Trinity College, Cambridge on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Trinity College is a constituent college of the

The monastic lands granted by

The monastic lands granted by

In the 20th century, Trinity College, St John's College and King's College were for decades the main recruiting grounds for the Cambridge Apostles, an elite, intellectual secret society. In 2011, the John Templeton Foundation awarded Trinity College's Master, the astrophysicist Martin Rees, its controversial million-pound

In the 20th century, Trinity College, St John's College and King's College were for decades the main recruiting grounds for the Cambridge Apostles, an elite, intellectual secret society. In 2011, the John Templeton Foundation awarded Trinity College's Master, the astrophysicist Martin Rees, its controversial million-pound

Nevile's Court (built 1614) is located between Great Court and the river, this court was created by a bequest by the college's master, Thomas Nevile, originally two-thirds of its current length and without the Wren Library. The court was extended and the appearance of the upper floor remodelled slightly in 1758 by James Essex. Cloisters run around the court, providing sheltered walkways from the rear of Great Hall to the college library and reading room as well as the Wren Library and New Court.

Nevile's Court (built 1614) is located between Great Court and the river, this court was created by a bequest by the college's master, Thomas Nevile, originally two-thirds of its current length and without the Wren Library. The court was extended and the appearance of the upper floor remodelled slightly in 1758 by James Essex. Cloisters run around the court, providing sheltered walkways from the rear of Great Hall to the college library and reading room as well as the Wren Library and New Court.

The Wren Library (built 1676–1695,

The Wren Library (built 1676–1695,

File:TrinityCollegeCamGreatGate.jpg, Great Gate

File:Clock Tower, Great Court, Trinity College, Cambridge.jpg, Clock Tower

File:ISH WC Trinity2.jpg, Fellows' Bowling Green, with the oldest building in the college in the background.

File:cmglee_Cambridge_Trinity_College_Old_Kitchen.jpg, Old Kitchen set up for a formal dinner.

File:cmglee_Cambridge_Trinity_College_New_Court_doorway.jpg, New Court after 2016 refurbishment.

File:River Cam green.JPG, The River Cam as it flows past the back of Trinity, Trinity Bridge is visible and the punt house is to the right of the moored punts.

File:cmglee_Cambridge_Trinity_College_avenue.jpg, The Avenue of lime and cherry trees, and wrought iron gate to Queen's Road viewed from the Backs.

File:cmglee_Cambridge_Trinity_College_Fellows_Garden_sundial_shelter.jpg, Sundial and shelter at the Fellows' Garden.

File:cmglee_Cambridge_Trinity_College_Burrells_Field_axis.jpg, 1995 development of Burrell's Field.

File:cmglee_Cambridge_Trinity_College_Blue_Boar_Court.jpg, Blue Boar Court, with the Wolfson Building in the background.

The Scholars, together with the Master and Fellows, make up the Foundation of the College. In order of seniority:

* Research Scholars receive funding for graduate studies. Typically, one must graduate in the top ten percent of one's class and continue for graduate study at Trinity. They are given first preference in the assignment of college rooms and number approximately 25.

* The Senior Scholars usually consist of those who attain a degree with First Class honours or higher in any year after the first of an undergraduate

The Scholars, together with the Master and Fellows, make up the Foundation of the College. In order of seniority:

* Research Scholars receive funding for graduate studies. Typically, one must graduate in the top ten percent of one's class and continue for graduate study at Trinity. They are given first preference in the assignment of college rooms and number approximately 25.

* The Senior Scholars usually consist of those who attain a degree with First Class honours or higher in any year after the first of an undergraduate

Each evening before dinner, grace is recited by the senior fellow presiding, as follows:

If both of the two high tables are in use then the following antiphonal formula is prefixed to the main grace:

Following the meal, the simple formula is pronounced.

Each evening before dinner, grace is recited by the senior fellow presiding, as follows:

If both of the two high tables are in use then the following antiphonal formula is prefixed to the main grace:

Following the meal, the simple formula is pronounced.

The Parish of the Ascension Burial Ground in Cambridge contains the graves of 27 Fellows of Trinity College, Cambridge most of whom are also commemorated in Trinity College Chapel with brass plaques.

The Parish of the Ascension Burial Ground in Cambridge contains the graves of 27 Fellows of Trinity College, Cambridge most of whom are also commemorated in Trinity College Chapel with brass plaques.

This list includes winners of the

This list includes winners of the

The head of Trinity College is called the Master. The role is a Crown appointment, formally made by the monarch on the advice of the prime minister. Nowadays, the fellows of the college propose a new master for the appointment, but the decision is formally that of the Crown. The first Master, John Redman, was appointed in 1546. Six masters subsequent to Rab Butler had been fellows of the college prior to becoming master ( honorary fellow in the case of Martin Rees), the last of these being Sir Gregory Winter, appointed on 2 October 2012. He was succeeded by Dame Sally Davies, the first female Master of Trinity College, on 8 October 2019.

The head of Trinity College is called the Master. The role is a Crown appointment, formally made by the monarch on the advice of the prime minister. Nowadays, the fellows of the college propose a new master for the appointment, but the decision is formally that of the Crown. The first Master, John Redman, was appointed in 1546. Six masters subsequent to Rab Butler had been fellows of the college prior to becoming master ( honorary fellow in the case of Martin Rees), the last of these being Sir Gregory Winter, appointed on 2 October 2012. He was succeeded by Dame Sally Davies, the first female Master of Trinity College, on 8 October 2019.

Trinity College, Cambridge official website

Trinity College, Cambridge Access website

Trinity College Isaac Newton Trust

established in 1988

Paintings at Trinity College, Cambridge

ArtUK project. {{coord, 52.2070, 0.1146, type:landmark, name=Trinity College, format=dms, display=title Henry VIII Catherine Parr 1546 establishments in England Colleges of the University of Cambridge Educational institutions established in the 1540s Grade I listed buildings in Cambridge Grade I listed educational buildings Edward Blore buildings

University of Cambridge

The University of Cambridge is a Public university, public collegiate university, collegiate research university in Cambridge, England. Founded in 1209, the University of Cambridge is the List of oldest universities in continuous operation, wo ...

. Founded in 1546 by King Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is known for his Wives of Henry VIII, six marriages and his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. ...

