Tristan and Iseult on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Tristan and Iseult, also known as Tristan and Isolde and other names, is a medieval

Tristan and Iseult, also known as Tristan and Isolde and other names, is a medieval

The story and character of

The story and character of  After defeating the Irish knight Morholt, the young prince Tristan travels to

After defeating the Irish knight Morholt, the young prince Tristan travels to  The lovers flee into the forest of Morrois and take shelter there until Mark later discovers them. They make peace with Mark after Tristan agrees to return Iseult to Mark and leave the country. Tristan then travels to

The lovers flee into the forest of Morrois and take shelter there until Mark later discovers them. They make peace with Mark after Tristan agrees to return Iseult to Mark and leave the country. Tristan then travels to

French sources, such as the ones chosen in the English translation by

French sources, such as the ones chosen in the English translation by

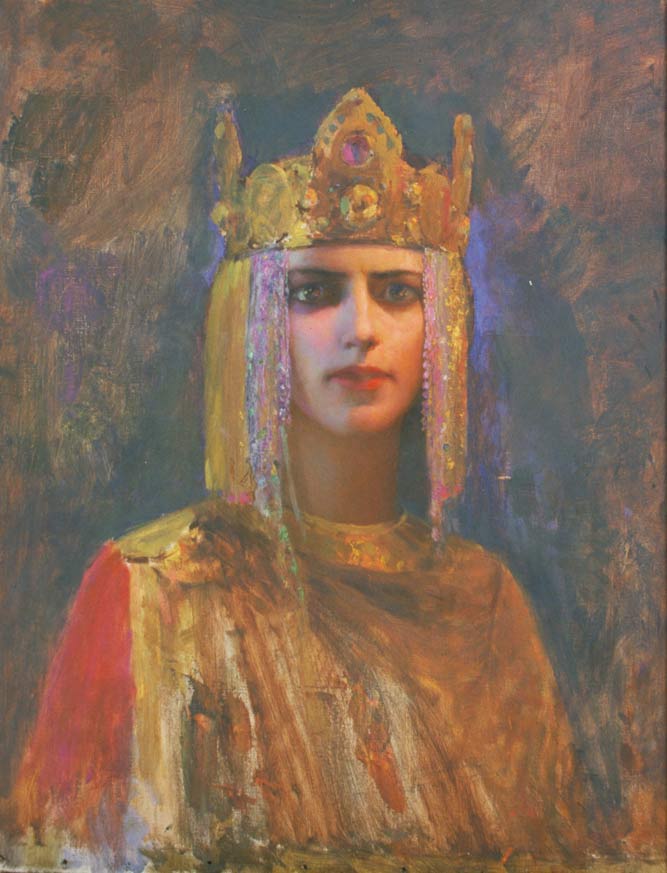

Various art forms from the medieval era represented Tristan's story, from ivory mirror cases to the 13th-century Sicilian Tristan Quilt. In addition, many literary versions are illuminated with miniatures. The legend also became a popular subject for Romanticist painters of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Various art forms from the medieval era represented Tristan's story, from ivory mirror cases to the 13th-century Sicilian Tristan Quilt. In addition, many literary versions are illuminated with miniatures. The legend also became a popular subject for Romanticist painters of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

In 1832,

In 1832,

Overview of the story

* *

Béroul's ''Le Roman de Tristan''

*

Thomas d'Angleterre's ''Tristan''

*

{{Authority control Arthurian characters Arthurian literature Breton mythology and folklore Celtic mythology Cornwall in fiction Literary duos Love stories Welsh mythology

Tristan and Iseult, also known as Tristan and Isolde and other names, is a medieval

Tristan and Iseult, also known as Tristan and Isolde and other names, is a medieval chivalric romance

As a literary genre, the chivalric romance is a type of prose and verse narrative that was popular in the noble courts of High Medieval and Early Modern Europe. They were fantastic stories about marvel-filled adventures, often of a chivalric ...

told in numerous variations since the 12th century. Based on a Celtic

Celtic, Celtics or Keltic may refer to:

Language and ethnicity

*pertaining to Celts, a collection of Indo-European peoples in Europe and Anatolia

**Celts (modern)

*Celtic languages

**Proto-Celtic language

*Celtic music

*Celtic nations

Sports Foo ...

legend and possibly other sources, the tale is a tragedy about the illicit love between the Cornish knight Tristan

Tristan ( Latin/Brythonic: ''Drustanus''; cy, Trystan), also known as Tristram or Tristain and similar names, is the hero of the legend of Tristan and Iseult. In the legend, he is tasked with escorting the Irish princess Iseult to wed ...

and the Irish princess Iseult

Iseult (), alternatively Isolde () and other spellings, is the name of several characters in the legend of Tristan and Iseult. The most prominent is Iseult of Ireland, the wife of Mark of Cornwall and the lover of Tristan. Her mother, the quee ...

. It depicts Tristan's mission to escort Iseult from Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel, the Irish Sea, and St George's Channel. Ireland is the s ...

to marry his uncle, King Mark

Mark of Cornwall ( la, Marcus, kw, Margh, cy, March, br, Marc'h) was a sixth-century King of Kernow (Cornwall), possibly identical with King Conomor. He is best known for his appearance in Arthurian legend as the uncle of Tristan and the husb ...

of Cornwall

Cornwall (; kw, Kernow ) is a Historic counties of England, historic county and Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South West England. It is recognised as one of the Celtic nations, and is the homeland of the Cornish people ...

. On the journey, Tristan and Iseult ingest a love potion

A love potion ( la, poculum amatorium) is a magical liquid which supposedly causes the drinker to develop feelings of love towards the person who served it.

The love potion motif occurs in literature, mainly in fairy tales, and in paintings, ...

, instigating a forbidden love affair between them.

The story has had a lasting impact on Western culture

Leonardo da Vinci's ''Vitruvian Man''. Based on the correlations of ideal Body proportions">human proportions with geometry described by the ancient Roman architect Vitruvius in Book III of his treatise ''De architectura''.

image:Plato Pio-Cle ...

. Its different versions exist in many European texts in various languages from the Middle Ages. The earliest instances take two primary forms: the courtly and common branches. The former begins with the 12th-century poems of Thomas of Britain and Béroul, while the latter reflects a now-lost original version. A subsequent version emerged in the 13th century in the wake of the greatly expanded Prose ''Tristan'', merging Tristan's romance with the legend of King Arthur

King Arthur ( cy, Brenin Arthur, kw, Arthur Gernow, br, Roue Arzhur) is a legendary king of Britain, and a central figure in the medieval literary tradition known as the Matter of Britain.

In the earliest traditions, Arthur appears as ...

. Finally, after the revived interest in the medieval era under the influence of Romantic nationalism

Romantic nationalism (also national romanticism, organic nationalism, identity nationalism) is the form of nationalism in which the state claims its political legitimacy as an organic consequence of the unity of those it governs. This includes ...

, the story has continued to be popular in the modern era, notably Wagner's operatic adaptation.

