UChicago News on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The University of Chicago (UChicago, Chicago, U of C, or UChi) is a

Money that had been raised during the 1920s and financial backing from the

Money that had been raised during the 1920s and financial backing from the

In 1999, then-President

In 1999, then-President

After the 1940s, the campus's Gothic style began to give way to modern styles. In 1955,

After the 1940s, the campus's Gothic style began to give way to modern styles. In 1955,

UNESCO World Heritage Site

as well as a National Historic Landmark, as is room 405 of the George Herbert Jones Laboratory, where

File:Snell Hitchcock1.JPG, Snell-Hitchcock, an undergraduate dormitory constructed in the early 20th century, is part of the Main Quadrangles.

File:Rockefeller Chapel Entire Structure.jpg, Rockefeller Chapel, constructed in 1928, was designed by Bertram Goodhue in the neo-Gothic style.

File:Henry Hinds Laboratory at University of Chicago5.jpg, The Henry Hinds Laboratory for Geophysical Sciences was built in 1969.

File:Ratner Athletic Center.jpg, The

PAIGE FRY, ''CHICAGO TRIBUNE'', November 16, 2021Suspect Charged in Death of University of Chicago Student

WTTW/

The university is governed by a board of trustees. The board of trustees oversees the long-term development and plans of the university and manages fundraising efforts, and is composed of 55 members including the university president. Directly beneath the president are the provost, fourteen vice presidents (including the chief financial officer,

The university is governed by a board of trustees. The board of trustees oversees the long-term development and plans of the university and manages fundraising efforts, and is composed of 55 members including the university president. Directly beneath the president are the provost, fourteen vice presidents (including the chief financial officer,

The academic bodies of the University of Chicago consist of the

The academic bodies of the University of Chicago consist of the

The College of the University of Chicago grants Bachelor of Arts and Bachelor of Science degrees in 51 academic majors and 33 minors. The college's academics are divided into five divisions: the Biological Sciences Collegiate Division, the Physical Sciences Collegiate Division, the Social Sciences Collegiate Division, the Humanities Collegiate Division, and the New Collegiate Division. The first four are sections within their corresponding graduate divisions, while the New Collegiate Division administers interdisciplinary majors and studies which do not fit in one of the other four divisions.

Undergraduate students are required to take a distribution of courses to satisfy the university's general education requirements, commonly known as the Core Curriculum. In 2012–2013, the Core classes at Chicago were limited to 17 courses, and are generally led by a full-time professor (as opposed to a

The College of the University of Chicago grants Bachelor of Arts and Bachelor of Science degrees in 51 academic majors and 33 minors. The college's academics are divided into five divisions: the Biological Sciences Collegiate Division, the Physical Sciences Collegiate Division, the Social Sciences Collegiate Division, the Humanities Collegiate Division, and the New Collegiate Division. The first four are sections within their corresponding graduate divisions, while the New Collegiate Division administers interdisciplinary majors and studies which do not fit in one of the other four divisions.

Undergraduate students are required to take a distribution of courses to satisfy the university's general education requirements, commonly known as the Core Curriculum. In 2012–2013, the Core classes at Chicago were limited to 17 courses, and are generally led by a full-time professor (as opposed to a

The university runs a number of academic institutions and programs apart from its undergraduate and postgraduate schools. It operates the

The university runs a number of academic institutions and programs apart from its undergraduate and postgraduate schools. It operates the

The University of Chicago Library system encompasses six libraries that contain a total of 11 million volumes, the 9th most among library systems in the United States. The university's main library is the Regenstein Library, which contains one of the largest collections of print volumes in the United States. The

The University of Chicago Library system encompasses six libraries that contain a total of 11 million volumes, the 9th most among library systems in the United States. The university's main library is the Regenstein Library, which contains one of the largest collections of print volumes in the United States. The

According to the

According to the  The University of Chicago has been the site of some important experiments and academic movements. In economics, the university has played an important role in shaping ideas about the

The University of Chicago has been the site of some important experiments and academic movements. In economics, the university has played an important role in shaping ideas about the

The UChicago Arts program joins academic departments and programs in the Division of the Humanities and the college, as well as professional organizations including the Court Theatre, the Oriental Institute, the

The UChicago Arts program joins academic departments and programs in the Division of the Humanities and the college, as well as professional organizations including the Court Theatre, the Oriental Institute, the

The University of Chicago hosts 19 varsity sports teams: 10 men's teams and 9 women's teams, all called the

The University of Chicago hosts 19 varsity sports teams: 10 men's teams and 9 women's teams, all called the

On-campus undergraduate students at the University of Chicago participate in a

On-campus undergraduate students at the University of Chicago participate in a

Every May since 1987, the University of Chicago has held the

Every May since 1987, the University of Chicago has held the

In 2019, the University of Chicago claimed 188,000 alumni. While the university's first president,

In 2019, the University of Chicago claimed 188,000 alumni. While the university's first president,

Notable alumni in the field of law, government and politics include

Notable alumni in the field of law, government and politics include  In economics, notable

