Tacoma Narrows Bridge (1940) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The 1940 Tacoma Narrows Bridge, the first Tacoma Narrows Bridge, was a

The 1940 Tacoma Narrows Bridge, the first Tacoma Narrows Bridge, was a

However, "Eastern consulting engineers" — by which Eldridge meant

However, "Eastern consulting engineers" — by which Eldridge meant

Leonard Coatsworth, an editor at ''

Leonard Coatsworth, an editor at ''

The original Tacoma Narrows Bridge was the first to be built with girders of

The original Tacoma Narrows Bridge was the first to be built with girders of

The bridge's spectacular destruction is often used as an object lesson in the necessity to consider both

The bridge's spectacular destruction is often used as an object lesson in the necessity to consider both

The underwater remains of the highway deck of the old suspension bridge act as a large artificial reef, and these are listed on the

The underwater remains of the highway deck of the old suspension bridge act as a large artificial reef, and these are listed on the

The Tacoma Narrows Bridge Disaster, November 1940

at University of Bristol

Tacoma Narrows Bridge Failure

at Carleton University

at the Gig Harbor Peninsula Historical Society & Museum

at Ketchum.org {{Authority control

The 1940 Tacoma Narrows Bridge, the first Tacoma Narrows Bridge, was a

The 1940 Tacoma Narrows Bridge, the first Tacoma Narrows Bridge, was a suspension bridge

A suspension bridge is a type of bridge in which the deck is hung below suspension cables on vertical suspenders. The first modern examples of this type of bridge were built in the early 1800s. Simple suspension bridges, which lack vertical ...

in the U.S. state of Washington

Washington commonly refers to:

* Washington (state), United States

* Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States

** A metonym for the federal government of the United States

** Washington metropolitan area, the metropolitan area centered o ...

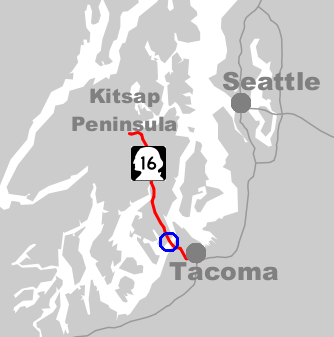

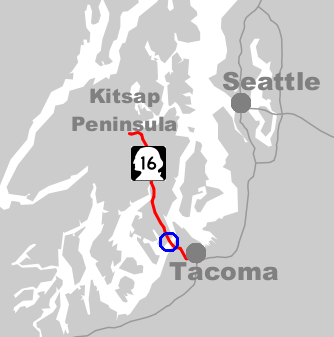

that spanned the Tacoma Narrows

The Tacoma Narrows (or the Narrows), a strait, is part of Puget Sound in the U.S. state of Washington. A navigable maritime waterway between glacial landforms, the Narrows separates the Kitsap Peninsula from the city of Tacoma.

The Narrows i ...

strait

A strait is an oceanic landform connecting two seas or two other large areas of water. The surface water generally flows at the same elevation on both sides and through the strait in either direction. Most commonly, it is a narrow ocean chan ...

of Puget Sound

Puget Sound ( ) is a sound of the Pacific Northwest, an inlet of the Pacific Ocean, and part of the Salish Sea. It is located along the northwestern coast of the U.S. state of Washington. It is a complex estuarine system of interconnected m ...

between Tacoma and the Kitsap Peninsula

The Kitsap Peninsula () lies west of Seattle across Puget Sound, in Washington state in the Pacific Northwest. Hood Canal separates the peninsula from the Olympic Peninsula on its west side. The peninsula, a.k.a. "Kitsap", encompasses all of Kit ...

. It opened to traffic on July 1, 1940, and dramatically collapsed into Puget Sound on November 7 of the same year. The bridge's collapse has been described as "spectacular" and in subsequent decades "has attracted the attention of engineers, physicists, and mathematicians". Throughout its short existence, it was the world's third-longest suspension bridge by main span, behind the Golden Gate Bridge

The Golden Gate Bridge is a suspension bridge spanning the Golden Gate, the strait connecting San Francisco Bay and the Pacific Ocean. The structure links the U.S. city of San Francisco, California—the northern tip of the San Francisco Pen ...

and the George Washington Bridge

The George Washington Bridge is a double-decked suspension bridge spanning the Hudson River, connecting Fort Lee, New Jersey, with Manhattan in New York City. The bridge is named after George Washington, the first president of the United S ...

.

Construction began in September 1938. From the time the deck was built, it began to move vertically in windy conditions, so construction workers nicknamed the bridge Galloping Gertie. The motion continued after the bridge opened to the public, despite several damping

Damping is an influence within or upon an oscillatory system that has the effect of reducing or preventing its oscillation. In physical systems, damping is produced by processes that dissipate the energy stored in the oscillation. Examples i ...

measures. The bridge's main span finally collapsed in winds on the morning of November 7, 1940, as the deck oscillated in an alternating twisting motion that gradually increased in amplitude until the deck tore apart.

The portions of the bridge still standing after the collapse, including the towers and cables, were dismantled and sold as scrap metal. Efforts to replace the bridge were delayed by the United States' entry into World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

, but in 1950, a new Tacoma Narrows Bridge opened in the same location, using the original bridge's tower pedestals and cable anchorages. The portion of the bridge that fell into the water now serves as an artificial reef

An artificial reef is a human-created underwater structure, typically built to promote marine life in areas with a generally featureless bottom, to control erosion, block ship passage, block the use of trawling nets, or improve surfing.

Many ...

.

The bridge's collapse had a lasting effect on science and engineering. In many physics

Physics is the natural science that studies matter, its fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge which ...

textbooks, the event is presented as an example of elementary forced mechanical resonance

Mechanical resonance is the tendency of a mechanical system to respond at greater amplitude when the frequency of its oscillations matches the system's natural frequency of vibration (its '' resonance frequency'' or ''resonant frequency'') close ...