Narratives

The story and character of

The story and character of Tristan

Tristan ( Latin/Brythonic: ''Drustanus''; cy, Trystan), also known as Tristram or Tristain and similar names, is the hero of the legend of Tristan and Iseult. In the legend, he is tasked with escorting the Irish princess Iseult to wed ...

vary between versions. His name also varies, although Tristan is the most common modern spelling. The earliest tradition comes from the French romances of Thomas of Britain and Béroul, two poets from the second half of the 12th century. Later traditions come from the vast Prose ''Tristan'' (), markedly different from the tales of Thomas and Béroul.

After defeating the Irish knight Morholt, the young prince Tristan travels to

After defeating the Irish knight Morholt, the young prince Tristan travels to Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel, the Irish Sea, and St George's Channel. Ireland is the s ...

to bring back the fair Iseult

Iseult (), alternatively Isolde () and other spellings, is the name of several characters in the legend of Tristan and Iseult. The most prominent is Iseult of Ireland, the wife of Mark of Cornwall and the lover of Tristan. Her mother, the quee ...

(often known as Isolde, Isolt, or Yseult) for his uncle King Mark of Cornwall to marry. Along the way, Tristan and Iseult ingest a love potion which causes them to fall madly in love. The potion's effects last a lifetime in the legend's courtly branch. However, in the common branch version, the potion's results end after three years.

In some versions, Tristan and Iseult ingest the potion accidentally. In others, the potion's maker gives it to Iseult to share with Mark, but she gives it to Tristan instead. Although Iseult marries Mark, the spell forces her and Tristan to seek each other as lovers. The King's advisors repeatedly try to charge the pair with adultery

Adultery (from Latin ''adulterium'') is extramarital sex that is considered objectionable on social, religious, moral, or legal grounds. Although the sexual activities that constitute adultery vary, as well as the social, religious, and legal ...

, but the lovers use trickery to preserve their façade of innocence. In Béroul's version, the love potion eventually wears off, but the two lovers continue their adulterous relationship.

Like the Arthur–Lancelot

Lancelot du Lac (French for Lancelot of the Lake), also written as Launcelot and other variants (such as early German ''Lanzelet'', early French ''Lanselos'', early Welsh ''Lanslod Lak'', Italian ''Lancillotto'', Spanish ''Lanzarote del Lago' ...

–Guinevere

Guinevere ( ; cy, Gwenhwyfar ; br, Gwenivar, kw, Gwynnever), also often written in Modern English as Guenevere or Guenever, was, according to Arthurian legend, an early-medieval queen of Great Britain and the wife of King Arthur. First me ...

love triangle

A love triangle or eternal triangle is a scenario or circumstance, usually depicted as a rivalry, in which two people are pursuing or involved in a romantic relationship with one person, or in which one person in a romantic relationship with ...

in the medieval courtly love

Courtly love ( oc, fin'amor ; french: amour courtois ) was a medieval European literary conception of love that emphasized nobility and chivalry. Medieval literature is filled with examples of knights setting out on adventures and performing var ...

motif, Tristan, King Mark, and Iseult all love one another. Tristan honors and respects his uncle King Mark as his mentor and adopted father. Iseult is grateful for Mark's kindness to her. Mark loves Tristan as his son and Iseult as a wife. However, every night each has horrible dreams about the future. Simultaneous to the love triangle is the endangerment of a fragile kingdom and the end of the war between Ireland and Cornwall

Cornwall (; kw, Kernow ) is a Historic counties of England, historic county and Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South West England. It is recognised as one of the Celtic nations, and is the homeland of the Cornish people ...

( Dumnonia).

King Mark eventually learns of the affair and seeks to entrap his nephew and wife. Mark acquires what seems to be proof of their guilt and resolves to punish Tristan by hanging

Hanging is the suspension of a person by a noose or ligature around the neck.Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd ed. Hanging as method of execution is unknown, as method of suicide from 1325. The ''Oxford English Dictionary'' states that hanging ...

and Iseult by burning at the stake

Death by burning (also known as immolation) is an execution and murder method involving combustion or exposure to extreme heat. It has a long history as a form of public capital punishment, and many societies have employed it as a punishment f ...

. However, Mark changes his mind about Iseult and lodges her in a leper colony

A leper colony, also known by many other names, is an isolated community for the quarantining and treatment of lepers, people suffering from leprosy. ''M. leprae'', the bacterium responsible for leprosy, is believed to have spread from East Afr ...

. Tristan escapes on his way to the gallows, making a miraculous leap from a chapel to rescue Iseult.

The lovers flee into the forest of Morrois and take shelter there until Mark later discovers them. They make peace with Mark after Tristan agrees to return Iseult to Mark and leave the country. Tristan then travels to

The lovers flee into the forest of Morrois and take shelter there until Mark later discovers them. They make peace with Mark after Tristan agrees to return Iseult to Mark and leave the country. Tristan then travels to Brittany

Brittany (; french: link=no, Bretagne ; br, Breizh, or ; Gallo: ''Bertaèyn'' ) is a peninsula, historical country and cultural area in the west of modern France, covering the western part of what was known as Armorica during the period ...

, where he marries Iseult of the White Hands, daughter of Hoel of Brittany, for her name and beauty. In some versions, including Béroul and the '' Folie Tristan d'Oxford'', Tristan returns in disguise to woo Iseult of Ireland, but the dog, Husdent, betrays his identity.

Association with Arthur and death

The earliest surviving Tristan poems include references toKing Arthur

King Arthur ( cy, Brenin Arthur, kw, Arthur Gernow, br, Roue Arzhur) is a legendary king of Britain, and a central figure in the medieval literary tradition known as the Matter of Britain.

In the earliest traditions, Arthur appears as ...

and his court. Mentions of Tristan and Iseult are also found in some early Arthurian texts. Writers expanded the connection between the story and the Arthurian legend over time. Shortly after the completion of the '' Vulgate Cycle'' (the ''Lancelot-Grail'' cycle) in the first half of the 13th century, two authors created the Prose ''Tristan'', which establishes Tristan as one of the most outstanding Knight of the Round Table. Here, he is also portrayed as a former enemy turned friend of Lancelot and a participant in the Quest for the Holy Grail

The Holy Grail (french: Saint Graal, br, Graal Santel, cy, Greal Sanctaidd, kw, Gral) is a treasure that serves as an important motif in Arthurian literature. Various traditions describe the Holy Grail as a cup, dish, or stone with miracul ...

. The Prose ''Tristan'' evolved into the familiar medieval tale of Tristan and Iseult that became the '' Post-Vulgate Cycle''. Two centuries later, it became the primary source for the seminal Arthurian compilation ''Le Morte d'Arthur

' (originally written as '; inaccurate Middle French for "The Death of Arthur") is a 15th-century Middle English prose reworking by Sir Thomas Malory of tales about the legendary King Arthur, Guinevere, Lancelot, Merlin and the Knights of the ...

''.

In the popular extended version of the Prose ''Tristan'', and the works derived from it, Tristan is attacked by King Mark while he plays the harp for Iseult. Mark strikes Tristan with a poisoned or cursed lance, mortally wounding him, and the lovers die together. The poetic treatments of the Tristan legend, however, offer a very different account of the hero's death, and the short version of the Prose ''Tristan'' and some later works also use the traditional account of Tristan's death as found in the poetic versions.

