The Masses on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''The Masses'' was a graphically innovative magazine of

After Eastman assumed leadership, and especially after August 1914, the magazine's denouncements of the war were frequent and fierce. In the September 1914 edition of his column, "Knowledge and Revolution," Eastman predicted: "Probably no one will actually be the victor in this gambler's war—for we may as well call it a gambler's war. Only so can we indicate its underlying commercial causes, its futility, and yet also the tall spirit in which it is carried off."

By May 1916, the radical content published in ''The Masses'' had caused it to be boycotted by two major American magazine distribution companies, United News Co. of Philadelphia, and Magazine Distributing Co. of Boston. It was also excluded from the Canadian mails, university libraries, bookshops, and the newsstands of the New York City subway system.

After Eastman assumed leadership, and especially after August 1914, the magazine's denouncements of the war were frequent and fierce. In the September 1914 edition of his column, "Knowledge and Revolution," Eastman predicted: "Probably no one will actually be the victor in this gambler's war—for we may as well call it a gambler's war. Only so can we indicate its underlying commercial causes, its futility, and yet also the tall spirit in which it is carried off."

By May 1916, the radical content published in ''The Masses'' had caused it to be boycotted by two major American magazine distribution companies, United News Co. of Philadelphia, and Magazine Distributing Co. of Boston. It was also excluded from the Canadian mails, university libraries, bookshops, and the newsstands of the New York City subway system.

Although the magazine's birth coincided with the explosion of modernism, and its contributor

Although the magazine's birth coincided with the explosion of modernism, and its contributor  During the later years of its publication, the magazine embraced more modernist art than before, although it never dropped realist illustrations completely. Several of the cover issues from 1916 and 1917 attest to this shift. Instead of featuring crayon drawings of realistic scenes with gentle social satire, they featured cover girls often clad in modern attire and embodying a modernist style.Mark S. Morrisson, "Pluralism and Counterpublic Spheres: Race, Radicalaim, and the Masses" in ''The Public Face of Modernism: Little Magazines, Audiences, and Reception 1905-1920'' (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2001), pp. 167-202. Frank Walts' picture of

During the later years of its publication, the magazine embraced more modernist art than before, although it never dropped realist illustrations completely. Several of the cover issues from 1916 and 1917 attest to this shift. Instead of featuring crayon drawings of realistic scenes with gentle social satire, they featured cover girls often clad in modern attire and embodying a modernist style.Mark S. Morrisson, "Pluralism and Counterpublic Spheres: Race, Radicalaim, and the Masses" in ''The Public Face of Modernism: Little Magazines, Audiences, and Reception 1905-1920'' (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2001), pp. 167-202. Frank Walts' picture of

Vol. 1 (1911)

, Vol. 2 (1912) , Vol. 3 (1913) , Vol. 4 (1914) , Vol. 5 (1915) , Vol. 6 (1916) , Vol. 7 (1917) ,

''The Masses''

digital library site from the Tamiment Library & Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives at New York University: full coverage for 79 issues, from No. 1.1 (Jan 1911) through No. 10-1/2 (Nov/Dec 1917); includes a downloadable index of the magazine's contents.

* ttp://spcexhibits.lib.msu.edu/html/materials/collections/masses/ ''The Masses'' Cover Illustrations Collection* http://www.oldmagazinearticles.com/search_list.php?search=The_Masses

''The Masses''

Complete, high resolution color scans. Most authoritative digital archive of ''The Masses''. Copies provided by NYU.

Political Cartoons from the Masses

Max Eastman Archive

''The Masses''

: a cover-to-cover digital edition of all 79 issues, based on NYU's originals, with free pdfs and a search database.

at the

Complete volume/issue inventory of ''The Masses'' and U.S. libraries with original holdings

by

- Spartacus encyclopedia {{DEFAULTSORT:Masses, The Censorship in the United States Defunct political magazines published in the United States Free love advocates Magazines established in 1911 Magazines disestablished in 1917 Progressive Era in the United States Socialist magazines

socialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the e ...

politics published monthly in the United States from 1911 until 1917, when federal prosecutor

An assistant United States attorney (AUSA) is an official career civil service position in the U.S. Department of Justice composed of lawyers working under the U.S. Attorney of each U.S. federal judicial district. They represent the federal gove ...

s brought charges against its editors for conspiring to obstruct conscription

Conscription (also called the draft in the United States) is the state-mandated enlistment of people in a national service, mainly a military service. Conscription dates back to antiquity and it continues in some countries to the present day un ...

. It was succeeded by '' The Liberator'' and then later ''New Masses

''New Masses'' (1926–1948) was an American Marxist magazine closely associated with the Communist Party USA. It succeeded both ''The Masses'' (1912–1917) and ''The Liberator''. ''New Masses'' was later merged into '' Masses & Mainstream'' (19 ...

''. It published reportage, fiction, poetry and art by the leading radicals of the time such as Max Eastman

Max Forrester Eastman (January 4, 1883 – March 25, 1969) was an American writer on literature, philosophy and society, a poet and a prominent political activist. Moving to New York City for graduate school, Eastman became involved with radical ...

, John Reed, Dorothy Day

Dorothy Day (November 8, 1897 – November 29, 1980) was an American journalist, social activist and anarchist who, after a bohemian youth, became a Catholic without abandoning her social and anarchist activism. She was perhaps the best-known ...

, and Floyd Dell

Floyd James Dell (June 28, 1887 – July 23, 1969) was an American newspaper and magazine editor, literary critic, novelist, playwright, and poet. Dell has been called "one of the most flamboyant, versatile and influential American Men of Letters ...

.

History

Beginnings

Piet Vlag, an eccentric Dutch socialist immigrant from the Netherlands, founded the magazine in 1911. For the first year of its publication, the printing and engraving costs of the magazine were paid for by a sympathetic patron, Rufus Weeks, a vice president at theNew York Life Insurance Company

New York Life Insurance Company (NYLIC) is the third-largest life insurance company in the United States, the largest mutual life insurance company in the United States and is ranked #67 on the 2021 Fortune 500 list of the largest United State ...

. Vlag's dream of a co-operatively operated magazine never worked well, and after just a few issues, he left for Florida

Florida is a state located in the Southeastern region of the United States. Florida is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the northwest by Alabama, to the north by Georgia, to the east by the Bahamas and Atlantic Ocean, and to ...

