Textile manufacture during the Industrial Revolution on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Textile manufacture during the British Industrial Revolution was centred in south

Textile manufacture during the British Industrial Revolution was centred in south

The commencement of the Industrial Revolution is closely linked to a small number of innovations, made in the second half of the 18th century:The Industrial Revolution – Innovations

The commencement of the Industrial Revolution is closely linked to a small number of innovations, made in the second half of the 18th century:The Industrial Revolution – Innovations

/ref> * John Kay's 1733

In 1738, Lewis Paul (one of the community of

In 1738, Lewis Paul (one of the community of

Press the 'Ingenious' button and use search key '10302171' for the patent Arkwright used waterwheels to power the textile machinery. His initial attempts at driving the frame had used horse power, but a mill needed far more power. Using a waterwheel demanded a location with a ready supply of water, hence the mill at Cromford. This mill is preserved as part of the Derwent Valley Mills Arkwright generated jobs and constructed accommodation for his workers which he moved into the area. This led to a sizeable industrial community. Arkwright protected his investment from industrial rivals and potentially disruptive workers. This model worked and he expanded his operations to other parts of the country.

In 1830, using an 1822 patent, Richard Roberts manufactured the first loom with a cast-iron frame, the Roberts Loom. In 1842 James Bullough and William Kenworthy, made the

In 1830, using an 1822 patent, Richard Roberts manufactured the first loom with a cast-iron frame, the Roberts Loom. In 1842 James Bullough and William Kenworthy, made the

Also in 1830, Richard Roberts patented the first self-acting mule. The

Also in 1830, Richard Roberts patented the first self-acting mule. The

Textile manufacture during the British Industrial Revolution was centred in south

Textile manufacture during the British Industrial Revolution was centred in south Lancashire

Lancashire ( , ; abbreviated Lancs) is the name of a historic county, ceremonial county, and non-metropolitan county in North West England. The boundaries of these three areas differ significantly.

The non-metropolitan county of Lancas ...

and the towns on both sides of the Pennines in the United Kingdom. The main drivers of the Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution was the transition to new manufacturing processes in Great Britain, continental Europe, and the United States, that occurred during the period from around 1760 to about 1820–1840. This transition included going f ...

were textile manufacturing

Textile Manufacturing or Textile Engineering is a major industry. It is largely based on the conversion of fibre into yarn, then yarn into fabric. These are then dyed or printed, fabricated into cloth which is then converted into useful goods ...

, iron founding

A foundry is a factory that produces metal castings. Metals are cast into shapes by melting them into a liquid, pouring the metal into a mold, and removing the mold material after the metal has solidified as it cools. The most common metals pr ...

, steam power, oil drilling, the discovery of electricity and its many industrial applications, the telegraph and many others. Railroads, steam boats, the telegraph and other innovations massively increased worker productivity and raised standards of living by greatly reducing time spent during travel, transportation and communications..

Before the 18th century, the manufacture of cloth was performed by individual workers, in the premises in which they lived and goods were transported around the country by packhorse

A packhorse, pack horse, or sumpter refers to a horse, mule, donkey, or pony used to carry goods on its back, usually in sidebags or panniers. Typically packhorses are used to cross difficult terrain, where the absence of roads prevents the use of ...

s or by river navigations and contour-following canal

Canals or artificial waterways are waterways or engineered channels built for drainage management (e.g. flood control and irrigation) or for conveyancing water transport vehicles (e.g. water taxi). They carry free, calm surface f ...

s that had been constructed in the early 18th century. In the mid-18th century, artisan

An artisan (from french: artisan, it, artigiano) is a skilled craft worker who makes or creates material objects partly or entirely by hand. These objects may be functional or strictly decorative, for example furniture, decorative art ...

s were inventing ways to become more productive. Silk

Silk is a natural protein fiber, some forms of which can be woven into textiles. The protein fiber of silk is composed mainly of fibroin and is produced by certain insect larvae to form cocoons. The best-known silk is obtained from th ...

, wool

Wool is the textile fibre obtained from sheep and other mammals, especially goats, rabbits, and camelids. The term may also refer to inorganic materials, such as mineral wool and glass wool, that have properties similar to animal wool. ...

, and linen

Linen () is a textile made from the fibers of the flax plant.

Linen is very strong, absorbent, and dries faster than cotton. Because of these properties, linen is comfortable to wear in hot weather and is valued for use in garments. It also ...

fabrics were being eclipsed by cotton

Cotton is a soft, fluffy staple fiber that grows in a boll, or protective case, around the seeds of the cotton plants of the genus '' Gossypium'' in the mallow family Malvaceae. The fiber is almost pure cellulose, and can contain minor pe ...

which became the most important textile.

Innovations in carding and spinning enabled by advances in cast iron

Cast iron is a class of iron– carbon alloys with a carbon content more than 2%. Its usefulness derives from its relatively low melting temperature. The alloy constituents affect its color when fractured: white cast iron has carbide impuri ...

technology resulted in the creation of larger spinning mules and water frames. The machinery was housed in water-powered mills on stream

A stream is a continuous body of surface water flowing within the bed and banks of a channel. Depending on its location or certain characteristics, a stream may be referred to by a variety of local or regional names. Long large streams ...

s. The need for more power stimulated the production of steam-powered beam engines, and rotative mill engines transmitting the power to line shaft

A line shaft is a power-driven rotating shaft for power transmission that was used extensively from the Industrial Revolution until the early 20th century. Prior to the widespread use of electric motors small enough to be connected directly t ...

s on each floor of the mill. Surplus power capacity encouraged the construction of more sophisticated power looms working in weaving sheds. The scale of production in the mill towns round Manchester created a need for a commercial structure; for a cotton exchange and warehousing. The technology was used in woollen and worsted

Worsted ( or ) is a high-quality type of wool yarn, the fabric made from this yarn, and a yarn weight category. The name derives from Worstead, a village in the English county of Norfolk. That village, together with North Walsham and Aylsham ...

mills in the West Yorkshire

West Yorkshire is a metropolitan and ceremonial county in the Yorkshire and Humber Region of England. It is an inland and upland county having eastward-draining valleys while taking in the moors of the Pennines. West Yorkshire came into exi ...

and elsewhere.

Elements of the Industrial Revolution

The commencement of the Industrial Revolution is closely linked to a small number of innovations, made in the second half of the 18th century:The Industrial Revolution – Innovations

The commencement of the Industrial Revolution is closely linked to a small number of innovations, made in the second half of the 18th century:The Industrial Revolution – Innovations/ref> * John Kay's 1733

flying shuttle

The flying shuttle was one of the key developments in the industrialization of weaving during the early Industrial Revolution. It allowed a single weaver to weave much wider fabrics, and it could be mechanized, allowing for automatic machine l ...

enabled cloth to be woven faster, of a greater width, and for the process to later be mechanised. Cotton

Cotton is a soft, fluffy staple fiber that grows in a boll, or protective case, around the seeds of the cotton plants of the genus '' Gossypium'' in the mallow family Malvaceae. The fiber is almost pure cellulose, and can contain minor pe ...

spinning using Richard Arkwright

Sir Richard Arkwright (23 December 1732 – 3 August 1792) was an English inventor and a leading entrepreneur during the early Industrial Revolution. He is credited as the driving force behind the development of the spinning frame, known as ...

's water frame, James Hargreaves' Spinning Jenny, and Samuel Crompton's Spinning Mule (a combination of the Spinning Jenny and the Water Frame). This was patented in 1769 and so came out of patent in 1783. The end of the patent was rapidly followed by the erection of many cotton mills. Similar technology was subsequently applied to spinning worsted

Worsted ( or ) is a high-quality type of wool yarn, the fabric made from this yarn, and a yarn weight category. The name derives from Worstead, a village in the English county of Norfolk. That village, together with North Walsham and Aylsham ...

yarn

Yarn is a long continuous length of interlocked fibres, used in sewing, crocheting, knitting, weaving, embroidery, ropemaking, and the production of textiles. Thread is a type of yarn intended for sewing by hand or machine. Modern manu ...

for various textiles and flax

Flax, also known as common flax or linseed, is a flowering plant, ''Linum usitatissimum'', in the family Linaceae. It is cultivated as a food and fiber crop in regions of the world with temperate climates. Textiles made from flax are known in ...

for linen

Linen () is a textile made from the fibers of the flax plant.

