Transatlantic Flight Of Alcock And Brown on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

British aviators John Alcock and Arthur Brown made the first non-stop

British aviators John Alcock and Arthur Brown made the first non-stop

Several teams had entered the competition and, when Alcock and Brown arrived in St. John's, Newfoundland, the

Several teams had entered the competition and, when Alcock and Brown arrived in St. John's, Newfoundland, the  Alcock and Brown were treated as heroes on the completion of their flight. In addition to a share of the ''Daily Mail'' award of £10,000, Alcock received 2,000

Alcock and Brown were treated as heroes on the completion of their flight. In addition to a share of the ''Daily Mail'' award of £10,000, Alcock received 2,000

Two memorials commemorating the flight are sited near the landing spot in County Galway, Ireland. The first is an isolated cairn four kilometres south of Clifden on the site of Marconi's first transatlantic wireless station from which the aviators transmitted their success to London, and around from the spot where they landed. In addition there is a sculpture of an aircraft's tail-fin on Errislannan Hill two kilometres north of their landing spot, dedicated on the fortieth anniversary of their landing, 15 June 1959.

Two memorials commemorating the flight are sited near the landing spot in County Galway, Ireland. The first is an isolated cairn four kilometres south of Clifden on the site of Marconi's first transatlantic wireless station from which the aviators transmitted their success to London, and around from the spot where they landed. In addition there is a sculpture of an aircraft's tail-fin on Errislannan Hill two kilometres north of their landing spot, dedicated on the fortieth anniversary of their landing, 15 June 1959.

Three monuments mark the flight's starting point in Newfoundland. One was erected by the Government of Canada in 1952 at the junction of Lemarchant Road and Patrick Street in St. John's, a second monument is located on Lemarchant Road, while the third was unveiled by Premier of Newfoundland and Labrador

Three monuments mark the flight's starting point in Newfoundland. One was erected by the Government of Canada in 1952 at the junction of Lemarchant Road and Patrick Street in St. John's, a second monument is located on Lemarchant Road, while the third was unveiled by Premier of Newfoundland and Labrador  A memorial statue was erected at

A memorial statue was erected at

To mark the original transatlantic crossing, on 1 June 1979 two

To mark the original transatlantic crossing, on 1 June 1979 two

Alcock and Brown at "Flights of Inspiration"

Alcock and Brown's plane at the London Science Museum

Brooklands Museum website

Colum McCann fiction short story based on Alcock and Brown's flight

a 1919 ''Flight'' article on the flight {{Aviation accidents and incidents in the United Kingdom Aviation history of the United Kingdom Aviation history of Canada Transatlantic flight Aviation accidents and incidents in Ireland History of St. John's, Newfoundland and Labrador 1919 in aviation 1919 in the United Kingdom 1919 in Canada

British aviators John Alcock and Arthur Brown made the first non-stop

British aviators John Alcock and Arthur Brown made the first non-stop transatlantic flight

A transatlantic flight is the flight of an aircraft across the Atlantic Ocean from Europe, Africa, South Asia, or the Middle East to North America, Central America, or South America, or ''vice versa''. Such flights have been made by fixed-wing air ...

in June 1919. They flew a modified First World War Vickers Vimy bomber from St. John's, Newfoundland

Newfoundland and Labrador (; french: Terre-Neuve-et-Labrador; frequently abbreviated as NL) is the easternmost province of Canada, in the country's Atlantic region. The province comprises the island of Newfoundland and the continental region ...

, to Clifden, County Galway

"Righteousness and Justice"

, anthem = ()

, image_map = Island of Ireland location map Galway.svg

, map_caption = Location in Ireland

, area_footnotes =

, area_total_km2 = ...

, Ireland. The Secretary of State for Air

The Secretary of State for Air was a secretary of state position in the British government, which existed from 1919 to 1964. The person holding this position was in charge of the Air Ministry. The Secretary of State for Air was supported by ...

, Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from ...

, presented them with the ''Daily Mail'' prize for the first crossing of the Atlantic Ocean by aeroplane

An airplane or aeroplane (informally plane) is a fixed-wing aircraft that is propelled forward by thrust from a jet engine, propeller, or rocket engine. Airplanes come in a variety of sizes, shapes, and wing configurations. The broad spec ...

in "less than 72 consecutive hours." A small amount of mail was carried on the flight, making it the first transatlantic airmail flight. The two aviators were awarded the honour of Knight Commander of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire (KBE) by King George V

George V (George Frederick Ernest Albert; 3 June 1865 – 20 January 1936) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 until his death in 1936.

Born during the reign of his grandmother Qu ...

at Windsor Castle

Windsor Castle is a royal residence at Windsor in the English county of Berkshire. It is strongly associated with the English and succeeding British royal family, and embodies almost a millennium of architectural history.

The original c ...

a week later.

Background

John Alcock was born in 1892 in Basford House on Seymour Grove,Firswood

Firswood is a suburban area of Stretford in the Metropolitan Borough of Trafford, Greater Manchester, England.

Geography

Firswood borders Whalley Range, Old Trafford and Chorlton-cum-Hardy. It was largely occupied by Rye Bank Farm, which remaine ...