In economics, notable

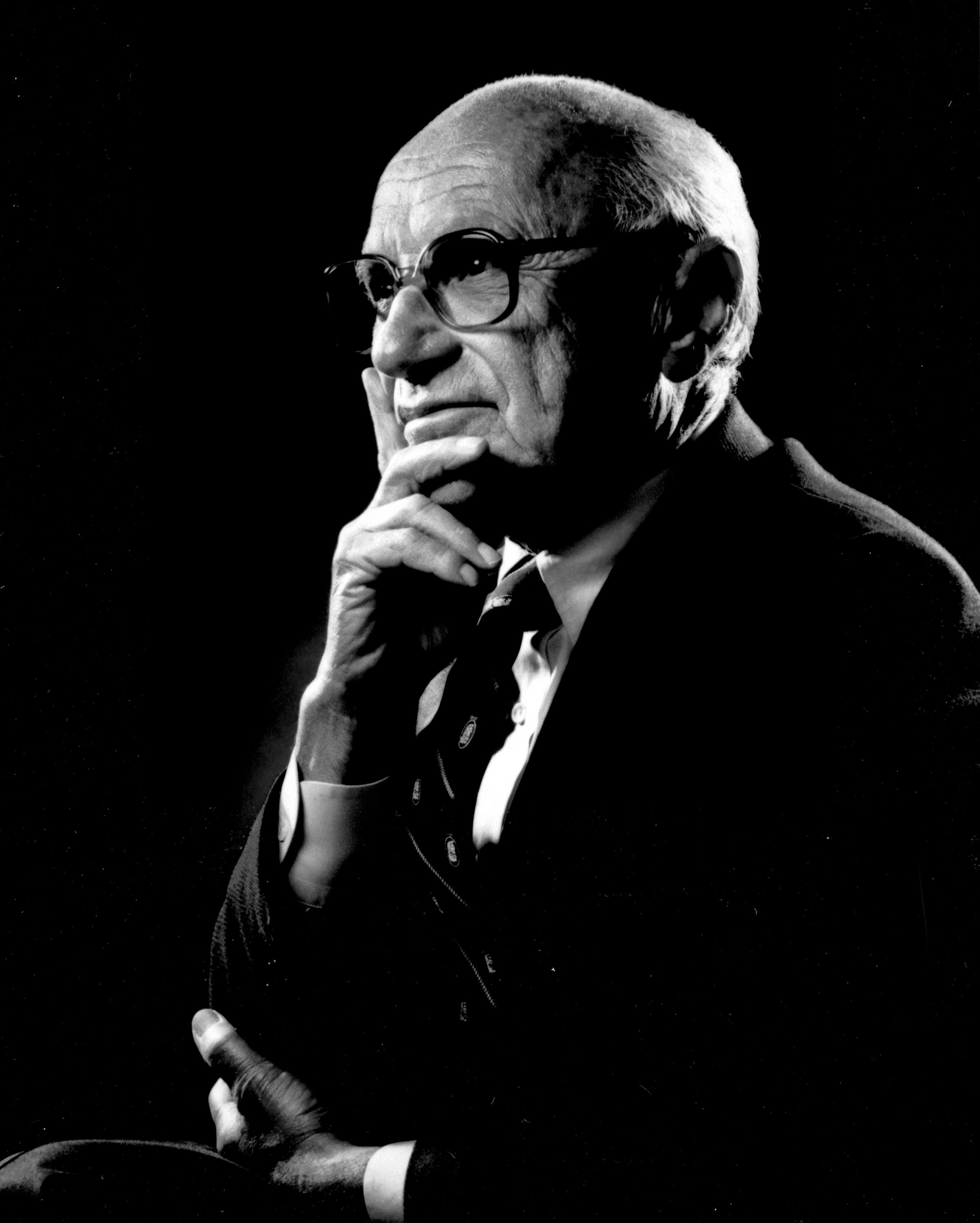

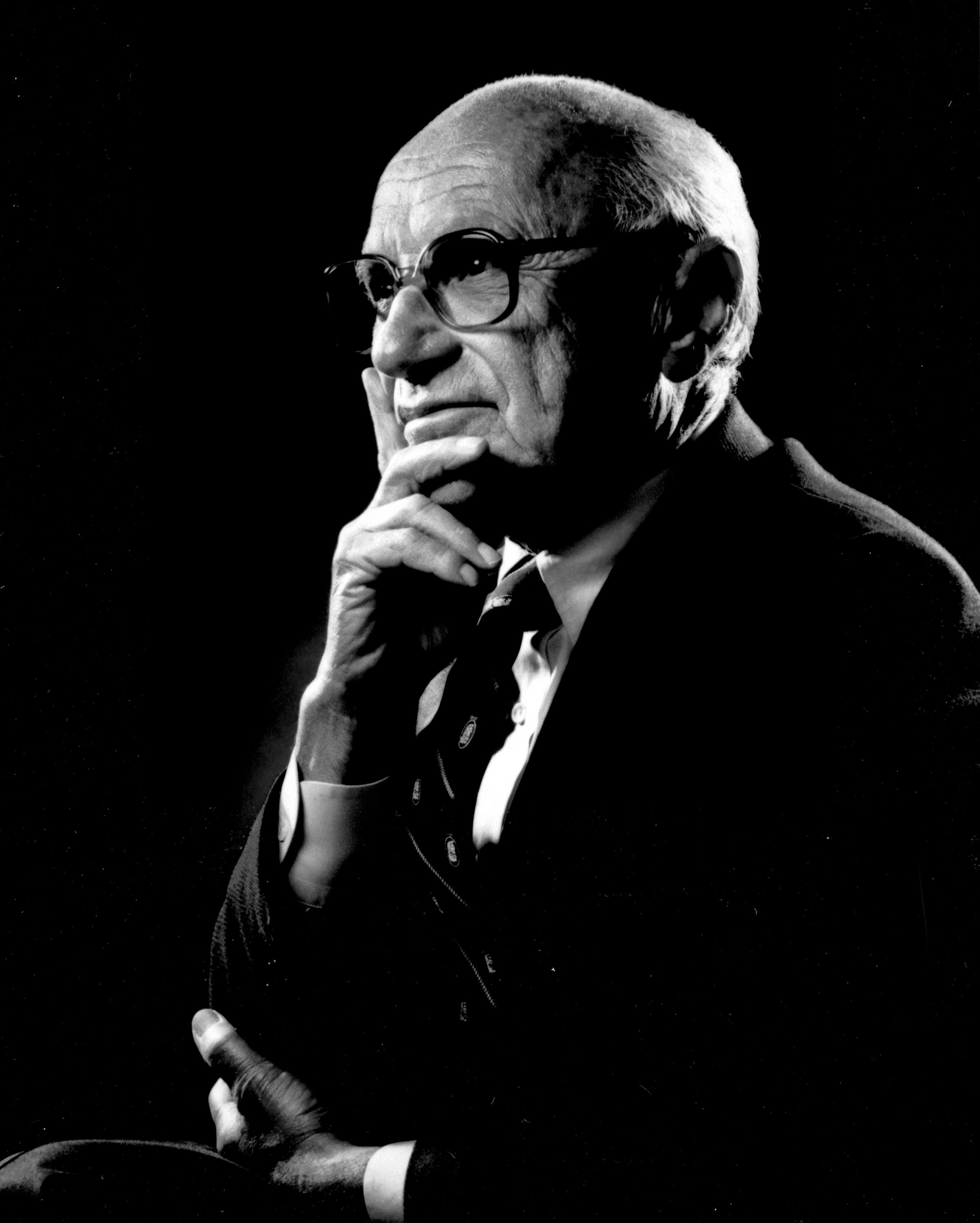

Notable faculty in economics include Friedrich Hayek, Frank Knight,

Notable faculty in economics include Friedrich Hayek, Frank Knight,

Illinois Great Places

University of Chicago Quadrangles

Society of Architectural Historians SAH ARCHIPEDIA entry on the University of Chicago Quadrangles

{{DEFAULTSORT:Chicago, University Of University of Chicago, 1890 establishments in Illinois Educational institutions established in 1890 Gothic Revival architecture in Illinois, University of Chicago Hyde Park, Chicago Institutions founded by the Rockefeller family Universities and colleges in Chicago Private universities and colleges in Illinois, University of Chicago

private

Private or privates may refer to:

Music

* " In Private", by Dusty Springfield from the 1990 album ''Reputation''

* Private (band), a Denmark-based band

* "Private" (Ryōko Hirosue song), from the 1999 album ''Private'', written and also recorde ...

research university

A research university or a research-intensive university is a university that is committed to research as a central part of its mission. They are the most important sites at which knowledge production occurs, along with "intergenerational kno ...

in Chicago, Illinois

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name ...

. Its main campus is located in Chicago's Hyde Park

Hyde Park may refer to:

Places

England

* Hyde Park, London, a Royal Park in Central London

* Hyde Park, Leeds, an inner-city area of north-west Leeds

* Hyde Park, Sheffield, district of Sheffield

* Hyde Park, in Hyde, Greater Manchester

Austra ...

neighborhood. The University of Chicago is consistently ranked among the best universities in the world and it is among the most selective in the United States.

The university is composed of an undergraduate college and five graduate research divisions, which contain all of the university's graduate programs and interdisciplinary committees. Chicago has eight professional schools: the Law School

A law school (also known as a law centre or college of law) is an institution specializing in legal education, usually involved as part of a process for becoming a lawyer within a given jurisdiction.

Law degrees Argentina

In Argentina, ...

, the Booth School of Business, the Pritzker School of Medicine, the Crown Family School of Social Work, Policy, and Practice, the Harris School of Public Policy

The University of Chicago Harris School of Public Policy, also referred to as "Harris Public Policy," is the public policy school of the University of Chicago in Chicago, Illinois, United States. It is located on the University's main campus in Hy ...

, the Divinity School, the Graham School of Continuing Liberal and Professional Studies

The University of Chicago Graham School of Continuing Liberal and Professional Studies is one of eight professional schools of the University of Chicago. The Graham School's focus is on part-time and flexible programs of study.

The Graham Scho ...

, and the Pritzker School of Molecular Engineering

The Pritzker School of Molecular Engineering (PME) is the first school of engineering at the University of Chicago. It was founded as the Institute for Molecular Engineering in 2011 by the university in partnership with Argonne National Laborator ...

. The university has additional campuses and centers in London

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a majo ...

, Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. S ...

, Beijing

}

Beijing ( ; ; ), alternatively romanized as Peking ( ), is the capital of the People's Republic of China. It is the center of power and development of the country. Beijing is the world's most populous national capital city, with over 21 ...

, Delhi

Delhi, officially the National Capital Territory (NCT) of Delhi, is a city and a union territory of India containing New Delhi, the capital of India. Straddling the Yamuna river, primarily its western or right bank, Delhi shares borders w ...

, and Hong Kong

Hong Kong ( (US) or (UK); , ), officially the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China ( abbr. Hong Kong SAR or HKSAR), is a city and special administrative region of China on the eastern Pearl River Delt ...

, as well as in downtown Chicago.

University of Chicago scholars have played a major role in the development of many academic disciplines, including economics, law, literary criticism, mathematics, physics, religion, sociology, and political science, establishing the Chicago schools in various fields. Chicago's Metallurgical Laboratory

The Metallurgical Laboratory (or Met Lab) was a scientific laboratory at the University of Chicago that was established in February 1942 to study and use the newly discovered chemical element plutonium. It researched plutonium's chemistry and m ...

produced the world's first man-made, self-sustaining nuclear reaction in Chicago Pile-1

Chicago Pile-1 (CP-1) was the world's first artificial nuclear reactor. On 2 December 1942, the first human-made self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction was initiated in CP-1, during an experiment led by Enrico Fermi. The secret development of t ...

beneath the viewing stands of the university's Stagg Field

Amos Alonzo Stagg Field is the name of two successive football fields for the University of Chicago. Beyond sports, the first Stagg Field (1893–1957) is remembered for its role in a landmark scientific achievement of Enrico Fermi and the Metall ...

