The Reform Movement (Upper Canada) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Reform movement in Upper Canada was a political movement in

Organized collective reform activity began with

Organized collective reform activity began with

During the late 1820s, large scale, national petitioning campaigns were organized through a new form of organization, the "Political Union". One of the first and largest was the Birmingham Political Union founded in 1830. Its stated aim was to campaign for electoral reform of the

During the late 1820s, large scale, national petitioning campaigns were organized through a new form of organization, the "Political Union". One of the first and largest was the Birmingham Political Union founded in 1830. Its stated aim was to campaign for electoral reform of the

The Upper Canada Central Political Union was organized in 1832–33 by Dr

The Upper Canada Central Political Union was organized in 1832–33 by Dr

In the absence of Mackenzie, the village of Hope (now

In the absence of Mackenzie, the village of Hope (now

As they were organizing the Convention of Delegates, the reformers also built their own meeting place, which they proposed to call "Shepard's Hall" in honour of Joseph Shepard, one of the political union organizers. The reformers built the hall because their open public electoral meetings were under attack from the

As they were organizing the Convention of Delegates, the reformers also built their own meeting place, which they proposed to call "Shepard's Hall" in honour of Joseph Shepard, one of the political union organizers. The reformers built the hall because their open public electoral meetings were under attack from the

Cold Bath Fields Riot

{{Ontario provincial political parties Political parties in Upper Canada Reform movements Political history of Ontario Owenism Articles containing video clips

British North America

British North America comprised the colonial territories of the British Empire in North America from 1783 onwards. English overseas possessions, English colonisation of North America began in the 16th century in Newfoundland (island), Newfound ...

in the mid-19th century.

It started as a rudimentary grouping of loose coalitions that formed around contentious issues. Support was gained in Parliament through petitions meant to sway MPs. However, ''organized'' Reform activity emerged in the 1830s when Reformers, like Robert Randal, Jesse Ketchum, Peter Perry, Marshall Spring Bidwell

Marshall Spring Bidwell (February 16, 1799 – October 24, 1872) was a lawyer and political figure in Upper Canada.

He was born in Stockbridge, Massachusetts in 1799, the son of politician Barnabas Bidwell. His family settled in Bath in Upper C ...

, and Dr. William Warren Baldwin

William Warren Baldwin (April 25, 1775 – January 8, 1844) was a doctor, businessman, lawyer, judge, architect and reform politician in Upper Canada. He, and his son Robert Baldwin, are recognized for having introduced the concept of "respon ...

, began to emulate the organizational forms of the British Reform Movement and organized Political Unions under the leadership of William Lyon Mackenzie

William Lyon Mackenzie (March12, 1795 August28, 1861) was a Scottish Canadian-American journalist and politician. He founded newspapers critical of the Family Compact, a term used to identify elite members of Upper Canada. He represented Yor ...

. The British Political Unions had successfully petitioned for the Great Reform Act of 1832

The Representation of the People Act 1832 (also known as the 1832 Reform Act, Great Reform Act or First Reform Act) was an Act of Parliament of the United Kingdom (indexed as 2 & 3 Will. IV c. 45) that introduced major changes to the electo ...

that eliminated much political corruption in the English Parliamentary system. Those who adopted these new forms of public mobilization for democratic reform in Upper Canada were inspired by the more radical Owenite Socialists who led the British Chartist and Mechanics Institute movements.

Early organized reform activity in Upper Canada

Robert Fleming Gourlay

Robert Fleming Gourlay (March 24, 1778 – August 1, 1863) was a Scottish-Canadian writer, political reform activist, and agriculturalist.

Early life and education

Gourlay was born in Craigrothie in the Parish of Ceres, Fife, Scotland on 22 M ...