, Manchester

Manchester () is a city in Greater Manchester, England. It had a population of 552,000 in 2021. It is bordered by the Cheshire Plain to the south, the Pennines to the north and east, and the neighbouring city of Salford to the west. The ...

, England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe ...

. Known to his family and friends as "Jack", he first became interested in flying at the age of seventeen and gained his pilot's licence in November 1912. Alcock was a regular competitor in aircraft competitions at Hendon

Hendon is an urban area in the Borough of Barnet, North-West London northwest of Charing Cross. Hendon was an ancient manor and parish in the county of Middlesex and a former borough, the Municipal Borough of Hendon; it has been part of Gre ...

in 1913–14. He became a military pilot during the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

and was taken prisoner

A prisoner (also known as an inmate or detainee) is a person who is deprived of liberty against their will. This can be by confinement, captivity, or forcible restraint. The term applies particularly to serving a prison sentence in a prison. ...

in Turkey

Turkey ( tr, Türkiye ), officially the Republic of Türkiye ( tr, Türkiye Cumhuriyeti, links=no ), is a transcontinental country located mainly on the Anatolian Peninsula in Western Asia, with a small portion on the Balkan Peninsula ...

after his Handley Page bomber was shot down over the sea. After the war, Alcock wanted to continue his flying career and took up the challenge of attempting to be the first to fly directly across the Atlantic

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the " Old World" of Africa, Europe ...

.

Arthur Whitten Brown was born in Glasgow

Glasgow ( ; sco, Glesca or ; gd, Glaschu ) is the most populous city in Scotland and the fourth-most populous city in the United Kingdom, as well as being the 27th largest city by population in Europe. In 2020, it had an estimated popu ...

, Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to ...

in 1886 and shortly afterwards the family moved to Manchester. Known to his family and friends as "Teddie", he began his career in engineering before the outbreak of the First World War.

In April 1913 the London newspaper the ''Daily Mail'' offered a prize of £10,000 to

The competition was suspended with the outbreak of war in 1914 but reopened after Armistice

An armistice is a formal agreement of warring parties to stop fighting. It is not necessarily the end of a war, as it may constitute only a cessation of hostilities while an attempt is made to negotiate a lasting peace. It is derived from the ...

was declared in 1918.

Brown became a prisoner of war after being shot down over Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwee ...

. Alcock, too, was imprisoned and had resolved to fly the Atlantic one day. As Brown continued developing his aerial navigation skills, Alcock approached the Vickers

Vickers was a British engineering company that existed from 1828 until 1999. It was formed in Sheffield as a steel foundry by Edward Vickers and his father-in-law, and soon became famous for casting church bells. The company went public i ...

engineering and aviation firm at Weybridge

Weybridge () is a town in the Borough of Elmbridge in Surrey, England, around southwest of central London. The settlement is recorded as ''Waigebrugge'' and ''Weibrugge'' in the 7th century and the name derives from a crossing point of the ...

, who had considered entering their Vickers Vimy IV twin-engined bomber in the competition but had not yet found a pilot. The Vimy had originally been manufactured at Vickers in Crayford, the first twelve being made there and tested at Joyce Green airfield, Dartford. It was a great inconvenience to have to dismantle the aircraft to move them to Joyce Green so production was moved to Weybridge. The thirteenth Vimy assembled was the one used for the trans-Atlantic crossing. Alcock said 13 was his lucky number. Sir Henry Norman got involved in the detailed planning for a proposed transatlantic flight using the F.B.27. This planning included the route to be flown and of course, the hangar facilities and the provision of fuel needed for preparation of the aircraft in Newfoundland.

Alcock's enthusiasm impressed the Vickers' team and he was appointed as their pilot. Work began on converting the Vimy for the long flight, replacing the bomb racks with extra petrol tanks. Shortly afterwards, Brown, who was unemployed, approached Vickers seeking a post and his knowledge of long-distance navigation persuaded them to take him on as Alcock's navigator.

Flight

Several teams had entered the competition and, when Alcock and Brown arrived in St. John's, Newfoundland, the

Several teams had entered the competition and, when Alcock and Brown arrived in St. John's, Newfoundland, the Handley Page

Handley Page Limited was a British aerospace manufacturer. Founded by Frederick Handley Page (later Sir Frederick) in 1909, it was the United Kingdom's first publicly traded aircraft manufacturing company. It went into voluntary liquidatio ...

team were in the final stages of testing their aircraft for the flight, but their leader, Admiral Mark Kerr, was determined not to take off until the plane was in perfect condition. The Vickers team quickly assembled their plane and, at around 1:45 p.m. on 14 June, whilst the Handley Page team were conducting yet another test, the Vickers plane took off from Lester's Field. Alcock and Brown flew the modified Vickers Vimy, powered by two Rolls-Royce Eagle

The Rolls-Royce Eagle was the first aircraft engine to be developed by Rolls-Royce Limited. Introduced in 1915 to meet British military requirements during World War I, it was used to power the Handley Page Type O bombers and a number of oth ...

