The Malay Archipelago on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''The Malay Archipelago'' is a book by the British naturalist

The book is dedicated to

The book is dedicated to

''The Malay Archipelago'' was largely written at Treeps, Wallace's wife's family home in

''The Malay Archipelago'' was largely written at Treeps, Wallace's wife's family home in

The illustrations are, according to the ''Preface'', made from Wallace's own sketches, photographs, or specimens. Wallace thanks Walter and Henry Woodbury for some photographs of scenery and native people. He acknowledges William Wilson Saunders and Mr Pascoe for horned flies and very rare longhorn beetles: all the rest were from his own enormous collection.

The original drawings were made directly on to the

The illustrations are, according to the ''Preface'', made from Wallace's own sketches, photographs, or specimens. Wallace thanks Walter and Henry Woodbury for some photographs of scenery and native people. He acknowledges William Wilson Saunders and Mr Pascoe for horned flies and very rare longhorn beetles: all the rest were from his own enormous collection.

The original drawings were made directly on to the

;2 Singapore

: Wallace gives a lively description of the people of the town, and of the wildlife of the island. He finds the Chinese the most noticeable of the people, while in one square mile of forest he found 700 species of beetles including 130 longhorns.

;3

;2 Singapore

: Wallace gives a lively description of the people of the town, and of the wildlife of the island. He finds the Chinese the most noticeable of the people, while in one square mile of forest he found 700 species of beetles including 130 longhorns.

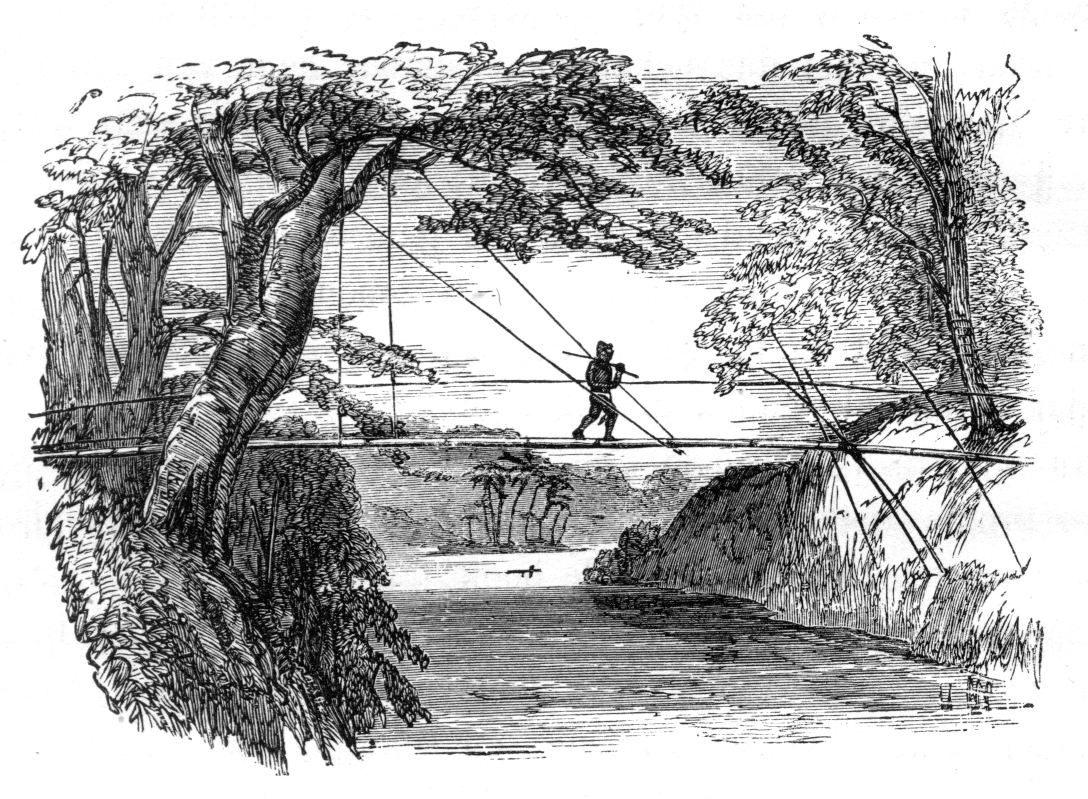

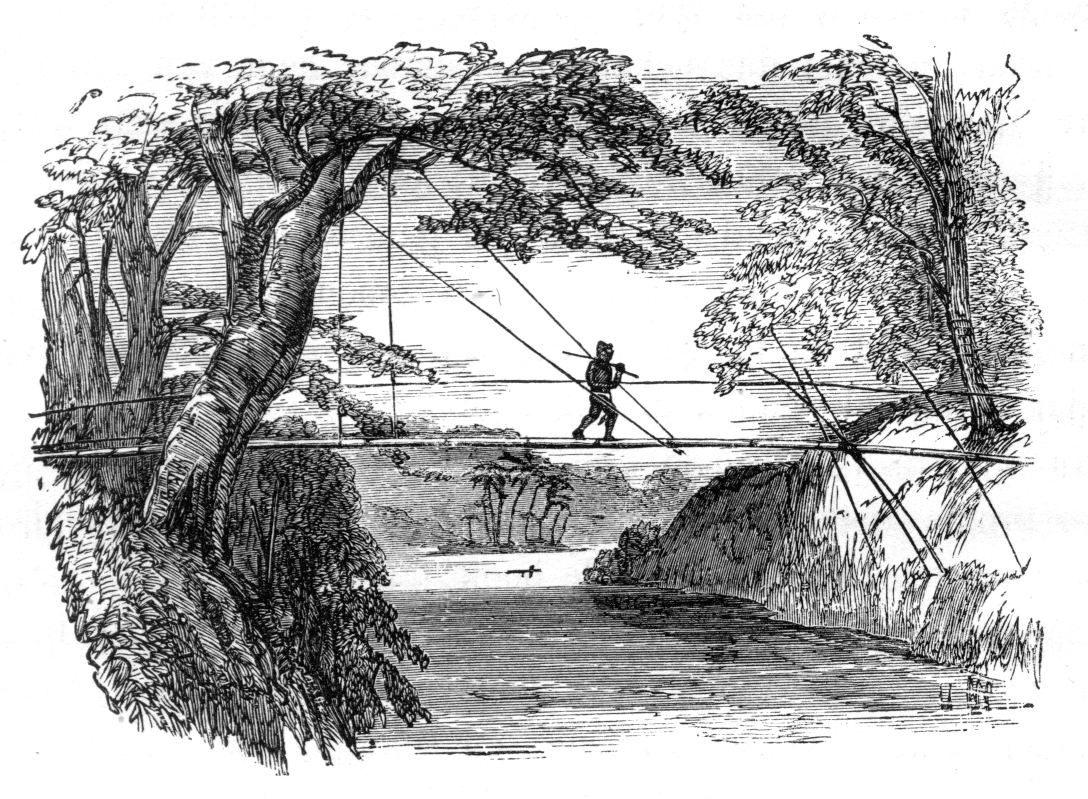

;3  ;5 Borneo—Journey in the Interior

: Wallace returns to Sarawak, where he stays in the circular 'head-house' of a Dyak village, travels upriver, and describes the Durian, praising it as the king of fruits with exquisite and unsurpassed flavour,Wallace, 1869. Volume 1, pp. 117–119. and the Dyak's slender bamboo bridges,Wallace, 1869. Volume 1, pp. 123–124. as well as ferns and ''

;5 Borneo—Journey in the Interior

: Wallace returns to Sarawak, where he stays in the circular 'head-house' of a Dyak village, travels upriver, and describes the Durian, praising it as the king of fruits with exquisite and unsurpassed flavour,Wallace, 1869. Volume 1, pp. 117–119. and the Dyak's slender bamboo bridges,Wallace, 1869. Volume 1, pp. 123–124. as well as ferns and ''

;10

;10

;15 Celebes—Macassar

: Wallace finds staying in the town of Macassar expensive, and moves out into the countryside. He meets the rajah, and is lucky enough to stay on a farm where he is given a glass of milk every day, "one of my greatest luxuries".Wallace, 1869. Volume 1, p. 355.

;16 Celebes—Macassar

: He catches some '' Ornithoptera'' (birdwings), "the largest, the most perfect, and the most beautiful of butterflies".Wallace, 1869. Volume 1, p. 364. He uses rotten jackfruit to attract beetles, but finds few birds. The limestone mountains are eroded into skittle-shaped pillars with narrow bases.

;17 Celebes—Menado

: Wallace visits Menado on the northeast coast of Celebes. The people of the Minahasa region are fair-skinned, unlike anywhere else in the archipelago. He stays high in the mountains by the coffee plantations, and is often cold, but finds that the animals are no different from those lower down. The forest was full of

;15 Celebes—Macassar

: Wallace finds staying in the town of Macassar expensive, and moves out into the countryside. He meets the rajah, and is lucky enough to stay on a farm where he is given a glass of milk every day, "one of my greatest luxuries".Wallace, 1869. Volume 1, p. 355.

;16 Celebes—Macassar

: He catches some '' Ornithoptera'' (birdwings), "the largest, the most perfect, and the most beautiful of butterflies".Wallace, 1869. Volume 1, p. 364. He uses rotten jackfruit to attract beetles, but finds few birds. The limestone mountains are eroded into skittle-shaped pillars with narrow bases.

;17 Celebes—Menado

: Wallace visits Menado on the northeast coast of Celebes. The people of the Minahasa region are fair-skinned, unlike anywhere else in the archipelago. He stays high in the mountains by the coffee plantations, and is often cold, but finds that the animals are no different from those lower down. The forest was full of

;23 Voyage to the Kaióa Islands and Batchian

: He hires a small boat to go to the highly recommended island of Batchian and crosses to Tidore, where he sees the comet of October 1858; it spans about 20 degrees of the night sky. They sail past the volcanic island of Makian which erupted in 1646 and devastatingly again, soon after Wallace had left the archipelago, in 1862. In the Kaióa Islands he finds some virgin forest where the beetles are more abundant than anywhere he ever saw in his life, with swarms of golden

;23 Voyage to the Kaióa Islands and Batchian

: He hires a small boat to go to the highly recommended island of Batchian and crosses to Tidore, where he sees the comet of October 1858; it spans about 20 degrees of the night sky. They sail past the volcanic island of Makian which erupted in 1646 and devastatingly again, soon after Wallace had left the archipelago, in 1862. In the Kaióa Islands he finds some virgin forest where the beetles are more abundant than anywhere he ever saw in his life, with swarms of golden  ;24 Batchian