, but it was more complicated in reality; the bridge collapsed because moderate winds produced aeroelastic flutter

Aeroelasticity is the branch of physics and engineering studying the interactions between the inertial, elastic, and aerodynamic forces occurring while an elastic body is exposed to a fluid flow. The study of aeroelasticity may be broadly classif ...

that was self-exciting and unbounded: For any constant sustained wind speed above about , the amplitude of the (torsion

Torsion may refer to:

Science

* Torsion (mechanics), the twisting of an object due to an applied torque

* Torsion of spacetime, the field used in Einstein–Cartan theory and

** Alternatives to general relativity

* Torsion angle, in chemistry

Bi ...

al) flutter oscillation would continuously increase, with a negative damping factor, i.e., a reinforcing effect, opposite to damping. The collapse boosted research into bridge aerodynamics

Aerodynamics, from grc, ἀήρ ''aero'' (air) + grc, δυναμική (dynamics), is the study of the motion of air, particularly when affected by a solid object, such as an airplane wing. It involves topics covered in the field of fluid dy ...

- aeroelastics, which has influenced the designs of all later long-span bridges.

Design and construction

Proposals for a bridge between Tacoma and the Kitsap Peninsula date at least to theNorthern Pacific Railway

The Northern Pacific Railway was a transcontinental railroad that operated across the northern tier of the western United States, from Minnesota to the Pacific Northwest. It was approved by Congress in 1864 and given nearly of land grants, wh ...

's 1889 trestle

ATLAS-I (Air Force Weapons Lab Transmission-Line Aircraft Simulator), better known as Trestle, was a unique electromagnetic pulse (EMP) generation and testing apparatus built between 1972 and 1980 during the Cold War at Sandia National Laborato ...

proposal, but concerted efforts began in the mid-1920s. The Tacoma Chamber of Commerce began campaigning and funding studies in 1923. Several noted bridge engineers were consulted, including Joseph B. Strauss, who went on to be chief engineer of the Golden Gate Bridge

The Golden Gate Bridge is a suspension bridge spanning the Golden Gate, the strait connecting San Francisco Bay and the Pacific Ocean. The structure links the U.S. city of San Francisco, California—the northern tip of the San Francisco Pen ...

, and David B. Steinman

David Barnard Steinman (June 11, 1886 – August 21, 1960) was an American civil engineer. He was the designer of the Mackinac Bridge and many other notable bridges, and a published author. He grew up in New York City's lower Manhattan, a ...

, later the designer of the Mackinac Bridge

The Mackinac Bridge ( ) is a suspension bridge spanning the Straits of Mackinac, connecting the Upper and Lower peninsulas of the U.S. state of Michigan. Opened in 1957, the bridge (familiarly known as "Big Mac" and "Mighty Mac") is the worl ...

. Steinman made several Chamber-funded visits and presented a preliminary proposal in 1929, but by 1931 the Chamber had canceled the agreement on the grounds that Steinman was not working hard enough to obtain financing. At the 1938 meeting of the structural division of the American Society of Civil Engineers, during construction of the bridge, with its designer in the audience, Steinman predicted its failure.

In 1937, the Washington State legislature created the Washington State Toll Bridge Authority and appropriated $5,000 (equivalent to $ today) to study the request by Tacoma and Pierce County for a bridge over the Narrows.

From the start, financing of the bridge was a problem: Revenue from the proposed tolls would not be enough to cover construction costs; another expense was buying out the ferry contract from a private firm running services on the Narrows at the time. Nonetheless, there was strong support for the bridge from the United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

, which operated the Puget Sound Naval Shipyard

Puget Sound Naval Shipyard, officially Puget Sound Naval Shipyard and Intermediate Maintenance Facility (PSNS & IMF), is a United States Navy shipyard covering 179 acres (0.7 km2) on Puget Sound at Bremerton, Washington in uninterrupted ...

in Bremerton

Bremerton is a city in Kitsap County, Washington. The population was 37,729 at the 2010 census and an estimated 41,405 in 2019, making it the largest city on the Kitsap Peninsula. Bremerton is home to Puget Sound Naval Shipyard and the Bremer ...

, and from the United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, ...

, which ran McChord Field

McChord Field is a United States Air Force base in the northwest United States, in Pierce County, Washington. South of Tacoma, McChord Field is the home of the 62d Airlift Wing, Air Mobility Command, the field's primary mission being worldw ...

and Fort Lewis near Tacoma.

Washington State engineer Clark Eldridge produced a preliminary tried-and-true conventional suspension bridge design, and the Washington State Toll Bridge Authority requested $11 million (equivalent to $ million today) from the federal Public Works Administration

The Public Works Administration (PWA), part of the New Deal of 1933, was a large-scale public works construction agency in the United States headed by Secretary of the Interior Harold L. Ickes. It was created by the National Industrial Reco ...

(PWA). Preliminary construction plans by the Washington Department of Highways had called for a set of truss

A truss is an assembly of ''members'' such as beams, connected by ''nodes'', that creates a rigid structure.

In engineering, a truss is a structure that "consists of two-force members only, where the members are organized so that the assembl ...

es to sit beneath the roadway and stiffen it.

However, "Eastern consulting engineers" — by which Eldridge meant

However, "Eastern consulting engineers" — by which Eldridge meant Leon Moisseiff

Leon Solomon Moisseiff (November 10, 1872 – September 3, 1943) was a leading suspension bridge engineer in the United States in the 1920s and 1930s. He was awarded The Franklin Institute's Louis E. Levy Medal in 1933.

His developments of the ...

