Twenty Thousand Leagues Under The Seas on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Seas'' (french: Vingt mille lieues sous les mers) is a classic

During the year 1866, ships of various nationalities sight a mysterious

During the year 1866, ships of various nationalities sight a mysterious

Captain Nemo's assumed name recalls Homer's ''

Captain Nemo's assumed name recalls Homer's ''

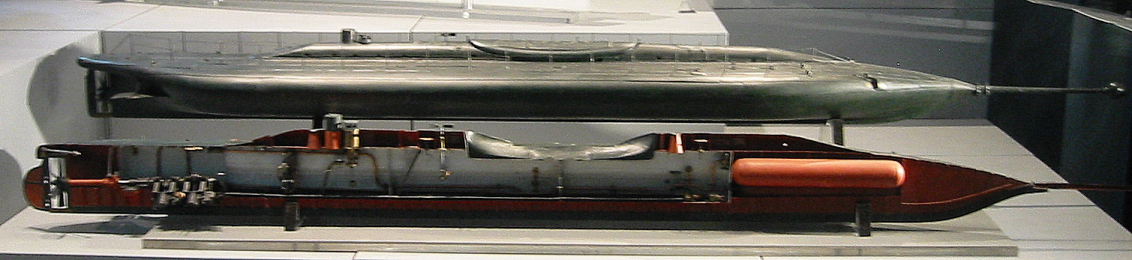

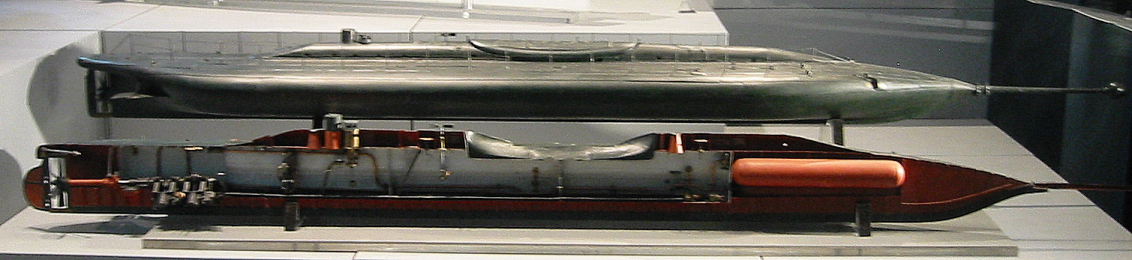

Verne took the name "Nautilus" from one of the earliest successful submarines, built in 1800 by

Verne took the name "Nautilus" from one of the earliest successful submarines, built in 1800 by

''Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Seas''

trans. by F. P. Walter in 1991, made available by Project Gutenberg. * , obsolete translation by Lewis Mercier, 1872 *

Vingt Mille Lieues Sous Les Mers

' 1871 French edition at the digital library of the National Library of France * *

''Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea'', audio version

Manuscripts of ''Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea'' in gallica.bnf.fr

{{DEFAULTSORT:Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Seas 1870 French novels 1870 science fiction novels French adventure novels French science fiction novels Hard science fiction Underwater novels French novels adapted into films French novels adapted into plays French novels adapted into television shows Science fiction novels adapted into films Novels adapted into comics Novels adapted into video games Novels adapted into radio programs French-language novels Novels about pirates Books about cephalopods Atlantis in fiction Submarines in fiction Novels set in Greece Novels set in India Novels set in Japan Novels set in New York City Novels set in Norway Novels set in Spain Fiction set in the 1860s Novels by Jules Verne

science fiction

Science fiction (sometimes shortened to Sci-Fi or SF) is a genre of speculative fiction which typically deals with imaginative and futuristic concepts such as advanced science and technology, space exploration, time travel, parallel uni ...

adventure novel

Adventure fiction is a type of fiction that usually presents danger, or gives the reader a sense of excitement. Some adventure fiction also satisfies the literary definition of romance fiction.

History

In the Introduction to the ''Encycloped ...

by French writer Jules Verne

Jules Gabriel Verne (;''Longman Pronunciation Dictionary''. ; 8 February 1828 – 24 March 1905) was a French novelist, poet, and playwright. His collaboration with the publisher Pierre-Jules Hetzel led to the creation of the '' Voyages extra ...

.

The novel was originally serialized from March 1869 through June 1870 in Pierre-Jules Hetzel's fortnightly periodical, the . A deluxe octavo edition, published by Hetzel in November 1871, included 111 illustrations by Alphonse de Neuville

Alphonse-Marie-Adolphe de Neuville (31 May 183518 May 1885) was a French academic painter who studied under Eugène Delacroix. His dramatic and intensely patriotic subjects illustrated episodes from the Franco-Prussian War, the Crimean War, the ...

and Édouard Riou

Édouard Riou (; 2 December 1833 – 27 January 1900) was a French illustrator who illustrated six novels by Jules Verne, as well as several other well-known works.

Life

Riou was born in 1833 in Saint-Servan, Ille-et-Vilaine, and studied ...

. The book was widely acclaimed on its release and remains so; it is regarded as one of the premier adventure novel

Adventure fiction is a type of fiction that usually presents danger, or gives the reader a sense of excitement. Some adventure fiction also satisfies the literary definition of romance fiction.

