Treaty Of 1818 on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Convention respecting fisheries, boundary and the restoration of slaves, also known as the London Convention, Anglo-American Convention of 1818, Convention of 1818, or simply the Treaty of 1818, is an international

The treaty was negotiated for the US by

The treaty was negotiated for the US by

treaty

A treaty is a formal, legally binding written agreement between actors in international law. It is usually made by and between sovereign states, but can include international organizations

An international organization or international o ...

signed in 1818 between the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

and the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and North ...

. This treaty resolved standing boundary issues between the two nations. The treaty allowed for joint occupation and settlement of the Oregon Country

Oregon Country was a large region of the Pacific Northwest of North America that was subject to a long dispute between the United Kingdom and the United States in the early 19th century. The area, which had been created by the Treaty of 1818, co ...

, known to the British and in Canadian history as the Columbia District

The Columbia District was a fur trading

The fur trade is a worldwide industry dealing in the acquisition and sale of animal fur. Since the establishment of a world fur market in the early modern period, furs of boreal, polar and cold ...

of the Hudson's Bay Company

The Hudson's Bay Company (HBC; french: Compagnie de la Baie d'Hudson) is a Canadian retail business group. A fur trading business for much of its existence, HBC now owns and operates retail stores in Canada. The company's namesake business div ...

, and including the southern portion of its sister district New Caledonia

)

, anthem = ""

, image_map = New Caledonia on the globe (small islands magnified) (Polynesia centered).svg

, map_alt = Location of New Caledonia

, map_caption = Location of New Caledonia

, mapsize = 290px

, subdivision_type = Sovereign st ...

.

The two nations agreed to a boundary line involving the 49th parallel north

The 49th parallel north is a circle of latitude that is 49 ° north of Earth's equator. It crosses Europe, Asia, the Pacific Ocean, North America, and the Atlantic Ocean.

The city of Paris is about south of the 49th parallel and is the large ...

, in part because a straight-line boundary would be easier to survey than the pre-existing boundaries based on watersheds. The treaty marked both the United Kingdom's last permanent major loss of territory in what is now the Continental United States

The contiguous United States (officially the conterminous United States) consists of the 48 adjoining U.S. states and the Federal District of the United States of America. The term excludes the only two non-contiguous states, Alaska and Hawaii ...

and the United States' first permanent significant cession of North American territory to a foreign power, the second being the Webster–Ashburton Treaty

The Webster–Ashburton Treaty, signed August 9, 1842, was a treaty that resolved several border issues between the United States and the British North American colonies (the region that became Canada). Signed under John Tyler's presidency, it ...

of 1842. The British ceded all of Rupert's Land

Rupert's Land (french: Terre de Rupert), or Prince Rupert's Land (french: Terre du Prince Rupert, link=no), was a territory in British North America which comprised the Hudson Bay drainage basin; this was further extended from Rupert's Land t ...

south of the 49th parallel and east of the Continental Divide

A continental divide is a drainage divide on a continent such that the drainage basin on one side of the divide feeds into one ocean or sea, and the basin on the other side either feeds into a different ocean or sea, or else is endorheic, not ...

, including all of the Red River Colony

The Red River Colony (or Selkirk Settlement), also known as Assiniboia, Assinboia, was a colonization project set up in 1811 by Thomas Douglas, 5th Earl of Selkirk, on of land in British North America. This land was granted to Douglas by the Hud ...

south of that latitude, while the United States ceded the northernmost edge of the Missouri Territory

The Territory of Missouri was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from June 4, 1812, until August 10, 1821. In 1819, the Territory of Arkansas was created from a portion of its southern area. In 1821, a southeas ...

north of the 49th parallel.

Provisions

The treaty name is variously cited as ''"Convention respecting fisheries, boundary, and the restoration of slaves"'', ''"Convention of Commerce (Fisheries, Boundary and the Restoration of Slaves)"'', and ''"Convention of Commerce between His Majesty and the United States of America"''. * Article I secured fishing rights alongNewfoundland

Newfoundland and Labrador (; french: Terre-Neuve-et-Labrador; frequently abbreviated as NL) is the easternmost province of Canada, in the country's Atlantic region. The province comprises the island of Newfoundland and the continental region ...

and Labrador

, nickname = "The Big Land"

, etymology =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Canada

, subdivision_type1 = Province

, subdivision_name1 ...

for the US.

