The Trail of Tears on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Trail of Tears was an

In 1830, a group of Indian nations collectively referred to as the "

In 1830, a group of Indian nations collectively referred to as the "

The Choctaw nation resided in large portions of what are now the U.S. states of

The Choctaw nation resided in large portions of what are now the U.S. states of

As the realization that the Seminoles would resist relocation sank in, Florida began preparing for war. The St. Augustine Militia asked the

As the realization that the Seminoles would resist relocation sank in, Florida began preparing for war. The St. Augustine Militia asked the

After the War of 1812, some Muscogee leaders such as

After the War of 1812, some Muscogee leaders such as

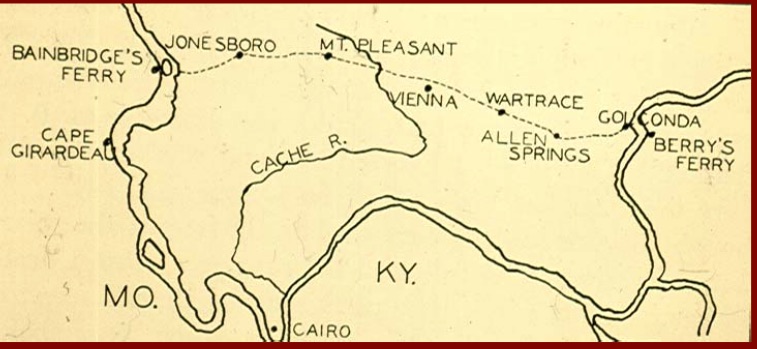

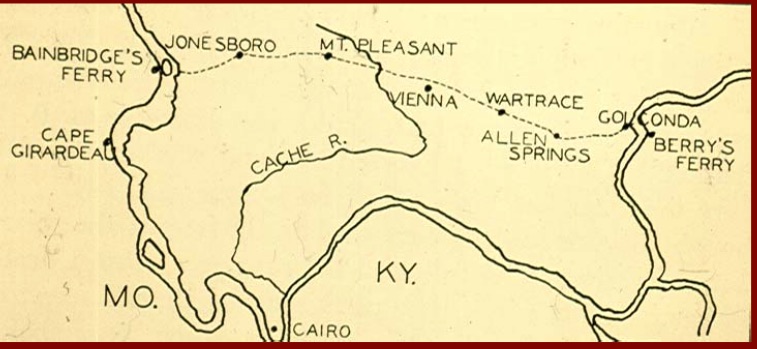

The Chickasaw received financial compensation from the United States for their lands east of the Mississippi River. In 1836, the Chickasaws had reached an agreement to purchase land from the previously removed Choctaws after a bitter five-year debate. They paid the Choctaws $530,000 (equal to $ today) for the westernmost part of the Choctaw land. The first group of Chickasaws moved in 1836 and was led by John M. Millard. The Chickasaws gathered at

The Chickasaw received financial compensation from the United States for their lands east of the Mississippi River. In 1836, the Chickasaws had reached an agreement to purchase land from the previously removed Choctaws after a bitter five-year debate. They paid the Choctaws $530,000 (equal to $ today) for the westernmost part of the Choctaw land. The first group of Chickasaws moved in 1836 and was led by John M. Millard. The Chickasaws gathered at

By 1838, about 2,000 Cherokee had voluntarily relocated from Georgia to

By 1838, about 2,000 Cherokee had voluntarily relocated from Georgia to  Fearing open warfare between federal troops and the Georgia militia, Jackson decided not to enforce Cherokee claims against the state of Georgia. He was already embroiled in a constitutional crisis with

Fearing open warfare between federal troops and the Georgia militia, Jackson decided not to enforce Cherokee claims against the state of Georgia. He was already embroiled in a constitutional crisis with  It eventually took almost three months to cross the on land between the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers. The trek through southern Illinois is where the Cherokee suffered most of their deaths. However a few years before forced removal, some Cherokee who opted to leave their homes voluntarily chose a water-based route through the Tennessee, Ohio and Mississippi rivers. It took only 21 days, but the Cherokee who were forcibly relocated were wary of water travel.

Environmental researchers David Gaines and Jere Krakow outline the "context of the tragic Cherokee relocation" as one predicated on the difference between "Indian regard for the land, and its contrast with the Euro-Americans view of land as property". This divergence in perspective on land, according to sociologists Gregory Hooks and Chad L. Smith, led to the homes of American Indian people "being donated and sold off" by the United States government to "promote the settlement and development of the West," with railroad developers, white settlers, land developers, and mining companies assuming ownership. In American Indian society, according to Colville scholar

It eventually took almost three months to cross the on land between the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers. The trek through southern Illinois is where the Cherokee suffered most of their deaths. However a few years before forced removal, some Cherokee who opted to leave their homes voluntarily chose a water-based route through the Tennessee, Ohio and Mississippi rivers. It took only 21 days, but the Cherokee who were forcibly relocated were wary of water travel.

Environmental researchers David Gaines and Jere Krakow outline the "context of the tragic Cherokee relocation" as one predicated on the difference between "Indian regard for the land, and its contrast with the Euro-Americans view of land as property". This divergence in perspective on land, according to sociologists Gregory Hooks and Chad L. Smith, led to the homes of American Indian people "being donated and sold off" by the United States government to "promote the settlement and development of the West," with railroad developers, white settlers, land developers, and mining companies assuming ownership. In American Indian society, according to Colville scholar

In 1987, about of trails were authorized by federal law to mark the removal of 17 detachments of the Cherokee people. Called the Trail of Tears

In 1987, about of trails were authorized by federal law to mark the removal of 17 detachments of the Cherokee people. Called the Trail of Tears

Trail of Tears National Historic Trail (U.S. National Park Service)

Seminole Tribe of Florida History: Indian Resistance and Removal

Cherokee Heritage Documentation Center

Cherokee Nation Cultural Resource Center

* ttp://www.accessgenealogy.com/native/trail_of_tears.htm Trail of Tears Roll Access genealogy

Trail of Tears

historical marker {{Authority control Cherokee Nation (1794–1907) Forced marches Forced migrations of Native Americans in the United States History of Georgia (U.S. state) History of Kentucky History of Missouri History of North Carolina Military history of the United States National Historic Trails of the United States Native American history Native American history of Alabama Pre-statehood history of Arkansas Pre-statehood history of Oklahoma Chickasaw Seminole tribe American frontier Muscogee Articles containing video clips Politically motivated migrations

ethnic cleansing

Ethnic cleansing is the systematic forced removal of ethnic, racial, and religious groups from a given area, with the intent of making a region ethnically homogeneous. Along with direct removal, extermination, deportation or population transfer ...

and forced displacement

Forced displacement (also forced migration) is an involuntary or coerced movement of a person or people away from their home or home region. The UNHCR defines 'forced displacement' as follows: displaced "as a result of persecution, conflict, ...

of approximately 60,000 people of the "Five Civilized Tribes

The term Five Civilized Tribes was applied by European Americans in the colonial and early federal period in the history of the United States to the five major Native American nations in the Southeast—the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek ...

" between 1830 and 1850 by the United States government

The federal government of the United States (U.S. federal government or U.S. government) is the national government of the United States, a federal republic located primarily in North America, composed of 50 states, a city within a feder ...

. As part of the Indian removal

Indian removal was the United States government policy of forced displacement of self-governing tribes of Native Americans from their ancestral homelands in the eastern United States to lands west of the Mississippi Riverspecifically, to a ...

, members of the Cherokee

The Cherokee (; chr, ᎠᏂᏴᏫᏯᎢ, translit=Aniyvwiyaʔi or Anigiduwagi, or chr, ᏣᎳᎩ, links=no, translit=Tsalagi) are one of the indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands of the United States. Prior to the 18th century, th ...

, Muscogee

The Muscogee, also known as the Mvskoke, Muscogee Creek, and the Muscogee Creek Confederacy ( in the Muscogee language), are a group of related indigenous (Native American) peoples of the Southeastern WoodlandsSeminole

The Seminole are a Native American people who developed in Florida in the 18th century. Today, they live in Oklahoma and Florida, and comprise three federally recognized tribes: the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma, the Seminole Tribe of Florida, ...