(pronounced "gore-lay"). Gourlay was a well-connected Scottish emigrant who arrived in 1817, hoping to encourage "assisted emigration" of the poor from Britain. He solicited information on the colony through township questionnaires, and soon became a critic of government mismanagement. When the local legislature ignored his call for an inquiry, he called for a petition to the British Parliament. He organized township meetings, and a provincial convention - which the government considered dangerous and seditious. Gourlay was tried in December 1818 under the 1804 Sedition Act and jailed for 8 months. He was banished from the province in August 1819. His expulsion made him a martyr in the reform community.

A loose committee of the "Friends of Religious Liberty" composed of William Lyon Mackenzie

William Lyon Mackenzie (March12, 1795 August28, 1861) was a Scottish Canadian-American journalist and politician. He founded newspapers critical of the Family Compact, a term used to identify elite members of Upper Canada. He represented Yor ...

, Jesse Ketchum, Egerton Ryerson, Joseph Shepard and nineteen others, chaired by Dr William Warren Baldwin

William Warren Baldwin (April 25, 1775 – January 8, 1844) was a doctor, businessman, lawyer, judge, architect and reform politician in Upper Canada. He, and his son Robert Baldwin, are recognized for having introduced the concept of "respon ...

(who was one of only 3 Anglicans) circulated a petition against an "Established Church

A state religion (also called religious state or official religion) is a religion or creed officially endorsed by a sovereign state. A state with an official religion (also known as confessional state), while not secular, is not necessarily a t ...

" in the province. It gained 10,000 signatures by the time it was sent to the British Parliament in March 1831. The petition gained little due to direct intervention by the Church of England.

By mid-1831, the leaders of the reform faction in the House of Assembly such as Dr Rolph and the Baldwins were discouraged and withdrew from politics. At this point, William Lyon Mackenzie organized a "General Committee on the State of the Province" which organized the first truly provincial petitioning campaign to protest a whole series of ills. Although 10,000 signatures were obtained the only real gain was to organize the reformers in the province.

Mackenzie's organizational efforts made him many enemies in the House of Assembly. When the House reconvened, Mackenzie was unjustly expelled. Over the next two years, Mackenzie was re-elected only to be expelled a total of five times. As demonstrations in support of Mackenzie were increasingly met with violence by Orangemen, he travelled to England to personally present his appeal in March 1832. Mackenzie trip to England was to prove inspirational, as he was exposed to the power of the British form of reform activity, the Political Unions, in the run-up to the passage of the Great Reform Act of 1832.

British Reform Movement

Upper Canadians saw themselves as citizens of Great Britain with all the rights granted by the British Constitution. It is no surprise then, that the Upper Canadian Reform Movement should adopt the organizational forms of the British Reform Movement.Political unions and the Great Reform Act of 1832

During the late 1820s, large scale, national petitioning campaigns were organized through a new form of organization, the "Political Union". One of the first and largest was the Birmingham Political Union founded in 1830. Its stated aim was to campaign for electoral reform of the

During the late 1820s, large scale, national petitioning campaigns were organized through a new form of organization, the "Political Union". One of the first and largest was the Birmingham Political Union founded in 1830. Its stated aim was to campaign for electoral reform of the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. ...

, "to be achieved by a general political union of the lower and middle classes of the people". Other more radical Political Unions, like the "Metropolitan Political Union" had their roots in Owenite Socialism.

The London-based "Metropolitan Political Union" was formed by members of the London Radical Reform Organization, including Henry Hunt, Henry Hetherington

Henry Hetherington (June 1792 – 24 August 1849) was an English printer, bookseller, publisher and newspaper proprietor who campaigned for social justice, a free press, universal suffrage and religious freethought. Together with his close asso ...

, William Lovett

William Lovett (8 May 1800 – 8 August 1877) was a British activist and leader of the Chartist political movement. He was one of the leading London-based artisan radicals of his generation.

A proponent of the idea that political rights could ...

