Thomas Hood on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Thomas Hood (23 May 1799 – 3 May 1845) was an English poet, author and humorist, best known for poems such as " The Bridge of Sighs" and " The Song of the Shirt". Hood wrote regularly for ''

''The Poetical Works of Thomas Hood''

(London, 1903). Hood was the father of the playwright and humorist Tom Hood (1835–1874) and the children's writer

Thomas Hood was born to Thomas Hood and Elizabeth Sands in the

Thomas Hood was born to Thomas Hood and Elizabeth Sands in the

Hood married Jane Reynolds (1791–1846). on 5 May 1824. They settled at 2 Robert Street, Adelphi, London. Their first child died at birth, but a daughter,

Hood married Jane Reynolds (1791–1846). on 5 May 1824. They settled at 2 Robert Street, Adelphi, London. Their first child died at birth, but a daughter,

In another annual called the ''Gem'' appeared the verse story of

In another annual called the ''Gem'' appeared the verse story of

Hood's best known work in his lifetime was " The Song of the Shirt", a verse lament for a London seamstress compelled to sell shirts she had made, the proceeds of which lawfully belonged to her employer, in order to feed her malnourished and ailing child. Hood's poem appeared in one of the first editions of ''

Hood's best known work in his lifetime was " The Song of the Shirt", a verse lament for a London seamstress compelled to sell shirts she had made, the proceeds of which lawfully belonged to her employer, in order to feed her malnourished and ailing child. Hood's poem appeared in one of the first editions of ''

The Memorials of Thomas Hood – Vol. 1

' and

The Memorials of Thomas Hood – Vol. 2

' (Boston: Ticknor & Fields, 1860) *

Thomas Hood; His Life and Times

' (New York: John Lane, 1909) *Alex Elliot (ed.),

Hood in Scotland

' (Dundee: James P. Matthew & Co., 1885) *J. C. Reid, ''Thomas Hood'' (New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1963)

Thomas Hood

at the

The Poetical Works of Thomas Hood

a

The University of Adelaide Library

biography & selected writings at gerald-massey.org.uk *

"Thomas Hood"

(accessed 26 November 2010)Finding aid to the Thomas Hood letters at Columbia University. Rare Book & Manuscript Library

* Thomas Hood Collection. General Collection, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. {{DEFAULTSORT:Hood, Thomas 1799 births 1845 deaths 19th-century English poets English essayists Victorian poets Writers from London Burials at Kensal Green Cemetery Male essayists English male poets Poets associated with Dundee

The London Magazine

''The London Magazine'' is the title of six different publications that have appeared in succession since 1732. All six have focused on the arts, literature and miscellaneous topics.

1732–1785

''The London Magazine, or, Gentleman's Monthly I ...

'', '' Athenaeum'', and ''Punch

Punch commonly refers to:

* Punch (combat), a strike made using the hand closed into a fist

* Punch (drink), a wide assortment of drinks, non-alcoholic or alcoholic, generally containing fruit or fruit juice

Punch may also refer to:

Places

* Pu ...

''. He later published a magazine largely consisting of his own works. Hood, never robust, had lapsed into invalidism by the age of 41 and died at the age of 45. William Michael Rossetti in 1903 called him "the finest English poet" between the generations of Shelley and Tennyson

Alfred Tennyson, 1st Baron Tennyson (6 August 1809 – 6 October 1892) was an English poet. He was the Poet Laureate during much of Queen Victoria's reign. In 1829, Tennyson was awarded the Chancellor's Gold Medal at Cambridge for one of his ...

.Rossetti, W. M. Biographical Introduction''The Poetical Works of Thomas Hood''

(London, 1903). Hood was the father of the playwright and humorist Tom Hood (1835–1874) and the children's writer

Frances Freeling Broderip

Frances Freeling Broderip (née Hood) (11 September 1830 – 3 November 1878) was an English children's writer.

Early life

Broderip, second daughter of Thomas Hood, the poet, who died in 1845, by his wife, Jane Reynolds, who died in 1846, wa ...

(1830–1878).

Early life

Thomas Hood was born to Thomas Hood and Elizabeth Sands in the

Thomas Hood was born to Thomas Hood and Elizabeth Sands in the Poultry

Poultry () are domesticated birds kept by humans for their eggs, their meat or their feathers. These birds are most typically members of the superorder Galloanserae (fowl), especially the order Galliformes (which includes chickens, qu ...