* Article II set the boundary between British North America

British North America comprised the colonial territories of the British Empire in North America from 1783 onwards. English overseas possessions, English colonisation of North America began in the 16th century in Newfoundland (island), Newfound ...

and the United States along "a line drawn from the most northwestern point of the Lake of the Woods

The northwesternmost point of the Lake of the Woods was a critical landmark for the boundary between United States territory and the British possessions to the north. This point, on the shore of the Lake of the Woods, was referred to in the Treaty ...

, ue south, then Ue or UE may refer to:

Businesses and organizations Universities

* University of Edinburgh, a university in Scotland

* University of Exeter, a university in England

* University of the East, a university in the Philippines

* University of Evansvil ...

along the 49th parallel of north latitude..." to the "Stony Mountains" (now known as the Rocky Mountains

The Rocky Mountains, also known as the Rockies, are a major mountain range and the largest mountain system in North America. The Rocky Mountains stretch in straight-line distance from the northernmost part of western Canada, to New Mexico in ...

). Britain ceded all territory south of the 49th parallel, including portions of the Red River Colony

The Red River Colony (or Selkirk Settlement), also known as Assiniboia, Assinboia, was a colonization project set up in 1811 by Thomas Douglas, 5th Earl of Selkirk, on of land in British North America. This land was granted to Douglas by the Hud ...

and Rupert's Land

Rupert's Land (french: Terre de Rupert), or Prince Rupert's Land (french: Terre du Prince Rupert, link=no), was a territory in British North America which comprised the Hudson Bay drainage basin; this was further extended from Rupert's Land t ...

(comprising parts of the present states of Minnesota

Minnesota () is a state in the upper midwestern region of the United States. It is the 12th largest U.S. state in area and the 22nd most populous, with over 5.75 million residents. Minnesota is home to western prairies, now given over to ...

, North Dakota

North Dakota () is a U.S. state in the Upper Midwest, named after the Native Americans in the United States, indigenous Dakota people, Dakota Sioux. North Dakota is bordered by the Canadian provinces of Saskatchewan and Manitoba to the north a ...

, and South Dakota

South Dakota (; Sioux language, Sioux: , ) is a U.S. state in the West North Central states, North Central region of the United States. It is also part of the Great Plains. South Dakota is named after the Lakota people, Lakota and Dakota peo ...

). The United States ceded the portion of the Louisiana Purchase

The Louisiana Purchase (french: Vente de la Louisiane, translation=Sale of Louisiana) was the acquisition of the territory of Louisiana by the United States from the French First Republic in 1803. In return for fifteen million dollars, or app ...

lying north of the 49th parallel (the northernmost portion of the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson Bay drainage system. From its traditional source of Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota, it f ...

watershed, including those parts of the Milk River, Poplar River, and Big Muddy Creek watersheds in modern-day Alberta

Alberta ( ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is part of Western Canada and is one of the three prairie provinces. Alberta is bordered by British Columbia to the west, Saskatchewan to the east, the Northwest Ter ...

and Saskatchewan

Saskatchewan ( ; ) is a Provinces and territories of Canada, province in Western Canada, western Canada, bordered on the west by Alberta, on the north by the Northwest Territories, on the east by Manitoba, to the northeast by Nunavut, and on t ...

). The article settled a boundary dispute caused by ignorance of actual geography in the boundary agreed to in the 1783 Treaty of Paris Treaty of Paris may refer to one of many treaties signed in Paris, France:

Treaties

1200s and 1300s

* Treaty of Paris (1229), which ended the Albigensian Crusade

* Treaty of Paris (1259), between Henry III of England and Louis IX of France

* Trea ...

, which ended the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

. The earlier treaty had placed the boundary between the United States and British North America along a line extending westward from the Lake of the Woods to the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson Bay drainage system. From its traditional source of Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota, it f ...

. The parties did not realize that the river did not extend that far north and so such a line would never meet the river. In fixing the problem, the 1818 treaty created a pene-enclave

An enclave is a territory (or a small territory apart of a larger one) that is entirely surrounded by the territory of one other state or entity. Enclaves may also exist within territorial waters. ''Enclave'' is sometimes used improperly to deno ...

of the United States, the Northwest Angle

The Northwest Angle, known simply as the Angle by locals, and coextensive with Angle Township, is a pene-exclave of northern Lake of the Woods County, Minnesota. Except for surveying errors, it is the only place in the contiguous United State ...

, the small section of the present state of Minnesota

Minnesota () is a state in the upper midwestern region of the United States. It is the 12th largest U.S. state in area and the 22nd most populous, with over 5.75 million residents. Minnesota is home to western prairies, now given over to ...

that is the only part of the United States apart from Alaska that lies north of the 49th parallel.