, the noted New York bridge engineer who served as designer and consultant engineer for the Golden Gate Bridge — petitioned the PWA and the Reconstruction Finance Corporation The Reconstruction Finance Corporation was a government corporation administered by the United States Federal Government between 1932 and 1957 that provided financial support to state and local governments and made loans to banks, railroads, mortga ...

(RFC) to build the bridge for less. Moisseiff and Frederick Lienhard, the latter an engineer with what was then known in New York as the Port Authority

In Canada and the United States, a port authority (less commonly a port district) is a governmental or quasi-governmental public authority_for_a_special-purpose_district.html" ;"title="110. - 6910./ref> is a type of Nonprofit organization">nonprof ...

, had published a paper that was probably the most important theoretical advance in the bridge engineering field of the decade. Their theory of elastic distribution extended the deflection

Deflection or deflexion may refer to:

Board games

* Deflection (chess), a tactic that forces an opposing chess piece to leave a square

* Khet (game), formerly ''Deflexion'', an Egyptian-themed chess-like game using lasers

Mechanics

* Deflection ...

theory that was originally devised by the Austrian engineer Josef Melan

Josef Melan (1854–1941) was an Austrian engineer. He is regarded as one of the most important pioneers of reinforced concrete bridge-building at the end of the 19th century. Josef Melan is credited as the inventor of the ''Melan System'', a me ...

to horizontal bending under static wind load. They showed that the stiffness of the main cables (via the suspenders) would absorb up to one-half of the static wind pressure pushing a suspended structure

A suspended structure is a structure which is supported by cables coming from beams or trusses which sit atop a concrete center column or core. The design allows the walls, roof and cantilevered floors to be supported entirely by cables and a cen ...

laterally. This energy would then be transmitted to the anchorages and towers. Using this theory, Moisseiff argued for stiffening the bridge with a set of plate girders rather than the trusses proposed by the Washington State Toll Bridge Authority. This approach meant a slimmer, more elegant design, and also reduced the construction costs as compared with the Highway Department's design proposed by Eldridge. Moisseiff's design won out, inasmuch as the other proposal was considered to be too expensive. On June 23, 1938, the PWA approved nearly $6 million (equivalent to $ million today) for the Tacoma Narrows Bridge. Another $1.6 million ($ million today) was to be collected from tolls to cover the estimated total $8 million cost ($ million today).

Following Moisseiff's design, bridge construction began on September 27, 1938. Construction took only nineteen months, at a cost of $6.4 million ($ million today), which was financed by the grant from the PWA and a loan from the RFC.

The Tacoma Narrows Bridge, with a main span of , was the third-longest suspension bridge in the world at that time, following the George Washington Bridge

The George Washington Bridge is a double-decked suspension bridge spanning the Hudson River, connecting Fort Lee, New Jersey, with Manhattan in New York City. The bridge is named after George Washington, the first president of the United S ...

between New Jersey

New Jersey is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern regions of the United States. It is bordered on the north and east by the state of New York; on the east, southeast, and south by the Atlantic Ocean; on the west by the Delawa ...

and New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

, and the Golden Gate Bridge, connecting San Francisco

San Francisco (; Spanish for " Saint Francis"), officially the City and County of San Francisco, is the commercial, financial, and cultural center of Northern California. The city proper is the fourth most populous in California and 17t ...

with Marin County

Marin County is a county located in the northwestern part of the San Francisco Bay Area of the U.S. state of California. As of the 2020 census, the population was 262,231. Its county seat and largest city is San Rafael. Marin County is acros ...

to its north.

Because planners expected fairly light traffic volumes, the bridge was designed with two lanes, and it was just wide. This was quite narrow, especially in comparison with its length. With only the plate girders providing additional depth, the bridge's roadway section was also shallow.

The decision to use such shallow and narrow girders proved the bridge's undoing. With such minimal girders, the deck of the bridge was insufficiently rigid and was easily moved about by winds; from the start, the bridge became infamous for its movement. A mild to moderate wind could cause alternate halves of the center span

Span may refer to:

Science, technology and engineering

* Span (unit), the width of a human hand

* Span (engineering), a section between two intermediate supports

* Wingspan, the distance between the wingtips of a bird or aircraft

* Sorbitan ester ...

to visibly rise and fall several feet over four- to five-second intervals. This flexibility was experienced by the builders and workmen during construction, which led some of the workers to christen the bridge "Galloping Gertie". The nickname soon stuck, and even the public (when the toll-paid traffic started) felt these motions on the day that the bridge opened on July 1, 1940.

Attempt to control structural vibration

Since the structure experienced considerable verticaloscillation

Oscillation is the repetitive or periodic variation, typically in time, of some measure about a central value (often a point of equilibrium) or between two or more different states. Familiar examples of oscillation include a swinging pendul ...

s while it was still under construction, several strategies were used to reduce the motion of the bridge. They included

* attachment of tie-down cables to the plate girders, which were anchored to 50-ton concrete

Concrete is a composite material composed of fine and coarse aggregate bonded together with a fluid cement (cement paste) that hardens (cures) over time. Concrete is the second-most-used substance in the world after water, and is the most wid ...

blocks on the shore. This measure proved ineffective, as the cables snapped shortly after installation.

* addition of a pair of inclined cable stays that connected the main cables to the bridge deck at mid-span. These remained in place until the collapse, but were also ineffective at reducing the oscillations.

* finally, the structure was equipped with hydraulic buffers installed between the towers and the floor system of the deck to damp longitudinal motion of the main span. The effectiveness of the hydraulic dampers was nullified, however, because the seals of the units were damaged when the bridge was sand-blasted before being painted.

The Washington State Toll Bridge Authority hired Professor Frederick Burt Farquharson, an engineering professor at the University of Washington

The University of Washington (UW, simply Washington, or informally U-Dub) is a public research university in Seattle, Washington.

Founded in 1861, Washington is one of the oldest universities on the West Coast; it was established in Seatt ...