Linen is very strong, absorbent, and dries faster than cotton. Because of these properties, linen is comfortable to wear in hot weather and is valued for use in garments. It also ...

.

*The improved steam engine

A steam engine is a heat engine that performs mechanical work using steam as its working fluid. The steam engine uses the force produced by steam pressure to push a piston back and forth inside a cylinder. This pushing force can be ...

invented by James Watt

James Watt (; 30 January 1736 (19 January 1736 OS) – 25 August 1819) was a Scottish inventor, mechanical engineer, and chemist who improved on Thomas Newcomen's 1712 Newcomen steam engine with his Watt steam engine in 1776, which was ...

and patented in 1775 was initially mainly used for pumping out mines, for water supply systems and to a lesser extend to power air blast for blast furnaces, but from the 1780s was applied to power machines. This enabled rapid development of efficient semi-automated factories on a previously unimaginable scale in places where waterpower was not available or not steady throughout the seasons. Early steam engines had poor speed control, which caused thread breakage, limiting their use in operations like spinning; however, this problem could be overcome by using the engine to pump water over a water wheel to drive the machinery.

*In the Iron industry, coke was finally applied to all stages of iron smelting

Smelting is a process of applying heat to ore, to extract a base metal. It is a form of extractive metallurgy. It is used to extract many metals from their ores, including silver, iron, copper, and other base metals. Smelting uses heat and a c ...

, replacing charcoal

Charcoal is a lightweight black carbon residue produced by strongly heating wood (or other animal and plant materials) in minimal oxygen to remove all water and volatile constituents. In the traditional version of this pyrolysis process, ...

. This had been achieved much earlier for lead

Lead is a chemical element with the symbol Pb (from the Latin ) and atomic number 82. It is a heavy metal that is denser than most common materials. Lead is soft and malleable, and also has a relatively low melting point. When freshly cut, ...

and copper

Copper is a chemical element with the symbol Cu (from la, cuprum) and atomic number 29. It is a soft, malleable, and ductile metal with very high thermal and electrical conductivity. A freshly exposed surface of pure copper has a pink ...

as well as for producing pig iron in a blast furnace, but the second stage in the production of bar iron depended on the use of potting and stamping (for which a patent

A patent is a type of intellectual property that gives its owner the legal right to exclude others from making, using, or selling an invention for a limited period of time in exchange for publishing an enabling disclosure of the invention."A ...

expired in 1786) or puddling (patented by Henry Cort in 1783 and 1784). Using a steam engine to power blast air to blast furnaces made higher furnace temperatures possible, which allowed the use of more lime to tie up sulfur in coal or coke. The steam engine also overcame the shortage of water power for iron works. Iron production surged after the 1750s when steam engines were increasingly employed in iron works.

These represent three 'leading sectors', in which there were key innovations, which allowed the economic takeoff by which the Industrial Revolution is usually defined. Later inventions such as the power loom and Richard Trevithick's high pressure steam engine

A steam engine is a heat engine that performs mechanical work using steam as its working fluid. The steam engine uses the force produced by steam pressure to push a piston back and forth inside a cylinder. This pushing force can be ...

were also important in the growing industrialisation of Britain. The application of steam engines to powering cotton mills and ironworks enabled these to be built in places that were most convenient because other resources were available, rather than where there was water to power a watermill.

Industry and invention

Before the 1760s, textile production was acottage industry

The putting-out system is a means of subcontracting work. Historically, it was also known as the workshop system and the domestic system. In putting-out, work is contracted by a central agent to subcontractors who complete the project via remote ...

using mainly flax

Flax, also known as common flax or linseed, is a flowering plant, ''Linum usitatissimum'', in the family Linaceae. It is cultivated as a food and fiber crop in regions of the world with temperate climates. Textiles made from flax are known in ...

and wool

Wool is the textile fibre obtained from sheep and other mammals, especially goats, rabbits, and camelids. The term may also refer to inorganic materials, such as mineral wool and glass wool, that have properties similar to animal wool. ...

. A typical weaving family would own one handloom, which would be operated by the man with help of a boy; the wife, girls and other women could make sufficient yarn

Yarn is a long continuous length of interlocked fibres, used in sewing, crocheting, knitting, weaving, embroidery, ropemaking, and the production of textiles. Thread is a type of yarn intended for sewing by hand or machine. Modern manu ...

for that loom.

The knowledge of textile production had existed for centuries. India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area, the List of countries and dependencies by population, second-most populous ...

had a textile industry that used cotton

Cotton is a soft, fluffy staple fiber that grows in a boll, or protective case, around the seeds of the cotton plants of the genus '' Gossypium'' in the mallow family Malvaceae. The fiber is almost pure cellulose, and can contain minor pe ...

, from which it manufactured cotton textiles. When raw cotton was exported to Europe it could be used to make fustian

Fustian is a variety of heavy cloth woven from cotton, chiefly prepared for menswear. It is also used figuratively to refer to pompous, inflated or pretentious writing or speech, from at least the time of Shakespeare. This literary use is b ...

.

Two systems had developed for spinning: the simple wheel, which used an intermittent process and the more refined, Saxony wheel

A spinning wheel is a device for spinning thread or yarn from fibres. It was fundamental to the cotton textile industry prior to the Industrial Revolution. It laid the foundations for later machinery such as the spinning jenny and spinning fr ...

which drove a differential spindle and flyer with a heck that guided the thread onto the bobbin, as a continuous process. This was satisfactory for use on handlooms, but neither of these wheels could produce enough thread for the looms after the invention by John Kay in 1734 of the flying shuttle

The flying shuttle was one of the key developments in the industrialization of weaving during the early Industrial Revolution. It allowed a single weaver to weave much wider fabrics, and it could be mechanized, allowing for automatic machine l ...

, which made the loom twice as productive.

