U.S on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in

It is generally accepted that the first inhabitants of North America migrated from

It is generally accepted that the first inhabitants of North America migrated from

Claims of very early colonization of coastal New England by the Norse are disputed and controversial.

Claims of very early colonization of coastal New England by the Norse are disputed and controversial.  In the early days of colonization, many European settlers experienced food shortages, disease, and conflicts with Native Americans, such as in

In the early days of colonization, many European settlers experienced food shortages, disease, and conflicts with Native Americans, such as in

The

The  In the late 18th century, American settlers began to expand further westward, some of them with a sense of

In the late 18th century, American settlers began to expand further westward, some of them with a sense of

Irreconcilable sectional conflict regarding the enslavement of Africans and

Irreconcilable sectional conflict regarding the enslavement of Africans and

The United States remained neutral from the outbreak of

The United States remained neutral from the outbreak of

After World War II, the United States financed and implemented the

After World War II, the United States financed and implemented the  The growing

The growing

The List of states and territories of the United States, 48 contiguous states and the District of Columbia occupy a combined area of . Of this area, is contiguous land, composing 83.65% of total U.S. land area. About 15% is occupied by

The List of states and territories of the United States, 48 contiguous states and the District of Columbia occupy a combined area of . Of this area, is contiguous land, composing 83.65% of total U.S. land area. About 15% is occupied by

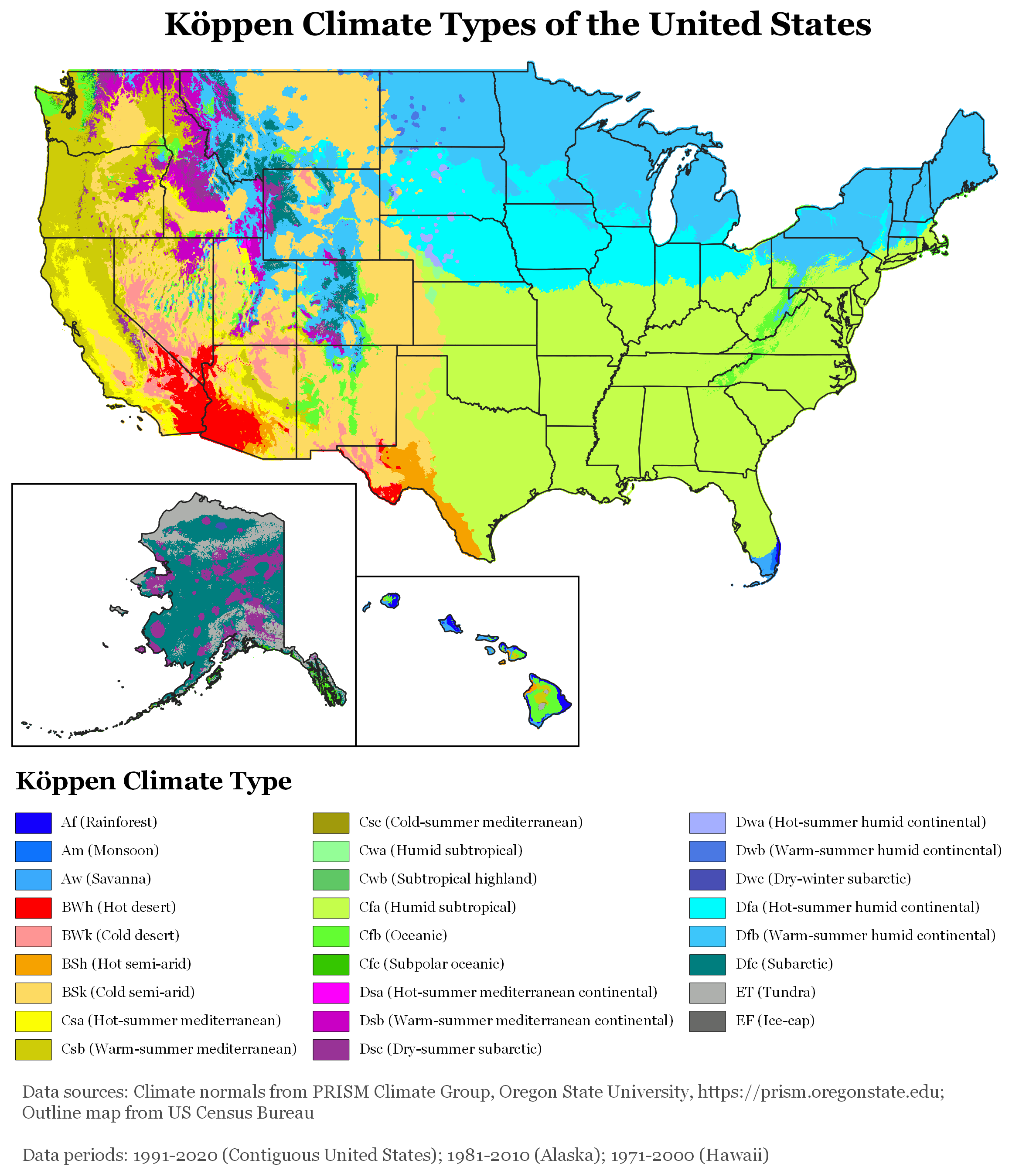

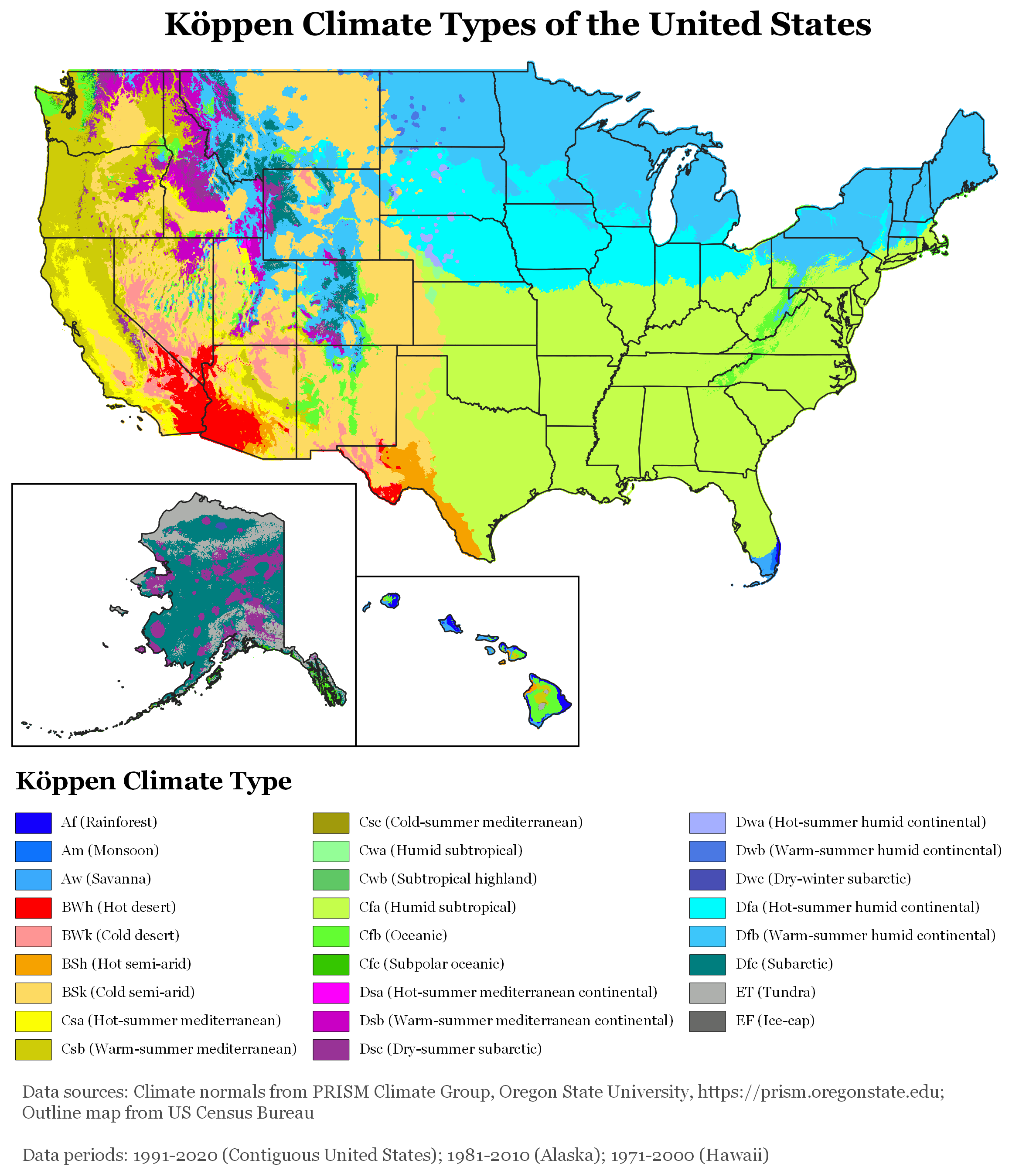

The United States, with its large size and geographic variety, includes most climate types. To the east of the 100th meridian west, 100th meridian, the climate ranges from humid continental climate, humid continental in the north to humid subtropical climate, humid subtropical in the south.

The Great Plains west of the 100th meridian are Semi-arid climate, semi-arid. Many mountainous areas of the American West have an alpine climate. The climate is Desert climate, arid in the Great Basin, desert in the Southwest, Mediterranean climate, Mediterranean in coastal California, and oceanic climate, oceanic in coastal Oregon and Washington (state), Washington and southern Alaska. Most of Alaska is Subarctic climate, subarctic or Polar climate, polar. Hawaii and the southern tip of

The United States, with its large size and geographic variety, includes most climate types. To the east of the 100th meridian west, 100th meridian, the climate ranges from humid continental climate, humid continental in the north to humid subtropical climate, humid subtropical in the south.