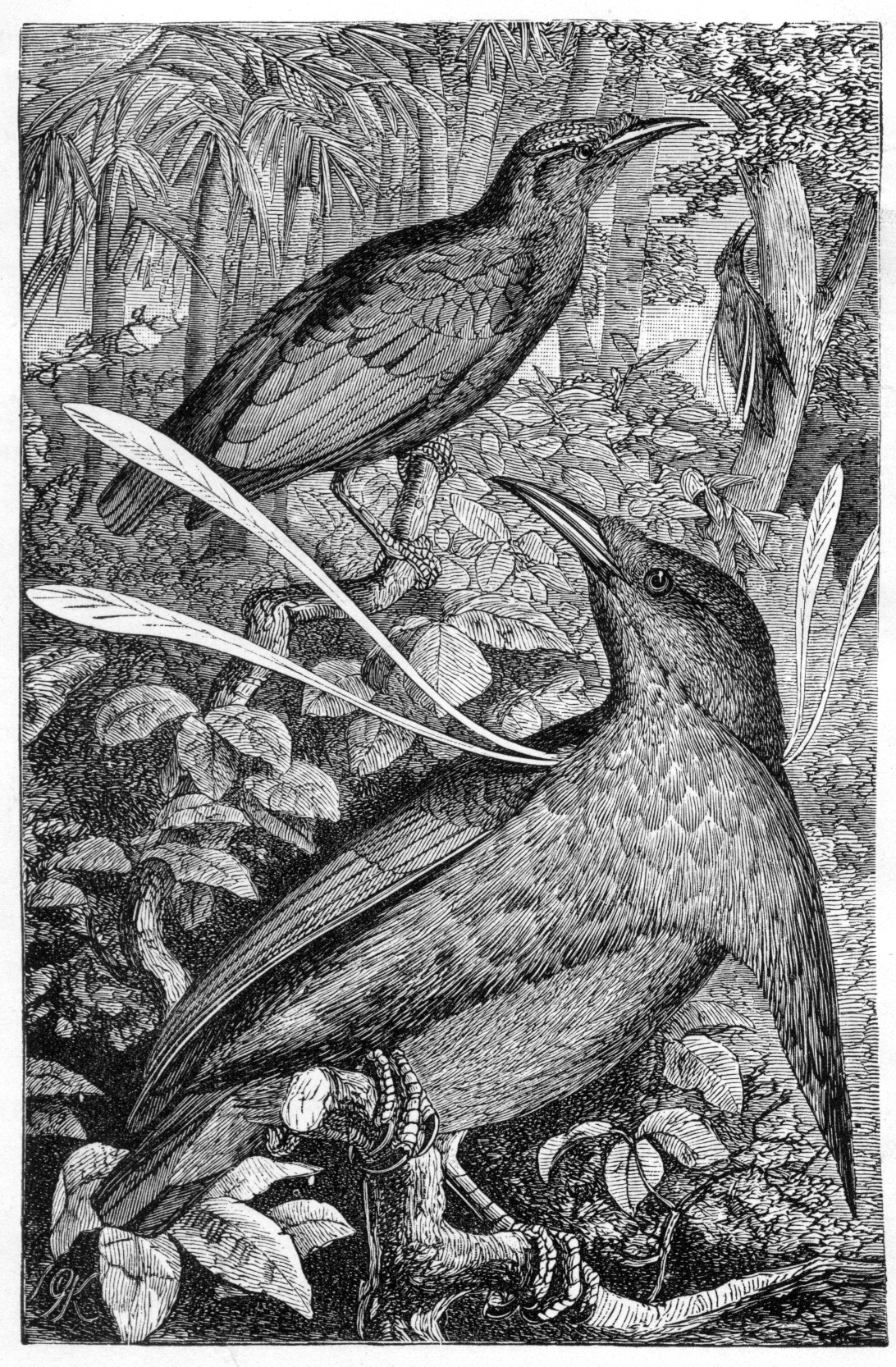

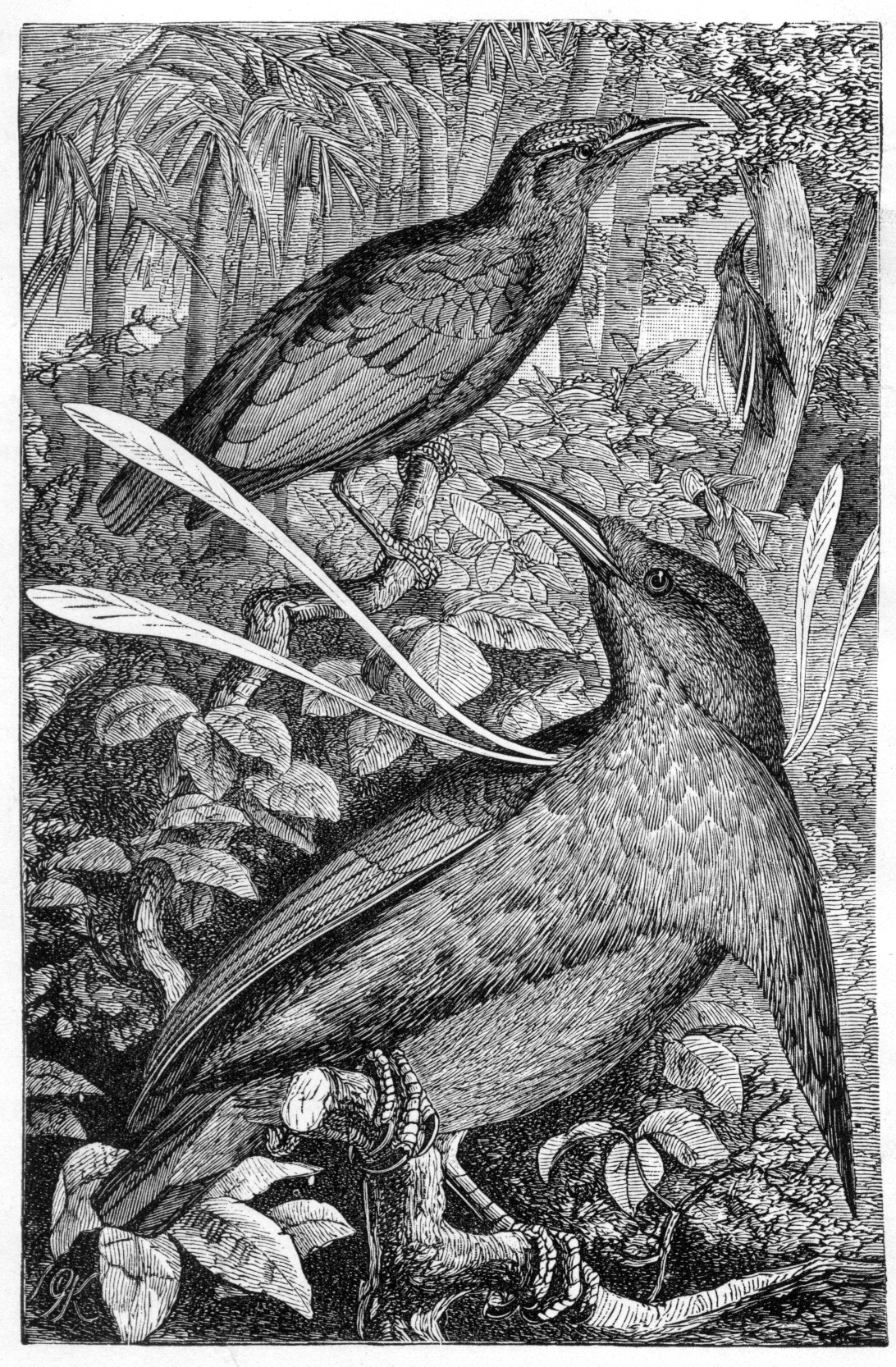

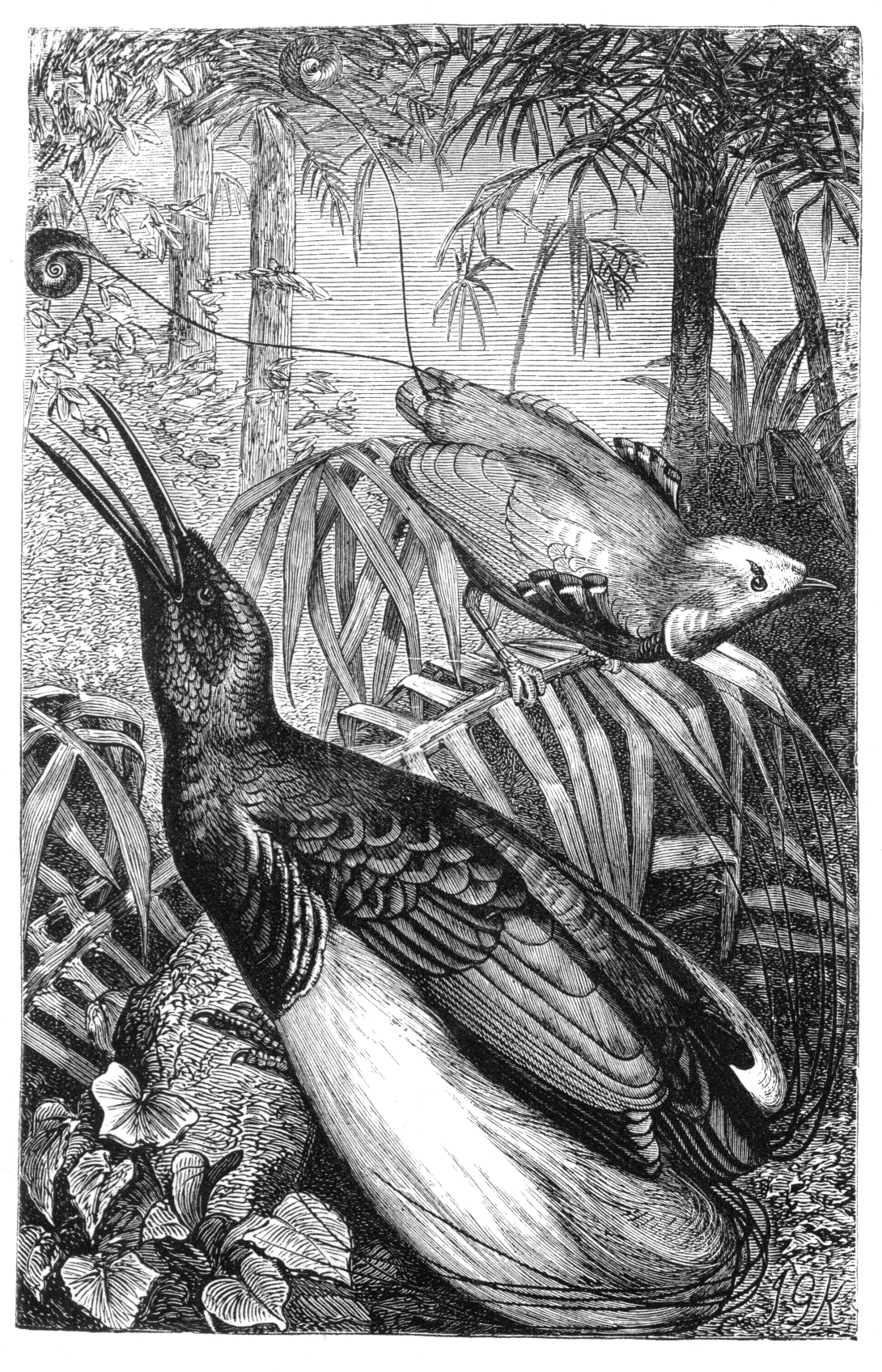

: He is lent a house by the Sultan, who offers him tea and cakes but asks him to teach him to make maps and to give him a gun and a milking goat, "all of which requests I evaded as skilfully as I was able".Wallace, 1869. Volume 2, p. 38. His servant Ali shoots a new bird of paradise, Wallace's standardwing, "a great prize" and a "striking novelty".Wallace, 1869. Volume 2, p. 41. He is a little disappointed in the range of insects and birds, but discovers new species of

