 February. ''Pennsylvania'' spent early March in California before departing for Puget Sound on 15 March for another refit that lasted until 14 May, at which point she returned to San Pedro. Another tour of west coast ports began on 16 June and ended on 1 September back in San Pedro.

''Pennsylvania'' remained at San Pedro from 11 December to 11 January 1927 when she left for another refit at Puget Sound that lasted until 12 March. She returned to San Francisco on 15 March and then moved to San Pedro the next day. She left to join training exercises off Cuba on 17 March; she passed through the canal between 29 and 31 March and arrived in

''Pennsylvania'' remained at San Pedro from 11 December to 11 January 1927 when she left for another refit at Puget Sound that lasted until 12 March. She returned to San Francisco on 15 March and then moved to San Pedro the next day. She left to join training exercises off Cuba on 17 March; she passed through the canal between 29 and 31 March and arrived in Guantánamo Bay

Guantánamo Bay ( es, Bahía de Guantánamo) is a bay in Guantánamo Province at the southeastern end of Cuba. It is the largest harbor on the south side of the island and it is surrounded by steep hills which create an enclave that is cut off ...

on 4 April. On 18 April, she left Cuba to visit Gonaïves

Gonaïves (; ht, Gonayiv, ) is a commune in northern Haiti, and the capital of the Artibonite department of Haiti. It has a population of about 300,000 people, but current statistics are unclear, as there has been no census since 2003.

Histo ...

, Haiti before steaming to New York, arriving there on 29 April. After touring the east coast in May, she departed for the canal, which she crossed on 12 June. She remained in Balboa until 12 June, at which point she left for San Pedro, arriving on 28 June. The ship spent the rest of 1927 with training, maintenance, and a tour of the west coast. She went to Puget Sound for a refit on 1 April 1928 that lasted until 16 May, after which she went to San Francisco. She left that same day, however, and steamed back north to visit Victoria, British Columbia

Victoria is the capital city of the Canadian province of British Columbia, on the southern tip of Vancouver Island off Canada's Pacific coast. The city has a population of 91,867, and the Greater Victoria area has a population of 397,237. T ...

. She remained there from 24 to 28 May and then returned to San Francisco. She spent June visiting various ports, and in August she embarked Dwight F. Davis

Dwight Filley Davis Sr. (July 5, 1879 – November 28, 1945) was an American tennis player and politician. He is best remembered as the founder of the Davis Cup international tennis competition. He was the Assistant Secretary of War from 1923 to ...

, the Secretary of War, in San Francisco; she carried him to Hawaii, departing on 7 August and arriving on the 13th. ''Pennsylvania'' returned to Seattle on 26 August.

Another cruise to Cuba took place in January 1929, after which she went to the Philadelphia Navy Yard

The Philadelphia Naval Shipyard was an important naval shipyard of the United States for almost two centuries.

Philadelphia's original navy yard, begun in 1776 on Front Street and Federal Street in what is now the Pennsport section of the ci ...

on 1 June for a major refit and modernization. She received a number of modifications, including increased deck and turret roof armor, anti-torpedo bulges, new turbo-generators, new turbines, and six new three-drum boilers. Her main battery turrets were modified to allow them to elevate to 30 degrees, significantly increasing the range of her guns, and her secondary battery was revised. The number of 5-inch guns was reduced to twelve, and her 3-inch anti-aircraft guns were replaced with eight 5-inch /25 guns. Her torpedo tubes were removed, as were her lattice mast

Lattice masts, or cage masts, or basket masts, are a type of observation mast common on United States Navy major warships in the early 20th century. They are a type of hyperboloid structure, whose weight-saving design was invented by the Russian ...

s, which were replaced with sturdier tripod masts. Her bridge was also enlarged to increase the space available for an admiral's staff, since she was used as a flagship. Her living space was increased to 2,037 crew and marines, and she was fitted with two catapults for seaplane

A seaplane is a powered fixed-wing aircraft capable of takeoff, taking off and water landing, landing (alighting) on water.Gunston, "The Cambridge Aerospace Dictionary", 2009. Seaplanes are usually divided into two categories based on their tec ...

s.