, to make wind tunnel

Wind tunnels are large tubes with air blowing through them which are used to replicate the interaction between air and an object flying through the air or moving along the ground. Researchers use wind tunnels to learn more about how an aircraft ...

tests and recommend solutions in order to reduce the oscillations of the bridge. Professor Farquharson and his students built a 1:200-scale model of the bridge and a 1:20-scale model of a section of the deck. The first studies concluded on November 2, 1940—five days before the bridge collapse on November 7. He proposed two solutions:

* To drill holes in the lateral girders and along the deck so that the air flow could circulate through them (in this way reducing lift forces).

* To give a more aerodynamic

Aerodynamics, from grc, ἀήρ ''aero'' (air) + grc, δυναμική (dynamics), is the study of the motion of air, particularly when affected by a solid object, such as an airplane wing. It involves topics covered in the field of fluid dyn ...

shape to the transverse section of the deck by adding fairings or deflector vanes along the deck, attached to the girder fascia.

The first option was not favored, because of its irreversible nature. The second option was the chosen one, but it was not carried out, because the bridge collapsed five days after the studies were concluded.

Collapse

Leonard Coatsworth, an editor at ''

Leonard Coatsworth, an editor at ''The News Tribune

''The News Tribune'' is an American daily newspaper based in Tacoma, Washington. It is the second-largest daily newspaper in the state of Washington with a weekday circulation of 30,945 in 2020. With origins dating back to 1883, the newspaper w ...

'' in Tacoma, was the last person to drive on the bridge:

Tubby, Coatsworth's Cocker Spaniel

Cocker Spaniels are dogs belonging to two breeds of the spaniel dog type: the American Cocker Spaniel and the English Cocker Spaniel of which are commonly called simply Cocker Spaniel in their countries of origin. In the early 20th century, Cock ...

, was the only fatality of the Tacoma Narrows Bridge disaster; he was lost along with Coatsworth's car. Professor Farquharson and a news photographer attempted to rescue Tubby during a lull, but the dog was too terrified to leave the car and bit one of the rescuers. Tubby died when the bridge fell and neither his body nor the car was ever recovered. Coatsworth had been driving Tubby back to his daughter, who owned the dog. Coatsworth received $450.00 for his car (equivalent to $ today) and $364.40 ($ today) in reimbursement for the contents of his car, including Tubby.

Inquiry

Theodore von Kármán

Theodore von Kármán ( hu, ( szőllőskislaki) Kármán Tódor ; born Tivadar Mihály Kármán; 11 May 18816 May 1963) was a Hungarian-American mathematician, aerospace engineer, and physicist who was active primarily in the fields of aeronaut ...

, the director of the Guggenheim Aeronautical Laboratory and a world-renowned aerodynamicist, was a member of the board of inquiry into the collapse. He reported that the State of Washington was unable to collect on one of the insurance

Insurance is a means of protection from financial loss in which, in exchange for a fee, a party agrees to compensate another party in the event of a certain loss, damage, or injury. It is a form of risk management, primarily used to hedge ...

policies for the bridge because its insurance agent had fraudulently pocketed the insurance premiums. The agent, Hallett R. French, who represented the Merchant's Fire Assurance Company, was charged and tried for grand larceny for withholding the premiums for $800,000 worth of insurance (equivalent to $ million today). The bridge was insured by many other policies that covered 80% of the $5.2 million structure's value (equivalent to $ million today). Most of these were collected without incident.

On November 28, 1940, the U.S. Navy's Hydrographic Office reported that the remains of the bridge were located at geographical coordinates

The geographic coordinate system (GCS) is a spherical or ellipsoidal coordinate system for measuring and communicating positions directly on the Earth as latitude and longitude. It is the simplest, oldest and most widely used of the vario ...

, at a depth of 180 feet (55 meters).

Film of collapse

At least four people captured the collapse of the bridge. The collapse of the bridge was recorded on film separately by Barney Elliott and by Harbine Monroe, owners of The Camera Shop in Tacoma. The film shows Leonard Coatsworth attempting to rescue his dog — without success — and then leaving the bridge. The film was subsequently sold to Paramount Studios, which duplicated it for newsreels in black-and-white and distributed it worldwide to movie theaters.Castle Films

Castle Films was a film company founded in California by former newsreel cameraman Eugene W. Castle (1897–1960) in 1924. Originally, Castle Films produced industrial and advertising films. Then in 1937, the company pioneered the production and d ...

also received distribution rights for 8 mm home video. In 1998, ''The Tacoma Narrows Bridge Collapse'' was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry

The National Film Registry (NFR) is the United States National Film Preservation Board's (NFPB) collection of films selected for preservation, each selected for its historical, cultural and aesthetic contributions since the NFPB’s inception ...

by the Library of Congress

The Library of Congress (LOC) is the research library that officially serves the United States Congress and is the ''de facto'' national library of the United States. It is the oldest federal cultural institution in the country. The libra ...

as being culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant. This footage is still shown to engineering

Engineering is the use of scientific principles to design and build machines, structures, and other items, including bridges, tunnels, roads, vehicles, and buildings. The discipline of engineering encompasses a broad range of more speciali ...

, architecture

Architecture is the art and technique of designing and building, as distinguished from the skills associated with construction. It is both the process and the product of sketching, conceiving, planning, designing, and constructing buildings ...

, and physics

Physics is the natural science that studies matter, its fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge which ...

students as a cautionary tale

A cautionary tale is a tale told in folklore to warn its listener of a danger. There are three essential parts to a cautionary tale, though they can be introduced in a large variety of ways. First, a taboo or prohibition is stated: some act, lo ...

.

