Tel Or on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Naharayim ( he, נַהֲרַיִים literally "Two rivers"), historically the Jisr Majami area ( ar, جسر المجامع literally "Meeting bridge" area), where the Yarmouk River flows into the

Naharayim ( he, נַהֲרַיִים literally "Two rivers"), historically the Jisr Majami area ( ar, جسر المجامع literally "Meeting bridge" area), where the Yarmouk River flows into the

Pinhas Rutenberg, a Russian-born Zionist and engineer

Pinhas Rutenberg, a Russian-born Zionist and engineer

A residential neighborhood was built near the plant to house employees. It was the only Jewish village in Transjordan at the time. It was designated for residence of the permanent employees of the power plant and their families, aiming to create an agricultural village at the Eastern border of the Land of Israel.

Employees of the power station also farmed thousands of dunams of land and sold some of the produce at a company workers’ supermarket in

A residential neighborhood was built near the plant to house employees. It was the only Jewish village in Transjordan at the time. It was designated for residence of the permanent employees of the power plant and their families, aiming to create an agricultural village at the Eastern border of the Land of Israel.

Employees of the power station also farmed thousands of dunams of land and sold some of the produce at a company workers’ supermarket in

On 27 April 1948, in violation of a November 1947 agreement between

On 27 April 1948, in violation of a November 1947 agreement between

Although the 1949 Israel-Jordan armistice agreement did not explicitly mention this region, the map attached to the agreement showed the armistice line cutting off a corner of Jordan between the two rivers (the present day Island of Peace). When Israel sent military forces into this corner in August 1950, Jordan filed a complaint with the

Although the 1949 Israel-Jordan armistice agreement did not explicitly mention this region, the map attached to the agreement showed the armistice line cutting off a corner of Jordan between the two rivers (the present day Island of Peace). When Israel sent military forces into this corner in August 1950, Jordan filed a complaint with the

On March 13, 1997, the

On March 13, 1997, the "With condolence visit to Israel, King Hussein spurs talks"

'' CNN'', March 16, 1997. Accessed July 22, 2007. "King Hussein of Jordan knelt in mourning Sunday with the families of seven Israeli schoolgirls gunned down last week by a Jordanian soldier, saying they were all 'members of one family.'" Daqamseh was tried by a Jordanian military tribunal, sentenced to twenty years in prison, and was released on 12 March 2017 after completing his sentence.

Naharayim ( he, נַהֲרַיִים literally "Two rivers"), historically the Jisr Majami area ( ar, جسر المجامع literally "Meeting bridge" area), where the Yarmouk River flows into the

Naharayim ( he, נַהֲרַיִים literally "Two rivers"), historically the Jisr Majami area ( ar, جسر المجامع literally "Meeting bridge" area), where the Yarmouk River flows into the Jordan River

The Jordan River or River Jordan ( ar, نَهْر الْأُرْدُنّ, ''Nahr al-ʾUrdunn'', he, נְהַר הַיַּרְדֵּן, ''Nəhar hayYardēn''; syc, ܢܗܪܐ ܕܝܘܪܕܢܢ ''Nahrāʾ Yurdnan''), also known as ''Nahr Al-Shariea ...

, was named by the Palestine Electric Company in a letter dated 27 February 1929 to Palestine Railways giving "proper names" to the "different quarters of our Jordan Works" one of these being the "works as a whole including the labour camp" to be called "Naharaim" and another being the site of the "Power House and the adjoining staff quarters, offices" to be called Tel Or ( he, תל אור - Hill of Light). Most of the plant was situated in the Emirate of Transjordan and stretched from the northern canal near the Ashdot Ya'akov

Ashdot Ya'akov ( he, אַשְׁדוֹת יַעֲקֹב, lit. ''Ya'akov Rapids'') is a kibbutz in northern Israel. Originally founded in 1924 by a kvutza of Hashomer members from Latvia on the land which is today Gesher, it moved to its current l ...

in Northern Mandatory Palestine

Mandatory Palestine ( ar, فلسطين الانتدابية '; he, פָּלֶשְׂתִּינָה (א״י) ', where "E.Y." indicates ''’Eretz Yiśrā’ēl'', the Land of Israel) was a geopolitical entity established between 1920 and 1948 ...

to the Jisr el-Majami

Jisr el-Majami or Jisr al-Mujamieh ( ar, جسر المجامع, Jisr al-Majami, Meeting Bridge or "The bridge of the place of assembling", and he, גֶּשֶׁר, ''Gesher'', lit. "Bridge") is an ancient stone bridge, possibly of Roman origin, o ...

in the south.

