U.S. Army Air on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

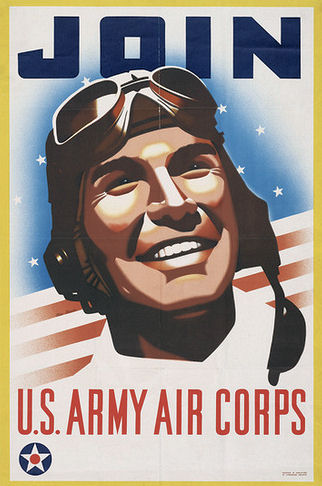

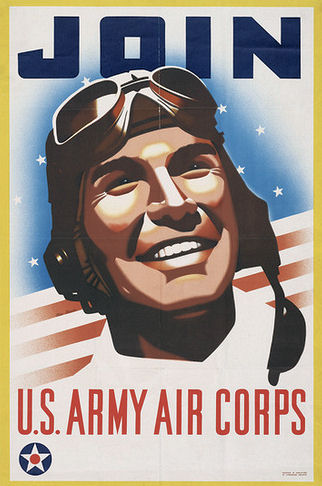

The United States Army Air Corps (USAAC) was the

The United States Army Air Corps (USAAC) was the

The Air Corps Act (44 ''Stat.'' 780) became law on 2 July 1926. In accordance with the Morrow Board's recommendations, the act created an additional

The Air Corps Act (44 ''Stat.'' 780) became law on 2 July 1926. In accordance with the Morrow Board's recommendations, the act created an additional

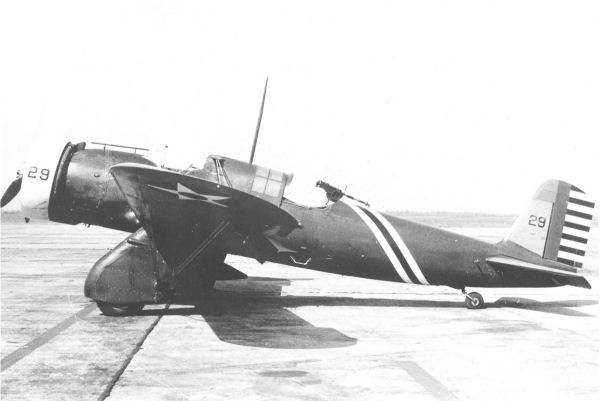

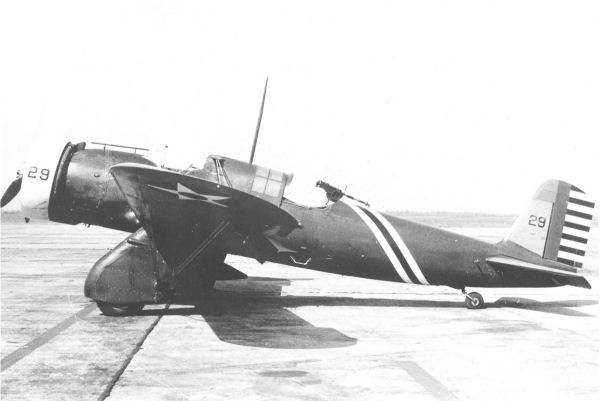

The Air Corps adopted a new color scheme for painting its aircraft in 1927, heretofore painted

The Air Corps adopted a new color scheme for painting its aircraft in 1927, heretofore painted

Most pursuit fighters before 1935 were of the

Most pursuit fighters before 1935 were of the

New bomber types under development clearly outperformed new pursuit types, particularly in speed and altitude, then considered the primary defenses against interception. In both 1932 and 1933, large-scale maneuvers found fighters unable to climb to altitude quickly enough to intercept attacking B-9 and B-10 prototypes, a failure so complete that Westover, following the 1933 maneuvers, actually proposed elimination of pursuits altogether.

1933 was a pivotal year in the advancement of aviation technology in which the all-metal airplane came of age, "practically overnight" in the words of one historian, because of the availability of the first practical

New bomber types under development clearly outperformed new pursuit types, particularly in speed and altitude, then considered the primary defenses against interception. In both 1932 and 1933, large-scale maneuvers found fighters unable to climb to altitude quickly enough to intercept attacking B-9 and B-10 prototypes, a failure so complete that Westover, following the 1933 maneuvers, actually proposed elimination of pursuits altogether.

1933 was a pivotal year in the advancement of aviation technology in which the all-metal airplane came of age, "practically overnight" in the words of one historian, because of the availability of the first practical

In January 1936, the Air Corps contracted with

In January 1936, the Air Corps contracted with

As a further consequence of the Air Mail scandal, the Baker Board reviewed the performance of Air Corps aircraft and recognized that civilian aircraft were far superior to planes developed solely to Air Corps specifications. Following up on its recommendation, the Air Corps purchased and tested a

As a further consequence of the Air Mail scandal, the Baker Board reviewed the performance of Air Corps aircraft and recognized that civilian aircraft were far superior to planes developed solely to Air Corps specifications. Following up on its recommendation, the Air Corps purchased and tested a

"Our Still-Flying Fortress."

''Popular Mechanics,'' Volume 162, Issue 1, January 1985, p. 124.A shortage of critical materials and insufficient skilled labor delayed production, which did not begin until April 1941. The first deliveries of the B-17E to the AAF began in November 1941, five months later than scheduled. Its successor, the B-17F, followed less than six months later however and was the primary AAF bomber in its first year of combat operations. In June 1939 the Kilner BoardThe Kilner Board, appointed by Arnold, was chaired by Assistant Chief of the Air Corps Brig. Gen. Walter G. "Mike" Kilner, a veteran pursuit pilot and proponent of an independent Air Force. recommended several types of bombers needed to fulfill the Air Corps mission that included aircraft having tactical radii of both 2,000 and 3,000 miles (revised in 1940 to 4,000). Chief of Staff Craig, long an impediment to Air Corps ambitions but nearing retirement, came around to the Air Corps viewpoint after Roosevelt's views became public. Likewise, the War Department General Staff reversed itself and concurred in the requirements, ending the brief moratorium on bomber development and paving the way for work on the B-29. Over the winter of 1938–1939, Arnold transferred a group of experienced officers headed by Lt. Col.

Executive Order 9082

which changed Arnold's title to ''Commanding General, Army Air Forces'' effective 9 March 1942, making him co-equal with the commanding generals of the other components of the

; 1st Wing

(Brig. Gen.

; 1st Wing

(Brig. Gen.  ; 2nd Wing

(Brig. Gen. H. Conger Pratt,

; 2nd Wing

(Brig. Gen. H. Conger Pratt,  ;

;

*

* *

* * The Air Corps became a subordinate component of the Army Air Forces on 20 June 1941, and was abolished as an administrative organization on 9 March 1942. It continued to exist as one of the combat arms of the Army (along with Infantry, Cavalry, Artillery, Corps of Engineers, and Signal Corps) until abolished by reorganization provisions of the National Security Act of 1947 (61 ''Stat''. 495), 26 July 1947.

Tables 1–73, Combat Groups, Personnel, Training, and Crews

*Bowman, Martin W. (1997). ''USAAF Handbook 1939–1945'', *Coffey, Thomas M. (1982). ''Hap: The Story of the U.S. Air Force and the Man Who Built It, General Henry H. "Hap" Arnold'', The Viking Press, *Cate, James L. (1945). ''The History of the Twentieth Air Force: Genesis'' (USAF Historical Study 112). AFHRA *Cline, Ray S. (1990)

. ''United States Army in World War II: The War Department'' (series),

''Volume One – Plans and Early Operations: January 1939 – August 1942''

:(1949)

''Volume Two – Europe: Torch to Pointblank: August 1942 – December 1943''

:(1951)

''Volume Three – Europe: Argument to V-E Day: January 1944 – May 1945''

:(1950)

''Volume Four – The Pacific: Guadalcanal to Saipan: August 1942 – July 1944''

:(1953)

''Volume Five – The Pacific: Matterhorn to Nagasaki: June 1944-August1945''

:(1955)

''Volume Six – Men and Planes''

:(1958)

''Volume Seven – Services Around the World''

*Eden, Paul and Soph Moeng, eds (2002). ''The Complete Encyclopedia of World Aircraft''. London: Amber Books Ltd. . *Foulois, Benjamin D. Glines, Carroll V. (1968). ''From the Wright Brothers to the Astronauts: The Memoirs of Major General Benjamin D. Foulois''. New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company. * * *Greenfield, Col. Kent Roberts (1948). Study No. 35 ''Army Ground Forces and the Air-Ground Battle Team''. Historical Section Army Ground Forces, AD-A954 913 * * *Maurer, Maurer (1987). ''Aviation in the U.S. Army, 1919–1939'', Office of Air Force History, Washington, D.C. *Maurer, Maurer (1961).