, Chickasaw

The Chickasaw ( ) are an indigenous people of the Southeastern Woodlands. Their traditional territory was in the Southeastern United States of Mississippi, Alabama, and Tennessee as well in southwestern Kentucky. Their language is classif ...

, and Choctaw

The Choctaw (in the Choctaw language, Chahta) are a Native American people originally based in the Southeastern Woodlands, in what is now Alabama and Mississippi. Their Choctaw language is a Western Muskogean language. Today, Choctaw people are ...

nations were forcibly removed from their ancestral homelands in the Southeastern United States

The Southeastern United States, also referred to as the American Southeast or simply the Southeast, is a geographical List of regions in the United States, region of the United States. It is located broadly on the eastern portion of the south ...

to newly designated Indian Territory

The Indian Territory and the Indian Territories are terms that generally described an evolving land area set aside by the United States Government for the relocation of Native Americans who held aboriginal title to their land as a sovereign ...

west of the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the List of longest rivers of the United States (by main stem), second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest Drainage system (geomorphology), drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson B ...

after the passage of the Indian Removal Act

The Indian Removal Act was signed into law on May 28, 1830, by United States President Andrew Jackson. The law, as described by Congress, provided "for an exchange of lands with the Indians residing in any of the states or territories, and for ...

in 1830. The Cherokee removal

Cherokee removal, part of the Trail of Tears, refers to the forced relocation between 1836 and 1839 of an estimated 16,000 members of the Cherokee Nation and 1,000–2,000 of their slaves; from their lands in Georgia, South Carolina, North Carol ...

in 1838 (the last forced removal east of the Mississippi) was brought on by the discovery of gold near Dahlonega, Georgia

The city of Dahlonega () is the county seat of Lumpkin County, Georgia, United States. As of the 2010 census, the city had a population of 5,242, and in 2018 the population was estimated to be 6,884.

Dahlonega is located at the north end of ...

, in 1828, resulting in the Georgia Gold Rush

The Georgia Gold Rush was the second significant gold rush in the United States and the first in Georgia, and overshadowed the previous rush in North Carolina. It started in 1829 in present-day Lumpkin County near the county seat, Dahlonega, a ...

.

The relocated peoples suffered from exposure, disease, and starvation while en route to their newly designated Indian reserve. Thousands died from disease before reaching their destinations or shortly after. Some historians have said that the event constituted a genocide

Genocide is the intentional destruction of a people—usually defined as an ethnic, national, racial, or religious group—in whole or in part. Raphael Lemkin coined the term in 1944, combining the Greek word (, "race, people") with the ...

, although this label has been rejected by others and remains a matter of debate.

Overview

In 1830, a group of Indian nations collectively referred to as the "

In 1830, a group of Indian nations collectively referred to as the "Five Civilized Tribes

The term Five Civilized Tribes was applied by European Americans in the colonial and early federal period in the history of the United States to the five major Native American nations in the Southeast—the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek ...

" (the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Muscogee, and Seminole nations), were living autonomously in what would later be termed the American Deep South

The Deep South or the Lower South is a cultural and geographic subregion in the Southern United States. The term was first used to describe the states most dependent on plantations and slavery prior to the American Civil War. Following the wa ...

. The process of cultural transformation from their traditional way of life towards a white American

White Americans are Americans who identify as and are perceived to be white people. This group constitutes the majority of the people in the United States. As of the 2020 Census, 61.6%, or 204,277,273 people, were white alone. This represented ...

way of life as proposed by George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of ...

and Henry Knox

Henry Knox (July 25, 1750 – October 25, 1806), a Founding Father of the United States, was a senior general of the Continental Army during the Revolutionary War, serving as chief of artillery in most of Washington's campaigns. Following th ...

was gaining momentum, especially among the Cherokee and Choctaw.

American settlers had been pressuring the federal government to remove Indians from the Southeast; many settlers were encroaching on Indian lands, while others wanted more land made available to the settlers. Although the effort was vehemently opposed by some, including U.S. Congressman Davy Crockett

David Crockett (August 17, 1786 – March 6, 1836) was an American folk hero, frontiersman, soldier, and politician. He is often referred to in popular culture as the "King of the Wild Frontier". He represented Tennessee in the U.S. House of ...

of Tennessee

Tennessee ( , ), officially the State of Tennessee, is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. Tennessee is the List of U.S. states and territories by area, 36th-largest by ...

, President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

* President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ...

Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was an American lawyer, planter, general, and statesman who served as the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before being elected to the presidency, he gained fame as ...

was able to gain Congressional passage of the Indian Removal Act

The Indian Removal Act was signed into law on May 28, 1830, by United States President Andrew Jackson. The law, as described by Congress, provided "for an exchange of lands with the Indians residing in any of the states or territories, and for ...

of 1830, which authorized the government to extinguish any Indian title to land claims in the Southeast.

In 1831, the Choctaw became the first Nation to be removed, and their removal served as the model for all future relocations. After two wars, many Seminoles were removed in 1832. The Creek removal followed in 1834, the Chickasaw in 1837, and lastly the Cherokee in 1838. Some managed to evade the removals, however, and remained in their ancestral homelands; some Choctaw still reside in Mississippi, Creek in Alabama and Florida, Cherokee in North Carolina

North Carolina () is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. The state is the List of U.S. states and territories by area, 28th largest and List of states and territories of the United ...

, and Seminole in Florida. A small group of Seminole, fewer than 500, evaded forced removal; the modern Seminole Nation of Florida is descended from these individuals. A small number of non-Indians who lived with the nations, including over 4,000 slaves and others of African descent such as spouses or Freedmen

A freedman or freedwoman is a formerly enslaved person who has been released from slavery, usually by legal means. Historically, enslaved people were freed by manumission (granted freedom by their captor-owners), emancipation (granted freedom ...

, also accompanied the Indians on the trek westward. By 1837, 46,000 Indians from the southeastern states had been removed from their homelands, thereby opening for white settlement. When the "Five Tribes" arrived in Indian Territory, "they followed their physical appropriation of Plains Indians' land with an erasure of their predecessor's history", and "perpetuated the idea that they had found an undeveloped 'wilderness" when they arrived" in an attempt to appeal to white American values by participating in the settler colonial process themselves. Other Indian nations, such as the Quapaws and Osages had moved to Indian Territory before the "Five Tribes" and saw them as intruders.

Historical background

Before 1838, the fixed boundaries of these autonomousIndian nations

This is a list of Indian reservations and other tribal homelands in the United States. In Canada, the Indian reserve is a similar institution.

Federally recognized reservations

There are 326 Indian Reservations in the United States. Most of t ...

, comprising large areas of the United States, were subject to continual cession and annexation, in part due to pressure from squatters and the threat of military force in the newly declared U.S. territories—federally administered regions whose boundaries supervened upon the Indian treaty claims. As these territories became U.S. state

In the United States, a state is a constituent political entity, of which there are 50. Bound together in a political union, each state holds governmental jurisdiction over a separate and defined geographic territory where it shares its sove ...

s, state governments sought to dissolve the boundaries of the Indian nations within their borders, which were independent of state jurisdiction, and to expropriate the land therein. These pressures were exacerbated by U.S. population growth and the expansion of slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

in the South, with the rapid development of cotton cultivation in the uplands after the invention of the cotton gin

A cotton gin—meaning "cotton engine"—is a machine that quickly and easily separates cotton fibers from their seeds, enabling much greater productivity than manual cotton separation.. Reprinted by McGraw-Hill, New York and London, 1926 (); a ...

by Eli Whitney

Eli Whitney Jr. (December 8, 1765January 8, 1825) was an American inventor, widely known for inventing the cotton gin, one of the key inventions of the Industrial Revolution that shaped the economy of the Antebellum South.

Although Whitney hi ...

.

Many people of the southeastern Indian nations had become economically integrated into the economy of the region. This included the plantation economy and the possession of slaves, who were also forcibly relocated during the removal.

