Turtle (submersible) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Turtle'' (also called ''American Turtle'') was the world's first

''Turtle'' (also called ''American Turtle'') was the world's first

The American inventor

The American inventor  Though the design of the ''Turtle'' was necessarily shrouded in secrecy, based on his mechanical engineering expertise and previous experience in design and manufacturing, it seems Doolittle designed and crafted (and probably funded) the brass and the moving parts of the ''Turtle'', including the propulsion system, the navigation instruments, the brass foot-operated water-ballast and forcing pumps, the depth gauge and compass, the brass crown hatch, the clockwork detonator for the mine, and the hand-operated propeller crank and foot-driven treadle with flywheel. According to a letter from Dr. Benjamin Gale to Benjamin Franklin, Doolittle also designed the mine attachment mechanism, "those Parts which Conveys the Powder, and secures the same to the Bottom of the Ship". The most historically important innovation in the ''Turtle'' was the propeller, as it was the first known use of one in a watercraft: it was described as an "oar for rowing forward or backward", with "no precedent" design and in a letter by Dr. Benjamin Gale to Silas Dean as "a pair of oars fixed like the two opposite arms of a windmill" and as "two oars or paddles" that were "like the arms of a windmill... long, and about wide." As it was probably brass, it was thus likely designed and forged by Doolittle. Doolittle also likely provided the scarce commodities of gunpowder and lead ballast as well. The wealthy Doolittle, nearly 20 years older than the Yale student Bushnell, was a founder and long time Warden of Trinity Episcopal Church on the Green, and was in charge of New Haven's port inspection and beacon-alarm systems – suggesting that Doolittle provided much of the political and financial leadership in building the ''Turtle'' as well as its brass and moving parts.

In making the hull, Bushnell enlisted the services of several skilled artisans, including his brother the farmer Ezra Bushnell and ship's carpenter Phineas Pratt, both, like David Bushnell, from Saybrook. The hull was "constructed of oak, somewhat like a barrel and bound by heavy wrought-iron hoops." The shape of the hull, Gale informed Silas Deane, "has the nearest resemblance to the two upper shells of a Tortoise joined together."

Named for its shape, ''Turtle'' resembled a large

Though the design of the ''Turtle'' was necessarily shrouded in secrecy, based on his mechanical engineering expertise and previous experience in design and manufacturing, it seems Doolittle designed and crafted (and probably funded) the brass and the moving parts of the ''Turtle'', including the propulsion system, the navigation instruments, the brass foot-operated water-ballast and forcing pumps, the depth gauge and compass, the brass crown hatch, the clockwork detonator for the mine, and the hand-operated propeller crank and foot-driven treadle with flywheel. According to a letter from Dr. Benjamin Gale to Benjamin Franklin, Doolittle also designed the mine attachment mechanism, "those Parts which Conveys the Powder, and secures the same to the Bottom of the Ship". The most historically important innovation in the ''Turtle'' was the propeller, as it was the first known use of one in a watercraft: it was described as an "oar for rowing forward or backward", with "no precedent" design and in a letter by Dr. Benjamin Gale to Silas Dean as "a pair of oars fixed like the two opposite arms of a windmill" and as "two oars or paddles" that were "like the arms of a windmill... long, and about wide." As it was probably brass, it was thus likely designed and forged by Doolittle. Doolittle also likely provided the scarce commodities of gunpowder and lead ballast as well. The wealthy Doolittle, nearly 20 years older than the Yale student Bushnell, was a founder and long time Warden of Trinity Episcopal Church on the Green, and was in charge of New Haven's port inspection and beacon-alarm systems – suggesting that Doolittle provided much of the political and financial leadership in building the ''Turtle'' as well as its brass and moving parts.

In making the hull, Bushnell enlisted the services of several skilled artisans, including his brother the farmer Ezra Bushnell and ship's carpenter Phineas Pratt, both, like David Bushnell, from Saybrook. The hull was "constructed of oak, somewhat like a barrel and bound by heavy wrought-iron hoops." The shape of the hull, Gale informed Silas Deane, "has the nearest resemblance to the two upper shells of a Tortoise joined together."

Named for its shape, ''Turtle'' resembled a large

One of the central concerns for Bushnell as he planned and constructed the ''Turtle'' was funding.

Due to colonial efforts to keep the existence of this potential war asset secret from the British, the colonial records concerning the ''Turtle'' are often short and cryptic. Most of the records that do exist concern Bushnell's request for funds. Bushnell met with Jonathan Trumbull, the governor of Connecticut, during 1771 seeking financial support. Trumbull also sent requests to

One of the central concerns for Bushnell as he planned and constructed the ''Turtle'' was funding.

Due to colonial efforts to keep the existence of this potential war asset secret from the British, the colonial records concerning the ''Turtle'' are often short and cryptic. Most of the records that do exist concern Bushnell's request for funds. Bushnell met with Jonathan Trumbull, the governor of Connecticut, during 1771 seeking financial support. Trumbull also sent requests to

At 11:00 pm on September 6, 1776, Sgt. Lee piloted the submersible toward Admiral Richard Howe's flagship, , then moored off

At 11:00 pm on September 6, 1776, Sgt. Lee piloted the submersible toward Admiral Richard Howe's flagship, , then moored off

File:THE TURTLE, ESSEX CT.jpg, 1976 functional replica that is now at the

''Turtle'' (also called ''American Turtle'') was the world's first

''Turtle'' (also called ''American Turtle'') was the world's first submersible

A submersible is a small watercraft designed to operate underwater. The term "submersible" is often used to differentiate from other underwater vessels known as submarines, in that a submarine is a fully self-sufficient craft, capable of ind ...

vessel with a documented record of use in combat. It was built in 1775 by American David Bushnell

David Bushnell (August 30, 1740 – 1824 or 1826), of Westbrook, Connecticut, was an American inventor, a patriot, one of the first American combat engineers, a teacher, and a medical doctor.