''Pennsylvania'' returned to service on 1 March 1931 and she conducted trials in Delaware Bay

Delaware Bay is the estuary outlet of the Delaware River on the northeast seaboard of the United States. It is approximately in area, the bay's freshwater mixes for many miles with the saltwater of the Atlantic Ocean.

The bay is bordered inla ...

in March and April. She then steamed south to Cuba on 8 May for a training cruise before returning to Philadelphia on 26 May. Another cruise to Cuba followed on 30 July; the ship arrived there on 5 August and this time she steamed across the Caribbean to the Panama Canal, which she transited on 12 August to return to the Battle Fleet. She reached San Pedro on 27 August, where she remained for the rest of the year. She toured the west coast in January 1932 and before crossing over to Pearl Harbor

Pearl Harbor is an American lagoon harbor on the island of Oahu, Hawaii, west of Honolulu. It was often visited by the Naval fleet of the United States, before it was acquired from the Hawaiian Kingdom by the U.S. with the signing of the ...

, where she arrived on 3 February. There, she took part in extensive fleet maneuvers as part of Fleet Problem XIII. She returned to San Pedro on 20 March, remaining there until 18 April, when she began another cruise along the coast of California. She returned to San Pedro on 14 November and remained there until the end of the year.

1932–1941

The ship departed San Pedro on 9 February to participate in

The ship departed San Pedro on 9 February to participate in Fleet Problem XIV The Fleet Problems are a series of naval exercises of the United States Navy conducted in the interwar period, and later resurrected by Pacific Fleet around 2014.

The first twenty-one Fleet Problems — labeled with roman numerals as Fleet Probl ...

, which lasted from 10 to 17 February. She returned to San Francisco on 17 February and then went to San Pedro on 27 February, remaining there until 19 June. Another west coast cruise followed from 19 June to 14 November, and after returning to San Pedro, ''Pennsylvania'' stayed there inactive until early March 1934. From 4 to 8 March, she made a short visit to Hunters Point Naval Shipyard

The Hunters Point Naval Shipyard was a United States Navy shipyard in San Francisco, California, located on of waterfront at Hunters Point in the southeast corner of the city.

Originally, Hunters Point was a commercial shipyard established in ...

in San Francisco and then returned to San Pedro. From there, she went to join the fleet for Fleet Problem XV, which was held in the Caribbean this year; she passed through the canal on 24 April, the maneuvers having already started on the 19th. They lasted until 12 May, at which point ''Pennsylvania'' went to Gonaïves with the rest of the fleet, which then continued on to New York, where it arrived on 31 March. There, ''Pennsylvania'' led the fleet in a naval review for now-President Franklin D. Roosevelt. On 15 June, Admiral Joseph M. Reeves took command of the fleet aboard ''Pennsylvania'', which was once again the fleet flagship.

On 18 June, ''Pennsylvania'' left New York for the Pacific, stopping in Hampton Roads on 20 June on the way. She passed through the canal on 28 June and reached San Pedro on 7 July. She then went to Puget Sound for a refit that lasted from 14 July to 2 October. The ship left the shipyard on 16 October and returned to San Francisco two days later, beginning a period of cruises off the coast of California and visits to cities in the state. She ended the year in San Pedro, remaining there or in San Francisco until 29 April 1935, when she took part in Fleet Problem XVI in the Hawaiian islands. The maneuvers lasted until 10 June, and were the largest set of exercises conducted by the US Navy at the time. The ship then returned to San Pedro on 17 June and embarked on a cruise of the west coast for several months; on 16 December, she went to Puget Sound for another overhaul that lasted from 20 December to 21 March 1936. Fleet Problem XVII The Fleet Problems are a series of naval exercises of the United States Navy conducted in the interwar period, and later resurrected by Pacific Fleet around 2014.

The first twenty-one Fleet Problems — labeled with roman numerals as Fleet Probl ...

followed from 27 April to 7 June, this time being held off Balboa. She returned to San Pedro on 6 June and spent the rest of the year with training exercises off the west coast and Hawaii, ending the training program for the year in San Pedro on 18 November.