Elliott and Monroe's films of the construction and collapse were shot on 16 mm Kodachrome

Kodachrome is the brand name for a color reversal film introduced by Eastman Kodak in 1935. It was one of the first successful color materials and was used for both cinematography and still photography. For many years Kodachrome was widely used ...

film, but most copies in circulation are in black and white because newsreel

A newsreel is a form of short documentary film, containing news stories and items of topical interest, that was prevalent between the 1910s and the mid 1970s. Typically presented in a cinema, newsreels were a source of current affairs, inform ...

s of the day copied the film onto 35 mm black-and-white stock

In finance, stock (also capital stock) consists of all the shares by which ownership of a corporation or company is divided.Longman Business English Dictionary: "stock - ''especially AmE'' one of the shares into which ownership of a compan ...

. There were also film-speed discrepancies between Monroe's and Elliot's footage, with Monroe filming at 24 frames per second and Elliott at 16 frames per second. As a result, most copies in circulation also show the bridge oscillating approximately 50% faster than real time, due to an assumption during conversion that the film was shot at 24 frames per second rather than the actual 16 fps.

A second reel of film emerged in February 2019, taken by Arthur Leach from the Gig Harbor (westward) side of the bridge, and one of the few known images of the collapse from that side. Leach was a civil engineer who served as toll collector for the bridge, and is believed to have been the last person to cross the bridge to the west before its collapse, trying to prevent further crossings from the west as the bridge started to collapse. Leach's footage (originally on film but then recorded to video cassette by filming the projection) also includes Leach's commentary at the time of the collapse.

Federal Works Agency commission

A commission formed by theFederal Works Agency The Federal Works Agency (FWA) was an independent agency of the federal government of the United States which administered a number of public construction, building maintenance, and public works relief functions and laws from 1939 to 1949. Along wi ...

studied the collapse of the bridge. It included Othmar Ammann

Othmar Hermann Ammann (March 26, 1879 – September 22, 1965) was a Swiss-American civil engineer whose bridge designs include the George Washington Bridge, Verrazzano-Narrows Bridge, and Bayonne Bridge. He also directed the planning and constru ...

and Theodore von Kármán

Theodore von Kármán ( hu, ( szőllőskislaki) Kármán Tódor ; born Tivadar Mihály Kármán; 11 May 18816 May 1963) was a Hungarian-American mathematician, aerospace engineer, and physicist who was active primarily in the fields of aeronaut ...

. Without drawing any definitive conclusions, the commission explored three possible failure causes:

* Aerodynamic instability by self-induced vibrations in the structure

* Eddy formations that might be periodic in nature

* Random effects of turbulence, that is the random fluctuations in velocity of the wind.

Cause of the collapse

The original Tacoma Narrows Bridge was the first to be built with girders of

The original Tacoma Narrows Bridge was the first to be built with girders of carbon steel

Carbon steel is a steel with carbon content from about 0.05 up to 2.1 percent by weight. The definition of carbon steel from the American Iron and Steel Institute (AISI) states:

* no minimum content is specified or required for chromium, coba ...

anchored in concrete blocks; preceding designs typically had open lattice beam trusses underneath the roadbed. This bridge was the first of its type to employ plate girders (pairs of deep I-beam

An I-beam, also known as H-beam (for universal column, UC), w-beam (for "wide flange"), universal beam (UB), rolled steel joist (RSJ), or double-T (especially in Polish, Bulgarian, Spanish, Italian and German), is a beam with an or -shap ...

s) to support the roadbed. With the earlier designs, any wind would simply pass through the truss, but in the new design the wind would be diverted above and below the structure. Shortly after construction finished at the end of June (opened to traffic on July 1, 1940), it was discovered that the bridge would sway and buckle

The buckle or clasp is a device used for fastening two loose ends, with one end attached to it and the other held by a catch in a secure but adjustable manner. Often taken for granted, the invention of the buckle was indispensable in securing tw ...

dangerously in relatively mild windy conditions that are common for the area, and worse during severe winds. This vibration was transverse

Transverse may refer to:

*Transverse engine, an engine in which the crankshaft is oriented side-to-side relative to the wheels of the vehicle

* Transverse flute, a flute that is held horizontally

* Transverse force (or ''Euler force''), the tange ...

, one-half of the central span rising while the other lowered. Drivers would see cars approaching from the other direction rise and fall, riding the violent energy wave through the bridge. However, at that time the mass of the bridge was considered sufficient to keep it structurally sound.

The failure of the bridge occurred when a never-before-seen twisting mode occurred, from winds at . This is a so-called torsional vibration mode (which is different from the transversal or longitudinal

Longitudinal is a geometric term of location which may refer to:

* Longitude

** Line of longitude, also called a meridian

* Longitudinal engine, an internal combustion engine in which the crankshaft is oriented along the long axis of the vehicle, ...

vibration mode), whereby when the left side of the roadway went down, the right side would rise, and vice versa, i.e., the two halves of the bridge twisted in opposite directions, with the center line of the road remaining still (motionless). This vibration was caused by aeroelastic fluttering.

Fluttering is a physical phenomenon in which several degrees of freedom

Degrees of freedom (often abbreviated df or DOF) refers to the number of independent variables or parameters of a thermodynamic system. In various scientific fields, the word "freedom" is used to describe the limits to which physical movement or ...

of a structure become coupled in an unstable oscillation driven by the wind. Here, unstable means that the forces and effects that cause the oscillation are not checked by forces and effects that limit the oscillation, so it does not self-limit but grows without bound. Eventually, the amplitude of the motion produced by the fluttering increased beyond the strength of a vital part, in this case the suspender cables. As several cables failed, the weight of the deck transferred to the adjacent cables, which became overloaded and broke in turn until almost all of the central deck fell into the water below the span.