Prior to Jackson's presidency, removal policy was already in place and justified by the myth of the "vanishing Indian". Historian Jeffrey Ostler explains that "Scholars have exposed how the discourse of the vanishing Indian was an ideology that made declining Indigenous American populations seem to be an inevitable consequence of natural processes and so allowed Americans to evade moral responsibility for their destructive choices". Despite the common association of Andrew Jackson and the Trail of Tears, ideas for Removal began prior to Jackson's presidency. Ostler explains, "A singular focus on Jackson obscures the fact that he did not invent the idea of removal…Months after the passage of the Removal Act, Jackson described the legislation as the 'happy consummation' of a policy 'pursued for nearly 30 years. James Fenimore Cooper

James Fenimore Cooper (September 15, 1789 – September 14, 1851) was an American writer of the first half of the 19th century, whose historical romances depicting colonist and Indigenous characters from the 17th to the 19th centuries brought ...

was also a key component of the maintenance of the "vanishing Indian" myth. This vanishing narrative can be seen as existing prior to the Trail of Tears through Cooper's novel ''The Last of the Mohicans

''The Last of the Mohicans: A Narrative of 1757'' is a historical romance written by James Fenimore Cooper in 1826.

It is the second book of the '' Leatherstocking Tales'' pentalogy and the best known to contemporary audiences. '' The Pathfinde ...

''. Scholar and author Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz

Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz (born September 10, 1938) is an American historian, writer, and activist, known for her 2014 book ''An Indigenous Peoples' History of the United States''.

Early life and education

Born in San Antonio, Texas, in 1938 to ...

shows that:

Jackson's role

Although Jackson was not the sole, or original, architect of Removal policy, his contributions were influential in its trajectory. Jackson's support for the removal of the Indians began at least a decade before his presidency. Indian removal was Jackson's top legislative priority upon taking office. After being elected president, he wrote in his first address to Congress: "The emigration should be voluntary, for it would be as cruel as unjust to compel the aborigines to abandon the graves of their fathers and seek a home in a distant land. But they should be distinctly informed that if they remain within the limits of the States they must be subject to their laws. In return for their obedience as individuals they will without doubt be protected in the enjoyment of those possessions which they have improved by their industry". The prioritization of American Indian removal and his violent past created a sense of restlessness among U.S. territories. During his presidency, "the United States made eighty-six treaties with twenty-six American Indian nations between New York and the Mississippi, all of them forcing land cessions, including removals". In a speech regarding Indian removal, Jackson said, The removals, conducted under both PresidentsJackson

Jackson may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Jackson (name), including a list of people and fictional characters with the surname or given name

Places

Australia

* Jackson, Queensland, a town in the Maranoa Region

* Jackson North, Qu ...

and Van Buren, followed the Indian Removal Act

The Indian Removal Act was signed into law on May 28, 1830, by United States President Andrew Jackson. The law, as described by Congress, provided "for an exchange of lands with the Indians residing in any of the states or territories, and for ...

of 1830, which provided the president with powers to exchange land with Indian nations and provide infrastructure improvements on the existing lands. The law also gave the president power to pay for transportation costs to the West, should the nations willingly choose to relocate. The law did not, however, allow the president to force Indian nations to move west without a mutually agreed-upon treaty. Referring to the Indian Removal Act, Martin Van Buren, Jackson's vice president

A vice president, also director in British English, is an officer in government or business who is below the president (chief executive officer) in rank. It can also refer to executive vice presidents, signifying that the vice president is on ...

and successor, is quoted as saying "There was no measure, in the whole course of ackson'sadministration, of which he was more exclusively the author than this."

According to historian Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz, Jackson's intentions were outwardly violent. Dunbar-Ortiz claims that Jackson believed in "bleeding enemies to give them their senses" on his quest to "serve the goal of U.S. expansion". According to her, American Indians presented an obstacle to the fulfillment of Manifest Destiny, in his mind. Throughout his military career, according to historian Amy H. Sturgis, "Jackson earned and emphasized his reputation as an 'Indian fighter', a man who believed creating fear in the native population was more desirable than cultivating friendship". In a message to Congress on the eve of Indian Removal, December 6, 1830, Jackson wrote that removal "will relieve the whole State of Mississippi and the western part of Alabama of Indian occupancy, and enable those States to advance rapidly in population, wealth, and power. It will separate the Indians from immediate contact with settlements of whites." In this way, Sturgis has argued that Jackson demarcated the Indian population as an "obstacle" to national success. Sturgis writes that Jackson's removal policies were met with pushback from respectable social figures and that "many leaders of Jacksonian reform movements were particularly disturbed by U.S policy toward American Indians". Among these opponents were women's advocate and founder of the American Woman's Educational Association Catherine Beecher

Catharine Esther Beecher (September 6, 1800 – May 12, 1878) was an American educator known for her forthright opinions on female education as well as her vehement support of the many benefits of the incorporation of kindergarten into children's ...

and politician Davy Crockett

David Crockett (August 17, 1786 – March 6, 1836) was an American folk hero, frontiersman, soldier, and politician. He is often referred to in popular culture as the "King of the Wild Frontier". He represented Tennessee in the U.S. House of ...

.

Historian Francis Paul Prucha

Francis Paul Prucha (January 4, 1921 – July 30, 2015) was an American historian, professor ''emeritus'' of history at Marquette University, and specialist in the relationship between the United States and Native Americans. His work, ''The Great ...

, on the other hand, writes that these assessments were put forward by Jackson's political opponents and that Jackson had benevolent intentions. According to him, Jackson's critics have been too harsh, if not wrong. He states that Jackson never developed a doctrinaire anti-Indian attitude and that his dominant goal was to preserve the security and well-being of the United States and its Indian and white inhabitants. Corrobating Prucha's interpretation, historian Robert V. Remini

Robert Vincent Remini (July 17, 1921 – March 28, 2013) was an American historian and a professor emeritus at the University of Illinois at Chicago. He wrote numerous books about President Andrew Jackson and the Jacksonian era, most notably a th ...

argues that Jackson never intended for the "monstrous result" of his policy. Remini argues further that had Jackson not orchestrated the removal of the "Five Civilized Tribes

The term Five Civilized Tribes was applied by European Americans in the colonial and early federal period in the history of the United States to the five major Native American nations in the Southeast—the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek ...

" from their ancestral homelands, they would have been totally wiped out.

Treaty of New Echota

Jackson chose to continue with Indian removal, and negotiated theTreaty of New Echota

The Treaty of New Echota was a treaty signed on December 29, 1835, in New Echota, Georgia, by officials of the United States government and representatives of a minority Cherokee political faction, the Treaty Party.

The treaty established ter ...

, on December 29, 1835, which granted the Cherokee two years to move to Indian Territory (modern-day Oklahoma). The Chickasaws and Choctaws had readily accepted and signed treaties with the U.S. government, while the Creeks did so under coercion. The negotiation of the Treaty of New Echota was largely encouraged by Jackson, and it was signed by a minority Cherokee political faction, the Treaty Party, led by Cherokee leader Elias Boudinot

Elias Boudinot ( ; May 2, 1740 – October 24, 1821) was a lawyer and statesman from Elizabeth, New Jersey who was a delegate to the Continental Congress (more accurately referred to as the Congress of the Confederation) and served as President ...

. However, the treaty was opposed by most of the Cherokee people, as it was not approved by the Cherokee National Council, and it was not signed by Principal Chief John Ross. The Cherokee National Council submitted a petition, signed by thousands of Cherokee citizens, urging Congress to void the agreement in February 1836. Despite this opposition, the Senate ratified the treaty on March 1836, and the Treaty of New Echota thus became the legal basis for the Trail of Tears. Only a fraction of the Cherokees left voluntarily. The U.S. government, with assistance from state militias, forced most of the remaining Cherokees west in 1838. The Cherokees were temporarily remanded in camps in eastern Tennessee. In November, the Cherokee were broken into groups of around 1,000 each and began the journey west. They endured heavy rains, snow, and freezing temperatures.