(Cheapside

Cheapside is a street in the City of London, the historic and modern financial centre of London, which forms part of the A40 London to Fishguard road. It links St. Martin's Le Grand with Poultry. Near its eastern end at Bank junction, whe ...

), London, above his father's bookshop. His father's family had been Scottish farmers from the village of Errol near Dundee

Dundee (; sco, Dundee; gd, Dùn Dè or ) is Scotland's fourth-largest city and the 51st-most-populous built-up area in the United Kingdom. The mid-year population estimate for 2016 was , giving Dundee a population density of 2,478/km2 or ...

. The elder Hood was a partner in the business of Vernor, Hood and Sharp, a member of the Associated Booksellers. Hood's son, Tom Hood, claimed that his grandfather had been the first to open up the book trade with America and had had great success with new editions of old books.

"Next to being a citizen of the world," writes Thomas Hood in his ''Literary Reminiscences'', "it must be the best thing to be born a citizen of the world's greatest city." On the death of her husband in 1811, Hood's mother moved to Islington

Islington () is a district in the north of Greater London, England, and part of the London Borough of Islington. It is a mainly residential district of Inner London, extending from Islington's High Street to Highbury Fields, encompassing the ...

, where he had a schoolmaster who in appreciating his talents, "made him feel it impossible not to take an interest in learning while he seemed so interested in teaching." Under the care of this "decayed dominie", he earned a few guineas – his first literary fee – by revising for the press a new edition of the 1788 novel ''Paul and Virginia

''Paul et Virginie'' (sometimes known in English as ''Paul and Virginia'') is a novel by Jacques-Henri Bernardin de Saint-Pierre, first published in 1788. The novel's title characters are friends since birth who fall in love. The story is set ...

''.

Hood left his private schoolmaster at 14 years of age and was admitted soon after into the counting house

A counting house, or counting room, was traditionally an office in which the financial books of a business were kept. It was also the place that the business received appointments and correspondence relating to demands for payment.

As the use of ...

of a friend of his family, where he "turned his stool into a Pegasus

Pegasus ( grc-gre, Πήγασος, Pḗgasos; la, Pegasus, Pegasos) is one of the best known creatures in Greek mythology. He is a winged divine stallion usually depicted as pure white in color. He was sired by Poseidon, in his role as hor ...

on three legs, every foot

The foot ( : feet) is an anatomical structure found in many vertebrates. It is the terminal portion of a limb which bears weight and allows locomotion. In many animals with feet, the foot is a separate organ at the terminal part of the leg mad ...

, of course, being a dactyl or a spondee." However, the uncongenial profession affected his health, which was never strong, and he began to study engraving. The exact nature and course of his study is unclear: various sources tell different stories. Reid emphasizes his work under his maternal uncle Robert Sands, but no deeds of apprenticeship exist and his letters show he studied with a Mr Harris. Hood's daughter in her ''Memorials'' mentions her father's association with the Le Keux brothers, who were successful engravers in the City.

The labour of engraving was no better for his health than the counting house had been, and Hood was sent to his father's relations at Dundee, Scotland

Dundee (; sco, Dundee; gd, Dùn Dè or ) is Scotland's fourth-largest city and the 51st-most-populous built-up area in the United Kingdom. The mid-year population estimate for 2016 was , giving Dundee a population density of 2,478/km2 or ...

. There he stayed in the house of his maternal aunt, Jean Keay, for some months. Then on falling out with her, he moved on to the boarding house of one of her friends, Mrs Butterworth, where he lived for the rest of his time in Scotland. In Dundee, Hood made a number of close friends with whom he continued to correspond for many years. He led a healthy outdoor life, but also became a wide and indiscriminate reader. At the same time he began seriously to write poetry and he appeared in print for the first time, with a letter to the editor of the ''Dundee Advertiser''.