The ship remained in port until 17 February, when she departed for San Clemente, California

San Clemente (; Spanish for " St. Clement") is a city in Orange County, California. Located in the Orange Coast region of the South Coast of California, San Clemente's population was 64,293 in at the 2020 census. Situated roughly midway betwe ...

at the start of a tour along the west coast. She participated in Fleet Problem XVIII, which lasted from 16 April to 28 May. Another stint in Puget Sound began on 6 June and concluded on 3 September, when she returned to San Pedro. She spent the rest of the year alternating between there and San Francisco, seeing little activity. She made a short trip to San Francisco in February 1938 and took part in Fleet Problem XIX The Fleet Problems are a series of naval exercises of the United States Navy conducted in the interwar period, and later resurrected by Pacific Fleet around 2014.

The first twenty-one Fleet Problems — labeled with roman numerals as Fleet Proble ...

from 9 March to 30 April. Another period in San Pedro followed until 20 June, after which she embarked on a two-month cruise along the west coast that concluded with another stay at Puget Sound on 28 September. After concluding her repairs on 16 December, she returned to San Pedro by way of San Francisco, arriving on 22 December. Fleet Problem XX occurred earlier the year than it had in previous iterations, taking place from 20 to 27 February 1939 in Cuban waters. During the exercises, Franklin Roosevelt and Admiral William D. Leahy, the CNO, came aboard ''Pennsylvania'' to observe the maneuvers.

The ship then went to Culebra on 27 February, departing on 4 March to visit Port-au-Prince, Haiti from 6 to 11 March. A stay in Guantanamo Bay followed from 12 to 31 March, after which she went to visit the US Naval Academy

The United States Naval Academy (US Naval Academy, USNA, or Navy) is a federal service academy in Annapolis, Maryland. It was established on 10 October 1845 during the tenure of George Bancroft as Secretary of the Navy. The Naval Academy is ...

in Annapolis on 5 April. ''Pennsylvania'' began the voyage back to the Pacific on 18 April and passed through the canal at the end of the month, ultimately arriving back in San Pedro on 12 May. Another tour of the west coast followed, which included stops in San Francisco, Tacoma, and Seattle, and ended in San Pedro on 20 October. She went to Hawaii to participate in Fleet Problem XXI The Fleet Problems are a series of naval exercises of the United States Navy conducted in the interwar period, and later resurrected by United States Pacific Fleet, Pacific Fleet around 2014.

The first twenty-one Fleet Problems — labeled with ro ...

on 2 April 1940. The exercises lasted until 17 May, after which the ship remained in Hawaii until 1 September, when she left for San Pedro. The battleship then went to Puget Sound on 12 September that lasted until 27 December; during the overhaul, she received another four 5-inch /25 guns. She returned to San Pedro on 31 December. Fleet Problem XXII The Fleet Problems are a series of naval exercises of the United States Navy conducted in the interwar period, and later resurrected by Pacific Fleet around 2014.

The first twenty-one Fleet Problems — labeled with roman numerals as Fleet Proble ...

was scheduled for January 1941, but the widening of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

by this time led the naval command to cancel the exercises. On 7 January, ''Pennsylvania'' steamed to Hawaii as part of what was again the Pacific Fleet, based at Pearl Harbor. Over the course of the year, she operated out of Pearl Harbor and made a short voyage to the west coast of the United States from 12 September to 11 October.