The area includes the disused "First Jordan Hydro-Electric Power House

The First Jordan Hydro-Electric Power House, also known as the Rutenberg Power Station or the Naharayim Power Plant or the Tel Or Power Plant, was a conventional dammed hydroelectric power station on the Jordan river, which operated between 19 ...

", constructed between 1927–33 in the area adjacent to the Roman bridge known as Jisr Majami

Jisr el-Majami or Jisr al-Mujamieh ( ar, جسر المجامع, Jisr al-Majami, Meeting Bridge or "The bridge of the place of assembling", and he, גֶּשֶׁר, ''Gesher'', lit. "Bridge") is an ancient stone bridge, possibly of Roman origin, o ...

. The plant, established by Pinhas Rutenberg

Pinhas Rutenberg (russian: Пётр Моисеевич Рутенберг, Pyotr Moiseyevich Rutenberg; he, פנחס רוטנברג: 5 February 1879 – 3 January 1942) was a Russian Jewish engineer, businessman, and political activist. He pla ...

, produced much of the energy consumed in Mandatory Palestine

Mandatory Palestine ( ar, فلسطين الانتدابية '; he, פָּלֶשְׂתִּינָה (א״י) ', where "E.Y." indicates ''’Eretz Yiśrā’ēl'', the Land of Israel) was a geopolitical entity established between 1920 and 1948 ...

until the 1948 Palestine war

The 1948 Palestine war was fought in the territory of what had been, at the start of the war, British-ruled Mandatory Palestine. It is known in Israel as the War of Independence ( he, מלחמת העצמאות, ''Milkhemet Ha'Atzma'ut'') and ...

. The channels and dams built for the power plant, together with the two rivers, formed a man-made island. The residential area is known today as Qaryet Jisr Al-Majame ( ar, قرية جسر المجامع - Community Bridge Village).

The 1994 Israel–Jordan peace treaty recognized part of the area – known as the Naharayim/Baqura Area in the treaty or, according to the map annexed to the treaty and authenticated by both Israel and Jordan, the Baqura/Naharayim area – to be under Jordanian sovereignty, but leased Israeli landowners freedom of entry. The 25-year renewable lease ended in 2019. The Jordanian government announced its intention to end the lease; the treaty gives Jordan the right to do so only on one condition – that one year prior notice is given, which coincided with the announcement in October 2018. Jordan reclaimed Al-Baqoura in November 2019 after a one-year notice of termination submitted by the Jordanian government

The politics of Jordan takes place in a framework of a parliamentary monarchy, whereby the Prime Minister of Jordan is head of government, and of a multi-party system. Jordan is a constitutional monarchy based on the constitution promulgated on ...

.

History

Jisr al Majami

Historically the only structure in the area was the Roman bridge ofJisr Majami

Jisr el-Majami or Jisr al-Mujamieh ( ar, جسر المجامع, Jisr al-Majami, Meeting Bridge or "The bridge of the place of assembling", and he, גֶּשֶׁר, ''Gesher'', lit. "Bridge") is an ancient stone bridge, possibly of Roman origin, o ...

. A railway bridge was built parallel to it in the early 20th century to carry to Jezreel Valley railway, opened in 1905. The bridge played a strategic role in World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

; it was captured by the 19th Lancers during the Capture of Afulah and Beisan

The Capture of Afula and Beisan occurred on 20 September 1918, during the Battle of Sharon which together with the Nablus, formed the set piece Battle of Megiddo fought during the last months of the Sinai and Palestine Campaign of the First W ...

