Tsvetayeva on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

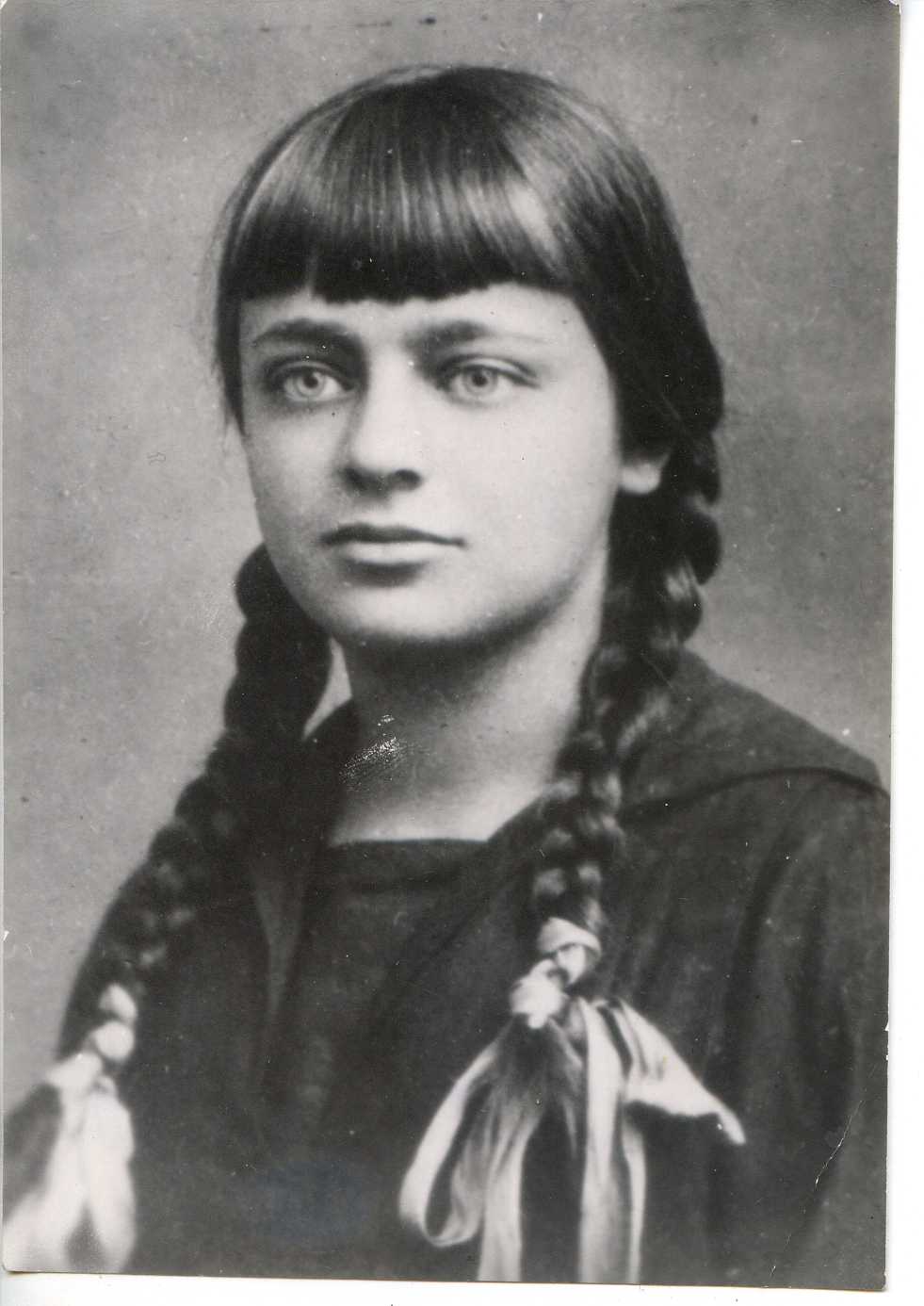

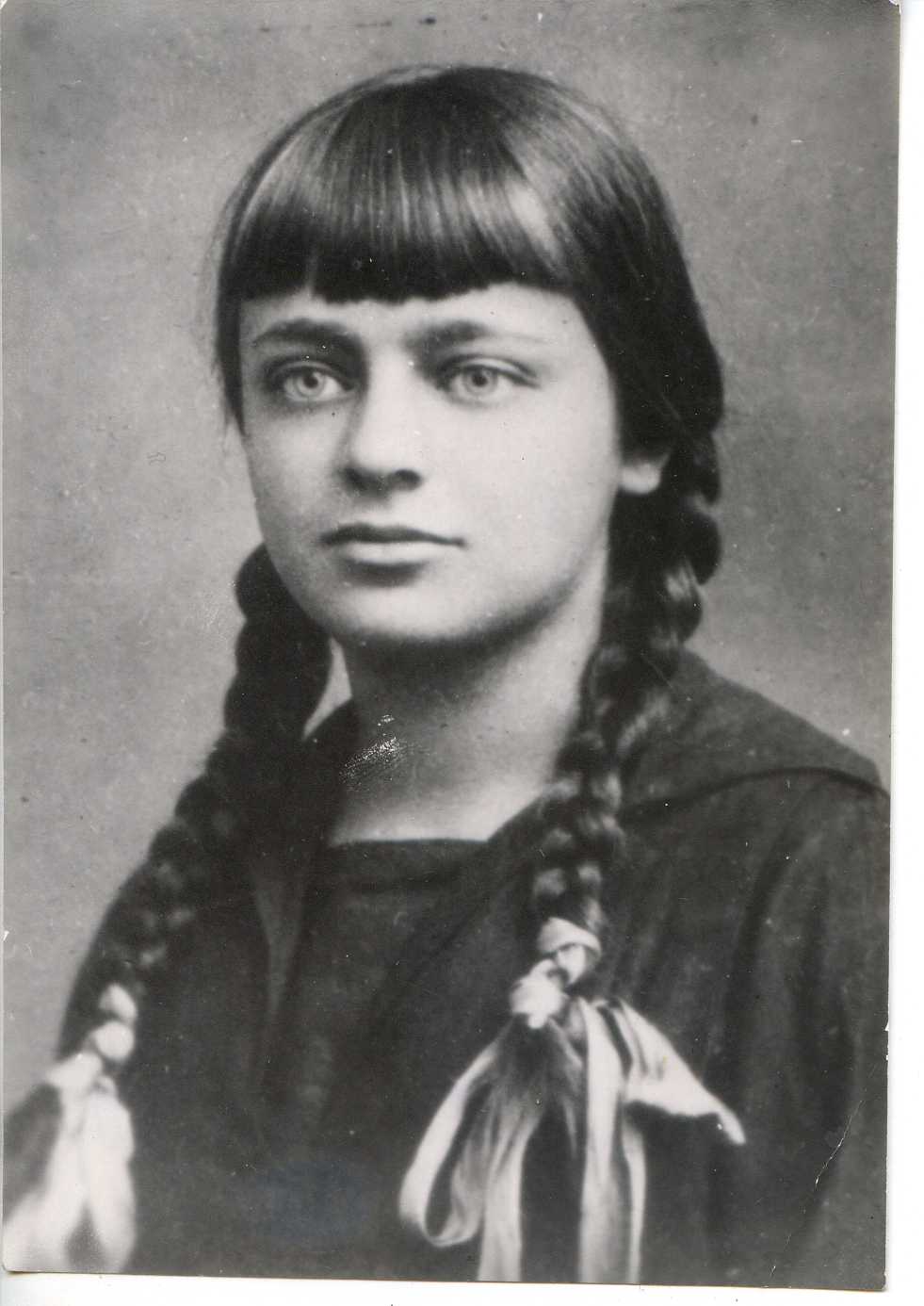

Marina Ivanovna Tsvetaeva (russian: Марина Ивановна Цветаева, p=mɐˈrʲinə ɪˈvanəvnə tsvʲɪˈtaɪvə; 31 August 1941) was a Russian poet. Her work is considered among some of the greatest in twentieth century Russian literature."Tsvetaeva, Marina Ivanovna" ''Who's Who in the Twentieth Century''. Oxford University Press, 1999. She lived through and wrote of the Russian Revolution of 1917 and the Moscow famine that followed it. In an attempt to save her daughter Irina from starvation, she placed her in a state orphanage in 1919, where she died of hunger. Tsvetaeva left Russia in 1922 and lived with her family in increasing poverty in Paris, Berlin and Prague before returning to Moscow in 1939. Her husband