, Trinity is one of the largest Cambridge colleges, with the largest financial endowment

A financial endowment is a legal structure for managing, and in many cases indefinitely perpetuating, a pool of Financial instrument, financial, real estate, or other investments for a specific purpose according to Donor intent, the will of its fo ...

of any college at Oxford or Cambridge. Trinity has some of the most distinctive architecture in Cambridge with its Great Court said to be the largest enclosed courtyard in Europe. Academically, Trinity performs exceptionally as measured by the Tompkins Table (the annual unofficial league table of Cambridge colleges), coming top from 2011 to 2017, and regaining the position in 2024.

Members of Trinity have been awarded 34 Nobel Prizes out of the 121 received by members of the University of Cambridge (more than any other Oxford or Cambridge college). Members of the college have received four Fields Medal

The Fields Medal is a prize awarded to two, three, or four mathematicians under 40 years of age at the International Congress of Mathematicians, International Congress of the International Mathematical Union (IMU), a meeting that takes place e ...

s, one Turing Award

The ACM A. M. Turing Award is an annual prize given by the Association for Computing Machinery (ACM) for contributions of lasting and major technical importance to computer science. It is generally recognized as the highest distinction in the fi ...

and one Abel Prize. Trinity alumni include Francis Bacon

Francis Bacon, 1st Viscount St Alban (; 22 January 1561 – 9 April 1626) was an English philosopher and statesman who served as Attorney General and Lord Chancellor of England under King James I. Bacon argued for the importance of nat ...

, six British prime ministers

A prime minister or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. A prime minister is not the head of state, but rat ...

(the highest number of any Cambridge college), physicists Isaac Newton

Sir Isaac Newton () was an English polymath active as a mathematician, physicist, astronomer, alchemist, theologian, and author. Newton was a key figure in the Scientific Revolution and the Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment that followed ...

, James Clerk Maxwell

James Clerk Maxwell (13 June 1831 – 5 November 1879) was a Scottish physicist and mathematician who was responsible for the classical theory of electromagnetic radiation, which was the first theory to describe electricity, magnetism an ...

, Ernest Rutherford

Ernest Rutherford, 1st Baron Rutherford of Nelson (30 August 1871 – 19 October 1937) was a New Zealand physicist who was a pioneering researcher in both Atomic physics, atomic and nuclear physics. He has been described as "the father of nu ...

and Niels Bohr

Niels Henrik David Bohr (, ; ; 7 October 1885 – 18 November 1962) was a Danish theoretical physicist who made foundational contributions to understanding atomic structure and old quantum theory, quantum theory, for which he received the No ...

, mathematicians Srinivasa Ramanujan and Charles Babbage

Charles Babbage (; 26 December 1791 – 18 October 1871) was an English polymath. A mathematician, philosopher, inventor and mechanical engineer, Babbage originated the concept of a digital programmable computer.

Babbage is considered ...

, poets Lord Byron

George Gordon Byron, 6th Baron Byron (22 January 1788 – 19 April 1824) was an English poet. He is one of the major figures of the Romantic movement, and is regarded as being among the greatest poets of the United Kingdom. Among his best-kno ...

and Lord Tennyson, English jurist Edward Coke

Sir Edward Coke ( , formerly ; 1 February 1552 – 3 September 1634) was an English barrister, judge, and politician. He is often considered the greatest jurist of the Elizabethan era, Elizabethan and Jacobean era, Jacobean eras.

Born into a ...

, writers Vladimir Nabokov

Vladimir Vladimirovich Nabokov ( ; 2 July 1977), also known by the pen name Vladimir Sirin (), was a Russian and American novelist, poet, translator, and entomologist. Born in Imperial Russia in 1899, Nabokov wrote his first nine novels in Rus ...

and A. A. Milne, historians Lord Macaulay and G. M. Trevelyan, and philosophers Ludwig Wittgenstein

Ludwig Josef Johann Wittgenstein ( ; ; 26 April 1889 – 29 April 1951) was an Austrian philosopher who worked primarily in logic, the philosophy of mathematics, the philosophy of mind, and the philosophy of language.

From 1929 to 1947, Witt ...

and Bertrand Russell

Bertrand Arthur William Russell, 3rd Earl Russell, (18 May 1872 – 2 February 1970) was a British philosopher, logician, mathematician, and public intellectual. He had influence on mathematics, logic, set theory, and various areas of analytic ...

(who the college expelled before reaccepting). Two members of the British royal family

The British royal family comprises Charles III and other members of his family. There is no strict legal or formal definition of who is or is not a member, although the Royal Household has issued different lists outlining who is considere ...

have studied at Trinity and been awarded degrees: Prince William of Gloucester and Edinburgh, who gained an MA in 1790, and King Charles III

Charles III (Charles Philip Arthur George; born 14 November 1948) is King of the United Kingdom and the 14 other Commonwealth realms.

Charles was born at Buckingham Palace during the reign of his maternal grandfather, King George VI, and ...

, who was awarded a lower second class BA in 1970.

Trinity's many college societies include the Trinity Mathematical Society, the oldest mathematical university society in the United Kingdom, and the First and Third Trinity Boat Club, its rowing club, which gives its name to the May Ball. Along with Christ's, Jesus

Jesus (AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ, Jesus of Nazareth, and many Names and titles of Jesus in the New Testament, other names and titles, was a 1st-century Jewish preacher and religious leader. He is the Jesus in Chris ...

, King's and St John's colleges, it has provided several well-known members of the Cambridge Apostles, an intellectual secret society

A secret society is an organization about which the activities, events, inner functioning, or membership are concealed. The society may or may not attempt to conceal its existence. The term usually excludes covert groups, such as intelligence ag ...

. In 1848, Trinity hosted the meeting at which Cambridge undergraduates representing fee-paying private schools codified the early rules of association football

Association football, more commonly known as football or soccer, is a team sport played between two teams of 11 Football player, players who almost exclusively use their feet to propel a Ball (association football), ball around a rectangular f ...

, known as the Cambridge rules

The Cambridge Rules were several formulations of the rules of football made at the University of Cambridge during the nineteenth century.

Cambridge Rules are believed to have had a significant influence on the modern football codes. The 1856 C ...