;24 Batchian

: He is lent a house by the Sultan, who offers him tea and cakes but asks him to teach him to make maps and to give him a gun and a milking goat, "all of which requests I evaded as skilfully as I was able".Wallace, 1869. Volume 2, p. 38. His servant Ali shoots a new bird of paradise, Wallace's standardwing, "a great prize" and a "striking novelty".Wallace, 1869. Volume 2, p. 41. He is a little disappointed in the range of insects and birds, but discovers new species of

;28 Macassar to the Aru Islands in a Native

;28 Macassar to the Aru Islands in a Native  ;31 The Aru Islands—Journey and Residence in the Interior

: He is brought a king bird-of-paradise, amusing the islanders with his excitement; it had been one of his goals for travelling to the archipelago. He reflects on how their beauty is wasted in the "dark and gloomy woods, with no intelligent eye to gaze upon their loveliness", but that when "civilized man" reaches the islands he will certainly upset the balance of nature and make the birds extinct.Wallace, 1869. Volume 2, pp. 222–224. He finds the men the most beautiful of all the peoples he has stayed among, the women less handsome "except in extreme youth".Wallace, 1869. Volume 2, p. 254.

;32 The Aru Islands—Second Residence in Dobbo

: He sees a cock-fight in the street, but is more interested in a game of football, played with a hollow ball of rattan, and remarks the "excessive cheapness"Wallace, 1869. Volume 2, p. 271. of all goods including those made in Europe or America, which he believes causes idleness and drunkenness because there is no need to work hard to obtain goods. He admires a crimson-flowered tree surrounded with flocks of blue and orange lories. He is given some birds' nest soup, which he found almost tasteless.

;33 The Aru Islands—Physical Geography and Aspects of Nature

: The islands are completely crossed by three narrow channels which resemble and are called rivers, though they are inlets of the sea. The wildlife is much like that of New Guinea, 150 miles (240 km) away, which he supposes was once connected by a land bridge. Most flowers are green; large and showy flowers are rare or absent.

;34

;31 The Aru Islands—Journey and Residence in the Interior

: He is brought a king bird-of-paradise, amusing the islanders with his excitement; it had been one of his goals for travelling to the archipelago. He reflects on how their beauty is wasted in the "dark and gloomy woods, with no intelligent eye to gaze upon their loveliness", but that when "civilized man" reaches the islands he will certainly upset the balance of nature and make the birds extinct.Wallace, 1869. Volume 2, pp. 222–224. He finds the men the most beautiful of all the peoples he has stayed among, the women less handsome "except in extreme youth".Wallace, 1869. Volume 2, p. 254.

;32 The Aru Islands—Second Residence in Dobbo

: He sees a cock-fight in the street, but is more interested in a game of football, played with a hollow ball of rattan, and remarks the "excessive cheapness"Wallace, 1869. Volume 2, p. 271. of all goods including those made in Europe or America, which he believes causes idleness and drunkenness because there is no need to work hard to obtain goods. He admires a crimson-flowered tree surrounded with flocks of blue and orange lories. He is given some birds' nest soup, which he found almost tasteless.

;33 The Aru Islands—Physical Geography and Aspects of Nature

: The islands are completely crossed by three narrow channels which resemble and are called rivers, though they are inlets of the sea. The wildlife is much like that of New Guinea, 150 miles (240 km) away, which he supposes was once connected by a land bridge. Most flowers are green; large and showy flowers are rare or absent.

;34  ;40 The Races of Man in the Malay Archipelago

: Wallace ends the book by describing his views on the peoples of the archipelago. He finds the Malays, such as the Javanese, the most civilised, though he describes the Dyaks of Borneo and the Bataks of Sumatra, among others, as "the savage Malays".Wallace, 1869. Volume 2, p. 441. He quotes the traveller Nicolo Conti's 1430 account of them, with other early descriptions. He thinks the Papuan the opposite of the Malay, impulsive and demonstrative where the Malay is impassive and taciturn. He speculates about their origins, and in a note at the end, criticises English society.

;40 The Races of Man in the Malay Archipelago

: Wallace ends the book by describing his views on the peoples of the archipelago. He finds the Malays, such as the Javanese, the most civilised, though he describes the Dyaks of Borneo and the Bataks of Sumatra, among others, as "the savage Malays".Wallace, 1869. Volume 2, p. 441. He quotes the traveller Nicolo Conti's 1430 account of them, with other early descriptions. He thinks the Papuan the opposite of the Malay, impulsive and demonstrative where the Malay is impassive and taciturn. He speculates about their origins, and in a note at the end, criticises English society.

The ''Journal of the Ethnological Society of London'' focussed exclusively on the ethnology in the book, praising the value both of the information and of Wallace's "thoughtful and suggestive speculation". The review notes that Wallace identified two "types of mankind" in the archipelago, "the Malayan and the Papuan", and that he thought these two had "no traceable affinity to each other". It remarks that Wallace greatly extends knowledge of the people of Timor, Celebes, and the Maluccas, while also adding to what is known of the Malays and Papuans, reprinting his entire description and his engraving of a Papuan. The reviewer remarks that the portrait "would as well suit a Papuan of the south-east coast of New Guinea as any of those whom Mr. Wallace saw", noting however that the southern tribes are more varied in skin colour. The reviewer disagrees with Wallace about the extension of this "Papuan race" as far as Fiji, noting that there are or were people like that in Tasmania, but that their features and height varied widely, perhaps forming a series. The reviewer disagrees also that the Sandwich Islanders and "New Zealanders" (Maori) are related to the Papuans; and with Wallace's claim that the presence of Malay words in Polynesian languages is caused by the "roaming habits" – trade and navigation – of the Malays, arguing instead that the Polynesians long ago migrated from "some common seat in, or near, the Malay Archipelago". The review ends by stating that despite all these disagreements, it holds Wallace's ethnology in "high estimation".

The ''Journal of the Ethnological Society of London'' focussed exclusively on the ethnology in the book, praising the value both of the information and of Wallace's "thoughtful and suggestive speculation". The review notes that Wallace identified two "types of mankind" in the archipelago, "the Malayan and the Papuan", and that he thought these two had "no traceable affinity to each other". It remarks that Wallace greatly extends knowledge of the people of Timor, Celebes, and the Maluccas, while also adding to what is known of the Malays and Papuans, reprinting his entire description and his engraving of a Papuan. The reviewer remarks that the portrait "would as well suit a Papuan of the south-east coast of New Guinea as any of those whom Mr. Wallace saw", noting however that the southern tribes are more varied in skin colour. The reviewer disagrees with Wallace about the extension of this "Papuan race" as far as Fiji, noting that there are or were people like that in Tasmania, but that their features and height varied widely, perhaps forming a series. The reviewer disagrees also that the Sandwich Islanders and "New Zealanders" (Maori) are related to the Papuans; and with Wallace's claim that the presence of Malay words in Polynesian languages is caused by the "roaming habits" – trade and navigation – of the Malays, arguing instead that the Polynesians long ago migrated from "some common seat in, or near, the Malay Archipelago". The review ends by stating that despite all these disagreements, it holds Wallace's ethnology in "high estimation".

The ''American Quarterly Church Review'' admires Wallace's bravery in going alone among the "barbarous races" in a "villainous climate" with all the hardships of travel, and his hard work in skinning, stuffing, drying and bottling so many specimens. Since "As a scientific man he follows Darwin" the review finds "his theories sometimes need as many grains of salt as his specimens." But the review then agrees that the book will "make the world wiser about its more solitary and singular children, hid away over the seas", and opines that no-one will mind paying the price of the book to read about the birds of paradise, "those bird-angels, with flaming wings of crimson and gold and scarlet, who twitter and gambol and make merry among the great island trees, while the Malay hunts for them with his blunt-headed arrows..." The review concludes that the book is a fresh and valuable record of "a remote and romantic land".

The ''American Quarterly Church Review'' admires Wallace's bravery in going alone among the "barbarous races" in a "villainous climate" with all the hardships of travel, and his hard work in skinning, stuffing, drying and bottling so many specimens. Since "As a scientific man he follows Darwin" the review finds "his theories sometimes need as many grains of salt as his specimens." But the review then agrees that the book will "make the world wiser about its more solitary and singular children, hid away over the seas", and opines that no-one will mind paying the price of the book to read about the birds of paradise, "those bird-angels, with flaming wings of crimson and gold and scarlet, who twitter and gambol and make merry among the great island trees, while the Malay hunts for them with his blunt-headed arrows..." The review concludes that the book is a fresh and valuable record of "a remote and romantic land".

The ''Calcutta Review'' starts by noting that this is a book that cannot be done justice in a brief notice, that Wallace is a most eminent naturalist, and chiefly known as a Darwinian; the book was the most interesting to cross the reviewer's desk since Palgrave's ''Arabia'' (1865) and Sir

The ''Calcutta Review'' starts by noting that this is a book that cannot be done justice in a brief notice, that Wallace is a most eminent naturalist, and chiefly known as a Darwinian; the book was the most interesting to cross the reviewer's desk since Palgrave's ''Arabia'' (1865) and Sir

Tim Radford, writing in ''

Tim Radford, writing in ''

Papua WebProject: ''The Malay Archipelago'' – illustrated edition

Internet Archive: ''The Malay Archipelago''

Wallace Online: ''The Malay Archipelago'' – text, images, PDF of 1869 and 1890 editions

*

{{DEFAULTSORT:Malay Archipelago, The 1869 books Evolutionary biology literature English non-fiction literature 1860s in science Works by Alfred Russel Wallace British travel books History of evolutionary biology Environmental non-fiction books English non-fiction books

Alfred Russel Wallace

Alfred Russel Wallace (8 January 1823 – 7 November 1913) was a British natural history, naturalist, explorer, geographer, anthropologist, biologist and illustrator. He is best known for independently conceiving the theory of evolution thro ...

which chronicles his scientific exploration, during the eight-year period 1854 to 1862, of the southern portion of the Malay Archipelago

The Malay Archipelago ( Indonesian/ Malay: , tgl, Kapuluang Malay) is the archipelago between mainland Indochina and Australia. It has also been called the " Malay world," " Nusantara", "East Indies", Indo-Australian Archipelago, Spices Arc ...

including Malaysia

Malaysia ( ; ) is a country in Southeast Asia. The federal constitutional monarchy consists of thirteen states and three federal territories, separated by the South China Sea into two regions: Peninsular Malaysia and Borneo's East Mal ...

