USS Hobson on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

USS ''Hobson'' (DD-464/DMS-26), a , was the only ship of the

''Hobson'' was pennant of Destroyer Division 20 (DesDiv 20), composed of , and that along with Destroyer Division 19 made up Destroyer Squadron 10 (DesRon 10), with its pennant on ; Destroyer Flotilla Four, with its flag on ; Destroyers, Atlantic Fleet. Following extensive shakedown and training operations in

''Hobson'' was pennant of Destroyer Division 20 (DesDiv 20), composed of , and that along with Destroyer Division 19 made up Destroyer Squadron 10 (DesRon 10), with its pennant on ; Destroyer Flotilla Four, with its flag on ; Destroyers, Atlantic Fleet. Following extensive shakedown and training operations in

As the

As the

For some time the Allies had been building up tremendous strength in

For some time the Allies had been building up tremendous strength in  The German shore batteries, having discovered the Allied invaders, began firing on the armada at 0530. At 0536, the group commander made the signal "Commence counter battery bombardment.", 14 minutes ahead of schedule. ''Hobson'' and the other ships began counter-firing as spent 5" and 8" shell casings littered their decks. Only the heavy ships had planes to spot for them. The destroyers were close enough to see their targets which consisted mostly of "strong points" just back of the beaches. ''Hobson'', at station 1, was assigned firing on targets 70 and 72. At 0629, ''Hobson'' observed shell splashes near and at 0633, ''Corry'' appeared to be hit amidships. As smoke from the intense shore firing drifted offshore and temporarily concealed ''Corry'', ''Hobson'' shifted her fire at 0638 to target 86 which appeared to have been firing on ''Corry''. This battery temporarily ceased firing as soon as taken under fire by ''Hobson''. At 0644, the destroyer shifted her fire back to targets 70 and 72 since the leading boat wave was close to shore and neutralization of German firing from those areas was vital. At 0656, the smoke was extremely heavy on the beach, making it difficult to see the targets, and ''Hobson'', per her prior firing orders, estimated that the first troops were going ashore and shifted fire to target 74, which was in an excellent position to deliver deadly enfilade and strafing fire on the Allied landing troops. At 0700, the smoke cover was clearing from ''Corry'' and the men on ''Hobson'' could see she was "in definite trouble with her back broken between the stacks" as targets 13A and 86 fired on the stricken destroyer. ''Corry'', the worst naval loss of the D-Day landings, was hit by the

The German shore batteries, having discovered the Allied invaders, began firing on the armada at 0530. At 0536, the group commander made the signal "Commence counter battery bombardment.", 14 minutes ahead of schedule. ''Hobson'' and the other ships began counter-firing as spent 5" and 8" shell casings littered their decks. Only the heavy ships had planes to spot for them. The destroyers were close enough to see their targets which consisted mostly of "strong points" just back of the beaches. ''Hobson'', at station 1, was assigned firing on targets 70 and 72. At 0629, ''Hobson'' observed shell splashes near and at 0633, ''Corry'' appeared to be hit amidships. As smoke from the intense shore firing drifted offshore and temporarily concealed ''Corry'', ''Hobson'' shifted her fire at 0638 to target 86 which appeared to have been firing on ''Corry''. This battery temporarily ceased firing as soon as taken under fire by ''Hobson''. At 0644, the destroyer shifted her fire back to targets 70 and 72 since the leading boat wave was close to shore and neutralization of German firing from those areas was vital. At 0656, the smoke was extremely heavy on the beach, making it difficult to see the targets, and ''Hobson'', per her prior firing orders, estimated that the first troops were going ashore and shifted fire to target 74, which was in an excellent position to deliver deadly enfilade and strafing fire on the Allied landing troops. At 0700, the smoke cover was clearing from ''Corry'' and the men on ''Hobson'' could see she was "in definite trouble with her back broken between the stacks" as targets 13A and 86 fired on the stricken destroyer. ''Corry'', the worst naval loss of the D-Day landings, was hit by the

USS EMMONS (DD457-DMS22) (2005), p. 275-280 USS Emmons Assoc.

/ref> The landing areas for

USS EMMONS (DD457-DMS22) (2005), p. 275-280 USS Emmons Assoc.

/ref> ''Hobson'' and several others in the squadron sailed on 4 January 1945 via the

Hobson-Wasp Collision Collection, 1952–1953 MS 245

held by Special Collection & Archives, Nimitz Library at the United States Naval Academy * {{DEFAULTSORT:Hobson Hobson (DD-464) Hobson (DD-464) Ships built in Charleston, South Carolina World War II shipwrecks in the Atlantic Ocean Ships sunk in collisions 1941 ships Hobson (DD-464) Maritime incidents in 1952

United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

to be named for Richmond Pearson Hobson, who was awarded the Medal of Honor

The Medal of Honor (MOH) is the United States Armed Forces' highest military decoration and is awarded to recognize American soldiers, sailors, marines, airmen, guardians and coast guardsmen who have distinguished themselves by acts of valor. ...

for actions during the Spanish–American War

, partof = the Philippine Revolution, the decolonization of the Americas, and the Cuban War of Independence

, image = Collage infobox for Spanish-American War.jpg

, image_size = 300px

, caption = (clock ...

. He would later in his career attain the rank of rear admiral

Rear admiral is a senior naval flag officer rank, equivalent to a major general and air vice marshal and above that of a commodore and captain, but below that of a vice admiral. It is regarded as a two star "admiral" rank. It is often regarde ...

and go on to serve as a congressman

A Member of Congress (MOC) is a person who has been appointed or elected and inducted into an official body called a congress, typically to represent a particular constituency in a legislature. The term member of parliament (MP) is an equivalen ...

from the state of Alabama

(We dare defend our rights)

, anthem = "Alabama (state song), Alabama"

, image_map = Alabama in United States.svg

, seat = Montgomery, Alabama, Montgomery

, LargestCity = Huntsville, Alabama, Huntsville

, LargestCounty = Baldwin County, Al ...

.

''Hobson'', constructed at a cost of $5 million, was launched at the Charleston Navy Yard

Charleston Naval Shipyard (formerly known as the Charleston Navy Yard) was a U.S. Navy ship building and repair facility located along the west bank of the Cooper River, in North Charleston, South Carolina and part of Naval Base Charleston.

H ...

on 8 September 1941; sponsored by Mrs. Grizelda Hobson, widow of Rear Admiral Hobson. As the new destroyer slid down the ways, she was cheered on by spectators and whistle blasts from other vessels on the Cooper River. ''Hobson'' was commissioned on 22 January 1942.

In 1952, ''Hobson'' collided with the aircraft carrier and sank with the loss of 176 crew. The ships had been undertaking amphibious exercises in the Atlantic, with ''Wasp'' practicing night flying, when ''Hobson'' attempted to turn in front of the carrier and collided with ''Wasp''. ''Hobson'' was broken in two and quickly sunk, causing the greatest loss of life on a US Navy ship since World War II.

Service prior to D-day

''Hobson'' was pennant of Destroyer Division 20 (DesDiv 20), composed of , and that along with Destroyer Division 19 made up Destroyer Squadron 10 (DesRon 10), with its pennant on ; Destroyer Flotilla Four, with its flag on ; Destroyers, Atlantic Fleet. Following extensive shakedown and training operations in

''Hobson'' was pennant of Destroyer Division 20 (DesDiv 20), composed of , and that along with Destroyer Division 19 made up Destroyer Squadron 10 (DesRon 10), with its pennant on ; Destroyer Flotilla Four, with its flag on ; Destroyers, Atlantic Fleet. Following extensive shakedown and training operations in Casco Bay

Casco Bay is an inlet of the Gulf of Maine on the southern coast of Maine, New England, United States. Its easternmost approach is Cape Small and its westernmost approach is Two Lights in Cape Elizabeth. The city of Portland sits along its south ...

, Maine

Maine () is a state in the New England and Northeastern regions of the United States. It borders New Hampshire to the west, the Gulf of Maine to the southeast, and the Canadian provinces of New Brunswick and Quebec to the northeast and north ...

, the new destroyer under command of Lt. Cdr. Kenneth Loveland and her sister ships

A sister ship is a ship of the same class or of virtually identical design to another ship. Such vessels share a nearly identical hull and superstructure layout, similar size, and roughly comparable features and equipment. They often share a ...

of Desdiv 20 joined veteran aircraft carrier

An aircraft carrier is a warship that serves as a seagoing airbase, equipped with a full-length flight deck and facilities for carrying, arming, deploying, and recovering aircraft. Typically, it is the capital ship of a fleet, as it allows a ...

at Norfolk, Virginia

Norfolk ( ) is an independent city in the Commonwealth of Virginia in the United States. Incorporated in 1705, it had a population of 238,005 at the 2020 census, making it the third-most populous city in Virginia after neighboring Virginia Be ...

, and sailed on 1 July 1942 to escort her to Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia in both cases. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of Earth's total surface area ...

