Typhoid on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Typhoid fever, also known as typhoid, is a disease caused by '' Salmonella'' serotype Typhi bacteria. Symptoms vary from mild to severe, and usually begin six to 30 days after exposure. Often there is a gradual onset of a high

The Widal test is used to identify specific antibodies in the serum of people with typhoid by using antigen-antibody interactions.

In this test, the serum is mixed with a dead bacterial suspension of salmonella with specific antigens. If the patient's serum contains antibodies against those antigens, they get attached to them, forming clumps. If clumping does not occur, the test is negative. The

The Widal test is used to identify specific antibodies in the serum of people with typhoid by using antigen-antibody interactions.

In this test, the serum is mixed with a dead bacterial suspension of salmonella with specific antigens. If the patient's serum contains antibodies against those antigens, they get attached to them, forming clumps. If clumping does not occur, the test is negative. The

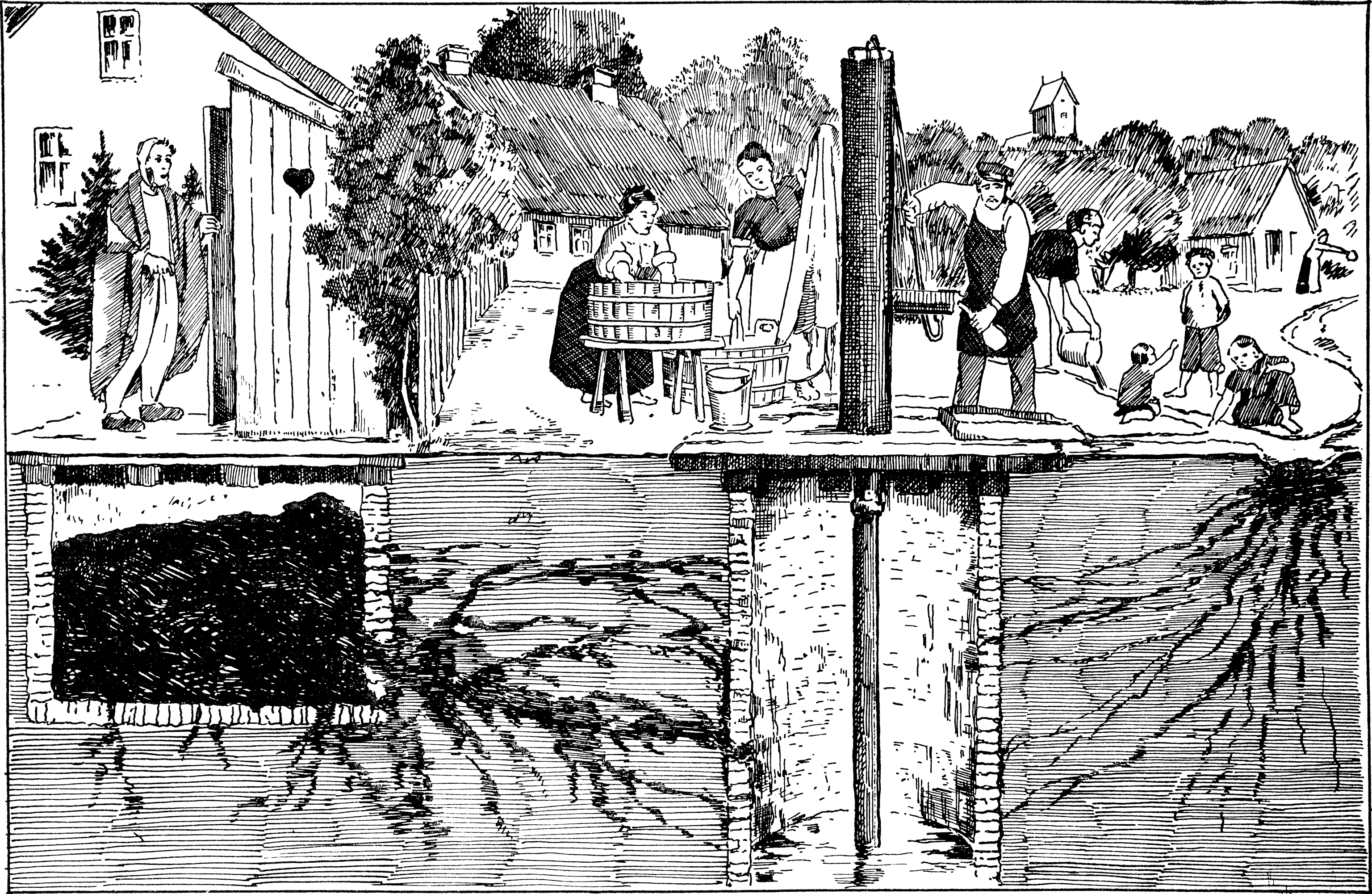

Sanitation and hygiene are important to prevent typhoid. It can spread only in environments where human feces can come into contact with food or drinking water. Careful food preparation and washing of hands are crucial to prevent typhoid. Industrialization contributed greatly to the elimination of typhoid fever, as it eliminated the public-health hazards associated with having horse manure in public streets, which led to a large number of flies, which are vectors of many pathogens, including ''Salmonella'' spp. According to statistics from the U.S.

Sanitation and hygiene are important to prevent typhoid. It can spread only in environments where human feces can come into contact with food or drinking water. Careful food preparation and washing of hands are crucial to prevent typhoid. Industrialization contributed greatly to the elimination of typhoid fever, as it eliminated the public-health hazards associated with having horse manure in public streets, which led to a large number of flies, which are vectors of many pathogens, including ''Salmonella'' spp. According to statistics from the U.S.

To help decrease rates of typhoid fever in developing nations, the World Health Organization (WHO) endorsed the use of a vaccination program starting in 1999. Vaccination has proven effective at controlling outbreaks in high-incidence areas and is also very cost-effective: prices are normally less than US$1 per dose. Because the price is low, poverty-stricken communities are more willing to take advantage of the vaccinations. Although vaccination programs for typhoid have proven effective, they alone cannot eliminate typhoid fever. Combining vaccines with public-health efforts is the only proven way to control this disease.

Since the 1990s, the WHO has recommended two typhoid fever vaccines. The ViPS vaccine is given by injection, and the Ty21a by capsules. Only people over age two are recommended to be vaccinated with the ViPS vaccine, and it requires a revaccination after 2–3 years, with a 55%–72% efficacy. The Ty21a vaccine is recommended for people five and older, lasting 5–7 years with 51%–67% efficacy. The two vaccines have proved safe and effective for epidemic disease control in multiple regions.

A version of the vaccine combined with a

To help decrease rates of typhoid fever in developing nations, the World Health Organization (WHO) endorsed the use of a vaccination program starting in 1999. Vaccination has proven effective at controlling outbreaks in high-incidence areas and is also very cost-effective: prices are normally less than US$1 per dose. Because the price is low, poverty-stricken communities are more willing to take advantage of the vaccinations. Although vaccination programs for typhoid have proven effective, they alone cannot eliminate typhoid fever. Combining vaccines with public-health efforts is the only proven way to control this disease.

Since the 1990s, the WHO has recommended two typhoid fever vaccines. The ViPS vaccine is given by injection, and the Ty21a by capsules. Only people over age two are recommended to be vaccinated with the ViPS vaccine, and it requires a revaccination after 2–3 years, with a 55%–72% efficacy. The Ty21a vaccine is recommended for people five and older, lasting 5–7 years with 51%–67% efficacy. The two vaccines have proved safe and effective for epidemic disease control in multiple regions.

A version of the vaccine combined with a

In 2000, typhoid fever caused an estimated 21.7 million illnesses and 217,000 deaths. It occurs most often in children and young adults between 5 and 19 years old. In 2013, it resulted in about 161,000 deaths – down from 181,000 in 1990. Infants, children, and adolescents in south-central and Southeast Asia have the highest rates of typhoid. Outbreaks are also often reported in sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia. In 2000, more than 90% of morbidity and mortality due to typhoid fever occurred in Asia. In the U.S., about 400 cases occur each year, 75% of which are acquired while traveling internationally.

Before the antibiotic era, the

In 2000, typhoid fever caused an estimated 21.7 million illnesses and 217,000 deaths. It occurs most often in children and young adults between 5 and 19 years old. In 2013, it resulted in about 161,000 deaths – down from 181,000 in 1990. Infants, children, and adolescents in south-central and Southeast Asia have the highest rates of typhoid. Outbreaks are also often reported in sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia. In 2000, more than 90% of morbidity and mortality due to typhoid fever occurred in Asia. In the U.S., about 400 cases occur each year, 75% of which are acquired while traveling internationally.

Before the antibiotic era, the

fever

Fever, also referred to as pyrexia, is defined as having a body temperature, temperature above the human body temperature, normal range due to an increase in the body's temperature Human body temperature#Fever, set point. There is not a single ...

over several days. This is commonly accompanied by weakness, abdominal pain

Abdominal pain, also known as a stomach ache, is a symptom

Signs and symptoms are the observed or detectable signs, and experienced symptoms of an illness, injury, or condition. A sign for example may be a higher or lower temperature than ...

, constipation

Constipation is a bowel dysfunction that makes bowel movements infrequent or hard to pass. The stool is often hard and dry. Other symptoms may include abdominal pain, bloating, and feeling as if one has not completely passed the bowel movement ...

, headache

Headache is the symptom of pain in the face, head, or neck. It can occur as a migraine, tension-type headache, or cluster headache. There is an increased risk of depression in those with severe headaches.