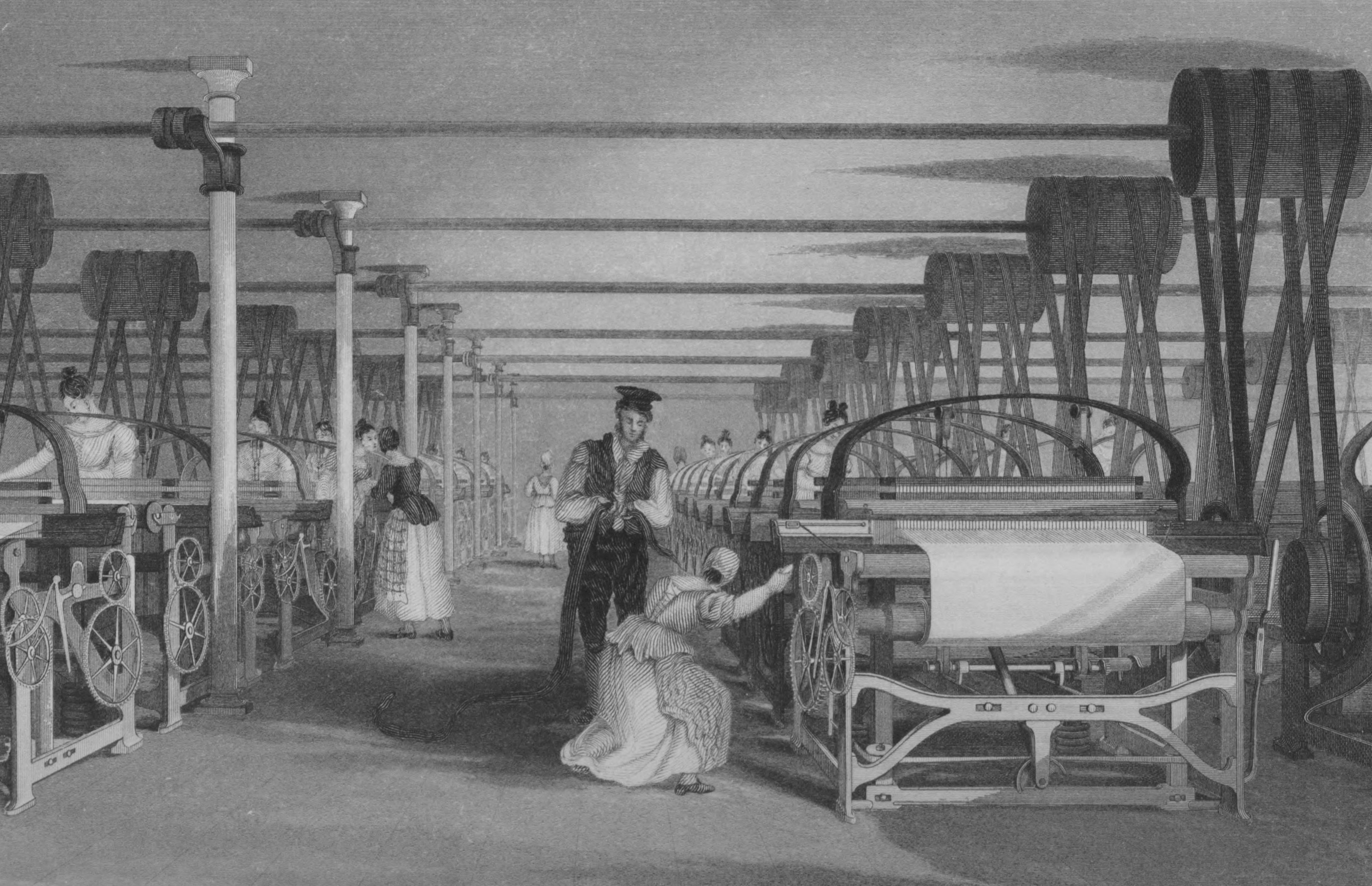

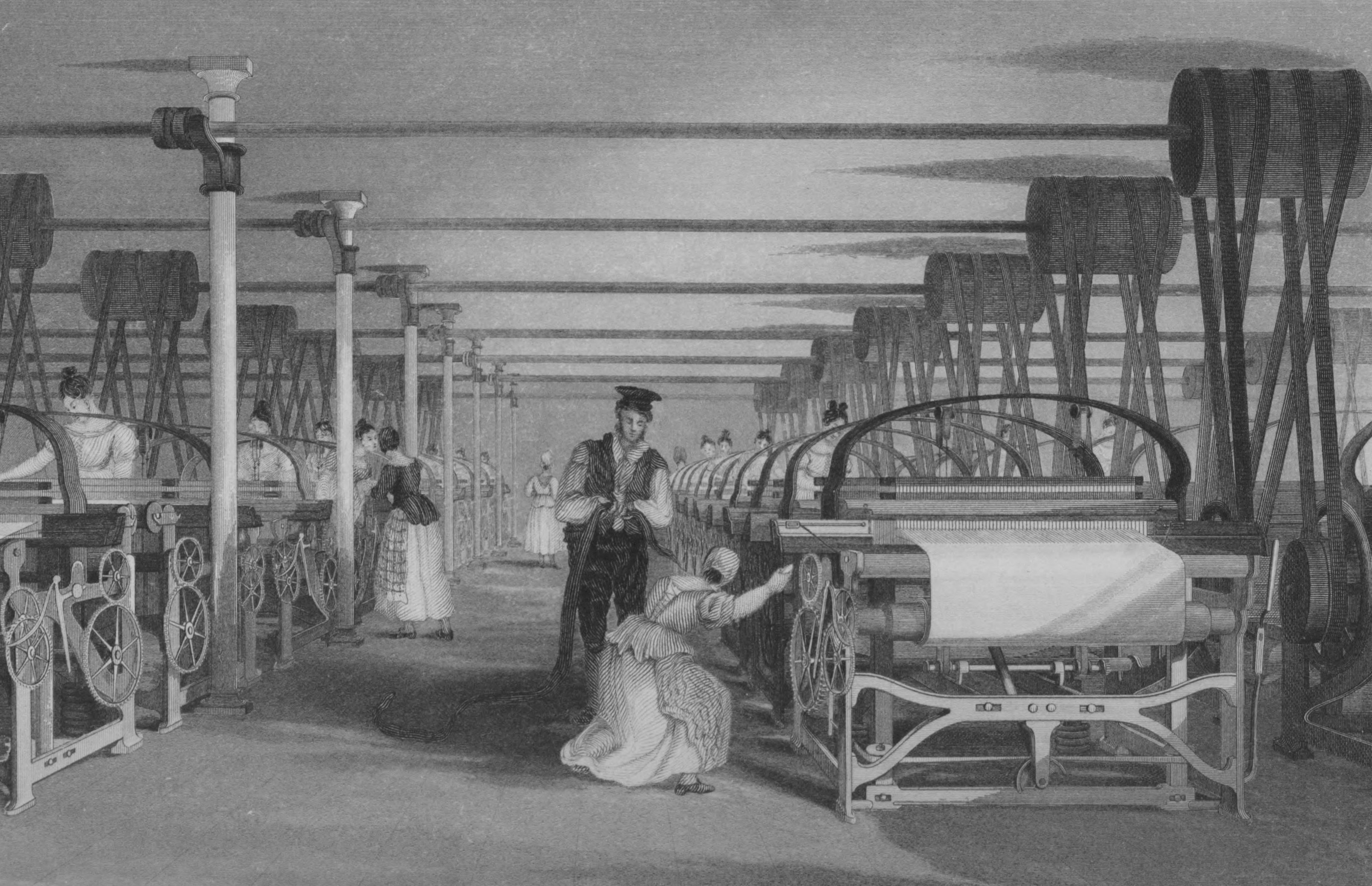

Cloth production moved away from the cottage into ''manufactories''. The first moves towards manufactories called mills were made in the spinning sector. The move in the weaving sector was later. By the 1820s, all cotton, wool, and worsted was spun in mills; but this yarn went to outworking weavers who continued to work in their own homes. A mill that specialized in weaving fabric was called a weaving shed.

Early inventions

East India Company

During the second half of the 17th century, the newly established factories of theEast India Company

The East India Company (EIC) was an English, and later British, joint-stock company founded in 1600 and dissolved in 1874. It was formed to trade in the Indian Ocean region, initially with the East Indies (the Indian subcontinent and Sou ...

in South Asia

South Asia is the southern subregion of Asia, which is defined in both geographical and ethno-cultural terms. The region consists of the countries of Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka.;;;;; ...

started to produce finished cotton goods in quantity for the British market. The imported Calico and chintz garments competed with, and acted as a substitute for Indian wool

Wool is the textile fibre obtained from sheep and other mammals, especially goats, rabbits, and camelids. The term may also refer to inorganic materials, such as mineral wool and glass wool, that have properties similar to animal wool. ...

and the linen

Linen () is a textile made from the fibers of the flax plant.

Linen is very strong, absorbent, and dries faster than cotton. Because of these properties, linen is comfortable to wear in hot weather and is valued for use in garments. It also ...

produce, resulting in local weavers, spinners, dyers, shepherds and farmers petitioning their MPs and in turn Parliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: representing the electorate, making laws, and overseeing the government via hearings and inquiries. Th ...

for a ban on the importation, and later the sale of woven cotton goods. Which they eventually achieved via the 1700 and 1721 Calico Acts. The acts banned the importation and later the sale of finished pure cotton produce, but did not restrict the importation of raw cotton, or sale or production of Fustian

Fustian is a variety of heavy cloth woven from cotton, chiefly prepared for menswear. It is also used figuratively to refer to pompous, inflated or pretentious writing or speech, from at least the time of Shakespeare. This literary use is b ...