Literary society

Before long Hood was contributing humorous and poetical pieces to provincial newspapers and magazines. As a proof of his literary vocation, he would write out his poems in printed characters, believing that this process best enabled him to understand his own peculiarities and faults, and probably unaware thatSamuel Taylor Coleridge

Samuel Taylor Coleridge (; 21 October 177225 July 1834) was an English poet, literary critic, philosopher, and theologian who, with his friend William Wordsworth, was a founder of the Romantic Movement in England and a member of the Lak ...

had recommended some such method of criticism when he said he thought, "Print settles it." On his return to London in 1818 he applied himself to engraving

Engraving is the practice of incising a design onto a hard, usually flat surface by cutting grooves into it with a burin. The result may be a decorated object in itself, as when silver, gold, steel, or glass are engraved, or may provide an in ...

, which enabled him later to illustrate his various humours and fancies.

In 1821, John Scott, editor of ''The London Magazine

''The London Magazine'' is the title of six different publications that have appeared in succession since 1732. All six have focused on the arts, literature and miscellaneous topics.

1732–1785

''The London Magazine, or, Gentleman's Monthly I ...

'', was killed in a duel

A duel is an arranged engagement in combat between two people, with matched weapons, in accordance with agreed-upon rules.

During the 17th and 18th centuries (and earlier), duels were mostly single combats fought with swords (the rapier and ...

, and the periodical passed into the hands of some friends of Hood, who proposed to make him sub-editor. This post at once introduced him to the literary society

A literary society is a group of people interested in literature. In the modern sense, this refers to a society that wants to promote one genre of writing or a specific author. Modern literary societies typically promote research, publish newsle ...

of the time. He gradually developed his powers by becoming an associate of John Hamilton Reynolds, Charles Lamb

Charles Lamb (10 February 1775 – 27 December 1834) was an English essayist, poet, and antiquarian, best known for his '' Essays of Elia'' and for the children's book '' Tales from Shakespeare'', co-authored with his sister, Mary Lamb (1764� ...

, Henry Cary, Thomas de Quincey

Thomas Penson De Quincey (; 15 August 17858 December 1859) was an English writer, essayist, and literary critic, best known for his '' Confessions of an English Opium-Eater'' (1821). Many scholars suggest that in publishing this work De Quinc ...

, Allan Cunningham, Bryan Procter, Serjeant Talfourd

Sir Thomas Noon Talfourd SL (26 May 179513 March 1854) was an English judge, Radical politician and author.

Life

The son of a well-to-do brewer, Talfourd was born in Reading, Berkshire. He received his education at Hendon and Reading School. ...

, Hartley Coleridge

Hartley Coleridge, possibly David Hartley Coleridge (19 September 1796 – 6 January 1849), was an English poet, biographer, essayist, and teacher. He was the eldest son of the poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge. His sister Sara Coleridge was a poet a ...

, the peasant-poet John Clare

John Clare (13 July 1793 – 20 May 1864) was an English poet. The son of a farm labourer, he became known for his celebrations of the English countryside and sorrows at its disruption. His work underwent major re-evaluation in the late 20th ce ...

, and other contributors.

Family life

Hood married Jane Reynolds (1791–1846). on 5 May 1824. They settled at 2 Robert Street, Adelphi, London. Their first child died at birth, but a daughter,

Hood married Jane Reynolds (1791–1846). on 5 May 1824. They settled at 2 Robert Street, Adelphi, London. Their first child died at birth, but a daughter, Frances Freeling Broderip

Frances Freeling Broderip (née Hood) (11 September 1830 – 3 November 1878) was an English children's writer.

Early life

Broderip, second daughter of Thomas Hood, the poet, who died in 1845, by his wife, Jane Reynolds, who died in 1846, wa ...

(1830–1878), was born soon after they moved to Winchmore Hill, and after they had then moved in 1832 to Lake House, Wanstead, a son, Tom Hood (1835–1874), was also born. Both children took up in Hood's profession: Frances became a children's writer and Tom a humorist and playwright, and they later collaborated in collecting and publishing their father's work. Although constantly worried about money and health, the Hoods were a devoted, affectionate family, as ''Memorials of Thomas Hood'' (1860), based on his letters and compiled by his children, testifies.

''Odes and Addresses'' – Hood's first volume – was written in conjunction with his brother-in-law John Hamilton Reynolds, a friend of John Keats

John Keats (31 October 1795 – 23 February 1821) was an English poet of the second generation of Romantic poets, with Lord Byron and Percy Bysshe Shelley. His poems had been in publication for less than four years when he died of tuberculos ...