She began spending time at Voloshin's home in the

She began spending time at Voloshin's home in the

In May 1922, Tsvetaeva and Ariadna left

In May 1922, Tsvetaeva and Ariadna left

In 1939, she and her son returned to Moscow, unaware of the reception she would receive. In

In 1939, she and her son returned to Moscow, unaware of the reception she would receive. In

Tsvetaeva's last ten years of exile, from 1928 when "After Russia" appeared until her return in 1939 to the Soviet Union, were principally a "prose decade", though this would almost certainly be by dint of economic necessity rather than one of choice.

Tsvetaeva's last ten years of exile, from 1928 when "After Russia" appeared until her return in 1939 to the Soviet Union, were principally a "prose decade", though this would almost certainly be by dint of economic necessity rather than one of choice.

Another version

* . Dramatic reading in English with artistic video. Includes download link.

"Marina Tsvetaeva, ''Poet of the extreme''"

by Belinda Cooke from ''South'' magazine #31, April 2005. Republished online in the

A small site dedicated to Tsvetaeva

Marina Tsvetaeva biography

at Carcanet Press, English language publisher of Tsvetaeva's ''Bride of Ice'' and ''Marina Tsvetaeva: Selected Poems'', translated by

Heritage of Marina Tsvetayeva

a resource in English wit

a more extensive version in Russian

Тоска по родине / Nostalgia

an

four more poems

from the book "To You – in 10 Decades", translated by

"She Means It When She Rhymes: ''Marina Tsvetaeva: Selected Poems''."

Review from ''Thumbscrew'' #17, Winter 2000/1, of works translated by Elaine Feinstein.

The Poems

by Marina Tsvetaeva {{DEFAULTSORT:Tsvetaeva, Marina 1892 births 1941 suicides 20th-century Russian women writers Poets from the Russian Empire Soviet emigrants to Germany German emigrants to Czechoslovakia Diarists from the Russian Empire Women poets from the Russian Empire Suicides by hanging in the Soviet Union University of Paris alumni Women diarists Writers from Moscow Russian LGBT poets 20th-century Russian poets 20th-century Russian diarists Soviet diarists 20th-century LGBT people Soviet women poets Female suicides

Sergei Efron

Sergei Yakovlevich Efron (russian: Сергей Яковлевич Эфрон; 8 October 1893 – 11 September 1941) was a Russian poet, White Army officer, and the husband of fellow poet Marina Tsvetaeva. While in exile, he was recruited by the ...

and their daughter Ariadna

''Ariadna'' is a genus of tube-dwelling spider (family Segestriidae).

Species

, the World Spider Catalog accepted the following species:

*'' Ariadna abbreviata'' Marsh, Stevens & Framenau, 2022 – Tasmania

*''Ariadna abrilae'' Grismado, 20 ...

(Alya) were arrested on espionage charges in 1941; her husband was executed. Tsvetaeva committed suicide in 1941. As a lyrical poet, her passion and daring linguistic experimentation mark her as a striking chronicler of her times and the depths of the human condition.

Early years

Marina Tsvetaeva was born inMoscow

Moscow ( , US chiefly ; rus, links=no, Москва, r=Moskva, p=mɐskˈva, a=Москва.ogg) is the capital and largest city of Russia. The city stands on the Moskva River in Central Russia, with a population estimated at 13.0 millio ...

, the daughter of Ivan Vladimirovich Tsvetaev, a professor of Fine Art at the University of Moscow

M. V. Lomonosov Moscow State University (MSU; russian: Московский государственный университет имени М. В. Ломоносова) is a public research university in Moscow, Russia and the most prestigious ...

, who later founded the Alexander III Museum of Fine Arts (known from 1937 as the Pushkin Museum). Tsvetaeva's mother, , Ivan's second wife, was a concert pianist, highly literate, with German and Polish ancestry. Growing up in considerable material comfort,Feinstein (1993) pix Tsvetaeva would later come to identify herself with the Polish aristocracy.

Tsvetaeva's two half-siblings, Valeria and Andrei, were the children of Ivan's deceased first wife, Varvara Dmitrievna Ilovaiskaya, daughter of the historian Dmitry Ilovaisky

Dmitry Ivanovich Ilovaysky (; February 11/23, 1832, Ranenburg - February 15, 1920) was an anti-Normanist conservative Russian historian who penned a number of standard history textbooks.

Ilovaysky graduated from the Moscow University in 1854 a ...

. Tsvetaeva's only full sister, Anastasia

Anastasia (from el, Ἀναστασία, translit=Anastasía) is a feminine given name of Greek origin, derived from the Greek word (), meaning "resurrection". It is a popular name in Eastern Europe, particularly in Russia, where it was the most ...

, was born in 1894. The children quarrelled frequently and occasionally violently. There was considerable tension between Tsvetaeva's mother and Varvara's children, and Tsvetaeva's father maintained close contact with Varvara's family. Tsvetaeva's father was kind, but deeply wrapped up in his studies and distant from his family. He was also still deeply in love with his first wife; he would never get over her. Maria Tsvetaeva had had a love affair before her marriage, from which she never recovered. Maria Tsvetaeva disapproved of Marina's poetic inclination; she wanted her daughter to become a pianist, holding the opinion that her poetry was poor.

In 1902, Tsvetaeva's mother contracted tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease usually caused by '' Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can also affect other parts of the body. Most infections show no symptoms, i ...

. A change in climate was believed to help cure the disease, and so the family travelled abroad until shortly before her death in 1906, when Tsvetaeva was 14. They lived for a while by the sea at Nervi

Nervi is a former fishing village 12 miles (19 km) northwest of Portofino on the Riviera di Levante, now a seaside resort in Liguria, in northwest Italy. Once an independent '' comune'', it is now a ''quartiere'' of Genoa. Nervi is 4 miles ...

, near Genoa

Genoa ( ; it, Genova ; lij, Zêna ). is the capital of the Italian region of Liguria and the sixth-largest city in Italy. In 2015, 594,733 people lived within the city's administrative limits. As of the 2011 Italian census, the Province of ...

. There, away from the rigid constraints of a bourgeois Muscovite life, Tsvetaeva was able for the first time to run free, climb cliffs, and vent her imagination in childhood games. There were many Russian ''émigré'' revolutionaries residing at that time in Nervi, who may have had some influence on the young Tsvetaeva.

In June 1904, Tsvetaeva was sent to school in Lausanne

, neighboring_municipalities= Bottens, Bretigny-sur-Morrens, Chavannes-près-Renens, Cheseaux-sur-Lausanne, Crissier, Cugy, Écublens, Épalinges, Évian-les-Bains (FR-74), Froideville, Jouxtens-Mézery, Le Mont-sur-Lausanne, Lugrin (FR ...

. Changes in the Tsvetaev residence led to several changes in school, and during the course of her travels she acquired the Italian, French, and German languages. She gave up the strict musical studies that her mother had imposed and turned to poetry. She wrote "With a mother like her, I had only one choice: to become a poet".