Air Force Combat Units of World War II

', Office of Air Force History. * * * * *Rice, Rondall Ravon (2004). ''The Politics of Air Power: From Confrontation to Cooperation in Army Aviation Civil-Military Relations'', University of Nebraska Press. * * *Smith, Richard K. (1998)

''Seventy-Five Years of Inflight Refueling: Highlights 1923-1998''

Air Force History and Museums, Air University, Maxwell AFB * *White, Jerry (1949)

''Combat Crew and Training Units in the AAF, 1939–45''

(USAF Historical Study 61). Air Force Historical Research Agency. *Williams, Edwin L., Jr. (1953). ''Legislative History of the AAF and USAF, 1941–1951'' (USAF Historical Study No. 84). Air Force Historical Research Agency ;Websites

2006 Almanac, ''Air Force Magazine: Journal of the Air Force Association'', May 2006, Volume 89 Number 5Texas Military Veteran Video Oral Histories – Newton Gresham Library, Sam Houston State University

Many of the veterans included in this collections served in the United States Army Air Corps and share their experiences. {{US Air Force navbox 1926 establishments in the United States Collier Trophy recipients Disbanded air forces

The United States Army Air Corps (USAAC) was the

The United States Army Air Corps (USAAC) was the aerial warfare

Aerial warfare is the use of military aircraft and other flying machines in warfare. Aerial warfare includes bombers attacking enemy installations or a concentration of enemy troops or strategic targets; fighter aircraft battling for control o ...

service component of the United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, cla ...

between 1926 and 1941. After World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, as early aviation became an increasingly important part of modern warfare, a philosophical rift developed between more traditional ground-based army personnel and those who felt that aircraft were being underutilized and that air operations were being stifled for political reasons unrelated to their effectiveness. The USAAC was renamed from the earlier United States Army Air Service

The United States Army Air Service (USAAS)Craven and Cate Vol. 1, p. 9 (also known as the ''"Air Service"'', ''"U.S. Air Service"'' and before its legislative establishment in 1920, the ''"Air Service, United States Army"'') was the aerial war ...

on 2 July 1926, and was part of the larger United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, cla ...

. The Air Corps became the United States Army Air Forces

The United States Army Air Forces (USAAF or AAF) was the major land-based aerial warfare service component of the United States Army and ''de facto'' aerial warfare service branch of the United States during and immediately after World War II ...

(USAAF) on 20 June 1941, giving it greater autonomy from the Army's middle-level command structure. During World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, although not an administrative echelon, the Air Corps (AC) remained as one of the combat arms

Combat arms (or fighting arms in non-American parlance) are troops within national armed forces who participate in direct tactical ground combat. In general, they are units that carry or employ weapons, such as infantry, cavalry, and artillery uni ...

of the Army until 1947, when it was legally abolished by legislation establishing the Department of the Air Force

The United States Department of the Air Force (DAF) is one of the three military departments within the Department of Defense of the United States of America. The Department of the Air Force was formed on September 18, 1947, per the National Sec ...

.

The Air Corps was renamed by the United States Congress

The United States Congress is the legislature of the federal government of the United States. It is bicameral, composed of a lower body, the House of Representatives, and an upper body, the Senate. It meets in the U.S. Capitol in Washing ...

largely as a compromise between the advocates of a separate air arm and those of the traditionalist Army high command who viewed the aviation arm as an auxiliary branch to support the ground forces. Although its members worked to promote the concept of air power and an autonomous air force in the years

''The Years'' is a 1937 novel by Virginia Woolf, the last she published in her lifetime. It traces the history of the Pargiter family from the 1880s to the "present day" of the mid-1930s.

Although spanning fifty years, the novel is not epic i ...

between the world war

A world war is an international conflict which involves all or most of the world's major powers. Conventionally, the term is reserved for two major international conflicts that occurred during the first half of the 20th century, World WarI (1914 ...

s, its primary purpose by Army policy remained support of ground forces rather than independent operations.

On 1 March 1935, still struggling with the issue of a separate air arm, the Army activated the General Headquarters Air Force for centralized control of aviation combat units within the continental United States, separate from but coordinate with the Air Corps. The separation of the Air Corps from control of its combat units caused problems of unity of command that became more acute as the Air Corps enlarged in preparation for World War II. This was resolved by the creation of the Army Air Forces (AAF), making both organizations subordinate to the new higher echelon.

On 20 June 1941, the Army Air Corps' existence as the primary air arm of the U.S. Army changed to that of solely being the training and logistics elements of the then-new United States Army Air Forces

The United States Army Air Forces (USAAF or AAF) was the major land-based aerial warfare service component of the United States Army and ''de facto'' aerial warfare service branch of the United States during and immediately after World War II ...

, which embraced the formerly-named General Headquarters Air Force under the new Air Force Combat Command organization for front-line combat operations; this new element, along with the Air Corps, comprised the USAAF.

The Air Corps ceased to have an administrative structure after 9 March 1942, but as "the permanent statutory organization of the air arm, and the principal component of the Army Air Forces," the overwhelming majority of personnel assigned to the AAF were members of the Air Corps.Craven and Cate, Vol. 6, p. 31.

Creation of the Air Corps

TheU.S. Army Air Service

The United States Army Air Service (USAAS)Craven and Cate Vol. 1, p. 9 (also known as the ''"Air Service"'', ''"U.S. Air Service"'' and before its legislative establishment in 1920, the ''"Air Service, United States Army"'') was the aerial warf ...

had a brief but turbulent history. Created during World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

by executive order

In the United States, an executive order is a directive by the president of the United States that manages operations of the federal government. The legal or constitutional basis for executive orders has multiple sources. Article Two of th ...

of President Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was an American politician and academic who served as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. A member of the Democratic Party, Wilson served as the president of ...

after America entered the war in April 1917 as the increasing use of airplanes and the military uses of aviation were readily apparent as the war continued to its climax, the U.S. Army Air Service

The United States Army Air Service (USAAS)Craven and Cate Vol. 1, p. 9 (also known as the ''"Air Service"'', ''"U.S. Air Service"'' and before its legislative establishment in 1920, the ''"Air Service, United States Army"'') was the aerial warf ...

gained permanent legislative authority in 1920 as a combatant arm of the line of the United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, cla ...

. There followed a six-year struggle between adherents of airpower and the supporters of the traditional military services about the value of an independent Air Force, intensified by struggles for funds caused by skimpy budgets, as much an impetus for independence as any other factor.

The Lassiter Board, a group of General Staff

A military staff or general staff (also referred to as army staff, navy staff, or air staff within the individual services) is a group of officers, enlisted and civilian staff who serve the commander of a division or other large military un ...

officers, recommended in 1923 that the Air Service be augmented by an offensive force of bombardment and pursuit units under the command of Army general headquarters in time of war, and many of its recommendations became Army regulations. The War Department desired to implement the Lassiter Board's recommendations, but the administration of President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

*President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ful ...

Calvin Coolidge

Calvin Coolidge (born John Calvin Coolidge Jr.; ; July 4, 1872January 5, 1933) was the 30th president of the United States from 1923 to 1929. Born in Vermont, Coolidge was a History of the Republican Party (United States), Republican lawyer ...

chose instead to economize by radically cutting military budgets, particularly the Army's.The Coolidge administration boasted of cutting the War Department's budget by 75%. The Lampert Committee of the House of Representatives

House of Representatives is the name of legislative bodies in many countries and sub-national entitles. In many countries, the House of Representatives is the lower house of a bicameral legislature, with the corresponding upper house often c ...

in December 1925 proposed a unified air force independent of the Army and Navy, plus a department of defense to coordinate the three armed services. However another board, headed by Dwight Morrow

Dwight Whitney Morrow (January 11, 1873October 5, 1931) was an American businessman, diplomat, and politician, best known as the U.S. ambassador who improved U.S.-Mexican relations, mediating the religious conflict in Mexico known as the Cristero ...