. Advances in chemistry led to the "radiocarbon revolution" in the carbon-14 dating

Radiocarbon dating (also referred to as carbon dating or carbon-14 dating) is a method for determining the age of an object containing organic material by using the properties of radiocarbon, a radioactive isotope of carbon.

The method was dev ...

of ancient life and objects. The university research efforts include administration of Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory and Argonne National Laboratory

Argonne National Laboratory is a science and engineering research United States Department of Energy National Labs, national laboratory operated by University of Chicago, UChicago Argonne LLC for the United States Department of Energy. The facil ...

, as well as the Marine Biological Laboratory. The university is also home to the University of Chicago Press

The University of Chicago Press is the largest and one of the oldest university presses in the United States. It is operated by the University of Chicago and publishes a wide variety of academic titles, including ''The Chicago Manual of Style'', ...

, the largest university press in the United States.

The University of Chicago's students, faculty, and staff include 97 Nobel laureates—among the highest of any university in the world. The university's faculty members and alumni also include 10 Fields Medalists, 4 Turing Award winners, 52 MacArthur Fellows

The MacArthur Fellows Program, also known as the MacArthur Fellowship and commonly but unofficially known as the "Genius Grant", is a prize awarded annually by the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation typically to between 20 and 30 ind ...

, 26 Marshall Scholars, 53 Rhodes Scholars

The Rhodes Scholarship is an international postgraduate award for students to study at the University of Oxford, in the United Kingdom.

Established in 1902, it is the oldest graduate scholarship in the world. It is considered among the world' ...

, 27 Pulitzer Prize

The Pulitzer Prize () is an award for achievements in newspaper, magazine, online journalism, literature, and musical composition within the United States. It was established in 1917 by provisions in the will of Joseph Pulitzer, who had made h ...

winners, 20 National Humanities Medal

The National Humanities Medal is an American award that annually recognizes several individuals, groups, or institutions for work that has "deepened the nation's understanding of the humanities, broadened our citizens' engagement with the human ...

ists, 29 living billionaire graduates, and eight Olympic medalists.

History

Early years

The University of Chicago was incorporated as acoeducational

Mixed-sex education, also known as mixed-gender education, co-education, or coeducation (abbreviated to co-ed or coed), is a system of education where males and females are educated together. Whereas single-sex education was more common up to t ...

institution in 1890 by the American Baptist Education Society, using $400,000 donated to the ABES to supplement a $600,000 donation from Standard Oil

Standard Oil Company, Inc., was an American oil production, transportation, refining, and marketing company that operated from 1870 to 1911. At its height, Standard Oil was the largest petroleum company in the world, and its success made its co-f ...

co-founder John D. Rockefeller

John Davison Rockefeller Sr. (July 8, 1839 – May 23, 1937) was an American business magnate and philanthropist. He has been widely considered the wealthiest American of all time and the richest person in modern history. Rockefeller was ...

, and including land donated by Marshall Field. While the Rockefeller donation provided money for academic operations and long-term endowment, it was stipulated that such money could not be used for buildings. The Hyde Park

Hyde Park may refer to:

Places

England

* Hyde Park, London, a Royal Park in Central London

* Hyde Park, Leeds, an inner-city area of north-west Leeds

* Hyde Park, Sheffield, district of Sheffield

* Hyde Park, in Hyde, Greater Manchester

Austra ...

campus was financed by donations from wealthy Chicagoans like Silas B. Cobb

Silas Bowman Cobb (Montpelier, Vermont, January 23, 1812 - Chicago, April 5, 1900) was an American industrialist and pioneer who made his fortune through business and real estate ventures primarily in Chicago, Illinois. Arriving in 1833, Cobb was ...

who provided the funds for the campus' first building, Cobb Lecture Hall

The University of Chicago (UChicago, Chicago, U of C, or UChi) is a private research university in Chicago, Illinois. Its main campus is located in Chicago's Hyde Park neighborhood. The University of Chicago is consistently ranked among the bes ...

, and matched Marshall Field's pledge of $100,000. Other early benefactors included businessmen Charles L. Hutchinson

Charles Lawrence Hutchinson (March 7, 1854 – October 7, 1924) was a prominent Chicago business leader and philanthropist who is best remembered today as the founding and long-time president of the Art Institute of Chicago.

Background

Hutchi ...

(trustee, treasurer and donor of Hutchinson Commons

Hutchinson Commons (also known as Hutchinson Hall) at the University of Chicago is modeled, nearly identically, on the hall of Christ Church, one of Oxford University's constituent colleges. The great room (or main dining room) measures 115 feet b ...

), Martin A. Ryerson

Martin A. Ryerson (1856–1932) was an American, lawyer, businessman, philanthropist and art collector. Heir to a considerable fortune, he was a lumber manufacturer and corporate director. He became the richest man in Chicago by the age of 36. ...

(president of the board of trustees and donor of the Ryerson Physical Laboratory) Adolphus Clay Bartlett

Adolf (also spelt Adolph or Adolphe, Adolfo and when Latinised Adolphus) is a given name used in German-speaking countries, Scandinavia, the Netherlands and Flanders, France, Italy, Spain, Portugal, Latin America and to a lesser extent in var ...

and Leon Mandel, who funded the construction of the gymnasium and assembly hall, and George C. Walker of the Walker Museum, a relative of Cobb who encouraged his inaugural donation for facilities.

The Hyde Park campus continued the legacy of the original university of the same name, which had closed in the 1880s after its campus was foreclosed on. What became known as the Old University of Chicago

The Old University of Chicago was the legal name given in 1890 to the University of Chicago's first incorporation.

The school, founded in 1856 by Baptist church leaders, was originally called the "University of Chicago" (or, interchangeably, "Ch ...

had been founded by a small group of Baptist

Baptists form a major branch of Protestantism distinguished by baptizing professing Christian believers only (believer's baptism), and doing so by complete immersion. Baptist churches also generally subscribe to the doctrines of soul compete ...

educators in 1856 through a land endowment from Senator Stephen A. Douglas

Stephen Arnold Douglas (April 23, 1813 – June 3, 1861) was an American politician and lawyer from Illinois. A senator, he was one of two nominees of the badly split Democratic Party for president in the 1860 presidential election, which wa ...

. After a fire, it closed in 1886. Alumni from the Old University of Chicago are recognized as alumni of the present University of Chicago. The university's depiction on its coat of arms of a phoenix rising from the ashes is a reference to the fire, foreclosure, and demolition of the Old University of Chicago campus. As an homage to this pre-1890 legacy, a single stone from the rubble of the original Douglas Hall on 34th Place was brought to the current Hyde Park location and set into the wall of the Classics Building. These connections have led the dean of the college and University of Chicago and professor of history John Boyer to conclude that the University of Chicago has, "a plausible genealogy as a pre–Civil War institution".

William Rainey Harper

William Rainey Harper (July 24, 1856 – January 10, 1906) was an American academic leader, an accomplished semiticist, and Baptist clergyman. Harper helped to establish both the University of Chicago and Bradley University and served as the fi ...

became the university's president on July 1, 1891, and the Hyde Park campus opened for classes on October 1, 1892. Harper worked on building up the faculty and in two years he had a faculty of 120, including eight former university or college presidents. Harper was an accomplished scholar ( Semiticist) and a member of the Baptist clergy who believed that a great university should maintain the study of faith as a central focus. To fulfill this commitment, he brought the Baptist seminary that had begun as an independent school "alongside" the Old University of Chicago and separated from the old school decades earlier to Morgan Park. This became the Divinity School in 1891, the first professional school at the University of Chicago.

Harper recruited acclaimed Yale baseball and football player Amos Alonzo Stagg from the Young Men's Christian Association

YMCA, sometimes regionally called the Y, is a worldwide youth organization based in Geneva, Switzerland, with more than 64 million beneficiaries in 120 countries. It was founded on 6 June 1844 by George Williams in London, originally ...

training school at Springfield

Springfield may refer to:

* Springfield (toponym), the place name in general

Places and locations Australia

* Springfield, New South Wales (Central Coast)

* Springfield, New South Wales (Snowy Monaro Regional Council)

* Springfield, Queenslan ...

to coach the school's football program. Stagg was given a position on the faculty, the first such athletic position in the United States. While coaching at the university, Stagg invented the numbered football jersey, the huddle, and the lighted playing field. Stagg is the namesake of the university's Stagg Field

Amos Alonzo Stagg Field is the name of two successive football fields for the University of Chicago. Beyond sports, the first Stagg Field (1893–1957) is remembered for its role in a landmark scientific achievement of Enrico Fermi and the Metall ...

