Thomas Clarkson on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Thomas Clarkson (28 March 1760 – 26 September 1846) was an English

Abolition Project website. Retrieved 28 September 2014. He rode by horseback some 35,000 miles for evidence and visited local anti-slave trade societies founded across the country. He enlisted the help of

The Abolition Project website. Retrieved 28 September 2014. Clarkson also continued to write against the slave trade. He filled his works with vivid firsthand descriptions from sailors, surgeons and others who had been involved in the slave traffic. In 1788 Clarkson published large numbers of his ''Essay on the Impolicy of the African Slave Trade'' (1788). Another example was his "An Essay on the Slave Trade" (1789), the account of a sailor who had served aboard a slave ship. These works provided a grounding for William Wilberforce's first abolitionist speech in the House of Commons on 12 May 1789, and his 12 propositions. In 1791 Wilberforce introduced the first Bill to abolish the slave trade; it was easily defeated by 163 votes to 88. As Wilberforce continued to bring the issue of the slave trade before Parliament, Clarkson travelled and wrote anti-slavery works. Based on a plan of a slave ship he acquired in Portsmouth, he had an image drawn of slaves loaded on the slave ship ''

In 1791 Wilberforce introduced the first Bill to abolish the slave trade; it was easily defeated by 163 votes to 88. As Wilberforce continued to bring the issue of the slave trade before Parliament, Clarkson travelled and wrote anti-slavery works. Based on a plan of a slave ship he acquired in Portsmouth, he had an image drawn of slaves loaded on the slave ship ''

The Abolition Project, 2009. Retrieved 28 September 2014 This was the beginning of their protracted parliamentary campaign, during which Wilberforce introduced a motion in favour of abolition almost every year. Clarkson, Wilberforce and the other members of the On 19 January 1796 he married Catherine Buck of Bury St Edmunds, Suffolk; their only child Thomas was born in 1796. They moved to the south of England for the sake of Catherine's health, and settled at Bury St Edmunds from 1806 to 1816. They then lived at Playford Hall, between

On 19 January 1796 he married Catherine Buck of Bury St Edmunds, Suffolk; their only child Thomas was born in 1796. They moved to the south of England for the sake of Catherine's health, and settled at Bury St Edmunds from 1806 to 1816. They then lived at Playford Hall, between

Throughout his life Clarkson was a frequent guest of Joseph Hardcastle (the first treasurer of the

Throughout his life Clarkson was a frequent guest of Joseph Hardcastle (the first treasurer of the

* In 1833 the inhabitants of Wisbech requested Clarkson sit for his portrait; it was hung in the council chamber.

*In 1834, after the abolition of slavery in Jamaica,

* In 1833 the inhabitants of Wisbech requested Clarkson sit for his portrait; it was hung in the council chamber.

*In 1834, after the abolition of slavery in Jamaica,

Thomas Clarkson website

Ely Cathedral

(Part of his British Abolitionists project)

Teaching resources about Slavery and Abolition on blackhistory4schools.com

* *

Works by Thomas Clarkson at the online library of liberty

The Louverture Project

Thomas Clarkson �

Thoughts on The Haitian Revolution

Excerpt from an 1823 Clarkson book.

Parliament & The British Slave Trade 1600–1807

Wisbech & Fenland Museum, whose collection includes the Clarkson Chest.

Thomas Clarkson Community College

The Abolition Project website

Bristol Historical Society *

''Report of the Brown University Steering Committee on Slavery and Justice''

study of relationship of university to the slave trade

Clarkson"

the life of Thomas Clarkson, The Wisbech Society and Preservation Trust.

"The History of the Rise, Progress, and Accomplishment of the Abolition of the African Slave Trade"

Thomas Clarkson manuscript, held by Haverford College {{DEFAULTSORT:Clarkson, Thomas 1760 births 1846 deaths Alumni of St John's College, Cambridge 18th-century Anglican deacons Anglican saints Burials in Suffolk Christian abolitionists English abolitionists English Christian pacifists History of Sierra Leone People educated at Wisbech Grammar School People educated at St Paul's School, London People from Suffolk Coastal (district) People from Wisbech Sierra Leone Creole history

abolitionist

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The British ...

, and a leading campaigner against the slave trade

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

in the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts esta ...

. He helped found The Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade

The Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade, also known as the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade, and sometimes referred to as the Abolition Society or Anti-Slavery Society, was a British abolitionist group formed on ...

(also known as the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade) and helped achieve passage of the Slave Trade Act 1807

The Slave Trade Act 1807, officially An Act for the Abolition of the Slave Trade, was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom prohibiting the slave trade in the British Empire. Although it did not abolish the practice of slavery, it ...

, which ended British trade in slaves.

He became a pacifist in 1816 and, together with his brother John

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Secon ...

, was among the twelve founders of the Society for the Promotion of Permanent and Universal Peace

The Peace Society, International Peace Society or London Peace Society originally known as the Society for the Promotion of Permanent and Universal Peace, was a pioneering British pacifist organisation that was active from 1816 until the 1930s.

Hi ...

.

In his later years, Clarkson campaigned for the abolition of slavery worldwide. In 1840, he was the key speaker at the Anti-Slavery Society's (today known as Anti-Slavery International

Anti-Slavery International, founded as the British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society in 1839, is an international non-governmental organisation, registered charity and advocacy group, based in the United Kingdom. It is the world's oldest interna ...

) first conference in London which campaigned to end slavery in other countries.

Early life and education

Clarkson was the eldest son of the Reverend John Clarkson (1710–1766), aChurch of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Britain ...

priest and master of Wisbech Grammar School

Wisbech Grammar School is an 11–18 mixed, Church of England, independent day school and sixth form in Wisbech, Isle of Ely, Cambridgeshire, England. Founded by the Guild of the Holy Trinity in 1379, it is one of the oldest schools in the co ...

, and his wife Anne née Ward (died 1799). He was baptised on 26 May 1760 at the Parish Church of St Peter and St Paul, Wisbech

The Parish Church of St Peter and St Paul or St Peter's Church, Wisbech, is an Anglican church in the market town and Port of Wisbech, the Isle of Ely, Cambridgeshire, England. It is an active parish church in the Diocese of Ely. The church wa ...

.

His siblings were John

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Secon ...

