Tracy Philipps on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

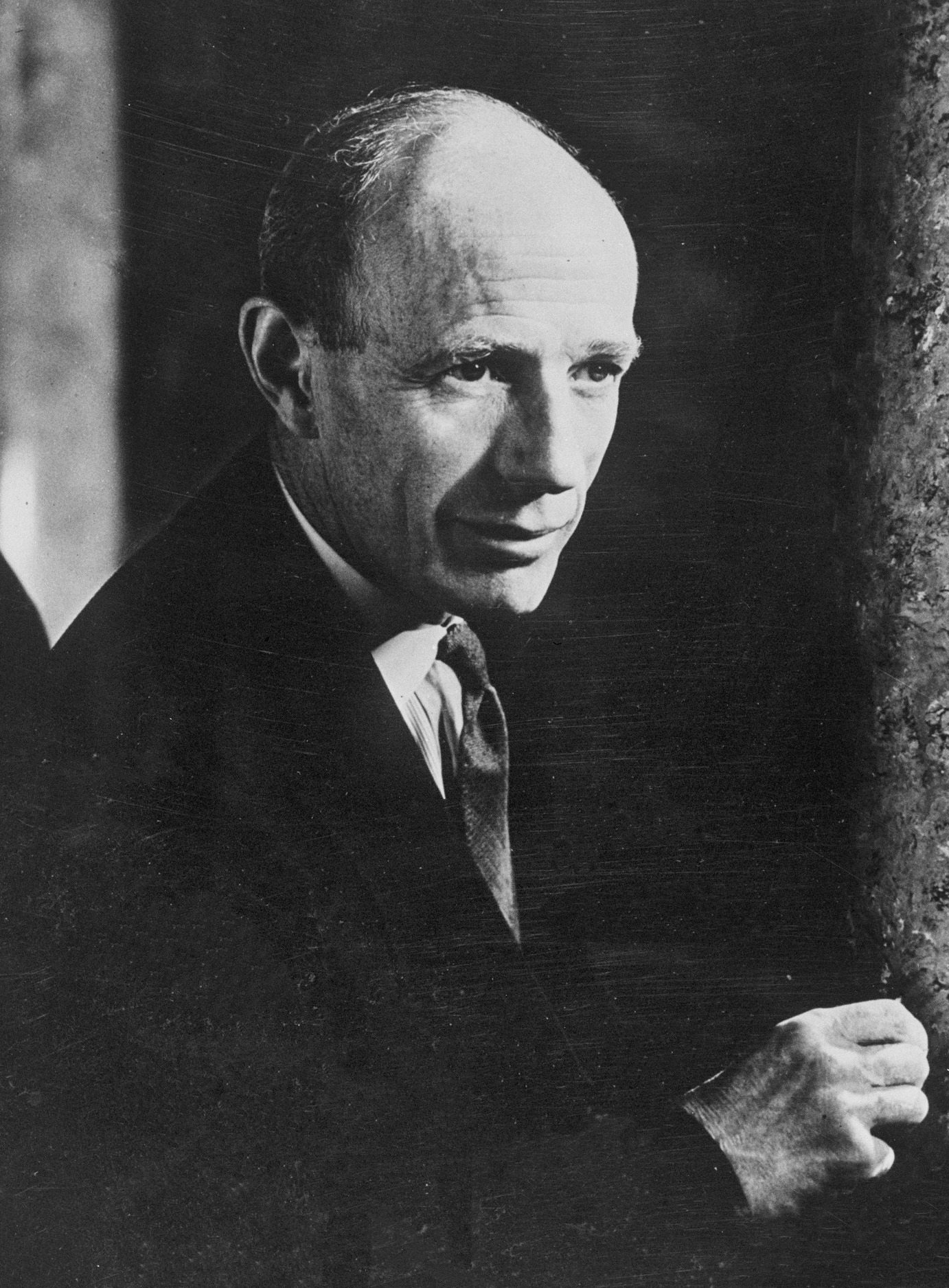

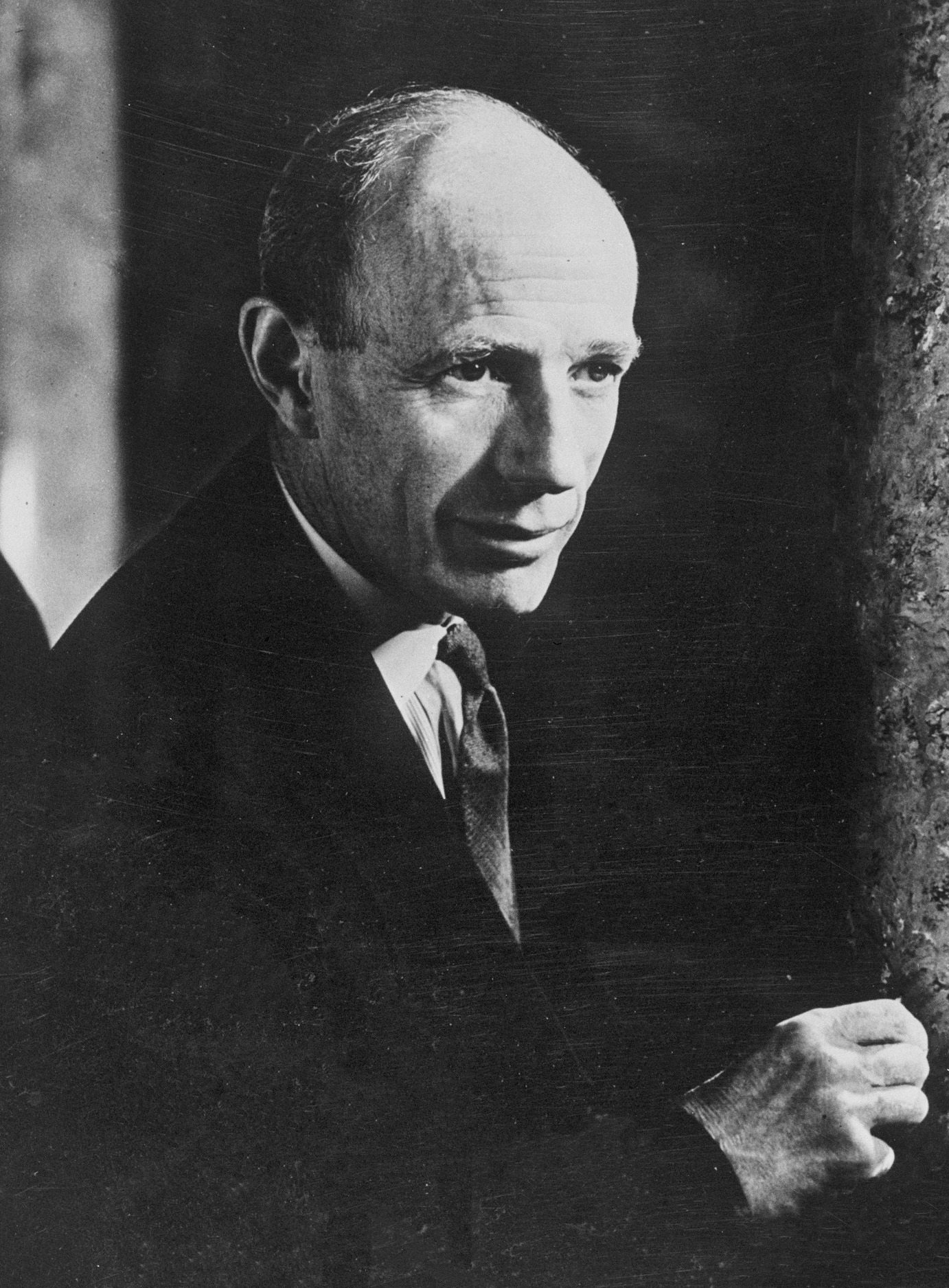

James Erasmus Tracy Philipps (20 November 1888 – 21 July 1959) was a British

Tracy Philipps was the only child of the Rev. John Erasmus Philipps, originally from

Tracy Philipps was the only child of the Rev. John Erasmus Philipps, originally from

After his time in the Officers' Training Corps at Durham, Philipps made his position in the

After his time in the Officers' Training Corps at Durham, Philipps made his position in the

Detouring into Abyssinia, Philipps stumbled upon a

Detouring into Abyssinia, Philipps stumbled upon a

During the 1930s Philipps became friendly with the Ukrainian Bureau, a lobbying centre formed in 1931 in London by Ukrainian-American Jacob Makohin to advocate for Ukrainian nationhood, promote the interests of Ukrainian minorities, and provide an outlet for information on Ukrainian issues that stood outside the Soviet sphere of influence. On several occasions in the 1930s he visited Ukraine and

During the 1930s Philipps became friendly with the Ukrainian Bureau, a lobbying centre formed in 1931 in London by Ukrainian-American Jacob Makohin to advocate for Ukrainian nationhood, promote the interests of Ukrainian minorities, and provide an outlet for information on Ukrainian issues that stood outside the Soviet sphere of influence. On several occasions in the 1930s he visited Ukraine and

In Atlanta he briefly interrupted his duties with the RCMP to attend W. E. B. Du Bois' First Phylon Conference at Fisk University. Asked by Du Bois to set out what effective decolonisation would look like, he suggested the British system of parliamentary democracy would be unsuitable for Africa due to the tribal loyalties of Africans. Following the conference, he reported to Gerald Campbell, his contact in the British Embassy to Washington, that his talk prompted "numerous questions"; these were generally hostile, which Philipps blamed on misrepresentation from communist sources.

