Thomas Heazle Parke on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

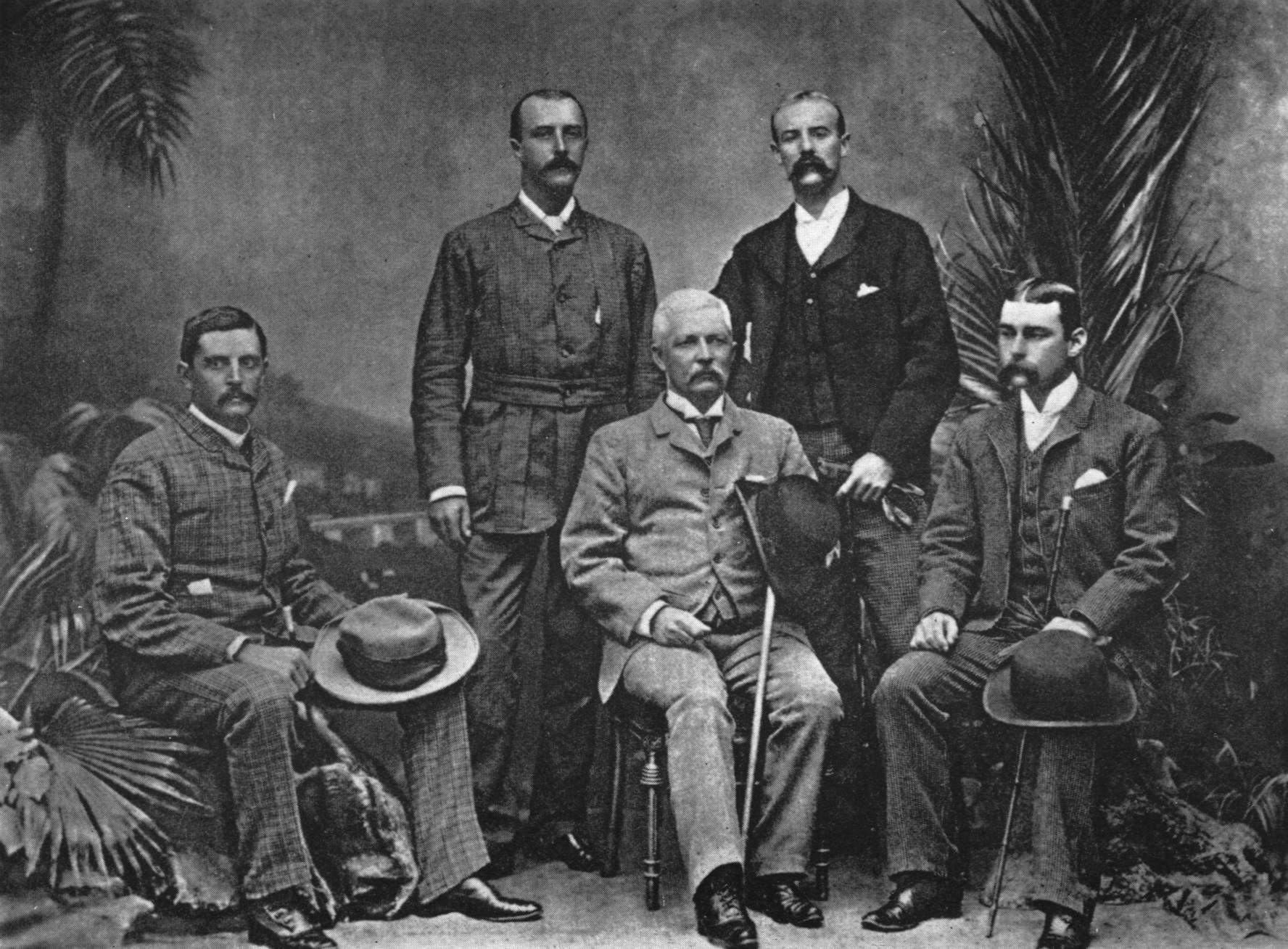

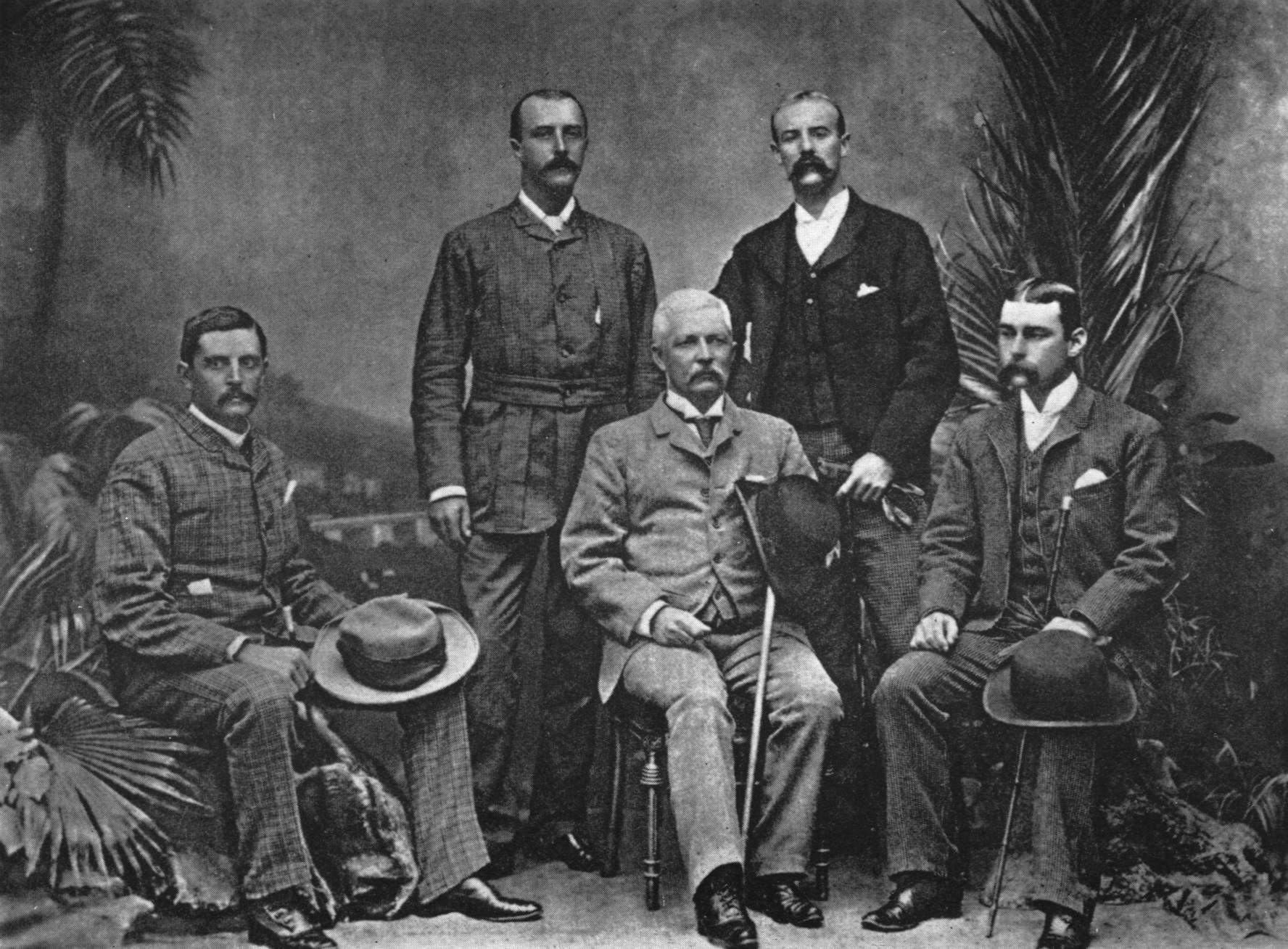

Thomas Heazle Parke (1857–1893) was an Irish physician, British Army officer and author who was known for his work as a doctor on the Emin Pasha Relief Expedition.

In January 1887, while in Alexandria, Parke was invited by

In January 1887, while in Alexandria, Parke was invited by

On the granite pedestal is a bronze plaque depicting the incident on 13 August 1887 when Parke sucked the poison from an arrow wound in the chest of Capt. William G. Stairs to save his life. He is also commemorated by a bust in the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland.

On the granite pedestal is a bronze plaque depicting the incident on 13 August 1887 when Parke sucked the poison from an arrow wound in the chest of Capt. William G. Stairs to save his life. He is also commemorated by a bust in the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland.