History

In the Introduction to the ''Encycloped ...

s and one of Verne's greatest works, along with ''Around the World in Eighty Days

''Around the World in Eighty Days'' (french: link=no, Le tour du monde en quatre-vingts jours) is an adventure novel by the French writer Jules Verne, first published in French in 1872. In the story, Phileas Fogg of London and his newly employe ...

'' and ''Journey to the Center of the Earth

''Journey to the Center of the Earth'' (french: Voyage au centre de la Terre), also translated with the variant titles ''A Journey to the Centre of the Earth'' and ''A Journey into the Interior of the Earth'', is a classic science fiction novel ...

''. Its depiction of Captain Nemo's underwater ship, the ''Nautilus'', is regarded as ahead of its time, since it accurately describes many features of today's submarines

A submarine (or sub) is a watercraft capable of independent operation underwater. It differs from a submersible, which has more limited underwater capability. The term is also sometimes used historically or colloquially to refer to remotely op ...

, which in the 1860s were comparatively primitive vessels.

A model of the French submarine ''Plongeur'' (launched in 1863) figured at the 1867 Exposition Universelle, where Jules Verne examined it and was inspired by it when writing his novel.Notice at the Musée de la Marine, Rochefort

Title

The title refers to the distance traveled under the various seas: 20,000 metric leagues (80,000 km, over 40,000 nautical miles), nearly twice the circumference of the Earth.Principal characters

*Professor Pierre Aronnax – the narrator of the story, a French natural scientist. *Conseil – Aronnax's Flemish servant, very devoted to him and knowledgeable in biological classification. *Ned Land – a Canadian harpooner, described as having "no equal in his dangerous trade." *Captain Nemo

Captain Nemo (; later identified as an Indian, Prince Dakkar) is a fictional character created by the French novelist Jules Verne (1828–1905). Nemo appears in two of Verne's science-fiction classics, ''Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Seas'' ...

– the designer and captain of the ''Nautilus

The nautilus (, ) is a pelagic marine mollusc of the cephalopod family Nautilidae. The nautilus is the sole extant family of the superfamily Nautilaceae and of its smaller but near equal suborder, Nautilina.

It comprises six living species in ...

.''

Plot

During the year 1866, ships of various nationalities sight a mysterious

During the year 1866, ships of various nationalities sight a mysterious sea monster

Sea monsters are beings from folklore believed to dwell in the sea and often imagined to be of immense size. Marine monsters can take many forms, including sea dragons, sea serpents, or tentacled beasts. They can be slimy and scaly and are o ...

, which, it is later suggested, might be a gigantic narwhal

The narwhal, also known as a narwhale (''Monodon monoceros''), is a medium-sized toothed whale that possesses a large " tusk" from a protruding canine tooth. It lives year-round in the Arctic waters around Greenland, Canada and Russia. It is ...

. The U.S. government assembles an expedition in New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

to find and destroy the monster. Professor Pierre Aronnax, a French marine biologist and the story's narrator, is in town at the time and receives a last-minute invitation to join the expedition; he accepts. Canadian

Canadians (french: Canadiens) are people identified with the country of Canada. This connection may be residential, legal, historical or cultural. For most Canadians, many (or all) of these connections exist and are collectively the source of ...

whaler

A whaler or whaling ship is a specialized vessel, designed or adapted for whaling: the catching or processing of whales.

Terminology

The term ''whaler'' is mostly historic. A handful of nations continue with industrial whaling, and one, Japa ...

and master harpoon

A harpoon is a long spear-like instrument and tool used in fishing, whaling, sealing, and other marine hunting to catch and injure large fish or marine mammals such as seals and whales. It accomplishes this task by impaling the target ani ...

er Ned Land and Aronnax's faithful manservant Conseil are also among the participants.

The expedition leaves Brooklyn aboard the United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

frigate ''Abraham Lincoln'', then travels south around Cape Horn

Cape Horn ( es, Cabo de Hornos, ) is the southernmost headland of the Tierra del Fuego archipelago of southern Chile, and is located on the small Hornos Island. Although not the most southerly point of South America (which are the Diego Ramí ...

into the Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the conti ...

. After a five-month search ending off Japan, the frigate locates and attacks the monster, which damages the ship's rudder. Aronnax and Land are hurled into the sea, and Conseil jumps into the water after them. They survive by climbing onto the "monster", which, they are startled to find, is a futuristic submarine. They wait on the deck of the vessel until morning, when they are captured, hauled inside, and introduced to the submarine's mysterious constructor and commander, Captain Nemo

Captain Nemo (; later identified as an Indian, Prince Dakkar) is a fictional character created by the French novelist Jules Verne (1828–1905). Nemo appears in two of Verne's science-fiction classics, ''Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Seas'' ...

.

The rest of the novel describes the protagonists' adventures aboard the ''Nautilus

The nautilus (, ) is a pelagic marine mollusc of the cephalopod family Nautilidae. The nautilus is the sole extant family of the superfamily Nautilaceae and of its smaller but near equal suborder, Nautilina.

It comprises six living species in ...

'', which was built in secrecy and now roams the seas beyond the reach of land-based governments. In self-imposed exile, Captain Nemo seems to have a dual motivation — a quest for scientific knowledge and a desire to escape terrestrial civilization

A civilization (or civilisation) is any complex society characterized by the development of a state, social stratification, urbanization, and symbolic systems of communication beyond natural spoken language (namely, a writing system).