(born 1764) and Anne. Both boys attended Wisbech Grammar School, Hill Street where the family lived. After the death of his father the family moved into a house on Bridge Street which is now marked by a blue plaque

A blue plaque is a permanent sign installed in a public place in the United Kingdom and elsewhere to commemorate a link between that location and a famous person, event, or former building on the site, serving as a historical marker. The term i ...

. Thomas went on to St Paul's School in London in 1775, where he obtained an exhibition. He entered St John's College, Cambridge

St John's College is a Colleges of the University of Cambridge, constituent college of the University of Cambridge founded by the House of Tudor, Tudor matriarch Lady Margaret Beaufort. In constitutional terms, the college is a charitable corpo ...

in 1779. An excellent student, he appears to have enjoyed his time at the University of Cambridge

, mottoeng = Literal: From here, light and sacred draughts.

Non literal: From this place, we gain enlightenment and precious knowledge.

, established =

, other_name = The Chancellor, Masters and Schola ...

, although he was a serious, devout man. He received his Bachelor of Arts

Bachelor of arts (BA or AB; from the Latin ', ', or ') is a bachelor's degree awarded for an undergraduate program in the arts, or, in some cases, other disciplines. A Bachelor of Arts degree course is generally completed in three or four years ...

degree in 1783 and was set to continue at Cambridge to follow in his father's footsteps and enter the Anglican ministry

The Anglican ministry is both the leadership and agency of Christian service in the Anglican Communion. "Ministry" commonly refers to the office of ordained clergy: the ''threefold order'' of bishops, priests and deacons. More accurately, Anglica ...

. He was ordained a deacon

A deacon is a member of the diaconate, an office in Christian churches that is generally associated with service of some kind, but which varies among theological and denominational traditions. Major Christian churches, such as the Catholic Churc ...

but never proceeded to priest's orders.

Revelation of the horrors of slavery

In 1785 Clarkson entered aLatin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

essay competition at the university that was to set him on the course for most of the remainder of his life. The topic of the essay, set by university vice-chancellor Peter Peckard

Peter Peckard (c. 1718 – 8 December 1797) was an English Whig, Vice-Chancellor of Cambridge University, Church of England minister and abolitionist.

, was ''Anne liceat invitos in servitutem dare'' ("is it lawful to make slaves of others against their will?"), and it led Clarkson to consider the question of the slave trade

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

. He read everything he could on the subject, including the works of Anthony Benezet

Anthony Benezet, born Antoine Bénézet (January 31, 1713May 3, 1784), was a French-American abolitionist and educator who was active in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. One of the early American abolitionists, Benezet founded one of the world's fir ...

, a Quaker

Quakers are people who belong to a historically Protestant Christian set of Christian denomination, denominations known formally as the Religious Society of Friends. Members of these movements ("theFriends") are generally united by a belie ...

abolitionist

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The British ...

, as well as first-hand accounts of the African slave trade such as Francis Moore's ''Travels into the Interior Parts of Africa''. He also researched the topic by meeting and interviewing those who had personal experience of the slave trade and of slavery.

After winning the prize, Clarkson had what he called a spiritual revelation from God as he travelled by horse between Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a university city and the county town in Cambridgeshire, England. It is located on the River Cam approximately north of London. As of the 2021 United Kingdom census, the population of Cambridge was 145,700. Cambridge bec ...

and London. He broke his journey at Wadesmill

Wadesmill is a hamlet in Hertfordshire, England, located on the north side of the River Rib with an estimated population of 264. At the 2011 Census the population of the hamlet was included in the civil parish of Thundridge. Running through the ...

, near Ware

Ware may refer to:

People

* Ware (surname)

* William of Ware (), English Franciscan theologian

Places Canada

* Fort Ware, British Columbia

United Kingdom

* Ware, Devon

*Ware, Hertfordshire

* Ware, Kent

United States

* Ware, Elmore County ...

, Hertfordshire. He later wrote:

As it is usual to read these essays publicly in the senate-house soon after the prize is adjudged, I was called to Cambridge for this purpose. I went and performed my office. On returning however to London, the subject of it almost wholly engrossed my thoughts. I became at times very seriously affected while upon the road. I stopped my horse occasionally, and dismounted and walked. I frequently tried to persuade myself in these intervals that the contents of my Essay could not be true. The more however I reflected upon them, or rather upon the authorities on which they were founded, the more I gave them credit. Coming in sight of Wades Mill in Hertfordshire, I sat down disconsolate on the turf by the roadside and held my horse. Here a thought came into my mind, that if the contents of the Essay were true, it was time some person should see these calamities to their end. Agitated in this manner I reached home. This was in the summer of 1785.This experience and sense of calling ultimately led him to devote his life to abolishing the slave trade. Having translated the essay into English so that it could gain a wider audience, Clarkson published it in pamphlet form in 1786 as ''An essay on the slavery and commerce of the human species, particularly the African, translated from a Latin Dissertation.'' The essay was influential, resulting in Clarkson's being introduced to many others who were sympathetic to abolition, some of whom had already published and campaigned against slavery. These included influential men such as James Ramsay and

Granville Sharp

Granville Sharp (10 November 1735 – 6 July 1813) was one of the first British campaigners for the abolition of the slave trade. He also involved himself in trying to correct other social injustices. Sharp formulated the plan to settle black ...

, many Quakers, and other nonconformist

Nonconformity or nonconformism may refer to:

Culture and society

* Insubordination, the act of willfully disobeying an order of one's superior

*Dissent, a sentiment or philosophy of non-agreement or opposition to a prevailing idea or entity

** ...

s. The movement had been gathering strength for some years, having been founded by Quakers both in Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* The United Kingdom, a sovereign state in Europe comprising the island of Great Britain, the north-eastern part of the island of Ireland and many smaller islands

* Great Britain, the largest island in the United King ...

and in the United States, with support from other nonconformists, primarily Methodists and Baptists, on both sides of the Atlantic. In 1783, 300 Quakers, chiefly from the London area, presented Parliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

with their signatures on the first petition against the slave trade.

Following this step, a small offshoot group formed the Committee for the Abolition of the Slave Trade

The Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade, also known as the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade, and sometimes referred to as the Abolition Society or Anti-Slavery Society, was a British abolitionist group formed on ...

, a small non-denominational group that could lobby more successfully by incorporating Anglicans. Under the Test Act

The Test Acts were a series of English penal laws that served as a religious test for public office and imposed various civil disabilities on Roman Catholics and nonconformists. The underlying principle was that only people taking communion in ...