Headaches can occur as a result ...

s, and mild vomiting. Some people develop a skin rash with rose colored spots. In severe cases, people may experience confusion. Without treatment, symptoms may last weeks or months. Diarrhea

Diarrhea, also spelled diarrhoea, is the condition of having at least three loose, liquid, or watery bowel movements each day. It often lasts for a few days and can result in dehydration due to fluid loss. Signs of dehydration often begin wi ...

may be severe, but is uncommon. Other people may carry the bacterium without being affected, but they are still able to spread the disease. Typhoid fever is a type of enteric

The gastrointestinal tract (GI tract, digestive tract, alimentary canal) is the tract or passageway of the digestive system that leads from the mouth to the anus. The GI tract contains all the major organs of the digestive system, in humans and ...

fever, along with paratyphoid fever

Paratyphoid fever, also known simply as paratyphoid, is a bacterial infection caused by one of the three types of ''Salmonella enterica''. Symptoms usually begin 6–30 days after exposure and are the same as those of typhoid fever. Often, a grad ...

. ''S. enterica'' Typhi is believed to infect and replicate only within humans.

Typhoid is caused by the bacterium ''Salmonella enterica'' subsp. ''enterica'' serovar Typhi growing in the intestine

The gastrointestinal tract (GI tract, digestive tract, alimentary canal) is the tract or passageway of the digestive system that leads from the mouth to the anus. The GI tract contains all the major organs of the digestive system, in humans ...

s, peyers patches, mesenteric lymph nodes

The superior mesenteric lymph nodes may be divided into three principal groups:

* mesenteric lymph nodes

* ileocolic lymph nodes

* mesocolic lymph nodes

Structure

Mesenteric lymph nodes

The mesenteric lymph nodes or mesenteric glands are one of ...

, spleen

The spleen is an organ found in almost all vertebrates. Similar in structure to a large lymph node, it acts primarily as a blood filter. The word spleen comes .

, liver

The liver is a major Organ (anatomy), organ only found in vertebrates which performs many essential biological functions such as detoxification of the organism, and the Protein biosynthesis, synthesis of proteins and biochemicals necessary for ...

, gallbladder

In vertebrates, the gallbladder, also known as the cholecyst, is a small hollow organ where bile is stored and concentrated before it is released into the small intestine. In humans, the pear-shaped gallbladder lies beneath the liver, although ...

, bone marrow and blood

Blood is a body fluid in the circulatory system of humans and other vertebrates that delivers necessary substances such as nutrients and oxygen to the cells, and transports metabolic waste products away from those same cells. Blood in the c ...

. Typhoid is spread by eating or drinking food or water contaminated with the feces of an infected person. Risk factors include limited access to clean drinking water and poor sanitation

Sanitation refers to public health conditions related to clean drinking water and treatment and disposal of human excreta and sewage. Preventing human contact with feces is part of sanitation, as is hand washing with soap. Sanitation systems ...

. Those who have not yet been exposed to the pathogen and ingest contaminated drinking water or food are most at risk for developing symptoms. Only humans can be infected; there are no known animal reservoirs.

Diagnosis is by culturing and identifying ''S. enterica Typhi'' from patient samples or detecting an immune response to the pathogen from blood samples. Recently, new advances in large-scale data collection and analysis have allowed researchers to develop better diagnostics, such as detecting changing abundances of small molecules in the blood that may specifically indicate typhoid fever. Diagnostic tools in regions where typhoid is most prevalent are quite limited in their accuracy and specificity, and the time required for a proper diagnosis, the increasing spread of antibiotic resistance, and the cost of testing are also hardships for under-resourced healthcare systems.

A typhoid vaccine

Typhoid vaccines are vaccines that prevent typhoid fever. Several types are widely available: typhoid conjugate vaccine (TCV), Ty21a (a live oral vaccine) and Vi capsular polysaccharide vaccine (ViPS) (an injectable subunit vaccine). They are ab ...

can prevent about 40% to 90% of cases during the first two years. The vaccine may have some effect for up to seven years. For those at high risk or people traveling to areas where the disease is common, vaccination is recommended. Other efforts to prevent the disease include providing clean drinking water

Drinking water is water that is used in drink or food preparation; potable water is water that is safe to be used as drinking water. The amount of drinking water required to maintain good health varies, and depends on physical activity level, a ...

, good sanitation

Sanitation refers to public health conditions related to clean drinking water and treatment and disposal of human excreta and sewage. Preventing human contact with feces is part of sanitation, as is hand washing with soap. Sanitation systems ...

, and handwashing

Hand washing (or handwashing), also known as hand hygiene, is the act of cleaning one's hands with soap or handwash and water to remove viruses/bacteria/microorganisms, dirt, grease, or other harmful and unwanted substances stuck to the hands ...

. Until an infection is confirmed as cleared, the infected person should not prepare food for others. Typhoid is treated with antibiotic

An antibiotic is a type of antimicrobial substance active against bacteria. It is the most important type of antibacterial agent for fighting bacterial infections, and antibiotic medications are widely used in the treatment and prevention of ...

s such as azithromycin

Azithromycin, sold under the brand names Zithromax (in oral form) and Azasite (as an eye drop), is an antibiotic medication used for the treatment of a number of bacterial infections. This includes middle ear infections, strep throat, pneumon ...

, fluoroquinolones

A quinolone antibiotic is a member of a large group of broad-spectrum antibiotic, broad-spectrum bacteriocidals that share a bicyclic molecule, bicyclic core structure related to the substance 4-Quinolone, 4-quinolone. They are used in human and ...

, or third-generation cephalosporin

The cephalosporins (sg. ) are a class of β-lactam antibiotics originally derived from the fungus ''Acremonium'', which was previously known as ''Cephalosporium''.

Together with cephamycins, they constitute a subgroup of β-lactam antibiotics ...

s. Resistance to these antibiotics has been developing, which has made treatment more difficult.

In 2015, 12.5 million new typhoid cases were reported. The disease is most common in India. Children are most commonly affected. Typhoid decreased in the developed world

A developed country (or industrialized country, high-income country, more economically developed country (MEDC), advanced country) is a sovereign state that has a high quality of life, developed economy and advanced technological infrastruct ...

in the 1940s as a result of improved sanitation and the use of antibiotics. Every year about 400 cases are reported in the U.S. and an estimated 6,000 people have typhoid. In 2015, it resulted in about 149,000 deaths worldwide – down from 181,000 in 1990. Without treatment, the risk of death may be as high as 20%. With treatment, it is between 1% and 4%.

Typhus

Typhus, also known as typhus fever, is a group of infectious diseases that include epidemic typhus, scrub typhus, and murine typhus. Common symptoms include fever, headache, and a rash. Typically these begin one to two weeks after exposure.

...

is a different disease. Owing to their similar symptoms, they were not recognized as distinct diseases until the 1800s. "Typhoid" means "resembling typhus".

Signs and symptoms

Classically, the progression of untreated typhoid fever has three distinct stages, each lasting about a week. Over the course of these stages, the patient becomes exhausted and emaciated. * In the first week, the body temperature rises slowly, and fever fluctuations are seen with relative bradycardia ( Faget sign), malaise, headache, and cough. A bloody nose (epistaxis

A nosebleed, also known as epistaxis, is bleeding from the nose. Blood can flow down into the stomach, and cause nausea and vomiting. In more severe cases, blood may come out of both nostrils. Rarely, bleeding may be so significant that low bl ...

) is seen in a quarter of cases, and abdominal pain is also possible. A decrease in the number of circulating white blood cells (leukopenia

Leukopenia () is a decrease in the number of leukocytes (WBC). Found in the blood, they are the white blood cells, and are the body's primary defense against an infection. Thus the condition of leukopenia places individuals at increased risk of in ...

) occurs with eosinopenia

Eosinopenia is a form of agranulocytosis where the number of eosinophil granulocytes is lower than expected. Leukocytosis with eosinopenia can be a predictor of bacterial infection. It can be induced by stress reactions, Cushing's syndrome

Cu ...

and relative lymphocytosis

Lymphocytosis is an increase in the number or proportion of lymphocytes in the blood. Absolute lymphocytosis is the condition where there is an increase in the lymphocyte count beyond the normal range while relative lymphocytosis refers to the cond ...

; blood cultures are positive for ''S. enterica'' subsp. enterica serovar Typhi. The Widal test

The Widal test, developed in 1896 and named after its inventor, Georges-Fernand Widal, is an indirect agglutination test for enteric fever or undulant fever whereby bacteria causing typhoid fever is mixed with a serum containing specific antibo ...

is usually negative.

* In the second week, the person is often too tired to get up, with high fever in plateau around and bradycardia (sphygmothermic dissociation or Faget sign), classically with a dicrotic pulse

In medicine, a pulse represents the tactile arterial palpation of the cardiac cycle (heartbeat) by trained fingertips. The pulse may be palpated in any place that allows an artery to be compressed near the surface of the body, such as at the ne ...

wave. Delirium

Delirium (also known as acute confusional state) is an organically caused decline from a previous baseline of mental function that develops over a short period of time, typically hours to days. Delirium is a syndrome encompassing disturbances in ...

can occur, where the patient is often calm, but sometimes becomes agitated. This delirium has given typhoid the nickname "nervous fever". Rose spots

Rose spots are red macules 2-4 millimeters in diameter occurring in patients with enteric fever (which includes typhoid and paratyphoid). These fevers occur following infection by ''Salmonella typhi'' and ''Salmonella paratyphi'' respectively. ...

appear on the lower chest and abdomen in around a third of patients. Rhonchi

Respiratory sounds, also known as lung sounds or breath sounds, refer to the specific sounds generated by the movement of air through the respiratory system. These may be easily audible or identified through auscultation of the respiratory system ...

(rattling breathing sounds) are heard in the base of the lungs. The abdomen is distended and painful in the right lower quadrant, where a rumbling sound can be heard. Diarrhea can occur in this stage, but constipation is also common. The spleen and liver are enlarged (hepatosplenomegaly

Hepatosplenomegaly (commonly abbreviated HSM) is the simultaneous enlargement of both the liver (hepatomegaly) and the spleen (splenomegaly). Hepatosplenomegaly can occur as the result of acute viral hepatitis, infectious mononucleosis, and his ...

) and tender, and liver transaminases

Transaminases or aminotransferases are enzymes that catalyze a transamination reaction between an amino acid and an α-keto acid. They are important in the synthesis of amino acids, which form proteins.

