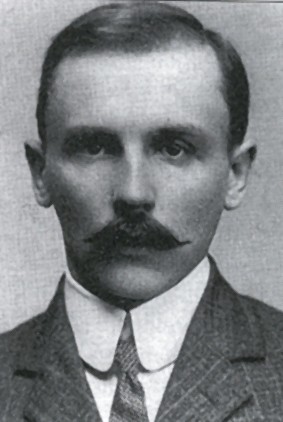

Tytus Filipowicz on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Tytus Filipowicz (1873–1953) was a Polish politician and diplomat.

Tytus Filipowicz (1873–1953) was a Polish politician and diplomat.

"''Ci, którzy rozsławili Dąbrowę Górniczą''"

''gazeta.pl'', 2006-11-14 He became an active member of the

online

/ref> He accompanied Piłsudski on his 1904 voyage to

Telegram

short biographical note in an article in the periodical ''Wspólnota Polska'' or acting (sources vary)

Tytus Filipowicz (1873–1953) was a Polish politician and diplomat.

Tytus Filipowicz (1873–1953) was a Polish politician and diplomat.

Life

Filipowicz was born on 21 November 1873 inWarsaw

Warsaw ( pl, Warszawa, ), officially the Capital City of Warsaw,, abbreviation: ''m.st. Warszawa'' is the capital and largest city of Poland. The metropolis stands on the River Vistula in east-central Poland, and its population is officia ...

. He attended school in Dąbrowa Górnicza

Dąbrowa Górnicza is a city in Zagłębie Dąbrowskie, southern Poland, near Katowice and Sosnowiec. It is located in eastern part of the Silesian Voivodeship, on the Czarna Przemsza and Biała Przemsza rivers (tributaries of the Vistula, see ...

. He worked as a coal miner and became a socialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the e ...

political activist; from 1895 he was active in the Dąbrowa Workers' Committee. Zygmunt Woźniczka"''Ci, którzy rozsławili Dąbrowę Górniczą''"

''gazeta.pl'', 2006-11-14 He became an active member of the

Polish Socialist Party

The Polish Socialist Party ( pl, Polska Partia Socjalistyczna, PPS) is a socialist political party in Poland.

It was one of the most important parties in Poland from its inception in 1892 until its merger with the communist Polish Workers' P ...

(''PPS'') and editor of a socialist paper for miners (''Górnik'', Miner). In 1901 he was arrested by the authorities but escaped to Russian-ruled Warsaw

Warsaw ( pl, Warszawa, ), officially the Capital City of Warsaw,, abbreviation: ''m.st. Warszawa'' is the capital and largest city of Poland. The metropolis stands on the River Vistula in east-central Poland, and its population is officia ...

.

During the ''PPS'' split, he sided with the Polish Socialist Party – Revolutionary Faction

The Polish Socialist Party – Revolutionary Faction ( pl, Polska Partia Socjalistyczna – Frakcja Rewolucyjna, PPS–FR) also known as the Old Faction ( pl, Starzy, links=no) was one of two factions into which the Polish Socialist Party split ...

and became a close collaborator of future Polish statesman Józef Piłsudski

), Vilna Governorate, Russian Empire (now Lithuania)

, death_date =

, death_place = Warsaw, Poland

, constituency =

, party = None (formerly PPS)

, spouse =

, children = Wan ...

.Marek Kornat, "''Posłowie i ambasadorzy polscy w Związku Sowieckim (1921–1939 i 1941–1943)''" ("Polish Diplomatic Representatives and Ambassadors in the Soviet Union (1921–39 and 1941–43"), ''The Polish Diplomatic Review'', 5 (21)/2004, pp. 129-20online

/ref> He accompanied Piłsudski on his 1904 voyage to

Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north ...

. In 1905 Filipowicz was imprisoned by the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. ...

in the Warsaw Citadel

Warsaw Citadel (Polish: Cytadela Warszawska) is a 19th-century fortress in Warsaw, Poland. It was built by order of Tsar Nicholas I after the suppression of the 1830 November Uprising in order to bolster imperial Russian control of the city. I ...

, but escaped.

Under the Second Polish Republic

The Second Polish Republic, at the time officially known as the Republic of Poland, was a country in Central Europe, Central and Eastern Europe that existed between 1918 and 1939. The state was established on 6 November 1918, before the end of ...