In Thomas' poem, Tristan is wounded by a poisoned lance while attempting to rescue a young woman from six knights. Tristan sends his friend Kahedin to find Iseult of Ireland, the only person who can heal him. Tristan tells Kahedin to sail back with white sails if he is bringing Iseult and black sails if he is not (perhaps an echo of the Greek myth of Theseus

Theseus (, ; grc-gre, Θησεύς ) was the mythical king and founder-hero of Athens. The myths surrounding Theseus his journeys, exploits, and friends have provided material for fiction throughout the ages.

Theseus is sometimes describ ...

). Iseult agrees to return to Tristan with Kahedin, but Tristan's jealous wife, Iseult of the White Hands, lies to Tristan about the color of the sails. Tristan dies of grief, thinking Iseult has betrayed him, and Iseult dies over his corpse.

Post-death

French sources, such as the ones chosen in the English translation by

French sources, such as the ones chosen in the English translation by Hilaire Belloc

Joseph Hilaire Pierre René Belloc (, ; 27 July 187016 July 1953) was a Franco-English writer and historian of the early twentieth century. Belloc was also an orator, poet, sailor, satirist, writer of letters, soldier, and political activist. ...

in 1903, state that a bramble briar grows out of Tristan's grave, growing so thickly that it forms a bower and roots itself into Iseult's grave. King Mark tries to have the branches cut three separate times, and each time the branches grow back and intertwine. Later versions embellish the story with the briar above Tristan's grave intertwining and a rose tree from Iseult's grave. Other variants replace the intertwining trees with hazel and honeysuckle.

Later versions state that the lovers had several children, including a son and a daughter named after themselves. The children have adventures of their own. In the 14th-century French romance ''Ysaÿe le Triste'' (''Ysaÿe the Sad''), the eponymous hero is the son of Tristan and Iseult. He becomes involved with the fairy king Oberon and marries a girl named Martha, who bears him a son named Mark. Spanish ''Tristan el Joven'' also included Tristan's son, referred to as Tristan of Leonis.

Origins and analogs

There are several theories about the tale's origins, although historians disagree over which is the most accurate.British

The mid-6th century "Drustanus Stone" in southeast Cornwall close toCastle Dore

Castle Dore is an Iron Age hill fort ( ringfort) near Fowey in Cornwall, United Kingdom located at . It was probably occupied from the 5th or 4th centuries BC until the 1st century BC. It consists of two ditches surrounding a circul ...

has an inscription referring to ''Drustan'', son of Cunomorus (Mark). However, not all historians agree that the Drustan referred to is the archetype of Tristan. The inscription is heavily eroded, but the earliest records of the stone, dating to the 16th century, all agree on some variation of CIRVIVS / CIRUSIUS as the name inscribed. It was first read as a variation of DRUSTANUS in the late 19th century. The optimistic reading corresponds to the 19th-century revival of medieval romance. A 2014 study using 3D scanning supported the initial "CI" reading rather than the backward-facing "D."

There are references to March ap Meichion (Mark) and Trystan in the ''Welsh Triads'', some gnomic poetry, the ''Mabinogion

The ''Mabinogion'' () are the earliest Welsh prose stories, and belong to the Matter of Britain. The stories were compiled in Middle Welsh in the 12th–13th centuries from earlier oral traditions. There are two main source manuscripts, creat ...

'' stories, and the 11th-century hagiography of Illtud. A character called Drystan appears as one of King Arthur's advisers at the end of ''The Dream of Rhonabwy

''The Dream of Rhonabwy'' ( cy, Breuddwyd Rhonabwy) is a Middle Welsh prose tale. Set during the reign of Madog ap Maredudd, prince of Powys (died 1160), its composition is typically dated to somewhere between the late 12th through the late 14th ...

'', a 13th-century tale in the Middle Welsh prose collection known as the ''Mabinogion''. Iseult is also a member of Arthur's court in '' Culhwch and Olwen,'' an earlier ''Mabinogion'' tale.

Irish

Scholars have given much attention to possible Irish antecedents to the Tristan legend. An ill-fated love triangle is featured in several Irish works, most notably in '' Tóraigheacht Dhiarmada agus Ghráinne'' (''The Pursuit of Diarmuid and Gráinne''). In this literary work, the aging Fionn mac Cumhaill is to marry the young princess, Gráinne. At the betrothal ceremony, she falls in love with Diarmuid Ua Duibhne, one of Fionn's most trusted warriors. Gráinne gives asleeping potion

A potion () is a liquid "that contains medicine, poison, or something that is supposed to have magic powers.” It derives from the Latin word ''potus'' which referred to a drink or drinking. The term philtre is also used, often specifically ...

to all present but Diarmuid Ua Duibhne, and she convinces him to elope with her. Fianna pursues the fugitive lovers across Ireland.

Another Irish analog is ''Scéla Cano meic Gartnáin'', preserved in the 14th-century '' Yellow Book of Lecan''. In this tale, Cano is an exiled Scottish king who accepts the hospitality of King Marcan of Ui Maile. His young wife, Credd, drugs all present and convinces Cano to be her lover. They try to keep a tryst while at Marcan's court, but they are frustrated by courtiers. In the end, Credd kills herself, and Cano dies of grief.

The Ulster Cycle includes the text ''Clann Uisnigh'' or ''Deirdre of the Sorrows'' in which Naoise mac Usnech falls for Deirdre. However, King Conchobar mac Nessa imprisons her due to a prophecy that Ulster

Ulster (; ga, Ulaidh or ''Cúige Uladh'' ; sco, label= Ulster Scots, Ulstèr or ''Ulster'') is one of the four traditional Irish provinces. It is made up of nine counties: six of these constitute Northern Ireland (a part of the United Kin ...

will plunge into civil war due to men fighting for her beauty. Conchobar agrees to marry Deirdre to avert war and avenges Clann Uisnigh. The death of Naoise and his kin leads many Ulstermen to defect to Connacht

Connacht ( ; ga, Connachta or ), is one of the provinces of Ireland, in the west of Ireland. Until the ninth century it consisted of several independent major Gaelic kingdoms ( Uí Fiachrach, Uí Briúin, Uí Maine, Conmhaícne, and ...

, including Conchobar's stepfather and trusted ally, Fergus mac Róich. This eventually results in the Irish epic tale '' Táin Bó Cúailnge''.

Persian

Some scholars suggest that the 11th-century Persian story '' Vis and Rāmin'' is the model for the Tristan legend because the similarities are too significant to be coincidental.Stewart Gregory (translator), Thomas of Britain, ''Roman de Tristan'', New York: Garland Publishers, 1991. Fakhr al-Dīn Gurgānī, and Dick Davis. 2008. Vis & Ramin. Washington, DC: Mage publishers. The evidence for the Persian origin of Tristan and Iseult is very circumstantial. Some suggest the Persian story traveled to the West with story-telling exchanges in a Syrian court during crusades. Others believe the story came West with minstrels who had free access to both Crusader and Saracen camps in theHoly Land

The Holy Land; Arabic: or is an area roughly located between the Mediterranean Sea and the Eastern Bank of the Jordan River, traditionally synonymous both with the biblical Land of Israel and with the region of Palestine. The term "Holy ...