...

. Nemo explains that his submarine is electrically powered and can conduct advanced marine research; he also tells his new passengers that his secret existence means he cannot let them leave — they must remain on board permanently.

They visit many ocean regions, some factual and others fictitious. The travelers view coral

Corals are marine invertebrates within the class Anthozoa of the phylum Cnidaria. They typically form compact colonies of many identical individual polyps. Coral species include the important reef builders that inhabit tropical oceans and se ...

formations, sunken vessels from the Battle of Vigo Bay

The Battle of Vigo Bay, also known as the Battle of Rande (; ), was a naval engagement fought on 23 October 1702 during the opening years of the War of the Spanish Succession. The engagement followed an Anglo-Dutch attempt to capture the Spanish ...

, the Antarctic

The Antarctic ( or , American English also or ; commonly ) is a polar region around Earth's South Pole, opposite the Arctic region around the North Pole. The Antarctic comprises the continent of Antarctica, the Kerguelen Plateau and othe ...

ice barrier, the Transatlantic telegraph cable

Transatlantic telegraph cables were undersea cables running under the Atlantic Ocean for telegraph communications. Telegraphy is now an obsolete form of communication, and the cables have long since been decommissioned, but telephone and data a ...

, and the legendary underwater realm of Atlantis

Atlantis ( grc, Ἀτλαντὶς νῆσος, , island of Atlas) is a fictional island mentioned in an allegory on the hubris of nations in Plato's works '' Timaeus'' and '' Critias'', wherein it represents the antagonist naval power that b ...

. They even travel to the South Pole and are trapped in an upheaval of an iceberg on the way back, caught in a narrow gallery of ice from which they are forced to dig themselves out. The passengers also don diving suit

A diving suit is a garment or device designed to protect a diver from the underwater environment. A diving suit may also incorporate a breathing gas supply (such as for a standard diving dress or atmospheric diving suit). but in most cases the te ...

s, hunt shark

Sharks are a group of elasmobranch fish characterized by a cartilaginous skeleton, five to seven gill slits on the sides of the head, and pectoral fins that are not fused to the head. Modern sharks are classified within the clade Selachi ...

s and other marine fauna with air guns in the underwater forests of Crespo Island, and also attend an undersea funeral for a crew member who died during a mysterious collision experienced by the ''Nautilus''. When the submarine returns to the Atlantic Ocean

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the " Old World" of Africa, Europe ...

, a school of giant squid

The giant squid (''Architeuthis dux'') is a species of deep-ocean dwelling squid in the family Architeuthidae. It can grow to a tremendous size, offering an example of abyssal gigantism: recent estimates put the maximum size at around Tra ...