Function and mechanism

An amino acid co ...

are elevated. The Widal test is strongly positive, with antiO and antiH antibodies. Blood cultures are sometimes still positive.

* In the third week of typhoid fever, a number of complications can occur:

** The fever is still very high and oscillates very little over 24 hours. Dehydration

In physiology, dehydration is a lack of total body water, with an accompanying disruption of metabolic processes. It occurs when free water loss exceeds free water intake, usually due to exercise, disease, or high environmental temperature. Mil ...

ensues along with malnutrition, and the patient is delirious. A third of affected people develop a macular rash on the trunk.

** Intestinal haemorrhage due to bleeding in congested Peyer's patches

Peyer's patches (or aggregated lymphoid nodules) are organized lymphoid follicles, named after the 17th-century Swiss anatomist Johann Conrad Peyer.

* Reprinted as:

* Peyer referred to Peyer's patches as ''plexus'' or ''agmina glandularum'' (c ...

occurs; this can be very serious, but is usually not fatal.

** Intestinal perforation in the distal ileum

The ileum () is the final section of the small intestine in most higher vertebrates, including mammals, reptiles, and birds. In fish, the divisions of the small intestine are not as clear and the terms posterior intestine or distal intestine ma ...

is a very serious complication and often fatal. It may occur without alarming symptoms until septicaemia

Sepsis, formerly known as septicemia (septicaemia in British English) or blood poisoning, is a life-threatening condition that arises when the body's response to infection causes injury to its own tissues and organs. This initial stage is follo ...

or diffuse peritonitis

Peritonitis is inflammation of the localized or generalized peritoneum, the lining of the inner wall of the abdomen and cover of the abdominal organs. Symptoms may include severe pain, swelling of the abdomen, fever, or weight loss. One part or ...

sets in.

** Respiratory diseases such as pneumonia

Pneumonia is an inflammatory condition of the lung primarily affecting the small air sacs known as alveoli. Symptoms typically include some combination of productive or dry cough, chest pain, fever, and difficulty breathing. The severity ...

and acute bronchitis

** Encephalitis

Encephalitis is inflammation of the brain. The severity can be variable with symptoms including reduction or alteration in consciousness, headache, fever, confusion, a stiff neck, and vomiting. Complications may include seizures, hallucinations, ...

** Neuropsychiatric symptoms (described as "muttering delirium" or "coma vigil"), with picking at bedclothes or imaginary objects.

** Metastatic abscesses, cholecystitis

Cholecystitis is inflammation of the gallbladder. Symptoms include right upper abdominal pain, pain in the right shoulder, nausea, vomiting, and occasionally fever. Often gallbladder attacks (biliary colic) precede acute cholecystitis. The pai ...

, endocarditis

Endocarditis is an inflammation of the inner layer of the heart, the endocardium. It usually involves the heart valves. Other structures that may be involved include the interventricular septum, the chordae tendineae, the mural endocardium, or the ...

, and osteitis

Osteitis is inflammation of bone. More specifically, it can refer to one of the following conditions:

* Osteomyelitis, or ''infectious osteitis'', mainly ''bacterial osteitis''

* Alveolar osteitis or "dry socket"

* Condensing osteitis (or Osteiti ...

.

** Low platelet count (thrombocytopenia

Thrombocytopenia is a condition characterized by abnormally low levels of platelets, also known as thrombocytes, in the blood. It is the most common coagulation disorder among intensive care patients and is seen in a fifth of medical patients a ...

) is sometimes seen.

Causes

Bacteria

TheGram-negative

Gram-negative bacteria are bacteria that do not retain the crystal violet stain used in the Gram staining method of bacterial differentiation. They are characterized by their cell envelopes, which are composed of a thin peptidoglycan cell wall ...

bacterium that causes typhoid fever is ''Salmonella enterica'' subsp. enterica serovar Typhi. Based on MLST subtyping scheme, the two main sequence types of the ''S.'' Typhi are ST1 and ST2, which are widespread globally. Global phylogeographical analysis showed dominance of a haplotype 58 (H58), which probably originated in India during the late 1980s and is now spreading through the world with multi-drug resistance. A more detailed genotyping scheme was reported in 2016 and is now being used widely. This scheme reclassified the nomenclature of H58 to genotype 4.3.1.

Transmission

Unlike other strains of '' Salmonella'', no animal carriers of typhoid are known. Humans are the only known carriers of the bacterium. ''S. enterica'' subsp. enterica serovar Typhi is spread by the fecal-oral route from people who are infected and fromasymptomatic carriers

An asymptomatic carrier is a person or other organism that has become infection, infected with a pathogen, but shows no signs or symptoms.

Although unaffected by the pathogen, carriers can transmit it to others or develop symptoms in later stage ...

of the bacterium. An asymptomatic human carrier is someone who is still excreting typhoid bacteria in their stool a year after the acute stage of the infection.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is made by anyblood

Blood is a body fluid in the circulatory system of humans and other vertebrates that delivers necessary substances such as nutrients and oxygen to the cells, and transports metabolic waste products away from those same cells. Blood in the c ...

, bone marrow, or stool culture

Culture () is an umbrella term which encompasses the social behavior, institutions, and norms found in human societies, as well as the knowledge, beliefs, arts, laws, customs, capabilities, and habits of the individuals in these groups.Tyl ...

s and with the Widal test (demonstration of antibodies

An antibody (Ab), also known as an immunoglobulin (Ig), is a large, Y-shaped protein used by the immune system to identify and neutralize foreign objects such as pathogenic bacteria and viruses. The antibody recognizes a unique molecule of the ...

against ''Salmonella'' antigens O-somatic and H-flagellar). In epidemics and less wealthy countries, after excluding malaria

Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects humans and other animals. Malaria causes symptoms that typically include fever, tiredness, vomiting, and headaches. In severe cases, it can cause jaundice, seizures, coma, or death. S ...

, dysentery

Dysentery (UK pronunciation: , US: ), historically known as the bloody flux, is a type of gastroenteritis that results in bloody diarrhea. Other symptoms may include fever, abdominal pain, and a feeling of incomplete defecation. Complications ...

, or pneumonia

Pneumonia is an inflammatory condition of the lung primarily affecting the small air sacs known as alveoli. Symptoms typically include some combination of productive or dry cough, chest pain, fever, and difficulty breathing. The severity ...

, a therapeutic trial time with chloramphenicol is generally undertaken while awaiting the results of the Widal test and blood and stool cultures.

Widal test

The Widal test is used to identify specific antibodies in the serum of people with typhoid by using antigen-antibody interactions.

In this test, the serum is mixed with a dead bacterial suspension of salmonella with specific antigens. If the patient's serum contains antibodies against those antigens, they get attached to them, forming clumps. If clumping does not occur, the test is negative. The

The Widal test is used to identify specific antibodies in the serum of people with typhoid by using antigen-antibody interactions.

In this test, the serum is mixed with a dead bacterial suspension of salmonella with specific antigens. If the patient's serum contains antibodies against those antigens, they get attached to them, forming clumps. If clumping does not occur, the test is negative. The Widal test

The Widal test, developed in 1896 and named after its inventor, Georges-Fernand Widal, is an indirect agglutination test for enteric fever or undulant fever whereby bacteria causing typhoid fever is mixed with a serum containing specific antibo ...

is time-consuming and prone to significant false positives. It may also be falsely negative in recently infected people. But unlike the Typhidot test, the Widal test quantifies the specimen with titres.

Rapid diagnostic tests

Rapid diagnostic tests such as Tubex, Typhidot, and Test-It have shown moderate diagnostic accuracy.Typhidot

Typhidot is based on the presence of specific IgM and IgG antibodies to a specific 50 Kd OMP antigen. This test is carried out on a cellulose nitrate membrane where a specific ''S. typhi'' outer membrane protein is attached as fixed test lines. It separately identifies IgM and IgG antibodies. IgM shows recent infection; IgG signifies remote infection. The sample pad of this kit contains colloidal gold-anti-human IgG or gold-anti-human IgM. If the sample contains IgG and IgM antibodies against those antigens, they will react and turn red. The typhidot test becomes positive within 2–3 days of infection. Two colored bands indicate a positive test. A single control band indicates a negative test. A single first fixed line or no band at all indicates an invalid test. Typhidot's biggest limitation is that it is not quantitative, just positive or negative.Tubex test

The Tubex test contains two types of particles: brown magnetic particles coated with antigen and blue indicator particles coated with O9 antibody. During the test, if antibodies are present in the serum, they will attach to the brown magnetic particles and settle at the base, while the blue indicator particles remain in the solution, producing a blue color, which means the test is positive. If the serum does not have an antibody in it, the blue particles attach to the brown particles and settle at the bottom, producing a colorless solution, which means the test is negative.Prevention

Sanitation and hygiene are important to prevent typhoid. It can spread only in environments where human feces can come into contact with food or drinking water. Careful food preparation and washing of hands are crucial to prevent typhoid. Industrialization contributed greatly to the elimination of typhoid fever, as it eliminated the public-health hazards associated with having horse manure in public streets, which led to a large number of flies, which are vectors of many pathogens, including ''Salmonella'' spp. According to statistics from the U.S.

Sanitation and hygiene are important to prevent typhoid. It can spread only in environments where human feces can come into contact with food or drinking water. Careful food preparation and washing of hands are crucial to prevent typhoid. Industrialization contributed greatly to the elimination of typhoid fever, as it eliminated the public-health hazards associated with having horse manure in public streets, which led to a large number of flies, which are vectors of many pathogens, including ''Salmonella'' spp. According to statistics from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) is the national public health agency of the United States. It is a United States federal agency, under the Department of Health and Human Services, and is headquartered in Atlanta, Georgi ...

, the chlorination Chlorination may refer to:

* Chlorination reaction

In chemistry, halogenation is a chemical reaction that entails the introduction of one or more halogens into a compound. Halide-containing compounds are pervasive, making this type of transform ...

of drinking water has led to dramatic decreases in the transmission of typhoid fever.