, only those prepared to receive the sacrament of the Lord's Supper according to the rites of the Church of England were permitted to serve as MPs, thus Quakers were generally barred from the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. ...

until the early nineteenth century. The twelve founding members included nine Quakers, and three pioneering Anglicans: Clarkson, Granville Sharp

Granville Sharp (10 November 1735 – 6 July 1813) was one of the first British campaigners for the abolition of the slave trade. He also involved himself in trying to correct other social injustices. Sharp formulated the plan to settle black ...

, and Philip Sansom. They were sympathetic to the religious revival that had predominantly nonconformist origins, but which sought wider non-denominational support for a "Great Awakening" amongst believers.

Anti-slavery campaign

Encouraged by publication of Clarkson's essay, an informal committee was set up between small groups from the petitioning Quakers, Clarkson and others, with the goal of lobbying members of parliament (MPs). In May 1787, they formed theCommittee for the Abolition of the Slave Trade

The Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade, also known as the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade, and sometimes referred to as the Abolition Society or Anti-Slavery Society, was a British abolitionist group formed on ...

. The Committee included Granville Sharp

Granville Sharp (10 November 1735 – 6 July 1813) was one of the first British campaigners for the abolition of the slave trade. He also involved himself in trying to correct other social injustices. Sharp formulated the plan to settle black ...

as chairman and Josiah Wedgwood

Josiah Wedgwood (12 July 1730 – 3 January 1795) was an English potter, entrepreneur and abolitionist. Founding the Wedgwood company in 1759, he developed improved pottery bodies by systematic experimentation, and was the leader in the indust ...

, as well as Clarkson. Clarkson also approached the young William Wilberforce

William Wilberforce (24 August 175929 July 1833) was a British politician, philanthropist and leader of the movement to abolish the slave trade. A native of Kingston upon Hull, Yorkshire, he began his political career in 1780, eventually becom ...

, who as an Anglican and an MP was connected within the British Parliament. Wilberforce was one of few parliamentarians to have had sympathy with the Quaker petition; he had already put a question about the slave trade before the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. ...

, and became known as one of the earliest Anglican abolitionists.

Clarkson took a leading part in the affairs of the Committee for the Abolition of the Slave Trade

The Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade, also known as the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade, and sometimes referred to as the Abolition Society or Anti-Slavery Society, was a British abolitionist group formed on ...

, and was tasked to collect evidence to support the abolition of the slave trade. He faced strong opposition from supporters of the trade in some of the cities he visited. The slave traders were an influential group because the trade was a legitimate and highly lucrative business, generating prosperity for many of the ports.

Liverpool

Liverpool is a city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. With a population of in 2019, it is the 10th largest English district by population and its metropolitan area is the fifth largest in the United Kingdom, with a popul ...

was a major base of slave-trading syndicates and home port for their ships. In 1787, Clarkson was attacked and nearly killed when visiting the city, as a gang of sailors was paid to assassinate him. He barely escaped with his life. Elsewhere, however, he gathered support. Clarkson's speech at the collegiate church in Manchester (now Manchester Cathedral) on 28 October 1787 galvanised the anti-slavery campaign in the city. That same year, Clarkson published the pamphlet ''A Summary View of the Slave Trade and of the Probable Consequences of Its Abolition''.

Clarkson was very effective at giving the committee a high public profile: he spent the next two years travelling around England, promoting the cause and gathering evidence. He interviewed 20,000 sailors during his research. He obtained equipment used on slave-ships, such as iron handcuffs, leg-shackles, and thumbscrews; instruments for forcing open slaves' jaws; and branding irons. He published engravings of the tools in pamphlets and displayed the instruments at public meetings.

Clarkson's research took him to English ports such as Bristol

Bristol () is a city, ceremonial county and unitary authority in England. Situated on the River Avon, it is bordered by the ceremonial counties of Gloucestershire to the north and Somerset to the south. Bristol is the most populous city in ...

, where he received information from the landlord of the Seven Stars pub. (The building still stands in Thomas Lane.) He also travelled repeatedly to Liverpool and London, collecting evidence to support the abolitionist case.

Clarkson visited ''The Lively,'' an African trading ship. Although not a slave ship, it carried cargo of high-quality goods: carved ivory and woven textiles, beeswax

Beeswax (''cera alba'') is a natural wax produced by honey bees of the genus ''Apis''. The wax is formed into scales by eight wax-producing glands in the abdominal segments of worker bees, which discard it in or at the hive. The hive workers ...

, and produce such as palm oil and peppers

Pepper or peppers may refer to:

Food and spice

* Piperaceae or the pepper family, a large family of flowering plant

** Black pepper

* ''Capsicum'' or pepper, a genus of flowering plants in the nightshade family Solanaceae

** Bell pepper

** Chili ...

. Impressed by the high quality of craftsmanship and skill expressed in these items, Clarkson was horrified to think that the people who could create such items were being enslaved. He bought samples from the ship and started a collection to which he added over the years. It included crops, spices and raw material

A raw material, also known as a feedstock, unprocessed material, or primary commodity, is a basic material that is used to produce goods, finished goods, energy, or intermediate materials that are feedstock for future finished products. As feedst ...

s, along with refined trade goods.

Clarkson noticed that pictures and artefacts could influence public opinion more than words alone. He began to display items from his collection of fine goods to reinforce his anti-slavery lectures. Demonstrating that Africans were highly skilled artisans, he argued for an alternative humane trading system based on goods rather than labourers. He carried a "box" featuring his collection, which became an important part his public meetings.Home: "Thomas Clarkson"Abolition Project website. Retrieved 28 September 2014. He rode by horseback some 35,000 miles for evidence and visited local anti-slave trade societies founded across the country. He enlisted the help of

Alexander Falconbridge

Alexander Falconbridge (c. 1760–1792) was a British surgeon who took part in four voyages in slave ships between 1782 and 1787. In time he became an abolitionist and in 1788 published ''An Account of the Slave Trade on the Coast of Africa''. In ...

and James Arnold, two ship's surgeons he had met in Liverpool. They had been on many voyages aboard slave ships, and were able to recount their experiences in detail for publication."Thomas Clarkson: Collecting Evidence"The Abolition Project website. Retrieved 28 September 2014. Clarkson also continued to write against the slave trade. He filled his works with vivid firsthand descriptions from sailors, surgeons and others who had been involved in the slave traffic. In 1788 Clarkson published large numbers of his ''Essay on the Impolicy of the African Slave Trade'' (1788). Another example was his "An Essay on the Slave Trade" (1789), the account of a sailor who had served aboard a slave ship. These works provided a grounding for William Wilberforce's first abolitionist speech in the House of Commons on 12 May 1789, and his 12 propositions.