On his return journey to Canada he briefly visited New York and met with Michael Huxley at the Inter-Allied Information Committee on the fifth floor of the Rockefeller Center.Kristmanson, 1999, pp. 194–195. Huxley was the director of this white propaganda outfit, launched in 1940 to win American support for Britain by casting British war aims in light of a new "internationalism" – intended to counteract American suspicions that Britain's true aim was to preserve its empire. Philipps was there to seek Huxley's views on a proposal of Count Vladislav Radziwill to have Poles trained in Canada for sabotage missions in occupied Poland. Huxley replied that he was "not competent to respond" and any suggestions from Philipps should be directed to Malcolm MacDonald, the List of High Commissioners of the United Kingdom to Canada, High Commissioner to Canada. Huxley regarded Philipps with caution, and the latter would leave unaware of British Security Co-ordination (BSC), a covert black propaganda outfit, operating from the very same building in support of British interests. Philipps may have been left "in the dark" by Huxley as he had already earned a reputation with British officials in Canada for straying beyond his remit by sending intelligence reports on matters that had nothing to do with the foreign-born labour force, which irritated his superior MacDonald. In any case, his "explicit valorization of the old British Empire" was not in keeping with the internationalist rhetoric British intelligence was keen to project.

In Atlanta he briefly interrupted his duties with the RCMP to attend W. E. B. Du Bois' First Phylon Conference at Fisk University. Asked by Du Bois to set out what effective decolonisation would look like, he suggested the British system of parliamentary democracy would be unsuitable for Africa due to the tribal loyalties of Africans. Following the conference, he reported to Gerald Campbell, his contact in the British Embassy to Washington, that his talk prompted "numerous questions"; these were generally hostile, which Philipps blamed on misrepresentation from communist sources.

On his return journey to Canada he briefly visited New York and met with Michael Huxley at the Inter-Allied Information Committee on the fifth floor of the Rockefeller Center.Kristmanson, 1999, pp. 194–195. Huxley was the director of this white propaganda outfit, launched in 1940 to win American support for Britain by casting British war aims in light of a new "internationalism" – intended to counteract American suspicions that Britain's true aim was to preserve its empire. Philipps was there to seek Huxley's views on a proposal of Count Vladislav Radziwill to have Poles trained in Canada for sabotage missions in occupied Poland. Huxley replied that he was "not competent to respond" and any suggestions from Philipps should be directed to Malcolm MacDonald, the List of High Commissioners of the United Kingdom to Canada, High Commissioner to Canada. Huxley regarded Philipps with caution, and the latter would leave unaware of British Security Co-ordination (BSC), a covert black propaganda outfit, operating from the very same building in support of British interests. Philipps may have been left "in the dark" by Huxley as he had already earned a reputation with British officials in Canada for straying beyond his remit by sending intelligence reports on matters that had nothing to do with the foreign-born labour force, which irritated his superior MacDonald. In any case, his "explicit valorization of the old British Empire" was not in keeping with the internationalist rhetoric British intelligence was keen to project.

In the aftermath of the Second World War Philipps joined the

In the aftermath of the Second World War Philipps joined the

PDF

* "The Natural Sciences in Africa: The Belgian National Parks." ''The Geographical Journal'', vol. 115, no. 1/3, 58–62 (1950)

Order of Leopold (Belgium), Knight of the Order of Leopold, 1922

Order of Leopold (Belgium), Knight of the Order of Leopold, 1922

Some correspondence of Tracy Philipps, with particular reference to W. E. B. Du Bois

{{DEFAULTSORT:Philipps, John Edward Tracy 1890 births 1959 deaths Burials in Oxfordshire Military personnel from Norfolk Alumni of Hatfield College, Durham Durham University Boat Club rowers People from Hillington, Norfolk People from East Hagbourne People educated at Abingdon School People educated at Marlborough College British war correspondents British Army personnel of World War I Rifle Brigade officers King's African Rifles officers Recipients of the Military Cross Fellows of the Royal Geographical Society Arab Bureau officers Intelligence Corps officers Arab Revolt Officers' Training Corps officers Alumni of the University of Oxford Secret Intelligence Service personnel Presidents of the Durham Union Information Research Department British intelligence operatives Writers about the Soviet Union

public servant

The civil service is a collective term for a sector of government composed mainly of career civil servants hired on professional merit rather than appointed or elected, whose institutional tenure typically survives transitions of political leaders ...

. Philipps was, in various guises, a soldier, colonial administrator, traveller, journalist, propagandist, conservationist, and secret agent

Espionage, spying, or intelligence gathering is the act of obtaining secret or confidential information (intelligence) from non-disclosed sources or divulging of the same without the permission of the holder of the information for a tangibl ...

. He served as a British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gur ...

intelligence officer in the East African and Middle Eastern theatre of the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fighti ...

, which led to brief stints in journalism and relief work in the aftermath of the Greco-Turkish War. Joining the Colonial Office, his reform-minded agenda as a District Commissioner in Colonial Uganda

The Protectorate of Uganda was a protectorate of the British Empire from 1894 to 1962. In 1893 the Imperial British East Africa Company transferred its administration rights of territory consisting mainly of the Kingdom of Buganda to the Brit ...

alienated superiors and soon resulted in the termination of his position.

He worked as a foreign correspondent for ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper ''The Sunday Times'' (fo ...

'' in Eastern Europe, and spent much of the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

in Canada attempting to build support among ethnic minorities for British war objectives. Following a frustrating experience helping to resettle displaced persons as a United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration

United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA) was an international relief agency, largely dominated by the United States but representing 44 nations. Founded in November 1943, it was dissolved in September 1948. it became part o ...

official, and Cold War propaganda activities with the secretive Information Research Department

The Information Research Department (IRD) was a secret Cold War propaganda department of the British Foreign Office, created to publish anti-communist propaganda, including black propaganda, provide support and information to anti-communist po ...

, Philipps' attention was increasingly taken up by his longstanding interest in conservation.

In the final years of his life he led efforts to create African National Parks as Secretary-General of the International Union for Conservation of Nature

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN; officially International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources) is an international organization working in the field of nature conservation and sustainable use of nat ...

. The product of an old, upper-class family, Philipps possessed determination and high self-esteem as well as a great deal of ambition – though his personal eccentricity sometimes undermined his goals.

Early life

Tracy Philipps was the only child of the Rev. John Erasmus Philipps, originally from

Tracy Philipps was the only child of the Rev. John Erasmus Philipps, originally from Haverfordwest

Haverfordwest (, ; cy, Hwlffordd ) is the county town of Pembrokeshire, Wales, and the most populous urban area in Pembrokeshire with a population of 14,596 in 2011. It is also a community, being the second most populous community in the count ...

in Pembrokeshire

Pembrokeshire ( ; cy, Sir Benfro ) is a county in the south-west of Wales. It is bordered by Carmarthenshire to the east, Ceredigion to the northeast, and the rest by sea. The county is home to Pembrokeshire Coast National Park. The Park o ...

, and Margaret Louisa Everard (née ffolkes). The elder Philipps had been vicar of Wiston in Pembrokeshire, and later held curacies in Enstone

Enstone is a village and civil parish in England, about east of Chipping Norton and north-west of Oxford city. The civil parish, one of Oxfordshire's largest, consists of the villages of Church Enstone and Neat Enstone, with the hamlets of Cha ...

in Oxfordshire

Oxfordshire is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in the north west of South East England. It is a mainly rural county, with its largest settlement being the city of Oxford. The county is a centre of research and development, primarily ...

and Staindrop

Staindrop is a village and civil parish in County Durham, England. It is situated approximately north east of Barnard Castle, on the A688 road. According to the 2011 UK Census the population was 1,310, this includes the hamlets of Cleatlam an ...

in County Durham, where he was domestic chaplain to the 9th Baron Barnard. After his death in 1923 his widow Margaret married Harold Dillon, 17th Viscount Dillon

Harold Arthur Lee-Dillon, 17th Viscount Dillon CH FBA (24 January 1844–18 December 1932) was an English antiquary and a leading authority on the history of arms and armour and medieval costume.

Life

The eldest son of Arthur Dillon, 16th ...

. Tracy was born in Hillington, Norfolk

Hillington is a village and civil parish in the English county of Norfolk. It covers an area of and had a population of 287 in 123 households as of the United Kingdom Census 2001, 2001 census, increasing to 400 at the 2011 Census.

For the purpos ...

, the traditional home of his wife's family.

The younger Philipps enrolled at Abingdon School

Abingdon School is a day and boarding independent school for boys in Abingdon-on-Thames, Oxfordshire, England. The twentieth oldest independent British school, it celebrated its 750th anniversary in 2006. The school was described as "highly ...

in May 1899. From September 1904 he boarded at Marlborough College

Marlborough College is a Public school (United Kingdom), public school (English Independent school (United Kingdom), independent boarding school) for pupils aged 13 to 18 in Marlborough, Wiltshire, England. Founded in 1843 for the sons of Church ...

, and left in December 1906. At Marlborough he played as a forward in inter-house rugby

Rugby may refer to:

Sport

* Rugby football in many forms:

** Rugby league: 13 players per side

*** Masters Rugby League

*** Mod league

*** Rugby league nines

*** Rugby league sevens

*** Touch (sport)

*** Wheelchair rugby league

** Rugby union: 1 ...

matches. In February 1907 he was one of a few dozen Old Marlburians accepted for membership of the Marlburian Club alumni association after a meeting of the club committee held in Old Queen Street

Queen Anne’s Gate is a street in Westminster, London. Many of the buildings are Grade I listed, known for their Queen Anne architecture. Simon Bradley and Nikolaus Pevsner described the Gate’s early 18th century houses as “the best of the ...

, Westminster

Westminster is an area of Central London, part of the wider City of Westminster.

The area, which extends from the River Thames to Oxford Street, has many visitor attractions and historic landmarks, including the Palace of Westminster, Bucki ...

.