*Article III provided for joint control of land in the Oregon Country

Oregon Country was a large region of the Pacific Northwest of North America that was subject to a long dispute between the United Kingdom and the United States in the early 19th century. The area, which had been created by the Treaty of 1818, co ...

for ten years. Both could claim land and were guaranteed free navigation throughout.

*Article IV confirmed the Anglo-American Convention of 1815, which regulated commerce between the two parties, for an additional ten years.

*Article V agreed to refer differences over a US claim arising from the Treaty of Ghent

The Treaty of Ghent () was the peace treaty that ended the War of 1812 between the United States and the United Kingdom. It took effect in February 1815. Both sides signed it on December 24, 1814, in the city of Ghent, United Netherlands (now in ...

, which ended the War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States of America and its indigenous allies against the United Kingdom and its allies in British North America, with limited participation by Spain in Florida. It bega ...

, to "some Friendly Sovereign or State to be named for that purpose." The claim in question was for the return of or compensation for American slaves

The legal institution of human chattel slavery, comprising the enslavement primarily of Africans and African Americans, was prevalent in the United States of America from its founding in 1776 until 1865, predominantly in the South. Sla ...

who had escaped to British-controlled territory or Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

warships when the treaty was signed. The article in question was about handing over property, and the US government claimed that the slaves were the property of its citizens.

*Article VI established that ratification would occur within six months of signing the treaty.

History

The treaty was negotiated for the US by

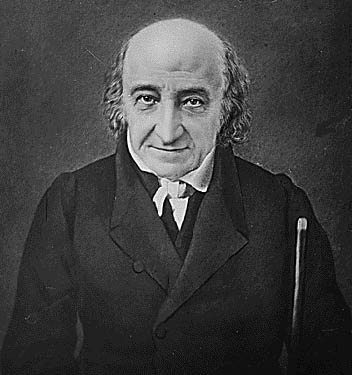

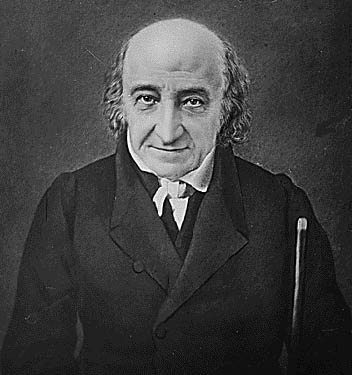

The treaty was negotiated for the US by Albert Gallatin

Abraham Alfonse Albert Gallatin (January 29, 1761 – August 12, 1849) was a Genevan– American politician, diplomat, ethnologist and linguist. Often described as "America's Swiss Founding Father", he was a leading figure in the early years ...

, ambassador to France, and Richard Rush, minister to the UK; and for the UK by Frederick John Robinson

Frederick John Robinson, 1st Earl of Ripon, (1 November 1782 – 28 January 1859), styled The Honourable F. J. Robinson until 1827 and known between 1827 and 1833 as The Viscount Goderich (pronounced ), the name by which he is best known to ...

, Treasurer of the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

and member of the privy council

A privy council is a body that advises the head of state of a state, typically, but not always, in the context of a monarchic government. The word "privy" means "private" or "secret"; thus, a privy council was originally a committee of the mon ...

, and Henry Goulburn

Henry Goulburn PC FRS (19 March 1784 – 12 January 1856) was a British Conservative statesman and a member of the Peelite faction after 1846.

Background and education

Born in London, Goulburn was the eldest son of a wealthy planter, Munbee ...

, an undersecretary of state. The treaty was signed on October 20, 1818. Ratifications were exchanged on January 30, 1819. The Convention of 1818, along with the Rush–Bagot Treaty

The Rush–Bagot Treaty or Rush–Bagot Disarmament was a treaty between the United States and Great Britain limiting naval armaments on the Great Lakes and Lake Champlain, following the War of 1812. It was ratified by the United States Senate o ...

of 1817, marked the beginning of improved relations between the British Empire and its former colonies, and paved the way for more positive relations between the US and Canada although repelling a US invasion was a defense priority in Canada until 1928.Preston, Richard A. ''The Defence of the Undefended Border: Planning for War in North America 1867–1939'', McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1977

Despite the relatively friendly nature of the agreement, it resulted in a fierce struggle for control of the Oregon Country for the following two decades. The British-chartered Hudson's Bay Company, having previously established a trading network centered on Fort Vancouver