.

Roman

Some scholars believeOvid

Pūblius Ovidius Nāsō (; 20 March 43 BC – 17/18 AD), known in English as Ovid ( ), was a Augustan literature (ancient Rome), Roman poet who lived during the reign of Augustus. He was a contemporary of the older Virgil and Horace, with whom ...

's '' Pyramus and Thisbe'' and the story of Ariadne at Naxos may have contributed to the development of the Tristan legend. The sequence in which Tristan and Iseult die and become interwoven trees also parallels Ovid's love story of Baucis and Philemon

In Ovid's moralizing fables collected as ''Metamorphoses'' is his telling of the story of Baucis and Philemon, which stands on the periphery of Greek mythology and Roman mythology. Baucis and Philemon were an old married couple in the region ...

, where two lovers transform after death into two trees sprouting from the same trunk. However, this also occurs in the saga of Deirdre of the Sorrows

''Deirdre of the Sorrows'' is a three-act play written by Irish playwright John Millington Synge in 1909. The play, based on Irish mythology, in particular the myths concerning Deirdre, Naoise, and Conchobar, was unfinished at the author's death ...

, making the link more tenuous. Moreover, this theory ignores the lost oral tradition

Oral tradition, or oral lore, is a form of human communication wherein knowledge, art, ideas and Culture, cultural material is received, preserved, and transmitted orally from one generation to another.Jan Vansina, Vansina, Jan: ''Oral Traditio ...

s of pre-literate societies, relying only on written records that were damaged during the development of modern nation-states such as England and France, especially during the dissolution of the monasteries.

Branches

Common branch

The earliest representation of the common branch is Béroul's ''Le Roman de Tristan'' (''The Romance of Tristan''). The first part dates between 1150 and 1170, and the second one dates between 1181 and 1190. The common branch is so named because it represents an earlier non-chivalric

Chivalry, or the chivalric code, is an informal and varying code of conduct developed in Europe between 1170 and 1220. It was associated with the medieval Christian institution of knighthood; knights' and gentlemen's behaviours were governed ...

, non-courtly tradition of story-telling, making it more reflective of the Dark Ages than the refined High Middle Ages

The High Middle Ages, or High Medieval Period, was the periodization, period of European history that lasted from AD 1000 to 1300. The High Middle Ages were preceded by the Early Middle Ages and were followed by the Late Middle Ages, which ended ...

. In this respect, the works in this branch are similar to Layamon's ''Brut'' and the '' Perlesvaus''.

Beroul's version is the oldest known version of the Tristan romances, but knowledge of his work is limited. A few substantial fragments of his original version were discovered in the 19th century, with the rest reconstructed from later versions."Early French Tristan Poems", from Norris J. Lacy (editor), ''Arthurian Archives'', Cambridge, England; Rochester, NY: D.S. Brewer, 1998. It is commonly considered the closest presentation of all the raw events in the romance, with no explanation or modifications. As a result, Beroul's version is an archetype for later "common branch" editions. A more substantial illustration of the common branch is the German version by Eilhart von Oberge. Eilhart was popular but paled in comparison with the later Gottfried.

One aspect of the common branch that differentiates from the courtly branch is the depiction of the lovers' time in exile from Mark's court. While the courtly branch describes Tristan and Iseult as sheltering in a "Cave of Lovers" and living in happy seclusion, the common branches emphasize the extreme suffering that Tristan and Iseult endure. In the common branch, exile is a proper punishment that highlights the couple's departure from courtly norms and emphasizes the impossibility of their romance.

French medievalist Joseph Bédier

Joseph Bédier (28 January 1864 – 29 August 1938) was a French writer and scholar and historian of medieval France.

Biography

Bédier was born in Paris, France, to Adolphe Bédier, a lawyer of Breton origin, and spent his childhood in Réunio ...

thought all the Tristan legends could be traced to a single original: a Cornish or Breton poem. He dubbed this hypothetical original the "Ur-Tristan." Bédier wrote ''Romance of Tristan and Iseult'' to reconstruct what this source might have been like, incorporating material from other versions to make a cohesive whole. An English translation of Bédier's ''Roman de Tristan et Iseut'' (1900) by Edward J. Gallagher was published in 2013 by Hackett Publishing Company. A translation by Hilaire Belloc

Joseph Hilaire Pierre René Belloc (, ; 27 July 187016 July 1953) was a Franco-English writer and historian of the early twentieth century. Belloc was also an orator, poet, sailor, satirist, writer of letters, soldier, and political activist. ...

, first published in 1913, was published as a Caedmon Audio

Caedmon Audio and HarperCollins Audio are record label imprints of HarperCollins Publishers that specialize in audiobooks and other literary content. Formerly Caedmon Records, its marketing tag-line was Caedmon: a Third Dimension for the Printe ...

recording read by Claire Bloom in 1958 and republished in 2005.

Courtly branch

The earliest representation of what scholars name the "courtly" branch of the Tristan legend is in the work of Thomas of Britain, dating from 1173. Unfortunately, only ten fragments of his ''Tristan'' poem survived, compiled from six manuscripts. Of these six manuscripts, the ones in Turin and Strasbourg are now lost, leaving two in Oxford, one in Cambridge, and one in Carlisle. In his text, Thomas names another trouvère who also sang of Tristan, though no manuscripts of this earlier version have been discovered. There is also a passage describing Iseult writing a short lai out of grief. This information sheds light on the development of an unrelated legend concerning the death of a prominenttroubadour

A troubadour (, ; oc, trobador ) was a composer and performer of Old Occitan lyric poetry during the High Middle Ages (1100–1350). Since the word ''troubadour'' is etymologically masculine, a female troubadour is usually called a '' trobair ...

and the composition of lais by noblewomen of the 12th century.

The essential text for knowledge of the courtly branch of the Tristan legend is the abridged translation of Thomas made by Brother Robert at the request of King Haakon Haakonson of Norway in 1227. King Haakon had wanted to promote Angevin- Norman culture at his court, so he commissioned the translation of several French Arthurian works. The Nordic version presents a complete, direct narrative of the events in Thomas' ''Tristan'' with the omission of his numerous interpretive diversions. It is the only complete representative of the courtly branch in its formative period.

Chronologically preceding the work of Brother Robert is the ''Tristan and Isolt'' of Gottfried von Strassburg, written circa 1211–1215. The poem was Gottfried's only known work and was left incomplete due to his death, with the retelling reaching halfway through the main plot. Authors such as Heinrich von Freiberg and Ulrich von Türheim completed the poem at a later time, but with the common branch of the legend as the source.Norris J. Lacy ''et al.'' "Gottfried von Strassburg" from ''The New Arthurian Encyclopedia'', New York: Garland, 1991.