.

The business school

A business school is a university-level institution that confers degrees in business administration or management. A business school may also be referred to as school of management, management school, school of business administration, o ...

was founded in 1898, and the law school

A law school (also known as a law centre or college of law) is an institution specializing in legal education, usually involved as part of a process for becoming a lawyer within a given jurisdiction.

Law degrees Argentina

In Argentina, ...

was founded in 1902. Harper died in 1906 and was replaced by a succession of three presidents whose tenures lasted until 1929. During this period, the Oriental Institute was founded to support and interpret archeological

Archaeology or archeology is the scientific study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of artifacts, architecture, biofacts or ecofacts, sites, and cultural landscape ...

work in what was then called the Near East.

In the 1890s, the university, fearful that its vast resources would injure smaller schools by drawing away good students, affiliated with several regional colleges and universities: Des Moines College

Des is a masculine given name, mostly a short form (hypocorism) of Desmond. People named Des include:

People

* Des Buckingham, English football manager

* Des Corcoran, (1928–2004), Australian politician

* Des Dillon (disambiguation), severa ...

, Kalamazoo College, Butler University, and Stetson University. In 1896, the university affiliated with Shimer College in Mount Carroll, Illinois. Under the terms of the affiliation, the schools were required to have courses of study comparable to those at the university, to notify the university early of any contemplated faculty appointments or dismissals, to make no faculty appointment without the university's approval, and to send copies of examinations for suggestions. The University of Chicago agreed to confer a degree on any graduating senior from an affiliated school who made a grade of A for all four years, and on any other graduate who took twelve weeks additional study at the University of Chicago. A student or faculty member of an affiliated school was entitled to free tuition at the University of Chicago, and Chicago students were eligible to attend an affiliated school on the same terms and receive credit for their work. The University of Chicago also agreed to provide affiliated schools with books and scientific apparatus and supplies at cost; special instructors and lecturers without cost except for travel expenses; and a copy of every book and journal published by the University of Chicago Press

The University of Chicago Press is the largest and one of the oldest university presses in the United States. It is operated by the University of Chicago and publishes a wide variety of academic titles, including ''The Chicago Manual of Style'', ...

at no cost. The agreement provided that either party could terminate the affiliation on proper notice. Several University of Chicago professors disliked the program, as it involved uncompensated additional labor on their part, and they believed it cheapened the academic reputation of the university. The program passed into history by 1910.

1920s–1980s

In 1929, the university's fifth president, 30-year-old legal philosophy scholar Robert Maynard Hutchins, took office. The university underwent many changes during his 24-year tenure. Hutchins reformed the undergraduate college's liberal-arts curriculum known as the Common Core, organized the university's graduate work into four divisions, and eliminated varsity football from the university in an attempt to emphasize academics over athletics. During his term, the University of Chicago Hospitals (now called the University of Chicago Medical Center) finished construction and enrolled their first medical students. Also, the philosophy orientedCommittee on Social Thought

The John U. Nef Committee on Social Thought is one of several PhD-granting committees at the University of Chicago. It was started in 1941 by historian John Ulric Nef along with economist Frank Knight, anthropologist Robert Redfield, and Univers ...

, an institution distinctive of the university, was created.

Money that had been raised during the 1920s and financial backing from the

Money that had been raised during the 1920s and financial backing from the Rockefeller Foundation

The Rockefeller Foundation is an American private foundation and philanthropic medical research and arts funding organization based at 420 Fifth Avenue, New York City. The second-oldest major philanthropic institution in America, after the Carneg ...

helped the school to survive through the Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

. Nonetheless, in 1933, Hutchins proposed an unsuccessful plan to merge the University of Chicago and Northwestern University

Northwestern University is a private research university in Evanston, Illinois. Founded in 1851, Northwestern is the oldest chartered university in Illinois and is ranked among the most prestigious academic institutions in the world.

Charte ...

into a single university. During World War II, the university's Metallurgical Laboratory

The Metallurgical Laboratory (or Met Lab) was a scientific laboratory at the University of Chicago that was established in February 1942 to study and use the newly discovered chemical element plutonium. It researched plutonium's chemistry and m ...

made ground-breaking contributions to the Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development undertaking during World War II that produced the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States with the support of the United Kingdom and Canada. From 1942 to 1946, the project w ...

. The university was the site of the first isolation of plutonium

Plutonium is a radioactive chemical element with the symbol Pu and atomic number 94. It is an actinide metal of silvery-gray appearance that tarnishes when exposed to air, and forms a dull coating when oxidized. The element normally exhibi ...

and of the creation of the first artificial, self-sustained nuclear reaction by Enrico Fermi

Enrico Fermi (; 29 September 1901 – 28 November 1954) was an Italian (later naturalized American) physicist and the creator of the world's first nuclear reactor, the Chicago Pile-1. He has been called the "architect of the nuclear age" and ...

in 1942.

It has been noted that the university did not provide standard oversight regarding Bruno Bettelheim and his tenure as director of the Orthogenic School for Disturbed Children from 1944 to 1973.

In the early 1950s, student applications declined as a result of increasing crime and poverty in the Hyde Park neighborhood. In response, the university became a major sponsor of a controversial urban renewal project for Hyde Park, which profoundly affected both the neighborhood's architecture and street plan. During this period the university, like Shimer College and 10 others, adopted an early entrant program that allowed very young students to attend college; also, students enrolled at Shimer were enabled to transfer automatically to the University of Chicago after their second year, having taken comparable or identical examinations and courses.

The university experienced its share of student unrest during the 1960s, beginning in 1962 when then-freshman Bernie Sanders

Bernard Sanders (born September8, 1941) is an American politician who has served as the junior United States senator from Vermont since 2007. He was the U.S. representative for the state's at-large congressional district from 1991 to 2007 ...

helped lead a 15-day sit-in at the college's administration building in a protest over the university's off-campus rental policies. After continued turmoil, a university committee in 1967 issued what became known as the Kalven Report. The report, a two-page statement of the university's policy in "social and political action," declared that "To perform its mission in the society, a university must sustain an extraordinary environment of freedom of inquiry and maintain an independence from political fashions, passions, and pressures." The report has since been used to justify decisions such as the university's refusal to divest from South Africa in the 1980s and Darfur in the late 2000s.

In 1969, more than 400 students, angry about the dismissal of a popular professor, Marlene Dixon

The Democratic Workers Party was a United States Marxist–Leninist party based in California headed by former professor Marlene Dixon, lasting from 1974–1987. One member, Janja Lalich, later became a widely cited researcher on cults. She charac ...

, occupied the Administration Building for two weeks. After the sit-in ended, when Dixon turned down a one-year reappointment, 42 students were expelled and 81 were suspended, the most severe response to student occupations of any American university during the student movement.

In 1978, history scholar Hanna Holborn Gray, then the provost and acting president of Yale University

Yale University is a private research university in New Haven, Connecticut. Established in 1701 as the Collegiate School, it is the third-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and among the most prestigious in the wo ...

, became President of the University of Chicago, a position she held for 15 years. She was the first woman in the United States to hold the presidency of a major university.

1990s–2010s

In 1999, then-President

In 1999, then-President Hugo Sonnenschein

Hugo Sonnenschein (pseudonym: ''Sonka, Hugo Sonka'') (May 25, 1889, Kyjov, – July 20, 1953, Mírov) was an Austrian writer from Bohemia. He contributed to the Czech-language Communist newspaper ''Průkopník svobody

''Průkopník svobody'' ('Pi ...

announced plans to relax the university's famed core curriculum, reducing the number of required courses from 21 to 15. When ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'', ''The Economist

''The Economist'' is a British weekly newspaper printed in demitab format and published digitally. It focuses on current affairs, international business, politics, technology, and culture. Based in London, the newspaper is owned by The Econo ...

'', and other major news outlets picked up this story, the university became the focal point of a national debate on education. The changes were ultimately implemented, but the controversy played a role in Sonnenschein's decision to resign in 2000.

From the mid-2000s, the university began a number of multimillion-dollar expansion projects. In 2008, the University of Chicago announced plans to establish the Milton Friedman Institute, which attracted both support and controversy from faculty members and The institute would cost around $200 million and occupy the buildings of the Chicago Theological Seminary. During the same year, investor David G. Booth

David Gilbert Booth (born 1946) is an American businessman, investor, and philanthropist. He is the executive chairman of Dimensional Fund Advisors, which he co-founded with Rex Sinquefield.