, Daniel O'Connell

Daniel O'Connell (I) ( ga, Dónall Ó Conaill; 6 August 1775 – 15 May 1847), hailed in his time as The Liberator, was the acknowledged political leader of Ireland's Roman Catholic majority in the first half of the 19th century. His mobilizat ...

and William Gast. The MPU was radically democratic, and depended upon its members’ input to function. It not only advocated parliamentary reform, but embodied these reforms in the way in which it was organized; it was committed to universal suffrage

Universal suffrage (also called universal franchise, general suffrage, and common suffrage of the common man) gives the right to vote to all adult citizens, regardless of wealth, income, gender, social status, race, ethnicity, or political stanc ...

, annual parliaments, and vote by ballot, all eventually incorporated in the Chartist platform.

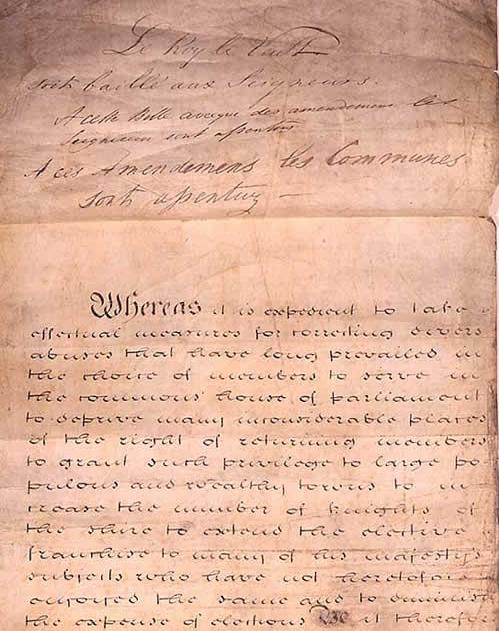

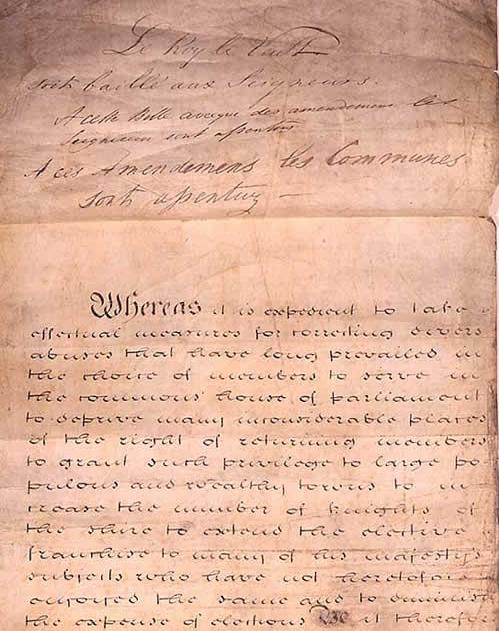

The ''Representation of the People Act 1832'' (commonly known as the ''Reform Act 1832'' or sometimes as ''The Great Reform Act'') was an Act of Parliament

Acts of Parliament, sometimes referred to as primary legislation, are texts of law passed by the Legislature, legislative body of a jurisdiction (often a parliament or council). In most countries with a parliamentary system of government, acts of ...

( 2 & 3 Will. IV) that introduced wide-ranging changes to the electoral system of England and Wales. William Lyon Mackenzie was in London appealing his expulsion from the Upper Canadian Legislative Assembly to the Colonial Office at the time, and was present in the galleries of the British Parliament for the debate on the Reform Act 1832

The Representation of the People Act 1832 (also known as the 1832 Reform Act, Great Reform Act or First Reform Act) was an Act of Parliament, Act of Parliament of the United Kingdom (indexed as 2 & 3 Will. IV c. 45) that introduced major chan ...

. Seeing the effectiveness of the Political Unions in the United Kingdom, Mackenzie recommended their adoption in Upper Canada.