, was appointed in September 1925 by Coolidge ostensibly to study the "best means of developing and applying aircraft in national defense" but in reality to minimize the political impact of the pending court-martial of Billy Mitchell

William Lendrum Mitchell (December 29, 1879 – February 19, 1936) was a United States Army officer who is regarded as the father of the United States Air Force.

Mitchell served in France during World War I and, by the conflict's end, command ...

(and to preempt the findings of the Lampert Committee). It declared that no threat of air attack was likely to exist to the United States, rejected the idea of a department of defense and a separate department of air, and recommended minor reforms that included renaming the air service to allow it "more prestige."

In early 1926 the Military Affairs Committee of the Congress rejected all bills set forth before it on both sides of the issue. They fashioned a compromise in which the findings of the Morrow Board were enacted as law, while providing the air arm a "five-year plan" for expansion and development. Maj. Gen. Mason Patrick

Mason Mathews Patrick (December 13, 1863 – January 29, 1942) was a general officer in the United States Army who led the United States Army Air Service during and after World War I and became the first Chief of the Army Air Corps when it was c ...

, the Chief of Air Service, had proposed that it be made a semi-independent service within the War Department along the lines of the Marine Corps within the Navy Department, but this was rejected; only the cosmetic name change was accepted.Gen. Patrick's proposal of an Air Corps equivalent to the Marine Corps was characterized by Brig. Gen. Fox Conner

Fox Conner (November 2, 1874 – October 13, 1951) was a major general of the United States Army. He served as operations officer for the American Expeditionary Force during World War I, and is best remembered as a mentor to the generation of off ...

(and not for the first nor last time by General Staff opponents of Air Corps independence) as a "promotion scheme". The legislation changed the name of the Air Service to the Air Corps, (in the words of one analyst) "thereby strengthening the conception of military aviation as an offensive, striking arm rather than an auxiliary service."

The Air Corps Act (44 ''Stat.'' 780) became law on 2 July 1926. In accordance with the Morrow Board's recommendations, the act created an additional

The Air Corps Act (44 ''Stat.'' 780) became law on 2 July 1926. In accordance with the Morrow Board's recommendations, the act created an additional Assistant Secretary of War

The United States Assistant Secretary of War was the second–ranking official within the American Department of War from 1861 to 1867, from 1882 to 1883, and from 1890 to 1940. According to thMilitary Laws of the United States "The act of August ...

to "help foster military aeronautics", and established an air section in each division of the General Staff for a period of three years. Two additional brigadier generals would serve as assistant chiefs of the Air Corps.All Air Corps generals held temporary ranks. The Air Corps did not have a member promoted to permanent establishment general officer until 1937, and he was promptly removed from the Air Corps. Previous provisions of the National Defense Act of 1920 that all flying units be commanded only by rated personnel and that flight pay be awarded were continued. The Air Corps also retained the "Prop and Wings

A prop, formally known as (theatrical) property, is an object used on stage or screen by actors during a performance or screen production. In practical terms, a prop is considered to be anything movable or portable on a stage or a set, distinc ...

" as its branch insignia through its disestablishment in 1947. Patrick became Chief of the Air Corps and Brig. Gen. James E. Fechet

James Edmond Fechet (August 21, 1877 – February 10, 1948) was a major general in the United States Army and the Chief of Air Corps 1927–1931. Men he had selected and worked with both on his staff and in other top Air Corps positions became k ...

continued as his first assistant chief. On 17 July 1926, two lieutenant colonels were promoted to brigadier general

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointed ...

for four-year terms as assistant chiefs of Air Corps: Frank P. Lahm

Frank Purdy Lahm (November 17, 1877 – July 7, 1963) was an American aviation pioneer, the "nation's first military aviator", and a general officer in the United States Army Air Corps and Army Air Forces.

Lahm developed an interest in flying f ...

, to command the new Air Corps Training Center

The atmosphere of Earth is the layer of gases, known collectively as air, retained by Earth's gravity that surrounds the planet and forms its planetary atmosphere. The atmosphere of Earth protects life on Earth by creating pressure allowing for ...

, and William E. Gillmore, in command of the Materiel Division

Air Materiel Command (AMC) was a United States Army Air Forces and United States Air Force command. Its headquarters was located at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, Ohio. In 1961, the command was redesignated the Air Force Logistics Command wi ...

.Gillmore had been chief of the Supply Division of the Air Service. Both he and Lahm served a single tour. Of the three assistant chiefs, Fechet succeeded Patrick in December 1927, Gillmore retired on 30 June 1930, and Lahm reverted to his permanent rank on 16 July 1930.

Of the new law and organization, however, Wesley F. Craven and James L. Cate in the official history of the United States Army Air Forces

The United States Army Air Forces (USAAF or AAF) was the major land-based aerial warfare service component of the United States Army and ''de facto'' aerial warfare service branch of the United States during and immediately after World War II ...

concluded that:

"The bill which was finally enacted purported to be a compromise, but it leaned heavily on the Morrow recommendations. The Air Corps Act of 2 July 1926 effected no fundamental innovation. The change in designation meant no change in status: the Air Corps was still a combatant branch of the Army with less prestige than the Infantry."Craven and Cate Vol. 1, p. 29.The position of the air arm within the Department of War remained essentially the same as before, that is, the flying units were under the operational control of the various ground forces

corps area

A Corps area was a geographically-based organizational structure (military district) of the United States Army used to accomplish administrative, training and tactical tasks from 1920 to 1942. Each corps area included divisions of the Regular Army ...

commands and not the Air Corps, which remained responsible for procurement and maintenance of aircraft, supply, and training. Because of a lack of legally specified duties and responsibilities, the new position of Assistant Secretary of War for Air

Assistant may refer to:

* Assistant (by Speaktoit), a virtual assistant app for smartphones

* Assistant (software), a software tool to assist in computer configuration

* Google Assistant, a virtual assistant by Google

* ''The Assistant'' (TV seri ...

, held by F. Trubee Davison

Frederick Trubee Davison (February 7, 1896 – November 14, 1974) was an American World War I aviator, assistant United States Secretary of War, director of personnel for the Central Intelligence Agency, and president of the American Museum o ...

from July 1926 to March 1933, proved of little help in promoting autonomy for the air arm.

Five-year expansion program

The Air Corps Act gave authorization to carry out a five-year expansion program. However, a lack of appropriations caused the beginning of the program to be delayed until 1 July 1927. Patrick proposed an increase to 63 tactical squadrons (from an existing 32) to maintain the program of the Lassiter Board already in effect, but Chief of Staff Gen. John Hines rejected the recommendation in favor of a plan drawn up by ground force Brig. Gen.Hugh Drum

Hugh Aloysius Drum (September 19, 1879 – October 3, 1951) was a career United States Army officer who served in World War I and World War II and attained the rank of lieutenant general. He was notable for his service as chief of staff of the F ...

that proposed 52 squadrons.The General Staff viewed the "five-year plan" as an opponent of the Army in general and fought it bitterly, citing it as a destructive force at every opportunity. General Drum also chaired the 1933 Drum Board, created specifically to oppose (and revise) plans and appropriation requests submitted by Chief of Air Corps Foulois that were not to the General Staff's liking. The act authorized expansion to 1,800 airplanes, 1,650 officers, and 15,000 enlisted men, to be reached in regular increments over a five-year period. None of the goals was reached by July 1932. Neither of the relatively modest increases in airplanes or officers was accomplished until 1938 because adequate funds were never appropriated and the coming of the Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

forced reductions in pay and modernization across the board in the Army. Organizationally the Air Corps doubled from seven to fifteen groups

A group is a number of persons or things that are located, gathered, or classed together.

Groups of people

* Cultural group, a group whose members share the same cultural identity

* Ethnic group, a group whose members share the same ethnic iden ...

