UDA C Company on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The UDA West Belfast Brigade is the section of the

The origins of the UDA lay in west

The origins of the UDA lay in west

When Harding Smith left Northern Ireland in 1975

When Harding Smith left Northern Ireland in 1975

The Stevens Inquiries led to a period of chaos within the West Belfast Brigade, with a rapid succession of brigadiers and a number of leading members spending time in prison. Lyttle's arrest in early 1990 saw him relinquish the role of Brigadier, whilst the allegations that he was an informer saw him disowned by the rest of the Brigade with four others following him before the year was out. Stability initially looked set when Tommy Irvine was chosen as Brigadier and he set in place a new decentralised structure in which the commanders of A, B and C companies (at the time Matt Kincaid, Jim Spence and William "Winkie" Dodds respectively) would be given a freer hand in their activities. However Irvine was arrested as part of the inquiries in August 1990 and was very briefly replaced by Ken Barrett. Barrett was quickly ousted by Lyttle's choice, his brother-in-law

The Stevens Inquiries led to a period of chaos within the West Belfast Brigade, with a rapid succession of brigadiers and a number of leading members spending time in prison. Lyttle's arrest in early 1990 saw him relinquish the role of Brigadier, whilst the allegations that he was an informer saw him disowned by the rest of the Brigade with four others following him before the year was out. Stability initially looked set when Tommy Irvine was chosen as Brigadier and he set in place a new decentralised structure in which the commanders of A, B and C companies (at the time Matt Kincaid, Jim Spence and William "Winkie" Dodds respectively) would be given a freer hand in their activities. However Irvine was arrested as part of the inquiries in August 1990 and was very briefly replaced by Ken Barrett. Barrett was quickly ousted by Lyttle's choice, his brother-in-law

Spence was arrested on charges of extortion in March 1993 and gave up the role of Brigadier with Johnny Adair succeeding him. As Brigadier, Adair continued on the same bloody path that he had followed as military commander. One victim was Noel Cardwell, a mentally sub-normal glass collector at a C Company bar, the Diamond Jubilee, who was seen as a figure of fun by Adair and his cohorts. In December 1993 Cardwell was taken to the

Spence was arrested on charges of extortion in March 1993 and gave up the role of Brigadier with Johnny Adair succeeding him. As Brigadier, Adair continued on the same bloody path that he had followed as military commander. One victim was Noel Cardwell, a mentally sub-normal glass collector at a C Company bar, the Diamond Jubilee, who was seen as a figure of fun by Adair and his cohorts. In December 1993 Cardwell was taken to the

On 19 August 2000 the West Belfast Brigade hosted a "Loyalist Day of Culture" organised by Adair on the Lower Shankill with fellow brigadiers John Gregg, Billy McFarland,

On 19 August 2000 the West Belfast Brigade hosted a "Loyalist Day of Culture" organised by Adair on the Lower Shankill with fellow brigadiers John Gregg, Billy McFarland,  The militancy of the West Belfast Brigade, and in particular Adair, who had become a cult hero among loyalists, meant that the brigade enjoyed the loyalty of some UDA members outside its nominal geographic area. Within the North Belfast Brigade an influx of new young members found more to admire in Adair than in their own brigadier Jimbo Simpson, and affiliated to the West Belfast brigade despite not living in the area. Further afield a group of Shankill men had relocated to areas of North Down such as Bangor and

The militancy of the West Belfast Brigade, and in particular Adair, who had become a cult hero among loyalists, meant that the brigade enjoyed the loyalty of some UDA members outside its nominal geographic area. Within the North Belfast Brigade an influx of new young members found more to admire in Adair than in their own brigadier Jimbo Simpson, and affiliated to the West Belfast brigade despite not living in the area. Further afield a group of Shankill men had relocated to areas of North Down such as Bangor and

Ulster loyalist

Ulster loyalism is a strand of Ulster unionism associated with working class Ulster Protestants in Northern Ireland. Like other unionists, loyalists support the continued existence of Northern Ireland within the United Kingdom, and oppose a uni ...

paramilitary group, the Ulster Defence Association

The Ulster Defence Association (UDA) is an Ulster loyalism, Ulster loyalist paramilitary group in Northern Ireland. It was formed in September 1971 as an umbrella group for various loyalist groups and Timeline of Ulster Defence Association act ...

(UDA), based in the western quarter of Belfast

Belfast ( , ; from ga, Béal Feirste , meaning 'mouth of the sand-bank ford') is the capital and largest city of Northern Ireland, standing on the banks of the River Lagan on the east coast. It is the 12th-largest city in the United Kingdo ...

, in the Greater Shankill

The Shankill Road () is one of the main roads leading through West Belfast, in Northern Ireland. It runs through the working-class, predominantly loyalist, area known as the Shankill.

The road stretches westwards for about from central Belfast ...

area. Initially a battalion, the West Belfast Brigade emerged from the local "defence associations" active in the Shankill at the beginning of the Troubles

The Troubles ( ga, Na Trioblóidí) were an ethno-nationalist conflict in Northern Ireland that lasted about 30 years from the late 1960s to 1998. Also known internationally as the Northern Ireland conflict, it is sometimes described as an "i ...

and became the first section to be officially designated as a separate entity within the wider UDA structure. During the 1970s and 1980s the West Belfast Brigade was involved in a series of killings as well as establishing a significant presence as an outlet for racketeering

Racketeering is a type of organized crime in which the perpetrators set up a coercive, fraudulent, extortionary, or otherwise illegal coordinated scheme or operation (a "racket") to repeatedly or consistently collect a profit.

Originally and of ...

.

The Brigade reached the apex of its notoriety during the 1990s when Johnny Adair

John Adair (born 27 October 1963), better known as Johnny Adair or Mad Dog Adair, is an Ulster loyalist and the former leader of the "C Company", 2nd Battalion Shankill Road, West Belfast Brigade of the Ulster Freedom Fighters (UFF). This was a ...

emerged as its leading figure. Under Adair's direction the West Belfast Brigade in general and its sub-unit "C Company" in particular became associated with a killing spree in the neighbouring Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

nationalist

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a group of people), Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: The ...

districts of west Belfast. With Adair and his supporters suspicious of the developing Northern Ireland peace process

The Northern Ireland peace process includes the events leading up to the 1994 Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) ceasefire, the end of most of the violence of the Troubles, the Good Friday Agreement of 1998, and subsequent political developm ...

and the Combined Loyalist Military Command

The Combined Loyalist Military Command is an umbrella body for loyalist paramilitary groups in Northern Ireland set up in the early 1990s, recalling the earlier Ulster Army Council and Ulster Loyalist Central Co-ordinating Committee.