. His vision of an illustrated socialist monthly had, however, attracted a circle of young activists in Greenwich Village

Greenwich Village ( , , ) is a neighborhood on the west side of Lower Manhattan in New York City, bounded by 14th Street to the north, Broadway to the east, Houston Street to the south, and the Hudson River to the west. Greenwich Village ...

to ''The Masses;'' these included visual artists such as John French Sloan

John French Sloan (August 2, 1871 – September 7, 1951) was an American painter and etcher. He is considered to be one of the founders of the Ashcan school of American art. He was also a member of the group known as The Eight. He is best known ...

from the Ashcan School

The Ashcan School, also called the Ash Can School, was an artistic movement in the United States during the late 19th-early 20th century that produced works portraying scenes of daily life in New York, often in the city's poorer neighborhoods.

...

. These Greenwich Village artists and writers asked one of their own, Max Eastman

Max Forrester Eastman (January 4, 1883 – March 25, 1969) was an American writer on literature, philosophy and society, a poet and a prominent political activist. Moving to New York City for graduate school, Eastman became involved with radical ...

(who was then studying for a doctorate under John Dewey

John Dewey (; October 20, 1859 – June 1, 1952) was an American philosopher, psychologist, and educational reformer whose ideas have been influential in education and social reform. He was one of the most prominent American scholars in the f ...

at Columbia University

Columbia University (also known as Columbia, and officially as Columbia University in the City of New York) is a private research university in New York City. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Church in Manhatt ...

), to edit their magazine. John Sloan

John French Sloan (August 2, 1871 – September 7, 1951) was an American painter and etcher. He is considered to be one of the founders of the Ashcan school of American art. He was also a member of the group known as The Eight. He is best known ...

, Art Young

Arthur Henry Young (January 14, 1866 – December 29, 1943) was an American cartoonist and writer. He is best known for his socialist cartoons, especially those drawn for the left-wing political magazine ''The Masses'' between 1911 and 1917.

B ...

, Louis Untermeyer

Louis Untermeyer (October 1, 1885 – December 18, 1977) was an American poet, anthologist, critic, and editor. He was appointed the fourteenth Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress in 1961.

Life and career

Untermeyer was born in New Y ...

, and Inez Haynes Gillmore (among others) mailed a terse letter to Eastman in August 1912: "You are elected editor of The Masses. No pay." In the first issue, Eastman wrote the following manifesto:

''The Masses'' was to some extent defined by its association with New York's artistic culture. "The birth of ''The Masses''," Eastman later wrote, "coincided with the birth of 'Greenwich Village

Greenwich Village ( , , ) is a neighborhood on the west side of Lower Manhattan in New York City, bounded by 14th Street to the north, Broadway to the east, Houston Street to the south, and the Hudson River to the west. Greenwich Village ...

' as a self-conscious entity, an American Bohemia or gipsy-minded Latin Quarter

The Latin Quarter of Paris (french: Quartier latin, ) is an area in the 5th and the 6th arrondissements of Paris. It is situated on the left bank of the Seine, around the Sorbonne.

Known for its student life, lively atmosphere, and bistros ...

, but its relations with that entity were not simple." ''The Masses'' was very much embedded in a specific metropolitan milieu, unlike some other competing socialist periodicals (such as the '' Appeal to Reason'', a populist-inflected 500,000-circulation weekly produced out of Girard, Kansas

Girard is a city in and the county seat of Crawford County, Kansas, United States. As of the 2020 census, the population of the city was 2,496.

History

Girard was founded in the spring of 1868, in opposition to Crawfordsville, and named af ...

).

The magazine carved out a unique position for itself within American Left

The American Left consists of individuals and groups that have sought egalitarian changes in the economic, political and cultural institutions of the United States. Various subgroups with a national scope are active. Liberals and progressives b ...

print culture. It was more open to Progressive Era

The Progressive Era (late 1890s – late 1910s) was a period of widespread social activism and political reform across the United States focused on defeating corruption, monopoly, waste and inefficiency. The main themes ended during Am ...

reforms, like women's suffrage

Women's suffrage is the right of women to vote in elections. Beginning in the start of the 18th century, some people sought to change voting laws to allow women to vote. Liberal political parties would go on to grant women the right to vot ...

, than Emma Goldman

Emma Goldman (June 27, 1869 – May 14, 1940) was a Russian-born anarchist political activist and writer. She played a pivotal role in the development of anarchist political philosophy in North America and Europe in the first half of the ...

's anarchist '' Mother Earth''. At the same time it fiercely criticized more mainstream leftist publications like ''The New Republic

''The New Republic'' is an American magazine of commentary on politics, contemporary culture, and the arts. Founded in 1914 by several leaders of the progressive movement, it attempted to find a balance between "a liberalism centered in hum ...

'' for insufficient radicalism.

After Eastman assumed leadership, and especially after August 1914, the magazine's denouncements of the war were frequent and fierce. In the September 1914 edition of his column, "Knowledge and Revolution," Eastman predicted: "Probably no one will actually be the victor in this gambler's war—for we may as well call it a gambler's war. Only so can we indicate its underlying commercial causes, its futility, and yet also the tall spirit in which it is carried off."

By May 1916, the radical content published in ''The Masses'' had caused it to be boycotted by two major American magazine distribution companies, United News Co. of Philadelphia, and Magazine Distributing Co. of Boston. It was also excluded from the Canadian mails, university libraries, bookshops, and the newsstands of the New York City subway system.

After Eastman assumed leadership, and especially after August 1914, the magazine's denouncements of the war were frequent and fierce. In the September 1914 edition of his column, "Knowledge and Revolution," Eastman predicted: "Probably no one will actually be the victor in this gambler's war—for we may as well call it a gambler's war. Only so can we indicate its underlying commercial causes, its futility, and yet also the tall spirit in which it is carried off."

By May 1916, the radical content published in ''The Masses'' had caused it to be boycotted by two major American magazine distribution companies, United News Co. of Philadelphia, and Magazine Distributing Co. of Boston. It was also excluded from the Canadian mails, university libraries, bookshops, and the newsstands of the New York City subway system.

Associated Press lawsuits

In July 1913, in the aftermath of the Paint Creek–Cabin Creek strike of 1912 inWest Virginia

West Virginia is a state in the Appalachian, Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States.The Census Bureau and the Association of American Geographers classify West Virginia as part of the Southern United States while the Bur ...

