USS Denver (C-14) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

USS ''Denver'' (C-14/PG-28/CL-16) was the lead ship of her class of protected cruisers in the

During the First Nicaraguan Campaign, ''Denver'' embarked multiple landing parties, the largest, a 120-man landing force under the command of

During the First Nicaraguan Campaign, ''Denver'' embarked multiple landing parties, the largest, a 120-man landing force under the command of

United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

. She was the first Navy ship named for the city of Denver

Denver () is a consolidated city and county, the capital, and most populous city of the U.S. state of Colorado. Its population was 715,522 at the 2020 census, a 19.22% increase since 2010. It is the 19th-most populous city in the Unit ...

, the capital of Colorado

Colorado (, other variants) is a state in the Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It encompasses most of the Southern Rocky Mountains, as well as the northeastern portion of the Colorado Plateau and the western edge of t ...

.

''Denver'' was launched on 21 June 1902 by Neafie and Levy Ship and Engine Building Company in Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Sinc ...

, sponsored by Miss R. W. Wright, daughter of Robert R. Wright, the mayor of Denver; and commissioned on 17 May 1904, with Commander

Commander (commonly abbreviated as Cmdr.) is a common naval officer rank. Commander is also used as a rank or title in other formal organizations, including several police forces. In several countries this naval rank is termed frigate captain.

...

Joseph Ballard Murdock in command. She was reclassified PG-28 in 1920 and CL-16 on 8 August 1921.

Service history

Caribbean patrol

Between 15 July and 26 July 1904, ''Denver'' visitedGalveston, Texas

Galveston ( ) is a coastal resort city and port off the Southeast Texas coast on Galveston Island and Pelican Island in the U.S. state of Texas. The community of , with a population of 47,743 in 2010, is the county seat of surrounding Galvesto ...

, where she was presented a gift of silver service from the people of Denver. She cruised in the Caribbean

The Caribbean (, ) ( es, El Caribe; french: la Caraïbe; ht, Karayib; nl, De Caraïben) is a region of the Americas that consists of the Caribbean Sea, its islands (some surrounded by the Caribbean Sea and some bordering both the Caribbean Se ...

, investigating disturbances in Haiti

Haiti (; ht, Ayiti ; French: ), officially the Republic of Haiti (); ) and formerly known as Hayti, is a country located on the island of Hispaniola in the Greater Antilles archipelago of the Caribbean Sea, east of Cuba and Jamaica, and ...

, then returned to Philadelphia on 1 October. During the next two and a half years, she cruised the Atlantic

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the " Old World" of Africa, Europe an ...

Coast and in the Caribbean, joining in target practice

In the military and in shooting, target practice are exercises in which weapons are shot at a target. The purpose of such exercises is to improve the aim or the weapons handling expertise of the person firing the weapon.

Targets being shot at ...

and other exercises, and protecting American interests from political disturbance in the West Indies

The West Indies is a subregion of North America, surrounded by the North Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea that includes 13 independent island countries and 18 dependencies and other territories in three major archipelagos: the Greater A ...

. On 13 September 1906, a landing force consisting of six officers and 124 bluejackets and marines, under the command of Lt. Comdr. M. L. Miller was landed from ''Denver'' at Havana, Cuba. This landing force returned on board on 14 September 1906. Crewmembers serving on ''Denver'' between 12 September and 2 October 1906 qualified for award of the Cuban Pacification Medal

The Cuban Pacification Medal (Navy) is a military award of the United States Navy which was created by orders of the United States Navy Department on 13 August 1909. The medal was awarded to officers and enlisted men who served ashore in Cuba betw ...

.

1906 ceremonies

Non-campaign highlights of this period of her service included her participation atAnnapolis

Annapolis ( ) is the capital city of the U.S. state of Maryland and the county seat of, and only incorporated city in, Anne Arundel County. Situated on the Chesapeake Bay at the mouth of the Severn River, south of Baltimore and about east o ...

between 19 April and 27 April 1906 in the interment ceremonies for John Paul Jones at the United States Naval Academy

The United States Naval Academy (US Naval Academy, USNA, or Navy) is a federal service academy in Annapolis, Maryland. It was established on 10 October 1845 during the tenure of George Bancroft as Secretary of the Navy. The Naval Academy ...