Vaccination

Twotyphoid vaccine

Typhoid vaccines are vaccines that prevent typhoid fever. Several types are widely available: typhoid conjugate vaccine (TCV), Ty21a (a live oral vaccine) and Vi capsular polysaccharide vaccine (ViPS) (an injectable subunit vaccine). They are ab ...

s are licensed for use for the prevention of typhoid: the live, oral Ty21a vaccine (sold as Vivotif by Crucell Switzerland AG) and the injectable typhoid polysaccharide vaccine (sold as Typhim Vi by Sanofi Pasteur and Typherix by GlaxoSmithKline). Both are efficacious and recommended for travelers to areas where typhoid is endemic. Boosters are recommended every five years for the oral vaccine and every two years for the injectable form. An older, killed whole-cell vaccine is still used in countries where the newer preparations are not available, but this vaccine is no longer recommended for use because it has more side effects (mainly pain and inflammation at the site of the injection).

hepatitis A

Hepatitis A is an infectious disease of the liver caused by ''Hepatovirus A'' (HAV); it is a type of viral hepatitis. Many cases have few or no symptoms, especially in the young. The time between infection and symptoms, in those who develop them ...

vaccine is also available.

Results of a phase 3 trial of typhoid conjugate vaccine (TCV) in December 2019 reported 81% fewer cases among children.

Treatment

Oral rehydration therapy

The rediscovery oforal rehydration therapy

Oral rehydration therapy (ORT) is a type of fluid replacement used to prevent and treat dehydration, especially due to diarrhea. It involves drinking water with modest amounts of sugar and salts, specifically sodium and potassium. Oral rehydrat ...

in the 1960s provided a simple way to prevent many of the deaths of diarrhea

Diarrhea, also spelled diarrhoea, is the condition of having at least three loose, liquid, or watery bowel movements each day. It often lasts for a few days and can result in dehydration due to fluid loss. Signs of dehydration often begin wi ...

l diseases in general.

Antibiotics

Where resistance is uncommon, the treatment of choice is afluoroquinolone

A quinolone antibiotic is a member of a large group of broad-spectrum bacteriocidals that share a bicyclic core structure related to the substance 4-quinolone. They are used in human and veterinary medicine to treat bacterial infections, as wel ...

such as ciprofloxacin

Ciprofloxacin is a fluoroquinolone antibiotic used to treat a number of bacterial infections. This includes bone and joint infections, intra abdominal infections, certain types of infectious diarrhea, respiratory tract infections, skin inf ...

. Otherwise, a third-generation cephalosporin such as ceftriaxone

Ceftriaxone, sold under the brand name Rocephin, is a third-generation cephalosporin antibiotic used for the treatment of a number of bacterial infections. These include middle ear infections, endocarditis, meningitis, pneumonia, bone and joint ...

or cefotaxime

Cefotaxime is an antibiotic used to treat a number of bacterial infections in human, other animals and plant tissue culture. Specifically in humans it is used to treat joint infections, pelvic inflammatory disease, meningitis, pneumonia, urin ...

is the first choice. Cefixime

Cefixime, sold under the brand name Suprax among others, is an antibiotic medication used to treat a number of bacterial infections. These infections include otitis media, strep throat, pneumonia, urinary tract infections, gonorrhea, and Lyme ...

is a suitable oral alternative.

Properly treated, typhoid fever is not fatal in most cases. Antibiotics such as ampicillin

Ampicillin is an antibiotic used to prevent and treat a number of bacterial infections, such as respiratory tract infections, urinary tract infections, meningitis, salmonellosis, and endocarditis. It may also be used to prevent group B strepto ...

, chloramphenicol, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole

Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, sold under the brand name Bactrim among others, is a fixed-dose combination antibiotic medication used to treat a variety of bacterial infections. It consists of one part trimethoprim to five parts sulfamethoxaz ...

, amoxicillin

Amoxicillin is an antibiotic medication used to treat a number of bacterial infections. These include middle ear infection, strep throat, pneumonia, skin infections, and urinary tract infections among others. It is taken by mouth, or less c ...

, and ciprofloxacin have been commonly used to treat it. Treatment with antibiotics reduces the case-fatality rate to about 1%.

Without treatment, some patients develop sustained fever, bradycardia, hepatosplenomegaly, abdominal symptoms, and occasionally pneumonia. In white-skinned patients, pink spots, which fade on pressure, appear on the skin of the trunk in up to 20% of cases. In the third week, untreated cases may develop gastrointestinal and cerebral complications, which may prove fatal in 10%–20% of cases. The highest case fatality rates are reported in children under 4. Around 2%–5% of those who contract typhoid fever become chronic carriers, as bacteria persist in the biliary tract after symptoms have resolved.

Surgery

Surgery is usually indicated ifintestinal perforation

Gastrointestinal perforation, also known as ruptured bowel, is a hole in the wall of part of the gastrointestinal tract. The gastrointestinal tract includes the esophagus, stomach, small intestine, and large intestine. Symptoms include severe ab ...

occurs. One study found a 30-day mortality rate of 9% (8/88), and surgical site infections at 67% (59/88), with the disease burden borne predominantly by low-resource countries.

For surgical treatment, most surgeons prefer simple closure of the perforation with drainage of the peritoneum

The peritoneum is the serous membrane forming the lining of the abdominal cavity or coelom in amniotes and some invertebrates, such as annelids. It covers most of the intra-abdominal (or coelomic) organs, and is composed of a layer of mesoth ...

. Small-bowel resection is indicated for patients with multiple perforations. If antibiotic treatment fails to eradicate the hepatobiliary

The biliary tract, (biliary tree or biliary system) refers to the liver, gallbladder and bile ducts, and how they work together to make, store and secrete bile. Bile consists of water, electrolytes, bile acids, cholesterol, phospholipids and ...

carriage, the gallbladder

In vertebrates, the gallbladder, also known as the cholecyst, is a small hollow organ where bile is stored and concentrated before it is released into the small intestine. In humans, the pear-shaped gallbladder lies beneath the liver, although ...

should be resected. Cholecystectomy is sometimes successful, especially in patients with gallstone

A gallstone is a stone formed within the gallbladder from precipitated bile components. The term cholelithiasis may refer to the presence of gallstones or to any disease caused by gallstones, and choledocholithiasis refers to the presence of mi ...

s, but is not always successful in eradicating the carrier state because of persisting hepatic

The liver is a major organ only found in vertebrates which performs many essential biological functions such as detoxification of the organism, and the synthesis of proteins and biochemicals necessary for digestion and growth. In humans, it i ...

infection.

Resistance

As resistance to ampicillin, chloramphenicol, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, andstreptomycin

Streptomycin is an antibiotic medication used to treat a number of bacterial infections, including tuberculosis, ''Mycobacterium avium'' complex, endocarditis, brucellosis, ''Burkholderia'' infection, plague, tularemia, and rat bite fever. Fo ...

is now common, these agents are no longer used as first–line treatment of typhoid fever. Typhoid resistant to these agents is known as multidrug-resistant typhoid.

Ciprofloxacin resistance is an increasing problem, especially in the Indian subcontinent

The Indian subcontinent is a list of the physiographic regions of the world, physiographical region in United Nations geoscheme for Asia#Southern Asia, Southern Asia. It is situated on the Indian Plate, projecting southwards into the Indian O ...

and Southeast Asia

Southeast Asia, also spelled South East Asia and South-East Asia, and also known as Southeastern Asia, South-eastern Asia or SEA, is the geographical United Nations geoscheme for Asia#South-eastern Asia, south-eastern region of Asia, consistin ...

. Many centres are shifting from ciprofloxacin to ceftriaxone

Ceftriaxone, sold under the brand name Rocephin, is a third-generation cephalosporin antibiotic used for the treatment of a number of bacterial infections. These include middle ear infections, endocarditis, meningitis, pneumonia, bone and joint ...

as the first line for treating suspected typhoid originating in South America, India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Thailand, or Vietnam. Also, it has been suggested that azithromycin

Azithromycin, sold under the brand names Zithromax (in oral form) and Azasite (as an eye drop), is an antibiotic medication used for the treatment of a number of bacterial infections. This includes middle ear infections, strep throat, pneumon ...

is better at treating resistant typhoid than both fluoroquinolone drugs and ceftriaxone. Azithromycin can be taken by mouth and is less expensive than ceftriaxone, which is given by injection.

A separate problem exists with laboratory testing for reduced susceptibility to ciprofloxacin; current recommendations are that isolates should be tested simultaneously against ciprofloxacin (CIP) and against nalidixic acid

Nalidixic acid (tradenames Nevigramon, NegGram, Wintomylon and WIN 18,320) is the first of the synthetic quinolone antibiotics.

In a technical sense, it is a naphthyridone, not a quinolone: its ring structure is a 1,8-naphthyridine nucleus that ...

(NAL), that isolates sensitive to both CIP and NAL should be reported as "sensitive to ciprofloxacin", and that isolates sensitive to CIP but not to NAL should be reported as "reduced sensitivity to ciprofloxacin". But an analysis of 271 isolates found that around 18% of isolates with a reduced susceptibility to fluoroquinolones

A quinolone antibiotic is a member of a large group of broad-spectrum antibiotic, broad-spectrum bacteriocidals that share a bicyclic molecule, bicyclic core structure related to the substance 4-Quinolone, 4-quinolone. They are used in human and ...

, the class which CIP belongs ( MIC 0.125–1.0 mg/L), would not be detected by this method.

Epidemiology

In 2000, typhoid fever caused an estimated 21.7 million illnesses and 217,000 deaths. It occurs most often in children and young adults between 5 and 19 years old. In 2013, it resulted in about 161,000 deaths – down from 181,000 in 1990. Infants, children, and adolescents in south-central and Southeast Asia have the highest rates of typhoid. Outbreaks are also often reported in sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia. In 2000, more than 90% of morbidity and mortality due to typhoid fever occurred in Asia. In the U.S., about 400 cases occur each year, 75% of which are acquired while traveling internationally.