. Carrying a vital cargo of 72 P-40 aircraft, ''Ranger'' arrived safely via Trinidad

Trinidad is the larger and more populous of the two major islands of Trinidad and Tobago. The island lies off the northeastern coast of Venezuela and sits on the continental shelf of South America. It is often referred to as the southernmos ...

, unloaded the planes and returned with Desdiv 20 on 5 August 1942. ''Hobson'' then conducted training exercises off Newport, Rhode Island

Newport is an American seaside city on Aquidneck Island in Newport County, Rhode Island. It is located in Narragansett Bay, approximately southeast of Providence, Rhode Island, Providence, south of Fall River, Massachusetts, south of Boston, ...

, and Norfolk until 3 October 1942, when she departed Norfolk for Bermuda

)

, anthem = "God Save the King"

, song_type = National song

, song = " Hail to Bermuda"

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, mapsize2 =

, map_caption2 =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name =

, e ...

on escort duty.

Operation Torch, the Invasion of North Africa

As the

As the Allies

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

prepared to land in North Africa

North Africa, or Northern Africa is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region, and it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of Mauritania in ...

, ''Hobson'', the three other destroyers of DesDiv 20 and ''Ellyson'' as destroyer flag under Capt. J.L. Holloway, joined Task Group 34.2 Airgroup under Rear Admiral Ernest D. McWhorter, composed of ''Ranger'', Sangamon-class escort carrier

The ''Sangamon'' class were a group of four escort aircraft carriers of the United States Navy that served during World War II.

Overview

These ships were originally oilers, launched in 1939 for civilian use. They were acquired and commissioned ...

, light cruiser , two submarines and a fleet oiler. The group was part of Task Force 34, Western Naval Task Force- Morocco, under Rear Admiral

Rear admiral is a senior naval flag officer rank, equivalent to a major general and air vice marshal and above that of a commodore and captain, but below that of a vice admiral. It is regarded as a two star "admiral" rank. It is often regarde ...

Henry Kent Hewitt

Henry Kent Hewitt (February 11, 1887 – September 15, 1972) was the United States Navy commander of amphibious operations in north Africa and southern Europe through World War II. He was born in Hackensack, New Jersey and graduated from the Unit ...

, flag on the cruiser

A cruiser is a type of warship. Modern cruisers are generally the largest ships in a fleet after aircraft carriers and amphibious assault ships, and can usually perform several roles.

The term "cruiser", which has been in use for several hu ...

. The Allies organized three amphibious task forces to seize the key ports and airports of Vichy French

Vichy France (french: Régime de Vichy; 10 July 1940 – 9 August 1944), officially the French State ('), was the fascist French state headed by Marshal Philippe Pétain during World War II. Officially independent, but with half of its terr ...

-controlled Morocco

Morocco (),, ) officially the Kingdom of Morocco, is the westernmost country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It overlooks the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Atlantic Ocean to the west, and has land borders with Algeria to ...

and Algeria

)

, image_map = Algeria (centered orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Algiers

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, relig ...

simultaneously, targeting Casablanca

Casablanca, also known in Arabic as Dar al-Bayda ( ar, الدَّار الْبَيْضَاء, al-Dār al-Bayḍāʾ, ; ber, ⴹⴹⴰⵕⵍⴱⵉⴹⴰ, ḍḍaṛlbiḍa, : "White House") is the largest city in Morocco and the country's econom ...

, Oran

Oran ( ar, وَهران, Wahrān) is a major coastal city located in the north-west of Algeria. It is considered the second most important city of Algeria after the capital Algiers, due to its population and commercial, industrial, and cultural ...

and Algiers. Successful completion of these operations was to be followed by an advance eastwards into Tunisia.

The Western Task Force (aimed at Casablanca) was composed of American army forces under the command of Major General

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of a ...

George S. Patton

George Smith Patton Jr. (November 11, 1885 – December 21, 1945) was a general in the United States Army who commanded the Seventh United States Army in the Mediterranean Theater of World War II, and the Third United States Army in France ...

and Rear Admiral Hewitt heading the naval operations. The army units consisted of the U.S. 2nd Armored Division

The 2nd Armored Division ("Hell on Wheels") was an armored division of the United States Army. The division played important roles during World War II in the invasions of Germany, North Africa, and Sicily and in the liberation of France, Belgium ...

and the U.S. 3rd

Third or 3rd may refer to:

Numbers

* 3rd, the ordinal form of the cardinal number 3

* , a fraction of one third

* Second#Sexagesimal divisions of calendar time and day, 1⁄60 of a ''second'', or 1⁄3600 of a ''minute''

Places

* 3rd Street (d ...

and 9th Infantry Divisions—35,000 troops in a convoy of over 100 ships. They were transported directly from the United States in the first of a new series of UG convoys

The UG convoys were a series of east-bound trans-Atlantic convoys from the United States to Gibraltar carrying food, ammunition, and military hardware to the United States Army in North Africa and southern Europe during World War II. These con ...

providing logistic support for the North African campaign. ''Hobson'' and the other four destroyers' main job was to screen and protect ''Ranger'' while the carrier's mobile air power supported the army's assault at Casablanca. Departing from Bermuda on 25 October 1942, ''Hobson''s group arrived off Fedhala

Mohammedia ( ar, المحمدية, al-muḥammadiyya; ber, ⴼⴹⴰⵍⴰ, Fḍala), known until 1960 as Fedala, is a port city on the west coast of Morocco between Casablanca and Rabat in the region of Casablanca-Settat. It hosts the most impo ...

on 8 November 1942. As the Operation Torch

Operation Torch (8 November 1942 – Run for Tunis, 16 November 1942) was an Allies of World War II, Allied invasion of French North Africa during the Second World War. Torch was a compromise operation that met the British objective of secu ...

landings proceeded, the air group provided indispensable air support, launching 496 combat sorties in the three-day operation. ''Ranger''s planes hit shore batteries, the immobile Vichy French

Vichy France (french: Régime de Vichy; 10 July 1940 – 9 August 1944), officially the French State ('), was the fascist French state headed by Marshal Philippe Pétain during World War II. Officially independent, but with half of its terr ...

battleship

A battleship is a large armored warship with a main battery consisting of large caliber guns. It dominated naval warfare in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The term ''battleship'' came into use in the late 1880s to describe a type of ...

, and later helped turn back the attack by French ships on the transport area in the Naval Battle of Casablanca

The Naval Battle of Casablanca was a series of naval engagements fought between United States Navy, American ships covering the Operation Torch, invasion of North Africa and Vichy France, Vichy French ships defending the Neutrality (international ...

. As ''Ranger''s planes were attacking ''Jean Bart'' on D-Day Plus 2 (10 November), the French submarine ''Le Tonnant'' fired four torpedoes at the carrier which passed harmlessly astern. At 1010, ''Ellyson'' spotted a periscope and dropped a full barrage of depth charges on sight at shallow setting. As ''Ranger'' turned to port, ''Hobson'' dropped another full pattern at deep setting. Capt. Holloway later wrote, "I am convinced that this fortunate sight contact by ''Ellyson'' saved ''Ranger'' from torpedo attack at closer range." Casablanca capitulated to the American forces on 11 November 1942 and ''Ranger'' departed the Moroccan coast 12 November, returning to Norfolk on the 23d. ''Hobson'' screened ''Ranger'' until she sailed for Norfolk, leaving the Allies fully in command of the assault area.

Atlantic Convoy Duty

Upon her return to Norfolk on 27 November 1942, the destroyer took part in exercises in Casco Bay, later steaming with a convoy to thePanama Canal Zone

The Panama Canal Zone ( es, Zona del Canal de Panamá), also simply known as the Canal Zone, was an unincorporated territory of the United States, located in the Isthmus of Panama, that existed from 1903 to 1979. It was located within the terr ...

in December. ''Hobson'' and DesDiv 20 again joined ''Ranger'' in early 1943 and the anti-submarine

An anti-submarine weapon (ASW) is any one of a number of devices that are intended to act against a submarine and its crew, to destroy (sink) the vessel or reduce its capability as a weapon of war. In its simplest sense, an anti-submarine weapo ...

group sailed on 8 January 1943 to patrol the western Atlantic. Groups such as ''Ranger''s did much to protect Allied

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

shipping in the Atlantic from U-boat

U-boats were naval submarines operated by Germany, particularly in the First and Second World Wars. Although at times they were efficient fleet weapons against enemy naval warships, they were most effectively used in an economic warfare role ...

s, and contributed to the eventual victory in Europe. Typical of ''Hobson''s versatile performance was her rescue off Bermuda

)

, anthem = "God Save the King"

, song_type = National song

, song = " Hail to Bermuda"

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, mapsize2 =

, map_caption2 =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name =

, e ...

of 45 survivors from the British merchantman on 2 March 1943. The freighter had been torpedoed and sunk four days earlier by the German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ger ...

submarine and the no. 3 lifeboat

Lifeboat may refer to:

Rescue vessels

* Lifeboat (shipboard), a small craft aboard a ship to allow for emergency escape

* Lifeboat (rescue), a boat designed for sea rescues

* Airborne lifeboat, an air-dropped boat used to save downed airmen

A ...

with 35 crew and passengers, under a red sail and towing a liferaft

A lifeboat or liferaft is a small, rigid or inflatable boat carried for emergency evacuation in the event of a disaster aboard a ship. Lifeboat drills are required by law on larger commercial ships. Rafts (liferafts) are also used. In the mil ...

holding 10 more crewmen, had sailed 93 nautical miles southwest of the sinking, when it was spotted by ''Ranger''s aircraft at 0745 hours. ''Hobson'' thereafter broke from the destroyer screen to investigate. The destroyer picked up the survivors at 1003 and the lifeboat and raft were sunk by gunfire from the ship. The ''St Margaret'' survivors were landed at Bermuda on Friday 5 March, where the crew were put on board an HM ship on 15 March and were landed at Portsmouth, England, seven days later.