. When the Rutenberg concession was given, it was defined as the area around Jisr Majami.

Hydroelectric power station

Pinhas Rutenberg, a Russian-born Zionist and engineer

Pinhas Rutenberg, a Russian-born Zionist and engineer immigrated

Immigration is the international movement of people to a destination country of which they are not natives or where they do not possess citizenship in order to settle as permanent residents or naturalized citizens. Commuters, tourists, and ...

to Palestine in 1919. After submitting a plan to the Zionist movement for the establishment of 13 hydroelectric power stations and securing financing for the plan, he was awarded a concession from the British Mandatory government to generate electricity, first from the Yarkon River

The Yarkon River, also Yarqon River or Jarkon River ( he, נחל הירקון, ''Nahal HaYarkon'', ar, نهر العوجا, ''Nahr al-Auja''), is a river in central Israel. The source of the Yarkon ("Greenish" in Hebrew) is at Tel Afek (Antip ...

near Tel Aviv

Tel Aviv-Yafo ( he, תֵּל־אָבִיב-יָפוֹ, translit=Tēl-ʾĀvīv-Yāfō ; ar, تَلّ أَبِيب – يَافَا, translit=Tall ʾAbīb-Yāfā, links=no), often referred to as just Tel Aviv, is the most populous city in the G ...

, and shortly thereafter, utilizing all the running water in western Palestine.

Naharayim is part of 6,000 dunams (600 ha) sold to the Palestine Electric Corporation (PEC) run by Pinhas Rutenberg.

The Naharayim site was chosen for the strong water flow and the possibility of regulating the flow through storage in the Sea of Galilee

The Sea of Galilee ( he, יָם כִּנֶּרֶת, Judeo-Aramaic: יַמּא דטבריא, גִּנֵּיסַר, ar, بحيرة طبريا), also called Lake Tiberias, Kinneret or Kinnereth, is a freshwater lake in Israel. It is the lowest ...

during the winter rainy season and release of the water reserves in the summer. Construction began in 1927 and continued for five years, providing employment for 3,000 workers. The site was named Naharayim, Hebrew for "Two Rivers."

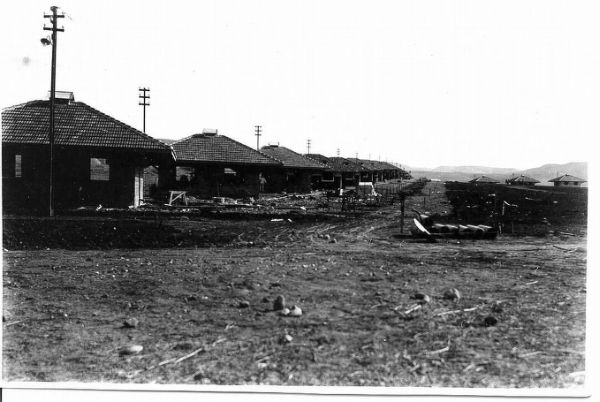

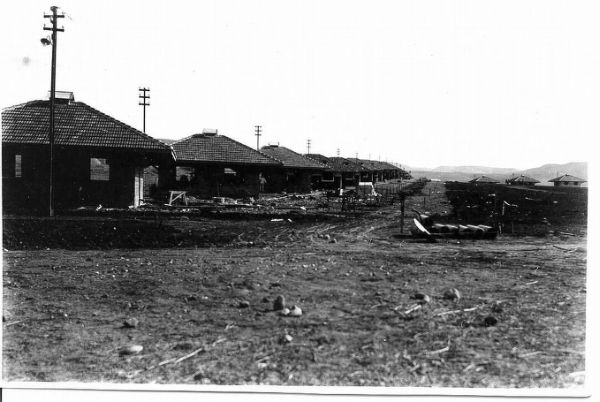

Workers' village

A residential neighborhood was built near the plant to house employees. It was the only Jewish village in Transjordan at the time. It was designated for residence of the permanent employees of the power plant and their families, aiming to create an agricultural village at the Eastern border of the Land of Israel.