, Max Eastman wrote an editorial in ''The Masses'' accusing the Associated Press

The Associated Press (AP) is an American non-profit news agency headquartered in New York City. Founded in 1846, it operates as a cooperative, unincorporated association. It produces news reports that are distributed to its members, U.S. newspa ...

of "having suppressed and colored the news of that strike in favor of the employers". Eastman detailed the AP's alleged suppression of information regarding the abuses carried out by a military tribunal set up to punish striking coal workers, and also accused the AP of having a conflict of interest, after it was discovered that the AP's local correspondent was also a member of the tribunal. The editorial was accompanied by a cartoon by Art Young, entitled "Poisoned at the Source", which featured a figure of the AP poisoning the reservoir of news with "Lies", "Suppressed Facts", "Prejudice", "Slander", and "Hatred of Labor Organization".

The AP filed suit for criminal libel

Criminal libel is a legal term, of English origin, which may be used with one of two distinct meanings, in those common law jurisdictions where it is still used.

It is an alternative name for the common law offence which is also known (in order ...

against Eastman and Young through its attorney William Rand, but the suit was dismissed by a judge. Rand followed up by persuading the District Attorney in New York City to convene a Grand Jury, which indicted Eastman and Young for criminal libel in December 1913. The two editors were arrested on December 13th and released on $1,000 bail each, facing the prospect of a year in prison if found guilty. A month later, the two were also charged with personally libeling the President of the Associated Press, Frank Brett Noyes

Frank Brett Noyes (July 7, 1863 - December 1, 1948) was president of the ''Washington Evening Star'', a daily afternoon newspaper published in Washington, D.C., and a founder of the Associated Press. He was a son of the ''Star'' publisher Crosb ...

, when it was determined that the figure of the AP in Young's cartoon was in Noyes's likeness.

Young and Eastman were represented ''pro bono'' by Gilbert Roe, and their plight attracted the support of an array of activists including Lincoln Steffens

Lincoln Austin Steffens (April 6, 1866 – August 9, 1936) was an American investigative journalist and one of the leading muckrakers of the Progressive Era in the early 20th century. He launched a series of articles in ''McClure's'', called "Twe ...

, Charlotte Perkins Gilman

Charlotte Perkins Gilman (; née Perkins; July 3, 1860 – August 17, 1935), also known by her first married name Charlotte Perkins Stetson, was an American humanist, novelist, writer, lecturer, advocate for social reform, and eugenicist. She wa ...

, Inez Milholland

Inez Milholland Boissevain (August 6, 1886 – November 25, 1916) was a leading American suffragist, lawyer, and peace activist.

From her college days at Vassar, she campaigned aggressively for women’s rights as the principal issue of a wide ...

, and Amos Pinchot

Amos Richards Eno Pinchot (December 6, 1873 – February 18, 1944) was an American lawyer and reformist. He never held public office but managed to exert considerable influence in reformist circles and did much to keep Progressivism, progres ...

. At a meeting held in support of Eastman and Young at Cooper Union

The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art (Cooper Union) is a private college at Cooper Square in New York City. Peter Cooper founded the institution in 1859 after learning about the government-supported École Polytechnique in ...

, Pinchot expressed his support of their cause and agreed with the two editors' charge that the AP was operating as a monopoly "in constraint of truth". The AP demanded he retract his statement on the threat of a $150,000 libel lawsuit, but Pinchot persuaded the organization that the publicity would reflect poorly on them and the suit went nowhere. The defense consulted the lawyer Samuel Untermyer

Samuel J. Untermyer (March 6, 1858 – March 16, 1940) was a prominent American lawyer and civic leader. He is also remembered for bequeathing his Yonkers, New York estate, now known as Untermyer Park, to the people of New York State.

Life

S ...

, who claimed to have personally witnessed the distortion of the West Virginia news by the AP. After two years of litigation, the District Attorney's office quietly dropped the lawsuits against Young and Eastman.

First trial

Following the passing of theEspionage Act

The Espionage Act of 1917 is a United States federal law enacted on June 15, 1917, shortly after the United States entered World War I. It has been amended numerous times over the years. It was originally found in Title 50 of the U.S. Code (War ...

(Pub. L. 65-24, 40 Stat. 217, enacted June 15, 1917), ''The Masses'' attempted to comply with the new regulations as to remain eligible for shipment by the U.S. Post Office

The United States Postal Service (USPS), also known as the Post Office, U.S. Mail, or Postal Service, is an Independent agencies of the United States government, independent agency of the executive branch of the Federal government of the Uni ...

. The business manager, Merrill Rogers, "made efforts to be in compliance by seeking counsel from George Creel

George Edward Creel (December 1, 1876 – October 2, 1953) was an American investigative journalist and writer, a politician and government official. He served as the head of the United States Committee on Public Information, a propaganda organi ...

, Chairman of the Committee on Public Post office still denied use of the mails." Challenging the injunction from the mail, ''The Masses'' found brief success in having the ban overturned; however, after bringing public attention to the issue, the government officially identified the "treasonable material" in the 1917 August issue and, shortly after, issued charges against Max Eastman, Floyd Dell, John Reed, Josephine Bell, H.J. Glintenkamp, Art Young, and Merrill Rogers. Charged with seeking to "unlawfully and willfully…obstruct the recruiting and enlistment of the United States" military, Eastman and his "conspirators" faced fines up to 10,000 dollars and twenty years imprisonment.

The trial opened April 15, 1918, and despite the onslaught of prejudicial emotions, the defendants were not very worried. The Masses cohort, aware of the prosecutory artifice, played up a lackadaisical performance of absurdist humor. "Contributing to a carnival atmosphere that first day of the trial was a band just outside the courtroom window patriotic tunes in a campaign to sell Liberty Bonds

A liberty bond (or liberty loan) was a war bond that was sold in the United States to support the Allied cause in World War I. Subscribing to the bonds became a symbol of patriotic duty in the United States and introduced the idea of financi ...

and disturbing the solemnity within the courtroom itself. Each time the band played the " Star Spangled Banner" Merrill Rogers jumped to the floor to salute the flag. Only after the fourth time that the band played the tune and only after the Judge asked him did Rogers finally dispense with the salute." Finally, only five of seven defendants even appeared for the trial – Reed was still in Russia and H.J. Glintenkamp was of unknown whereabouts, though rumored to be anywhere from South America to Idaho. Louis Untermeyer

Louis Untermeyer (October 1, 1885 – December 18, 1977) was an American poet, anthologist, critic, and editor. He was appointed the fourteenth Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress in 1961.