Some of his papers

are held at the Yale University Library

Early life

Parke was born on 27 November 1857 at Clogher House in Kilmore,County Roscommon

"Steadfast Irish heart"

, image_map = Island of Ireland location map Roscommon.svg

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state, Country

, subdivision_name = Republic of Ireland, Ireland

, subdivision_type1 = Provinces of I ...

, Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel, the Irish Sea, and St George's Channel. Ireland is the s ...

. and was brought up in Carrick-on-Shannon

Carrick-on-Shannon () is the county town of County Leitrim in Republic of Ireland, Ireland. It is the largest town in the county of Leitrim. A smaller part of the town lies in County Roscommon. The population of the town was 4,062 in 2016. It is ...

, County Leitrim. He attended the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland

The Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland (RCSI) is a medical professional and educational institution, which is also known as RCSI University of Medicine and Health Sciences, Ireland's first private university. It was established in 1784 ...

in Dublin

Dublin (; , or ) is the capital and largest city of Ireland. On a bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the province of Leinster, bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, a part of the Wicklow Mountains range. At the 2016 ...

, graduating in 1878. He became a registered medical practitioner in February 1879, working as a dispensary medical officer in Ballybay

Ballybay () is a town and civil parish in County Monaghan, Ireland. The town is centred on the crossroads of the R183 and R162 regional roads.

Geography

The town is the meeting point for roads going to Monaghan, Castleblayney, Carrickmac ...

, and then as a surgeon in Bath, Somerset

Bath () is a city in the Bath and North East Somerset unitary area in the county of Somerset, England, known for and named after its Roman-built baths. At the 2021 Census, the population was 101,557. Bath is in the valley of the River Avon, ...

.

Military career

Parke joined the BritishArmy Medical Services

The Army Medical Services (AMS) is the organisation responsible for administering the corps that deliver medical, veterinary, dental and nursing services in the British Army. It is headquartered at the former Staff College, Camberley, near the ...

in February 1881 as a surgeon, first serving in Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning the North Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via a land bridg ...

during the final stages of the ʻUrabi revolt

The ʻUrabi revolt, also known as the ʻUrabi Revolution ( ar, الثورة العرابية), was a nationalist uprising in Egypt from 1879 to 1882. It was led by and named for Colonel Ahmed ʻUrabi (also spelled Orabi and Arabi) and sought to d ...

in 1882. As a senior medical officer at a field hospital near Cairo

Cairo ( ; ar, القاهرة, al-Qāhirah, ) is the capital of Egypt and its largest city, home to 10 million people. It is also part of the largest urban agglomeration in Africa, the Arab world and the Middle East: The Greater Cairo metr ...

, Parke was responsible for treating battle casualties as well as the deadly cholera epidemic

Seven cholera pandemics have occurred in the past 200 years, with the first pandemic originating in India in 1817. The seventh cholera pandemic is officially a current pandemic and has been ongoing since 1961, according to a World Health Organizat ...

that afflicted 20% of British troops stationed there. In late 1883, Parke returned to Ireland, where he was stationed at Dundalk

Dundalk ( ; ga, Dún Dealgan ), meaning "the fort of Dealgan", is the county town (the administrative centre) of County Louth, Ireland. The town is on the Castletown River, which flows into Dundalk Bay on the east coast of Ireland. It is h ...

with the 16th The Queen's Lancers

The 16th The Queen's Lancers was a cavalry regiment of the British Army, first raised in 1759. It saw service for two centuries, before being amalgamated with the 5th Royal Irish Lancers to form the 16th/5th Lancers in 1922.

History

Early wars

...

. He arrived in Egypt once again in 1884 as a part of the Nile Expedition

The Nile Expedition, sometimes called the Gordon Relief Expedition (1884–85), was a British mission to relieve Major-General Charles George Gordon at Khartoum, Sudan. Gordon had been sent to the Sudan to help Egyptians evacuate from Sudan ...

sent in relief of General Charles Gordon, who was besieged in Khartoum by Mahdists in neighbouring Sudan. The expedition arrived too late and Gordon was killed; Parke would later negatively recount this experience in an 1892 journal article titled ''How General Gordon Was Really Lost.'' Following the expedition, Parke spent the next few years stationed in Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandri ...

, where he notably introduced fox hunting to Egypt, becoming master of the Alexandria Hunt Club.