. Trinity's sister college is Christ Church, Oxford

Christ Church (, the temple or house, ''wikt:aedes, ædes'', of Christ, and thus sometimes known as "The House") is a Colleges of the University of Oxford, constituent college of the University of Oxford in England. Founded in 1546 by Henry V ...

. Trinity has been linked with Westminster School

Westminster School is a Public school (United Kingdom), public school in Westminster, London, England, in the precincts of Westminster Abbey. It descends from a charity school founded by Westminster Benedictines before the Norman Conquest, as do ...

since the school's re-foundation in 1560, and its Master is an ''ex officio'' governor of the school.

History

Foundation

The college was founded byHenry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is known for his Wives of Henry VIII, six marriages and his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. ...

in 1546 with the name ''College of the Holy and Undivided Trinity within the Town and University of Cambridge of King Henry the Eighth's Foundation'', from the merger of two existing colleges: Michaelhouse (founded by Hervey de Stanton in 1324), and King's Hall (established by Edward II in 1317 and refounded by Edward III

Edward III (13 November 1312 – 21 June 1377), also known as Edward of Windsor before his accession, was King of England from January 1327 until his death in 1377. He is noted for his military success and for restoring royal authority after t ...

in 1337). At the time, Henry had been seizing (Catholic) church lands from abbeys and monasteries. The universities of Oxford

Oxford () is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city and non-metropolitan district in Oxfordshire, England, of which it is the county town.

The city is home to the University of Oxford, the List of oldest universities in continuou ...

and Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a List of cities in the United Kingdom, city and non-metropolitan district in the county of Cambridgeshire, England. It is the county town of Cambridgeshire and is located on the River Cam, north of London. As of the 2021 Unit ...

, being both religious institutions and quite rich, expected to be next in line. The King duly passed an Act of Parliament that allowed him to suppress (and confiscate the property of) any college he wished. The universities used their contacts to plead with his sixth wife, Catherine Parr. The Queen persuaded her husband not to close them down, but to create a new college. The king did not want to use royal funds, so he instead combined two colleges ( King's Hall and Michaelhouse) and seven hostels to form Trinity.