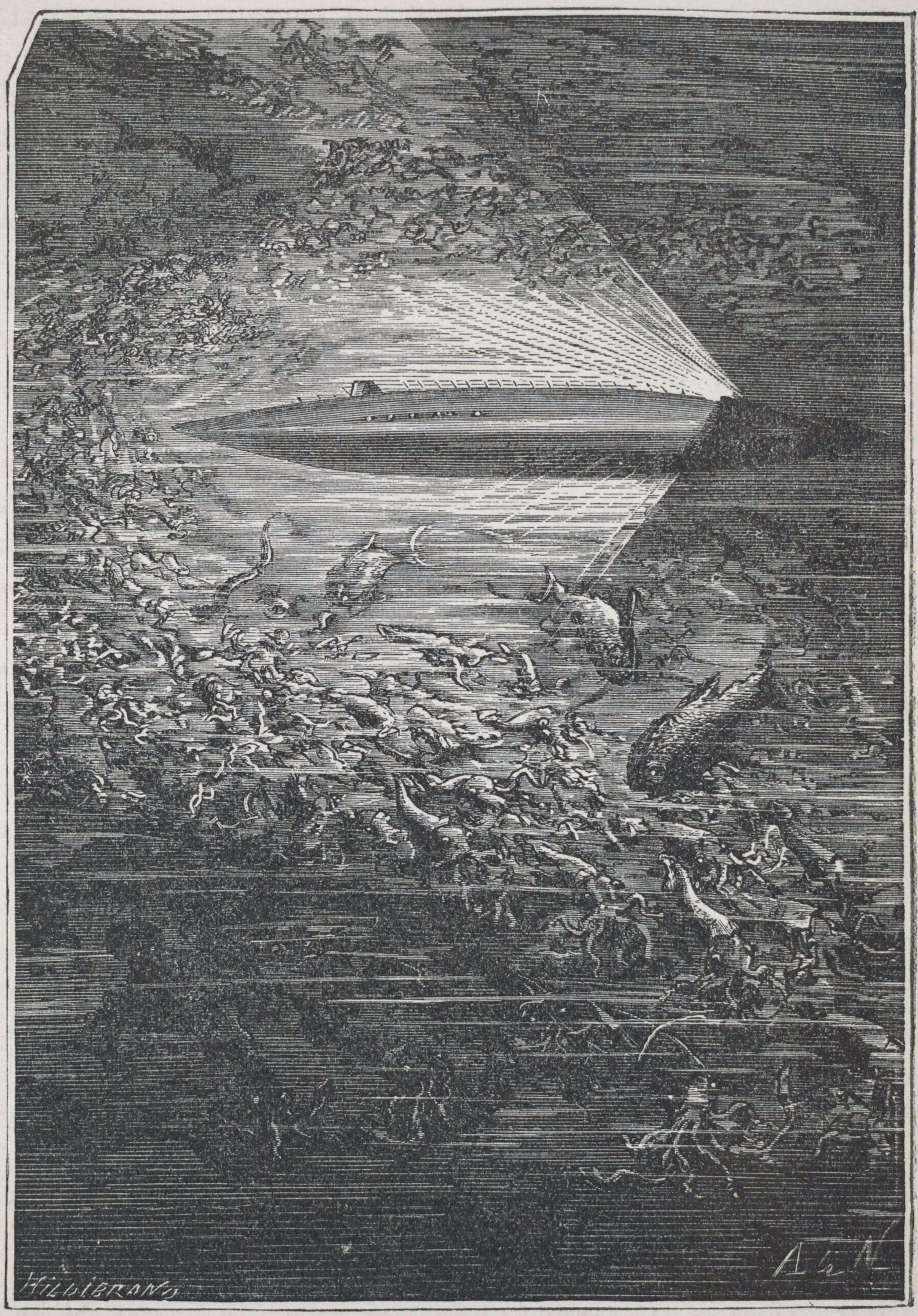

("devilfish") attacks the vessel and kills another crewman.

The novel's later pages suggest that Captain Nemo went into undersea exile after his homeland was conquered and his family slaughtered by a powerful imperialist nation. Following the episode of the devilfish, Nemo largely avoids Aronnax, who begins to side with Ned Land. Ultimately, the ''Nautilus'' is attacked by a warship

A warship or combatant ship is a naval ship that is built and primarily intended for naval warfare. Usually they belong to the armed forces of a state. As well as being armed, warships are designed to withstand damage and are usually faster ...

from the mysterious nation that has caused Nemo such suffering. Carrying out his quest for revenge, Nemo — whom Aronnax dubs an "archangel of hatred" — rams the ship below her waterline and sends her to the bottom, much to the professor's horror. Afterward, Nemo kneels before a portrait of his deceased wife and children, then sinks into a deep depression.

Circumstances aboard the submarine change drastically: watches are no longer kept, and the vessel wanders about aimlessly. Ned becomes so reclusive that Conseil fears for the harpooner's life. One morning, however, Ned announces that they are in sight of land and have a chance to escape. Professor Aronnax is more than ready to leave Captain Nemo, who now horrifies him, yet he is still drawn to the man. Fearing that Nemo's very presence could weaken his resolve, he avoids contact with the captain. Before their departure, however, the professor eavesdrops on Nemo and overhears him calling out in anguish, "O almighty God! Enough! Enough!" Aronnax immediately joins his companions, and they carry out their escape plans, but as they board the submarine's skiff, they realize that the ''Nautilus'' has seemingly blundered into the ocean's deadliest whirlpool, the Moskenstraumen, more commonly known as the "Maelstrom". Nevertheless, they manage to escape and find refuge on an island off the coast of Norway. The submarine's ultimate fate, however, remains unknown.

Themes and subtext

Captain Nemo's assumed name recalls Homer's ''

Captain Nemo's assumed name recalls Homer's ''Odyssey

The ''Odyssey'' (; grc, Ὀδύσσεια, Odýsseia, ) is one of two major ancient Greek epic poems attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest extant works of literature still widely read by modern audiences. As with the '' Iliad'', ...

'', when Odysseus encounters the monstrous Cyclops

In Greek mythology and later Roman mythology, the Cyclopes ( ; el, Κύκλωπες, ''Kýklōpes'', "Circle-eyes" or "Round-eyes"; singular Cyclops ; , ''Kýklōps'') are giant one-eyed creatures. Three groups of Cyclopes can be distinguish ...

Polyphemus

Polyphemus (; grc-gre, Πολύφημος, Polyphēmos, ; la, Polyphēmus ) is the one-eyed giant son of Poseidon and Thoosa in Greek mythology, one of the Cyclopes described in Homer's ''Odyssey''. His name means "abounding in songs and ...

in the course of his wanderings. Polyphemus asks Odysseus his name, and Odysseus replies that it is Outis () 'no one', translated into Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through ...

as "''Nemo''". Like Captain Nemo, Odysseus wanders the seas in exile (though only for 10 years) and similarly grieves the tragic deaths of his crewmen.

The novel repeatedly mentions the U.S. Naval Commander Matthew Fontaine Maury

Matthew Fontaine Maury (January 14, 1806February 1, 1873) was an American oceanographer and naval officer, serving the United States and then joining the Confederacy during the American Civil War.

He was nicknamed "Pathfinder of the Seas" and i ...

, an oceanographer who investigated the winds, seas, and currents, collected samples from the depths, and charted the world's oceans. Maury was internationally famous, and Verne may have known of his French ancestry.

The novel alludes to other Frenchmen, including Lapérouse, the celebrated explorer whose two sloops of war vanished during a voyage of global circumnavigation; Dumont d'Urville, a later explorer who found the remains of one of Lapérouse's ships; and Ferdinand de Lesseps

Ferdinand Marie, Comte de Lesseps (; 19 November 1805 – 7 December 1894) was a French diplomat and later developer of the Suez Canal, which in 1869 joined the Mediterranean and Red Seas, substantially reducing sailing distances and times ...