The Great Plains west of the 100th meridian are Semi-arid climate, semi-arid. Many mountainous areas of the American West have an alpine climate. The climate is Desert climate, arid in the Great Basin, desert in the Southwest, Mediterranean climate, Mediterranean in coastal California, and oceanic climate, oceanic in coastal Oregon and Washington (state), Washington and southern Alaska. Most of Alaska is Subarctic climate, subarctic or Polar climate, polar. Hawaii and the southern tip of

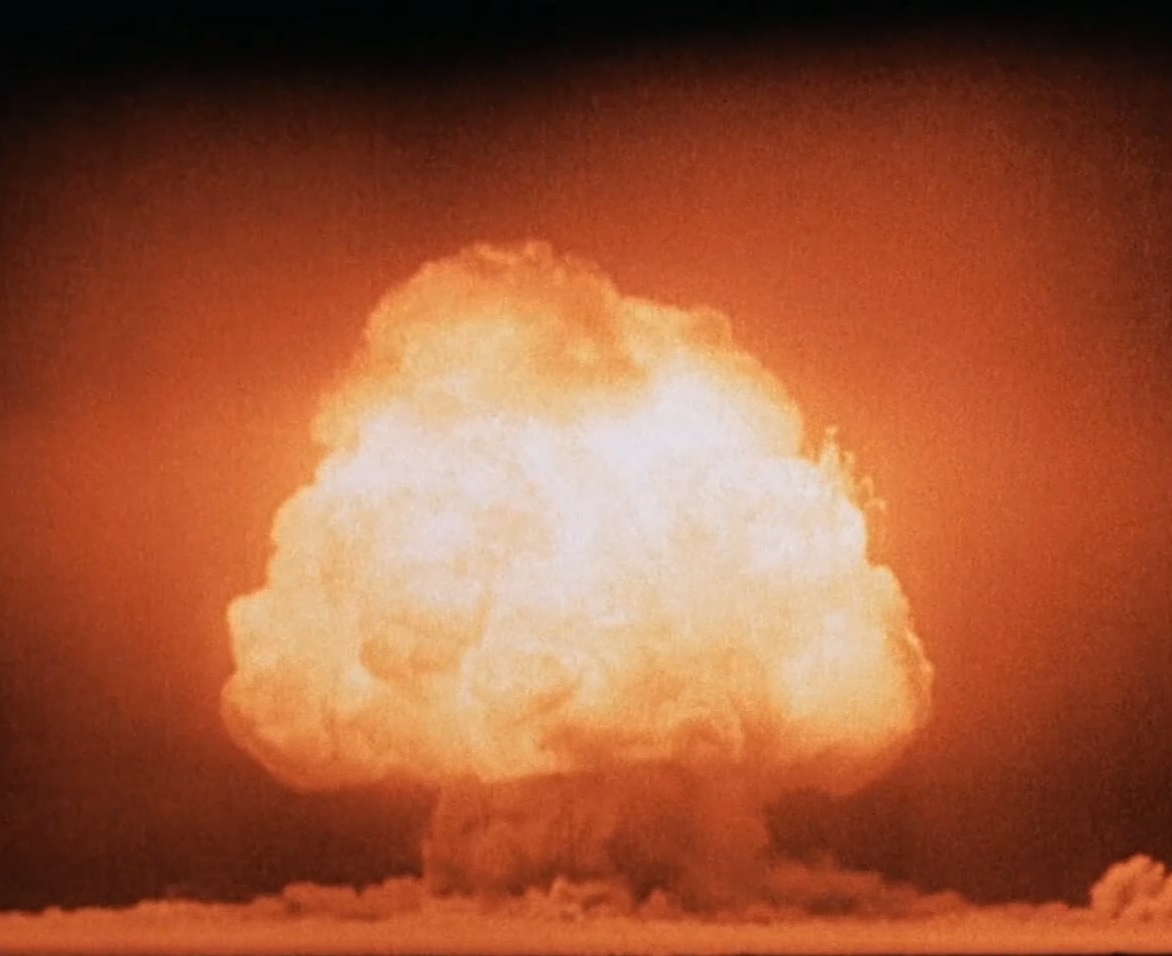

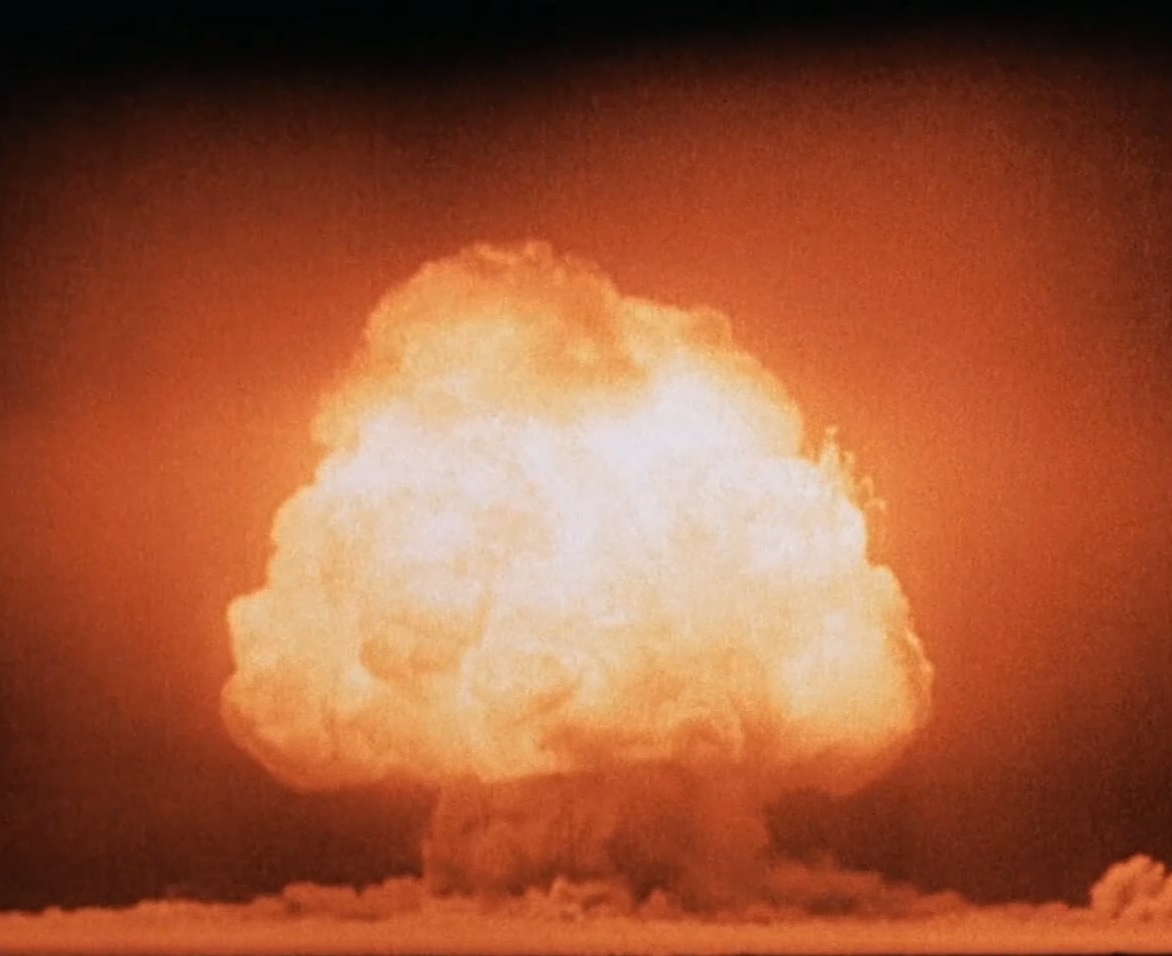

The president is the Commander-in-Chief of the United States, commander-in-chief of the United States Armed Forces and appoints its leaders, the United States Secretary of Defense, secretary of defense and the Joint Chiefs of Staff. The United States Department of Defense, Department of Defense, which is headquartered at the Pentagon near Washington, D.C., administers five of the six service branches, which are made up of the United States Army, Army, United States Marine Corps, Marine Corps, United States Navy, Navy, United States Air Force, Air Force, and United States Space Force, Space Force. The United States Coast Guard, Coast Guard is administered by the United States Department of Homeland Security, Department of Homeland Security in peacetime and can be transferred to the United States Department of the Navy, Department of the Navy in wartime. The United States spent $649 billion on its military in 2019, 36% of global military spending. At 4.7% of GDP, the percentage was the second-highest among all countries, after Saudi Arabia. It also has Nuclear weapons of the United States, more than 40% of the world's nuclear weapons, the second-largest after Russia.

In 2019, all six branches of the U.S. Armed Forces reported 1.4 million personnel on active duty. The Reserve components of the United States Armed Forces, Reserves and National Guard of the United States, National Guard brought the total number of troops to 2.3 million. The Department of Defense also employed about 700,000 civilians, not including Military-industrial complex, contractors. Military service in the United States is voluntary, although Conscription in the United States, conscription may occur in wartime through the Selective Service System. The United States has the third-largest combined armed forces in the world, behind the People's Liberation Army, Chinese People's Liberation Army and Indian Armed Forces.

Today, American forces can be rapidly deployed by the Air Force's large fleet of transport aircraft, the Navy's 11 active aircraft carriers, and Marine expeditionary units at sea with the Navy, and Army's XVIII Airborne Corps and 75th Ranger Regiment deployed by Air Force transport aircraft. The Air Force can strike targets across the globe through its fleet of strategic bombers, maintains the air defense across the United States, and provides close air support to Army and Marine Corps ground forces.

The Space Force operates the Global Positioning System, operates the Eastern Range, Eastern and Western Range (USSF), Western Ranges for all space launches, and operates the United States's United States Space Surveillance Network, Space Surveillance and United States national missile defense, Missile Warning networks. The military operates about 800 bases and facilities abroad, and maintains United States military deployments, deployments greater than 100 active duty personnel in 25 foreign countries.

The president is the Commander-in-Chief of the United States, commander-in-chief of the United States Armed Forces and appoints its leaders, the United States Secretary of Defense, secretary of defense and the Joint Chiefs of Staff. The United States Department of Defense, Department of Defense, which is headquartered at the Pentagon near Washington, D.C., administers five of the six service branches, which are made up of the United States Army, Army, United States Marine Corps, Marine Corps, United States Navy, Navy, United States Air Force, Air Force, and United States Space Force, Space Force. The United States Coast Guard, Coast Guard is administered by the United States Department of Homeland Security, Department of Homeland Security in peacetime and can be transferred to the United States Department of the Navy, Department of the Navy in wartime. The United States spent $649 billion on its military in 2019, 36% of global military spending. At 4.7% of GDP, the percentage was the second-highest among all countries, after Saudi Arabia. It also has Nuclear weapons of the United States, more than 40% of the world's nuclear weapons, the second-largest after Russia.