Bringing t ...

ceasefire of 1994, the West Belfast Brigade increasingly came to operate as a rogue group within the UDA, feuding with rival loyalists in the Ulster Volunteer Force

The Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) is an Ulster loyalist paramilitary group. Formed in 1965, it first emerged in 1966. Its first leader was Gusty Spence, a former British Army soldier from Northern Ireland. The group undertook an armed campaig ...

before splitting from the UDA altogether in late 2002. Ultimately Adair was forced out and the brigade was brought back into the mainstream UDA. It continues to organise, albeit with less significance than in its heyday. Matt Kincaid is the incumbent West Belfast Brigade leader and under his leadership the brigade has again become estranged from the wider UDA.

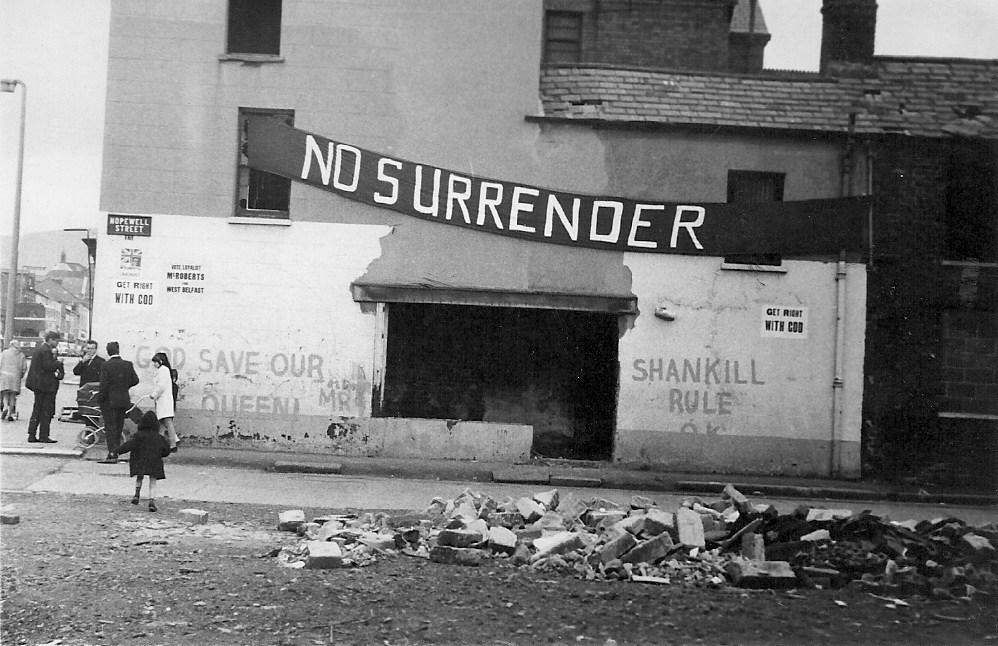

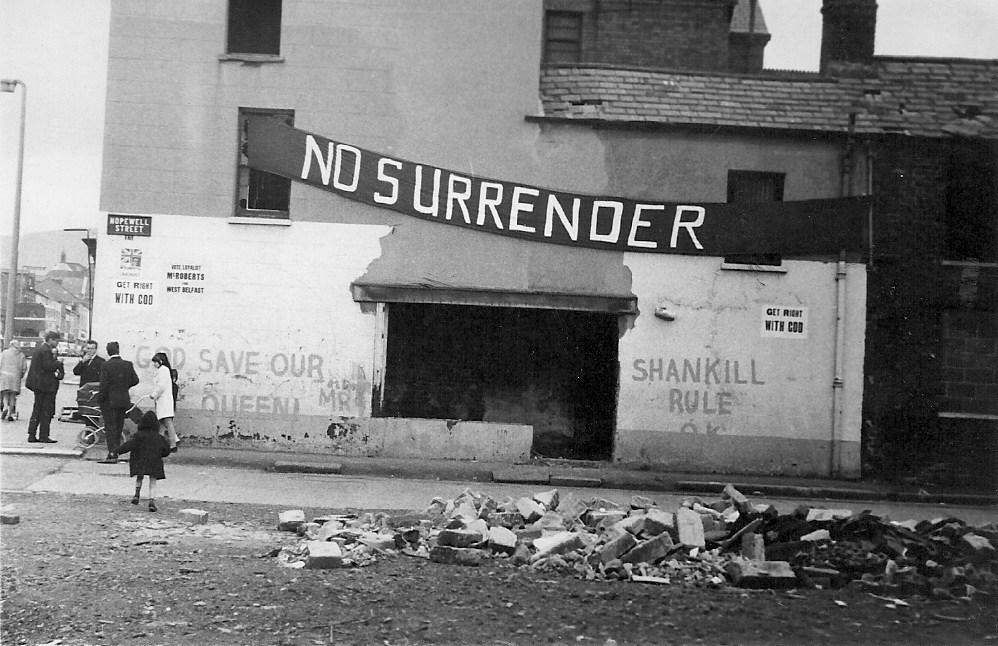

Origins

The origins of the UDA lay in west

The origins of the UDA lay in west Belfast

Belfast ( , ; from ga, Béal Feirste , meaning 'mouth of the sand-bank ford') is the capital and largest city of Northern Ireland, standing on the banks of the River Lagan on the east coast. It is the 12th-largest city in the United Kingdo ...

with the formation of vigilante groups such as the Shankill Defence Association

The Shankill Defence Association was a loyalist vigilante group formed in May 1969 for the defence of the loyalist Shankill Road area of Belfast, Northern Ireland during the communal disturbances that year.

The Shankill Defence Association was f ...

and the Woodvale Defence Association

The Woodvale Defence Association (WDA) was an Ulster loyalist vigilante group in the Woodvale district of Belfast, an area immediately to the north of the Shankill Road.

The organisation grew from a few smaller vigilante groups. It initially m ...

. The latter, formed by Charles Harding Smith

Charles Harding Smith (24 January 1931 – 1997) was a loyalist leader in Northern Ireland and the first effective leader of the Ulster Defence Association (UDA). An important figure in the Belfast-based "defence associations" that formed the ba ...

, became the largest of a number of similar groups and was instrumental in the establishment of the UDA in September 1971, having begun military training of its members two months earlier. In 1972, when Jim Anderson was serving as acting chairman of the UDA, a West Belfast battalion was formed as a separate part of the UDA, such was the volume of membership within the area. The battalion was divided into three separate companies: A Company, which was based on the Highfield estate with some members in Glencairn, B Company which covered the Woodvale area, and C Company for the Shankill Road

The Shankill Road () is one of the main roads leading through West Belfast, in Northern Ireland. It runs through the working-class, predominantly loyalist, area known as the Shankill.

The road stretches westwards for about from central Belfast a ...

itself. Battalions covering the other three areas of Belfast

Belfast ( , ; from ga, Béal Feirste , meaning 'mouth of the sand-bank ford') is the capital and largest city of Northern Ireland, standing on the banks of the River Lagan on the east coast. It is the 12th-largest city in the United Kingdo ...

as well as South East Antrim and North Antrim and Londonderry were formed soon afterwards and before long these were re-designated as brigades after the UDA experienced a rush of members.

