Troy Township Hall At Steam Corners on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Troy ( el, Τροία and

The main literary work set at Troy is the ''

The main literary work set at Troy is the ''

Troy I was a small village founded around 3000 BC. In this era, the site was adjacent to a shallow bay which gradually silted up over the subsequent millennia. The village consisted of stone and mudbrick houses which were attached to one another and surrounded by stone walls. Finds from this layer include dark colored handmade pottery and artifacts made of copper. It had cultural similarities to Aegean sites such as

Troy I was a small village founded around 3000 BC. In this era, the site was adjacent to a shallow bay which gradually silted up over the subsequent millennia. The village consisted of stone and mudbrick houses which were attached to one another and surrounded by stone walls. Finds from this layer include dark colored handmade pottery and artifacts made of copper. It had cultural similarities to Aegean sites such as

Troy continued to be occupied between 2300 BC and 1750 BC. However, little is known about these several layers due to Schliemann's careless excavation practices. In order to fully excavate the citadel of Troy II, he destroyed most remains from this period without first documenting them. These settlements appear to have been smaller and poorer than previous ones, though this interpretation could be merely the result of gaps in the surviving evidence. The settlements included a dense residential neighborhood in the citadel. Walls from Troy II may have been reused as part of Troy III. By the period of Troy V, the city had once again expanded outside the citadel to the west. Troy IV sees the introduction of domed ovens. In Troy V, artifacts include Anatolian-style "red-cross bowls" as well as imported

Troy continued to be occupied between 2300 BC and 1750 BC. However, little is known about these several layers due to Schliemann's careless excavation practices. In order to fully excavate the citadel of Troy II, he destroyed most remains from this period without first documenting them. These settlements appear to have been smaller and poorer than previous ones, though this interpretation could be merely the result of gaps in the surviving evidence. The settlements included a dense residential neighborhood in the citadel. Walls from Troy II may have been reused as part of Troy III. By the period of Troy V, the city had once again expanded outside the citadel to the west. Troy IV sees the introduction of domed ovens. In Troy V, artifacts include Anatolian-style "red-cross bowls" as well as imported

The citadel was enclosed by massive walls. Present-day visitors can see the limestone base of these walls, which are thick and tall. However, during the Bronze Age they would have been overlaid with wood and mudbrick superstructures, reaching a height over . The walls were built in a "sawtooth" style commonly found at Mycenaean citadels, divided into - segments which joined with one another at an angle. The walls also have a notable slope, similar to those at other sites including

The citadel was enclosed by massive walls. Present-day visitors can see the limestone base of these walls, which are thick and tall. However, during the Bronze Age they would have been overlaid with wood and mudbrick superstructures, reaching a height over . The walls were built in a "sawtooth" style commonly found at Mycenaean citadels, divided into - segments which joined with one another at an angle. The walls also have a notable slope, similar to those at other sites including

After the destruction of Troy VIIa around 1180 BC, the city was rebuilt as Troy VIIb. Older structures were again reused, including Troy VI's citadel walls. Its first phase, Troy VIIb1, is largely a continuation of Troy VIIa. Residents continued using wheel-made Grey Ware pottery alongside a new handmade style sometimes known as "barbarian ware". Imported Mycenaean-style pottery attests to some continuing foreign trade.

One of the most striking finds from Troy VIIb1 is a

After the destruction of Troy VIIa around 1180 BC, the city was rebuilt as Troy VIIb. Older structures were again reused, including Troy VI's citadel walls. Its first phase, Troy VIIb1, is largely a continuation of Troy VIIa. Residents continued using wheel-made Grey Ware pottery alongside a new handmade style sometimes known as "barbarian ware". Imported Mycenaean-style pottery attests to some continuing foreign trade.

One of the most striking finds from Troy VIIb1 is a

With the rise of critical history, Troy and the Trojan War were largely consigned to legend.

Those who departed from this general view became the first archaeologists at Troy.

Early modern travellers in the 16th and 17th centuries, including

With the rise of critical history, Troy and the Trojan War were largely consigned to legend.

Those who departed from this general view became the first archaeologists at Troy.

Early modern travellers in the 16th and 17th centuries, including

In 1868, German businessman

In 1868, German businessman

. Schuchhardt, "Schliemans Excavations: An archaeological and historical study", MacMillan and Co, London, 1891 In 1871–1873 and 1878–1879, 1882 and 1890 (the later two joined by Wilhelm Dörpfeld), he discovered the ruins of a series of ancient cities dating from the

The Turkish government created the Historical National Park at Troy on September 30, 1996. It contains to include Troy and its vicinity, centered on Troy. The purpose of the park is to protect the historical sites and monuments within it, as well as the environment of the region. In 1998 the park was accepted as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

In 2015 a Term Development Revision Plan was applied to the park. Its intent was to develop the park into a major tourist site. Plans included marketing research to determine the features most of interest to the public, the training of park personnel in tourism management, and the construction of campsites and facilities for those making day trips. These latter were concentrated in the village of Tevfikiye, which shares Troy Ridge with Troy.

The Turkish government created the Historical National Park at Troy on September 30, 1996. It contains to include Troy and its vicinity, centered on Troy. The purpose of the park is to protect the historical sites and monuments within it, as well as the environment of the region. In 1998 the park was accepted as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

In 2015 a Term Development Revision Plan was applied to the park. Its intent was to develop the park into a major tourist site. Plans included marketing research to determine the features most of interest to the public, the training of park personnel in tourism management, and the construction of campsites and facilities for those making day trips. These latter were concentrated in the village of Tevfikiye, which shares Troy Ridge with Troy.

Public access to the ancient site is along the road from the vicinity of the museum in Tevfikiye to the east side of Hisarlik. Some parking is available. Typically visitors come by bus, which disembarks its passengers into a large plaza ornamented with flowers and trees and some objects from the excavation. In its square is a large wooden horse monument, with a ladder and internal chambers for use of the public. Bordering the square is the gate to the site. The public passes through turnstiles. Admission is usually not free. Within the site, the visitors tour the features on dirt roads or for access to more precipitous features on railed boardwalks. There are many overlooks with multilingual boards explaining the feature. Most are outdoors, but a permanent canopy covers the site of an early megaron and wall.

Public access to the ancient site is along the road from the vicinity of the museum in Tevfikiye to the east side of Hisarlik. Some parking is available. Typically visitors come by bus, which disembarks its passengers into a large plaza ornamented with flowers and trees and some objects from the excavation. In its square is a large wooden horse monument, with a ladder and internal chambers for use of the public. Bordering the square is the gate to the site. The public passes through turnstiles. Admission is usually not free. Within the site, the visitors tour the features on dirt roads or for access to more precipitous features on railed boardwalks. There are many overlooks with multilingual boards explaining the feature. Most are outdoors, but a permanent canopy covers the site of an early megaron and wall.

In 2018 the

In 2018 the

chliemann, Heinrich. Ilios: The City and Country of the Trojans: the Results of Researches and Discoveries on the Site of Troy and Throughout the Troad in the Years 1871-72-73-78-79: Including an Autobiography of the Author. J. Murray, 1880 * ** ** ** * ** **

The Many Myths of the Man Who ‘Discovered’—and Nearly Destroyed—Troy - Smithsonian Magazine - Meilan Solly - May 17, 2022

{{Authority control Troy, Ancient Greek geography Ancient Greek archaeological sites in Turkey Archaeological sites in the Marmara Region Destroyed cities Former populated places in Turkey Geography of Çanakkale Province History of Çanakkale Province Locations in Greek mythology National parks of Turkey Populated places established in the 3rd millennium BC Tourist attractions in Çanakkale Province World Heritage Sites in Turkey 30th-century BC establishments Ezine District Razed cities Late Bronze Age collapse Former kingdoms

Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

: Troia, Hittite: 𒋫𒊒𒄿𒊭 ''Truwiša'') or Ilion ( el, Ίλιον and Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

: Ilium, Hittite: 𒃾𒇻𒊭 ''Wiluša'') was an ancient city located at Hisarlik

Hisarlik (Turkish: ''Hisarlık'', "Place of Fortresses"), often spelled Hissarlik, is the Turkish name for an ancient city located in what is known historically as Anatolia.A compound of the noun, hisar, "fortification," and the suffix -lik. The s ...

in present-day Turkey

Turkey ( tr, Türkiye ), officially the Republic of Türkiye ( tr, Türkiye Cumhuriyeti, links=no ), is a list of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country located mainly on the Anatolia, Anatolian Peninsula in Western Asia, with ...

, south-west of Çanakkale

Çanakkale (pronounced ), ancient ''Dardanellia'' (), is a city and seaport in Turkey in Çanakkale province on the southern shore of the Dardanelles at their narrowest point. The population of the city is 195,439 (2021 estimate).

