The Canadian Crown and First Nations, Inuit and Métis on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The association between the Canadian Crown and Indigenous peoples in

The association between

The association between

Since as early as 1710, Indigenous leaders have met to discuss treaty business with Royal Family members or viceroys in private audience and many continue to use their connection to the Crown to further their political aims. The above-mentioned pageants and celebrations have, for instance, been employed as a public platform on which to present complaints to the Monarch or other members of the Royal Family. It has been said that Aboriginal people in Canada appreciate their ability to do this witnessed by both national and international cameras.

Since as early as 1710, Indigenous leaders have met to discuss treaty business with Royal Family members or viceroys in private audience and many continue to use their connection to the Crown to further their political aims. The above-mentioned pageants and celebrations have, for instance, been employed as a public platform on which to present complaints to the Monarch or other members of the Royal Family. It has been said that Aboriginal people in Canada appreciate their ability to do this witnessed by both national and international cameras.

The

The  Both British and French monarchs viewed their lands in North America as being held by them in totality, including those occupied by First Nations. Typically, the treaties established delineations between territory reserved for colonial settlement and that distinctly for use by Indigenous peoples. The French kings, though they did not admit claims by Indigenous peoples to lands in New France, granted the natives reserves for their exclusive use; for instance, from 1716 onwards, land north and west of the manorials on the

Both British and French monarchs viewed their lands in North America as being held by them in totality, including those occupied by First Nations. Typically, the treaties established delineations between territory reserved for colonial settlement and that distinctly for use by Indigenous peoples. The French kings, though they did not admit claims by Indigenous peoples to lands in New France, granted the natives reserves for their exclusive use; for instance, from 1716 onwards, land north and west of the manorials on the

During the course of the American Revolution, First Nations assisted King George III's North American forces, who ultimately lost the conflict. As a result of the Treaty of Paris, signed in 1783 between King George and the American

During the course of the American Revolution, First Nations assisted King George III's North American forces, who ultimately lost the conflict. As a result of the Treaty of Paris, signed in 1783 between King George and the American  In 1860, during one of the first true

In 1860, during one of the first true  In 1870, Britain transferred what remained of Rupert's Land from the Hudson's Bay Company to Canada and colonial settlement expanded westward. More treaties were signed between 1871 and 1921, wherein the Crown brokered land exchanges that granted the Indigenous societies reserves and other compensation, such as livestock, ammunition, education, health care, and certain rights to hunt and fish. The treaties did not ensure peace: as evidenced by the

In 1870, Britain transferred what remained of Rupert's Land from the Hudson's Bay Company to Canada and colonial settlement expanded westward. More treaties were signed between 1871 and 1921, wherein the Crown brokered land exchanges that granted the Indigenous societies reserves and other compensation, such as livestock, ammunition, education, health care, and certain rights to hunt and fish. The treaties did not ensure peace: as evidenced by the

Following Canada's legislative independence from the United Kingdom (codified by the

Following Canada's legislative independence from the United Kingdom (codified by the

King George's daughter, Elizabeth, acceded to the throne in 1952.

King George's daughter, Elizabeth, acceded to the throne in 1952.

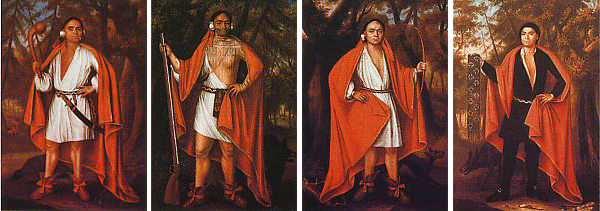

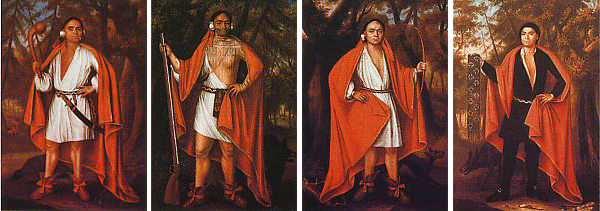

Portraits of the Four Mohawk Kings that had been commissioned while the leaders were in London had then hung at

Portraits of the Four Mohawk Kings that had been commissioned while the leaders were in London had then hung at

On 4 July 2010, Queen Elizabeth II presented to Her Majesty's Royal Chapel of the Mohawks and

On 4 July 2010, Queen Elizabeth II presented to Her Majesty's Royal Chapel of the Mohawks and  During the

During the

As the representatives in Canada and the provinces of the reigning monarch, both governors general and lieutenant governors have been closely associated with First Nations, Inuit, and Métis peoples. This dates back to the colonial era, when the sovereign did not travel from Europe to Canada and so dealt with Aboriginal societies through his or her

As the representatives in Canada and the provinces of the reigning monarch, both governors general and lieutenant governors have been closely associated with First Nations, Inuit, and Métis peoples. This dates back to the colonial era, when the sovereign did not travel from Europe to Canada and so dealt with Aboriginal societies through his or her  Five persons from First Nations have been appointed as the monarch's representative, all in the provincial spheres.

Five persons from First Nations have been appointed as the monarch's representative, all in the provincial spheres.

Comprehensive and Specific Claims in Canada – Indian and Northern Affairs Canada

Map of historical territory treaties with Aboriginal peoples in Canada

CBC Digital Archives – The Battle for Aboriginal Treaty Rights

Interviews with legal experts regarding Metis legal issues in the courts

{{DEFAULTSORT:The Canadian Crown And Aboriginal Peoples Monarchy in Canada Indigenous peoples in Canada First Nations history History of Indigenous peoples in Canada

Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by to ...

stretches back to the first decisions between North American Indigenous peoples and Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

an colonialists and, over centuries of interface, treaties

A treaty is a formal, legally binding written agreement between actors in international law. It is usually made by and between sovereign states, but can include international organizations, individuals, business entities, and other legal pers ...

were established concerning the monarch and Indigenous nations. First Nations

First Nations or first peoples may refer to:

* Indigenous peoples, for ethnic groups who are the earliest known inhabitants of an area.

Indigenous groups

*First Nations is commonly used to describe some Indigenous groups including:

**First Natio ...

, Inuit

Inuit (; iu, ᐃᓄᐃᑦ 'the people', singular: Inuk, , dual: Inuuk, ) are a group of culturally similar indigenous peoples inhabiting the Arctic and subarctic regions of Greenland, Labrador, Quebec, Nunavut, the Northwest Territorie ...

, and Métis

The Métis ( ; Canadian ) are Indigenous peoples of the Americas, Indigenous peoples who inhabit Canada's three Canadian Prairies, Prairie Provinces, as well as parts of British Columbia, the Northwest Territories, and the Northern United State ...

peoples in Canada have a unique relationship with the reigning monarch and, like the Māori

Māori or Maori can refer to:

Relating to the Māori people

* Māori people of New Zealand, or members of that group

* Māori language, the language of the Māori people of New Zealand

* Māori culture

* Cook Islanders, the Māori people of the Co ...

and the Treaty of Waitangi

The Treaty of Waitangi ( mi, Te Tiriti o Waitangi) is a document of central importance to the History of New Zealand, history, to the political constitution of the state, and to the national mythos of New Zealand. It has played a major role in ...

in New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 smaller islands. It is the sixth-largest island coun ...

, generally view the affiliation as being not between them and the ever-changing Cabinet

Cabinet or The Cabinet may refer to:

Furniture

* Cabinetry, a box-shaped piece of furniture with doors and/or drawers

* Display cabinet, a piece of furniture with one or more transparent glass sheets or transparent polycarbonate sheets

* Filin ...

, but instead with the continuous Crown of Canada, as embodied in the reigning sovereign. These agreements with the Crown are administered by Canadian Aboriginal law

Canadian Aboriginal law is the body of law of Canada that concerns a variety of issues related to Indigenous peoples in Canada. Canadian Aboriginal Law is different from Canadian Indigenous law: In Canada, Indigenous Law refers to the legal trad ...

and overseen by the Minister of Indigenous and Northern Affairs

Minister may refer to:

* Minister (Christianity), a Christian cleric

** Minister (Catholic Church)

* Minister (government), a member of government who heads a ministry (government department)

** Minister without portfolio, a member of government w ...

.