National Union of the Working Classes and the Coldbath-fields National Convention

Disappointment about the refusal to include the working classes in the Great Reform Act of 1832 led to a more protracted campaign for universal suffrage (known asChartism

Chartism was a working-class movement for political reform in the United Kingdom that erupted from 1838 to 1857 and was strongest in 1839, 1842 and 1848. It took its name from the People's Charter of 1838 and was a national protest movement, w ...

) by the radical political unions. The London-based, Owenite inspired National Union of the Working Classes was founded in 1831 by former members of the Metropolitan Political Union. They organized a constitutional convention at Coldbath-Fields to challenge the British parliament in the spring of 1833. They called for adult male suffrage, the secret ballot, annual elections, equally sized electoral districts, as well as for salaries and the elimination of property qualifications for members of parliament. The government prohibited the meeting, and sent 1,800 police against a crowd of 3,000 or 4,000, leading to a general riot. Mackenzie was no doubt aware of the riot as he was living a ten-minute walk away, and news of the riot was published back in Upper Canada by his newspaper, the Colonial Advocate

The ''Colonial Advocate'' was a weekly political journal published in Upper Canada during the 1820s and 1830s. First published by William Lyon Mackenzie on May 18, 1824, the journal frequently attacked the Upper Canada aristocracy known as the ...

.

Atlantic Revolution and Chartism

The membership of the NUWC was later integrated into theLondon Working Men's Association

The London Working Men's Association was an organisation established in London in 1836.

, an organization established in London

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a majo ...

in 1836, that led the Chartist movement. The founders were William Lovett

William Lovett (8 May 1800 – 8 August 1877) was a British activist and leader of the Chartist political movement. He was one of the leading London-based artisan radicals of his generation.

A proponent of the idea that political rights could ...

, Francis Place

Francis Place (3 November 1771 in London – 1 January 1854 in London) was an English social reformer.

Early life

He was an illegitimate son of Simon Place and Mary Gray. His father was originally a journeyman baker. He then became a Marshalse ...

and Henry Hetherington

Henry Hetherington (June 1792 – 24 August 1849) was an English printer, bookseller, publisher and newspaper proprietor who campaigned for social justice, a free press, universal suffrage and religious freethought. Together with his close asso ...

. They were associated with Owenite

Owenism is the utopian socialist philosophy of 19th-century social reformer Robert Owen and his followers and successors, who are known as Owenites. Owenism aimed for radical reform of society and is considered a forerunner of the cooperative ...

socialism and the movement for general education

Education is a purposeful activity directed at achieving certain aims, such as transmitting knowledge or fostering skills and character traits. These aims may include the development of understanding, rationality, kindness, and honesty. Va ...

. They published a People’s Charter on 8 May 1838 calling for universal suffrage. The London Working Men's Association was aware of the unrest in the Canadas in early 1837, and themselves petitioned the British Parliament after a public meeting to protest the "base proposals of the Whigs to destroy the principle of Universal Suffrage in the Canadas". To implement the Chartist plan, they called a series of mass meetings across the country in the summer of 1838 to select delegates to a "General Convention of the Industrious Classes". After the General Convention of the Industrious Classes met in May 1839, their Charter petition was rejected by Parliament. This rejection led to the Newport Uprising of 1839 in Wales, suppressed by Sir Francis Bond Head

Sir Francis Bond Head, 1st Baronet KCH PC (1 January 1793 – 20 July 1875), known as "Galloping Head", was Lieutenant-Governor of Upper Canada during the rebellion of 1837.

Biography

Head was an officer in the corps of Royal Engineers of t ...

's cousin, Sir Edmund Walker Head

Sir Edmund Walker Head, 8th Baronet, KCB (16 February 1805 – 28 January 1868) was a 19th-century British politician and diplomat.

Early life and scholarship

Head was born at Wiarton Place, near Maidstone, Kent, the son of the Reverend Sir J ...