World War II

Attack on Pearl Harbor

On the morning of 7 December, ''Pennsylvania'' was in Dry Dock No. 1 in Pearl Harbor undergoing a refit; three of her fourscrews

A screw and a bolt (see '' Differentiation between bolt and screw'' below) are similar types of fastener typically made of metal and characterized by a helical ridge, called a ''male thread'' (external thread). Screws and bolts are used to f ...

were removed. The destroyers and were also in the dock with her. When it became clear that the port was under air attack from the Japanese fleet, ''Pennsylvania''s crew rushed to their battle stations, and between 08:02 and 08:05, her anti-aircraft gunners began engaging the hostile aircraft. Japanese torpedo bomber

A torpedo bomber is a military aircraft designed primarily to attack ships with aerial torpedoes. Torpedo bombers came into existence just before the First World War almost as soon as aircraft were built that were capable of carrying the weight ...

s unsuccessfully attempted to torpedo the side of the drydock to flood it; having failed, several aircraft then strafe

Strafing is the military practice of attacking ground targets from low-flying aircraft using aircraft-mounted automatic weapons.

Less commonly, the term is used by extension to describe high-speed firing runs by any land or naval craft such ...

d ''Pennsylvania''. At 08:30, several high-altitude bombers began a series of attacks on the ship; over the course of the following fifteen minutes, five aircraft attempted to hit her from different directions. One of the Japanese bombers hit ''Downes'' and one scored a hit on ''Pennsylvania'' that passed through the boat deck and exploded in casemate No. 9. ''Pennsylvania''s anti-aircraft gunners fired at all of these aircraft but failed to hit any of them, apparently owing to incorrect fuse settings that caused the shells to explode before they reached the correct altitude. The gunners did manage to shoot down a low-flying aircraft that attempted to strafe the ship; they claimed to have shot down another five aircraft, but the after-action investigation noted that only two aircraft were likely hit by ''Pennsylvania''s guns.

By 09:20, both destroyers were on fire from bomb hits and the fire had spread to ''Pennsylvania'', so the drydock was flooded to help contain the fire. Ten minutes later, the destroyers began to explode as the fires spread to ammunition magazines, and at 09:41, ''Downes'' was shattered by an explosion that scattered parts of the ship around the area. One of her torpedo tubes, weighing , was launched into the air, striking ''Pennsylvania''s forecastle

The forecastle ( ; contracted as fo'c'sle or fo'c's'le) is the upper deck of a sailing ship forward of the foremast, or, historically, the forward part of a ship with the sailors' living quarters. Related to the latter meaning is the phrase " b ...

. As part of her crew battled the fire in her bow, other men used the ship's boats to ferry anti-aircraft ammunition from stores in the West Loch of Pearl Harbor. Beginning at 14:00, the crew began preparatory work to repair the bomb damage; a 5-inch /25 gun and a 5-inch /51 casemate gun were taken from the damaged battleship to replace weapons damaged aboard ''Pennsylvania''. In the course of the attack, ''Pennsylvania'' had 15 men killed (including her executive officer), 14 missing, and 38 wounded. On 12 December, ''Pennsylvania'' was refloated and taken out of the drydock; having been only lightly damaged in the attack, she was ready to go to sea. She departed Pearl Harbor on 20 December and arrived in San Francisco nine days later. She went into drydock at Hunter's Point on 1 January 1942 for repairs that were completed on 12 January.

The ship left San Francisco on 20 February and began gunnery training before returning to San Francisco the next day. Further training followed in March, and from 14 April to 1 August, she took part in extensive maneuvers off the coast of California; during this period, she underwent an overhaul at the Mare Island Naval Shipyard

The Mare Island Naval Shipyard (MINSY) was the first United States Navy base established on the Pacific Ocean. It is located northeast of San Francisco in Vallejo, California. The Napa River goes through the Mare Island Strait and separates ...

in San Francisco. The work involved considerably strengthening the ship's anti-aircraft capabilities, with ten Bofors 40 mm quad mounts and fifty-one Oerlikon 20 mm

The Oerlikon 20 mm cannon is a series of autocannons, based on an original German Becker Type M2 20 mm cannon design that appeared very early in World War I. It was widely produced by Oerlikon Contraves and others, with various models em ...

single mounts. The tripod mainmast was removed, with the stump replaced by a deckhouse above which the aft main battery director cupola was housed. One of the new CXAM-1 radars was installed above the cupola. The older 5-inch /51 cal anti-ship guns in casemates and 5-inch /25 cal anti-aircraft guns were replaced with rapid fire 5-inch /38 cal guns in eight twin turret mounts. The new 5"/38 cal dual purpose guns could elevate to 85 degrees and fire at a rate of one round every four seconds. The ship briefly went to sea during the Battle of Midway