, Singapore

Singapore (), officially the Republic of Singapore, is a sovereign island country and city-state in maritime Southeast Asia. It lies about one degree of latitude () north of the equator, off the southern tip of the Malay Peninsula, bor ...

, the islands of Indonesia

Indonesia, officially the Republic of Indonesia, is a country in Southeast Asia and Oceania between the Indian and Pacific oceans. It consists of over 17,000 islands, including Sumatra, Java, Sulawesi, and parts of Borneo and New Gui ...

, then known as the Dutch East Indies

The Dutch East Indies, also known as the Netherlands East Indies ( nl, Nederlands(ch)-Indië; ), was a Dutch colony consisting of what is now Indonesia. It was formed from the nationalised trading posts of the Dutch East India Company, whic ...

, and the island of New Guinea

New Guinea (; Hiri Motu: ''Niu Gini''; id, Papua, or , historically ) is the world's second-largest island with an area of . Located in Oceania in the southwestern Pacific Ocean, the island is separated from Australia by the wide Torres ...

. It was published in two volumes in 1869, delayed by Wallace's ill health and the work needed to describe the many specimens he brought home. The book went through ten editions in the nineteenth century; it has been reprinted many times since, and has been translated into at least twelve languages.

The book describes each island that he visited in turn, giving a detailed account of its physical

Physical may refer to:

* Physical examination, a regular overall check-up with a doctor

* ''Physical'' (Olivia Newton-John album), 1981

** "Physical" (Olivia Newton-John song)

* ''Physical'' (Gabe Gurnsey album)

* "Physical" (Alcazar song) (2004)

* ...

and human geography

Human geography or anthropogeography is the branch of geography that studies spatial relationships between human communities, cultures, economies, and their interactions with the environment. It analyzes spatial interdependencies between social ...

, its volcano

A volcano is a rupture in the crust of a planetary-mass object, such as Earth, that allows hot lava, volcanic ash, and gases to escape from a magma chamber below the surface.

On Earth, volcanoes are most often found where tectonic plates ...

es, and the variety of animals and plants that he found and collected. At the same time, he describes his experiences, the difficulties of travel, and the help he received from the different peoples that he met. The preface notes that he travelled over 14,000 miles and collected 125,660 natural history specimens, mostly of insects though also thousands of molluscs, bird

Birds are a group of warm-blooded vertebrates constituting the class Aves (), characterised by feathers, toothless beaked jaws, the laying of hard-shelled eggs, a high metabolic rate, a four-chambered heart, and a strong yet lightweig ...

s, mammal

Mammals () are a group of vertebrate animals constituting the class Mammalia (), characterized by the presence of mammary glands which in females produce milk for feeding (nursing) their young, a neocortex (a region of the brain), fur ...

s and reptile

Reptiles, as most commonly defined are the animals in the class Reptilia ( ), a paraphyletic grouping comprising all sauropsids except birds. Living reptiles comprise turtles, crocodilians, squamates ( lizards and snakes) and rhynchocephalia ...

s.

The work was illustrated with engravings, based on Wallace's observations and collection, by the leading illustrators Thomas Baines

(John) Thomas Baines (27 November 1820 – 8 May 1875) was an English artist and explorer of British colonial southern Africa and Australia.

Life and work

Born in King's Lynn, Norfolk, on 27 November 1820, Baines was apprenticed to a coach p ...

, Walter Hood Fitch

Walter Hood Fitch (28 February 1817 – 1892) was a botanical illustrator, born in Glasgow, Scotland, who executed some 10,000 drawings for various publications.

His work in colour lithograph, including 2700 illustrations for ''Curtis's Bot ...

, John Gerrard Keulemans, E. W. Robinson, Joseph Wolf and T. W. Wood

T. W. Wood (born Thomas Wood, summer 1839 – c. 1910) was an English zoological illustrator responsible for the accurate drawings in major nineteenth century works of natural history including Darwin's ''The Descent of Man'' and Wallace's ...

.

''The Malay Archipelago'' attracted many reviews, with interest from scientific, geographic, church and general periodicals. Reviewers noted and sometimes disagreed with various of his theories, especially the division of fauna

Fauna is all of the animal life present in a particular region or time. The corresponding term for plants is '' flora'', and for fungi, it is '' funga''. Flora, fauna, funga and other forms of life are collectively referred to as '' biota''. ...

and flora

Flora is all the plant life present in a particular region or time, generally the naturally occurring ( indigenous) native plants. Sometimes bacteria and fungi are also referred to as flora, as in the terms '' gut flora'' or '' skin flora''.

...

along what soon became known as the Wallace line, natural selection

Natural selection is the differential survival and reproduction of individuals due to differences in phenotype. It is a key mechanism of evolution, the change in the heritable traits characteristic of a population over generations. Cha ...

and uniformitarianism. Nearly all agreed that he had provided an interesting and comprehensive account of the geography

Geography (from Greek: , ''geographia''. Combination of Greek words ‘Geo’ (The Earth) and ‘Graphien’ (to describe), literally "earth description") is a field of science devoted to the study of the lands, features, inhabitants, an ...

, natural history, and peoples of the archipelago, which was little known to their readers at the time, and that he had collected an astonishing number of specimens. The book is much cited, and is Wallace's most successful, both commercially and as a piece of literature.

Context

In 1847, Wallace and his friend Henry Walter Bates, both in their early twenties, agreed that they would jointly make a collecting trip to the Amazon "towards solving the problem of origin of species". (Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all species of life have descended ...

's book on the '' Origin of Species'' was not published until 11 years later, in 1859. It was based on Darwin's own long collecting trip on HMS ''Beagle'', its publication precipitated by a famous letter from Wallace, sent during the period covered by ''The Malay Archipelago'' while he was staying in Ternate, which described the theory of evolution

Evolution is change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to offspring during reproduction. Variation ...

by natural selection

Natural selection is the differential survival and reproduction of individuals due to differences in phenotype. It is a key mechanism of evolution, the change in the heritable traits characteristic of a population over generations. Cha ...

in outline.) Wallace and Bates had been inspired by reading the American entomologist

Entomology () is the scientific study of insects, a branch of zoology. In the past the term "insect" was less specific, and historically the definition of entomology would also include the study of animals in other arthropod groups, such as ara ...

William Henry Edwards's pioneering 1847 book ''A Voyage Up the River Amazon, with a residency at Pará''. Bates stayed in the Amazons for 11 years, going on to write '' The Naturalist on the River Amazons'' (1863); however, Wallace, ill with fever, went home in 1852 with thousands of specimens, some for science and some for sale. The ship and his collection were destroyed by fire at sea near the Guianas. Rather than giving up, Wallace wrote about the Amazon in both prose and poetry, and then set sail again, this time for the Malay Archipelago.

Overview

The preface summarises Wallace's travels, the thousands of specimens he collected, and some of the results from their analysis after his return to England. In the preface he notes that he travelled over 14,000 miles and collected 125,660 specimens, mostly of insects: 83,200beetle

Beetles are insects that form the order Coleoptera (), in the superorder Endopterygota. Their front pair of wings are hardened into wing-cases, elytra, distinguishing them from most other insects. The Coleoptera, with about 400,000 describ ...

s, 13,100 butterflies and moths, 13,400 other insects. He also returned to England 7,500 "shells" (such as molluscs), 8,050 birds, 310 mammal

Mammals () are a group of vertebrate animals constituting the class Mammalia (), characterized by the presence of mammary glands which in females produce milk for feeding (nursing) their young, a neocortex (a region of the brain), fur ...

s and 100 reptiles.Wallace, 1869. p. xiv.

The book is dedicated to

The book is dedicated to Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all species of life have descended ...

, but as Wallace explains in the preface, he has chosen to avoid discussing the evolution

Evolution is change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to offspring during reproduction. Variation ...

ary implications of his discoveries. Instead he confines himself to the "interesting facts of the problem, whose solution is to be found in the principles developed by Mr. Darwin",Wallace, 1869. p. xii. so from a scientific point of view, the book is largely a descriptive natural history. This modesty belies the fact that while in Sarawak

Sarawak (; ) is a state of Malaysia. The largest among the 13 states, with an area almost equal to that of Peninsular Malaysia, Sarawak is located in northwest Borneo Island, and is bordered by the Malaysian state of Sabah to the northeast, ...

in 1855 Wallace wrote the paper ''On the Law which has Regulated the Introduction of New Species'', concluding with the evolutionary "Sarawak Law", "Every species has come into existence coincident both in space and time with a closely allied species", three years before he fatefully wrote to Darwin proposing the concept of natural selection

Natural selection is the differential survival and reproduction of individuals due to differences in phenotype. It is a key mechanism of evolution, the change in the heritable traits characteristic of a population over generations. Cha ...

.

The first chapter describes the physical geography

Physical geography (also known as physiography) is one of the three main branches of geography. Physical geography is the branch of natural science which deals with the processes and patterns in the natural environment such as the atmosphere ...

and geology of the islands with particular attention to the role of volcanoes

A volcano is a rupture in the crust of a planetary-mass object, such as Earth, that allows hot lava, volcanic ash, and gases to escape from a magma chamber below the surface.

On Earth, volcanoes are most often found where tectonic plates a ...

and earthquakes. It also discusses the overall pattern of the flora and fauna including the fact that the islands can be divided, by what would eventually become known as the Wallace line, into two parts, those whose animals are more closely related to those of Asia and those whose fauna is closer to that of Australia.Wallace, 1869. Volume 1, pp. 1–30.

The following chapters describe in detail the places Wallace visited. Wallace includes numerous observations on the people, their languages, ways of living, and social organisation, as well as on the plants and animals found in each location. He talks about the biogeographic patterns he observes and their implications for natural history, in terms both of the movement of species and of the geologic history of the region. He also narrates some of his personal experiences during his travels.Wallace, 1869. The final chapter is an overview of the ethnic, linguistic, and cultural divisions among the people who live in the region and speculation about what such divisions might indicate about their history.Wallace, 1869. Volume 2, pp. 439–464.

Publication

''The Malay Archipelago'' was largely written at Treeps, Wallace's wife's family home in

''The Malay Archipelago'' was largely written at Treeps, Wallace's wife's family home in Hurstpierpoint

Hurstpierpoint is a village in West Sussex, England, southwest of Burgess Hill, and west of Hassocks railway station. It sits in the civil parish of Hurstpierpoint and Sayers Common which has an area of 2029.88 ha and a population ...

, West Sussex

West Sussex is a county in South East England on the English Channel coast. The ceremonial county comprises the shire districts of Adur, Arun, Chichester, Horsham, and Mid Sussex, and the boroughs of Crawley and Worthing. Covering an ...