Charles Harding Smith

The Battalion fell under the initial control ofDavy Fogel

David "Davy" Fogel, also known as "Big Dave" (born 1945), was a former loyalist and a leading member of the loyalist vigilante Woodvale Defence Association (WDA) which later merged with other groups becoming the Ulster Defence Association (UDA ...

, under whose leadership the group undertook a programme of erecting barricades between the Shankill and the neighbouring republican

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

Falls and Springfield Roads. However, the local strongman was Harding Smith, who had been held in prison on charges of gun-running in London

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a majo ...

. When he returned in early 1973 Harding Smith ran Fogel out of the area and became commander of the Battalion himself, whilst also becoming joint chairman of the UDA as a whole with Anderson.Taylor, p. 114

Harding Smith soon became embroiled in a feud

A feud , referred to in more extreme cases as a blood feud, vendetta, faida, clan war, gang war, or private war, is a long-running argument or fight, often between social groups of people, especially families or clans. Feuds begin because one part ...

with East Belfast leader Tommy Herron

Tommy Herron (1938 – 14 September 1973) was a Northern Irish loyalist and a leading member of the Ulster Defence Association (UDA) until his death in a fatal shooting. Herron controlled the UDA in East Belfast, one of its two earliest strongh ...

, whilst also facing a growing rival in his own area in the shape of Andy Tyrie

Andrew Tyrie (born 5 February 1940) is a Northern Irish loyalist paramilitary leader who served as commander of the Ulster Defence Association (UDA) during much of its early history. He took the place of Tommy Herron in 1973 when the latter was ...

, the commander of A Company. Tyrie was chosen as the overall Chairman of the UDA in 1973, with Anderson off the scene. Tyrie had initially been seen as a compromise candidate between the two real powerhouses of Harding Smith and Herron but before long he began to assert his independence. Herron was killed in late 1973 and soon after Tyrie and Harding Smith became openly hostile after Tyrie sanctioned a trip by UDA activists to Libya

Libya (; ar, ليبيا, Lībiyā), officially the State of Libya ( ar, دولة ليبيا, Dawlat Lībiyā), is a country in the Maghreb region in North Africa. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to the north, Egypt to Egypt–Libya bo ...

. Harding Smith publicly condemned the move, arguing that Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi

Muammar Muhammad Abu Minyar al-Gaddafi, . Due to the lack of standardization of transcribing written and regionally pronounced Arabic, Gaddafi's name has been romanized in various ways. A 1986 column by ''The Straight Dope'' lists 32 spellin ...

was a friend of the Provisional IRA

The Irish Republican Army (IRA; ), also known as the Provisional Irish Republican Army, and informally as the Provos, was an Irish republicanism, Irish republican paramilitary organisation that sought to end British rule in Northern Ireland, fa ...

, and in January 1975 he announced the secession of the West Belfast Brigade from the UDA. However, after a power struggle Harding Smith was driven out of Northern Ireland following two failed attempts on his life, according to Peter Taylor Peter Taylor may refer to:

Arts

* Peter Taylor (writer) (1917–1994), American author, winner of the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction

* Peter Taylor (film editor) (1922–1997), English film editor, winner of an Academy Award for Film Editing

Politic ...

by one of Tyrie's men. The West Belfast Brigade immediately returned to the mainstream UDA fold.

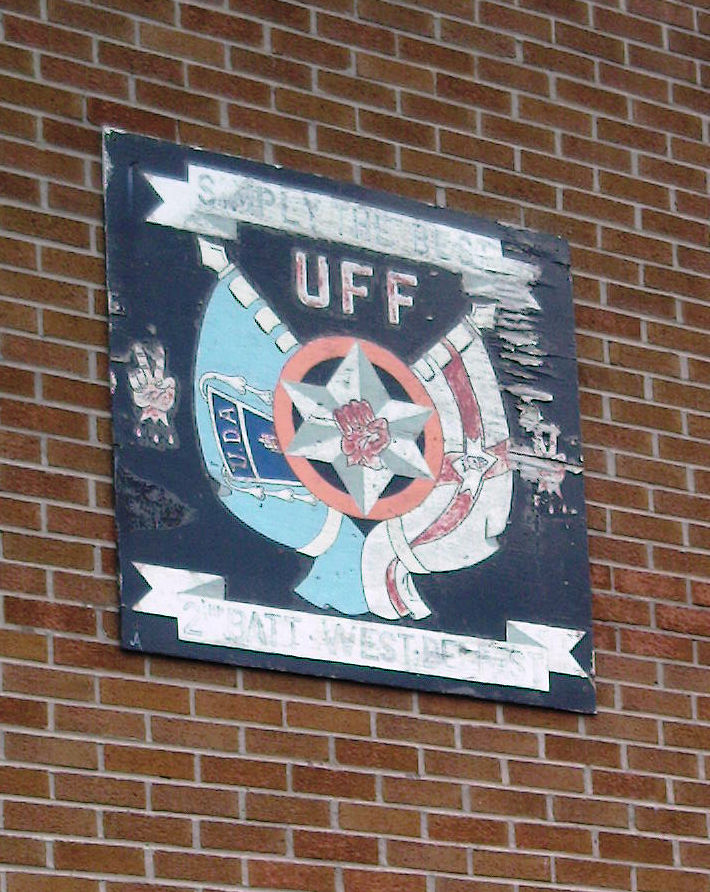

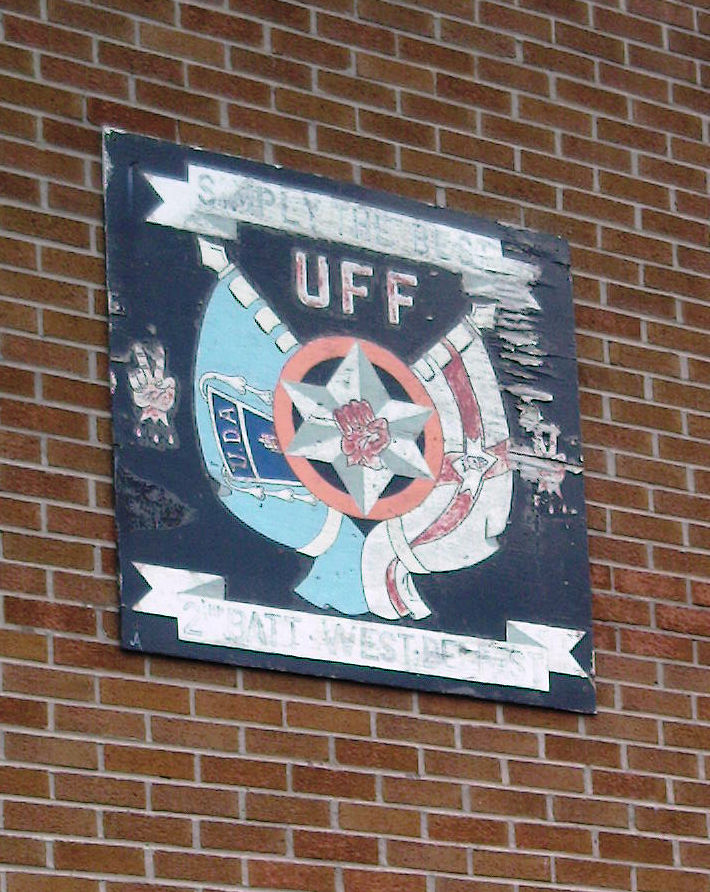

The west Belfast area also saw the formation in 1973 of the Ulster Freedom Fighters (UFF) by former Harding Smith ally John White. Modelled on the Red Hand Commando