Relations

The association between

The association between Indigenous peoples in Canada

In Canada, Indigenous groups comprise the First Nations, Inuit and Métis. Although ''Indian'' is a term still commonly used in legal documents, the descriptors ''Indian'' and '' Eskimo'' have fallen into disuse in Canada, and most consider th ...

and the Canadian Crown is both statutory and traditional, the treaties being seen by the first peoples both as legal contracts and as perpetual and personal promises by successive reigning kings and queens to protect the welfare of Indigenous peoples, define their rights, and reconcile their sovereignty with that of the monarch in Canada. The agreements are formed with the Crown because the monarchy is thought to have inherent stability and continuity, as opposed to the transitory nature of populist whims that rule the political government, meaning the link between monarch and Indigenous peoples in Canada will theoretically last for "as long as the sun shines, grass grows and rivers flow."

The relationship has thus been described as mutual—"cooperation will be a cornerstone for partnership between Canada and First Nations, wherein ''Canada'' is the short-form reference to ''Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada''"—and "special," having a strong sense of "kinship" and possessing familial aspects. Constitutional scholars have observed that First Nations are "strongly supportive of the monarchy," even if not necessarily regarding the monarch as supreme. The nature of the legal interaction between Canadian sovereign and First Nations has similarly not always been supported.

Definition

While treaties were signed between European monarchs and First Nations in North America as far back as 1676, the only ones that survived theAmerican Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revoluti ...

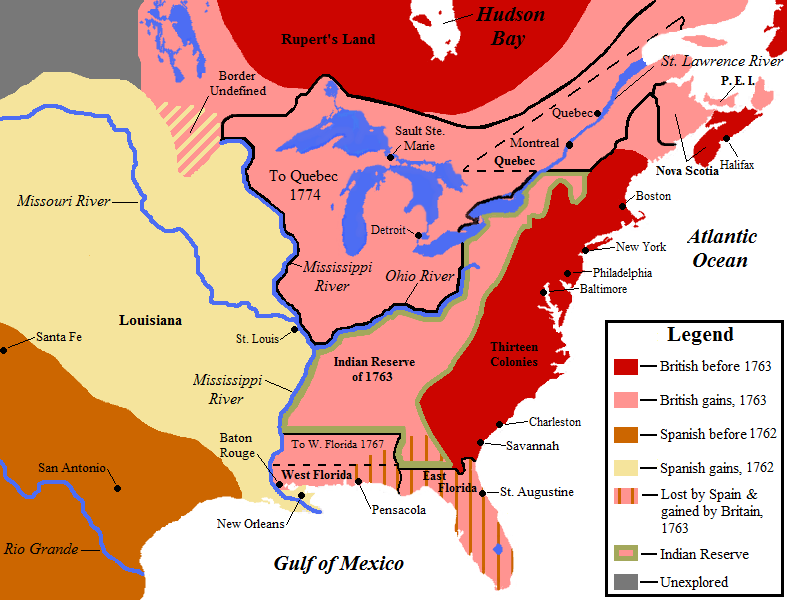

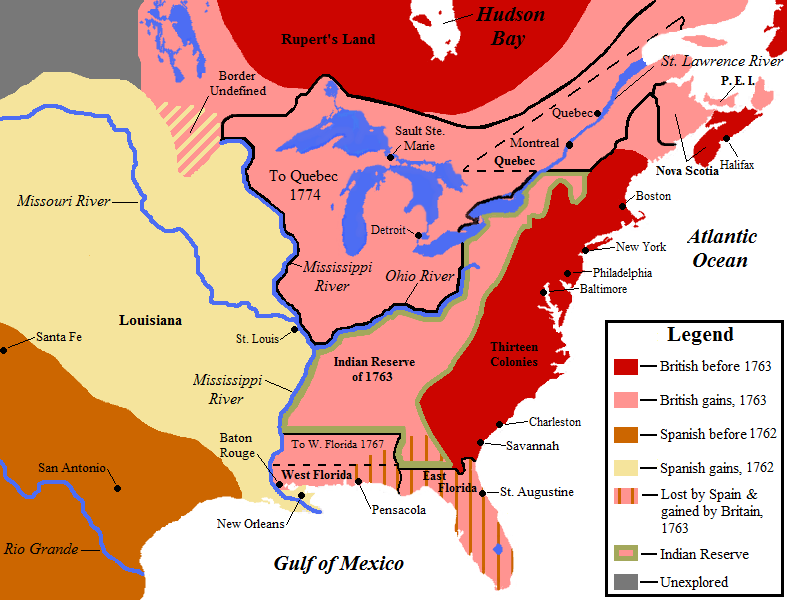

are those in Canada, which date to the beginning of the 18th century. Today, the main guide for relations between the monarchy and Canadian First Nations is King George III's Royal Proclamation of 1763

The Royal Proclamation of 1763 was issued by King George III on 7 October 1763. It followed the Treaty of Paris (1763), which formally ended the Seven Years' War and transferred French territory in North America to Great Britain. The Procla ...

; while not a treaty, it is regarded by First Nations as their Magna Carta

(Medieval Latin for "Great Charter of Freedoms"), commonly called (also ''Magna Charta''; "Great Charter"), is a royal charter of rights agreed to by King John of England at Runnymede, near Windsor, on 15 June 1215. First drafted by t ...

or "Indian Bill of Rights", binding on not only the British Crown

The Crown is the state in all its aspects within the jurisprudence of the Commonwealth realms and their subdivisions (such as the Crown Dependencies, overseas territories, provinces, or states). Legally ill-defined, the term has different ...

but the Canadian one as well, as the document remains a part of the Canadian constitution

The Constitution of Canada (french: Constitution du Canada) is the supreme law in Canada. It outlines Canada's system of government and the civil and human rights of those who are citizens of Canada and non-citizens in Canada. Its contents ar ...

. The proclamation set parts of the King's North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere and almost entirely within the Western Hemisphere. It is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South America and th ...

n realm aside for colonists and reserved others for the First Nations, thereby affirming native title to their lands and making clear that, though under the sovereignty

Sovereignty is the defining authority within individual consciousness, social construct, or territory. Sovereignty entails hierarchy within the state, as well as external autonomy for states. In any state, sovereignty is assigned to the perso ...

of the Crown, the Aboriginal bands were autonomous political units in a "nation-to-nation" association with non-native governments, with the monarch as the intermediary. This created not only a "constitutional and moral basis of alliance" between indigenous Canadians and the Canadian state as personified in the monarch, but also a fiduciary

A fiduciary is a person who holds a legal or ethical relationship of trust with one or more other parties (person or group of persons). Typically, a fiduciary prudently takes care of money or other assets for another person. One party, for exa ...

affiliation in which the Crown is constitutionally charged with providing certain guarantees to the First Nations, as affirmed in Sparrow v. The Queen, meaning that the "honour of the Crown" is at stake in dealings between it and First Nations leaders.

Given the "divided" nature of the Crown, the sovereign may be party to relations with Indigenous Canadians distinctly within a provincial jurisdiction. This has at times led to a lack of clarity regarding which of the monarch's jurisdictions should administer his or her duties towards Indigenous peoples.

Expressions

From time to time, the link between the Crown and Indigenous peoples will be symbolically expressed, throughpow-wow

A powwow (also pow wow or pow-wow) is a gathering with dances held by many Native American and First Nations communities. Powwows today allow Indigenous people to socialize, dance, sing, and honor their cultures. Powwows may be private or pu ...

s or other types of ceremony held to mark the anniversary of a particular treaty – sometimes with the participation of the monarch, another member of the Canadian Royal Family

The monarchy of Canada is Canada's form of government embodied by the Canadian sovereign and head of state. It is at the core of Canada's constitutional federal structure and Westminster-style parliamentary democracy. The monarchy is the founda ...

, or one of the Sovereign's representatives—or simply an occasion mounted to coincide with the presence of a member of the Royal Family on a royal tour, Indigenous peoples having always been a part of such tours of Canada. Gifts have been frequently exchanged and titles have been bestowed upon royal and viceregal figures since the early days of Indigenous contact with the Crown: The Ojibwa

The Ojibwe, Ojibwa, Chippewa, or Saulteaux are an Anishinaabe people in what is currently southern Canada, the northern Midwestern United States, and Northern Plains.