Çanakkale is ...

and about miles east of the Aegean Sea

The Aegean Sea ; tr, Ege Denizi (Greek language, Greek: Αιγαίο Πέλαγος: "Egéo Pélagos", Turkish language, Turkish: "Ege Denizi" or "Adalar Denizi") is an elongated embayment of the Mediterranean Sea between Europe and Asia. It ...

. It is known as the setting for the Greek myth

A major branch of classical mythology, Greek mythology is the body of myths originally told by the ancient Greeks, and a genre of Ancient Greek folklore. These stories concern the origin and nature of the world, the lives and activities of ...

of the Trojan War

In Greek mythology, the Trojan War was waged against the city of Troy by the Achaeans (Greeks) after Paris of Troy took Helen from her husband Menelaus, king of Sparta. The war is one of the most important events in Greek mythology and has ...

.

In Ancient Greek literature, Troy is portrayed as a powerful kingdom of the Heroic Age, a mythic era when monsters roamed the earth and gods interacted directly with humans. The city was said to have ruled the Troad

The Troad ( or ; el, Τρωάδα, ''Troáda'') or Troas (; grc, Τρῳάς, ''Trōiás'' or , ''Trōïás'') is a historical region in northwestern Anatolia. It corresponds with the Biga Peninsula ( Turkish: ''Biga Yarımadası'') in the Ç ...

until the Trojan War led to its complete destruction at the hands of the Greeks. The story of its destruction was one of the cornerstones of Greek mythology and literature, featuring prominently in the ''Iliad

The ''Iliad'' (; grc, Ἰλιάς, Iliás, ; "a poem about Ilium") is one of two major ancient Greek epic poems attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest extant works of literature still widely read by modern audiences. As with the ''Odysse ...

'' and the ''Odyssey

The ''Odyssey'' (; grc, Ὀδύσσεια, Odýsseia, ) is one of two major Ancient Greek literature, ancient Greek Epic poetry, epic poems attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest extant works of literature still widely read by moder ...

'', and referenced in numerous other poems and plays. Its legacy played a large role in Greek society, with many prominent families claiming descent from those who had fought there. In the Archaic era, a new city was built at the site where legendary Troy was believed to have stood. In the Classical era

Classical antiquity (also the classical era, classical period or classical age) is the period of cultural history between the 8th century BC and the 5th century AD centred on the Mediterranean Sea, comprising the interlocking civilizations of ...

, this city became a tourist destination, where visitors would leave offerings to the legendary heroes.

Until the late 19th century, scholars regarded the Trojan War as entirely legendary. However, starting in 1871, Heinrich Schliemann

Johann Ludwig Heinrich Julius Schliemann (; 6 January 1822 – 26 December 1890) was a German businessman and pioneer in the field of archaeology. He was an advocate of the historicity of places mentioned in the works of Homer and an archaeologi ...

and Frank Calvert

Frank Calvert (1828–1908) was an English expatriate who was a consular official in the eastern Mediterranean region and an amateur archaeologist. He began exploratory excavations on the mound at Hisarlik (the site of the ancient city of Troy) ...

excavated the site of the classical era city, under whose ruins they found the remains of numerous earlier settlements. Several of these layers resemble literary depictions of Troy, leading some scholars to conclude that there is a kernel of truth to the legends. Subsequent excavations by others have added to the modern understanding of the site, though the exact relationship between myth and reality remains unclear.

The archaeological site of Troy consists of nine major layers

Layer or layered may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media

* ''Layers'' (Kungs album)

* ''Layers'' (Les McCann album)

* ''Layers'' (Royce da 5'9" album)

*"Layers", the title track of Royce da 5'9"'s sixth studio album

*Layer, a female Maveric ...

, the earliest dating from the Early Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a historic period, lasting approximately from 3300 BC to 1200 BC, characterized by the use of bronze, the presence of writing in some areas, and other early features of urban civilization. The Bronze Age is the second prin ...

, the latest from the Byzantine

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

era. Each of these layers has sublayers for a total of 46 strata. The mythic city is typically identified with one of the Late Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a historic period, lasting approximately from 3300 BC to 1200 BC, characterized by the use of bronze, the presence of writing in some areas, and other early features of urban civilization. The Bronze Age is the second pri ...

layers, such as Troy VI, Troy VIIa, or Troy VIIb. The archaeological site is open to the public as a tourist destination, and was added to the UNESCO World Heritage

A World Heritage Site is a landmark or area with legal protection by an international convention administered by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). World Heritage Sites are designated by UNESCO for h ...

list in 1998.

Name

InClassical Greek

Ancient Greek includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Dark Ages (), the Archaic peri ...

, the city was referred to as both ''Troia'' () and ''Ilion'' () or ''Ilios'' (). Metrical evidence from the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey

The ''Odyssey'' (; grc, Ὀδύσσεια, Odýsseia, ) is one of two major Ancient Greek literature, ancient Greek Epic poetry, epic poems attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest extant works of literature still widely read by moder ...

'' suggests that the latter was originally pronounced ''Wilios''. These names may date back to the Bronze Age, as suggested by Hittite records which reference a city in northwest Anatolia called or ; in Greek myth, these names were held to originate from the names of the kingdom's founders, Tros

Tros or TROS may refer to:

* 18281 Tros, an asteroid

* Transformer read-only storage, a type of read-only memory

* TROS, a Dutch broadcasting union, originally an acronym for Televisie Radio Omroep Stichting

* Tros (mythology), a figure in Greek ...

and his son Ilus

In Greek mythology, Ilus (; ) is the name of several mythological persons associated directly or indirectly with Troy.

* Ilus, the son of Dardanus, and the legendary founder of Dardania.

* Ilus, the son of Tros, and the legendary founder of Troy ...

.

In Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

, the city was referred to as ' or '.

Legendary Troy

The main literary work set at Troy is the ''

The main literary work set at Troy is the ''Iliad

The ''Iliad'' (; grc, Ἰλιάς, Iliás, ; "a poem about Ilium") is one of two major ancient Greek epic poems attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest extant works of literature still widely read by modern audiences. As with the ''Odysse ...

'', an Archaic-era epic poem

An epic poem, or simply an epic, is a lengthy narrative poem typically about the extraordinary deeds of extraordinary characters who, in dealings with gods or other superhuman forces, gave shape to the mortal universe for their descendants.

...

which tells the story of the final year of the Trojan War. The ''Iliad'' portrays Troy as the capital of a rich and powerful kingdom. In the poem, the city appears to be a major regional power capable of summoning numerous allies to defend it.

The city itself is built on a steep hill, protected by enormous sloping stone walls, rectangular towers, and massive gates whose wooden doors can be bolted shut. The city's streets are broad and well-planned. At the top of the hill is the Temple of Athena as well as King Priam's palace, an enormous structure with numerous rooms around an inner courtyard.

In the ''Iliad'', the Achaeans set up their camp near the mouth of the Scamander

Scamander (; also Skamandros ( grc, Σκάμανδρος) or Xanthos () was a river god in Greek mythology.

Etymology

The meaning of this name is uncertain. The second element looks like it is derived from Greek () meaning 'of a man', but t ...

river, where they beached their ships. The city itself stood on a hill across the plain of Scamander, where much of the fighting takes place.

Besides the ''Iliad'', there are references to Troy in the other major work attributed to Homer, the ''Odyssey

The ''Odyssey'' (; grc, Ὀδύσσεια, Odýsseia, ) is one of two major Ancient Greek literature, ancient Greek Epic poetry, epic poems attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest extant works of literature still widely read by moder ...

'', as well as in other ancient Greek literature (such as Aeschylus

Aeschylus (, ; grc-gre, Αἰσχύλος ; c. 525/524 – c. 456/455 BC) was an ancient Greek tragedian, and is often described as the father of tragedy. Academic knowledge of the genre begins with his work, and understanding of earlier Greek ...

's ''Oresteia''). The Homeric legend of Troy was elaborated by the Roman poet Virgil

Publius Vergilius Maro (; traditional dates 15 October 7021 September 19 BC), usually called Virgil or Vergil ( ) in English, was an ancient Roman poet of the Augustan period. He composed three of the most famous poems in Latin literature: t ...

in his ''Aeneid

The ''Aeneid'' ( ; la, Aenē̆is or ) is a Latin Epic poetry, epic poem, written by Virgil between 29 and 19 BC, that tells the legendary story of Aeneas, a Troy, Trojan who fled the Trojan_War#Sack_of_Troy, fall of Troy and travelled to ...