, but the expansion was meaningless because all were seriously understrength in aircraft and pilots. ( Origin of first seven groups shown here)

As units of the Air Corps increased in number, so did higher command echelons. The '' 2nd Wing'', activated in 1922 as part of the Air Service, remained the only wing organization in the new Air Corps until 1929, when it was redesignated the ''2nd Bombardment Wing'' in anticipation of the activation of the ''1st Bombardment Wing

The 1st Bombardment Wing is a disbanded United States Army Air Force unit. It was initially formed in France in 1918 during World War I as a command and control organization for the Pursuit Groups of the First Army Air Service.

Demobilized after ...

'' to provide a bombardment wing on each coast. The 1st Bomb Wing was activated in 1931, followed by the ''3rd Attack Wing

The 98th Bombardment Wing is an inactive United States Army Air Forces unit. Its last assignment was with the United States Air Force Reserve, based at Bedford Field, Massachusetts. It was inactivated on 27 June 1949.

History

As the 3d Wing, ...

'' in 1932 to protect the Mexican border, at which time the 1st became the ''1st Pursuit Wing''. The three wings became the foundation of General Headquarters Air Force upon its activation in 1935.

Aircraft and personnel 1926–1935

The Air Corps adopted a new color scheme for painting its aircraft in 1927, heretofore painted

The Air Corps adopted a new color scheme for painting its aircraft in 1927, heretofore painted olive drab

Olive is a dark yellowish-green color, like that of unripe or green olives.

As a color word in the English language, it appears in late Middle English. Shaded toward gray, it becomes olive drab.

Variations

Olivine

Olivine is the typical ...

. The wings and tails of aircraft were painted chrome yellow

__NOTOC__

Chrome yellow is a yellow pigment in paints using monoclinic lead(II) chromate (PbCrO4). It occurs naturally as the mineral crocoite but the mineral ore itself was never used as a pigment for paint. After the French chemist Louis Vau ...

, with the words "U.S. ARMY" displayed in large black lettering on the undersurface of the lower wings. Tail rudders were painted with a vertical dark blue band at the rudder hinge and 13 alternating red-and-white horizontal stripes trailing. The painting of fuselages olive drab was changed to blue in the early 1930s, and this motif continued until late 1937, when all new aircraft (now all-metal) were left unpainted except for national markings.

Most pursuit fighters before 1935 were of the

Most pursuit fighters before 1935 were of the Curtiss P-1 Hawk

The P-1 Hawk (Curtiss Model 34) was a 1920s open-cockpit biplane fighter aircraft of the United States Army Air Corps. An earlier variant of the same aircraft had been designated PW-8 prior to 1925."US Military Aircraft Designations & Serials 19 ...

(1926–1930) and Boeing P-12

The Boeing P-12/F4B was an American pursuit aircraft that was operated by the United States Army Air Corps , United States Marine Corps, and United States Navy.

Design and development

Developed as a private venture to replace the Boeing F2B an ...

(1929–1935) families, and before the 1934 introduction of the all-metal monoplane, most front-line bombers were canvas-and-wood variants of the radial engine

The radial engine is a reciprocating type internal combustion engine configuration in which the cylinders "radiate" outward from a central crankcase like the spokes of a wheel. It resembles a stylized star when viewed from the front, and is ca ...

d Keystone LB-6

The Keystone LB-6 and LB-7 were 1920s American light bombers, built by the Keystone Aircraft company for the United States Army Air Corps, called Panther by the company, but adoption of the name was rejected by the U.S. Army.

Design & developme ...

(60 LB-5A, LB-6 and LB-7 bombers) and B-3A (127 B-3A, B-4A, B-5, and B-6A bombers) designs.The primary difference between the types is the twin-finned tail of the former, and the single vertical stabilizer of the latter design, which gave it marginally superior performance. Between 1927 and 1934, the Curtiss O-1 Falcon

The Curtiss Falcon was a family of military biplane aircraft built by the American aircraft manufacturer Curtiss Aeroplane and Motor Company during the 1920s. Most saw service as part of the United States Army Air Corps as observation aircraf ...

was the most numerous of the 19 different types and series of observation craft and its A-3 variant the most numerous of the attack planes that fulfilled the observation/close support role designated by the General Staff as the primary mission of the Air Corps.

Transport aircraft used during the first ten years of the Air Corps were of largely trimotor

A trimotor is an aircraft powered by three engines and represents a compromise between complexity and safety and was often a result of the limited power of the engines available to the designer. Many trimotors were designed and built in the 1920s ...

design, such as the Atlantic-Fokker C-2 and the Ford C-3, and were procured in such small numbers (66 total) that they were doled out one airplane to a base. As their numbers and utility declined, they were replaced by a series of 50 twin-engine and single-engine small transports and used for staff duties. Pilot training was conducted between 1927 and 1937 in the Consolidated PT-3

The Consolidated Model 2 was a training airplane used by the United States Army Air Corps, under the designation PT-3 and the United States Navy under the designation NY-1.

Development

Seeing the success of the Navy's NY-1 modification of a ...

trainer, followed by the Stearman PT-13 and variants after 1937.

By 1933 the Air Corps expanded to a tactical strength of 50 squadrons: 21 pursuit, 13 observation, 12 bombardment, and 4 attack. All were understrength in aircraft and men, particularly officers, which resulted in most being commanded by junior officers (commonly first lieutenants)An example is Ralph F. Stearley, who commanded the 13th Attack Squadron for four years as a 1st Lieutenant. instead of by majors as authorized. The last open-cockpit fighter used by the Air Corps, the Boeing P-26 Peashooter

The Boeing P-26 "Peashooter" was the first American production all-metal fighter aircraft and the first pursuit monoplane to enter squadron service with the United States Army Air Corps. Designed and built by Boeing, the prototype first flew in ...

, came into service in 1933 and bridged the gap between the biplane and more modern fighters.

The Air Corps was called upon in early 1934 to deliver mail in the wake of the Air Mail scandal

The Air Mail scandal, also known as the Air Mail fiasco, is the name that the American press gave to the political scandal resulting from a 1934 congressional investigation of the awarding of contracts to certain airlines to carry airmail and t ...

, involving the postmaster general

A Postmaster General, in Anglosphere countries, is the chief executive officer of the postal service of that country, a ministerial office responsible for overseeing all other postmasters. The practice of having a government official respons ...

and heads of the airlines. Despite an embarrassing performance that resulted from numerous crashes and 13 fatalities and was deemed a "fiasco" in the media, investigating boards in 1933–1934The Drum Board was a panel of five generals formed in August 1933 by the General Staff to oppose recommendations by Air Corps planners for development and expansion to meet defense needs (Tate (1998) pp. 138–139), while the Baker Board was formed after the Air Mail scandal and had as its military members (who controlled the agenda) the five generals of the Drum Board (Tate pp. 143–145). recommended organizational and modernization changes that again set the Air Corps on the path to autonomy and eventual separation from the Army. A force of 2,320 aircraft was recommended by the Drum Board,The Drum Board derived its figure as the number necessary to maintain 2,072 "serviceable" planes for its worst-case scenario, War Plan Red-Orange. War plans involving Great Britain ("Red") as an opponent were not officially excluded from United States war planning until January 1938. and authorized by Congress in June 1936, but appropriations to build up the force were denied by the administration until 1939, when the probability of war became apparent. Instead, the Air Corps inventory actually declined to 855 total aircraft in 1936, a year after the creation of GHQ Air Force, which by itself was recommended to have a strength of 980.

The most serious fallout from the Air Mail fiasco was the retirement under fire of Major General Benjamin Foulois

Benjamin Delahauf Foulois (December 9, 1879 – April 25, 1967) was a United States Army general who learned to fly the first military planes purchased from the Wright brothers. He became the first military aviator as an airship pilot, and achi ...

as Chief of Air Corps. Soon after the Roosevelt administration placed the blame on him for the Air Corps' failures, he was investigated by a congressional subcommittee alleging corruption in aircraft procurement. The matter resulted in an impasse between committee chairman William N. Rogers

William Nathaniel Rogers (January 10, 1892 – September 25, 1945) was a U.S. Representative from New Hampshire.