According to the U.S. census, in the United States Ojibwe people are one of ...

referred to King George III as the ''Great Father

Great Father and Great Mother (french: Bon Père, Grand-Mère, es, Gran Padre, Gran Madre) were titles used by European colonial powers in North America along with the United States during the 19th century to refer to the U.S. President, the Ki ...

'' and Queen Victoria was later dubbed as the ''Great White Mother''. Queen Elizabeth II was named ''Mother of all People'' by the Salish nation in 1959 and her son, Prince Charles, was in 1976 given the title of ''Attaniout Ikeneego'' by Inuit, meaning ''Son of the Big Boss''. Charles was further honoured in 1986, when Cree

The Cree ( cr, néhinaw, script=Latn, , etc.; french: link=no, Cri) are a North American Indigenous people. They live primarily in Canada, where they form one of the country's largest First Nations.

In Canada, over 350,000 people are Cree o ...

and Ojibwa students in Winnipeg

Winnipeg () is the capital and largest city of the province of Manitoba in Canada. It is centred on the confluence of the Red and Assiniboine rivers, near the longitudinal centre of North America. , Winnipeg had a city population of 749 ...

named Charles ''Leading Star'', and again in 2001, during the Prince's first visit to Saskatchewan

Saskatchewan ( ; ) is a Provinces and territories of Canada, province in Western Canada, western Canada, bordered on the west by Alberta, on the north by the Northwest Territories, on the east by Manitoba, to the northeast by Nunavut, and on t ...

, when he was named ''Pisimwa Kamiwohkitahpamikohk'', or ''The Sun Looks at Him in a Good Way'', by an elder in a ceremony at Wanuskewin Heritage Park

Wanuskewin Heritage Park is an archaeological site and non-profit cultural and historical centre of the First Nations just outside the city of Saskatoon, Saskatchewan. The faculty's name comes from the Cree language word ᐋᐧᓇᐢᑫᐃ ...

.

Since as early as 1710, Indigenous leaders have met to discuss treaty business with Royal Family members or viceroys in private audience and many continue to use their connection to the Crown to further their political aims. The above-mentioned pageants and celebrations have, for instance, been employed as a public platform on which to present complaints to the Monarch or other members of the Royal Family. It has been said that Aboriginal people in Canada appreciate their ability to do this witnessed by both national and international cameras.

Since as early as 1710, Indigenous leaders have met to discuss treaty business with Royal Family members or viceroys in private audience and many continue to use their connection to the Crown to further their political aims. The above-mentioned pageants and celebrations have, for instance, been employed as a public platform on which to present complaints to the Monarch or other members of the Royal Family. It has been said that Aboriginal people in Canada appreciate their ability to do this witnessed by both national and international cameras.

History

French and British crowns

Explorers commissioned byFrench

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

and English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ...

monarchs made contact with Indigenous peoples in North America in the late 15th and early 16th centuries. These interactions were generally peaceful—the agents of each sovereign seeking alliances with Indigenous leaders in wresting territories away from the other monarch—and the partnerships were typically secured through treaties, the first signed in 1676. However, the English also used friendly gestures as a vehicle for establishing Crown dealings with Indigenous peoples, while simultaneously expanding their colonial

Colonial or The Colonial may refer to:

* Colonial, of, relating to, or characteristic of a colony or colony (biology)

Architecture

* American colonial architecture

* French Colonial

* Spanish Colonial architecture

Automobiles

* Colonial (1920 au ...

domain: as fur trade

The fur trade is a worldwide industry dealing in the acquisition and sale of animal fur. Since the establishment of a world fur market in the early modern period, furs of boreal ecosystem, boreal, polar and cold temperate mammalian animals h ...

rs and outposts of the Hudson's Bay Company

The Hudson's Bay Company (HBC; french: Compagnie de la Baie d'Hudson) is a Canadian retail business group. A fur trading business for much of its existence, HBC now owns and operates retail stores in Canada. The company's namesake business di ...

(HBC), a crown corporation

A state-owned enterprise (SOE) is a government entity which is established or nationalised by the ''national government'' or ''provincial government'' by an executive order or an act of legislation in order to earn profit for the government ...

founded in 1670, spread westward across the continent, they introduced the concept of a just, paternal monarch to "guide and animate their exertions," to inspire loyalty, and promote peaceful relations. During the fur trade, before the British Crown was considering permanent settlement, marital alliances between traders and Indigenous women were a form of alliance between Indigenous peoples and the Crown. When a land settlement was being planned by the Crown, treaties become the more official and permanent form of relations. They also brought with them images of the English monarch, such as the medal that bore the effigy

An effigy is an often life-size sculptural representation of a specific person, or a prototypical figure. The term is mostly used for the makeshift dummies used for symbolic punishment in political protests and for the figures burned in certai ...

of King Charles II (founder of the HBC) and which was presented to native chiefs as a mark of distinction; these medallions were passed down through the generations of the chiefs' descendants and those who wore them received particular honour and recognition at HBC posts.

The

The Great Peace of Montreal

The Great Peace of Montreal (french: La Grande paix de Montréal) was a peace treaty between New France and 39 First Nations of North America that ended the Beaver Wars. It was signed on August 4, 1701, by Louis-Hector de Callière, governor of ...

was in 1701 signed by the Governor of New France The governor of New France was the viceroy of the King of France in North America. A French nobleman, he was appointed to govern the colonies of New France, which included Canada, Acadia and Louisiana. The residence of the Governor was at the C ...

, representing King Louis XIV

, house = Bourbon

, father = Louis XIII

, mother = Anne of Austria

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye, Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France

, death_date =

, death_place = Palace of Ver ...

, and the chiefs of 39 First Nations. Then, in 1710, Indigenous leaders were visiting personally with the British monarch; in that year, Queen Anne held an audience at St. James' Palace with three Mohawk—''Sa Ga Yeath Qua Pieth Tow'' of the Bear Clan (called Peter Brant

Peter Mark Brant Sr. (born March 1, 1947) is an American industrialist, as well as a magazine publisher, film producer, and art collector. He is married to model Stephanie Seymour.

Early life and education

Brant was raised in Jamaica Estate ...

, King of Maguas), ''Ho Nee Yeath Taw No Row'' of the Wolf Clan (called King John of Canojaharie), and ''Tee Yee Ho Ga Row'', or "Double Life", of the Wolf Clan (called King Hendrick Peters)—and one Mahican

The Mohican ( or , alternate spelling: Mahican) are an Eastern Algonquian Native American tribe that historically spoke an Algonquian language. As part of the Eastern Algonquian family of tribes, they are related to the neighboring Lenape, w ...

Chief—''Etow Oh Koam'' of the Turtle Clan (called Emperor of the Six Nations). The four, dubbed the ''Four Mohawk Kings'', were received in London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

as diplomats, being transported through the streets in royal carriages and visiting the Tower of London

The Tower of London, officially His Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress of the Tower of London, is a historic castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, which is sep ...

and St. Paul's Cathedral

St Paul's Cathedral is an Anglican cathedral in London and is the seat of the Bishop of London. The cathedral serves as the mother church of the Diocese of London. It is on Ludgate Hill at the highest point of the City of London and is a Gra ...

. But, their business was to request military aid for defence against the French, as well as missionaries for spiritual guidance. The latter request was passed by Anne to the Archbishop of Canterbury

The archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and a principal leader of the Church of England, the ceremonial head of the worldwide Anglican Communion and the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of Canterbury. The current archbishop is Just ...

, Thomas Tenison

Thomas Tenison (29 September 163614 December 1715) was an English church leader, Archbishop of Canterbury from 1694 until his death. During his primacy, he crowned two British monarchs.

Life

He was born at Cottenham, Cambridgeshire, the son a ...

, and a chapel was eventually built in 1711 at Fort Hunter, near present-day Johnstown, New York

Johnstown is a city in and the county seat of Fulton County in the U.S. state of New York. The city was named after its founder, Sir William Johnson, Superintendent of Indian Affairs in the Province of New York and a major general during the Sev ...