The Red Hand Commando (RHC) is a small Ulster loyalist paramilitary group in Northern Ireland that is closely linked to the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF). Its aim was to combat Irish republicanism – particularly the Irish Republican Army (IRA ...

, the UFF was to be an armed elite of killing units to be nominally separate from the legal UDA but actually a flag of convenience under which UDA members could kill Catholics. The model soon spread from west Belfast to the rest of the UDA.

Tommy Lyttle

When Harding Smith left Northern Ireland in 1975

When Harding Smith left Northern Ireland in 1975 Tommy Lyttle

Tommy "Tucker" Lyttle (c. 1939 – 18 October 1995), was a high-ranking Ulster loyalist during the period of religious-political conflict in Northern Ireland known as "the Troubles". A member of the Ulster Defence Association (UDA) – the large ...

was chosen as his replacement as Brigadier, following a brief interlude during which John McClatchey served as leader. Under Lyttle however the West Belfast Brigade entered a period of stagnation and from being the main area of activity it fell way behind the new centres of North and South Belfast. A rare foray into murder by a member of the Brigade proved somewhat disastrous during the 1977 Ulster Workers' Council

The Ulster Workers' Council was a loyalist workers' organisation set up in Northern Ireland in 1974 as a more formalised successor to the Loyalist Association of Workers (LAW). It was formed by shipyard union leader Harry Murray and initially fail ...

strike. Kenny McClinton

Kenneth McClinton (born 1947) is a Northern Irish pastor and sometime political activist. During his early years McClinton was an active member of the Ulster Defence Association (UDA/UFF). He was a close friend of Loyalist Volunteer Force (LVF) ...

stopped a bus as part of a road blockade and entering the vehicle, shot and killed driver Harry Bradshaw, a Protestant.McKay, p. 79 This, along with press revelations that the UDA had written a letter of apology to his widow in which they enclosed a ten-pound note, helped to further undermine the already unpopular strike. During the 1980s James Craig, another former associate of Harding Smith, had been attached to the West Belfast Brigade as "fundraiser-in-chief", a role which saw the Brigade move increasingly towards racketeering. Craig particularly favoured protection racket

A protection racket is a type of racket and a scheme of organized crime perpetrated by a potentially hazardous organized crime group that generally guarantees protection outside the sanction of the law to another entity or individual from viol ...

s that targeted Belfast's building firms and gained a lot of money through these, both for the Brigade and for himself. Arrested in 1985 for racketeering, the case collapsed and he returned to the Shankill but was soon asked to leave because of his personal enrichment and he left to link up the John McMichael

John McMichael (9 January 1948 – 22 December 1987) was a Northern Irish loyalist who rose to become the most prominent and charismatic figure within the Ulster Defence Association (UDA) as the Deputy Commander and leader of its South Belf ...

's South Belfast Brigade instead. According to Billy McQuiston

William McQuiston, also known as "Twister", is an Ulster loyalist, who was a high-ranking member of the Ulster Defence Association (UDA). Leader of the organisation's A Company, Highfield, West Belfast Brigade, McQuiston spent more than 12 ye ...

, a member of the West Belfast Brigade, the activities of the Brigade during the 1980s helped to make the UDA unpopular on the Shankill as they were identified with gangsterism.

Despite this the West Belfast Brigade saw an influx of new young members in the 1980s and before long Lyttle came under pressure to give them something to do. Lyttle shared Craig's predilection for gangsterism but was less interested in murder and so turned to his intelligence officer Brian Nelson who drew up a list of leading republican targets and October 1987 Nelson dispatched a group of raw recruits to the nationalist Ballymurphy area to kill the first of these, a 66-year-old taxi driver by the name of Francisco Notorantonio. Despite appearing on the list Notorantonio had only ever been very loosely connected to the Irish Republican Army

The Irish Republican Army (IRA) is a name used by various paramilitary organisations in Ireland throughout the 20th and 21st centuries. Organisations by this name have been dedicated to irredentism through Irish republicanism, the belief tha ...

and Sinn Féin

Sinn Féin ( , ; en, " eOurselves") is an Irish republican and democratic socialist political party active throughout both the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland.

The original Sinn Féin organisation was founded in 1905 by Arthur Gri ...

and had ended his active associations with republicanism several years earlier. In fact Nelson, who was the highest-ranking British intelligence agent in the UDA, had seized on Notorantonio at the last minute after being informed by his handlers that his initial first target was actually a high-ranking British agent in the Provisional Irish Republican Army

The Irish Republican Army (IRA; ), also known as the Provisional Irish Republican Army, and informally as the Provos, was an Irish republican paramilitary organisation that sought to end British rule in Northern Ireland, facilitate Irish reun ...

known as "Stakeknife

"Stakeknife" is the code name of a high-level spy who successfully infiltrated the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) while working for the top-secret Force Research Unit (FRU) of the British Army. Reports claim that Stakeknife worked for Br ...

" (believed to be Freddie Scappaticci

Freddie Scappaticci (born c. 1946 Belfast) is a purported former high-level double agent in the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA), known by the codename " Stakeknife".

Early life

Scappaticci was born around 1946 and grew up in the Markets ...

). "Stakeknife" was seen as much too important to be killed and so a last minute switch was made. Nonetheless the killings continued, with C Company becoming the most active, under the command of William "Winkie" Dodds. They struck again, based on Nelson's list, on 10 May 1988 with the murder of Terence McDaid. This murder however was an error as the actual target had been his older brother Declan, whose striking physical resemblance to Terence meant that C Company had received the wrong photograph from Nelson. Nelson also provided details on Gerard Slane, who was killed by B Company on 22 September 1988. Slane was shot dead at his Falls Road home with the UDA claiming he was a member of the Irish People's Liberation Organisation

The Irish People's Liberation Organisation was a small Irish socialist republican paramilitary organisation formed in 1986 by disaffected and expelled members of the Irish National Liberation Army (INLA), whose factions coalesced in the aftermat ...