.

The exemption of raw cotton saw two thousand bales of cotton being imported annually, from Asia and the Americas, and forming the basis of a new indigenous industry, initially producing Fustian

Fustian is a variety of heavy cloth woven from cotton, chiefly prepared for menswear. It is also used figuratively to refer to pompous, inflated or pretentious writing or speech, from at least the time of Shakespeare. This literary use is b ...

for the domestic market, though more importantly triggering the development of a series of mechanised spinning and weaving technologies, to process the material. This mechanised production was concentrated in new cotton mills, which slowly expanded till by the beginning of the 1770s seven thousand bales of cotton were imported annually, and pressure was put on Parliament, by the new mill owners, to remove the prohibition on the production and sale of pure cotton cloth, as they wished to compete with the EIC imports.

Indian cotton textiles, mainly those from Bengal

Bengal ( ; bn, বাংলা/বঙ্গ, translit=Bānglā/Bôngô, ) is a geopolitical, cultural and historical region in South Asia, specifically in the eastern part of the Indian subcontinent at the apex of the Bay of Bengal, predom ...

, continued to maintain a competitive advantage up until the 19th century. In order to compete with Indian goods, British merchants invested in labour-saving technical advancements, while the government

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a state.

In the case of its broad associative definition, government normally consists of legislature, executive, and judiciary. Government i ...

implemented protectionist policies such as bans and tariff

A tariff is a tax imposed by the government of a country or by a supranational union on imports or exports of goods. Besides being a source of revenue for the government, import duties can also be a form of regulation of foreign trade and p ...

s to restrict Indian imports. At the same time, the East India Company's rule in India contributed to its deindustrialization

Deindustrialization is a process of social and economic change caused by the removal or reduction of industrial capacity or activity in a country or region, especially of heavy industry or manufacturing industry.

There are different interp ...

, opening up a new market for foreign goods, while the capital accumulated in Bengal

Bengal ( ; bn, বাংলা/বঙ্গ, translit=Bānglā/Bôngô, ) is a geopolitical, cultural and historical region in South Asia, specifically in the eastern part of the Indian subcontinent at the apex of the Bay of Bengal, predom ...

after establishing direct control in 1757 was used by the East India Company to invest in British industries such as textile manufacturing, which contributed greatly to the emergence of the Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution was the transition to new manufacturing processes in Great Britain, continental Europe, and the United States, that occurred during the period from around 1760 to about 1820–1840. This transition included going f ...

. Britain eventually surpassed India as the world's leading cotton textile manufacturer in the 19th century.

Britain

During the 18th and 19th centuries, much of the imported cotton came fromplantation

A plantation is an agricultural estate, generally centered on a plantation house, meant for farming that specializes in cash crops, usually mainly planted with a single crop, with perhaps ancillary areas for vegetables for eating and so on. Th ...

s in the American South. In periods of political uncertainty in North America, during the Revolutionary War and later American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and t ...

, however, Britain relied more heavily on imports from the Indian subcontinent

The Indian subcontinent is a physiographical region in Southern Asia. It is situated on the Indian Plate, projecting southwards into the Indian Ocean from the Himalayas. Geopolitically, it includes the countries of Bangladesh, Bhutan, In ...

to supply its cotton manufacturing industry. Ports on the west coast of Britain, such as Liverpool

Liverpool is a City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. With a population of in 2019, it is the List of English districts by population, 10th largest English district by population and its E ...

, Bristol

Bristol () is a City status in the United Kingdom, city, Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county and unitary authority in England. Situated on the River Avon, Bristol, River Avon, it is bordered by the ceremonial counties of Glouces ...

, and Glasgow

Glasgow ( ; sco, Glesca or ; gd, Glaschu ) is the most populous city in Scotland and the fourth-most populous city in the United Kingdom, as well as being the 27th largest city by population in Europe. In 2020, it had an estimated popu ...

, became important in determining the sites of the cotton industry.

Lancashire

Lancashire ( , ; abbreviated Lancs) is the name of a historic county, ceremonial county, and non-metropolitan county in North West England. The boundaries of these three areas differ significantly.

The non-metropolitan county of Lancas ...

became a centre for the nascent cotton industry because the damp climate was better for spinning the yarn. As the cotton thread was not strong enough to use as warp

Warp, warped or warping may refer to:

Arts and entertainment Books and comics

* WaRP Graphics, an alternative comics publisher

* ''Warp'' (First Comics), comic book series published by First Comics based on the play ''Warp!''

* Warp (comics), a ...

, wool

Wool is the textile fibre obtained from sheep and other mammals, especially goats, rabbits, and camelids. The term may also refer to inorganic materials, such as mineral wool and glass wool, that have properties similar to animal wool. ...

or linen

Linen () is a textile made from the fibers of the flax plant.

Linen is very strong, absorbent, and dries faster than cotton. Because of these properties, linen is comfortable to wear in hot weather and is valued for use in garments. It also ...

or fustian

Fustian is a variety of heavy cloth woven from cotton, chiefly prepared for menswear. It is also used figuratively to refer to pompous, inflated or pretentious writing or speech, from at least the time of Shakespeare. This literary use is b ...

had to be used. Lancashire was an existing wool centre. Likewise, Glasgow

Glasgow ( ; sco, Glesca or ; gd, Glaschu ) is the most populous city in Scotland and the fourth-most populous city in the United Kingdom, as well as being the 27th largest city by population in Europe. In 2020, it had an estimated popu ...

benefited from the same damp climate.

The early advances in weaving had been halted by the lack of thread. The spinning process was slow and the weavers needed more cotton and wool thread than their families could produce. In the 1760s, James Hargreaves improved thread production when he invented the Spinning Jenny. By the end of the decade, Richard Arkwright

Sir Richard Arkwright (23 December 1732 – 3 August 1792) was an English inventor and a leading entrepreneur during the early Industrial Revolution. He is credited as the driving force behind the development of the spinning frame, known as ...

had developed the water frame. This invention had two important consequences: it improved the quality of the thread, which meant that the cotton industry was no longer dependent on wool or linen to make the warp, and it took spinning away from the artisans' homes to specific locations where fast-flowing streams could provide the water power needed to drive the larger machines. The Western Pennines of Lancashire became the centre for the cotton industry. Not long after the invention of the water frame, Samuel Crompton combined the principles of the Spinning Jenny and the Water Frame to produce his Spinning Mule. This provided even tougher and finer cotton thread.

The textile industry was also to benefit from other developments of the period. As early as 1691, Thomas Savery

Thomas Savery (; c. 1650 – 15 May 1715) was an English inventor and engineer. He invented the first commercially used steam-powered device, a steam pump which is often referred to as the "Savery engine". Savery's steam pump was a revolutionar ...

had made a vacuum steam engine. His design, which was unsafe, was improved by Thomas Newcomen in 1698. In 1765, James Watt

James Watt (; 30 January 1736 (19 January 1736 OS) – 25 August 1819) was a Scottish inventor, mechanical engineer, and chemist who improved on Thomas Newcomen's 1712 Newcomen steam engine with his Watt steam engine in 1776, which was ...

further modified Newcomen's engine to design an external condenser steam engine. Watt continued to make improvements on his design, producing a separate condenser engine in 1774 and a rotating separate condensing engine in 1781. Watt formed a partnership with businessman Matthew Boulton

Matthew Boulton (; 3 September 172817 August 1809) was an English manufacturer and business partner of Scottish engineer James Watt. In the final quarter of the 18th century, the partnership installed hundreds of Boulton & Watt steam engin ...