, along with the gift of a reed organ and a set of silver chalice

A chalice (from Latin 'mug', borrowed from Ancient Greek () 'cup') or goblet is a footed cup intended to hold a drink. In religious practice, a chalice is often used for drinking during a ceremony or may carry a certain symbolic meaning.

R ...

s in 1712.

Both British and French monarchs viewed their lands in North America as being held by them in totality, including those occupied by First Nations. Typically, the treaties established delineations between territory reserved for colonial settlement and that distinctly for use by Indigenous peoples. The French kings, though they did not admit claims by Indigenous peoples to lands in New France, granted the natives reserves for their exclusive use; for instance, from 1716 onwards, land north and west of the manorials on the

Both British and French monarchs viewed their lands in North America as being held by them in totality, including those occupied by First Nations. Typically, the treaties established delineations between territory reserved for colonial settlement and that distinctly for use by Indigenous peoples. The French kings, though they did not admit claims by Indigenous peoples to lands in New France, granted the natives reserves for their exclusive use; for instance, from 1716 onwards, land north and west of the manorials on the Saint Lawrence River

The St. Lawrence River (french: Fleuve Saint-Laurent, ) is a large river in the middle latitudes of North America. Its headwaters begin flowing from Lake Ontario in a (roughly) northeasterly direction, into the Gulf of St. Lawrence, connecting ...

were designated as the ''pays d'enhaut'' (upper country), or "Indian country", and were forbidden to settlement and clearing of land without the expressed authorisation of the King. The same was done by the kings of Great Britain; for example, the Friendship Treaty of 1725, which ended Dummer's War

Dummer's War (1722–1725) is also known as Father Rale's War, Lovewell's War, Greylock's War, the Three Years War, the Wabanaki-New England War, or the Fourth Anglo-Abenaki War. It was a series of battles between the New England Colonies and the ...

, established a relationship between King George III and the "Maeganumbe ... tribes Inhabiting His Majesty's Territories" in exchange for the guarantee that the indigenous people "not be molested in their persons ... by His Majesty's subjects." The British contended that the Treaty gave them title to Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia ( ; ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is one of the three Maritime provinces and one of the four Atlantic provinces. Nova Scotia is Latin for "New Scotland".

Most of the population are native Eng ...

and Acadia

Acadia (french: link=no, Acadie) was a colony of New France in northeastern North America which included parts of what are now the Maritime provinces, the Gaspé Peninsula and Maine to the Kennebec River. During much of the 17th and earl ...

, while Acadians

The Acadians (french: Acadiens , ) are an ethnic group descended from the French who settled in the New France colony of Acadia during the 17th and 18th centuries. Most Acadians live in the region of Acadia, as it is the region where the de ...

and the Mi'kmaq

The Mi'kmaq (also ''Mi'gmaq'', ''Lnu'', ''Miꞌkmaw'' or ''Miꞌgmaw''; ; ) are a First Nations people of the Northeastern Woodlands, indigenous to the areas of Canada's Atlantic Provinces and the Gaspé Peninsula of Quebec as well as the no ...

opposed further British settlement in the territory. The Mi'kmaq would later make peace with the British at the signing of the Halifax Treaties

The Peace and Friendship Treaties were a series of written documents (or, treaties) that Britain signed between 1725 and 1779 with various Mi’kmaq, Wolastoqiyik (Maliseet), Abenaki, Penobscot, and Passamaquoddy peoples (i.e., the Wabanaki Confe ...

.

History of colonization

Thecolonization

Colonization, or colonisation, constitutes large-scale population movements wherein migrants maintain strong links with their, or their ancestors', former country – by such links, gain advantage over other inhabitants of the territory. When ...

of land, people, culture and bodies was a result of settler colonial actions in the process of resource extraction and the settlement of the land. An example of this colonization is the imposing of European femininity onto Indigenous women. As Indigenous women adopted Christianity, mostly voluntarily, the social status of Indigenous women changed. Colonialism was an arm of the crown and its history still influences the Canadian government's policies regarding Indigenous peoples in the country. The ''Indian Act

The ''Indian Act'' (, long name ''An Act to amend and consolidate the laws respecting Indians'') is a Canadian act of Parliament that concerns registered Indians, their bands, and the system of Indian reserves. First passed in 1876 and still ...

''s exclusion of women from maintaining their own status for example, was a government-enforced policy that was amended in 1985 with Bill C31.

The sovereigns also sought alliances with the First Nations; the Iroquois

The Iroquois ( or ), officially the Haudenosaunee ( meaning "people of the longhouse"), are an Iroquoian Peoples, Iroquoian-speaking Confederation#Indigenous confederations in North America, confederacy of First Nations in Canada, First Natio ...

siding with Georges II and III and the Algonquin

Algonquin or Algonquian—and the variation Algonki(a)n—may refer to:

Languages and peoples

*Algonquian languages, a large subfamily of Native American languages in a wide swath of eastern North America from Canada to Virginia

**Algonquin la ...

with Louis XIV and XV. These arrangements left questions about the treatment of Aboriginals in the French territories once the latter were ceded in 1760 to George III. Article 40 of the Capitulation of Montreal

Montreal ( ; officially Montréal, ) is the second-most populous city in Canada and most populous city in the Canadian province of Quebec. Founded in 1642 as '' Ville-Marie'', or "City of Mary", it is named after Mount Royal, the triple- ...

, signed on 8 September 1760, inferred that First Nations peoples who had been subjects of King Louis XV

Louis XV (15 February 1710 – 10 May 1774), known as Louis the Beloved (french: le Bien-Aimé), was King of France from 1 September 1715 until his death in 1774. He succeeded his great-grandfather Louis XIV at the age of five. Until he reached ...

would then become the same of King George: "The Savages or Indian allies of his most Christian Majesty, shall be maintained in the Lands they inhabit; if they chose to remain there; they shall not be molested on any pretence whatsoever, for having carried arms, and served his most Christian Majesty; they shall have, as well as the French, liberty of religion, and shall keep their missionaries ..." Yet, two days before, the Algonquin, along with the Hurons of Lorette and eight other tribes, had already ratified a treaty at Fort Lévis

Fort Lévis, a fortification on the St. Lawrence River, was built in 1759 by the French. They had decided that Fort de La Présentation was insufficient to defend their St. Lawrence River colonies against the British. Named for François Gaston d ...

, making them allied with, and subjects of, the British king, who instructed General the Lord Amherst to treat the First Nations "upon the same principals of humanity and proper indulgence" as the French, and to "cultivate the best possible harmony and Friendship with the Chiefs of the Indian Tribes." The retention of civil code

A civil code is a codification of private law relating to property, family, and obligations.

A jurisdiction that has a civil code generally also has a code of civil procedure. In some jurisdictions with a civil code, a number of the core ar ...

in Quebec, though, caused the relations between the Crown and First Nations in that jurisdiction to be viewed as dissimilar to those that existed in the other Canadian colonies.

In 1763, George III issued a Royal Proclamation

A proclamation (Lat. ''proclamare'', to make public by announcement) is an official declaration issued by a person of authority to make certain announcements known. Proclamations are currently used within the governing framework of some nations ...

that acknowledged the First Nations as autonomous political units and affirmed their title to their lands; it became the main document governing the parameters of the relationship between the sovereign and Indigenous subjects in North America. The King thereafter ordered Sir William Johnson

Sir William Johnson, 1st Baronet of New York ( – 11 July 1774), was a British Army officer and colonial administrator from Ireland. As a young man, Johnson moved to the Province of New York to manage an estate purchased by his uncle, Royal Na ...

to make the proclamation known to Indigenous nations under the King's sovereignty and, by 1766, its provisions were already put into practical use. In the prelude to the American Revolution, native leader Joseph Brant

Thayendanegea or Joseph Brant (March 1743 – November 24, 1807) was a Mohawk military and political leader, based in present-day New York, who was closely associated with Great Britain during and after the American Revolution. Perhaps ...

took the King up on this offer of protection and voyaged to London between 1775 and 1776 to meet with George III in person and discuss the aggressive expansionist policies of the American colonists.