. It was first published in Spring 1869 as a single volume first edition, however was reprinted in two volumes by Macmillan (London), marked second edition the same year by Harper & Brothers (New York). Wallace returned to England in 1862, but explains in the Preface that given the large quantity of specimens and his poor health after his stay in the tropics, it took a long time. He noted that he could at once have printed his notes and journals, but felt that doing that would have been disappointing and unhelpful. Instead, therefore, he waited until he had published papers on his discoveries, and other scientists had described and named as new species some 2,000 of his beetles (Coleoptera

Beetles are insects that form the order Coleoptera (), in the superorder Endopterygota. Their front pair of wings are hardened into wing-cases, elytra, distinguishing them from most other insects. The Coleoptera, with about 400,000 describe ...

), and over 900 Hymenoptera

Hymenoptera is a large order of insects, comprising the sawflies, wasps, bees, and ants. Over 150,000 living species of Hymenoptera have been described, in addition to over 2,000 extinct ones. Many of the species are parasitic.

Females typic ...

including 200 new species of ant.Wallace, 1869. pp. vii–ix. The book went through 10 editions, with the last published in 1890. It has been translated into at least twelve languages.

Illustrations

The illustrations are, according to the ''Preface'', made from Wallace's own sketches, photographs, or specimens. Wallace thanks Walter and Henry Woodbury for some photographs of scenery and native people. He acknowledges William Wilson Saunders and Mr Pascoe for horned flies and very rare longhorn beetles: all the rest were from his own enormous collection.

The original drawings were made directly on to the

The illustrations are, according to the ''Preface'', made from Wallace's own sketches, photographs, or specimens. Wallace thanks Walter and Henry Woodbury for some photographs of scenery and native people. He acknowledges William Wilson Saunders and Mr Pascoe for horned flies and very rare longhorn beetles: all the rest were from his own enormous collection.

The original drawings were made directly on to the wood engraving

Wood engraving is a printmaking technique, in which an artist works an image or ''matrix'' of images into a block of wood. Functionally a variety of woodcut, it uses relief printing, where the artist applies ink to the face of the block and ...

blocks by leading artists Thomas Baines

(John) Thomas Baines (27 November 1820 – 8 May 1875) was an English artist and explorer of British colonial southern Africa and Australia.

Life and work

Born in King's Lynn, Norfolk, on 27 November 1820, Baines was apprenticed to a coach p ...

, Walter Hood Fitch

Walter Hood Fitch (28 February 1817 – 1892) was a botanical illustrator, born in Glasgow, Scotland, who executed some 10,000 drawings for various publications.

His work in colour lithograph, including 2700 illustrations for ''Curtis's Bot ...

, John Gerrard Keulemans, E. W. Robinson, Joseph Wolf, and T. W. Wood

T. W. Wood (born Thomas Wood, summer 1839 – c. 1910) was an English zoological illustrator responsible for the accurate drawings in major nineteenth century works of natural history including Darwin's ''The Descent of Man'' and Wallace's ...

, according to the ''List of Illustrations''. Wood also illustrated Darwin's ''The Descent of Man

''The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex'' is a book by English naturalist Charles Darwin, first published in 1871, which applies evolutionary theory to human evolution, and details his theory of sexual selection, a form of biol ...

'', while Robinson and Wolf both also provided illustrations for '' The Naturalist on the River Amazons'' (1863), written by Wallace's friend Henry Walter Bates.

Contents

Volume 1

;1 Physical Geography : Wallace sets out the scope of the book, describing what "To the ordinary Englishman" is "perhaps the least known part of the globe."Wallace, 1869. Volume 1, p. 2. The archipelago, he explains, stretches more than 4,000 miles east to west, and about 1,300 miles north to south, with over twenty sizeable islands and innumerable isles and islets.Indo-Malay Islands

;2 Singapore

: Wallace gives a lively description of the people of the town, and of the wildlife of the island. He finds the Chinese the most noticeable of the people, while in one square mile of forest he found 700 species of beetles including 130 longhorns.

;3

;2 Singapore

: Wallace gives a lively description of the people of the town, and of the wildlife of the island. He finds the Chinese the most noticeable of the people, while in one square mile of forest he found 700 species of beetles including 130 longhorns.

;3 Malacca

Malacca ( ms, Melaka) is a States and federal territories of Malaysia, state in Malaysia located in the southern region of the Malay Peninsula, next to the Strait of Malacca. Its capital is Malacca City, dubbed the Historic City, which has bee ...

and Mount Ophir.

: He finds an attractive old Portuguese town, and beautiful birds such as the blue-billed gaper. The flora includes pitcher plants and giant ferns. There are tigers and rhinoceros, but the elephants had already disappeared.

;4 Borneo

Borneo (; id, Kalimantan) is the third-largest island in the world and the largest in Asia. At the geographic centre of Maritime Southeast Asia, in relation to major Indonesian islands, it is located north of Java, west of Sulawesi, and e ...

—The Orang-Utan

: He stays in Sarawak

Sarawak (; ) is a state of Malaysia. The largest among the 13 states, with an area almost equal to that of Peninsular Malaysia, Sarawak is located in northwest Borneo Island, and is bordered by the Malaysian state of Sabah to the northeast, ...

, and finds the Simunjon coal-works convenient, as the workers are happy to be paid a little for insects they find, including locusts, stick insects and about 24 new species of beetles each day. In all he collects 2000 species of beetle in Borneo, nearly all at the coal mine site; he also found a flying frog and orang-utan

Orangutans are great apes native to the rainforests of Indonesia and Malaysia. They are now found only in parts of Borneo and Sumatra, but during the Pleistocene they ranged throughout Southeast Asia and South China. Classified in the genus ' ...

s in the same place.

;5 Borneo—Journey in the Interior

: Wallace returns to Sarawak, where he stays in the circular 'head-house' of a Dyak village, travels upriver, and describes the Durian, praising it as the king of fruits with exquisite and unsurpassed flavour,Wallace, 1869. Volume 1, pp. 117–119. and the Dyak's slender bamboo bridges,Wallace, 1869. Volume 1, pp. 123–124. as well as ferns and ''

;5 Borneo—Journey in the Interior

: Wallace returns to Sarawak, where he stays in the circular 'head-house' of a Dyak village, travels upriver, and describes the Durian, praising it as the king of fruits with exquisite and unsurpassed flavour,Wallace, 1869. Volume 1, pp. 117–119. and the Dyak's slender bamboo bridges,Wallace, 1869. Volume 1, pp. 123–124. as well as ferns and ''Nepenthes

''Nepenthes'' () is a genus of carnivorous plants, also known as tropical pitcher plants, or monkey cups, in the monotypic family Nepenthaceae. The genus includes about 170 species, and numerous natural and many cultivated hybrids. They are mo ...

'' pitcher plants. On a mountain he finds the only place in his entire journey where moth

Moths are a paraphyletic group of insects that includes all members of the order Lepidoptera that are not butterflies, with moths making up the vast majority of the order. There are thought to be approximately 160,000 species of moth, many of w ...

s are abundant; he collected 1,386 moths on a total of 26 nights, but over 800 of these were caught on four very wet and dark nights. He attributes the reason to having a ceiling that effectively trapped the moths; in other houses the moths at once escaped into the roof, and he recommends naturalists to bring a verandah-shaped tent to enable them to catch moths.Wallace, 1869. Volume 1, pp. 132–136.

;6 Borneo—The Dyaks

: Wallace describes the Dyak people, expressing surprise that despite Thomas Malthus

Thomas Robert Malthus (; 13/14 February 1766 – 29 December 1834) was an English cleric, scholar and influential economist in the fields of political economy and demography.

In his 1798 book ''An Essay on the Principle of Population'', Mal ...

's predictions for the human population of the world, and the lack of any obvious restraints, the Dyak population appeared to be stable.

;7 Java

Java (; id, Jawa, ; jv, ꦗꦮ; su, ) is one of the Greater Sunda Islands in Indonesia. It is bordered by the Indian Ocean to the south and the Java Sea to the north. With a population of 151.6 million people, Java is the world's mo ...

: Wallace stayed three and a half months in Java, where he admires the system of government and the contented people. The population is, he notes, rapidly increasing, from 3.5 million in 1800 to 5.5 million in 1826 and 14 million in 1865. He enjoys the fine Hindu archaeological sites, and the flora of the mountain tops which have plants resembling those of Europe, including the royal cowslip, ''Primula imperialis'', endemic

Endemism is the state of a species being found in a single defined geographic location, such as an island, state, nation, country or other defined zone; organisms that are indigenous to a place are not endemic to it if they are also found else ...

to one mountain top.

;8 Sumatra

Sumatra is one of the Sunda Islands of western Indonesia. It is the largest island that is fully within Indonesian territory, as well as the sixth-largest island in the world at 473,481 km2 (182,812 mi.2), not including adjacent i ...

: He visits Sumatra while the coastal forest of '' Nipa'' palms is flooded to a distance of several miles from the sea. The river houses at Palembang are built on rafts moored to piles, rising and falling with the tide. He admires the traditional houses of the villages, but had difficulty getting any food there, the people living entirely on rice through the rainy season. He discovers some new species of butterfly including '' Papilio memnon'' which occurs in different forms, some being Batesian mimics of '' Papilio coon''. He admires the camouflage

Camouflage is the use of any combination of materials, coloration, or illumination for concealment, either by making animals or objects hard to see, or by disguising them as something else. Examples include the leopard's spotted coat, the b ...

of a species of dead leaf butterfly, '' Kallima paralekta''. He is pleased that one of his hunters brings him a male hornbill

Hornbills (Bucerotidae) are a family of bird found in tropical and subtropical Africa, Asia and Melanesia. They are characterized by a long, down-curved bill which is frequently brightly coloured and sometimes has a casque on the upper mandibl ...

, shot at its nest hole while feeding the female.

;9 Natural History Of The Indo-Malay Islands.

: Wallace sketches the natural history of the islands to the West of the Wallace line, noting that the flora is like that of India, as described by the botanist

Botany, also called , plant biology or phytology, is the science of plant life and a branch of biology. A botanist, plant scientist or phytologist is a scientist who specialises in this field. The term "botany" comes from the Ancient Greek wo ...

Joseph Dalton Hooker in his 1855 ''Flora Indica''. Similarly the mammals are similar to those of India, including the tiger, leopard

The leopard (''Panthera pardus'') is one of the five extant species in the genus '' Panthera'', a member of the cat family, Felidae. It occurs in a wide range in sub-Saharan Africa, in some parts of Western and Central Asia, Southern Russia, ...

, rhinoceros

A rhinoceros (; ; ), commonly abbreviated to rhino, is a member of any of the five extant species (or numerous extinct species) of odd-toed ungulates in the family Rhinocerotidae. (It can also refer to a member of any of the extinct specie ...

and elephant. The bird species had diverged, but the genera

Genus ( plural genera ) is a taxonomic rank used in the biological classification of living and fossil organisms as well as viruses. In the hierarchy of biological classification, genus comes above species and below family. In binomial nomenclat ...

were mainly the same, and some species of (for example) woodpecker, parrot, kingfisher and pheasant were found from India to Java and Borneo, while many more were found both in Sumatra and the Malay peninsula.

The Timor Group

;10

;10 Bali

Bali () is a province of Indonesia and the westernmost of the Lesser Sunda Islands. East of Java and west of Lombok, the province includes the island of Bali and a few smaller neighbouring islands, notably Nusa Penida, Nusa Lembongan, and ...