When the Cherokee negotiated the Treaty of New Echota, they exchanged all their land east of the Mississippi for land in modern Oklahoma and a $5 million payment from the federal government. Many Cherokee felt betrayed that their leadership accepted the deal, and over 16,000 Cherokee signed a petition to prevent the passage of the treaty. By the end of the decade in 1840, tens of thousands of Cherokee and other Indian nations had been removed from their land east of the Mississippi River. The Creek, Choctaw, Seminole, and Chicksaw were also relocated under the Indian Removal Act of 1830. One Choctaw leader portrayed the removal as "A Trail of Tears and Deaths", a devastating event that removed most of the Indian population of the southeastern United States from their traditional homelands.

Terminology

Theforced relocation

Forced displacement (also forced migration) is an involuntary or coerced movement of a person or people away from their home or home region. The UNHCR defines 'forced displacement' as follows: displaced "as a result of persecution, conflict, g ...

s and ethnic cleansing

Ethnic cleansing is the systematic forced removal of ethnic, racial, and religious groups from a given area, with the intent of making a region ethnically homogeneous. Along with direct removal, extermination, deportation or population transfer ...

s of the Indian nations have sometimes been referred to as "death march

A death march is a forced march of prisoners of war or other captives or deportees in which individuals are left to die along the way. It is distinguished in this way from simple prisoner transport via foot march. Article 19 of the Geneva Conven ...

es", in particular when referring to the Cherokee march across the Midwest in 1838, which occurred via a predominantly land route.

Indians who had the means initially provided for their own removal. Contingents that were led by conductors from the U.S. Army included those led by Edward Deas, who was claimed to be a sympathizer for the Cherokee plight. The largest death toll from the Cherokee forced relocation comes from the period after the May 23, 1838 deadline. This was at the point when the remaining Cherokee were rounded up into camps and placed into large groups, often over 700 in size (larger than the populations of Little Rock

( The "Little Rock")

, government_type = Council-manager

, leader_title = Mayor

, leader_name = Frank Scott Jr.

, leader_party = D

, leader_title2 = Council

, leader_name2 ...

or Memphis

Memphis most commonly refers to:

* Memphis, Egypt, a former capital of ancient Egypt

* Memphis, Tennessee, a major American city

Memphis may also refer to:

Places United States

* Memphis, Alabama

* Memphis, Florida

* Memphis, Indiana

* Memp ...

at that time). Communicable diseases spread quickly through these closely quartered groups, killing many. These groups were among the last to move, but following the same routes the others had taken; the areas they were going through had been depleted of supplies due to the vast numbers that had gone before them. The marchers were subject to extortion and violence along the route. In addition, these final contingents were forced to set out during the hottest and coldest months of the year, killing many. Exposure to the elements, disease, starvation, harassment by local frontiersmen, and insufficient rations similarly killed up to one-third of the Choctaw and other nations on the march.

There exists some debate among historians and the affected nations as to whether the term "Trail of Tears" should be used to refer to the entire history of forced relocations from the Eastern United States into Indian Territory

The Indian Territory and the Indian Territories are terms that generally described an evolving land area set aside by the United States Government for the relocation of Native Americans who held aboriginal title to their land as a sovereign ...

, to the relocations of specifically the Five Civilized Tribes, to the route of the march, or to specific marches in which the remaining holdouts from each area were rounded up.

Classification as genocide

There has been debate among scholars about whether Indian removal and the Trail of Tears were genocidal acts. Historian Jeffrey Ostler argues that even when genocide was not unequivocally carried out, the threat of genocide was used to ensure Natives' compliance with removal policies, and concludes that, "In its outcome and in the means used to gain compliance, the policy had genocidal dimensions."Patrick Wolfe

Patrick Wolfe (1949 – 18 February 2016) was an Australian historian and scholar who made significant contributions to several academic fields, including anthropology, genocide studies, Indigenous studies, and the historiography of race, colon ...

argues that settler colonialism

Settler colonialism is a structure that perpetuates the elimination of Indigenous people and cultures to replace them with a settler society. Some, but not all, scholars argue that settler colonialism is inherently genocidal. It may be enacted ...

and genocide are interrelated but should be distinguished from each other, writing that settler colonialism is "more than the summary liquidation of Indigenous people, though it includes that." Wolfe describes the assimilation of Indigenous people who escaped relocation (and particularly their abandonment of collectivity) as a form of cultural genocide

Cultural genocide or cultural cleansing is a concept which was proposed by lawyer Raphael Lemkin in 1944 as a component of genocide. Though the precise definition of ''cultural genocide'' remains contested, the Armenian Genocide Museum defines i ...

, though he emphasises that cultural genocide is “the real thing” in that it resulted in large numbers of deaths. The Trail of Tears was thus a settler-colonial ''replacement'' of Indigenous people and culture in addition to a genocidal mass-killing according to Wolfe.

Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz

Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz (born September 10, 1938) is an American historian, writer, and activist, known for her 2014 book ''An Indigenous Peoples' History of the United States''.

Early life and education

Born in San Antonio, Texas, in 1938 to ...

describes the policy as genocide, quoting Cherokee principal chief Wilma Mankiller:The fledgling United States government's method of dealing with native people—a process which then included systematic genocide, property theft, and total subjugation—reached its nadir in 1830 under the federal policy of President Andrew Jackson.Mankiller emphasises that Jackson's policies were the natural extension of earlier policies of the Jefferson administration during territorial expansion that she also considers genocidal.

Dina Gilio-Whitaker

Dina Gilio-Whitaker is an American academic, journalist and author, who studies Native Americans in the United States, decolonization and environmental justice. She is a member of the Colville Confederated Tribes. In 2019, she published ''As Long ...

, in '' As Long as Grass Grows'', describes the Trail of Tears and the Diné long walk as structural

A structure is an arrangement and organization of interrelated elements in a material object or system, or the object or system so organized. Material structures include man-made objects such as buildings and machines and natural objects such ...

genocide, because they destroyed Native relations to land, one another, and nonhuman beings which imperiled their culture, life, and history. According to her, these are ongoing actions that constitute both cultural and physical genocide.

Colonial historian Daniel Blake Smith disagrees with the usage of the term genocide, adding that "no one wanted, let alone planned for, Cherokees to die in the forced removal out West". Historian Justin D. Murphy argues that:

Historian Sean Wilentz

Robert Sean Wilentz (; born February 20, 1951) is the George Henry Davis 1886 Professor of American History at Princeton University, where he has taught since 1979. His primary research interests include U.S. social and political history in the ...

writes that some critics who label Indian removal as genocide view Jacksonian democracy as a "momentous transition from the ethical community upheld by antiremoval men", and says this view is a caricature of US history that "turns tragedy into melodrama, exaggerates parts at the expense of the whole, and sacrifices nuance for sharpness". Historian and biographer Robert V. Remini

Robert Vincent Remini (July 17, 1921 – March 28, 2013) was an American historian and a professor emeritus at the University of Illinois at Chicago. He wrote numerous books about President Andrew Jackson and the Jacksonian era, most notably a th ...

wrote that Jackson's policy on Native Americans was based on good intentions and was far from genocide. Historian Donald B. Cole Donald Barnard Cole (March 31, 1922 – October 5, 2013), born in Lawrence, Massachusetts, was professor emeritus at Phillips Exeter Academy, New Hampshire, and the author of books on early American history, including ''Martin Van Buren and the Amer ...

, too, argues that it is difficult to find evidence of a conscious desire for genocide in Jackson's policy on Native Americans, but dismisses the idea that Jackson was motivated by the welfare of Native Americans.

Legal background

The establishment of theIndian Territory

The Indian Territory and the Indian Territories are terms that generally described an evolving land area set aside by the United States Government for the relocation of Native Americans who held aboriginal title to their land as a sovereign ...

and the extinguishing of Indian land claims east of the Mississippi by the Indian Removal Act anticipated the U.S. Indian reservation

An Indian reservation is an area of land held and governed by a federally recognized Native American tribal nation whose government is accountable to the United States Bureau of Indian Affairs and not to the state government in which it ...

system, which was imposed on remaining Indian lands later in the 19th century.