Career

Booth graduated from Lawrence High School in ...

donated $300 million to the university's Booth School of Business, which is the largest gift in the university's history and the largest gift ever to any business school. In 2009, planning or construction on several new buildings, half of which cost $100 million or more, was underway. Since 2011, major construction projects have included the Jules and Gwen Knapp Center for Biomedical Discovery, a ten-story medical research center, and further additions to the medical campus of the University of Chicago Medical Center. In 2014 the university launched the public phase of a $4.5 billion fundraising campaign. In September 2015, the university received $100 million from The Pearson Family Foundation to establish The Pearson Institute for the Study and Resolution of Global Conflicts and The Pearson Global Forum at the Harris School of Public Policy

The University of Chicago Harris School of Public Policy, also referred to as "Harris Public Policy," is the public policy school of the University of Chicago in Chicago, Illinois, United States. It is located on the University's main campus in Hy ...

.

In 2019, the university created its first school in three decades, the Pritzker School of Molecular Engineering

The Pritzker School of Molecular Engineering (PME) is the first school of engineering at the University of Chicago. It was founded as the Institute for Molecular Engineering in 2011 by the university in partnership with Argonne National Laborator ...

.

Campus

Main campus

The main campus of the University of Chicago consists of in the Chicago neighborhoods ofHyde Park

Hyde Park may refer to:

Places

England

* Hyde Park, London, a Royal Park in Central London

* Hyde Park, Leeds, an inner-city area of north-west Leeds

* Hyde Park, Sheffield, district of Sheffield

* Hyde Park, in Hyde, Greater Manchester

Austra ...

and Woodlawn, approximately eight miles (12 km) south of downtown Chicago

''Downtown'' is a term primarily used in North America by English speakers to refer to a city's sometimes commercial, cultural and often the historical, political and geographic heart. It is often synonymous with its central business district ...

. The northern and southern portions of campus are separated by the Midway Plaisance, a large, linear park created for the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition

The World's Columbian Exposition (also known as the Chicago World's Fair) was a world's fair held in Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordi ...

. In 2011, Travel+Leisure

''Travel + Leisure'' is a travel magazine based in New York City, New York. Published 12 times a year, it has 4.8 million readers, according to its corporate media kit. It is published by Dotdash Meredith, a subsidiary of IAC, with trademark rig ...

listed the university as one of the most beautiful college campuses in the United States.

The first buildings of the campus, which make up what is now known as the Main Quadrangles, were part of a master plan conceived by two University of Chicago trustees and plotted by Chicago architect Henry Ives Cobb

Henry Ives Cobb (August 19, 1859 – March 27, 1931) was an architect from the United States. Based in Chicago in the last decades of the 19th century, he was known for his designs in the Richardsonian Romanesque and Victorian Gothic styles. ...

. The Main Quadrangles consist of six quadrangles, each surrounded by buildings, bordering one larger quadrangle. The buildings of the Main Quadrangles were designed by Cobb, Shepley, Rutan and Coolidge, Holabird & Roche, and other architectural firms in a mixture of the Victorian Gothic and Collegiate Gothic

Collegiate Gothic is an architectural style subgenre of Gothic Revival architecture, popular in the late-19th and early-20th centuries for college and high school buildings in the United States and Canada, and to a certain extent Europ ...

styles, patterned on the colleges of the University of Oxford. (Mitchell Tower, for example, is modeled after Oxford's Magdalen Tower, and the university Commons, Hutchinson Hall

Hutchinson Commons (also known as Hutchinson Hall) at the University of Chicago is modeled, nearly identically, on the hall of Christ Church, one of Oxford University's constituent colleges. The great room (or main dining room) measures 115 feet b ...

, replicates Christ Church Hall.) In celebration of the 2018 Illinois Bicentennial, the University of Chicago Quadrangles were selected as one of the Illinois 200 Great Places by the American Institute of Architects

The American Institute of Architects (AIA) is a professional organization for architects in the United States. Headquartered in Washington, D.C., the AIA offers education, government advocacy, community redevelopment, and public outreach to su ...

Illinois component (AIA Illinois).

After the 1940s, the campus's Gothic style began to give way to modern styles. In 1955,

After the 1940s, the campus's Gothic style began to give way to modern styles. In 1955, Eero Saarinen

Eero Saarinen (, ; August 20, 1910 – September 1, 1961) was a Finnish-American architect and industrial designer noted for his wide-ranging array of designs for buildings and monuments. Saarinen is best known for designing the General Motors ...

was contracted to develop a second master plan, which led to the construction of buildings both north and south of the Midway, including the Laird Bell Law Quadrangle (a complex designed by Saarinen); a series of arts buildings; a building designed by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe

Ludwig Mies van der Rohe ( ; ; born Maria Ludwig Michael Mies; March 27, 1886August 17, 1969) was a German-American architect. He was commonly referred to as Mies, his surname. Along with Alvar Aalto, Le Corbusier, Walter Gropius and Frank Lloyd ...

for the university's School of Social Service Administration, a building which is to become the home of the Harris School of Public Policy

The University of Chicago Harris School of Public Policy, also referred to as "Harris Public Policy," is the public policy school of the University of Chicago in Chicago, Illinois, United States. It is located on the University's main campus in Hy ...

by Edward Durrell Stone

Edward Durell Stone (March 9, 1902 – August 6, 1978) was an American architect known for the formal, highly decorative buildings he designed in the 1950s and 1960s. His works include the Museum of Modern Art, in New York City, the Museo de A ...

, and the Regenstein Library, the largest building on campus, a brutalist

Brutalist architecture is an architectural style that emerged during the 1950s in the United Kingdom, among the reconstruction projects of the post-war era. Brutalist buildings are characterised by Minimalism (art), minimalist constructions th ...

structure designed by Walter Netsch

Walter A. Netsch (February 23, 1920 – June 15, 2008) was an American architect based in Chicago. He was most closely associated with the brutalist style of architecture as well as with the firm of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill. His signature aes ...

of the Chicago firm Skidmore, Owings & Merrill

Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (SOM) is an American architectural, urban planning and engineering firm. It was founded in 1936 by Louis Skidmore and Nathaniel A. Owings, Nathaniel Owings in Chicago, Illinois. In 1939, they were joined by engineer Jo ...

. Another master plan, designed in 1999 and updated in 2004, produced the Gerald Ratner Athletics Center

The Gerald Ratner Athletics Center is a $51 million athletics facility within the University of Chicago campus in the Hyde Park community area on the South Side of Chicago, Illinois in the United States. The building was named after University ...

(2003), the Max Palevsky Residential Commons

Housing at the University of Chicago includes seven residence halls that are divided into 48 houses. Each house has an average of 70 students. Freshmen and sophomores must live on-campus. Limited on-campus housing is available to juniors and senior ...

(2001), South Campus Residence Hall

Housing at the University of Chicago includes seven residence halls that are divided into 48 houses. Each house has an average of 70 students. Freshmen and sophomores must live on-campus. Limited on-campus housing is available to juniors and senior ...

and dining commons (2009), a new children's hospital, and other construction, expansions, and restorations. In 2011, the university completed the glass dome-shaped Joe and Rika Mansueto Library

The Joe and Rika Mansueto Library is the newest library of the University of Chicago, named after alumni Joe Mansueto and Rika Mansueto. The library has a capacity of 3.5 million volumes under an elliptical dome. It was designed by Helmut Jahn.

H ...

, which provides a grand reading room for the university library and prevents the need for an off-campus book depository.

The site of Chicago Pile-1

Chicago Pile-1 (CP-1) was the world's first artificial nuclear reactor. On 2 December 1942, the first human-made self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction was initiated in CP-1, during an experiment led by Enrico Fermi. The secret development of t ...

is a National Historic Landmark

A National Historic Landmark (NHL) is a building, district, object, site, or structure that is officially recognized by the United States government for its outstanding historical significance. Only some 2,500 (~3%) of over 90,000 places listed ...

and is marked by the Henry Moore

Henry Spencer Moore (30 July 1898 – 31 August 1986) was an English artist. He is best known for his semi- abstract monumental bronze sculptures which are located around the world as public works of art. As well as sculpture, Moore produced ...

sculpture ''Nuclear Energy

Nuclear energy may refer to:

*Nuclear power, the use of sustained nuclear fission or nuclear fusion to generate heat and electricity

* Nuclear binding energy, the energy needed to fuse or split a nucleus of an atom

*Nuclear potential energy

...