In 2019, all six branches of the U.S. Armed Forces reported 1.4 million personnel on active duty. The Reserve components of the United States Armed Forces, Reserves and National Guard of the United States, National Guard brought the total number of troops to 2.3 million. The Department of Defense also employed about 700,000 civilians, not including Military-industrial complex, contractors. Military service in the United States is voluntary, although Conscription in the United States, conscription may occur in wartime through the Selective Service System. The United States has the third-largest combined armed forces in the world, behind the People's Liberation Army, Chinese People's Liberation Army and Indian Armed Forces.

Today, American forces can be rapidly deployed by the Air Force's large fleet of transport aircraft, the Navy's 11 active aircraft carriers, and Marine expeditionary units at sea with the Navy, and Army's XVIII Airborne Corps and 75th Ranger Regiment deployed by Air Force transport aircraft. The Air Force can strike targets across the globe through its fleet of strategic bombers, maintains the air defense across the United States, and provides close air support to Army and Marine Corps ground forces.

The Space Force operates the Global Positioning System, operates the Eastern Range, Eastern and Western Range (USSF), Western Ranges for all space launches, and operates the United States's United States Space Surveillance Network, Space Surveillance and United States national missile defense, Missile Warning networks. The military operates about 800 bases and facilities abroad, and maintains United States military deployments, deployments greater than 100 active duty personnel in 25 foreign countries.

There are about 18,000 U.S. police agencies from local to federal level in the United States. Law in the United States is mainly Law enforcement in the United States, enforced by local police departments and sheriff's offices. The state police provides broader services, and Federal law enforcement in the United States, federal agencies such as the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) and the United States Marshals Service, U.S. Marshals Service have specialized duties, such as protecting civil rights, National Security of the United States, national security and enforcing U.S. federal courts' rulings and federal laws. State court (United States), State courts conduct most civil and criminal trials, and federal courts handle designated crimes and appeals from the state criminal courts.

, the United States has an List of countries by intentional homicide rate, intentional homicide rate of 7 per 100,000 people. A cross-sectional analysis of the World Health Organization Mortality Database from 2010 showed that United States homicide rates "were 7.0 times higher than in other high-income countries, driven by a gun homicide rate that was 25.2 times higher."

, the United States has the United States incarceration rate, sixth highest documented incarceration rate and Incarceration in the United States, second largest prison population in the world. In 2019, the total prison population for those sentenced to more than a year is 1,430,800, corresponding to a ratio of 419 per 100,000 residents and the lowest since 1995. Some estimates place that number higher, such Prison Policy Initiative's 2.3 million. Various states have attempted to Decarceration in the United States, reduce their prison populations via government policies and grassroots initiatives.

Although most nations have abolished capital punishment, it is sanctioned in the United States for certain federal and military crimes, and in 27 states out of 50 and in one territory. Several of these states have Moratorium (law), moratoriums on carrying out the penalty, each imposed by the state's governor. Since 1977, there have been more than 1,500 executions, giving the U.S. the sixth-highest number of executions in the world, following Capital punishment in China, China, Capital punishment in Iran, Iran, Capital punishment in Saudi Arabia, Saudi Arabia, Capital punishment in Iraq, Iraq, and Capital punishment in Egypt, Egypt. However, the number is trended down nationally, with Capital punishment in the United States#States without capital punishment, several states recently abolishing the penalty.

There are about 18,000 U.S. police agencies from local to federal level in the United States. Law in the United States is mainly Law enforcement in the United States, enforced by local police departments and sheriff's offices. The state police provides broader services, and Federal law enforcement in the United States, federal agencies such as the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) and the United States Marshals Service, U.S. Marshals Service have specialized duties, such as protecting civil rights, National Security of the United States, national security and enforcing U.S. federal courts' rulings and federal laws. State court (United States), State courts conduct most civil and criminal trials, and federal courts handle designated crimes and appeals from the state criminal courts.

, the United States has an List of countries by intentional homicide rate, intentional homicide rate of 7 per 100,000 people. A cross-sectional analysis of the World Health Organization Mortality Database from 2010 showed that United States homicide rates "were 7.0 times higher than in other high-income countries, driven by a gun homicide rate that was 25.2 times higher."

, the United States has the United States incarceration rate, sixth highest documented incarceration rate and Incarceration in the United States, second largest prison population in the world. In 2019, the total prison population for those sentenced to more than a year is 1,430,800, corresponding to a ratio of 419 per 100,000 residents and the lowest since 1995. Some estimates place that number higher, such Prison Policy Initiative's 2.3 million. Various states have attempted to Decarceration in the United States, reduce their prison populations via government policies and grassroots initiatives.

Although most nations have abolished capital punishment, it is sanctioned in the United States for certain federal and military crimes, and in 27 states out of 50 and in one territory. Several of these states have Moratorium (law), moratoriums on carrying out the penalty, each imposed by the state's governor. Since 1977, there have been more than 1,500 executions, giving the U.S. the sixth-highest number of executions in the world, following Capital punishment in China, China, Capital punishment in Iran, Iran, Capital punishment in Saudi Arabia, Saudi Arabia, Capital punishment in Iraq, Iraq, and Capital punishment in Egypt, Egypt. However, the number is trended down nationally, with Capital punishment in the United States#States without capital punishment, several states recently abolishing the penalty.

According to the

According to the

Securities and Exchange Commission (China). The List of the largest trading partners of the United States, largest U.S. trading partners are China, the European Union,

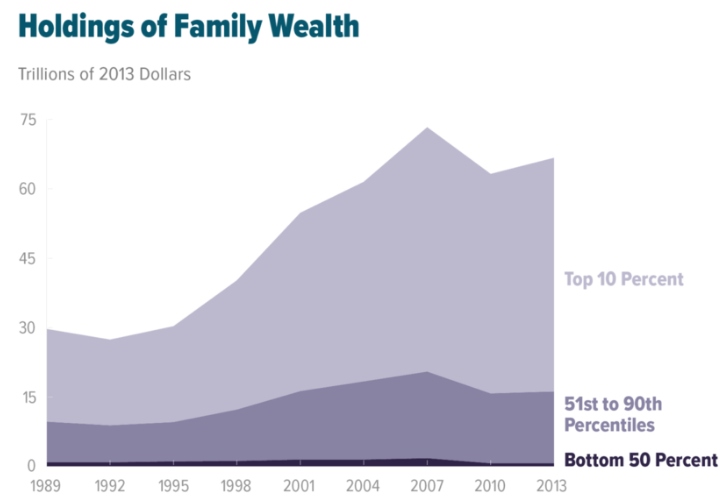

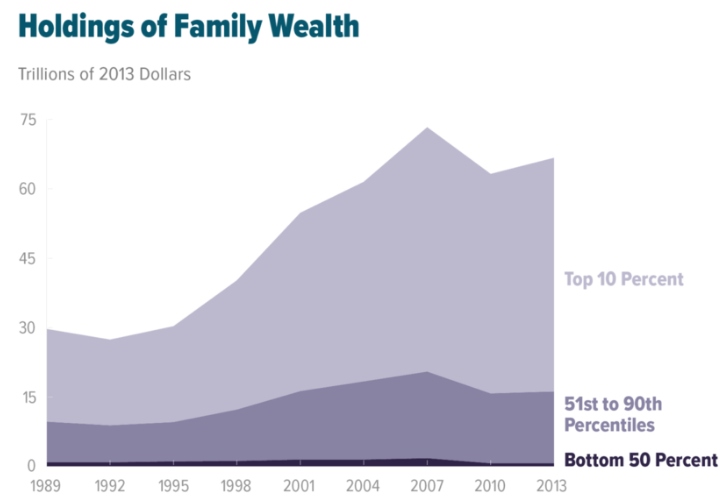

At $46,625 USD in 2021, American citizens have the highest median income in the world. Despite the fact that they only account for 4.24% of the World population, global population, they collectively List of countries by total wealth, possess 30.2% of the world's total wealth as of 2021, the largest percentage of any country. The U.S. also ranks first in the number of dollar billionaires and millionaires in the world, with 724 billionaires (as of 2021) and nearly 22 million millionaires (2021).

Wealth in the United States is Wealth inequality in the United States, highly concentrated; the richest 10% of the adult population own 72% of the country's household wealth, while the bottom 50% own just 2%. Income inequality in the United States, Income inequality in the U.S. remains at record highs, with the top fifth of earners taking home more than half of all income and giving the U.S. one of the widest income distributions among OECD members. The United States is the only advanced economy that does not List of statutory minimum employment leave by country, guarantee its workers paid vacation and is one of a few countries in the world without paid family leave as a legal right. The United States also has a higher percentage of low-income workers than almost any other developed nation, largely because of a weak collective bargaining system and lack of government support for at-risk workers.

There were about 567,715 sheltered and unsheltered Homelessness in the United States, homeless persons in the U.S. in January 2019, with almost two-thirds staying in an emergency shelter or transitional housing program. Attempts to combat homelessness include the Section 8 (housing), Section 8 housing voucher program and implementation of the Housing First strategy across all levels of government.

In 2011, Hunger in the United States#Children, 16.7 million children lived in food-insecure households, about 35% more than 2007 levels, though only 845,000 U.S. children (1.1%) saw reduced food intake or disrupted eating patterns at some point during the year, and most cases were not chronic. 40 million people, roughly 12.7% of the U.S. population, were living in poverty, including 13.3 million children. Of those impoverished, 18.5 million live in "deep poverty", family income below one-half of the federal government's poverty threshold.

At $46,625 USD in 2021, American citizens have the highest median income in the world. Despite the fact that they only account for 4.24% of the World population, global population, they collectively List of countries by total wealth, possess 30.2% of the world's total wealth as of 2021, the largest percentage of any country. The U.S. also ranks first in the number of dollar billionaires and millionaires in the world, with 724 billionaires (as of 2021) and nearly 22 million millionaires (2021).

Wealth in the United States is Wealth inequality in the United States, highly concentrated; the richest 10% of the adult population own 72% of the country's household wealth, while the bottom 50% own just 2%. Income inequality in the United States, Income inequality in the U.S. remains at record highs, with the top fifth of earners taking home more than half of all income and giving the U.S. one of the widest income distributions among OECD members. The United States is the only advanced economy that does not List of statutory minimum employment leave by country, guarantee its workers paid vacation and is one of a few countries in the world without paid family leave as a legal right. The United States also has a higher percentage of low-income workers than almost any other developed nation, largely because of a weak collective bargaining system and lack of government support for at-risk workers.