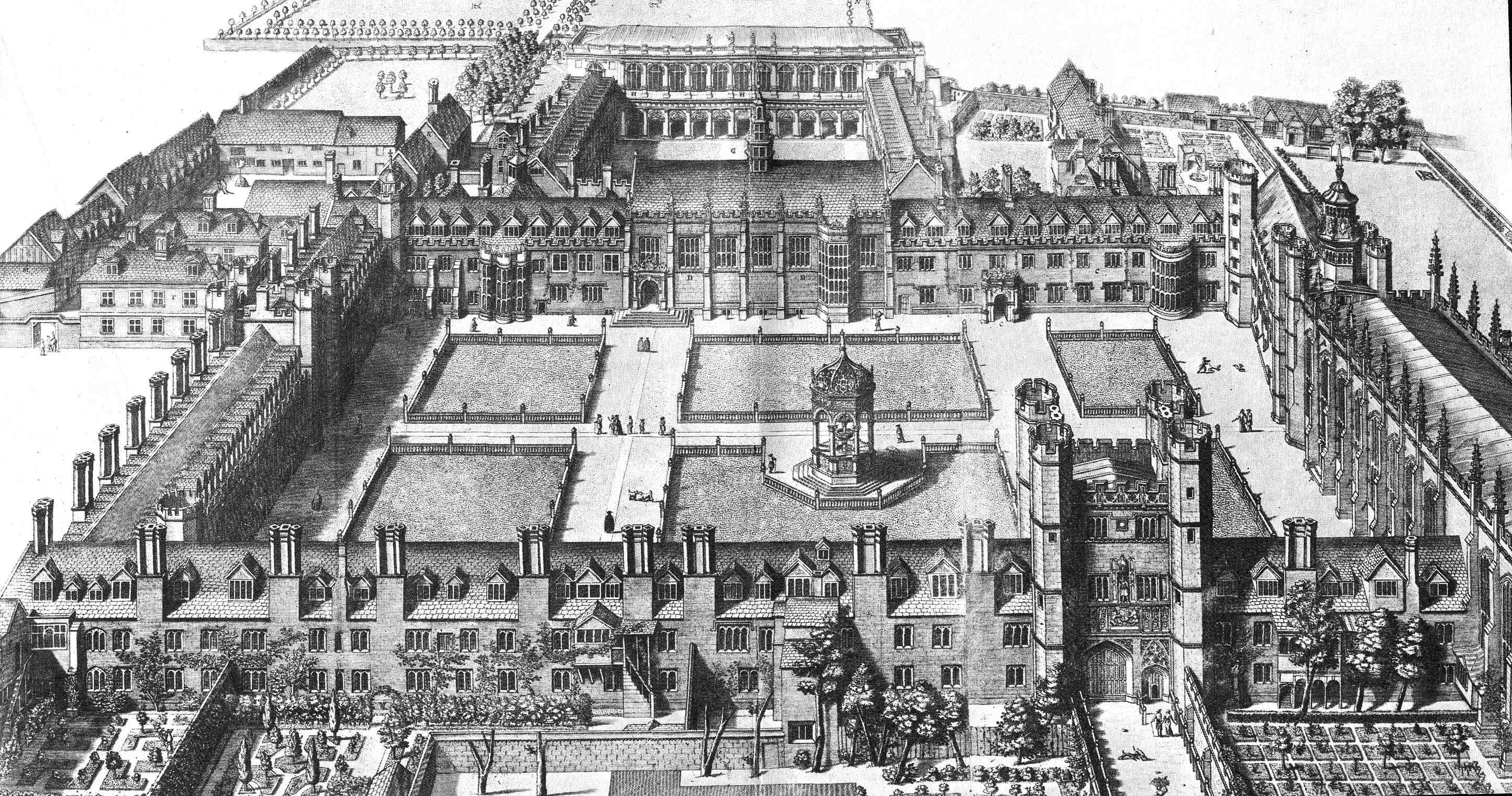

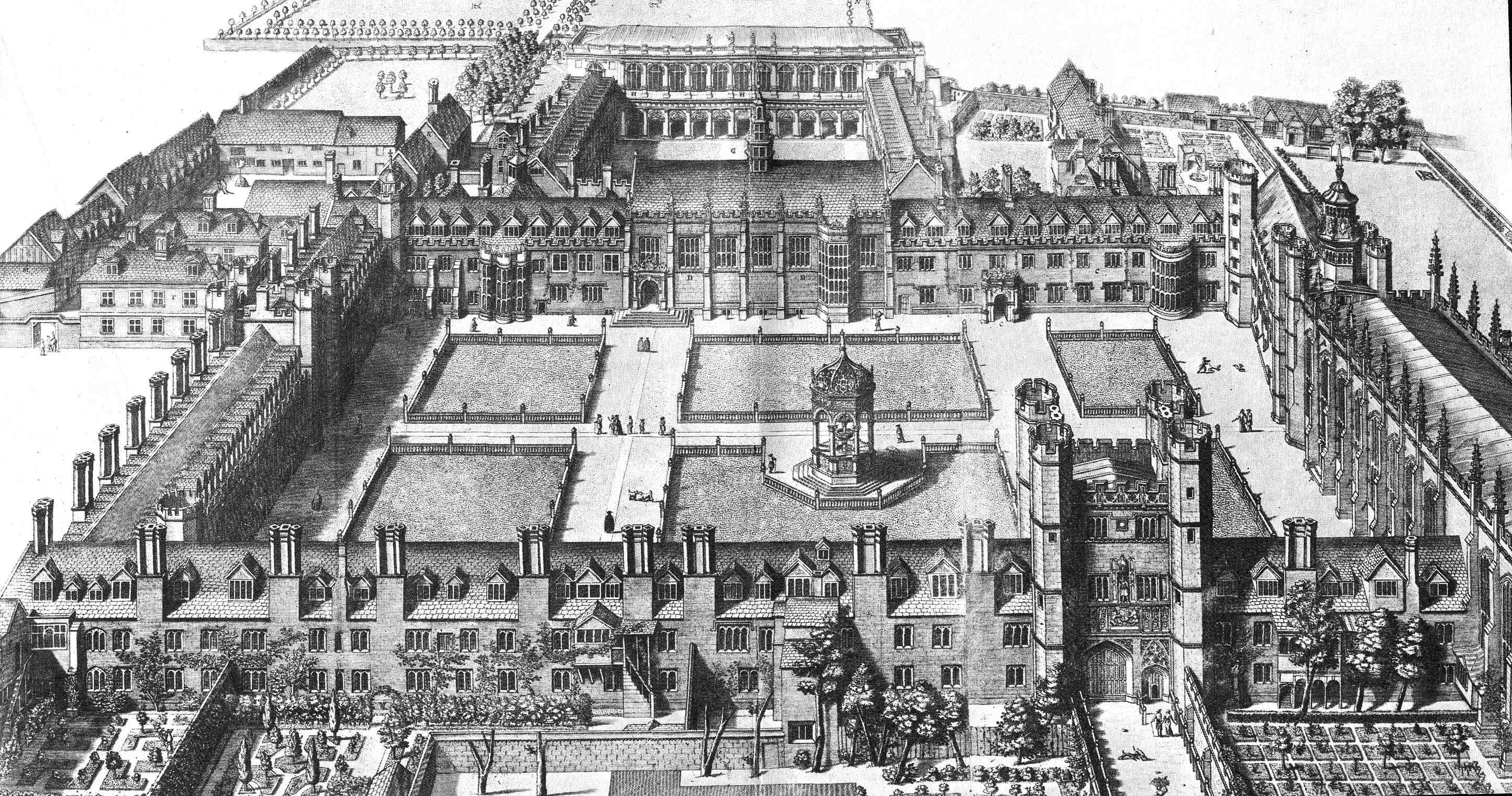

Nevile's expansion

The monastic lands granted by

The monastic lands granted by Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is known for his Wives of Henry VIII, six marriages and his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. ...

were not on their own sufficient to ensure Trinity's eventual rise. In terms of architecture and royal association, it was not until the Mastership of Thomas Nevile (1593–1615) that Trinity assumed both its spaciousness and its association with the governing class that distinguished it since the Civil War. In its infancy Trinity had owed a great deal to its neighbouring college of St John's: in the words of Roger Ascham, Trinity was a ''colonia deducta''.

Most of Trinity's major buildings date from the 16th and 17th centuries. Thomas Nevile, who became Master of Trinity in 1593, rebuilt and redesigned much of the college. This work included the enlargement and completion of Great Court and the construction of Nevile's Court between Great Court and the river Cam. Nevile's Court was completed in the late 17th century with the Wren Library, designed by Christopher Wren

Sir Christopher Wren FRS (; – ) was an English architect, astronomer, mathematician and physicist who was one of the most highly acclaimed architects in the history of England. Known for his work in the English Baroque style, he was ac ...

. Nevile's building campaign drove the college into debt from which it surfaced only in the 1640s, and the Mastership of Richard Bentley adversely affected applications and finances. Bentley himself was notorious for the construction of a hugely expensive staircase in the Master's Lodge and for his repeated refusals to step down despite pleas from the Fellows. Besides, despite not being a sister college of Trinity College Dublin

Trinity College Dublin (), officially titled The College of the Holy and Undivided Trinity of Queen Elizabeth near Dublin, and legally incorporated as Trinity College, the University of Dublin (TCD), is the sole constituent college of the Unive ...

, as is the case with St John's College, Cambridge, it is believed that the Irish institution takes its name from this college, which was the ''alma mater'' of its first provost, Adam Loftus and, likewise, from Trinity College, Oxford.

Modern day

In the 20th century, Trinity College, St John's College and King's College were for decades the main recruiting grounds for the Cambridge Apostles, an elite, intellectual secret society. In 2011, the John Templeton Foundation awarded Trinity College's Master, the astrophysicist Martin Rees, its controversial million-pound

In the 20th century, Trinity College, St John's College and King's College were for decades the main recruiting grounds for the Cambridge Apostles, an elite, intellectual secret society. In 2011, the John Templeton Foundation awarded Trinity College's Master, the astrophysicist Martin Rees, its controversial million-pound Templeton Prize

The Templeton Prize is an annual award granted to a living person, in the estimation of the judges, "whose exemplary achievements advance Sir John Templeton's philanthropic vision: harnessing the power of the sciences to explore the deepest ques ...

