Thomas Forsaith on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Thomas Spencer Forsaith, JP (18 July 1814 – 29 November 1898), was a New Zealand politician and an

In 1862, Forsaith entered the services of the church. Since 1850, he had belonged to the

In 1862, Forsaith entered the services of the church. Since 1850, he had belonged to the  In 1867, Forsaith accepted an invitation for a pastorate at Woollahra. His health had suffered over the winter, and apparently he hoped for an improvement in the warmer climate. He left New Zealand on board the ''Parisian'' on 23 September 1867. In 1868, he moved to

In 1867, Forsaith accepted an invitation for a pastorate at Woollahra. His health had suffered over the winter, and apparently he hoped for an improvement in the warmer climate. He left New Zealand on board the ''Parisian'' on 23 September 1867. In 1868, he moved to

Auckland

Auckland (pronounced ) ( mi, Tāmaki Makaurau) is a large metropolitan city in the North Island of New Zealand. The most populous urban area in the country and the fifth largest city in Oceania, Auckland has an urban population of about ...

draper. According to some historians, he was the country's second premier

Premier is a title for the head of government in central governments, state governments and local governments of some countries. A second in command to a premier is designated as a deputy premier.

A premier will normally be a head of gov ...

, although a more conventional view states that neither he nor his predecessor ( James FitzGerald) should properly be given that title.

Early life

Forsaith was born inLondon, England

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a ma ...

on 18 July 1814 to Samuel Forsaith (1776–1832) and Elizabeth Forsaith née Emberson (1782–1844). His father was a linen draper

Draper was originally a term for a retailer or wholesaler of cloth that was mainly for clothing. A draper may additionally operate as a cloth merchant or a haberdasher.

History

Drapers were an important trade guild during the medieval perio ...

and haberdasher

In British English, a haberdasher is a business or person who sells small articles for sewing, dressmaking and knitting, such as buttons, ribbons, and zippers; in the United States, the term refers instead to a retailer who sells men's clothin ...

. His parents belonged to the Congregational church

Congregational churches (also Congregationalist churches or Congregationalism) are Protestant churches in the Calvinist tradition practising congregationalist church governance, in which each congregation independently and autonomously runs i ...

.

His father's first marriage was to Elizabeth Smyth (1771 – 23 September 1809). They had five children:

* Sarah Smyth Forsaith (4 August 1801 – 26 April 1854)

* Samuel Smyth Forsaith (21 January 1803 – 1 April 1894)

* John Smyth Forsaith (8 October 1804 – 31 July 1883)

* Elizabeth Smyth Forsaith (21 May 1806 – 12 August 1809)

* Mary Smyth Forsaith (19 February 1808 – 3 June 1845)

Of those, Samuel emigrated to New Zealand, arriving in Auckland

Auckland (pronounced ) ( mi, Tāmaki Makaurau) is a large metropolitan city in the North Island of New Zealand. The most populous urban area in the country and the fifth largest city in Oceania, Auckland has an urban population of about ...

prior to May 1851. He died in Thames

The River Thames ( ), known alternatively in parts as the River Isis, is a river that flows through southern England including London. At , it is the longest river entirely in England and the second-longest in the United Kingdom, after the ...

in 1894.

After his first wife's death in September 1809, Samuel Forsaith married Elizabeth née Emberson on 4 October 1810. They had nine children:

* Elizabeth Forsaith (10 July 1811 – 2 July 1841)

* Thomas Forsaith (7 December 1812 – 16 February 1813)

* Thomas Spencer Forsaith (18 July 1814 – 29 November 1898)

* Hannah Forsaith (1 March 1816 – 2 May 1819)

* Phebe Forsaith (6 July 1817 – 6 February 1819)

* David Forsaith (21 June 1819 – 5 September 1819)

* Robert Forsaith (11 July 1820 – 23 May 1883)

* Josiah Forsaith (29 April 1822 – 8 May 1883)

* Hephzibah Forsaith (24 July 1824 – 21 December 1897)

Apart from Thomas Spencer Forsaith, his sister Hephzibah also emigrated to New Zealand; in 1847 on the''Elora''. All other siblings and his parents remained in England.