Resonance (due to Von Kármán vortex street) hypothesis

The bridge's spectacular destruction is often used as an object lesson in the necessity to consider both

The bridge's spectacular destruction is often used as an object lesson in the necessity to consider both aerodynamics

Aerodynamics, from grc, ἀήρ ''aero'' (air) + grc, δυναμική (dynamics), is the study of the motion of air, particularly when affected by a solid object, such as an airplane wing. It involves topics covered in the field of fluid dy ...

and resonance

Resonance describes the phenomenon of increased amplitude that occurs when the frequency of an applied periodic force (or a Fourier component of it) is equal or close to a natural frequency of the system on which it acts. When an oscil ...

effects in civil

Civil may refer to:

*Civic virtue, or civility

*Civil action, or lawsuit

* Civil affairs

*Civil and political rights

*Civil disobedience

*Civil engineering

*Civil (journalism), a platform for independent journalism

*Civilian, someone not a membe ...

and structural engineering

Structural engineering is a sub-discipline of civil engineering in which structural engineers are trained to design the 'bones and muscles' that create the form and shape of man-made structures. Structural engineers also must understand and cal ...

. Billah and Scanlan (1991) reported that, in fact, many physics textbooks (for example Resnick et al. and Tipler et al.)) wrongly explain that the cause of the failure of the Tacoma Narrows bridge was externally forced mechanical resonance. Resonance is the tendency of a system to oscillate at larger amplitudes at certain frequencies, known as the system's natural frequencies. At these frequencies, even relatively small periodic driving forces can produce large amplitude vibrations, because the system stores energy. For example, a child using a swing realizes that if the pushes are properly timed, the swing can move with a very large amplitude. The driving force, in this case the child pushing the swing, exactly replenishes the energy that the system loses if its frequency equals the natural frequency of the system.

Usually, the approach taken by those physics textbooks is to introduce a first order forced oscillator, defined by the second-order differential equation

where , and stand for the mass

Mass is an intrinsic property of a body. It was traditionally believed to be related to the quantity of matter in a physical body, until the discovery of the atom and particle physics. It was found that different atoms and different ele ...

, damping coefficient

Damping is an influence within or upon an oscillatory system that has the effect of reducing or preventing its oscillation. In physical systems, damping is produced by processes that dissipate the energy stored in the oscillation. Examples in ...

and stiffness

Stiffness is the extent to which an object resists deformation in response to an applied force.

The complementary concept is flexibility or pliability: the more flexible an object is, the less stiff it is.

Calculations

The stiffness, k, of a ...

of the linear system

In systems theory, a linear system is a mathematical model of a system based on the use of a linear operator.

Linear systems typically exhibit features and properties that are much simpler than the nonlinear case.

As a mathematical abstraction ...

and and represent the amplitude and the angular frequency

In physics, angular frequency "''ω''" (also referred to by the terms angular speed, circular frequency, orbital frequency, radian frequency, and pulsatance) is a scalar measure of rotation rate. It refers to the angular displacement per unit ti ...

of the exciting force. The solution of such ordinary differential equation

In mathematics, an ordinary differential equation (ODE) is a differential equation whose unknown(s) consists of one (or more) function(s) of one variable and involves the derivatives of those functions. The term ''ordinary'' is used in contrast ...

as a function of time represents the displacement response of the system (given appropriate initial conditions). In the above system resonance happens when is approximately , i.e., is the natural (resonant) frequency of the system. The actual vibration analysis of a more complicated mechanical system — such as an airplane, a building or a bridge — is based on the linearization of the equation of motion for the system, which is a multidimensional version of equation (). The analysis requires eigenvalue

In linear algebra, an eigenvector () or characteristic vector of a linear transformation is a nonzero vector that changes at most by a scalar factor when that linear transformation is applied to it. The corresponding eigenvalue, often denote ...

analysis and thereafter the natural frequencies of the structure are found, together with the so-called ''fundamental modes'' of the system, which are a set of independent displacements and/or rotations that specify completely the displaced or deformed position and orientation of the body or system, i.e., the bridge moves as a (linear) combination of those basic deformed positions.

Each structure has natural frequencies. For resonance to occur, it is necessary to have also periodicity in the excitation force. The most tempting candidate of the periodicity in the wind force was assumed to be the so-called vortex shedding

In fluid dynamics, vortex shedding is an oscillating flow that takes place when a fluid such as air or water flows past a bluff (as opposed to streamlined) body at certain velocities, depending on the size and shape of the body. In this flow, v ...

. This is because bluff (non-streamlined) bodies — like bridge decks — in a fluid stream produce (or "shed") wakes, whose characteristics depend on the size and shape of the body and the properties of the fluid. These wakes are accompanied by alternating low-pressure vortices on the downwind side of the body, the so-called Kármán vortex street

In fluid dynamics, a Kármán vortex street (or a von Kármán vortex street) is a repeating pattern of swirling vortices, caused by a process known as vortex shedding, which is responsible for the unsteady separation of flow of a fluid arou ...

or von Kármán vortex street. The body will in consequence try to move toward the low-pressure zone, in an oscillating movement called vortex-induced vibration. Eventually, if the frequency of vortex shedding matches the natural frequency of the structure, the structure will begin to resonate and the structure's movement can become self-sustaining.

The frequency of the vortices in the von Kármán vortex street is called the Strouhal frequency , and is given by

Here, stands for the flow velocity, is a characteristic length of the bluff body

In fluid dynamics, the drag coefficient (commonly denoted as: c_\mathrm, c_x or c_) is a dimensionless quantity that is used to quantify the drag or resistance of an object in a fluid environment, such as air or water. It is used in the drag equ ...

and is the dimensionless Strouhal number

In dimensional analysis, the Strouhal number (St, or sometimes Sr to avoid the conflict with the Stanton number) is a dimensionless number describing oscillating flow mechanisms. The parameter is named after Vincenc Strouhal, a Czech physicist ...