Bushnell invented the first submarine to be used in ...

as a means of attaching explosive charges to ships in a harbor, for use against Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

vessels occupying American harbors during the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

. Connecticut Governor Jonathan Trumbull

Jonathan Trumbull Sr. (October 12, 1710August 17, 1785) was an American politician and statesman who served as Governor of Connecticut during the American Revolution. Trumbull and Nicholas Cooke of Rhode Island were the only men to serve as gov ...

recommended the invention to George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of th ...

, who provided funds and support for the development and testing of the machine.

Several attempts were made using ''Turtle'' to affix explosives to the undersides of British warships in New York Harbor

New York Harbor is at the mouth of the Hudson River where it empties into New York Bay near the East River tidal estuary, and then into the Atlantic Ocean on the east coast of the United States. It is one of the largest natural harbors in t ...

in 1776. All failed, and her transport ship was sunk later that year by the British with the submarine aboard. Bushnell claimed eventually to have recovered the machine, but its final fate is unknown. Modern replicas of ''Turtle'' have been constructed and are on display in the Connecticut River Museum

The Connecticut River Museum is a U.S. educational and cultural institution based at Steamboat Dock in Essex, Connecticut that focuses on the marine environment and maritime heritage of the Connecticut River Valley.

The three-story Connecticut R ...

, the U.S. Navy's Submarine Force Library and Museum

The United States Navy Submarine Force Library and Museum is located on the Thames River in Groton, Connecticut. It is the only submarine museum managed exclusively by the Naval History & Heritage Command division of the Navy, and this makes it a ...

, the Royal Navy Submarine Museum

The Royal Navy Submarine Museum at Gosport is a maritime museum tracing the international history of submarine development from the age of Alexander the Great to the present day, and particularly the history of the Royal Navy Submarine Service ...

, and the Oceanographic Museum

The Oceanographic Museum (''Musée océanographique'') is a museum of marine sciences in Monaco-Ville, Monaco.

This building is part of the Institut océanographique, which is committed to sharing its knowledge of the oceans.

History

The ...

(Monaco).

Development

The American inventor

The American inventor David Bushnell

David Bushnell (August 30, 1740 – 1824 or 1826), of Westbrook, Connecticut, was an American inventor, a patriot, one of the first American combat engineers, a teacher, and a medical doctor.

Bushnell invented the first submarine to be used in ...

made the idea of a submersible vessel for use in lifting the British naval blockade during the American War of Independence

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

. Bushnell may have begun studying underwater explosions while at Yale College

Yale College is the undergraduate college of Yale University. Founded in 1701, it is the original school of the university. Although other Yale schools were founded as early as 1810, all of Yale was officially known as Yale College until 1887, ...

. By early 1775, he had created a reliable method for detonating underwater explosives, a clockwork connected to a musket

A musket is a muzzle-loaded long gun that appeared as a smoothbore weapon in the early 16th century, at first as a heavier variant of the arquebus, capable of penetrating plate armour. By the mid-16th century, this type of musket gradually d ...

firing mechanism, probably a flintlock

Flintlock is a general term for any firearm that uses a flint-striking lock (firearm), ignition mechanism, the first of which appeared in Western Europe in the early 16th century. The term may also apply to a particular form of the mechanism its ...

, adapted for the purpose.Diamant, p. 22

After the Battles of Lexington and Concord

The Battles of Lexington and Concord were the first military engagements of the American Revolutionary War. The battles were fought on April 19, 1775, in Middlesex County, Province of Massachusetts Bay, within the towns of Lexington, Concord ...

in April 1775, Bushnell began work near Old Saybrook

Old Saybrook is a town in Middlesex County, Connecticut, United States. The population was 10,481 at the 2020 census. It contains the incorporated borough of Fenwick, as well as the census-designated places of Old Saybrook Center and Saybro ...

on a small, individually manned submersible designed to attach an explosive charge to the hull of an enemy ship, which, he wrote Benjamin Franklin, would be, "Constructed with Great Simplicity and upon Principles of Natural Philosophy."

Little is known about the origin, inspiration, and influences for Bushnell's invention. It seems clear Bushnell knew of the work of the Dutch inventor Cornelius Drebbel

Cornelis Jacobszoon Drebbel ( ) (1572 – 7 November 1633) was a Dutch engineer and inventor. He was the builder of the first operational submarine in 1620 and an innovator who contributed to the development of measurement and control systems, op ...

.

According to Dr. Benjamin Gale

Benjamin Gale (December 14, 1715May 6, 1790) was an American physician, scientist, agriculturist, inventor and political polemicist who was known for his political protests against the New Lights, which resulted in a fifteen year pamphlet war ...

, a doctor who taught at Yale, the many brass and mechanical (moving) parts of the submarine were built by the New Haven

New Haven is a city in the U.S. state of Connecticut. It is located on New Haven Harbor on the northern shore of Long Island Sound in New Haven County, Connecticut and is part of the New York City metropolitan area. With a population of 134,02 ...

clock-maker, engraver, silversmith, brass manufacturer and inventor Isaac Doolittle

Isaac Doolittle (August 3, 1721 – February 13, 1800) was an early American clockmaker, inventor, engineer, manufacturer, militia officer, entrepreneur, printer, politician, and brass, iron, and silver artisan. Doolittle was a watchmaker and clo ...

,Diamant, p. 23 whose shop was just a half block from Yale. Though Bushnell is given the overall design credit for the ''Turtle'' by Gale and others, Doolittle was well known as an "ingenious mechanic" (i.e. an engineer), engraver, and metalworker. He had both designed and manufactured complicated brass-wheel hall-clocks, a mahogany printing-press in 1769 (the first made in America, after Doolittle successfully duplicated the iron screw), brass compasses, and surveying instruments. He also founded and owned a brass foundry where he cast bells. At the start of the American Revolution,the wealthy and patriotic Doolittle built a gunpowder mill with two partners in New Haven to support the war, and was sent by the Connecticut government to prospect for lead.