, builder of the Suez Canal

The Suez Canal ( arz, قَنَاةُ ٱلسُّوَيْسِ, ') is an artificial sea-level waterway in Egypt, connecting the Mediterranean Sea to the Red Sea through the Isthmus of Suez and dividing Africa and Asia. The long canal is a popula ...

and nephew of the sole survivor of Lapérouse's ill-fated expedition. The ''Nautilus'' follows in the footsteps of these men: she visits the waters where Lapérouse's vessels disappeared; she enters Torres Strait and becomes stranded there, as did d'Urville's ship, the ''Astrolabe''; and she passes beneath the Suez Canal via a fictitious underwater tunnel joining the Red Sea to the Mediterranean.

In possibly the novel's most famous episode, the above-cited battle with a school of giant squid

The giant squid (''Architeuthis dux'') is a species of deep-ocean dwelling squid in the family Architeuthidae. It can grow to a tremendous size, offering an example of abyssal gigantism: recent estimates put the maximum size at around Tra ...

, one of the monsters captures a crew member. Reflecting on the battle in the next chapter, Aronnax writes: "To convey such sights, it would take the pen of our most renowned poet, Victor Hugo, author of ''The Toilers of the Sea''." A bestselling novel in Verne's day, '' The Toilers of the Sea'' also features a threatening cephalopod: a laborer battles with an octopus, believed by critics to be symbolic of the Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution was the transition to new manufacturing processes in Great Britain, continental Europe, and the United States, that occurred during the period from around 1760 to about 1820–1840. This transition included going f ...

. Certainly Verne was influenced by Hugo's novel, and, in penning this variation on its octopus encounter, he may have intended the symbol to also take in the Revolutions of 1848

The Revolutions of 1848, known in some countries as the Springtime of the Peoples or the Springtime of Nations, were a series of political upheavals throughout Europe starting in 1848. It remains the most widespread revolutionary wave in Europ ...

.

Other symbols and themes pique modern critics. Margaret Drabble

Dame Margaret Drabble, Lady Holroyd, (born 5 June 1939) is an English biographer, novelist and short story writer.

Drabble's books include '' The Millstone'' (1965), which won the following year's John Llewellyn Rhys Memorial Prize, and '' Je ...

, for instance, argues that Verne's masterwork also anticipated the ecology movement

The environmental movement (sometimes referred to as the ecology movement), also including conservation and green politics, is a diverse philosophical, social, and political movement for addressing environmental issues. Environmentalists advoc ...

and influenced French ''avant-garde

The avant-garde (; In 'advance guard' or ' vanguard', literally 'fore-guard') is a person or work that is experimental, radical, or unorthodox with respect to art, culture, or society.John Picchione, The New Avant-garde in Italy: Theoretica ...

'' imagery. As for additional motifs in the novel, Captain Nemo repeatedly champions the world's persecuted and downtrodden. While in Mediterranean waters, the captain provides financial support to rebels resisting Ottoman rule during the Cretan Revolt of 1866–1869, proving to Professor Aronnax that he hadn't severed all relations with terrestrial mankind. In another episode, Nemo rescues an Indian

Indian or Indians may refer to:

Peoples South Asia

* Indian people, people of Indian nationality, or people who have an Indian ancestor

** Non-resident Indian, a citizen of India who has temporarily emigrated to another country

* South Asia ...

pearl diver from a shark attack, then gives the fellow a pouch full of pearls, more than the man could have gathered after years of his hazardous work. Nemo remarks later that the diver, as a native of British India

The provinces of India, earlier presidencies of British India and still earlier, presidency towns, were the administrative divisions of British governance on the Indian subcontinent. Collectively, they have been called British India. In one ...

, "lives in the land of the oppressed".

Indeed, the novel has an under-the-counter political vision, hinted at in the character and background of Captain Nemo himself. In the book's final form, Nemo says to professor Aronnax, "That Indian, sir, is an inhabitant of an oppressed country; and I am still, and shall be, to my last breath, one of them!" In the novel's initial drafts, the mysterious captain was a Polish nobleman, whose family and homeland were slaughtered by Russian forces during the Polish January Uprising

The January Uprising ( pl, powstanie styczniowe; lt, 1863 metų sukilimas; ua, Січневе повстання; russian: Польское восстание; ) was an insurrection principally in Russia's Kingdom of Poland that was aimed at ...

of 1863. However, these specifics were suppressed during the editing stages at the insistence of Verne's publisher Pierre-Jules Hetzel, believed responsible by today's scholars for many modifications of Verne's original manuscripts. At the time France was a putative ally of the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War ...

, hence Hetzel demanded that Verne suppress the identity of Nemo's enemy, not only to avoid political complications but also to avert lower sales should the novel appear in Russian translation. Hence Professor Aronnax never discovers Nemo's origins.

Even so, a trace remains of the novel's initial concept, a detail that may have eluded Hetzel: its allusion to an unsuccessful rebellion under a Polish hero, Tadeusz Kościuszko

Andrzej Tadeusz Bonawentura Kościuszko ( be, Andréj Tadévuš Banavientúra Kasciúška, en, Andrew Thaddeus Bonaventure Kosciuszko; 4 or 12 February 174615 October 1817) was a Polish military engineer, statesman, and military leader who ...