, for "affirming life's spiritual dimension". Trinity is the richest Oxbridge

Oxbridge is a portmanteau of the University of Oxford, Universities of Oxford and University of Cambridge, Cambridge, the two oldest, wealthiest, and most prestigious universities in the United Kingdom. The term is used to refer to them collect ...

college with a landholding alone worth £800 million. For comparison, the second richest college in Cambridge (St John's) has estimated assets of around £780 million, and the richest college in Oxford ( Magdelen) has about £940 million.

In 2005, Trinity's annual rental income from its properties was reported to be in excess of £20 million. The college owns:

* 3400 acres (14 km2) housing facilities at the Port of Felixstowe, Britain's busiest container port.

* the Cambridge Science Park

The Cambridge Science Park, founded by Trinity College, Cambridge, Trinity College in 1970, is the oldest science park in the United Kingdom. It is a concentration of science and technology related businesses, and has strong links with the nea ...

.

* the O2 Arena in London (formerly the Millennium Dome).

In 2018, Trinity revealed that it had investments totalling £9.1 million in companies involved in oil and gas production, exploration and refinement. These included holdings of £1.2 million in Royal Dutch Shell, £1.7 million in Exxon Mobil and £1 million in Chevron. In 2019, Trinity confirmed its plan to withdraw from the Universities Superannuation Scheme (USS), the main pre-1992 UK University pension provider. In response, more than 500 Cambridge academics signed an open letter undertaking to "refuse to supervise Trinity students or to engage in other discretionary work in support of Trinity's teaching and research activities". On 17 February 2020, protestors from the campaign group Extinction Rebellion dug up the front lawn of Trinity College to protest against the College's investments in fossil fuels and its negotiations to sell off a farm in Suffolk that was to be turned into a lorry park.

Legends

Lord Byron

George Gordon Byron, 6th Baron Byron (22 January 1788 – 19 April 1824) was an English poet. He is one of the major figures of the Romantic movement, and is regarded as being among the greatest poets of the United Kingdom. Among his best-kno ...

purportedly kept a pet bear whilst living in the college. Trinity is also often cited as the inventor of an English version of crème brûlée, known as "Trinity burnt cream".

Trinity in Camberwell

Trinity College has a long-standing relationship with the Parish of St George's,Camberwell

Camberwell ( ) is an List of areas of London, area of South London, England, in the London Borough of Southwark, southeast of Charing Cross.

Camberwell was first a village associated with the church of St Giles' Church, Camberwell, St Giles ...

, in South London. Students from the College have helped to run holiday schemes for children from the parish since 1966. The relationship was formalised in 1979 with the establishment of Trinity in Camberwell as a registered charity.

Buildings and grounds

Great Gate

The Great Gate is the main entrance to the college, leading to the Great Court. A statue of the college founder,Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is known for his Wives of Henry VIII, six marriages and his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. ...

, stands in a niche above the doorway. In 1983, Trinity College undergraduate Lance Anisfeld, then Vice-President of CURLS (Cambridge Union Raving Loony Society), replaced the chair leg with a bicycle pump. Once discovered the following day, the college removed the pump and replaced it with another chair leg. The original chair leg was auctioned off by TV Presenter Chris Serle at a Cambridge Union Society charity raffle in 1985. In 2023, the college replaced the chair leg with a sceptre to mark the 75th birthday of Charles III

Charles III (Charles Philip Arthur George; born 14 November 1948) is King of the United Kingdom and the 14 other Commonwealth realms.

Charles was born at Buckingham Palace during the reign of his maternal grandfather, King George VI, and ...

, an alumnus of the college. In 1704, the University's first astronomical

Astronomy is a natural science that studies celestial objects and the phenomena that occur in the cosmos. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and their overall evolution. Objects of interest include ...

observatory

An observatory is a location used for observing terrestrial, marine, or celestial events. Astronomy, climatology/meteorology, geophysics, oceanography and volcanology are examples of disciplines for which observatories have been constructed.

Th ...

was built on top of the gatehouse. Beneath the founder's statue are the coats of arms of Edward III

Edward III (13 November 1312 – 21 June 1377), also known as Edward of Windsor before his accession, was King of England from January 1327 until his death in 1377. He is noted for his military success and for restoring royal authority after t ...

, the founder of King's Hall, and those of his five sons who survived to maturity, as well as William of Hatfield, whose shield is blank as he died as an infant, before being granted arms.

Great Court

Great Court (built 1599–1608) was the brainchild of Thomas Nevile, who demolished several existing buildings on this site, including almost the entirety of the former college of Michaelhouse. The sole remaining building of Michaelhouse was replaced by the then current Kitchens (designed by James Essex) in 1770–1775. The Master's Lodge is the official residence of the Sovereign when in Cambridge. King's Hostel (built 1377–1416) is located to the north of Great Court, behind the clock tower. This is, along with the King's Gate, the sole remaining building from King's Hall. Bishop's Hostel (built 1671) is a detached building to the southwest of Great Court, and named after John Hacket, Bishop of Lichfield and Coventry. Additional buildings were built in 1878 by Arthur Blomfield.Nevile's Court

Nevile's Court (built 1614) is located between Great Court and the river, this court was created by a bequest by the college's master, Thomas Nevile, originally two-thirds of its current length and without the Wren Library. The court was extended and the appearance of the upper floor remodelled slightly in 1758 by James Essex. Cloisters run around the court, providing sheltered walkways from the rear of Great Hall to the college library and reading room as well as the Wren Library and New Court.

Nevile's Court (built 1614) is located between Great Court and the river, this court was created by a bequest by the college's master, Thomas Nevile, originally two-thirds of its current length and without the Wren Library. The court was extended and the appearance of the upper floor remodelled slightly in 1758 by James Essex. Cloisters run around the court, providing sheltered walkways from the rear of Great Hall to the college library and reading room as well as the Wren Library and New Court.

The Wren Library (built 1676–1695,

The Wren Library (built 1676–1695, Christopher Wren

Sir Christopher Wren FRS (; – ) was an English architect, astronomer, mathematician and physicist who was one of the most highly acclaimed architects in the history of England. Known for his work in the English Baroque style, he was ac ...