. Coleridge wrote to Lamb averring that the book must be the latter's work. Keats wrote two poems for Jane Reynolds: "O Sorrow!" (October 1817) and "On a Leander Gem which Miss Reynolds, my Kind Friend, Gave Me" (c. March 1817). Also from this period are ''The Plea of the Midsummer Fairies'' (1827) and a dramatic romance, ''Lamia'', published later. ''The Plea'' was a book of serious verse, but Hood was known as a humorist and the book was ignored almost entirely.

Hood was fond of practical jokes, which he was said to have enjoyed inflicting on members of his family. In the ''Memorials'' there is a story of Hood instructing his wife Jane to purchase some fish for the evening meal from a woman who regularly came to the door selling her husband's catch. But he warns her to watch for plaice

Plaice is a common name for a group of flatfish that comprises four species: the European, American, Alaskan and scale-eye plaice.

Commercially, the most important plaice is the European. The principal commercial flatfish in Europe, it is al ...

that "has any appearance of red or orange spots, as they are a sure sign of an advanced stage of decomposition." Mrs Hood refused to purchase the fish-seller's plaice, exclaiming, "My good woman... I could not think of buying any plaice with those very unpleasant red spots!" The fish-seller was amazed at such ignorance of what plaice look like.

The series of the ''Comic Annual'', dating from 1830, was a type of publication popular at the time, which Hood undertook and continued almost unassisted for several years. He would cover all the leading events of the day in caricature, without personal malice, and with an undercurrent of sympathy. Readers were also treated to an incessant use of pun

A pun, also known as paronomasia, is a form of word play that exploits multiple meanings of a term, or of similar-sounding words, for an intended humorous or rhetorical effect. These ambiguities can arise from the intentional use of homophoni ...

s, of which Hood had written in his own vindication, "However critics may take offence,/A double meaning has double sense", but as he gained experience as a writer, his diction became simpler.

Later writings

In another annual called the ''Gem'' appeared the verse story of

In another annual called the ''Gem'' appeared the verse story of Eugene Aram

Eugene Aram (170416 August 1759) was an English philologist, but also infamous as the murderer celebrated by Thomas Hood in his ballad ''The Dream of Eugene Aram'', and by Edward Bulwer-Lytton in his 1832 novel '' Eugene Aram''.

Early life

Ar ...

. Hood started a magazine in his own name, mainly sustained by his own activity. He did the work from a sick-bed from which he never rose, and there also composed well-known poems such as "The Song of the Shirt", which appeared anonymously in the Christmas number of ''Punch

Punch commonly refers to:

* Punch (combat), a strike made using the hand closed into a fist

* Punch (drink), a wide assortment of drinks, non-alcoholic or alcoholic, generally containing fruit or fruit juice

Punch may also refer to:

Places

* Pu ...

'', 1843 and was immediately reprinted in ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper '' The Sunday Times'' ( ...

'' and other newspapers across Europe. It was dramatised by Mark Lemon as ''The Sempstress'', printed on broadsheets and cotton handkerchiefs, and was highly praised by many of the literary establishment, including Charles Dickens

Charles John Huffam Dickens (; 7 February 1812 – 9 June 1870) was an English writer and social critic. He created some of the world's best-known fictional characters and is regarded by many as the greatest novelist of the Victorian er ...

. Likewise " The Bridge of Sighs" and "The Song of the Labourer", which were also translated into German by Ferdinand Freiligrath Ferdinand Freiligrath (17 June 1810 – 18 March 1876) was a German poet, translator and liberal agitator, who is considered part of the Young Germany movement.

Life

Freiligrath was born in Detmold, Principality of Lippe. His father was a teacher. ...

. These are plain, solemn pictures of the conditions of life, which appeared shortly before Hood's death in May 1845.

Hood was associated with the '' Athenaeum'', started in 1828 by James Silk Buckingham

James Silk Buckingham (25 August 1786 – 30 June 1855) was a British author, journalist and traveller, known for his contributions to Indian journalism. He was a pioneer among the Europeans who fought for a liberal press in India.

Early life

B ...