. The most notorious killing was that of solicitor Pat Finucane

Patrick Finucane (; 21 March 1949 – 12 February 1989) was an Irish lawyer who specialised in criminal defence work. Finucane came to prominence due to his successful challenge of the British government in several important human rights cases ...

in February 1989, carried out by brigade member Ken Barrett using information provided by RUC Special Branch

RUC Special Branch was the Special Branch of the Royal Ulster Constabulary, and was heavily involved in the British state effort during the Troubles, especially against the Provisional Irish Republican Army. It worked closely with MI5 and the Int ...

.

Lyttle was arrested as part of the Stevens Inquiries and was handed a six-year prison sentence after pleading guilty to various offences. It has been suggested that the lenience of his sentence may have been influenced by Lyttle himself being a Royal Ulster Constabulary

The Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) was the police force in Northern Ireland from 1922 to 2001. It was founded on 1 June 1922 as a successor to the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC)Richard Doherty, ''The Thin Green Line – The History of the Royal ...

agent although this has not been confirmed. The collapse of the old leadership cleared the way for younger, more militant members to take control of the Brigade and launch a new era of activity.

Emergence of Johnny Adair

The Stevens Inquiries led to a period of chaos within the West Belfast Brigade, with a rapid succession of brigadiers and a number of leading members spending time in prison. Lyttle's arrest in early 1990 saw him relinquish the role of Brigadier, whilst the allegations that he was an informer saw him disowned by the rest of the Brigade with four others following him before the year was out. Stability initially looked set when Tommy Irvine was chosen as Brigadier and he set in place a new decentralised structure in which the commanders of A, B and C companies (at the time Matt Kincaid, Jim Spence and William "Winkie" Dodds respectively) would be given a freer hand in their activities. However Irvine was arrested as part of the inquiries in August 1990 and was very briefly replaced by Ken Barrett. Barrett was quickly ousted by Lyttle's choice, his brother-in-law

The Stevens Inquiries led to a period of chaos within the West Belfast Brigade, with a rapid succession of brigadiers and a number of leading members spending time in prison. Lyttle's arrest in early 1990 saw him relinquish the role of Brigadier, whilst the allegations that he was an informer saw him disowned by the rest of the Brigade with four others following him before the year was out. Stability initially looked set when Tommy Irvine was chosen as Brigadier and he set in place a new decentralised structure in which the commanders of A, B and C companies (at the time Matt Kincaid, Jim Spence and William "Winkie" Dodds respectively) would be given a freer hand in their activities. However Irvine was arrested as part of the inquiries in August 1990 and was very briefly replaced by Ken Barrett. Barrett was quickly ousted by Lyttle's choice, his brother-in-law Billy Kennedy Billy Kennedy may refer to:

*Billy Kennedy (basketball) (born 1964), former head men's basketball coach at Texas A&M University

* Billy Kennedy (''Neighbours''), a character in the Australian soap opera ''Neighbours''

* Billy Kennedy (loyalist), se ...

but in October 1990 Jim Spence, who had also been taken into prison as part of the Stevens Inquires, assumed overall control of the Brigade. One of his first acts was to appoint an officer in overall control of the Brigade's military activities and he chose his friend Johnny Adair

John Adair (born 27 October 1963), better known as Johnny Adair or Mad Dog Adair, is an Ulster loyalist and the former leader of the "C Company", 2nd Battalion Shankill Road, West Belfast Brigade of the Ulster Freedom Fighters (UFF). This was a ...

for this role. Adair also replaced Dodds, who faced a longer spell in prison, as head of C Company.

Under Adair's direction the West Belfast Brigade became notorious for its killing spree, with his leading gunman Stephen "Top Gun" McKeag in particular becoming notorious. His first killing had actually occurred before the emergence of Adair on 11 March 1990 in the Clonard district of the Falls Road. Several more followed however with police estimated that McKeag committed at least 12 murders and former members of C Company

The Ulster Defence Association (UDA) is an Ulster loyalist paramilitary group in Northern Ireland. It was formed in September 1971 as an umbrella group for various loyalist groups and undertook an armed campaign of almost 24 years as one of ...

putting the figure even higher.

Adair in charge

Spence was arrested on charges of extortion in March 1993 and gave up the role of Brigadier with Johnny Adair succeeding him. As Brigadier, Adair continued on the same bloody path that he had followed as military commander. One victim was Noel Cardwell, a mentally sub-normal glass collector at a C Company bar, the Diamond Jubilee, who was seen as a figure of fun by Adair and his cohorts. In December 1993 Cardwell was taken to the

Spence was arrested on charges of extortion in March 1993 and gave up the role of Brigadier with Johnny Adair succeeding him. As Brigadier, Adair continued on the same bloody path that he had followed as military commander. One victim was Noel Cardwell, a mentally sub-normal glass collector at a C Company bar, the Diamond Jubilee, who was seen as a figure of fun by Adair and his cohorts. In December 1993 Cardwell was taken to the Royal Victoria Hospital, Belfast

The Royal Victoria Hospital commonly known as "the Royal", the "RVH" or "the Royal Belfast", is a hospital in Belfast, Northern Ireland. It is managed by the Belfast Health and Social Care Trust. The hospital has a Regional Virus Centre, which ...

after suffering a bad reaction when his drink was spiked with an ecstasy tablet by a member of C Company. Whilst in the hospital he was visited by members of the RUC who asked him who he had been drinking with. Cardwell named the UDA members he was with, having failed to grasp the code of secrecy governing the UDA. In order to send a message to informers, Adair had Cardwell abducted following his release from hospital and subjected to a long and brutal interrogation process. He was shot and left to bleed to death. C Company member Gary McMaster was later sentenced to life imprisonment for his part in the murder. Adair and his close ally Dodds were targeted by the IRA in October 1993 when republican intelligence witnessed the two entering Frizzell's fish shop on the Shankill Road to access West Belfast Brigade headquarters in the room above. The Shankill Road bombing

The Shankill Road bombing was carried out by the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) on 23 October 1993 and is one of the most well-known incidents of the Troubles in Northern Ireland. The IRA aimed to assassinate the leadership of the loy ...

that followed killed nine civilians and one of the bombers but Adair and Dodds had already left by the time the bomb detonated.

McKeag's killing spree continued under Adair's brigadiership, starting on 1 May 1993 when former IRA member Alan Lundy was killed Ardoyne

Ardoyne () is a working class and mainly Catholic and Irish republican district in north Belfast, Northern Ireland. It gained notoriety due to the large number of incidents during The Troubles.

Foundation

The village of Ardoyne was founded in ...

. Sean Lavery, the son of a Sinn Féin

Sinn Féin ( , ; en, " eOurselves") is an Irish republican and democratic socialist political party active throughout both the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland.

The original Sinn Féin organisation was founded in 1905 by Arthur Gri ...