''. The fall of Troy with the story of the Trojan Horse

The Trojan Horse was a wooden horse said to have been used by the Greeks during the Trojan War to enter the city of Troy and win the war. The Trojan Horse is not mentioned in Homer's ''Iliad'', with the poem ending before the war is concluded, ...

and the sacrifice of Polyxena

In Greek mythology, Polyxena (; Greek: ) was the youngest daughter of King Priam of Troy and his queen, Hecuba. She does not appear in Homer, but in several other classical authors, though the details of her story vary considerably. After the ...

, Priam's youngest daughter, is the subject of a later Greek epic by Quintus Smyrnaeus

Quintus Smyrnaeus (also Quintus of Smyrna; el, Κόϊντος Σμυρναῖος, ''Kointos Smyrnaios'') was a Greek epic poet whose ''Posthomerica'', following "after Homer", continues the narration of the Trojan War. The dates of Quintus Smy ...

("Quintus of Smyrna").

The Greeks and Romans took for a fact the historicity of the Trojan War and the identity of Homeric Troy with a site in Anatolia on a peninsula called the Troad

The Troad ( or ; el, Τρωάδα, ''Troáda'') or Troas (; grc, Τρῳάς, ''Trōiás'' or , ''Trōïás'') is a historical region in northwestern Anatolia. It corresponds with the Biga Peninsula ( Turkish: ''Biga Yarımadası'') in the Ç ...

(Biga Peninsula

Biga Peninsula ( tr, Biga Yarımadası) is a peninsula in Turkey, in the northwest part of Anatolia. It is also known by its ancient name Troad (Troas).

The peninsula is bounded by the Dardanelles Strait and the southwest coast of the Marmara Sea ...

). Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, wikt:Ἀλέξανδρος, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek kingdom of Maced ...

, for example, visited the site in 334 BC and there made sacrifices at tombs associated with the Homeric heroes Achilles

In Greek mythology, Achilles ( ) or Achilleus ( grc-gre, Ἀχιλλεύς) was a hero of the Trojan War, the greatest of all the Greek warriors, and the central character of Homer's ''Iliad''. He was the son of the Nereid Thetis and Peleus, k ...

and Patroclus

In Greek mythology, as recorded in Homer's ''Iliad'', Patroclus (pronunciation variable but generally ; grc, Πάτροκλος, Pátroklos, glory of the father) was a childhood friend, close wartime companion, and the presumed (by some later a ...

.

Archaeological layers

The archaeological site of Troy consists of the hill of Hisarlik and the fields below it to the south. The hill is a tell, composed ofstrata

In geology and related fields, a stratum ( : strata) is a layer of rock or sediment characterized by certain lithologic properties or attributes that distinguish it from adjacent layers from which it is separated by visible surfaces known as ei ...

containing the remains left behind by more than three millennia of human occupation. The primary divisions among layers are designated with Roman numeral

Roman numerals are a numeral system that originated in ancient Rome and remained the usual way of writing numbers throughout Europe well into the Late Middle Ages. Numbers are written with combinations of letters from the Latin alphabet, eac ...

s, Troy I representing the oldest layer and Troy IX representing the most recent. Sublayers are distinguished with lowercase letters (e.g. VIIa and VIIb) and further subdivisions with numbers (e.g. VIIb1 and VIIb2). An additional major layer known as Troy 0 predates the layers which were initially given Roman numeral designations.

The layers have been given relative dates by comparing artifacts found in them to those found at other sites. However, precise absolute dates are not always possible due to limitations in the accuracy of C dating.

:

Troy 0

Troy 0 is a layer discovered later than others, predating what had previously been the earliest at the site. Remains of the layer, first identified in 2019, are not very substantial and its exact dating remains unclear, although Troy 0 was likely no older than . Traces of burns, pottery and wooden beams were found in a layer below the Troy I layer, confirming the existence of the Troy 0 layer.Troy I

Troy I was a small village founded around 3000 BC. In this era, the site was adjacent to a shallow bay which gradually silted up over the subsequent millennia. The village consisted of stone and mudbrick houses which were attached to one another and surrounded by stone walls. Finds from this layer include dark colored handmade pottery and artifacts made of copper. It had cultural similarities to Aegean sites such as

Troy I was a small village founded around 3000 BC. In this era, the site was adjacent to a shallow bay which gradually silted up over the subsequent millennia. The village consisted of stone and mudbrick houses which were attached to one another and surrounded by stone walls. Finds from this layer include dark colored handmade pottery and artifacts made of copper. It had cultural similarities to Aegean sites such as Poliochni

Livadochori ( el, Λιβαδοχώρι) is a village and a community in the Greek island of Lemnos, part of the municipal unit Nea Koutali. In 2011 its population was 237 for the village, and 373 for the community, which includes the village Poli ...

and Thermi

Thermi ( el, Θέρμη) is a Southeastern suburb and a municipality in the Thessaloniki regional unit, Greece. Its population was 53,201 at the 2011 census. It is located over the site of ancient Therma.

Municipality

The municipality Therm ...

, as well as to Anatolian sites such as Bademağacı

Bademağacı is a village on the north part of Antalya, Turkey. It is near the Antalya

la, Attalensis grc, Ἀτταλειώτης

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code = 07xxx

, area_code = (+90) ...

.

Troy II

Troy II was built around 2550 BC. It was twice the size of the preceding city, featuring both a citadel and a lower town. The citadel contained large megaron-style buildings around a courtyard which was likely used for public events such as audiences or religious ceremonies. It was protected by massive stone walls which were topped with mudbrick superstructures. Houses in the lower town were protected by a wooden palisade. Finds from this layer include wheel-made pottery, and numerous items made from precious metals which attest to economic and cultural connections with regions as far as the Balkans and Afghanistan. Troy II was destroyed twice. After the first destruction, the citadel was rebuilt with a dense cluster of small houses. The second destruction took place around 2300 BC, as part of a crisis that affected other sites in the Eastern Mediterranean and the Middle East. Troy II is notable for having been misidentified as Homeric Troy, during initial excavations, because of its massive architecture, treasure hoards, and catastrophic destruction. In particular Schliemann saw Homer's description of Troy's Scaean Gate reflected in Troy II's imposing western gate. However, later excavations demonstrated that the site was a thousand years too old to have coexisted with Mycenaean Greeks.Troy III–V

Minoan

The Minoan civilization was a Bronze Age Aegean civilization on the island of Crete and other Aegean Islands, whose earliest beginnings were from 3500BC, with the complex urban civilization beginning around 2000BC, and then declining from 1450B ...

objects.

Troy VI–VII

Troy VI–VII was a majorLate Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a historic period, lasting approximately from 3300 BC to 1200 BC, characterized by the use of bronze, the presence of writing in some areas, and other early features of urban civilization. The Bronze Age is the second pri ...

city consisting of a steep fortified citadel and a sprawling lower town below it. It was a thriving coastal city with a considerable population, equal in size to second-tier Hittite settlements. It had a distinct Northwest Anatolian culture and extensive foreign contacts, including with Mycenaean Greece

Mycenaean Greece (or the Mycenaean civilization) was the last phase of the Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a historic period, lasting approximately from 3300 BC to 1200 BC, characterized by the use of bronze, the presence of writing in ...

, and its position at the mouth of the Dardanelles

The Dardanelles (; tr, Çanakkale Boğazı, lit=Strait of Çanakkale, el, Δαρδανέλλια, translit=Dardanéllia), also known as the Strait of Gallipoli from the Gallipoli peninsula or from Classical Antiquity as the Hellespont (; ...

has been argued to have given it the function of regional capital, its status protected by treaties.

Aspects of its architecture are consistent with the ''Iliad''Troy VI

Troy VI existed from around 1750 BC to 1300 BC. Its citadel was divided into a series of rising terraces, of which only the outermost is reasonably well-preserved. On this terrace, archaeologists have found the remains of freestanding multistory houses where Trojan elites would have lived. These houses lacked ground-floor windows, and their stone exterior walls mirrored the architecture of the citadel fortifications. However, they otherwise display an eclectic mix of architectural styles, some following the classicmegaron

The megaron (; grc, μέγαρον, ), plural ''megara'' , was the great hall in very early Mycenean and ancient Greek palace complexes. Architecturally, it was a rectangular hall that was surrounded by four columns, fronted by an open, two-co ...

design, others even having irregular floorplans. Some of these houses show potential Aegean influence, one in particular resembling the megaron at Midea Midea may refer to:

* Midea Group (美的集团), a Chinese electrical appliance manufacturer

* Midea, Greece, a Greek town

* Midea (Argolid), a citadel in the town of the same name

* Midea or Mideia, name of four figures in Greek mythology

* '' ...

in the Argolid. Archaeologists believe there may have been a royal palace on the highest terrace, but most Bronze Age remains from the top of the hill were cleared away by classical era building projects.