; a midshipman

A midshipman is an officer of the lowest rank, in the Royal Navy, United States Navy, and many Commonwealth navies. Commonwealth countries which use the rank include Canada (Naval Cadet), Australia, Bangladesh, Namibia, New Zealand, South Afr ...

training cruise to Madeira

)

, anthem = ( en, "Anthem of the Autonomous Region of Madeira")

, song_type = Regional anthem

, image_map=EU-Portugal_with_Madeira_circled.svg

, map_alt=Location of Madeira

, map_caption=Location of Madeira

, subdivision_type=Sovereign st ...

and the Azores

)

, motto =( en, "Rather die free than subjected in peace")

, anthem= ( en, "Anthem of the Azores")

, image_map=Locator_map_of_Azores_in_EU.svg

, map_alt=Location of the Azores within the European Union

, map_caption=Location of the Azores wi ...

in the summer of 1906; and the Fleet Review off Oyster Bay, Long Island

Long Island is a densely populated island in the southeastern region of the U.S. state of New York (state), New York, part of the New York metropolitan area. With over 8 million people, Long Island is the most populous island in the United Sta ...

, by President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

*President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ful ...

Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

in September 1906.

Asiatic fleet

Thecruiser

A cruiser is a type of warship. Modern cruisers are generally the largest ships in a fleet after aircraft carriers and amphibious assault ships, and can usually perform several roles.

The term "cruiser", which has been in use for several hu ...

sailed from Tompkinsville, New York

Tompkinsville is a neighborhood in northeastern Staten Island in New York City. Named for Daniel D. Tompkins, sixth Vice President of the United States (1817-1825), the neighborhood sits on the island's eastern shore, along the waterfront facing U ...

, on 18 May 1907 for duty with the Asiatic Fleet

The United States Asiatic Fleet was a fleet of the United States Navy during much of the first half of the 20th century. Before World War II, the fleet patrolled the Philippine Islands. Much of the fleet was destroyed by the Japanese by Februar ...

in the Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

, sailing through the Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the e ...

and Suez Canal

The Suez Canal ( arz, قَنَاةُ ٱلسُّوَيْسِ, ') is an artificial sea-level waterway in Egypt, connecting the Mediterranean Sea to the Red Sea through the Isthmus of Suez and dividing Africa and Asia. The long canal is a popular ...

to Cavite

Cavite, officially the Province of Cavite ( tl, Lalawigan ng Kabite; Chavacano: ''Provincia de Cavite''), is a province in the Philippines located in the Calabarzon region in Luzon. Located on the southern shores of Manila Bay and southwest ...

, where she arrived on 1 August. ''Denver'' visited ports in China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

, Manchuria

Manchuria is an exonym (derived from the endo demonym " Manchu") for a historical and geographic region in Northeast Asia encompassing the entirety of present-day Northeast China (Inner Manchuria) and parts of the Russian Far East (Outer Manc ...

, and Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north ...

, and joined in the regular exercise schedule of the fleet until 1 January 1910, when she cleared Cavite for Mare Island Naval Shipyard

The Mare Island Naval Shipyard (MINSY) was the first United States Navy base established on the Pacific Ocean. It is located northeast of San Francisco in Vallejo, California. The Napa River goes through the Mare Island Strait and separates th ...

. Arriving there on 15 February, she was placed out of commission on 12 March; she was then placed in reserve commission on 4 January 1912, and placed in full commission on 15 July 1912 for service in the Pacific.

Pacific fleet

On 19 July 1912,Assistant Secretary of the Navy

Assistant Secretary of the Navy (ASN) is the title given to certain civilian senior officials in the United States Department of the Navy.

From 1861 to 1954, the Assistant Secretary of the Navy was the second-highest civilian office in the Depar ...