Olaudah Equiano

Olaudah Equiano (; c. 1745 – 31 March 1797), known for most of his life as Gustavus Vassa (), was a writer and abolitionist from, according to his memoir, the Eboe (Igbo) region of the Kingdom of Benin (today southern Nigeria). Enslaved a ...

(Gustavus Vassa) a member of the Sons of Africa

The Sons of Africa were a late 18th-century group in Britain that campaigned to end African chattel slavery. The "corresponding society" has been called the Britain's first black political organisation. Its members were educated Africans in Lond ...

published his memoir, ''The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano

''The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, Or Gustavus Vassa, The African'', first published in 1789 in London,

'', one of the genre of what became known as slave narratives

The slave narrative is a type of literary genre involving the (written) autobiographical accounts of enslaved Africans, particularly in the Americas. Over six thousand such narratives are estimated to exist; about 150 narratives were published as s ...

– accounts by slaves who achieved freedom. As an African with direct experience of the slave trade and slavery, Equiano was pleased that his book became highly influential in the anti-slavery movement. Clarkson wrote to the Rev Thomas Jones MA (1756-1807) at Trinity College, Cambridge

Trinity College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge. Founded in 1546 by Henry VIII, King Henry VIII, Trinity is one of the largest Cambridge colleges, with the largest financial endowment of any college at either Cambridge ...

, to introduce Equiano to him and the community. He asked for aid from the Rev Jones in selling copies of the memoir and arranging for Equiano to visit Cambridge to lecture.