The citadel was enclosed by massive walls. Present-day visitors can see the limestone base of these walls, which are thick and tall. However, during the Bronze Age they would have been overlaid with wood and mudbrick superstructures, reaching a height over . The walls were built in a "sawtooth" style commonly found at Mycenaean citadels, divided into - segments which joined with one another at an angle. The walls also have a notable slope, similar to those at other sites including

The citadel was enclosed by massive walls. Present-day visitors can see the limestone base of these walls, which are thick and tall. However, during the Bronze Age they would have been overlaid with wood and mudbrick superstructures, reaching a height over . The walls were built in a "sawtooth" style commonly found at Mycenaean citadels, divided into - segments which joined with one another at an angle. The walls also have a notable slope, similar to those at other sites including Hattusa

Hattusa (also Ḫattuša or Hattusas ; Hittite: URU''Ḫa-at-tu-ša'', Turkish: Hattuşaş , Hattic: Hattush) was the capital of the Hittite Empire in the late Bronze Age. Its ruins lie near modern Boğazkale, Turkey, within the great loop of t ...

. These walls were watched over by several rectangular watchtowers, which would also have provided a clear view of Trojan plain and the sea beyond it. The citadel was accessed by five gates, which led into paved and drained cobblestone streets. Some of these gates featured enormous pillars which serve no structural purpose and have been interpreted as religious symbols.

The lower town was built to the south of the citadel, covering an area of roughly 30 hectares. Remains of a dense neighborhood have been found just outside the citadel walls, and traces of other buildings and Late Bronze Age pottery have been found further away. Little of it has been excavated, and few remains are likely to exist; buildings in the lower city are likely to have been made of wood and other perishable materials, and much of the area was built over in the classical and Roman era. The extent of the lower town is evidenced by a defensive ditch cut down to the bedrock and postholes which attest to wooden ramparts or walls which would have once been the outer defense of the city.

The lower city was only discovered in the late 1980s, earlier excavators having assumed that Troy VI occupied only the hill of Hisarlik. Its discovery led to a dramatic reassessment of Troy VI, showing that it was over 16 times larger than had been assumed, and thus a major city with a large population rather than a mere aristocratic residence.

The material culture of Troy VI appears to belong to a distinct Northwest Anatolian cultural group, with influences from the Anatolia, the Aegean, and the Balkans. The primary local pottery styles were wheel-made West Anatolian Gray Ware and Tan ware, local offshoots of an earlier Middle Helladic

Helladic chronology is a relative dating system used in archaeology and art history. It complements the Minoan chronology scheme devised by Sir Arthur Evans for the categorisation of Bronze Age artefacts from the Minoan civilization within a his ...

tradition. Foreign pottery found at the site includes Minoan, Mycenaean, Cypriot, and Levantine items. Local potters also made their own imitations of foreign styles, including Gray Ware and Tan Ware pots made in Mycenaean-style shapes. Although the city appears to have been within the Hittite sphere of influence, no Hittite artifacts have been found in Troy VI. Also notably absent are sculptures and wall paintings, otherwise common features of Bronze Age cities. Troy VI is also notable for its architectural innovations as well as its cultural developments, which included the first evidence of horses at the site. The language spoken in Troy VI is unknown. One candidate is Luwian

The Luwians were a group of Anatolian peoples who lived in central, western, and southern Anatolia, in present-day Turkey, during the Bronze Age and the Iron Age. They spoke the Luwian language, an Indo-European language of the Anatolian sub-fa ...

, an Anatolian language

The Anatolian languages are an extinct branch of Indo-European languages that were spoken in Anatolia, part of present-day Turkey. The best known Anatolian language is Hittite, which is considered the earliest-attested Indo-European language.

...

believed to have been spoken in the general area. Potential evidence comes from a biconvex seal inscribed with the name of a person using Luwian hieroglyph

Anatolian hieroglyphs are an indigenous logographic script native to central Anatolia, consisting of some 500 signs. They were once commonly known as Hittite hieroglyphs, but the language they encode proved to be Luwian, not Hittite, and the te ...

s. However, available evidence is not sufficient to establish that Luwian was actually spoken by the city's population, and a number of alternatives have been proposed.

Troy VI was destroyed around 1300 BC, corresponding with the sublayer known as Troy VIh. Evidence of Troy VIh's destruction includes collapsed masonry, and subsidence

Subsidence is a general term for downward vertical movement of the Earth's surface, which can be caused by both natural processes and human activities. Subsidence involves little or no horizontal movement, which distinguishes it from slope move ...

in the southeast of the citadel, which led its initial excavators to conclude that it was destroyed by an earthquake

An earthquake (also known as a quake, tremor or temblor) is the shaking of the surface of the Earth resulting from a sudden release of energy in the Earth's lithosphere that creates seismic waves. Earthquakes can range in intensity, from ...

. However, alternative hypotheses include an internal uprising as well as a foreign attack.

Troy VIIa

Troy VIIa was the final layer of the Late Bronze Age city. It was built soon after the destruction of Troy VI, seemingly by its previous inhabitants. The builders reused many of the earlier city's surviving structures, notably its citadel wall, which they renovated with additional stone towers and mudbrick breastworks. Numerous small houses were added inside the citadel, filling in formerly open areas. New houses were also built in the lower city, whose area appears to have been greater in Troy VIIa than in Troy VI. In many of these houses, archaeologists found enormous storage jars calledpithoi

Pithos (, grc-gre, πίθος, plural: ' ) is the Greek name of a large storage container. The term in English is applied to such containers used among the civilizations that bordered the Mediterranean Sea in the Neolithic, the Bronze Age and ...

buried in the ground. Troy VIIa seems to have been built by survivors of Troy VI's destruction, as evidenced by continuity in material culture. However, the character of the city appears to have changed, the citadel growing crowded and foreign imports declining.

The city was destroyed around 1180 BC, roughly contemporary with the Late Bronze Age collapse

The Late Bronze Age collapse was a time of widespread societal collapse during the 12th century BC, between c. 1200 and 1150. The collapse affected a large area of the Eastern Mediterranean (North Africa and Southeast Europe) and the Near East ...

but subsequent to the destruction of the Mycenaean palaces. The destruction layer shows evidence of enemy attack, including scorch marks.

Troy VIIb

After the destruction of Troy VIIa around 1180 BC, the city was rebuilt as Troy VIIb. Older structures were again reused, including Troy VI's citadel walls. Its first phase, Troy VIIb1, is largely a continuation of Troy VIIa. Residents continued using wheel-made Grey Ware pottery alongside a new handmade style sometimes known as "barbarian ware". Imported Mycenaean-style pottery attests to some continuing foreign trade.

One of the most striking finds from Troy VIIb1 is a

After the destruction of Troy VIIa around 1180 BC, the city was rebuilt as Troy VIIb. Older structures were again reused, including Troy VI's citadel walls. Its first phase, Troy VIIb1, is largely a continuation of Troy VIIa. Residents continued using wheel-made Grey Ware pottery alongside a new handmade style sometimes known as "barbarian ware". Imported Mycenaean-style pottery attests to some continuing foreign trade.

One of the most striking finds from Troy VIIb1 is a hieroglyphic Luwian

Hieroglyphic Luwian (''luwili'') is a variant of the Luwian language, recorded in official and royal seals and a small number of monumental inscriptions. It is written in a hieroglyphic script known as Anatolian hieroglyphs.

A decipherment was pr ...

seal giving the names of a woman and a man who worked as a scribe. The seal is important since it is the only example of preclassical writing found at the site, and provides potential evidence that Troy VIIb1 had a Luwian

The Luwians were a group of Anatolian peoples who lived in central, western, and southern Anatolia, in present-day Turkey, during the Bronze Age and the Iron Age. They spoke the Luwian language, an Indo-European language of the Anatolian sub-fa ...

-speaking population. However, the find is puzzling since palace bureaucracies had largely disappeared by this era. Proposed explanations include the possibility that it belonged to an itinerant freelance scribe and alternatively that it dates from an earlier era than its find context would suggest.

Troy VIIb2 is marked by cultural changes including walls made of upright stones and a handmade knobbed pottery style known as ''Buckelkeramik''. These practices, which existed alongside older local traditions, have been argued to reflect immigrant populations arriving from southwest Europe. Pottery finds from this layer also include imported Protogeometric

The Protogeometric style (or "Proto-Geometric") is a style of Ancient Greek pottery led by Athens produced between roughly 1030 and 900 BCE, in the first period of the Greek Dark Ages. After the collapse of the Mycenaean-Minoan Palace culture ...

pottery, showing that Troy was occupied continuously well into the Iron Age, contrary to later legend.

Troy VIIb was destroyed by fire around 950 BC. However, some houses in the citadel were left intact and the site continued to be occupied, if only sparsely.