In 1908, aged 16, Tsvetaeva studied literary history at the Sorbonne

Sorbonne may refer to:

* Sorbonne (building), historic building in Paris, which housed the University of Paris and is now shared among multiple universities.

*the University of Paris (c. 1150 – 1970)

*one of its components or linked institution, ...

. During this time, a major revolutionary change was occurring within Russian poetry: the flowering of the Russian symbolist movement

Russian symbolism was an intellectual and artistic movement predominant at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century. It arose separately from European symbolism, emphasizing mysticism and ostranenie.

Literature

Influences

Primary ...

, and this movement was to colour most of her later work. It was not the theory which was to attract her, but the poetry and the gravity which writers such as Andrei Bely

Boris Nikolaevich Bugaev ( rus, Бори́с Никола́евич Буга́ев, p=bɐˈrʲis nʲɪkɐˈlajɪvʲɪtɕ bʊˈɡajɪf, a=Boris Nikolayevich Bugayev.ru.vorb.oga), better known by the pen name Andrei Bely or Biely ( rus, Андр� ...

and Alexander Blok

Alexander Alexandrovich Blok ( rus, Алекса́ндр Алекса́ндрович Бло́к, p=ɐlʲɪˈksandr ɐlʲɪˈksandrəvʲɪtɕ ˈblok, a=Ru-Alyeksandr Alyeksandrovich Blok.oga; 7 August 1921) was a Russian lyrical poet, writer, publ ...

were capable of generating. Her own first collection of poems, ''Vecherny Albom'' (''Evening Album''), self-published in 1910, promoted her considerable reputation as a poet. It was well received, although her early poetry was held to be insipid compared to her later work. It attracted the attention of the poet and critic Maximilian Voloshin

Maximilian Alexandrovich Kirienko-Voloshin (russian: Максимилиа́н Алекса́ндрович Кирие́нко-Воло́шин; May 28, Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates">O.S._May_16.html" ;"title="Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ...

, whom Tsvetaeva described after his death in ''A Living Word About a Living Man''. Voloshin came to see Tsvetaeva and soon became her friend and mentor.

Family and career

She began spending time at Voloshin's home in the

She began spending time at Voloshin's home in the Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal mediterranean sea of the Atlantic Ocean lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bounded by Bulgaria, Georgia, Rom ...

resort of Koktebel

Koktebel ( uk, Коктебéль, russian: Коктебéль, crh, Köktöbel, formerly known as ''Planerskoye'', russian: Планерское) is an urban-type settlement and one of the most popular resort townlets in South-Eastern Crimea. K ...

("Blue Height"), which was a well-known haven for writers, poets and artists. She became enamoured of the work of Alexander Blok and Anna Akhmatova

Anna Andreyevna Gorenko rus, А́нна Андре́евна Горе́нко, p=ˈanːə ɐnˈdrʲe(j)ɪvnə ɡɐˈrʲɛnkə, a=Anna Andreyevna Gorenko.ru.oga, links=yes; uk, А́нна Андрі́ївна Горе́нко, Ánna Andríyivn ...

, although she never met Blok and did not meet Akhmatova until the 1940s. Describing the Koktebel community, the ''émigré'' Viktoria Schweitzer wrote: "Here inspiration was born." At Koktebel, Tsvetaeva met Sergei Yakovlevich Efron, a 17-year-old cadet in the Officers' Academy. She was 19, he 18: they fell in love and were married in 1912, the same year as her father's project, the Alexander III Museum of Fine Arts, was ceremonially opened, an event attended by Tsar Nicholas II. Tsvetaeva's love for Efron was intense; however, this did not preclude her from having affairs, including one with Osip Mandelstam

Osip Emilyevich Mandelstam ( rus, Осип Эмильевич Мандельштам, p=ˈosʲɪp ɨˈmʲilʲjɪvʲɪtɕ mənʲdʲɪlʲˈʂtam; – 27 December 1938) was a Russian and Soviet poet. He was one of the foremost members of the A ...

, which she celebrated in a collection of poems called ''Mileposts''. At around the same time, she became involved in an affair with the poet Sophia Parnok, who was 7 years older than Tsvetaeva, an affair that caused her husband great grief. The two women fell deeply in love, and the relationship profoundly affected both women's writings. She deals with the ambiguous and tempestuous nature of this relationship in a cycle of poems which at times she called ''The Girlfriend'', and at other times ''The Mistake''. Tsvetaeva and her husband spent summers in the Crimea until the revolution, and had two daughters: Ariadna, or Alya (born 1912) and Irina (born 1917).

In 1914, Efron volunteered for the front and by 1917 he was an officer stationed in Moscow

Moscow ( , US chiefly ; rus, links=no, Москва, r=Moskva, p=mɐskˈva, a=Москва.ogg) is the capital and largest city of Russia. The city stands on the Moskva River in Central Russia, with a population estimated at 13.0 millio ...

with the 56th Reserve. Tsvetaeva was a close witness of the Russian Revolution, which she rejected. On trains, she came into contact with ordinary Russian people and was shocked by the mood of anger and violence. She wrote in her journal: "In the air of the compartment hung only three axe-like words: bourgeois, Junkers, leeches." After the 1917 Revolution, Efron joined the White Army

The White Army (russian: Белая армия, Belaya armiya) or White Guard (russian: Бѣлая гвардія/Белая гвардия, Belaya gvardiya, label=none), also referred to as the Whites or White Guardsmen (russian: Бѣлогв� ...

, and Marina returned to Moscow hoping to be reunited with her husband. She was trapped in Moscow for five years, where there was a terrible famine.

She wrote six plays in verse and narrative poems. Between 1917 and 1922 she wrote the epic verse cycle ''Lebedinyi stan'' (''The Encampment of the Swans'') about the civil war

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

, glorifying those who fought against the communists. The cycle of poems in the style of a diary or journal begins on the day of Tsar Nicholas II's abdication in March 1917, and ends late in 1920, when the anti-communist White Army was finally defeated. The 'swans' of the title refers to the volunteers in the White Army, in which her husband was fighting as an officer. In 1922, she published a long pro-imperial verse fairy tale, ''Tsar-devitsa'' ("Tsar-Maiden").

The Moscow famine was to exact a toll on Tsvetaeva. With no immediate family to turn to, she had no way to support herself or her daughters. In 1919, she placed both her daughters in a state orphanage, mistakenly believing that they would be better fed there. Alya became ill, and Tsvetaeva removed her, but Irina died there of starvation in 1920. The child's death caused Tsvetaeva great grief and regret. In one letter, she wrote, "God punished me."

During these years, Tsvetaeva maintained a close and intense friendship with the actress Sofia Evgenievna Holliday, for whom she wrote a number of plays. Many years later, she would write the novella "Povest o Sonechke" about her relationship with Holliday.

Exile

Berlin and Prague

In May 1922, Tsvetaeva and Ariadna left

In May 1922, Tsvetaeva and Ariadna left Soviet Russia

The Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, Russian SFSR or RSFSR ( rus, Российская Советская Федеративная Социалистическая Республика, Rossíyskaya Sovétskaya Federatívnaya Soci ...

and were reunited in Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and List of cities in Germany by population, largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's List of cities in the European Union by population within ci ...

with Efron, whom she had thought had been killed by the Bolsheviks."Tsvetaeva, Marina Ivanovna" The Oxford Companion to English Literature. Edited by Dinah Birch. Oxford University Press Inc. There she published the collections ''Separation'', ''Poems to Blok'', and the poem ''The Tsar Maiden'', much of her poetry appeared in Moscow and Berlin, consolidating her reputation. In August 1922, the family moved to Prague

Prague ( ; cs, Praha ; german: Prag, ; la, Praga) is the capital and List of cities in the Czech Republic, largest city in the Czech Republic, and the historical capital of Bohemia. On the Vltava river, Prague is home to about 1.3 milli ...