Belfast City Council

Belfast City Council ( ga, Comhairle Cathrach Bhéal Feirste) is the local authority with responsibility for part of the city of Belfast, the capital and largest city of Northern Ireland. The Council serves an estimated population of (), the l ...

lor, was killed on 8 August with Marie Teresa Dowds de Mogollon killed on 30 August. and Sean Hughes killed at his Donegall Road

The Donegall Road is a residential area and road traffic thoroughfare that runs from Shaftesbury Square on what was once called the "Golden Mile" to the Falls Road in west Belfast. The road is bisected by the Westlink – M1 motorway. The lar ...

shop on 7 September. McKeag was tried for the latter murder but was acquitted due to lack of evidence. Michael Edwards was killed in Finaghy on 3 September and Paddy Mahon on 15 October before McKeag was finally arrested in connection with the Hughes murder. McKeag was soon back in action and by 1994 Dodds was close to Derek Adgey, a Royal Marine

The Corps of Royal Marines (RM), also known as the Royal Marines Commandos, are the UK's special operations capable commando force, amphibious light infantry and also one of the five fighting arms of the Royal Navy. The Corps of Royal Marine ...

who provided details of republicans to Dodds that were then used by C Company, in particular their leading gunman McKeag. McKeag would fall out of favour later in the decade, in part because of envy within C Company of his "achievements", and he was found dead in suspicious circumstances in September 2000.

On 16 May 1994 around twenty leading figures in C Company were arrested as part of an RUC operation against the notorious group. Although a number of those arrested were released without charge, Adair was imprisoned, forcing him to vacate his role as Brigadier. His close ally Winkie Dodds was named his replacement, although Adair remained in control as Dodds followed the orders he sent out from prison. Following Adair's lead, Dodds expanded the drug-dealing empire that the West Belfast Brigade had begun to develop. Adair also pursued a policy of linking up with the Loyalist Volunteer Force

The Loyalist Volunteer Force (LVF) is a small Ulster loyalist paramilitary group in Northern Ireland. It was formed by Billy Wright in 1996 when he and his unit split from the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) after breaking its ceasefire. Most of ...

(LVF) and following the Irish National Liberation Army

The Irish National Liberation Army (INLA, ga, Arm Saoirse Náisiúnta na hÉireann) is an Irish republican socialist paramilitary group formed on 10 December 1974, during the 30-year period of conflict known as "the Troubles". The group seek ...

's killing of LVF leader Billy Wright in December 1997, he sent McKeag out to wreak revenge, despite the UDA being on ceasefire. McKeag struck on 28 December by machine-gunning the Clifton Tavern in north Belfast, killing Edmund Trainor and injuring several others. He followed this on 23 January 1998 by killing Liam Conway on north Belfast's Hesketh Road. The Inner Council of the UDA brought McKeag to task for this killing but he was not disciplined, despite the murder seeing the Ulster Democratic Party

The Ulster Democratic Party (UDP) was a small loyalist political party in Northern Ireland. It was established in June 1981 as the Ulster Loyalist Democratic Party by the Ulster Defence Association (UDA), to replace the New Ulster Political Res ...

left out of all-party talks. The West Belfast Brigade meanwhile continued to assort freely with the LVF, a splinter group of the Ulster Volunteer Force

The Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) is an Ulster loyalist paramilitary group. Formed in 1965, it first emerged in 1966. Its first leader was Gusty Spence, a former British Army soldier from Northern Ireland. The group undertook an armed campaig ...

(UVF) and a bitter rival of that group, active alongside LVF members at the Drumcree conflict

The Drumcree conflict or Drumcree standoff is a dispute over yearly parades in the town of Portadown, Northern Ireland. The town is mainly Protestant and hosts numerous Protestant/loyalist marches each summer, but has a significant Catholic mi ...

. Under Adair the West Belfast Brigade moved closer to a feud with the UVF.

Feud with UVF

On 19 August 2000 the West Belfast Brigade hosted a "Loyalist Day of Culture" organised by Adair on the Lower Shankill with fellow brigadiers John Gregg, Billy McFarland,

On 19 August 2000 the West Belfast Brigade hosted a "Loyalist Day of Culture" organised by Adair on the Lower Shankill with fellow brigadiers John Gregg, Billy McFarland, Jackie McDonald

John "Jackie" McDonald (born 2 August 1947) is a Northern Irish loyalist and the incumbent Ulster Defence Association (UDA) brigadier for South Belfast, having been promoted to the rank by former UDA commander Andy Tyrie in 1988, following J ...

and Jimbo Simpson

James "Jimbo" Simpson, also known as the Bacardi Brigadier, (died 11 October 2018) was a Northern Irish loyalist paramilitary. He was most noted for his time as Brigadier of the North Belfast Ulster Defence Association (UDA). After falling from g ...

in attendance. However early in the day clashes broke out between UDA and UVF members outside the Diamond Jubilee, a UDA bar, and later UDA members attacked the UVF stronghold Rex Bar further up the road, firing shots at the UVF men trapped inside. In response, Adair drove all UVF members and their families out of the Lower Shankill and in doing so began the feud that his fellow brigadiers had hoped to avoid. Orders were sent up to A Company in Highfield by Dodds that the estate should be "cleansed" of UVF members. The UVF struck back on 21 August, killing two of Adair's allies, Jackie Coulter and Bobby Mahood, on the Crumlin Road

The Crumlin Road is a main road in north-west Belfast, Northern Ireland. The road runs from north of Belfast City Centre for about four miles to the outskirts of the city. It also forms part of the longer A52 road which leads out of Belfast to t ...

. In response C Company members burned down the headquarters of the UVF-linked Progressive Unionist Party

The Progressive Unionist Party (PUP) is a minor unionist political party in Northern Ireland. It was formed from the Independent Unionist Group operating in the Shankill area of Belfast, becoming the PUP in 1979. Linked to the Ulster Volunte ...

. Adair was arrested on 22 August 2000 whilst he and Dodds were driving down the Shankill Road. Adair was sent back to prison for breaking terms of his parole. With command reverting to Dodds, UVF member Samuel Rockett was shot and killed at his home by C Company the following night. The feud continued with 4 more being killed on both sides until an uneasy truce was made.

The militancy of the West Belfast Brigade, and in particular Adair, who had become a cult hero among loyalists, meant that the brigade enjoyed the loyalty of some UDA members outside its nominal geographic area. Within the North Belfast Brigade an influx of new young members found more to admire in Adair than in their own brigadier Jimbo Simpson, and affiliated to the West Belfast brigade despite not living in the area. Further afield a group of Shankill men had relocated to areas of North Down such as Bangor and

The militancy of the West Belfast Brigade, and in particular Adair, who had become a cult hero among loyalists, meant that the brigade enjoyed the loyalty of some UDA members outside its nominal geographic area. Within the North Belfast Brigade an influx of new young members found more to admire in Adair than in their own brigadier Jimbo Simpson, and affiliated to the West Belfast brigade despite not living in the area. Further afield a group of Shankill men had relocated to areas of North Down such as Bangor and Newtownards

Newtownards is a town in County Down, Northern Ireland. It lies at the most northern tip of Strangford Lough, 10 miles (16 km) east of Belfast, on the Ards Peninsula. It is in the Civil parishes in Ireland, civil parish of Newtownard ...

and there had found that support amongst young loyalists for Adair was so strong that they established a new D Company for the West Belfast Brigade there.Lister & Jordan, p. 329 The area was supposed to be part of the jurisdiction of the East Belfast Brigade.