According to the Christmas 1907 edition of ''The Abingdonian'' magazine Philipps was still undecided about which university he would attend but was nonetheless 'endeavouring to obtain a scholarship at Jesus, Cambridge' – an effort that was ultimately unsuccessful. For university he is said to have eventually studied at Oxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

for a period of time, although sources on this are unclear. What is known for certain is that he entered Durham University

, mottoeng = Her foundations are upon the holy hills (Psalm 87:1)

, established = (university status)

, type = Public

, academic_staff = 1,830 (2020)

, administrative_staff = 2,640 (2018/19)

, chancellor = Sir Thomas Allen

, vice_chan ...

in 1910. Like his father and uncle, he was a member of Hatfield Hall and graduated in 1912 with a Bachelor of Arts degree in Classics

Classics or classical studies is the study of classical antiquity. In the Western world, classics traditionally refers to the study of Classical Greek and Roman literature and their related original languages, Ancient Greek and Latin. Classi ...

. He was Secretary of Durham University Boat Club

Durham University Boat Club (DUBC) is the rowing club of Durham University. In recent years, DUBC has cemented itself as one of the strongest university boat clubs in Great Britain. Under the leader ...

in 1911. He also served as President of the Durham Union for Epiphany term

Epiphany term is the second academic term at Durham University, falling between Michaelmas term and Easter term, as in the Christian Feast of the Epiphany, held in January.

The term runs from January until March, equivalent to the Spring term at m ...

of 1912, and was Editor of ''The Sphinx'' – a student magazine with a lighthearted tone – in addition to participating in the Officers' Training Corps

The Officers' Training Corps (OTC), more fully called the University Officers' Training Corps (UOTC), are military leadership training units operated by the British Army. Their focus is to develop the leadership abilities of their members whilst ...

.

As the President of the Union during the seventieth anniversary of its foundation, he chaired an inter-varsity debate held on Saturday 16 March 1912 at the Great Hall of University College

In a number of countries, a university college is a college institution that provides tertiary education but does not have full or independent university status. A university college is often part of a larger university. The precise usage varies ...

, which featured teams from Oxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

, Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a university city and the county town in Cambridgeshire, England. It is located on the River Cam approximately north of London. As of the 2021 United Kingdom census, the population of Cambridge was 145,700. Cambridge becam ...

, Trinity College, Dublin

, name_Latin = Collegium Sanctae et Individuae Trinitatis Reginae Elizabethae juxta Dublin

, motto = ''Perpetuis futuris temporibus duraturam'' (Latin)

, motto_lang = la

, motto_English = It will last i ...

, and Edinburgh University

The University of Edinburgh ( sco, University o Edinburgh, gd, Oilthigh Dhùn Èideann; abbreviated as ''Edin.'' in post-nominals) is a public research university based in Edinburgh, Scotland. Granted a royal charter by King James VI in 158 ...

.

Early career

First World War

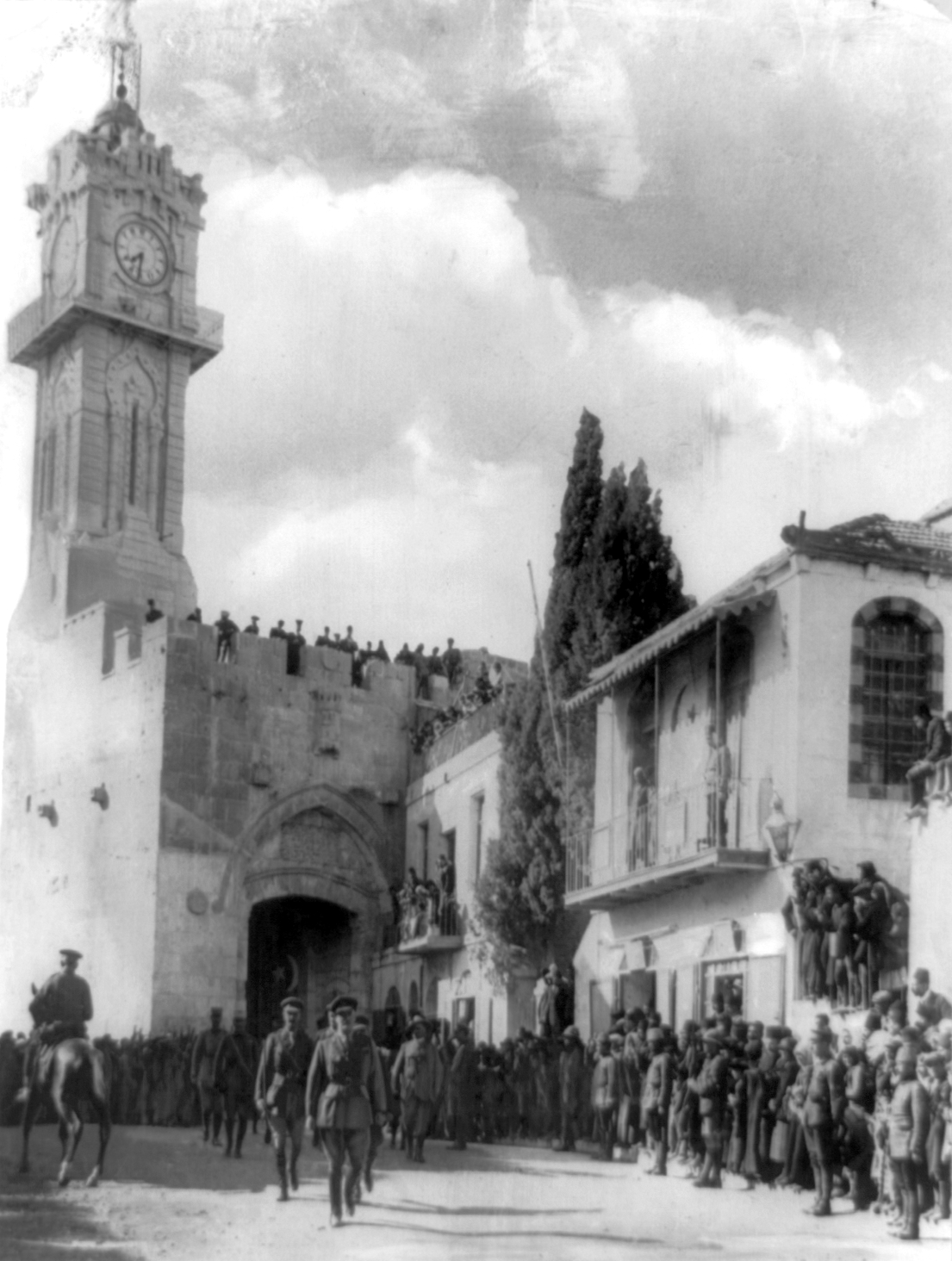

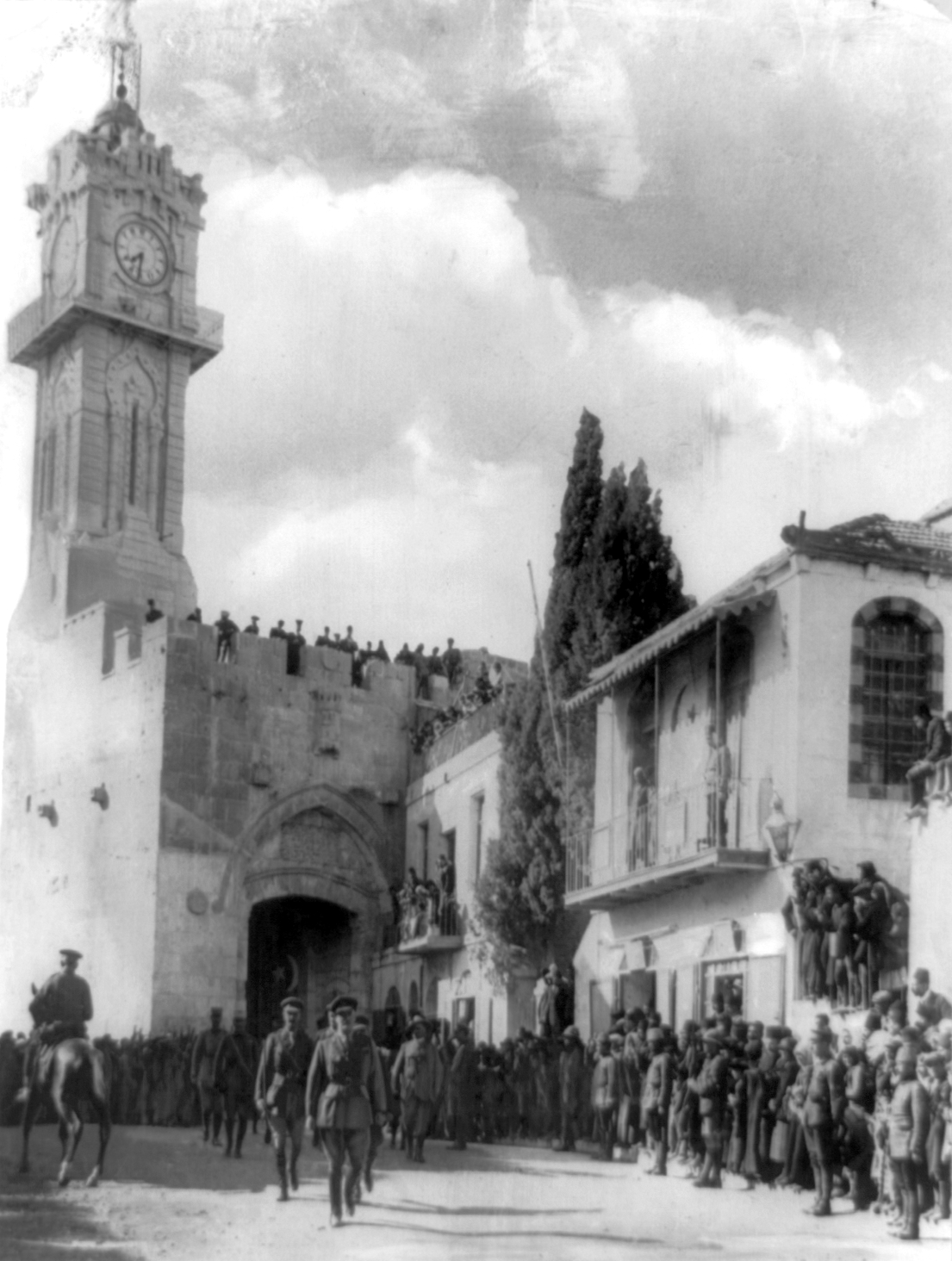

After his time in the Officers' Training Corps at Durham, Philipps made his position in the

After his time in the Officers' Training Corps at Durham, Philipps made his position in the British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gur ...

official. He was gazetted

A gazette is an official journal, a newspaper of record, or simply a newspaper.