In April 1943, ''Hobson'' and ''Ranger'' arrived at Naval Station Argentia, Newfoundland

Newfoundland and Labrador (; french: Terre-Neuve-et-Labrador; frequently abbreviated as NL) is the easternmost province of Canada, in the country's Atlantic region. The province comprises the island of Newfoundland and the continental region ...

, and began operations out of that base. The ships provided air cover for convoys and anti-submarine patrol, and in July 1943 had the honor of convoying , carrying Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is not ...

Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 Winston Churchill in the Second World War, dur ...

to the Quebec Conference. The veteran destroyer arrived in Boston 27 July 1943 to prepare for new duties.

Operation Leader, Bodø, Norway

''Hobson'' sailed with ''Ranger'' and other ships 5 August 1943 to join the British Home Fleet atScapa Flow

Scapa Flow viewed from its eastern end in June 2009

Scapa Flow (; ) is a body of water in the Orkney Islands, Scotland, sheltered by the islands of Mainland, Graemsay, Burray,S. C. George, ''Jutland to Junkyard'', 1973. South Ronaldsay and ...

. Arriving 19 August, she operated under Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

orders in northern waters, helping to provide cover for vital supply convoys to Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia, Northern Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the ...

. While at Scapa Flow, she was inspected by US Secretary of the Navy

The secretary of the Navy (or SECNAV) is a statutory officer () and the head (chief executive officer) of the Department of the Navy, a military department (component organization) within the United States Department of Defense.

By law, the sec ...

Frank Knox

William Franklin Knox (January 1, 1874 – April 28, 1944) was an American politician, newspaper editor and publisher. He was also the Republican vice presidential candidate in 1936, and Secretary of the Navy under Franklin D. Roosevelt during ...

and Admiral

Admiral is one of the highest ranks in some navies. In the Commonwealth nations and the United States, a "full" admiral is equivalent to a "full" general in the army or the air force, and is above vice admiral and below admiral of the fleet, ...

Harold Rainsford Stark on 21 September. ''Hobson'' and DesDiv 20 along with ''Ranger'' and the heavy cruisers and formed a task force under the command of Rear Admiral Olaf M. Hustvedt

Vice Admiral (United States), Vice Admiral Olaf Mandt Hustvedt (23 June 1886 – 22 December 1978) was a senior officer of the United States Navy. He saw service in World War I and World War II, operating in both the Battle of the Atlantic and th ...

that executed Operation Leader

Operation Leader was an air attack conducted against German shipping in the vicinity of Bodø, Norway, on 4 October 1943, during World War II. The raid was executed by aircraft flying from the United States Navy aircraft carrier , which was at ...

, a daring raid of combined British and American naval forces on 2–4 October 1943, when ''Ranger''s air wing

In military aviation, a wing is a unit of command. In most military aviation services, a wing is a relatively large formation of planes. In Commonwealth countries a wing usually comprises three squadrons, with several wings forming a group ( ...

of dive bombers

A dive bomber is a bomber aircraft that dives directly at its targets in order to provide greater accuracy for the bomb it drops. Diving towards the target simplifies the bomb's trajectory and allows the pilot to keep visual contact throughou ...

, torpedo bombers and fighters

Fighter(s) or The Fighter(s) may refer to:

Combat and warfare

* Combatant, an individual legally entitled to engage in hostilities during an international armed conflict

* Fighter aircraft, a warplane designed to destroy or damage enemy warplan ...

staged a devastating attack on German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ger ...

shipping at Bodø

Bodø (; smj, Bådåddjo, sv, Bodö) is a municipality in Nordland county, Norway. It is part of the traditional region of Salten. The administrative centre of the municipality is the town of Bodø (which is also the capital of Nordland count ...

, Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic country in Northern Europe, the mainland territory of which comprises the western and northernmost portion of the Scandinavian Peninsula. The remote Arctic island of Jan Mayen and t ...

. Following this operation, the destroyer continued to operate with Home Fleet. She screened the aircraft carrier during flight operations in November and after two convoy voyages to Iceland

Iceland ( is, Ísland; ) is a Nordic island country in the North Atlantic Ocean and in the Arctic Ocean. Iceland is the most sparsely populated country in Europe. Iceland's capital and largest city is Reykjavík, which (along with its s ...

, ''Hobson'' and Desdiv 20 returned to Boston and U.S. operational control 3 December 1943.

Hunter-killer anti-submarine duty

During the first two months of 1944, ''Hobson'' trained inChesapeake Bay

The Chesapeake Bay ( ) is the largest estuary in the United States. The Bay is located in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region and is primarily separated from the Atlantic Ocean by the Delmarva Peninsula (including the parts: the ...

and operated with carriers between the East Coast

East Coast may refer to:

Entertainment

* East Coast hip hop, a subgenre of hip hop

* East Coast (ASAP Ferg song), "East Coast" (ASAP Ferg song), 2017

* East Coast (Saves the Day song), "East Coast" (Saves the Day song), 2004

* East Coast FM, a ra ...

and Bermuda. She joined escort carrier , flagship of Anti-Submarine Task Group 21.11, and the group's four other destroyers or destroyer escorts at Norfolk for temporary duty, departing 26 February 1944. These Hunter-killer Groups (HUK's) played a major part in driving German U-boats from the sea lanes, and this cruise was no exception. After patrolling for over two weeks, the destroyers spotted an oil slick, made sonar contact, and commenced depth charge attacks on the afternoon of 13 March 1944. The was severely damaged and was forced to surface, after which gunfire from ''Hobson'', , a torpedo bomber from Composite Squadron Ninety-Five (VC 95) based on ''Bogue'', the Canadian frigate HMCS ''Prince Rupert'' and an RAF Flying Fortress

The Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress is a four-engined heavy bomber developed in the 1930s for the United States Army Air Corps (USAAC). Relatively fast and high-flying for a bomber of its era, the B-17 was used primarily in the European Theater ...

(No. 220 Squadron) sank her. After further anti-submarine sweeps as far east as the Azores

)

, motto =( en, "Rather die free than subjected in peace")

, anthem= ( en, "Anthem of the Azores")

, image_map=Locator_map_of_Azores_in_EU.svg

, map_alt=Location of the Azores within the European Union

, map_caption=Location of the Azores wi ...

, ''Hobson'' detached from the HUK on 25 March 1944, and returned to Boston 2 April 1944.

