Thomas Brennan (Irish Land League) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

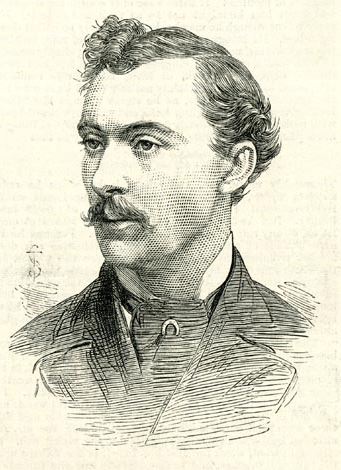

Thomas Brennan (28 July 1853 – 19 December 1912) was an Irish republican activist, agrarian

The three men fervently advocated for widespread agitation in the west of Ireland, where the conditions of

The three men fervently advocated for widespread agitation in the west of Ireland, where the conditions of

Obituary in ''The Cork Examiner'', December 24 1912

radical

Radical may refer to:

Politics and ideology Politics

*Radical politics, the political intent of fundamental societal change

*Radicalism (historical), the Radical Movement that began in late 18th century Britain and spread to continental Europe and ...

and co-founder and joint-secretary of the Irish National Land League

The Irish National Land League ( Irish: ''Conradh na Talún'') was an Irish political organisation of the late 19th century which sought to help poor tenant farmers. Its primary aim was to abolish landlordism in Ireland and enable tenant farme ...

, and a signatory of the ''No Rent Manifesto

The No Rent Manifesto was a document issued in Ireland on 18 October 1881, by imprisoned leaders of the Irish National Land League calling for a campaign of passive resistance by the entire population of small tenant farmers, by withholding rents ...

''.

Biography

Early life

Thomas was the second child of Patrick Brennan and Catherine Rourke of Yellow Furze, Beauparc, County Meath. Although not much is known of his schooling and early years, he evidently received a high degree of formal education, as illustrated by his knowledge of history and oratory skills which he displayed at a young age. By the age of 18 he was working as aclerk

A clerk is a white-collar worker who conducts general office tasks, or a worker who performs similar sales-related tasks in a retail environment. The responsibilities of clerical workers commonly include record keeping, filing, staffing service c ...

alongside his uncle James Rourke for the Murtagh Bros baking company in Castlebar

Castlebar () is the county town of County Mayo, Ireland. Developing around a 13th century castle of the de Barry family, from which the town got its name, the town now acts as a social and economic focal point for the surrounding hinterland. Wi ...

, County Mayo

County Mayo (; ga, Contae Mhaigh Eo, meaning "Plain of the yew trees") is a county in Ireland. In the West of Ireland, in the province of Connacht, it is named after the village of Mayo, now generally known as Mayo Abbey. Mayo County Counci ...

. He and his uncle both joined the Irish Republican Brotherhood

The Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB; ) was a secret oath-bound fraternal organisation dedicated to the establishment of an "independent democratic republic" in Ireland between 1858 and 1924.McGee, p. 15. Its counterpart in the United States ...

(IRB) in the early 1870s. Brennan, alongside other Fenians based in Connacht

Connacht ( ; ga, Connachta or ), is one of the provinces of Ireland, in the west of Ireland. Until the ninth century it consisted of several independent major Gaelic kingdoms (Uí Fiachrach, Uí Briúin, Uí Maine, Conmhaícne, and Delbhn ...

, successfully campaigned for John O'Connor Power

John O'Connor Power (13 February 1846 – 21 February 1919) was an Irish Fenian and a Home Rule League and Irish Parliamentary Party politician and as MP in the House of Commons of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland represente ...

in the 1874 general election, despite strong opposition to Power's candidacy from the Irish Catholic Church.

Brennan moved to Dublin

Dublin (; , or ) is the capital and largest city of Ireland. On a bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the province of Leinster, bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, a part of the Wicklow Mountains range. At the 2016 cen ...

in 1876 to work at the head office of Murtagh Bros, which had been renamed the North City Milling Company and was one of the largest stock companies in Ireland. The company was led by fellow IRB member Patrick Egan, who appointed Brennan as his secretary. During this time Brennan also became secretary of the Leinster

Leinster ( ; ga, Laighin or ) is one of the provinces of Ireland, situated in the southeast and east of Ireland. The province comprises the ancient Kingdoms of Meath, Leinster and Osraige. Following the 12th-century Norman invasion of Ir ...