However, even as the Treaty of Niagara

The Treaty of Fort Niagara is one of several treaties signed between the British Crown and various indigenous peoples of North America.

Treaty of Niagara (1764)

The 1764 Treaty of Niagara was agreed to by Sir William Johnson for the Crown and ...

was being negotiated, the King's powers were being constrained by the development of constitutional monarchy

A constitutional monarchy, parliamentary monarchy, or democratic monarchy is a form of monarchy in which the monarch exercises their authority in accordance with a constitution and is not alone in decision making. Constitutional monarchies dif ...

and responsible government

Responsible government is a conception of a system of government that embodies the principle of parliamentary accountability, the foundation of the Westminster system of parliamentary democracy. Governments (the equivalent of the executive br ...

; what Walter Bagehot

Walter Bagehot ( ; 3 February 1826 – 24 March 1877) was an English journalist, businessman, and essayist, who wrote extensively about government, economics, literature and race. He is known for co-founding the '' National Review'' in 185 ...

called the "dignified crown" (the monarch him- or herself) and the "efficient crown" (the ministers of the Crown, usually drawn from and accountable to the elected chamber of parliament, using the sovereign's powers). This constitutional evolution continued through the reigns of George IV

George IV (George Augustus Frederick; 12 August 1762 – 26 June 1830) was King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and King of Hanover from the death of his father, King George III, on 29 January 1820, until his own death ten y ...

, William IV

William IV (William Henry; 21 August 1765 – 20 June 1837) was King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and King of Hanover from 26 June 1830 until his death in 1837. The third son of George III, William succeeded h ...

, and Victoria

Victoria most commonly refers to:

* Victoria (Australia), a state of the Commonwealth of Australia

* Victoria, British Columbia, provincial capital of British Columbia, Canada

* Victoria (mythology), Roman goddess of Victory

* Victoria, Seychelle ...

, but without consultation with, or obtaining the consent of, the First Nations bound in treaty with the Crown.

After the American Revolution

During the course of the American Revolution, First Nations assisted King George III's North American forces, who ultimately lost the conflict. As a result of the Treaty of Paris, signed in 1783 between King George and the American

During the course of the American Revolution, First Nations assisted King George III's North American forces, who ultimately lost the conflict. As a result of the Treaty of Paris, signed in 1783 between King George and the American Congress of the Confederation

The Congress of the Confederation, or the Confederation Congress, formally referred to as the United States in Congress Assembled, was the governing body of the United States of America during the Confederation period, March 1, 1781 – Mar ...

, British North America was divided into the sovereign United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

(US) and the still British Canadas, creating a new international border through some of those lands that had been set apart by the Crown for First Nations and completely immersing others within the new republic. As a result, some Indigenous nations felt betrayed by the King and their service to the monarch was detailed in oratories that called on the Crown to keep its promises, especially after nations that had allied themselves with the British sovereign were driven from their lands by Americans. New treaties were drafted and those Indigenous nations that had lost their territories in the United States, or simply wished to not live under the US government, were granted new land in Canada by the King.

The Mohawk Nation

The Mohawk people ( moh, Kanienʼkehá꞉ka) are the most easterly section of the Haudenosaunee, or Iroquois Confederacy. They are an Iroquoian-speaking Indigenous people of North America, with communities in southeastern Canada and northern N ...

was one such group, which abandoned its Mohawk Valley

The Mohawk Valley region of the U.S. state of New York is the area surrounding the Mohawk River, sandwiched between the Adirondack Mountains and Catskill Mountains, northwest of the Capital District. As of the 2010 United States Census, ...

territory, in present day New York State

New York, officially the State of New York, is a state in the Northeastern United States. It is often called New York State to distinguish it from its largest city, New York City. With a total area of , New York is the 27th-largest U.S. sta ...

, after Americans destroyed the natives' settlement, including the chapel donated by Queen Anne following the visit to London of the Four Mohawk Kings. As compensation, George III promised land in Canada to the Six Nations and, in 1784, some Mohawks settled in what is now the Bay of Quinte

The Bay of Quinte () is a long, narrow bay shaped like the letter "Z" on the northern shore of Lake Ontario in the province of Ontario, Canada. It is just west of the head of the Saint Lawrence River that drains the Great Lakes into the Gulf of ...

and the Grand River Valley, where two of North America's only three Chapels Royal

The Chapel Royal is an establishment in the Royal Household serving the spiritual needs of the sovereign and the British Royal Family. Historically it was a body of priests and singers that travelled with the monarch. The term is now also appl ...

— Christ Church Royal Chapel of the Mohawks and Her Majesty's Chapel of the Mohawks—were built to symbolise the connection between the Mohawk people and the Crown. Thereafter, the treaties with Indigenous peoples across southern Ontario were dubbed the Covenant Chain

The Covenant Chain was a series of alliances and treaties developed during the seventeenth century, primarily between the Iroquois Confederacy (Haudenosaunee) and the British colonies of North America, with other Native American tribes added. Firs ...

and ensured the preservation of First Nations' rights not provided elsewhere in the Americas. This treatment encouraged the loyalty of the Indigenouos peoples to the sovereign and, as allies of the King, they aided in defending his North American territories, especially during the War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States of America and its indigenous allies against the United Kingdom and its allies in British North America, with limited participation by Spain in Florida. It be ...

.

In 1860, during one of the first true

In 1860, during one of the first true royal tours of Canada

Royal tours of Canada by the Canadian royal family have been taking place since 1786, and continue into the 21st century, either as an official tour, a working tour, a vacation, or a period of military service by a member of the royal family. ...

, First Nations put on displays, expressed their loyalty to Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until her death in 1901. Her reign of 63 years and 216 days was longer than that of any previ ...

, and presented concerns about misconduct on the part of the Indian Department to the Queen's son, Prince Albert Edward, Prince of Wales, when he was in Canada West

The Province of Canada (or the United Province of Canada or the United Canadas) was a British colony in North America from 1841 to 1867. Its formation reflected recommendations made by John Lambton, 1st Earl of Durham, in the Report on the ...

. In that same year, Nahnebahwequay of the Ojibwa

The Ojibwe, Ojibwa, Chippewa, or Saulteaux are an Anishinaabe people in what is currently southern Canada, the northern Midwestern United States, and Northern Plains.

According to the U.S. census, in the United States Ojibwe people are one of ...

secured an audience with the Queen. When Governor General the Marquess of Lorne and his wife, Princess Louise Princess Louise may refer to:

;People:

* Princess Louise, Duchess of Argyll, 1848–1939, the sixth child and fourth daughter of Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom

* Princess Louise, Princess Royal and Duchess of Fife, 1867–1931, the ...

, a daughter of Queen Victoria, visited British Columbia

British Columbia (commonly abbreviated as BC) is the westernmost province of Canada, situated between the Pacific Ocean and the Rocky Mountains. It has a diverse geography, with rugged landscapes that include rocky coastlines, sandy beaches, for ...

in 1882, they were greeted upon arrival in New Westminster

New Westminster (colloquially known as New West) is a city in the Lower Mainland region of British Columbia, Canada, and a member municipality of the Metro Vancouver Regional District. It was founded by Major-General Richard Moody as the capi ...

by a flotilla of local Indigenous peoples in canoes who sang songs of welcome before the royal couple landed and proceeded through a ceremonial arch built by Indigenous people, which was hung with a banner reading "Clahowya Queenastenass", Chinook Jargon for "Welcome Queen's Child." The following day, the Marquess and Marchioness gave their presence to an event attended by thousands of First Nations people and at least 40 chiefs. One presented the Princess with baskets, a bracelet, and a ring of Aboriginal make and Louise said in response that, when she returned to the United Kingdom, she would show these items to the Queen.