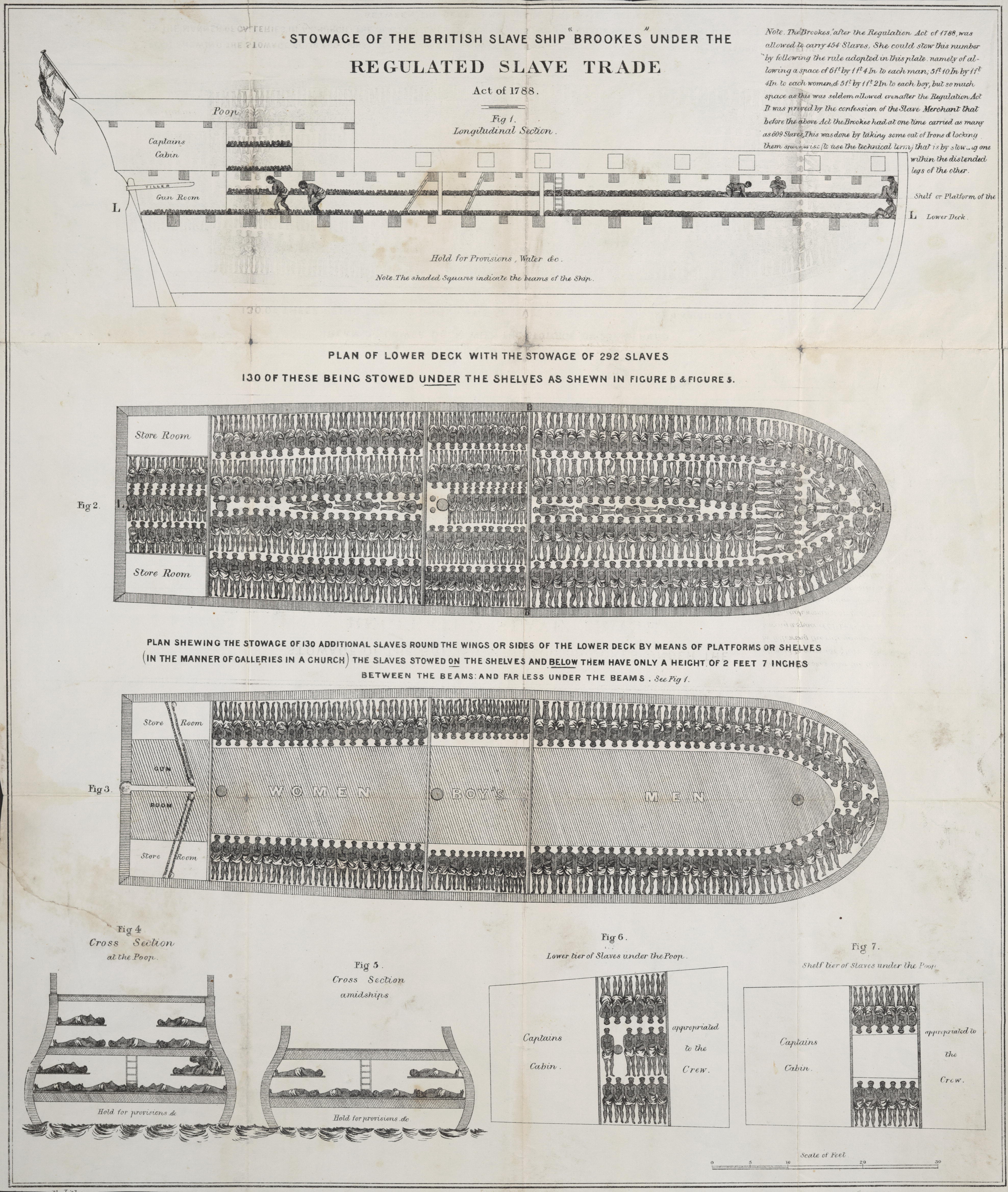

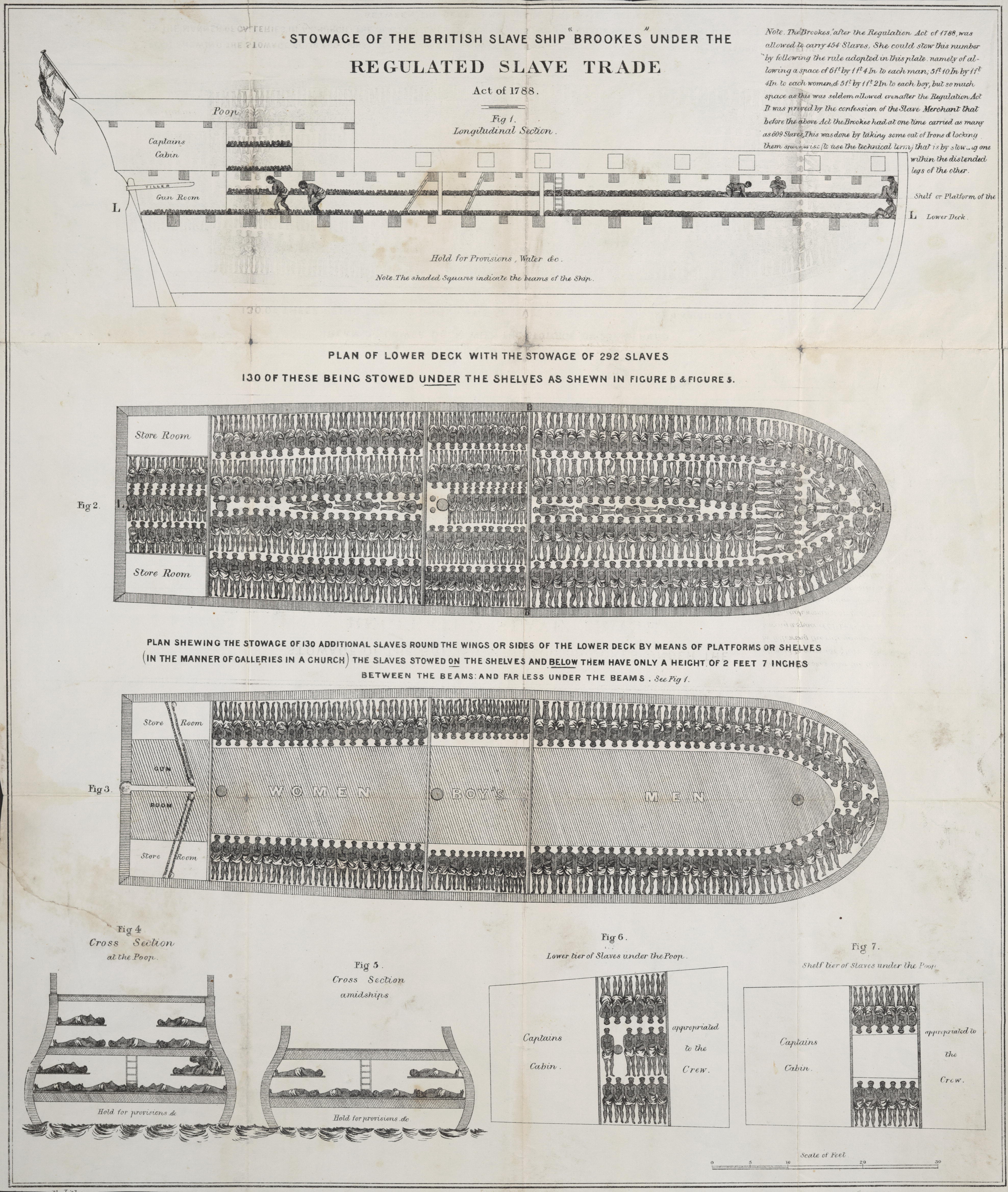

In 1791 Wilberforce introduced the first Bill to abolish the slave trade; it was easily defeated by 163 votes to 88. As Wilberforce continued to bring the issue of the slave trade before Parliament, Clarkson travelled and wrote anti-slavery works. Based on a plan of a slave ship he acquired in Portsmouth, he had an image drawn of slaves loaded on the slave ship ''

In 1791 Wilberforce introduced the first Bill to abolish the slave trade; it was easily defeated by 163 votes to 88. As Wilberforce continued to bring the issue of the slave trade before Parliament, Clarkson travelled and wrote anti-slavery works. Based on a plan of a slave ship he acquired in Portsmouth, he had an image drawn of slaves loaded on the slave ship ''Brookes

Brookes is a surname. Notable people with the surname include:

* Barbara Brookes, New Zealand historian

* Bruno Brookes, English broadcaster

* Dennis Brookes, English cricketer

* Ed Brookes (1881–1958), Irish international soccer player

* ...

''; he published this in London in 1791, took the image with him on lectures, and provided it to Wilberforce with other anti-slave trade materials for use in parliament."Brookes' Diagram-Clarkson's Box"The Abolition Project, 2009. Retrieved 28 September 2014 This was the beginning of their protracted parliamentary campaign, during which Wilberforce introduced a motion in favour of abolition almost every year. Clarkson, Wilberforce and the other members of the

Committee for the Abolition of the Slave Trade

The Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade, also known as the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade, and sometimes referred to as the Abolition Society or Anti-Slavery Society, was a British abolitionist group formed on ...

and their supporters, were responsible for generating and sustaining a national movement that mobilised public opinion as never before. Parliament, however, refused to pass the bill. The outbreak of War with France effectively prevented further debate for many years. Henry Dundas, 1st Viscount Melville

Henry Dundas, 1st Viscount Melville, PC, FRSE (28 April 1742 – 28 May 1811), styled as Lord Melville from 1802, was the trusted lieutenant of British Prime Minister William Pitt and the most powerful politician in Scotland in the late 18t ...

, who was the Secretary of State for War for prime minister William Pitt the Younger

William Pitt the Younger (28 May 175923 January 1806) was a British statesman, the youngest and last prime minister of Great Britain (before the Acts of Union 1800) and then first prime minister of the United Kingdom (of Great Britain and Ire ...

, instructed Sir Adam Williamson, the lieutenant-governor of Jamaica, to sign an agreement with representatives of the French colonists of Saint Domingue

Saint-Domingue () was a French colony in the western portion of the Caribbean island of Hispaniola, in the area of modern-day Haiti, from 1659 to 1804. The name derives from the Spanish main city in the island, Santo Domingo, which came to re ...

, later Haiti, that promised to restore the ancien regime

''Ancien'' may refer to

* the French word for "ancient, old"

** Société des anciens textes français

* the French for "former, senior"

** Virelai ancien

** Ancien Régime

** Ancien Régime in France

''Ancien'' may refer to

* the French word fo ...

, slavery and discrimination against mixed-race colonists, a move that drew criticism from abolitionists Wilberforce and Clarkson.