Beekman Winthrop

Beekman Winthrop (September 18, 1874 – November 10, 1940) was an American lawyer, government official and banker. He served as the governor of Puerto Rico from 1904 to 1907, as assistant secretary of the Treasury in 1907–1909, and assistant se ...

announced that on 30 July, ''Denver'' would depart Mare Island bound for the west coast of Mexico

Mexico (Spanish: México), officially the United Mexican States, is a country in the southern portion of North America. It is bordered to the north by the United States; to the south and west by the Pacific Ocean; to the southeast by Guatema ...

and its principal ports including Mazatlan and Acapulco

Acapulco de Juárez (), commonly called Acapulco ( , also , nah, Acapolco), is a city and major seaport in the state of Guerrero on the Pacific Coast of Mexico, south of Mexico City. Acapulco is located on a deep, semicircular bay and has bee ...

before returning to Mare Island in what he termed "a friendly call." However, because of worsening political turmoil in Nicaragua

Nicaragua (; ), officially the Republic of Nicaragua (), is the largest country in Central America, bordered by Honduras to the north, the Caribbean to the east, Costa Rica to the south, and the Pacific Ocean to the west. Managua is the cou ...

that threatened American lives and property there, ''Denver'' was instead ordered to proceed from Santa Cruz, California to Mare Island to replenish stores for a trip to San Diego, where she was due 10 August, and after that, on to Central America. At San Diego, ''Denver's'' departure was delayed until 13 August due to engine repairs.

Nicaragua 1912

''Denver's'' arrival at Nicaragua was further delayed when she stopped on 17 August, to render assistance and attempted to tow off and later, refloat a merchant ship, S.S. ''Pleiades'' that had run aground off the coast of Mexico that day. ''Denver'' and her crew remained until 21 August; however, their efforts to dislodge the ship were unsuccessful. With the crew and passengers of ''Pleiades'' out of danger, ''Denver'' continued south toNicaragua

Nicaragua (; ), officially the Republic of Nicaragua (), is the largest country in Central America, bordered by Honduras to the north, the Caribbean to the east, Costa Rica to the south, and the Pacific Ocean to the west. Managua is the cou ...

.

For the next five years, ''Denver'' cruised the West Coast West Coast or west coast may refer to:

Geography Australia

* Western Australia

*Regions of South Australia#Weather forecasting, West Coast of South Australia

* West Coast, Tasmania

**West Coast Range, mountain range in the region

Canada

* Britis ...

from San Francisco

San Francisco (; Spanish language, Spanish for "Francis of Assisi, Saint Francis"), officially the City and County of San Francisco, is the commercial, financial, and cultural center of Northern California. The city proper is the List of Ca ...

to the Panama Canal Zone

The Panama Canal Zone ( es, Zona del Canal de Panamá), also simply known as the Canal Zone, was an unincorporated territory of the United States, located in the Isthmus of Panama, that existed from 1903 to 1979. It was located within the terr ...

, patrolling the coasts of Nicaragua

Nicaragua (; ), officially the Republic of Nicaragua (), is the largest country in Central America, bordered by Honduras to the north, the Caribbean to the east, Costa Rica to the south, and the Pacific Ocean to the west. Managua is the cou ...

and Mexico

Mexico (Spanish: México), officially the United Mexican States, is a country in the southern portion of North America. It is bordered to the north by the United States; to the south and west by the Pacific Ocean; to the southeast by Guatema ...

to investigate and prevent threats to the lives and property of Americans during political disturbances, carrying stores and mail

The mail or post is a system for physically transporting postcards, letter (message), letters, and parcel (package), parcels. A postal service can be private or public, though many governments place restrictions on private systems. Since the mid ...

, evacuating refugee

A refugee, conventionally speaking, is a displaced person who has crossed national borders and who cannot or is unwilling to return home due to well-founded fear of persecution.

s, and continuing the schedule of exercises which kept her ready for action. Crew members serving on ''Denver'' between 29 July and 14 November 1912 qualified for award of the First Nicaraguan Campaign Medal.