Employees of the power station also farmed thousands of dunams of land and sold some of the produce at a company workers’ supermarket in

A residential neighborhood was built near the plant to house employees. It was the only Jewish village in Transjordan at the time. It was designated for residence of the permanent employees of the power plant and their families, aiming to create an agricultural village at the Eastern border of the Land of Israel.

Employees of the power station also farmed thousands of dunams of land and sold some of the produce at a company workers’ supermarket in Haifa

Haifa ( he, חֵיפָה ' ; ar, حَيْفَا ') is the third-largest city in Israel—after Jerusalem and Tel Aviv—with a population of in . The city of Haifa forms part of the Haifa metropolitan area, the third-most populous metropol ...

. Due to its relative isolation and despite the limited number of resident families, the village included a clinic, a kindergarten, and even a school, established by Yosef Hanani for the children of employees.

The families of the employees at Tel Or were evacuated from the settlement in April 1948, leaving behind only workers with Jordanian ID cards. Following a prolonged battle between Palestinian Jewish forces and the Transjordanian Arab Legion in the area, the remaining residents of Tel Or were given an ultimatum to surrender or leave the village. Tel Or was abandoned by the residents, who were evacuated to Jewish-controlled areas across the river.

During the 1948 War, 70 Palestinian Arab families from a village just meters away on the Palestinian side of the Jordan River populated the abandoned site.

1947/8 diplomacy

In the lead up to theEnd of the British Mandate for Palestine

The end of the British Mandate for Palestine was formally made by way of the Palestine bill of 29 April 1948. A public statement prepared by the Colonial and Foreign offices confirmed termination of British responsibility for the administration o ...

and Israeli independence, Naharayim was the venue for a meeting between Golda Meir

Golda Meir, ; ar, جولدا مائير, Jūldā Māʾīr., group=nb (born Golda Mabovitch; 3 May 1898 – 8 December 1978) was an Israeli politician, teacher, and '' kibbutznikit'' who served as the fourth prime minister of Israel from 1969 to ...

and King Abdullah on 17 November 1947. There was a second meeting in Amman on 10 May 1948, after the Gesher incident (see below), in an attempt by the Jewish leadership to head off Jordanian participation in the war.

1948 war

On 27 April 1948, in violation of a November 1947 agreement between

On 27 April 1948, in violation of a November 1947 agreement between Golda Meir

Golda Meir, ; ar, جولدا مائير, Jūldā Māʾīr., group=nb (born Golda Mabovitch; 3 May 1898 – 8 December 1978) was an Israeli politician, teacher, and '' kibbutznikit'' who served as the fourth prime minister of Israel from 1969 to ...

and King Abdullah, the Arab Legion

The Arab Legion () was the police force, then regular army of the Emirate of Transjordan, a British protectorate, in the early part of the 20th century, and then of independent Jordan, with a final Arabization of its command taking place in 1 ...

's 4th Battalion launched a mortar and artillery attack on the Naharayim police fort and Kibbutz

A kibbutz ( he, קִבּוּץ / , lit. "gathering, clustering"; plural: kibbutzim / ) is an intentional community in Israel that was traditionally based on agriculture. The first kibbutz, established in 1909, was Degania. Today, farming h ...

Gesher (on the Palestinian side of the border). On the evening of 27 April, the Legion began shelling the fort and kibbutz, stepping up the attack the following day. Many of the kibbutz buildings were destroyed.

On the morning of April 29, a Legion officer demanded the evacuation of the fort, but was turned down. After protests to the British Mandate administration, the shelling was halted, and Abdullah was reprimanded for "aggression against Palestine territory." Although the attack did constitute a violation of the understanding, a British officer of the Legion claimed afterwards that it was an unfortunate local misunderstanding. The impetus for the attack was the seizure by the settlers of the police fortress which the British had invited Glubb Pasha to take over. The settlement would have fallen except that Abdullah told his son Talal to halt the attack. In the wake of the attack 50 children of the kibbutz were evacuated, first to the Ravitz Hotel on the Carmel, and then to a 19th-century French monastery on the grounds of Rambam Hospital