The Battle of Midway was a major naval battle in the Pacific Theater of World War II that took place on 4–7 June 1942, six months after Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor and one month after the Battle of the Coral Sea. The U.S. Navy under A ...

as part of Task Force 1

Task may refer to:

* Task (computing), in computing, a program execution context

* Task (language instruction) refers to a certain type of activity used in language instruction

* Task (project management), an activity that needs to be accomplished ...

, commanded by Vice Admiral William S. Pye, but the ships did not see action during the operation.

Aleutians and Makin Atoll

On 1 August, ''Pennsylvania'' left San Francisco, bound for Pearl Harbor. She arrived there on 14 August and took part in further training, including guard tactics for aircraft carrier task forces. Another overhaul followed in San Francisco from 3 to 10 January 1943. After further training and tests at San Francisco and

On 1 August, ''Pennsylvania'' left San Francisco, bound for Pearl Harbor. She arrived there on 14 August and took part in further training, including guard tactics for aircraft carrier task forces. Another overhaul followed in San Francisco from 3 to 10 January 1943. After further training and tests at San Francisco and Long Beach

Long Beach is a city in Los Angeles County, California. It is the 42nd-most populous city in the United States, with a population of 466,742 as of 2020. A charter city, Long Beach is the seventh-most populous city in California.

Incorporated ...

that lasted into April, she departed to join the Aleutian Islands Campaign on 23 April. She bombarded Holtz Bay and Chichagof Harbor on 11–12 May to support the forces that went ashore on the island of Attu. While she was leaving the area on the 12th, the Japanese submarine launched a torpedo at the ship, which was observed by a patrolling PBY Catalina

The Consolidated PBY Catalina is a flying boat and amphibious aircraft that was produced in the 1930s and 1940s. In Canadian service it was known as the Canso. It was one of the most widely used seaplanes of World War II. Catalinas served w ...

flying boat. The Catalina radioed ''Pennsylvania'', which took evasive maneuvers and escaped unharmed; a pair of destroyers then spent the next ten hours hunting the submarine before severely damaging her and forcing her to surface. ''I-31'' was later sunk by another destroyer the next day.

''Pennsylvania'' returned to Holtz Bay on 14 May to conduct another bombardment in support of an infantry attack on the western side of the bay. She continued operations in the area until 19 May, when she steamed to Adak Island

Adak Island ( ale, Adaax, russian: Адак) or Father Island is an island near the western extent of the Andreanof Islands group of the Aleutian Islands in Alaska. Alaska's southernmost town, Adak, Alaska, Adak, is located on the island. The isl ...

for another amphibious assault. While en route, one of her gasoline stowage compartments exploded, which caused structural damage, though no one was injured in the accident. She was forced to leave Adak on 21 May for repairs at Puget Sound that lasted from 31 May to 15 June; during the overhaul, another accidental explosion killed one man and injured a second. She left port on 1 August, bound for Adak, which she reached on 7 August. There, she became the flagship of Admiral Francis W. Rockwell, commander of the task force that was to attack Kiska

Kiska ( ale, Qisxa, russian: Кыска) is one of the Rat Islands, a group of the Aleutian Islands of Alaska. It is about long and varies in width from . It is part of Aleutian Islands Wilderness and as such, special permission is requir ...

. The troops went ashore on 15 August but met no resistance, the Japanese having evacuated without US forces in the area having becoming aware of it. ''Pennsylvania'' patrolled off Kiska for several days before returning to Adak on 23 August.