Born in Sanbornville, New Hampshire, Rogers attended the public schools, Brewster Free Academy in Wolfeboro, and Dartmouth Colleg ...

and Secretary of War George Dern

George Henry Dern (1872–1936) was an American politician, mining man, and businessman. He co-invented the Holt–Dern ore roasting process and was United States Secretary of War from 1933 to his death in 1936. He also served as the sixth Gov ...

before being sent to the Army's Inspector General, who ruled largely in favor of Foulois. Rogers continued to severely criticize Foulois through the summer of 1935, threatening future Air Corps appropriations, and despite public support by Dern for the embattled chief, the administration was close to firing Foulois for his perceived attitude as a radical airman and his public criticisms of the administration during the controversy. He retired in December 1935 for the good of the service.Rice (2004), p. 133

The Roosevelt administration began a search for his replacement in September 1935, narrowing the choice to two of the three assistant chiefs, Henry Conger Pratt

Henry Conger Pratt (September 2, 1882 – April 6, 1966), professionally known as H. Conger Pratt, was a major general in the United States Army. He was awarded a Distinguished Service Medal with one oak leaf cluster, and received awards from I ...

and Oscar Westover

Oscar M. Westover (July 23, 1883 – September 21, 1938) was a major general and fourth chief of the United States Army Air Corps.

Early life and career

Westover was born in Bay City, Michigan, and enlisted in the United States Army when he was ...

. Pratt appeared to have the superior credentials, but he had been in charge of aircraft procurement during the Foulois years and was looked upon warily by Dern as possibly being another Mitchell or Foulois. Westover was chosen because he was the philosophical opposite of the two insurgent airmen in all respects, being a "team player".

The open insurgency between 1920 and 1935 of airmen foreseeing a need for an independent air force in order to develop fully the potential of airpower had cost the careers of two of its near-legendary lights, Foulois and Mitchell, and nearly cost the reputation of two others, Pratt and Henry H. Arnold

Henry Harley Arnold (June 25, 1886 – January 15, 1950) was an American general officer holding the ranks of General of the Army and later, General of the Air Force. Arnold was an aviation pioneer, Chief of the Air Corps (1938–1941), ...

. In terms of the principle of civilian control of the military in peacetime, their tactics and behavior were clearly inappropriate. The political struggle had temporarily alienated supporters in Congress, had been counterproductive of the development of the Air Corps in the short run, and had hardened the opposition of an already antagonistic General Staff. But through their mistakes and repeated rebuffs, the airmen had learned what they were lacking: proof for the argument that the Air Corps could perform a unique mission—strategic bombardment—and the real threat of another world war would soon reverse their fortunes.Rice (2004), p. 1237

Doctrinal development

Strategic bombardment in roles and missions

In March 1928, commenting on the lack of survivability in combat of his unit's Keystone LB-7 andMartin NBS-1

The Martin NBS-1 was a military aircraft of the United States Army Air Service and its successor, the Army Air Corps. An improved version of the Martin MB-1, a scout-bomber built during the final months of World War I, the NBS-1 was ordered ...

bombers, Lt. Col. Hugh J. Knerr

Hugh Johnston Knerr (May 30, 1887 – October 26, 1971) was a major general in the United States Air Force.

Biography

Knerr was born on May 30, 1887, in Fairfield, Iowa. He died on October 26, 1971, and is buried at Arlington National Cemeter ...

, commander of the 2nd Bombardment Group

The 2d Operations Group (2 OG) is the flying component of the United States Air Force 2d Bomb Wing, assigned to the Air Force Global Strike Command Eighth Air Force. The group is stationed at Barksdale Air Force Base, Louisiana.

2 OG is one of t ...

at Langley Field Langley may refer to:

People

* Langley (surname), a common English surname, including a list of notable people with the name

* Dawn Langley Simmons (1922–2000), English author and biographer

* Elizabeth Langley (born 1933), Canadian perform ...

, Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

, recommended that the Air Corps adopt two types of all-metal monoplane bombers, a short-range day bomber and a long-range night bomber. Instructors at the Air Corps Tactical School

The Air Corps Tactical School, also known as ACTS and "the Tactical School", was a military professional development school for officers of the United States Army Air Service and United States Army Air Corps, the first such school in the world. C ...

(ACTS), also then at Langley, took the concept one step further in March 1930 by recommending that the types instead be ''light'' and ''heavy'', the latter capable of long range carrying a heavy bomb load that could also be used during daylight.

The Air Corps in January 1931 "got its foot in the door" for developing a mission for which only it would have capability, while at the same time creating a need for technological advancement of its equipment. Chief of Naval Operations

The chief of naval operations (CNO) is the professional head of the United States Navy. The position is a statutory office () held by an admiral who is a military adviser and deputy to the secretary of the Navy. In a separate capacity as a memb ...

Admiral William V. Pratt

William Veazie Pratt (28 February 1869 – 25 November 1957) was an admiral in the United States Navy. He served as the President of the Naval War College from 1925 to 1927, and as the 5th Chief of Naval Operations from 1930 to 1933.

Early l ...

wanted approval of his proposition that all naval aviation including land-based aircraft was by definition tied to carrier-based fleet operations. Pratt reached an agreement with new Army Chief of Staff Douglas MacArthur

Douglas MacArthur (26 January 18805 April 1964) was an American military leader who served as General of the Army for the United States, as well as a field marshal to the Philippine Army. He had served with distinction in World War I, was C ...

that the Air Corps would assume responsibility for coastal defense (traditionally a primary function of the Army but a secondary, wartime function of the Navy) beyond the range of the Army's Coast Artillery guns, ending the Navy's apparent duplication of effort in coastal air operations. The agreement, intended as a modification of the Joint Action statement on coastal defense issued in 1926, was not endorsed by the Joint Army-Navy BoardThe Joint Army-Navy Board was the rudimentary precursor of the Joint Chiefs of Staff

The Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) is the body of the most senior uniformed leaders within the United States Department of Defense, that advises the president of the United States, the secretary of defense, the Homeland Security Council and the ...

. and never had authority other than a personal agreement between the two heads of service. Though the Navy repudiated the statement when Pratt retired in 1934, the Air Corps clung to the mission, and provided itself with the basis for development of long-range bombers and creating new doctrine to employ them.

The formulation of theories of strategic bombing

Strategic bombing is a military strategy used in total war with the goal of defeating the enemy by destroying its morale, its economic ability to produce and transport materiel to the theatres of military operations, or both. It is a systematica ...

gave new impetus to the argument for an independent air force. Strategic or long-range bombardment was intended to destroy an enemy's industry and war-making potential, and only an independent service would have a free hand to do so. But despite what it perceived as "obstruction" from the War Department, much of which was attributable to a shortage of funds, the Air Corps made great strides during the 1930s. A doctrine emerged that stressed precision bombing of industrial targets by heavily armed long-range aircraft.

This doctrine resulted because of several factors. The Air Corps Tactical School moved in July 1931 to Maxwell Field

Maxwell Air Force Base , officially known as Maxwell-Gunter Air Force Base, is a United States Air Force (USAF) installation under the Air Education and Training Command (AETC). The installation is located in Montgomery, Alabama, United States. O ...

, Alabama

(We dare defend our rights)

, anthem = "Alabama (state song), Alabama"

, image_map = Alabama in United States.svg

, seat = Montgomery, Alabama, Montgomery

, LargestCity = Huntsville, Alabama, Huntsville

, LargestCounty = Baldwin County, Al ...

, where it taught a 36-week course for junior and mid-career officers that included military aviation theory. The Bombardment Section, under the direction of its chief, Major Harold L. George

Harold Lee George (July 19, 1893 – February 24, 1986) was an American aviation pioneer who helped shape and promote the concept of daylight precision bombing. An outspoken proponent of the industrial web theory, George taught at the Air Corps T ...

, became influential in the development of doctrine and its dissemination throughout the Air Corps. Nine of its instructors became known throughout the Air Corps as the "Bomber Mafia

The Bomber Mafia were a close-knit group of American military men who believed that long-range heavy bomber aircraft in large numbers were able to win a war. The derogatory term "Bomber Mafia" was used before and after World War II by those in t ...

", eight of whom (including George) went on to be generals during World War II. Conversely, pursuit tacticians, primarily Capt. Claire Chennault

Claire Lee Chennault (September 6, 1893 – July 27, 1958) was an American military aviator best known for his leadership of the "Flying Tigers" and the Chinese Air Force in World War II.

Chennault was a fierce advocate of "pursuit" or fighter ...