, and together they manufactured steam engines which could be used by industry.

Prior to the 1780s, most of the fine quality cotton muslin in circulation in Britain had been manufactured in India. Due to advances in technique, British "mull muslin" was able to compete in quality with Indian muslin by the end of the 18th century.

Timeline of inventions

In 1734 in Bury, Lancashire, John Kay invented theflying shuttle

The flying shuttle was one of the key developments in the industrialization of weaving during the early Industrial Revolution. It allowed a single weaver to weave much wider fabrics, and it could be mechanized, allowing for automatic machine l ...

— one of the first of a series of inventions associated with the cotton industry. The flying shuttle increased the width of cotton cloth and speed of production of a single weaver at a loom

A loom is a device used to weave cloth and tapestry. The basic purpose of any loom is to hold the warp threads under tension to facilitate the interweaving of the weft threads. The precise shape of the loom and its mechanics may vary, but t ...

. Resistance by workers to the perceived threat to jobs delayed the widespread introduction of this technology, even though the higher rate of production generated an increased demand for spun cotton.  In 1738, Lewis Paul (one of the community of

In 1738, Lewis Paul (one of the community of Huguenot

The Huguenots ( , also , ) were a religious group of French Protestants who held to the Reformed, or Calvinist, tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss political leader, the Genevan burgomaster Be ...

weavers that had been driven out of France in a wave of religious persecution) settled in Birmingham

Birmingham ( ) is a city and metropolitan borough in the metropolitan county of West Midlands in England. It is the second-largest city in the United Kingdom with a population of 1.145 million in the city proper, 2.92 million in the We ...

and with John Wyatt, of that town, they patented the Roller Spinning machine and the flyer-and-bobbin system, for drawing wool

Wool is the textile fibre obtained from sheep and other mammals, especially goats, rabbits, and camelids. The term may also refer to inorganic materials, such as mineral wool and glass wool, that have properties similar to animal wool. ...

to a more even thickness. Using two sets of rollers that travelled at different speeds yarn

Yarn is a long continuous length of interlocked fibres, used in sewing, crocheting, knitting, weaving, embroidery, ropemaking, and the production of textiles. Thread is a type of yarn intended for sewing by hand or machine. Modern manu ...

could be twisted and spun quickly and efficiently. This was later used in the first cotton

Cotton is a soft, fluffy staple fiber that grows in a boll, or protective case, around the seeds of the cotton plants of the genus '' Gossypium'' in the mallow family Malvaceae. The fiber is almost pure cellulose, and can contain minor pe ...

spinning mill during the Industrial Revolution.

1742: Paul and Wyatt opened a mill in Birmingham which used their new rolling machine powered by donkey; this was not profitable and was soon closed.

1743: A factory opened in Northampton

Northampton () is a market town and civil parish in the East Midlands of England, on the River Nene, north-west of London and south-east of Birmingham. The county town of Northamptonshire, Northampton is one of the largest towns in England ...

, fifty spindles turned on five of Paul and Wyatt's machines proving more successful than their first mill. This operated until 1764.

1748: Lewis Paul invented the hand driven carding machine. A coat of wire slips were placed around a card which was then wrapped around a cylinder. Lewis's invention was later developed and improved by Richard Arkwright

Sir Richard Arkwright (23 December 1732 – 3 August 1792) was an English inventor and a leading entrepreneur during the early Industrial Revolution. He is credited as the driving force behind the development of the spinning frame, known as ...

and Samuel Crompton, although this came about under great suspicion after a fire at Daniel Bourn's factory in Leominster which specifically used Paul and Wyatt's spindles. Bourn produced a similar patent in the same year.

1758: Paul and Wyatt based in Birmingham

Birmingham ( ) is a city and metropolitan borough in the metropolitan county of West Midlands in England. It is the second-largest city in the United Kingdom with a population of 1.145 million in the city proper, 2.92 million in the We ...

improved their roller spinning machine and took out a second patent. Richard Arkwright later used this as the model for his water frame.

Start of the Revolution

The Duke of Bridgewater's canal connected Manchester to the coal fields of Worsley. It was opened in July 1761.Matthew Boulton

Matthew Boulton (; 3 September 172817 August 1809) was an English manufacturer and business partner of Scottish engineer James Watt. In the final quarter of the 18th century, the partnership installed hundreds of Boulton & Watt steam engin ...

opened the Soho Foundry engineering works in Handsworth, Birmingham

Birmingham ( ) is a city and metropolitan borough in the metropolitan county of West Midlands in England. It is the second-largest city in the United Kingdom with a population of 1.145 million in the city proper, 2.92 million in the We ...

in 1762. These were both events that enabled cotton mill construction and the move away from home-based production.

In 1764, Thorp Mill, the first water-powered cotton mill in the world was constructed at Royton, Lancashire

Lancashire ( , ; abbreviated Lancs) is the name of a historic county, ceremonial county, and non-metropolitan county in North West England. The boundaries of these three areas differ significantly.

The non-metropolitan county of Lancas ...

, England. It was used for carding cotton.

The multiple spindle spinning jenny was invented in 1764. James Hargreaves is credited as the inventor. This machine increased the thread production capacity of a single worker — initially eightfold and subsequently much further. Others credit the original invention to Thomas Highs. Industrial unrest forced Hargreaves to leave Blackburn, but more importantly for him, his unpatented idea was exploited by others. He finally patented it in 1770. As a result, there were over 20,000 spinning jennies in use (mainly unlicensed) by the time of his death.

Richard Arkwright

Sir Richard Arkwright (23 December 1732 – 3 August 1792) was an English inventor and a leading entrepreneur during the early Industrial Revolution. He is credited as the driving force behind the development of the spinning frame, known as ...

first spinning mill, Cromford Mill

Cromford Mill is the world's first water-powered cotton spinning mill, developed by Richard Arkwright in 1771 in Cromford, Derbyshire, England. The mill structure is classified as a Grade I listed building. It is now the centrepiece of the ...

, Derbyshire

Derbyshire ( ) is a ceremonial county in the East Midlands, England. It includes much of the Peak District National Park, the southern end of the Pennine range of hills and part of the National Forest. It borders Greater Manchester to the nor ...

, was built in 1771. It contained his invention the water frame. The water frame was developed from the spinning frame that Arkwright had developed with (a different) John Kay, from Warrington. The original design was again claimed by Thomas Highs: which he purposed he had patent

A patent is a type of intellectual property that gives its owner the legal right to exclude others from making, using, or selling an invention for a limited period of time in exchange for publishing an enabling disclosure of the invention."A ...

ed in 1769.Press the 'Ingenious' button and use search key '10302171' for the patent Arkwright used waterwheels to power the textile machinery. His initial attempts at driving the frame had used horse power, but a mill needed far more power. Using a waterwheel demanded a location with a ready supply of water, hence the mill at Cromford. This mill is preserved as part of the Derwent Valley Mills Arkwright generated jobs and constructed accommodation for his workers which he moved into the area. This led to a sizeable industrial community. Arkwright protected his investment from industrial rivals and potentially disruptive workers. This model worked and he expanded his operations to other parts of the country.

Matthew Boulton

Matthew Boulton (; 3 September 172817 August 1809) was an English manufacturer and business partner of Scottish engineer James Watt. In the final quarter of the 18th century, the partnership installed hundreds of Boulton & Watt steam engin ...

partnership with Scottish engineer James Watt

James Watt (; 30 January 1736 (19 January 1736 OS) – 25 August 1819) was a Scottish inventor, mechanical engineer, and chemist who improved on Thomas Newcomen's 1712 Newcomen steam engine with his Watt steam engine in 1776, which was ...

resulted, in 1775, in the commercial production of the more efficient Watt steam engine

The Watt steam engine design became synonymous with steam engines, and it was many years before significantly new designs began to replace the basic Watt design.