In English and French speaking countries, newspaper publishers have applied the name ''Gazette'' since the 17th century; today, numerous weekly and daily newspapers ...

as a 2nd Lieutenant in the Infantry in February 1913. He joined the Rifle Brigade

The Rifle Brigade (The Prince Consort's Own) was an infantry rifle regiment of the British Army formed in January 1800 as the "Experimental Corps of Riflemen" to provide sharpshooters, scouts, and skirmishers. They were soon renamed the "Rifle ...

but was soon sent to East Africa on secondment in an intelligence role. When the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fighti ...

broke out he was on attachment to the Kings African Rifles (KAR) and was "one of the first Englishmen in action" when the war in Africa started in August 1914. Serving temporarily with the Indian Expeditionary Force B

The Indian Army during World War I was involved World War I. Over one million Indian troops served overseas, of whom 62,000 died and another 67,000 were wounded. In total at least 74,187 Indian soldiers died during the war.

In World War I the ...

as an Assistant Intelligence Officer alongside Richard Meinertzhagen

Colonel Richard Meinertzhagen, CBE, DSO (3 March 1878 – 17 June 1967) was a British soldier, intelligence officer, and ornithologist. He had a decorated military career spanning Africa and the Middle East. He was credited with creating and ...

, he was involved in the disastrous Battle of Tanga

The Battle of Tanga, sometimes also known as the Battle of the Bees, was the unsuccessful attack by the British Indian Expeditionary Force "B" under Major General A. E. Aitken to capture German East Africa (the mainland portion of present-day ...

. He was later wounded while serving with the KAR (for which he was mentioned in despatches

To be mentioned in dispatches (or despatches, MiD) describes a member of the armed forces whose name appears in an official report written by a superior officer and sent to the high command, in which their gallant or meritorious action in the face ...

) and also present as a political officer at the Battle of Bukoba (serving as part of the hastily formed Uganda Intelligence Department) in June 1915. The next year Philipps was awarded a promotion to captain, effective from 17 January 1916. With the newly formed Lake Force

Lake Force (or Lakeforce) was a unit of the British Army stationed in the Uganda Protectorate on the west coast of Lake Victoria under the command of Brigadier-General Sir Charles Crewe in 1916, during the East African campaign of the First World ...

he took part in the Tabora Offensive (April – September 1916) and in the aftermath was awarded the Military Cross

The Military Cross (MC) is the third-level (second-level pre-1993) military decoration awarded to officers and (since 1993) other ranks of the British Armed Forces, and formerly awarded to officers of other Commonwealth countries.

The MC i ...

, gazetted February 1917, which he received for actions in conjunction with an intelligence section of the Belgian Force Publique

The ''Force Publique'' (, "Public Force"; nl, Openbare Weermacht) was a gendarmerie and military force in what is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo from 1885 (when the territory was known as the Congo Free State), through the period of Be ...

. From November 1916 to March 1917, Philipps, by now the chief political officer for the Uganda region, was based in Ruanda-Urundi

Ruanda-Urundi (), later Rwanda-Burundi, was a colonial territory, once part of German East Africa, which was occupied by troops from the Belgian Congo during the East African campaign in World War I and was administered by Belgium under milit ...

, a part of German East Africa

German East Africa (GEA; german: Deutsch-Ostafrika) was a German colony in the African Great Lakes region, which included present-day Burundi, Rwanda, the Tanzania mainland, and the Kionga Triangle, a small region later incorporated into Mozamb ...

recently captured by the Belgians.

A September 1917 entry in ''The London Gazette

''The London Gazette'' is one of the official journals of record or government gazettes of the Government of the United Kingdom, and the most important among such official journals in the United Kingdom, in which certain statutory notices ar ...

'' noted that Philipps relinquished his Army commission earlier in the year, with no explanation provided. This decision was due to injury: his entry in the 1951 ''Who's Who'' describes being 'invalided', indicating wounds had rendered him unfit for further duty, and is further confirmed by a letter sent by Philipps to Reginald Wingate

General Sir Francis Reginald Wingate, 1st Baronet, (25 June 1861 – 29 January 1953) was a British general and administrator in Egypt and the Sudan. He earned the ''nom de guerre'' Wingate of the Sudan.

Early life

Wingate was born at Port Gla ...

which suggests he had returned to Britain in March. Philipps quickly recovered and restored his commission: he was employed at the War Office in London with the Intelligence Staff, June–August 1917; then was similarly employed at the Admiralty, August–October 1917. By November 1917 he was in Abyssinia

The Ethiopian Empire (), also formerly known by the exonym Abyssinia, or just simply known as Ethiopia (; Amharic and Tigrinya: ኢትዮጵያ , , Oromo: Itoophiyaa, Somali: Itoobiya, Afar: ''Itiyoophiyaa''), was an empire that historica ...

on a mission to investigate the extent of the slave trade. The next month he was reportedly present at the Capture of Jerusalem. In 1918 he began a posting at the Arab Bureau

The Arab Bureau was a section of the Cairo Intelligence Department established in 1916 during the First World War, and closed in 1920, whose purpose was the collection and dissemination of propaganda and intelligence about the Arab regions of ...

(a section of the Cairo Intelligence Department), operating as an Intelligence Officer at their headquarters in Cairo

Cairo ( ; ar, القاهرة, al-Qāhirah, ) is the capital of Egypt and its largest city, home to 10 million people. It is also part of the largest urban agglomeration in Africa, the Arab world and the Middle East: The Greater Cairo metro ...

. This was a role generally based in Cairo, with spells in Palestine

__NOTOC__

Palestine may refer to:

* State of Palestine, a state in Western Asia

* Palestine (region), a geographic region in Western Asia

* Palestinian territories, territories occupied by Israel since 1967, namely the West Bank (including East J ...

and Syria

Syria ( ar, سُورِيَا or سُورِيَة, translit=Sūriyā), officially the Syrian Arab Republic ( ar, الجمهورية العربية السورية, al-Jumhūrīyah al-ʻArabīyah as-Sūrīyah), is a Western Asian country loc ...

, working alongside Lawrence of Arabia

Thomas Edward Lawrence (16 August 1888 – 19 May 1935) was a British archaeologist, army officer, diplomat, and writer who became renowned for his role in the Arab Revolt (1916–1918) and the Sinai and Palestine Campaign (1915–1918 ...

in the final campaigns of the Arab Revolt

The Arab Revolt ( ar, الثورة العربية, ) or the Great Arab Revolt ( ar, الثورة العربية الكبرى, ) was a military uprising of Arab forces against the Ottoman Empire in the Middle Eastern theatre of World War I. On t ...

. His work with the Bureau was interrupted by his taking part in a military expedition against the Turkana people

The Turkana are a Nilotic people native to the Turkana County in northwest Kenya, a semi-arid climate region bordering Lake Turkana in the east, Pokot, Rendille and Samburu people to the south, Uganda to the west, and South Sudan and Ethiopia t ...

(April–June 1918), who lived on the fringes of British East Africa and were notorious for raiding cattle.

At some time either shortly before or shortly after the conclusion of the war, he left the Bureau to serve on attachment to the British Embassy in Rome. He also spent time with the British Legation in Athens. Years later, in February 1922, ''The London Gazette'' reported that Philipps, by now a captain in the Special List, was one of a number of British officers from the war who had been awarded the Belgian Order of Leopold.

Aftermath

Philipps returned to Africa and served as Acting District Commissioner inKigezi District

Kigezi District once covered what are now Kabale District, Kanungu District, Kisoro District and Rukungiri District, in southwest Uganda. Its terraced fields are what gives this part of Uganda its distinctive character. Kigezi was popularly known ...

in Uganda from 1919 through 1920. One of his challenges was the threat posed by the Nyabinghi cult, popular with the Kiga people

Kiga people, or ''Abakiga'' ("people of the mountains"), are a Bantu ethnic group native to south western Uganda and northern Rwanda.

History Pre-colonial period

The Kiga people are believed to have originated in Rwanda as mentioned in one o ...

of Southern Uganda, and highly resistant to British rule. After cult leader Ntokibiri was killed by a posse, Philipps ordered that the head of Ntokibiri be sent to Entebbe

Entebbe is a city in Central Uganda. Located on a Lake Victoria peninsula, approximately southwest of the Ugandan capital city, Kampala. Entebbe was once the seat of government for the Protectorate of Uganda prior to independence, in 1962. The ...

as proof that the threat had been eliminated. Philipps worked to end the use of Baganda

The Ganda people, or Baganda (endonym: ''Baganda''; singular ''Muganda''), are a Bantu ethnic group native to Buganda, a subnational kingdom within Uganda. Traditionally composed of 52 clans (although since a 1993 survey, only 46 are official ...

agents in areas populated by the Kiga and discouraged the use of the Luganda

The Ganda language or Luganda (, , ) is a Bantu language spoken in the African Great Lakes region. It is one of the major languages in Uganda and is spoken by more than 10 million Baganda and other people principally in central Uganda including ...

language in courts, instead introducing the Swahili language

Swahili, also known by its local name , is the native language of the Swahili people, who are found primarily in Tanzania, Kenya and Mozambique (along the East African coast and adjacent litoral islands). It is a Bantu language, though Swahili ...