. Rather than view each rebellion in isolation, the Newport Rising (1839), the two Canadian Rebellions (1837–38) and the subsequent American Patriot War

The Patriot War was a conflict along the Canada–United States border in which bands of raiders attacked the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, British colony of Upper Canada more than a dozen times between December 1837 and Decembe ...

(1838–39) can be seen to share a similar republican impetus. They should all be viewed in the context of the late-18th- and early-19th-century Atlantic revolutions

The Atlantic Revolutions (22 March 1765 – 4 December 1838) were numerous revolutions in the Atlantic World in the late 18th and early 19th century. Following the Age of Enlightenment, ideas critical of absolutist monarchies began to spread. A ...

that took their inspiration from the republicanism of the American Revolution.

Political Union Movement in Upper Canada

Upper Canada Central Political Union

The Upper Canada Central Political Union was organized in 1832–33 by Dr

The Upper Canada Central Political Union was organized in 1832–33 by Dr Thomas David Morrison

Thomas David Morrison ( 1796March 19, 1856) was a doctor and political figure in Upper Canada. He was born in Quebec City around 1796 and worked as a clerk in the medical department of the British Army during the War of 1812. He studied m ...

while William Lyon Mackenzie

William Lyon Mackenzie (March12, 1795 August28, 1861) was a Scottish Canadian-American journalist and politician. He founded newspapers critical of the Family Compact, a term used to identify elite members of Upper Canada. He represented Yor ...

was in England. Although inspired by British examples, the Upper Canada Central Political Union was more radical than most reform organizations of the period. The goals proposed by Dr. Thomas Morrison at the York election hustings in late 1832 mirrored those of the Metropolitan Political Union, and the Owenite National Union of the Working Classes. The Union’s objects began with the usual invocation of Upper Canada having been "singularly blessed with a Constitution the very image and transcript of that of Great Britain" but continued with a list of the ways in which that constitution had been abridged before concluding on a radical democratic note. It was not an electoral organization per se, but, like its British model, a voluntary political organization devoted towards electoral reform. It, like its successor, the Canadian Alliance Society, was formed immediately after an election, not before, since their aim was to influence the legislature rather than elect candidates. This union collected 19,930 signatures by May 1833 on a petition protesting Mackenzie's unjust expulsion from the House of Assembly by the Family Compact. It dissolved shortly thereafter.

Children of Peace and the Grand Convention of Delegates

In the absence of Mackenzie, the village of Hope (now

In the absence of Mackenzie, the village of Hope (now Sharon

Sharon ( he, שָׁרוֹן ''Šārôn'' "plain") is a given name as well as an Israeli surname.

In English-speaking areas, Sharon is now predominantly a feminine given name. However, historically it was also used as a masculine given name. In I ...

), founded by the Children of Peace

Children of Peace is a United Kingdom, British-based, non-partisan Charitable organization, charity that focuses upon building friendship, trust and reconciliation between Israeli and Palestinian people, Palestinian children, aged 4–17, reg ...

, a branch of Quakerism, became the new focus of reform activity. They were leaders in the new Fourth Riding of York (a part of the riding that had continued to re-elect Mackenzie over the years). A member of the group, Samuel Hughes

Sir Samuel Hughes, (January 8, 1853 – August 23, 1921) was the Canadian Minister of Militia and Defence during World War I. He was notable for being the last Liberal-Conservative cabinet minister, until he was dismissed from his cabinet post ...

, the president of Canada's first farmers' cooperative (the Farmers' Storehouse), established a "committee of vigilance" to nominate an "independent member" for the Assembly in June 1832. Half the committee were members of the Children of Peace, including the leader of the Children of Peace, David Willson. The group also included Randal Wixson, the editor of the Colonial Advocate

The ''Colonial Advocate'' was a weekly political journal published in Upper Canada during the 1820s and 1830s. First published by William Lyon Mackenzie on May 18, 1824, the journal frequently attacked the Upper Canada aristocracy known as the ...

in Mackenzie's absence.