360 hp engines which were supported by an on-site Rolls-Royce team led by engineer Eric Platford

Eric Platford (1883 - 20 November 1938) was an English engineer and a Rolls-Royce pioneer. Platford had an illustrious career with Rolls-Royce.

Platford was employed by Henry Royce and assisted in the construction of Royce's first car from his ...

. The pair brought toy cat mascots with them for the flight – Alcock had 'Lucky Jim' while Brown had 'Twinkletoes'.

It was not an easy flight. The overloaded aircraft had difficulty taking off the rough field and only barely missed the tops of the trees.

At 17:20 the wind-driven electrical generator failed, depriving them of radio contact, their intercom and heating.

An exhaust pipe burst shortly afterwards, causing a frightening noise which made conversation impossible without the failed intercom.

At 5.00 p.m., they had to fly through thick fog. This was serious because it prevented Brown from being able to navigate using his sextant.

Blind flying in fog or cloud should only be undertaken with gyroscopic instruments, which they did not have. Alcock twice lost control of the aircraft and nearly hit the sea after a spiral dive. He also had to deal with a broken trim control that made the plane become very nose-heavy as fuel was consumed.

At 12:15 a.m., Brown got a glimpse of the stars and could use his sextant and found that they were on course. Their electric heating suits had failed, making them very cold in the open cockpit.

Then at 3:00 a.m., they flew into a large snowstorm. They were drenched by rain, their instruments iced up, and the plane was in danger of icing and becoming unflyable. The carburettors also iced up; it has been said that Brown had to climb out onto the wings to clear the engines, although he made no mention of that.

They made landfall in County Galway

"Righteousness and Justice"

, anthem = ()

, image_map = Island of Ireland location map Galway.svg

, map_caption = Location in Ireland

, area_footnotes =

, area_total_km2 = ...

, landing at 8:40 a.m. on 15 June 1919, not far from their intended landing place, after less than sixteen hours' flying time.