) is located at the west end of Nevile's Court, the Wren is one of Cambridge's most famous and well-endowed libraries. Among its notable possessions are two of Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 23 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's natio ...

's First Folios, a 14th-century manuscript of The Vision of Piers Plowman, letters written by Sir Isaac Newton, and the Eadwine Psalter. Below the building are the pleasant Wren Library Cloisters, where students may enjoy a fine view of the Great Hall in front of them, and the river and Backs directly behind.

New Court

New Court (or ''King's Court''; built 1825, William Wilkins) is located to the south of Nevile's Court, and built in Tudor-Gothic style; this court is notable for the large tree in the centre. A myth is sometimes circulated that this was the tree from which the apple dropped ontoIsaac Newton

Sir Isaac Newton () was an English polymath active as a mathematician, physicist, astronomer, alchemist, theologian, and author. Newton was a key figure in the Scientific Revolution and the Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment that followed ...

; in fact, Newton was at home in Woolsthorpe when he deduced his theory of gravity – and the tree is a horse chestnut tree. For many years it was the custom for students to place a bicycle high in branches of the tree of New Court. Usually invisible except in winter, when the leaves had fallen, such bicycles tended to remain for several years before being removed by the authorities. The students then inserted another bicycle.

Other courts

Whewell's Court (1860–1868, Anthony Salvin) is located across the street from Great Court, and was entirely paid for byWilliam Whewell

William Whewell ( ; 24 May 17946 March 1866) was an English polymath. He was Master of Trinity College, Cambridge. In his time as a student there, he achieved distinction in both poetry and mathematics.

The breadth of Whewell's endeavours is ...

, the Master of the college from 1841 until his death in 1866. The north range was later remodelled by W.D. Caroe. Angel Court (built 1957–1959, H. C. Husband) is located between Great Court and Trinity Street, and is used along with the Wolfson Building for accommodating first year students.

The Wolfson Building (built 1968–1972, Architects' Co-Partnership) is located to the south of Whewell's Court, on top of a podium above shops, this building resembles a brick-clad ziggurat, and is used exclusively for first-year accommodation. Having been renovated during the academic year 2005–06, many rooms are now en-suite. Blue Boar Court (built 1989, MJP Architects) is located to the south of the Wolfson Building, on top of podium a floor up from ground level, and including the upper floors of several surrounding Georgian buildings on Trinity Street, Green Street and Sidney Street. Burrell's Field (built 1995, MJP Architects) is located on a site to the west of the main College buildings, opposite the Cambridge University Library.

Chapel

Trinity College Chapel dates from the mid 16th century and is Grade I listed. There are a number of memorials to former Fellows of Trinity within the Chapel, including statues, brasses, and two memorials to graduates and Fellows who died during the World Wars. Among the most notable of these is a statue of Isaac Newton by Roubiliac, described by Sir Francis Chantrey as "the noblest, I think, of all our English statues." The Chapel is a performance space for the College Choir which comprises around thirty Choral Scholars and two Organ Scholars, all of whom are ordinarily students at the University.Grounds

The Fellows' Garden is located on the west side of Queen's Road, opposite the drive that leads to the Backs. The Fellows' Bowling Green is located north of Great Court, between King's Hostel and the river. It is the site for many of the tutors' garden parties in the summer months, while the Master's Garden is located behind the Master's Lodge. The Old Fields are located on the western side of Grange Road, next to Burrell's Field. It currently houses the college's gym, changing rooms, squash courts, badminton courts, rugby, hockey and football pitches along with tennis and netball courts.Trinity Bridge

Trinity Bridge is a stone built triple-arched road bridge across the River Cam. It was built of Portland stone in 1765 to the designs of James Essex to replace an earlier bridge built in 1651 and is a Grade I listed building.Gallery

Academic profile

Over the last twenty years, the college has always come at least eighth in the Tompkins Table, which ranks the twenty-nine undergraduate Cambridge colleges according to the academic performance of their undergraduates, and for the last six occasions it has been in first place. Its average position in the Tompkins Table over that period has been between second and third, higher than any other. In 2016, 45% of Trinity undergraduates achieved First Class Honours, twelve percentage points ahead of second place Pembroke – a record among Cambridge colleges.Admissions

Trinity's history, academic performance and alumni have made it one of the most prestigious constituent colleges of the University, making admission extremely competitive. About 50% of Trinity's undergraduates attended independent schools. In 2006 it accepted a smaller proportion of students from state schools (39%) than any other Cambridge college, and on a rolling three-year average it has admitted a smaller proportion of state school pupils (42%) than any other college at either Cambridge or Oxford. According to the '' Good Schools Guide'', about 7% of British school-age students attend private schools, although this figure refers to students in all school years – a higher proportion attend private schools in their final two years before university. Trinity states that it disregards what type of school its applicants attend, and accepts students solely on the basis of their academic prospects. Trinity admitted its first female graduate student in 1976, its first female undergraduate in 1978 and elected its first female fellow ( Marian Hobson) in 1977.Scholarships and prizes

The Scholars, together with the Master and Fellows, make up the Foundation of the College. In order of seniority:

* Research Scholars receive funding for graduate studies. Typically, one must graduate in the top ten percent of one's class and continue for graduate study at Trinity. They are given first preference in the assignment of college rooms and number approximately 25.

* The Senior Scholars usually consist of those who attain a degree with First Class honours or higher in any year after the first of an undergraduate

The Scholars, together with the Master and Fellows, make up the Foundation of the College. In order of seniority:

* Research Scholars receive funding for graduate studies. Typically, one must graduate in the top ten percent of one's class and continue for graduate study at Trinity. They are given first preference in the assignment of college rooms and number approximately 25.

* The Senior Scholars usually consist of those who attain a degree with First Class honours or higher in any year after the first of an undergraduate tripos

TRIPOS (''TRIvial Portable Operating System'') is a computer operating system. Development started in 1976 at the Computer Laboratory of Cambridge University and it was headed by Dr. Martin Richards. The first version appeared in January 1978 a ...

. The college pays them a stipend of £250 a year and allows them to choose rooms directly following the research scholars. There are around 40 senior scholars at any one time.