Mackenzie returned to Toronto from his London journey in the last week of August, 1833, to find his appeals to the British Parliament had been ultimately ineffective. At an emergency meeting of Reformers, David Willson proposed extending the nomination process for members of the House of Assembly they had begun in Hope to all four Ridings of York, and to establish a "General Convention of Delegates" from each riding in which to establish a common political platform. This convention could then become the core of a "permanent convention" or political party – an innovation not yet seen in Upper Canada. The organization of this convention was a model for the "Constitutional Convention" Mackenzie organized for the Rebellion of 1837, where many of the same delegates were to attend.

The Convention was held on 27 February 1834 with delegates from all four of the York ridings. The week before, Mackenzie published Willson's call for a "standing convention" (political party). The day of the convention, the Children of Peace led a "Grand Procession" with their choir and band (the first civilian band in the province) to the Old Court House where the convention was held. David Willson was the main speaker before the convention and "he addressed the meeting with great force and effect". The convention nominated 4 Reform candidates, all of whom were ultimately successful in the election. The convention stopped short, however, of establishing a political party. Instead, they formed yet another Political Union.

Shepard's Hall

As they were organizing the Convention of Delegates, the reformers also built their own meeting place, which they proposed to call "Shepard's Hall" in honour of Joseph Shepard, one of the political union organizers. The reformers built the hall because their open public electoral meetings were under attack from the

As they were organizing the Convention of Delegates, the reformers also built their own meeting place, which they proposed to call "Shepard's Hall" in honour of Joseph Shepard, one of the political union organizers. The reformers built the hall because their open public electoral meetings were under attack from the Orange Order

The Loyal Orange Institution, commonly known as the Orange Order, is an international Protestant fraternal order based in Northern Ireland and primarily associated with Ulster Protestants, particularly those of Ulster Scots heritage. It also ...

. Shepard's Hall was to move several times; it began in a converted court house, moved to Mackenzie's old newspaper office in the second Market building, before taking its final home in "Turton's Building", which they shared with Mackenzie's newspaper ''The Constitution'', and William O'Grady's newspaper, ''The Correspondent & Advocate''. Shepard Hall shared its large meeting space with the Mechanics' Institute and the Children of Peace

Children of Peace is a United Kingdom, British-based, non-partisan Charitable organization, charity that focuses upon building friendship, trust and reconciliation between Israeli and Palestinian people, Palestinian children, aged 4–17, reg ...

. The Mechanics' Institute was a working class educational institute that had its roots in the Owenite

Owenism is the utopian socialist philosophy of 19th-century social reformer Robert Owen and his followers and successors, who are known as Owenites. Owenism aimed for radical reform of society and is considered a forerunner of the cooperative ...

London Radical Reform Organization; the Toronto Institute was formed by a member of the London Mechanics' Institute in 1831. The three legs of the developing Reform movement were thus the political union, the Children of Peace and the Mechanics Institute; the Tories referred to it as the "Holy Alliance Hay Loft" in the market buildings.

Canadian Alliance Society

In January 1835, shortly after the elections, the Upper Canada Political Union was reorganized as the Canadian Alliance Society, with James Lesslie, a city Alderman, as president, and Timothy Parsons as secretary. They were also leaders in the Toronto Mechanics Institute. It was at this time that they moved into Turton's Building, built on land owned by Dr William W. Baldwin. The Canadian Alliance Society adopted much of the platform (such as secret ballot & universal suffrage) of theOwenite

Owenism is the utopian socialist philosophy of 19th-century social reformer Robert Owen and his followers and successors, who are known as Owenites. Owenism aimed for radical reform of society and is considered a forerunner of the cooperative ...

National Union of the Working Classes in London, England, that were to be integrated into the Chartist movement in England.