By 1794, Clarkson's health was failing, as he suffered from exhaustion. He retired from the campaign and spent some time in the Lake District

The Lake District, also known as the Lakes or Lakeland, is a mountainous region in North West England. A popular holiday destination, it is famous for its lakes, forests, and mountains (or ''fells''), and its associations with William Wordswor ...

, where he bought an estate at Ullswater

Ullswater is the second largest lake in the English Lake District, being about long and wide, with a maximum depth a little over . It was scooped out by a glacier in the Last Ice Age.

Geography

It is a typical Lake District "ribbon lake", ...

. There he became a friend of the poet William Wordsworth

William Wordsworth (7 April 177023 April 1850) was an English Romantic poet who, with Samuel Taylor Coleridge, helped to launch the Romantic Age in English literature with their joint publication '' Lyrical Ballads'' (1798).

Wordsworth's ' ...

.

On 19 January 1796 he married Catherine Buck of Bury St Edmunds, Suffolk; their only child Thomas was born in 1796. They moved to the south of England for the sake of Catherine's health, and settled at Bury St Edmunds from 1806 to 1816. They then lived at Playford Hall, between

On 19 January 1796 he married Catherine Buck of Bury St Edmunds, Suffolk; their only child Thomas was born in 1796. They moved to the south of England for the sake of Catherine's health, and settled at Bury St Edmunds from 1806 to 1816. They then lived at Playford Hall, between Ipswich

Ipswich () is a port town and borough in Suffolk, England, of which it is the county town. The town is located in East Anglia about away from the mouth of the River Orwell and the North Sea. Ipswich is both on the Great Eastern Main Line r ...

and Woodbridge in Suffolk.

When the war with France appeared to be almost over, in 1804 Clarkson and his allies revived the anti-slave trade campaign. After his ten years' retreat, he mounted his horse to travel again all over Great Britain and canvass support for the measure. He appeared to have returned with all his old enthusiasm and vigour. He was especially active in persuading MPs to back the parliamentary campaign.

Passage of the Slave Trade Act

Slave Trade Act is a stock short title used for legislation in the United Kingdom and the United States that relates to the slave trade.

The "See also" section lists other Slave Acts, laws, and international conventions which developed the conce ...

in 1807 ended the trade and provided for British naval support to enforce the law. Clarkson directed his efforts toward enforcement and extending the campaign to the rest of Europe, as Spain and France continued a trade in their American colonies. The United States also prohibited the international trade in 1807, and operated chiefly in the Caribbean to interdict illegal slave ships. In 1808 Clarkson published a book about the progress in abolition of the slave trade. He travelled to Paris in 1814 and Aix-la-Chapelle in 1818, trying to reach international agreement on a timetable for abolition of the trade. He contributed the article on the "Slave Trade" for ''Rees's Cyclopædia

Rees's ''Cyclopædia'', in full ''The Cyclopædia; or, Universal Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, and Literature'' was an important 19th-century British encyclopaedia edited by Rev. Abraham Rees (1743–1825), a Presbyterian minister and scholar w ...

,'' Vol. 33, 1816.

Later career

In 1823 the Society for the Mitigation and Gradual Abolition of Slavery (later known as the Anti-Slavery Society) was formed. Clarkson travelled the country to build support for its goal. He covered 10,000 miles, and activated the network of sympathetic anti-slavery societies which had been formed. This resulted in 777 petitions being delivered to parliament demanding the total emancipation of slaves. When the society adopted a policy of immediate emancipation, Clarkson and Wilberforce appeared together for the last time to lend their support. In 1833 theSlavery Abolition Act

The Slavery Abolition Act 1833 (3 & 4 Will. IV c. 73) was an Act of Parliament, Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom which provided for the gradual abolition of slavery in most parts of the British Empire. It was passed by Charles Grey, 2n ...

was passed, with emancipation completed on 1 August 1838 in the British colonies.

Clarkson lived an additional 13 years. Although his eyesight was failing, he continued to campaign for abolition, focusing on the United States, where slavery had expanded in the Deep South and some states west of the Mississippi River. He was the principal speaker in 1840 at the opening of the first World's Anti-Slavery Convention

The World Anti-Slavery Convention met for the first time at Exeter Hall in London, on 12–23 June 1840. It was organised by the British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society, largely on the initiative of the English Quaker Joseph Sturge. The excl ...

in Freemasons' Hall, London, chaired by Thomas Binney

Thomas Binney (1798–1874) was an English Congregationalist divine of the 19th century, popularly known as the "Archbishop of Nonconformity". He was noted for sermons and writings in defence of the principles of Nonconformity, for devotional ...

. The conference was designed to build support for abolishing slavery worldwide and included delegates from France, the US, Haiti

Haiti (; ht, Ayiti ; French: ), officially the Republic of Haiti (); ) and formerly known as Hayti, is a country located on the island of Hispaniola in the Greater Antilles archipelago of the Caribbean Sea, east of Cuba and Jamaica, and ...

(established in 1804 as the first black republic in the Western Hemisphere) and Jamaica

Jamaica (; ) is an island country situated in the Caribbean Sea. Spanning in area, it is the third-largest island of the Greater Antilles and the Caribbean (after Cuba and Hispaniola). Jamaica lies about south of Cuba, and west of His ...

.

The scene at Clarkson's opening address was painted in a commemorative work, now in the National Portrait Gallery, London. The emancipated slave, Henry Beckford (a Baptist deacon in Jamaica), is shown in the right foreground. Clarkson and the prominent abolitionist Quaker William Allen William Allen may refer to:

Politicians

United States

*William Allen (congressman) (1827–1881), United States Representative from Ohio

*William Allen (governor) (1803–1879), U.S. Representative, Senator, and 31st Governor of Ohio

*William ...

were to the left, the main axis of interest. In 1846 Clarkson was host to Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass (born Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey, February 1817 or 1818 – February 20, 1895) was an American social reformer, abolitionist, orator, writer, and statesman. After escaping from slavery in Maryland, he became ...

, an American former slave who had escaped to freedom in the North and became a prominent abolitionist

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The British ...

, on his first visit to England. Douglass spoke at numerous meetings and attracted considerable attention and support. At risk even prior to passage in the US of the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850

The Fugitive Slave Act or Fugitive Slave Law was passed by the United States Congress on September 18, 1850, as part of the Compromise of 1850 between Southern interests in slavery and Northern Free-Soilers.

The Act was one of the most cont ...

, Douglass was grateful when British friends raised the money and negotiated purchase of his freedom from his former master in December 1846.