. Living in unremitting poverty, unable to afford living accommodation in Prague itself, with Efron studying politics and sociology at the Charles University and living in hostels, Tsvetaeva and Ariadna found rooms in a village outside the city. She writes "we are devoured by coal, gas, the milkman, the baker...the only meat we eat is horsemeat". When offered an opportunity to earn money by reading her poetry, she describes having to beg a simple dress from a friend to replace the one she had been living in.Feinstein (1993) px

Tsvetaeva began a passionate affair with , a former military officer, a liaison which became widely known throughout émigré circles. Efron was devastated. Her break-up with Rodziewicz in 1923 was almost certainly the inspiration for her ''The Poem of the End

The ''Poem of the End'' (russian: поэма конца, 'poema kontsa') is the name of two poems by Russian poets of the early 20th century.

Poem of the End (usually given in English without an article) is the best known poem by Russian poet Vas ...

'' and "The Poem of the Mountain". At about the same time, Tsvetaeva began correspondence with poet Rainer Maria Rilke and novelist Boris Pasternak. Tsvetaeva and Pasternak were not to meet for nearly twenty years, but maintained friendship until Tsvetaeva's return to Russia.

In summer 1924, Efron and Tsvetaeva left Prague for the suburbs, living for a while in Jíloviště

Jíloviště is a municipality and village in Prague-West District in the Central Bohemian Region of the Czech Republic

The Czech Republic, or simply Czechia, is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Historically known as Bohemia, i ...

, before moving on to Všenory

Všenory is a municipality and village in Prague-West District in the Central Bohemian Region of the Czech Republic. It has about 1,700 inhabitants.

Notable people

For a period in the 1920s, Všenory was home to the Russian poet Marina Tsvetaeva

...

, where Tsvetaeva completed "The Poem of the End", and was to conceive their son, Georgy, whom she was to later nickname 'Mur'. Tsvetaeva wanted to name him Boris (after Pasternak); Efron insisted on Georgy. He was to be a most difficult child but Tsvetaeva loved him obsessively. With Efron now rarely free from tuberculosis, their daughter Ariadna was relegated to the role of mother's helper and confidante, and consequently felt robbed of much of her childhood. In Berlin, before settling in Paris, Tsvetaeva wrote some of her greatest verse, including ''Remeslo'' ("Craft", 1923) and ''Posle Rossii'' ("After Russia", 1928). Reflecting a life in poverty and exiled, the work holds great nostalgia for Russia and its folk history, while experimenting with verse forms.

Paris

In 1925, the family settled inParis

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), ma ...

, where they would live for the next 14 years. At about this time Tsvetaeva contracted tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease usually caused by '' Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can also affect other parts of the body. Most infections show no symptoms, i ...

. Tsvetaeva received a small stipend from the Czechoslovak government, which gave financial support to artists and writers who had lived in Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

. In addition, she tried to make whatever she could from readings and sales of her work. She turned more and more to writing prose because she found it made more money than poetry. Tsvetaeva did not feel at all at home in Paris's predominantly ex-bourgeois circle of Russian émigré writers. Although she had written passionately pro- 'White' poems during the Revolution, her fellow émigrés thought that she was insufficiently anti-Soviet, and that her criticism of the Soviet régime was altogether too nebulous. She was particularly criticised for writing an admiring letter to the Soviet poet Vladimir Mayakovsky

Vladimir Vladimirovich Mayakovsky (, ; rus, Влади́мир Влади́мирович Маяко́вский, , vlɐˈdʲimʲɪr vlɐˈdʲimʲɪrəvʲɪtɕ məjɪˈkofskʲɪj, Ru-Vladimir Vladimirovich Mayakovsky.ogg, links=y; – 14 Apr ...

. In the wake of this letter, the émigré paper '' Posledniye Novosti'', to which Tsvetaeva had been a frequent contributor, refused point-blank to publish any more of her work.Feinstein (1993) pxi She found solace in her correspondence with other writers, including Boris Pasternak, Rainer Maria Rilke, the Czech poet Anna Tesková, the critics D. S. Mirsky and Aleksandr Bakhrakh, and the Georgian émigré princess Salomea Andronikova, who became her main source of financial support. Her poetry and critical prose of the time, including her autobiographical prose works of 1934–7, is of lasting literary importance. "Consumed by the daily round", resenting the domesticity that left her no time for solitude or writing, her émigré milieu regarded Tsvetaeva as a crude sort who ignored social graces. Describing her misery, she wrote to Tesková "In Paris, with rare personal exceptions, everyone hates me, they write all sorts of nasty things, leave me out in all sorts of nasty ways, and so on". To Pasternak she complained "They don't like poetry and what am I apart from that, not poetry but that from which it is made. aman inhospitable hostess. A young woman in an old dress." She began to look back at even the Prague times with nostalgia and resent her exiled state more deeply.

Meanwhile, Tsvetaeva's husband was developing Soviet sympathies and was homesick for Russia. Eventually, he began working for the NKVD

The People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs (russian: Наро́дный комиссариа́т вну́тренних дел, Naródnyy komissariát vnútrennikh del, ), abbreviated NKVD ( ), was the interior ministry of the Soviet Union.

...

, the forerunner of the KGB

The KGB (russian: links=no, lit=Committee for State Security, Комитет государственной безопасности (КГБ), a=ru-KGB.ogg, p=kəmʲɪˈtʲet ɡəsʊˈdarstvʲɪn(ː)əj bʲɪzɐˈpasnəsʲtʲɪ, Komitet gosud ...

. Alya shared his views, and increasingly turned against her mother. In 1937, she returned to the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

. Later that year, Efron too had to return to the USSR. The French police had implicated him in the murder of the former Soviet defector Ignace Reiss

Ignace Reiss (1899 – 4 September 1937) – also known as "Ignace Poretsky,"

"Ignatz Reiss,"

"Ludwig,"

"Ludwik", "Hans Eberhardt,"

"Steff Brandt,"

Nathan Poreckij,

and "Walter Scott (an officer of the U.S. military intelligence)" ...

in September 1937, on a country lane near Lausanne

, neighboring_municipalities= Bottens, Bretigny-sur-Morrens, Chavannes-près-Renens, Cheseaux-sur-Lausanne, Crissier, Cugy, Écublens, Épalinges, Évian-les-Bains (FR-74), Froideville, Jouxtens-Mézery, Le Mont-sur-Lausanne, Lugrin (FR ...

, Switzerland. After Efron's escape, the police interrogated Tsvetaeva, but she seemed confused by their questions and ended up reading them some French translations of her poetry. The police concluded that she was deranged and knew nothing of the murder. Later it was learned that Efron possibly had also taken part in the assassination of Trotsky's son in 1936. Tsvetaeva does not seem to have known that her husband was a spy, nor the extent to which he was compromised. However, she was held responsible for his actions and was ostracised in Paris because of the implication that he was involved with the NKVD. World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

had made Europe as unsafe and hostile as the USSR. In 1939, she became lonely and alarmed by the rise of fascism, which she attacked in ''Stikhi k Chekhii'' ("Verses to Czechia" 1938–39).

Last years: Return to the Soviet Union

In 1939, she and her son returned to Moscow, unaware of the reception she would receive. In

In 1939, she and her son returned to Moscow, unaware of the reception she would receive. In Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secretar ...