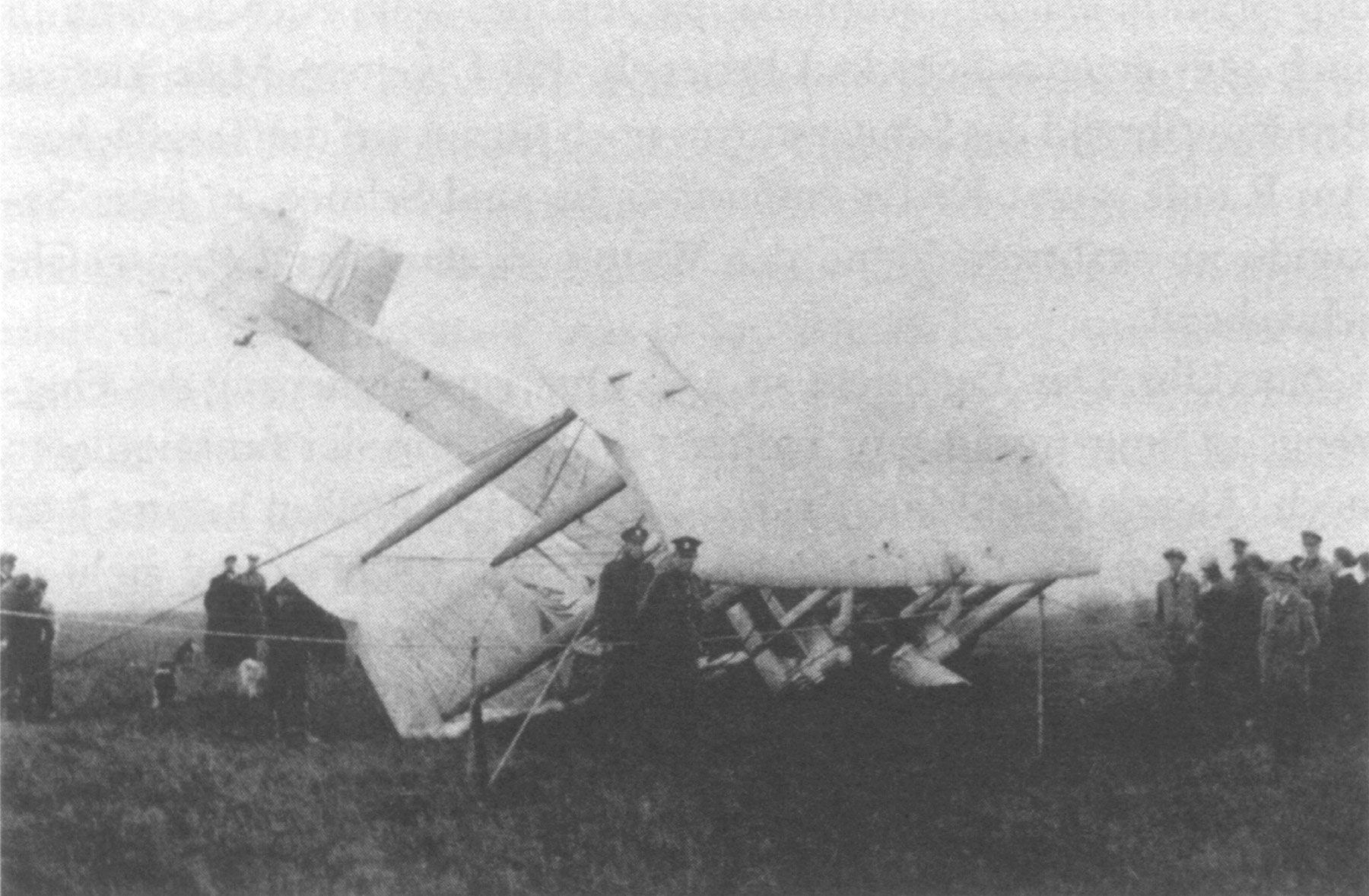

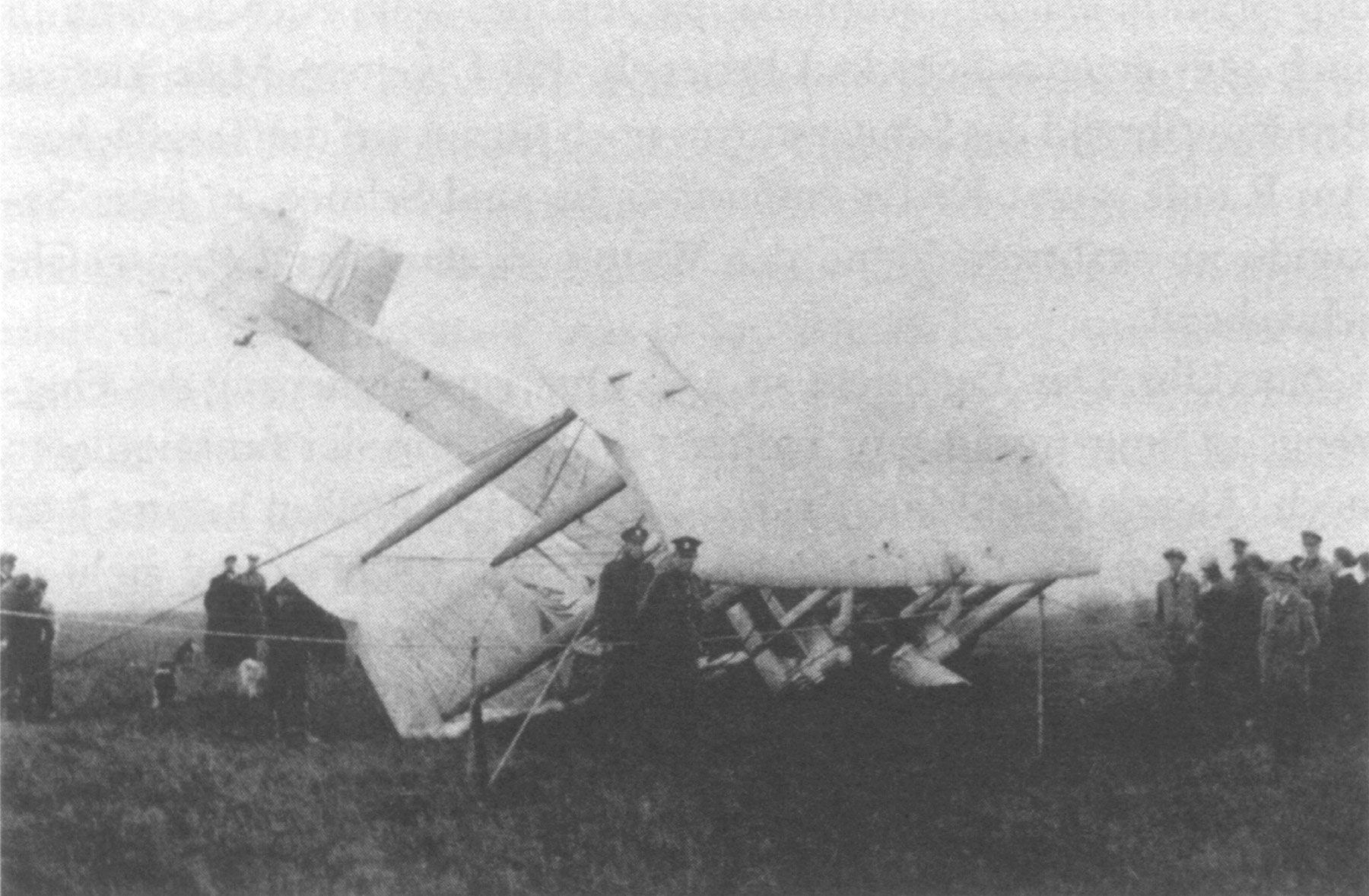

The aircraft was damaged upon arrival because they landed on what appeared from the air to be a suitable green field, but which turned out to be Derrigimlagh Bog

A bog or bogland is a wetland that accumulates peat as a deposit of dead plant materials often mosses, typically sphagnum moss. It is one of the four main types of wetlands. Other names for bogs include mire, mosses, quagmire, and muskeg; a ...