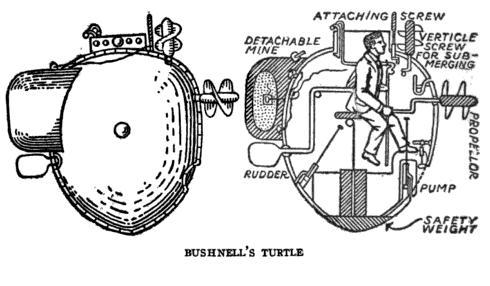

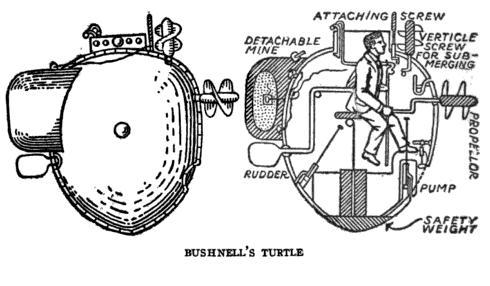

Though the design of the ''Turtle'' was necessarily shrouded in secrecy, based on his mechanical engineering expertise and previous experience in design and manufacturing, it seems Doolittle designed and crafted (and probably funded) the brass and the moving parts of the ''Turtle'', including the propulsion system, the navigation instruments, the brass foot-operated water-ballast and forcing pumps, the depth gauge and compass, the brass crown hatch, the clockwork detonator for the mine, and the hand-operated propeller crank and foot-driven treadle with flywheel. According to a letter from Dr. Benjamin Gale to Benjamin Franklin, Doolittle also designed the mine attachment mechanism, "those Parts which Conveys the Powder, and secures the same to the Bottom of the Ship". The most historically important innovation in the ''Turtle'' was the propeller, as it was the first known use of one in a watercraft: it was described as an "oar for rowing forward or backward", with "no precedent" design and in a letter by Dr. Benjamin Gale to Silas Dean as "a pair of oars fixed like the two opposite arms of a windmill" and as "two oars or paddles" that were "like the arms of a windmill... long, and about wide." As it was probably brass, it was thus likely designed and forged by Doolittle. Doolittle also likely provided the scarce commodities of gunpowder and lead ballast as well. The wealthy Doolittle, nearly 20 years older than the Yale student Bushnell, was a founder and long time Warden of Trinity Episcopal Church on the Green, and was in charge of New Haven's port inspection and beacon-alarm systems – suggesting that Doolittle provided much of the political and financial leadership in building the ''Turtle'' as well as its brass and moving parts.

In making the hull, Bushnell enlisted the services of several skilled artisans, including his brother the farmer Ezra Bushnell and ship's carpenter Phineas Pratt, both, like David Bushnell, from Saybrook. The hull was "constructed of oak, somewhat like a barrel and bound by heavy wrought-iron hoops." The shape of the hull, Gale informed Silas Deane, "has the nearest resemblance to the two upper shells of a Tortoise joined together."

Named for its shape, ''Turtle'' resembled a large

Though the design of the ''Turtle'' was necessarily shrouded in secrecy, based on his mechanical engineering expertise and previous experience in design and manufacturing, it seems Doolittle designed and crafted (and probably funded) the brass and the moving parts of the ''Turtle'', including the propulsion system, the navigation instruments, the brass foot-operated water-ballast and forcing pumps, the depth gauge and compass, the brass crown hatch, the clockwork detonator for the mine, and the hand-operated propeller crank and foot-driven treadle with flywheel. According to a letter from Dr. Benjamin Gale to Benjamin Franklin, Doolittle also designed the mine attachment mechanism, "those Parts which Conveys the Powder, and secures the same to the Bottom of the Ship". The most historically important innovation in the ''Turtle'' was the propeller, as it was the first known use of one in a watercraft: it was described as an "oar for rowing forward or backward", with "no precedent" design and in a letter by Dr. Benjamin Gale to Silas Dean as "a pair of oars fixed like the two opposite arms of a windmill" and as "two oars or paddles" that were "like the arms of a windmill... long, and about wide." As it was probably brass, it was thus likely designed and forged by Doolittle. Doolittle also likely provided the scarce commodities of gunpowder and lead ballast as well. The wealthy Doolittle, nearly 20 years older than the Yale student Bushnell, was a founder and long time Warden of Trinity Episcopal Church on the Green, and was in charge of New Haven's port inspection and beacon-alarm systems – suggesting that Doolittle provided much of the political and financial leadership in building the ''Turtle'' as well as its brass and moving parts.

In making the hull, Bushnell enlisted the services of several skilled artisans, including his brother the farmer Ezra Bushnell and ship's carpenter Phineas Pratt, both, like David Bushnell, from Saybrook. The hull was "constructed of oak, somewhat like a barrel and bound by heavy wrought-iron hoops." The shape of the hull, Gale informed Silas Deane, "has the nearest resemblance to the two upper shells of a Tortoise joined together."

Named for its shape, ''Turtle'' resembled a large clam

Clam is a common name for several kinds of bivalve molluscs. The word is often applied only to those that are edible and live as infauna, spending most of their lives halfway buried in the sand of the seafloor or riverbeds. Clams have two she ...

as much as a turtle

Turtles are an order of reptiles known as Testudines, characterized by a special shell developed mainly from their ribs. Modern turtles are divided into two major groups, the Pleurodira (side necked turtles) and Cryptodira (hidden necked tu ...

; it was about long (according to the original specifications), tall, and about wide, and consisted of two wooden shells covered with tar

Tar is a dark brown or black viscous liquid of hydrocarbons and free carbon, obtained from a wide variety of organic materials through destructive distillation. Tar can be produced from coal, wood, petroleum, or peat. "a dark brown or black bit ...

and reinforced with steel bands.Schecter, p. 172 It dived by allowing water into a bilge

The bilge of a ship or boat is the part of the hull that would rest on the ground if the vessel were unsupported by water. The "turn of the bilge" is the transition from the bottom of a hull to the sides of a hull.