, and was a regular contributor to it for the rest of his life. Prolonged illness brought straitened circumstances. Applications were made by a number of Hood's friends to the Prime Minister, Sir Robert Peel, to grant Hood a civil list pension, with which the state rewarded literary men. Peel was known to be an admirer of Hood's work and in the last few months of Hood's life he gave Jane Hood the sum of £100 without her husband's knowledge, to alleviate the family's debts. The pension that Peel's government bestowed on Hood was continued to his wife and family after his death. Jane Hood, who also suffered from poor health, had put tremendous energy into tending her husband in his last year and died only 18 months later. The pension then ceased, but Peel's successor Lord John Russell

John Russell, 1st Earl Russell, (18 August 1792 – 28 May 1878), known by his courtesy title Lord John Russell before 1861, was a British Whig and Liberal statesman who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1846 to 1852 and a ...

, grandfather of the philosopher Bertrand Russell

Bertrand Arthur William Russell, 3rd Earl Russell, (18 May 1872 – 2 February 1970) was a British mathematician, philosopher, logician, and public intellectual. He had a considerable influence on mathematics, logic, set theory, linguistics, a ...

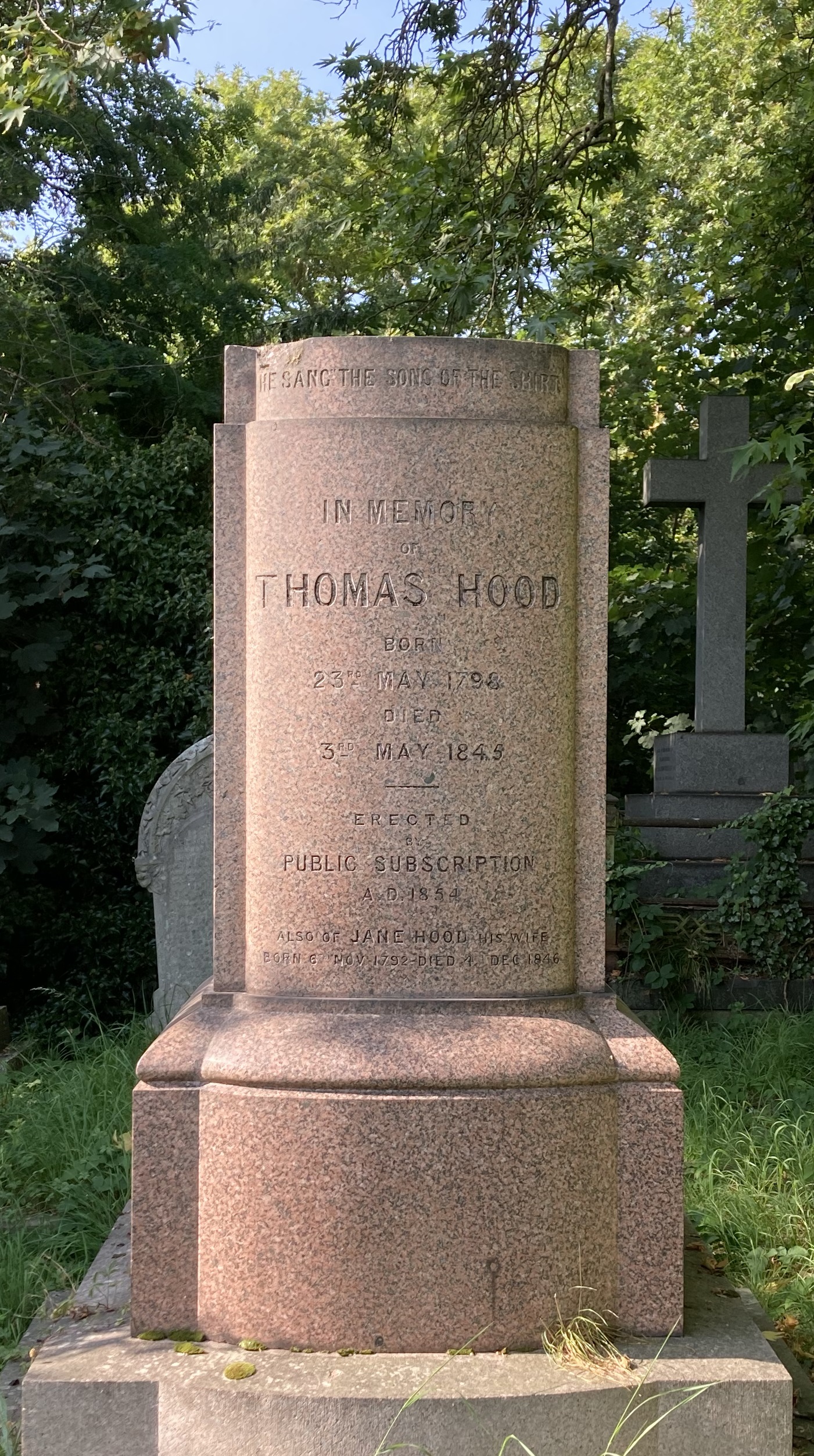

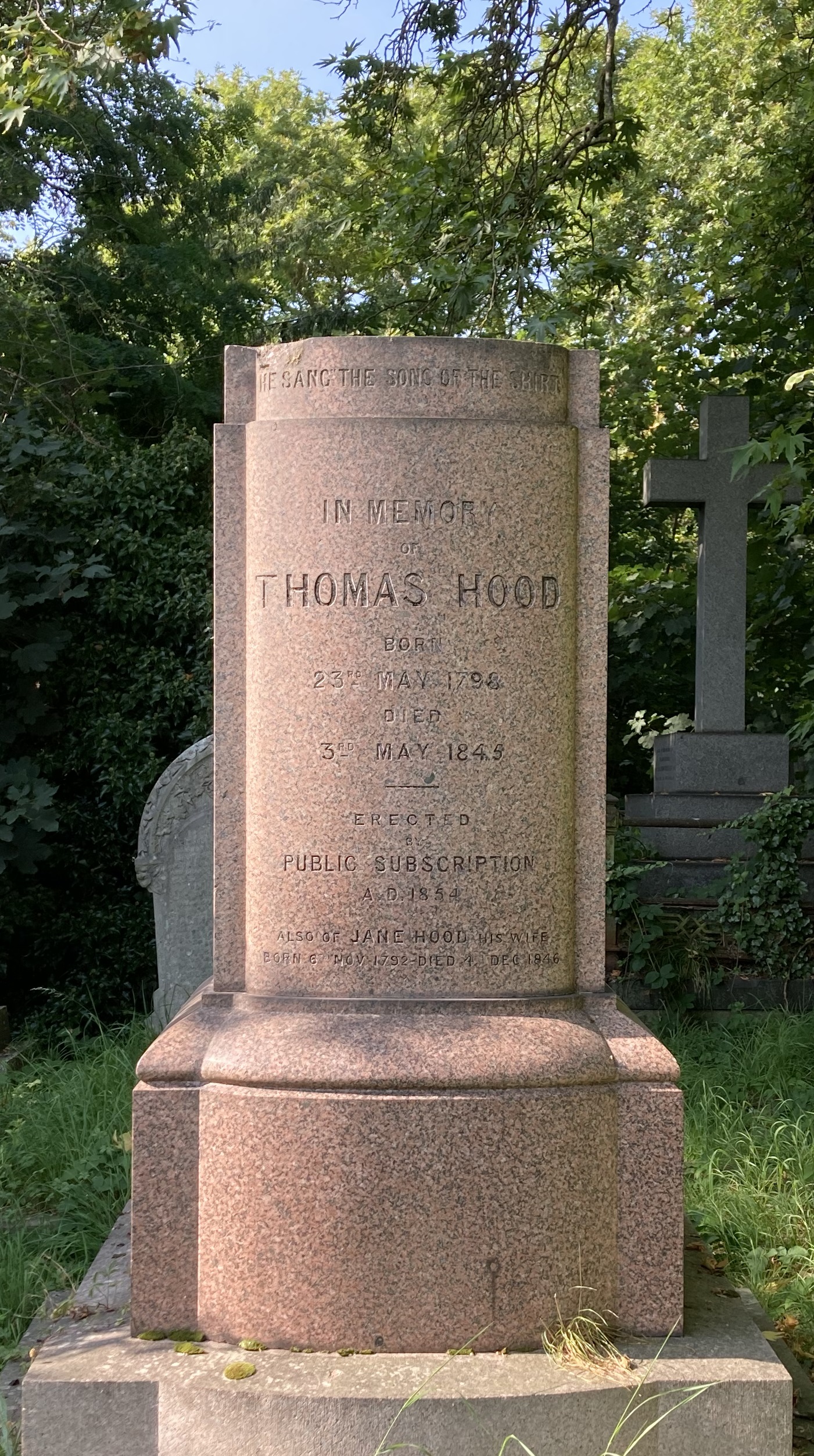

, made arrangements for a £50 pension for the maintenance of Hood's two children, Frances and Tom. Nine years later, a monument raised by public subscription in Kensal Green Cemetery