''. Robie House, a Frank Lloyd Wright

Frank Lloyd Wright (June 8, 1867 – April 9, 1959) was an American architect, designer, writer, and educator. He designed more than 1,000 structures over a creative period of 70 years. Wright played a key role in the architectural movements o ...

building acquired by the university in 1963, is UNESCO World Heritage Site

as well as a National Historic Landmark, as is room 405 of the George Herbert Jones Laboratory, where

Glenn T. Seaborg

Glenn Theodore Seaborg (; April 19, 1912February 25, 1999) was an American chemist whose involvement in the synthesis, discovery and investigation of ten transuranium elements earned him a share of the 1951 Nobel Prize in Chemistry. His work in ...

and his team were the first to isolate plutonium. Hitchcock Hall

Sir Alfred Joseph Hitchcock (13 August 1899 – 29 April 1980) was an English filmmaker. He is widely regarded as one of the most influential figures in the history of cinema. In a career spanning six decades, he directed over 50 featur ...

, an undergraduate dormitory, is on the National Register of Historic Places

The National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) is the United States federal government's official list of districts, sites, buildings, structures and objects deemed worthy of preservation for their historical significance or "great artistic v ...

. Resource Name = Hitchcock, Charles, Hall; Reference Number = 74000751

Gerald Ratner Athletics Center

The Gerald Ratner Athletics Center is a $51 million athletics facility within the University of Chicago campus in the Hyde Park community area on the South Side of Chicago, Illinois in the United States. The building was named after University ...

, opened in 2003 and designed by Cesar Pelli, houses the volleyball, wrestling, swimming, and basketball teams.

Safety

In November 2021 a university graduate was robbed and fatally shot on a sidewalk in a residential area in Hyde Park near campus;University of Chicago international students rally to demand safety upgrades a week after fatal shooting of recent grad. ‘The next one ... could be anyone in this crowd.’PAIGE FRY, ''CHICAGO TRIBUNE'', November 16, 2021Suspect Charged in Death of University of Chicago Student

WTTW/

Associated Press

The Associated Press (AP) is an American non-profit news agency headquartered in New York City. Founded in 1846, it operates as a cooperative, unincorporated association. It produces news reports that are distributed to its members, U.S. newspa ...

, November 13, 2021 a total of three University of Chicago students were killed by gunfire incidents in 2021. These incidents prompted student protests and an open letter to university leadership signed by more than 300 faculty members.

Satellite campuses

The university also maintains facilities apart from its main campus. The university's Booth School of Business maintains campuses inHong Kong

Hong Kong ( (US) or (UK); , ), officially the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China ( abbr. Hong Kong SAR or HKSAR), is a city and special administrative region of China on the eastern Pearl River Delt ...

, London

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a majo ...

, and the downtown Streeterville

Streeterville is a neighborhood in the Near North Side community area of Chicago, Illinois, United States, north of the Chicago River. It is bounded by the river on the south, the Magnificent Mile portion of Michigan Avenue on the west, and ...

neighborhood of Chicago. The Center in Paris, a campus located on the left bank of the Seine

)

, mouth_location = Le Havre/Honfleur

, mouth_coordinates =

, mouth_elevation =

, progression =

, river_system = Seine basin

, basin_size =

, tributaries_left = Yonne, Loing, Eure, Risle

, tributarie ...

in Paris, hosts various undergraduate and graduate study programs. In fall 2010, the university opened a center in Beijing, near Renmin University

The Renmin University of China (RUC; ) is a national key public research university in Beijing, China. The university is affiliated to the Ministry of Education, and co-funded by the Ministry and the Beijing Municipal People's Government.

RUC ...

's campus in Haidian District. The most recent additions are a center in New Delhi

New Delhi (, , ''Naī Dillī'') is the capital of India and a part of the National Capital Territory of Delhi (NCT). New Delhi is the seat of all three branches of the government of India, hosting the Rashtrapati Bhavan, Parliament House ...

, India, which opened in 2014, and a center in Hong Kong which opened in 2015.

Administration and finance

The university is governed by a board of trustees. The board of trustees oversees the long-term development and plans of the university and manages fundraising efforts, and is composed of 55 members including the university president. Directly beneath the president are the provost, fourteen vice presidents (including the chief financial officer,

The university is governed by a board of trustees. The board of trustees oversees the long-term development and plans of the university and manages fundraising efforts, and is composed of 55 members including the university president. Directly beneath the president are the provost, fourteen vice presidents (including the chief financial officer, chief investment officer The chief investment officer (CIO) is a job title for the board level head of investments within an organization. The CIO's purpose is to understand, manage, and monitor their organization's portfolio of assets, devise strategies for growth, act as ...

, and vice president for campus life and student services), the directors of Argonne National Laboratory

Argonne National Laboratory is a science and engineering research United States Department of Energy National Labs, national laboratory operated by University of Chicago, UChicago Argonne LLC for the United States Department of Energy. The facil ...

and Fermilab

Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory (Fermilab), located just outside Batavia, Illinois, near Chicago, is a United States Department of Energy national laboratory specializing in high-energy particle physics. Since 2007, Fermilab has been operat ...

, the secretary of the university, and the student ombudsperson

An ombudsman (, also ,), ombud, ombuds, ombudswoman, ombudsperson or public advocate is an official who is usually appointed by the government or by parliament (usually with a significant degree of independence) to investigate complaints and at ...

. The current chairman of the board of trustees is Joseph Neubauer; in May 2022, the new chairman will be David Rubenstein

David Mark Rubenstein (born August 11, 1949) is an American billionaire businessman. A former government official and lawyer, he is a co-founder and co-chairman of the private equity firm The Carlyle Group,Ka Yee Christina Lee

Ka Yee Christina Lee is a Professor of Chemistry and the Provost at the University of Chicago, where she succeeded Daniel Diermeier on February 1, 2020. She works on membrane biophysics, including protein–lipid interactions, Alzheimer's dise ...

, who stepped in February 2020 after the previous provost, Daniel Diermeier

Daniel Diermeier (born July 16, 1965) is a German-American political scientist and university administrator. He is serving as the ninth Chancellor of Vanderbilt University. Previously, Diermeier was the David Lee Shillinglaw Distinguished Servi ...

, left to become Chancellor of Vanderbilt University

Vanderbilt University (informally Vandy or VU) is a private research university in Nashville, Tennessee. Founded in 1873, it was named in honor of shipping and rail magnate Cornelius Vanderbilt, who provided the school its initial $1-million ...

. The current president of the University of Chicago is chemist Paul Alivisatos, who assumed the role on September 1, 2021. Robert Zimmer

Robert Jeffrey Zimmer (born November 5, 1947) is an American mathematician and academic administrator. From 2006 until 2021, he served as the 13th president of the University of Chicago and as the Chair of the Board for Argonne National Lab, Ferm ...

, the previous president, transitioned into the new role of chancellor of the university.

The university's endowment was the 12th largest among American educational institutions and state university systems in 2013 and was valued at $10 billion. Since 2016, the university's board of trustees has resisted pressure from students and faculty to divest its investments from fossil fuel companies. Part of former university President Zimmer's financial plan for the university was an increase in accumulation of debt to finance large building projects. This drew both support and criticism from many in the university community.

Academics

The academic bodies of the University of Chicago consist of the

The academic bodies of the University of Chicago consist of the College

A college (Latin: ''collegium'') is an educational institution or a constituent part of one. A college may be a degree-awarding tertiary educational institution, a part of a collegiate or federal university, an institution offering ...

, five divisions of graduate research, six professional schools, and the Graham School of Continuing Liberal and Professional Studies

The University of Chicago Graham School of Continuing Liberal and Professional Studies is one of eight professional schools of the University of Chicago. The Graham School's focus is on part-time and flexible programs of study.

The Graham Scho ...

. The university also contains a library system, the University of Chicago Press

The University of Chicago Press is the largest and one of the oldest university presses in the United States. It is operated by the University of Chicago and publishes a wide variety of academic titles, including ''The Chicago Manual of Style'', ...

, and the University of Chicago Medical Center, and oversees several laboratories, including Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory (Fermilab), Argonne National Laboratory

Argonne National Laboratory is a science and engineering research United States Department of Energy National Labs, national laboratory operated by University of Chicago, UChicago Argonne LLC for the United States Department of Energy. The facil ...