IRB, and honorary secretary of the Dublin Mechanics Institute. In January 1878, Brennan organised a homecoming reception for several recently released IRB members, including Michael Davitt

Michael Davitt (25 March 184630 May 1906) was an Irish republican activist for a variety of causes, especially Home Rule and land reform. Following an eviction when he was four years old, Davitt's family migrated to England. He began his caree ...

, who had been imprisoned at Dartmoor

Dartmoor is an upland area in southern Devon, England. The moorland and surrounding land has been protected by National Park status since 1951. Dartmoor National Park covers .

The granite which forms the uplands dates from the Carboniferous P ...

for seven and a half years. Following this, a close friendship developed between Brennan, Egan and Davitt.The Land League

The three men fervently advocated for widespread agitation in the west of Ireland, where the conditions of

The three men fervently advocated for widespread agitation in the west of Ireland, where the conditions of tenant farmer

A tenant farmer is a person ( farmer or farmworker) who resides on land owned by a landlord. Tenant farming is an agricultural production system in which landowners contribute their land and often a measure of operating capital and management ...

s were especially poor, igniting a period of civil-unrest and sporadic violence known as the Land War

The Land War ( ga, Cogadh na Talún) was a period of agrarian agitation in rural Ireland (then wholly part of the United Kingdom) that began in 1879. It may refer specifically to the first and most intense period of agitation between 1879 and 18 ...

s. They organised a large-scale protest at Irishtown, County Mayo, attended by 15,000-20,000 people, on 20 April 1879 during which Brennan was a principal speaker. The protest yielded a reversal of potential evictions and a 20% reduction in rent in the area.

This success spurred Brennan, Davitt and Egan to establish the Land League of Mayo in June 1879. They convened a meeting of Irish nationalists

Irish nationalism is a nationalist political movement which, in its broadest sense, asserts that the people of Ireland should govern Ireland as a sovereign state. Since the mid-19th century, Irish nationalism has largely taken the form of cu ...

at the Imperial Hotel in Castlebar on 21 October 1879 during which the Irish National Land League

The Irish National Land League ( Irish: ''Conradh na Talún'') was an Irish political organisation of the late 19th century which sought to help poor tenant farmers. Its primary aim was to abolish landlordism in Ireland and enable tenant farme ...

was founded. Brennan was appointed a secretary alongside Davitt and Andrew Kettle

Andrew Joseph Kettle (1833–1916) was a leading Irish nationalist politician, progressive farmer, agrarian agitator and founding member of the Irish Land League, known as 'the right-hand man' of Charles Stewart Parnell. He was also a much admi ...

. Prominent Home Rule League

The Home Rule League (1873–1882), sometimes called the Home Rule Party, was an Irish political party which campaigned for home rule for Ireland within the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, until it was replaced by the Irish Parlia ...

MP Charles Stewart Parnell

Charles Stewart Parnell (27 June 1846 – 6 October 1891) was an Irish nationalist politician who served as a Member of Parliament (MP) from 1875 to 1891, also acting as Leader of the Home Rule League from 1880 to 1882 and then Leader of the ...

was chosen as the Land League's first President. From 1879 to 1881 Brennan worked tirelessly within the League's executive and became a familiar face at Land League rallies, where he garnered national attention as an eloquent public speaker. As Parnell attempted to attract more moderate members to the land league, Brennan used his speeches to link the demand for tenant rights with the ultimate demand for complete Irish independence, while also demonstrating radical egalitarian

Egalitarianism (), or equalitarianism, is a school of thought within political philosophy that builds from the concept of social equality, prioritizing it for all people. Egalitarian doctrines are generally characterized by the idea that all hum ...

and socialist views.

Due to their advocacy of non-payment of rent, all senior land league officials were arrested between December 1880 and October 1881 under the Coercion Act

A Coercion Act was an Act of Parliament that gave a legal basis for increased state powers to suppress popular discontent and disorder. The label was applied, especially in Ireland, to acts passed from the 18th to the early 20th century by the I ...