Before the antibiotic era, the

In 2000, typhoid fever caused an estimated 21.7 million illnesses and 217,000 deaths. It occurs most often in children and young adults between 5 and 19 years old. In 2013, it resulted in about 161,000 deaths – down from 181,000 in 1990. Infants, children, and adolescents in south-central and Southeast Asia have the highest rates of typhoid. Outbreaks are also often reported in sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia. In 2000, more than 90% of morbidity and mortality due to typhoid fever occurred in Asia. In the U.S., about 400 cases occur each year, 75% of which are acquired while traveling internationally.

Before the antibiotic era, the case fatality rate

In epidemiology, case fatality rate (CFR) – or sometimes more accurately case-fatality risk – is the proportion of people diagnosed with a certain disease, who end up dying of it. Unlike a disease's mortality rate, the CFR does not take int ...

of typhoid fever was 10%–20%. Today, with prompt treatment, it is less than 1%, but 3%–5% of people who are infected develop a chronic infection in the gall bladder. Since ''S. enterica'' subsp. enterica serovar Typhi is human-restricted, these chronic carriers become the crucial reservoir, which can persist for decades for further spread of the disease, further complicating its identification and treatment. Lately, the study of ''S. enterica'' subsp. enterica serovar Typhi associated with a large outbreak and a carrier at the genome level provides new insight into the pathogenesis of the pathogen.

In industrialized nations, water sanitation and food handling improvements have reduced the number of typhoid cases. Developing nations, such as those in parts of Asia and Africa, have the highest rates. These areas lack access to clean water, proper sanitation systems, and proper health-care facilities. In these areas, such access to basic public-health needs is not expected in the near future.

In 2004–2005 an outbreak in the Democratic Republic of Congo

The Democratic Republic of the Congo (french: République démocratique du Congo (RDC), colloquially "La RDC" ), informally Congo-Kinshasa, DR Congo, the DRC, the DROC, or the Congo, and formerly and also colloquially Zaire, is a country in ...

resulted in more than 42,000 cases and 214 deaths. Since November 2016, Pakistan

Pakistan ( ur, ), officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan ( ur, , label=none), is a country in South Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, fifth-most populous country, with a population of almost 24 ...

has had an outbreak of extensively drug-resistant (XDR) typhoid fever.

In Europe, a report based on data for 2017 retrieved from The European Surveillance System (TESSy) on the distribution of confirmed typhoid and paratyphoid fever

Paratyphoid fever, also known simply as paratyphoid, is a bacterial infection caused by one of the three types of ''Salmonella enterica''. Symptoms usually begin 6–30 days after exposure and are the same as those of typhoid fever. Often, a grad ...

cases found that 22 EU/EEA countries reported a total of 1,098 cases, 90.9% of which were travel-related, mainly acquired during travel to South Asia

South Asia is the southern subregion of Asia, which is defined in both geographical and ethno-cultural terms. The region consists of the countries of Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka.;;;;;;;; ...

.

History

Early descriptions

Theplague of Athens

The Plague of Athens ( grc, Λοιμὸς τῶν Ἀθηνῶν}, ) was an epidemic that devastated the city-state of Athens in ancient Greece during the second year (430 BC) of the Peloponnesian War when an Athenian victory still seemed within r ...

, during the Peloponnesian War

The Peloponnesian War (431–404 BC) was an ancient Greek war fought between Athens and Sparta and their respective allies for the hegemony of the Greek world. The war remained undecided for a long time until the decisive intervention of th ...

, was most likely an outbreak of typhoid fever. During the war, Athenians retreated into a walled-in city to escape attack from the Sparta

Sparta ( Doric Greek: Σπάρτα, ''Spártā''; Attic Greek: Σπάρτη, ''Spártē'') was a prominent city-state in Laconia, in ancient Greece. In antiquity, the city-state was known as Lacedaemon (, ), while the name Sparta referre ...

ns. This massive influx of humans into a concentrated space overwhelmed the water supply and waste infrastructure, likely leading to unsanitary conditions as fresh water became harder to obtain and waste became more difficult to collect and remove beyond the city walls. In 2006, examining the remains for a mass burial site from Athens from around the time of the plague (~430 B.C.) revealed that fragments of DNA similar to modern day ''S.'' Typhi DNA were detected, whereas ''Yersinia pestis

''Yersinia pestis'' (''Y. pestis''; formerly '' Pasteurella pestis'') is a gram-negative, non-motile, coccobacillus bacterium without spores that is related to both ''Yersinia pseudotuberculosis'' and ''Yersinia enterocolitica''. It is a facult ...

'' (plague), ''Rickettsia prowazekii

''Rickettsia prowazekii'' is a species of gram-negative, alphaproteobacteria, obligate intracellular parasitic, aerobic bacillus bacteria that is the etiologic agent of epidemic typhus, transmitted in the feces of lice. In North America, the ...

'' (typhus), ''Mycobacterium tuberculosis

''Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (M. tb) is a species of pathogenic bacteria in the family Mycobacteriaceae and the causative agent of tuberculosis. First discovered in 1882 by Robert Koch, ''M. tuberculosis'' has an unusual, waxy coating on its c ...

'', cowpox virus

Cowpox is an infectious disease caused by the ''cowpox virus'' (CPXV). It presents with large vesicle (dermatology), blisters in the skin, a fever and lymphadenopathy, swollen glands, historically typically following contact with an infected cow, ...

, and ''Bartonella henselae

''Bartonella henselae'', formerly ''Rochalimæa henselae'', is a bacterium that is the causative agent of cat-scratch disease (bartonellosis).

''Bartonella henselae'' is a member of the genus ''Bartonella'', one of the most common types of bacter ...

'' were not detected in any of the remains tested.

It is possible that the Roman emperor Augustus Caesar had either a liver abscess or typhoid fever, and survived by using ice baths and cold compresses as a means of treatment for his fever. There is a statue of the Greek physician, Antonius Musa

Antonius Musa (Greek ) was a Greek botanist and the Roman Emperor Augustus's physician; Antonius was a freedman who received freeborn status along with other honours. In the year 23 BC, when Augustus was seriously ill, Musa cured the illness wi ...

, who treated his fever.

Definition and evidence of transmission

The French doctors Pierre-Fidele Bretonneau and Pierre-Charles-Alexandre Louis are credited with describing typhoid fever as a specific disease, unique fromtyphus

Typhus, also known as typhus fever, is a group of infectious diseases that include epidemic typhus, scrub typhus, and murine typhus. Common symptoms include fever, headache, and a rash. Typically these begin one to two weeks after exposure.

...

. Both doctors performed autopsies on individuals who died in Paris due to fever – and indicated that many had lesions on the Peyer's patch

Peyer's patches (or aggregated lymphoid nodules) are organized lymphoid follicles, named after the 17th-century Swiss anatomist Johann Conrad Peyer.

* Reprinted as:

* Peyer referred to Peyer's patches as ''plexus'' or ''agmina glandularum'' (c ...

es which correlated with distinct symptoms before death. British medics were skeptical of the differentiation between typhoid and typhus because both were endemic to Britain at that time. However, in France only typhoid was present circulating in the population. Pierre-Charlles-Alexandre Louis also performed case studies and statistical analysis to demonstrate that typhoid was contagious - and that persons who already had the disease seemed to be protected. Afterward, several American doctors confirmed these findings, and then Sir William Jenner convinced any remaining skeptics that typhoid is a specific disease recognizable by lesions in the Peyer's patches by examining sixty six autopsies from fever patients and concluding that the symptoms of headaches, diarrhea, rash spots, and abdominal pain were only present in patients which then had intestinal lesions after death; which solidified the association of the disease with the intestinal tract and gave the first clue to the route of transmission.

In 1847 William Budd

William Budd (14 September 1811 – 9 January 1880) was an English physician and epidemiologist known for recognizing that infectious diseases were contagious. He recognized that the "poisons" involved in infectious diseases multiplied in the int ...

learned of an epidemic of typhoid fever in Clifton, and identified that all 13 of 34 residents who had contracted the disease drew their drinking water from the same well. Notably, this observation was two years prior to John Snow discovering the route of contaminated water as the cause for a cholera

Cholera is an infection of the small intestine by some strains of the bacterium ''Vibrio cholerae''. Symptoms may range from none, to mild, to severe. The classic symptom is large amounts of watery diarrhea that lasts a few days. Vomiting and ...

outbreak. Budd later became health officer of Bristol

Bristol () is a city, ceremonial county and unitary authority in England. Situated on the River Avon, it is bordered by the ceremonial counties of Gloucestershire to the north and Somerset to the south. Bristol is the most populous city in ...

and ensured a clean water supply, and documented further evidence of typhoid as a water-borne illness throughout his career.

Cause

Polish scientist Tadeusz Browicz described a short bacillus in the organs and feces of typhoid victims in 1874. Browicz was able to isolate and grow the bacilli but did not go as far as to insinuate or prove that they caused the disease. In April 1880, three months prior to Eberth's publication,Edwin Klebs

Theodor Albrecht Edwin Klebs (6 February 1834 – 23 October 1913) was a German-Swiss microbiologist. He is mainly known for his work on infectious diseases. His works paved the way for the beginning of modern bacteriology, and inspired Louis ...

described short and filamentous bacilli in the Peyer's patch

Peyer's patches (or aggregated lymphoid nodules) are organized lymphoid follicles, named after the 17th-century Swiss anatomist Johann Conrad Peyer.

* Reprinted as:

* Peyer referred to Peyer's patches as ''plexus'' or ''agmina glandularum'' (c ...

es in typhoid victims. The bacterium's role in disease was speculated but not confirmed.

