Tridentine Reforms on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Council of Trent ( la, Concilium Tridentinum), held between 1545 and 1563 in

In reply to the Papal bull '' Exsurge Domine'' of Pope Leo X (1520), Martin Luther burned the document and appealed for a general council. In 1522 German diets joined in the appeal, with Charles V seconding and pressing for a council as a means of reunifying the Church and settling the Reformation controversies. Pope Clement VII (1523–1534) was vehemently against the idea of a council, agreeing with Francis I of France, after Pope Pius II, in his bull ''

In reply to the Papal bull '' Exsurge Domine'' of Pope Leo X (1520), Martin Luther burned the document and appealed for a general council. In 1522 German diets joined in the appeal, with Charles V seconding and pressing for a council as a means of reunifying the Church and settling the Reformation controversies. Pope Clement VII (1523–1534) was vehemently against the idea of a council, agreeing with Francis I of France, after Pope Pius II, in his bull ''

The doctrinal acts are as follows: after reaffirming the Niceno-Constantinopolitan Creed (third session), the decree was passed (fourth session) confirming that the deuterocanonical books were on a par with the other books of the canon (against Luther's placement of these books in the Apocrypha of

The doctrinal acts are as follows: after reaffirming the Niceno-Constantinopolitan Creed (third session), the decree was passed (fourth session) confirming that the deuterocanonical books were on a par with the other books of the canon (against Luther's placement of these books in the Apocrypha of

Out of 87 books written between 1546 and 1564 attacking the Council of Trent, 41 were written by Pier Paolo Vergerio, a former papal nuncio turned Protestant Reformer. The 1565–73 ''Examen decretorum Concilii Tridentini'' (''

Out of 87 books written between 1546 and 1564 attacking the Council of Trent, 41 were written by Pier Paolo Vergerio, a former papal nuncio turned Protestant Reformer. The 1565–73 ''Examen decretorum Concilii Tridentini'' (''

Defensio

', 716 pages, free on Google Books. which was published posthumously in 1578. However, the ''Defensio'' did not circulate as extensively as the ''Examen'', nor were any full translations ever published. A French translation of the ''Examen'' by Eduard Preuss was published in 1861. German translations were published in 1861, 1884, and 1972. In English, a complete translation by Fred Kramer drawing from the original Latin and the 1861 German was published beginning in 1971.

google books

James Waterworth (ed.), ''The Canons and Decrees of the Sacred and Oecumenical Council of Trent'' (1848)

The text of the Council of Trent

translated by J. Waterworth, 1848

also on Intratext

ZIP version of the documents of the Council of Trent

{{Authority control 1545 establishments in the Papal States 1563 disestablishments Counter-Reformation

Trent

Trent may refer to:

Places Italy

* Trento in northern Italy, site of the Council of Trent United Kingdom

* Trent, Dorset, England, United Kingdom Germany

* Trent, Germany, a municipality on the island of Rügen United States

* Trent, California, ...

(or Trento), now in northern Italy, was the 19th ecumenical council of the Catholic Church. Prompted by the Protestant Reformation, it has been described as the embodiment of the Counter-Reformation

The Counter-Reformation (), also called the Catholic Reformation () or the Catholic Revival, was the period of Catholic resurgence that was initiated in response to the Protestant Reformation. It began with the Council of Trent (1545–1563) a ...

."Trent, Council of" in Cross, F. L. (ed.) ''The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church'', Oxford University Press, 2005 ().

The Council issued condemnations of what it defined to be heresies

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, in particular the accepted beliefs of a church or religious organization. The term is usually used in reference to violations of important religi ...

committed by proponents of Protestantism, and also issued key statements and clarifications of the Church's doctrine and teachings, including scripture, the biblical canon, sacred tradition, original sin

Original sin is the Christian doctrine that holds that humans, through the fact of birth, inherit a tainted nature in need of regeneration and a proclivity to sinful conduct. The biblical basis for the belief is generally found in Genesis 3 (t ...

, justification

Justification may refer to:

* Justification (epistemology), a property of beliefs that a person has good reasons for holding

* Justification (jurisprudence), defence in a prosecution for a criminal offenses

* Justification (theology), God's act of ...

, salvation, the sacraments

A sacrament is a Christian rite that is recognized as being particularly important and significant. There are various views on the existence and meaning of such rites. Many Christians consider the sacraments to be a visible symbol of the real ...

, the Mass, and the veneration of saints.Wetterau, Bruce. ''World History''. New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1994. The Council met for twenty-five sessions between 13 December 1545 and 4 December 1563. Pope Paul III

Pope Paul III ( la, Paulus III; it, Paolo III; 29 February 1468 – 10 November 1549), born Alessandro Farnese, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 13 October 1534 to his death in November 1549.

He came to ...

, who convoked the Council, oversaw the first eight sessions (1545–47), while the twelfth to sixteenth sessions (1551–52) were overseen by Pope Julius III and the seventeenth to twenty-fifth sessions (1562–63) by Pope Pius IV

Pope Pius IV ( it, Pio IV; 31 March 1499 – 9 December 1565), born Giovanni Angelo Medici, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 25 December 1559 to his death in December 1565. Born in Milan, his family considered ...