D-Day, Utah Beach

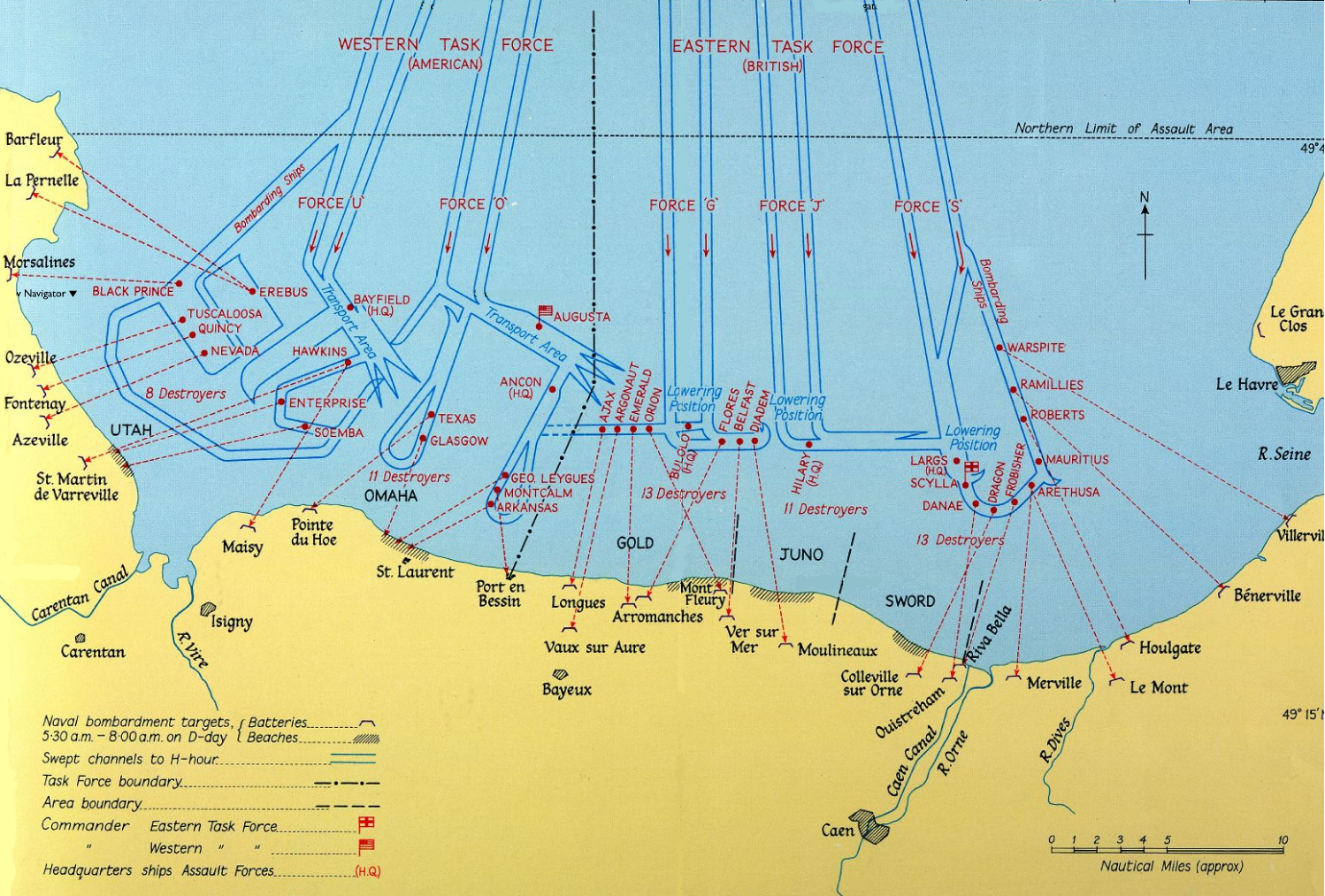

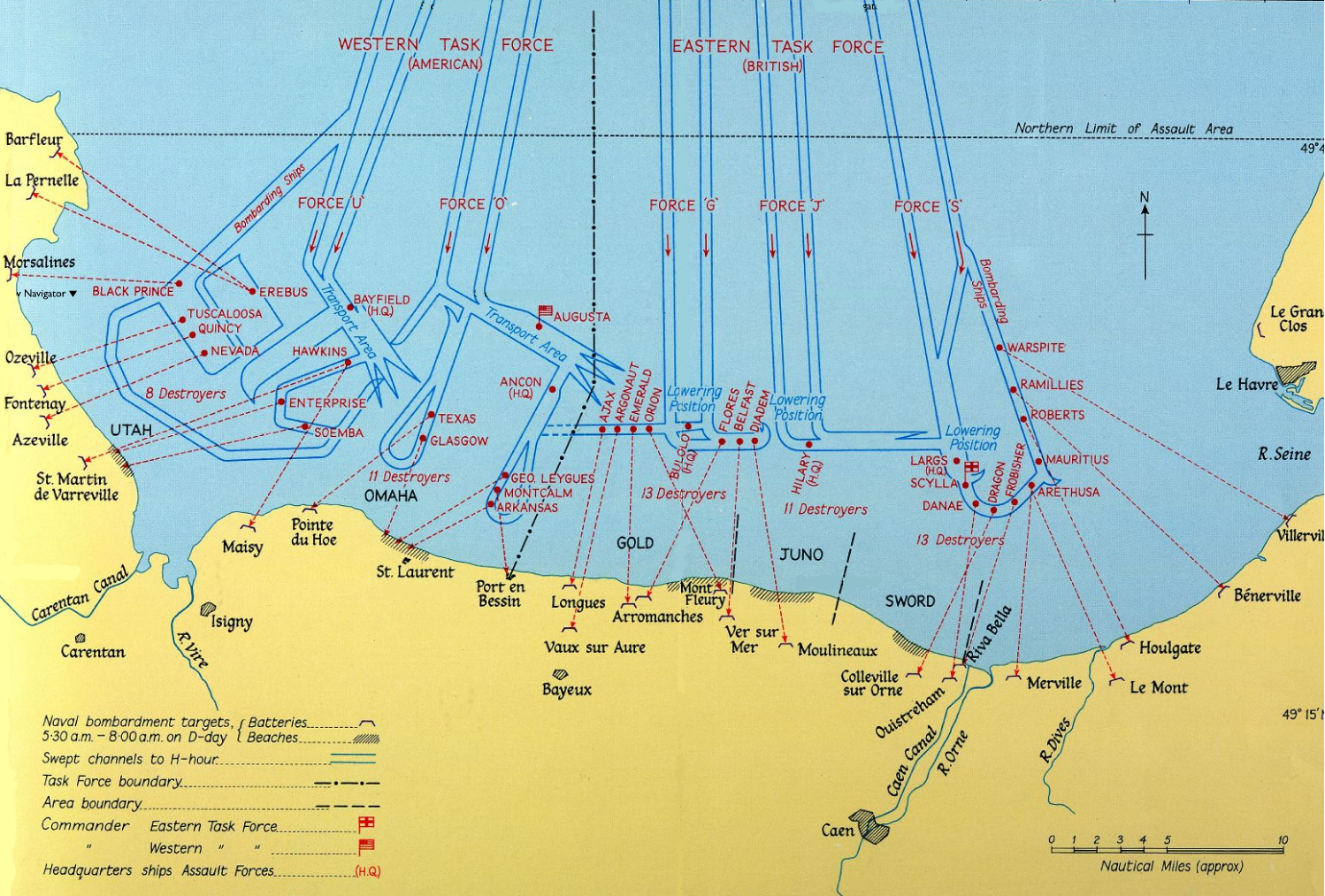

For some time the Allies had been building up tremendous strength in

For some time the Allies had been building up tremendous strength in England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

for the eventual invasion of France. ''Hobson'' and the other three destroyers of DesDiv 20, ''Corry'', ''Forrest'' and ''Fitch'', sailed from Norfolk on 21 April 1944 to join the vast armada of Operation Neptune

Operation or Operations may refer to:

Arts, entertainment and media

* ''Operation'' (game), a battery-operated board game that challenges dexterity

* Operation (music), a term used in musical set theory

* ''Operations'' (magazine), Multi-Man ...

that would transport and protect the soldiers and their mechanized equipment during Operation Overlord

Operation Overlord was the codename for the Battle of Normandy, the Allies of World War II, Allied operation that launched the successful invasion of German-occupied Western Front (World War II), Western Europe during World War II. The operat ...

. ''Hobson'' spent a month on patrol off Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland ( ga, Tuaisceart Éireann ; sco, label= Ulster-Scots, Norlin Airlann) is a part of the United Kingdom, situated in the north-east of the island of Ireland, that is variously described as a country, province or region. Nort ...

, arriving at Plymouth on 21 May for final invasion preparations. Assigned to Rear Admiral Don P. Moon

Don Pardee Moon (April 18, 1894 – August 5, 1944) was a rear admiral of the United States Navy, who fought in the invasion of Europe. He was born in Kokomo, Indiana, United States. He married and had four children.

Biography

Moon entered th ...

's Utah Beach Assault Group "U", flag on the , ''Hobson'' and her three sister-ships of DesDiv 20 were elements of Bombardment Group 125.8 that comprised the battleship

A battleship is a large armored warship with a main battery consisting of large caliber guns. It dominated naval warfare in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The term ''battleship'' came into use in the late 1880s to describe a type of ...

, the heavy cruisers , , British cruiser , monitor , ten American destroyers, four British destroyers and a Dutch gunboat.

The destroyers arrived off "Point Mike", the outermost area of Utah with the other ships of the bombardment group at 0140 on 6 June. All vessels entering into Utah had to remain in their assigned asymmetrical and exact mine-swept channels that had been drawn up and cleared to provide the maximum safety from the mine peril and to permit access to all the carefully designated positions of the bombardment ships. Minesweepers cleared the area where transport craft would assemble and discharge; and provided adequate channels for all the amphibious boats between "Transport Area" and the landing beaches. The order of ships was the British destroyers , , and the Dutch gunboat . The American destroyers , , "

''Hobson'' and ''Forrest'' followed as screen for ''Bayfield'' and three other Allied transports carrying General Raymond O. Barton

Major General Raymond Oscar "Tubby" Barton (August 22, 1889 – February 27, 1963) was a career officer in the United States Army and combat commander in World War I and World War II. As commander of the 4th Infantry Division during World War II ...

's 4th Infantry Division troops as far as the transport area. The destroyers then closed in on their action stations. Fire Support Unit 3, ''Hobson'', ''Corry'' and ''Fitch'', led the first waves of landing boats down the boat lane, breaking off in time to be in their stations at 0540.