's USSR, anyone who had lived abroad was suspect, as was anyone who had been among the intelligentsia before the Revolution. Tsvetaeva's sister had been arrested before Tsvetaeva's return; although Anastasia survived the Stalin years, the sisters never saw each other again. Tsvetaeva found that all doors had closed to her. She got bits of work translating poetry, but otherwise the established Soviet writers refused to help her, and chose to ignore her plight; Nikolai Aseev, whom she had hoped would assist, shied away, fearful for his life and position.

Efron and Alya were arrested on espionage charges in 1941, Efron was sentenced to death. Alya's fiancé was actually an NKVD

The People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs (russian: Наро́дный комиссариа́т вну́тренних дел, Naródnyy komissariát vnútrennikh del, ), abbreviated NKVD ( ), was the interior ministry of the Soviet Union.

...

agent who had been assigned to spy on the family. Efron was shot in 1941; Alya served over eight years in prison. Both were exonerated after Stalin's death. In 1941, Tsvetaeva and her son were evacuated to Yelabuga

Yelabuga (alternative spelling that reflects the Cyrillic spelling: Elabuga; russian: Елабуга; tt-Cyrl, Алабуга, ''Alabuğa'') is a town in the Republic of Tatarstan, Russia, located on the right bank of the Kama River and east ...

(Elabuga), while most families of the Union of Soviet Writers

The Union of Soviet Writers, USSR Union of Writers, or Soviet Union of Writers (russian: Союз писателей СССР, translit=Soyuz Sovetstikh Pisatelei) was a creative union of professional writers in the Soviet Union. It was founded ...

were evacuated to Chistopol

Chistopol (russian: Чи́стополь; tt-Cyrl, Чистай, ''Çistay''; cv, Чистай, ''Çistay'') is a town in Tatarstan, Russia, located on the left bank of the Kuybyshev Reservoir, on the Kama River. As of the 2010 Census, its p ...

. Tsvetaeva had no means of support in Yelabuga, and on 24 August 1941 she left for Chistopol desperately seeking a job. On 26 August, Marina Tsvetaeva and poet Valentin Parnakh Valentin Yakovlevich Parnakh (russian: Валентин Яковлевич Парнах) (1891–1951) was a Soviet musician and choreographer, who was a founding father of Soviet Union, Soviet jazz. He was also a poet, and translated many foreign w ...

applied to the Soviet of Literature Fund asking for a job at the LitFund's canteen. Parnakh was accepted as a doorman, while Tsvetaeva's application for a permission to live in Chistopol was turned down and she had to return to Yelabuga on 28 August.

On 31 August 1941, while living in Yelabuga, Tsvetaeva hanged herself. She left a note for her son Mur: "Forgive me, but to go on would be worse. I am gravely ill, this is not me anymore. I love you passionately. Do understand that I could not live anymore. Tell Papa and Alya, if you ever see them, that I loved them to the last moment and explain to them that I found myself in a trap."Feiler, Lily (1994). ''Marina Tsvetaeva: the double beat of Heaven and Hell''. Duke University Press. p264

Tsvetaeva was buried in Yelabuga cemetery on 2 September 1941, but the exact location of her grave remains unknown.

Her son Georgy volunteered for the Eastern Front of World War II and died in battle in 1944. Her daughter Ariadna spent 16 years in Soviet prison camps and exile and was released in 1955. Ariadna wrote a memoir of her family; an English-language edition was published in 2009. She died in 1975.

In the town of Yelabuga, the Tsvetaeva house is now a museum and a monument stands to her. The apartment in Moscow where she lived from 1914 to 1922 is now a house-museum. Much of her poetry was republished in the Soviet Union after 1961, and her passionate, articulate and precise work, with its daring linguistic experimentation, brought her increasing recognition as a major poet.

A minor planet

According to the International Astronomical Union (IAU), a minor planet is an astronomical object in direct orbit around the Sun that is exclusively classified as neither a planet nor a comet. Before 2006, the IAU officially used the term ''mino ...

, 3511 Tsvetaeva

3511 (three thousand, five hundred and eleven) is the natural number following 3510 and preceding 3512.

3511 is a prime number, and is also an emirp: a different prime when its digits are reversed.

3511 is a Wieferich prime, found to be so by N ...

, discovered in 1982 by Soviet astronomer Lyudmila Karachkina

Lyudmila Georgievna Karachkina (russian: Людмила Георгиевна Карачкина, born 3 September 1948, Rostov-on-Don) is an astronomer and discoverer of minor planets.

In 1978 she began as a staff astronomer of the Institute for ...

, is named after her.

In 1989, in Gdynia

Gdynia ( ; ; german: Gdingen (currently), (1939–1945); csb, Gdiniô, , , ) is a city in northern Poland and a seaport on the Baltic Sea coast. With a population of 243,918, it is the 12th-largest city in Poland and the second-largest in th ...

, Poland, a special-purpose ship was built for the Russian Academy of Sciences

The Russian Academy of Sciences (RAS; russian: Росси́йская акаде́мия нау́к (РАН) ''Rossíyskaya akadémiya naúk'') consists of the national academy of Russia; a network of scientific research institutes from across ...

and named Marina Tsvetaeva in her honor. From 2007, the ship served as a tourist vessel to the polar regions for Aurora Expeditions. In 2011, she was renamed and is currently operated by Oceanwide Expeditions as a tourist vessel in the polar regions.

Work

Tsvetaeva's poetry was admired by poets such asValery Bryusov

Valery Yakovlevich Bryusov ( rus, Вале́рий Я́ковлевич Брю́сов, p=vɐˈlʲerʲɪj ˈjakəvlʲɪvʲɪdʑ ˈbrʲusəf, a=Valyeriy Yakovlyevich Bryusov.ru.vorb.oga; – 9 October 1924) was a Russian poet, prose writer, drama ...

, Maximilian Voloshin

Maximilian Alexandrovich Kirienko-Voloshin (russian: Максимилиа́н Алекса́ндрович Кирие́нко-Воло́шин; May 28, Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates">O.S._May_16.html" ;"title="Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ...

, Osip Mandelstam

Osip Emilyevich Mandelstam ( rus, Осип Эмильевич Мандельштам, p=ˈosʲɪp ɨˈmʲilʲjɪvʲɪtɕ mənʲdʲɪlʲˈʂtam; – 27 December 1938) was a Russian and Soviet poet. He was one of the foremost members of the A ...

, Boris Pasternak, Rainer Maria Rilke, and Anna Akhmatova

Anna Andreyevna Gorenko rus, А́нна Андре́евна Горе́нко, p=ˈanːə ɐnˈdrʲe(j)ɪvnə ɡɐˈrʲɛnkə, a=Anna Andreyevna Gorenko.ru.oga, links=yes; uk, А́нна Андрі́ївна Горе́нко, Ánna Andríyivn ...

. Later, that recognition was also expressed by the poet Joseph Brodsky, pre-eminent among Tsvetaeva's champions. Tsvetaeva was primarily a lyrical poet, and her lyrical voice remains clearly audible in her narrative poetry. Brodsky said of her work: "Represented on a graph, Tsvetaeva's work would exhibit a curve – or rather, a straight line – rising at almost a right angle because of her constant effort to raise the pitch a note higher, an idea higher (or, more precisely, an octave and a faith higher.) She always carried everything she has to say to its conceivable and expressible end. In both her poetry and her prose, nothing remains hanging or leaves a feeling of ambivalence. Tsvetaeva is the unique case in which the paramount spiritual experience of an epoch (for us, the sense of ambivalence, of contradictoriness in the nature of human existence) served not as the object of expression but as its means, by which it was transformed into the material of art." Critic Annie Finch

Annie Finch (born October 31, 1956) is an American poet, critic, editor, translator, playwright, and performer and the editor of the first major anthology of literature about abortion. Her poetry is known for its often incantatory use of rhythm, ...

describes the engaging, heart-felt nature of the work. "Tsvetaeva is such a warm poet, so unbridled in her passion, so completely vulnerable in her love poetry, whether to her female lover Sofie Parnak, to Boris Pasternak. ..Tsvetaeva throws her poetic brilliance on the altar of her heart’s experience with the faith of a true romantic, a priestess of lived emotion. And she stayed true to that faith to the tragic end of her life.