, and the Marine Biological Laboratory. The university is accredited by The Higher Learning Commission.

The university runs on a quarter system in which the academic year is divided into four terms: Summer (June–August), Autumn (September–December), Winter (January–March), and Spring (April–June). Full-time undergraduate students take three to four courses every quarter for approximately eleven weeks before their quarterly academic breaks. The school year typically begins in late September and ends in mid-June.

Rankings

The University of Chicago has an extensive record of producing successful business leaders and billionaires. ''ARWU

The ''Academic Ranking of World Universities'' (''ARWU''), also known as the Shanghai Ranking, is one of the annual publications of world university rankings. The league table was originally compiled and issued by Shanghai Jiao Tong University ...

'' has consistently placed the University of Chicago among the top 10 universities in the world, and the 2021 ''QS World University Rankings

''QS World University Rankings'' is an annual publication of university rankings by Quacquarelli Symonds (QS). The QS system comprises three parts: the global overall ranking, the subject rankings (which name the world's top universities for the ...

'' placed the university in 9th place worldwide. The university's law and business

Business is the practice of making one's living or making money by producing or Trade, buying and selling Product (business), products (such as goods and Service (economics), services). It is also "any activity or enterprise entered into for pr ...

schools rank among the top three professional schools in the United States. The business school is currently ranked first in the US by ''US News & World Report'' and first in the world by ''The Economist'', while the law school is ranked third by ''US News & World Report'' and first by ''Above the Law''.

Chicago has also been consistently recognized to be one of the top 15 university brands in the world, retaining the number three spot in the 2019 U.S. News Best Colleges Rankings. In a corporate study carried out by ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'', the university's graduates were shown to be among the most valued in the world.

Undergraduate college

teaching assistant

A teaching assistant or teacher's aide (TA) or education assistant (EA) or team teacher (TT) is an individual who assists a teacher with instructional responsibilities. TAs include ''graduate teaching assistants'' (GTAs), who are graduate school ...

). As of the 2013–2014 school year, 15 courses and demonstrated proficiency in a foreign language are required under the Core. Undergraduate courses at the University of Chicago are known for their demanding standards, heavy workload and academic difficulty; according to '' Uni in the USA'', "Among the academic cream of American universities – Harvard, Yale, Princeton, MIT, and the University of Chicago – it is UChicago that can most convincingly claim to provide the most rigorous, intense learning experience."

Graduate schools and committees

The university graduate schools and committees are divided into five divisions: Biological Sciences, Humanities, Physical Sciences, Social Sciences, and the Pritzker School of Molecular Engineering (PME). In the autumn quarter of 2015, the university enrolled 3,588 graduate students: 438 in the Biological Sciences Division, 801 in the Humanities Division, 1,102 in the Physical Sciences Division, 1,165 in the Social Sciences Division, and 52 in PME. The university is home to several committees for interdisciplinary scholarship, including the John U. Nef Committee on Social Thought.Professional schools

The university contains eight professional schools: theUniversity of Chicago Law School

The University of Chicago Law School is the law school of the University of Chicago, a private research university in Chicago, Illinois. It is consistently ranked among the best and most prestigious law schools in the world, and has many dist ...

, the Pritzker School of Medicine, the Booth School of Business, the University of Chicago Divinity School

The University of Chicago Divinity School is a private graduate institution at the University of Chicago dedicated to the training of academics and clergy across religious boundaries. Formed under Baptist auspices, the school today lacks any s ...

, the University of Chicago Harris School of Public Policy, the University of Chicago School of Social Service Administration

The Crown Family School of Social Work, Policy and Practice, formerly called the School of Social Service Administration (SSA), is the school of social work at the University of Chicago.

History

The school was founded in 1903 by minister and so ...

, the Graham School of Continuing Liberal and Professional Studies

The University of Chicago Graham School of Continuing Liberal and Professional Studies is one of eight professional schools of the University of Chicago. The Graham School's focus is on part-time and flexible programs of study.

The Graham Scho ...

(which offers non-degree courses and certificates as well as degree programs) and the Pritzker School of Molecular Engineering

The Pritzker School of Molecular Engineering (PME) is the first school of engineering at the University of Chicago. It was founded as the Institute for Molecular Engineering in 2011 by the university in partnership with Argonne National Laborator ...

.

The Law School is accredited by the American Bar Association

The American Bar Association (ABA) is a voluntary bar association of lawyers and law students, which is not specific to any jurisdiction in the United States. Founded in 1878, the ABA's most important stated activities are the setting of acad ...

, the Divinity School is accredited by the Commission on Accrediting of the Association of Theological Schools in the United States and Canada, and Pritzker is accredited by the Liaison Committee on Medical Education.

Associated academic institutions

The university runs a number of academic institutions and programs apart from its undergraduate and postgraduate schools. It operates the

The university runs a number of academic institutions and programs apart from its undergraduate and postgraduate schools. It operates the University of Chicago Laboratory Schools

The University of Chicago Laboratory Schools (also known as Lab or Lab Schools and abbreviated as UCLS though the high school is nicknamed U-High) is a Private school, private, co-educational Day school, day Early childhood education, Pre-K and K� ...

(a private day school for K-12

K-1 is a professional kickboxing promotion established in 1993, well known worldwide mainly for its heavyweight division fights and Grand Prix tournaments. In January 2012, K-1 Global Holdings Limited, a company registered in Hong Kong, acquired ...

students and day care

Child care, otherwise known as day care, is the care and supervision of a child or multiple children at a time, whose ages range from two weeks of age to 18 years. Although most parents spend a significant amount of time caring for their child(r ...

), and a public charter school with four campuses on the South Side of Chicago administered by the university's Urban Education Institute. In addition, the Hyde Park Day School, a school for students with learning disabilities, and the Sonia Shankman Orthogenic School

The Sonia Shankman Orthogenic School, also known simply as the Orthogenic School or informally as the O'School, is a residential treatment center a day school, and a therapeutic school for children and adolescents typically classified as emoti ...

, a residential treatment program for those with behavioral and emotional problems, maintains a location on the University of Chicago campus. Since 1983, the University of Chicago has maintained the University of Chicago School Mathematics Project The University of Chicago School Mathematics Project (UCSMP) is a multi-faceted project of the University of Chicago in the United States, intended to improve competency in mathematics in the United States by elevating educational standards for chi ...

, a mathematics program used in urban primary and secondary schools. The university runs a program called the Council on Advanced Studies in the Humanities and Social Sciences, which administers interdisciplinary workshops to provide a forum for graduate students, faculty, and visiting scholars to present scholarly work in progress.

The university also operates the University of Chicago Press

The University of Chicago Press is the largest and one of the oldest university presses in the United States. It is operated by the University of Chicago and publishes a wide variety of academic titles, including ''The Chicago Manual of Style'', ...

, the largest university press in the United States.

Library system

The University of Chicago Library system encompasses six libraries that contain a total of 11 million volumes, the 9th most among library systems in the United States. The university's main library is the Regenstein Library, which contains one of the largest collections of print volumes in the United States. The

The University of Chicago Library system encompasses six libraries that contain a total of 11 million volumes, the 9th most among library systems in the United States. The university's main library is the Regenstein Library, which contains one of the largest collections of print volumes in the United States. The Joe and Rika Mansueto Library

The Joe and Rika Mansueto Library is the newest library of the University of Chicago, named after alumni Joe Mansueto and Rika Mansueto. The library has a capacity of 3.5 million volumes under an elliptical dome. It was designed by Helmut Jahn.

H ...

, built in 2011, houses a large study space and an automated book storage and retrieval system. The John Crerar Library contains more than 1.4 million volumes in the biological, medical and physical sciences and collections in general science and the philosophy and history of science, medicine, and technology. The university also operates a number of special libraries, including the D'Angelo Law Library, the Social Service Administration Library, and the Eckhart Library for mathematics and computer science. Harper Memorial Library is now a reading and study room.

Research

According to the

According to the National Science Foundation

The National Science Foundation (NSF) is an independent agency of the United States government that supports fundamental research and education in all the non-medical fields of science and engineering. Its medical counterpart is the National I ...

, University of Chicago spent $423.9 million on research and development in 2018, ranking it 60th in the nation. It is classified among "R1: Doctoral Universities – Very high research activity" and is a founding member of the Association of American Universities and was a member of the Committee on Institutional Cooperation from 1946 through June 29, 2016, when the group's name was changed to the Big Ten Academic Alliance. The University of Chicago is not a member of the rebranded consortium, but will continue to be a collaborator.