Kensal Green Cemetery is a cemetery in the Kensal Green area of Queens Park in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea in London, England. Inspired by Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris, it was founded by the barrister George Frederick ...

was unveiled by Richard Monckton Milnes

Richard Monckton Milnes, 1st Baron Houghton, FRS (19 June 1809 – 11 August 1885) was an English poet, patron of literature and a politician who strongly supported social justice.

Background and education

Milnes was born in London, the son o ...

. The monument was originally surmounted by a bronze bust of Hood by the sculptor Matthew Noble

Matthew Noble (23 March 1817 – 23 June 1876) was a leading British portrait sculptor. Carver of numerous monumental figures and busts including work memorializing Victorian era royalty and statesmen displayed in locations such as Westminster Ab ...

and had circular inset bronze roundels on either side, but all have been stolen.

Thackeray, a friend of Hood's, gave this assessment of him: "Oh sad, marvellous picture of courage, of honesty, of patient endurance, of duty struggling against pain!... Here is one at least without guile, without pretension, without scheming, of a pure life, to his family and little modest circle of friends tenderly devoted."

The house where Hood died, No. 28 Finchley Road, St John's Wood

St John's Wood is a district in the City of Westminster, London, lying 2.5 miles (4 km) northwest of Charing Cross. Traditionally the northern part of the ancient parish and Metropolitan Borough of Marylebone, it extends east to west from ...

, now has a blue plaque

A blue plaque is a permanent sign installed in a public place in the United Kingdom and elsewhere to commemorate a link between that location and a famous person, event, or former building on the site, serving as a historical marker. The term ...

.

Examples of his works

Hood wrote humorously on many contemporary issues. One of the main ones was grave robbing and selling of corpses to anatomists (seeWest Port murders

The Burke and Hare murders were a series of sixteen killings committed over a period of about ten months in 1828 in Edinburgh, Scotland. They were undertaken by William Burke and William Hare, who sold the corpses to Robert Knox for dissectio ...

). On this serious and perhaps cruel issue, he wrote wryly,

November in London is usually cool and overcast, and in Hood's day subject to frequent smog

Smog, or smoke fog, is a type of intense air pollution. The word "smog" was coined in the early 20th century, and is a portmanteau of the words '' smoke'' and ''fog'' to refer to smoky fog due to its opacity, and odor. The word was then int ...

. In 1844, he wrote the poem, "No!":

An example of Hood's reflective and sentimental verse is the famous "I Remember, I Remember", excerpted here:

Hood's best known work in his lifetime was " The Song of the Shirt", a verse lament for a London seamstress compelled to sell shirts she had made, the proceeds of which lawfully belonged to her employer, in order to feed her malnourished and ailing child. Hood's poem appeared in one of the first editions of ''

Hood's best known work in his lifetime was " The Song of the Shirt", a verse lament for a London seamstress compelled to sell shirts she had made, the proceeds of which lawfully belonged to her employer, in order to feed her malnourished and ailing child. Hood's poem appeared in one of the first editions of ''Punch

Punch commonly refers to:

* Punch (combat), a strike made using the hand closed into a fist

* Punch (drink), a wide assortment of drinks, non-alcoholic or alcoholic, generally containing fruit or fruit juice

Punch may also refer to:

Places

* Pu ...

'' in 1843 and quickly became a public sensation, being turned into a popular song and inspiring social activists in defence of countless industrious labouring women living in abject poverty. An excerpt:

Modern references

*''Metro-Land

Metro-land (or Metroland) is a name given to the suburban areas that were built to the north-west of London in the counties of Buckinghamshire, Hertfordshire and Middlesex in the early part of the 20th century that were served by the Metropol ...