In 1880, Karl Joseph Eberth described a bacillus that he suspected was the cause of typhoid. Eberth is given credit for discovering the bacterium definitively by successfully isolating the same bacterium from 18 of 40 typhoid victims and failing to discover the bacterium present in any "control" victims of other diseases. In 1884, pathologist Georg Theodor August Gaffky (1850–1918) confirmed Eberth's findings. Gaffky isolated the same bacterium as Eberth from the spleen of a typhoid victim, and was able to grow the bacterium on solid media. The organism was given names such as Eberth's bacillus, ''Eberthella'' Typhi, and Gaffky-Eberth bacillus. Today, the bacillus that causes typhoid fever goes by the scientific name ''Salmonella enterica

''Salmonella enterica'' (formerly ''Salmonella choleraesuis'') is a rod-headed, flagellate, facultative anaerobic, Gram-negative bacterium and a species of the genus ''Salmonella''. A number of its serovars are serious human pathogens.

Epidemi ...

'' serovar Typhi.

Chlorination of water

Most developed countries had declining rates of typhoid fever throughout the first half of the 20th century due to vaccinations and advances in public sanitation and hygiene. In 1893 attempts were made to chlorinate the water supply inHamburg

(male), (female) en, Hamburger(s),

Hamburgian(s)

, timezone1 = Central (CET)

, utc_offset1 = +1

, timezone1_DST = Central (CEST)

, utc_offset1_DST = +2

, postal ...

, Germany and in 1897 Maidstone

Maidstone is the largest Town status in the United Kingdom, town in Kent, England, of which it is the county town. Maidstone is historically important and lies 32 miles (51 km) east-south-east of London. The River Medway runs through the c ...

, England, was the first town to have its entire water supply chlorinated. In 1905, following an outbreak of typhoid fever, the City of Lincoln, England

Lincoln () is a cathedral city, a non-metropolitan district, and the county town of Lincolnshire, England. In the 2021 Census, the Lincoln district had a population of 103,813. The 2011 census gave the Lincoln Urban Area, urban area of Lincoln, ...

, instituted permanent water chlorination. The first permanent disinfection of drinking water in the US was made in 1908 to the Jersey City, New Jersey

Jersey City is the second-most populous city in the U.S. state of New Jersey, after Newark.John L. Leal. The

There were several occurrences of milk delivery men spreading typhoid fever throughout the communities they served. Although typhoid is not spread through milk itself, there were several examples of milk distributors in many locations watering their milk down with contaminated water, or cleaning the glass bottles the milk was placed in with contaminated water.

There were several occurrences of milk delivery men spreading typhoid fever throughout the communities they served. Although typhoid is not spread through milk itself, there were several examples of milk distributors in many locations watering their milk down with contaminated water, or cleaning the glass bottles the milk was placed in with contaminated water.  Today, typhoid carriers exist all over the world, but the highest incidence of

Today, typhoid carriers exist all over the world, but the highest incidence of

British bacteriologist Almroth Edward Wright first developed an effective typhoid vaccine at the Army Medical School in

British bacteriologist Almroth Edward Wright first developed an effective typhoid vaccine at the Army Medical School in

chlorination Chlorination may refer to:

* Chlorination reaction

In chemistry, halogenation is a chemical reaction that entails the introduction of one or more halogens into a compound. Halide-containing compounds are pervasive, making this type of transform ...

facility was designed by George W. Fuller

George Warren Fuller (December 21, 1868 – June 15, 1934) was an American sanitary engineer who was also trained in bacteriology and chemistry. His career extended from 1890 to 1934 and he was responsible for important innovations in water and ...

.

Outbreaks in traveling military groups led to the creation of the Lyster bag in 1915; a bag with a faucet which can be hung from a tree or pole, filled with water, and comes with a chlorination tablet to drop into the water. The Lyster bag was essential for the survival of American soldiers in the Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (also known by #Names, other names) was a conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. It was the second of the Indochina Wars and was officially fought between North Vie ...

.

Direct transmission and carriers

There were several occurrences of milk delivery men spreading typhoid fever throughout the communities they served. Although typhoid is not spread through milk itself, there were several examples of milk distributors in many locations watering their milk down with contaminated water, or cleaning the glass bottles the milk was placed in with contaminated water.

There were several occurrences of milk delivery men spreading typhoid fever throughout the communities they served. Although typhoid is not spread through milk itself, there were several examples of milk distributors in many locations watering their milk down with contaminated water, or cleaning the glass bottles the milk was placed in with contaminated water. Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

had two such cases around the turn of the 20th century. In 1899 there were 24 cases of typhoid traced to a single milkman, whose wife had died of typhoid fever a week before the outbreak. In 1908, J.J. Fallon, who was also a milkman, died of typhoid fever. Following his death and confirmation of the typhoid fever diagnosis, the city conducted an investigation of typhoid symptoms and cases along his route and found evidence of a significant outbreak. A month after the outbreak was first reported, the ''Boston Globe'' published a short statement declaring the outbreak over, stating " Jamaica Plain there is a slight increase, the total being 272 cases. Throughout the city there is a total of 348 cases." There was at least one death reported during this outbreak: Mrs. Sophia S. Engstrom, aged 46. Typhoid continued to ravage the Jamaica Plain

Jamaica Plain is a neighborhood of in the City of Boston, Massachusetts, United States. Settled by Puritans seeking farmland to the south, it was originally part of the former Town of Roxbury, now also a part of the City of Boston. The commun ...

neighborhood in particular throughout 1908, and several more people were reported dead due to typhoid fever, although these cases were not explicitly linked to the outbreak. The Jamaica Plain neighborhood at that time was home to many working-class and poor immigrants, mostly from Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel (Grea ...

.

The most notorious carrier of typhoid fever, but by no means the most destructive, was Mary Mallon

Mary Mallon (September 23, 1869 – November 11, 1938), commonly known as Typhoid Mary, was an Irish-born American cook believed to have infected between 51 and 122 people with typhoid fever. The infections caused three confirmed deaths, ...

, known as Typhoid Mary. Although other cases of human-to-human spread of typhoid were known at the time, the concept of an asymptomatic carrier, who was able to transmit disease, had only been hypothesized and not yet identified or proven. Mary Mallon became the first known example of an asymptomatic carrier of an infectious disease, making typhoid fever the first known disease being transmissible through asymptomatic hosts. The cases and deaths caused by Mallon were mainly upper-class families in New York City. At the time of Mallon's tenure as a personal cook for upper-class families, New York City reported 3,000 to 4,500 cases of typhoid fever annually. In the summer of 1906 two daughters of a wealthy family and maids working in their home became ill with typhoid fever. After investigating their home water sources and ruling out water contamination, the family hired civil engineer George Soper

George Albert Soper II (2 February 1870 – 17 June 1948) was an American sanitation engineer. He was best known for discovering Mary Mallon, also known as Typhoid Mary, an asymptomatic carrier of typhoid fever.

Biography

Soper was the son of ...

to conduct an investigation of the possible source of typhoid fever in the home. Soper described himself as an "epidemic fighter". His investigation ruled out many sources of food, and led him to question if the cook the family hired just prior to their household outbreak, Mallon, was the source. Since she had already left and begun employment elsewhere, he proceeded to track her down in order to obtain a stool sample. When he was able to finally meet Mallon in person he described her by saying "Mary had a good figure and might have been called athletic had she not been a little too heavy." In recounts of Soper's pursuit of Mallon, his only remorse appears to be that he was not given enough credit for his relentless pursuit and publication of her personal identifying information, stating that the media "rob me of whatever credit belongs to the discovery of the first typhoid fever carrier to be found in America." Ultimately, 51 cases and 3 deaths were suspected to be caused by Mallon.

In 1924 the city of Portland, Oregon

Portland (, ) is a port city in the Pacific Northwest and the largest city in the U.S. state of Oregon. Situated at the confluence of the Willamette and Columbia rivers, Portland is the county seat of Multnomah County, the most populous co ...

, experienced an outbreak of typhoid fever, consisting of 26 cases and 5 deaths, all deaths due to intestinal hemorrhage

Bleeding, hemorrhage, haemorrhage or blood loss, is blood escaping from the circulatory system from damaged blood vessels. Bleeding can occur internally, or externally either through a natural opening such as the mouth, nose, ear, urethra, v ...

. All cases were concluded to be due to a single milk farm worker, who was shedding large amounts of the typhoid pathogen in his urine. Misidentification of the disease, due to inaccurate Widal test results, delayed identification of the carrier and proper treatment. Ultimately, it took four samplings of different secretions from all of the dairy workers in order to successfully identify the carrier. Upon discovery, the dairy worker was forcibly quarantined for seven weeks, and regular samples were taken, most of the time the stool samples yielding no typhoid and often the urine yielding the pathogen. The carrier was reported as being 72 years old and appearing in excellent health with no symptoms. Pharmaceutical treatment decreased the amount of bacteria secreted, however, the infection was never fully cleared from the urine, and the carrier was released "under orders never again to engage in the handling of foods for human consumption." At the time of release, the authors noted "for more than fifty years he has earned his living chiefly by milking cows and knows little of other forms of labor, it must be expected that the closest surveillance will be necessary to make certain that he does not again engage in this occupation."

Overall, in the early 20th century the medical profession began to identify carriers of the disease, and evidence of transmission independent of water contamination. In a 1933 American Medical Association

The American Medical Association (AMA) is a professional association and lobbying group of physicians and medical students. Founded in 1847, it is headquartered in Chicago, Illinois. Membership was approximately 240,000 in 2016.

The AMA's state ...

publication, physicians' treatment of asymptomatic carriers is best summarized by the opening line "Carriers of typhoid bacilli are a menace". Within the same publication, the first official estimate of typhoid carriers is given: 2 to 5% of all typhoid patients, and distinguished between temporary carriers and chronic carriers. The authors further estimate that there are four to five chronic female carriers to every one male carrier, although offered no data to explain this assertion of a gender difference in the rate of typhoid carriers. As far as treatment, the authors suggest: "When recognized, carriers must be instructed as to the disposal of excreta as well as to the importance of personal cleanliness. They should be forbidden to handle food or drink intended for others, and their movements and whereabouts must be reported to the public health officers".