, he was briefly deputyTelegram

short biographical note in an article in the periodical ''Wspólnota Polska'' or acting (sources vary)

Polish Minister of Foreign Affairs

The Ministry of Foreign Affairs (''Ministerstwo Spraw Zagranicznych'', MSZ) is the Polish government department tasked with maintaining Poland's international relations and coordinating its participation in international and regional supra-nation ...

(11–17 November 1918). Later he was named Poland's ambassador to Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

—due to his involvement in Piłsudski's Prometheist project—but in the aftermath of the Soviet invasion of Georgia

The Red Army invasion of Georgia (15 February17 March 1921), also known as the Soviet–Georgian War or the Soviet invasion of Georgia,Debo, R. (1992). ''Survival and Consolidation: The Foreign Policy of Soviet Russia, 1918-1921'', pp. 182, 361� ...

(which was subsequently annexed as the Georgian Soviet Socialist Republic

The Georgian Soviet Socialist Republic (Georgian SSR; ka, საქართველოს საბჭოთა სოციალისტური რესპუბლიკა, tr; russian: Грузинская Советская Соц� ...

) he did not assume this post but was instead arrested there by the Soviets and interned. After the treaty of Riga

The Peace of Riga, also known as the Treaty of Riga ( pl, Traktat Ryski), was signed in Riga on 18 March 1921, among Poland, Soviet Russia (acting also on behalf of Soviet Belarus) and Soviet Ukraine. The treaty ended the Polish–Soviet War.

...

ended the Polish-Soviet War in 1921, he became the first Polish chargé d'affaires

A ''chargé d'affaires'' (), plural ''chargés d'affaires'', often shortened to ''chargé'' (French) and sometimes in colloquial English to ''charge-D'', is a diplomat who serves as an embassy's chief of mission in the absence of the ambassador ...

in the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

, organizing the Polish embassy there. Later he was a diplomat in Finland

Finland ( fi, Suomi ; sv, Finland ), officially the Republic of Finland (; ), is a Nordic country in Northern Europe. It shares land borders with Sweden to the northwest, Norway to the north, and Russia to the east, with the Gulf of B ...

, Belgium

Belgium, ; french: Belgique ; german: Belgien officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. The country is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeast, France to th ...

and the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

(1929-32).

In 1934, with Gabriel Czechowicz

Gabriel Czechowicz (1876-1938) was a Polish lawyer, economist and politician. He was the Polish Treasury Minister from 1926 to 1929. Accused of misuse of government funds, Czechowicz was the only Polish politician of the interwar period that fa ...

, Filipowicz co-founded the Polish Radical Party (''Polska Partia Radykalna''), a dissident offshoot of Sanation

Sanation ( pl, Sanacja, ) was a Polish political movement that was created in the interwar period, prior to Józef Piłsudski's May 1926 ''Coup d'État'', and came to power in the wake of that coup. In 1928 its political activists would go on ...

that, while largely adhering to political liberalism

Liberalism is a political and moral philosophy based on the rights of the individual, liberty, consent of the governed, political equality and equality before the law."political rationalism, hostility to autocracy, cultural distaste for co ...

, advocated that Poland become a Christian

Christians () are people who follow or adhere to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. The words ''Christ'' and ''Christian'' derive from the Koine Greek title ''Christós'' (Χρι ...

state, with official preferences given to ethnic Poles, and Jews being encouraged to emigrate.

During and after World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, Filipowicz was a member of the Polish Government in Exile

The Polish government-in-exile, officially known as the Government of the Republic of Poland in exile ( pl, Rząd Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej na uchodźstwie), was the government in exile of Poland formed in the aftermath of the Invasion of Pola ...

and of the National Council of the Republic of Poland (1941–42 and 1949–53).

He died on 18 August 1953 in London

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a majo ...

.

See also

*Prometheism

Prometheism or Prometheanism (Polish: ''Prometeizm'') was a political project initiated by Józef Piłsudski, a principal statesman of the Second Polish Republic from 1918 to 1935. Its aim was to weaken the Russian Empire and its successor states, ...

*List of Poles

This is a partial list of notable Polish or Polish-speaking or -writing people. People of partial Polish heritage have their respective ancestries credited.

Science

Physics

* Czesław Białobrzeski

* Andrzej Buras

* Georges Charpak ...

Notes

{{DEFAULTSORT:Filipowicz, Tytus 1873 births 1953 deaths Politicians from Warsaw People from Warsaw Governorate Ambassadors of Poland to the United States Diplomats of the Second Polish Republic Ambassadors of Poland to Georgia (country)