There were about 567,715 sheltered and unsheltered Homelessness in the United States, homeless persons in the U.S. in January 2019, with almost two-thirds staying in an emergency shelter or transitional housing program. Attempts to combat homelessness include the Section 8 (housing), Section 8 housing voucher program and implementation of the Housing First strategy across all levels of government.

In 2011, Hunger in the United States#Children, 16.7 million children lived in food-insecure households, about 35% more than 2007 levels, though only 845,000 U.S. children (1.1%) saw reduced food intake or disrupted eating patterns at some point during the year, and most cases were not chronic. 40 million people, roughly 12.7% of the U.S. population, were living in poverty, including 13.3 million children. Of those impoverished, 18.5 million live in "deep poverty", family income below one-half of the federal government's poverty threshold.

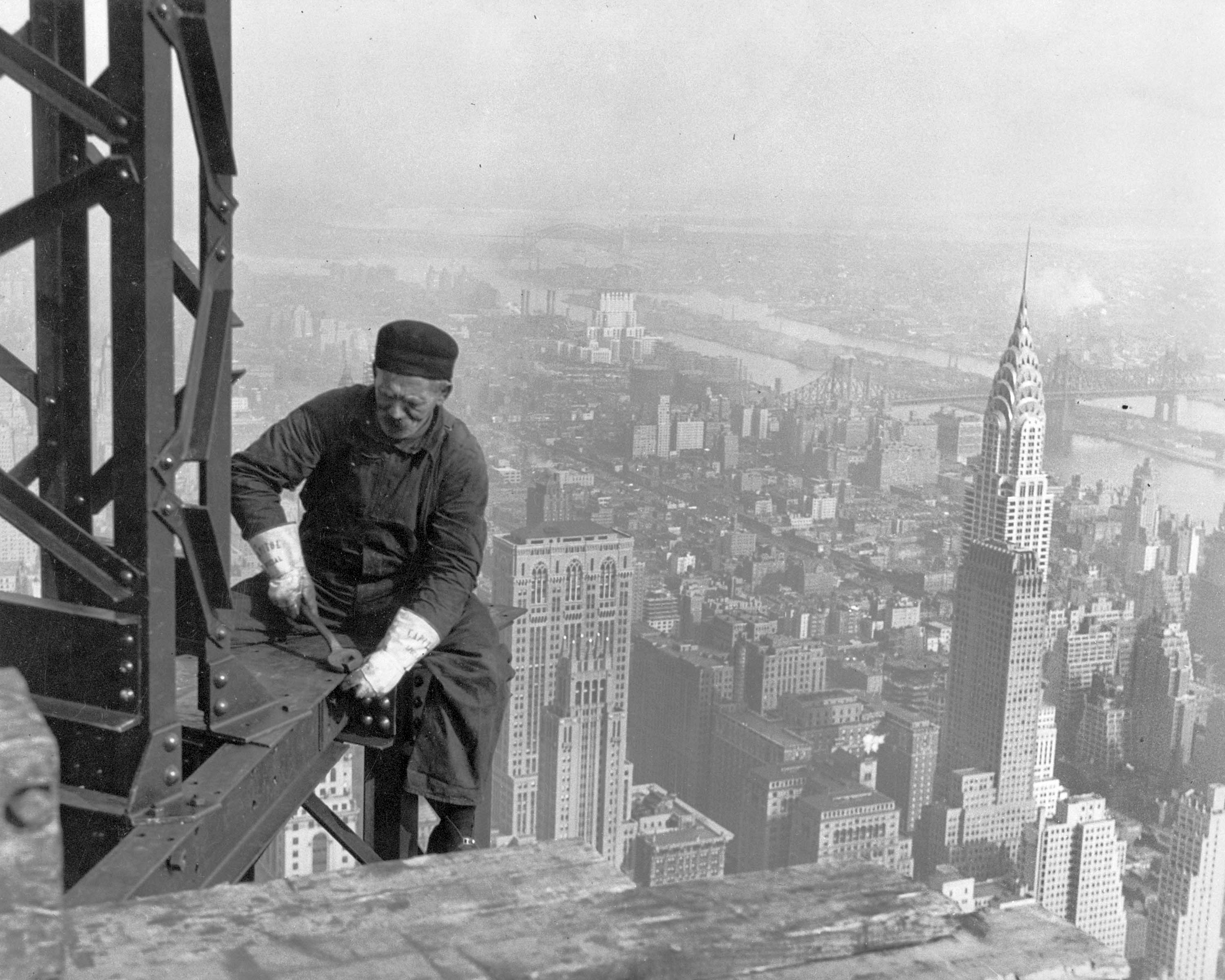

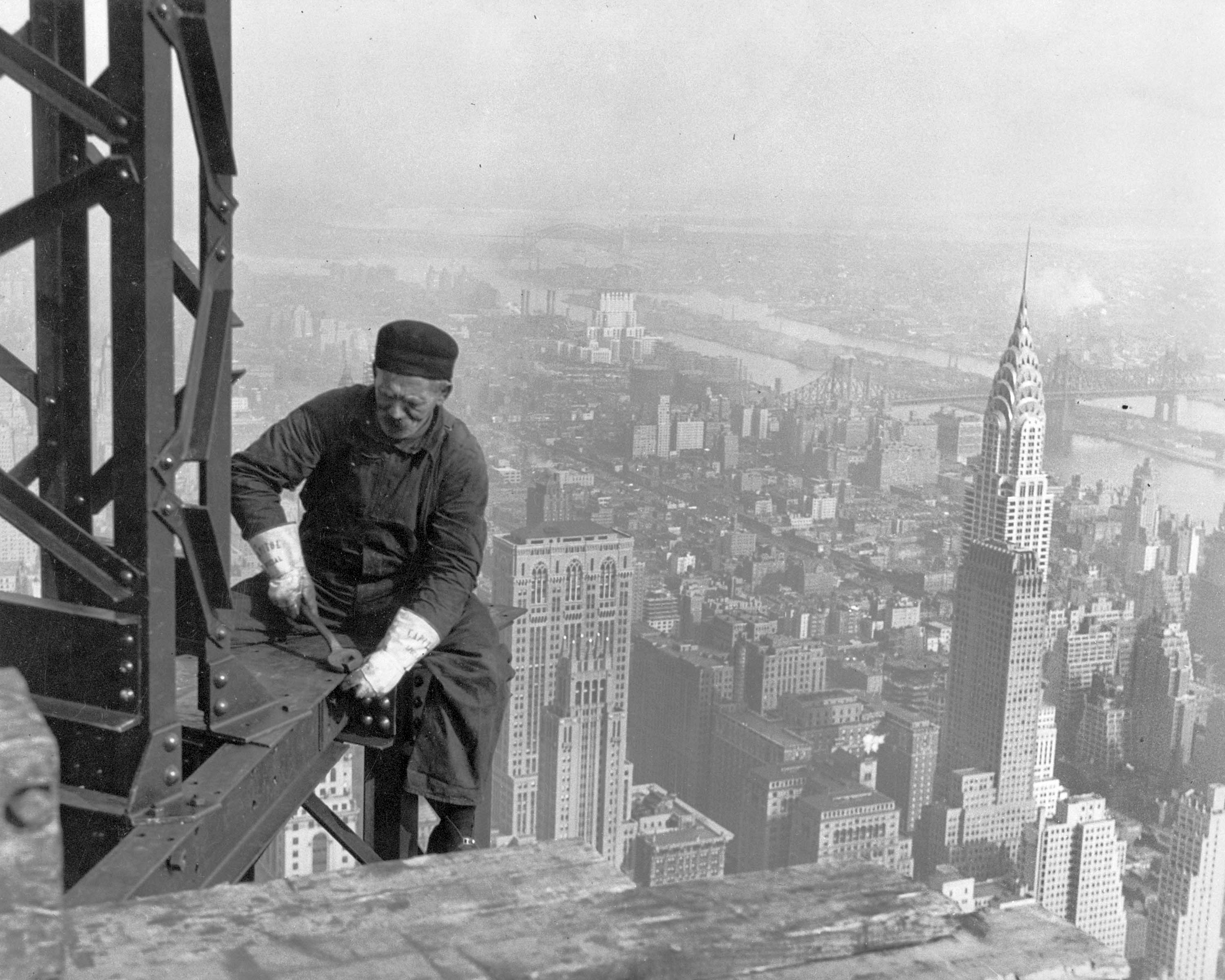

The United States has been a leader in technological innovation since the late 19th century and scientific research since the mid-20th century. Methods for producing interchangeable parts and the establishment of a machine tool industry enabled the American system of manufacturing, U.S. to have large-scale manufacturing of sewing machines, bicycles, and other items in the late 19th century. In the early 20th century, factory electrification, the introduction of the assembly line, and other labor-saving techniques created the system of mass production. In the 21st century, approximately two-thirds of research and development funding comes from the private sector. In 2020, the United States was the country with the List of countries by number of scientific and technical journal articles, second-highest number of published scientific papers and second most patents granted, both after China. In 2021, the United States launched a total of 51 spaceflights. (China reported 55.) The U.S. had 2,944 active satellites in space in December 2021, the highest number of any country.

In 1876, Alexander Graham Bell was awarded the first U.S. Invention of the telephone, patent for the telephone. Thomas Edison's Research institute, research laboratory developed the phonograph, the first Incandescent light bulb, long-lasting light bulb, and the first viable Kinetoscope, movie camera. The Wright brothers in 1903 made the Wright Flyer, first sustained and controlled heavier-than-air powered flight, and the automobile companies of Ransom E. Olds and Henry Ford popularized the assembly line in the early 20th century. The rise of fascism and Nazism in the 1920s and 30s led many European scientists, such as Albert Einstein, Enrico Fermi, and John von Neumann, to immigrate to the United States. During World War II, the Manhattan Project developed nuclear weapons, ushering in the Atomic Age. During the Cold War, competition for superior missile capability ushered in the

The United States has been a leader in technological innovation since the late 19th century and scientific research since the mid-20th century. Methods for producing interchangeable parts and the establishment of a machine tool industry enabled the American system of manufacturing, U.S. to have large-scale manufacturing of sewing machines, bicycles, and other items in the late 19th century. In the early 20th century, factory electrification, the introduction of the assembly line, and other labor-saving techniques created the system of mass production. In the 21st century, approximately two-thirds of research and development funding comes from the private sector. In 2020, the United States was the country with the List of countries by number of scientific and technical journal articles, second-highest number of published scientific papers and second most patents granted, both after China. In 2021, the United States launched a total of 51 spaceflights. (China reported 55.) The U.S. had 2,944 active satellites in space in December 2021, the highest number of any country.