, which depends on the body in question. For Reynolds number

In fluid mechanics, the Reynolds number () is a dimensionless quantity that helps predict fluid flow patterns in different situations by measuring the ratio between inertial and viscous forces. At low Reynolds numbers, flows tend to be dom ...

s greater than 1000, the Strouhal number is approximately equal to 0.21. In the case of the Tacoma Narrows, was approximately and was 0.20.

It was thought that the Strouhal frequency was close enough to one of the natural vibration frequencies of the bridge, i.e., , to cause resonance and therefore vortex-induced vibration.

In the case of the Tacoma Narrows Bridge, this appears not to have been the cause of the catastrophic damage. According to Professor Frederick Burt Farquharson, an engineering professor at the University of Washington and one of the main researchers into the cause of the bridge collapse, the wind was steady at and the frequency of the destructive mode was 12 cycles/minute (0.2 Hz). This frequency was neither a natural mode of the isolated structure nor the frequency of blunt-body vortex shedding

In fluid dynamics, vortex shedding is an oscillating flow that takes place when a fluid such as air or water flows past a bluff (as opposed to streamlined) body at certain velocities, depending on the size and shape of the body. In this flow, v ...

of the bridge at that wind speed, which was approximately 1 Hz. It can be concluded therefore that the vortex shedding was not the cause of the bridge collapse. The event can be understood only while considering the coupled aerodynamic and structural system that requires rigorous mathematical analysis to reveal all the degrees of freedom of the particular structure and the set of design loads imposed.

Vortex-induced vibration is a far more complex process that involves both the external wind-initiated forces and internal self-excited forces that lock on to the motion of the structure. During lock-on, the wind forces drive the structure at or near one of its natural frequencies, but as the amplitude increases this has the effect of changing the local fluid boundary conditions, so that this induces compensating, self-limiting forces, which restrict the motion to relatively benign amplitudes. This is clearly not a linear resonance phenomenon, even if the bluff body has linear behaviour, since the exciting force amplitude is a nonlinear force of the structural response.Billah, K.Y.R. and Scanlan, R.H. "Vortex-Induced Vibration and its Mathematical Modeling: A Bibliography", Report No. SM-89-1. Department of Civil Engineering. Princeton University

Princeton University is a private research university in Princeton, New Jersey. Founded in 1746 in Elizabeth as the College of New Jersey, Princeton is the fourth-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and one of the ...

. April 1989

Resonance vs. non-resonance explanations

Billah and Scanlan state that Lee Edson in his biography ofTheodore von Kármán

Theodore von Kármán ( hu, ( szőllőskislaki) Kármán Tódor ; born Tivadar Mihály Kármán; 11 May 18816 May 1963) was a Hungarian-American mathematician, aerospace engineer, and physicist who was active primarily in the fields of aeronaut ...

is a source of misinformation: "The culprit in the Tacoma disaster was the Karman vortex street."

However, the Federal Works Administration report of the investigation, of which von Kármán was part, concluded that

A group of physicists cited "wind-driven amplification of the torsional oscillation" as distinct from resonance:

To some degree the debate is due to the lack of a commonly accepted precise definition of resonance. Billah and Scanlan provide the following definition of resonance "In general, whenever a system capable of oscillation is acted on by a periodic series of impulses having a frequency equal to or nearly equal to one of the natural frequencies of the oscillation of the system, the system is set into oscillation with a relatively large amplitude." They then state later in their paper "Could this be called a resonant phenomenon? It would appear not to contradict the qualitative definition of resonance quoted earlier, if we now identify the source of the periodic impulses as ''self-induced'', the wind supplying the power, and the motion supplying the power-tapping mechanism. If one wishes to argue, however, that it was a case of ''externally forced linear resonance'', the mathematical distinction ... is quite clear, self-exciting systems differing strongly enough from ordinary linear resonant ones."

Link to the Armistice Day blizzard

The weather system that caused the bridge collapse went on to cause the 1940 Armistice Day Blizzard that killed 145 people in theMidwestern United States

The Midwestern United States, also referred to as the Midwest or the American Midwest, is one of four census regions of the United States Census Bureau (also known as "Region 2"). It occupies the northern central part of the United States. I ...

:

Fate of the collapsed superstructure

Efforts to salvage the bridge began almost immediately after its collapse and continued into May 1943. Two review boards, one appointed by the federal government and one appointed by the state of Washington, concluded that repair of the bridge was impossible, and the entire bridge would have to be dismantled and an entirely new bridgesuperstructure

A superstructure is an upward extension of an existing structure above a baseline. This term is applied to various kinds of physical structures such as buildings, bridges, or ships.

Aboard ships and large boats

On water craft, the superstruct ...

built. With steel being a valuable commodity because of the involvement of the United States in World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

, steel from the bridge cables and the suspension span was sold as scrap metal to be melted down. The salvage operation cost the state more than was returned from the sale of the material, a net loss of over $350,000 (equivalent to $ million today).

The cable anchorages, tower pedestals and most of the remaining substructure were relatively undamaged in the collapse, and were reused during construction of the replacement span that opened in 1950. The towers, which supported the main cables and road deck, suffered major damage at their bases from being deflected towards shore as a result of the collapse of the mainspan and the sagging of the sidespans. They were dismantled, and the steel sent to recyclers.

Preservation of the collapsed roadway

The underwater remains of the highway deck of the old suspension bridge act as a large artificial reef, and these are listed on the

The underwater remains of the highway deck of the old suspension bridge act as a large artificial reef, and these are listed on the National Register of Historic Places

The National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) is the United States federal government's official list of districts, sites, buildings, structures and objects deemed worthy of preservation for their historical significance or "great artistic ...

with reference number 92001068.

The Harbor History Museum has a display in its main gallery regarding the 1940 bridge, its collapse, and the subsequent two bridges.