Life and career

Untermeyer was born in New Y ...

commented, "As the trial went on it was evident that the indictment was a legal subterfuge and that what was really on trial was the issue of a free press."

Before releasing the jury for deliberation, Judge Learned Hand

Billings Learned Hand ( ; January 27, 1872 – August 18, 1961) was an American jurist, lawyer, and judicial philosopher. He served as a federal trial judge on the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York from 1909 to 1924 a ...

altered the charges against the defendants and attempted to preface the jury of their constitutional duties. Hand dismissed all the charges against Josephine Bell, and dismissed the first count – "conspiracy to cause mutiny and refusal of duty"—against the remaining defendants. Prior to releasing the jurors, Judge Hand stated, "I do not have to remind you that every man has the right to have such economic, philosophic or religious opinions as seem to him best, whether they be socialist, anarchistic or atheistic." After deliberating from Thursday afternoon to Saturday, the jury returned with two decisions. First, the jury was unable to come to a unanimous decision. Secondly, and perhaps more importantly, the jurors seeking to convict the defendants blamed one juror for being unable to conform to the majority opinion, as he was also a socialist and, consequently, un-American. Not only did the other eleven jurors demand the prosecutor to levy charges against the lone juror, but moved to drag the socialist supporter out into the street and lynch him. Judge Hand, given the uproar, declared a mistrial.

Second trial

In September 1918, ''The Masses'' were back on trial, this time joined by John Reed (who had smuggled himself back into the United States from Russia in order to be present at the trial). Aside from new defense attorneys, the proceedings remained very similar to the first trial. Ending his closing arguments, Prosecutor Barnes invoked the image of a dead soldier in France, stating, "He lies dead, and he died for you and he died for me. He died for Max Eastman. He died for John Reed. He died for Merrill Rogers. His voice is but one of a thousand silent voices that demand that these men be punished." Art Young, who had taken to sleeping through most of the court proceedings, awoke at the end of Barnes's argument, whispering loudly, "What? Didn't he die for me?" John Reed, sitting next to Young responded, "Cheer up Art, Jesus died for you." As before, the jury returned unable to come to a unanimous decision (though without threats of violence). After ''The Masses'' died, Eastman and other writers were unwilling to let its spirit go with it. In March 1918, their new monthly adopted the name ofWilliam Lloyd Garrison

William Lloyd Garrison (December , 1805 – May 24, 1879) was a prominent American Christian, abolitionist, journalist, suffragist, and social reformer. He is best known for his widely read antislavery newspaper '' The Liberator'', which he found ...

's famed '' The Liberator''.

''The Masses'' continued to serve as an example for radicals long after it was suppressed. "The only magazine I know which bears a certain resemblance to (Dwight Macdonald

Dwight Macdonald (March 24, 1906 – December 19, 1982) was an American writer, editor, film critic, social critic, literary critic, philosopher, and activist. Macdonald was a member of the New York Intellectuals and editor of their leftist maga ...

's magazine) ''Politics'' and fulfilled a similar function thirty years earlier," Hannah Arendt

Hannah Arendt (, , ; 14 October 1906 – 4 December 1975) was a political philosopher, author, and Holocaust survivor. She is widely considered to be one of the most influential political theorists of the 20th century.

Arendt was born ...

claimed in 1968, was "the old ''Masses'' (1911-1917)."

Notable contributors

*Sherwood Anderson

Sherwood Anderson (September 13, 1876 – March 8, 1941) was an American novelist and short story writer, known for subjective and self-revealing works. Self-educated, he rose to become a successful copywriter and business owner in Cleveland and ...

* Cornelia Barns

*George Bellows

George Wesley Bellows (August 12 or August 19, 1882 – January 8, 1925) was an American realism, American realist painting, painter, known for his bold depictions of urban life in New York City. He became, according to the Columbus Museum of Art ...

*Louise Bryant

Louise Bryant (December 5, 1885 – January 6, 1936) was an American feminist, political activist, and journalist best known for her sympathetic coverage of Russia and the Bolsheviks during the October Revolution, Russian Revolution of Novembe ...

*George Creel

George Edward Creel (December 1, 1876 – October 2, 1953) was an American investigative journalist and writer, a politician and government official. He served as the head of the United States Committee on Public Information, a propaganda organi ...

*Arthur B. Davies

Arthur Bowen Davies (September 26, 1862 – October 24, 1928) was an avant-garde American artist and influential advocate of modern art in the United States c. 1910–1928.

Biography

Davies was born in Utica, New York, the son of David and Phoeb ...

*Dorothy Day

Dorothy Day (November 8, 1897 – November 29, 1980) was an American journalist, social activist and anarchist who, after a bohemian youth, became a Catholic without abandoning her social and anarchist activism. She was perhaps the best-known ...

*Floyd Dell

Floyd James Dell (June 28, 1887 – July 23, 1969) was an American newspaper and magazine editor, literary critic, novelist, playwright, and poet. Dell has been called "one of the most flamboyant, versatile and influential American Men of Letters ...

*Max Eastman

Max Forrester Eastman (January 4, 1883 – March 25, 1969) was an American writer on literature, philosophy and society, a poet and a prominent political activist. Moving to New York City for graduate school, Eastman became involved with radical ...

*Wanda Gág

Wanda Hazel Gág ( ; March 11, 1893 – June 27, 1946) was an American artist, author, translator, and illustrator. She is best known for writing and illustrating the children's book ''Millions of Cats'', the oldest American picture book still i ...

*Jack London

John Griffith Chaney (January 12, 1876 – November 22, 1916), better known as Jack London, was an American novelist, journalist and activist. A pioneer of commercial fiction and American magazines, he was one of the first American authors to ...

*Amy Lowell

Amy Lawrence Lowell (February 9, 1874 – May 12, 1925) was an American poet of the imagist school, which promoted a return to classical values. She posthumously won the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry in 1926.

Life

Amy Lowell was born on Febru ...

*Mabel Dodge Luhan

Mabel Evans Dodge Sterne Luhan (pronounced ''LOO-hahn''; née Ganson; February 26, 1879 – August 13, 1962) was a wealthy American patron of the arts, who was particularly associated with the Taos art colony.

Early life

Mabel Ganson was the heir ...

*Inez Milholland

Inez Milholland Boissevain (August 6, 1886 – November 25, 1916) was a leading American suffragist, lawyer, and peace activist.

From her college days at Vassar, she campaigned aggressively for women’s rights as the principal issue of a wide ...