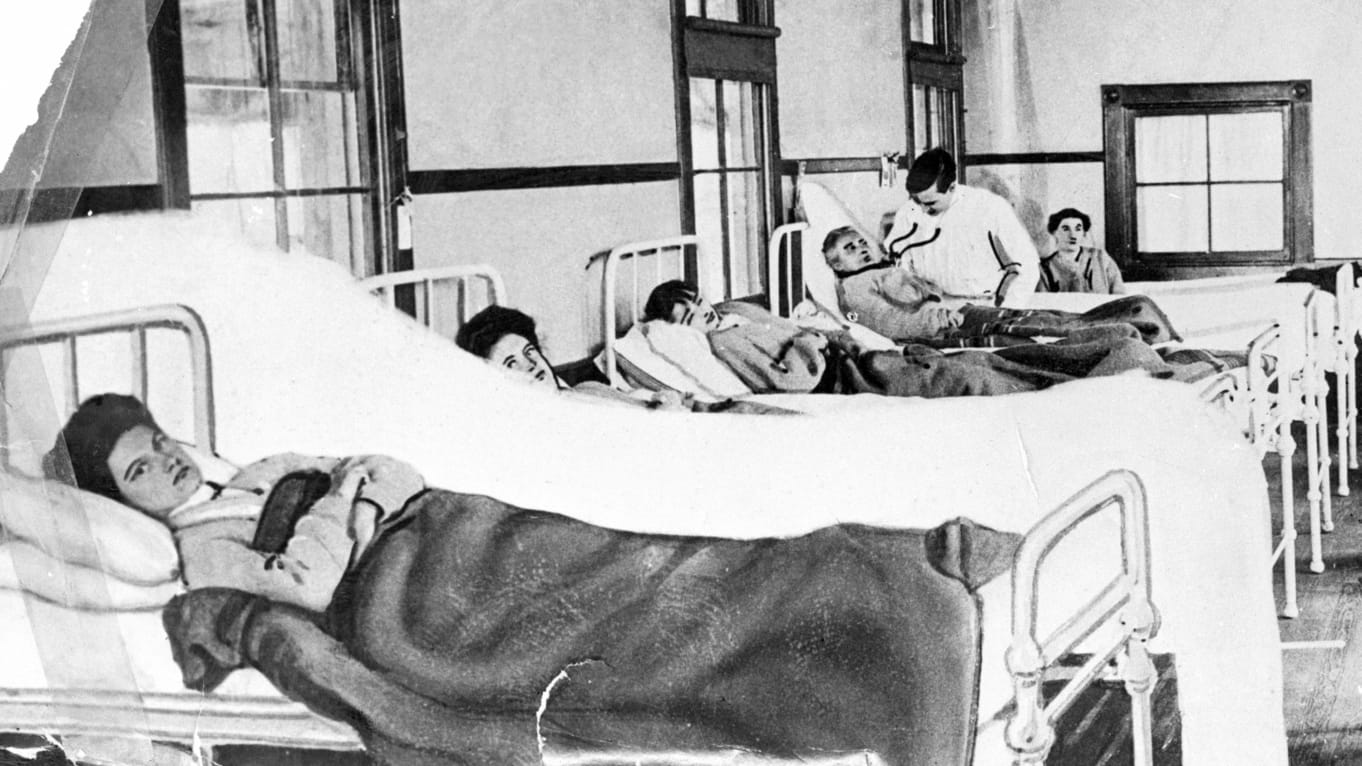

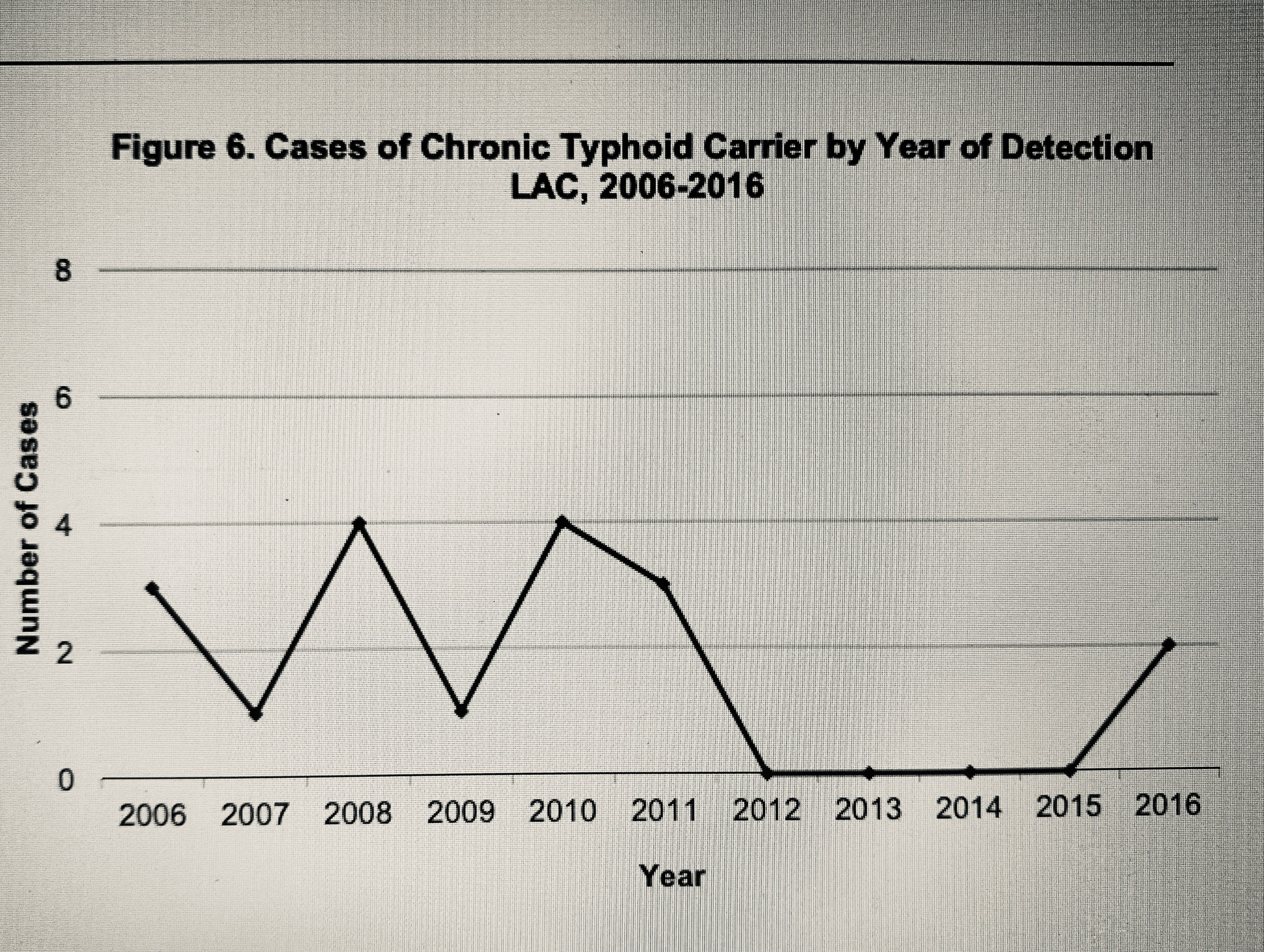

Today, typhoid carriers exist all over the world, but the highest incidence of

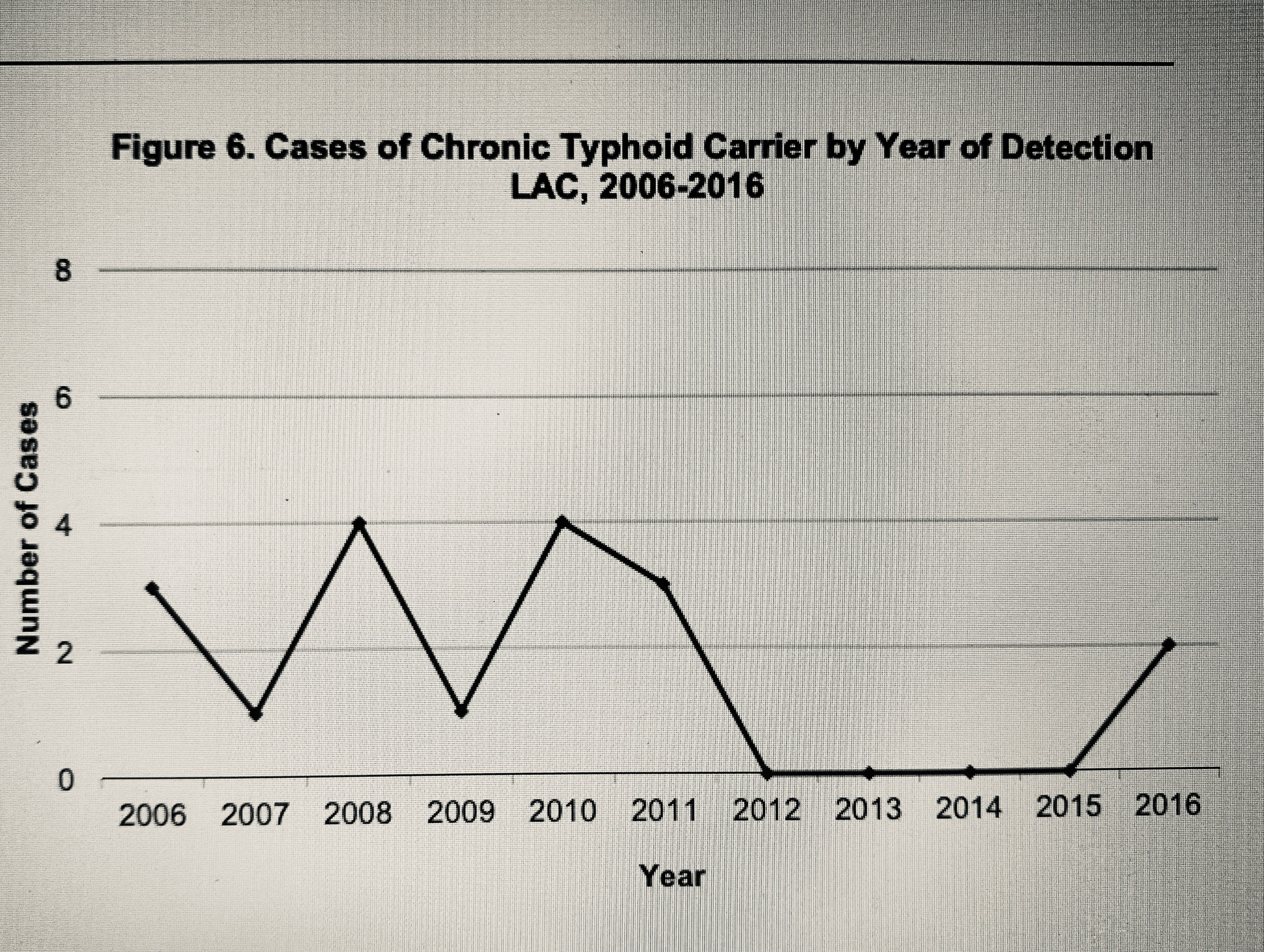

Today, typhoid carriers exist all over the world, but the highest incidence of asymptomatic