In 1870, Britain transferred what remained of Rupert's Land from the Hudson's Bay Company to Canada and colonial settlement expanded westward. More treaties were signed between 1871 and 1921, wherein the Crown brokered land exchanges that granted the Indigenous societies reserves and other compensation, such as livestock, ammunition, education, health care, and certain rights to hunt and fish. The treaties did not ensure peace: as evidenced by the

In 1870, Britain transferred what remained of Rupert's Land from the Hudson's Bay Company to Canada and colonial settlement expanded westward. More treaties were signed between 1871 and 1921, wherein the Crown brokered land exchanges that granted the Indigenous societies reserves and other compensation, such as livestock, ammunition, education, health care, and certain rights to hunt and fish. The treaties did not ensure peace: as evidenced by the North-West Rebellion

The North-West Rebellion (french: Rébellion du Nord-Ouest), also known as the North-West Resistance, was a Resistance movement, resistance by the Métis people (Canada), Métis people under Louis Riel and an associated uprising by First Natio ...

of 1885, sparked by Métis people's concerns over their survival and discontent on the part of Cree

The Cree ( cr, néhinaw, script=Latn, , etc.; french: link=no, Cri) are a North American Indigenous people. They live primarily in Canada, where they form one of the country's largest First Nations.

In Canada, over 350,000 people are Cree o ...

people over unfairness in the treaties signed with Queen Victoria.

Independent Canada

Following Canada's legislative independence from the United Kingdom (codified by the

Following Canada's legislative independence from the United Kingdom (codified by the Statute of Westminster, 1931

The Statute of Westminster 1931 is an act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom that sets the basis for the relationship between the Commonwealth realms and the Crown.

Passed on 11 December 1931, the statute increased the sovereignty of the ...

) relations—both statutory and ceremonial—between sovereign and First Nations continued unaffected as the British Crown in Canada morphed into a distinctly Canadian monarchy. Indeed, during the 1939 tour of Canada by King George VI

George VI (Albert Frederick Arthur George; 14 December 1895 – 6 February 1952) was King of the United Kingdom and the Dominions of the British Commonwealth from 11 December 1936 until his death in 1952. He was also the last Emperor of I ...

and Queen Elizabeth

Queen Elizabeth, Queen Elisabeth or Elizabeth the Queen may refer to:

Queens regnant

* Elizabeth I (1533–1603; ), Queen of England and Ireland

* Elizabeth II (1926–2022; ), Queen of the United Kingdom and other Commonwealth realms

* Queen ...

—an event intended to express the new independence of Canada and its monarchy—First Nations journeyed to city centres like Regina, Saskatchewan

Regina () is the capital city of the Canadian province of Saskatchewan. The city is the second-largest in the province, after Saskatoon, and is a commercial centre for southern Saskatchewan. As of the 2021 census, Regina had a city populatio ...

, and Calgary

Calgary ( ) is the largest city in the western Canadian province of Alberta and the largest metro area of the three Prairie Provinces. As of 2021, the city proper had a population of 1,306,784 and a metropolitan population of 1,481,806, maki ...

, Alberta

Alberta ( ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is part of Western Canada and is one of the three prairie provinces. Alberta is bordered by British Columbia to the west, Saskatchewan to the east, the Northwest T ...

, to meet with the King and present gifts and other displays of loyalty. In the course of the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposi ...

that followed soon after George's tour, more than 3,000 First Nations and Métis Canadians fought for the Canadian Crown and country, some receiving personal recognition from the King, such as Tommy Prince

Thomas George Prince MM SSM (October 25, 1915 – November 25, 1977) was an Indigenous Canadian war hero and the most decorated soldier in the First Special Service Force or Devil's Brigade during World War II. He was Canada's most decorated ...

, who was presented with the Military Medal and, on behalf of the President of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the Federal government of the United States#Executive branch, executive branch of the Federal gove ...

, the Silver Star

The Silver Star Medal (SSM) is the United States Armed Forces' third-highest military decoration for valor in combat. The Silver Star Medal is awarded primarily to members of the United States Armed Forces for gallantry in action against an e ...

by the King at Buckingham Palace.

King George's daughter, Elizabeth, acceded to the throne in 1952.

King George's daughter, Elizabeth, acceded to the throne in 1952. Squamish Nation

The Squamish Nation, Sḵwx̱wú7mesh Úxwumixw () in Sḵwx̱wú7mesh Sníchim (Squamish language), is an Indian Act government originally imposed on the Squamish (''Sḵwx̱wú7mesh'') by the Federal Government of Canada in the late 19th c ...

Chief Joe Mathias was amongst the Canadian dignitaries who were invited to attend her coronation in London the following year. In 1959, the Queen toured Canada and, in Labrador

, nickname = "The Big Land"

, etymology =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Canada

, subdivision_type1 = Province

, subdivision_name1 ...

, she was greeted by the Chief of the Montagnais and given a pair of beaded moose-hide jackets; at Gaspé, Quebec

Gaspé is a city at the tip of the Gaspé Peninsula in the Gaspésie–Îles-de-la-Madeleine region of eastern Quebec in Canada. Gaspé is located about northeast of Quebec City, and east of Rimouski. As of the 2021 Canadian Census, the city ha ...

, she and her husband, the Duke of Edinburgh, were presented with deerskin coats by two local Indigenous people; and, in Ottawa, a man from the Kahnawake Mohawk Territory passed to officials a 200-year-old wampum

Wampum is a traditional shell bead of the Eastern Woodlands tribes of Native Americans. It includes white shell beads hand-fashioned from the North Atlantic channeled whelk shell and white and purple beads made from the quahog or Western Nor ...

as a gift for Elizabeth. It was during that journey that the Queen became the first member of the Royal Family to meet with Inuit representatives, doing so in Stratford, Ontario

Stratford is a city on the Avon River within Perth County in southwestern Ontario, Canada, with a 2016 population of 31,465 in a land area of . Stratford is the seat of Perth County, which was settled by English, Irish, Scottish and German ...

, and the royal train stopped in Brantford, Ontario

Brantford ( 2021 population: 104,688) is a city in Ontario, Canada, founded on the Grand River in Southwestern Ontario. It is surrounded by Brant County, but is politically separate with a municipal government of its own that is fully independe ...

, so that the Queen could sign the Six Nations Queen Anne Bible in the presence of Six Nations leaders. Across the prairies, First Nations were present on the welcoming platforms in numerous cities and towns, and at the Calgary Stampede

The Calgary Stampede is an annual rodeo, exhibition, and festival held every July in Calgary, Alberta, Canada. The ten-day event, which bills itself as "The Greatest Outdoor Show on Earth", attracts over one million visitors per year and featu ...

, more than 300 Blackfoot

The Blackfoot Confederacy, ''Niitsitapi'' or ''Siksikaitsitapi'' (ᖹᐟᒧᐧᒣᑯ, meaning "the people" or "Blackfoot language, Blackfoot-speaking real people"), is a historic collective name for linguistically related groups that make up t ...

, Tsuu T'ina, and Nakoda performed a war dance

A war dance is a dance involving mock combat, usually in reference to tribal warrior societies where such dances were performed as a ritual connected with endemic warfare.

Martial arts in various cultures can be performed in dance-like setti ...

and erected approximately 30 teepee

A tipi , often called a lodge in English, is a conical tent, historically made of animal hides or pelts, and in more recent generations of canvas, stretched on a framework of wooden poles. The word is Siouan, and in use in Dakhótiyapi, Lakȟó ...

s, amongst which the Queen and the Duke of Edinburgh walked, meeting with various chiefs. In Nanaimo

Nanaimo ( ) is a city on the east coast of Vancouver Island, in British Columbia, Canada. As of the 2021 census, it had a population of 99,863, and it is known as "The Harbour City." The city was previously known as the "Hub City," which was ...

, British Columbia

British Columbia (commonly abbreviated as BC) is the westernmost province of Canada, situated between the Pacific Ocean and the Rocky Mountains. It has a diverse geography, with rugged landscapes that include rocky coastlines, sandy beaches, for ...

, a longer meeting took place between Elizabeth and the Salish, wherein the latter conferred on the former the title of ''Mother of all People'' and, following a dance of welcome, the Queen and her consort spent 45 minutes (20 more than allotted) touring a replica First Nations village and chatting with some 200 people.