Later life

Throughout his life Clarkson was a frequent guest of Joseph Hardcastle (the first treasurer of the

Throughout his life Clarkson was a frequent guest of Joseph Hardcastle (the first treasurer of the London Missionary Society

The London Missionary Society was an interdenominational evangelical missionary society formed in England in 1795 at the instigation of Welsh Congregationalist minister Edward Williams. It was largely Reformed in outlook, with Congregational miss ...

) at Hatcham House in Deptford

Deptford is an area on the south bank of the River Thames in southeast London, within the London Borough of Lewisham. It is named after a ford of the River Ravensbourne. From the mid 16th century to the late 19th it was home to Deptford Dock ...

, then a Surrey

Surrey () is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in South East England, bordering Greater London to the south west. Surrey has a large rural area, and several significant urban areas which form part of the Greater London Built-up Area. ...

village. In the early 1790s he met his wife, a niece of Mrs Hardcastle here. Clarkson wrote much of his ''History of the Abolition of the Slave Trade'' (1808) at Hatcham House.

His younger brother John Clarkson

John Gibson Clarkson (July 1, 1861 – February 4, 1909) was a Major League Baseball right-handed pitcher. He played from 1882 to 1894. Born in Cambridge, Massachusetts, Clarkson played for the Worcester Ruby Legs (1882), Chicago White Stocking ...

(1764–1828) took a major part in organising the relocation of approximately 1200 Black Loyalists to Africa in early 1792. They were among the 3000 former United States slaves given their freedom by the British and granted land in Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia ( ; ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is one of the three Maritime provinces and one of the four Atlantic provinces. Nova Scotia is Latin for "New Scotland".

Most of the population are native Eng ...

, Canada, after the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

. This group chose to go to the new colony of Sierra Leone

Sierra Leone,)]. officially the Republic of Sierra Leone, is a country on the southwest coast of West Africa. It is bordered by Liberia to the southeast and Guinea surrounds the northern half of the nation. Covering a total area of , Sierr ...

established by the British in West Africa, founding Freetown

Freetown is the capital and largest city of Sierra Leone. It is a major port city on the Atlantic Ocean and is located in the Western Area of the country. Freetown is Sierra Leone's major urban, economic, financial, cultural, educational and p ...

. John Clarkson was appointed its first Governor.

Thomas Clarkson died on 26 September 1846 in Playford, Suffolk

Playford is a small village in Suffolk, England, on the outskirts of Ipswich. It has about 215 residents in 90 households. The name comes from the Old English '' plega'' meaning play, sport; used of a place for games, or a courtship or mating-pl ...

. He was buried in the village on 2 October at St Mary's Church.

The Clarkson chest and Clarkson Collection are now on display in Wisbech & Fenland Museum

The Wisbech & Fenland Museum, located in the town of Wisbech in the Isle of Ely, Cambridgeshire, England, is one of the oldest purpose-built museums in the United Kingdom. The museum logo is W&F.

History

Initially a member-based organisation ...

.

Legacy

Free Villages

Free Villages is the term used for Caribbean settlements, particularly in Jamaica, founded in the 1830s and 1840s with land for freedmen independent of the control of plantation owners and other major estates. The concept was initiated by English ...

were founded for the settlement of freedmen. The town of Clarksonville, named in his honour, was established in Saint Ann Parish

Saint Ann is the largest parish in Jamaica. It is situated on the north coast of the island, in the county of Middlesex, roughly halfway between the eastern and western ends of the island. It is often called "the Garden Parish of Jamaica" on ac ...

, Jamaica.

* In 1839 the Court of the Common Council gave Clarkson the Freedom of the City of London.

*In 1839 a mission station in South Africa was named Clarkson by Moravian missionary Hans Peter Hallbeck in honour of Clarkson and his abolition work.

* Opened in 1847, Wisbech & Fenland Museum

The Wisbech & Fenland Museum, located in the town of Wisbech in the Isle of Ely, Cambridgeshire, England, is one of the oldest purpose-built museums in the United Kingdom. The museum logo is W&F.

History

Initially a member-based organisation ...

has a permanent display of anti-slavery artefacts collected by Thomas Clarkson and his brother John, and organises events linked to anti-slavery.

*In 1857, an obelisk commemorating Clarkson was erected in St Mary's churchyard in Playford to a design by George Biddell Airy

Sir George Biddell Airy (; 27 July 18012 January 1892) was an English mathematician and astronomer, and the seventh Astronomer Royal from 1835 to 1881. His many achievements include work on planetary orbits, measuring the mean density of the E ...

.

*In 1879, a monument to Clarkson was erected in Wadesmill; it reads: "On this spot where stands this monument in the month of June 1785 Thomas Clarkson resolved to devote his life to bringing about the abolition of the slave trade."

*The Clarkson Memorial

The Clarkson Memorial in Wisbech, Isle of Ely, Cambridgeshire, England commemorates Thomas Clarkson (1760–1846), a central figure in the campaign against the slave trade in the British empire, and a former native of Wisbech. It was erected ...

was erected in Wisbech to commemorate his life and work. Work started in October 1880 and it was unveiled by Sir Henry Brand, Speaker of the House of Commons on 11 November 1881. The Clarkson School, Wisbech is named after him, as is Thomas Clarkson Academy

Thomas Clarkson Academy is a mixed secondary school and sixth form located in Wisbech, Cambridgeshire, England.

A new school building has been constructed that was designed by Ken Shuttleworth and Make Architects.

Formerly the Queen's Schoo ...

. A tree-lined road in Wisbech is named Clarkson Avenue in his honour (a side street is Wilberforce Road), and a pub opposite was called the Clarkson Arms (closed in 2018). Nearby is Clarkson Court.

* A blue plaque

A blue plaque is a permanent sign installed in a public place in the United Kingdom and elsewhere to commemorate a link between that location and a famous person, event, or former building on the site, serving as a historical marker. The term i ...

to Thomas Clarkson has been erected in his memory by the Wisbech Society and is part of the town trail.

*In 1996, a tablet was dedicated to Clarkson's memory in Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an historic, mainly Gothic church in the City of Westminster, London, England, just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is one of the United ...

, near the tomb of William Wilberforce

William Wilberforce (24 August 175929 July 1833) was a British politician, philanthropist and leader of the movement to abolish the slave trade. A native of Kingston upon Hull, Yorkshire, he began his political career in 1780, eventually becom ...