Troy VIII–IX

Troy VIII was founded during theGreek Dark Ages

The term Greek Dark Ages refers to the period of Greek history from the end of the Mycenaean palatial civilization, around 1100 BC, to the beginning of the Archaic age, around 750 BC. Archaeological evidence shows a widespread collaps ...

and lasted until the Roman era

In modern historiography, ancient Rome refers to Roman civilisation from the founding of the city of Rome in the 8th century BC to the collapse of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century AD. It encompasses the Roman Kingdom (753–509 BC ...

. Though the site had never been entirely abandoned, its redevelopment as a major city was spurred by Greek immigrants who began building around 700 BC. During the Archaic period, the city's defenses once again included the reused citadel wall of Troy VI. Later on, the walls became tourist attraction and sites of worship. Other remains of the Bronze Age city were destroyed by the Greeks' building projects, notably the peak of the citadel where the Troy VI palace is likely to have stood. By the classical era

Classical antiquity (also the classical era, classical period or classical age) is the period of cultural history between the 8th century BC and the 5th century AD centred on the Mediterranean Sea, comprising the interlocking civilizations of ...

, the city had numerous temples, a theater, among other public buildings, and was once again expanding to the south of the citadel. Troy VIII was destroyed in 85 BC, and subsequently rebuilt as Troy IX. A series of earthquakes devastated the city around 500 AD, though finds from the Late Byzantine era attest to continued habitation at a small scale.

Excavation history

The search for Troy

Pierre Belon

Pierre Belon (1517–1564) was a French traveller, naturalist, writer and diplomat. Like many others of the Renaissance period, he studied and wrote on a range of topics including ichthyology, ornithology, botany, comparative anatomy, architectur ...

and Pietro Della Valle

Pietro Della Valle ( la, Petrus a Valle; 2 April 1586 – 21 April 1652), also written Pietro della Valle, was an Italian composer, musicologist, and author who travelled throughout Asia during the Renaissance period. His travels took him to the ...

, had identified Troy with Alexandria Troas

Alexandria Troas ("Alexandria of the Troad"; el, Αλεξάνδρεια Τρωάς; tr, Eski Stambul) is the site of an ancient Greek city situated on the Aegean Sea near the northern tip of Turkey's western coast, the area known historically a ...

, a ruined Hellenistic town approximately south of Hisarlik. In the late 18th century, Jean Baptiste LeChevalier

Jean Baptiste LeChevalier (July 1, 1752, in Trelly, Manche department to July 2, 1836, in Paris, Saint-Étienne-du-Mont) was a French scholar, astronomer and archaeologist.

LeChevalier studied in Paris and taught from 1772 to 1778 at several coll ...

identified a location near the village of Pınarbaşı, Ezine, a mound approximately south of the currently accepted location. Published in his ''Voyage de la Troade'', it was the most commonly proposed location for almost a century.

In 1822, the Scottish journalist Charles Maclaren

Charles Maclaren (7 October 1782 – 10 September 1866) was a Scottish journalist and geologist. He co-founded ''The Scotsman'' newspaper, was its editor for 27 years, and edited the 6th Edition of the ''Encyclopædia Britannica'' and the firs ...

was the first to identify with confidence the position of the city as it is now known. In the second half of the 19th century archaeological excavation of the site believed to have been Homeric Troy began. The Hisarlik mound was about 200 meters long and somewhat less than 150 meters wide. It rose 31.2 meters above the plain and 38.5 meters above sea level.

Frank Calvert

The first excavation at Hisarlik, a small sounding, was conducted in 1865 byFrank Calvert

Frank Calvert (1828–1908) was an English expatriate who was a consular official in the eastern Mediterranean region and an amateur archaeologist. He began exploratory excavations on the mound at Hisarlik (the site of the ancient city of Troy) ...

, a Turkish Levantine

Levantines in Turkey or Turkish Levantines, refers to the descendants of Europeans who settled in the coastal cities of the Ottoman Empire to trade, especially after the Tanzimat Era. Their estimated population today is around 1,000.

man of English descent who owned a farm nearby. Calvert made extensive surveys of the site, identifying it with classical-era Troy. This identification helped him convince Heinrich Schliemann that Troy was there, and to partner with him in its further excavation.

Heinrich Schliemann

In 1868, German businessman

In 1868, German businessman Heinrich Schliemann

Johann Ludwig Heinrich Julius Schliemann (; 6 January 1822 – 26 December 1890) was a German businessman and pioneer in the field of archaeology. He was an advocate of the historicity of places mentioned in the works of Homer and an archaeologi ...

visited Calvert, and secured permission to excavate Hisarlik

Hisarlik (Turkish: ''Hisarlık'', "Place of Fortresses"), often spelled Hissarlik, is the Turkish name for an ancient city located in what is known historically as Anatolia.A compound of the noun, hisar, "fortification," and the suffix -lik. The s ...

. Schliemann believed that the literary events of the works of Homer could be verified archaeologically, and he decided to use his wealth to locate it.

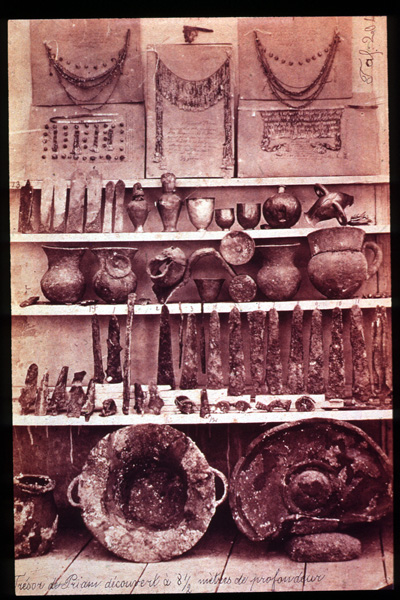

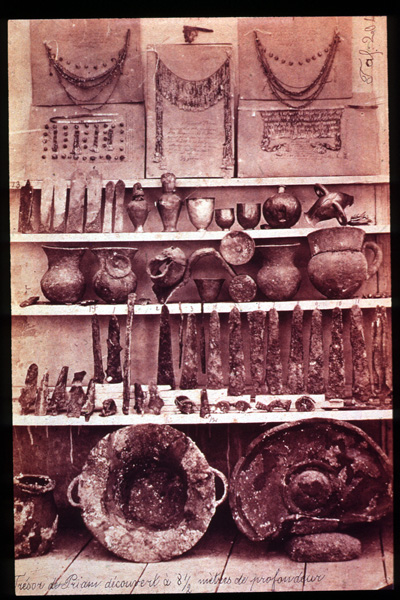

As with Calvert and others, in April 1870 Schliemann began by excavating a trench across the mound of Hisarlik to the depth of the settlements, today called "Schliemann's Trench.". Schuchhardt, "Schliemans Excavations: An archaeological and historical study", MacMillan and Co, London, 1891 In 1871–1873 and 1878–1879, 1882 and 1890 (the later two joined by Wilhelm Dörpfeld), he discovered the ruins of a series of ancient cities dating from the

Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a historic period, lasting approximately from 3300 BC to 1200 BC, characterized by the use of bronze, the presence of writing in some areas, and other early features of urban civilization. The Bronze Age is the second pri ...

to the Roman period. Schliemann was planning for another excavation season in 1891 when he died in December 1890. He proposed that the second layer, Troy II, corresponded to the city of legend, though later research has shown that it predated the Mycenaean era by several hundred years. Some of the most notable artifacts found by Schliemann are known as Priam's Treasure

Priam's Treasure is a cache of gold and other artifacts discovered by classical archaeologists Frank Calvert and Heinrich Schliemann at Hissarlik, on the northwestern coast of modern Turkey. The majority of the artifacts are currently in the Pushk ...

, after the legendary Trojan king. Many of these ended up in the Istanbul Archaeology Museum

The Istanbul Archaeology Museums ( tr, ) are a group of three archaeological museums located in the Eminönü quarter of Istanbul, Turkey, near Gülhane Park and Topkapı Palace.

The Istanbul Archaeology Museums consists of three museums:

#Arch ...

. Almost all the precious metal objects that went to Berlin were confiscated by the Soviet Union in 1945 and are now in Pushkin Museum

The Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts (russian: Музей изобразительных искусств имени А. С. Пушкина, abbreviated as ) is the largest museum of European art in Moscow, located in Volkhonka street, just oppo ...

in Moscow

Moscow ( , US chiefly ; rus, links=no, Москва, r=Moskva, p=mɐskˈva, a=Москва.ogg) is the capital and largest city of Russia. The city stands on the Moskva River in Central Russia, with a population estimated at 13.0 million ...