Two days later, the battleship departed Adak for Pearl Harbor, arriving there on 1 September. She embarked a contingent of 790 passengers before steaming on 19 September, bound for San Francisco. She arrived there six days later and debarked her passengers before returning to Pearl Harbor on 6 October to take part in bombardment training from 20 to 23 October and 31 October – 4 November. Now the flagship of Rear Admiral Richmond K. Turner, the commander of the Fifth Amphibious Force, itself part of the Northern Attack Force, ''Pennsylvania'' left Pearl Harbor on 10 November to lead the assault on Makin Atoll

Butaritari is an atoll in the Pacific Ocean island nation of Kiribati. The atoll is roughly four-sided. The south and southeast portion of the atoll comprises a nearly continuous islet. The atoll reef is continuous but almost without islets al ...

, part of the Gilbert Islands

The Gilbert Islands ( gil, Tungaru;Reilly Ridgell. ''Pacific Nations and Territories: The Islands of Micronesia, Melanesia, and Polynesia.'' 3rd. Ed. Honolulu: Bess Press, 1995. p. 95. formerly Kingsmill or King's-Mill IslandsVery often, this n ...

. She was joined by three other battleships, four cruisers, three escort carriers, and numerous transports and destroyers; they arrived off Makin on 20 November, and ''Pennsylvania'' opened fire on Butaritari Island that morning at a range of , beginning the Battle of Makin

The Battle of Makin was an engagement of the Pacific campaign of World War II, fought from 20 to 24 November 1943, on Makin Atoll in the Gilbert Islands.

Background

Japanese invasion and fortification

On 10 December 1941, three days after the ...

. Early on the morning of 24 November, the ship was rocked by an explosion off her starboard bow; lookouts reported that the escort carrier had been torpedoed and had exploded. Japanese torpedo bombers conducted repeated nighttime attacks on 25 and 26 November, but they failed to score any hits on the American fleet. ''Pennsylvania'' left the area on 30 November to return to Pearl Harbor.

Marshalls and Marianas campaigns

At the start of 1944, ''Pennsylvania'' was at Pearl Harbor; over the course of the first two weeks of January, she took part in maneuvers in preparation for landings onKwajalein

Kwajalein Atoll (; Marshallese language, Marshallese: ) is part of the Marshall Islands, Republic of the Marshall Islands (RMI). The southernmost and largest island in the atoll is named Kwajalein Island, which its majority English-speaking res ...

in the Marshall Islands

The Marshall Islands ( mh, Ṃajeḷ), officially the Republic of the Marshall Islands ( mh, Aolepān Aorōkin Ṃajeḷ),'' () is an independent island country and microstate near the Equator in the Pacific Ocean, slightly west of the Internati ...

. She departed Pearl Harbor on 22 January in company with the invasion fleet, and on 31 January she began her preparatory bombardment of the atoll to start the Battle of Kwajalein. Troops went ashore the next day, and ''Pennsylvania'' remained offshore to provide artillery support to the marines as they fought to secure the island. By the evening of 3 February, the Japanese defenders had been defeated, allowing the ship to depart to Majuro Atoll to replenish her ammunition supply. She left shortly thereafter, on 12 February, to support the next major attack on Eniwetok

Enewetak Atoll (; also spelled Eniwetok Atoll or sometimes Eniewetok; mh, Ānewetak, , or , ; known to the Japanese as Brown Atoll or Brown Island; ja, ブラウン環礁) is a large coral atoll of 40 islands in the Pacific Ocean and with ...

in the Marshalls; five days later she arrived off the island, the Battle of Eniwetok already underway, and over the course of 20 and 21 February, she shelled the island heavily to support the men fighting ashore. On 22 February, she supported the landing on Parry Island, part of the Eniwetok atoll.

On 1 March, ''Pennsylvania'' steamed back to Majuro before proceeding south to Havannah Harbor on Efate Island in the New Hebrides

New Hebrides, officially the New Hebrides Condominium (french: link=no, Condominium des Nouvelles-Hébrides, "Condominium of the New Hebrides") and named after the Hebrides Scottish archipelago, was the colonial name for the island group ...

. She remained there until 24 April, when she left for a short visit to Sydney, Australia from 29 April to 11 May, when she returned to Efate. She thereafter steamed to Port Purvis on Florida Island

The Nggela Islands, also known as the Florida Islands, are a small island group in the Central Province of Solomon Islands, a sovereign state (since 1978) in the southwest Pacific Ocean.