. Brennan was convicted under the Protection of Persons and Property Act on 23 May 1881 and imprisoned at Kilmainham Gaol

Kilmainham Gaol ( ga, Príosún Chill Mhaighneann) is a former prison in Kilmainham, Dublin, Ireland. It is now a museum run by the Office of Public Works, an agency of the Government of Ireland. Many Irish revolutionaries, including the leade ...

. He was a signatory of the ''No Rent Manifesto

The No Rent Manifesto was a document issued in Ireland on 18 October 1881, by imprisoned leaders of the Irish National Land League calling for a campaign of passive resistance by the entire population of small tenant farmers, by withholding rents ...

'' which was issued from Kilmainham on 18 October 1881, calling for a national tenant farmer rent strike

A rent strike is a method of protest commonly employed against large landlords. In a rent strike, a group of tenants come together and agree to refuse to pay their rent ''en masse'' until a specific list of demands is met by the landlord. This c ...

. The Land League was suppressed even further as a result.

In May 1882, Parnell agreed to the Kilmainham Treaty

The Kilmainham Treaty was an informal agreement reached in May 1882 between Liberal British prime minister William Ewart Gladstone and the Irish nationalist leader Charles Stewart Parnell. Whilst in gaol, Parnell moved in April 1882 to make a ...

, in which he withdrew the manifesto and pledged to bring violence to an end in exchange for government leniency on rent owed by over 100,000 Irish tenant farmers. Under this agreement, Parnell and the Land League would return to the parameters of parliamentary and constitutional politics. This approach was strongly opposed by Brennan, who immediately sided with Davitt in continuing to promote land nationalisation

Nationalization (nationalisation in British English) is the process of transforming privately-owned assets into public assets by bringing them under the public ownership of a national government or state. Nationalization usually refers to pri ...

upon his release from prison in June 1882. In order to prevent further fragmentation amongst Irish nationalists, Parnell invited Brennan and Davitt to draft a programme for a new national political organisation to replace the Land League during the summer and autumn of 1882. Whilst the constitution of the new Irish National League

The Irish National League (INL) was a nationalist political party in Ireland. It was founded on 17 October 1882 by Charles Stewart Parnell as the successor to the Irish National Land League after this was suppressed. Whereas the Land League h ...

was being debated, the more radical Irish nationalists continued to propose vigorous actions against the British government and land nationalisation; however, they were overruled by Parnell. By September, Davitt had relented and agreed to substitute land nationalisation for peasant proprietorship. Brennan, ideologically opposed to the new party, effectively retired from politics and left Ireland for the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territo ...

.

Later life and death

He emigrated toNew York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* ...

in late 1882 to work for Patrick Ford's ''Irish World'' newspaper, which had been the largest fund-collector for the Land League and promoted radical views in opposition to Parnell. In March 1883, Brennan moved to Omaha

Omaha ( ) is the largest city in the U.S. state of Nebraska and the county seat of Douglas County. Omaha is in the Midwestern United States on the Missouri River, about north of the mouth of the Platte River. The nation's 39th-largest cit ...

, Nebraska where he led a career as an attorney. He became a well-known lecturer for the Irish National League of America, and he traveled across the US continuing to criticise Parnell and the wider Home Rule movement

Home rule is government of a colony, dependent country, or region by its own citizens. It is thus the power of a part (administrative division) of a state or an external dependent country to exercise such of the state's powers of governance wit ...

as being too centered on Westminster

Westminster is an area of Central London, part of the wider City of Westminster.

The area, which extends from the River Thames to Oxford Street, has many visitor attractions and historic landmarks, including the Palace of Westminster, Bucki ...

, and instead advocated educating the Irish populace in non-violent republicanism. Despite his close contacts with Clan na Gael

Clan na Gael ( ga, label=modern Irish orthography, Clann na nGael, ; "family of the Gaels") was an Irish republican organization in the United States in the late 19th and 20th centuries, successor to the Fenian Brotherhood and a sister org ...

, Brennan opposed the Fenian dynamite campaign

The Fenian dynamite campaign (or Fenian bombing campaign) was a bombing campaign orchestrated by Irish republicans against the British Empire, between the years 1881 and 1885. The campaign was associated with Fenianism; that is to say the Irish ...

of the 1880s on the grounds that it harmed the reputation of the Irish republican movement.

Brennan's former colleague, Patrick Egan, had also emigrated to Nebraska and was running a successful real-estate and insurance brokerage in the nearby city of Lincoln. When Egan was appointed as United States Ambassador to Chile

The following is a list of ambassadors that the United States has sent to Chile. The current title given by the United States State Department to this position is Ambassador Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary.