, Chief of the school's Pursuit Section, found their influence waning because of repeated performance failures of pursuit aviation. Finally, the doctrine represented the Air Corps' attempt to develop autonomy from the General Staff, which enforced subordination of the air arm by limiting it to support of ground forces and defense of United States territory.

Technological advances in bombers

New bomber types under development clearly outperformed new pursuit types, particularly in speed and altitude, then considered the primary defenses against interception. In both 1932 and 1933, large-scale maneuvers found fighters unable to climb to altitude quickly enough to intercept attacking B-9 and B-10 prototypes, a failure so complete that Westover, following the 1933 maneuvers, actually proposed elimination of pursuits altogether.

1933 was a pivotal year in the advancement of aviation technology in which the all-metal airplane came of age, "practically overnight" in the words of one historian, because of the availability of the first practical

New bomber types under development clearly outperformed new pursuit types, particularly in speed and altitude, then considered the primary defenses against interception. In both 1932 and 1933, large-scale maneuvers found fighters unable to climb to altitude quickly enough to intercept attacking B-9 and B-10 prototypes, a failure so complete that Westover, following the 1933 maneuvers, actually proposed elimination of pursuits altogether.

1933 was a pivotal year in the advancement of aviation technology in which the all-metal airplane came of age, "practically overnight" in the words of one historian, because of the availability of the first practical variable-pitch propeller Variable-pitch propeller can refer to:

*Variable-pitch propeller (marine)

*Variable-pitch propeller (aeronautics)

In aeronautics, a variable-pitch propeller is a type of propeller (airscrew) with blades that can be rotated around their long a ...

. Coupled with "best weight" design of airframes, the controllable pitch propeller resulted in an immediate doubling of speeds and operating ranges without decreasing aircraft weights or increasing engine horsepower, exemplified by the civil Douglas DC-1

The Douglas DC-1 was the first model of the famous American DC (Douglas Commercial) commercial transport aircraft series. Although only one example of the DC-1 was produced, the design was the basis for the DC-2 and DC-3, the latter of which bei ...

transport and the military Martin B-10 bomber.Smith (1998), p. 10.

The B-10 featured innovations that became standard internationally for the next decade: an all-metal low wing monoplane, closed cockpits, rotating gun turrets, retractable landing gear, internal bomb bay, high-lift device

In aircraft design and aerospace engineering, a high-lift device is a component or mechanism on an aircraft's wing that increases the amount of lift (force), lift produced by the wing. The device may be a fixed component, or a movable mechanism w ...

s and full engine cowlings.Eden and Moeng (2002), p. 931. The B-10 proved to be so superior that as its 14 operational test models were delivered in 1934 they were fed into the Air Corps mail operation, and despite some glitches caused by pilot unfamiliarity with the innovations,Two YB-10s were landed with their landing gear still up, both by experienced aviators, one a major with 100 hours in aircraft with retractable gear. (Maurer 1987, p. 311) were a bright spot. The first action to repair the damaged image of the Air Corps involved the movement of ten YB-10s from Bolling Field to Alaska, ostensibly for an airfield survey, but timed to coincide with the release of the Baker Board's report in July.

The successful development of the B-10 and subsequent orders for more than 150 (including its B-12 variant) continued the hegemony of the bomber within the Air Corps that resulted in a feasibility study for a 35-ton 4-engined bomber (the Boeing XB-15

The Boeing Company () is an American multinational corporation that designs, manufactures, and sells airplanes, rotorcraft, rockets, satellites, telecommunications equipment, and missiles worldwide. The company also provides leasing and product ...

). While it was later found to be unsuitable for combat because the power of existing engines was inadequate for its weight, the XB-15 led to the design of the smaller Model 299, later to become the Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress

The Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress is a four-engined heavy bomber developed in the 1930s for the United States Army Air Corps (USAAC). Relatively fast and high-flying for a bomber of its era, the B-17 was used primarily in the European Theater ...

, whose first flight was at the end of July 1935. By that time the Air Corps had two projects in place for the development of longer-ranged bombers, Project A for a bomber with a ferry range of , and Project D, for one of a range of up to .Cate (1945), p. 13Smith (1998), p. 12. In June 1936 the Air Corps requested 11 B-15s and 50 B-17s for reinforcing hemispheric defense forces in Hawaii, Alaska, and Panama. The request was rejected on the basis that there were no strategic requirements for aircraft of such capabilities.Cate (1945), p. 17.

General Staff resistance to Air Corps doctrine

The Army and Navy, both cognizant of the continuing movement within the Air Corps for independence, cooperated to resist it. On 11 September 1935, the Joint Board, at the behest of the Navy and with the concurrence of MacArthur, issued a new "Joint Action Statement" that once again asserted the limited role of the Air Corps as an auxiliary to the "mobile Army" in all its missions, including coastal defense. The edict was issued with the intent of again shoving an upstart Air Corps back into its place. However, the bomber advocates interpreted its language differently, concluding that the Air Corps could conduct long-range reconnaissance, attack approaching fleets, reinforce distant bases, and attack enemy air bases, all in furthering its mission to prevent an air attack on America.The Joint Action Statement fostered a lack of inter-service cooperation on coastal defense that continued until theJapanese attack on Pearl Harbor

The attack on Pearl HarborAlso known as the Battle of Pearl Harbor was a surprise military strike by the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service upon the United States against the naval base at Pearl Harbor in Honolulu, Territory of Hawaii, ju ...

. As late as 14 October 1941, CNO Adm. Harold Stark insisted that the "proper" role of Army aviation in coastal defense was support of Navy operations. (Shiner, "The Coming of the GHQ Air Force", p. 121)

A month later (15 October 1935), the General Staff released a revision of the doctrinal guide for the Air Corps, training regulation TR 440-15 ''Employment of the Air Forces of the Army''.Since 1923 Army doctrine had been stated in '' Field Service Regulations'', which were general in character, and ''Training Regulations,'' which stated combat principles for each combatant arm. TR 440-15 had been first issued on 26 January 1926 as ''Fundamental Principles for the Employment of the Air Service''. Coincidentally, Col. William L. Mitchell resigned from the service the day following its issuance. This dichotomy of regulations and principles ended in 1939 with the creation of field manuals. A year earlier MacArthur had changed TR 440-15 to clarify "the Air Corps's place in the scheme of national defense and ... (to do away with) ... misconceptions and interbranch prejudices." The General Staff characterized its latest revision as a "compromise" with airpower advocates, to mitigate public criticism of the Joint Action Statement, but the newest revision parroted the anti-autonomy conclusions of the Drum and Baker Boards, and reasserted its long-held position (and that of the Secretary Dern)Dern's characterization of the Air Corps' role in February 1934 as "''subordinated like all other elements to whatever team it happens to accompany''" leaves no doubt as to the Army's position about its purpose. that auxiliary support of the ground forces was the primary mission of the Air Corps. TR 440-15 did acknowledge some doctrinal principles asserted by the ACTS (including the necessity of destroying an enemy's air forces and concentrating air forces against primary objectives) and recognized that future wars would probably entail some missions "beyond the sphere of influence of the Ground Forces" (strategic bombardment), but it did not attach any importance to prioritization of targets, weakening its effectiveness as doctrine. The Air Corps in general assented to the changes, as it did to other compromises of the period, as acceptable for the moment. TR 440-15 remained the doctrinal position of the Air Corps until it was superseded by the first Air Corps Field Manual, FM 1–5 ''Employment of Aviation of the Army'', on 15 April 1940.In March 1939 the Secretary of War created an "Air Board" chaired by Arnold and instructed it to submit a recommendation for organization and doctrine of the Air Corps. Its report, submitted to Chief of Staff Marshall on 1 September 1939, represented an Army-wide perspective. It became the basis for FM 1–5, and recognized that the United States was then on the strategic defensive. Its view was conservative and "a considerable attenuation of air doctrine" as espoused by the ACTS. However, it did correct the omissions of TR 440-15 and reasserted that centralized control by an airman in any combat role was essential for efficiency. Ironically, Gen. Andrews had by then become Army G-3 and reported to Marshall that the manual "did not endorse the radical theory of air employment". FM 1–5 was followed by supplemental doctrine Air Corps Field Manuals FM 1–15 ''Tactics and Technique of Air Fighting'' (pursuit) on 9 September 1940, FM 1–10 ''Tactics and Technique of Air Attack'' (bombardment) on 20 November 1940, FM 1–20 ''Tactics and Technique of Air Reconnaissance and Observation'' on 10 February 1941, War Department Basic Field Manual FM 31–35 ''Aviation in Support of Ground Forces'' on 9 April 1942, and Army Air Forces Field Manual FM 1–75 ''Combat Orders'' on 16 June 1942. FM 1–5 was itself superseded after just three years following disputes over control of air power in North Africa by FM 100-20 ''Command and Employment of Air Power'' (Field Service Regulations) on 21 July 1943 in what many in the Army Ground Forces viewed as the Army Air Forces' "Declaration of Independence." (AGF Historical Study No. 35, p. 47)

In the fall of 1937, the Army War College's course on the use of airpower reiterated the General Staff position and taught that airpower was of limited value when employed independently. Using attaché reports from both Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

and Ethiopia

Ethiopia, , om, Itiyoophiyaa, so, Itoobiya, ti, ኢትዮጵያ, Ítiyop'iya, aa, Itiyoppiya officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a landlocked country in the Horn of Africa. It shares borders with Eritrea to the ...