In 1970, Elizabeth II's presence at The Pas, Manitoba, provided an opportunity for the Opaskwayak Cree Nation to publicly express their perceptions of injustice meted out by the government. Then, during a royal tour by the Queen in 1973, Harold Cardinal

Harold Cardinal (January 27, 1945 – June 3, 2005) was a Cree writer, political leader, teacher, negotiator, and lawyer. Throughout his career he advocated, on behalf of all First Nation peoples, for the right to be "the red tile in the Can ...

delivered a politically charged speech to the monarch and the Queen responded, stating that "her government recognized the importance of full compliance with the spirit and intent of treaties"; the whole exchange had been pre-arranged between the two. The British High Commissioner to Canada at the time stated a Canadian official, likely Jean Chrétien

Joseph Jacques Jean Chrétien (; born January 11, 1934) is a Canadian lawyer and politician who served as the 20th prime minister of Canada from 1993 to 2003.

Born and raised in Shawinigan, Shawinigan Falls, Quebec, Chrétien is a law gradua ...

, had said to him, "the monarchy and the fact that, on occasions, the Queen can talk directly to the native peoples, has helped to prevent in Canada anything like a direct confrontation similar to Wounded Knee." Still, during the same tour, Indigenous people were not always granted the personal time with the Queen that they desired; the meetings with First Nations and Inuit tended to be purely ceremonial affairs wherein treaty issues were not officially discussed. For instance, when Queen Elizabeth arrived in Stoney Creek, Ontario

Stoney Creek is a community in the city of Hamilton in the Canadian province of Ontario. It was officially a city from 1984 to 2001, when it was amalgamated with the rest of the cities of the Regional Municipality of Hamilton–Wentworth.

The ...

, five chiefs in full feathered headdress and a cortege of 20 braves and their consorts came to present to her a letter outlining their grievances, but were prevented by officials from meeting with the sovereign. In 1976, the Queen did receive First Nations delegations at Buckingham Palace, such as the group of Alberta Aboriginal Chiefs who, along with Lieutenant Governor of Alberta

The lieutenant governor of Alberta () is the viceregal representative in Alberta of the . The lieutenant governor is appointed in the same manner as the other provincial viceroys in Canada and is similarly tasked with carrying out most of the m ...

and Cree chief Ralph Steinhauer

Ralph Garvin Steinhauer, (June 8, 1905 – September 19, 1987) was the tenth lieutenant governor of Alberta, and the first Aboriginal person to hold that post.

Personal life

Ralph Garvin Apow (later Steinhauer) was born on June 8, 1905, at Mo ...

, held audience with the monarch there.

After constitutional patriation

In the prelude to thepatriation

Patriation is the political process that led to full Canadian sovereignty, culminating with the Constitution Act, 1982. The process was necessary because under the Statute of Westminster 1931, with Canada's agreement at the time, the British parl ...

of the Canadian constitution

The Constitution of Canada (french: Constitution du Canada) is the supreme law in Canada. It outlines Canada's system of government and the civil and human rights of those who are citizens of Canada and non-citizens in Canada. Its contents ar ...

in 1982, some First Nations leaders campaigned for and some against the proposed move, many asserting that the federal ministers of the Crown had no right to advise the Queen that she sever, without consent from the First Nations, the treaty rights she and her ancestors had long granted to Indigenous Canadians. Worrying to them was the fact that their relationship with the monarch had, over the preceding century, come to be interpreted by Indian Affairs officials as one of subordination to the government—a misreading on the part of non-Aboriginals of the terms ''Great White Mother'' and her ''Indian Children''. Indeed, First Nations representatives were locked out of constitutional conferences in the late 1970s, leading the National Indian Brotherhood

The Assembly of First Nations (AFN) is an assembly of Canadian First Nations (Indian bands) represented by their chiefs. Established in 1982 and modelled on the United Nations General Assembly, it emerged from the National Indian Brotherhood, wh ...

(NIB) to make plans to petition the Queen directly. The Liberal Cabinet at the time, not wishing to be embarrassed by having the monarch intervene, extended to the NIB an invitation to talks at the ministerial level, though not the first ministers' meetings. But the invitation came just before the election in May 1979, which put the Progressive Conservative Party into Cabinet and the new ministers of the Crown decided to advise the Queen not to meet with the NIB delegation, while telling the NIB that the Queen had no power.

After another election on 18 February 1980, the Liberal Party

The Liberal Party is any of many political parties around the world. The meaning of ''liberal'' varies around the world, ranging from liberal conservatism on the right to social liberalism on the left.

__TOC__ Active liberal parties

This is a li ...

won the plurality of seats in the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. T ...

, leading Governor General Edward Schreyer

Edward Richard Schreyer (born December 21, 1935) is a Canadian politician, diplomat, and statesman who served as Governor General of Canada, the 22nd since Canadian Confederation.

Schreyer was born and educated in Manitoba, and was first electe ...

to appoint Pierre Trudeau

Joseph Philippe Pierre Yves Elliott Trudeau ( , ; October 18, 1919 – September 28, 2000), also referred to by his initials PET, was a Canadian lawyer and politician who served as the 15th prime minister of Canada from 1968 to 1979 and ...

as prime minister, who advised the viceroy to appoint other Liberal Members of Parliament to Cabinet. On 2 October that year, Trudeau announced on national television his intention to proceed with unilateral patriation in what he termed the "people's package". However, the Union of British Columbia Indian Chiefs

The Union of British Columbia Indian Chiefs (UBCIC) is a First Nations political organization founded in 1969 in response to Jean Chrétien's White Paper proposal to assimilate Status Indians and disband the Department of Indian Affairs.

Sin ...

, led by President George Manuel

George Manuel, OC (February 21, 1921 – November 15, 1989, Secwépemc) was an Aboriginal leader in Canada. Born and raised in British Columbia, he became politically active there and in Alberta. In 1970 he was elected and served until 1976 as ...

, opposed the action due to the continued exclusion of Indigenous voices from consultations and forums of debate. To protest the lack of consultation and their concerns that the act would strip them of their rights and titles, the UBCIC organised the Indian Constitutional Express by chartering two trains that left Vancouver on 24 November 1980 for Ottawa. Upon arrival on 5 December, the "Constitution Express" was carrying approximately 1,000 people of all ages. Although Trudeau announced that he would extend the timetable for the Special Joint Committee on the Constitution to hear from Indigenous representatives, the leaders of the protest presented a petition and a bill of particulars directly to Schreyer. Unsatisfied with the response from the federal government, 41 people immediately continued on to the United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be a centre for harmoni ...

headquarters in New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

to gain international attention. Finally, they embarked for the Netherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of the Netherlands

, established_title = Before independence

, established_date = Spanish Netherl ...

, Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwee ...

, France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

, and Belgium

Belgium, ; french: Belgique ; german: Belgien officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. The country is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeast, France to ...

in 1981 to present the concerns and experiences of indigenous Canadians to an international audience. In November, they arrived in London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

, England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe ...

, and petitioned the British parliament

The Parliament of the United Kingdom is the supreme legislative body of the United Kingdom, the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories. It meets at the Palace of Westminster, London. It alone possesses legislative suprem ...

, eventually gaining audience with the House of Lords

The House of Lords, also known as the House of Peers, is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Membership is by appointment, heredity or official function. Like the House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminst ...

.

While no meeting with the Queen took place, the position of Indigenous Canadians was confirmed by Master of the Rolls

The Keeper or Master of the Rolls and Records of the Chancery of England, known as the Master of the Rolls, is the President of the Civil Division of the Court of Appeal of England and Wales and Head of Civil Justice. As a judge, the Master of ...

the Lord Denning, who ruled that the relationship was indeed one between sovereign and First Nations directly, clarifying further that, since the Statute of Westminster was passed in 1931, the Canadian Crown

The monarchy of Canada is Canada's form of government embodied by the Canadian sovereign and head of state. It is at the core of Canada's constitutional federal structure and Westminster-style parliamentary democracy. The monarchy is the founda ...

had come to be distinct from the British Crown

The Crown is the state in all its aspects within the jurisprudence of the Commonwealth realms and their subdivisions (such as the Crown Dependencies, overseas territories, provinces, or states). Legally ill-defined, the term has different ...

, though the two were still held by the same monarch, leaving the treaties sound. Upon their return to Canada, the NIB was granted access to first ministers' meetings and the ability to address the premiers. After extensive negotiations with Indigenous leaders, the Trudeau agreed to their demands in late January 1982 and therefore introduced Section 35 of the Constitution Act, which officially reaffirmed Aboriginal rights.