The chain is composed of four larger islands and about ...

, in the Solomons, to participate in amphibious assault exercises. After replenishing ammunition and supplies at Efate, she left on 2 June, bound for Roi, arriving there six days later. On 10 June, she joined a force of battleships, cruisers, escort carriers, and destroyers that had assembled for the Marianas campaign

The Mariana and Palau Islands campaign, also known as Operation Forager, was an offensive launched by United States forces against Imperial Japanese forces in the Mariana Islands and Palau in the Pacific Ocean between June and November 1944 dur ...

. While en route that night, one of the escorting destroyers reported a sonar

Sonar (sound navigation and ranging or sonic navigation and ranging) is a technique that uses sound propagation (usually underwater, as in submarine navigation) to navigate, measure distances ( ranging), communicate with or detect objects on ...

contact and the ships of the fleet took evasive maneuvers; in the darkness, ''Pennsylvania'' accidentally collided with the troop transport

A troopship (also troop ship or troop transport or trooper) is a ship used to carry soldiers, either in peacetime or wartime. Troopships were often drafted from commercial shipping fleets, and were unable land troops directly on shore, typicall ...

. ''Pennsylvania'' incurred only minor damage and was able to continue with the fleet, but ''Talbot'' had to return to Eniwetok for emergency repairs.

''Pennsylvania'' began her bombardment of Saipan

Saipan ( ch, Sa’ipan, cal, Seipél, formerly in es, Saipán, and in ja, 彩帆島, Saipan-tō) is the largest island of the Northern Mariana Islands, a commonwealth of the United States in the western Pacific Ocean. According to 2020 est ...

on 14 June to prepare the island for the assault that came the next day. She continued shelling the island while cruising off Tinian

Tinian ( or ; old Japanese name: 天仁安島, ''Tenian-shima'') is one of the three principal islands of the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands. Together with uninhabited neighboring Aguiguan, it forms Tinian Municipality, one of t ...

on 15 June as the assault craft went ashore. On 16 June, she attacked Japanese positions at Orote Point

Point Udall, also called Orote Point, is the westernmost point (by travel, not longitude) in the territorial United States, located on the Orote Peninsula of Guam. It lies at the mouth of Apra Harbor, on the end of Orote Peninsula, opposite the ...

on Guam

Guam (; ch, Guåhan ) is an organized, unincorporated territory of the United States in the Micronesia subregion of the western Pacific Ocean. It is the westernmost point and territory of the United States (reckoned from the geographic ce ...

before returning to Saipan. She left the area on 25 June to replenish at Eniwetok, returning to join the preparatory bombardment of Guam on 12 July. The shelling continued for two days, and late on 14 July, she steamed to Saipan to again replenish her ammunition. Back on station three days later, she continued to blast the island through 20 July. This work also included suppressing guns that fired on demolition parties that went ashore to destroy landing obstacles. On the morning of 21 July, ''Pennsylvania'' took up her bombardment position off Orote Point as the assault craft prepared to launch their attack. The ship operated off the island supporting the men fighting there for the next two weeks.

Operations in the Philippines

''Pennsylvania'' left Guam on 3 August to replenish at Eniwetok, arriving there on 19 August. From there, she steamed toEspiritu Santo

Espiritu Santo (, ; ) is the largest island in the nation of Vanuatu, with an area of and a population of around 40,000 according to the 2009 census.

Geography

The island belongs to the archipelago of the New Hebrides in the Pacific region ...

in the New Hebrides before joining landing training off Guadalcanal

Guadalcanal (; indigenous name: ''Isatabu'') is the principal island in Guadalcanal Province of Solomon Islands, located in the south-western Pacific, northeast of Australia. It is the largest island in the Solomon Islands by area, and the se ...

. The ship left on 6 September as part of the Bombardment and Fire Support Group for the invasion of Peleliu

The Battle of Peleliu, codenamed Operation Stalemate II by the US military, was fought between the United States and Japan during the Mariana and Palau Islands campaign of World War II, from September 15 to November 27, 1944, on the island of ...