. Even in his own time Schliemann's legacy was controversial because of his excavation methods which included removing features he considered insignificant without first studying and documenting them.

Modern excavations

Wilhelm Dörpfeld

Wilhelm Dörpfeld

Wilhelm Dörpfeld (26 December 1853 – 25 April 1940) was a German architect and archaeologist, a pioneer of stratigraphic excavation and precise graphical documentation of archaeological projects. He is famous for his work on Bronze Age site ...

began excavating the site alongside Schliemann and later inherited management of the site and published his own independent work. His chief contributions were to the study of Troy VI and VII, which Schliemann had overlooked due to his fixation on Troy II. Dörpfeld's interest in these layers was triggered by the need to close a hole in the initial excavators' chronology known as "Calvert's Thousand Year Gap". During his excavation, Dörpfeld came across a section of the Troy VI wall which was weaker than the rest. Since the mythic city had likewise had a weak section of its walls, Dörpfeld became convinced that this layer corresponded to Homeric Troy. Schliemann himself privately agreed that Troy VI was more likely to be the Homeric city, but he never published anything stating so.

University of Cincinnati

=Carl Blegen

=Carl Blegen

Carl William Blegen (January 27, 1887 – August 24, 1971) was an American archaeologist who worked at the site of Pylos in Greece and Troy in modern-day Turkey. He directed the University of Cincinnati excavations of the mound of Hisarlik, the ...

, professor at the University of Cincinnati

The University of Cincinnati (UC or Cincinnati) is a public research university in Cincinnati, Ohio. Founded in 1819 as Cincinnati College, it is the oldest institution of higher education in Cincinnati and has an annual enrollment of over 44,00 ...

, managed the site 1932–38. Wilhelm Dörpfeld collaborated with Blegen. These archaeologists, though following Schliemann's lead, added a professional approach not available to Schliemann. He showed that there were at least nine cities. In his research, Blegen came to a conclusion that Troy's nine levels could be further divided into forty-six sublevels, which he published in his main report.

Korfmann

In 1988, excavations were resumed by a team from the University of Tübingen and theUniversity of Cincinnati

The University of Cincinnati (UC or Cincinnati) is a public research university in Cincinnati, Ohio. Founded in 1819 as Cincinnati College, it is the oldest institution of higher education in Cincinnati and has an annual enrollment of over 44,00 ...

under the direction of Professor Manfred Korfmann

Manfred Osman Korfmann (April 26, 1942 – August 11, 2005) was a German archeologist. He excavated Hisarlik, the present site of Troy situated in modern-day Turkey.

He continued his research in Turkey, excavating from 1982 to 1987 at Besik ...

, with Professor Brian Rose overseeing Post-Bronze Age (Greek, Roman, Byzantine) excavation along the coast of the Aegean Sea at the Bay of Troy. Possible evidence of a battle was found in the form of bronze arrowheads and fire-damaged human remains buried in layers dated to the early 12th century BC. The question of Troy's status in the Bronze-Age world has been the subject of a sometimes acerbic debate between Korfmann and the Tübingen historian Frank Kolb

Frank Kolb (born 27 February 1945 in Rheinbach, Rhine Province) is a German professor of ancient history at the University of Tübingen in Germany. He has been involved in a controversy over findings concerning the late Bronze Age in Troy, and accu ...

in 2001–2002.

Korfmann proposed that the location of the city indicated a commercially oriented economy that would have been at the center of a vibrant trade between the Black Sea, Aegean, Anatolian and Eastern Mediterranean regions. Kolb disputed this thesis, calling it "unfounded" in a 2004 paper. He argued that archaeological evidence shows that economic trade during the Late Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a historic period, lasting approximately from 3300 BC to 1200 BC, characterized by the use of bronze, the presence of writing in some areas, and other early features of urban civilization. The Bronze Age is the second pri ...

was quite limited in the Aegean region compared with later periods in antiquity. On the other hand, the Eastern Mediterranean economy was more active during this time, allowing for commercial cities to develop only in the Levant

The Levant () is an approximate historical geographical term referring to a large area in the Eastern Mediterranean region of Western Asia. In its narrowest sense, which is in use today in archaeology and other cultural contexts, it is eq ...

. Kolb also noted the lack of evidence for trade with the Hittite Empire

The Hittites () were an Anatolian people who played an important role in establishing first a kingdom in Kussara (before 1750 BC), then the Kanesh or Nesha kingdom (c. 1750–1650 BC), and next an empire centered on Hattusa in north-centra ...

.

One of the major discoveries of these excavations was the Troy VI–VII lower city. This discovery led to a major reinterpretation of the site, which had previously been regarded as a small aristocratic residence rather than a major settlement.

Recent developments

In summer 2006, the excavations continued under the direction of Korfmann's colleague Ernst Pernicka, with a new digging permit. In 2013, an international team made up of cross-disciplinary experts led by William Aylward, an archaeologist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, was to carry out new excavations. This activity was to be conducted under the auspices ofÇanakkale Onsekiz Mart University

Çanakkale Onsekiz Mart University (informally ''ÇOMÜ'') is a Turkish public research university located in Çanakkale (Dardannelles) province (near Gallipoli) and its surrounding towns. It is a member of the Balkan Universities Network, the ...

and was to use the new technique of "molecular archaeology". A few days before the Wisconsin team was to leave, Turkey cancelled about 100 excavation permits, including Wisconsin's.

In March 2014, it was announced that a new excavation would take place to be sponsored by a private company and carried out by Çanakkale Onsekiz Mart University. This will be the first Turkish team to excavate and is planned as a 12 month excavation led by associate professor Rüstem Aslan. The University's rector stated that "Pieces unearthed in Troy will contribute to Çanakkale's culture and tourism. Maybe it will become one of Turkey's most important frequented historical places."

Historical Troy

Troy I–V predate writing and thus study of them falls into the category ofprehistoric archaeology

Prehistoric archaeology is a subfield of archaeology, which deals specifically with artefacts, civilisations and other materials from societies that existed before any form of writing system or historical record. Often the field focuses on ages s ...

. However, Troy emerges into protohistory

Protohistory is a period between prehistory and history during which a culture or civilization has not yet developed writing, but other cultures have already noted the existence of those pre-literate groups in their own writings. For example, in ...

in the Late Bronze Age, as records mentioning the city begin to appear at other sites. Troy VIII and Troy IX are dated to the historical period and thus are part of history proper.

Troy VI–VII in Hittite records

Troy VI–VII is thought to correspond to the placenames ''Wilusa

Wilusa ( hit, ) or Wilusiya was a Late Bronze Age city in western Anatolia known from references in fragmentary Hittites, Hittite records. The city is notable for its identification with the archaeological site of Troy, and thus its potential con ...

'' and ''Taruisa'' known from Hittite records. These correspondences were first proposed in 1924 by E. Forrer, who also suggested that the name ''Ahhiyawa

The Achaeans (; grc, Ἀχαιοί ''Akhaioí,'' "the Achaeans" or "of Achaea") is one of the names in Homer which is used to refer to the Greeks collectively.

The term "Achaean" is believed to be related to the Hittite term Ahhiyawa and th ...

'' corresponds to the Homeric term for the Greeks, '' Achaeans''. These proposals were primarily motivated by linguistic similarities, since "''Taruisa''" is a plausible match for the Greek name "''Troia''" and "''Wilusa''" likewise for the Greek "''Wilios''" (later "''Ilios''"). Subsequent research on Hittite geography has made these identifications more secure, though not all scholars regard them as firmly established.

Wilusa first appears in Hittite records around 1400 BC, when it was one of the twenty-two states of the Assuwa Confederation which unsuccessfully attempted to oppose the Hittite Empire

The Hittites () were an Anatolian people who played an important role in establishing first a kingdom in Kussara (before 1750 BC), then the Kanesh or Nesha kingdom (c. 1750–1650 BC), and next an empire centered on Hattusa in north-centra ...

. Circumstantial evidence raises the possibility that the rebellion was supported by the Ahhiyawa. By the late 1300s BC, Wilusa had become politically aligned with the Hittites. Texts from this period mention two kings named Kukkunni

Kukkunni was a king of Wilusa mentioned in the Alaksandu Treaty as an ally of the Hittite king Suppiluliuma I. He ruled over the city during a period of peace and prosperity visible in the archaeological layer of Troy VI. The later Greek name K ...

and Alaksandu

Alaksandu, ( Hittite: 𒀀𒆷𒀝𒊭𒀭𒁺𒍑 ''Alâkšândûš'') alternatively called Alakasandu or Alaksandus was a king of Wilusa who sealed a treaty with Hittite king Muwatalli II ca. 1280 BC. This treaty implies that Alaksandu had prev ...

who maintained peaceful relations with the Hittites even as other states in the area did not. Wilusan soldiers may have served in the Hittite army during the Battle of Kadesh

The Battle of Kadesh or Battle of Qadesh took place between the forces of the New Kingdom of Egypt under Ramesses II and the Hittite Empire under Muwatalli II at the city of Kadesh on the Orontes River, just upstream of Lake Homs near the mod ...