Internally, the bilges (us ...

tank at the bottom of the vessel and ascended by pushing water out through a hand pump. It was propelled vertically and horizontally by hand-cranked and pedal-powered propellers, respectively. It also had of lead aboard, which could be released in a moment to increase buoyancy. Manned and operated by one person, the vessel contained enough air for about thirty minutes and had a speed in calm water of about .

Six small pieces of thick glass in the top of the submarine provided natural light. The internal instruments had small pieces of bioluminescent

Bioluminescence is the production and emission of light by living organisms. It is a form of chemiluminescence. Bioluminescence occurs widely in marine vertebrates and invertebrates, as well as in some Fungus, fungi, microorganisms including ...

foxfire

Foxfire, also called fairy fire and chimpanzee fire, is the bioluminescence created by some species of fungi present in decaying wood. The bluish-green glow is attributed to a luciferase, an oxidative enzyme, which emits light as it reacts with ...

affixed to the needles to indicate their position in the dark. During trials in November 1775, Bushnell discovered that this illumination failed when the temperature dropped too low. Although repeated requests were made to Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin ( April 17, 1790) was an American polymath who was active as a writer, scientist, inventor, statesman, diplomat, printer, publisher, and political philosopher. Encyclopædia Britannica, Wood, 2021 Among the leading inte ...

for possible alternatives, none was forthcoming, and ''Turtle'' was sidelined for the winter.

Bushnell's basic design included some elements present in earlier experimental submersibles. The method of raising and lowering the vessel was similar to that developed by Nathaniel Simons in 1729, and the gaskets used to make watertight connections around the connections between the internal and external controls also may have come from Simons, who constructed a submersible based on a 17th-century Italian design by Giovanni Alfonso Borelli

Giovanni Alfonso Borelli (; 28 January 1608 – 31 December 1679) was a Renaissance Italian physiologist, physicist, and mathematician. He contributed to the modern principle of scientific investigation by continuing Galileo's practice of testi ...

.Rindskopf et al, p. 29

Preparation for use

One of the central concerns for Bushnell as he planned and constructed the ''Turtle'' was funding.

Due to colonial efforts to keep the existence of this potential war asset secret from the British, the colonial records concerning the ''Turtle'' are often short and cryptic. Most of the records that do exist concern Bushnell's request for funds. Bushnell met with Jonathan Trumbull, the governor of Connecticut, during 1771 seeking financial support. Trumbull also sent requests to

One of the central concerns for Bushnell as he planned and constructed the ''Turtle'' was funding.

Due to colonial efforts to keep the existence of this potential war asset secret from the British, the colonial records concerning the ''Turtle'' are often short and cryptic. Most of the records that do exist concern Bushnell's request for funds. Bushnell met with Jonathan Trumbull, the governor of Connecticut, during 1771 seeking financial support. Trumbull also sent requests to George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of th ...

and Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 18 ...

. Jefferson, who was an inventor himself, was intrigued by the possibilities while Washington remained skeptical of devoting funds from the Continental Army, whose funding was already being stretched. Ultimately, Washington was able to provide some funds possibly due to Trumbull's influence.

Several setbacks plagued the design process. The mine in particular was delayed several times from its expected completion from 1771 to 1776. Piloting the ''Turtle'', moreover, required great physical stamina and coordination. The operator would have to adjust the bilge in order to keep from sinking while providing his own propulsion by use of a crank, which worked a propeller located on the front of the submarine, and direction by use of a lever that would operate and direct a rudder in the back. The cabin also reportedly held air for only thirty minutes of use. Thereafter, the operator would have to surface and replenish the air through a ventilator. Obviously, training would be needed in order to ensure the project's success due to the complex nature of the machine. "The boat was moved from Ezra's farm on the Westbrook Road to what is now Ayer's Point in Old Saybrook on the Connecticut River," writes historian Lincoln Diamant. Bushnell had a Yale connection here that allowed him to run trials in secrecy. Bushnell did the initial testing of his submarine here, choosing his brother, Ezra, as the pilot. Despite Bushnell's insistence on secrecy surrounding his work, news of it quickly made its way to the British, abetted by a Loyalist spy working for New York Congressman James Duane

James Duane (February 6, 1733 – February 1, 1797) was an American Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father, attorney, jurist, and American Revolutionary War, American Revolutionary leader from New York (state), New York. He serve ...

.

In August 1776, Bushnell asked General Samuel Holden Parsons

Samuel Holden Parsons (May 14, 1737 – November 17, 1789) was an American lawyer, jurist, generalHeitman, ''Officers of the Continental Army'', 428. in the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War, and a pioneer to the Ohio Countr ...

for volunteers to operate ''Turtle'', because his brother Ezra, who had been its operator during earlier trials at Ayer's Point on the Connecticut river, was taken ill.

Three men were chosen, and the submersible was taken to Long Island Sound for training and further trials. While these trials went on, the British gained control of western Long Island in the August 27 Battle of Long Island

The Battle of Long Island, also known as the Battle of Brooklyn and the Battle of Brooklyn Heights, was an action of the American Revolutionary War fought on August 27, 1776, at the western edge of Long Island in present-day Brooklyn, New Yo ...

. Since the British now controlled the harbor, ''Turtle'' was transported overland from New Rochelle to the Hudson River. After two weeks of training, ''Turtle'' was towed to New York, and its new operator, Sgt. Ezra Lee

Ezra Lee (August 1749 – October 29, 1821) was an American colonial soldier, best known for commanding and operating the one-man ''Turtle'' submarine.

Early life and career

Lee was born in Lyme, Connecticut. On January 1, 1776, he enlisted in ...

, prepared to attack the flagship of the blockade squadron, .

Destroying this symbol of British naval power by means of a submarine would at least be a blow to British morale and, perhaps, threaten the British blockade and control of New York Harbor

New York Harbor is at the mouth of the Hudson River where it empties into New York Bay near the East River tidal estuary, and then into the Atlantic Ocean on the east coast of the United States. It is one of the largest natural harbors in t ...