*Robert Minor

Robert Berkeley "Bob" Minor (15 July 1884 – 26 January 1952), alternatively known as "Fighting Bob," was a political cartoonist, a radical journalist, and, beginning in 1920, a leading member of the American Communist Party.

Background

Robe ...

*Pablo Picasso

Pablo Ruiz Picasso (25 October 1881 – 8 April 1973) was a Spanish painter, sculptor, printmaker, ceramicist and Scenic design, theatre designer who spent most of his adult life in France. One of the most influential artists of the 20th ce ...

* John Reed

*Boardman Robinson

Boardman Michael Robinson (1876–1952) was a Canadian-American painter, illustrator and cartoonist.

Biography

Early years

Boardman Robinson was born September 6, 1876 in Nova Scotia. He spent his childhood in England and Canada, before mov ...

*Carl Sandburg

Carl August Sandburg (January 6, 1878 – July 22, 1967) was an American poet, biographer, journalist, and editor. He won three Pulitzer Prizes: two for his poetry and one for his biography of Abraham Lincoln. During his lifetime, Sandburg ...

*John French Sloan

John French Sloan (August 2, 1871 – September 7, 1951) was an American painter and etcher. He is considered to be one of the founders of the Ashcan school of American art. He was also a member of the group known as The Eight. He is best known ...

*Upton Sinclair

Upton Beall Sinclair Jr. (September 20, 1878 – November 25, 1968) was an American writer, muckraker, political activist and the 1934 Democratic Party nominee for governor of California who wrote nearly 100 books and other works in seve ...

*Louis Untermeyer

Louis Untermeyer (October 1, 1885 – December 18, 1977) was an American poet, anthologist, critic, and editor. He was appointed the fourteenth Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress in 1961.

Life and career

Untermeyer was born in New Y ...

*Mary Heaton Vorse

Mary Heaton Vorse (October 11, 1874 – June 14, 1966) was an American journalist and novelist. She established her reputation as a journalist reporting the labor protests of a largely female and immigrant workforce in the east-coast textile indus ...

*Art Young

Arthur Henry Young (January 14, 1866 – December 29, 1943) was an American cartoonist and writer. He is best known for his socialist cartoons, especially those drawn for the left-wing political magazine ''The Masses'' between 1911 and 1917.

B ...

Politics

The labor struggle

The magazine reported on most of the major labor struggles of its day: from the Paint Creek–Cabin Creek strike of 1912 in West Virginia to the1913 Paterson silk strike

The 1913 Paterson silk strike was a work stoppage involving silk mill workers in Paterson, New Jersey. The strike involved demands for establishment of an eight-hour day and improved working conditions. The strike began in February 1913, and ende ...

and the Ludlow Massacre in Colorado. It strongly sympathized with Big Bill Haywood

William Dudley "Big Bill" Haywood (February 4, 1869 – May 18, 1928) was an American labor organizer and founding member and leader of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) and a member of the executive committee of the Socialist Party of A ...

and his IWW

The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), members of which are commonly termed "Wobblies", is an international labor union that was founded in Chicago in 1905. The origin of the nickname "Wobblies" is uncertain. IWW ideology combines general ...

, the political campaigns of Eugene V. Debs

Eugene Victor "Gene" Debs (November 5, 1855 – October 20, 1926) was an American socialist, political activist, trade unionist, one of the founding members of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), and five times the candidate of the Soc ...

, and a variety of other socialist and anarchist figures. ''The Masses'' also indignantly followed the aftermath of the Los Angeles Times bombing

The ''Los Angeles Times'' bombing was the purposeful dynamite, dynamiting of the Times Mirror Square, ''Los Angeles Times'' Building in Los Angeles, California, United States, on October 1, 1910, by a trade union, union member belonging to the In ...

.

Women's rights and sexual equality

The magazine vigorously argued for birth control (supporting activists likeMargaret Sanger

Margaret Higgins Sanger (born Margaret Louise Higgins; September 14, 1879September 6, 1966), also known as Margaret Sanger Slee, was an American birth control activist, sex educator, writer, and nurse. Sanger popularized the term "birth control ...

) and women's suffrage. Several of its Greenwich Village contributors, like Reed and Dell, practiced free love

Free love is a social movement that accepts all forms of love. The movement's initial goal was to separate the state from sexual and romantic matters such as marriage, birth control, and adultery. It stated that such issues were the concern ...

in their spare time and promoted it (sometimes in veiled terms) in their pieces. Support for these social reforms was sometimes controversial within Marxist circles at the time; some argued that they were distractions from a more proper political goal, class revolution. Emma Goldman

Emma Goldman (June 27, 1869 – May 14, 1940) was a Russian-born anarchist political activist and writer. She played a pivotal role in the development of anarchist political philosophy in North America and Europe in the first half of the ...

once tutted: "It is rather disappointing to find THE MASSES devoting an entire edition to 'Votes for Women.' Perhaps '' Mother Earth'' alone has any faith in women ��that women are capable and are ready to fight for freedom and revolution."

Literature and criticism

American realism

American Realism was a style in art, music and literature that depicted contemporary social realities and the lives and everyday activities of ordinary people. The movement began in literature in the mid-19th century, and became an important te ...

was a vital, pioneering current in the writing of the time, and several leading lights were willing to contribute work to the magazine without pay. The name most associated with the magazine is Sherwood Anderson

Sherwood Anderson (September 13, 1876 – March 8, 1941) was an American novelist and short story writer, known for subjective and self-revealing works. Self-educated, he rose to become a successful copywriter and business owner in Cleveland and ...

. Anderson was "discovered" by ''The Masses fiction editor, Floyd Dell, and his pieces there formed the foundation for his ''Winesburg, Ohio

''Winesburg, Ohio'' (full title: ''Winesburg, Ohio: A Group of Tales of Ohio Small-Town Life'') is a 1919 short story cycle by the American author Sherwood Anderson. The work is structured around the life of protagonist George Willard, from the ...

'' stories. In the November 1916 ''The Masses'', Dell described his surprise years before while reading Anderson's unsolicited manuscript: "there Sherwood Anderson was writing like—I had no other phrase to express it—like a great novelist." Anderson would later be cited by the ''Partisan Review

''Partisan Review'' (''PR'') was a small-circulation quarterly "little magazine" dealing with literature, politics, and cultural commentary published in New York City. The magazine was launched in 1934 by the Communist Party USA–affiliated John ...