The German shore batteries, having discovered the Allied invaders, began firing on the armada at 0530. At 0536, the group commander made the signal "Commence counter battery bombardment.", 14 minutes ahead of schedule. ''Hobson'' and the other ships began counter-firing as spent 5" and 8" shell casings littered their decks. Only the heavy ships had planes to spot for them. The destroyers were close enough to see their targets which consisted mostly of "strong points" just back of the beaches. ''Hobson'', at station 1, was assigned firing on targets 70 and 72. At 0629, ''Hobson'' observed shell splashes near and at 0633, ''Corry'' appeared to be hit amidships. As smoke from the intense shore firing drifted offshore and temporarily concealed ''Corry'', ''Hobson'' shifted her fire at 0638 to target 86 which appeared to have been firing on ''Corry''. This battery temporarily ceased firing as soon as taken under fire by ''Hobson''. At 0644, the destroyer shifted her fire back to targets 70 and 72 since the leading boat wave was close to shore and neutralization of German firing from those areas was vital. At 0656, the smoke was extremely heavy on the beach, making it difficult to see the targets, and ''Hobson'', per her prior firing orders, estimated that the first troops were going ashore and shifted fire to target 74, which was in an excellent position to deliver deadly enfilade and strafing fire on the Allied landing troops. At 0700, the smoke cover was clearing from ''Corry'' and the men on ''Hobson'' could see she was "in definite trouble with her back broken between the stacks" as targets 13A and 86 fired on the stricken destroyer. ''Corry'', the worst naval loss of the D-Day landings, was hit by the

The German shore batteries, having discovered the Allied invaders, began firing on the armada at 0530. At 0536, the group commander made the signal "Commence counter battery bombardment.", 14 minutes ahead of schedule. ''Hobson'' and the other ships began counter-firing as spent 5" and 8" shell casings littered their decks. Only the heavy ships had planes to spot for them. The destroyers were close enough to see their targets which consisted mostly of "strong points" just back of the beaches. ''Hobson'', at station 1, was assigned firing on targets 70 and 72. At 0629, ''Hobson'' observed shell splashes near and at 0633, ''Corry'' appeared to be hit amidships. As smoke from the intense shore firing drifted offshore and temporarily concealed ''Corry'', ''Hobson'' shifted her fire at 0638 to target 86 which appeared to have been firing on ''Corry''. This battery temporarily ceased firing as soon as taken under fire by ''Hobson''. At 0644, the destroyer shifted her fire back to targets 70 and 72 since the leading boat wave was close to shore and neutralization of German firing from those areas was vital. At 0656, the smoke was extremely heavy on the beach, making it difficult to see the targets, and ''Hobson'', per her prior firing orders, estimated that the first troops were going ashore and shifted fire to target 74, which was in an excellent position to deliver deadly enfilade and strafing fire on the Allied landing troops. At 0700, the smoke cover was clearing from ''Corry'' and the men on ''Hobson'' could see she was "in definite trouble with her back broken between the stacks" as targets 13A and 86 fired on the stricken destroyer. ''Corry'', the worst naval loss of the D-Day landings, was hit by the Crisbecq Battery

The Crisbecq Battery (sometimes called Marcouf Battery) was a German World War II artillery battery constructed by the Todt Organization near the French village of Saint-Marcouf, Manche, Saint-Marcouf in the department of Manche in the north-east ...

, whose three 210-millimeter (8.25-inch) guns had a range of .

Since target 74 was then inactive, ''Hobson'' began alternately taking targets 13A and 86 under fire while keeping watch on target 74. At 0721, it was clear that ''Corry'' was sinking and ''Hobson'' began to close range on her while continuing her firing on the two targets. At that time, the group commander ordered to stand by the ''Corry'' since ''Hobson''s mission of covering the landing beach flank was vital. By then the German shore batteries at 13A and 86 had ceased firing, and ''Hobson'' lowered her two boats to assist ''Fitch'' in picking up the ''Corry''s survivors. ''Hobson'' then resumed her station and continued firing on target 74 and a nearby roadblock and strong point. At 0854, according to schedule, relieved ''Hobson'' at her station, and ''Hobson'' was ordered to assume ''Corry''s fire support mission at station 3. ''Hobson'' continued firing on German shore positions while simultaneously rescuing survivors from the water until returning to Plymouth, England, later that afternoon. The destroyer was not long out of the fray, however, returning on 8 June 1944 to screen the assault area. She also jammed glider bomb radio frequencies on 9–11 June and provided channel convoy protection.

Bombardment of Cherbourg

After the Allies' successful establishment of a bridgehead at Normandy, the German strategy was to bottle them up there, deny the Allies access to the nearest major port at Cherbourg and break their supply line. By mid-June U.S. infantry had sealed off the Cotentin Peninsula, but their advance had stalled and the Germans began to demolish the port's facilities. With the Allies sorely in need of Cherbourg to continue advancing through France, they renewed their efforts to capture the city, and by 20 June three infantry divisions under General "Lightning Joe" Collins had advanced within a mile of German lines defending Cherbourg. Two days later, the general assault began and on 25 June, a large naval task force began a concentrated bombardment of the town to help neutralize the threat of German coastal artillery and to provide support to the assaulting infantry. Task Force 129 was divided into two divisions. Battle Group 1 under AdmiralMorton Deyo

Vice Admiral Morton Lyndholm Deyo (1 July 1887 – 10 November 1973) was an officer in the United States Navy, who was a naval gunfire support task force commander of World War II.

Born on 1 July 1887 in Poughkeepsie, New York, he graduated from ...

's command, was assigned to bombard Cherbourg, the inner harbor forts, and the area west towards the Atlantic. Group 1 consisted of , , , and five destroyers: (flag), , , , , and .

Rear Admiral Carleton F. Bryant's smaller Battle Group 2 was assigned "Target 2", the Battery Hamburg, which was located near Fermanville, inland from Cape Levi, east of Cherbourg. ''Nevada'' in Group 1 was to use its main battery to silence what was described as "the most powerful German strongpoint on the Cotentin Peninsula". Battle Group 2 would then complete the destruction, and pass westward to join Deyo's group. Bryant's Group 2 consisted of , , and five destroyers.Morison, Samuel E., op.cit., page 198-200 These were (flag), , , ''Hobson'' (pennant), and . During the bombardment. Group 2 was in place by 0950 and ''Hobson'' and the other destroyers fired at the large batteries, screened the battleship

A battleship is a large armored warship with a main battery consisting of large caliber guns. It dominated naval warfare in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The term ''battleship'' came into use in the late 1880s to describe a type of ...

s ''Texas'' and ''Arkansas''; and when the battleships were dangerously straddled, ''Hobson'' and ''Plunkett'' made covering smoke which allowed all to retire. At 1500, Deyo ordered cease fire and began withdrawing from the bombardment area. Group 2 headed back to Portsmouth, England at 1501.

After the action, Allied reports agreed that the most effective aspect of the bombardment was the fire that was provided by the small ships. Under the direction of army spotters, these ships were able to engage point targets up to 2,000 yards (1,800 m) inland, which proved invaluable in providing close support to the assaulting Allied infantry. In contrast, while the force's heavy guns disabled 22 of 24 assigned navy targets, they were unable to destroy any of them and, consequently, infantry assaults were required to ensure that the guns could not be reactivated. By 29 June, Allied troops occupied Cherbourg and its crucial port. Collins wrote to Deyo, stating that during the "naval bombardment of the coastal batteries and the covering strong points around Cherbourg ... results were excellent, and did much to engage the enemy's fire while our troops stormed into Cherbourg from the rear." After an inspection of the port defenses, an army liaison officer reported that the guns that had been targeted could not be reactivated, and those that could have been turned landward were still pointed out to sea when the city had fallen.Morison, Samuel E., op.cit., page 210-211

Invasion of Southern France and Mediterranean Convoy Duty

Following the surrender of Cherbourg, ''Hobson'' and most of Task Force 129 that had not sustained battle damage, were ordered toBelfast

Belfast ( , ; from ga, Béal Feirste , meaning 'mouth of the sand-bank ford') is the capital and largest city of Northern Ireland, standing on the banks of the River Lagan on the east coast. It is the 12th-largest city in the United Kingdo ...

, Northern Ireland to join the attack transports that had assembled there following service in the Normandy Invasion and to await the move to the Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the e ...

. ''Hobson'' and the other ships arrived at Belfast on 30 June and there, Task Group 120.6 under Admiral Deyo on ''Tuscaloosa'' was formed consisting of the transports and most of Task Force 129. They sailed on 4 July and arrived at Mers-el-Kébir, Algeria

)

, image_map = Algeria (centered orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Algiers

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, relig ...

, 11 July 1944, and for a month after, performed convoy duties to and from Taranto

Taranto (, also ; ; nap, label= Tarantino, Tarde; Latin: Tarentum; Old Italian: ''Tarento''; Ancient Greek: Τάρᾱς) is a coastal city in Apulia, Southern Italy. It is the capital of the Province of Taranto, serving as an important com ...

, Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical re ...

.The Emmons Saga, ''A History of the ''USS EMMONS (DD457-DMS22) (2005), p. 275-280 USS Emmons Assoc.