. The plan was to have Lee surface just behind ''Eagle''s rudder and use a screw to attach an explosive to the ship's hull. Once attached, Lee would re-enter the water and make his getaway.

Attack on ''Eagle''

At 11:00 pm on September 6, 1776, Sgt. Lee piloted the submersible toward Admiral Richard Howe's flagship, , then moored off

At 11:00 pm on September 6, 1776, Sgt. Lee piloted the submersible toward Admiral Richard Howe's flagship, , then moored off Governors Island

Governors Island is a island in New York Harbor, within the New York City borough of Manhattan. It is located approximately south of Manhattan Island, and is separated from Brooklyn to the east by the Buttermilk Channel. The National Park ...

.

On that night, Lee maneuvered the small craft out to the anchorage. It took two hours to reach his destination, as it was hard work manipulating the hand-operated controls and foot pedals to propel the submersible into position. Adding to his difficulties was a fairly strong current and the darkness creeping overhead, which made visibility difficult.

The plan failed. Lee began his mission with only twenty minutes of air, not to mention the complications of operating the craft. The darkness, the speed of the currents, and the added complexities all combined to thwart Lee's plan. Once surfaced, Lee lit the fuse on the explosive and tried multiple times to stab the device into the underside of the ship. Unfortunately, after several attempts Lee was not able to pierce ''Eagle''s hull and abandoned the operation as the timer on the explosive was due to go off and he feared getting caught at dawn. A popular story held that he failed due to the copper

Copper is a chemical element with the symbol Cu (from la, cuprum) and atomic number 29. It is a soft, malleable, and ductile metal with very high thermal and electrical conductivity. A freshly exposed surface of pure copper has a pinkis ...

lining covering the ship's hull. The Royal Navy had recently begun installing copper sheathing

Copper sheathing is the practice of protecting the under-water hull of a ship or boat from the corrosive effects of salt water and biofouling through the use of copper plates affixed to the outside of the hull. It was pioneered and developed by ...

on the bottoms of their warships to protect from damage by shipworm

The shipworms are marine bivalve molluscs in the family Teredinidae: a group of saltwater clams with long, soft, naked bodies. They are notorious for boring into (and commonly eventually destroying) wood that is immersed in sea water, including ...

s and other marine life, however the lining was paper-thin and could not have stopped Lee from drilling through it. Bushnell believed Lee's failure was probably due to an iron plate connected to the ship's rudder hinge.Schecter, p. 174 When Lee attempted another spot in the hull, he was unable to stay beneath the ship, and eventually abandoned the attempt. It seems more likely that he was suffering from fatigue and carbon dioxide

Carbon dioxide (chemical formula ) is a chemical compound made up of molecules that each have one carbon atom covalently double bonded to two oxygen atoms. It is found in the gas state at room temperature. In the air, carbon dioxide is transpar ...

inhalation, which made him confused and unable to properly carry out the process of drilling through the ''Eagle''s hull. Lee reported British soldiers on Governors Island spotted the submersible and rowed out to investigate. He then released the charge (which he called a "torpedo", the prevailing term for underwater explosive devices prior to about 1890), "expecting that they would seize that likewise, and thus all would be blown to atoms." Suspicious of the drifting charge, the British retreated back to the island. Lee reported that the charge drifted into the East River

The East River is a saltwater tidal estuary in New York City. The waterway, which is actually not a river despite its name, connects Upper New York Bay on its south end to Long Island Sound on its north end. It separates the borough of Queens ...

, where it exploded "with tremendous violence, throwing large columns of water and pieces of wood that composed it high into the air." It was the first recorded use of a submarine to attack a ship; however, the only records documenting it are American. British records contain no accounts of an attack by a submarine or any reports of explosions on the night of the supposed attack on ''Eagle''.Compton-Hall, pp. 32–40

According to British naval historian Richard Compton-Hall, the problems of achieving neutral buoyancy

Neutral buoyancy occurs when an object's average density is equal to the density of the fluid in which it is immersed, resulting in the buoyant force balancing the force of gravity that would otherwise cause the object to sink (if the body's dens ...

would have rendered the vertical propeller useless. The route ''Turtle'' would have had to take to attack ''Eagle'' was slightly across the tidal stream which would, in all probability, have resulted in Lee becoming exhausted. In the face of these and other problems, Compton-Hall suggests the entire story was fabricated as disinformation and morale-boosting propaganda, and if Lee did carry out an attack it was in a covered rowing boat rather than ''Turtle''.

Despite ''Turtle''s failure, Washington called Bushnell "a Man of great Mechanical Powers, fertile of invention and a master in execution." In retrospect, Washington observed in a letter to Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 18 ...

, " ushnellcame to me in 1776 recommended by Governor Trumbull (now dead) and other respectable characters…Although I wanted faith myself, I furnished him with money, and other aids to carry it into execution. He laboured for some time ineffectually and, though the advocates for his scheme continued sanguine, he never did succeed. One accident or another was always intervening. I then thought, and still think, that it was an effort of genius; but that a combination of too many things were requisite…"

''Turtle''s attack on ''Eagle'' reflected both the ingenuity of American forces after the fall of New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

and the tendency of the weaker belligerent to adopt and embrace new, sometimes radical, technologies. "What astonishment it will produce and what advantages may be made…if it succeeds, remore easy for you to conceive than for me to describe," physician Benjamin Gale wrote to Silas Deane

Silas Deane (September 23, 1789) was an American merchant, politician, and diplomat, and a supporter of American independence. Deane served as a delegate to the Continental Congress, where he signed the Continental Association, and then became the ...

less than a year before ''Turtles mission.

The submarine's ultimate fate is not known, although it is believed that after the British took New York, the ''Turtle'' was destroyed to prevent her from falling into enemy hands.

Aftermath

On October 5, Sergeant Lee again went out in an attempt to attach the charge to afrigate

A frigate () is a type of warship. In different eras, the roles and capabilities of ships classified as frigates have varied somewhat.