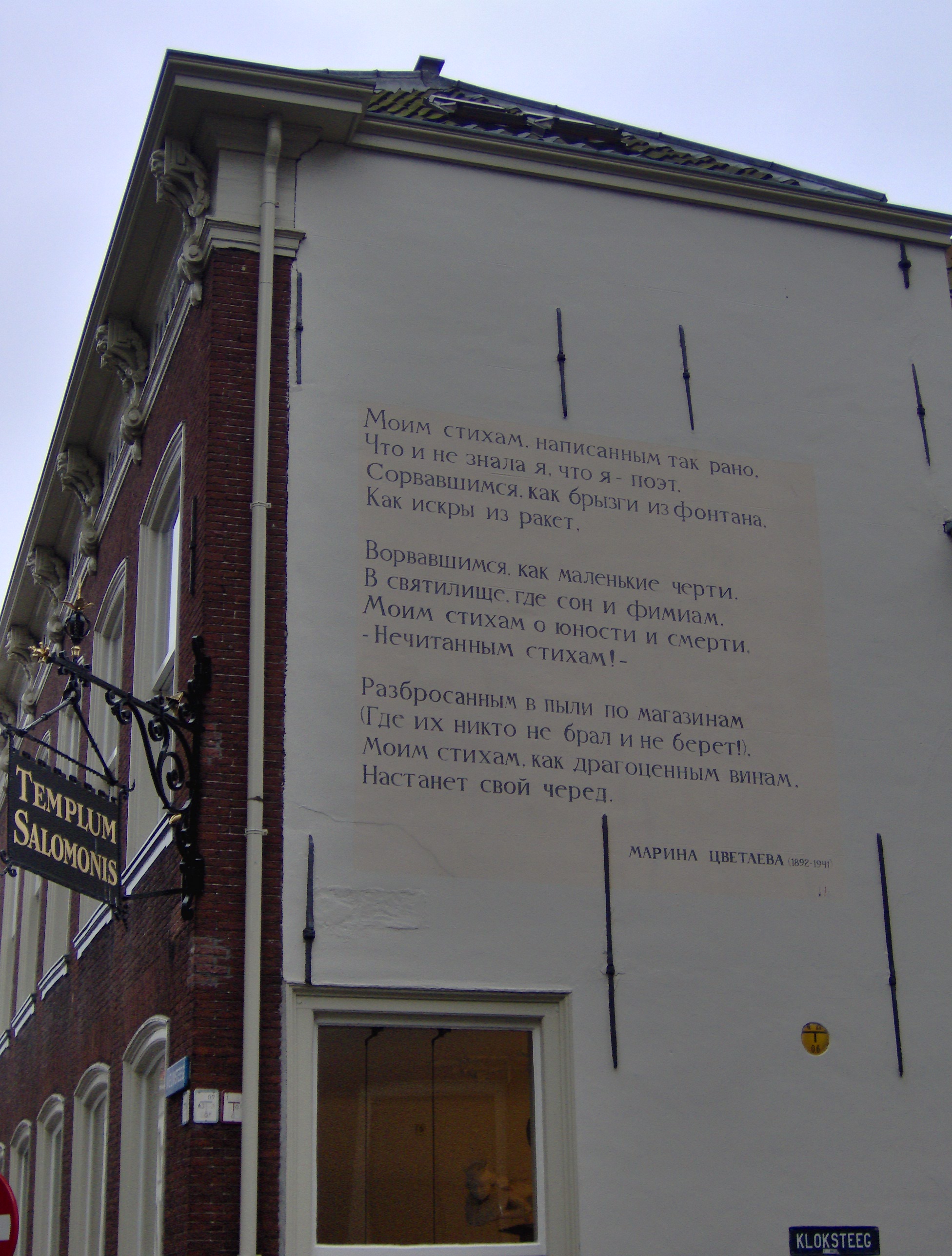

Tsvetaeva's lyric poems fill ten collections; the uncollected lyrics would add at least another volume. Her first two collections indicate their subject matter in their titles: ''Evening Album'' (Vecherniy albom, 1910) and ''The Magic Lantern'' (Volshebnyi fonar, 1912). The poems are vignettes of a tranquil childhood and youth in a professorial, middle-class home in Moscow, and display considerable grasp of the formal elements of style. The full range of Tsvetaeva's talent developed quickly, and was undoubtedly influenced by the contacts she had made at Koktebel, and was made evident in two new collections: ''Mileposts'' (Versty, 1921) and ''Mileposts: Book One'' (Versty, Vypusk I, 1922).

Three elements of Tsvetaeva's mature style emerge in the ''Mileposts'' collections. First, Tsvetaeva dates her poems and publishes them chronologically. The poems in ''Mileposts: Book One'', for example, were written in 1916 and resolve themselves as a versified journal. Secondly, there are cycles of poems which fall into a regular chronological sequence among the single poems, evidence that certain themes demanded further expression and development. One cycle announces the theme of ''Mileposts: Book One'' as a whole: the "Poems of Moscow." Two other cycles are dedicated to poets, the "Poems to Akhmatova" and the "Poems to Blok", which again reappear in a separate volume, Poems to Blok (''Stikhi k Bloku'', 1922). Thirdly, the ''Mileposts'' collections demonstrate the dramatic quality of Tsvetaeva's work, and her ability to assume the guise of multiple ''dramatis personae'' within them.

The collection ''Separation'' (Razluka, 1922) was to contain Tsvetaeva's first long verse narrative, "On a Red Steed" ("Na krasnom kone"). The poem is a prologue to three more verse-narratives written between 1920 and 1922. All four narrative poems draw on folkloric plots. Tsvetaeva acknowledges her sources in the titles of the very long works, ''The Maiden Tsar

''The Maiden Tsar'' (russian: Царь-девица) is a Russian folktale. It appeared in print in Alexander Afanasyev's three-volume collection ''Narodnye russkie skazki'', numbered 232 and 233.

Synopsis

A merchant and his wife have a son wh ...

: A Fairy-tale Poem'' (''Tsar-devitsa: Poema-skazka'', 1922) and "The Swain", subtitled "A Fairytale" ("Molodets: skazka", 1924). The fourth folklore-style poem is "Byways" ("Pereulochki", published in 1923 in the collection ''Remeslo''), and it is the first poem which may be deemed incomprehensible in that it is fundamentally a soundscape of language. The collection ''Psyche'' (''Psikheya'', 1923) contains one of Tsvetaeva's best-known cycles "Insomnia" (Bessonnitsa) and the poem The Swans' Encampment (Lebedinyi stan, Stikhi 1917–1921, published in 1957) which celebrates the White Army

The White Army (russian: Белая армия, Belaya armiya) or White Guard (russian: Бѣлая гвардія/Белая гвардия, Belaya gvardiya, label=none), also referred to as the Whites or White Guardsmen (russian: Бѣлогв� ...

.

Emigrant

Subsequently, as an émigré, Tsvetaeva's last two collections of lyrics were published by émigré presses, ''Craft'' (''Remeslo'', 1923) in Berlin and ''After Russia'' (''Posle Rossii'', 1928) in Paris. There then followed the twenty-three lyrical "Berlin" poems, the pantheistic "Trees" ("Derev'ya"), "Wires" ("Provoda") and "Pairs" ("Dvoe"), and the tragic "Poets" ("Poety"). "After Russia" contains the poem "In Praise of the Rich", in which Tsvetaeva's oppositional tone is merged with her proclivity for ruthless satire.