The statutory argument for Indian sovereignty persisted until the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in ''Cherokee Nation v. Georgia

''Cherokee Nation v. Georgia'', 30 U.S. (5 Pet.) 1 (1831), was a United States Supreme Court case. The Cherokee Nation sought a federal injunction against laws passed by the U.S. state of Georgia depriving them of rights within its boundaries, but ...

'' (1831), that the Cherokee were not a sovereign and independent nation, and therefore not entitled to a hearing before the court. In the years after the Indian Removal Act, the Cherokee filed several lawsuits regarding conflicts with the state of Georgia. Some of these cases reached the Supreme Court, the most influential being ''Worcester v. Georgia

''Worcester v. Georgia'', 31 U.S. (6 Pet.) 515 (1832), was a landmark case in which the United States Supreme Court vacated the conviction of Samuel Worcester and held that the Georgia criminal statute that prohibited non-Native Americans from bei ...

'' (1832). Samuel Worcester and other non-Indians were convicted by Georgia law for residing in Cherokee territory in the state of Georgia without a license. Worcester was sentenced to prison for four years and appealed the ruling, arguing that this sentence violated treaties made between Indian nations and the United States federal government by imposing state laws on Cherokee lands. The Court ruled in Worcester's favor, declaring that the Cherokee Nation was subject only to federal law and that the Supremacy Clause

The Supremacy Clause of the Constitution of the United States ( Article VI, Clause 2) establishes that the Constitution, federal laws made pursuant to it, and treaties made under its authority, constitute the "supreme Law of the Land", and thu ...

barred legislative interference by the state of Georgia. Chief Justice Marshall argued, "The Cherokee nation, then, is a distinct community occupying its own territory in which the laws of Georgia can have no force. The whole intercourse between the United States and this Nation, is, by our constitution and laws, vested in the government of the United States."

The Court did not ask federal marshal

The United States Marshals Service (USMS) is a federal law enforcement agency in the United States. The USMS is a bureau within the U.S. Department of Justice, operating under the direction of the Attorney General, but serves as the enforceme ...

s to carry out the decision. ''Worcester'' thus imposed no obligations on Jackson; there was nothing for him to enforce, although Jackson's' political enemies conspired to find evidence, to be used in the forthcoming political election, to claim that he would refuse to enforce the ''Worcester'' decision. He feared that enforcement would lead to open warfare between federal troops and the Georgia militia, which would compound the ongoing crisis in South Carolina and lead to a broader civil war. Instead, he vigorously negotiated a land exchange treaty with the Cherokee. After this, Jackson's political opponents Henry Clay

Henry Clay Sr. (April 12, 1777June 29, 1852) was an American attorney and statesman who represented Kentucky in both the United States Senate, U.S. Senate and United States House of Representatives, House of Representatives. He was the seven ...

and John Quincy Adams

John Quincy Adams (; July 11, 1767 – February 23, 1848) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, and diarist who served as the sixth president of the United States, from 1825 to 1829. He previously served as the eighth United States ...

, who supported the ''Worcester'' decision, became outraged by Jackson's alleged refusal to uphold Cherokee claims against the state of Georgia. Author and political activist Ralph Waldo Emerson

Ralph Waldo Emerson (May 25, 1803April 27, 1882), who went by his middle name Waldo, was an American essayist, lecturer, philosopher, abolitionist, and poet who led the transcendentalist movement of the mid-19th century. He was seen as a cham ...

wrote an account of Cherokee assimilation into the American culture, declaring his support of the ''Worcester'' decision.

Nevertheless, the actions of the Jackson administration were not isolated because state and federal officials had violated treaties without consequence, often attributed to military exigency, as the members of individual Indian nations were not automatically United States citizens and were rarely given standing in any U.S. court.

While citizenship tests existed for Indians living in newly annexed areas before and after forced relocation, individual U.S. states did not recognize the Indian nations' land claims, only individual title

A title is one or more words used before or after a person's name, in certain contexts. It may signify either generation, an official position, or a professional or academic qualification. In some languages, titles may be inserted between the f ...

under State law, and distinguished between the rights of white and non-white citizens, who often had limited standing in court; and Indian removal

Indian removal was the United States government policy of forced displacement of self-governing tribes of Native Americans from their ancestral homelands in the eastern United States to lands west of the Mississippi Riverspecifically, to a ...

was carried out under U.S. military jurisdiction, often by state militias. As a result, individual Indians who could prove U.S. citizenship were nevertheless displaced from newly annexed areas.

Choctaw removal

The Choctaw nation resided in large portions of what are now the U.S. states of

The Choctaw nation resided in large portions of what are now the U.S. states of Alabama

(We dare defend our rights)

, anthem = " Alabama"

, image_map = Alabama in United States.svg

, seat = Montgomery

, LargestCity = Huntsville

, LargestCounty = Baldwin County

, LargestMetro = Greater Birmingham

, area_total_km2 = 135,7 ...

, Mississippi

Mississippi () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States, bordered to the north by Tennessee; to the east by Alabama; to the south by the Gulf of Mexico; to the southwest by Louisiana; and to the northwest by Arkansas. Miss ...

, and Louisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It is the 20th-smallest by area and the 25th most populous of the 50 U.S. states. Louisiana is bord ...

. After a series of treaties starting in 1801, the Choctaw nation was reduced to . The Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek

The Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek was a treaty which was signed on September 27, 1830, and proclaimed on February 24, 1831, between the Choctaw American Indian tribe and the United States Government. This treaty was the first removal treaty wh ...

ceded the remaining country to the United States and was ratified in early 1831. The removals were only agreed to after a provision in the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek allowed some Choctaw to remain. The Choctaws were the first to sign a removal treaty presented by the federal government. President Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was an American lawyer, planter, general, and statesman who served as the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before being elected to the presidency, he gained fame as ...

wanted strong negotiations with the Choctaws in Mississippi, and the Choctaws seemed much more cooperative than Andrew Jackson had imagined. The treaty provided that the United States would bear the expense of moving their homes and that they had to be removed within two and a half years of the signed treaty. The chief of the Choctaw nation, George W. Harkins, wrote to the citizens of the United States before the removals were to commence:

United States Secretary of War Lewis Cass

Lewis Cass (October 9, 1782June 17, 1866) was an American military officer, politician, and statesman. He represented Michigan in the United States Senate and served in the Cabinets of two U.S. Presidents, Andrew Jackson and James Buchanan. He w ...

appointed George Gaines to manage the removals. Gaines decided to remove Choctaws in three phases starting in November 1831 and ending in 1833. The first groups met at Memphis and Vicksburg, where a harsh winter battered the emigrants with flash floods, sleet, and snow. Initially, the Choctaws were to be transported by wagon but floods halted them. With food running out, the residents of Vicksburg and Memphis were concerned. Five steamboats (the ''Walter Scott'', the ''Brandywine'', the ''Reindeer'', the ''Talma'', and the ''Cleopatra'') would ferry Choctaws to their river-based destinations. The Memphis group traveled up the Arkansas for about to Arkansas Post. There the temperature stayed below freezing for almost a week with the rivers clogged with ice, so there could be no travel for weeks. Food rationing consisted of a handful of boiled corn, one turnip, and two cups of heated water per day. Forty government wagons were sent to Arkansas Post to transport them to Little Rock. When they reached Little Rock, a Choctaw chief referred to their trek as a "''trail of tears and death''". The Vicksburg group was led by an incompetent guide and was lost in the Lake Providence

A lake is an area filled with water, localized in a basin, surrounded by land, and distinct from any river or other outlet that serves to feed or drain the lake. Lakes lie on land and are not part of the ocean, although, like the much larger ...

swamps.

Alexis de Tocqueville

Alexis Charles Henri Clérel, comte de Tocqueville (; 29 July 180516 April 1859), colloquially known as Tocqueville (), was a French aristocrat, diplomat, political scientist, political philosopher and historian. He is best known for his wo ...