The name frigate in the 17th to early 18th centuries was given to any full-rigged ship built for speed and ...

anchored off Manhattan. He reported the ship's watch spotted him, so he abandoned the attempt. The submarine was sunk some days later by the British aboard its tender vessel near Fort Lee, New Jersey

Fort Lee is a borough at the eastern border of Bergen County, in the U.S. state of New Jersey, situated along the Hudson River atop the Palisades.

As of the 2020 U.S. census, the borough's population was 40,191. As of the 2010 U.S. census, th ...

. Bushnell reported salvaging ''Turtle'', but its final fate is unknown. Washington called the attempt "an effort of genius", but "a combination of too many things was requisite" for such an attempt to succeed.

Following ''Turtles abortive attack in New York Harbor, Bushnell continued his work in underwater explosives. In 1777, he devised mines to be towed for an attack on HMS ''Cerberus'' near New London harbor and to be floated down the Delaware River in an attempt to interrupt the British fleet off Philadelphia. Both attempts failed, and the latter occupied a brief, if farcical, place in the literature of the war. Francis Hopkinson

Francis Hopkinson (October 2,Hopkinson was born on September 21, 1737, according to the then-used Julian calendar (old style). In 1752, however, Great Britain and all its colonies adopted the Gregorian calendar (new style) which moved Hopkinson's ...

's poem "Battle of the Kegs

''The Battle of the Kegs'' is a ballad written by Francis Hopkinson dramatizing an attempted attack upon the British Fleet in the harbor of Philadelphia on January 6, 1778 during the American Revolutionary War.

The kegs themselves were made by Co ...

," captured the surprising, if futile, venture: "The soldier flew, the sailor too, and, scared almost to death, sir, wore out their shoes to spread the news, and ran till out of breath, sir."

When the Connecticut government refused to fund further underwater project, Bushnell joined the Continental army as a captain-lieutenant of sappers and miners, and served with distinction for several years the Hudson River in New York. After the war, Bushnell drifted into obscurity. He visited France for several years, then moved to Georgia in 1795 under the assumed name of David Bush, where he taught school and practiced medicine. He died largely unknown in Georgia in 1824. After the war, inventors such as Robert Fulton

Robert Fulton (November 14, 1765 – February 24, 1815) was an American engineer and inventor who is widely credited with developing the world's first commercially successful steamboat, the (also known as ''Clermont''). In 1807, that steamboat ...

were influenced by Bushnell's designs in the development of underwater explosives.

Despite ''Turtles shortcomings, Bushnell's invention marked an important milestone in submarine technology. The American inventor Robert Fulton conceived of his submarine ''Nautilus'' in the first years of the nineteenth century and took it to Europe when the United States proved largely uninterested in the design. During the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

, the Confederate States of America

The Confederate States of America (CSA), commonly referred to as the Confederate States or the Confederacy was an unrecognized breakaway republic in the Southern United States that existed from February 8, 1861, to May 9, 1865. The Confeder ...

, faced with a similar situation to that of the colonies during the War of Independence, developed an operational submarine CSS ''H.L. Hunley'', whose destruction of the USS ''Housatonic'' in Charleston Harbor

The Charleston Harbor is an inlet (8 sq mi/20.7 km²) of the Atlantic Ocean at Charleston, South Carolina. The inlet is formed by the junction of Ashley and Cooper rivers at . Morris and Sullivan's Islands shelter the entrance. Charleston H ...

in February 1864 was the first successful submarine attack in history. By the early-twentieth century, the world's navies were beginning to adopt submarines in larger numbers. Like Bushnell's design, these boats mimicked the natural forms of marine animals in their hull designs. As one contemporary historian of submarines observed in 1901, the evolution of modern submarine evolved from the whale, which he deemed a "submarine made by nature out of a mammal."

While Bushnell's name is not generally well-known, he is often credited with revolutionizing naval warfare from below. Bushnell's ''Turtle'' created a military vantage point unseen prior to the Revolutionary Wara view from under the war-stricken waters. As historian Alex Roland argues, Bushnell's legacy as an inventor was also burnished by American writers and historians who in the early nineteenth-century lionized Bushnell and his submarine. To a new postwar generation of Americans, he seemed "the ingenious patriot who invented the submarine that terrified the British." Bushnell joined the ranks of American inventors of the era such as Eli Whitney

Eli Whitney Jr. (December 8, 1765January 8, 1825) was an American inventor, widely known for inventing the cotton gin, one of the key inventions of the Industrial Revolution that shaped the economy of the Antebellum South.

Although Whitney hi ...

and Robert Fulton. These men served as national heroes to Americans who advocated for technological advances and idolized the men making them. "Whether the motives were military pride or scientific nationalism," Roland contends, "it was important to Americans in the first half century after the Revolution to look upon Bushnell's submarine as an American original.

Yet, while the ''Turtle'' occupies a prominent place in the history of technology and military history, Roland's scholarship points to other technological precedence that almost certainly influenced Bushnell's design. Roland points to Denis Papin

Denis Papin FRS (; 22 August 1647 – 26 August 1713) was a French physicist, mathematician and inventor, best known for his pioneering invention of the steam digester, the forerunner of the pressure cooker and of the steam engine.

Early lif ...

, a French physician, physicist, and member of the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

and the French Academy of Sciences

The French Academy of Sciences (French: ''Académie des sciences'') is a learned society, founded in 1666 by Louis XIV of France, Louis XIV at the suggestion of Jean-Baptiste Colbert, to encourage and protect the spirit of French Scientific me ...

, whose two submarines may well have served as a model for Bushnell. "The submarine Bushnell designed and built... had features peculiar to both of Papin's versions." As historian of technology Carroll Purcell argues, such trans-Atlantic technology cross-fertilization was hardly exceptional in this era.