, leader of the uprising against Russian and Prussian control in 1794; Kościuszko mourned his country's prior defeat with the Latin exclamation "Finis Poloniae!" ("Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populou ...

is no more!").

Five years later, and again at Hetzel's insistence, Captain Nemo was revived and revamped for another Verne novel ''The Mysterious Island

''The Mysterious Island'' (french: L'Île mystérieuse) is a novel by Jules Verne, published in 1875. The original edition, published by Hetzel, contains a number of illustrations by Jules Férat. The novel is a crossover sequel to Verne's f ...

''. It alters the captain's nationality from Polish to Indian, changing him into a fictional descendant of Tipu Sultan

Tipu Sultan (born Sultan Fateh Ali Sahab Tipu, 1 December 1751 – 4 May 1799), also known as the Tiger of Mysore, was the ruler of the Kingdom of Mysore based in South India. He was a pioneer of rocket artillery.Dalrymple, p. 243 He i ...

, a prominent ruler of Mysore

Mysore (), officially Mysuru (), is a city in the southern part of the state of Karnataka, India. Mysore city is geographically located between 12° 18′ 26″ north latitude and 76° 38′ 59″ east longitude. It is located at an altitude o ...

who fought against the British East India Company

The East India Company (EIC) was an English, and later British, joint-stock company founded in 1600 and dissolved in 1874. It was formed to trade in the Indian Ocean region, initially with the East Indies (the Indian subcontinent and South ...

in the Anglo-Mysore Wars

The Anglo-Mysore Wars were a series of four wars fought during the last three decades of the 18th century between the Sultanate of Mysore on the one hand, and the British East India Company (represented chiefly by the neighbouring Madras Pres ...

. Thus, Nemo's unnamed enemy is converted into France's traditional antagonist, the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts e ...

. Born as an Indian aristocrat, one Prince Dakkar, Nemo participated in a major 19th-century uprising, the Indian Rebellion of 1857

The Indian Rebellion of 1857 was a major uprising in India in 1857–58 against the rule of the British East India Company, which functioned as a sovereign power on behalf of the British Crown. The rebellion began on 10 May 1857 in the for ...

, which was ultimately quashed by the British. After his family was killed by the British, Nemo fled beneath the seas, then made a final reappearance in the later novel's concluding pages.

Robert Fulton

Robert Fulton (November 14, 1765 – February 24, 1815) was an American engineer and inventor who is widely credited with developing the world's first commercially successful steamboat, the (also known as ''Clermont''). In 1807, that steambo ...

, who also invented the first commercially successful steamboat

A steamboat is a boat that is marine propulsion, propelled primarily by marine steam engine, steam power, typically driving propellers or Paddle steamer, paddlewheels. Steamboats sometimes use the ship prefix, prefix designation SS, S.S. or S/S ...

. Fulton named his submarine after a marine mollusk, the chambered nautilus

The nautilus (, ) is a pelagic marine mollusc of the cephalopod family Nautilidae. The nautilus is the sole extant family of the superfamily Nautilaceae and of its smaller but near equal suborder, Nautilina.

It comprises six living species in ...

. As noted above, Verne also studied a model of the newly developed French Navy

The French Navy (french: Marine nationale, lit=National Navy), informally , is the maritime arm of the French Armed Forces and one of the five military service branches of France. It is among the largest and most powerful naval forces in t ...

submarine ''Plongeur

Plongeur, the French word for '' diver'' may refer to the following

*The French submarine ''Plongeur''

*An employee charged with washing dishes

Dishwashing, washing the dishes, doing the dishes, or washing up in Great Britain, is the proces ...

'' at the 1867 Exposition Universelle, which guided him in his development of the novel's ''Nautilus''.

The diving gear used by passengers on the ''Nautilus'' is presented as a combination of two existing systems: 1) the surface-supplied hardhat suit, which was fed oxygen from the shore through tubes; 2) a later, self-contained apparatus designed by Benoit Rouquayrol and Auguste Denayrouze in 1865. Their invention featured tanks fastened to the back, which supplied air to a facial mask via the first-known demand regulator. The diver didn't swim but walked upright across the seafloor. This device was called an ''aérophore'' (Greek for "air-carrier"). Its air tanks could hold only thirty atmospheres, however Nemo claims that his futuristic adaptation could do far better: "The ''Nautiluss pumps allow me to store air under considerable pressure ... my diving equipment can supply breathable air for nine or ten hours."

Recurring themes in later books

As noted above, Hetzel and Verne generated a sequel of sorts to this novel: ''L'Île mystérieuse'' (''The Mysterious Island

''The Mysterious Island'' (french: L'Île mystérieuse) is a novel by Jules Verne, published in 1875. The original edition, published by Hetzel, contains a number of illustrations by Jules Férat. The novel is a crossover sequel to Verne's f ...

'', 1874), which attempts to round off narratives begun in ''Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Seas'' and ''Captain Grant's Children'', a.k.a. ''In Search of the Castaways

''In Search of the Castaways'' (french: Les Enfants du capitaine Grant, lit=The Children of Captain Grant) is a novel by the French writer Jules Verne, published in 1867–68. The original edition, published by Hetzel, contains a number of ill ...