.

*Several other roads in the United Kingdom are named after him, for example in Hull, Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a university city and the county town in Cambridgeshire, England. It is located on the River Cam approximately north of London. As of the 2021 United Kingdom census, the population of Cambridge was 145,700. Cambridge bec ...

and Ipswich

Ipswich () is a port town and borough in Suffolk, England, of which it is the county town. The town is located in East Anglia about away from the mouth of the River Orwell and the North Sea. Ipswich is both on the Great Eastern Main Line r ...

.

*A descendant, Canon John Clarkson, continues in his footsteps as one of the leaders of the Anti-Slavery Society.

*In July 2010, the Church of England Synod The General Synod is the title of the governing body of some church organizations. Anglican Communion

The General Synod of the Church of England, which was established in 1970 replacing the Church Assembly, is the legislative body of the Church of ...

added Clarkson with Equiano and Wilberforce to the list of people to be honoured with a Lesser Festival Lesser Festivals are a type of observance in the Anglican Communion, including the Church of England, considered to be less significant than a Principal Feast, Principal Holy Day, or Festival, but more significant than a Commemoration. Whereas Prin ...

on 30 July in the Church's calendar of saints. An initial celebration was held in Playford Church on 30 July 2010.

Representation in other media

*The poetWilliam Wordsworth

William Wordsworth (7 April 177023 April 1850) was an English Romantic poet who, with Samuel Taylor Coleridge, helped to launch the Romantic Age in English literature with their joint publication '' Lyrical Ballads'' (1798).

Wordsworth's ' ...

wrote a sonnet to Clarkson:

Sonnet, To Thomas Clarkson,

On the final passing of the Bill for the Abolition of the Slave Trade, March 1807.

:'' Clarkson! it was an obstinate Hill to climb:''

:''How toilsome, nay how dire it was, by Thee''

:''Is known,—by none, perhaps, so feelingly;''

:''But Thou, who, starting in thy fervent prime,''

:''Didst first lead forth this pilgrimage sublime,''

:''Hast heard the constant Voice its charge repeat,''

:''Which, out of thy young heart's oracular seat,''

:''First roused thee.—O true yoke-fellow of Time''

:''With unabating effort, see, the palm''

:''Is won, and by all Nations shall be worn!''

:''The bloody Writing is for ever torn,''

:''And Thou henceforth wilt have a good Man's calm,''

:''A great Man's happiness; thy zeal shall find''

:''Repose at length, firm Friend of human kind!''

:::::William Wordsworth

*A posthumous poetical illustration by Letitia Elizabeth Landon

Letitia Elizabeth Landon (14 August 1802 – 15 October 1838) was an English poet and novelist, better known by her initials L.E.L.

The writings of Landon are transitional between Romanticism and the Victorian Age. Her first major breakthrough ...

on an engraving of a painting of Clarkson by S. Lane dwells on his achievements.

*In the 2006 film about the abolition of the slave trade, ''Amazing Grace

"Amazing Grace" is a Christian hymn published in 1779 with words written in 1772 by English Anglican clergyman and poet John Newton (1725–1807). It is an immensely popular hymn, particularly in the United States, where it is used for both ...

'', Clarkson was played by the British actor Rufus Sewell

Rufus Frederik Sewell (; born 29 October 1967) is a British film and stage actor. In film, he has appeared in '' Carrington'' (1995), '' ''Hamlet' (1996), ''Dangerous Beauty'' (1998), '' Dark City'' (1998), '' A Knight's Tale ''(2001), '' Th ...

.

See also

* The Clapham Sect * List of Abolitionist Forerunners (Thomas Clarkson)References

Further reading

* Barker, G.F.R. "Thomas Clarkson", '' Dictionary of National Biography'' (Oxford University Press, 1887) * Brogan, Hugh. "Thomas Clarkson", ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' (Oxford: University Press, 2005) * Carey, Brycchan. ''British Abolitionism and the Rhetoric of Sensibility: Writing, Sentiment, and Slavery, 1760–1807'' (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005). 131–37. * Gifford, Zerbanoo, ''Thomas Clarkson and the Campaign Against the Slave Trade'' (Anti-Slavery International, 1996) - used in events marking the bi-centenary in 2007 of the abolition of the transatlantic slave trade in theBritish Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts esta ...

* Hochschild, Adam. ''Bury the Chains, The British Struggle to Abolish Slavery'' (Basingstoke: Pan Macmillan, 2005)

* Meier, Helmut. ''Thomas Clarkson: 'Moral Steam Engine' or False Prophet? A Critical Approach to Three of his Antislavery Essays.'' (Stuttgart: Ibidem, 2007).

*

* Rodriguez, Junius P., ed. ''Encyclopedia of Emancipation and Abolition in the Transatlantic World''. (Armonk, New York: M. E. Sharpe, 2007)

* Wilson, Ellen Gibson. ''Thomas Clarkson: A Biography'' (Macmillan, 1989)

* Wilson, Ellen Gibson. ''The Clarksons of Wisbech and the abolition of the slave trade'' (Wisbech Society, 1992)

External links

Thomas Clarkson website

Ely Cathedral

(Part of his British Abolitionists project)

Teaching resources about Slavery and Abolition on blackhistory4schools.com

* *

Works by Thomas Clarkson at the online library of liberty

The Louverture Project

Thomas Clarkson �

Thoughts on The Haitian Revolution

Excerpt from an 1823 Clarkson book.

Parliament & The British Slave Trade 1600–1807

Wisbech & Fenland Museum, whose collection includes the Clarkson Chest.

Thomas Clarkson Community College

The Abolition Project website

Bristol Historical Society *

''Report of the Brown University Steering Committee on Slavery and Justice''

study of relationship of university to the slave trade

Clarkson"

the life of Thomas Clarkson, The Wisbech Society and Preservation Trust.

"The History of the Rise, Progress, and Accomplishment of the Abolition of the African Slave Trade"

Thomas Clarkson manuscript, held by Haverford College {{DEFAULTSORT:Clarkson, Thomas 1760 births 1846 deaths Alumni of St John's College, Cambridge 18th-century Anglican deacons Anglican saints Burials in Suffolk Christian abolitionists English abolitionists English Christian pacifists History of Sierra Leone People educated at Wisbech Grammar School People educated at St Paul's School, London People from Suffolk Coastal (district) People from Wisbech Sierra Leone Creole history