The first steam engines, introduced by Thomas Newcomen in 1712, were of the "a ...

which used a separate condensor.

Samuel Crompton of Bolton combined elements of the spinning jenny and water frame in 1779, creating the spinning mule. This mule produced a stronger thread than the water frame could. Thus in 1780, there were two viable hand-operated spinning systems that could be easily adapted to run by power of water. Early mules were suitable for producing yarn for use in the manufacture of muslin

Muslin () is a cotton fabric of plain weave. It is made in a wide range of weights from delicate sheers to coarse sheeting. It gets its name from the city of Mosul, Iraq, where it was first manufactured.

Muslin of uncommonly delicate hands ...

, and were known as the muslin wheel or the Hall i' th' Wood (pronounced Hall-ith-wood) wheel. As with Kay and Hargreaves, Crompton was not able to exploit his invention for his own profit, and died a pauper.

In 1783 a mill was built in Manchester at Shudehill, at the highest point in the city away from the river. Shudehill Mill

Shudehill Mill or Simpson's Mill was a very early cotton mill in Manchester city centre, England. It was built in 1782 by for Richard Arkwright and his partners and destroyed by fire in 1854. It was rebuilt and finally destroyed during the Ma ...

was powered by a 30 ft diameter waterwheel. Two storage ponds were built, and the water from one passed from one to the other turning the wheel. A steam driven pump returned the water to the higher reservoir. The steam engine was of the atmospheric type. An improvement devised by Joshua Wrigley, trialled in Chorlton-upon-Medlock

Chorlton-on-Medlock or Chorlton-upon-Medlock is an inner city area of Manchester, England.

Historically in Lancashire, Chorlton-on-Medlock is bordered to the north by the River Medlock, which runs immediately south of Manchester city centre. I ...

used two Savery engines to supplement the river

A river is a natural flowing watercourse, usually freshwater, flowing towards an ocean, sea, lake or another river. In some cases, a river flows into the ground and becomes dry at the end of its course without reaching another body of ...

in driving on overshot waterwheel

A water wheel is a machine for converting the energy of flowing or falling water into useful forms of power, often in a watermill. A water wheel consists of a wheel (usually constructed from wood or metal), with a number of blades or bucket ...

.

In 1784, Edmund Cartwright invented the power loom, and produced a prototype in the following year. His initial venture to exploit this technology failed, although his advances were recognised by others in the industry. Others such as Robert Grimshaw

The name Robert is an ancient Germanic given name, from Proto-Germanic "fame" and "bright" (''Hrōþiberhtaz''). Compare Old Dutch ''Robrecht'' and Old High German ''Hrodebert'' (a compound of '' Hruod'' ( non, Hróðr) "fame, glory, honou ...

(whose factory was destroyed in 1790 as part of the growing reaction against the mechanization of the industry) and Austin – developed the ideas further.

In the 1790s industrialists, such as John Marshall at Marshall's Mill

Marshall's Mill is a former flax spinning mill on Marshall Street in Holbeck, Leeds, West Yorkshire, England.

Marshall's Mill was part of a complex begun in 1791–92 by English industrial pioneer John Marshall. It was originally a four-store ...

in Leeds, started to work on ways to apply some of the techniques which had proved so successful in cotton to other materials, such as flax.

In 1803, William Radcliffe invented the dressing frame

Dressing commonly refers to:

* Dressing (knot), the process of arranging a knot

* Dressing (medical), a medical covering for a wound, usually made of cloth

* Dressing, putting on clothing

Dressing may also refer to:

Food

* Salad dressing, a typ ...

which was patent

A patent is a type of intellectual property that gives its owner the legal right to exclude others from making, using, or selling an invention for a limited period of time in exchange for publishing an enabling disclosure of the invention."A ...

ed under the name of Thomas Johnson which enabled power looms to operate continuously.

Later developments

With the Cartwright Loom, the Spinning Mule and the Boulton & Watt steam engine, the pieces were in place to build a mechanised textile industry. From this point there were no new inventions, but a continuous improvement in technology as the mill-owner strove to reduce cost and improve quality. Developments in the transport infrastructure - the canals and, after 1831, the railways - facilitated the import of raw materials and export of finished cloth. The use of water power to drive mills was supplemented by steam driven water pumps, and then superseded completely by thesteam engines

A steam engine is a heat engine that performs mechanical work using steam as its working fluid. The steam engine uses the force produced by steam pressure to push a piston back and forth inside a cylinder. This pushing force can be tra ...

. For example, Samuel Greg

Samuel Greg (26 March 1758 – 4 June 1834) was an Irish-born industrialist and entrepreneur of the early Industrial Revolution and a pioneer of the factory system. He built Quarry Bank Mill, which at his retirement was the largest textile mi ...

joined his uncle's firm of textile merchants, and, on taking over the company in 1782, he sought out a site to establish a mill. Quarry Bank Mill

Quarry Bank Mill (also known as Styal Mill) in Styal, Cheshire, England, is one of the best preserved textile factories of the Industrial Revolution. Built in 1784, the cotton mill is recorded in the National Heritage List for England as a ...

was built on the River Bollin at Styal in Cheshire

Cheshire ( ) is a ceremonial and historic county in North West England, bordered by Wales to the west, Merseyside and Greater Manchester to the north, Derbyshire to the east, and Staffordshire and Shropshire to the south. Cheshire's county tow ...

. It was initially powered by a water wheel

A water wheel is a machine for converting the energy of flowing or falling water into useful forms of power, often in a watermill. A water wheel consists of a wheel (usually constructed from wood or metal), with a number of blades or buckets ...

, but installed steam engines in 1810. In 1830, the average power of a mill engine was 48 hp, but Quarry Bank mill installed a new 100 hp water wheel. This was to change in 1836, when Horrocks & Nuttall, Preston took delivery of 160 hp double engine. William Fairbairn addressed the problem of line-shafting and was responsible for improving the efficiency of the mill. In 1815 he replaced the wooden turning shafts that drove the machines at 50rpm, to wrought iron shafting working at 250 rpm, these were a third of the weight of the previous ones and absorbed less power. The mill operated until 1959.

Robert's power loom

In 1830, using an 1822 patent, Richard Roberts manufactured the first loom with a cast-iron frame, the Roberts Loom. In 1842 James Bullough and William Kenworthy, made the

In 1830, using an 1822 patent, Richard Roberts manufactured the first loom with a cast-iron frame, the Roberts Loom. In 1842 James Bullough and William Kenworthy, made the Lancashire Loom

The Lancashire Loom was a semi-automatic power loom invented by James Bullough and William Kenworthy in 1842. Although it is self-acting, it has to be stopped to recharge empty shuttles. It was the mainstay of the Lancashire cotton industry for ...

. It is a semiautomatic power loom. Although it is self-acting, it has to be stopped to recharge empty shuttles. It was the mainstay of the Lancashire

Lancashire ( , ; abbreviated Lancs) is the name of a historic county, ceremonial county, and non-metropolitan county in North West England. The boundaries of these three areas differ significantly.

The non-metropolitan county of Lancas ...

cotton industry for a century, when the Northrop Loom

The Northrop Loom was a fully automatic power loom marketed by George Draper and Sons, Hopedale, Massachusetts beginning in 1895. It was named after James Henry Northrop who invented the shuttle-charging mechanism.

Background

James Henry N ...

invented in 1894 with an automatic weft replenishment function gained ascendancy.

Robert's self acting mule

Also in 1830, Richard Roberts patented the first self-acting mule. The

Also in 1830, Richard Roberts patented the first self-acting mule. The Stalybridge mule spinners strike

Stalybridge () is a town in Tameside, Greater Manchester, England, with a population of 23,731 at the 2011 Census.

Historically divided between Cheshire and Lancashire, it is east of Manchester city centre and north-west of Glossop.