Emin Pasha Relief Expedition

In January 1887, while in Alexandria, Parke was invited by

In January 1887, while in Alexandria, Parke was invited by Edmund Musgrave Barttelot

Edmund Musgrave Barttelot (28 March 1859 – 19 July 1888) was a British army officer, who became notorious after his allegedly brutal and deranged behaviour during his disastrous command of the rear column in the Congo during Henry Morton St ...

to accompany him on the Emin Pasha Relief Expedition. The expedition would be led by Henry Morton Stanley

Sir Henry Morton Stanley (born John Rowlands; 28 January 1841 – 10 May 1904) was a Welsh-American explorer, journalist, soldier, colonial administrator, author and politician who was famous for his exploration of Central Africa and his sear ...

, and would journey through the African wilderness in relief of Emin Pasha

185px, Schnitzer in 1875

Mehmed Emin Pasha (born Isaak Eduard Schnitzer, baptized Eduard Carl Oscar Theodor Schnitzer; March 28, 1840 – October 23, 1892) was an Ottoman physician of German Jewish origin, naturalist, and governor of the Egyp ...

, an Egyptian administrator who had been cut off by Mahdist forces following the Siege of Khartoum. Parke was initially rejected by Stanley upon his arrival in Alexandria, but was invited by telegram a day later to join the expedition in Cairo. On 25 February 1887, the expedition set off from Zanzibar

Zanzibar (; ; ) is an insular semi-autonomous province which united with Tanganyika in 1964 to form the United Republic of Tanzania. It is an archipelago in the Indian Ocean, off the coast of the mainland, and consists of many small islan ...

in the east for the Congo in the east.

The expedition lasted for three years and faced great difficulty, with the expedition of 812 men suffering from poor logistical planning and leadership. The rainforest was much larger than Stanley expected, leading much of the party to face starvation and disease. The expedition had to resort to looting native villages for food, escalating the conflict between the two groups. Parke, for his part, saved the lives of many in the party, including Stanley, who suffered from acute abdominal pain

Abdominal pain, also known as a stomach ache, is a symptom associated with both non-serious and serious medical issues.

Common causes of pain in the abdomen include gastroenteritis and irritable bowel syndrome. About 15% of people have a m ...

and a bout of sepsis

Sepsis, formerly known as septicemia (septicaemia in British English) or blood poisoning, is a life-threatening condition that arises when the body's response to infection causes injury to its own tissues and organs. This initial stage is follo ...

. Stanley described Parke's care as "ever striving, patient, cheerful and gentle…most assiduous in his application to my needs, and gentle as a woman in his ministrations". Parke also treated Arthur Jephson for fever

Fever, also referred to as pyrexia, is defined as having a temperature above the normal range due to an increase in the body's temperature set point. There is not a single agreed-upon upper limit for normal temperature with sources using val ...

, and nursed Robert H. Nelson through starvation. Furthermore, after a conflict with the natives, Parke had to save William Grant Stairs

William Grant Stairs (1 July 1863 – 9 June 1892) was a Canadian-British explorer, soldier, and adventurer who had a leading role in two of the most controversial expeditions in the Scramble for Africa.

Education

Born in Halifax, Nova Scotia, ...