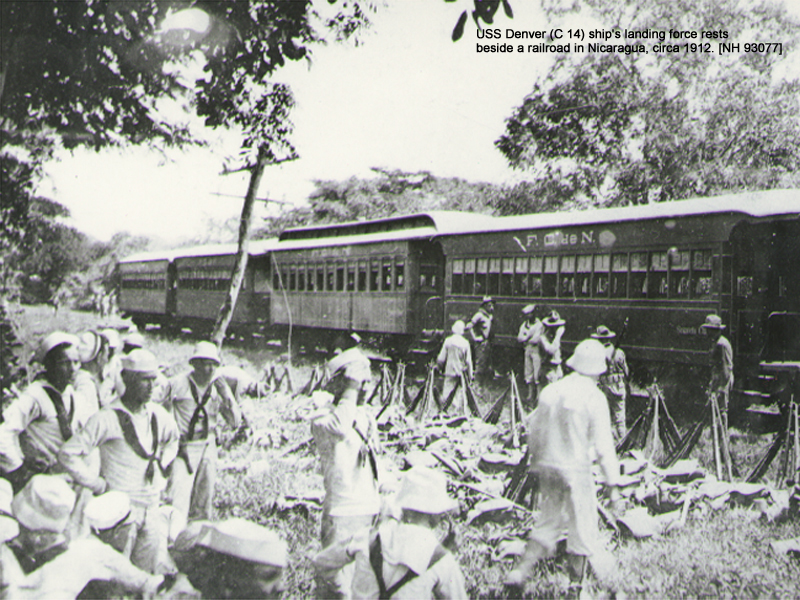

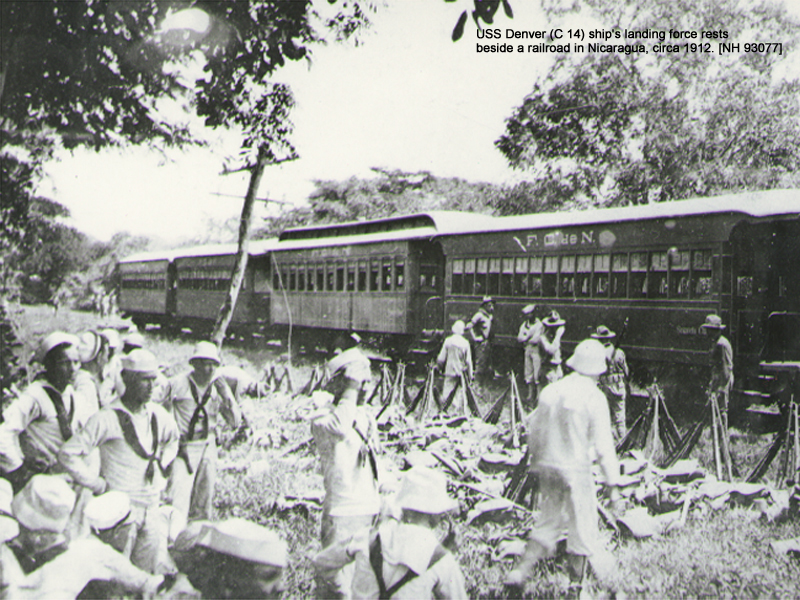

During the First Nicaraguan Campaign, ''Denver'' embarked multiple landing parties, the largest, a 120-man landing force under the command of

During the First Nicaraguan Campaign, ''Denver'' embarked multiple landing parties, the largest, a 120-man landing force under the command of Lieutenant

A lieutenant ( , ; abbreviated Lt., Lt, LT, Lieut and similar) is a commissioned officer rank in the armed forces of many nations.

The meaning of lieutenant differs in different militaries (see comparative military ranks), but it is often sub ...

Allen B. Reed

Captain Allen Bevins Reed (April 3, 1884 – February 28, 1965) was a U.S. Naval officer whose career began aboard vessels in the Asiatic and Pacific Fleets. Early in his career he was Captain Takeshita Isamu's escort during a ceremonial visi ...

landed at Corinto, Nicaragua, for duty ashore between 27 August and 26 October 1912 to secure the railway line running from Corinto to Managua and then south to Granada on the north shore of Lake Nicaragua. One officer and 24 men were landed from ''Denver'' at San Juan del Sur on the southern end of the Nicaraguan isthmus from 30 August to 6 September 1912, and from 11 to 27 September 1912 to protect the cable station, custom house

A custom house or customs house was traditionally a building housing the offices for a jurisdictional government whose officials oversaw the functions associated with importing and exporting goods into and out of a country, such as collecting c ...

and American interests. ''Denver'' remained at San Juan del Sur to relay wireless

Wireless communication (or just wireless, when the context allows) is the transfer of information between two or more points without the use of an electrical conductor, optical fiber or other continuous guided medium for the transfer. The most ...

messages from the other navy ships to and from Washington until departing on 30 September, for patrol duty.