''. While ''The Mysterious Island'' attempts to provide additional background on Nemo (or Prince Dakkar), it is muddled by irreconcilable chronological discrepancies between the two books and even within ''The Mysterious Island'' itself.

Verne returned to the theme of an outlaw submarine captain in his much later '' Facing the Flag'' (1896). This novel's chief villain, Ker Karraje, is simply an unscrupulous pirate acting purely for personal gain, completely devoid of the saving graces that gave Captain Nemo some nobility of character. Like Nemo, Ker Karraje plays "host" to unwilling French guests — but unlike Nemo, who manages to elude all pursuers — Karraje's criminal career is decisively thwarted by the combination of an international task force and the resistance of his French captives. Though also widely published and translated, '' Facing the Flag'' never achieved the lasting popularity of ''Twenty Thousand Leagues''.

Closer in approach to the original Nemo — though offering less detail and complexity of characterization — is the rebel aeronaut Robur in '' Robur the Conqueror'' and its sequel '' Master of the World''. Instead of the sea, Robur's medium is the sky: In these two novels he develops a pioneering helicopter and later a seaplane on wheels.

English translations

The novel was first translated into English in 1873 by ReverendLewis Page Mercier

Reverend Lewis Page Mercier (9 January 1820 – 2 November 1875) is known today as the translator, along with Eleanor Elizabeth King, of three of the best-known novels of Jules Verne: ''Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Seas'', ''From the Earth to ...

. Mercier cut nearly a quarter of Verne's French text and committed hundreds of translating errors, sometimes drastically distorting Verne's original (including uniformly mistranslating the French ''scaphandre'' — properly "diving suit" — as "cork-jacket", following a long-obsolete usage as "a type of lifejacket"). Some of these distortions may have been perpetrated for political reasons, such as Mercier's omitting the portraits of freedom fighters on the wall of Nemo's stateroom, a collection originally including Daniel O'Connell

Daniel O'Connell (I) ( ga, Dónall Ó Conaill; 6 August 1775 – 15 May 1847), hailed in his time as The Liberator, was the acknowledged political leader of Ireland's Roman Catholic majority in the first half of the 19th century. His mobilizat ...

among other international figures. Nevertheless, Mercier's text became the standard English translation, and some later "re-translations" continued to recycle its mistakes, including mistranslating the title as "... ''under the Sea"'', rather than "... ''under the Seas"''.

In 1962, Anthony Bonner published a fresh, essentially complete translation of the novel with Bantam Classics

Bantam Books is an American publishing house owned entirely by parent company Random House, a subsidiary of Penguin Random House; it is an imprint of the Random House Publishing Group. It was formed in 1945 by Walter B. Pitkin, Jr., Sidney B ...

. This edition also included a special introduction written by the sci-fi author Ray Bradbury

Ray Douglas Bradbury (; August 22, 1920June 5, 2012) was an American author and screenwriter. One of the most celebrated 20th-century American writers, he worked in a variety of modes, including fantasy, science fiction, horror, mystery, and ...

, comparing Captain Nemo to Captain Ahab of ''Moby-Dick

''Moby-Dick; or, The Whale'' is an 1851 novel by American writer Herman Melville. The book is the sailor Ishmael's narrative of the obsessive quest of Ahab, captain of the whaling ship ''Pequod'', for revenge against Moby Dick, the giant whi ...

''.

A significant modern revision of Mercier's translation appeared in 1966, prepared by Walter James Miller and published by Washington Square Press. Miller addressed many of Mercier's errors in the volume's preface and restored a number of his deletions in the text. In 1993, Miller collaborated with his fellow Vernian Frederick Paul Walter to produce "The Completely Restored and Annotated Edition", published in 1993 by the Naval Institute Press

The United States Naval Institute (USNI) is a private non-profit military association that offers independent, nonpartisan forums for debate of national security issues. In addition to publishing magazines and books, the Naval Institute holds se ...

.Jules Verne (author), Walter James Miller (trans.), Frederick Paul Walter (trans.). ''Jules Verne's 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea: A Completely Restored and Annotated Edition'', Naval Institute Press

The United States Naval Institute (USNI) is a private non-profit military association that offers independent, nonpartisan forums for debate of national security issues. In addition to publishing magazines and books, the Naval Institute holds se ...

, 1993. . Its text took advantage of Walter's unpublished translation, which Project Gutenberg

Project Gutenberg (PG) is a volunteer effort to digitize and archive cultural works, as well as to "encourage the creation and distribution of eBooks."

It was founded in 1971 by American writer Michael S. Hart and is the oldest digital libr ...

later made available online.

In 1998, William Butcher issued a new, annotated translation with the title ''Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Seas'', published by Oxford University Press

Oxford University Press (OUP) is the university press of the University of Oxford. It is the largest university press in the world, and its printing history dates back to the 1480s. Having been officially granted the legal right to print book ...

(). Butcher includes detailed notes, a comprehensive bibliography, appendices and a wide-ranging introduction studying the novel from a literary perspective. In particular, his original research on the two manuscripts studies the radical changes to the plot and to the character of Nemo urged on Verne by Hetzel, his publisher.