The Children of Peace immediately formed a branch of the Canadian Alliance Society in January 1835, and elected Samuel Hughes

Sir Samuel Hughes, (January 8, 1853 – August 23, 1921) was the Canadian Minister of Militia and Defence during World War I. He was notable for being the last Liberal-Conservative cabinet minister, until he was dismissed from his cabinet post ...

its president. This branch met every two weeks during the parliamentary session to discuss the bills before the assembly. One of their more interesting proposals was to create a petitioning campaign for a written provincial constitution; Hughes was appointed to the committee. A constitution would be the means by which "the proceedings of our government may be bounded – the legislative council rendered elective, and the government and council made responsible – and that all Eccliastics be prohibited from holding seats in the council and that no officer of the government should be irresponsible". this may have been the inspiration for the constitution Mackenzie published just before the rebellion.

Provincial Loan Bank

The first of the petition movements initiated by the Canadian Alliance Society was a call to form a "Provincial Loan Office". This was a source of loans for pioneer farmers hard pressed to meet expenses in bad years; its inspiration lay with the credit union formed by the Children of Peace in 1832. A province wide "loan office" had been discussed in the colony for more than a decade. This provincially sponsored bank would loan farmers small sums of £1 or £2 against the security of their farms. The petition called for the establishment of a loan office in each district associated with the registry office; these offices would issue "provincial loan notes" equal to twice the provincial debt which would be legal tender. These notes would be loaned in small amounts to farmers on security of their property, due in fifteen years, at 6% simple interest. It offered long term credit, as opposed to the 90-day loans of the Bank of Upper Canada, and would be repaid yearly rather than quarterly, since farmers had only one crop a year to sell. As these farmers paid their yearly installments, this money would be reloaned to others, on a shorter period, so that at the end of fifteen years, the original pool of notes would provide compound interest; the profits from this compound interest would be sufficient, after expenses, to pay off the provincial debt at the end of fifteen years. The petitions were referred first to a select committee of the House of Assembly composed ofSamuel Lount

Samuel Lount (September 24, 1791 – April 12, 1838) was a blacksmith, farmer, magistrate and member of the Legislative Assembly in the province of Upper Canada for Simcoe County from 1834 to 1836. He was an organizer of the failed Upper Can ...

, Charles Duncombe Charles Duncombe may refer to:

*Charles Duncombe (English banker) (1648–1711), English banker, MP and Lord Mayor

*Charles Duncombe, 1st Baron Feversham (1764–1841), English MP

*Charles Duncombe (Upper Canada Rebellion) (1792–1867), American p ...

, and Dr Thomas D. Morrison; they drafted a bill, but the session ended before it could be enacted. Lount and Duncombe would be key organizers of the Rebellion of 1837.

Toronto Political Union

The Canadian Alliance Society was reborn as the Constitutional Reform Society in 1836, when it was led by the more moderate reformer, Dr William W. Baldwin. After the disastrous 1836 elections, it took the final form as the Toronto Political Union in October 1836, again with Dr Baldwin as president. By March 1837, however, the more moderate reformers withdrew in disappointment with their electoral loss, leaving William Lyon Mackenzie to fill the political vacuum. The Toronto Political Union called for a Constitutional Convention in July 1837, and began organizing local "Vigilance Committees" to elect delegates. The structure of the convention was much like that of the "General Convention of Delegates in 1834, and many of the same delegates were elected. This became the organizational structure for the Rebellion of 1837. The Toronto Political Union complained of many issues, but none more than the effects of the financial panic of 1836, and the effects of bankrupt banks like the Bank of Upper Canada suing poor farmers and other debtors. The meetings in the Home District met with an increasing degree ofOrange Order

The Loyal Orange Institution, commonly known as the Orange Order, is an international Protestant fraternal order based in Northern Ireland and primarily associated with Ulster Protestants, particularly those of Ulster Scots heritage. It also ...

violence, so that the reformers began to protect themselves and resort to arms to do so. As the violence continued, peaceable reform meetings tapered off in October, to be replaced by instances of men drilling for battle. The Rebellion

Rebellion, uprising, or insurrection is a refusal of obedience or order. It refers to the open resistance against the orders of an established authority.