Thomas Forsaith became an apprentice as a silk merchant in Croydon

Croydon is a large town in south London, England, south of Charing Cross. Part of the London Borough of Croydon, a local government district of Greater London. It is one of the largest commercial districts in Greater London, with an extensive ...

, but he rather wanted to go to sea. As a cabin boy, he travelled on a collier to the River Tyne

The River Tyne is a river in North East England. Its length (excluding tributaries) is . It is formed by the North Tyne and the South Tyne, which converge at Warden Rock near Hexham in Northumberland at a place dubbed 'The Meeting of the Wate ...

. He then made three journeys to the West Indies

The West Indies is a subregion of North America, surrounded by the North Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea that includes 13 independent island countries and 18 dependencies and other territories in three major archipelagos: the Grea ...

as a cadet officer for Charles Horsfall and Co. on the ''Huddersfield'' (named after Horsfall's birthplace). He returned home with a good reference, but found that his father had died in the meantime. As a fourth officer, he sailed on the convict ship

A convict ship was any ship engaged on a voyage to carry convicted felons under sentence of penal transportation from their place of conviction to their place of exile.

Description

A convict ship, as used to convey convicts to the British colon ...

''Hoogley'' to Botany Bay

Botany Bay (Dharawal: ''Kamay''), an open oceanic embayment, is located in Sydney, New South Wales, Australia, south of the Sydney central business district. Its source is the confluence of the Georges River at Taren Point and the Cooks R ...

in 1834. Two years later, he again sailed to Australia, this time on the ''Lord Goderich''. He first came to New Zealand on the return journey, when Kauri

''Agathis'', commonly known as kauri or dammara, is a genus of 22 species of evergreen tree. The genus is part of the ancient conifer family Araucariaceae, a group once widespread during the Jurassic and Cretaceous periods, but now largely re ...

spars were loaded in Hokianga.

Forsaith was married on 17 May 1838 at the Congregational Church in Old Broad Street, London to Elizabeth Mary, a daughter of Robert Clements of Hoxton

Hoxton is an area in the London Borough of Hackney, England. As a part of Shoreditch, it is often considered to be part of the East End – the historic core of wider East London. It was historically in the county of Middlesex until 1889. It l ...

. Their wedding was one of the first in a dissenting church that was legalised. They decided to emigrate to New Zealand and Forsaith took woodworking machinery and trading goods with them on the ''Coromandel'' later in 1838.

Early life in New Zealand

Forsaith established himself as a farmer and trader in theKaipara District

The Kaipara District is located in the Northland Region in northern New Zealand.

History

Kaipara District was formed through the 1989 New Zealand local government reforms and was constituted on 1 November 1989. It was made up of five former bor ...

. He bought land in 1839 on the Wairoa River near present-day Dargaville

Dargaville ( mi, Takiwira) is a town located in the North Island of New Zealand. It is situated on the bank of the Northern Wairoa River in the Kaipara District of the Northland region. The town is located 55 kilometres southwest of Whangāre ...

. He was likely to have been the first European settler in the area. He built a timber mill for cutting Kauri spars, as the British Government was purchasing these at £17 each. He cleared land for wheat and running cattle, which he had to import. By May 1841, he had fenced 12 acres of cleared land, most of it growing wheat.

While the Forsaiths were visiting Sydney in February 1842, the discovery of a Māori skull on their property caused serious trouble, as Māori chiefs including Te Tirarau Kukupa claimed a tapu and ransacked the station as utu. An upset Forsaith asked the Governor

A governor is an administrative leader and head of a polity or political region, ranking under the head of state and in some cases, such as governors-general, as the head of state's official representative. Depending on the type of political ...

(William Hobson

Captain William Hobson (26 September 1792 – 10 September 1842) was a British Royal Navy officer who served as the first Governor of New Zealand. He was a co-author of the Treaty of Waitangi.

Hobson was dispatched from London in July 1 ...

) for compensation, who sent the Protector of Aborigines, George Clarke

George Clarke (7 May 1661 – 22 October 1736), of All Souls, Oxford, was an English architect, print collector and Tory politician who sat in the English and British House of Commons between 1702 and 1736.

Life

The son of Sir William Clarke, ...