Fort Vancouver was a 19th century fur trading post that was the headquarters of the Hudson's Bay Company's Columbia Department, located in the Pacific Northwest. Named for Captain George Vancouver, the fort was located on the northern bank of th ...

on the lower Columbia River, with other forts in what is now eastern Washington and Idaho as well as on the Oregon Coast and in Puget Sound, undertook a harsh campaign to restrict encroachment by US fur traders to the area. By the 1830s, with pressure in the US mounting to annex the region outright, the company undertook a deliberate policy to exterminate all fur-bearing animals from the Oregon Country to maximize its remaining profit and to delay the arrival of US mountain men and settlers. The policy of discouraging settlement was undercut to some degree by the actions of John McLoughlin

John McLoughlin, baptized Jean-Baptiste McLoughlin, (October 19, 1784 – September 3, 1857) was a French-Canadian, later American, Chief Factor and Superintendent of the Columbia District of the Hudson's Bay Company at Fort Vancouver fro ...

, Chief Factor of the Hudson's Bay Company at Fort Vancouver, who regularly provided relief and welcome to US immigrants who had arrived at the post over the Oregon Trail

The Oregon Trail was a east–west, large-wheeled wagon route and Westward Expansion Trails, emigrant trail in the United States that connected the Missouri River to valleys in Oregon. The eastern part of the Oregon Trail spanned part of what ...

.

By the mid-1840s, the tide of US immigration, as well as a US political movement to claim the entire territory, led to a renegotiation of the agreement. The Oregon Treaty

The Oregon Treaty is a treaty between the United Kingdom and the United States that was signed on June 15, 1846, in Washington, D.C. The treaty brought an end to the Oregon boundary dispute by settling competing American and British claims to t ...

in 1846 permanently established the 49th parallel as the boundary between the United States and British North America to the Pacific Ocean.

See also

*Adams–Onís Treaty

The Adams–Onís Treaty () of 1819, also known as the Transcontinental Treaty, the Florida Purchase Treaty, or the Florida Treaty,Weeks, p.168. was a treaty between the United States and Spain in 1819 that ceded Florida to the U.S. and defined t ...

of 1819, between the U.S. and Spain, resolved borders from Florida to the Pacific Ocean.

* The Webster–Ashburton Treaty

The Webster–Ashburton Treaty, signed August 9, 1842, was a treaty that resolved several border issues between the United States and the British North American colonies (the region that became Canada). Signed under John Tyler's presidency, it ...

of 1842 resolved uncertainties left by the 1818 treaty, including the Northwest Angle problem, which had been created by the use of a faulty map.

* Oregon boundary dispute

The Oregon boundary dispute or the Oregon Question was a 19th-century territorial dispute over the political division of the Pacific Northwest of North America between several nations that had competing territorial and commercial aspirations in ...

, concerning the joint occupation of the Oregon Country by U.S. and British settlers.

* Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo ( es, Tratado de Guadalupe Hidalgo), officially the Treaty of Peace, Friendship, Limits, and Settlement between the United States of America and the United Mexican States, is the peace treaty that was signed on 2 ...

, which established most of the southern border between the US and Mexico after the defeat and occupation of Mexico in 1848, ending the Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War, also known in the United States as the Mexican War and in Mexico as the (''United States intervention in Mexico''), was an armed conflict between the United States and Mexico from 1846 to 1848. It followed the 1 ...

.

* The Gadsden Purchase, which completed the acquisition of the southwestern United States and completed the border between Mexico and the US in 1853 at the 32nd parallel and the Rio Grande

The Rio Grande ( and ), known in Mexico as the Río Bravo del Norte or simply the Río Bravo, is one of the principal rivers (along with the Colorado River) in the southwestern United States and in northern Mexico.

The length of the Rio G ...

.

References

External links

* This article traces British-United States negotiations regardingocean fisheries A fishery is an area with an associated fish or aquatic population which is harvested for its commercial value. Fisheries can be wild or farmed. Most of the world's wild fisheries are in the ocean. This article is an overview of ocean fisheries.

S ...

from 1783 to 1910.

{{DEFAULTSORT:Treaty Of 1818

1818 in the United Kingdom

1818 in the United States

Canada–United States border

Pre-statehood history of Oregon

Oregon Country

Legal history of Canada

Boundary treaties

1818

Pre-Confederation British Columbia

Pre-statehood history of Minnesota

1818 treaties

15th United States Congress

United States slavery law

United Kingdom–United States treaties

Treaties of the United Kingdom (1801–1922)

October 1818 events