, which the Baganda people could not speak. In February 1920 Philipps briefly returned to Durham Durham most commonly refers to:

*Durham, England, a cathedral city and the county town of County Durham

* County Durham, an English county

*Durham County, North Carolina, a county in North Carolina, United States

*Durham, North Carolina, a city in N ...

where he gave a public lecture on 'The Pygmies

In anthropology, pygmy peoples are ethnic groups whose average height is unusually short. The term pygmyism is used to describe the phenotype of endemic short stature (as opposed to disproportionate dwarfism occurring in isolated cases in a pop ...

of East Central Africa', illustrated with slides, at Durham Town Hall.

The following year he travelled on foot across Equatorial Africa

Equatorial Africa is an ambiguous term that sometimes is used to refer either to the equatorial region of Sub-Saharan Africa traversed by the Equator, more broadly to tropical Africa or in a biological and geo-environmental sense to the intra-tr ...

, taking a circuitous route from east to west. On the way he discovered ''Lutra Paraonyx Philippsi'', a subspecies of the African clawless otter

The African clawless otter (''Aonyx capensis''), also known as the Cape clawless otter or groot otter, is the second-largest freshwater otter species. It inhabits permanent water bodies in savannah and lowland forest areas through most of sub-Sa ...

that he recorded for science and named after himself. For one month he was joined by Prince Wilhelm of Sweden, whom Philipps helped to obtain photographs of pygmies

In anthropology, pygmy peoples are ethnic groups whose average height is unusually short. The term pygmyism is used to describe the phenotype of endemic short stature (as opposed to disproportionate dwarfism occurring in isolated cases in a pop ...

and specimens of gorilla for the Swedish Museum of Natural History

The Swedish Museum of Natural History ( sv, Naturhistoriska riksmuseet, literally, the National Museum of Natural History), in Stockholm, is one of two major museums of natural history in Sweden, the other one being located in Gothenburg.

The ...

. As reported in ''The Morning Bulletin

''The Morning Bulletin'' is an online newspaper servicing the city of Rockhampton and the surrounding areas of Central Queensland, Australia.

From 1861 to 2020, ''The Morning Bulletin'' was published as a print edition, before then becoming an ...

'', Philipps had a caravan party of approximately 50 men for the seven-month journey, including two tribal chiefs lent to him by colonial authorities, Philippo Lwengoga and Benedikto Daki, who proved to be crucial in the success of the journey.

Detouring into Abyssinia, Philipps stumbled upon a

Detouring into Abyssinia, Philipps stumbled upon a slave market

A slave market is a place where slaves are bought and sold. These markets became a key phenomenon in the history of slavery.

Slave markets in the Ottoman Empire

In the Ottoman Empire during the mid-14th century, slaves were traded in specia ...

, where he saw a 'half-caste

Half-caste (an offensive term for the offspring of parents of different racial groups or cultures) is a term used for individuals of multiracial descent. It is derived from the term ''caste'', which comes from the Latin ''castus'', meaning pu ...

auctioneer' selling young girls to the highest bidder. He was able to buy off the girl in the worst condition, who had been nearly beaten to death, and had her sent to a Christian mission. In Addis Ababa

Addis Ababa (; am, አዲስ አበባ, , new flower ; also known as , lit. "natural spring" in Oromo), is the capital and largest city of Ethiopia. It is also served as major administrative center of the Oromia Region. In the 2007 census, t ...

he encountered the Empress Zewditu, describing her as 'short and handsome, with a mass of barbaric robes encrusted with gold and jewels' and having 'black, rather curly hair' In the aftermath of the journey, Philipps took Lwengoga and Daki with him to London, where the trio visited the Zoological Society Gardens. The two Africans were reportedly astonished to see a zookeeper approach and feed an African Elephant without any fear.

Philipps was assigned by Lord Halifax

Edward Frederick Lindley Wood, 1st Earl of Halifax, (16 April 1881 – 23 December 1959), known as The Lord Irwin from 1925 until 1934 and The Viscount Halifax from 1934 until 1944, was a senior British Conservative politician of the 19 ...

– who had recently been appointed Under-Secretary for the Colonies – to report on the activities of the 2nd Pan-African Congress, which was hosting several meetings in London, Brussels and Paris during August and September. During this mission he would meet W. E. B. DuBois, the organiser of the Congress and an American sociologist and Pan-Africanism

Pan-Africanism is a worldwide movement that aims to encourage and strengthen bonds of solidarity between all Indigenous and diaspora peoples of African ancestry. Based on a common goal dating back to the Atlantic slave trade, the movement exte ...

advocate. Following the Paris conference, Philipps contacted Du Bois to seek a lunch meeting in London, specifically at ''The Holborn Restaurant'', 129 Kingsway. Du Bois was unable to attend because he left Europe at the start of the month, but requested copies of any future articles that Philipps published, thus establishing a long-term correspondence between the two.

With the Famine in Russia intensifying, Philipps travelled to Constantinople, then Moscow

Moscow ( , US chiefly ; rus, links=no, Москва, r=Moskva, p=mɐskˈva, a=Москва.ogg) is the capital and largest city of Russia. The city stands on the Moskva River in Central Russia, with a population estimated at 13.0 million ...

, as part of the International Committee for Russian Relief (ICRR) led by explorer Fridtjof Nansen

Fridtjof Wedel-Jarlsberg Nansen (; 10 October 186113 May 1930) was a Norwegian polymath and Nobel Peace Prize laureate. He gained prominence at various points in his life as an explorer, scientist, diplomat, and humanitarian. He led the team t ...

. He then took a brief detour into journalism when he reported on the Greco-Turkish War for ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper ''The Sunday Times'' (fo ...

'' newspaper. He may have decided to follow Nansen to Ottoman Turkey

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

, who was in the country to negotiate the resettlement of Greek refugees. While stationed in Turkey he assumed the role of supply commissioner for the famine relief operation organised by the British Red Cross

The British Red Cross Society is the United Kingdom body of the worldwide neutral and impartial humanitarian network the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement. The society was formed in 1870, and is a registered charity with more ...

under the auspices of the League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference that ...

and Nansen's International Committee for Russian Relief (ICRR). This allowed him to travel through the Ukrainian and Russian countryside and become familiar with the people and their traditions, but also developed a permanent resentment of the Soviet system. He later reported seeing the remains of victims of human cannibalism

Human cannibalism is the act or practice of humans eating the flesh or internal organs of other human beings. A person who practices cannibalism is called a cannibal. The meaning of "cannibalism" has been extended into zoology to describe an ind ...

.

Colonial Service

1923–1930

From 1923 to 1925 Philipps was inKhartoum

Khartoum or Khartum ( ; ar, الخرطوم, Al-Khurṭūm, din, Kaartuɔ̈m) is the capital of Sudan. With a population of 5,274,321, its metropolitan area is the largest in Sudan. It is located at the confluence of the White Nile, flowing no ...

, occupying a position within the Sudan Political Service

Anglo-Egyptian Sudan ( ar, السودان الإنجليزي المصري ') was a condominium of the United Kingdom and Egypt in the Sudans region of northern Africa between 1899 and 1956, corresponding mostly to the territory of present-day ...

. In a letter written from Khartoum in November 1923 to the Labour Party politician Ben Spoor

Benjamin Charles Spoor (2 June 1878 – 22 December 1928) was a British Labour Party politician. He took a particular interest in India.

Born in Witton Park, County Durham, he went to Elmfield College, York, and came from a family of Primit ...

, Philipps related he was on a posting with the Colonial Office, arranged 'through the War Office

The War Office was a department of the British Government responsible for the administration of the British Army between 1857 and 1964, when its functions were transferred to the new Ministry of Defence (MoD). This article contains text from t ...

', for a two-year period. Historian Bohdan S. Kordan described this job as being 'deputy director of intelligence' for Anglo-Egyptian Sudan

Anglo-Egyptian Sudan ( ar, السودان الإنجليزي المصري ') was a condominium of the United Kingdom and Egypt in the Sudans region of northern Africa between 1899 and 1956, corresponding mostly to the territory of present-day ...

.

In the same letter to Spoor, Philipps reports a journey to Europe that may also be connected to intelligence gathering. He describes being on leave in the Balkans during the Summer of 1923: in Croatia, he stayed with Stjepan Radić

Stjepan Radić (11 June 1871 – 8 August 1928) was a Croat politician and founder of the Croatian People's Peasant Party (HPSS), active in Austria-Hungary and the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes.

He is credited with galvanizing Cro ...

, the leader of the Croatian People's Peasant Party

The Croatian Peasant Party ( hr, Hrvatska seljačka stranka, HSS) is an agrarian political party in Croatia founded on 22 December 1904 by Antun and Stjepan Radić as Croatian Peoples' Peasant Party (HPSS). The Brothers Radić believed that t ...

, shortly before the latter left on an overseas trip. He moved to Bulgaria and met the Prime Minister Aleksandar Stamboliyski

Aleksandar Stoimenov Stamboliyski ( bg, Александър Стоименов Стамболийски; 1 March 1879 – 14 June 1923) was the prime minister of Bulgaria from 1919 until 1923.

Stamboliyski was a member of the Agrarian Union, ...

'about ten days' before Stamboliyski was assassinated on 14 June.