, to investigate. Forsaith was cleared of any wrongdoing, and the Māori chiefs settled by giving him a block of land of . Forsaith, still unsettled by the incident, swapped his land holding with another nearer Auckland

Auckland (pronounced ) ( mi, Tāmaki Makaurau) is a large metropolitan city in the North Island of New Zealand. The most populous urban area in the country and the fifth largest city in Oceania, Auckland has an urban population of about ...

. Clarke, who had held his role since April 1840, had not visited the Kaipa District before and made recommendations for a magistracy there.

On 30 October 1843, Charlotte Clements Forsaith was born in Auckland; she was their only child. She was baptised on 5 December that year. She married Thomas Morell MacDonald at her father's residence in Khyber Pass Road, Auckland, on 7 January 1862. Their grandson Tom Macdonald (1898–1980) was a New Zealand Member of Parliament

A member of parliament (MP) is the representative in parliament of the people who live in their electoral district. In many countries with bicameral parliaments, this term refers only to members of the lower house since upper house members of ...

for over 20 years. Charlotte died on 12 December 1894 in Invercargill.

Protectorate Department

Hobson, impressed by Forsaith's command of theMāori language

Māori (), or ('the Māori language'), also known as ('the language'), is an Eastern Polynesian language spoken by the Māori people, the indigenous population of mainland New Zealand. Closely related to Cook Islands Māori, Tuamotuan, an ...

and his knowledge of their customs, offered him the role of Sub-protector of Aborigines, which he accepted. Forsaith was thus reporting to Clarke. They were working in the Protectorate Department created by Hobson, following instructions from the British secretary of state for the colonies. The department's role was "to watch over the interests of the Aborigines as their protector" and had religious, social and intellectual aspects. It was also given a second role, which conflicted with the first; since the Treaty of Waitangi, the Crown was the sole purchaser of Māori land, and the department's role was to action the purchases. Clarke managed to persuade Hobson to free him of the land purchase role, but it remained within the scope of the Sub-protectors.

In 1843, Forsaith was promoted to Protector in succession of Clarke. Forsaith worked closely with the second Governor, Robert FitzRoy

Vice-Admiral Robert FitzRoy (5 July 1805 – 30 April 1865) was an English officer of the Royal Navy and a scientist. He achieved lasting fame as the captain of during Charles Darwin's famous voyage, FitzRoy's second expedition to Tierra ...

. They travelled in the Cook Strait

Cook Strait ( mi, Te Moana-o-Raukawa) separates the North and South Islands of New Zealand. The strait connects the Tasman Sea on the northwest with the South Pacific Ocean on the southeast. It is wide at its narrowest point,McLintock, A H, ...

area in 1844, and to the Māori meeting at Waikanae following the Wairau Affray

The Wairau Affray of 17 June 1843, also called the Wairau Massacre in older histories, was the first serious clash of arms between British settlers and Māori in New Zealand after the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi and the only one to take ...

near Tuamarina

Tuamarina (often spelled Tua Marina) is a small town in Marlborough, New Zealand. State Highway 1 runs through the area. The Tuamarina River joins the Wairau River just south of the settlement. Picton is about 18 km to the north, and Ble ...

, the first serious clash of arms between Māori and colonists. Forsaith was then stationed in Wellington

Wellington ( mi, Te Whanganui-a-Tara or ) is the capital city of New Zealand. It is located at the south-western tip of the North Island, between Cook Strait and the Remutaka Range. Wellington is the second-largest city in New Zealand by me ...

and witnessed the Te Aro

Te Aro (formerly also known as Te Aro Flat) is an inner-city suburb of Wellington, New Zealand. It comprises the southern part of the central business district including the majority of the city's entertainment district and covers the mostly fla ...

land purchase in February 1844. He negotiated with Te Rangihaeata about the evacuation of land in the Hutt Valley

The Hutt Valley (or 'The Hutt') is the large area of fairly flat land in the Hutt River valley in the Wellington region of New Zealand. Like the river that flows through it, it takes its name from Sir William Hutt, a director of the New Zeala ...