. She bombarded the island from 12 to 14 September and supported the landings the next day. She shelled Anguar Island on 17 September and remained there for three days, departing on 20 September. She then steamed to Seeadler Harbor on Manus

Manus may refer to:

* Manus (anatomy), the zoological term for the distal portion of the forelimb of an animal (including the human hand)

* ''Manus'' marriage, a type of marriage during Roman times

Relating to locations around New Guinea

* Man ...

, one of the Admiralty Islands

The Admiralty Islands are an archipelago group of 18 islands in the Bismarck Archipelago, to the north of New Guinea in the South Pacific Ocean. These are also sometimes called the Manus Islands, after the largest island.

These rainforest-co ...

for repairs. On 28 September, she arrived there and entered a floating dry dock on 1 October for a week's repairs. ''Pennsylvania'' left on 12 October in company with the battleships , , , , and ''West Virginia'', under the command of Rear Admiral Jesse B. Oldendorf

Jesse Barrett "Oley" Oldendorf (16 February 1887 – 27 April 1974) was an admiral in the United States Navy, famous for defeating a Japanese force in the Battle of Leyte Gulf during World War II. He also served as commander of the American naval ...

. These ships, designated Task Group 77.2

Task may refer to:

* Task (computing), in computing, a program execution context

* Task (language instruction) refers to a certain type of activity used in language instruction

* Task (project management), an activity that needs to be accomplishe ...

, formed the Fire Support Group for the upcoming operations in the Philippines. They arrived off Leyte

Leyte ( ) is an island in the Visayas group of islands in the Philippines. It is eighth-largest and sixth-most populous island in the Philippines, with a total population of 2,626,970 as of 2020 census.

Since the accessibility of land has be ...

on 18 October and took up bombardment positions; over the next four days, they covered Underwater Demolition Team

Underwater Demolition Teams (UDT), or frogmen, were amphibious units created by the United States Navy during World War II with specialized non-tactical missions. They were predecessors of the navy's current SEAL teams.

Their primary WWII func ...

s, beach reconnaissance operations, and minesweeper

A minesweeper is a small warship designed to remove or detonate naval mines. Using various mechanisms intended to counter the threat posed by naval mines, minesweepers keep waterways clear for safe shipping.

History

The earliest known usage of ...

s clearing the way for the landing force.

On 24 October, reports of Japanese naval forces approaching the area led Oldendorf's ships to prepare for action at the exit of the Surigao Strait

Surigao Strait (Filipino: ''Kipot ng Surigaw'') is a strait in the southern Philippines, between the Bohol Sea and the Leyte Gulf of the Philippine Sea.

Geography

It is located between the regions of Visayas and Mindanao. It lies between northern ...

. Vice Admiral Shōji Nishimura

was an admiral in the Imperial Japanese Navy during World War II.

Biography

Nishimura was from Akita prefecture in the northern Tōhoku region of Japan. He was a graduate of the 39th class of the Imperial Japanese Naval Academy in 1911, ranking ...

's Southern Force steamed through the Surigao Strait to attack the invasion fleet in Leyte Gulf

Leyte Gulf is a gulf in the Eastern Visayan region in the Philippines. The bay is part of the Philippine Sea of the Pacific Ocean, and is bounded by two islands; Samar in the north and Leyte in the west. On the south of the bay is Mindana ...

; his force comprised Battleship Division 2—the battleships and , the heavy cruiser

The heavy cruiser was a type of cruiser, a naval warship designed for long range and high speed, armed generally with naval guns of roughly 203 mm (8 inches) in caliber, whose design parameters were dictated by the Washington Naval ...

, and four destroyers—and Vice Admiral Kiyohide Shima

was an admiral in the Imperial Japanese Navy during World War II.

Biography

A native of Miyazaki prefecture, Shima was a graduate of the 39th class of the Imperial Japanese Naval Academy in 1911, ranking 69th out of 148 cadets. As a midshipman, h ...