''Denver'' departed Corinto on 26 October 1912 to return to Mare Island with stops at Mexican ports on her way back to California. She was at Manzanillo, Mexico

Manzanillo () is a city and seat of Manzanillo Municipality, in the Mexican state of Colima. The city, located on the Pacific Ocean, contains Mexico's busiest port, responsible for handling Pacific cargo for the Mexico City area. It is the large ...

on 1 November and San Diego on 9 December where she remained through 20 December, conducting gunnery practice before returning to Mare Island. In early 1913, ''Denver'' made an uneventful -month cruise in Mexican waters, during which time she made stops at Acapulco

Acapulco de Juárez (), commonly called Acapulco ( , also , nah, Acapolco), is a city and major seaport in the state of Guerrero on the Pacific Coast of Mexico, south of Mexico City. Acapulco is located on a deep, semicircular bay and has bee ...

, Acajutla, San Salvador

San Salvador (; ) is the capital and the largest city of El Salvador and its eponymous department. It is the country's political, cultural, educational and financial center. The Metropolitan Area of San Salvador, which comprises the capital i ...

and Corinto, before arriving at San Diego

San Diego ( , ; ) is a city on the Pacific Ocean coast of Southern California located immediately adjacent to the Mexico–United States border. With a 2020 population of 1,386,932, it is the List of United States cities by population, eigh ...

on 3 May 1913.

From 1913 to early 1917, Denver continued to regularly operate off the Mexican Coast during the ongoing insurrection in Mexico. Crew members serving on ''Denver'' on any of the following dates: 7–8 July 1914; 13–24 August 1914; 4 April–29 June 1916; 15 July–14 September 1916 or 16 December 1916 – 7 February 1917 qualified for award of the Mexican Service Medal.

World War I

Between 6 December 1916 and 30 March 1917 ''Denver'' surveyed theGulf of Fonseca

The Gulf of Fonseca ( es, Golfo de Fonseca; ), a part of the Pacific Ocean, is a gulf in Central America, bordering El Salvador, Honduras, and Nicaragua.

History

Fonseca Bay was discovered for Europeans in 1522 by Gil González de Ávila, ...

on the coast of Nicaragua, and on 10 April arrived at Key West, Florida

Key West ( es, Cayo Hueso) is an island in the Straits of Florida, within the U.S. state of Florida. Together with all or parts of the separate islands of Sigsbee Park, Dredgers Key, Fleming Key, Sunset Key, and the northern part of Stock Isla ...

, for patrol

A patrol is commonly a group of personnel, such as Law enforcement officer, law enforcement officers, military personnel, or Security guard, security personnel, that are assigned to monitor or secure a specific geographic area.

Etymology

Fro ...

duty off the Bahamas

The Bahamas (), officially the Commonwealth of The Bahamas, is an island country within the Lucayan Archipelago of the West Indies in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic. It takes up 97% of the Lucayan Archipelago's land area and is home to ...

and between Key West and Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribbea ...

.

''Denver'' reported at New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

on 22 July 1917 for duty escorting merchant convoys out of New York and Norfolk, Virginia

Norfolk ( ) is an independent city in the Commonwealth of Virginia in the United States. Incorporated in 1705, it had a population of 238,005 at the 2020 census, making it the third-most populous city in Virginia after neighboring Virginia Be ...

, to a mid-ocean meeting point where destroyer

In naval terminology, a destroyer is a fast, manoeuvrable, long-endurance warship intended to escort

larger vessels in a fleet, convoy or battle group and defend them against powerful short range attackers. They were originally developed in ...

s took over the task of convoying men and troops to ports in England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

and France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

. Before the close of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, ''Denver'' made eight such voyages. Crewmembers serving on ''Denver'' between 22 August 1917 and 3 November 1918 qualified for the World War I Victory Medal with ''Escort clasp''.