'' circle as one of the first homegrown American talents.

The magazine's criticism, edited by Floyd Dell

Floyd James Dell (June 28, 1887 – July 23, 1969) was an American newspaper and magazine editor, literary critic, novelist, playwright, and poet. Dell has been called "one of the most flamboyant, versatile and influential American Men of Letters ...

, was cheekily titled (at least for a time) "Books that Are Interesting." Dell's perceptive reviews gave accolades to many of the most notable books of the time: '' An Economic Interpretation of the Constitution'', ''Spoon River Anthology

''Spoon River Anthology'' (1915), by Edgar Lee Masters, is a collection of short free verse poems that collectively narrates the epitaphs of the residents of Spoon River, a fictional small town named after the Spoon River, which ran near Masters' ...

'', Theodore Dreiser

Theodore Herman Albert Dreiser (; August 27, 1871 – December 28, 1945) was an American novelist and journalist of the naturalist school. His novels often featured main characters who succeeded at their objectives despite a lack of a firm mora ...

's novels, Carl Jung

Carl Gustav Jung ( ; ; 26 July 1875 – 6 June 1961) was a Swiss psychiatrist and psychoanalyst who founded analytical psychology. Jung's work has been influential in the fields of psychiatry, anthropology, archaeology, literature, philo ...

's ''Psychology of the Unconscious

''Psychology of the Unconscious'' (german: Wandlungen und Symbole der Libido) is an early work of Carl Jung, first published in 1912. The English translation by Beatrice M. Hinkle appeared in 1916 under the full title of ''Psychology of the Uncon ...

'', G. K. Chesterton's works, Jack London

John Griffith Chaney (January 12, 1876 – November 22, 1916), better known as Jack London, was an American novelist, journalist and activist. A pioneer of commercial fiction and American magazines, he was one of the first American authors to ...

's memoirs, and many other prominent creations.