In medicine, any disease is classified asymptomatic if a patient tests as carrier for a disease or infection but experiences no symptoms. Whenever a medical condition fails to show noticeable symptoms after a diagnosis it might be considered asy ...

infection is likely to occur in South/Southeast Asian and Sub-Saharan countries. The Los Angeles County department of public health

The Los Angeles County Department of Public Health (DPH) provides public health services to Los Angeles County residents. Barbara Ferrer is the Director for the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health. Muntu Davis, MD, MPH is the Los Angel ...

tracks typhoid carriers and reports the number of carriers identified within the county yearly; between 2006 and 2016 0-4 new cases of typhoid carriers were identified per year. Cases of typhoid fever must be reported within one working day from identification. As of 2018, chronic typhoid carriers must sign a "Carrier Agreement" and are required to test for typhoid shedding twice yearly, ideally every 6 months. Carriers may be released from their agreements upon fulfilling "release" requirements, based on completion of a personalized treatment plan designed with medical professionals. Fecal or gallbladder carrier release requirements: 6 consecutive negative feces and urine specimens submitted at 1-month or greater intervals beginning at least 7 days after completion of therapy. Urinary or kidney carrier release requirements: 6 consecutive negative urine specimens submitted at 1-month or greater intervals beginning at least 7 days after completion of therapy. As of 2016 the male:female ratio of carriers in Los Angeles county was 3:1.

Due to the nature of asymptomatic cases, many questions remain about how individuals are able to tolerate infection for long periods of time, how to identify such cases, and efficient options for treatment. Researchers are currently working to understand asymptomatic infection with '' Salmonella'' species by studying infections in laboratory animals, which will ultimately lead to improved prevention and treatment options for typhoid carriers. In 2002, Dr. John Gunn described the ability of '' Salmonella'' sp. to form biofilm

A biofilm comprises any syntrophic consortium of microorganisms in which cells stick to each other and often also to a surface. These adherent cells become embedded within a slimy extracellular matrix that is composed of extracellular ...

s on gallstone

A gallstone is a stone formed within the gallbladder from precipitated bile components. The term cholelithiasis may refer to the presence of gallstones or to any disease caused by gallstones, and choledocholithiasis refers to the presence of mi ...

s in mice, providing a model for studying carriage in the gallbladder. Dr. Denise Monack

Denise may refer to:

* Denise (given name), people with the given name ''Denise''

* Denise (computer chip), a video graphics chip from the Amiga computer

* "Denise" (song), a 1963 song by Randy & the Rainbows

* Denise, Mato Grosso, a municipalit ...

and Dr. Stanley Falkow

Stanley "Stan" Falkow (January 24, 1934 – May 5, 2018) was an American microbiologist and a professor of microbiology at Georgetown University, University of Washington, and Stanford University School of Medicine. Falkow is known as the father ...

described a mouse model of asymptomatic intestinal and systemic infection in 2004, and Dr. Monack went on to demonstrate that a sub-population of superspreaders

A superspreading event (SSEV) is an event in which an infectious disease is spread much more than usual, while an unusually contagious organism infected with a disease is known as a superspreader. In the context of a human-borne illness, a super ...

are responsible for the majority of transmission to new hosts, following the 80/20 rule of disease transmission, and that the intestinal microbiota likely plays a role in transmission. Dr. Monack's mouse model allows long-term carriage of salmonella in mesenteric lymph nodes

The superior mesenteric lymph nodes may be divided into three principal groups:

* mesenteric lymph nodes

* ileocolic lymph nodes

* mesocolic lymph nodes

Structure

Mesenteric lymph nodes

The mesenteric lymph nodes or mesenteric glands are one of ...

, spleen

The spleen is an organ found in almost all vertebrates. Similar in structure to a large lymph node, it acts primarily as a blood filter. The word spleen comes .

and liver

The liver is a major Organ (anatomy), organ only found in vertebrates which performs many essential biological functions such as detoxification of the organism, and the Protein biosynthesis, synthesis of proteins and biochemicals necessary for ...

.

Vaccine development

British bacteriologist Almroth Edward Wright first developed an effective typhoid vaccine at the Army Medical School in

British bacteriologist Almroth Edward Wright first developed an effective typhoid vaccine at the Army Medical School in Netley

Netley, officially referred to as Netley Abbey, is a village on the south coast of Hampshire, England. It is situated to the south-east of the city of Southampton, and flanked on one side by the ruins of Netley Abbey and on the other by the R ...

, Hampshire

Hampshire (, ; abbreviated to Hants) is a ceremonial county, ceremonial and non-metropolitan county, non-metropolitan counties of England, county in western South East England on the coast of the English Channel. Home to two major English citi ...

. It was introduced in 1896 and used successfully by the British during the Second Boer War

The Second Boer War ( af, Tweede Vryheidsoorlog, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, the Anglo–Boer War, or the South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer Republics (the Sout ...

in South Africa. At that time, typhoid often killed more soldiers at war than were lost due to enemy combat. Wright further developed his vaccine at a newly opened research department at St Mary's Hospital Medical School in London from 1902, where he established a method for measuring protective substances (opsonin

Opsonins are extracellular proteins that, when bound to substances or cells, induce phagocytes to phagocytose the substances or cells with the opsonins bound. Thus, opsonins act as tags to label things in the body that should be phagocytosed (i.e. ...

) in human blood. Wright's version of the typhoid vaccine was produced by growing the bacterium at body temperature

Thermoregulation is the ability of an organism to keep its body temperature within certain boundaries, even when the surrounding temperature is very different. A thermoconforming organism, by contrast, simply adopts the surrounding temperature ...

in broth, then heating the bacteria to 60 °C to "heat inactivate" the pathogen, killing it, while keeping the surface antigen

In immunology, an antigen (Ag) is a molecule or molecular structure or any foreign particulate matter or a pollen grain that can bind to a specific antibody or T-cell receptor. The presence of antigens in the body may trigger an immune response. ...

s intact. The heat-killed bacteria was then injected into a patient. To show evidence of the vaccine's efficacy, Wright then collected serum samples from patients several weeks post-vaccination, and tested their serum's ability to agglutinate live typhoid bacteria. A "positive" result was represented by clumping of bacteria, indicating that the body was producing anti-serum (now called antibodies

An antibody (Ab), also known as an immunoglobulin (Ig), is a large, Y-shaped protein used by the immune system to identify and neutralize foreign objects such as pathogenic bacteria and viruses. The antibody recognizes a unique molecule of the ...

) against the pathogen.

Citing the example of the Second Boer War, during which many soldiers died from easily preventable diseases, Wright convinced the British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurk ...

that 10 million vaccine doses should be produced for the troops being sent to the Western Front, thereby saving up to half a million lives during World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

. The British Army was the only combatant at the outbreak of the war to have its troops fully immunized against the bacterium. For the first time, their casualties due to combat exceeded those from disease.

In 1909, Frederick F. Russell, a U.S. Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, cl ...

physician, adopted Wright's typhoid vaccine for use with the Army, and two years later, his vaccination program became the first in which an entire army was immunized. It eliminated typhoid as a significant cause of morbidity and mortality in the U.S. military. Typhoid vaccination for members of the American military became mandatory in 1911. Before the vaccine, the rate of typhoid fever in the military was 14,000 or greater per 100,000 soldiers. By World War I, the rate of typhoid in American soldiers was 37 per 100,000.

During the second world war, the United States army authorized the use of a trivalent vaccine – containing heat-inactivated Typhoid, Paratyphi A and Paratyphi B pathogens.

In 1934, discovery of the Vi capsular antigen by Arthur Felix and Miss S. R. Margaret Pitt enabled development of the safer Vi Antigen vaccine – which is widely in use today. Arthur Felix and Margaret Pitt also isolated the strain Ty2, which became the parent strain of Ty21a, the strain used as a live-attenuated vaccine for typhoid fever today.

Antibiotics and resistance

Chloramphenicol was isolated from '' Streptomyces'' by Dr. David Gotlieb during the 1940s. In 1948 American army doctors tested its efficacy in treating typhoid patients inKuala Lumpur

, anthem = '' Maju dan Sejahtera''

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, pushpin_map = Malaysia#Southeast Asia#Asia

, pushpin_map_caption =

, coordinates =

, su ...

, Malaysia. Individuals who received a full course of treatment cleared the infection, whereas patients given a lower dose had a relapse. Asymptomatic carriers continued to shed bacilli despite chloramphenicol treatment - only ill patients were improved with chloramphenicol. Resistance to chloramphenicol became frequent in Southeast Asia by the 1950s, and today chloramphenicol is only used as a last resort due to the high prevalence of resistance.

Terminology

The disease has been referred to by various names, often associated with symptoms, such as gastric fever, enteric fever, abdominal typhus, infantile remittant fever, slow fever, nervous fever, pythogenic fever, drain fever and low fever.Notable people

*Emperor Augustus