In 1876, Alexander Graham Bell was awarded the first U.S. Invention of the telephone, patent for the telephone. Thomas Edison's Research institute, research laboratory developed the phonograph, the first Incandescent light bulb, long-lasting light bulb, and the first viable Kinetoscope, movie camera. The Wright brothers in 1903 made the Wright Flyer, first sustained and controlled heavier-than-air powered flight, and the automobile companies of Ransom E. Olds and Henry Ford popularized the assembly line in the early 20th century. The rise of fascism and Nazism in the 1920s and 30s led many European scientists, such as Albert Einstein, Enrico Fermi, and John von Neumann, to immigrate to the United States. During World War II, the Manhattan Project developed nuclear weapons, ushering in the Atomic Age. During the Cold War, competition for superior missile capability ushered in the

The United States's Rail transport in the United States, rail network, nearly all Standard-gauge railway, standard gauge, is the List of countries by rail transport network size, longest in the world, and exceeds . It handles mostly freight, with intercity passenger service provided by Amtrak to all but four states. The country's Inland waterways of the United States, inland waterways are the world's List of countries by waterways length, fifth-longest, and total .

Personal transportation is dominated by automobiles, which operate on a network of of public roads. The United States has the world's second-largest automobile market, and has the highest vehicle ownership per capita in the world, with 816.4 vehicles per 1,000 Americans (2014). In 2017, there were 255 million non-two wheel motor vehicles, or about 910 vehicles per 1,000 people.

The List of airlines of the United States, civil airline industry is entirely privately owned and has been largely Airline Deregulation Act, deregulated since 1978, while List of airports in the United States, most major airports are publicly owned. The three largest airlines in the world by passengers carried are U.S.-based; American Airlines is number one after its 2013 acquisition by US Airways. Of the List of the world's busiest airports by passenger traffic, world's 50 busiest passenger airports, 16 are in the United States, including the busiest, Hartsfield–Jackson Atlanta International Airport. Of the List of busiest container ports, fifty busiest container ports, four are located in the United States, of which the busiest is the Port of Los Angeles.

The United States's Rail transport in the United States, rail network, nearly all Standard-gauge railway, standard gauge, is the List of countries by rail transport network size, longest in the world, and exceeds . It handles mostly freight, with intercity passenger service provided by Amtrak to all but four states. The country's Inland waterways of the United States, inland waterways are the world's List of countries by waterways length, fifth-longest, and total .

Personal transportation is dominated by automobiles, which operate on a network of of public roads. The United States has the world's second-largest automobile market, and has the highest vehicle ownership per capita in the world, with 816.4 vehicles per 1,000 Americans (2014). In 2017, there were 255 million non-two wheel motor vehicles, or about 910 vehicles per 1,000 people.

The List of airlines of the United States, civil airline industry is entirely privately owned and has been largely Airline Deregulation Act, deregulated since 1978, while List of airports in the United States, most major airports are publicly owned. The three largest airlines in the world by passengers carried are U.S.-based; American Airlines is number one after its 2013 acquisition by US Airways. Of the List of the world's busiest airports by passenger traffic, world's 50 busiest passenger airports, 16 are in the United States, including the busiest, Hartsfield–Jackson Atlanta International Airport. Of the List of busiest container ports, fifty busiest container ports, four are located in the United States, of which the busiest is the Port of Los Angeles.

American state school, public education is operated by state and local governments and regulated by the United States Department of Education through restrictions on federal grants. In most states, children are required to attend school from the age of five or six (beginning with kindergarten or first grade) until they turn 18 (generally bringing them through twelfth grade, the end of high school); some states allow students to leave school at 16 or 17. Of Americans 25 and older, 84.6% graduated from high school, 52.6% attended some college, 27.2% earned a bachelor's degree, and 9.6% earned graduate degrees. The basic literacy rate is approximately 99%.

The United States has many private and public Lists of American institutions of higher education, institutions of higher education. The majority of the world's top Public university, public and Private university, private universities, as listed by various ranking organizations, are in the United States. There are also local community colleges with generally more open admission policies, shorter academic programs, and lower tuition. The U.S. spends more on education per student than any nation in the world, spending an average of $12,794 per year on public elementary and secondary school students in the 2016–2017 school year. As for public expenditures on higher education, the U.S. spends more per student than the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, OECD average, and more than all nations in combined public and private spending. Despite some student loan forgiveness programs in place, Student debt, student loan debt has increased by 102% in the last decade, and exceeded 1.7 trillion dollars as of 2022.

American state school, public education is operated by state and local governments and regulated by the United States Department of Education through restrictions on federal grants. In most states, children are required to attend school from the age of five or six (beginning with kindergarten or first grade) until they turn 18 (generally bringing them through twelfth grade, the end of high school); some states allow students to leave school at 16 or 17. Of Americans 25 and older, 84.6% graduated from high school, 52.6% attended some college, 27.2% earned a bachelor's degree, and 9.6% earned graduate degrees. The basic literacy rate is approximately 99%.

The United States has many private and public Lists of American institutions of higher education, institutions of higher education. The majority of the world's top Public university, public and Private university, private universities, as listed by various ranking organizations, are in the United States. There are also local community colleges with generally more open admission policies, shorter academic programs, and lower tuition. The U.S. spends more on education per student than any nation in the world, spending an average of $12,794 per year on public elementary and secondary school students in the 2016–2017 school year. As for public expenditures on higher education, the U.S. spends more per student than the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, OECD average, and more than all nations in combined public and private spending. Despite some student loan forgiveness programs in place, Student debt, student loan debt has increased by 102% in the last decade, and exceeded 1.7 trillion dollars as of 2022.

In a preliminary report, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) announced that U.S. life expectancy at birth had dropped to 76.4 years in 2021 (73.2 years for men and 79.1 years for women), down 0.9 years from 2020. This was the second year of overall decline, and the chief causes listed were the COVID-19 pandemic, accidents, drug overdoses, heart and liver disease, and suicides. Life expectancy was highest among Asians and Hispanics and lowest among Blacks and American Indian–Alaskan Native (AIAN (U.S. Census), AIAN) peoples. Starting in 1998, the average life expectancy in the U.S. fell behind that of other wealthy industrialized countries, and Americans' "health disadvantage" gap has been increasing ever since. The U.S. also has one of the highest Suicide in the United States, suicide rates among high-income countries, and approximately one-third of the U.S. adult population is obese and another third is overweight.

In 2010, coronary artery disease, lung cancer, stroke, chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases, and traffic collisions caused the most years of life lost in the U.S. Low back pain, major depressive disorder, depression, musculoskeletal disorders, neck pain, and anxiety caused the most years lost to disability. The most harmful risk factors were poor diet, tobacco smoking, obesity, Hypertension, high blood pressure, Hyperglycemia, high blood sugar, physical inactivity, and Alcohol consumption and health, alcohol consumption. Alzheimer's disease, substance use disorders, kidney disease, cancer, and falls caused the most additional years of life lost over their age-adjusted 1990 per-capita rates. Teenage pregnancy in the United States, Teenage pregnancy and Abortion in the United States, abortion rates in the U.S. are substantially higher than in other Western nations, especially among blacks and Hispanics.

The U.S. health care system far List of countries by total health expenditure (PPP) per capita, outspends that of any other nation, measured both in per capita spending and as a percentage of GDP but attains worse healthcare outcomes when compared to peer nations. The United States is the only developed nation Healthcare reform in the United States, without a system of universal health care, and a Health insurance coverage in the United States, significant proportion of the population that does not carry health insurance. The U.S., however, is a global leader in medical innovation, measured either in terms of revenue or the number of new drugs and devices introduced.Stats from 2007 Europ.Fed.of Pharm.Indust.and Assoc. Retrieved June 17, 2009, fro

In a preliminary report, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) announced that U.S. life expectancy at birth had dropped to 76.4 years in 2021 (73.2 years for men and 79.1 years for women), down 0.9 years from 2020. This was the second year of overall decline, and the chief causes listed were the COVID-19 pandemic, accidents, drug overdoses, heart and liver disease, and suicides. Life expectancy was highest among Asians and Hispanics and lowest among Blacks and American Indian–Alaskan Native (AIAN (U.S. Census), AIAN) peoples. Starting in 1998, the average life expectancy in the U.S. fell behind that of other wealthy industrialized countries, and Americans' "health disadvantage" gap has been increasing ever since. The U.S. also has one of the highest Suicide in the United States, suicide rates among high-income countries, and approximately one-third of the U.S. adult population is obese and another third is overweight.

In 2010, coronary artery disease, lung cancer, stroke, chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases, and traffic collisions caused the most years of life lost in the U.S. Low back pain, major depressive disorder, depression, musculoskeletal disorders, neck pain, and anxiety caused the most years lost to disability. The most harmful risk factors were poor diet, tobacco smoking, obesity, Hypertension, high blood pressure, Hyperglycemia, high blood sugar, physical inactivity, and Alcohol consumption and health, alcohol consumption. Alzheimer's disease, substance use disorders, kidney disease, cancer, and falls caused the most additional years of life lost over their age-adjusted 1990 per-capita rates. Teenage pregnancy in the United States, Teenage pregnancy and Abortion in the United States, abortion rates in the U.S. are substantially higher than in other Western nations, especially among blacks and Hispanics.