Other medieval versions

French

A contemporary of Béroul and Thomas of Britain, Marie de France presented a Tristan episode in her lais, "Chevrefoil

"Chevrefoil" is a Breton lai by the medieval poet Marie de France. The eleventh poem in the collection called '' The Lais of Marie de France'', its subject is an episode from the romance of Tristan and Iseult. The title means "honeysuckle," a symb ...

". The title refers to the symbiosis of the honeysuckle and hazelnut tree, which die when separated, similar to Tristan and Iseult. It concerns another of Tristan's clandestine returns to Cornwall, with the banished hero signaling his presence to Iseult with an inscribed hazelnut tree branch placed on a road she was to travel. This episode is similar to a version of the courtly branch when Tristan places wood shavings in a stream as a signal for Iseult to meet in the garden of Mark's palace.

There are also two 12th-century ''Folies Tristan'', Old French

Old French (, , ; Modern French: ) was the language spoken in most of the northern half of France from approximately the 8th to the 14th centuries. Rather than a unified language, Old French was a linkage of Romance dialects, mutually intel ...

poems known as the Berne (''Folie Tristan de Berne'') and the Oxford ('' Folie Tristan d'Oxford'') versions, which tell of Tristan's return to Marc's court under the guise of a madman. Besides their importance as episodic additions to the Tristan story and masterpieces of narrative structure, these relatively short poems significantly restored Béroul's and Thomas' incomplete texts.

Chrétien de Troyes

Chrétien de Troyes (Modern ; fro, Crestien de Troies ; 1160–1191) was a French poet and trouvère known for his writing on Arthurian subjects, and for first writing of Lancelot, Percival and the Holy Grail. Chrétien's works, including ...

claimed to have written a Tristan story, though it has never been found. Chrétien mentioned this in the introduction to his '' Cligès'', a romance that is anti-''Tristan'' with a happy ending. Some scholars speculate his ''Tristan'' was ill-received, prompting Chrétien to write ''Cligès—''a story with no Celtic antecedent—to make amends.

After Béroul and Thomas, the most noteworthy development in French Tristania is a complex grouping of texts known as the Prose ''Tristan''. Extremely popular in the 13th and 14th centuries, these lengthy narratives vary in detail. Modern editions run twelve volumes for the extended version that includes Tristan's participation in the Quest for the Holy Grail. The shorter version without the grail quest consists of five books.Before any editions of the Prose ''Tristan'' were attempted, scholars were dependent on an extended summary and analysis of all the manuscripts by Eilert Löseth in 1890 (republished in 1974). The more extended modern editions consist of two: Renée L. Curtis, ed. ''Le Roman de Tristan en prose'', vols. 1–3 (Cambridge: D.S. Brewer, 1963–1985) and Philippe Ménard, exec. ed. ''Le Roman de Tristan en Prose'', vols. 1–9 (Geneva: Droz, 1987–1997). Curtis' edition of a simple manuscript (Carpentras 404) covers Tristan's ancestry and the traditional legend up to Tristan's madness. However, the massive number of manuscripts dissuaded other scholars from attempting what Curtis had done until Ménard hit upon the idea of using multiple teams of scholars to tackle the infamous Vienna 2542 manuscript. His edition follows Curtis' and ends with Tristan's death and the first signs of Arthur's fall. Richard Trachsler is currently preparing an edition of the "continuation" of the Prose ''Tristan''. The shorter version, which contains no Grail Quest, is published by Joël Blanchard in five volumes. The Prose ''Tristan'' significantly influenced later medieval literature and inspired parts of the '' Post-Vulgate Cycle'' and the '' Roman de Palamedes''.

English

The earliest complete source of Tristan's story in English was ''Sir Tristrem

''Sir Tristrem'' is a 13th-century Middle English romance of 3,344 lines, preserved in the Auchinleck manuscript in the National Library of Scotland. Based on the ''Tristan'' of Thomas of Britain Thomas of Britain (also known as Thomas of England) ...

'', a romantic poem in the courtly style with 3,344 lines. It is part of the Auchinleck manuscript at the National Library of Scotland

The National Library of Scotland (NLS) ( gd, Leabharlann Nàiseanta na h-Alba, sco, Naitional Leebrar o Scotland) is the legal deposit library of Scotland and is one of the country's National Collections. As one of the largest libraries in t ...

. As with many medieval English adaptations of French Arthuriana, the poem's artistic achievement is average. However, some critics have tried to rehabilitate it, claiming it is a parody. Its first editor, Walter Scott

Sir Walter Scott, 1st Baronet (15 August 1771 – 21 September 1832), was a Scottish novelist, poet, playwright and historian. Many of his works remain classics of European and Scottish literature, notably the novels '' Ivanhoe'', '' Rob Roy ...

, provided a sixty-line ending to the story that was included in every subsequent edition.

Thomas Malory's ''The Book of Sir Tristram de Lyones'' is the only other medieval handling of the Tristan legend in English. Malory provided a shortened translation of the French Prose ''Tristan'', including in his compilation ''Le Morte d'Arthur

' (originally written as '; inaccurate Middle French for "The Death of Arthur") is a 15th-century Middle English prose reworking by Sir Thomas Malory of tales about the legendary King Arthur, Guinevere, Lancelot, Merlin and the Knights of the ...

''. In Malory's version, Tristram is the son of the King of Lyonesse

Lyonesse is a kingdom which, according to legend, consisted of a long strand of land stretching from Land's End at the southwestern tip of Cornwall, England, to what is now the Isles of Scilly in the Celtic Sea portion of the Atlantic Ocean. ...

. Since the Winchester Manuscript surfaced in 1934, there has been much scholarly debate on whether the Tristan narrative, like all the episodes in ''Le Morte d'Arthur,'' was intended to be an independent piece or part of a more extensive work.

Welsh

A short Tristan narrative, perhaps related to the Béroul text, exists in six Welsh manuscripts dating from the late 16th to the mid-17th century.Italian and Spanish

In Italy, many ''cantari'' or oral poems performed in the public square about Tristan or referencing him. These poems include ''Cantari di Tristano'', ''Due Tristani'' ''Quando Tristano e Lancielotto combattiero al petrone di Merlino'', ''Ultime Imprese e Morte Tristano'', and ''Vendetta che fe Messer Lanzelloto de la Morte di Messer Tristano'', among others. There are also four versions of the Prose ''Tristan'' in medieval Italy, named after the place of composition or library where they are housed: ''Tristano Panciaticchiano'' (Panciatichi family library), ''Tristano Riccardiano'' (Biblioteca Riccardiana), and ''Tristano Veneto'' (Venetian). The exception to this is '' La Tavola Ritonda'', a 15th-century Italian rewrite of the Prose ''Tristan''. In the first third of the 14th century, Arcipreste de Hita wrote his version of the Tristan story, ''Carta Enviada por Hiseo la Brunda a Tristán''. ''Respuesta de Tristán'' is a unique 15th-century romance written as imaginary letters between the two lovers. ''Libro del muy esforzado caballero Don Tristán de Leonís y de sus grandes hechos en armas'', a Spanish reworking of the Prose ''Tristan'' that was first published in Valladolid in 1501.Nordic and Dutch

The popularity of Brother Robert's version spawned a parody, ''Saga Af Tristram ok Ísodd'' and the poem ''Tristrams kvæði''. Two poems with Arthurian content have been preserved in the collection ofOld Norse

Old Norse, Old Nordic, or Old Scandinavian, is a stage of development of North Germanic dialects before their final divergence into separate Nordic languages. Old Norse was spoken by inhabitants of Scandinavia and their overseas settlement ...

prose translations of Marie de France's lais ''Strengleikar

''Strengleikar'' (English: ''Stringed Instruments'') is a collection of twenty-one Old Norse prose tales based on the Old French '' Lais'' of Marie de France. It is one of the literary works commissioned by King Haakon IV of Norway (r. 1217-126 ...