Some 15 years later, the Governor General-in-Council, per the Inquiry Act, and on the advice of Prime Minister Brian Mulroney

Martin Brian Mulroney ( ; born March 20, 1939) is a Canadian lawyer, businessman, and politician who served as the 18th prime minister of Canada from 1984 to 1993.

Born in the eastern Quebec city of Baie-Comeau, Mulroney studied political s ...

, established the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples

The Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples (RCAP) was a Canadian royal commission established in 1991 with the aim of investigating the relationship between Indigenous peoples in Canada, the Government of Canada, and Canadian society as a whole. ...

to address a number of concerns surrounding the relationship between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples in Canada. After 178 days of public hearings, visits by 96 communities, and numerous reviews and reports, the central conclusion reached was that "the main policy direction, pursued for more than 150 years, first by colonial then by Canadian governments, has been wrong," focusing on the previous attempts at cultural assimilation

Cultural assimilation is the process in which a minority group or culture comes to resemble a society's majority group or assume the values, behaviors, and beliefs of another group whether fully or partially.

The different types of cultural ass ...

. It was recommended that the nation-to-nation relationship of mutual respect be re-established between the Crown and First Nations, specifically calling for the monarch to "announce the establishment of a new era of respect for the treaties" and renew the treaty process through the issuance of a new royal proclamation as supplement to the Royal Proclamation of 1763. It was argued by Tony Hall, a professor of Native American studies at the University of Lethbridge

, mottoeng = '' Let there be light''

, type = Public

, established =

, academic_affiliations = Universities Canada

, endowment = $73 million (2019)

, chancellor = Charles Weas ...

, that the friendly relations between monarch and indigenous Canadians must continue as a means to exercise Canadian sovereignty

The sovereignty of Canada is a major cultural matter in Canada. Several issues currently define Canadian sovereignty: the Canadian monarchy, telecommunication, the autonomy of Canadian provinces, provinces, and Canada's Arctic border.

Canada is a ...

.

In 1994, while the Queen and her then-prime minister, Jean Chrétien

Joseph Jacques Jean Chrétien (; born January 11, 1934) is a Canadian lawyer and politician who served as the 20th prime minister of Canada from 1993 to 2003.

Born and raised in Shawinigan, Shawinigan Falls, Quebec, Chrétien is a law gradua ...

, were in Yellowknife

Yellowknife (; Dogrib: ) is the capital, largest community, and only city in the Northwest Territories, Canada. It is on the northern shore of Great Slave Lake, about south of the Arctic Circle, on the west side of Yellowknife Bay near the ...

for Her Majesty to open the Northwest Territories Legislative Building, Bill Erasmus, the leader of the Dene

The Dene people () are an indigenous group of First Nations who inhabit the northern boreal and Arctic regions of Canada. The Dene speak Northern Athabaskan languages. ''Dene'' is the common Athabaskan word for "people". The term "Dene" ha ...

community of the Northwest Territories

The Northwest Territories (abbreviated ''NT'' or ''NWT''; french: Territoires du Nord-Ouest, formerly ''North-Western Territory'' and ''North-West Territories'' and namely shortened as ''Northwest Territory'') is a federal territory of Canada. ...

, used the opportunity to, in front of the nation's and world's cameras, present the monarch with a list of grievances over stalled land claim negotiations. Erasmus stated the Dene's relationship with the Crown was “tarnished and sullied” because the treaties had not been honoured. Though Chrétien gave a political reply, the Queen provided a more diplomatic response, acknowledging the controversies and stating, "you have your differences; linguistic, cultural, or geographical. May these differences long remain. But, may they never be cause for intolerance or give rise to acrimony."

Similarly, the Queen and Chrétien visited in 1997 the community of Sheshatshiu

Sheshatshiu () is an Innu federal reserve and designated place in the Canadian province of Newfoundland and Labrador. The reserve is approximately north of Happy Valley-Goose Bay. Some references may spell the community's name as Sheshatshit, th ...

in Newfoundland and Labrador

Newfoundland and Labrador (; french: Terre-Neuve-et-Labrador; frequently abbreviated as NL) is the easternmost province of Canada, in the country's Atlantic region. The province comprises the island of Newfoundland and the continental region ...

, where the Innu

The Innu / Ilnu ("man", "person") or Innut / Innuat / Ilnuatsh ("people"), formerly called Montagnais from the French colonial period ( French for "mountain people", English pronunciation: ), are the Indigenous inhabitants of territory in the ...

people of Quebec and Labrador

, nickname = "The Big Land"

, etymology =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Canada

, subdivision_type1 = Province

, subdivision_name1 ...

presented a letter of grievance over stagnant land claim talks. On both occasions, instead of giving the documents to the Prime Minister, as he was not party to the treaty agreements, they were handed by the chiefs to the Queen, who, after speaking with the First Nations representatives, then passed the list and letter to Chrétien for him and the other ministers of the Crown to address and advise

ADVISE (Analysis, Dissemination, Visualization, Insight, and Semantic Enhancement) is a research and development program within the United States Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Threat and Vulnerability Testing and Assessment (TVTA) portfoli ...

the Queen or her viceroy

A viceroy () is an official who reigns over a polity in the name of and as the representative of the monarch of the territory. The term derives from the Latin prefix ''vice-'', meaning "in the place of" and the French word ''roy'', meaning " ...

on how to proceed.

21st century

During the visit of Queen Elizabeth II to Alberta and Saskatchewan in 2005, First Nations stated that they felt relegated to a merely ceremonial role, having been denied by federal and provincial ministers any access to the Queen in private audience. First Nations leaders have also raised concerns about what they see as a crumbling relationship between their people and the Crown, fueled by the failure of the federal and provincial cabinets to resolve land claim disputes, as well as a perceived intervention of the Crown into Indigenous affairs. Formal relations have also not yet been founded between the monarchy and a number of First Nations around Canada; such as those inBritish Columbia

British Columbia (commonly abbreviated as BC) is the westernmost province of Canada, situated between the Pacific Ocean and the Rocky Mountains. It has a diverse geography, with rugged landscapes that include rocky coastlines, sandy beaches, for ...

who are still engaged in the process of treaty making.

Portraits of the Four Mohawk Kings that had been commissioned while the leaders were in London had then hung at

Portraits of the Four Mohawk Kings that had been commissioned while the leaders were in London had then hung at Kensington Palace

Kensington Palace is a royal residence set in Kensington Gardens, in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea in London, England. It has been a residence of the British royal family since the 17th century, and is currently the official L ...

for nearly 270 years, until Queen Elizabeth II in 1977 donated them to the Canadian Collection at the National Archives of Canada

Library and Archives Canada (LAC; french: Bibliothèque et Archives Canada) is the federal institution, tasked with acquiring, preserving, and providing accessibility to the documentary heritage of Canada. The national archive and library is t ...

, unveiling them personally in Ottawa. That same year, the Queen's son, Prince Charles, Prince of Wales

Charles III (Charles Philip Arthur George; born 14 November 1948) is King of the United Kingdom and the 14 other Commonwealth realms. He was the longest-serving heir apparent and Prince of Wales and, at age 73, became the oldest person to ...

, visited Alberta to attend celebrations marking the 100th anniversary of the signing of Treaty 7

Treaty 7 is an agreement between the Crown and several, mainly Blackfoot, First Nation band governments in what is today the southern portion of Alberta. The idea of developing treaties for Blackfoot lands was brought to Blackfoot chief Cro ...

, when he was made a Kainai

The Kainai Nation (or , or Blood Tribe) ( bla, Káínaa) is a First Nations band government in southern Alberta, Canada, with a population of 12,800 members in 2015, up from 11,791 in December 2013.

translates directly to 'many chief' (from ...

chieftain, and, as a bicentennial gift in 1984, Elizabeth II gave to the Christ Church Royal Chapel

Christ Church, His Majesty's Chapel Royal of the Mohawk is located on the Tyendinaga Mohawk Territory near Deseronto, Ontario, Canada. It is owned by the Mohawks of the Bay of Quinte First Nation and is associated with the Anglican Parish of Tye ...