'' – John Betjeman

Sir John Betjeman (; 28 August 190619 May 1984) was an English poet, writer, and broadcaster. He was Poet Laureate from 1972 until his death. He was a founding member of The Victorian Society and a passionate defender of Victorian architecture ...

(1973)

*''So Much Blood'' – Simon Brett (1976)

*"Opus 4" – The Art of Noise

Art of Noise (also The Art of Noise) were an English avant-garde synth-pop group formed in early 1983 by engineer/producer Gary Langan and programmer J. J. Jeczalik, along with keyboardist/arranger Anne Dudley, producer Trevor Horn, and music ...

(album: '' In Visible Silence'', 1986)

*''The Piano'' – Jane Campion

Dame Elizabeth Jane Campion (born 30 April 1954) is a New Zealand filmmaker. She is best known for writing and directing the critically acclaimed films ''The Piano'' (1993) and '' The Power of the Dog'' (2021), for which she has received a tot ...

(1993)

*''Cod'' – Mark Kurlansky (1997)

*

*''Cod'' – Mark Kurlansky (199)

Works by Thomas Hood

The list of Hood's separately published works is as follows: *''Odes and Addresses to Great People'' (1825) *''Whims and Oddities'' (two series, 1826 and 1827) *''The Plea of the Midsummer Fairies, hero and Leander, Lycus the Centaur and other Poems'' (1827), his only collection of serious verse *''The Epping Hunt'' illustrated byGeorge Cruikshank

George Cruikshank (27 September 1792 – 1 February 1878) was a British caricaturist and book illustrator, praised as the "modern Hogarth" during his life. His book illustrations for his friend Charles Dickens, and many other authors, reache ...

(1829)

*''The Dream of Eugene Aram, the Murderer'' (1831)

*''Tylney Hall'', a novel (3 vols., 1834)

*''The Comic Annual'' (1830–1842)

*''Hood's Own, or, Laughter from Year to Year'' (1838, second series, 1861)

*''Up the Rhine'' (1840)

*'' Hood's Magazine and Comic Miscellany'' (1844–1848)

*''National Tales'' (2 vols., 1837), a collection of short novelettes, including " The Three Jewels".

*''Whimsicalities'' (1844), with illustrations from John Leech's designs

*Many contributions to contemporary periodicals.

References

Further reading

* John Clubbe, ''Victorian Forerunner; The Later Career of Thomas Hood'' (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1968) *Frances Hood,The Memorials of Thomas Hood – Vol. 1

' and

The Memorials of Thomas Hood – Vol. 2

' (Boston: Ticknor & Fields, 1860) *

Walter Jerrold

Walter Copeland Jerrold (3 May 1865 – 27 October 1929) was an English writer, biographer and newspaper editor.

Early life

Jerrold was born in Liverpool, the son of Thomas Serle Jerrold and Jane Matilda Copeland (who were first cousins), and on ...

, Thomas Hood; His Life and Times

' (New York: John Lane, 1909) *Alex Elliot (ed.),

Hood in Scotland

' (Dundee: James P. Matthew & Co., 1885) *J. C. Reid, ''Thomas Hood'' (New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1963)

External links

Thomas Hood

at the

Poetry Foundation

The Poetry Foundation is an American literary society that seeks to promote poetry and lyricism in the wider culture. It was formed from '' Poetry'' magazine, which it continues to publish, with a 2003 gift of $200 million from philanthropist ...

*

*

*The Poetical Works of Thomas Hood

a

The University of Adelaide Library

biography & selected writings at gerald-massey.org.uk *

"Thomas Hood"

George Saintsbury

George Edward Bateman Saintsbury, FBA (23 October 1845 – 28 January 1933), was an English critic, literary historian, editor, teacher, and wine connoisseur. He is regarded as a highly influential critic of the late 19th and early 20th centu ...

in ''Macmillan's Magazine'', Vol. LXII, May to Oct. 1890, pp. 422–430

*Flint, Joy. ''Hood, Thomas (1799–1845).'' Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, online e(accessed 26 November 2010)

* Thomas Hood Collection. General Collection, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. {{DEFAULTSORT:Hood, Thomas 1799 births 1845 deaths 19th-century English poets English essayists Victorian poets Writers from London Burials at Kensal Green Cemetery Male essayists English male poets Poets associated with Dundee