When a ...

was in 1824, this stimulated research into the problem of applying power to the winding stroke of the mule. The ''draw'' while spinning had been assisted by power, but the ''push'' of the wind had been done manually by the spinner, the mule could be operated by semiskilled labour. Before 1830, the spinner would operate a partially powered mule with a maximum of 400 spindles after, self-acting mules with up to 1,300 spindles could be built.

The savings that could be made with this technology were considerable. A worker spinning cotton at a hand-powered spinning wheel in the 18th century would take more than 50,000 hours to spin 100 lb of cotton; by the 1790s, the same quantity could be spun in 300 hours by mule, and with a self-acting mule it could be spun by one worker in just 135 hours.

Working practices

The nature of work changed during industrialisation from a craft production model to a factory-centric model. It was during the years 1761 to 1850 that these changes happened. Textile factories organized workers' lives much differently from craft production. Handloom weavers worked at their own pace, with their own tools, and within their own cottages. Factories set hours of work, and the machinery within them shaped the pace of work. Factories brought workers together within one building to work on machinery that they did not own. Factories also increased the division of labour. They narrowed the number and scope of tasks. They included children and women within a common production process. As Manchester mill ownerFriedrich Engels

Friedrich Engels ( ,"Engels"

'' Marx's book '

online

*Cameron, Edward H. '' Samuel Slater, Father of American Manufactures'' (1960) scholarly biography * * Griffin, Emma, ''A Short History of the British Industrial Revolution'' (Palgrave, 2010), pp. 86–104 * * * * * Ray, Indrajit (2011)

''Bengal Industries and the British Industrial Revolution (1757-1857)''

in JSTOR

* Tucker, Barbara M. '' Samuel Slater and the Origins of the American Textile Industry, 1790–1860'' (1984) *

The cotton industry during the Industrial Revolution

2014)

{{DEFAULTSORT:Textile Manufacture During The Industrial Revolution T History of the textile industry Cotton industry in England T Textile mills in England Textile mills in the United Kingdom . T T History of the textile industry in the United Kingdom

'' Marx's book '

Das Kapital

''Das Kapital'', also known as ''Capital: A Critique of Political Economy'' or sometimes simply ''Capital'' (german: Das Kapital. Kritik der politischen Ökonomie, link=no, ; 1867–1883), is a foundational theoretical text in materialist phi ...

'.

At times, the workers rebelled against poor wages. The first major industrial action in Scotland was that of the Calton weavers in Glasgow, who went on strike for higher wages in the summer of 1787. In the ensuing disturbances, troops were called in to keep the peace and three of the weavers were killed. There was continued unrest. In Manchester in May 1808, 15,000 protesters gathered on St George's Fields and were fired on by dragoons, with one man dying. A strike followed, but was eventually settled by a small wage increase.

In the general strike of 1842, half a million workers demanded the Charter

A charter is the grant of authority or rights, stating that the granter formally recognizes the prerogative of the recipient to exercise the rights specified. It is implicit that the granter retains superiority (or sovereignty), and that the re ...

and an end to pay cuts. Again, troops were called in to keep the peace, and the strike leaders were arrested, but some of the worker demands were met.

The early textile factories employed a large share of children, but the share declined over time. In England and Scotland in 1788, two-thirds of the workers in 143 water-powered cotton mills were described as children. Sir Robert Peel, a mill owner turned reformer, promoted the 1802 Health and Morals of Apprentices Act, which was intended to prevent pauper children from working more than 12 hours a day in mills. Children had started in the mills at around the age of four, working as mule scavenger

Scavengers were employed in 18th and 19th century in cotton mills, predominantly in the UK and the United States, to clean and recoup the area underneath a spinning mule. The cotton wastage that gathered on the floor was seen as too valuable fo ...

s under the working machinery until they were eight, they progressed to working as little piecers

Little is a synonym for small size and may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* ''Little'' (album), 1990 debut album of Vic Chesnutt

* ''Little'' (film), 2019 American comedy film

*The Littles, a series of children's novels by American author John P ...

which they did until they were 15. During this time they worked 14 to 16 hours a day, being beaten if they fell asleep. The children were sent to the mills of Derbyshire, Yorkshire and Lancashire from the workhouse

In Britain, a workhouse () was an institution where those unable to support themselves financially were offered accommodation and employment. (In Scotland, they were usually known as poorhouses.) The earliest known use of the term ''workhouse' ...

s in London and other towns in the south of England. A well-documented example was that of Litton Mill

Litton Mill is a textile mill at Millers Dale, near Tideswell in Derbyshire.

The original 19th-century mill became notorious during the Industrial Revolution for its unsavoury employment practices, luridly described by the commentators of the ...

. Further legislation followed. By 1835, the share of the workforce under 18 years of age in cotton mills in England and Scotland had fallen to 43%. About half of workers in Manchester

Manchester () is a city in Greater Manchester, England. It had a population of 552,000 in 2021. It is bordered by the Cheshire Plain to the south, the Pennines to the north and east, and the neighbouring city of Salford to the west. The ...

and Stockport cotton factories surveyed in 1818 and 1819 had begun work at under ten years of age. Most of the adult workers in cotton factories in mid-19th-century Britain were workers who had begun work as child labourers. The growth of this experienced adult factory workforce helps to account for the shift away from child labour in textile factories.

A representative early spinning mill 1771

Cromford Mill

Cromford Mill is the world's first water-powered cotton spinning mill, developed by Richard Arkwright in 1771 in Cromford, Derbyshire, England. The mill structure is classified as a Grade I listed building. It is now the centrepiece of the ...

was an early Arkwright mill and was the model for future mills. The site at Cromford had year-round supply of warm water from the sough

A sough (pronounced /saʊ/ or /sʌf/) is an underground channel for draining water out of a mine. Ideally the bottom of the mine would be higher than the outlet, but where the mine sump is lower, water must be pumped up to the sough.

Derbyshire ...

which drained water from nearby lead

Lead is a chemical element with the symbol Pb (from the Latin ) and atomic number 82. It is a heavy metal that is denser than most common materials. Lead is soft and malleable, and also has a relatively low melting point. When freshly cut, ...

mines, together with another brook. It was a five-storey mill. Starting in 1772, the mills ran day and night with two 12-hour shifts.

It started with 200 workers, more than the locality could provide so Arkwright built housing for them nearby, one of the first manufacturers to do so. Most of the employees were women and children, the youngest being only 7 years old. Later, the minimum age was raised to 10 and the children were given 6 hours of education a week, so that they could do the record keeping their illiterate parents could not.

The first stage of the spinning process is carding, initially this was done by hand, but in 1775 he took out a second patent for a water-powered carding machine and this led to increased output. He was soon building further mills on this site and eventually employed 1,000 workers at Cromford. By the time of his death in 1792, he was the wealthiest untitled person in Britain.

The gate to Cromford Mill was shut at precisely 6am and 6pm every day and any worker who failed to get through it not only lost a day's pay but was fined another day's pay. In 1779, Arkwright installed a cannon, loaded with grapeshot, just inside the factory gate, as a warning to would-be rioting textile workers, who had burned down another of his mills in Birkacre, Lancashire. The cannon was never used.

The mill structure is classified as a Grade I listed building, it was first classified in June 1950.

A representative mid-century spinning mill 1840

Brunswick Mill, Ancoats

Brunswick Mill, Ancoats is a former cotton spinning mill on Bradford Road in Ancoats, Manchester, England. The mill was built around 1840, part of a group of mills built along the Ashton Canal, and at that time it was one of the country's lar ...

is a cotton spinning mill in Ancoats, Manchester, Greater Manchester. It was built around 1840, part of a group of mills built along the Ashton Canal, and at that time it was one of the country's largest mills. It was built round a quadrangle, a seven-storey block faced the canal. It was taken over by the Lancashire Cotton Corporation in the 1930s and passed to Courtaulds in 1964. Production finished in 1967.