The U.S. health care system far List of countries by total health expenditure (PPP) per capita, outspends that of any other nation, measured both in per capita spending and as a percentage of GDP but attains worse healthcare outcomes when compared to peer nations. The United States is the only developed nation Healthcare reform in the United States, without a system of universal health care, and a Health insurance coverage in the United States, significant proportion of the population that does not carry health insurance. The U.S., however, is a global leader in medical innovation, measured either in terms of revenue or the number of new drugs and devices introduced.Stats from 2007 Europ.Fed.of Pharm.Indust.and Assoc. Retrieved June 17, 2009, fro

/ref> Government-funded health care coverage for the poor (

Americans have traditionally Stereotypes of Americans, been characterized by a strong work ethic, competitiveness, and individualism, as well as a unifying belief in an "American civil religion, American creed" emphasizing liberty, social equality, property rights, democracy, equality under the law, and a preference for limited government. Americans are extremely charitable by global standards: according to a 2016 study by the Charities Aid Foundation, Americans donated 1.44% of total GDP to charity, the List of countries by charitable donation, highest in the world by a large margin. The United States is home to a Multiculturalism, wide variety of ethnic groups, traditions, and values, and exerts major cultural influence Americanization, on a global scale. The country has been described as a society "built on a Moral universalism, universalistic cultural frame rooted in the natural laws of science and human rights."

The

Americans have traditionally Stereotypes of Americans, been characterized by a strong work ethic, competitiveness, and individualism, as well as a unifying belief in an "American civil religion, American creed" emphasizing liberty, social equality, property rights, democracy, equality under the law, and a preference for limited government. Americans are extremely charitable by global standards: according to a 2016 study by the Charities Aid Foundation, Americans donated 1.44% of total GDP to charity, the List of countries by charitable donation, highest in the world by a large margin. The United States is home to a Multiculturalism, wide variety of ethnic groups, traditions, and values, and exerts major cultural influence Americanization, on a global scale. The country has been described as a society "built on a Moral universalism, universalistic cultural frame rooted in the natural laws of science and human rights."

The

In the 18th and early 19th centuries, American art and literature took most of their cues from Europe, contributing to Western culture. Writers such as Washington Irving, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Edgar Allan Poe, and Henry David Thoreau established a distinctive American literary voice by the middle of the 19th century. Mark Twain and poet Walt Whitman were major figures in the century's second half; Emily Dickinson, virtually unknown during her lifetime, is recognized as an essential American poet.

A work seen as capturing fundamental aspects of the national experience and character—such as Herman Melville's ''Moby-Dick'' (1851), Twain's ''Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn'' (1885), F. Scott Fitzgerald's ''The Great Gatsby'' (1925) and Harper Lee's ''To Kill a Mockingbird'' (1960)—may be dubbed the "Great American Novel."

Thirteen U.S. citizens have won the Nobel Prize in Literature. William Faulkner, Ernest Hemingway and John Steinbeck are often named among the most influential writers of the 20th century. The Beat Generation writers opened up new literary approaches, as have postmodern literature, postmodernist authors such as John Barth, Thomas Pynchon, and Don DeLillo.

In the visual arts, the Hudson River School was a mid-19th-century movement in the tradition of European Realism (arts), naturalism. The 1913 Armory Show in New York City, an exhibition of European modern art, modernist art, shocked the public and transformed the U.S. art scene. Georgia O'Keeffe, Marsden Hartley, and others experimented with new, individualistic styles.

Major artistic movements such as the abstract expressionism of Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning and the pop art of Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein developed largely in the United States. The tide of modernism and then postmodernism has brought fame to American architects such as Frank Lloyd Wright, Philip Johnson, and Frank Gehry. Americans have long been important in the modern artistic medium of photography, with major photographers including Alfred Stieglitz, Edward Steichen, Edward Weston, and Ansel Adams.

In the 18th and early 19th centuries, American art and literature took most of their cues from Europe, contributing to Western culture. Writers such as Washington Irving, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Edgar Allan Poe, and Henry David Thoreau established a distinctive American literary voice by the middle of the 19th century. Mark Twain and poet Walt Whitman were major figures in the century's second half; Emily Dickinson, virtually unknown during her lifetime, is recognized as an essential American poet.

A work seen as capturing fundamental aspects of the national experience and character—such as Herman Melville's ''Moby-Dick'' (1851), Twain's ''Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn'' (1885), F. Scott Fitzgerald's ''The Great Gatsby'' (1925) and Harper Lee's ''To Kill a Mockingbird'' (1960)—may be dubbed the "Great American Novel."

Thirteen U.S. citizens have won the Nobel Prize in Literature. William Faulkner, Ernest Hemingway and John Steinbeck are often named among the most influential writers of the 20th century. The Beat Generation writers opened up new literary approaches, as have postmodern literature, postmodernist authors such as John Barth, Thomas Pynchon, and Don DeLillo.

In the visual arts, the Hudson River School was a mid-19th-century movement in the tradition of European Realism (arts), naturalism. The 1913 Armory Show in New York City, an exhibition of European modern art, modernist art, shocked the public and transformed the U.S. art scene. Georgia O'Keeffe, Marsden Hartley, and others experimented with new, individualistic styles.

Major artistic movements such as the abstract expressionism of Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning and the pop art of Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein developed largely in the United States. The tide of modernism and then postmodernism has brought fame to American architects such as Frank Lloyd Wright, Philip Johnson, and Frank Gehry. Americans have long been important in the modern artistic medium of photography, with major photographers including Alfred Stieglitz, Edward Steichen, Edward Weston, and Ansel Adams.

Hollywood, Los Angeles, Hollywood, a northern district of Los Angeles, California, is the leader in motion picture production and the most recognizable movie industry in the world. The major film studios of the United States are the primary source of the List of highest grossing films, most commercially successful and most ticket selling movies in the world.

The world's first commercial motion picture exhibition was given in New York City in 1894, using the Kinetoscope. Since the early 20th century, the U.S. film industry has largely been based in and around Hollywood, although in the 21st century an increasing number of films are not made there, and film companies have been subject to the forces of globalization. The Academy Awards, popularly known as the Oscars, have been held annually by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences since 1929, and the Golden Globe Awards have been held annually since January 1944.

Director D. W. Griffith, an American filmmaker during the silent film period, was central to the development of film grammar, and producer/entrepreneur Walt Disney was a leader in both animation, animated film and movie merchandising. Directors such as John Ford redefined the image of the American Old West, and, like others such as John Huston, broadened the possibilities of cinema with location shooting. The industry enjoyed its golden years, in what is commonly referred to as the "Classical Hollywood cinema, Golden Age of Hollywood", from the early sound period until the early 1960s, with screen actors such as John Wayne and Marilyn Monroe becoming iconic figures. In the 1970s, "New Hollywood" or the "Hollywood Renaissance" was defined by grittier films influenced by French and Italian realist pictures of the Aftermath of World War II, post-war period.

Theater in the United States derives from the old European theatrical tradition and has been heavily influenced by the Theatre of the United Kingdom, British theater. The central hub of the American theater scene has been Manhattan, with its divisions of Broadway theatre, Broadway, off-Broadway, and off-off-Broadway. Many movie and television stars have gotten their big break working in New York productions. Outside New York City, many cities have professional Regional theater in the United States, regional or resident theater companies that produce their own seasons, with some works being produced regionally with hopes of eventually moving to New York. The biggest-budget theatrical productions are musical theatre, musicals. U.S. theater also has an active community theater culture, which relies mainly on local volunteers who may not be actively pursuing a theatrical career.

Hollywood, Los Angeles, Hollywood, a northern district of Los Angeles, California, is the leader in motion picture production and the most recognizable movie industry in the world. The major film studios of the United States are the primary source of the List of highest grossing films, most commercially successful and most ticket selling movies in the world.

The world's first commercial motion picture exhibition was given in New York City in 1894, using the Kinetoscope. Since the early 20th century, the U.S. film industry has largely been based in and around Hollywood, although in the 21st century an increasing number of films are not made there, and film companies have been subject to the forces of globalization. The Academy Awards, popularly known as the Oscars, have been held annually by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences since 1929, and the Golden Globe Awards have been held annually since January 1944.

Director D. W. Griffith, an American filmmaker during the silent film period, was central to the development of film grammar, and producer/entrepreneur Walt Disney was a leader in both animation, animated film and movie merchandising. Directors such as John Ford redefined the image of the American Old West, and, like others such as John Huston, broadened the possibilities of cinema with location shooting. The industry enjoyed its golden years, in what is commonly referred to as the "Classical Hollywood cinema, Golden Age of Hollywood", from the early sound period until the early 1960s, with screen actors such as John Wayne and Marilyn Monroe becoming iconic figures. In the 1970s, "New Hollywood" or the "Hollywood Renaissance" was defined by grittier films influenced by French and Italian realist pictures of the Aftermath of World War II, post-war period.

Theater in the United States derives from the old European theatrical tradition and has been heavily influenced by the Theatre of the United Kingdom, British theater. The central hub of the American theater scene has been Manhattan, with its divisions of Broadway theatre, Broadway, off-Broadway, and off-off-Broadway. Many movie and television stars have gotten their big break working in New York productions. Outside New York City, many cities have professional Regional theater in the United States, regional or resident theater companies that produce their own seasons, with some works being produced regionally with hopes of eventually moving to New York. The biggest-budget theatrical productions are musical theatre, musicals. U.S. theater also has an active community theater culture, which relies mainly on local volunteers who may not be actively pursuing a theatrical career.

American folk music encompasses numerous music genres, variously known as traditional music, traditional folk music, contemporary folk music, or roots music. Many traditional songs have been sung within the same family or folk group for generations, and sometimes trace back to such origins as the British Isles, Mainland Europe, or Africa."Folk Music and Song", American Folklife Center, Library of Congress

American folk music encompasses numerous music genres, variously known as traditional music, traditional folk music, contemporary folk music, or roots music. Many traditional songs have been sung within the same family or folk group for generations, and sometimes trace back to such origins as the British Isles, Mainland Europe, or Africa."Folk Music and Song", American Folklife Center, Library of Congress

/ref> Among America's earliest composers was a man named William Billings who, born in Boston, composed patriotic hymns in the 1770s; Billings was a part of the Yankee tunesmiths, First New England School, who dominated American music during its earliest stages. Anthony Heinrich was the most prominent composer before the Civil War. From the mid- to late 1800s, John Philip Sousa of the late Romantic music, Romantic era composed numerous military songs—List of marches by John Philip Sousa, particularly marches—and is regarded as one of America's greatest composers. The rhythmic and lyrical styles of African-American music have significantly influenced Music of the United States, American music at large, distinguishing it from European and African traditions. Elements from folk idioms such as the blues and what is known as old-time music were adopted and transformed into popular music, popular genres with global audiences. Jazz was developed by innovators such as Louis Armstrong and Duke Ellington early in the 20th century. Country music developed in the 1920s, and rhythm and blues in the 1940s. Elvis Presley and Chuck Berry were among the pioneers of rock and roll in the mid-1950s. Rock bands such as Metallica, the Eagles (band), Eagles, and Aerosmith are among the List of best-selling music artists, highest grossing in worldwide sales. In the 1960s, Bob Dylan emerged from the American folk music revival, folk revival to become one of America's most celebrated songwriters. Mid-20th-century American pop stars such as Bing Crosby, Frank Sinatra, and Elvis Presley became global celebrities, as have artists of the late 20th century such as Prince (musician), Prince, Michael Jackson, Madonna, Whitney Houston, and Mariah Carey.