'' (Stringed Instruments). One of these is "Chevrefoil", translated as "Geitarlauf". The Austrian National Library in Vienna is in possession of a 158-line fragment of a Dutch version of Thomas' ''Tristan''.

Slavic

A 13th-century verse romance based on the German Tristan poems by Gottfried, Heinrich, and Eilhart was written in Old Czech. It is the only known verse representative of the Tristan story in Slavic languages. TheOld Belarusian

Ruthenian (Belarusian: руская мова; Ukrainian: руська мова; Ruthenian: руска(ѧ) мова; also see other names) is an exonymic linguonym for a closely-related group of East Slavic linguistic varieties, particularly th ...

prose ''Povest o Tryshchane'' from the 1560s represents the furthest Eastern advance of the legend. Some scholars believe it to be the last medieval Tristan or Arthurian text period. Its lineage goes back to the ''Tristano Veneto''. At that time, the Republic of Venice

The Republic of Venice ( vec, Repùblega de Venèsia) or Venetian Republic ( vec, Repùblega Vèneta, links=no), traditionally known as La Serenissima ( en, Most Serene Republic of Venice, italics=yes; vec, Serenìsima Repùblega de Venèsia ...

controlled large parts of the Serbo-Croatian language area, encouraging a more active literary and cultural life than most of the Balkans. The manuscript of the ''Povest'' states it was translated from a lost Serbian intermediary. Scholars assume the legend traveled from Venice through its Balkan colonies, finally reaching the last outpost in this Slavic language.

Visual art

Various art forms from the medieval era represented Tristan's story, from ivory mirror cases to the 13th-century Sicilian Tristan Quilt. In addition, many literary versions are illuminated with miniatures. The legend also became a popular subject for Romanticist painters of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Various art forms from the medieval era represented Tristan's story, from ivory mirror cases to the 13th-century Sicilian Tristan Quilt. In addition, many literary versions are illuminated with miniatures. The legend also became a popular subject for Romanticist painters of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Modern adaptations

Literature

In English, the Tristan story generally suffered the same fate as theMatter of Britain

The Matter of Britain is the body of medieval literature and legendary material associated with Great Britain and Brittany and the legendary kings and heroes associated with it, particularly King Arthur. It was one of the three great Weste ...

. However, after being ignored for about three centuries, a renaissance of original Arthurian literature took place in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Revival material includes Alfred Tennyson's "The Last Tournament" which is part of one of his '' Idylls of the King'', Matthew Arnold's 1852 ''Tristram and Iseult

''Tristram and Iseult'', published in 1852 by Matthew Arnold, is a narrative poem containing strong romantic and tragic themes. This poem draws upon the Tristan and Iseult legends which were popular with contemporary readers.

Background

Arnol ...

,'' and Algernon Charles Swinburne

Algernon Charles Swinburne (5 April 1837 – 10 April 1909) was an English poet, playwright, novelist, and critic. He wrote several novels and collections of poetry such as '' Poems and Ballads'', and contributed to the famous Eleventh Edition ...

's 1882 epic poem '' Tristram of Lyonesse''. Other compilers wrote Tristan's texts as prose novels or short stories.

By the 19th century, the Tristan legend spread across the Nordic world, from Denmark to the Faroe Islands

The Faroe Islands ( ), or simply the Faroes ( fo, Føroyar ; da, Færøerne ), are a North Atlantic island group and an autonomous territory of the Kingdom of Denmark.

They are located north-northwest of Scotland, and about halfway bet ...

. However, these stories diverged from their medieval precursors. For instance, in one Danish ballad, Tristan and Iseult are brother and sister. In two popular Danish chapbook

A chapbook is a small publication of up to about 40 pages, sometimes bound with a saddle stitch.

In early modern Europe a chapbook was a type of printed street literature. Produced cheaply, chapbooks were commonly small, paper-covered bookle ...

s of the late 18th century, ''Tristans Saga ok Inionu'' and ''En Tragoedisk Historie om den ædle og Tappre Tistrand'', Iseult is a princess of India. The popularity of these chapbooks inspired Icelandic poets Sigurður Breiðfjörð and Níels Jónsson to write rímur

In Icelandic literature, a ''ríma'' (, literally "a rhyme", pl. ''rímur'', ) is an epic poem written in any of the so-called ''rímnahættir'' (, "rímur meters"). They are rhymed, they alliterate and consist of two to four lines per stanza. T ...

, long verse narratives inspired by the Tristan legend.

Cornish writer Arthur Quiller-Couch started writing ''Castle Dor'', a retelling of the Tristan and Iseult myth in modern circumstances. He designated an innkeeper as King Mark, his wife as Iseult, and a Breton onion-seller as Tristan. The plot was set in Troy, the fictional name of his hometown of Fowey

Fowey ( ; kw, Fowydh, meaning 'Beech Trees') is a port town and civil parish at the mouth of the River Fowey in south Cornwall, England, United Kingdom. The town has been in existence since well before the Norman invasion, with the local ch ...

. The book was left unfinished at Quiller-Couch's death in 1944 and was completed in 1962 by Daphne du Maurier.

Rosemary Sutcliff wrote two novels based on the story of Tristan and Iseult. The first, ''Tristan and Iseult'', is a 1971 retelling of the story for young adults, set in Cornwall in the southern peninsula of Britain. The story appears again as a chapter of Sutcliff's 1981 Arthurian novel, '' The Sword and the Circle''. Thomas Berger retold the story of Tristan and Isolde in his 1978 interpretation of the Arthurian legend, '' Arthur Rex: A Legendary Novel''. Dee Morrison Meaney told the tale from Iseult's perspective in the 1985 novel ''Iseult'', focusing on the magical side of the story and how the arrival of the Saxons ended the druidic tradition and magical creatures.

Diana L. Paxson

Diana Lucile Paxson (born February 20, 1943) is an American author, primarily in the fields of Paganism and Heathenism. Her published works include fantasy and historical fiction novels, as well as numerous short stories. More recently she has a ...

's 1988 novel ''The White Raven'' told the legend of Tristan and Iseult (named in the book as Drustan and Esseilte) from the perspective of Iseult's handmaiden Brangien (Branwen), who was mentioned in various of the medieval stories. Joseph Bédier

Joseph Bédier (28 January 1864 – 29 August 1938) was a French writer and scholar and historian of medieval France.