, near Clifden in County Galway in Ireland. This caused the aircraft to nose-over, although neither of the airmen was hurt.

Brown said that if the weather had been good, they could have pressed on to London.

Their altitude varied between sea level and 12,000 ft (3,700 m). They took off with 865 imperial gallon

The gallon is a unit of volume in imperial units and United States customary units. Three different versions are in current use:

*the imperial gallon (imp gal), defined as , which is or was used in the United Kingdom, Ireland, Canada, Austral ...

s (3,900 L) of fuel. They had spent around fourteen-and-a-half hours over the North Atlantic crossing the coast at 4:28 p.m., having flown 1,890 miles (3,040 km) in 15 hours 57 minutes at an average speed of 115 mph (185 km/h; 100 knots

A knot is a fastening in rope or interwoven lines.

Knot may also refer to:

Places

* Knot, Nancowry, a village in India

Archaeology

* Knot of Isis (tyet), symbol of welfare/life.

* Minoan snake goddess figurines#Sacral knot

Arts, entertainme ...

). Their first interview was given to Tom 'Cork' Kenny of '' The Connacht Tribune''.

Alcock and Brown were treated as heroes on the completion of their flight. In addition to a share of the ''Daily Mail'' award of £10,000, Alcock received 2,000

Alcock and Brown were treated as heroes on the completion of their flight. In addition to a share of the ''Daily Mail'' award of £10,000, Alcock received 2,000 guineas

The guinea (; commonly abbreviated gn., or gns. in plural) was a coin, minted in Great Britain between 1663 and 1814, that contained approximately one-quarter of an ounce of gold. The name came from the Guinea region in West Africa, from where m ...

(£2,100) from the State Express Cigarette Company and £1,000 from Laurence R Philipps for being the first Briton to fly the Atlantic Ocean. Both men were knighted a few days later by King George V

George V (George Frederick Ernest Albert; 3 June 1865 – 20 January 1936) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 until his death in 1936.

Born during the reign of his grandmother Qu ...

.

Alcock and Brown flew to Manchester

Manchester () is a city in Greater Manchester, England. It had a population of 552,000 in 2021. It is bordered by the Cheshire Plain to the south, the Pennines to the north and east, and the neighbouring city of Salford to the west. The ...

on 17 July 1919, where they were given a civic reception by the Lord Mayor and Corporation

A corporation is an organization—usually a group of people or a company—authorized by the state to act as a single entity (a legal entity recognized by private and public law "born out of statute"; a legal person in legal context) and ...

, and awards to mark their achievement.

Memorials

Alcock was killed on 18 December 1919 when he crashed nearRouen

Rouen (, ; or ) is a city on the River Seine in northern France. It is the prefecture of the region of Normandy and the department of Seine-Maritime. Formerly one of the largest and most prosperous cities of medieval Europe, the population ...

whilst flying the new Vickers Viking

The Vickers Viking was a British single-engine amphibious aircraft designed for military use shortly after World War I. Later versions of the aircraft were known as the Vickers Vulture and Vickers Vanellus.

Design and development

Resear ...

amphibian to the Paris Airshow. Brown died on 4 October 1948.

Two memorials commemorating the flight are sited near the landing spot in County Galway, Ireland. The first is an isolated cairn four kilometres south of Clifden on the site of Marconi's first transatlantic wireless station from which the aviators transmitted their success to London, and around from the spot where they landed. In addition there is a sculpture of an aircraft's tail-fin on Errislannan Hill two kilometres north of their landing spot, dedicated on the fortieth anniversary of their landing, 15 June 1959.

Two memorials commemorating the flight are sited near the landing spot in County Galway, Ireland. The first is an isolated cairn four kilometres south of Clifden on the site of Marconi's first transatlantic wireless station from which the aviators transmitted their success to London, and around from the spot where they landed. In addition there is a sculpture of an aircraft's tail-fin on Errislannan Hill two kilometres north of their landing spot, dedicated on the fortieth anniversary of their landing, 15 June 1959.

Three monuments mark the flight's starting point in Newfoundland. One was erected by the Government of Canada in 1952 at the junction of Lemarchant Road and Patrick Street in St. John's, a second monument is located on Lemarchant Road, while the third was unveiled by Premier of Newfoundland and Labrador

Three monuments mark the flight's starting point in Newfoundland. One was erected by the Government of Canada in 1952 at the junction of Lemarchant Road and Patrick Street in St. John's, a second monument is located on Lemarchant Road, while the third was unveiled by Premier of Newfoundland and Labrador Joey Smallwood

Joseph Roberts Smallwood (December 24, 1900 – December 17, 1991) was a Newfoundlander and Canadian politician. He was the main force who brought the Dominion of Newfoundland into Canadian Confederation in 1949, becoming the first premier of ...

on Blackmarsh Road.