Adair denouement

Expulsion

The feud had been unpopular with the other brigadiers, in particular Jackie McDonald of the South Belfast Brigade, who had emerged as the most credible rival to Adair within the UDA. Adair sought to restart the UVF feud and challenge his fellow brigadiers in September 2002, when East Belfast LVF member Stephen Warnock was killed by theRed Hand Commando

The Red Hand Commando (RHC) is a small Ulster loyalist paramilitary group in Northern Ireland that is closely linked to the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF). Its aim was to combat Irish republicanism – particularly the Irish Republican Army (IRA ...

. Adair spread a rumour that East Belfast Brigade chief Jim Gray had actually been behind the murder and as a result Gray was shot and seriously injured when he came to the Warnock family home to commiserate soon afterwards. A meeting was convened of all brigadiers in an attempt to avert a crisis, but nothing came of it as Adair refused to bend. McDonald's men followed Adair and reported that he conferred with his LVF allies in Ballysillan

Oldpark is one of the nine district electoral areas (DEA) in Belfast, Northern Ireland. Located in the North of the city, the district elects six members to Belfast City Council and contains the wards of Ardoyne; Ballysillan; Cliftonville; Lego ...

after leaving the meeting early. On this basis McDonald secured the agreement of the other brigadiers that Adair should be expelled from the UDA, along with his spokesman John White.McDonald & Cusack, ''UDA'', p. 374

Adair ignored the expulsion and erected "West Belfast UDA - Business as Usual" banners on the Shankill Road. A coterie of figures within the West Belfast Brigade, and especially Adair's C Company stronghold, remained loyal to Adair as the West Belfast Brigade split off from the rest of the UDA. However, Adair's leadership now became characterised by extreme paranoia. Mo Courtney

William Samuel "Mo" Courtney (born 8 July 1963) is a former Ulster Defence Association (UDA) activist. He was a leading figure in Johnny Adair's C Company, one of the most active sections of the UDA, before later falling out with Adair and servi ...

, who served as Adair's bodyguard, was amongst those to come under suspicion because of his friendship with the North Belfast-based Shoukri brothers, whom Adair viewed as potential rivals. Adair despatched a team to kill Courtney but his friend Donald Hodgen tipped him off and Courtney escaped the Shankill before the hit could take place. Winkie Dodds, whose role had diminished considerably after a stroke

A stroke is a medical condition in which poor blood flow to the brain causes cell death. There are two main types of stroke: ischemic, due to lack of blood flow, and hemorrhagic, due to bleeding. Both cause parts of the brain to stop functionin ...

, also split from Adair around this time after his cousin William "Muggsy" Mullan had been driven from the Shankill for associating with the Shoukris and "Fat" Jackie Thompson had led a punishment squad in a brutal attack on Dodds' brother Milton "Doddsy" Dodds.

Escalation and exile

The feud erupted on 27 December 2002 when members of the West Belfast Brigade killed mainstream UDA member Jonathan Stewart at a party, an attack that saw Adair loyalist Roy Green killed in retaliation. Adair's men then struck back on 1 February 2003, killing South East Antrim Brigade leader John Gregg and his friend Rab Carson as the two returned from watchingRangers F.C.

Rangers Football Club is a Scottish professional football club based in the Govan district of Glasgow which plays in the Scottish Premiership. Although not its official name, it is often referred to as Glasgow Rangers outside Scotland. The fou ...

Gregg's killing proved the final straw, in part because he enjoyed a stellar reputation amongst loyalists for a gun attack on Gerry Adams

Gerard Adams ( ga, Gearóid Mac Ádhaimh; born 6 October 1948) is an Irish republican politician who was the president of Sinn Féin between 13 November 1983 and 10 February 2018, and served as a Teachta Dála (TD) for Louth from 2011 to 2020 ...

in the 1980s. Adair however had a lot of bad blood with Gregg, stemming from an attack on a West Belfast Brigade member in Rathcoole and the subsequent kneecapping of the attackers by Adair's men in Gregg's area. In December 2002, the LVF had placed a bomb under Gregg's car and soon afterwards Gregg's house and that of his ally Tommy Kirkham

Tommy Kirkham is a Northern Ireland loyalist political figure and former councillor. Beginning his political career with the Democratic Unionist Party, he was then associated with the Ulster Defence Association (UDA) and the Ulster Political Resea ...

were attacked by West Belfast men. Gregg retaliated with a bomb attack on Adair's house on 8 January, two days before the West Belfast Brigade chief was returned to jail. "Fat" Jackie Thompson, who remained totally loyal to Adair, was chosen to take over as Brigadier whilst Adair was in jail.

McDonald made contact with A and B Companies of the West Belfast Brigade and told them that he intended to forcibly remove Adair. They accepted McDonald's leadership and established a headquarters at the Shankill's Heather Street Social Club, where members of C Company were invited in order to defect back to the mainstream UDA. Several members did so, with Mo Courtney amongst the most prominent of those to accept the invitation. Around 100 of McDonald's men, all heavily armed, launched an invasion of Adair's Lower Shankill stronghold in the early hours of the morning of 6 February and attacked the twenty or so members of C Company who remained loyal to Adair (who was still in prison), driving them out of Northern Ireland. As a result of this, the West Belfast Brigade was brought back into the UDA.

Post-Adair

In the immediate aftermath of Adair's removal, and with Thompson one of those to have been driven out of Northern Ireland, Mo Courtney was officially confirmed in the role of brigadier.Lister & Jordan, p. 335 He proved a transitory figure however, as a result of the murder of Adair supporter Alan McCullough. McCullough had asked Courtney if he could return from exile inBolton

Bolton (, locally ) is a large town in Greater Manchester in North West England, formerly a part of Lancashire. A former mill town, Bolton has been a production centre for textiles since Flemish people, Flemish weavers settled in the area i ...

and promised to tell the new brigadier the location of a large drugs stash and the home address of Gina Adair in return for his safety. Courtney agreed but when McCullough returned home he was taken by UDA members to Mallusk near Templepatrick

Templepatrick (; ) is a village and Civil parishes in Ireland, civil parish in County Antrim, Northern Ireland. It is northwest of Belfast, and halfway between the towns of Ballyclare and Antrim, County Antrim, Antrim. It is also close to Belfas ...

and killed on 28 May 2003. The killing was hugely unpopular due to the double-crossing nature of the attack and Courtney went into hiding in Carrickfergus

Carrickfergus ( , meaning " Fergus' rock") is a large town in County Antrim, Northern Ireland. It sits on the north shore of Belfast Lough, from Belfast. The town had a population of 27,998 at the 2011 Census. It is County Antrim's oldest t ...

for fear of retaliation. He was charged with the murder, along with Ihab Shoukri

The Shoukri brothers are a pair of Northern Irish loyalist paramilitaries. Andre Khalef Shoukri was born in 1977, the son of a Coptic Christian Egyptian father and a Northern Irish mother. He was alleged to have taken over the north Belfast Ulste ...