Following his experience in Sudan he pursued a full-time career in the Colonial Service in East Africa, where as a 'self-appointed scourge of the wicked' according to John Tosh

John A. Tosh is a British historian and Professor Emeritus of History at Roehampton University. He gained his BA at the University of Oxford and his MA at the University of Cambridge. He was awarded his PhD by the University of London in 1973; hi ...

, he exposed abuses and advocated for reform. He spent much of this period back in the Kigezi District of Uganda, where he was known for his energy as an administrator – attempting to develop native industries in iron smelting and using the sisal

Sisal (, ) (''Agave sisalana'') is a species of flowering plant native to southern Mexico, but widely cultivated and naturalized in many other countries. It yields a stiff fibre used in making rope and various other products. The term sisal may ...

plant to make rope – and paying for many supplies out of his own pocket.

During his time in Africa he was fond of exploring the tropical forests and writing his observations on the wildlife he encountered. In 1930, he met Julian Huxley

Sir Julian Sorell Huxley (22 June 1887 – 14 February 1975) was an English evolutionary biologist, eugenicist, and internationalist. He was a proponent of natural selection, and a leading figure in the mid-twentieth century modern synthesis. ...

in the forests of Western Uganda whilst accompanying entomologists

Entomology () is the scientific study of insects, a branch of zoology. In the past the term "insect" was less specific, and historically the definition of entomology would also include the study of animals in other arthropod groups, such as arach ...

on a scientific mission.Caccia, 2010, p. 77 His experiences led him to become an early advocate of the creation of large national park

A national park is a natural park in use for conservation purposes, created and protected by national governments. Often it is a reserve of natural, semi-natural, or developed land that a sovereign state declares or owns. Although individual ...

s in Equatorial Africa

Equatorial Africa is an ambiguous term that sometimes is used to refer either to the equatorial region of Sub-Saharan Africa traversed by the Equator, more broadly to tropical Africa or in a biological and geo-environmental sense to the intra-tr ...

, believing that human encroachment on gorilla habitats engendered aggressive behaviour.

1931–1935

Philipps' career in the Colonial Service began to be interrupted by health problems. He had already spent part of 1931 back in England recuperating atDitchley

Ditchley Park is a country house near Charlbury in Oxfordshire, England. The estate was once the site of a Roman villa. Later it became a royal hunting ground, and then the property of Sir Henry Lee of Ditchley. The 2nd Earl of Lichfield buil ...

(the home of his father-in-law the Viscount Dillon) after a 'terrible ordeal' in Africa made worse through incompetent care provided by missionaries. By January 1932, having again fallen unwell the previous year, he was on leave for health reasons at the clinic of Auguste Rollier in Leysin, Switzerland. He noted in a letter to an American friend, Charles Francis de Ganahl, that his temperature had gone down and he had gained in weight, having 'dropped from 13 to 7 stone', or , the previous month. Since he was no longer in an assigned position in Africa, he considered seeking a transfer to somewhere in the Near East. Writing to de Ganahl from Clarens in April 1932, Philipps described being allowed to temporarily 'descend from Léysin's icy mountains into the cities of the plain' but could still only 'hobble about rather painfully' – nevertheless he mentioned plans to visit Corfu

Corfu (, ) or Kerkyra ( el, Κέρκυρα, Kérkyra, , ; ; la, Corcyra.) is a Greek islands, Greek island in the Ionian Sea, of the Ionian Islands, and, including its small satellite islands, forms the margin of the northwestern frontier of G ...

and Ithaca

Ithaca most commonly refers to:

*Homer's Ithaca, an island featured in Homer's ''Odyssey''

*Ithaca (island), an island in Greece, possibly Homer's Ithaca

*Ithaca, New York, a city, and home of Cornell University and Ithaca College

Ithaca, Ithaka ...

, having booked passage on a cargo ship leaving Venice

Venice ( ; it, Venezia ; vec, Venesia or ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto region. It is built on a group of 118 small islands that are separated by canals and linked by over 400 bridges. The isla ...

on 1 May.

Despite thoughts about going elsewhere, Philipps returned to Africa. His last assignment was as District Commissioner of the Lango District in Uganda. Philips was removed from duty after disagreeing with the governor on colonial administration:: he argued that the policy of 'indirect rule' ( devolution of responsibility to native chiefs) brought out rampant corruption among the chiefs in power at the expense of the ordinary native population. Towards the end of 1933 he had submitted several highly critical reports concerning the quality of native administration, having chosen to bypass native courts during his inquiries and encouraged the local peasantry to submit their grievances to himself.

He was replaced as District Commissioner in March 1934 and, under protest, forcibly retired from the Colonial Office the following year. Tosh noted that although his superiors agreed with many of his findings, because Philipps was by now associated with an 'anti-chief' mindset, the colonial authorities thought carrying out reform would be harder if Philipps was still in place. The verdict of Bernard Bourdillon, then Governor of Uganda, was that Philipps was a "brilliant man" who "did not exactly fit into Colonial administration".

Diplomatic Correspondent, 1936–1939

In 1936 Philipps began working as a foreign correspondent inEastern Europe

Eastern Europe is a subregion of the European continent. As a largely ambiguous term, it has a wide range of geopolitical, geographical, ethnic, cultural, and socio-economic connotations. The vast majority of the region is covered by Russia, whic ...

and Turkey. He is known to have spent at least part of 1936 in Berlin, where he wrote a letter to the historian Arnold J. Toynbee concerning the local response to Toynbee's controversial private interview with Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Germany from 1933 until his death in 1945. He rose to power as the leader of the Nazi Party, becoming the chancellor in 1933 and then ...

, noting that it was "an eager topic of discussion everywhere".

That decade he also married the pianist Lubka Kolessa. A July 1939 notice in ''The Times'' reported that the pair had married in Prague

Prague ( ; cs, Praha ; german: Prag, ; la, Praga) is the capital and largest city in the Czech Republic, and the historical capital of Bohemia. On the Vltava river, Prague is home to about 1.3 million people. The city has a tempera ...

on 14 March, the eve of the German occupation of the country. Kolessa gave birth to a son, Igor (John), in Marylebone, London

Marylebone (usually , also , ) is a district in the West End of London, in the City of Westminster. Oxford Street, Europe's busiest shopping street, forms its southern boundary.

An ancient parish and latterly a metropolitan borough, it merge ...

that same year.

In 1938 Philipps travelled to South America with Kolessa, where he acted as manager for his wife's concert tour. The tour traveled to Brazil, Argentina

Argentina (), officially the Argentine Republic ( es, link=no, República Argentina), is a country in the southern half of South America. Argentina covers an area of , making it the second-largest country in South America after Brazil, th ...

, Chile

Chile, officially the Republic of Chile, is a country in the western part of South America. It is the southernmost country in the world, and the closest to Antarctica, occupying a long and narrow strip of land between the Andes to the east a ...

, and Uruguay

Uruguay (; ), officially the Oriental Republic of Uruguay ( es, República Oriental del Uruguay), is a country in South America. It shares borders with Argentina to its west and southwest and Brazil to its north and northeast; while bordering ...

and conducted 178 live performances. While in South America, he investigated the colonies developed by the Jewish Colonization Association

The Jewish Colonisation Association (JCA or ICA, Yiddish ייִק"אַ), in America spelled Jewish Colonization Association, is an organisation created on September 11, 1891, by Baron Maurice de Hirsch. Its aim was to facilitate the mass emigrati ...

to discover if they would be viable places to resettle the increasingly vulnerable Jewish population of Europe. In a 1939 letter to ''The Times'' he objected to the argument made by Chaim Weizmann

Chaim Azriel Weizmann ( he, חיים עזריאל ויצמן ', russian: Хаим Евзорович Вейцман, ''Khaim Evzorovich Veytsman''; 27 November 1874 – 9 November 1952) was a Russian-born biochemist, Zionist leader and Israe ...

that the " Hirsch Jewish land settlements" were unsuitable places for the "unwanted Jewish Germans and Jewish Poles" and wrote that, based on his own recent observations, they were in a "state of renaissance". A report on Philipps' visit was collected by the Foreign Office

Foreign may refer to:

Government

* Foreign policy, how a country interacts with other countries

* Ministry of Foreign Affairs, in many countries

** Foreign Office, a department of the UK government

** Foreign office and foreign minister

* United S ...

.

Visits to Rome

By October 1938 Philipps was inRome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus (Romulus and Remus, legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

...

, having been invited as one of the British delegates at that year's Volta Conference

The Volta Conference was the name given to each of the international conferences held in Italy by the Royal Academy of Science in Rome, and funded by the Alessandro Volta Foundation. In the interwar period, they covered a number of topics in sc ...

, where colonial policy was discussed. Recounting his experiences in an article printed in the '' Journal of the Royal African Society'', he revealed that part of the hospitality provided was a trip to Italian Libya

Libya ( it, Libia; ar, ليبيا, Lībyā al-Īṭālīya) was a colony of the Fascist Italy located in North Africa, in what is now modern Libya, between 1934 and 1943. It was formed from the unification of the colonies of Italian Cyrenaica ...

(the Governor-General, Marshal Balbo, was participating at the conference), and was impressed by what had been achieved by the mass migration of Italian settlers. Philipps himself spoke during the 16th session, on the afternoon of the final day of the conference, on ways in which shared participation and common goals in Africa could avert the path to war in Europe. He suggested to delegates that if the European powers could develop Africa 'as a field of opportunity, equal guarantee, and equal rights for all the nations of the European family' this could have the effect of 'resolidarising' Europeans in Europe itself. Essentially, Philipps was in favour of 're-admitting Germany as a partner at the table where tropical riches were to be re-distributed' in the hope this would avoid conflict in Europe.