, but the actions of the New Zealand Company

The New Zealand Company, chartered in the United Kingdom, was a company that existed in the first half of the 19th century on a business model focused on the systematic colonisation of New Zealand. The company was formed to carry out the principl ...

and the impatience of the settlers to move onto disputed land resulted in the Hutt Valley campaign. He acted as interpreter for Mathew Richmond, the Government Superintendent for the Southern District, and Bishop Selwyn, the first Anglican Bishop of New Zealand. When the influential chief Te Rauparaha

Te Rauparaha (c.1768 – 27 November 1849) was a Māori rangatira (chief) and war leader of the Ngāti Toa tribe who took a leading part in the Musket Wars, receiving the nickname "the Napoleon of the South". He was influential in the origina ...

visited Wellington in 1845, he was shown around by Forsaith.

In 1846, the department was abolished by the next Governor, George Grey

Sir George Grey, KCB (14 April 1812 – 19 September 1898) was a British soldier, explorer, colonial administrator and writer. He served in a succession of governing positions: Governor of South Australia, twice Governor of New Zealand, Gov ...

, as he wanted to have influence over Māori issues himself. Grey appointed a Native Secretary instead. Forsaith left Government employment in the following year.

Business interests

Forsaith opened a drapery store in Auckland's Queen Street. He had this business from 1847 to 1862. He also edited the '' Daily Southern Cross'' newspaper for a while. He became aJustice of the peace

A justice of the peace (JP) is a judicial officer of a lower or '' puisne'' court, elected or appointed by means of a commission (letters patent) to keep the peace. In past centuries the term commissioner of the peace was often used with the sa ...

in 1857.

Political career

New Ulster Council

The Proclamation of 1852 stipulated that the New Ulster Legislative Council, which had been in place since 1848, was to have twelve elected and six nominated members. Forsaith was asked by a group of electors to become a candidate. Elections in the Northern Division District were held on 31 August 1852, and Allan O'Neill (fromBayswater

Bayswater is an area within the City of Westminster in West London. It is a built-up district with a population density of 17,500 per square kilometre, and is located between Kensington Gardens to the south, Paddington to the north-east, and ...

) and Forsaith were returned. The council had not met by the time the New Zealand Constitution Act 1852

The New Zealand Constitution Act 1852 (15 & 16 Vict. c. 72) was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom that granted self-government to the Colony of New Zealand. It was the second such Act, the previous 1846 Act not having been fully i ...

arrived, which resulted in the abolition of New Ulster and New Munster provinces and their replacement with new provincial governments and established, a bicameral New Zealand Parliament

The New Zealand Parliament ( mi, Pāremata Aotearoa) is the unicameral legislature of New Zealand, consisting of the King of New Zealand (King-in-Parliament) and the New Zealand House of Representatives. The King is usually represented by h ...

, consisting of the General Assembly

A general assembly or general meeting is a meeting of all the members of an organization or shareholders of a company.

Specific examples of general assembly include:

Churches

* General Assembly (presbyterian church), the highest court of presby ...

, the Governor, and a legislative council.

Parliament

Forsaith once again stood for election and he and Walter Lee were returned on 23 August 1853 to the 1st New Zealand Parliament as representatives of the Northern Division electorate, which covered the area north ofAuckland

Auckland (pronounced ) ( mi, Tāmaki Makaurau) is a large metropolitan city in the North Island of New Zealand. The most populous urban area in the country and the fifth largest city in Oceania, Auckland has an urban population of about ...

but south of Whangarei.

The Fitzgerald Executive was the first Executive Council under the 1852 Constitution led by James FitzGerald. When it became clear that the first ministers had no power, they resigned as the Executive after seven weeks on 2 August 1854. Robert Wynyard, the administrator filling in after Grey's departure and before the arrival of the next Governor, Colonel Thomas Gore Browne

Colonel Sir Thomas Robert Gore Browne, (3 July 1807 – 17 April 1887) was a British colonial administrator, who was Governor of St Helena, Governor of New Zealand, Governor of Tasmania and Governor of Bermuda.

Early life

Browne was born on ...

prorogued

A legislative session is the period of time in which a legislature, in both parliamentary and presidential systems, is convened for purpose of lawmaking, usually being one of two or more smaller divisions of the entire time between two elections ...

Parliament as the members refused to accept his claim that responsible government was not possible without royal assent, which had not been given. In the second session of the 1st Parliament, Forsaith, as a member of the minority which supported Wynyard, was appointed by Wynyard to lead an Executive. The other members of this Executive were Jerningham Wakefield, William Travers and James Macandrew

James Macandrew (1819(?) – 25 February 1887) was a New Zealand ship-owner and politician. He served as a Member of Parliament from 1853 to 1887 and as the last Superintendent of Otago Province.