. A bit later, Wilusa seems to have experienced the political turmoil suffered by many of its neighbors. References in the Manapa-Tarhunta letter The Manapa-Tarhunta letter ( CTH 191; KUB 19.5 + KBo 19.79) is a tablet in Luwian/Hittite language from the thirteenth century BC, which has come down to us in a fairly good state of conservation. It was discovered in the 1980s.

It was written by ...

and Tawagalawa letter

The Tawagalawa letter ( CTH 181) is a fragmentary Hittite text from the mid 13th century BC. It is notable for providing a window into relations between Hittites and Greeks during the Late Bronze Age and for its mention of a prior disagreement con ...

suggest that a Wilusan king either rebelled or was deposed. This turmoil may have been related to the exploits of Piyamaradu Piyamaradu (also spelled ''Piyama-Radu'', ''Piyama Radu'', ''Piyamaradus'', ''Piyamaraduš'') was a warlord mentioned in Hittite documents from the middle and late 13th century BC. As an ally of the Ahhiyawa, he led or supported insurrections again ...

, a Western Anatolian warlord who toppled other pro-Hittite rulers while acting on behalf the Ahhiyawa. However, Piyamaradu is never explicitly identified as the culprit and certain features of the text suggest that he was not. The final reference to Wilusa in the historical record appears in the Milawata letter The Milawata letter (CTH 182) is an item of diplomatic correspondence from a Hittite king at Hattusa to a client king in western Anatolia around 1240 BC. It constitutes an important piece of evidence in the debate concerning the historicity of Home ...

, in which the Hittite king Tudhaliya IV Tudhaliya is the name of several Hittite kings:

*Tudhaliya (also Tudhaliya I) is a hypothetic pre-Empire king of the Hittites. He would have reigned in the late 17th century BC ( short chronology). Forlanini (1993) conjectures that this king corres ...

expresses his intention to reinstall a deposed Wilusan king named Walmu

Walmu was a king of Wilusa in the late 13th century BC. He is known from the Milawata letter, which reports that he had been deposed and discusses the Hittites' intent to reinstall him. The letter does not specify how Walmu was deposed or who was ...

.

In popular writing, these anecdotes have been interpreted as evidence for a historical kernel in myths of the Trojan War. However, scholars have not found historical evidence for any particular event from the legends, and the Hittite documents do not suggest that Wilusa-Troy was ever attacked by Greeks-Ahhiyawa themselves. Noted Hittiteologist T. Bryce cautions that our current understanding of Wilusa's history does not provide evidence for there having been an actual Trojan War since "the less material one has, the more easily it can be manipulated to fit whatever conclusion one wishes to come up with".

Classical and Hellenistic Troy (Troy VIII)

In 480 BC, the Persian king Xerxes sacrificed 1,000 cattle at the sanctuary of Athena Ilias while marching through the Hellespontine region towards Greece. Following the Persian defeat in 480–479, Ilion and its territory became part of the continental possessions ofMytilene

Mytilene (; el, Μυτιλήνη, Mytilíni ; tr, Midilli) is the capital of the Greek island of Lesbos, and its port. It is also the capital and administrative center of the North Aegean Region, and hosts the headquarters of the University of ...

and remained under Mytilenaean control until the unsuccessful Mytilenean revolt

The Mytilenean revolt was an incident in the Peloponnesian War in which the city of Mytilene attempted to unify the island of Lesbos under its control and revolt from the Athenian Empire. In 428 BC, the Mytilenean government planned a rebellion ...

in 428–427. Athens liberated the so-called Actaean cities including Ilion and enrolled these communities in the Delian League

The Delian League, founded in 478 BC, was an association of Greek city-states, numbering between 150 and 330, under the leadership of Athens, whose purpose was to continue fighting the Persian Empire after the Greek victory in the Battle of Pl ...

. Athenian influence in the Hellespont waned following the oligarchic coup of 411, and in that year the Spartan general Mindaros emulated Xerxes by likewise sacrificing to Athena Ilias. From c. 410–399, Ilion was within the sphere of influence of the local dynasts at Lampsacus

Lampsacus (; grc, Λάμψακος, translit=Lampsakos) was an ancient Greek city strategically located on the eastern side of the Hellespont in the northern Troad. An inhabitant of Lampsacus was called a Lampsacene. The name has been transmitt ...

(Zenis, his wife Mania, and the usurper Meidias) who administered the region on behalf of the Persian satrap Pharnabazus.

In 399, the Spartan general Dercylidas Dercylidas (Greek: Δερκυλίδας) was a Spartan commander during the 5th and 4th century BC. For his cunning and inventiveness, he was nicknamed Sisyphus. In 411 BC he was appointed harmost at Abydos. In 399 BC, he was advised by Antisthen ...

expelled the Greek garrison at Ilion who were controlling the city on behalf of the Lampsacene dynasts during a campaign which rolled back Persian influence throughout the Troad. Ilion remained outside the control of the Persian satrapal administration at Dascylium

Dascylium, Dascyleium, or Daskyleion ( grc, Δασκύλιον, Δασκυλεῖον), also known as Dascylus, was a town in Anatolia some inland from the coast of the Propontis, at modern Ergili, Turkey. Its site was rediscovered in 1952 and ...

until the Peace of Antalcidas

The King's Peace (387 BC) was a peace treaty guaranteed by the Persian King Artaxerxes II that ended the Corinthian War in ancient Greece. The treaty is also known as the Peace of Antalcidas, after Antalcidas, the Spartan diplomat who traveled t ...

in 387–386. In this period of renewed Persian control c. 387–367, a statue of Ariobarzanes, the satrap of Hellespontine Phrygia

Hellespontine Phrygia ( grc, Ἑλλησποντιακὴ Φρυγία, Hellēspontiakē Phrygia) or Lesser Phrygia ( grc, μικρᾶ Φρυγία, mikra Phrygia) was a Persian satrapy (province) in northwestern Anatolia, directly southeast of t ...

, was erected in front of the temple of Athena Ilias. In 360–359 the city was briefly controlled by Charidemus Charidemus (or Kharidemos, grc-gre, Χαρίδημος), of Oreus in Euboea, was an ancient Greek mercenary leader of the 4th century BC. He had a complicated relationship with Athens, sometimes aiding the city in its efforts to secure its interes ...

of Oreus

Oreus or Oreos ( grc, Ὠρεός, Ōreos), prior to the 5th century BC called Histiaea or Histiaia (Ἱστίαια), also Hestiaea or Hestiaia (Ἑστίαια), was a town near the north coast of ancient Euboea, situated upon the river Ca ...

, a Euboean mercenary leader who occasionally worked for the Athenians. In 359, he was expelled by the Athenian Menelaos son of Arrabaios, whom the Ilians honoured with a grant of proxeny

Proxeny or ( grc-gre, προξενία) in ancient Greece was an arrangement whereby a citizen (chosen by the city) hosted foreign ambassadors at his own expense, in return for honorary titles from the state. The citizen was called (; plural: o ...

—this is recorded in the earliest civic decree to survive from Ilion. In May 334 Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, wikt:Ἀλέξανδρος, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek kingdom of Maced ...

crossed the Hellespont and came to the city, where he visited the temple of Athena Ilias, made sacrifices at the tombs of the Homeric heroes, and made the city free and exempt from taxes. According to the so-called 'Last Plans' of Alexander which became known after his death in June 323, he had planned to rebuild the temple of Athena Ilias on a scale that would have surpassed every other temple in the known world.

Antigonus Monophthalmus

Antigonus I Monophthalmus ( grc-gre, Ἀντίγονος Μονόφθαλμος , 'the One-Eyed'; 382 – 301 BC), son of Philip from Elimeia, was a Macedonian Greek nobleman, general, satrap, and king. During the first half of his life he serv ...

took control of the Troad in 311 and created the new city of Antigoneia Troas which was a synoikism

Synoecism or synecism ( ; grc, συνοικισμóς, ''sunoikismos'', ), also spelled synoikism ( ), was originally the amalgamation of villages in Ancient Greece into ''poleis'', or city-states. Etymologically the word means "dwelling toge ...

of the cities of Skepsis

Scepsis or Skepsis ( grc, Σκῆψις or Σκέψις) was an ancient settlement in the Troad, Asia Minor that is at the present site of the village of Kurşunlutepe, near the town of Bayramiç in Turkey. The settlement is notable for being t ...