Philipps was once again in Rome in June 1939 to attend a conference held by the International Colonial Institute

The International Institute of Differing Civilizations (french: Institut international des civilisations différentes, INCIDI) was an organization based in Brussels, Belgium, founded

in 1894 as the International Colonial Institute (french: Institu ...

. He was one of the two British representatives – the other being Henry Gollan. The conference, chaired by Luigi Federzoni

Luigi Federzoni (27 September 1878 – 24 January 1967) was a twentieth-century Italian nationalist and later Fascist politician.

Biography

Federzoni was born in Bologna. Educated at the university there, he took to journalism and literature, an ...

, was on three subjects, namely 'the nutrition of "Natives"', the 'juridical situation of "Native" women' and the 'financial contribution of "Natives" to the expenses of administration'. An italophile

Italophilia is the admiration, appreciation or emulation of Italy, its people, ideals, civilization, and culture. Its opposite is Italophobia.

The extent to which Italian civilization has shaped Western civilization and, by extension, the ci ...

, Philipps enjoyed the luncheon arranged by Federzoni and Attilio Teruzzi

Attilio Teruzzi (5 May 1882 – 26 April 1950) was an Italian soldier, colonial administrator, and Fascist politician.

Born in Milan, Teruzzi completed military studies and was promoted colonel in the Italian Army at the unusual age of 28. In 19 ...

, which was held outside in the shady surroundings of the Villa Borghese gardens

Villa Borghese is a landscape garden in Rome, containing a number of buildings, museums (see Galleria Borghese) and attractions. It is the third largest public park in Rome (80 hectares or 197.7 acres) after the ones of the Villa Doria Pamphili an ...

, and praised the efforts of the workers involved in the reclamation of the Pontine Marshes

250px, Lake Fogliano, a coastal lagoon in the Pontine Plain

The Pontine Marshes (, also ; it, Agro Pontino , formerly also ''Paludi Pontine''; la, Pomptinus Ager by Titus Livius, ''Pomptina Palus'' (singular) and ''Pomptinae Paludes'' (plur ...

:

The Ukrainian Question

During the 1930s Philipps became friendly with the Ukrainian Bureau, a lobbying centre formed in 1931 in London by Ukrainian-American Jacob Makohin to advocate for Ukrainian nationhood, promote the interests of Ukrainian minorities, and provide an outlet for information on Ukrainian issues that stood outside the Soviet sphere of influence. On several occasions in the 1930s he visited Ukraine and

During the 1930s Philipps became friendly with the Ukrainian Bureau, a lobbying centre formed in 1931 in London by Ukrainian-American Jacob Makohin to advocate for Ukrainian nationhood, promote the interests of Ukrainian minorities, and provide an outlet for information on Ukrainian issues that stood outside the Soviet sphere of influence. On several occasions in the 1930s he visited Ukraine and Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-eight ...

(especially the latter) in the guise of a newspaper correspondent and thus kept up-to-date with political developments in these countries, though his motivation for travel may have been intelligence gathering rather than any duties as a journalist.Caccia, 2010, p. 74

Officials in the Foreign Office during this period were not as sympathetic as Philipps to the claims of Ukrainian nationalists, owing to a desire to avoid offending Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populou ...

and the Soviet Union, and did not think it worthwhile to press the Polish government over its annexation of Eastern Galicia in the aftermath of the Polish-Ukrainian War (1918–1919). Reports of atrocities committed by the Polish government during the Pacification of Ukrainians in Eastern Galicia were collected and noted, but not acted upon. Whitehall civil servants concluded they could not encourage 'a movement of national liberation which we could in no circumstances support in anything but words' – effectively Britain's answer to the 'Ukrainian Question' during the interwar period. This disappointed lobbyists like Arnold Margolin, a Jewish Ukrainian lawyer, who insisted British failure to make promises of assistance to the Ukrainian cause would guarantee Ukrainians falling for the overtures of Nazi Germany in any upcoming war.

While the British government was not motivated to intervene itself, it was still concerned with the designs of other European powers. British officials worried that Germany might strengthen itself by aligning with Ukrainian national aspirations before launching a conflict with the Soviet Union. Towards the end of 1938, Philipps' mentor Lord Halifax, by now Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs, Foreign Secretary, was being told that the 'Ukrainian question seems likely to boil up' very soon. Any such German plan would, however, require driving a wedge through Polish-held territory in order to reach Soviet Ukraine, something Poland was very unlikely to agree to. Consequently, some British analysts began to feel war between Germany and Poland was unavoidable, though Lord Halifax was also informed by experts that because the Poles would be unwilling to allow the Germans to move across their territory without a fight, Hitler would probably deploy his forces to the west first – a prediction Invasion of Poland, that would turn out to be inaccurate.

In 1939, in the aftermath of the Anglo-Polish military alliance#Britain makes assurance to Poland, British guarantee to Poland, Philipps, armed with briefs prepared for him by Vladimir Kysilewsky (Director of the Ukrainian Bureau) and vetted by the historian Robert William Seton-Watson, had lengthy conversations with Lord Halifax. According to Canadian historian Orest T. Martynowych, Philipps was seen as highly useful to the Ukrainian cause due to his "extensive personal and family connections in high places".

Mission to Canada, 1940–1944

With the outbreak of theSecond World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

Philipps was eager to do something for his country, but carried injuries from the First World War that prevented him from rejoining the military. He claimed to be "ashamed to seem to be doing so very little" in a letter he wrote to Lord Halifax.

Philipps disembarked in Montreal with his wife and son in June 1940, carrying letters of introduction from Lord Halifax. Used to high-living, he was furious with Thomas Cook & Son, Thomas Cook agents for being assigned a second-class cabin and made his disgust known upon arrival. He had been sent to Canada as one of many propagandists, part of a Ministry of Information (United Kingdom), Ministry of Information project to shape North American public opinion in favour of British war objectives. The Fall of France and a series of British reverses, leading to the Dunkirk evacuation, evacuation of British forces from Dunkirk, made ensuring ongoing Canadian support vital. Philipps was specifically tasked with monitoring the viewpoints of minority groups in Canada, some of which were Fascism, fascist in nature, and could potentially undermine the British war effort. The United Hetman Organization (UHO), a Ukrainian monarchist group led by Pavlo Skoropadskyi, was identified as the gravest concern due to its contacts in Berlin.

He soon began travelling across Canada on a mission to gauge the loyalty of the foreign-born labour force, in the process sending various unsolicited reports to the mystified Canadian Deputy Minister of War Services T. C. Davis. He also reported regularly to Lord Halifax on various matters, including the reception of British evacuees in Canada and the possibility of evacuating the British government to Ottawa in the event of an Operation Sea Lion, expected German invasion. As fears of a German invasion grew, the British upper-classes rushed to secure evacuation berths for wives, children and servants.Kristmanson, 1999, p. 180 On this matter Philipps wrote to Lord Halifax in July on the assimilation of British children into Canadian homes; having already provided assistance to his cousin, Elsbeth Dimsdale, on planning the evacuation of her children.

Philipps' travels across Canada have been described as a "frenetic itinerary of public speaking and factory inspections". Towards the public he maintained the pretense that he was in North America purely to go on a public speaking tour that had been arranged in advance under the auspices of the National Council of Education. He spoke to business clubs, local clubs, and the Canadian Institute of International Affairs and lectured on the Near East and Eastern Europe in the aftermath of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact. While on this tour he was invited by organisers to give lectures to local immigrant groups on current events in Europe, and used this tour to relay information on the views of the European immigrant population in Canada to the British government. Ukrainian Canadians, Ukrainians were of particular concern: they were divided into multiple organisations and did not agree on the political future of their homeland. Philipps himself was pleased with the reception he received from immigrant communities in the more remote parts of Canada, comparing it to what he had witnessed with Lawrence of Arabia among the Arab rebels during the Great War. Officials, perhaps sensitive to the hidden purpose of his "public speaking tour", denied Philipps had any connection with the Foreign Office.

In April 1941, Davis offered Philipps the role of Director of the European Section the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) on a temporary basis, tasked with him helping to build unity behind the war effort amongst Canadian immigrant communities.Hillmer, p. 16 His first major assignment was a trip to the United States to find out what was being done in that country to promote integration of the immigrant ethnic population, and how these communities regarded the federal authorities. He visited many cities on this tour, including Pittsburgh, Chicago, Atlanta and Washington, D. C.; sending detailed memoranda to his new superior Commissioner Stuart Wood (police commissioner), Stuart Wood from "virtually every stop" on his route. Philipps' extravagances, which included expenses claims for first-class rail travel and valet services, caused concerns with the frugal RCMP as he made his way across Canada and the United States to interview foreign-born workers. On the other hand, his suggestion of radio broadcasts to influence immigrant populations met with the approval of Commissioner Wood.

In Atlanta he briefly interrupted his duties with the RCMP to attend W. E. B. Du Bois' First Phylon Conference at Fisk University. Asked by Du Bois to set out what effective decolonisation would look like, he suggested the British system of parliamentary democracy would be unsuitable for Africa due to the tribal loyalties of Africans. Following the conference, he reported to Gerald Campbell, his contact in the British Embassy to Washington, that his talk prompted "numerous questions"; these were generally hostile, which Philipps blamed on misrepresentation from communist sources.

On his return journey to Canada he briefly visited New York and met with Michael Huxley at the Inter-Allied Information Committee on the fifth floor of the Rockefeller Center.Kristmanson, 1999, pp. 194–195. Huxley was the director of this white propaganda outfit, launched in 1940 to win American support for Britain by casting British war aims in light of a new "internationalism" – intended to counteract American suspicions that Britain's true aim was to preserve its empire. Philipps was there to seek Huxley's views on a proposal of Count Vladislav Radziwill to have Poles trained in Canada for sabotage missions in occupied Poland. Huxley replied that he was "not competent to respond" and any suggestions from Philipps should be directed to Malcolm MacDonald, the List of High Commissioners of the United Kingdom to Canada, High Commissioner to Canada. Huxley regarded Philipps with caution, and the latter would leave unaware of British Security Co-ordination (BSC), a covert black propaganda outfit, operating from the very same building in support of British interests. Philipps may have been left "in the dark" by Huxley as he had already earned a reputation with British officials in Canada for straying beyond his remit by sending intelligence reports on matters that had nothing to do with the foreign-born labour force, which irritated his superior MacDonald. In any case, his "explicit valorization of the old British Empire" was not in keeping with the internationalist rhetoric British intelligence was keen to project.