Rambam Health Care Campus ( he, רמב"ם - הקריה הרפואית לבריאות האדם) commonly called Rambam Hospital, is a teaching hospital in the Bat Galim neighborhood of Haifa, Israel founded in 1938, 10 years before the establishme ...

in the Bat Galim

Bat Galim ( he, בת גלים, ''lit.'' Daughter of the Waves) is a neighborhood of Haifa, Israel, located at the foot of Mount Carmel on the Mediterranean coast. Bat Galim is known for its promenade and sandy beaches. The neighborhood spans from ...

neighborhood of Haifa

Haifa ( he, חֵיפָה ' ; ar, حَيْفَا ') is the third-largest city in Israel—after Jerusalem and Tel Aviv—with a population of in . The city of Haifa forms part of the Haifa metropolitan area, the third-most populous metropol ...

, where they lived for the next 22 months.

An Iraqi brigade invaded at Naharayim on May 15, 1948, in an unsuccessful attempt to take the kibbutz and fort. The power plant was occupied and looted by the Iraqi forces.

To prevent Iraqi tanks from attacking Jewish villages in the Jordan Valley, the sluice gates of the Degania dam were opened. The rush of water, which deepened the river at this spot, was instrumental in blocking the Iraqi-Jordanian incursion.

1949 armistice line

Although the 1949 Israel-Jordan armistice agreement did not explicitly mention this region, the map attached to the agreement showed the armistice line cutting off a corner of Jordan between the two rivers (the present day Island of Peace). When Israel sent military forces into this corner in August 1950, Jordan filed a complaint with the

Although the 1949 Israel-Jordan armistice agreement did not explicitly mention this region, the map attached to the agreement showed the armistice line cutting off a corner of Jordan between the two rivers (the present day Island of Peace). When Israel sent military forces into this corner in August 1950, Jordan filed a complaint with the United Nations Security Council

The United Nations Security Council (UNSC) is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN) and is charged with ensuring international peace and security, recommending the admission of new UN members to the General Assembly, ...

.Letter dated 21 September 1950 from the Minister for Foreign Affairs of the Hashimite Kingdom of the Jordan addressed to the Secretary-General concerning the Palestine question, UNSC document S/1824. According to Jordan, the map had been improperly altered from the original agreed by the parties, was inadequately signed, and in any case the armistice agreement was never intended to alter the territory of Jordan. Israel responded that it was immaterial how the map came to be how it was, as only the final version was binding. The Security Council then questioned Ralph Bunche

Ralph Johnson Bunche (; August 7, 1904 – December 9, 1971) was an American political scientist, diplomat, and leading actor in the mid-20th-century decolonization process and US civil rights movement, who received the 1950 Nobel Peace Prize ...

, who had been the UN mediator at the armistice negotiations at Rhodes

Rhodes (; el, Ρόδος , translit=Ródos ) is the largest and the historical capital of the Dodecanese islands of Greece. Administratively, the island forms a separate municipality within the Rhodes regional unit, which is part of the S ...

.United Nations Security Council, 518th Meeting, 6 November 1950, ''Proces-Verbaux'' No. 60, document number S/PV.518. He said that the parties had brought map overlays to Rhodes from earlier informal negotiations and they were transferred manually onto a 1:250,000 map (shown right). He could not explain why a part of Jordan had been cut off and was sure it had not been brought up in the formal meetings. However, his opinion was that although the region remained sovereign Jordanian territory it was on the Israeli side of the armistice line because the map was an integral part of the agreement which both parties had signed.

Peace treaty and property rights

Two kibbutzim,Ashdot Ya'akov Meuhad

Ashdot Ya'akov Meuhad ( he, אַשְׁדוֹת יַעֲקֹב מְאֻחָד) is a kibbutz in northern Israel. Located to the south of the Sea of Galilee near the Jordanian border and covering 4,300 dunams, it falls under the jurisdiction of Emek H ...

and Ashdot Ya'akov Ihud

Ashdot Ya'akov Ihud ( he, אַשְׁדוֹת יַעֲקֹב אִחוּד) is a kibbutz in northern Israel. Located to the south of the Sea of Galilee near the Jordanian border and covering 4,200 dunams, it falls under the jurisdiction of Emek HaYar ...