, and endorsed by a senior Air Corps instructor, Col. Byron Q. Jones

Byron Quinby Jones (April 9, 1888 – March 30, 1959) was a pioneer aviator and an officer in the United States Army. Jones began and ended his career as a cavalry officer, but for a quarter century between 1914 and 1939, he was an aviator in the ...

,Jones, an aviation pioneer and formerly a cavalry officer, was the rarest of Air Corps officers, a "true believer" in the General Staff doctrine. He was one of the few senior Air Corps officers never to have attended or instructed at the Air Corps Tactical School

The Air Corps Tactical School, also known as ACTS and "the Tactical School", was a military professional development school for officers of the United States Army Air Service and United States Army Air Corps, the first such school in the world. C ...

. Following his controversial endorsement, the War Department offered him a command with a temporary promotion to brigadier general. His autobiographical entry in the ''Cullum Register of USMA graduates'', however, states he declined "because of desire of superiors to retain his services within (the) continental U.S." Jones remained at the Army War College with its temporary promotion to colonel until September 1939, then accepted a cavalry assignment and transferred from the Air Corps. the course declared that the Flying Fortress concept had "died in Spain", and that airpower was useful mainly as "long range artillery." Air Corps officers in the G-3 Department of the General Staff pointed out that Jones' conclusions were inconsistent with the revised TR 440-15, but their views were dismissed by Deputy Chief of Staff Maj. Gen. Stanley Embick with the comment: "No doctrine is sacrosanct, and of all military doctrines, that of the Air Corps should be the last to be so regarded."Embick was formerly chief of the War Plans Division. In collaboration with Assistant Chief of Staff, G-4 (logistics) Brig. Gen. George R. Spalding, Embick was the driving force in minimizing all Air Corps R&D, squelching long-range bombers, and referring doctrinal disputes to the Joint Army-Navy Board for resolution. His influence ended the next year when he was replaced as Deputy Chief of Staff by George C. Marshall. (Greer 1985, p. 95)

At the same time, the General Staff ordered studies from all the service branches to develop drafts for the coming field manuals. The Air Corps Board, a function of the ACTS, submitted a draft in September 1938 that included descriptions of independent air operations, strategic air attacks, and air action against naval forces, all of which the General Staff rejected in March 1939. Instead, it ordered that the opening chapter of the Air Corps manual be a doctrinal statement developed by the G-3 that "left little doubt" that the General Staff's intention was "to develop and employ aviation in support of ground forces." The Air Corps Board, on the orders of Arnold, developed a secret study for "defense of the Monroe Doctrine

The Monroe Doctrine was a United States foreign policy position that opposed European colonialism in the Western Hemisphere. It held that any intervention in the political affairs of the Americas by foreign powers was a potentially hostile ac ...

" that recommended development of long-range, high altitude, high-speed aircraft for bombardment and reconnaissance to accomplish that defense.

The War Department, seeking to stifle procurement of the B-17 while belatedly recognizing that coordinated air-ground support had been long neglected, decided that it would order only two-engined "light" bombers in fiscal years 1939 through 1941. It also rejected further advancement of Project A, the development program for a very long range bomber.The rejection was by Secretary of War Woodring of a request by Westover in May 1938 that all funds remaining for the B-15 be applied to the development of a single Boeing Y1B-20

The Boeing Y1B-20 (Boeing 316) was designed as an improvement on the Boeing XB-15

The Boeing Company () is an American multinational corporation that designs, manufactures, and sells airplanes, rotorcraft, rockets, satellites, telecommunicat ...

, a design improvement of the B-15 with more powerful engines. Instead, the funds were diverted to buy more B-18s. (Greer 1985, p. 99) In collaboration with the Navy, the Joint Board (whose senior member was Army Chief of Staff Gen. Malin Craig

Malin Craig (August 5, 1875 – July 25, 1945) was a general in the United States Army who served as the 14th Chief of Staff of the United States Army from 1935 to 1939. He served in World War I and was recalled to active duty during World War II ...

) on 29 June 1938 issued a ruling that it could foresee no use for a long-range bomber in future conflict.J.B. 349. The ruling also further blocked the Project A bomber by decreeing that there was no reconnaissance need for an aircraft with range beyond that of the B-17. As a direct result, the last planned order of long-range bombers (67 B-17s) was cancelled by CraigThe funds, already appropriated, were then used to buy more light bombers. and a moratorium on further development of them was put into effect by restricting R&D funding to medium and light bombers. This policy would last less than a year, as it went against not only the trends of technological development, but against the geopolitical realities of coming war.The R&D restriction was rescinded in October 1938 following the Munich Conference, although the ban on buying more B-17s in FY 1940 and 1941 remained. (Greer 1985, p. 100) In August 1939 the Army's research and development program for 1941 was modified with the addition of nearly five million dollars to buy five long-range bombers for experimental purposes, resulting on 10 November 1939 in the request by Arnold of the developmental program that would create the Boeing B-29 Superfortress

The Boeing B-29 Superfortress is an American four-engined propeller-driven heavy bomber, designed by Boeing and flown primarily by the United States during World War II and the Korean War. Named in allusion to its predecessor, the B-17 Fl ...

, which was approved on 2 December.

Between 1930 and 1938 the Air Corps had obtained a mission in coastal defense that justified both the creation of a centralized strike force and the development of four-engined bombers, and over the resistance of the General Staff lobbied

In politics, lobbying, persuasion or interest representation is the act of lawfully attempting to influence the actions, policies, or decisions of government officials, most often legislators or members of regulatory agencies. Lobbying, which ...

for another mission, strategic bombardment, with which it could persuasively argue for independence from the Army. The cost of the General Staff's resistance in terms of preparedness had been severe, however. Its policies had resulted in the acquisition of obsolete aircraft as first-line equipment, stifled design development in the private sector of better types, retarded the development of radar and ordnance, and handicapped training, doctrine, and offensive organization by reneging on commitments to acquire the B-17. "From October 1935 until 30 June 1939, the Air Corps requested 206 B-17's and 11 B-15's. Yet because of cancellations and reductions of these requests by the War Department, 14 four-engine planes were delivered to the air force up to the outbreak of World War II in September 1939."

GHQ Air Force

A major step toward creation of a separate air force occurred on 1 March 1935 with the activation of a centralized, air force-level command headed by an aviator answering directly to the ArmyChief of Staff

The title chief of staff (or head of staff) identifies the leader of a complex organization such as the armed forces, institution, or body of persons and it also may identify a principal staff officer (PSO), who is the coordinator of the supporti ...