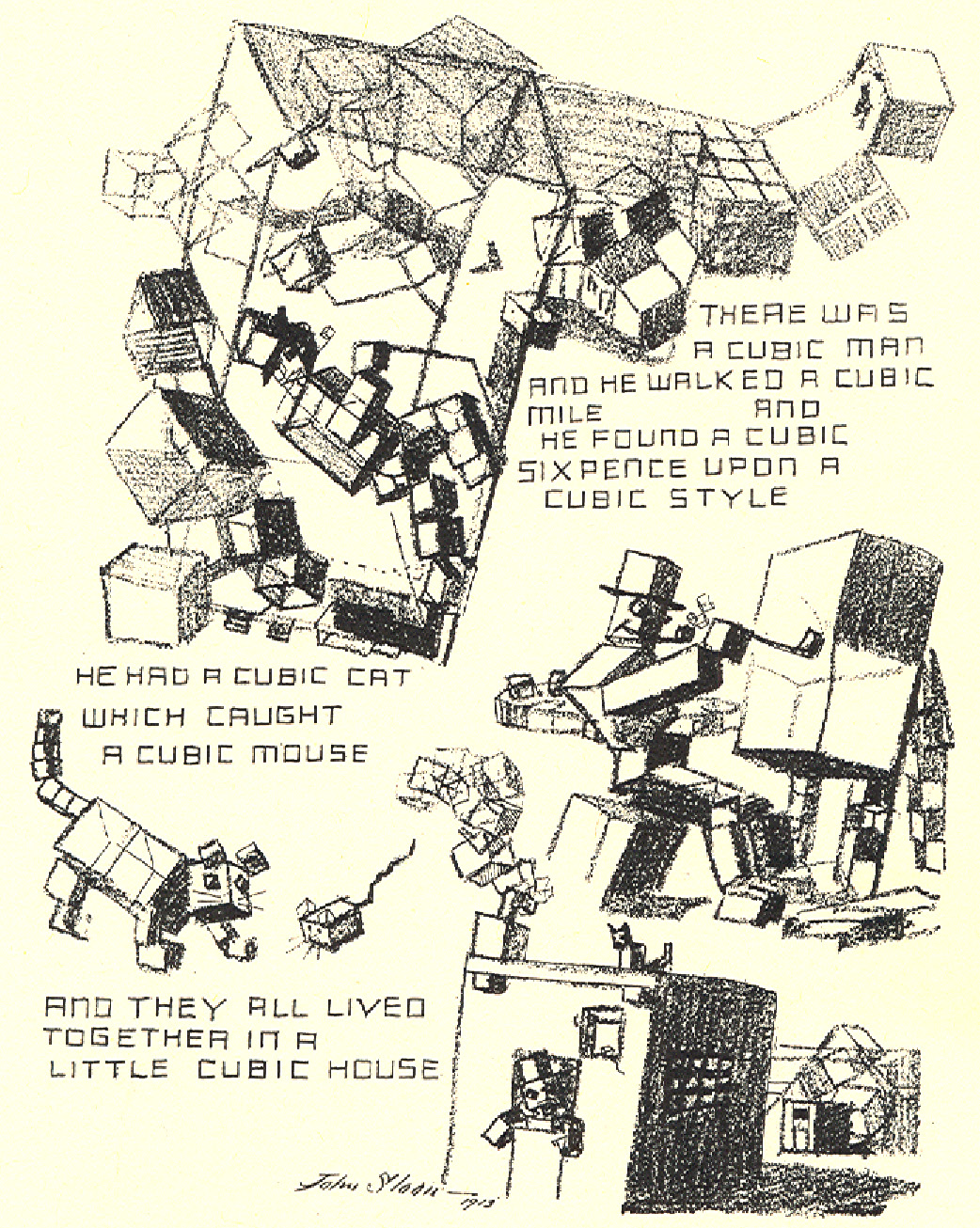

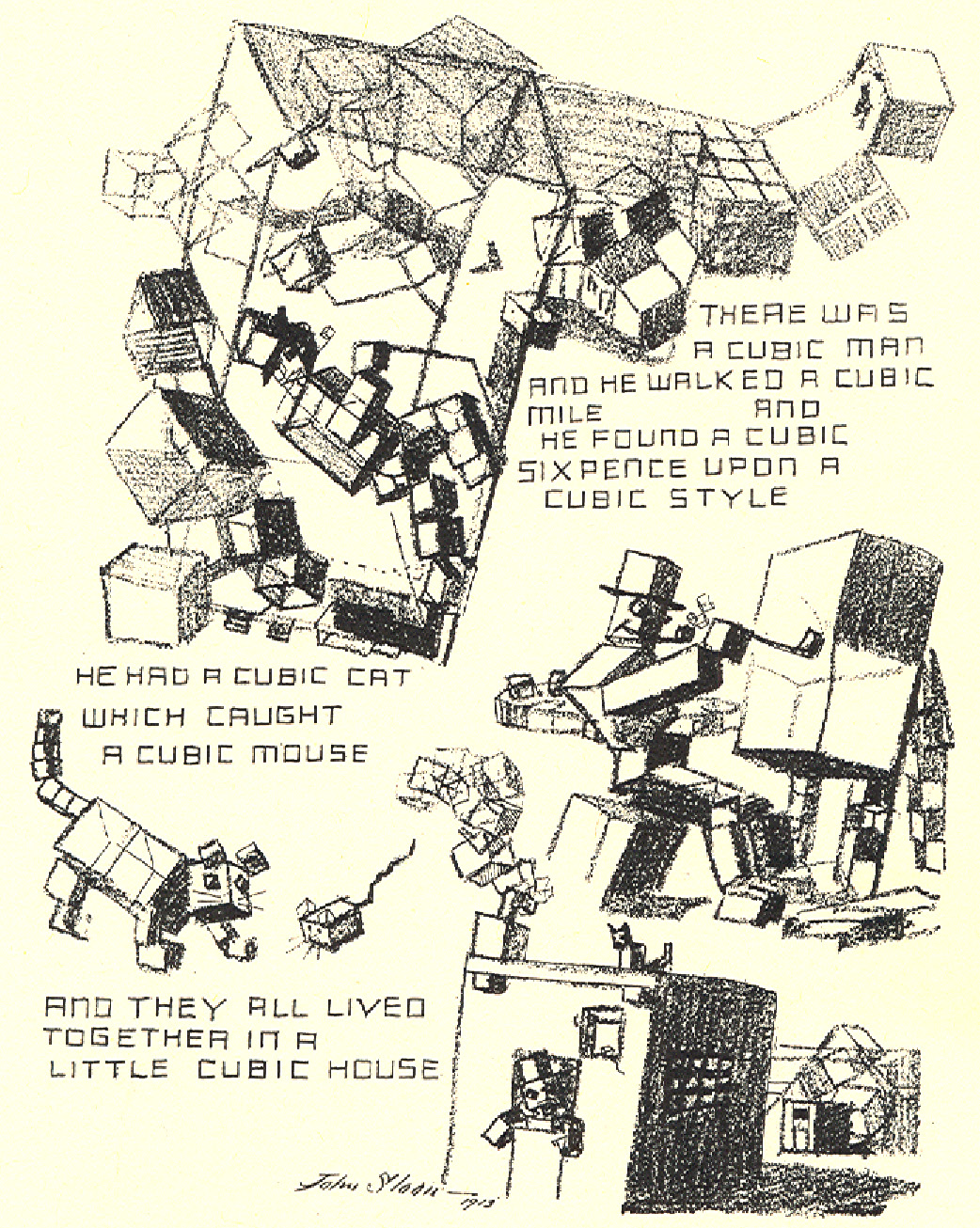

Illustrations

Although the magazine's birth coincided with the explosion of modernism, and its contributor

Although the magazine's birth coincided with the explosion of modernism, and its contributor Arthur B. Davies

Arthur Bowen Davies (September 26, 1862 – October 24, 1928) was an avant-garde American artist and influential advocate of modern art in the United States c. 1910–1928.

Biography

Davies was born in Utica, New York, the son of David and Phoeb ...

was an organizer of the Armory Show

The 1913 Armory Show, also known as the International Exhibition of Modern Art, was a show organized by the Association of American Painters and Sculptors in 1913. It was the first large exhibition of modern art in America, as well as one of ...

, ''The Masses'' published for the most part realist artwork that would later be classified in the Ashcan School

The Ashcan School, also called the Ash Can School, was an artistic movement in the United States during the late 19th-early 20th century that produced works portraying scenes of daily life in New York, often in the city's poorer neighborhoods.

...

. Art Young

Arthur Henry Young (January 14, 1866 – December 29, 1943) was an American cartoonist and writer. He is best known for his socialist cartoons, especially those drawn for the left-wing political magazine ''The Masses'' between 1911 and 1917.

B ...

, who served on the editorial board for the full run of the magazine, is credited with first using the term "ash can art" in 1916. These artists were attempting to record real life and create honest pictures, and they would often use the crayon technique to do so. This technique resulted in "capturing the feeling of a rapid sketch made on the spot and permitting a direct, unmediated response to what they saw" and is commonly found on the pages of ''The Masses'' from 1912 to 1916. This type of illustration became less common after the artists' strike in 1916, which ended with many artists leaving the magazine. The strike occurred when Max Eastman

Max Forrester Eastman (January 4, 1883 – March 25, 1969) was an American writer on literature, philosophy and society, a poet and a prominent political activist. Moving to New York City for graduate school, Eastman became involved with radical ...

began to assert more influence over what was published and began printing material without first submitting it to the editorial board for a vote. While the majority of the editorial board backed up Eastman, some of the staff questioned "what they saw as Eastman's attempts to turn ''The Masses'' into a 'one-man magazine instead of a cooperative sheet.'" One of the main issues the artists took up during the strike was that Eastman and Floyd Dell

Floyd James Dell (June 28, 1887 – July 23, 1969) was an American newspaper and magazine editor, literary critic, novelist, playwright, and poet. Dell has been called "one of the most flamboyant, versatile and influential American Men of Letters ...

were appending many illustrations with captions without the approval or knowledge of the artists. This particularly irritated John Sloan

John French Sloan (August 2, 1871 – September 7, 1951) was an American painter and etcher. He is considered to be one of the founders of the Ashcan school of American art. He was also a member of the group known as The Eight. He is best known ...

who saw the magazine as moving away from its original purpose and stated, "''The Masses'' is no longer the resultant of the ideas and art of a number of personalities. ''The Masses'' has developed a 'policy.'"Rebecca Zurier, ''Art for'' The Masses: ''A Radical Magazine and Its Graphics, 1911–1917'', Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1988, 52. Not agreeing with this idea of a policy, which became more and more serious with the escalation of World War I, Sloan and other artists (including Maurice Becker

Maurice Becker (1889– August 28, 1975) was a radical political artist best known for his work in the 1910s and 1920s for such publications as ''The Masses'' and '' The Liberator''.