, the French philosopher, witnessed the Choctaw removals while in Memphis, Tennessee

Memphis is a city in the U.S. state of Tennessee. It is the seat of Shelby County in the southwest part of the state; it is situated along the Mississippi River. With a population of 633,104 at the 2020 U.S. census, Memphis is the second-mo ...

in 1831:

Nearly 17,000 Choctaws made the move to what would be called Indian Territory

The Indian Territory and the Indian Territories are terms that generally described an evolving land area set aside by the United States Government for the relocation of Native Americans who held aboriginal title to their land as a sovereign ...

and then later Oklahoma

Oklahoma (; Choctaw: ; chr, ᎣᎧᎳᎰᎹ, ''Okalahoma'' ) is a state in the South Central region of the United States, bordered by Texas on the south and west, Kansas on the north, Missouri on the northeast, Arkansas on the east, New ...

. About 2,500–6,000 died along the trail of tears. Approximately 5,000–6,000 Choctaws remained in Mississippi in 1831 after the initial removal efforts. The Choctaws who chose to remain in newly formed Mississippi were subject to legal conflict, harassment, and intimidation. The Choctaws "have had our habitations torn down and burned, our fences destroyed, cattle turned into our fields and we ourselves have been scourged, manacled, fettered and otherwise personally abused, until by such treatment some of our best men have died". The Choctaws in Mississippi were later reformed as the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians

The Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians ( cho, Mississippi Chahta) is one of three federally recognized tribes of Choctaw Native Americans, and the only one in the state of Mississippi. On April 20, 1945, this tribe organized under the Indian R ...

and the removed Choctaws became the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma

The Choctaw Nation (Choctaw: ''Chahta Okla'') is a Native American territory covering about , occupying portions of southeastern Oklahoma in the United States. The Choctaw Nation is the third-largest federally recognized tribe in the United St ...

.

Seminole resistance

The U.S. acquired Florida fromSpain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = '' Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, ...

via the Adams–Onís Treaty

The Adams–Onís Treaty () of 1819, also known as the Transcontinental Treaty, the Florida Purchase Treaty, or the Florida Treaty,Weeks, p.168. was a treaty between the United States and Spain in 1819 that ceded Florida to the U.S. and define ...

and took possession in 1821. In 1832 the Seminoles were called to a meeting at Payne's Landing on the Ocklawaha River. The Treaty of Payne's Landing

The Treaty of Payne's Landing (Treaty with the Seminole, 1832) was an agreement signed on 9 May 1832 between the government of the United States and several chiefs of the Seminole Indians in the Territory of Florida, before it acquired statehood.

...

called for the Seminoles to move west, if the land were found to be suitable. They were to be settled on the Creek reservation and become part of the Creek nation, who considered them deserters; some of the Seminoles had been derived from Creek bands but also from other Indian nations. Those among the nation who once were members of Creek bands did not wish to move west to where they were certain that they would meet death for leaving the main band of Creek Indians. The delegation of seven chiefs who were to inspect the new reservation did not leave Florida until October 1832. After touring the area for several months and conferring with the Creeks who had already settled there, the seven chiefs signed a statement on March 28, 1833, that the new land was acceptable. Upon their return to Florida, however, most of the chiefs renounced the statement, claiming that they had not signed it, or that they had been forced to sign it, and in any case, that they did not have the power to decide for all the Indian nations and bands that resided on the reservation. The villages in the area of the Apalachicola River were more easily persuaded, however, and went west in 1834. On December 28, 1835, a group of Seminoles and blacks ambushed a U.S. Army company marching from Fort Brooke in Tampa to Fort King in Ocala

Ocala ( ) is a city in and the county seat of Marion County within the northern region of Florida, United States. As of the 2020 United States Census, the city's population was 63,591, making it the 54th most populated city in Florida.

Home to ...

, killing all but three of the 110 army troops. This came to be known as the Dade Massacre

The Dade battle (often called the Dade massacre) was an 1835 military defeat for the United States Army. The U.S. was attempting to force the Seminoles to move away from their land in Florida and relocate to Indian Territory (in what would becom ...

.

As the realization that the Seminoles would resist relocation sank in, Florida began preparing for war. The St. Augustine Militia asked the

As the realization that the Seminoles would resist relocation sank in, Florida began preparing for war. The St. Augustine Militia asked the War Department War Department may refer to:

* War Department (United Kingdom)

* United States Department of War (1789–1947)

See also

* War Office, a former department of the British Government

* Ministry of defence

* Ministry of War

* Ministry of Defence

* D ...

for the loan of 500 muskets. Five hundred volunteers were mobilized under Brig. Gen. Richard K. Call. Indian war parties raided farms and settlements, and families fled to forts, large towns, or out of the territory altogether. A war party led by Osceola

Osceola (1804 – January 30, 1838, Asi-yahola in Muscogee language, Creek), named Billy Powell at birth in Alabama, became an influential leader of the Seminole people in Florida. His mother was Muscogee, and his great-grandfather was a S ...

captured a Florida militia supply train, killing eight of its guards and wounding six others. Most of the goods taken were recovered by the militia in another fight a few days later. Sugar plantations along the Atlantic coast south of St. Augustine were destroyed, with many of the slaves on the plantations joining the Seminoles.

Other war chiefs such as Halleck Tustenuggee

Halleck Tustenuggee (also spelled Halek Tustenuggee and Hallock Tustenuggee) (c. 1807 – ?) was a 19th-century Seminole war chief. He fought against the United States government in the Second Seminole War and for the government in the American Ci ...

, Jumper, and Black Seminoles

The Black Seminoles, or Afro-Seminoles are Native American-Africans associated with the Seminole people in Florida and Oklahoma. They are mostly blood descendants of the Seminole people, free Africans, and escaped slaves, who allied with Seminole ...

Abraham and John Horse continued the Seminole resistance against the army. The war ended, after a full decade of fighting, in 1842. The U.S. government is estimated to have spent about $20,000,000 on the war, ($ today). Many Indians were forcibly exiled to Creek lands west of the Mississippi; others retreated into the Everglades. In the end, the government gave up trying to subjugate the Seminole in their Everglades redoubts and left fewer than 500 Seminoles in peace. Other scholars state that at least several hundred Seminoles remained in the Everglades after the Seminole Wars.

As a result of the Seminole Wars, the surviving Seminole band of the Everglades claims to be the only federally recognized Indian nation which never relinquished sovereignty or signed a peace treaty with the United States.

In general the American people tended to view the Indian resistance as unwarranted. An article published by the Virginia ''Enquirer'' on January 26, 1836, called the "Hostilities of the Seminoles", assigned all the blame for the violence that came from the Seminole's resistance to the Seminoles themselves. The article accuses the Indians of not staying true to their word—the promises they supposedly made in the treaties and negotiations from the Indian Removal Act.

Creek dissolution

After the War of 1812, some Muscogee leaders such as

After the War of 1812, some Muscogee leaders such as William McIntosh

William McIntosh (1775 – April 30, 1825),Hoxie, Frederick (1996)pp. 367-369/ref> was also commonly known as ''Tustunnuggee Hutke'' (White Warrior), was one of the most prominent chiefs of the Creek Nation between the turn of the nineteenth ce ...

signed treaties that ceded more land to Georgia. The 1814 signing of the Treaty of Fort Jackson

The Treaty of Fort Jackson (also known as the Treaty with the Creeks, 1814) was signed on August 9, 1814 at Fort Jackson near Wetumpka, Alabama following the defeat of the Red Stick (Upper Creek) resistance by United States allied forces at ...

signaled the end for the Creek Nation and for all Indians in the South. Friendly Creek leaders, like Selocta and Big Warrior, addressed Sharp Knife (the Indian nickname for Andrew Jackson) and reminded him that they keep the peace. Nevertheless, Jackson retorted that they did not "cut (Tecumseh

Tecumseh ( ; October 5, 1813) was a Shawnee chief and warrior who promoted resistance to the expansion of the United States onto Native American lands. A persuasive orator, Tecumseh traveled widely, forming a Native American confederacy and ...