And Lombock

: Wallace is grateful for an involuntary stop in Bali, which he finds one of the most interesting places of his trip, as Hindu customs and religion are still practised, while on Lombok he finds Australian birds such as cockatoos, observing that this is the most westerly point of that family's range.

;11 Lombock—Manners And Customs

: On Lombok, Wallace observes how guns are made, witnessing the boring of gun barrels by two men rotating a pole which is weighted down by a basket of stones. He describes the Sasak people of the island, and the custom of running amok.

;12 Lombock—How The Rajah Took The Census

: The whole chapter is taken up with a legend, which Wallace calls an anecdote, about the rajah (king) of Lombok. It involves taxation, needles and sacred kris

The kris, or ''keris'' in the Indonesian language, is an asymmetrical dagger with distinctive blade-patterning achieved through alternating laminations of iron and nickelous iron (''pamor''). Of Javanese origin, the kris is famous for its dist ...

ses.

;13 Timor

Timor is an island at the southern end of Maritime Southeast Asia, in the north of the Timor Sea. The island is divided between the sovereign states of East Timor on the eastern part and Indonesia on the western part. The Indonesian part, ...

: Wallace describes the island of Timor, its abundance of fan-palms, its people who are like Papuans, and the Portuguese government which he considers extremely poor. On some hills he finds ''Eucalyptus

''Eucalyptus'' () is a genus of over seven hundred species of flowering trees, shrubs or mallees in the myrtle family, Myrtaceae. Along with several other genera in the tribe Eucalypteae, including '' Corymbia'', they are commonly known as ...

'' (gum) trees, a genus from Australia; he finds the vegetation monotonous also.

;14 Natural History of the Timor Group

: He finds the mixture of bird species intermediate between those of Java and Australia, with 36 species actually Javan, and 11 closely related; while there are only 13 actually Australian, with 35 closely related. Wallace interprets this to mean that a small number of birds from Australia, and a larger number from Java, colonised Timor and then evolved into new species endemic to the island. The land mammals were very few in number: the six species were endemic or related to those of Java or the Moluccas, with none from Australia, so he doubts there was ever a land bridge to that continent.

The Celebes Group

;15 Celebes—Macassar

: Wallace finds staying in the town of Macassar expensive, and moves out into the countryside. He meets the rajah, and is lucky enough to stay on a farm where he is given a glass of milk every day, "one of my greatest luxuries".Wallace, 1869. Volume 1, p. 355.

;16 Celebes—Macassar

: He catches some '' Ornithoptera'' (birdwings), "the largest, the most perfect, and the most beautiful of butterflies".Wallace, 1869. Volume 1, p. 364. He uses rotten jackfruit to attract beetles, but finds few birds. The limestone mountains are eroded into skittle-shaped pillars with narrow bases.

;17 Celebes—Menado

: Wallace visits Menado on the northeast coast of Celebes. The people of the Minahasa region are fair-skinned, unlike anywhere else in the archipelago. He stays high in the mountains by the coffee plantations, and is often cold, but finds that the animals are no different from those lower down. The forest was full of

;15 Celebes—Macassar

: Wallace finds staying in the town of Macassar expensive, and moves out into the countryside. He meets the rajah, and is lucky enough to stay on a farm where he is given a glass of milk every day, "one of my greatest luxuries".Wallace, 1869. Volume 1, p. 355.

;16 Celebes—Macassar

: He catches some '' Ornithoptera'' (birdwings), "the largest, the most perfect, and the most beautiful of butterflies".Wallace, 1869. Volume 1, p. 364. He uses rotten jackfruit to attract beetles, but finds few birds. The limestone mountains are eroded into skittle-shaped pillars with narrow bases.

;17 Celebes—Menado

: Wallace visits Menado on the northeast coast of Celebes. The people of the Minahasa region are fair-skinned, unlike anywhere else in the archipelago. He stays high in the mountains by the coffee plantations, and is often cold, but finds that the animals are no different from those lower down. The forest was full of orchids

Orchids are plants that belong to the family Orchidaceae (), a diverse and widespread group of flowering plants with blooms that are often colourful and fragrant.

Along with the Asteraceae, they are one of the two largest families of flowering ...

, bromeliads, clubmosses

Lycopodiopsida is a class of vascular plants known as lycopods, lycophytes or other terms including the component lyco-. Members of the class are also called clubmosses, firmosses, spikemosses and quillworts. They have dichotomously branching ...

and moss

Mosses are small, non-vascular flowerless plants in the taxonomic division Bryophyta (, ) '' sensu stricto''. Bryophyta ('' sensu lato'', Schimp. 1879) may also refer to the parent group bryophytes, which comprise liverworts, mosses, and ...

es. He experiences an earthquake, but the low timber-framed houses survive with little damage. He finds that the people, under the guidance of missionaries

A missionary is a member of a religious group which is sent into an area in order to promote its faith or provide services to people, such as education, literacy, social justice, health care, and economic development.Thomas Hale 'On Being a Mi ...

, are the most hard-working, peaceful and civilised of the whole archipelago. He obtains (apparently by purchase) skulls of the babirusa

The babirusas, also called deer-pigs ( id, babi rusa), are a genus, ''Babyrousa'', in the swine family found in the Indonesian islands of Sulawesi, Togian, Sula and Buru. All members of this genus were considered part of a single species un ...

(pig-deer) and the rare sapiutan (midget buffalo).

;18 Natural History of Celebes

: He describes the range of species in each group in some detail, concluding that the birds are unlike those of any of the surrounding countries and are quite isolated, but are related to those of distant places including New Guinea, Australia, India and Africa; he thinks there is nowhere else where so many such species occur in one place. Similarly in the Nymphalidae (he mentions the English member, the purple emperor

''Apatura iris'', the purple emperor, is a Palearctic butterfly of the family Nymphalidae.

Description

Adults have dark brown wings with white bands and spots, and a small orange ring on each of the hindwings. Males have a wingspan of , and ...

butterfly), there are 48 species of which 35 are endemic to Celebes. He concludes that the Celebes group of islands is a major faunal division of the archipelago.

The Moluccas

;19Banda

Banda may refer to:

People

* Banda (surname)

* Banda Prakash (born 1954), Indian politician

* Banda Kanakalingeshwara Rao (1907–1968), Indian actor

* Banda Karthika Reddy (born 1977), Indian politician

*Banda Singh Bahadur (1670–1716), Sikh ...

: He finds Banda delightful, with a smoking volcano and a fine view from the top. The nutmeg

Nutmeg is the seed or ground spice of several species of the genus ''Myristica''. ''Myristica fragrans'' (fragrant nutmeg or true nutmeg) is a dark-leaved evergreen tree cultivated for two spices derived from its fruit: nutmeg, from its seed, an ...

trees are beautiful but he regrets the ending of the Dutch monopoly in the nutmeg trade, which avoided the need to levy direct taxes. The only indigenous animals, he thinks, are bats, except possibly for its opossum

Opossums () are members of the marsupial order Didelphimorphia () endemic to the Americas. The largest order of marsupials in the Western Hemisphere, it comprises 93 species in 18 genera. Opossums originated in South America and entered No ...

species.

;20 Amboyna

: He finds the inhabitants of Amboyna lazy, but the harbour contained the most beautiful sight, "a continuous series of coral

Corals are marine invertebrates within the class Anthozoa of the phylum Cnidaria. They typically form compact colonies of many identical individual polyps. Coral species include the important reef builders that inhabit tropical oceans and se ...

s, sponge

Sponges, the members of the phylum Porifera (; meaning 'pore bearer'), are a basal animal clade as a sister of the diploblasts. They are multicellular organisms that have bodies full of pores and channels allowing water to circulate throu ...

s, actiniæ, and other marine productions, of magnificent dimensions, varied forms, and brilliant colours."Wallace, 1869. Volume 1, p. 463. A large python has to be ejected from the roof-space of his house. He enjoys the true breadfruit

Breadfruit (''Artocarpus altilis'') is a species of flowering tree in the mulberry and jackfruit family ( Moraceae) believed to be a domesticated descendant of '' Artocarpus camansi'' originating in New Guinea, the Maluku Islands, and the Phil ...

, which he considers good in many dishes but best simply baked.

Volume 2

The Moluccas (continued)

;21 Ternate : Wallace takes on and repairs a house which he keeps for three years, drawing a plan of it in the book; it has stone walls 3 feet (1 metre) high, with posts holding up the roof; the walls and ceiling are made of the leaf-stems of the sago palm. He has a well of clean cold water, and the market provides "unwonted luxuries" of fresh food; he returns here to restore his health after arduous journeys. ;22 Gilolo : He finds the large island rather dull, with much tall coarse grass and few species. In the forest he obtains some small "parroquets", brush-tongued lories, and the day-flying moth '' Cocytia d'Urvillei''. ;23 Voyage to the Kaióa Islands and Batchian

: He hires a small boat to go to the highly recommended island of Batchian and crosses to Tidore, where he sees the comet of October 1858; it spans about 20 degrees of the night sky. They sail past the volcanic island of Makian which erupted in 1646 and devastatingly again, soon after Wallace had left the archipelago, in 1862. In the Kaióa Islands he finds some virgin forest where the beetles are more abundant than anywhere he ever saw in his life, with swarms of golden

;23 Voyage to the Kaióa Islands and Batchian

: He hires a small boat to go to the highly recommended island of Batchian and crosses to Tidore, where he sees the comet of October 1858; it spans about 20 degrees of the night sky. They sail past the volcanic island of Makian which erupted in 1646 and devastatingly again, soon after Wallace had left the archipelago, in 1862. In the Kaióa Islands he finds some virgin forest where the beetles are more abundant than anywhere he ever saw in his life, with swarms of golden Buprestidae

Buprestidae is a family of beetles known as jewel beetles or metallic wood-boring beetles because of their glossy iridescent colors. Larvae of this family are known as flatheaded borers. The family is among the largest of the beetles, with some ...

, rose-chafers, and long-horned weevils, as well as longicorn beetles. "It was a glorious spot, and one which will always live in my memory as exhibiting the insect-life of the tropics in unexampled luxuriance."Wallace, 1869. Volume 2, p. 32.

;24 Batchian

: He is lent a house by the Sultan, who offers him tea and cakes but asks him to teach him to make maps and to give him a gun and a milking goat, "all of which requests I evaded as skilfully as I was able".Wallace, 1869. Volume 2, p. 38. His servant Ali shoots a new bird of paradise, Wallace's standardwing, "a great prize" and a "striking novelty".Wallace, 1869. Volume 2, p. 41. He is a little disappointed in the range of insects and birds, but discovers new species of

;24 Batchian

: He is lent a house by the Sultan, who offers him tea and cakes but asks him to teach him to make maps and to give him a gun and a milking goat, "all of which requests I evaded as skilfully as I was able".Wallace, 1869. Volume 2, p. 38. His servant Ali shoots a new bird of paradise, Wallace's standardwing, "a great prize" and a "striking novelty".Wallace, 1869. Volume 2, p. 41. He is a little disappointed in the range of insects and birds, but discovers new species of roller

Roller may refer to:

Birds

*Roller, a bird of the family Coraciidae

* Roller (pigeon), a domesticated breed or variety of pigeon

Devices

* Roller (agricultural tool), a non-powered tool for flattening ground

* Road roller, a vehicle for compa ...