The Brunswick mill was built around 1840 in one phase. The main seven storey block that faces the Ashton Canal was used for spinning. The preparation was done on the second floor and the self-acting mules with 400 spindles were arranged transversely on the floors above. The wings contained the blowing rooms, some spinning and ancillary processes like winding. The four storey range facing Bradford Road was used for warehousing and offices. The mill was built by David Bellhouse, but it is suspected that William Fairbairn was involved in the design. It is built from brick, and has slate roofs. Fireproof internal construction was now standard. Brunswick was built using cast iron columns and beams, each floor was vaulted with transverse brick arches. There was no wood in the structure. It was powered by a large double beam engine.

In 1850 the mill had some 276 carding machines, and 77,000 mule spindles, 20 drawing frames, fifty slubbing frames and eighty one roving frames.

The structure was good and it successfully converted to ring spinning in 1920- and was the first mill to adopt mains electricity as its principal source of power. The mill structure was classified as a Grade II listed building in June 1994.

Export of technology

While profiting from expertise arriving from overseas (e.g. Lewis Paul), Britain was very protective of home-grown technology. In particular,engineer

Engineers, as practitioners of engineering, are professionals who Invention, invent, design, analyze, build and test machines, complex systems, structures, gadgets and materials to fulfill functional objectives and requirements while considerin ...

s with skills in constructing the textile mills and machinery were not permitted to emigrate — particularly to the fledgeling America.

;Horse power (1780–1790)

The earliest cotton mills in the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

were horse-powered. The first mill to use this method was the Beverly Cotton Manufactory, built in Beverly, Massachusetts

Beverly is a city in Essex County, Massachusetts, and a suburb of Boston. The population was 42,670 at the time of the 2020 United States Census. A resort, residential, and manufacturing community on the Massachusetts North Shore, Beverly incl ...

. It was started on 18 August 1788 by entrepreneur John Cabot and brothers. It was operated in joint by Moses Brown, Israel Thorndike, Joshua Fisher, Henry Higginson, and Deborah Higginson Cabot. The Salem Mercury

Salem may refer to: Places

Canada

Ontario

* Bruce County

** Salem, Arran–Elderslie, Ontario, in the municipality of Arran–Elderslie

** Salem, South Bruce, Ontario, in the municipality of South Bruce

* Salem, Dufferin County, Ontario, part ...

reported that in April 1788 the equipment for the mill was complete, consisting of a spinning jenny, a carding machine, warping machine, and other tools. That same year the mill's location was finalized and built in the rural outsets of North Beverly. The location had the presence of natural water, but it was cited the water was used for upkeep of the horses and cleaning of equipment, and not for mass-production.

Much of the internal designs of the Beverly mill were hidden due to concerns of competitors stealing designs. The beginning efforts were all researched behind closed doors, even to the point that the owners of the mill set up milling equipment on their estates to experiment with the process. There were no published articles describing exactly how their process worked in detail. Additionally, the mill's horse-powered technology was quickly dwarfed by new water-powered methods."Made In Beverly-A History of Beverly Industry", by Daniel J. Hoisington. A publication of the Beverly Historic District Commission. 1989.

;Slater

Following the creation of the United States, an engineer who had worked as an apprentice to Arkwright's partner Jedediah Strutt evaded the ban. In 1789, Samuel Slater took his skills in designing and constructing factories to New England

New England is a region comprising six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York to the west and by the Canadian provinces ...

, and he was soon engaged in reproducing the textile mills that helped America with its own industrial revolution.

Local inventions spurred this on, and in 1793 Eli Whitney invented and patented the cotton gin

A cotton gin—meaning "cotton engine"—is a machine that quickly and easily separates cotton fibers from their seeds, enabling much greater productivity than manual cotton separation.. Reprinted by McGraw-Hill, New York and London, 1926 (); a ...

, which sped up the processing of raw cotton by over 50 times.

1800s

In the mid-1800s some of the technology and tools were sold and exported to Russia. The Morozovs family, a well known 19th-century Russian merchant and textile family established aprivate company

A privately held company (or simply a private company) is a company whose shares and related rights or obligations are not offered for public subscription or publicly negotiated in the respective listed markets, but rather the company's stock is ...

in central Russia that produced dyed fabrics on an industrial scale. Savva Morozov studied the process at the University of Cambridge

, mottoeng = Literal: From here, light and sacred draughts.

Non literal: From this place, we gain enlightenment and precious knowledge.

, established =

, other_name = The Chancellor, Masters and Schola ...

in England and later, with the help of his family, widened his family's business and made it one of the most profitable in the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War ...

.

Art and literature

* William Blake: Jerusalem - dark satanic mills (1804) and other works. *Mrs Gaskell

Elizabeth Cleghorn Gaskell (''née'' Stevenson; 29 September 1810 – 12 November 1865), often referred to as Mrs Gaskell, was an English novelist, biographer and short story writer. Her novels offer a detailed portrait of the lives of many st ...

: Mary Barton (1848), North and South North and South may refer to:

Literature

* ''North and South'' (Gaskell novel), an 1854 novel by Elizabeth Gaskell

* ''North and South'' (trilogy), a series of novels by John Jakes (1982–1987)

** ''North and South'' (Jakes novel), first novel ...

(1855)

* Charlotte Brontë: Shirley (1849)

*Cynthia Harrod-Eagles

Cynthia Harrod-Eagles (born 13 August 1948) is a British writer of romance and mystery novels. She normally writes under her own name but also uses the pseudonyms Emma Woodhouse and Elizabeth Bennett. Cynthia was born on 13 August 1948 at Sheph ...

wrote fictional accounts of the early days of factories and the events of the Industrial Revolution in ''The Maiden'' (1985), ''The Flood Tide'' (1986), ''The Tangled Thread'' (1987), ''The Emperor'' (1988), ''The Victory'' (1989), ''The Regency'' (1990), ''The Reckoning'' (1992) and ''The Devil's Horse'' (1993), Volumes 8-13, 15 and 16 of The Morland Dynasty

''The Morland Dynasty'' is a series of historical novels by Cynthia Harrod-Eagles, in the genre of a family saga. They recount the lives of the Morland family of York, England and their national and international relatives and associates.

There ...

.

See also

*Textile manufacturing by pre-industrial methods

Textile manufacturing is one of the oldest human activities. The oldest known textiles date back to about 5000 B.C. In order to make textiles, the first requirement is a source of fibre from which a yarn can be made, primarily by spinning. The y ...

References

;Footnotes ;Notes ;Bibliography * Copeland, Melvin Thomas. ''The cotton manufacturing industry of the United States'' (Harvard University Press, 1912online

*Cameron, Edward H. '' Samuel Slater, Father of American Manufactures'' (1960) scholarly biography * * Griffin, Emma, ''A Short History of the British Industrial Revolution'' (Palgrave, 2010), pp. 86–104 * * * * * Ray, Indrajit (2011)

''Bengal Industries and the British Industrial Revolution (1757-1857)''

Routledge

Routledge () is a British multinational publisher. It was founded in 1836 by George Routledge, and specialises in providing academic books, journals and online resources in the fields of the humanities, behavioural science, education, law ...

, .

* Tucker, Barbara M. "The Merchant, the Manufacturer, and the Factory Manager: The Case of Samuel Slater," ''Business History Review,'' Vol. 55, No. 3 (Autumn, 1981), pp. 297–31in JSTOR

* Tucker, Barbara M. '' Samuel Slater and the Origins of the American Textile Industry, 1790–1860'' (1984) *

External links

The cotton industry during the Industrial Revolution

2014)

{{DEFAULTSORT:Textile Manufacture During The Industrial Revolution T History of the textile industry Cotton industry in England T Textile mills in England Textile mills in the United Kingdom . T T History of the textile industry in the United Kingdom