/ref> The landing areas for

Operation Dragoon

Operation Dragoon (initially Operation Anvil) was the code name for the landing operation of the Allied invasion of Provence (Southern France) on 15August 1944. Despite initially designed to be executed in conjunction with Operation Overlord, th ...

the invasion of Southern France and the last major amphibious operation of the European theater, were designated "Alpha", "Delta" and "Camel" from west to east, covering three sets of beaches along the Provence

Provence (, , , , ; oc, Provença or ''Prouvènço'' , ) is a geographical region and historical province of southeastern France, which extends from the left bank of the lower Rhône to the west to the Italian border to the east; it is bor ...

Coast between Hyeres and Cannes

Cannes ( , , ; oc, Canas) is a city located on the French Riviera. It is a communes of France, commune located in the Alpes-Maritimes departments of France, department, and host city of the annual Cannes Film Festival, Midem, and Cannes Lions I ...

. The Western Naval Task Force was formed under the command of Vice Admiral Hewitt to carry the U.S. 6th Army Group, also known as the Southern Group or Dragoon Force onto the shore. Joining Rear Admiral Bertram J. Rodgers

Bertram Joseph Rodgers (March 18, 1894 – November 30, 1983) was a highly decorated Vice Admiral in the United States Navy during World War II. He received his Navy Cross as a Captain of USS ''Salt Lake City'' in the battle of the Komando ...

' Delta Assault Force, Task Group 85.12 was the gunfire support group for the central invasion force under Rear Admiral Bryant on ''Texas''. It consisted of the American battleships ''Texas'' and ''Nevada''; light cruiser and French light cruisers ''Georges Leygues'', and ''Montcalm''; the surviving eight destroyers of DesRon 10 (Destroyer Unit 85.12.4), ''Ellyson'', ''Rodman'', ''Emmons'', ''Forrest'', ''Fitch'', ''Hambleton'', ''Macomb'', and ''Hobson''; French destroyers ''La Fantasque'', ''Le Terrible'', ''Le Malin'', and four gun support craft, which sailed from Taranto at 1400 on 11 August 1944. "H-hour" was set for 0800 on 15 August. Early on 15 August 1944, ''Hobson'' acted as spotter for ''Nevada'' and her preliminary bombardment from the Baie de Bougnon. As troops stormed ashore at Delta Beach ( Le Muy, Saint-Tropez

, INSEE = 83119

, postal code = 83990

, image coat of arms = Blason ville fr Saint-Tropez-A (Var).svg

, image flag=Flag of Saint-Tropez.svg

Saint-Tropez (; oc, Sant Tropetz, ; ) is a commune in the Var department and the region of Provence-Al ...

), ''Hobson'' provided direct fire support with her own batteries. By 0815, the bombardment had destroyed enemy defenses and Major General William W. Eagles' famed "Thunderbirds" of the 45th Infantry Division landed without opposition. ''Hobson'' remained in the assault area until the next evening, arriving at Palermo

Palermo ( , ; scn, Palermu , locally also or ) is a city in southern Italy, the capital (political), capital of both the autonomous area, autonomous region of Sicily and the Metropolitan City of Palermo, the city's surrounding metropolitan ...

on 17 August 1944 to take up Mediterranean convoy duty.

As the Allied offensive in Europe gained momentum, ''Hobson'' steamed as a convoy escort between Algeria, Italy, and France protecting vital supplies and troops. In the early morning darkness of 2 October 1944, ''Hobson'' was standing out from Marseilles, France, during a violent gale, when her spotters observed distress calls from well inside an unswept area of the German- mined harbor. It was soon established that a liberty ship, the ''S.S. Johns Hopkins'', moving to an anchorage after returning from Oran, Algeria, with 600 troops embarked, had struck a mine while navigating in the gale. Ordered to assist the stricken ''Hopkins'', ''Hobson'' skillfully and carefully navigated through the perilous, mined area in gale-force wind and sea, and made repeated attempts to land alongside the liberty ship to offload her troops, although each time ''Hobson'' was forced to back off as the ships pounded heavily in the extreme weather. Through Lt. Cdr. Loveland's skillful ship-handling and that of his deck crew, the damage to ''Hobson'' was superficial. ''Hobson'' remained close aboard the stricken cargo ship until daylight when safe water was finally reached, the ships having crossed thirteen and one-half miles of unswept water. ''Hobson'' remained on scene over the next twenty-four hours, and until ''S.S. Johns Hopkins'' was successfully returned to port by a Navy fleet tug

A tugboat or tug is a marine vessel that manoeuvres other vessels by pushing or pulling them, with direct contact or a tow line. These boats typically tug ships in circumstances where they cannot or should not move under their own power, suc ...

boat with no loss of life or injury to her personnel or troops.

Service as a destroyer- minesweeper

In October 1944, with the Atlantic and Mediterranean theaters secured, all eight surviving destroyers of DesRon 10 returned to various east coast navy yards where over a period of approximately six weeks, they had their No. 4 5-inch guns replaced with gear for sweeping acoustic mines. On 15 November they were reclassified asdestroyer-minesweeper

Destroyer minesweeper was a designation given by the United States Navy to a series of destroyers that were converted into high-speed ocean-going minesweepers for service during World War II. The hull classification symbol for this type of ship wa ...

s (DMS 19–26). ''Hobson'' sailed for the United States on 25 October and arrived at Charleston via Bermuda on 10 November 1944. There she entered the Naval Shipyard and was converted to destroyer-minesweeper and commissioned DMS-26 on 15 November 1944, Lt. Cmdr. Joseph I. Manning, commanding. Throughout the month of December, she underwent trials and shakedown training off Charleston and Norfolk. In January 1945, the eight newly converted destroyer-minesweepers made their way from their conversion shipyards to the Pacific as the core of the 12-ship Mine Squadron (MinRon) 20, with flag on the ''Ellyson''.The Emmons Saga, ''A History of the ''USS EMMONS (DD457-DMS22) (2005), p. 275-280 USS Emmons Assoc.

/ref> ''Hobson'' and several others in the squadron sailed on 4 January 1945 via the

Panama Canal

The Panama Canal ( es, Canal de Panamá, link=no) is an artificial waterway in Panama that connects the Atlantic Ocean with the Pacific Ocean and divides North and South America. The canal cuts across the Isthmus of Panama and is a conduit ...

, with stops at San Diego for training and inspection, and then stood out from San Francisco for Hawaii, arriving at Pearl Harbor

Pearl Harbor is an American lagoon harbor on the island of Oahu, Hawaii, west of Honolulu. It was often visited by the Naval fleet of the United States, before it was acquired from the Hawaiian Kingdom by the U.S. with the signing of the Re ...

on 11 February 1945. ''Hobson'' was part of Mine Division (MinDiv) 58, along with ''Forrest'' (pennant), ''Fitch'' and ''Macomb''. At Hawaii, she underwent further mine warfare training before sailing on 24 February 1945 with eight of the twelve ships of MinRon 20 as Task Unit 18.2.3 for Ulithi

Ulithi ( yap, Wulthiy, , or ) is an atoll in the Caroline Islands of the western Pacific Ocean, about east of Yap.

Overview

Ulithi consists of 40 islets totaling , surrounding a lagoon about long and up to wide—at one of the largest i ...

via Eniwetok

Enewetak Atoll (; also spelled Eniwetok Atoll or sometimes Eniewetok; mh, Ānewetak, , or , ; known to the Japanese as Brown Atoll or Brown Island; ja, ブラウン環礁) is a large coral atoll of 40 islands in the Pacific Ocean and with it ...

and a role in the history of the last and greatest of the Pacific amphibious operations, Operation Iceberg

Operation or Operations may refer to:

Arts, entertainment and media

* ''Operation'' (game), a battery-operated board game that challenges dexterity

* Operation (music), a term used in musical set theory

* ''Operations'' (magazine), Multi-Man ...

, the assault on Okinawa.

Okinawa, Kamikaze attacks

On 9 March 1945, ''Hobson'' arrived at Ulithi, the main staging area for the Okinawa Invasion 1,180 mi. away from the objective, where she and eight other members of her squadron engaged in exercises and calibration of their sweeping equipment until the remaining three sweepers arrived on the 12th. On the last day at sea ''Fitch'' wrecked her propeller on a reef and had to return to Pearl Harbor. The aircraft carriers departed for Okinawa on 14 March, and the eleven remaining sweeps of MinRon 20 left on the 19th. Given the nature of their task, the minesweepers had to be the first surface vessels at the target area and unlike the carriers, they headed directly to Okinawa, making the voyage in four days. While the four-day journey was uneventful, the two threats the minesweepers faced were Japanese air attacks and the deteriorating weather. ''Hobson'' arrived atOkinawa

is a prefecture of Japan. Okinawa Prefecture is the southernmost and westernmost prefecture of Japan, has a population of 1,457,162 (as of 2 February 2020) and a geographic area of 2,281 km2 (880 sq mi).

Naha is the capital and largest city ...

well in advance of the assault troops to sweep the offshore areas, where she was often attacked by Japanese planes. In the early hours of L-Day, she and ''Emmons'' were on radar picket duty with ''Hobson'' as fire support ship. As the amphibious assault began on 1 April 1945, ''Hobson'' also took up patrol duties and provided night illumination during the first critical days of the campaign. As desperate enemy suicide attacks were repulsed with heavy losses, ''Hobson'' was called upon on 13 April 1945 to take up a radar picket station where had been sunk in a heavy kamikaze

, officially , were a part of the Japanese Special Attack Units of military aviators who flew suicide attacks for the Empire of Japan against Allied naval vessels in the closing stages of the Pacific campaign of World War II, intending to d ...

attack the previous night.