, sunbird and is happy to see the racquet-tailed kingfisher. His house is burgled twice; a blacksmith manages to pick his locks and make him a new set of keys; and he discovers a new species of birdwing butterfly.

;25 Ceram, Goram, and the Matabello Islands

: He travels to Ceram, where he enjoys the company of a multilingual Flemish

Flemish (''Vlaams'') is a Low Franconian dialect cluster of the Dutch language. It is sometimes referred to as Flemish Dutch (), Belgian Dutch ( ), or Southern Dutch (). Flemish is native to Flanders, a historical region in northern Belgium; ...

plantation owner. He finds few birds despite constant searching and wading through rivers; the water and the rough ground destroy both his pairs of shoes, and he returns home on the last day lame from walking "in my stockings very painfully".Wallace, 1869. Volume 2, p. 85. Sailing in the Matabello Islands, he is blown ten miles off course, his men fearing being swept on to the coast of New Guinea

New Guinea (; Hiri Motu: ''Niu Gini''; id, Papua, or , historically ) is the world's second-largest island with an area of . Located in Oceania in the southwestern Pacific Ocean, the island is separated from Australia by the wide Torres ...

"in which case we should most likely all be murdered" as the tribes there are treacherous and bloodthirsty.Wallace, 1869. Volume 2, pp. 99–100, 111. He is sorry to see that even the smallest children here all chew betel-nut and are disfigured by sores from a poor diet. However he enjoys their palm wine which he finds more like cider than beer, and the "water" inside young coconuts, which, he explains, is nothing like the undrinkable contents of the old dry coconuts on sale in England. He buys a prau

Proas are various types of multi-hull outrigger sailboats of the Austronesian peoples. The terms were used for native Austronesian ships in European records during the Colonial era indiscriminately, and thus can confusingly refer to the d ...

and surprises the people by fitting it out himself, using tools "of the best London make", but lacking a large drill the holes have to be made, very slowly, by boring with hot iron rods.Wallace, 1869. Volume 2, p. 109. Travelling round Ceram, the crew from Goram run away. He describes in detail the process of making sago.

;26 Bouru

: He finds he has arrived in the rainy season, seeing mainly mud and water. He complains that two months' work produce only 210 species of beetle, compared to 300 in three weeks at Amboyna. However one '' Cerambyx'' beetle was up to 3 inches (7.5 cm) long, with antennae up to 5 inches (12.5 cm) in length. He is amused at himself for finding his simple hut comfortable, once he has made a rough table and is in his rattan

Rattan, also spelled ratan, is the name for roughly 600 species of Old World climbing palms belonging to subfamily Calamoideae. The greatest diversity of rattan palm species and genera are in the closed- canopy old-growth tropical fores ...

chair, with a mosquito net and "large Scotch plaid

Tartan ( gd, breacan ) is a patterned cloth consisting of criss-crossed, horizontal and vertical bands in multiple colours. Tartans originated in woven wool, but now they are made in other materials. Tartan is particularly associated with S ...

" to form a "little sleeping apartment". He gets 17 new (at least for the Moluccas) species of bird including a new '' Pitta'' bird.Wallace, 1869. Volume 2, p. 133.

;27 The Natural History of the Moluccas

: The only carnivore in the Moluccas is the Malayan civet (Musang), which he supposes has been introduced by accident as it is kept for its musk

Musk ( Persian: مشک, ''Mushk'') is a class of aromatic substances commonly used as base notes in perfumery. They include glandular secretions from animals such as the musk deer, numerous plants emitting similar fragrances, and artificial sub ...

. The Celebes Babirusa is, oddly, found on Bouru, which he supposes it reached partly by swimming, citing Sir Charles Lyell

Sir Charles Lyell, 1st Baronet, (14 November 1797 – 22 February 1875) was a Scottish geologist who demonstrated the power of known natural causes in explaining the earth's history. He is best known as the author of ''Principles of Geolo ...

's ''Principles of Geology'' to confirm this ability. The other mammals are marsupial

Marsupials are any members of the mammalian infraclass Marsupialia. All extant marsupials are endemic to Australasia, Wallacea and the Americas. A distinctive characteristic common to most of these species is that the young are carried in ...

, so, he presumes, true natives. In contrast to the few mammals, there are at least 265 bird species, more than all of Europe, which had 257, but of these just three groups – parrots, kingfishers and pigeons – make up nearly a third, compared to only a twentieth of the birds of India. Wallace suggests this is because they came from New Guinea, which has a similar lack of some groups, and adds that many New Guinea birds have not reached the Moluccas, implying that the islands have been isolated for a long time.

Papuan Group

;28 Macassar to the Aru Islands in a Native

;28 Macassar to the Aru Islands in a Native Prau

Proas are various types of multi-hull outrigger sailboats of the Austronesian peoples. The terms were used for native Austronesian ships in European records during the Colonial era indiscriminately, and thus can confusingly refer to the d ...

: Wallace decides to avoid the rainy season of Celebes by travelling to the Aru Islands, the source of pearls

A pearl is a hard, glistening object produced within the soft tissue (specifically the mantle) of a living shelled mollusk or another animal, such as fossil conulariids. Just like the shell of a mollusk, a pearl is composed of calcium carb ...

, mother-of-pearl, and tortoiseshell for Europe, and edible birds' nests and sea-slugs for China, even though they are inhabited by "savages". He is excited despite the danger of a 1,000-mile (1600 km) voyage in a 70-ton Bugis

The Bugis people (pronounced ), also known as Buginese, are an ethnicity—the most numerous of the three major linguistic and ethnic groups of South Sulawesi (the others being Makassar and Toraja), in the south-western province of Sulawesi ...

prau with a crew of 50, considering the islands the "'' Ultima Thule'' of the East". His small cabin was the "snuggest" he ever had at sea, and he liked the natural materials and the absence of foul-smelling paint and tar.Wallace, 1869. Volume 2, pp. 158–162. The Molucca sea was phosphorescent, like a nebula

A nebula ('cloud' or 'fog' in Latin; pl. nebulae, nebulæ or nebulas) is a distinct luminescent part of interstellar medium, which can consist of ionized, neutral or molecular hydrogen and also cosmic dust. Nebulae are often star-forming regio ...

seen in a telescope. He sees flying fish near Teor, which is wrongly marked on the charts.

;29 The Ké Islands

: The prau is greeted by 3 or 4 long high-beaked canoes, about 50 men naked but for shells and long plumes of cassowary

Cassowaries ( tpi, muruk, id, kasuari) are flightless birds of the genus ''Casuarius'' in the order Casuariiformes. They are classified as ratites (flightless birds without a keel on their sternum bones) and are native to the tropical ...

feathers, singing and shouting as they rowed, who board the prow with high exuberance "intoxicated with joy and excitement" asking for tobacco.Wallace, 1869. Volume 2, p. 177. It is at once clear to Wallace these Papuans are not Malays in appearance or behaviour.Wallace, 1869. Volume 2, p. 176. They are expert boat-builders, using only axe, adze and auger, fitting planks together so well that a knife-blade can hardly be inserted anywhere.Wallace, 1869. Volume 2, pp. 184–186. They use no money, bartering for knives, cloth and "arrack" brandy, and bring many beetles including a new jewel beetle

Buprestidae is a family of beetles known as jewel beetles or metallic wood-boring beetles because of their glossy iridescent colors. Larvae of this family are known as flatheaded borers. The family is among the largest of the beetles, with some ...

species, '' Cyphogastra calepyga'', in return for tobacco.

;30 The Aru Islands—Residence in Dobbo

: On one day he captures about 30 species of butterfly, the most since he was in the Amazon

Amazon most often refers to:

* Amazons, a tribe of female warriors in Greek mythology

* Amazon rainforest, a rainforest covering most of the Amazon basin

* Amazon River, in South America

* Amazon (company), an American multinational technolog ...

, including the "large and handsome spectre-butterfly, '' Hestia durvillei''",Wallace, 1869. Volume 2, pp. 199–200. and a few days later