Early life

Macandrew was born in Scotland, pro ...

. This appointed Cabinet did not have the confidence of Parliament and lasted only from 31 August to 2 September 1854. Forsaith's Ministry is the shortest in New Zealand's parliamentary history.

When Browne arrived, he announced that self-government would begin with the 2nd New Zealand Parliament. No new Cabinet was formed before then, but when it did, responsible government

Responsible government is a conception of a system of government that embodies the principle of parliamentary accountability, the foundation of the Westminster system of parliamentary democracy. Governments (the equivalent of the executive b ...

was obtained under the Sewell Ministry led by Henry Sewell

Henry Sewell (7 September 1807 – 14 May 1879) was a prominent 19th-century New Zealand politician. He was a notable campaigner for New Zealand self-government, and is generally regarded as having been the country's first premier (an office th ...

.

In the 1855 general election, Northern Division was contested by four candidates. The two incumbents, Forsaith and Lee, stood against Thomas Henderson and Joseph May (who would later become a prominent member of the Auckland Provincial Council). They received 292, 294, 363 and 213 votes, respectively. Henderson and Lee were thus declared elected, and Forsaith was beaten by two votes.

Forsaith and Reader Wood contested a vacancy in the City of Auckland electorate. The nomination meeting on 26 April 1858 sparked little interest. A show of hands was in favour of Forsaith, and Wood called for a poll. The election was held the next day and Forsaith was elected. Parliament at the time was in session, and he took the oath on 28 April, being welcomed back by the speaker.

Wiremu Kīngi

Wiremu Kīngi Te Rangitāke (c. 1795 – 13 January 1882), Māori Chief of the Te Āti Awa Tribe, was leader of the Māori forces in the First Taranaki War.

He was born in 1795-1800 in Manukorihi pa, near Waitara. He was one of the 3 sons ...

, the paramount chief of Te Āti Awa

Te Āti Awa is a Māori iwi with traditional bases in the Taranaki and Wellington regions of New Zealand. Approximately 17,000 people registered their affiliation to Te Āti Awa in 2001, with around 10,000 in Taranaki, 2,000 in Wellington and aro ...

, refused to sell land to the government. When Te Teira, one of the minor chiefs of the tribe, agreed to sell land, many missionaries and a previous Chief Justice, William Martin, warned that the purchase was illegal. The events resulted in the First Taranaki War

The First Taranaki War (also known as the North Taranaki War) was an armed conflict over land ownership and sovereignty that took place between Māori people, Māori and the New Zealand government in the Taranaki district of New Zealand's North ...

. Forsaith supported

Kingi in Parliament and made himself deeply unpopular, which effectively ended his political career. He retired at the end of the 2nd Parliament.

Forsaith was a deeply religious person, and he gave religious lectures to the public while he was a member of parliament. During his time in the 1st Parliament, he tried to secure religious toleration. He successfully defeated Hugh Carleton

Hugh Francis Carleton (3 July 1810 – 14 July 1890) was New Zealand's first member of parliament.

Early life

Carleton was born in 1810. He was the son of Francis Carleton (1780–1870) and Charlotte Margaretta Molyneux-Montgomerie (d. 1874). ...

's motion of having Bishop Selwyn's salary paid by the Government, thus preventing the Anglican Church

Anglicanism is a Western Christian tradition that has developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the context of the Protestant Reformation in Europe. It is one of t ...

from becoming the one religion endorsed by the state.

Services to the church

In 1862, Forsaith entered the services of the church. Since 1850, he had belonged to the

In 1862, Forsaith entered the services of the church. Since 1850, he had belonged to the Presbyterian Church

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their na ...