Satire

The satirist in Tsvetaeva plays second fiddle only to the poet-lyricist. Several satirical poems, moreover, are among Tsvetaeva's best-known works: "The Train of Life" ("Poezd zhizni") and "The Floorcleaners' Song" ("Poloterskaya"), both included in After Russia, and The Ratcatcher (Krysolov, 1925–1926), a long, folkloric narrative. The target of Tsvetaeva's satire is everything petty and petty bourgeois. Unleashed against such dull creature comforts is the vengeful, unearthly energy of workers both manual and creative. In her notebook, Tsvetaeva writes of "The Floorcleaners' Song": "Overall movement: the floorcleaners ferret out a house's hidden things, they scrub a fire into the door... What do they flush out? Coziness, warmth, tidiness, order... Smells: incense, piety. Bygones. Yesterday... The growing force of their threat is far stronger than the climax." ''The Ratcatcher'' poem, which Tsvetaeva describes as a ''lyrical satire'', is loosely based on the legend of the Pied Piper of Hamelin. The Ratcatcher, which is also known as The Pied Piper, is considered by some to be the finest of Tsvetaeva's work. It was also partially an act of ''homage'' to Heinrich Heine's poem ''Die Wanderratten''. The Ratcatcher appeared initially, in serial format, in the émigré journal ' in 1925–1926 whilst still being written. It was not to appear in the Soviet Union until after thedeath of Joseph Stalin

Death is the irreversible cessation of all biological functions that sustain an organism. For organisms with a brain, death can also be defined as the irreversible cessation of functioning of the whole brain, including brainstem, and brain ...

in 1956. Its hero is the Pied Piper of Hamelin who saves a town from hordes of rats and then leads the town's children away too, in retribution for the citizens' ingratitude. As in the other folkloric narratives, The Ratcatcher's story line emerges indirectly through numerous speaking voices which shift from invective, to extended lyrical flights, to pathos.

Translators

Translators of Tsvetaeva's work into English includeElaine Feinstein

Elaine Feinstein FRSL (born Elaine Cooklin; 24 October 1930 – 23 September 2019) was an English poet, novelist, short-story writer, playwright, biographer and translator. She joined the Council of the Royal Society of Literature in 2007.

Earl ...

and David McDuff

David McDuff (born 1945, Sale, Cheshire, England) is a Scottish translator, editor and literary critic.

Life

McDuff attended the University of Edinburgh, where he studied Russian and German, gaining a PhD in 1971. He married mathematician Dus ...

. Nina Kossman translated many of Tsvetaeva's long (narrative) poems, as well as her lyrical poems; they are collected in three books, ''Poem of the End'' (bilingual edition published by Ardis in 1998, by Overlook in 2004, and by Shearsman Books in 2021), ''In the Inmost Hour of the Soul'' (Humana Press, 1989), and ''Other Shepherds'' (Poets & Traitors Press, 2020). Robin Kemball translated the cycle ''The Demesne of the Swans'', published as a separate (bilingual) book by Ardis in 1980. J. Marin King translated a great deal of Tsvetaeva's prose into English, compiled in a book called ''A Captive Spirit''. Tsvetaeva scholar Angela Livingstone has translated a number of Tsvetaeva's essays on art and writing, compiled in a book called ''Art in the Light of Conscience''. Livingstone's translation of Tsvetaeva's "The Ratcatcher" was published as a separate book. Mary Jane White has translated the early cycle "Miles" in a book called "Starry Sky to Starry Sky", as well as Tsvetaeva's elegy for Rilke, "New Year's", (Adastra Press 16 Reservation Road, Easthampton, MA 01027 USA) and "Poem of the End" (The Hudson Review, Winter 2009; and in the anthology Poets Translate Poets, Syracuse U. Press 2013) and "Poem of the Hill", (New England Review, Summer 2008) and Tsvetaeva's 1914–1915 cycle of love poems to Sophia Parnok. In 2002, Yale University Press

Yale University Press is the university press of Yale University. It was founded in 1908 by George Parmly Day, and became an official department of Yale University in 1961, but it remains financially and operationally autonomous.

, Yale Universi ...

published Jamey Gambrell

Jamey Gambrell (April 10, 1954 – February 15, 2020) was an American translator of Russian literature, and an expert in modern art. She was an editor with the '' Art in America'' magazine, and was a winner of the Thornton Wilder Prize for Trans ...

's translation of post-revolutionary prose, entitled ''Earthly Signs: Moscow Diaries, 1917–1922'', with notes on poetic and linguistic aspects of Tsvetaeva's prose, and endnotes for the text itself.

Cultural influence

* 2017: ''Zerkalo'' ("Mirror"), American magazine in MN for the Russian-speaking readers. It was a special publication to the 125th Anniversary of the Russian poet Marina Tsvetaeva, where the article "Marina Tsvetaeva in America" was written by Dr. Uli Zislin, the founder and director of the Washington Museum of Russian Poetry and Music, Sep/Oct 2017.Music and songs

The Soviet composer Dmitri Shostakovich set six of Tsvetaeva's poems to music. Later the Russian-Tatar composer Sofia Gubaidulina wrote an ''Hommage à Marina Tsvetayeva'' featuring her poems. Her poem "Mne Nravitsya..." ("I like that..."), was performed byAlla Pugacheva

Alla Borisovna Pugacheva, ) (born 15 April 1949), is а Soviet and Russian musical performer. Her career started in 1965 and continues to this day, even though she has retired from performing. For her "clear mezzo-soprano and a full display o ...

in the film ''The Irony of Fate

''The Irony of Fate, or Enjoy Your Bath!'' (russian: Ирония судьбы, или С лёгким паром!, literally: The Irony of Fate, or With A Light Steam; trans. ''Ironiya sudby, ili S lyogkim parom!''), usually shortened to ''The ...

''. In 2003, the opera ''Marina: A Captive Spirit'', based on Tsvetaeva's life and work, premiered from American Opera Projects The American Opera Project (AOP) is a professional opera company based in Brooklyn, New York City, and is a member of Opera America, the Fort Greene Association, the Downtown Brooklyn Arts Alliance, and the Alliance of Resident Theatres/New York (A. ...

in New York with music by Deborah Drattell and libretto by poet Annie Finch

Annie Finch (born October 31, 1956) is an American poet, critic, editor, translator, playwright, and performer and the editor of the first major anthology of literature about abortion. Her poetry is known for its often incantatory use of rhythm, ...

. The production was directed by Anne Bogart

Anne Bogart (born September 25, 1951) is an American theatre and opera director. She is currently one of the Artistic Directors of SITI Company, which she founded with Japanese director Tadashi Suzuki in 1992. She is a professor at Columbia Uni ...

and the part of Tsvetaeva was sung by Lauren Flanigan. The poetry by Tsvetaeva was set to music and frequently performed as songs by Elena Frolova, Larisa Novoseltseva

Larisa Novoseltseva (russian: link=no, Лариса Новосельцева) is a Russian singer-songwriter, composer, performer of Russian and Ukrainian folk songs and romances, and creator of project ''Return of the Silver Age''. She is author ...

, Zlata Razdolina

Zlata Razdolina (Rozenfeld, russian: Злата Абрамовна Раздолина) is a Russian Jewish composer, singer-songwriter and music performer. She is best known as being the author of the music for Requiem by Anna Akhmatova, ''The Son ...

and other Russian bards

The term bard ( rus, бард, p=bart) came to be used in the Soviet Union in the early 1960s, and continues to be used in Russia today, to refer to singer-songwriters who wrote songs outside the Soviet establishment, similarly to folk sin ...