's) throat" when they had the chance, so they must now cede Creek lands. Jackson also ignored Article 9 of the Treaty of Ghent that restored sovereignty to Indians and their nations.

Eventually, the Creek Confederacy enacted a law that made further land cessions a capital offense

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty, is the state-sanctioned practice of deliberately killing a person as a punishment for an actual or supposed crime, usually following an authorized, rule-governed process to conclude that t ...

. Nevertheless, on February 12, 1825, McIntosh and other chiefs signed the Treaty of Indian Springs, which gave up most of the remaining Creek lands in Georgia. After the U.S. Senate ratified the treaty, McIntosh was assassinated on April 30, 1825, by Creeks led by Menawa.

The Creek National Council, led by Opothle Yohola, protested to the United States that the Treaty of Indian Springs was fraudulent. President John Quincy Adams

John Quincy Adams (; July 11, 1767 – February 23, 1848) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, and diarist who served as the sixth president of the United States, from 1825 to 1829. He previously served as the eighth United States ...

was sympathetic, and eventually, the treaty was nullified in a new agreement, the Treaty of Washington (1826)

The 1826 Treaty of Washington was a treaty between the United States and the Creek Confederacy, led by Opothleyahola. The Creek National Council ceded much of their territory bordering Georgia to the United States.

The Creek Confederacy was a co ...

. The historian R. Douglas Hurt wrote: "The Creeks had accomplished what no Indian nation had ever done or would do again—achieve the annulment of a ratified treaty." However, Governor George Troup

George McIntosh Troup (September 8, 1780 – April 26, 1856) was an American politician from the U.S. state of Georgia. He served in the Georgia General Assembly, U.S. House of Representatives, and U.S. Senate before becoming the 32nd Govern ...

of Georgia ignored the new treaty and began to forcibly remove the Indians under the terms of the earlier treaty. At first, President Adams attempted to intervene with federal troops, but Troup called out the militia, and Adams, fearful of a civil war, conceded. As he explained to his intimates, "The Indians are not worth going to war over."

Although the Creeks had been forced from Georgia, with many Lower Creeks moving to the Indian Territory

The Indian Territory and the Indian Territories are terms that generally described an evolving land area set aside by the United States Government for the relocation of Native Americans who held aboriginal title to their land as a sovereign ...

, there were still about 20,000 Upper Creeks living in Alabama. However, the state moved to abolish tribal governments and extend state laws over the Creeks. Opothle Yohola appealed to the administration of President Andrew Jackson for protection from Alabama; when none was forthcoming, the Treaty of Cusseta

The Treaty of Cusseta was a treaty between the government of the United States and the Creek Nation signed March 24, 1832 (). The treaty ceded all Creek claims east of the Mississippi River to the United States.

Origins

The Treaty of Cusseta ...

was signed on March 24, 1832, which divided up Creek lands into individual allotments. Creeks could either sell their allotments and receive funds to remove to the west, or stay in Alabama and submit to state laws. The Creeks were never given a fair chance to comply with the terms of the treaty, however. Rampant illegal settlement of their lands by Americans continued unabated with federal and state authorities unable or unwilling to do much to halt it. Further, as recently detailed by historian Billy Winn in his thorough chronicle of the events leading to removal, a variety of fraudulent schemes designed to cheat the Creeks out of their allotments, many of them organized by speculators operating out of Columbus, Georgia and Montgomery, Alabama, were perpetrated after the signing of the Treaty of Cusseta. A portion of the beleaguered Creeks, many desperately poor and feeling abused and oppressed by their American neighbors, struck back by carrying out occasional raids on area farms and committing other isolated acts of violence. Escalating tensions erupted into open war with the United States after the destruction of the village of Roanoke, Georgia, located along the Chattahoochee River on the boundary between Creek and American territory, in May 1836. During the so-called "Creek War of 1836

The Creek War of 1836, also known as the Second Creek War or Creek Alabama Uprising, was a conflict in Alabama at the time of Indian Removal between the Muscogee Creek people and non-native land speculators and squatters.

Although the Creek ...

" Secretary of War

The secretary of war was a member of the U.S. president's Cabinet, beginning with George Washington's administration. A similar position, called either "Secretary at War" or "Secretary of War", had been appointed to serve the Congress of the ...

Lewis Cass

Lewis Cass (October 9, 1782June 17, 1866) was an American military officer, politician, and statesman. He represented Michigan in the United States Senate and served in the Cabinets of two U.S. Presidents, Andrew Jackson and James Buchanan. He w ...

dispatched General Winfield Scott

Winfield Scott (June 13, 1786May 29, 1866) was an American military commander and political candidate. He served as a general in the United States Army from 1814 to 1861, taking part in the War of 1812, the Mexican–American War, the early s ...

to end the violence by forcibly removing the Creeks to the Indian Territory west of the Mississippi River. With the Indian Removal Act of 1830 it continued into 1835 and after as in 1836 over 15,000 Creeks were driven from their land for the last time. 3,500 of those 15,000 Creeks did not survive the trip to Oklahoma where they eventually settled.

Chickasaw monetary removal

The Chickasaw received financial compensation from the United States for their lands east of the Mississippi River. In 1836, the Chickasaws had reached an agreement to purchase land from the previously removed Choctaws after a bitter five-year debate. They paid the Choctaws $530,000 (equal to $ today) for the westernmost part of the Choctaw land. The first group of Chickasaws moved in 1836 and was led by John M. Millard. The Chickasaws gathered at

The Chickasaw received financial compensation from the United States for their lands east of the Mississippi River. In 1836, the Chickasaws had reached an agreement to purchase land from the previously removed Choctaws after a bitter five-year debate. They paid the Choctaws $530,000 (equal to $ today) for the westernmost part of the Choctaw land. The first group of Chickasaws moved in 1836 and was led by John M. Millard. The Chickasaws gathered at Memphis

Memphis most commonly refers to:

* Memphis, Egypt, a former capital of ancient Egypt

* Memphis, Tennessee, a major American city

Memphis may also refer to:

Places United States

* Memphis, Alabama

* Memphis, Florida

* Memphis, Indiana

* Memp ...

on July 4, 1836, with all of their assets—belongings, livestock, and slaves. Once across the Mississippi River, they followed routes previously established by the Choctaws and the Creeks. Once in Indian Territory

The Indian Territory and the Indian Territories are terms that generally described an evolving land area set aside by the United States Government for the relocation of Native Americans who held aboriginal title to their land as a sovereign ...

, the Chickasaws merged with the Choctaw nation.

Cherokee forced relocation

By 1838, about 2,000 Cherokee had voluntarily relocated from Georgia to

By 1838, about 2,000 Cherokee had voluntarily relocated from Georgia to Indian Territory

The Indian Territory and the Indian Territories are terms that generally described an evolving land area set aside by the United States Government for the relocation of Native Americans who held aboriginal title to their land as a sovereign ...

(present day Oklahoma). Forcible removals began in May 1838 when General Winfield Scott

Winfield Scott (June 13, 1786May 29, 1866) was an American military commander and political candidate. He served as a general in the United States Army from 1814 to 1861, taking part in the War of 1812, the Mexican–American War, the early s ...

received a final order from President Martin Van Buren

Martin Van Buren ( ; nl, Maarten van Buren; ; December 5, 1782 – July 24, 1862) was an American lawyer and statesman who served as the eighth president of the United States from 1837 to 1841. A primary founder of the Democratic Party, he ...

to relocate the remaining Cherokees. Approximately 4,000 Cherokees died in the ensuing trek to Oklahoma. In the Cherokee language

200px, Number of speakers

Cherokee or Tsalagi ( chr, ᏣᎳᎩ ᎦᏬᏂᎯᏍᏗ, ) is an endangered-to- moribund Iroquoian language and the native language of the Cherokee people. ''Ethnologue'' states that there were 1,520 Cherokee speak ...