Post-war

Following theArmistice

An armistice is a formal agreement of warring parties to stop fighting. It is not necessarily the end of a war, as it may constitute only a cessation of hostilities while an attempt is made to negotiate a lasting peace. It is derived from the La ...

, ''Denver'' was detached on 5 December 1918 to patrol the east coast of South America

South America is a continent entirely in the Western Hemisphere and mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a relatively small portion in the Northern Hemisphere at the northern tip of the continent. It can also be described as the southe ...

, returning to New York on 4 June 1919. Between 7 July 1919 and 27 September 1921, she voyaged from New York to San Francisco, serving in the Panama Canal Zone and on the coasts of Central America

Central America ( es, América Central or ) is a subregion of the Americas. Its boundaries are defined as bordering the United States to the north, Colombia to the south, the Caribbean Sea to the east, and the Pacific Ocean to the west. ...

both outward and homeward bound.

In the summer of 1922, ''Denver'' carried Charles D. B. King

Charles Dunbar Burgess King (12 March 1875 – 4 September 1961) was a Liberian politician who served as the 17th president of Liberia from 1920 to 1930. He was of Americo-Liberian and Sierra Leone Creole descent. He was a member of the True Whig ...

, the President of Liberia

The president of the Republic of Liberia is the head of state and government of Liberia. The president serves as the leader of the executive branch and as commander-in-chief of the Armed Forces of Liberia.

Prior to the independence of Liberia ...

, home to Monrovia

Monrovia () is the capital city of the West African country of Liberia. Founded in 1822, it is located on Cape Mesurado on the Atlantic coast and as of the 2008 census had 1,010,970 residents, home to 29% of Liberia’s total population. As the ...

from a visit in the United States, returning to Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

by way of the Canal Zone. On 9 October she returned to the Canal Zone for eight years of service based at Cristóbal

Cristóbal or Cristobal, the Spanish version of Christopher, is a masculine given name and a surname which may refer to:

Given name

*Cristóbal Balenciaga (1895–1972), Spanish fashion designer

*Cristóbal Cobo (born 1976), Chilean academic

*Cri ...

. She patrolled both coasts of Central America

Central America ( es, América Central or ) is a subregion of the Americas. Its boundaries are defined as bordering the United States to the north, Colombia to the south, the Caribbean Sea to the east, and the Pacific Ocean to the west. ...

, protecting American interests, transporting various official parties, and paying courtesy calls, returning periodically to Boston for overhaul. Between 20 November and 18 December 1922, she carried relief supplies to earthquake

An earthquake (also known as a quake, tremor or temblor) is the shaking of the surface of the Earth resulting from a sudden release of energy in the Earth's lithosphere that creates seismic waves. Earthquakes can range in intensity, from ...

and tsunami

A tsunami ( ; from ja, 津波, lit=harbour wave, ) is a series of waves in a water body caused by the displacement of a large volume of water, generally in an ocean or a large lake. Earthquakes, volcanic eruptions and other underwater explo ...

victims in Chile

Chile, officially the Republic of Chile, is a country in the western part of South America. It is the southernmost country in the world, and the closest to Antarctica, occupying a long and narrow strip of land between the Andes to the east a ...

.

Honduras 1924-1925

On 28 February 1924, a landing force, consisting of themarine

Marine is an adjective meaning of or pertaining to the sea or ocean.

Marine or marines may refer to:

Ocean

* Maritime (disambiguation)

* Marine art

* Marine biology

* Marine debris

* Marine habitats

* Marine life

* Marine pollution

Military

* ...

detachment and special details under the command of First Lieutenant

First lieutenant is a commissioned officer military rank in many armed forces; in some forces, it is an appointment.

The rank of lieutenant has different meanings in different military formations, but in most forces it is sub-divided into a s ...

T.H. Cartwright, U.S.M.C., was landed from ''Denver'' at La Ceiba, Honduras

Honduras, officially the Republic of Honduras, is a country in Central America. The republic of Honduras is bordered to the west by Guatemala, to the southwest by El Salvador, to the southeast by Nicaragua, to the south by the Pacific Oce ...