* The Junior Scholars usually consist of those who attained a First in their first year. Their stipend is £175 a year. They are given preference in the room ballot over 2nd years who are not scholars.

These scholarships are tenable for the academic year following that in which the result was achieved. If a scholarship is awarded but the student does not continue at Trinity then only a quarter of the stipend is given. However, all students who achieve a First are awarded an additional £240 prize upon announcement of the results.

Many final year undergraduates who achieve first-class honours in their final exams are offered full financial support, through a scheme known as Internal Graduate Studentships, to read for a master's degree

A master's degree (from Latin ) is a postgraduate academic degree awarded by universities or colleges upon completion of a course of study demonstrating mastery or a high-order overview of a specific field of study or area of professional prac ...

at Cambridge. Other support is available for PhD degrees. The College also offers a number of other bursaries and studentships open to external applicants. The right to walk on the grass in the college courts is exclusive to Fellows of the college and their guests. Scholars do, however, have the right to walk on the Scholars' Lawn, but only in full academic dress.

Traditions

Great Court Run

The Great Court Run requires a circuit of the 400-yard perimeter of Great Court, in the 43 seconds of the clock striking 12. The time varies according to humidity. Students traditionally attempt to complete the circuit on the day of the Matriculation Dinner. It is a difficult challenge: one needs to be a fine sprinter to achieve it, but it is not necessary to be of Olympic standard, despite assertions made in the press. It is widely believed that Sebastian Coe successfully completed the run when he beat Steve Cram in a charity race in October 1988. Coe's time on 29 October 1988 was reported by Norris McWhirter to have been 45.52 seconds, but it was actually 46.0 seconds, while Cram's was 46.3 seconds. The clock on that day took 44.4 seconds and the video film confirms that Coe was some 12 metres short of the finish line when the final stroke occurred. The television commentators were wrong to speculate that the dying sounds of the bell could be included in the striking time, thereby allowing Coe's run to be claimed as successful. One reason Olympic runners Cram and Coe found the challenge difficult is that they started at the middle of one side of the court, having to negotiate four right-angle turns. In the days when students started at a corner, only three turns were needed. In addition, Cram and Coe ran entirely on the flagstones, while until 2017 students have typically cut corners to run on the cobbles. The Great Court Run was portrayed in the film '' Chariots of Fire'' about the British Olympic runners of 1924. The run was filmed atEton College

Eton College ( ) is a Public school (United Kingdom), public school providing boarding school, boarding education for boys aged 13–18, in the small town of Eton, Berkshire, Eton, in Berkshire, in the United Kingdom. It has educated Prime Mini ...

in Berkshire, not in Great Court. Until the mid-1990s, the run was traditionally attempted by first-year students at midnight following their matriculation dinner. Following a number of accidents to undergraduates running on slippery cobbles, the college now organises a more formal Great Court Run, at 12 noon on the day of the matriculation dinner: while some contestants compete seriously, many others run in fancy dress and there are prizes for the fastest man and woman in each category.

Open-air concerts

One Sunday each June, the College Choir perform a short concert immediately after the clock strikes noon. Known as ''Singing from the Towers'', half of the choir sings from the top of the Great Gate, while the other half sings from the top of the Clock Tower approximately 60 metres away, giving a strong antiphonal effect. Midway through the concert, the Cambridge University Brass Ensemble performs from the top of the Queen's Tower. Later that same day, the College Choir gives a second open-air concert, known as ''Singing on the River'', where they perform madrigals and arrangements of popular songs from a raft of punts lit with lanterns or fairy lights on theriver

A river is a natural stream of fresh water that flows on land or inside Subterranean river, caves towards another body of water at a lower elevation, such as an ocean, lake, or another river. A river may run dry before reaching the end of ...

. For the finale, John Wilbye's madrigal ''Draw on, sweet night'', the raft is unmoored and punted downstream to give a fade out effect. As a tradition, however, this latter concert dates back only to the mid-1980s, when the College Choir first acquired female members. In the years immediately before this, an annual concert on the river was given by the University Madrigal Society.

Mallard

Another tradition relates to an artificial duck known as the Mallard, which should reside in the rafters of the Great Hall. Students occasionally moved the duck from one rafter to another without permission from the college. This is considered difficult; access to the Hall outside meal-times is prohibited and the rafters are dangerously high, so it was not attempted for several years. During the Easter term of 2006, the Mallard was knocked off its rafter by one of the pigeons which enter the Hall through the pinnacle windows. It was reinstated by students in 2016, and is only visible from the far end of the hall.College rivalry

The college remains a great rival of St John's which is its main competitor in sports and academia. This has given rise to a number of anecdotes and myths. It is often cited as the reason that the older courts of Trinity generally have no J staircases, despite including other letters in alphabetical order. A far more likely reason is that theLatin alphabet

The Latin alphabet, also known as the Roman alphabet, is the collection of letters originally used by the Ancient Rome, ancient Romans to write the Latin language. Largely unaltered except several letters splitting—i.e. from , and from � ...

did not have the letter J—the older courts of St John's College also lack J staircases. There are also two small muzzle-loading cannons on the bowling green pointing in the direction of John's, though this orientation may be coincidental. Another story sometimes told is that the reason that the clock in Trinity Great Court strikes each hour twice is that the fellows of St John's once complained about the noise it made.

College Grace

Each evening before dinner, grace is recited by the senior fellow presiding, as follows:

If both of the two high tables are in use then the following antiphonal formula is prefixed to the main grace:

Following the meal, the simple formula is pronounced.

Each evening before dinner, grace is recited by the senior fellow presiding, as follows:

If both of the two high tables are in use then the following antiphonal formula is prefixed to the main grace:

Following the meal, the simple formula is pronounced.

Punt names

Befitting the term ''trinity

The Trinity (, from 'threefold') is the Christian doctrine concerning the nature of God, which defines one God existing in three, , consubstantial divine persons: God the Father, God the Son (Jesus Christ) and God the Holy Spirit, thr ...

'', Trinity College punts are named after people or things related to the number three, such as ''Bronze

Bronze is an alloy consisting primarily of copper, commonly with about 12–12.5% tin and often with the addition of other metals (including aluminium, manganese, nickel, or zinc) and sometimes non-metals (such as phosphorus) or metalloid ...