, the event is called ''nu na da ul tsun yi'' ("the place where they cried") or ''nu na hi du na tlo hi lu i'' (the trail where they cried). The Cherokee Trail of Tears resulted from the enforcement of the Treaty of New Echota

The Treaty of New Echota was a treaty signed on December 29, 1835, in New Echota, Georgia, by officials of the United States government and representatives of a minority Cherokee political faction, the Treaty Party.

The treaty established ter ...

, an agreement signed under the provisions of the Indian Removal Act

The Indian Removal Act was signed into law on May 28, 1830, by United States President Andrew Jackson. The law, as described by Congress, provided "for an exchange of lands with the Indians residing in any of the states or territories, and for ...

of 1830, which exchanged Indian land in the East for lands west of the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the List of longest rivers of the United States (by main stem), second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest Drainage system (geomorphology), drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson B ...

, but which was never accepted by the elected tribal leadership or a majority of the Cherokee people.

There were significant changes in gender relations within the Cherokee Nation during the implementation of the Indian Removal Act

The Indian Removal Act was signed into law on May 28, 1830, by United States President Andrew Jackson. The law, as described by Congress, provided "for an exchange of lands with the Indians residing in any of the states or territories, and for ...

during the 1830s. Cherokee historically operated on a matrilineal kinship system, where children belonged to the clan of their mother and their only relatives were those who could be traced through her. In addition to being matrilineal, Cherokees were also matrilocal. According to the naturalist William Bartram, "Marriage gives no right to the husband over the property of his wife; and when they part, she keeps the children and property belonging to them." In this way, the typical Cherokee family was structured in a way where the wife held possession to the property, house, and children. However, during the 1820s and 1830s, "Cherokees egan adoptingthe Anglo-American concept of power—a political system dominated by wealthy, highly acculturated men and supported by an ideology that made women … subordinate".

The Treaty of New Echota was largely signed by men. While women were present at the rump council negotiating the treaty, they did not have a seat at the table to participate in the proceedings. Historian Theda Perdue explains that "Cherokee women met in their own councils to discuss their own opinions" despite not being able to participate. The inability for women to join in on the negotiation and signing of the Treaty of New Echota shows how the role of women changed dramatically within Cherokee Nation following colonial encroachment. For instance, Cherokee women played a significant role in the negotiation of land transactions as late as 1785, where they spoke at a treaty conference held at Hopewell, South Carolina to clarify and extend land cessions stemming from Cherokee support of the British in the American Revolution.

The sparsely inhabited Cherokee lands were highly attractive to Georgian farmers experiencing population pressure, and illegal settlements resulted. Long-simmering tensions between Georgia and the Cherokee Nation were brought to a crisis by the discovery of gold near Dahlonega, Georgia

The city of Dahlonega () is the county seat of Lumpkin County, Georgia, United States. As of the 2010 census, the city had a population of 5,242, and in 2018 the population was estimated to be 6,884.

Dahlonega is located at the north end of ...

, in 1829, resulting in the Georgia Gold Rush

The Georgia Gold Rush was the second significant gold rush in the United States and the first in Georgia, and overshadowed the previous rush in North Carolina. It started in 1829 in present-day Lumpkin County near the county seat, Dahlonega, a ...

, the second gold rush

A gold rush or gold fever is a discovery of gold—sometimes accompanied by other precious metals and rare-earth minerals—that brings an onrush of miners seeking their fortune. Major gold rushes took place in the 19th century in Australia, New ...

in U.S. history. Hopeful gold speculators began trespassing on Cherokee lands, and pressure mounted to fulfill the ''Compact of 1802 The Compact of 1802, formally ''Articles of Agreement and Cession'', was a compact between the United States of America and the state of Georgia entered into on April 24, 1802. In it, the United States paid Georgia 1.25 million U.S. dollars for its ...

'' in which the US Government promised to extinguish Indian land claims in the state of Georgia.

When Georgia moved to extend state laws over Cherokee lands in 1830, the matter went to the U.S. Supreme Court. In ''Cherokee Nation v. Georgia

''Cherokee Nation v. Georgia'', 30 U.S. (5 Pet.) 1 (1831), was a United States Supreme Court case. The Cherokee Nation sought a federal injunction against laws passed by the U.S. state of Georgia depriving them of rights within its boundaries, but ...

'' (1831), the Marshall court

The Marshall Court refers to the Supreme Court of the United States from 1801 to 1835, when John Marshall served as the fourth Chief Justice of the United States. Marshall served as Chief Justice until his death, at which point Roger Taney t ...

ruled that the Cherokee Nation

The Cherokee Nation ( Cherokee: ᏣᎳᎩᎯ ᎠᏰᎵ ''Tsalagihi Ayeli'' or ᏣᎳᎩᏰᎵ ''Tsalagiyehli''), also known as the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma, is the largest of three Cherokee federally recognized tribes in the United States. ...

was not a sovereign and independent nation, and therefore refused to hear the case. However, in ''Worcester v. Georgia

''Worcester v. Georgia'', 31 U.S. (6 Pet.) 515 (1832), was a landmark case in which the United States Supreme Court vacated the conviction of Samuel Worcester and held that the Georgia criminal statute that prohibited non-Native Americans from bei ...

'' (1832), the Court ruled that Georgia could not impose laws in Cherokee territory, since only the national government—not state governments—had authority in Indian affairs. '' Worcester v Georgia'' is associated with Andrew Jackson's famous, though apocryphal, quote "John Marshall has made his decision; now let him enforce it!" In reality, this quote did not appear until 30 years after the incident and was first printed in a textbook authored by Jackson critic Horace Greeley

Horace Greeley (February 3, 1811 – November 29, 1872) was an American newspaper editor and publisher who was the founder and editor of the '' New-York Tribune''. Long active in politics, he served briefly as a congressman from New York ...

.

Fearing open warfare between federal troops and the Georgia militia, Jackson decided not to enforce Cherokee claims against the state of Georgia. He was already embroiled in a constitutional crisis with

Fearing open warfare between federal troops and the Georgia militia, Jackson decided not to enforce Cherokee claims against the state of Georgia. He was already embroiled in a constitutional crisis with South Carolina

)''Animis opibusque parati'' ( for, , Latin, Prepared in mind and resources, links=no)

, anthem = " Carolina";" South Carolina On My Mind"

, Former = Province of South Carolina

, seat = Columbia

, LargestCity = Charleston

, LargestMetro = ...

(i.e. the nullification crisis) and favored Cherokee relocation over civil war. With the Indian Removal Act

The Indian Removal Act was signed into law on May 28, 1830, by United States President Andrew Jackson. The law, as described by Congress, provided "for an exchange of lands with the Indians residing in any of the states or territories, and for ...

of 1830, the U.S. Congress had given Jackson authority to negotiate removal treaties, exchanging Indian land in the East for land west of the Mississippi River. Jackson used the dispute with Georgia to put pressure on the Cherokees to sign a removal treaty.

The final treaty, passed in Congress by a single vote, and signed by President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

* President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ...

Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was an American lawyer, planter, general, and statesman who served as the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before being elected to the presidency, he gained fame as ...

, was imposed by his successor President Martin Van Buren

Martin Van Buren ( ; nl, Maarten van Buren; ; December 5, 1782 – July 24, 1862) was an American lawyer and statesman who served as the eighth president of the United States from 1837 to 1841. A primary founder of the Democratic Party, he ...

. Van Buren allowed Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

, Tennessee

Tennessee ( , ), officially the State of Tennessee, is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. Tennessee is the List of U.S. states and territories by area, 36th-largest by ...

, North Carolina

North Carolina () is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. The state is the List of U.S. states and territories by area, 28th largest and List of states and territories of the United ...

, and Alabama

(We dare defend our rights)

, anthem = " Alabama"

, image_map = Alabama in United States.svg

, seat = Montgomery

, LargestCity = Huntsville

, LargestCounty = Baldwin County

, LargestMetro = Greater Birmingham

, area_total_km2 = 135,7 ...

an armed force of 7,000 militiamen, army regulars, and volunteers under General Winfield Scott to relocate about 13,000 Cherokees to Cleveland, Tennessee