, to protect the American Consulate. A battle between the political factions of Honduras was in progress at the time. 29 February 1924, a landing force of 35 men, under the command of Lt. (jg) Rony Snyder, U.S. Navy, was landed from ''Denver'', at La Ceiba, Honduras. The entire landing force was under the command of Major

Major (commandant in certain jurisdictions) is a military rank of commissioned officer status, with corresponding ranks existing in many military forces throughout the world. When used unhyphenated and in conjunction with no other indicators ...

E.W. Sturdevant, U.S.M.C. The landing force from ''Denver'' was returned on board ship on 3 March 1924, at Tela, Honduras, by the . On 4 March 1924, a landing force, consisting of eight officers and 159 men, under the command of Major E.W. Sturdevant, U.S.M.C., was landed from ''Denver'', at Puerto Cortez

Puerto, a Spanish word meaning ''seaport'', may refer to:

Places

* El Puerto de Santa María, Andalusia, Spain

*Puerto, a seaport town in Cagayan de Oro City, Philippines

* Puerto Colombia, Colombia

* Puerto Cumarebo, Venezuela

* Puerto Galera, O ...

, Honduras, where a neutral zone was established. This landing force was returned aboard ship on 6 March 1924. On 7 March 1924, a landing force of five officers and 65 men, under the command of Major Sturdevant, U.S.M.C., was landed from ''Denver'', at Puerto Cortez, Honduras. The landing force returned on board ''Denver'' on 9 March 1924. On 9 March 1924, a landing force consisting of three officers and 21 men under command of Major Sturdevant, U.S.M.C., was landed from ''Denver'', at La Ceiba, Honduras. This detachment returned aboard ship on 13 March 1924. Crewmen serving between 28 February and 13 March 1924 qualified for award of the Navy Expeditionary Medal. Some 165 US peacekeeping troops commanded by Lt. Theodore Cartwright from ''Denver'' were deployed to maintain order in La Ceiba on 19–21 April 1925. Between November 1925 and June 1926, ''Denver'' served the Special Commission on Boundaries, Tacna-Arica Arbitration group, carrying dignitaries from Chile to the United States or the Canal Zone on two voyages.

Nicaragua 1926

On 10 October 1926, a landing force, consisting of six officers and 103 men, under the command ofCommander

Commander (commonly abbreviated as Cmdr.) is a common naval officer rank. Commander is also used as a rank or title in other formal organizations, including several police forces. In several countries this naval rank is termed frigate captain.

...

S.M. La Bounty, was landed from ''Denver'' at Corinto, to establish a neutral zone in order to protect the American and foreign lives and property. This force returned aboard ship on 27 October 1926. On 30 November 1926, a landing force, consisting of eight officers, fifty bluejackets and 58 marines, under the command of Commander La Bounty, was landed from ''Denver'' at Bluefields. On 27 December 1926, an additional force of 17 marines was landed at Bluefields. The landing force ashore at Bluefields returned aboard ship on 15 and 16 June 1927. On 23 December 1926, a landing force consisting of two officers and 95 men under the command of Lt. (J.G.) L. McKee, was landed from ''Denver'' at Puerto Cabezas, to reenforce the landing force of the . This force returned aboard ship on the same day. Crewmembers serving on her between various dates from September 1926 through October 1930 qualified for award of the Second Nicaraguan Campaign Medal

The Second Nicaraguan Campaign Medal is a campaign medal of the United States Navy which was authorized by an act of the United States Congress on 8 November 1929. The Second Nicaraguan Campaign Medal was awarded for service during operations in ...

.

''Denver''s last ceremonial function was her participation in the ceremonies held at Havana

Havana (; Spanish: ''La Habana'' ) is the capital and largest city of Cuba. The heart of the La Habana Province, Havana is the country's main port and commercial center.

from 14 to 19 February 1929 to commemorate the sinking of the . She returned to Philadelphia on 25 December 1930, and there was decommissioned on 14 February 1931 and sold on 13 September 1933.

Campaigns

References

Bibliography

*External links

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Denver CL-16 Protected cruisers of the United States Navy Denver (CL-16) Denver (CL-16) Denver (CL-16) Ships built by Neafie and Levy 1902 ships