, worked some 820 dunams (82 ha) on an island (present day Island of Peace) that was part of PEC land, which was in Israeli hands following the signing of the 1949 armistice agreement. The bulk of the 6,000 dunams, including the destroyed plant, remained in Jordanian hands and were placed under the Guardian of Enemy Property. In the 1994 Israel–Jordan peace treaty, Jordanian sovereignty over the 820 dunam area was confirmed, but Israelis retained private land ownership and special provisions allow free Israeli travel and protect Israeli property rights.

The Jordanian King Abdullah II said that as of Sunday, 10 November 2019, Israeli farmers will not be able to access the lands without a visa after the lease ended.

Peace park

The remains of the power station are part of the Jordan River Peace Park south of the Island of Peace on the Israel-Jordan border. The project is spearheaded by the trilateral NGO EcoPeace Middle East, headquartered in Tel Aviv,Bethlehem

Bethlehem (; ar, بيت لحم ; he, בֵּית לֶחֶם '' '') is a city in the central West Bank, Palestine, about south of Jerusalem. Its population is approximately 25,000,Amara, 1999p. 18.Brynen, 2000p. 202. and it is the capital ...

and Amman

Amman (; ar, عَمَّان, ' ; Ammonite: 𐤓𐤁𐤕 𐤏𐤌𐤍 ''Rabat ʻAmān'') is the capital and largest city of Jordan, and the country's economic, political, and cultural center. With a population of 4,061,150 as of 2021, Amman is ...

.

1997 massacre

AMIT

Amit is a male given name of Indian or Hebrew origin.

In Hindi, Amit ( hi, अमित, means "infinite" or "boundless", bn, অমিত) originates from the Sanskrit word ' (अमित:), ' (अमित:) essentially is the negation of ' ...

Fuerst (Fürst) Zionist religious junior high school

A middle school (also known as intermediate school, junior high school, junior secondary school, or lower secondary school) is an educational stage which exists in some countries, providing education between primary school and secondary school. ...

from Beit Shemesh

Beit Shemesh ( he, בֵּית שֶׁמֶשׁ ) is a city located approximately west of Jerusalem in Israel's Jerusalem District, with a population of in .

History Tel Beit Shemesh

The small archaeological tell northeast of the modern city w ...

was on a class trip to the Jordan Valley, and Island of Peace. Jordanian soldier Ahmed Daqamseh opened fire at the schoolchildren, killing seven girls aged 13 or 14 and badly wounding six others. King Hussein

Hussein bin Talal ( ar, الحسين بن طلال, ''Al-Ḥusayn ibn Ṭalāl''; 14 November 1935 – 7 February 1999) was King of Jordan from 11 August 1952 until his death in 1999. As a member of the Hashemite dynasty, the royal family o ...

of Jordan

Jordan ( ar, الأردن; tr. ' ), officially the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan,; tr. ' is a country in Western Asia. It is situated at the crossroads of Asia, Africa, and Europe, within the Levant region, on the East Bank of the Jordan Rive ...

came to Beit Shemesh to extend his condolences and ask forgiveness in the name of his country, a step which was seen as both touching and courageous.'' CNN'', March 16, 1997. Accessed July 22, 2007. "King Hussein of Jordan knelt in mourning Sunday with the families of seven Israeli schoolgirls gunned down last week by a Jordanian soldier, saying they were all 'members of one family.'"

See also

* Island of PeaceReferences

{{coord, 32, 38, 39.83, N, 35, 34, 22.26, E, display=title Buildings and structures completed in 1930 Former hydroelectric power stations Power stations in Israel Power stations in Jordan Jordan River Populated places established in 1930 Geography of Jordan Jewish villages depopulated during the 1948 Arab–Israeli War 1930s establishments in Transjordan 1940s disestablishments in Jordan Jews and Judaism in Jordan