. In early 1865, he was considered to become a minister at the gold fields in Tuapeka, but the Presbytery in Dunedin voted against licensing him, as he hadn't completed his studies yet. The view was held that a "minister of the Gospel should be able to read at least the New Testament

The New Testament grc, Ἡ Καινὴ Διαθήκη, transl. ; la, Novum Testamentum. (NT) is the second division of the Christian biblical canon. It discusses the teachings and person of Jesus, as well as events in first-century Chris ...

in the original reek

Reek may refer to:

Places

* Reek, Netherlands, a village in the Dutch province of North Brabant

* Croagh Patrick, a mountain in the west of Ireland nicknamed "The Reek"

People

* Nikolai Reek (1890-1942), Estonian military commander

* Salme Ree ...

text". Instead, Forsaith was offered a missionary post to the gold fields, which he declined. In July of that year, he was instead ordained as a pastor at the new Congregational Church at Port Chalmers

Port Chalmers is a town serving as the main port of the city of Dunedin, New Zealand. Port Chalmers lies ten kilometres inside Otago Harbour, some 15 kilometres northeast of Dunedin's city centre.

History

Early Māori settlement

The origi ...

.

In 1867, Forsaith accepted an invitation for a pastorate at Woollahra. His health had suffered over the winter, and apparently he hoped for an improvement in the warmer climate. He left New Zealand on board the ''Parisian'' on 23 September 1867. In 1868, he moved to

In 1867, Forsaith accepted an invitation for a pastorate at Woollahra. His health had suffered over the winter, and apparently he hoped for an improvement in the warmer climate. He left New Zealand on board the ''Parisian'' on 23 September 1867. In 1868, he moved to Parramatta

Parramatta () is a suburb and major commercial centre in Greater Western Sydney, located in the state of New South Wales, Australia. It is located approximately west of the Sydney central business district on the banks of the Parramatta Rive ...

, where he initially held services in the School of Arts. A church was built for the community, which opened on 19 May 1872. Also in 1872, Forsaith became chairman of the Congregational Union of New South Wales. In 1874, he acquired ''Morton House'' in Melville St, Parramatta, the house of the solicitor John Morton Gould, father of Albert Gould

Sir Albert John Gould, VD (12 February 1847 – 27 July 1936) was an Australian politician and solicitor who served as the second president of the Australian Senate.

A solicitor, businessman and citizen soldier before his entry into politics, ...

. ''Morton House'' remained the principal family residence for the rest of his life.

In 1878, he became resident chaplain at Camden College, a theological college

A seminary, school of theology, theological seminary, or divinity school is an educational institution for educating students (sometimes called ''seminarians'') in scripture, theology, generally to prepare them for ordination to serve as clergy, ...

founded in 1864. From there, he initiated a branch mission at Haslam's Creek, but moved back to Parramatta in 1882.

Subsequent to this, a period of travel started. He went to New Zealand (he left Melbourne for New Zealand in March 1882 on the ''Rotomahana''), America, Canada and Europe, including lecture series in Britain (which attracted many new immigrants to New Zealand) and officiating at the Presbyterian Church in Venice

Venice ( ; it, Venezia ; vec, Venesia or ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto region. It is built on a group of 118 small islands that are separated by canals and linked by over 400 bridges. The isl ...

. He returned to Melbourne from Britain in April 1884 on the ''Berengaria''. He then relieved at churches in Australia, Dunedin and Invercargill

Invercargill ( , mi, Waihōpai is the southernmost and westernmost city in New Zealand, and one of the southernmost cities in the world. It is the commercial centre of the Southland region. The city lies in the heart of the wide expanse of ...

.