The four major broadcasters in the U.S. are the National Broadcasting Company (NBC), Columbia Broadcasting System (CBS), American Broadcasting Company (ABC), and Fox Broadcasting Company (FOX). The four major broadcast television networks are all commercial entities. Cable television in the United States, Cable television offers hundreds of channels catering to a variety of niches. , about 83% of Americans over age 12 listen to radio broadcasting, broadcast radio, while about 41% listen to podcasts. , there are 15,433 licensed full-power radio stations in the U.S. according to the U.S. Federal Communications Commission (FCC). Much of the public radio broadcasting is supplied by NPR, incorporated in February 1970 under the Public Broadcasting Act of 1967.

Well-known U.S. newspapers include ''The Wall Street Journal'', ''The New York Times'', and ''USA Today''. More than 800 publications are produced in Spanish, the second most commonly used language in the United States behind English. With very few exceptions, all the newspapers in the U.S. are privately owned, either by large chains such as Gannett Company, Gannett or The McClatchy Company, McClatchy, which own dozens or even hundreds of newspapers; by small chains that own a handful of papers; or, in a situation that is increasingly rare, by individuals or families. Major cities often have alternative newspapers to complement the mainstream daily papers, such as New York City's ''The Village Voice'' or Los Angeles' ''LA Weekly''. The five most popular websites used in the U.S. are Google, YouTube, Amazon (company), Amazon, Yahoo, and Facebook.

The Video games in the United States, American video game industry is the world's 2nd largest by revenue. It generated $90 billion in annual economic output in 2020. Furthermore, the video game industry contributed $12.6 billion in federal, state, and municipal taxes annually. Some of the largest video game companies like Activision Blizzard, Xbox, Sony Interactive Entertainment, Rockstar Games, and Electronic Arts are based in the United States. Some of the most popular and best selling video games like The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim, Call of Duty: Modern Warfare (2019 video game), Call of Duty: Modern Warfare and Diablo III are made by American Video game developer, developers. The American video gaming business is still a significant employer. More than 143,000 individuals are employed directly and indirectly by video game companies throughout 50 states. The national compensation for direct workers is US$2.9 billion, or an average wage of US$121,000.

The four major broadcasters in the U.S. are the National Broadcasting Company (NBC), Columbia Broadcasting System (CBS), American Broadcasting Company (ABC), and Fox Broadcasting Company (FOX). The four major broadcast television networks are all commercial entities. Cable television in the United States, Cable television offers hundreds of channels catering to a variety of niches. , about 83% of Americans over age 12 listen to radio broadcasting, broadcast radio, while about 41% listen to podcasts. , there are 15,433 licensed full-power radio stations in the U.S. according to the U.S. Federal Communications Commission (FCC). Much of the public radio broadcasting is supplied by NPR, incorporated in February 1970 under the Public Broadcasting Act of 1967.

Well-known U.S. newspapers include ''The Wall Street Journal'', ''The New York Times'', and ''USA Today''. More than 800 publications are produced in Spanish, the second most commonly used language in the United States behind English. With very few exceptions, all the newspapers in the U.S. are privately owned, either by large chains such as Gannett Company, Gannett or The McClatchy Company, McClatchy, which own dozens or even hundreds of newspapers; by small chains that own a handful of papers; or, in a situation that is increasingly rare, by individuals or families. Major cities often have alternative newspapers to complement the mainstream daily papers, such as New York City's ''The Village Voice'' or Los Angeles' ''LA Weekly''. The five most popular websites used in the U.S. are Google, YouTube, Amazon (company), Amazon, Yahoo, and Facebook.

The Video games in the United States, American video game industry is the world's 2nd largest by revenue. It generated $90 billion in annual economic output in 2020. Furthermore, the video game industry contributed $12.6 billion in federal, state, and municipal taxes annually. Some of the largest video game companies like Activision Blizzard, Xbox, Sony Interactive Entertainment, Rockstar Games, and Electronic Arts are based in the United States. Some of the most popular and best selling video games like The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim, Call of Duty: Modern Warfare (2019 video game), Call of Duty: Modern Warfare and Diablo III are made by American Video game developer, developers. The American video gaming business is still a significant employer. More than 143,000 individuals are employed directly and indirectly by video game companies throughout 50 states. The national compensation for direct workers is US$2.9 billion, or an average wage of US$121,000.

Early settlers were introduced by Native Americans to such indigenous, non-European foods as turkey, sweet potatoes,

Early settlers were introduced by Native Americans to such indigenous, non-European foods as turkey, sweet potatoes,

The most popular sports in the U.S. are American football, basketball, baseball and ice hockey.

While most major U.S. sports such as baseball and American football have evolved out of European practices, basketball, volleyball, skateboarding, and snowboarding are American inventions, some of which have become popular worldwide. Lacrosse and surfing arose from Native American and Native Hawaiian activities that predate European contact.Liss, Howard. ''Lacrosse'' (Funk & Wagnalls, 1970) pg 13. The market for professional sports in the United States is roughly $69 billion, roughly 50% larger than that of all of Europe, the Middle East, and Africa combined.

American football is by several measures the most popular spectator sport in the United States; the National Football League (NFL) has the highest average attendance of any sports league in the world, and the Super Bowl is watched by tens of millions globally. Baseball has been regarded as the U.S. national sport since the late 19th century, with Major League Baseball being the top league. Basketball and ice hockey are the country's next two most popular professional team sports, with the top leagues being the National Basketball Association and the National Hockey League. The most-watched individual sports in the U.S. are golf and auto racing, particularly NASCAR and IndyCar.

Eight Olympic Games have taken place in the United States. The 1904 Summer Olympics in St. Louis, Missouri, were the first-ever Olympic Games held outside of Europe. The Olympic Games will be held in the U.S. for a ninth time when Los Angeles hosts the 2028 Summer Olympics. , the United States has won 2,629 medals at the Summer Olympic Games, more than any other country, and 330 in the Winter Olympic Games, the second most behind Norway. In Association football, soccer, the United States men's national soccer team, men's national soccer team qualified for United States at the FIFA World Cup, eleven World Cups and the United States women's national soccer team, women's team has United States at the FIFA Women's World Cup, won the FIFA Women's World Cup four times. The United States hosted the 1994 FIFA World Cup and will host the 2026 FIFA World Cup along with

The most popular sports in the U.S. are American football, basketball, baseball and ice hockey.

While most major U.S. sports such as baseball and American football have evolved out of European practices, basketball, volleyball, skateboarding, and snowboarding are American inventions, some of which have become popular worldwide. Lacrosse and surfing arose from Native American and Native Hawaiian activities that predate European contact.Liss, Howard. ''Lacrosse'' (Funk & Wagnalls, 1970) pg 13. The market for professional sports in the United States is roughly $69 billion, roughly 50% larger than that of all of Europe, the Middle East, and Africa combined.

American football is by several measures the most popular spectator sport in the United States; the National Football League (NFL) has the highest average attendance of any sports league in the world, and the Super Bowl is watched by tens of millions globally. Baseball has been regarded as the U.S. national sport since the late 19th century, with Major League Baseball being the top league. Basketball and ice hockey are the country's next two most popular professional team sports, with the top leagues being the National Basketball Association and the National Hockey League. The most-watched individual sports in the U.S. are golf and auto racing, particularly NASCAR and IndyCar.

Eight Olympic Games have taken place in the United States. The 1904 Summer Olympics in St. Louis, Missouri, were the first-ever Olympic Games held outside of Europe. The Olympic Games will be held in the U.S. for a ninth time when Los Angeles hosts the 2028 Summer Olympics. , the United States has won 2,629 medals at the Summer Olympic Games, more than any other country, and 330 in the Winter Olympic Games, the second most behind Norway. In Association football, soccer, the United States men's national soccer team, men's national soccer team qualified for United States at the FIFA World Cup, eleven World Cups and the United States women's national soccer team, women's team has United States at the FIFA Women's World Cup, won the FIFA Women's World Cup four times. The United States hosted the 1994 FIFA World Cup and will host the 2026 FIFA World Cup along with

/ref> and college football and College basketball, basketball attract large audiences, as the NCAA Division I men's basketball tournament, NCAA Final Four is one of the most watched sporting events.

United States

''The World Factbook''. Central Intelligence Agency.

United States

from the BBC News

Key Development Forecasts for the United States

from International Futures ; Government

Official U.S. Government Web Portal

Gateway to government sites

House

Official site of the United States House of Representatives

Senate

Official site of the United States Senate

White House

Official site of the president of the United States * [ Supreme Court] Official site of the Supreme Court of the United States ; History

Historical Documents

Collected by the National Center for Public Policy Research

Analysis by the Ontario Consultants on Religious Tolerance

Collected links to historical data ; Maps

National Atlas of the United States

Official maps from the U.S. Department of the Interior * *

Measure of America

A variety of mapped information relating to health, education, income, and demographics for the U.S. ; Photos

Photos of the USA

{{Coord, 40, -100, dim:10000000_region:region:US_type:country, name=United States of America, display=title United States Countries in North America English-speaking countries and territories Federal constitutional republics Former British colonies and protectorates in the Americas Former confederations G20 nations Member states of NATO Member states of the United Nations States and territories established in 1776 Transcontinental countries

North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere and almost entirely within the Western Hemisphere. It is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South America and the Car ...

. It consists of 50 states, a federal district

A federal district is a type of administrative division of a federation, usually under the direct control of a federal government and organized sometimes with a single municipal body. Federal districts often include capital districts, and they e ...

, five major unincorporated territories

Territories of the United States are sub-national administrative divisions overseen by the federal government of the United States. The various American territories differ from the U.S. states and tribal reservations as they are not sover ...