''Hobson''s executive officer

An executive officer is a person who is principally responsible for leading all or part of an organization, although the exact nature of the role varies depending on the organization. In many militaries and police forces, an executive officer, o ...

, Lt. Robert M. Vogel gave this account: On 16 April 1945 at 0500 and 75 miles northwest of Okinawa, fifteen enemy planes spotted ''Hobson'', and two accompanying gunboats

A gunboat is a naval watercraft designed for the express purpose of carrying one or more guns to shore bombardment, bombard coastal targets, as opposed to those military craft designed for naval warfare, or for troopship, ferrying troops or au ...

and made passes at the ships; however, the attackers were driven off by anti-aircraft fire

Anti-aircraft warfare, counter-air or air defence forces is the battlespace response to aerial warfare, defined by NATO as "all measures designed to nullify or reduce the effectiveness of hostile air action".AAP-6 It includes surface based, ...

. At 0853, one of the planes made a suicide run on ''Pringle'' but was shot down by gunners on both ''Hobson'' and ''Pringle''. Another dived on ''Pringle'' at 0920, slamming into the destroyer's bridge, and plowing through the superstructure deck, abaft the base of number one stack. A single 1,000-pound bomb, or two 500-pounders, penetrated the main and superstructure decks and exploded with a violent eruption, buckling the keel and splitting the vessel in two at the forward fire room. ''Pringle'' sank in six minutes.

Two minutes later, a single-engine aircraft began a suicide run on ''Hobson'' from the starboard side. Five-inch shells from the destroyer disintegrated the plane just short of the ship, but its 250-pound bomb penetrated the deck house. The explosion of the delayed action bomb started fires in the gunnery workshop, machine shop and electrical shop and blasted a hole in the deck over the forward engine room, wrecking steam and power lines. Four of her crew were killed and six wounded.

Two more suicide planes attacked ''Hobson'' but her gunners shot them into the sea. The two gunboats shot down another. The remaining Japanese planes continued to make passes for an hour before they withdrew. Meanwhile, the ''Hobson''s crew extinguished the fires in fifteen minutes, rigged emergency power lines in four minutes and the ship continued to maneuver. Thirty-five minutes after the attack ended, ''Hobson'' had picked up 136 of the ''Pringle''s 258 survivors, clinging to rafts and wreckage. The two gunboats rescued the others. During the attack, ''Hobson''s gunners shot down four Japanese suicide planes in 67 minutes. That same morning, about 40 minutes before ''Pringle'' was sunk, the destroyer and several other ships on radar picket duty, had also been hit by kamikazes about fifty miles away.

After the attack, ''Hobson'' anchored at Kerama Retto

The are a subtropical island group southwest of Okinawa Island in Japan.

Geography

Four islands are inhabited: Tokashiki Island, Zamami Island, Aka Island, and Geruma Island. The islands are administered as Tokashiki Village and Zamami Vill ...

, returning to Ulithi

Ulithi ( yap, Wulthiy, , or ) is an atoll in the Caroline Islands of the western Pacific Ocean, about east of Yap.

Overview

Ulithi consists of 40 islets totaling , surrounding a lagoon about long and up to wide—at one of the largest i ...

on 29 April 1945 and Pearl Harbor on 16 May 1945. ''Hobson'' then sailed via San Diego and the Panama Canal Zone

The Panama Canal Zone ( es, Zona del Canal de Panamá), also simply known as the Canal Zone, was an unincorporated territory of the United States, located in the Isthmus of Panama, that existed from 1903 to 1979. It was located within the terr ...

to Norfolk Naval Shipyard

The Norfolk Naval Shipyard, often called the Norfolk Navy Yard and abbreviated as NNSY, is a U.S. Navy facility in Portsmouth, Virginia, for building, remodeling and repairing the Navy's ships. It is the oldest and largest industrial facility tha ...

, where she arrived on 15 June 1945 for repairs.

Post war and sinking

The unconditional surrender of Imperial Japan came with ''Hobson'' still undergoing repairs. With repairs completed and after shakedown training, she spent February 1946 on mine-sweeping operations out of Yorktown, Virginia. The remainder of the year was spent in training and readiness exercises in theCaribbean

The Caribbean (, ) ( es, El Caribe; french: la Caraïbe; ht, Karayib; nl, De Caraïben) is a region of the Americas that consists of the Caribbean Sea, its islands (some surrounded by the Caribbean Sea and some bordering both the Caribbean Se ...

and off Norfolk. Until 1950, the ship continued to operate off the East Coast and in Caribbean waters on amphibious and mine warfare operations. In late 1948, she visited Argentia

Argentia ( ) is a Canadian commercial seaport and industrial park located in the Town of Placentia, Newfoundland and Labrador. It is situated on the southwest coast of the Avalon Peninsula and defined by a triangular shaped headland which r ...

and Halifax, Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia ( ; ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is one of the three Maritime provinces and one of the four Atlantic provinces. Nova Scotia is Latin for "New Scotland".

Most of the population are native Eng ...

on mine-sweeping exercises with Canadian

Canadians (french: Canadiens) are people identified with the country of Canada. This connection may be residential, legal, historical or cultural. For most Canadians, many (or all) of these connections exist and are collectively the source of ...

ships. With the outbreak of the Korean War

, date = {{Ubl, 25 June 1950 – 27 July 1953 (''de facto'')({{Age in years, months, weeks and days, month1=6, day1=25, year1=1950, month2=7, day2=27, year2=1953), 25 June 1950 – present (''de jure'')({{Age in years, months, weeks a ...

in June 1950, ''Hobson''s schedule of training intensified. She took part in amphibious exercises off North Carolina

North Carolina () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States. The state is the 28th largest and 9th-most populous of the United States. It is bordered by Virginia to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, Georgia and So ...

and Puerto Rico

Puerto Rico (; abbreviated PR; tnq, Boriken, ''Borinquen''), officially the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico ( es, link=yes, Estado Libre Asociado de Puerto Rico, lit=Free Associated State of Puerto Rico), is a Caribbean island and Unincorporated ...

during 1950–51, and participated in carrier operations as a plane guard and screening ship.

During one such operation on the night of 26 April 1952 at 2220, ''Hobson'' was steaming in formation with the aircraft carrier

An aircraft carrier is a warship that serves as a seagoing airbase, equipped with a full-length flight deck and facilities for carrying, arming, deploying, and recovering aircraft. Typically, it is the capital ship of a fleet, as it allows a ...

and destroyers and about southeast of St. John's, Newfoundland

St. John's is the capital and largest city of the Canadian province of Newfoundland and Labrador, located on the eastern tip of the Avalon Peninsula on the island of Newfoundland.

The city spans and is the easternmost city in North America ...

at during night flight operations en route to Gibraltar

)

, anthem = " God Save the King"

, song = " Gibraltar Anthem"

, image_map = Gibraltar location in Europe.svg

, map_alt = Location of Gibraltar in Europe

, map_caption = United Kingdom shown in pale green

, mapsize =

, image_map2 = Gib ...

. ''Hobson'' was moving at 24 knots and following the carrier 3,000 yards off her starboard

Port and starboard are nautical terms for watercraft and aircraft, referring respectively to the left and right sides of the vessel, when aboard and facing the bow (front).

Vessels with bilateral symmetry have left and right halves which are ...

quarter with ''Rodman'' following ''Wasp'' off her port quarter. ''Hobson''s commanding officer, Lt. Comdr. William J. Tierney, had been in command of the ship for 5 weeks. He anticipated that ''Wasp'', preparing to recover her aircraft at 2300, would change course to 250–260 degrees to bring the carrier into the wind, necessary for the aircraft landings. The destroyer's executive officer, Lt. William A. Hoefer, was on the bridge with the conn and control of the ship when Tierney outlined a course to maneuver ''Hobson'' ahead of ''Wasp'' and then come up on the massive carrier's port quarter as the destroyer's new station. ''Rodman'' would move to the starboard quarter as her new station. Hoefer, who had been on ''Hobson'' for 16 months, was immediately concerned when he saw Tierney's plan and turned the conn over to Lt. Donald Cummings, so that he could voice his opposition and belief that Tierney's maneuver would put the two ships on a collision course. Since ''Wasp'' had to turn to starboard to recover aircraft, the trailing destroyer had two options, slow down and let ''Wasp'' turn, the conventional method, or cross in front of the carrier. A heated argument ensued that Hoefer lost and he strode off the bridge to the outside wing to cool off.