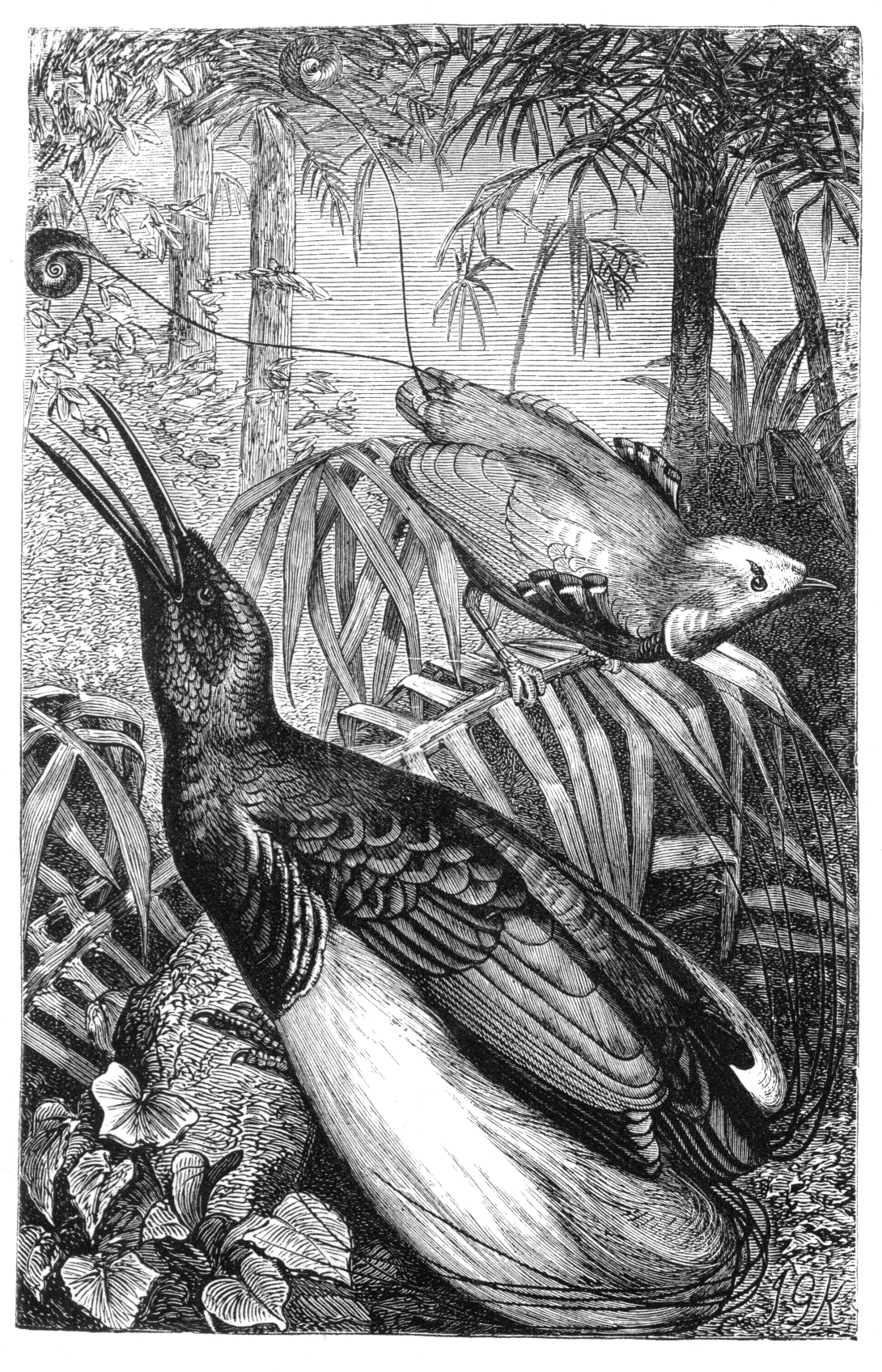

;31 The Aru Islands—Journey and Residence in the Interior

: He is brought a king bird-of-paradise, amusing the islanders with his excitement; it had been one of his goals for travelling to the archipelago. He reflects on how their beauty is wasted in the "dark and gloomy woods, with no intelligent eye to gaze upon their loveliness", but that when "civilized man" reaches the islands he will certainly upset the balance of nature and make the birds extinct.Wallace, 1869. Volume 2, pp. 222–224. He finds the men the most beautiful of all the peoples he has stayed among, the women less handsome "except in extreme youth".Wallace, 1869. Volume 2, p. 254.

;32 The Aru Islands—Second Residence in Dobbo

: He sees a cock-fight in the street, but is more interested in a game of football, played with a hollow ball of rattan, and remarks the "excessive cheapness"Wallace, 1869. Volume 2, p. 271. of all goods including those made in Europe or America, which he believes causes idleness and drunkenness because there is no need to work hard to obtain goods. He admires a crimson-flowered tree surrounded with flocks of blue and orange lories. He is given some birds' nest soup, which he found almost tasteless.

;33 The Aru Islands—Physical Geography and Aspects of Nature

: The islands are completely crossed by three narrow channels which resemble and are called rivers, though they are inlets of the sea. The wildlife is much like that of New Guinea, 150 miles (240 km) away, which he supposes was once connected by a land bridge. Most flowers are green; large and showy flowers are rare or absent.

;34

;31 The Aru Islands—Journey and Residence in the Interior

: He is brought a king bird-of-paradise, amusing the islanders with his excitement; it had been one of his goals for travelling to the archipelago. He reflects on how their beauty is wasted in the "dark and gloomy woods, with no intelligent eye to gaze upon their loveliness", but that when "civilized man" reaches the islands he will certainly upset the balance of nature and make the birds extinct.Wallace, 1869. Volume 2, pp. 222–224. He finds the men the most beautiful of all the peoples he has stayed among, the women less handsome "except in extreme youth".Wallace, 1869. Volume 2, p. 254.

;32 The Aru Islands—Second Residence in Dobbo

: He sees a cock-fight in the street, but is more interested in a game of football, played with a hollow ball of rattan, and remarks the "excessive cheapness"Wallace, 1869. Volume 2, p. 271. of all goods including those made in Europe or America, which he believes causes idleness and drunkenness because there is no need to work hard to obtain goods. He admires a crimson-flowered tree surrounded with flocks of blue and orange lories. He is given some birds' nest soup, which he found almost tasteless.

;33 The Aru Islands—Physical Geography and Aspects of Nature

: The islands are completely crossed by three narrow channels which resemble and are called rivers, though they are inlets of the sea. The wildlife is much like that of New Guinea, 150 miles (240 km) away, which he supposes was once connected by a land bridge. Most flowers are green; large and showy flowers are rare or absent.

;34 New Guinea

New Guinea (; Hiri Motu: ''Niu Gini''; id, Papua, or , historically ) is the world's second-largest island with an area of . Located in Oceania in the southwestern Pacific Ocean, the island is separated from Australia by the wide Torres ...

— Dorey

: He travels to New Guinea after long anticipation. The coastal village houses stand in the water; they have boat-shaped roofs, and often have human skulls hanging under the eaves, trophies of battles with their attackers, the Arfaks. The council house has "revolting" carvings of naked figures. He finds the inhabitants often very handsome, as they are tall with aquiline noses and heads of carefully combed "frizzly" hair.Wallace, 1869. Volume 2, pp. 305–306. He failed to find the birds of paradise described by the French pharmacist and botanist René Primevère Lesson, but is pleased with the horned deer-flies, including ''Elaphomia cervicornis'' and ''E. wallacei''. He injured his ankle and had to rest as it became an ulcer, while all his men had fever, dysentery or ague. When he recovers, birds are scarce, but he finds about 30 species of beetles each day on average; on two memorable days he finds 78 and 95 kinds, his personal record; it takes him 6 hours to pin and lay out the specimens afterwards. In all he collected over 800 species of beetle in Dorey. He leaves "without much regret" as he never visited a place with "more privations and annoyances."Wallace, 1869. Volume 2, p. 327.

;35 Voyage from Ceram to Waigiou

: He is blown far off course while trying to reach his assistant, Mr Allen, losing some men who went ashore, dragging anchor, running on to a coral reef, and guided by an incorrect map; it took 8 days "among the reefs and islands of Waigiou"Wallace, 1869. Volume 2, p. 347. to return to a safe harbour. He sends a boat to rescue his men; it returns 10 days later without them, but he pays them again, and on the second attempt it returns with his two men, who had survived for a month "on the roots and tender flower-stalks of a species of Bromelia, on shell-fish, and on a few turtles' eggs."Wallace, 1869. Volume 2, p. 348.

;36 Waigiou

: He builds a palm-leaf hut, which leaks badly until they increase the slope of the roof. He shoots a red bird-of-paradise. He supposes the people to be of mixed race. He sails to Bessir where the chief lends him a tiny hut on stilts, entered by a ladder, and not tall enough to stand up in. He learns to live and work "in a semi-horizontal position";Wallace, 1869. Volume 2, p. 360. he is the first white man to come to the island. He trades goods for birds-of-paradise; the people do not shoot them with blunt arrows like Aru islanders, but set out fruit as bait on a forked stick, and catch the birds with a noose of cord that hangs from the stick down to the ground, pulling the cord when the bird arrives, sometimes after two or three days.

;37 Voyage from Waigiou to Ternate

: While sailing back to Ternate the boat is overtaken by a dozen waves which approached with a dull roaring like heavy surf, the sea being "perfectly smooth"Wallace, 1869. Volume 2, p. 371. before and after; he concludes these must have been earthquake waves as William Dampier

William Dampier (baptised 5 September 1651; died March 1715) was an English explorer, pirate, privateer, navigator, and naturalist who became the first Englishman to explore parts of what is today Australia, and the first person to circumnav ...

had described. Later he learnt that there had been an earthquake on Gilolo that day. On the journey they lose their anchor, and their mooring cable is snapped by a squall. New wooden anchors are ingeniously made. The men believe the boat is unlucky and ask for a ceremony before travelling further. They are caught by a storm and lose the small boat they are towing. Wallace notes that in 78 days there was "not one single day of fair wind." (sic)Wallace, 1869. Volume 2, p. 384.

;38 The Birds of Paradise

: Wallace, pointing out that he often journeyed expressly to obtain specimens, describes the birds-of-paradise in detail, and the effects of sexual selection

Sexual selection is a mode of natural selection in which members of one biological sex choose mates of the other sex to mate with (intersexual selection), and compete with members of the same sex for access to members of the opposite sex (in ...

by the females. He covers the great, king, red, magnificent, superb, golden or six-shafted, standard wing, twelve-wired, and epimaque or long-tailed birds-of-paradise, as well as three New Guinea birds which he considers almost as remarkable. He suggests they could live well if released in the Palm House at Kew Gardens. In all he knows of 18 species, of which 11 are from New Guinea and 8 are endemic to it and Salwatty, or 14 in the general New Guinea area (1 being from the Moluccas and 3 from Australia). His assistant Mr Allen runs into trouble as the people were suspicious of his motives. A year of five voyages had produced only 5 of the 14 species in the New Guinea area.

;39 Natural History of the Papuan Islands

: New Guinea, writes Wallace, is mostly unknown, with only the wildlife of the northwestern peninsula partially explored, but already 250 land birds are known, making the island of great interest. There are few mammals, mostly marsupials, including a kangaroo (first seen by Le Brun in 1714).

;40 The Races of Man in the Malay Archipelago

: Wallace ends the book by describing his views on the peoples of the archipelago. He finds the Malays, such as the Javanese, the most civilised, though he describes the Dyaks of Borneo and the Bataks of Sumatra, among others, as "the savage Malays".Wallace, 1869. Volume 2, p. 441. He quotes the traveller Nicolo Conti's 1430 account of them, with other early descriptions. He thinks the Papuan the opposite of the Malay, impulsive and demonstrative where the Malay is impassive and taciturn. He speculates about their origins, and in a note at the end, criticises English society.

;40 The Races of Man in the Malay Archipelago

: Wallace ends the book by describing his views on the peoples of the archipelago. He finds the Malays, such as the Javanese, the most civilised, though he describes the Dyaks of Borneo and the Bataks of Sumatra, among others, as "the savage Malays".Wallace, 1869. Volume 2, p. 441. He quotes the traveller Nicolo Conti's 1430 account of them, with other early descriptions. He thinks the Papuan the opposite of the Malay, impulsive and demonstrative where the Malay is impassive and taciturn. He speculates about their origins, and in a note at the end, criticises English society.

Appendix

; On Crania AndLanguage

Language is a structured system of communication. The structure of a language is its grammar and the free components are its vocabulary. Languages are the primary means by which humans communicate, and may be conveyed through a variety of ...

s

: Wallace mentions Huxley's theory, and Dr. Joseph Barnard Davis's book ''Thesaurus Craniorum'', which supposed that human races could be distinguished by the shape of the cranium, the dome of the skull, of which theory Wallace is sceptical. However he lists measurements he had taken of the crania of "Malays" and "Papuans", noting that within the Malay group there was enormous variation. He had few skulls in the Papuan group and there were no definite differences between the two groups.

: The language appendix lists 9 words (black, white, fire, water, large, small, nose, tongue, tooth) in 59 of the languages encountered in the archipelago, and 117 words in 33 of those languages, making it clear that many of the languages have many words in common.

Reception

Contemporary

''The Malay Archipelago'' was warmly received on publication, often in lengthy reviews that attempted to summarise the book, from the perspective that suited the reviewing periodical. It was reviewed in more than 40 periodicals: a selection of those reviews is summarised below.''Anthropological Review''