A memorial statue was erected at

A memorial statue was erected at London Heathrow Airport

Heathrow Airport (), called ''London Airport'' until 1966 and now known as London Heathrow , is a major international airport in London, England. It is the largest of the six international airports in the London airport system (the others be ...

in 1954 to celebrate their flight. There is also a monument at Manchester Airport

Manchester Airport is an international airport in Ringway, Manchester, England, south-west of Manchester city centre. In 2019, it was the third busiest airport in the United Kingdom in terms of passenger numbers and the busiest of those ...

, less than 8 miles from John Alcock's birthplace. Their aircraft (rebuilt by the Vickers Company) is located in the Science Museum

A science museum is a museum devoted primarily to science. Older science museums tended to concentrate on static displays of objects related to natural history, paleontology, geology, industry and industrial machinery, etc. Modern trends in ...

in South Kensington

South Kensington, nicknamed Little Paris, is a district just west of Central London in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea. Historically it settled on part of the scattered Middlesex village of Brompton. Its name was supplanted with ...

, London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

.

The Royal Mail

, kw, Postya Riel, ga, An Post Ríoga

, logo = Royal Mail.svg

, logo_size = 250px

, type = Public limited company

, traded_as =

, foundation =

, founder = Henry VIII

, location = London, England, UK

, key_people = * Keith Williams ...

issued a 5d (approximately 2.1p in modern UK currency) stamp

Stamp or Stamps or Stamping may refer to:

Official documents and related impressions

* Postage stamp, used to indicate prepayment of fees for public mail

* Ration stamp, indicating the right to rationed goods

* Revenue stamp, used on documents ...

commemorating the 50th anniversary of the flight on 2 April 1969.

In June 2019, the Central Bank of Ireland

The Central Bank of Ireland ( ga, Banc Ceannais na hÉireann) is Ireland's central bank, and as such part of the European System of Central Banks (ESCB). It is the country's financial services regulator for most categories of financial firms ...

issued 3,000 €15 silver commemorative coins, commemorating the 100th anniversary of the flight.

From April to October 2019 various events were held in Crayford and Bexley to commemorate the Centenary of the flight, and the visit of Alcock and Brown to Crayford in July 1919 when they were surprise guests at the reopening of The Princesses Theatre by the Duke of York (later King George VI). The events included talks, exhibitions, a celebration day at Hall Place and Gardens attended by c3,500 people, and chiefly a visit by the Duke of Kent to unveil a new bench in the centre of Crayford with a life size Alcock and Brown seated at each end, and to view public artwork designed by local schools.

Memorabilia

On 19 March 2017 an edition of the ''Antiques Roadshow

''Antiques Roadshow'' is a British television programme broadcast by the BBC in which antiques appraisers travel to various regions of the United Kingdom (and occasionally in other countries) to appraise antiques brought in by local people ( ...

'' was broadcast in the UK in which the granddaughter of Alcock's cousin presented a handwritten note which was carried by Alcock on the flight. The note, which was valued at £1,000–£1,200, read as follows:

Other crossings

Two weeks before Alcock and Brown's flight, the first 'stopping' flight of the Atlantic had been made by the NC-4, aUnited States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

flying boat

A flying boat is a type of fixed-winged seaplane with a hull, allowing it to land on water. It differs from a floatplane in that a flying boat's fuselage is purpose-designed for floatation and contains a hull, while floatplanes rely on fuselag ...

, commanded by Lt. Commander Albert Cushing Read

Albert Cushing Read, Sr. (March 29, 1887 – October 10, 1967) was an aviator and Rear Admiral in the United States Navy. He and his crew made the first transatlantic flight in the ''NC-4'', a Curtiss NC flying boat.

Early life and Atlantic cros ...

, who flew from Naval Air Station Rockaway, New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

to Plymouth

Plymouth () is a port city status in the United Kingdom, city and unitary authority in South West England. It is located on the south coast of Devon, approximately south-west of Exeter and south-west of London. It is bordered by Cornwall to ...

with a crew of five, over 23 days, with six stops along the way. This flight was not eligible for the ''Daily Mail'' prize since it took more than 72 consecutive hours and also because more than one aircraft was used in the attempt.

A month after Alcock and Brown's achievement, British airship R34 made the first double crossing of the Atlantic. Leaving England July 2, it arrived July 4 carrying 31 people (one a stowaway) and a cat. For the return flight, 29 of this crew, plus two flight engineers and a different American observer, returned to Europe.

On 2–3 July 2005, American adventurer Steve Fossett

James Stephen Fossett (April 22, 1944 – September 3, 2007) was an American businessman and a record-setting aviator, sailor, and adventurer. He was the first person to fly solo nonstop around the world in a balloon and in a fixed-wing aircraf ...

and co-pilot Mark Rebholz recreated the flight in a replica of the Vickers Vimy aeroplane. They did not land in the bog near Clifden, but a few miles away on the Connemara

Connemara (; )( ga, Conamara ) is a region on the Atlantic coast of western County Galway, in the west of Ireland. The area has a strong association with traditional Irish culture and contains much of the Connacht Irish-speaking Gaeltacht, ...

golf course.