Biography

Bédier was born in Paris, France, to Adolphe Bédier, a lawyer of Breton origin, and spent his childhood in Réunio ...

's ''Romance of Tristan and Iseult'' is quoted as a source by John Updike in the afterword to his 1994 novel ''Brazil'' about the lovers Tristão and Isabel. Bernard Cornwell included a historical interpretation of the legend as a side story in '' Enemy of God: A Novel of Arthur'', a 1996 entry in ''The Warlord Chronicles

''The Warlord Chronicles'' or ''The Warlord Trilogy'' is a series of three novels about Arthurian Britain written by Bernard Cornwell. The story is written as a mixture of historical fiction and Arthurian legend. The books were originally publish ...

'' series. Rosalind Miles wrote a trilogy about Tristan and Isolde: ''The Queen of the Western Isle'' (2002), ''The Maid of the White Hands'' (2003), and ''The Lady of the Sea'' (2004). Nancy McKenzie

Nancy Affleck McKenzie (February 19, 1948) is an American author of historical fiction. Her primary focus is Arthurian legend.

Publishing career

McKenzie published ''The Child Queen'' in 1994, and its sequel, ''The High Queen'', a year later. ...

wrote ''Prince of Dreams: A Tale of Tristan and Essylte'' as part of her Arthurian series in 2003. In Bengali

Bengali or Bengalee, or Bengalese may refer to:

*something of, from, or related to Bengal, a large region in South Asia

* Bengalis, an ethnic and linguistic group of the region

* Bengali language, the language they speak

** Bengali alphabet, the w ...

literature, Sunil Gangopadhyay

Sunil Gangopadhyay or Sunil Ganguly (7 September 1934 – 23 October 2012) was an Indian poet, historian and novelist in the Bengali language based in the city of Kolkata. He is a former Sheriff of Calcutta. Gangopadhyay obtained his m ...

depicts the story in the novel ''Sonali Dukkho''. In Harry Turtledove's alternate history '' Ruled Britannia'', Christopher Marlowe

Christopher Marlowe, also known as Kit Marlowe (; baptised 26 February 156430 May 1593), was an English playwright, poet and translator of the Elizabethan era. Marlowe is among the most famous of the Elizabethan playwrights. Based upon t ...

writes a play called ''Yseult and Tristan'' to compete with his friend William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

's immensely popular ''Hamlet

''The Tragedy of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark'', often shortened to ''Hamlet'' (), is a tragedy written by William Shakespeare sometime between 1599 and 1601. It is Shakespeare's longest play, with 29,551 words. Set in Denmark, the play depicts ...

''.

Theater and opera

In 1832,

In 1832, Gaetano Donizetti

Domenico Gaetano Maria Donizetti (29 November 1797 – 8 April 1848) was an Italian composer, best known for his almost 70 operas. Along with Gioachino Rossini and Vincenzo Bellini, he was a leading composer of the '' bel canto'' opera style ...

referenced this story in his opera ''L'elisir d'amore

''L'elisir d'amore'' (''The Elixir of Love'', ) is a ' (opera buffa) in two acts by the Italian composer Gaetano Donizetti. Felice Romani wrote the Italian libretto, after Eugène Scribe's libretto for Daniel Auber's ' (1831). The opera pre ...

(The Elixir of Love'' or ''The Love Potion)'' in Milan. The character Adina sings the story to the ensemble, inspiring Nemorino to ask the charlatan Dulcamara for the magic elixir.

Premiering in 1865, Richard Wagner

Wilhelm Richard Wagner ( ; ; 22 May 181313 February 1883) was a German composer, theatre director, polemicist, and conductor who is chiefly known for his operas (or, as some of his mature works were later known, "music dramas"). Unlike most op ...

's influential opera '' Tristan und Isolde'' depicts Tristan as a doomed romantic figure, while Isolde fulfills Wagner's quintessential feminine role as the redeeming woman. Swiss composer Frank Martin wrote the chamber opera ''Le Vin Herbé'' between 1938 and 1940 after being influenced by Wagner.

Thomas Hardy published his one-act play ''The Famous Tragedy of the Queen of Cornwall at Tintagel in Lyonnesse'' in 1923. Rutland Boughton's 1924 opera ''The Queen of Cornwall'' was based on Thomas Hardy's play.

Music

Twentieth-century composers have often used the legend with Wagnerian overtones in their compositions. For instance, Hans Werner Henze's orchestral composition ''Tristan

Tristan ( Latin/Brythonic: ''Drustanus''; cy, Trystan), also known as Tristram or Tristain and similar names, is the hero of the legend of Tristan and Iseult. In the legend, he is tasked with escorting the Irish princess Iseult to wed ...

'' borrowed freely from the Wagnerian version and other retellings of the legend.

English composer Rutland Boughton composed the music drama ''The Queen of Cornwall'', inspired by Hardy's play. Its first performance was at the Glastonbury Festival

Glastonbury Festival (formally Glastonbury Festival of Contemporary Performing Arts and known colloquially as Glasto) is a five-day festival of contemporary performing arts that takes place in Pilton, Somerset, England. In addition to contemp ...

in 1924. Feeling that Hardy's play offered too much-unrelieved grimness, Broughton received permission to import a handful of lyrics from Hardy's early poetical works. In 2010, it was recorded on the Dutton Epoch label with Ronald Corp conducted the New London Orchestra and members of the London Chorus, including soloists Neal Davies (King Mark), Heather Shipp (Queen Iseult), Jacques Imbrailo (Sir Tristam), and Joan Rodgers

Joan Rodgers C.B.E. (born 1956, Cleator Moor, Cumbria, England) is an English operatic soprano. She was married to the conductor Paul Daniel, and married Alan Samson in 2013. She studied singing with Audrey Langford. She made her professional o ...

(Iseult of Brittany).

Olivier Messiaen

Olivier Eugène Prosper Charles Messiaen (, ; ; 10 December 1908 – 27 April 1992) was a French composer, organist, and ornithology, ornithologist who was one of the major composers of the 20th-century classical music, 20th century. His m ...

built his 1948 symphony '' Turangalîla-Symphonie'' around the story. German power metal band Blind Guardian have a song inspired by Tristan and Iseult's story, " The Maiden and the Minstrel Knight", in their 2002 album ''A Night at the Opera''. English singer and songwriter Patrick Wolf featured a song about the Tristan and Iseult legend, "Tristan", in his 2005 album '' Wind in the Wires''. American indie rock band Tarkio has a song entitled "Tristan and Iseult" in their album '' Sea Songs for Landlocked Sailers''.

Film and television

The story has also been adapted into film many times. The earliest is probably the 1909 French silent film ''Tristan et Yseult''. Another French film of the same name was released two years later and offered a unique addition to the story: Tristan's jealous slave Rosen tricks the lovers into drinking the love potion, then denounces them to Mark. Mark pities the two lovers, but they commit double suicide anyway. There is also a French silent film version from 1920 closely following the legend. One of the most celebrated and controversial Tristan films was 1943's ''L'Éternel Retour

''The Eternal Return'' (French: ''L'Éternel retour'') is a 1943 French romantic drama film directed by Jean Delannoy and starring Madeleine Sologne and Jean Marais. The screenplay was written by Jean Cocteau as a retelling of Tristan and Is ...