, Kebren, Neandreia

Neandreia ( grc, Νεάνδρεια), Neandrium or Neandrion (Νεάνδριον), also known as Neandrus or Neandros (Νέανδρος), was a Greek city in the south-west of the Troad region of Anatolia. Its site has been located on Çığrı Da ...

, Hamaxitos, Larisa

Larissa (; el, Λάρισα, , ) is the capital and largest city of the Thessaly region in Greece. It is the fifth-most populous city in Greece with a population of 144,651 according to the 2011 census. It is also capital of the Larissa regiona ...

, and Kolonai

Kolonai ( grc, αἱ Κολωναί, hai Kolōnai; la, Colonae) was an ancient Greek city in the south-west of the Troad region of Anatolia. It has been located on a hill by the coast known as Beşiktepe ('cradle hill'), about equidistant betwe ...

. In c. 311–306 the ''koinon

''Koinon'' ( el, Κοινόν, pl. Κοινά, ''Koina''), meaning "common", in the sense of "public", had many interpretations, some societal, some governmental. The word was the neuter form of the adjective, roughly equivalent in the government ...

''of Athena Ilias was founded from the remaining cities in the Troad and along the Asian coast of the Dardanelles

The Dardanelles (; tr, Çanakkale Boğazı, lit=Strait of Çanakkale, el, Δαρδανέλλια, translit=Dardanéllia), also known as the Strait of Gallipoli from the Gallipoli peninsula or from Classical Antiquity as the Hellespont (; ...

and soon after succeeded in securing a guarantee from Antigonus that he would respect their autonomy and freedom (he had not respected the autonomy of the cities which were synoikized to create Antigoneia). The ''koinon ''continued to function until at least the 1st century AD and primarily consisted of cities from the Troad, although for a time in the second half of the 3rd century it also included Myrlea

Apamea Myrlea (; grc, Απάμεια Μύρλεια) was an ancient city and bishopric (Apamea in Bithynia) on the Sea of Marmara, in Bithynia, Anatolia; its ruins are a few kilometers south of Mudanya, Bursa Province in the Marmara Region of ...

and Chalcedon

Chalcedon ( or ; , sometimes transliterated as ''Chalkedon'') was an ancient maritime town of Bithynia, in Asia Minor. It was located almost directly opposite Byzantium, south of Scutari (modern Üsküdar) and it is now a district of the cit ...

from the eastern Propontis

The Sea of Marmara,; grc, Προποντίς, Προποντίδα, Propontís, Propontída also known as the Marmara Sea, is an inland sea located entirely within the borders of Turkey. It connects the Black Sea to the Aegean Sea via the ...

. The governing body of the ''koinon ''was the ''synedrion'' on which each city was represented by two delegates. The day-to-day running of the ''synedrion'', especially in relation to its finances, was left to a college of five ''agonothetai'', on which no city ever had more than one representative. This system of equal (rather than proportional) representation ensured that no one city could politically dominate the ''koinon''. The primary purpose of the ''koinon ''was to organize the annual Panathenaia festival which was held at the sanctuary of Athena Ilias. The festival brought huge numbers of pilgrims to Ilion for the duration of the festival as well as creating an enormous market (the ''panegyris'') which attracted traders from across the region. In addition, the ''koinon ''financed new building projects at Ilion, for example a new theatre c. 306 and the expansion of the sanctuary and temple of Athena Ilias in the 3rd century, in order to make the city a suitable venue for such a large festival.

In the period 302–281, Ilion and the Troad were part of the kingdom of Lysimachus

Lysimachus (; Greek: Λυσίμαχος, ''Lysimachos''; c. 360 BC – 281 BC) was a Thessalian officer and successor of Alexander the Great, who in 306 BC, became King of Thrace, Asia Minor and Macedon.

Early life and career

Lysimachus was b ...

, who during this time helped Ilion synoikize several nearby communities, thus expanding the city's population and territory.

Lysimachus was defeated at the Battle of Corupedium

The Battle of Corupedium, also called Koroupedion, Corupedion or Curupedion ( grc, Κύρου πεδίον or Κόρου πεδίον, "the plain of Kyros or Koros") was the last battle between the Diadochi, the rival successors to Alexander the Gr ...

in February 281 by Seleucus I Nikator

Seleucus I Nicator (; ; grc-gre, Σέλευκος Νικάτωρ , ) was a Macedonian Greek general who was an officer and successor ( ''diadochus'') of Alexander the Great. Seleucus was the founder of the eponymous Seleucid Empire. In the po ...

, thus handing the Seleucid kingdom control of Asia Minor

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

, and in August or September 281 when Seleucus passed through the Troad on his way to Lysimachia

''Lysimachia'' () is a genus consisting of 193 accepted species of flowering plants traditionally classified in the family Primulaceae. Based on a molecular phylogenetic study it was transferred to the family Myrsinaceae, before this family wa ...

in the nearby Thracian Chersonese Ilion passed a decree in honour of him, indicating the city's new loyalties. In September Seleucus was assassinated at Lysimachia by Ptolemy Keraunos

Ptolemy Ceraunus ( grc-gre, Πτολεμαῖος Κεραυνός ; c. 319 BC – January/February 279 BC) was a member of the Ptolemaic dynasty and briefly king of Macedon. As the son of Ptolemy I Soter, he was originally heir to the thron ...

, making his successor, Antiochus I Soter

Antiochus I Soter ( grc-gre, Ἀντίοχος Σωτήρ, ''Antíochos Sōtér''; "Antiochus the Saviour"; c. 324/32 June 261 BC) was a Greek king of the Seleucid Empire. Antiochus succeeded his father Seleucus I Nicator in 281 BC and reigned du ...

, the new king. In 280 or soon after Ilion passed a long decree lavishly honouring Antiochus in order to cement their relationship with him.

During this period Ilion still lacked proper city walls except for the crumbling Troy VI fortifications around the citadel, and in 278 during the Gallic invasion the city was easily sacked. Ilion enjoyed a close relationship with Antiochus for the rest of his reign: for example, in 274 Antiochus granted land to his friend Aristodikides of Assos which for tax purposes was to be attached to the territory of Ilion, and c. 275–269 Ilion passed a decree in honour of Metrodoros of Amphipolis who had successfully treated the king for a wound he received in battle.

Roman Troy (Troy IX)

A new city called Ilium (from Greek Ilion) was founded on the site in the reign of the Roman emperorAugustus

Caesar Augustus (born Gaius Octavius; 23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14), also known as Octavian, was the first Roman emperor; he reigned from 27 BC until his death in AD 14. He is known for being the founder of the Roman Pri ...

. It flourished until the establishment of Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis (" ...

, which became a bishopric in the Roman province

The Roman provinces (Latin: ''provincia'', pl. ''provinciae'') were the administrative regions of Ancient Rome outside Roman Italy that were controlled by the Romans under the Roman Republic and later the Roman Empire. Each province was rule ...

Hellespontus (civil Diocese of Asia

The Diocese of Asia ( la, Dioecesis Asiana, el, Διοίκησις Ἀσίας/Άσιανῆς) was a diocese of the later Roman Empire, incorporating the provinces of western Asia Minor and the islands of the eastern Aegean Sea. The diocese was ...

), but declined gradually in the Byzantine era

The Byzantine calendar, also called the Roman calendar, the Creation Era of Constantinople or the Era of the World ( grc, Ἔτη Γενέσεως Κόσμου κατὰ Ῥωμαίους, also or , abbreviated as ε.Κ.; literal translation of ...

.

The city was destroyed by Sulla

Lucius Cornelius Sulla Felix (; 138–78 BC), commonly known as Sulla, was a Roman general and statesman. He won the first large-scale civil war in Roman history and became the first man of the Republic to seize power through force.

Sulla had ...

's rival, the Roman general Fimbria, in 85 BC following an eleven-day siege. Later that year when Sulla had defeated Fimbria, he bestowed benefactions on Ilion for its loyalty which helped rebuilding the city. Ilion reciprocated this act of generosity by instituting a new civic calendar which took 85 BC as its first year. However, the city remained in financial distress for several decades despite its favoured status with Rome. In the 80s BC, Roman ''publicani'' illegally levied taxes on the sacred estates of Athena Ilias, and the city was required to call on L. Julius Caesar for restitution; while in 80 BC, the city suffered an attack by pirates. In 77 BC the costs of running the annual festival of the ''koinon'' of Athena Ilias became too pressing for both Ilion and the other members of the ''koinon'' and L. Julius Caesar was once again required to arbitrate, this time reforming the festival so that it would be less of a financial burden. In 74 BC the Ilians once again demonstrated their loyalty to Rome by siding with the Roman general Lucullus