Meanwhile, ''Wasp''s commanding officer, Capt. Burnham C. McCaffree, was on his bridge, where Lt. Robert Herbst had the conn and ordered right standard rudder and flank speed to bring the carrier into the wind. McCaffree observed the red aircraft warning lights of the two destroyers and believed that they were also beginning the evolution. Tierney, now in control of ''Hobson'' ordered right standard rudder and a course of 130 degrees. The wind shifted and McCaffree ordered a necessary course change from 260 to 250 degrees to head into the wind. At that time ''Wasp''s surface radar failed, while on ''Hobson'', the port pelorus was fogged, thus preventing an accurate bearing on ''Wasp''. McCaffree notified the destroyers of his course change, but it is unclear whether anyone on ''Hobson''s bridge heard the communication. Tierney, without disclosing his intention, was going to put the ''Hobson'' into a Williamson turn that would bring the ship back to the point she had been. Tierney suddenly ordered full left rudder and within 30 seconds ordered full right rudder. Hoefer rushed back onto ''Hobson''s bridge when he realized what Tierney was doing and yelled "Prepare for collision!, Prepare for collision!" At that moment, Tierney ordered left full rudder, intending to race ahead of ''Wasp'' which was bearing down on the destroyer. Aboard ''Wasp'', Lt. Herbst told Capt. McCaffree, "We're in trouble" as McCaffree ordered "all back emergency."

At first it looked as though ''Hobson'' might escape the massive carrier as her bow and number-one stack moved past the carrier's course, but then there was a horrendous, grinding crash as ''Wasp'' struck ''Hobson'' amidships. The force of the collision rolled the destroyer-minesweeper over onto her port side, breaking her in two. The aft section of ''Hobson'' trailed alongside of the carrier while the forward half was temporarily lodged in the ''Wasp''s bow. The aft part of the ship sank first but 40 of the survivors came from that section as men were literally shot out of a scuttle hatch they had managed to open, propelled by the force of water and expelling air. Aboard the carrier, life rafts were being dropped over and lines lowered. One set of double rafts fell on top of a cluster of five men who were never seen again. One lucky man, a chief petty officer

A chief petty officer (CPO) is a senior non-commissioned officer in many navies and coast guards.

Canada

"Chief petty officer" refers to two ranks in the Royal Canadian Navy. A chief petty officer 2nd class (CPO2) (''premier maître de deuxi� ...

in the bow, managed to grab a pipe protruding from ''Wasp'' just as ''Hobson''s bow began her descent under the waves and leaped onto ''Wasp'' without getting wet. Survival for the rest of ''Hobson''s crew in the thick, glutinous fuel oil was incredible, yet it happened for some. ''Rodman'' and ''Wasp'' pulled aboard 61 oil-coated survivors, but the destroyer and 176 of her crew including Tierney, who dove from the bridge into the sea moments before the carrier plowed into ''Hobson'', were lost in less than five minutes. Most of the deceased crew were recovered by ''Ross'' and placed on the blood soaked main deck. This horrific incident brought about the tragic end of the destroyer-minesweeper's valiant service. The sinking of ''Hobson'' was the worst non-combat accident for the U.S. Navy since the disappearance of the collier with 306 crew and passengers en route from Barbados

Barbados is an island country in the Lesser Antilles of the West Indies, in the Caribbean region of the Americas, and the most easterly of the Caribbean Islands. It occupies an area of and has a population of about 287,000 (2019 estimate). ...

to Baltimore

Baltimore ( , locally: or ) is the List of municipalities in Maryland, most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland, fourth most populous city in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic, and List of United States cities by popula ...

, Maryland, in March 1918, during World War I.

Aftermath and findings

A court of inquiry performed an investigation into the sinking of ''Hobson'' in an effort to determine the cause of the tragedy. The opinion of the court of inquiry was "that the sole cause of the collision was the unexplained left turn made by the ''Hobson'' about 2224. In making this left turn the Commanding Officer committed a grave error in judgement." Since the commanding officer did not survive the collision, the reason for this error could not be determined. No one else was considered to be at fault and the crew of ''Wasp'' was absolved of any responsibility for the collision. The commanding officer of ''Hobson'' had six months of prior command experience on aHigh-speed transport

High-speed transports were converted destroyers and destroyer escorts used in US Navy amphibious operations in World War II and afterward. They received the US Hull classification symbol APD; "AP" for transport and "D" for destroyer. In 1969, the ...

(APD), but had been in command of ''Hobson'' for only five weeks. Seven days of that were underway and only days were with the task group. The cost of repairs to ''Wasp'' was said to be $1 million ($ today).

As a direct result of the sinking of ''Hobson'', upon recommendation of the court of inquiry, the Allied Navy Signal Book was changed. A special signal was to be put into use for carriers during aircraft operations. The court of inquiry also stated in its findings that, in the future, proposed schedules for aircraft launching and recovery should be provided to the vessels performing plane guard duties.

The court of inquiry also noted that ''Wasp'', ''Rodman'', and ''Hobson'' were all running without normal marine navigation lights, just red aircraft warning lights on top of their masts.

USS Hobson Memorial, Charleston, SC

In 1954, the ''USS Hobson Memorial Society'' erected an obelisk memorial of Salisbury Pink granite, quarried fromSalisbury, North Carolina

Salisbury is a city in the Piedmont region of North Carolina, United States; it has been the county seat of Rowan County since 1753 when its territory extended to the Mississippi River. Located northeast of Charlotte and within its metropolita ...

, at the city where ''Hobson'' had been built 14 years earlier, Charleston, South Carolina

Charleston is the largest city in the U.S. state of South Carolina, the county seat of Charleston County, and the principal city in the Charleston–North Charleston metropolitan area. The city lies just south of the geographical midpoint o ...

. The memorial is dedicated to the 176 men of the ''Hobson'' who perished in the collision with ''Wasp''. Surrounding the obelisk are stones from each of the 38 states where the men came from. Their names are inscribed and can also be seen in the 1954 dedication program for the memorial.

Honors and awards

''Hobson'' received sixbattle star

A service star is a miniature bronze or silver five-pointed star inch (4.8 mm) in diameter that is authorized to be worn by members of the eight uniformed services of the United States on medals and ribbons to denote an additional award or ser ...

s for World War II service, five in the European theater and one in the Asiatic Pacific theater, and shared in the Presidential Unit Citation awarded to the ships in the ''Bogue'' antisubmarine task group in the Atlantic, for the period 26 February to 25 March 1944.

''Hobson''s engagements were:

* Allied landing at Casablance, French Morocco – 8 Nov. 1942;

* Carrier strike at Bodo, Norway – Oct. 1943;

* Sank German submarine ''U-575'' – 13 March 1944;

* Allied Landing at Normandy, France – 6 June 1944;

* Allied Landing- Southern France – 15 August 1944; and

* American Landing at Okinawa, Japan – April 1945.

''Hobson''s captain, Lt. Cdr. Loveland, was awarded the Legion of Merit

The Legion of Merit (LOM) is a military award of the United States Armed Forces that is given for exceptionally meritorious conduct in the performance of outstanding services and achievements. The decoration is issued to members of the eight ...

with Combat "V" for his exceptionally meritorious conduct for depth-charging and subsequently sinking the ''U-575'' on 13 March 1944 after it surfaced. For his gallantry in action at the Normandy D-Day amphibious assault on Utah Beach and later at the bombardment of German defenses at Cherbourg, Loveland was awarded the Silver Star

The Silver Star Medal (SSM) is the United States Armed Forces' third-highest military decoration for valor in combat. The Silver Star Medal is awarded primarily to members of the United States Armed Forces for gallantry in action against an e ...

. He was awarded the Navy and Marine Corps Medal

The Navy and Marine Corps Medal is the highest non-combat decoration awarded for heroism by the United States Department of the Navy to members of the United States Navy and United States Marine Corps. The medal was established by an act of Congr ...

for heroism and meritorious performance of duty in the face of great danger during the ''Hobson''s attempted rescue and successful towing operation of the mined SS ''Johns Hopkins'' off Marseilles, France, on 2 October 1944. For his extraordinary heroism during the attack at Okinawa, ''Hobson''s commanding officer, Lt. Cdr. Manning, was awarded the Navy Cross. Also for the Okinawa action, ''Hobson''s executive officer, Lt. Vogel, was awarded the Bronze Star

The Bronze Star Medal (BSM) is a United States Armed Forces decoration awarded to members of the United States Armed Forces for either heroic achievement, heroic service, meritorious achievement, or meritorious service in a combat zone.

Wh ...

and her engineer officer, Lt. (j.g.) Martin J. Cavanaugh, Jr., and Chief Machinist's Mate, Howard B. Farris, were awarded the Silver Star

The Silver Star Medal (SSM) is the United States Armed Forces' third-highest military decoration for valor in combat. The Silver Star Medal is awarded primarily to members of the United States Armed Forces for gallantry in action against an e ...

.

See also

* , sunk in a collision with in 1969.Notes

References

*External links

* *Hobson-Wasp Collision Collection, 1952–1953 MS 245

held by Special Collection & Archives, Nimitz Library at the United States Naval Academy * {{DEFAULTSORT:Hobson Hobson (DD-464) Hobson (DD-464) Ships built in Charleston, South Carolina World War II shipwrecks in the Atlantic Ocean Ships sunk in collisions 1941 ships Hobson (DD-464) Maritime incidents in 1952