In 2010 Frederick Paul Walter issued a fully revised, newly researched translation, ''20,000 Leagues Under the Seas: A World Tour Underwater''. Complete with an extensive introduction, textual notes, and bibliography, it appeared in an omnibus of five of Walter's Verne translations titled ''Amazing Journeys: Five Visionary Classics'' and published by State University of New York Press

The State University of New York (SUNY, , ) is a system of public colleges and universities in the State of New York. It is one of the largest comprehensive system of universities, colleges, and community colleges in the United States. Led by ...

().

Reception

The science fiction writer Theodore L. Thomas criticized the novel in 1961, claiming that "there is not a single bit of valid speculation" in the book and that "none of its predictions has come true". He described its depictions of Nemo's diving gear, underwater activities, and the ''Nautilus'' as "pretty bad, behind the times even for 1869 ... In none of these technical situations did Verne take advantage of knowledge readily available to him at the time." However, the notes to the 1993 translation point out that the errors noted by Thomas were in fact in Mercier's translation, not in the original. Despite his criticisms, Thomas conceded: "Put them all together with the magic of Verne's story-telling ability, and something flames up. A story emerges that sweeps incredulity before it".Adaptations and variations

Captain Nemo's nationality is presented in manyfeature film

A feature film or feature-length film is a narrative film (motion picture or "movie") with a running time long enough to be considered the principal or sole presentation in a commercial entertainment program. The term ''feature film'' originall ...

and video realizations as European. However, he's depicted as Indian by Omar Sharif

Omar Sharif ( ar, عمر الشريف ; born Michel Yusef Dimitri Chalhoub , 10 April 193210 July 2015) was an Egyptian actor, generally regarded as one of his country's greatest male film stars. He began his career in his native country in the ...

in the 1973 European miniseries

A miniseries or mini-series is a television series that tells a story in a predetermined, limited number of episodes. "Limited series" is another more recent US term which is sometimes used interchangeably. , the popularity of miniseries format ...

''The Mysterious Island

''The Mysterious Island'' (french: L'Île mystérieuse) is a novel by Jules Verne, published in 1875. The original edition, published by Hetzel, contains a number of illustrations by Jules Férat. The novel is a crossover sequel to Verne's f ...

''. Nemo also appears as an Indian in the 1916 silent film version of the novel (which adds elements from ''The Mysterious Island''). Indian actor Naseeruddin Shah

Naseeruddin Shah (born 20 July 1950) is an Indian actor. He is notable in Indian parallel cinema. He has also starred in international productions. He has won numerous awards in his career, including three National Film Awards, three Filmfare ...

plays Captain Nemo in the film ''The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen

''The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen'' (''LoEG'') is a comic book series (inspired by the 1960 British film ''The League of Gentlemen'') co-created by writer Alan Moore and artist Kevin O'Neill which began in 1999. The series spans four vol ...

''. The character is portrayed as Indian in the graphic novel. In Walt Disney

Walter Elias Disney (; December 5, 1901December 15, 1966) was an American animator, film producer and entrepreneur. A pioneer of the American animation industry, he introduced several developments in the production of cartoons. As a film p ...

's ''20,000 Leagues Under the Sea

''Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Seas'' (french: Vingt mille lieues sous les mers) is a classic science fiction adventure novel by French writer Jules Verne.

The novel was originally serialized from March 1869 through June 1870 in Pierre-J ...

'' (1954), a live-action Technicolor film of the novel, Captain Nemo seems European, albeit dark-complected. In the Disney adaptation, he's played by British actor James Mason

James Neville Mason (; 15 May 190927 July 1984) was an English actor. He achieved considerable success in British cinema before becoming a star in Hollywood. He was the top box-office attraction in the UK in 1944 and 1945; his British films inc ...

, with — as in the novel itself — no mention of his being Indian. Disney's film script elaborates on background hints in Verne's original: in an effort to acquire Nemo's scientific secrets, his wife and son were tortured to death by an unnamed government overseeing the fictional prison camp of Rorapandi. This is the captain's motivation for sinking warships in the film. Also, Nemo's submarine confines her activities to a defined, circular section of the Pacific Ocean, unlike the movements of the original ''Nautilus''.

Finally, Nemo is again depicted as Indian in the Soviet 3-episode TV film ''Captain Nemo

Captain Nemo (; later identified as an Indian, Prince Dakkar) is a fictional character created by the French novelist Jules Verne (1828–1905). Nemo appears in two of Verne's science-fiction classics, ''Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Seas'' ...

'' (1975), which also includes some plot details from ''The Mysterious Island''.

See also

*References

External links

''Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Seas''

trans. by F. P. Walter in 1991, made available by Project Gutenberg. * , obsolete translation by Lewis Mercier, 1872 *

Vingt Mille Lieues Sous Les Mers

' 1871 French edition at the digital library of the National Library of France * *

''Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea'', audio version

Manuscripts of ''Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea'' in gallica.bnf.fr

{{DEFAULTSORT:Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Seas 1870 French novels 1870 science fiction novels French adventure novels French science fiction novels Hard science fiction Underwater novels French novels adapted into films French novels adapted into plays French novels adapted into television shows Science fiction novels adapted into films Novels adapted into comics Novels adapted into video games Novels adapted into radio programs French-language novels Novels about pirates Books about cephalopods Atlantis in fiction Submarines in fiction Novels set in Greece Novels set in India Novels set in Japan Novels set in New York City Novels set in Norway Novels set in Spain Fiction set in the 1860s Novels by Jules Verne