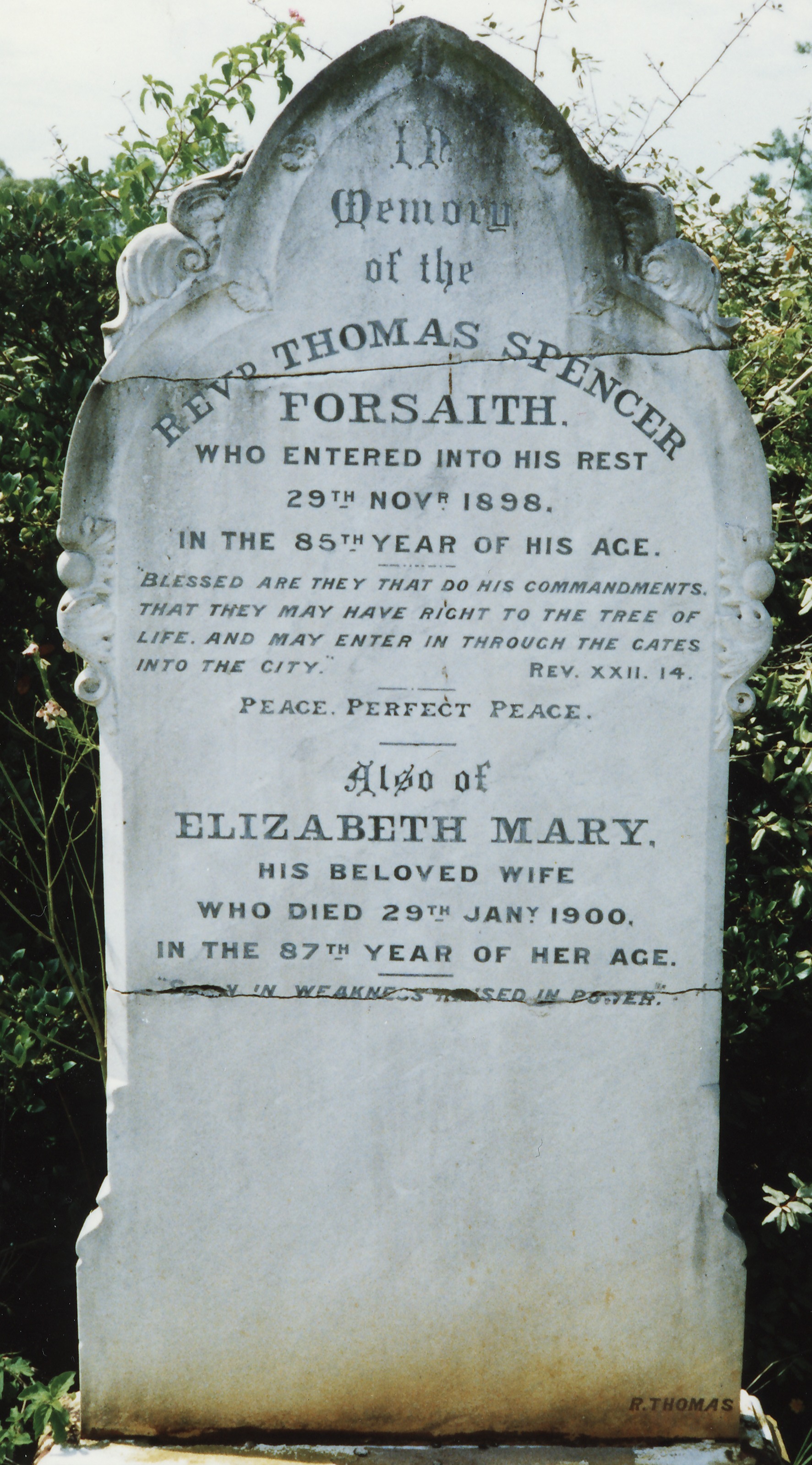

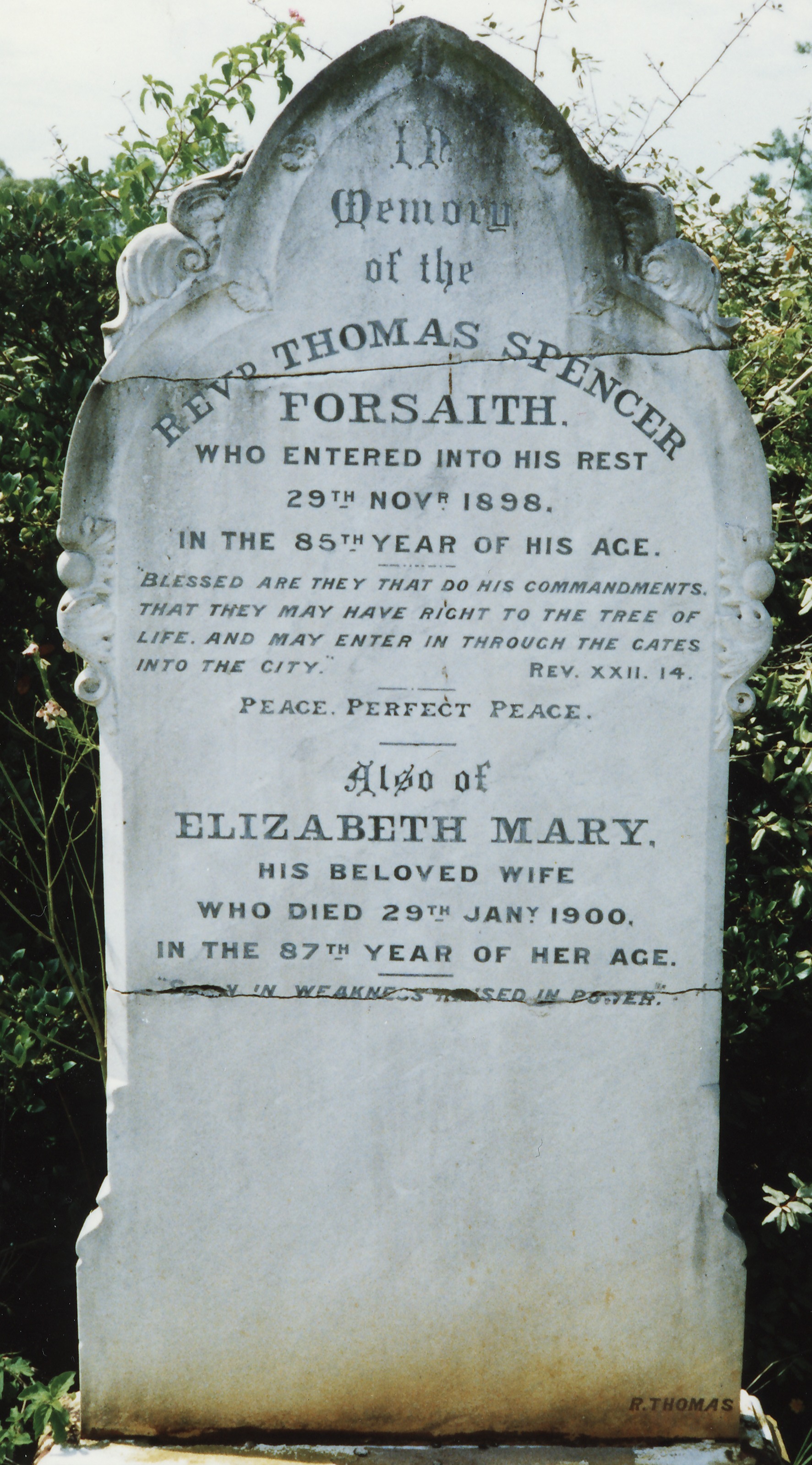

Death and commemoration

He began his memoirs in early 1898 and wrote a will on 13 June 1898. The will requests that busts of him and his wife be installed at the Congregational Church in Parramatta, but this has never happened. The first twelve chapters of his auto-biography have been lost, but the remaining chapters are held at theNational Library

A national library is a library established by a government as a country's preeminent repository of information. Unlike public libraries, these rarely allow citizens to borrow books. Often, they include numerous rare, valuable, or significant wo ...

in Canberra

Canberra ( )

is the capital city of Australia. Founded following the federation of the colonies of Australia as the seat of government for the new nation, it is Australia's largest inland city and the eighth-largest city overall. The ci ...

. Forsaith died on 29 November 1898 in Parramatta. He is buried at Rookwood Cemetery

Rookwood Cemetery (officially named Rookwood Necropolis) is a heritage-listed cemetery in Rookwood, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia. It is the largest List of necropolises, necropolis in the Southern Hemisphere and is the world's largest ...

, sharing a grave with his wife, who died on 29 January 1900. Their daughter had died before them in 1894, and her husband Thomas Morell MacDonald was one of the executors of Thomas Forsaith's will.

He was described as "calmly spending the evening of life in the midst of the orange groves at Parramatta, a venerable, vigorous, and versatile octogenarian colonist."

Notes

References

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Forsaith, Thomas 1814 births 1898 deaths Members of the New Zealand House of Representatives People from the Northland Region People from Auckland New Zealand drapers English emigrants to New Zealand Unsuccessful candidates in the 1855 New Zealand general election New Zealand MPs for Auckland electorates New Zealand MPs for North Island electorates Businesspeople from London 19th-century New Zealand politicians Burials at Rookwood Cemetery 19th-century English businesspeople