, a few days later. He was acquitted by a Diplock court

Diplock courts were criminal courts in Northern Ireland for non-jury trial of specified serious crimes ("scheduled offences"). They were introduced by the Northern Ireland (Emergency Provisions) Act 1973, used for political crime, political an ...

after the evidence was adjudged flawed, although a retrial was later ordered and he was ultimately given an eight-year jail sentence after pleading guilty to manslaughter

Manslaughter is a common law legal term for homicide considered by law as less culpable than murder. The distinction between murder and manslaughter is sometimes said to have first been made by the ancient Athenian lawmaker Draco in the 7th cen ...

.

Jim Spence, who had conspired with McDonald to bring about Adair's downfall, replaced Courtney as Brigadier following his arrest. Adair, who was mooting a comeback from prison, attacked Spence constantly in the press for his perceived treachery, although ultimately Adair left Belfast following his 2005 release. Seen as something of an undesirable by others in the UDA, Spence was removed as Brigadier in 2006 in favour of Matt Kincaid. As of 2015, Kincaid remains in charge of the now much less influential West Belfast Brigade.

2013 North Belfast Brigade feud

In 2013, it was reported in the ''Belfast Telegraph

The ''Belfast Telegraph'' is a daily newspaper published in Belfast, Northern Ireland, by Independent News & Media. Its editor is Eoin Brannigan. Reflecting its unionist tradition, the paper has historically been "favoured by the Protestant po ...

'' that the leadership of the West Belfast Brigade was once again at loggerheads with the rest of the organisation. According to the report, the West Belfast Brigade had become so associated with criminality and racketeering that the three other Belfast-based brigadiers, Jackie McDonald (South Belfast), Jimmy Birch (East Belfast) and John Bunting (North Belfast), no longer felt able to deal with the western leadership. Tensions had been further stoked by a graffiti campaign against Bunting's leadership on the York Road, in which expelled members of the North Belfast Brigade who had come under the wing of their counterparts in the west called for Bunting's removal as brigadier. The feud was confirmed in December 2013 when a UDA statement was released acknowledging the existence of a dissident tendency within the North Belfast Brigade but confirming support for Bunting's leadership. However, whilst the statement was signed by McDonald and Birch, no representative of the West Belfast Brigade had added their signature. The north Belfast rebels subsequently named Robert Molyneaux, a convicted killer and former friend of Bunting's closest ally John Howcroft, as their preferred choice for Brigadier. Although the feud soon died down, a series of low level tit-for-tat incidents continued, culminating in Howcroft's partner's car being burnt out in August 2014.

In September 2014 it was reported in the ''Belfast Telegraph'' that the leaders of the UDA in North, East and South Belfast, as well as the head of the Londonderry and North Antrim Brigade had met to discuss the feud as well as the schism with the West Belfast Brigade. According to the report, they agreed that West Belfast Brigade members loyal to the wider UDA should establish a new command structure for the brigade which would then take the lead in ousting Courtney, Spence and Eric McKee from their existing leadership positions. It was also stated that the West Belfast breakaway leaders had recruited Jimbo Simpson

James "Jimbo" Simpson, also known as the Bacardi Brigadier, (died 11 October 2018) was a Northern Irish loyalist paramilitary. He was most noted for his time as Brigadier of the North Belfast Ulster Defence Association (UDA). After falling from g ...

, a former North Belfast brigadier driven out of Northern Ireland over a decade earlier, and were seeking to restore him to his former role.

Brigadiers

*Charles Harding Smith

Charles Harding Smith (24 January 1931 – 1997) was a loyalist leader in Northern Ireland and the first effective leader of the Ulster Defence Association (UDA). An important figure in the Belfast-based "defence associations" that formed the ba ...

c.1971-1975

* John McClatchey 1975

* Tommy Lyttle

Tommy "Tucker" Lyttle (c. 1939 – 18 October 1995), was a high-ranking Ulster loyalist during the period of religious-political conflict in Northern Ireland known as "the Troubles". A member of the Ulster Defence Association (UDA) – the large ...

1975-1977

* Harry Killen 1977-1983

* Davy Payne

H. David "Davy" Payne (c. 1949 – March 2003) was a senior Northern Irish loyalist and a high-ranking member of the Ulster Defence Association (UDA) during the Troubles, serving as brigadier of the North Belfast Brigade. He was first in comma ...

1983-1989

* Tommy Irvine 1990

* Ken Barrett 1990

* Billy Kennedy Billy Kennedy may refer to:

*Billy Kennedy (basketball) (born 1964), former head men's basketball coach at Texas A&M University

* Billy Kennedy (''Neighbours''), a character in the Australian soap opera ''Neighbours''

* Billy Kennedy (loyalist), se ...

1990

* Jim Spence 1990-1993

* Johnny Adair

John Adair (born 27 October 1963), better known as Johnny Adair or Mad Dog Adair, is an Ulster loyalist and the former leader of the "C Company", 2nd Battalion Shankill Road, West Belfast Brigade of the Ulster Freedom Fighters (UFF). This was a ...

1993-1995

* William "Winkie" Dodds 1995-1999

* Johnny Adair 1999-2000

* William "Winkie" Dodds 2000-2002

* Johnny Adair 2002-2003

* "Fat" Jackie Thompson 2003

* Mo Courtney

William Samuel "Mo" Courtney (born 8 July 1963) is a former Ulster Defence Association (UDA) activist. He was a leading figure in Johnny Adair's C Company, one of the most active sections of the UDA, before later falling out with Adair and servi ...

2003

* Jim Spence 2003-2006

* Matt Kincaid 2006–present

Bibliography

* Lister, David and Jordan, Hugh (2004) ''Mad Dog: The Rise and Fall of Johnny Adair and 'C' Company'', Mainstream Press * McDonald, Henry and Cusack, Jim (2004), ''UDA - Inside the Heart of Loyalist Terror'', Penguin Ireland * McKay, Susan (2005), ''Northern Protestants - An Unsettled People'', Blackstaff Press * Wood, Ian S. (2006), ''Crimes of Loyalty: A History of the UDA'', Edinburgh University Press * Taylor, Peter (2000), ''Loyalists'', BloomsburyReferences

{{Loyalist Volunteer Force Ulster Defence Association The Troubles in Belfast Organised crime groups in Northern Ireland