Since the ''Turtles emergence over two centuries ago, the international playing field has leveled. The monopoly over submersible technology once held by the United States was lost over time as other navies around the world modernized and adopted submarine warfare. From the innovations of John Holland in the early twentieth century to the German U-boat

U-boats were naval submarines operated by Germany, particularly in the First and Second World Wars. Although at times they were efficient fleet weapons against enemy naval warships, they were most effectively used in an economic warfare role ...

campaigns of the World Wars, and the nuclear-powered ICBM

An intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) is a ballistic missile with a range greater than , primarily designed for nuclear weapons delivery (delivering one or more thermonuclear warheads). Conventional, chemical, and biological weapons c ...

submarines of the Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because the ...

, modern navies embraced the submarine, first, for missions of reconnaissance and commerce-raiding, but, increasingly, in offensive, attack roles. In the postwar era, the submarine has become a central component of modern navies. Submarine usage has gone far beyond Bushnell's conception of lifting naval blockades designed to bleed a country dry of their imports to become an essential arm of offensive naval warfare and power projection.

Replicas

The ''Turtle'' was the first submersible vessel used for combat and led to the development of what we know today as the modernsubmarine

A submarine (or sub) is a watercraft capable of independent operation underwater. It differs from a submersible, which has more limited underwater capability. The term is also sometimes used historically or colloquially to refer to remotely op ...

, forever changing underwater warfare and the face of naval warfare. As such, the ''Turtle'' has been replicated many times to show new audience the roots of submarine technology, how much it has changed, and the influence it has had on modern submarines. By the 1950s, historian of technology Brooke Hindle credited the ''Turtle'' as "the greatest of the wartime inventions." The ''Turtle'' remains a source of national as well as regional pride, which led to the construction of several replicas, a number of which exist in Bushnell's home state of Connecticut

Connecticut () is the southernmost state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It is bordered by Rhode Island to the east, Massachusetts to the north, New York to the west, and Long Island Sound to the south. Its cap ...

. As Benjamin Gale noted in 1775, the vessel was "constructed with great simplicity," and it has thus inspired at least four replicas. Many of these followed the designs set down by Bushnell, with "precise and comprehensive descriptions of his submarine," which aided the replication process.

The vessel was a source of particular pride in Connecticut. In 1976, a replica of ''Turtle'' was designed by Joseph Leary

Joseph Michael Leary (1831–20 October 1881), was an Australian politician and solicitor, serving as a member of the New South Wales Legislative Assembly.

Early life and education

Leary was born in 1831 in Campbelltown, to John Leary and Cathe ...

and constructed by Fred Frese as a project marking the United States Bicentennial

The United States Bicentennial was a series of celebrations and observances during the mid-1970s that paid tribute to historical events leading up to the creation of the United States of America as an independent republic. It was a central event ...

. It was christened by Connecticut's governor, Ella Grasso

Ella Rosa Giovianna Oliva Grasso (née Tambussi; May 10, 1919 – February 5, 1981) was an American politician and member of the Democratic Party who served as the 83rd Governor of Connecticut from January 8, 1975, to December 31, 1980, after r ...

, and later tested in the Connecticut River

The Connecticut River is the longest river in the New England region of the United States, flowing roughly southward for through four states. It rises 300 yards (270 m) south of the U.S. border with Quebec, Canada, and discharges at Long Island ...

. This replica is owned by the Connecticut River Museum

The Connecticut River Museum is a U.S. educational and cultural institution based at Steamboat Dock in Essex, Connecticut that focuses on the marine environment and maritime heritage of the Connecticut River Valley.

The three-story Connecticut R ...

.

In 2002, Rick and Laura Brown, two sculptors from Massachusetts

Massachusetts (Massachusett language, Massachusett: ''Muhsachuweesut assachusett writing systems, məhswatʃəwiːsət'' English: , ), officially the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, is the most populous U.S. state, state in the New England ...

, along with Massachusetts College of Art and Design

Massachusetts College of Art and Design, branded as MassArt, is a public college of visual and applied art in Boston, Massachusetts. Founded in 1873, it is one of the nation’s oldest art schools, the only publicly funded independent art school ...

students and faculty, constructed another replica. The Browns set out to gain a better understanding of human ingenuity while keeping Bushnell's design, materials, and technique authentic. "With it, Yankee ingenuity was born," observed Rick Brown, referring to the latest in a long line of commemoration that perceived the ''Turtle'' as something authentically American. Of the temptation to use synthetic and ahistorical materials, Rob Duarte, a MassArts student observed, "It was always a temptation to use silicone

A silicone or polysiloxane is a polymer made up of siloxane (−R2Si−O−SiR2−, where R = organic group). They are typically colorless oils or rubber-like substances. Silicones are used in sealants, adhesives, lubricants, medicine, cooking ...

to seal the thing," says Rob Duarte, a MassArt student. "Then you realized that someone else had to figure this out with the same limited resources that we were using. That's just an interesting way to learn. You can't do it any other way than by actually doing it." The outer shell of the replica was hollowed, using controlled fire, from a Sitka spruce

''Picea sitchensis'', the Sitka spruce, is a large, coniferous, evergreen tree growing to almost tall, with a trunk diameter at breast height that can exceed 5 m (16 ft). It is by far the largest species of spruce and the fifth-larg ...

. The log was in diameter and shipped from British Columbia

British Columbia (commonly abbreviated as BC) is the westernmost province of Canada, situated between the Pacific Ocean and the Rocky Mountains. It has a diverse geography, with rugged landscapes that include rocky coastlines, sandy beaches, ...

. This replica took twelve days to build and was successfully submerged in water. In 2003, it was tested in an indoor test tank at the United States Naval Academy

The United States Naval Academy (US Naval Academy, USNA, or Navy) is a federal service academy in Annapolis, Maryland. It was established on 10 October 1845 during the tenure of George Bancroft as Secretary of the Navy. The Naval Academy ...

. Lew Nuckols, a professor of Ocean Engineering

Marine engineering is the engineering of boats, ships, submarines, and any other marine vessel. Here it is also taken to include the engineering of other ocean systems and structures – referred to in certain academic and professional circl ...

at USNA, made ten dives, noting "you feel very isolated from the outside world. If you had any sense of claustrophobia

Claustrophobia is the fear of confined spaces. It can be triggered by many situations or stimuli, including elevators, especially when crowded to capacity, windowless rooms, and hotel rooms with closed doors and sealed windows. Even bedrooms with ...

it would not be a very good experience."