, nine Minor Outlying Islands, and 326 Indian reservation

An Indian reservation is an area of land held and governed by a federally recognized Native American tribal nation whose government is accountable to the United States Bureau of Indian Affairs and not to the state government in which it ...

s. The United States is also in free association with three Pacific Island

Collectively called the Pacific Islands, the islands in the Pacific Ocean are further categorized into three major island groups: Melanesia, Micronesia, and Polynesia. Depending on the context, the term ''Pacific Islands'' may refer to one of se ...

sovereign states

A sovereign state or sovereign country, is a political entity represented by one central government that has supreme legitimate authority over territory. International law defines sovereign states as having a permanent population, defined terri ...

: the Federated States of Micronesia

The Federated States of Micronesia (; abbreviated FSM) is an island country in Oceania. It consists of four states from west to east, Yap, Chuuk, Pohnpei and Kosraethat are spread across the western Pacific. Together, the states comprise a ...

, the Marshall Islands

The Marshall Islands ( mh, Ṃajeḷ), officially the Republic of the Marshall Islands ( mh, Aolepān Aorōkin Ṃajeḷ),'' () is an independent island country and microstate near the Equator in the Pacific Ocean, slightly west of the Internati ...

, and the Republic of Palau

Palau,, officially the Republic of Palau and historically ''Belau'', ''Palaos'' or ''Pelew'', is an island country and microstate in the western Pacific. The nation has approximately 340 islands and connects the western chain of the Caro ...

. It is the world's third-largest country by both land and total area. It shares land borders with Canada to its north and with Mexico to its south and has maritime borders with the Bahamas

The Bahamas (), officially the Commonwealth of The Bahamas, is an island country within the Lucayan Archipelago of the West Indies in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic. It takes up 97% of the Lucayan Archipelago's land area and is home to ...

, Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribbea ...

, Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia, Northern Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the ...

, and other nations. With a population of over 333 million, it is the most populous country in the Americas

The Americas, which are sometimes collectively called America, are a landmass comprising the totality of North and South America. The Americas make up most of the land in Earth's Western Hemisphere and comprise the New World.

Along with th ...

and the third most populous in the world. The national capital of the United States is Washington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

and its most populous city and principal financial center

A financial centre ( BE), financial center ( AE), or financial hub, is a location with a concentration of participants in banking, asset management, insurance or financial markets with venues and supporting services for these activities to t ...

is New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

.

Paleo-Americans migrated from Siberia to the North American mainland at least 12,000 years ago, and advanced cultures began to appear later on. These societies had almost completely declined when Europeans

Europeans are the focus of European ethnology, the field of anthropology related to the various ethnic groups that reside in the states of Europe. Groups may be defined by common genetic ancestry, common language, or both. Pan and Pfeil (2004) ...

arrived in North America and began colonizing it. Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It is ...

's Thirteen Colonies

The Thirteen Colonies, also known as the Thirteen British Colonies, the Thirteen American Colonies, or later as the United Colonies, were a group of Kingdom of Great Britain, British Colony, colonies on the Atlantic coast of North America. Fo ...

quarreled with the British Crown over taxation and political representation

Political representation is the activity of making citizens "present" in public policy-making processes when political actors act in the best interest of citizens. This definition of political representation is consistent with a wide variety of vie ...

, leading to the American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revolut ...

(1765–1791). After the Revolution, the United States gained independence, the first nation-state

A nation state is a political unit where the state and nation are congruent. It is a more precise concept than "country", since a country does not need to have a predominant ethnic group.

A nation, in the sense of a common ethnicity, may inc ...

founded on Enlightenment principles of liberal democracy

Liberal democracy is the combination of a liberal political ideology that operates under an indirect democratic form of government. It is characterized by elections between multiple distinct political parties, a separation of powers into diff ...

.

In the late 18th century, the U.S. began expanding across North America, gradually obtaining new territories, sometimes through war, frequently displacing Native Americans, and admitting new states. By 1848, the United States spanned the continent

A continent is any of several large landmasses. Generally identified by convention rather than any strict criteria, up to seven geographical regions are commonly regarded as continents. Ordered from largest in area to smallest, these seven ...

from east to west. The controversy surrounding the practice of slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

culminated in the secession of the Confederate States of America

The Confederate States of America (CSA), commonly referred to as the Confederate States or the Confederacy was an unrecognized breakaway republic in the Southern United States that existed from February 8, 1861, to May 9, 1865. The Confeder ...

, which fought the remaining states of the Union

Union commonly refers to:

* Trade union, an organization of workers

* Union (set theory), in mathematics, a fundamental operation on sets

Union may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

Music

* Union (band), an American rock group

** ''Un ...

during the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

(1861–1865). With the Union's victory and preservation, slavery was abolished by the Thirteenth Amendment.

By 1890, the United States had grown to become the world's largest economy, and the Spanish–American War

, partof = the Philippine Revolution, the decolonization of the Americas, and the Cuban War of Independence

, image = Collage infobox for Spanish-American War.jpg

, image_size = 300px

, caption = (clock ...

and World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

established the country as a world power

A great power is a sovereign state that is recognized as having the ability and expertise to exert its influence on a global scale. Great powers characteristically possess military and economic strength, as well as diplomatic and soft power inf ...

. After Japan's surprise attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, the U.S. entered World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

on the Allied side. The aftermath of the war left the United States and the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

as the world's two superpower

A superpower is a state with a dominant position characterized by its extensive ability to exert influence or project power on a global scale. This is done through the combined means of economic, military, technological, political and cultural s ...

s, and led to the Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because the ...

, which commenced in 1945 and ended in 1991 with the Soviet Union's dissolution. During the Cold War, both countries engaged in a struggle for ideological dominance but avoided direct military conflict. They also competed in the Space Race

The Space Race was a 20th-century competition between two Cold War rivals, the United States and the Soviet Union, to achieve superior spaceflight capability. It had its origins in the ballistic missile-based nuclear arms race between the tw ...

, which culminated in the 1969 American spaceflight in which the U.S. was the first nation to land humans on the Moon

The Moon is Earth's only natural satellite. It is the fifth largest satellite in the Solar System and the largest and most massive relative to its parent planet, with a diameter about one-quarter that of Earth (comparable to the width of ...

. Simultaneously, the civil rights movement

The civil rights movement was a nonviolent social and political movement and campaign from 1954 to 1968 in the United States to abolish legalized institutional Racial segregation in the United States, racial segregation, Racial discrimination ...

(1954–1968) led to legislation abolishing state and local Jim Crow laws

The Jim Crow laws were state and local laws enforcing racial segregation in the Southern United States. Other areas of the United States were affected by formal and informal policies of segregation as well, but many states outside the Sout ...

and other codified racial discrimination against African Americans

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American" generally denotes descendants of ens ...

. With the Soviet Union's dissolution in 1991 and the end of the Cold War, the United States emerged as the world's sole superpower. In 2001, following the September 11 attacks

The September 11 attacks, commonly known as 9/11, were four coordinated suicide terrorist attacks carried out by al-Qaeda against the United States on Tuesday, September 11, 2001. That morning, nineteen terrorists hijacked four commercia ...

, the United States became a lead member of the Global War on Terrorism

The war on terror, officially the Global War on Terrorism (GWOT), is an ongoing international counterterrorism military campaign initiated by the United States following the September 11 attacks. The main targets of the campaign are militant ...

, which included the War in Afghanistan

War in Afghanistan, Afghan war, or Afghan civil war may refer to:

*Conquest of Afghanistan by Alexander the Great (330 BC – 327 BC)

*Muslim conquests of Afghanistan (637–709)

*Conquest of Afghanistan by the Mongol Empire (13th century), see als ...

(2001–2021) and the Iraq War

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Iraq War {{Nobold, {{lang, ar, حرب العراق (Arabic) {{Nobold, {{lang, ku, شەڕی عێراق (Kurdish languages, Kurdish)

, partof = the Iraq conflict (2003–present), I ...

(2003–2011).

The United States is a federal republic

A federal republic is a federation of states with a republican form of government. At its core, the literal meaning of the word republic when used to reference a form of government means: "a country that is governed by elected representatives ...

with three separate branches of government, including a bicameral legislature

Bicameralism is a type of legislature, one divided into two separate assemblies, chambers, or houses, known as a bicameral legislature. Bicameralism is distinguished from unicameralism, in which all members deliberate and vote as a single grou ...

. It is a liberal democracy and has a market economy

A market economy is an economic system in which the decisions regarding investment, production and distribution to the consumers are guided by the price signals created by the forces of supply and demand, where all suppliers and consumers ...

. It ranks very high in international measures of quality of life

Quality of life (QOL) is defined by the World Health Organization as "an individual's perception of their position in life in the context of the culture and value systems in which they live and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards ...

, income

Income is the consumption and saving opportunity gained by an entity within a specified timeframe, which is generally expressed in monetary terms. Income is difficult to define conceptually and the definition may be different across fields. For ...

and wealth

Wealth is the abundance of Value (economics), valuable financial assets or property, physical possessions which can be converted into a form that can be used for financial transaction, transactions. This includes the core meaning as held in the ...

, economic competitiveness, human rights

Human rights are Morality, moral principles or Social norm, normsJames Nickel, with assistance from Thomas Pogge, M.B.E. Smith, and Leif Wenar, 13 December 2013, Stanford Encyclopedia of PhilosophyHuman Rights Retrieved 14 August 2014 for ce ...

, innovation

Innovation is the practical implementation of ideas that result in the introduction of new goods or services or improvement in offering goods or services. ISO TC 279 in the standard ISO 56000:2020 defines innovation as "a new or changed entity ...

, and education

Education is a purposeful activity directed at achieving certain aims, such as transmitting knowledge or fostering skills and character traits. These aims may include the development of understanding, rationality, kindness, and honesty. Va ...

; it has low levels of perceived corruption. The United States has the highest median income per person of any polity

A polity is an identifiable Politics, political entity – a group of people with a collective identity, who are organized by some form of Institutionalisation, institutionalized social relation, social relations, and have a capacity to mobilize ...

in the world. It has high levels of incarceration

Imprisonment is the restraint of a person's liberty, for any cause whatsoever, whether by authority of the government, or by a person acting without such authority. In the latter case it is "false imprisonment". Imprisonment does not necessari ...

and inequality

Inequality may refer to:

Economics

* Attention inequality, unequal distribution of attention across users, groups of people, issues in etc. in attention economy

* Economic inequality, difference in economic well-being between population groups

* ...

and lacks universal health care