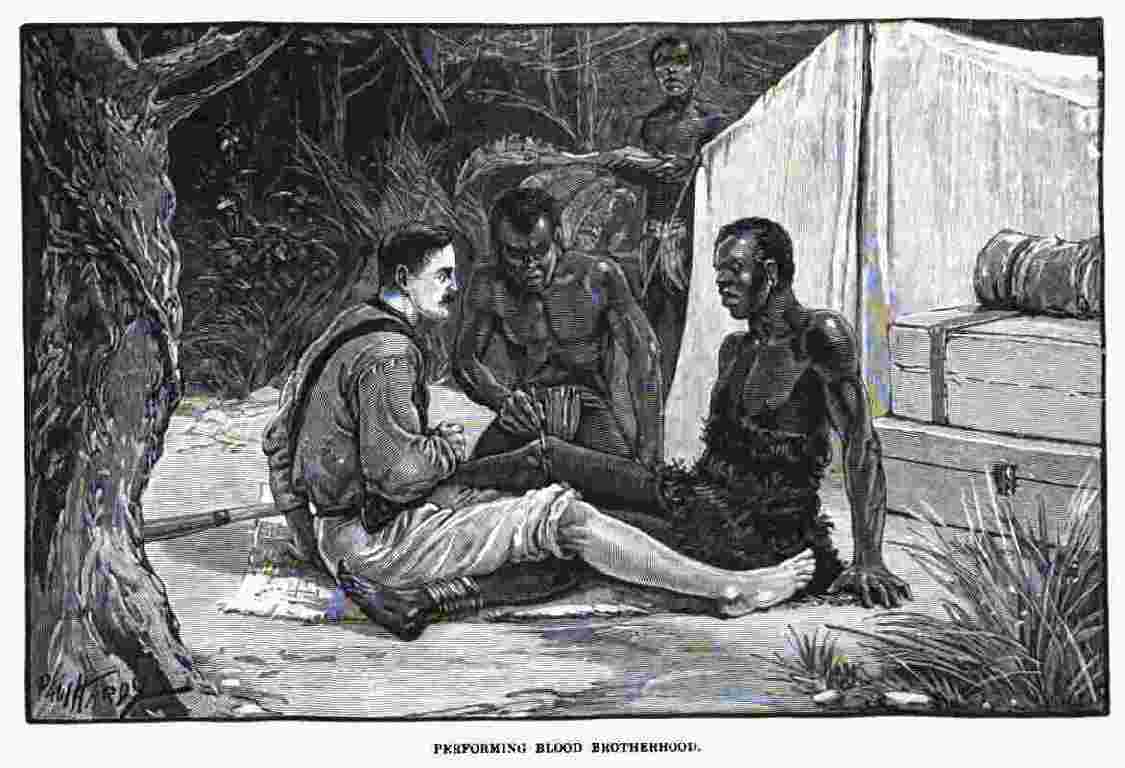

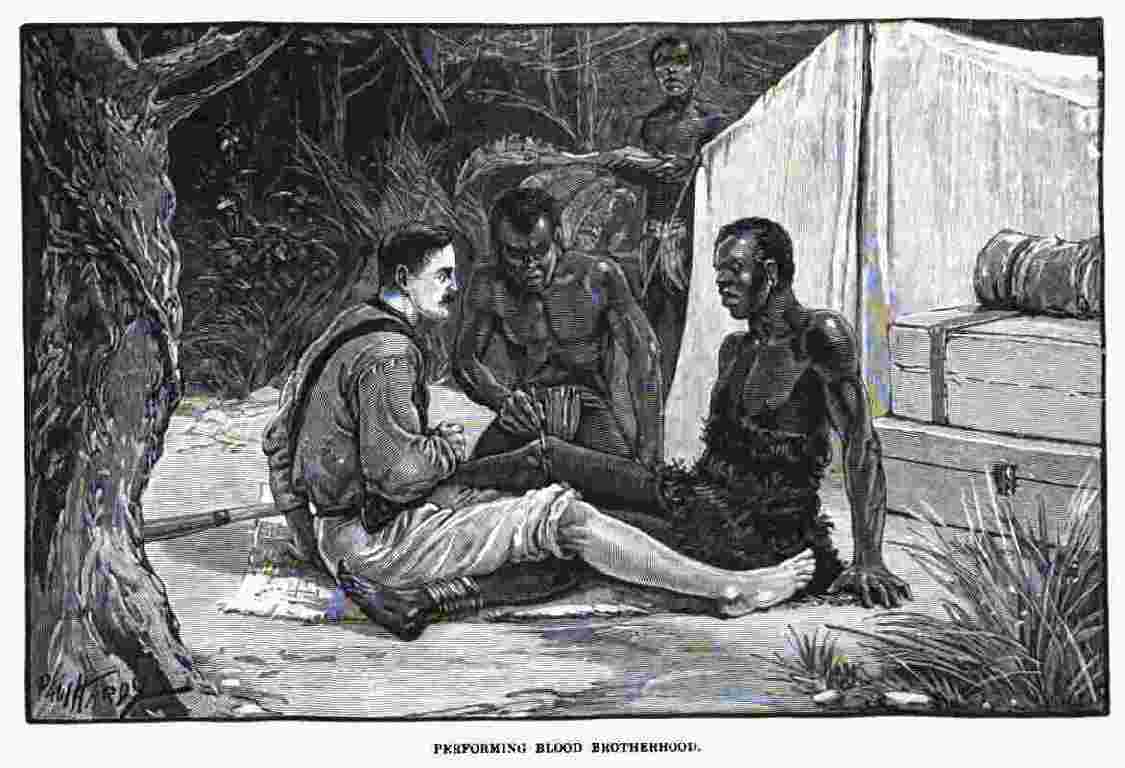

by orally sucking the poison out of an arrow wound.