In 2003, Roy Manstan, Fred Frese, and the Naval Underwater Warfare Center partnered with students from Old Saybrook High School in Connecticut on a four-year project called The Turtle Project, to construct their own working replica, which they completed and launched in 2007.

On August 3, 2007 three men were stopped by police while escorting and piloting a replica based on the ''Turtle'' within 200 feet (61 m) of RMS ''Queen Mary 2'', then docked at the cruise ship terminal in Red Hook, Brooklyn

Red Hook is a neighborhood in northwestern Brooklyn, New York City, New York, within the area once known as South Brooklyn. It is located on a peninsula projecting into the Upper New York Bay and is bounded by the Gowanus Expressway and the Car ...

. The replica was created by New York artist Philip "Duke" Riley and two residents of Rhode Island

Rhode Island (, like ''road'') is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It is the List of U.S. states by area, smallest U.S. state by area and the List of states and territories of the United States ...

, one of whom claimed to be a descendant of David Bushnell. Riley claimed that he wanted to film himself next to the ''Queen Mary 2'' for his upcoming gallery show. Riley's was not an exact replica, however, measuring tall and made of cheap plywood

Plywood is a material manufactured from thin layers or "plies" of wood veneer that are glued together with adjacent layers having their wood grain rotated up to 90 degrees to one another. It is an engineered wood from the family of manufactured ...

then coated with fiberglass

Fiberglass (American English) or fibreglass (Commonwealth English) is a common type of fiber-reinforced plastic using glass fiber. The fibers may be randomly arranged, flattened into a sheet called a chopped strand mat, or woven into glass cloth ...

. Its portholes and hatch were collected from a marine salvage company. He also installed pumps to allow him to add or remove water for ballast. Riley christened his vessel ''Acorn'', to note the deviation from Bushnell's original design. The vessel, reported the New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid d ...

, "resembled something out of Jules Verne

Jules Gabriel Verne (;''Longman Pronunciation Dictionary''. ; 8 February 1828 – 24 March 1905) was a French novelist, poet, and playwright. His collaboration with the publisher Pierre-Jules Hetzel led to the creation of the ''Voyages extraor ...

by way of Huck Finn

Huck may refer to:

Characters

* Huckleberry Finn, a character in four novels by Mark Twain

* Huckleberry Hound, a cartoon character created by animation studio Hanna-Barbera

* Huck, a character on ''Scandal (TV series), Scandal''

* Huck, a charac ...

, manned by cast members from ' Jackass.' The Coast Guard

A coast guard or coastguard is a maritime security organization of a particular country. The term embraces wide range of responsibilities in different countries, from being a heavily armed military force with customs and security duties to ...

issued Riley a citation for having an unsafe vessel, and for violating the security zone around ''Queen Mary 2''. The NYPD

The New York City Police Department (NYPD), officially the City of New York Police Department, established on May 23, 1845, is the primary municipal law enforcement agency within the City of New York, the largest and one of the oldest in ...

also impounded the submarine. Police Commissioner Raymond W. Kelly

Raymond Walter Kelly (born September 4, 1941) is the longest serving Commissioner in the history of the New York City Police Department (NYPD) and the first man to hold the post for two non-consecutive tenures. According to its website, Kelly � ...

, calling this an incident of "marine mischief" assured the public that this was simply an art project and did not, in fact, represent a terrorist threat to the passenger ship.

In 2015, the replica built by Manstan and Frese in 2007 for The Turtle Project was acquired by Privateer Media and used in the television series '' TURN: Washington's Spies.''TURN: Turtle Submarine The submarine was shipped to Richmond, VA where it underwent a full refit and was relaunched for film use in the water. Additional full-scale interior and exterior models were also made by AMC as part of the production.

Also in 2015, Privateer Media used The Turtle Project replica for the Travel Channel series Follow Your Past, hosted by Alison Stewart. Filming took place in August where the submarine was launched with a tether in the Connecticut River in the town of Essex, CT.

Connecticut River Museum

The Connecticut River Museum is a U.S. educational and cultural institution based at Steamboat Dock in Essex, Connecticut that focuses on the marine environment and maritime heritage of the Connecticut River Valley.

The three-story Connecticut R ...

File:Bushnell Turtle model US Navy Submarine Museum.jpg, Cutaway replica at the Submarine Force Library and Museum

The United States Navy Submarine Force Library and Museum is located on the Thames River in Groton, Connecticut. It is the only submarine museum managed exclusively by the Naval History & Heritage Command division of the Navy, and this makes it a ...

, Groton, Connecticut

File:Bushnell Turtle.JPG, Cutaway replica at the Oceanographic Museum

The Oceanographic Museum (''Musée océanographique'') is a museum of marine sciences in Monaco-Ville, Monaco.

This building is part of the Institut océanographique, which is committed to sharing its knowledge of the oceans.

History

The ...

, Monaco

File:Duke Riley The Acorn.jpg, 2007 functional replica created by Philip "Duke" Riley

Footnotes

References

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * Roland, Alex. "Bushnell's Submarine: American Original or European Import."''Technology and Culture'' 18 (April 1977): 157–74. * Kennedy, Randy. "An Artist and His Sub Surrender in Brooklyn." ''The New York Times,'' August 4, 2007. * Gidwitz, Tom. "The Turtle Dives Again." ''Archaeology'', May/June 2005. * Darian, Steven, and Amy Price. "David Bushnell: An Inventor Describes His Invention." ''Technical Communication'', vol. 35, no. 4, 1988, p. 344, * * {{Authority control Submarines of the United States Ships built in Connecticut 1775 ships Age of Sail submarines of the United States Connecticut in the American Revolution New York (state) in the American Revolution American Revolutionary War ships of the United States Shipwrecks of the New York (state) coast Maritime incidents in 1776 Hand-cranked submarines 1775 in the Thirteen Colonies