'' (''The Eternal Return''), directed by Jean Delannoy

Jean Delannoy (12 January 1908 – 18 June 2008) was a French actor, film editor, screenwriter and film director.

Biography

Although Delannoy was born in a Paris suburb, his family was from Haute-Normandie in the north of France. He was a P ...

with a screenplay by Jean Cocteau

Jean Maurice Eugène Clément Cocteau (, , ; 5 July 1889 – 11 October 1963) was a French poet, playwright, novelist, designer, filmmaker, visual artist and critic. He was one of the foremost creatives of the s ...

. It is a contemporary retelling of the story with a man named Patrice in the role of Tristan, who fetches a wife for his friend Marke. However, an evil dwarf tricks them into drinking a love potion, and the familiar plot ensues. The film was made in France during the Vichy regime

Vichy France (french: Régime de Vichy; 10 July 1940 – 9 August 1944), officially the French State ('), was the fascist French state headed by Marshal Philippe Pétain during World War II. Officially independent, but with half of its ter ...

under German domination. Elements of the movie reflect National Socialist

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in ...

ideology, with the beautiful blonde hero and heroine offset by the Untermensch

''Untermensch'' (, ; plural: ''Untermenschen'') is a Nazi term for non-Aryan "inferior people" who were often referred to as "the masses from the East", that is Jews, Roma, and Slavs (mainly ethnic Poles, Serbs, and later also Russians). The ...

dwarf. The dwarf has a more prominent role than in most interpretations of the legend; its conniving rains havoc on the lovers, much like the Jews of Nazi stereotypes.

The 1970 Spanish film ''Tristana'' is only tangentially related to the story. The role of Tristan is assumed by the female character Tristana, who cares for her aging uncle, Don Lope. However, she wishes to marry Horacio. The 1981 Irish film '' Lovespell'' features Nicholas Clay as Tristan and Kate Mulgrew as Iseult. Coincidentally, Clay went on to play Lancelot in John Boorman

Sir John Boorman (; born 18 January 1933) is a British film director, best known for feature films such as '' Point Blank'' (1967), ''Hell in the Pacific'' (1968), ''Deliverance'' (1972), '' Zardoz'' (1974), '' Exorcist II: The Heretic'' (1977 ...

's epic '' Excalibur''. The German film '' Fire and Sword'' (''Feuer und Schwert – Die Legende von Tristan und Isolde'') premiered at the Cannes Film Festival

The Cannes Festival (; french: link=no, Festival de Cannes), until 2003 called the International Film Festival (') and known in English as the Cannes Film Festival, is an annual film festival held in Cannes, France, which previews new films ...

in 1981 and was released in 1982. The film starred Christoph Waltz

Christoph Waltz (; born 4 October 1956) is an Austrian-German actor. Since 2009 he has been primarily active in the United States. His accolades include two Academy Awards, two Golden Globe Awards, two British Academy Film Awards and two Scree ...

as Tristan and was regarded as accurate to the story, though it removed the Iseult of Brittany's subplot.

French director François Truffaut

François Roland Truffaut ( , ; ; 6 February 1932 – 21 October 1984) was a French film director, screenwriter, producer, actor, and film critic. He is widely regarded as one of the founders of the French New Wave. After a career of more th ...

adapted the subject to modern times for his 1981 film '' La Femme d'à côté'' (''The Woman Next Door''), while 1988's ''In the Shadow of the Raven

''In the Shadow of the Raven'' ( Icelandic: ''Í skugga hrafnsins'' ()) is the title of a 1988 film by Hrafn Gunnlaugsson, set in Viking Age Iceland. The film was selected as the Icelandic entry for the Best Foreign Language Film at the 61st A ...

'' transported the characters to medieval Iceland. In the latter, Trausti and Isolde are warriors from rival tribes who come into conflict when Trausti kills the leader of Isolde's tribe. However, a local bishop makes peace between the two and arranges for their marriage. Bollywood director Subhash Ghai Subhash may refer to:

People

* Subhash Agarwal, Indian professional player and coach of English billiards and snooker

* Subhash Awchat (born 1960), Indian artist and author based in Mumbai

* Subhash Bapurao Wankhede (born 1963), Indian politician ...

transferred the story to modern India and the United States in his 1997 musical '' Pardes''.

The legend received a high-budget treatment with 2006's '' Tristan & Isolde'', produced by Tony Scott

Anthony David Leighton Scott (21 June 1944 – 19 August 2012) was an English film director and producer. He was known for directing highly successful action and thriller films such as '' Top Gun'' (1986), '' Beverly Hills Cop II'' (1987), ''D ...

and Ridley Scott

Sir Ridley Scott (born 30 November 1937) is a British film director and producer. Directing, among others, science fiction films, his work is known for its atmospheric and highly concentrated visual style. Scott has received many accolades th ...

, written by Dean Georgaris, directed by Kevin Reynolds, and starring James Franco and Sophia Myles

Sophia Jane Myles (; born 18 March 1980) is an English actress. She is best known in film for portraying Lady Penelope Creighton-Ward in ''Thunderbirds'' (2004), Isolde in '' Tristan & Isolde'' (2006), Darcy in '' Transformers: Age of Extinctio ...

. In this version, Tristan is a Cornish warrior raised from a young age by Lord Marke after being orphaned when his parents are killed. In a fight with the Irish, Tristan defeats Morholt, the Irish King's second, but is poisoned during the battle, which dulls his senses. Believing Tristan is dead, his companions send him off in a boat meant to cremate a dead body. Meanwhile, Isolde leaves her home over an unwilling betrothal to Morholt and finds Tristan on the Irish coast.

An animated TV series, ''Tristán & Isolda: La Leyenda Olvidada,'' aired in Spain and France in 1998. The 2002 French animated phil ''Tristan et Iseut'' is a redacted version of the traditional tale aimed at a family audience.

See also

*Antony and Cleopatra

''Antony and Cleopatra'' ( First Folio title: ''The Tragedie of Anthonie, and Cleopatra'') is a tragedy by William Shakespeare. The play was first performed, by the King's Men, at either the Blackfriars Theatre or the Globe Theatre in aroun ...

*Romeo and Juliet

''Romeo and Juliet'' is a tragedy written by William Shakespeare early in his career about the romance between two Italian youths from feuding families. It was among Shakespeare's most popular plays during his lifetime and, along with ''Ham ...

* Pyramus and Thisbe

* Canoel

*Medieval hunting

Throughout Western Europe in the Middle Ages, humans hunted wild animals. While game was at times an important source of food, it was rarely the principal source of nutrition. All classes engaged in hunting, but by the High Middle Ages, the nece ...

(terminology)

References

External links

Overview of the story

* *

Béroul's ''Le Roman de Tristan''

*

Thomas d'Angleterre's ''Tristan''

*

{{Authority control Arthurian characters Arthurian literature Breton mythology and folklore Celtic mythology Cornwall in fiction Literary duos Love stories Welsh mythology