In Atlanta he briefly interrupted his duties with the RCMP to attend W. E. B. Du Bois' First Phylon Conference at Fisk University. Asked by Du Bois to set out what effective decolonisation would look like, he suggested the British system of parliamentary democracy would be unsuitable for Africa due to the tribal loyalties of Africans. Following the conference, he reported to Gerald Campbell, his contact in the British Embassy to Washington, that his talk prompted "numerous questions"; these were generally hostile, which Philipps blamed on misrepresentation from communist sources.

On his return journey to Canada he briefly visited New York and met with Michael Huxley at the Inter-Allied Information Committee on the fifth floor of the Rockefeller Center.Kristmanson, 1999, pp. 194–195. Huxley was the director of this white propaganda outfit, launched in 1940 to win American support for Britain by casting British war aims in light of a new "internationalism" – intended to counteract American suspicions that Britain's true aim was to preserve its empire. Philipps was there to seek Huxley's views on a proposal of Count Vladislav Radziwill to have Poles trained in Canada for sabotage missions in occupied Poland. Huxley replied that he was "not competent to respond" and any suggestions from Philipps should be directed to Malcolm MacDonald, the List of High Commissioners of the United Kingdom to Canada, High Commissioner to Canada. Huxley regarded Philipps with caution, and the latter would leave unaware of British Security Co-ordination (BSC), a covert black propaganda outfit, operating from the very same building in support of British interests. Philipps may have been left "in the dark" by Huxley as he had already earned a reputation with British officials in Canada for straying beyond his remit by sending intelligence reports on matters that had nothing to do with the foreign-born labour force, which irritated his superior MacDonald. In any case, his "explicit valorization of the old British Empire" was not in keeping with the internationalist rhetoric British intelligence was keen to project.

Nationalities Branch

After completing his work with the RCMP, he continued as an adviser to the Canadian Government on immigrant European communities, working to increase the loyalty of "new Canadians" at the newly formed Nationalities Branch. Also joining him was Vladimir Kysilewsky – the old Director of the Ukrainian Bureau in London – who would continue to be a close confidant in Ottawa. He became friendly with Oliver Mowat Biggar, the Director of Censorship.Kristmanson, 1999, pp. 205–206 Philipps also received intelligence from Bermuda, where his cousin Charles des Graz was Director of Imperial Censorship. Nevertheless, his period with the Canadian Government was less successful than his spell with the RCMP. The Ukrainian Canadian Committee (UCC) – an attempt at bringing ethnic Ukrainians in Canada under a single body (which later developed into the Ukrainian Canadian Congress) – was successfully established after two days of intense negotiations in Winnipeg. However, its anti-communist nature, achieved by sidelining the communist elements during the negotiations, proved to be less useful once the Germans launched Operation Barbarossa in the summer of 1941 and Canada, alongside the rest of the British Empire, was Allies of World War II, allied with the Soviet Union. Philipps had, by the time of the formation of the UCC, already become known in Canada for his sympathy towards the idea of Ukrainian independence, earning him the permanent distrust of Ukrainian-Canadians with communist leanings. Beyond assuring the loyalties of ethnic Ukrainians in Canada he also hoped his efforts would help cement a British-Ukrainian alliance that would stand against Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union. As far as he was concerned, Ukrainian nationhood was not only morally right, but, given the guarantee that the British government had previously made to Poland, politically fair and logical. For Philipps, the key principle of the Allies was a belief in Self-determination, political self-determination, which made a failure to support Ukraine inconceivable. Such support, he argued, would surely reflect well on both Britain's war aims and her moral reputation: He thought it wrong for Britain to make any guarantees of Ukrainian sovereignty it could not keep, but, as the war was apparently being fought for the right of nations to organise themselves, believed the Allies would eventually have to face up to this principle. Before the launch of Operation Barbarossa he had suggested that recognition of Ukrainian sovereignty might also be strategically necessary – fearing that Nazi Germany would make overtures to nationalist Ukrainians in exchange for military assistance in a future conflict against the Soviet Union.Kordan, pp. 42–43 He worried that Hitler might offer the Ukrainians — This belief in the self-determination of Ukraine was not shared by the government in London, who wished to maintain normal relations with the Soviet Union, and had shown no appetite to prejudice relations even at the height of the state-sponsored Holodomor, Great Famine in 1933. While working at the Nationalities Branch Philipps gravitated towards his old contacts in the RCMP for information and, turning towards the United States, cultivated counterparts in the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), Office of Strategic Services (OSS), and the State Department.Kristmanson, 1999, p. 194. Of these, DeWitt Clinton Poole of the OSS was his most regular contact and closest U.S. equivalent. Alarmed by contacts reports that "daily Axis short-wave propaganda broadcasts" were influencing foreign-born workers, Philipps repeatedly encouraged the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC) to introduce its own foreign language broadcasts.Kristmanson, 1999, p. 196. Giving in to Philipps' "incessant lobbying", the CBC began producing one fifteen minute programme in Italian, which earned Philipps the thanks of Italian Canadians, but otherwise stuck to its usual schedule of English and French-language broadcasting.Criticism

Philipps and his wife had acrimoniously separated shortly after arriving in Ottawa, which hurt his reputation in the capital.Kristmanson, 1999, p. 192. By October 1941, as the Nationalities Branch was taking shape, mother and son were living with government press censor Ladislaus Biberovich and his wife. This was the catalyst for an ongoing feud between Philipps and Biberovich. Philipps' efforts in the Nationalities Branch were also damaged by his eccentricity and unorthodox personal style, which proved to be jarring for members of the Canadian establishment. Politicians Louis St. Laurent and Colin W. G. Gibson, Colin Gibson, fellow residents of the Roxborough Apartments, were often ambushed by Philipps, who would roam the corridors in his dressing gown. His position was further weakened by the new Minister of National War Services, General Leo LaFleche. LaFleche, who took an almost instant dislike to Philipps, found him so annoying that he had him barred from his office. Problems soon emerged for Philipps outside of politics. He suffered a painful back injury after being struck by a toboggan full of children on O'Connor Street during his walk to work. He was also the victim of a stinging character assassination in the autumn of 1942. An article had appeared in a New York paper ''The Hour'' (edited by Albert Kahn (journalist), Albert Kahn, a Stalinism, Stalinist agent) – and later reproduced in ''The New Republic'' – that accused him of being a Fascist sympathizer. This allegation was founded on his friendships with Lord Halifax, Lady Astor and other members of the controversial Cliveden set. Philipps defended himself in a November letter sent to ''The Globe and Mail'' but offered his resignation later that month. He was defended by T. C. Davis, Professor George Simpson of the University of Saskatchewan, and the diplomat Norman Robertson, who successfully argued he was the victim of unfair criticism; and consequently, Philipps would keep his job.Exit

This episode forced him to retire from lecturing members of the public, but his distate for communism continued to interrupt his work. In May 1943 he made a series of anti-Soviet speeches, which drew the ire of John Grierson, the new chairman of the Wartime Information Board. Grierson, determined to undermine both Philipps and the activities of Bureaucratic drift, the renegade Nationalities Branch, then started to meet with the Canadian Unity Council, an alliance of ethnic organisations that opposed Philipps. They argued Philipps saw himself as a "guardian" of "helpless and divided" ethnic communities that depended upon him to lead them towards Canadian identity – an attitude they regarded as patronising. Grierson's efforts would come to nought however, as General LaFleche refused to have Philipps removed despite his personal dislike for the man, or to transfer the Nationalities Branch to Grierson's control. LaFleche felt this would hurt ethnic minority outreach efforts and create an opening that "communist agitators" would take advantage of.UNRRA, 1944–1945

In 1944 Philipps successfully lobbied for a role at the United Nations. He was appointed Chief of Planning Resettlement of Displaced Persons with theUnited Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration

United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA) was an international relief agency, largely dominated by the United States but representing 44 nations. Founded in November 1943, it was dissolved in September 1948. it became part o ...

(UNRRA), working initially from New York, and later Germany.

Philipps quickly became disillusioned by the forced repatriations of Soviet citizens at the conclusion of the war, which came as a consequence of the Yalta Agreement signed by the Allied Powers. He believed that displaced persons were entitled to choose, for political or economic reasons, not to return to their country of origin, and be informed of the consequences of their choice. He did not spend long in his UNRRA job and resigned in 1945. In a letter written in May that year to Watson Kirkconnell he compared the fate of refugees from the Soviet Union to slavery:

Writing in his memoirs, Kirkconnell revealed that Philipps was suspicious of the eagerness with which some Allied officials carried out this policy and believed that the "officialdom" of the western Allies was "honeycombed with Communists and Fellow traveller, fellow-travellers" more than willing to help along the programme.Kirkconnell, 1967, p. 357 In the same text he stressed how uneasy Philipps was with the ramifications of Yalta, revealing the contents of a 1948 letter from Philipps where he argued the following:

Philipps was also critical of certain aspects in how the United Nations was organised, which he felt could "paralyze its actions and effectiveness", namely: the recruitment of staff according to a nationality quota, the use of multiple languages in all its operations, and the United Nations Security Council veto power, veto power of some states, including the Soviet Union.

Post-war

Advocacy