. In 2019, American composer Mark Abel

Mark Abel (born April 28, 1948) is an American composer of classical music.

Background

After a brief stay at Stanford University in the late 1960s, Abel was active on the New York rock scene during the 1970s and early 1980s, leading his own gro ...

wrote ''Four Poems of Marina Tsvetaeva'', the first classical song cycle of the poet in an English translation. Soprano Hila Plitmann recorded the piece for Abel’s album ''The Cave of Wondrous Voice''.

Tribute

On 8 October 2015,Google Doodle

A Google Doodle is a special, temporary alteration of the logo on Google's homepages intended to commemorate holidays, events, achievements, and notable historical figures. The first Google Doodle honored the 1998 edition of the long-running an ...

commemorated her 123rd birthday.

Translations into English

* ''Selected Poems'', trans.Elaine Feinstein

Elaine Feinstein FRSL (born Elaine Cooklin; 24 October 1930 – 23 September 2019) was an English poet, novelist, short-story writer, playwright, biographer and translator. She joined the Council of the Royal Society of Literature in 2007.

Earl ...

. (Oxford University Press, 1971; 2nd ed., 1981; 3rd ed., 1986; 4th ed., 1993; 5th ed., 1999; 6th ed. 2009 as ''Bride of Ice: New Selected Poems'')

* ''The Demesne of the Swans'', trans. Robin Kemball (bilingual edition, Ardis, 1980) ISBN 978-0882334936

*''Marina Tsvetayeva: Selected Poems'', trans. David McDuff

David McDuff (born 1945, Sale, Cheshire, England) is a Scottish translator, editor and literary critic.

Life

McDuff attended the University of Edinburgh, where he studied Russian and German, gaining a PhD in 1971. He married mathematician Dus ...

. (Bloodaxe Books, 1987)

*"Starry Sky to Starry Sky (Miles)", trans. Mary Jane White. (Holy Cow! Press

Holy Cow! Press is an independent publisher based in Duluth, Minnesota. Founded in 1977, they have published more than 125 books.

The press publishes between three and five new books each year, in genres including poetry, fiction, memoir, and b ...

, 1988), (paper) and (cloth)

*''In the Inmost Hour of the Soul: Poems by Marina Tsvetayeva '', trans. Nina Kossman (Humana Press, 1989)

*''Black Earth'', trans. Elaine Feinstein (The Delos Press and The Menard Press, 1992) ISBN I-874320-00-4 and ISBN I-874320-05-5 (signed ed.)

*"After Russia", trans. Michael Nayden (Ardis, 1992).

* ''A Captive Spirit: Selected Prose'', trans. J. Marin King (Vintage Books, 1994)

*''Poem of the End: Selected Narrative and Lyrical Poems '', trans. Nina Kossman (Ardis / Overlook, 1998, 2004) ; Poem of the End: Six Narrative Poems, trans. Nina Kossman (Shearsman Books, 2021) ISBN 978-1-84861-778-0)

*''The Ratcatcher: A Lyrical Satire'', trans. Angela Livingstone (Northwestern University, 2000)

*''Letters: Summer 1926'' (Boris Pasternak, Marina Tsvetayeva, Rainer Maria Rilke) (New York Review Books, 2001)

* ''Earthly Signs: Moscow Diaries, 1917–1922'', ed. & trans. Jamey Gambrell (Yale University Press, 2002)

*''Phaedra: a drama in verse; with New Year's Letter and other long poems'', trans. Angela Livingstone (Angel Classics, 2012)

*"To You – in 10 Decades", trans. by Alexander Givental

Alexander Givental (russian: Александр Борисович Гивенталь) is a Russian-American mathematician working in symplectic topology and singularity theory, as well as their relation to topological string theories. He graduat ...

and Elysee Wilson-Egolf (Sumizdat 2012)

*''Moscow in the Plague Year'', translated by Christopher Whyte (180 poems written between November 1918 and May 1920) (Archipelago Press, New York, 2014), 268pp,

*''Milestones (1922),'' translated by Christopher Whyte (Bristol, Shearsman Books, 2015), 122p,

*''After Russia: The First Notebook,'' translated by Christopher Whyte (Bristol, Shearsman Books, 2017), 141 pp,

*''After Russia: The Second Notebook'', translated by Christopher Whyte (Bristol, Shearsman Books, 2018) 121 pp,

*"Poem of the End" in "From A Terrace in Prague, A Prague Poetry Anthology", trans. Mary Jane White, ed. Stephan Delbos (Univerzita Karlova v Praze, 2011)

*''Youthful Verses'', translated by Christopher Whyte (Bristol, Shearsman Books, 2021), 114 pp, ISBN 9781848617315

*''Head on a Gleaming Plate: Poems 1917-1918'', translated by Christopher Whyte (Bristol, Shearsman Books, 2022), 120 pp, ISBN 9781848618435

*''Poems'', trans. Alyssa Gillespie (Columbia University Press, forthcoming)

Further reading

* Schweitzer, Viktoria ''Tsvetaeva'' (1993) * Mandelstam, Nadezhda ''Hope Against Hope'' * Mandelstam, Nadezhda ''Hope Abandoned'' * Pasternak, Boris ''An Essay in Autobiography''References

External links

* . One of the most famous Tsvetaeva's poem performed byAlla Pugacheva

Alla Borisovna Pugacheva, ) (born 15 April 1949), is а Soviet and Russian musical performer. Her career started in 1965 and continues to this day, even though she has retired from performing. For her "clear mezzo-soprano and a full display o ...

Another version

* . Dramatic reading in English with artistic video. Includes download link.

"Marina Tsvetaeva, ''Poet of the extreme''"

by Belinda Cooke from ''South'' magazine #31, April 2005. Republished online in the

Poetry Library

The National Poetry Library is a free public collection housed at Royal Festival Hall in London's Southbank Centre. Situated on the fifth floor of the Royal Festival Hall, overlooking the river Thames, the library aims to hold all contemporar ...

's Poetry Magazines site.

A small site dedicated to Tsvetaeva

Marina Tsvetaeva biography

at Carcanet Press, English language publisher of Tsvetaeva's ''Bride of Ice'' and ''Marina Tsvetaeva: Selected Poems'', translated by

Elaine Feinstein

Elaine Feinstein FRSL (born Elaine Cooklin; 24 October 1930 – 23 September 2019) was an English poet, novelist, short-story writer, playwright, biographer and translator. She joined the Council of the Royal Society of Literature in 2007.

Earl ...

.

Heritage of Marina Tsvetayeva

a resource in English wit

a more extensive version in Russian

Тоска по родине / Nostalgia

an

four more poems

from the book "To You – in 10 Decades", translated by

Alexander Givental

Alexander Givental (russian: Александр Борисович Гивенталь) is a Russian-American mathematician working in symplectic topology and singularity theory, as well as their relation to topological string theories. He graduat ...

and Elysee Wilson-Egolf and provided by Sumizdat, the publisher.

"She Means It When She Rhymes: ''Marina Tsvetaeva: Selected Poems''."

Review from ''Thumbscrew'' #17, Winter 2000/1, of works translated by Elaine Feinstein.

The Poems

by Marina Tsvetaeva {{DEFAULTSORT:Tsvetaeva, Marina 1892 births 1941 suicides 20th-century Russian women writers Poets from the Russian Empire Soviet emigrants to Germany German emigrants to Czechoslovakia Diarists from the Russian Empire Women poets from the Russian Empire Suicides by hanging in the Soviet Union University of Paris alumni Women diarists Writers from Moscow Russian LGBT poets 20th-century Russian poets 20th-century Russian diarists Soviet diarists 20th-century LGBT people Soviet women poets Female suicides