Biography

Early years

Maurice Becker was born in Nizhni-Novg ...

, Alice Beach Winter, and Charles Winter) resigned from the magazine in 1916.

During the later years of its publication, the magazine embraced more modernist art than before, although it never dropped realist illustrations completely. Several of the cover issues from 1916 and 1917 attest to this shift. Instead of featuring crayon drawings of realistic scenes with gentle social satire, they featured cover girls often clad in modern attire and embodying a modernist style.Mark S. Morrisson, "Pluralism and Counterpublic Spheres: Race, Radicalaim, and the Masses" in ''The Public Face of Modernism: Little Magazines, Audiences, and Reception 1905-1920'' (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2001), pp. 167-202. Frank Walts' picture of

During the later years of its publication, the magazine embraced more modernist art than before, although it never dropped realist illustrations completely. Several of the cover issues from 1916 and 1917 attest to this shift. Instead of featuring crayon drawings of realistic scenes with gentle social satire, they featured cover girls often clad in modern attire and embodying a modernist style.Mark S. Morrisson, "Pluralism and Counterpublic Spheres: Race, Radicalaim, and the Masses" in ''The Public Face of Modernism: Little Magazines, Audiences, and Reception 1905-1920'' (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2001), pp. 167-202. Frank Walts' picture of Mary Fuller

Mary Claire Fuller (October 5, 1888 – December 9, 1973) was an American actress active in both stage and silent films. She also was a screenwriter and had several films produced. An early major star, by 1917 she could no longer gain role ...

has been given as an example of this.

In addition to the realistic and modernist artwork, the magazine was also well known for its many political cartoons. Art Young is perhaps most famous for these; but other artists, such as Robert Minor

Robert Berkeley "Bob" Minor (15 July 1884 – 26 January 1952), alternatively known as "Fighting Bob," was a political cartoonist, a radical journalist, and, beginning in 1920, a leading member of the American Communist Party.

Background

Robe ...

, also contributed to this aspect of the magazine. The cartoons, especially those by Young and Minor, were at times quite controversial and, after the United States entered World War I, considered treasonous for their anti-war sentiments.

The illustrations published often pushed the socialist agenda for which ''The Masses'' was known. John Sloan's drawings of the working class and immigrants, for example, advocated for labor rights; Alice Beach Winter's work was known to emphasized motherhood and the plight of working children; and Maurice Becker's city life scenes satirized the extravagant lifestyle of the upper class. While many of the illustrations in ''The Masses'' made a political or social point, Max Eastman did frequently publish art for its aesthetic value and wanted the magazine to be a publication, which combined revolutionary ideas with both literature and art for its own sake.

See also

*Christian anarchism

Christian anarchism is a Christian movement in political theology that claims anarchism is inherent in Christianity and the Gospels. It is grounded in the belief that there is only one source of authority to which Christians are ultimately answ ...

*Christian pacifism

Christian pacifism is the theological and ethical position according to which pacifism and non-violence have both a scriptural and rational basis for Christians, and affirms that any form of violence is incompatible with the Christian faith. Chr ...

*Masses Publishing Co. v. Patten

''Masses Publishing Co. v. Patten'', 244 F. 535 ( S.D.N.Y. 1917), was a decision by the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York, that addressed advocacy of illegal activity under the First Amendment.

Background

In ca ...

References

Further reading

* Fishbein, Leslie. ''Rebels in Bohemia: The Radicals of The Masses, 1911–1917''. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1982. * Maik, Thomas A. ''The Masses Magazine (1911–1917): Odyssey of an Era''. New York: Garland, 1994. * O'Neill, William. ''Echoes of Revolt: The Masses, 19111917.'' Chicago: Ivan Dee, 1966. *Schreiber, Rachel. ''Gender and Activism in a Little Magazine: the modern figures of the Masses''. London: Routledge, 2016 (original publicated Ashgate, 2011). *Watts, Theodore F. ''The Masses Index 1911–1917''. Easthampton, MA: Periodyssey, 2000. * Zurier, Rebecca. ''Art for The Masses: A Radical Magazine and Its Graphics, 1911–1917.'' Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1988. * ''The Masses''Vol. 1 (1911)

, Vol. 2 (1912) , Vol. 3 (1913) , Vol. 4 (1914) , Vol. 5 (1915) , Vol. 6 (1916) , Vol. 7 (1917) ,

External links

''The Masses''

digital library site from the Tamiment Library & Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives at New York University: full coverage for 79 issues, from No. 1.1 (Jan 1911) through No. 10-1/2 (Nov/Dec 1917); includes a downloadable index of the magazine's contents.

* ttp://spcexhibits.lib.msu.edu/html/materials/collections/masses/ ''The Masses'' Cover Illustrations Collection* http://www.oldmagazinearticles.com/search_list.php?search=The_Masses

Marxists Internet Archive

Marxists Internet Archive (also known as MIA or Marxists.org) is a non-profit online encyclopedia that hosts a multilingual library (created in 1990) of the works of communist, anarchist, and socialist writers, such as Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels ...

''The Masses''

Complete, high resolution color scans. Most authoritative digital archive of ''The Masses''. Copies provided by NYU.

Political Cartoons from the Masses

Max Eastman Archive

Modernist Journals Project The Modernist Journals Project (MJP) was created in 1995 at Brown University in order to create a database of digitized periodicals connected with the period loosely associated with modernism. The University of Tulsa joined in 2003. The MJP's websit ...

''The Masses''

: a cover-to-cover digital edition of all 79 issues, based on NYU's originals, with free pdfs and a search database.

at the

Modernist Journals Project The Modernist Journals Project (MJP) was created in 1995 at Brown University in order to create a database of digitized periodicals connected with the period loosely associated with modernism. The University of Tulsa joined in 2003. The MJP's websit ...

: explore the database using quantitative analysis and visualization tools.

Complete volume/issue inventory of ''The Masses'' and U.S. libraries with original holdings

Articles

by

David Oshinsky

David M. Oshinsky (born 1944) is an American historian. He is the director of the Division of Medical Humanities at NYU School of Medicine and a professor in the Department of History at New York University.

Background

Oshinsky graduated from C ...

in the ''New York Times'' (September 4, 1988).

- Spartacus encyclopedia {{DEFAULTSORT:Masses, The Censorship in the United States Defunct political magazines published in the United States Free love advocates Magazines established in 1911 Magazines disestablished in 1917 Progressive Era in the United States Socialist magazines