See also

*Ambassadors of ...

in 1889, Brennan took over his business and managed the company for the remainder of his life.

He died in Omaha, Nebraska on 19 December 1912, and is buried in an unmarked grave at Holy Sepulchre Roman Catholic Cemetery, 4912 Leavenworth Street, Omaha, Nebraska.

Politics and activism

Brennan's address to the crowd at the Tenant Rights meeting at Irishtown,County Mayo

County Mayo (; ga, Contae Mhaigh Eo, meaning "Plain of the yew trees") is a county in Ireland. In the West of Ireland, in the province of Connacht, it is named after the village of Mayo, now generally known as Mayo Abbey. Mayo County Counci ...

on April 20, 1879, that led to the formation of the Land League:

. . . I have read some history, and I find that several countries have from time to time been afflicted with the same land disease as that under which Ireland is now labouring, and although the political doctors applied many remedies, the one that proved effectual was the tearing out, root and branch, of the class that caused the disease. All right-thinking men would deplore the necessity of having recourse in this country to scenes such as have been enacted in other lands, although I for one will not hold up my hands in holy horror at a movement that gave liberty not only to France but to Europe. If excesses were at that time committed, they must be measured by the depth of slavery and ignorance in which the people had been kept, and I trust Irish landlords will in time recognize the fact that it is better for them at least to have this land question settled after the manner of aBrennan in an interview to the ''Irish World'' on 17 June 1882 on the policy of land nationalisation and the ongoing rift between Davitt and Parnell:Stein Stein is a German, Yiddish and Norwegian word meaning "stone" and "pip" or "kernel". It stems from the same Germanic root as the English word stone. It may refer to: Places In Austria * Stein, a neighbourhood of Krems an der Donau, Lower Aus ...or aHardenberg Hardenberg (; nds-nl, Haddenbarreg or '' 'n Arnbarg'') is a city and municipality in the province of Overijssel, Eastern Netherlands. The municipality of Hardenberg has a population of about 60,000, with about 19,000 living in the city. It recei ...than wait for the excesses of a Marat or aRobespierre Maximilien François Marie Isidore de Robespierre (; 6 May 1758 – 28 July 1794) was a French lawyer and statesman who became one of the best-known, influential and controversial figures of the French Revolution. As a member of the Esta ....

I heartily endorse Davitt's actions and speeches since his release. It is necessary to base our fight on the true principles, and that is to nationalise the whole soil of Ireland - that of the town as well as that of the country - by taking what is now paid in rents for the common benefit of the people. When we win the social independence of the people, we shall also win the political independence of the nation.Brennan's address to the Irish National League of America at the

Boston Music Hall

The Boston Music Hall was a concert hall located on Winter Street in Boston, Massachusetts, with an additional entrance on Hamilton Place.

One of the oldest continuously operating theaters in the United States, it was built in 1852 and was the ...

, 9 June 1883, on the "Irish question

The Irish question was the issue debated primarily among the British government from the early 19th century until the 1920s of how to respond to Irish nationalism and the calls for Irish independence.

The phrase came to prominence as a result ...

":

I ask the American people, if the science of good government is to be in accord with the wishes and opinions of the people over whom it governs, what they think of the Government that could only rule over a country of 5,000,000 subjects with the aid of a standing army larger than that which exists in the United States today, a standing army of 30,000 soldiers and police force of 14,000 men, a battalion of spies and detectives who are trained to work themselves into the confidence of the people in order to betray them, a Government, the chief servants of which are the informer and the hangman; a Government of which it has been truly said, its sceptre has been the sword, its diadem the black cap, and its throne the gallows for the last eighty years.

References

Obituary in ''The Cork Examiner'', December 24 1912

Bibliography

* Dunbar Palmer, Norman ''The Irish Land League Crisis''. Yale University Press, 1940 * Janis, Ely M. ''A Greater Ireland: The Land League and Transatlantic Nationalism in Gilded Age America''. The University of Wisconsin Press, 2015 {{DEFAULTSORT:Brennan, Thomas 1853 births 1912 deaths Irish land reform activists Irish republicans People from County Meath Members of the Irish Republican Brotherhood