During the expedition, Parke purchased from an Arab slaver a Mangbetu Pigmy girl, who would serve his nurse and servant for over a year.

Later life

After returning to Ireland, Parke received an Honorary Fellowship of theRoyal College of Surgeons in Ireland

The Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland (RCSI) is a medical professional and educational institution, which is also known as RCSI University of Medicine and Health Sciences, Ireland's first private university. It was established in 1784 ...

and was awarded gold medals from the British Medical Association

The British Medical Association (BMA) is a registered trade union for doctors in the United Kingdom. The association does not regulate or certify doctors, a responsibility which lies with the General Medical Council. The association's headqua ...

and the Royal Geographical Society

The Royal Geographical Society (with the Institute of British Geographers), often shortened to RGS, is a learned society and professional body for geography based in the United Kingdom. Founded in 1830 for the advancement of geographical scien ...

. He published several books, including ''My Personal Experiences in Equatorial Africa'' (published in 1891) and ''A Guide to Health in Africa''.

In August 1893, Parke visited William Beauclerk, 10th Duke of St Albans

William Amelius Aubrey de Vere Beauclerk, 10th Duke of St Albans, PC DL (15 April 1840 – 10 May 1898), styled Earl of Burford until 1849, was a British Liberal parliamentarian of the Victorian era.

The Duke served in William Gladstone's ...

in Ardrishaig

Ardrishaig ( gd, Àird Driseig) is a coastal village on Loch Gilp, at the southern (eastern) entrance to the Crinan Canal in Argyll and Bute in the west of Scotland. It lies immediately to the south of Lochgilphead, with the nearest larger to ...

, Scotland. He died during that visit on 11 August 1893, presumably due to a seizure. His coffin was brought back to Ireland, where he received a military funeral as it passed from the Dublin docks to Broadstone railway station

Broadstone railway station ( ga, Stáisiún An Clocháin Leathan) was the Dublin terminus of the Midland Great Western Railway (MGWR), located in the Dublin suburb of Broadstone. The site also contained the MGWR railway works and a steam ...

. Parke was buried near his birthplace in Drumsna

Drumsna ( which translates as ''the ridge of the swimming place'') is a village in County Leitrim, Ireland. It is situated 6 km east of Carrick-on-Shannon on the River Shannon and is located off the N4 National primary route which lin ...

, County Roscommon.

Honours

A bronze statue of Parke stands onMerrion Street

Merrion Street (; ) is a major Georgian street on the southside of Dublin, Ireland, which runs along one side of Merrion Square. It is divided into Merrion Street Lower (north end), Merrion Square West and Merrion Street Upper (south end). It ...

in Dublin

Dublin (; , or ) is the capital and largest city of Ireland. On a bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the province of Leinster, bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, a part of the Wicklow Mountains range. At the 2016 ...

, outside the Natural History Museum

A natural history museum or museum of natural history is a scientific institution with natural history collections that include current and historical records of animals, plants, fungi, ecosystems, geology, paleontology, climatology, and more. ...

.  On the granite pedestal is a bronze plaque depicting the incident on 13 August 1887 when Parke sucked the poison from an arrow wound in the chest of Capt. William G. Stairs to save his life. He is also commemorated by a bust in the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland.

On the granite pedestal is a bronze plaque depicting the incident on 13 August 1887 when Parke sucked the poison from an arrow wound in the chest of Capt. William G. Stairs to save his life. He is also commemorated by a bust in the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland.

References

* * * Lyons, J. B. ''Surgeon Major Parke's African journey 1887-89.'' The Lilliput Press, Dublin. 1994.Some of his papers

are held at the Yale University Library

External links

* * Thomas Heazle Parke Papers (MS 1643). Manuscripts and Archives, Yale University Library. {{DEFAULTSORT:Parke, Thomas Heazle 1857 births 1893 deaths 19th-century Irish people Irish naturalists Irish scientists British Army personnel of the Mahdist War People from County Leitrim Royal Army Medical Corps officers Irish officers in the British Army Irish explorers Fellows of the Royal Scottish Geographical Society