. Called the ''General Headquarters Air Force'', the organization had existed in Army planning since 1924 as a subordinate element of Army General Headquarters, which would be activated to control all Army units in case of war mobilization. In anticipation of military intervention in Cuba in 1933,A coup styled "the revolt of the sergeants" seized the Cuban military and replaced a provisional government sponsored by the Roosevelt Administration with a junta. Although Roosevelt was disposed to intervention as a last resort, warnings that he intended to intervene under the Treaty of 1903 were made to the revolutionaries. the headquarters had been created on 1 October but not staffed.Four ground force field army headquarters were established at the same time. The Drum Board of 1933 had first endorsed the concept, but as a means of reintegrating the Air Corps into control by the General Staff, in effect reining it in.Craven and Cate Vol. 1, p. 31

Among the recommendations of the Baker Board, established in the wake of the Air Mail scandal, was that the proposals of the Drum Board be adopted: an increase in strength to 2,320 aircraft and establishment of GHQ Air Force as a permanent peacetime tactical organization, both to ameliorate the pressures for a separate air force and to exploit emerging capabilities in airpower. In the absence of a general headquarters (i.e. peacetime), GHQ Air Force would report to the General Staff. The War Plans Division of the Army reacted to the recommendations of the Baker Board by insisting that men and modern equipment for seven army divisionsThese divisions were specifically four infantry and three horse cavalry. be procured before any increase in the Air Corps was begun, and opposed any immediate attempt to bring the Air Corps up to the 1,800 plane-strength first authorized in 1926, for fear of antagonizing the Navy.Brig. Gen. Charles E. Kilbourne

Major General Charles Evans Kilbourne Jr. (December 23, 1872 – November 12, 1963) was the first American to earn the United States' three highest military decorations. As an officer in the United States Army he received the Medal of Honor for h ...

, at the core of the General Staff's disputes with the Air Corps and supervisor of the revision of TR 440-15, authored these suggestions. He also freely espoused his opinion that expansion of the Air Corps was primarily a "selfish" means of promotion for aviators at the expense of the rest of the Army. Although rapid promotion of youthful airmen became a cliche in World War II, during the inter-war years Air Service/Air Corps promotion lagged notoriously behind that of the other branches. On the 669-name promotion list for colonel in 1922, on which Kilbourne had been 76th, the first airman (later Chief of Air Corps James Fechet

James Edmond Fechet (August 21, 1877 – February 10, 1948) was a major general in the United States Army and the Chief of Air Corps 1927–1931. Men he had selected and worked with both on his staff and in other top Air Corps positions became k ...

) had been 354th. The 1,800 aircraft goal was never reached because of General Staff resistance to the "five-year plan", but the War Plans Division did deem it "acceptable" for implementation of War Plan Red-Orange. The Air Corps, based on studies of joint exercises held at Key West

Key West ( es, Cayo Hueso) is an island in the Straits of Florida, within the U.S. state of Florida. Together with all or parts of the separate islands of Dredgers Key, Fleming Key, Sunset Key, and the northern part of Stock Island, it cons ...

, Florida, found the number dangerously inadequate, concluding that 4,459 aircraft was the minimum needed to defend the United States against air attack in the event of War Plan Red-Orange. President Roosevelt approved an open-ended program to increase strength to 2,320 aircraft (albeit without any proviso for funding) in August 1934, and Secretary Dern approved the activation of GHQ Air Force in December 1934.

GHQ Air Force took control of all combat air units in the United States from the jurisdiction of corps area

A Corps area was a geographically-based organizational structure (military district) of the United States Army used to accomplish administrative, training and tactical tasks from 1920 to 1942. Each corps area included divisions of the Regular Army ...

commanders, where it had resided since 1920, and organized them operationally into a strike force of three wings.The wings were organized both functionally and geographically. The 1st was both the bombardment and the Pacific wing, the 2d the pursuit and Atlantic wing, and the 3rd the attack and Gulf Coast wing. The GHQ Air Force remained small in comparison to European air forces. On its first day of existence, the command consisted of 60 bombers, 42 attack aircraft, 146 pursuits, and 24 transports, amounting to 40% of strength in the tables of organization

A table of organization and equipment (TOE or TO&E) is the specified organization, staffing, and equipment of units. Also used in acronyms as 'T/O' and 'T/E'. It also provides information on the mission and capabilities of a unit as well as the un ...

. Administratively it organized the forces into four geographical districts (which later became the first four numbered air forces) that paralleled the four field army headquarters created in 1933.

The General Staff perceived its creation as a means of lessening Air Corps autonomy, not increasing it, however, and GHQ Air Force was a "coordinate component" equal to the Air Corps, not subject to its control. The organizations reported separately to the Chief of Staff, the Air Corps as the service element of the air arm, and GHQAF as the tactical element. However, all GHQ Air Force's members, along with members of units stationed overseas and under the control of local ground commanders, remained part of the Air Corps. This dual status and division of authority hampered the development of Air Corps for the next six years, as it had the Air Service during World War I, and was not overcome until the necessity of expanding the force occurred with the onset of World War II.Craven and Cate Vol. 1, pp. 31–33 The commanding general of GHQ Air Force, Maj. Gen. Frank M. Andrews

Lieutenant General Frank Maxwell Andrews (February 3, 1884 – May 3, 1943) was a senior officer of the United States Army and one of the founders of the United States Army Air Forces, which was later to become the United States Air Force. ...

, clashed philosophically with Westover over the direction in which the air arm was heading, adding to the difficulties, with Andrews in favor of autonomy and Westover not only espousing subordination to the Army chain of command but aggressively enforcing his prohibitions of any commentary opposed to current policy. Andrews, by virtue of being out from Westover's control, had picked up the mantle of the radical airmen, and Westover soon found himself on "the wrong side of history" as far as the future of the Air Corps was concerned.Andrews and Westover were both 1906 graduates of West Point, with Andrews graduating one position higher in class standings. Andrews had originally been a cavalryman, and had married into the inner circles in Washington, while Westover, a former infantry officer with the unfortunate nickname of "Tubby," had pursued his career with bulldog-like determination. He had not learned to fly until he was 40 years of age and was a reluctant participant in Washington's social environs, usually depending on his assistant Hap Arnold to fulfill the protocol role. As early as 5 May 1919, in a memo to Director of Air Service Charles Menoher for whom he was assistant executive officer, Westover had demonstrated a loyalty to subordination, urging the relief of Billy Mitchell from his position as Third Assistant Executive (S-3) of the Air Service—along with his division heads—if their advocacy of positions not conforming to Army policy did not cease.

Lines of authority were also blurred as GHQ Air Force controlled only combat flying units within the continental United States. The Air Corps was responsible for training, aircraft development, doctrine, and supply, while the ground forces corps area commanders still controlled installations and the personnel manning them. An example of the difficulties this arrangement imposed on commanders was that while the commander of GHQ Air Force was responsible for the discipline of his command, he had no court martial

A court-martial or court martial (plural ''courts-martial'' or ''courts martial'', as "martial" is a postpositive adjective) is a military court or a trial conducted in such a court. A court-martial is empowered to determine the guilt of memb ...

authority over his personnel, which was retained by the corps area commander. Base commanders of Air Corps installations reported to as many as four different higher echelons.Mooney (1956), p. 2The base commander of Selfridge Field was responsible for various aspects of administration to the CG of GHQAF, the Chief of the Air Corps, the commander of the Sixth Corps Area, and the Chief of the Air Materiel Division. The issue of control of bases was ameliorated in 1936 when GHQAF bases were exempted from corps area authority on recommendation of the Inspector General's Department, but in November 1940 it was restored again to Corps Area control when Army General Headquarters was activated.

In January 1936, the Air Corps contracted with

In January 1936, the Air Corps contracted with Boeing

The Boeing Company () is an American multinational corporation that designs, manufactures, and sells airplanes, rotorcraft, rockets, satellites, telecommunications equipment, and missiles worldwide. The company also provides leasing and product ...

for thirteen Y1B-17 Flying Fortress

The Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress is a four-engined heavy bomber developed in the 1930s for the United States Army Air Corps (USAAC). Relatively fast and high-flying for a bomber of its era, the B-17 was used primarily in the European Theate ...

prototypes, enough to equip one squadron for operational testing and a thirteenth aircraft for stress testing, with deliveries made from January to August 1937. The cost of the aircraft disturbed Secretary of War

The secretary of war was a member of the U.S. president's Cabinet, beginning with George Washington's administration. A similar position, called either "Secretary at War" or "Secretary of War", had been appointed to serve the Congress of the ...

Harry Woodring

Harry Hines Woodring (May 31, 1887September 9, 1967) was an American politician. A Democrat, he was the 25th Governor of Kansas and the United States Assistant Secretary of War from 1933 to 1936. His most important role was Secretary of War in Pr ...