A replica Vimy, NX71MY, was built in Australia and the US in 1994 for an American, Peter McMillan, who flew it from England to Australia with Australian Lang Kidby in 1994 to re-enact the first England-Australia flight by Ross & Keith Smith with Vimy G-EAOU in 1919. In 1999, Mark Rebholz and John LaNoue re-enacted the first flight from London to Cape Town

Cape Town ( af, Kaapstad; , xh, iKapa) is one of South Africa's three capital cities, serving as the seat of the Parliament of South Africa. It is the legislative capital of the country, the oldest city in the country, and the second largest ...

with this same replica, and in late 2006 the aeroplane was donated to Brooklands Museum

Brooklands Museum is a motoring and aviation museum occupying part of the former Brooklands motor-racing track in Weybridge, Surrey, England.

Formally opened in 1991, the museum is operated by the independent Brooklands Museum Trust Ltd, a pri ...

at Weybridge

Weybridge () is a town in the Borough of Elmbridge in Surrey, England, around southwest of central London. The settlement is recorded as ''Waigebrugge'' and ''Weibrugge'' in the 7th century and the name derives from a crossing point of the ...

, Surrey

Surrey () is a ceremonial county, ceremonial and non-metropolitan county, non-metropolitan counties of England, county in South East England, bordering Greater London to the south west. Surrey has a large rural area, and several significant ur ...

. After making a special Alcock and Brown 90th anniversary return visit to Clifden in June 2009 (flown by John Dodd and Clive Edwards), and some final public flying displays at the Goodwood Revival that September, the Vimy made its final flight on 15 November 2009 from Dunsfold Park to Brooklands

Brooklands was a motor racing circuit and aerodrome built near Weybridge in Surrey, England, United Kingdom. It opened in 1907 and was the world's first purpose-built 'banked' motor racing circuit as well as one of Britain's first airfields ...

crewed by John Dodd (pilot), Clive Edwards and Peter McMillan. It is now on public display as the centre-piece of a new 'First to the Fastest' Transatlantic flight exhibition in the Museum's Vimy Pavilion but is maintained as a 'live' aeroplane and occasionally performs engine ground running demonstrations outside.

One of the propellers from the Vickers Vimy was given to Arthur Whitten Brown and hung for many years on the wall of his office in Swansea

Swansea (; cy, Abertawe ) is a coastal city and the second-largest city of Wales

Wales ( cy, Cymru ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is bordered by England to the east, the Irish Sea to the north and west, the C ...

before he presented it to the RAF College Cranwell

The Royal Air Force College (RAFC) is the Royal Air Force military academy which provides initial training to all RAF personnel who are preparing to become commissioned officers. The College also provides initial training to aircrew cadets and ...

. It is believed to have been displayed in the RAF Careers Office in Holborn

Holborn ( or ) is a district in central London, which covers the south-eastern part of the London Borough of Camden and a part ( St Andrew Holborn Below the Bars) of the Ward of Farringdon Without in the City of London.

The area has its ro ...

until 1990. It is believed to be in use today as a ceiling fan in Luigi Malone's Restaurant in Cork

Cork or CORK may refer to:

Materials

* Cork (material), an impermeable buoyant plant product

** Cork (plug), a cylindrical or conical object used to seal a container

***Wine cork

Places Ireland

* Cork (city)

** Metropolitan Cork, also known as G ...

, Ireland.

The other propeller, serial number G1184.N6, was originally given to the Vickers Works Manager at Brooklands, Percy Maxwell Muller and displayed for many years suspended inside the transatlantic terminal ( Terminal 3) at London's Heathrow Airport

Heathrow Airport (), called ''London Airport'' until 1966 and now known as London Heathrow , is a major international airport in London, England. It is the largest of the six international airports in the London airport system (the others be ...

. In October 1990 it was donated by the BAA (via its former chairman, Sir Peter Masefield

Sir Peter Masefield (19 March 1914 - 14 February 2006) was a leading figure in Britain's post war aviation industry, as Chief Executive of British European Airways in the 1950s, and chairman of the British Airports Authority in the 1960s.

Histor ...

) to Brooklands Museum, where it is now displayed as part of a full-size Vimy wall mural in the Vickers Building.

A small amount of mail, 196 letters and a parcel, was carried on Alcock and Brown's flight, the first time mail was carried by air across the ocean. The government of the Dominion of Newfoundland

Newfoundland was a British dominion in eastern North America, today the modern Canadian province of Newfoundland and Labrador. It was established on 26 September 1907, and confirmed by the Balfour Declaration of 1926 and the Statute of Westmi ...

overprinted

An overprint is an additional layer of text or graphics added to the face of a postage or revenue stamp, postal stationery, banknote or ticket after it has been printed. Post offices most often use overprints for internal administrative purpos ...

stamps for this carriage with the inscription "Transatlantic air post 1919".

Upon landing in Paris after his own record breaking flight in 1927, Charles Lindbergh

Charles Augustus Lindbergh (February 4, 1902 – August 26, 1974) was an American aviator, military officer, author, inventor, and activist. On May 20–21, 1927, Lindbergh made the first nonstop flight from New York City to Paris, a distance o ...

told the crowd welcoming him that "Alcock and Brown showed me the way!"