A lesson for history

Othmar Ammann

Othmar Hermann Ammann (March 26, 1879 – September 22, 1965) was a Swiss-American civil engineer whose bridge designs include the George Washington Bridge, Verrazzano-Narrows Bridge, and Bayonne Bridge. He also directed the planning and constru ...

, a leading bridge designer and member of the Federal Works Agency Commission investigating the collapse of the Tacoma Narrows Bridge, wrote:

Following the incident, engineers took extra caution to incorporate aerodynamics into their designs, and wind tunnel

Wind tunnels are large tubes with air blowing through them which are used to replicate the interaction between air and an object flying through the air or moving along the ground. Researchers use wind tunnels to learn more about how an aircraft ...

testing of designs was eventually made mandatory.

The Bronx–Whitestone Bridge

The Bronx–Whitestone Bridge (colloquially referred to as the Whitestone Bridge or simply the Whitestone) is a suspension bridge in New York City, carrying six lanes of Interstate 678 over the East River. The bridge connects Throggs Neck and ...

, which is of similar design to the 1940 Tacoma Narrows Bridge, was reinforced shortly after the collapse. Fourteen-foot-high (4.3 m) steel trusses were installed on both sides of the deck in 1943 to weigh down and stiffen the bridge in an effort to reduce oscillation. In 2003, the stiffening trusses were removed and aerodynamic fiberglass fairings were installed along both sides of the road deck.

A key consequence was that suspension bridges reverted to a deeper and heavier truss

A truss is an assembly of ''members'' such as beams, connected by ''nodes'', that creates a rigid structure.

In engineering, a truss is a structure that "consists of two-force members only, where the members are organized so that the assembl ...

design, including the replacement Tacoma Narrows Bridge (1950), until the development in the 1960s of box girder bridge

A box girder bridge, or box section bridge, is a bridge in which the main beams comprise girders in the shape of a hollow box. The box girder normally comprises prestressed concrete, structural steel, or a composite of steel and ...

s with an airfoil

An airfoil (American English) or aerofoil (British English) is the cross-sectional shape of an object whose motion through a gas is capable of generating significant lift, such as a wing, a sail, or the blades of propeller, rotor, or turbin ...

shape such as the Severn Bridge, which gave the necessary stiffness together with reduced torsional forces.

Replacement bridge

Because of shortages in materials and labor as a result of the involvement of the United States in World War II, it took 10 years before a replacement bridge was opened to traffic. This replacement bridge was opened to traffic on October 14, 1950, and is long, longer than the original bridge. The replacement bridge also has more lanes than the original bridge, which only had two traffic lanes, plus shoulders on both sides. Half a century later, the replacement bridge exceeded its traffic capacity, and a second, parallel, suspension bridge was constructed to carry eastbound traffic. The suspension bridge that was completed in 1950 was reconfigured to carry only westbound traffic. The new parallel bridge opened to traffic in July 2007.See also

*Engineering disasters

Engineering disasters often arise from shortcuts in the design process. Engineering is the science and technology used to meet the needs and demands of society. These demands include buildings, aircraft, vessels, and computer software. In order t ...

* Humen Pearl River Bridge

The Humen Pearl River Bridge () is a bridge over the Humen, Pearl River in Guangdong Province, southern China. It consists of two main spans - a suspension bridge section and a segmental concrete section. It connects the Nansha District of Guan ...

, suspension bridge that has shakened violently until weight limits initiated

* List of bridge failures

This is a list of bridge failures.

Before 1800

1800–1899

1900–1949

1950–1999

2000–present

Bridge disasters in fiction

* Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince (2005 novel): the fictional Brockdale Bridge, by the Death Eaters ( ...

* List of structural failures and collapses

This is a list of structural failures and collapses, including bridges, dams, and radio masts/towers.

Buildings and other fixed human-made structures

Antiquity to the Middle Ages

17th–19th centuries

1900–1949

1950-1979

1980–2000 ...

* Millennium Bridge, London

The Millennium Bridge, officially known as the London Millennium Footbridge, is a steel suspension bridge for pedestrians crossing the River Thames in London, England, linking Bankside with the City of London. It is owned and maintained by Br ...

, for an engineering error

* Silver Bridge

The Silver Bridge was an eyebar-chain suspension bridge built in 1928 and named for the color of its aluminum paint. The bridge carried U.S. Route 35 over the Ohio River, connecting Point Pleasant, West Virginia, and Gallipolis, Ohio.

On Dec ...

, a bridge that collapsed in 1967 on the West Virginia–Ohio border

* Volgograd Bridge, a bridge in Russia that experienced similar problems with the wind

References

Further reading

* * * * * * *External links

* *The Tacoma Narrows Bridge Disaster, November 1940

at University of Bristol

Tacoma Narrows Bridge Failure

at Carleton University

at the Gig Harbor Peninsula Historical Society & Museum

at Ketchum.org {{Authority control

1940

A calendar from 1940 according to the Gregorian calendar, factoring in the dates of Easter and related holidays, cannot be used again until the year 5280.

Events

Below, the events of World War II have the "WWII" prefix.

January

* Januar ...

1940 establishments in Washington (state)

1940 disestablishments in Washington (state)

1940 disasters in the United States

1940 in Washington (state)

Articles containing video clips

Artificial reefs

Bridge disasters caused by engineering error

Bridge disasters in the United States

Bridges completed in 1940

Bridges in Tacoma, Washington

Engineering failures

Former toll bridges in Washington (state)

Historic Civil Engineering Landmarks

National Register of Historic Places in Tacoma, Washington

North Tacoma, Washington

November 1940 events

Road bridges on the National Register of Historic Places in Washington (state)

Steel bridges in the United States

Suspension bridges in Washington (state)

Transport disasters in 1940

Transportation disasters in Washington (state)