The university operates more than 140 research centers and institutes on campus. Among these are the Oriental Institute—a museum and research center for Near East

The ''Near East''; he, המזרח הקרוב; arc, ܕܢܚܐ ܩܪܒ; fa, خاور نزدیک, Xāvar-e nazdik; tr, Yakın Doğu is a geographical term which roughly encompasses a transcontinental region in Western Asia, that was once the hist ...

ern studies owned and operated by the university—and a number of National Resource Center The National Resource Center (NRC) Program of the U.S. Department of Education provides funding grants to American universities to establish, strengthen, and operate language and area or international studies centers that will be national resources ...

s, including the Center for Middle Eastern Studies. Chicago also operates or is affiliated with several research institutions apart from the university proper. The university manages Argonne National Laboratory

Argonne National Laboratory is a science and engineering research United States Department of Energy National Labs, national laboratory operated by University of Chicago, UChicago Argonne LLC for the United States Department of Energy. The facil ...

, part of the United States Department of Energy

The United States Department of Energy (DOE) is an executive department of the U.S. federal government that oversees U.S. national energy policy and manages the research and development of nuclear power and nuclear weapons in the United Stat ...

's national laboratory system, and co-manages Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory (Fermilab), Sunspot, New Mexico

Sunspot is an unincorporated community in the Sacramento Mountains in the Lincoln National Forest in Otero County, New Mexico, United States, about south of Cloudcroft. Its elevation is . The Sunspot Solar Observatory and Apache Point Observa ...

. Faculty and students at the adjacent Toyota Technological Institute at Chicago

Toyota Technological Institute at Chicago (TTIC or TTI-Chicago) is a private graduate college and research institute focused on computer science and located in Chicago, Illinois within the University of Chicago campus. It is supported by the ear ...

collaborate with the university. In 2013, the university formed an affiliation with the formerly independent Marine Biological Laboratory in Woods Hole, Mass. Although formally unrelated, the National Opinion Research Center is located on Chicago's campus.

The University of Chicago has been the site of some important experiments and academic movements. In economics, the university has played an important role in shaping ideas about the

The University of Chicago has been the site of some important experiments and academic movements. In economics, the university has played an important role in shaping ideas about the free market

In economics, a free market is an economic system in which the prices of goods and services are determined by supply and demand expressed by sellers and buyers. Such markets, as modeled, operate without the intervention of government or any o ...

and is the namesake of the Chicago school of economics

The Chicago school of economics is a neoclassical school of economic thought associated with the work of the faculty at the University of Chicago, some of whom have constructed and popularized its principles. Milton Friedman and George Stigle ...

, the school of economic thought supported by Milton Friedman

Milton Friedman (; July 31, 1912 – November 16, 2006) was an American economist and statistician who received the 1976 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences for his research on consumption analysis, monetary history and theory and the ...

and other economists. The university's sociology

Sociology is a social science that focuses on society, human social behavior, patterns of Interpersonal ties, social relationships, social interaction, and aspects of culture associated with everyday life. It uses various methods of Empirical ...

department was the first independent sociology department in the United States and gave birth to the Chicago school of sociology. In physics, the university was the site of the Chicago Pile-1

Chicago Pile-1 (CP-1) was the world's first artificial nuclear reactor. On 2 December 1942, the first human-made self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction was initiated in CP-1, during an experiment led by Enrico Fermi. The secret development of t ...

(the first controlled, self-sustaining man-made nuclear chain reaction, part of the Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development undertaking during World War II that produced the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States with the support of the United Kingdom and Canada. From 1942 to 1946, the project w ...

), of Robert Millikan

Robert Andrews Millikan (March 22, 1868 – December 19, 1953) was an American experimental physicist honored with the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1923 for the measurement of the elementary electric charge and for his work on the photoelectric e ...

's oil-drop experiment

The oil drop experiment was performed by Robert A. Millikan and Harvey Fletcher in 1909 to measure the elementary electric charge (the charge of the electron). The experiment took place in the Ryerson Physical Laboratory at the University of Chi ...

that calculated the charge of the electron, and of the development of radiocarbon dating

Radiocarbon dating (also referred to as carbon dating or carbon-14 dating) is a method for determining the age of an object containing organic material by using the properties of radiocarbon, a radioactive isotope of carbon.

The method was dev ...

by Willard F. Libby in 1947. The chemical experiment that tested how life originated on early Earth, the Miller–Urey experiment, was conducted at the university. REM sleep

Rapid eye movement sleep (REM sleep or REMS) is a unique phase of sleep in mammals and birds, characterized by random rapid movement of the eyes, accompanied by low muscle tone throughout the body, and the propensity of the sleeper to dream viv ...

was discovered at the university in 1953 by Nathaniel Kleitman

Nathaniel Kleitman (April 26, 1895 – August 13, 1999) was an American physiologist and sleep researcher who served as Professor Emeritus in Physiology at the University of Chicago. He is recognized as the father of modern sleep research, an ...

and Eugene Aserinsky

Eugene Aserinsky (May 6, 1921 – July 22, 1998), a pioneer in sleep research, was a graduate student at the University of Chicago in 1953 when he discovered REM sleep. He was the son of a dentist of Russian–Jewish descent.

He made the disc ...

.

The University of Chicago (Department of Astronomy and Astrophysics) operated the Yerkes Observatory in Williams Bay, Wisconsin from 1897 until 2018, where the largest operating refracting telescope

A refracting telescope (also called a refractor) is a type of optical telescope that uses a lens (optics), lens as its objective (optics), objective to form an image (also referred to a dioptrics, dioptric telescope). The refracting telescope d ...

in the world and other telescopes are located.

Arts

The UChicago Arts program joins academic departments and programs in the Division of the Humanities and the college, as well as professional organizations including the Court Theatre, the Oriental Institute, the

The UChicago Arts program joins academic departments and programs in the Division of the Humanities and the college, as well as professional organizations including the Court Theatre, the Oriental Institute, the Smart Museum of Art

The David and Alfred Smart Museum of Art is an art museum located on the campus of the University of Chicago in Chicago, Illinois. The permanent collection has over 15,000 objects. Admission is free and open to the general public.

The Smart Muse ...

, the Renaissance Society

The Renaissance Society, founded in 1915, is a leading independent contemporary art museum located on the campus of the University of Chicago, with a focus on the commissioning and production of new works by international artists. The kunsthalle- ...

, University of Chicago Presents, and student arts organizations. The university has an artist-in-residence program and scholars in performance studies, contemporary art criticism, and film history. It has offered a doctorate in music composition since 1933 and cinema and media studies since 2000, a master of fine arts in visual arts (early 1970s), and a Master of Arts in the humanities with a creative writing track (2000). It has bachelor's degree programs in visual arts, music, and art history, and, more recently, cinema and media studies (1996) and theater and performance studies (2002). The college's general education core includes a "dramatic, musical, and visual arts" requirement, inviting students to study the history of the arts, stage desire, or begin working with sculpture. Several thousand major and non-major undergraduates enroll annually in creative and performing arts classes. UChicago is often considered the birthplace of improvisational comedy as the Compass Players student comedy troupe evolved into The Second City

The Second City is an improvisational comedy enterprise and is the oldest ongoing improvisational theater troupe to be continually based in Chicago, with training programs and live theatres in Toronto and Los Angeles. The Second City Theatre op ...

improv theater troupe in 1959. The Reva and David Logan Center for the Arts opened in October 2012, five years after a $35 million gift from alumnus David Logan and his wife Reva. The center includes spaces for exhibitions, performances, classes, and media production. The Logan Center was designed by Tod Williams and Billie Tsien.

Student body and admissions

Admissions

In Fall 2021, the university enrolled 7,559 undergraduate students, 10,893 graduate students, and 449 non-degree students. The college class of 2025 is composed of 53% male students and 47% female students. Twenty-seven percent of the class identify as Asian, 19% as Hispanic, and 10% as Black. Eighteen percent of the class is international. Admissions to the University of Chicago has become highly selective over the past two decades, reflecting changes in the application process, school popularity, and marketing strategy. Between 1996 and 2022, the acceptance rate of the college fell from 71% to 4.9%. For the Class of 2026, the acceptance rate was 5.4%. The middle 50% band ofSAT

The SAT ( ) is a standardized test widely used for college admissions in the United States. Since its debut in 1926, its name and scoring have changed several times; originally called the Scholastic Aptitude Test, it was later called the Schola ...