RAF 60th anniversary crossing in 1979

To mark the original transatlantic crossing, on 1 June 1979 two

To mark the original transatlantic crossing, on 1 June 1979 two Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) an ...

McDonnell Douglas Phantom FGR.2s – XV424 (of No. 56 Squadron) and (RAF Coningsby

Royal Air Force Coningsby or RAF Coningsby , is a Royal Air Force (RAF) station located south-west of Horncastle, and north-west of Boston, in the East Lindsey district of Lincolnshire, England. It is a Main Operating Base of the RAF and ho ...

based) XV486, were painted in special commemorative schemes. The scheme was designed by aviation artist Wilfred Hardy. As well as marking the anniversary of the crossing, the scheme also made reference to usage of Rolls-Royce engines in both aircraft: the Rolls-Royce Eagle in the Vimy and the Rolls-Royce Spey

The Rolls-Royce Spey (company designations RB.163 and RB.168 and RB.183) is a low-bypass turbofan engine originally designed and manufactured by Rolls-Royce that has been in widespread service for over 40 years. A co-development version of th ...

in the Phantom FGR.2, and on top of this it also marked the 30th anniversary of North Atlantic Treaty Organization

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO, ; french: Organisation du traité de l'Atlantique nord, ), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental military alliance between 30 member states – 28 European and two No ...

(NATO).

It was decided that XV424 would make the flight and that XV486 would serve as backup. On 19 June, XV424 departed from RAF St. Athan to CFB Goose Bay

Canadian Forces Base Goose Bay , commonly referred to as CFB Goose Bay, is a Canadian Forces Base located in the municipality of Happy Valley-Goose Bay in the province of Newfoundland and Labrador. It is operated as an air force base by ...

from where the crossing would be made. The crew chosen for the crossing were: Squadron Leader A. J. N. "Tony" Alcock (pilot and nephew of Sir John Alcock who made the original crossing) and Flight Lieutenant W. N. "Norman" Browne (navigator). For the journey the pair brought with them Brown's original cat toy mascot 'Twinkletoes.'

On 21 June, XV424 took off from Goose Bay, Labrador

, nickname = "The Big Land"

, etymology =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Canada

, subdivision_type1 = Province

, subdivision_name1 ...

and began the crossing to Ireland. Flying subsonically the entire time, the journey took 5 hours and 40 minutes, setting The Phantom was refuelled five times throughout the crossing, with that being taken care of by Handley-Page Victor

The Handley Page Victor is a British jet-powered strategic bomber developed and produced by Handley Page during the Cold War. It was the third and final ''V bomber'' to be operated by the Royal Air Force (RAF), the other two being the Avro V ...

K.2 tankers of No. 57 Squadron. XV424 today is preserved at the RAF Museum in Hendon

Hendon is an urban area in the Borough of Barnet, North-West London northwest of Charing Cross. Hendon was an ancient manor and parish in the county of Middlesex and a former borough, the Municipal Borough of Hendon; it has been part of Gre ...

, sporting colours of No. 56 (Fighter) Squadron, while XV486 was scrapped in 1993.

See also

* Curtiss NC-4 – First transatlantic flight via Azores to Portugal *Daily Mail Trans-Atlantic Air Race

The Daily Mail Trans-Atlantic Air Race was a race between London, UK and New York City, USA to commemorate the 50th Anniversary of the first trans-atlantic crossing by John Alcock and Arthur Brown.

The race

Organised by the ''Daily Mail'' newsp ...

– An event to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the flight

* Felixstowe Fury

The Felixstowe F.4 Fury ( serial ''N123''), also known as the Porte Super-Baby, was a large British, five-engined triplane flying-boat designed by John Cyril Porte at the Seaplane Experimental Station, Felixstowe, inspired by the Wanamaker Tri ...

– Contender for the transatlantic crossing

* List of firsts in aviation

This is a list of firsts in aviation. For a comprehensive list of women's records, see Women in aviation.

First person to fly

The first flight (including gliding) by a person is unknown. Several have been suggested.

* In 559 A.D., several pr ...

* R34 (airship) – First airship transatlantic crossing, also first east–west crossing

* Timeline of aviation

A timeline is a display of a list of events in chronological order. It is typically a graphic design showing a long bar labelled with dates paralleling it, and usually contemporaneous events.

Timelines can use any suitable scale representin ...

References

Further reading

*Lynch, Brendan (2009). ''Yesterday We Were in America — Alcock and Brown — First to fly the Atlantic non-stop'' (Haynes, ) *Bryson, Bill (2013) One Summer America 1927. Page 20. ISBN 9780552772563External links

Alcock and Brown at "Flights of Inspiration"

Alcock and Brown's plane at the London Science Museum

Brooklands Museum website

Colum McCann fiction short story based on Alcock and Brown's flight

a 1919 ''Flight'' article on the flight {{Aviation accidents and incidents in the United Kingdom Aviation history of the United Kingdom Aviation history of Canada Transatlantic flight Aviation accidents and incidents in Ireland History of St. John's, Newfoundland and Labrador 1919 in aviation 1919 in the United Kingdom 1919 in Canada