'' (award for third place), '' Codon'' (which has three nucleotide

Nucleotides are Organic compound, organic molecules composed of a nitrogenous base, a pentose sugar and a phosphate. They serve as monomeric units of the nucleic acid polymers – deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and ribonucleic acid (RNA), both o ...

s) and '' Wise Monkey''. In 2023, the launch of the punt ''Charles'' marked the coronation of alumnus Charles III

Charles III (Charles Philip Arthur George; born 14 November 1948) is King of the United Kingdom and the 14 other Commonwealth realms.

Charles was born at Buckingham Palace during the reign of his maternal grandfather, King George VI, and ...

.

Minor traditions

Trinity College undergraduate gowns are readily distinguished from the black gowns favoured by most other Cambridge colleges. They are instead dark blue with black facings. They are expected to be worn to formal events such as formal halls and also when an undergraduate sees the Dean of the College in a formal capacity. Trinity students, along with those of King's and St John's, are the first to be presented to the Congregation of the Regent House at graduation.People associated with Trinity

Notable fellows and alumni

The Parish of the Ascension Burial Ground in Cambridge contains the graves of 27 Fellows of Trinity College, Cambridge most of whom are also commemorated in Trinity College Chapel with brass plaques.

The Parish of the Ascension Burial Ground in Cambridge contains the graves of 27 Fellows of Trinity College, Cambridge most of whom are also commemorated in Trinity College Chapel with brass plaques. Charles III

Charles III (Charles Philip Arthur George; born 14 November 1948) is King of the United Kingdom and the 14 other Commonwealth realms.

Charles was born at Buckingham Palace during the reign of his maternal grandfather, King George VI, and ...

, King of the United Kingdom

The monarchy of the United Kingdom, commonly referred to as the British monarchy, is the form of government used by the United Kingdom by which a hereditary monarch reigns as the head of state, with their powers Constitutional monarchy, regula ...

, attended from 1967 to 1970. Marian Hobson was the first woman to become a Fellow of the college, having been elected in 1977, and her portrait now hangs in the college hall along with those of other notable members of the college. Other notable female Fellows include Anne Barton, Marilyn Strathern, Catherine Barnard, Lynn Gladden and Rebecca Fitzgerald.

Nobel Prize winners

This list includes winners of the

This list includes winners of the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences

The Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences, officially the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel (), commonly referred to as the Nobel Prize in Economics(), is an award in the field of economic sciences adminis ...

, which is not one of the five Nobel Prize

The Nobel Prizes ( ; ; ) are awards administered by the Nobel Foundation and granted in accordance with the principle of "for the greatest benefit to humankind". The prizes were first awarded in 1901, marking the fifth anniversary of Alfred N ...

s established by Alfred Nobel's will in 1895.

Fields Medallists

Four members or alumni of Trinity College have been awarded theFields Medal

The Fields Medal is a prize awarded to two, three, or four mathematicians under 40 years of age at the International Congress of Mathematicians, International Congress of the International Mathematical Union (IMU), a meeting that takes place e ...

.

Turing Award winners

British prime ministers

Other Trinity politicians include Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex, courtier ofElizabeth I

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was List of English monarchs, Queen of England and List of Irish monarchs, Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. She was the last and longest reigning monarch of the House of Tudo ...

; William Waddington, Prime Minister of France; Erskine Hamilton Childers, fourth President of Ireland; Jawaharlal Nehru

Jawaharlal Nehru (14 November 1889 – 27 May 1964) was an Indian anti-colonial nationalist, secular humanist, social democrat, and statesman who was a central figure in India during the middle of the 20th century. Nehru was a pr ...

, the first and longest serving Prime Minister of India

India, officially the Republic of India, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area; the List of countries by population (United Nations), most populous country since ...

; Rajiv Gandhi, Prime Minister of India; Lee Hsien Loong

Lee Hsien Loong (born 10 February 1952) is a Singaporean politician and former military officer who served as the third Prime Minister of Singapore, prime minister of Singapore from 2004 to 2024, thereafter serving as a Senior Minister of S ...

, Prime Minister of Singapore; Samir Rifai, Prime Minister of Jordan; Richard Blumenthal

Richard Blumenthal ( ; born February 13, 1946) is an American politician, lawyer, and United States Marine Corps, Marine Corps veteran serving as the Seniority in the United States Senate, senior United States Senate, United States senator from ...

, incumbent senior US Senator from Connecticut; and William Whitelaw, Home Secretary and subsequently Deputy Prime Minister.

Masters

The head of Trinity College is called the Master. The role is a Crown appointment, formally made by the monarch on the advice of the prime minister. Nowadays, the fellows of the college propose a new master for the appointment, but the decision is formally that of the Crown. The first Master, John Redman, was appointed in 1546. Six masters subsequent to Rab Butler had been fellows of the college prior to becoming master ( honorary fellow in the case of Martin Rees), the last of these being Sir Gregory Winter, appointed on 2 October 2012. He was succeeded by Dame Sally Davies, the first female Master of Trinity College, on 8 October 2019.

The head of Trinity College is called the Master. The role is a Crown appointment, formally made by the monarch on the advice of the prime minister. Nowadays, the fellows of the college propose a new master for the appointment, but the decision is formally that of the Crown. The first Master, John Redman, was appointed in 1546. Six masters subsequent to Rab Butler had been fellows of the college prior to becoming master ( honorary fellow in the case of Martin Rees), the last of these being Sir Gregory Winter, appointed on 2 October 2012. He was succeeded by Dame Sally Davies, the first female Master of Trinity College, on 8 October 2019.

See also

* Isaac Newton Institute for Mathematical Sciences, partially funded by TrinityNotes

External links

Trinity College, Cambridge official website

Trinity College, Cambridge Access website

Trinity College Isaac Newton Trust

established in 1988

Paintings at Trinity College, Cambridge

ArtUK project. {{coord, 52.2070, 0.1146, type:landmark, name=Trinity College, format=dms, display=title Henry VIII Catherine Parr 1546 establishments in England Colleges of the University of Cambridge Educational institutions established in the 1540s Grade I listed buildings in Cambridge Grade I listed educational buildings Edward Blore buildings