A rebellion originates from a sentiment of indignation and disapproval of a situation and ...

of December 7, 1837 marked the end of the Political Union movement in Upper Canada.

Atlantic Revolution and the Rebellions of 1837

The rebellions in 1837 must be viewed in the wider context of the late-18th- and early-19th-centuryAtlantic revolutions

The Atlantic Revolutions (22 March 1765 – 4 December 1838) were numerous revolutions in the Atlantic World in the late 18th and early 19th century. Following the Age of Enlightenment, ideas critical of absolutist monarchies began to spread. A ...

. The American Revolutionary war

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

in 1776, the French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are considere ...

of 1789–1799, the Haitian Revolution

The Haitian Revolution (french: révolution haïtienne ; ht, revolisyon ayisyen) was a successful insurrection by slave revolt, self-liberated slaves against French colonial rule in Saint-Domingue, now the sovereign state of Haiti. The revolt ...

of 1791–1804, the Irish Rebellion of 1798

The Irish Rebellion of 1798 ( ga, Éirí Amach 1798; Ulster-Scots: ''The Hurries'') was a major uprising against British rule in Ireland. The main organising force was the Society of United Irishmen, a republican revolutionary group influence ...

, and Spanish America (1810–1825) were all inspired by the same republican ideals. Even Great Britain's Chartists

Chartism was a working-class movement for political reform in the United Kingdom that erupted from 1838 to 1857 and was strongest in 1839, 1842 and 1848. It took its name from the People's Charter of 1838 and was a national protest movement, ...

sought the same democratic goals. The Canadian rebels believed that the right of citizens to participate in the political process through the election of representatives was the most important right, and they sought to make the legislative council elective rather than appointed. When the British military crushed the rebellions, they ended any possibility the two Canadas would become republics.

Republicanism vs. responsible government

In 1838, John Lambton (Lord Durham), the author of the Great Reform Bill of 1832, arrived in the Canadas to investigate the causes of the Rebellion and make recommendations for reform of the political system. He was to recommend "responsible government

Responsible government is a conception of a system of government that embodies the principle of parliamentary accountability, the foundation of the Westminster system of parliamentary democracy. Governments (the equivalent of the executive bran ...

", not republicanism. The turn to "responsible government" was an explicit strategy adopted by reformers in the face of charges of disloyalty to Britain in the wake of the Rebellions of 1837; the ascendancy of Loyalism as the dominant political ideology of Upper Canada made any demand for democracy a challenge to colonial sovereignty. Struggling to avoid the charge of sedition, reformers later purposefully obscured their true aims of independence from Britain and focused on their grievances against the Family Compact; responsible government thus became a "pragmatic" policy of alleviating local abuses, rather than a revolutionary anti-colonial moment. The author of this pragmatic policy was Robert Baldwin

Robert Baldwin (May 12, 1804 – December 9, 1858) was an Upper Canada, Upper Canadian lawyer and politician who with his political partner Louis-Hippolyte Lafontaine of Lower Canada, led the first responsible government ministry in the Province ...

, who spent the next decade fighting for its implementation. Ironically, it was not achieved until after Baldwin and Louis-Hippolyte Lafontaine

Sir Louis-Hippolyte Ménard '' dit'' La Fontaine, 1st Baronet, KCMG (October 4, 1807 – February 26, 1864) was a Canadian politician who served as the first Premier of the United Province of Canada and the first head of a responsible governmen ...

, the Premiers of the Canadas, shepherded the Rebellion Losses Bill through Parliament in 1849. It sparked Orange riots, and the burning of the Parliament buildings as much of Europe was similarly engulfed in a wave of republican revolutions and counter-revolutions.

References

External links

Cold Bath Fields Riot

{{Ontario provincial political parties Political parties in Upper Canada Reform movements Political history of Ontario Owenism Articles containing video clips