.

The consequences of the Council were also significant with regard to the Church's liturgy and practices. In its decrees, the Council made the Latin Vulgate the official biblical text of the Roman Church (without prejudice to the original texts in Hebrew and Greek, nor to other traditional translations of the Church, but favoring the Latin language over vernacular translations, such as the controversial English-language Tyndale Bible). In doing so, they commissioned the creation of a revised and standardized Vulgate in light of textual criticism, although this was not achieved until the 1590s. The Council also officially affirmed (for the second time at an ecumenical council) the traditional Catholic Canon of biblical books in response to the increasing Protestant exclusion of the deuterocanonical books. The former dogmatic affirmation of the Canonical books was at the Council of Florence

The Council of Florence is the seventeenth ecumenical council recognized by the Catholic Church, held between 1431 and 1449. It was convoked as the Council of Basel by Pope Martin V shortly before his death in February 1431 and took place in ...

in the 1441 bull ''Cantate Domino'', as affirmed by Pope Leo XIII in his 1893 encyclical ''Providentissimus Deus

''Providentissimus Deus'', "On the Study of Holy Scripture", was an encyclical letter issued by Pope Leo XIII on 18 November 1893. In it, he reviewed the history of Bible study from the time of the Church Fathers to the present, spoke against th ...

'' (#20). In 1565, a year after the Council finished its work, Pius IV issued the Tridentine Creed (after ''Tridentum'', Trent's Latin name) and his successor Pius V then issued the Roman Catechism and revisions of the Breviary

A breviary (Latin: ''breviarium'') is a liturgical book used in Christianity for praying the canonical hours, usually recited at seven fixed prayer times.

Historically, different breviaries were used in the various parts of Christendom, such a ...

and Missal

A missal is a liturgical book containing instructions and texts necessary for the celebration of Mass throughout the liturgical year. Versions differ across liturgical tradition, period, and purpose, with some missals intended to enable a pries ...

in, respectively, 1566, 1568 and 1570. These, in turn, led to the codification of the Tridentine Mass, which remained the Church's primary form of the Mass for the next four hundred years.

More than three hundred years passed until the next ecumenical council, the First Vatican Council

The First Ecumenical Council of the Vatican, commonly known as the First Vatican Council or Vatican I was convoked by Pope Pius IX on 29 June 1868, after a period of planning and preparation that began on 6 December 1864. This, the twentieth ecu ...

, was convened in 1869.

Background information

Obstacles and events before the Council's problem area

On 15 March 1517, the Fifth Council of the Lateran closed its activities with a number of reform proposals (on the selection of bishops, taxation, censorship and preaching) but not on the major problems that confronted the Church in Germany and other parts of Europe. A few months later, on 31 October 1517, Martin Luther issued his '' 95 Theses'' in Wittenberg.A general, free council in Germany

Luther's position on ecumenical councils shifted over time, but in 1520 he appealed to the German princes to oppose the papal Church, if necessary with a council in Germany, open and free of the Papacy. After the Pope condemned in '' Exsurge Domine'' fifty-two of Luther's theses as heresy, German opinion considered a council the best method to reconcile existing differences. German Catholics, diminished in number, hoped for a council to clarify matters.Jedin 81 It took a generation for the council to materialise, partly due to papal fears over potentially renewing a schism over conciliarism; partly because Lutherans demanded the exclusion of the papacy from the Council; partly because of ongoing political rivalries between France and the Holy Roman Empire; and partly due to the Turkish dangers in the Mediterranean. Under Pope Clement VII (1523–34), troops of the CatholicHoly Roman Emperor

The Holy Roman Emperor, originally and officially the Emperor of the Romans ( la, Imperator Romanorum, german: Kaiser der Römer) during the Middle Ages, and also known as the Roman-German Emperor since the early modern period ( la, Imperat ...

Charles V sacked Papal Rome in 1527, "raping, killing, burning, stealing, the like had not been seen since the Vandals". Saint Peter's Basilica and the Sistine Chapel were used for horses. Pope Clement, fearful of the potential for more violence, delayed calling the Council.

Charles V strongly favoured a council but needed the support of King Francis I

Francis I (french: François Ier; frm, Francoys; 12 September 1494 – 31 March 1547) was King of France from 1515 until his death in 1547. He was the son of Charles, Count of Angoulême, and Louise of Savoy. He succeeded his first cousin once ...

of France, who attacked him militarily. Francis I generally opposed a general council due to partial support of the Protestant cause within France. In 1532 he agreed to the Nuremberg Religious Peace granting religious liberty to the Protestants, and in 1533 he further complicated matters when suggesting a general council to include both Catholic and Protestant rulers of Europe that would devise a compromise between the two theological systems. This proposal met the opposition of the Pope for it gave recognition to Protestants and also elevated the secular Princes of Europe above the clergy on church matters. Faced with a Turkish attack, Charles held the support of the Protestant German rulers, all of whom delayed the opening of the Council of Trent.

Occasion, sessions, and attendance

In reply to the Papal bull '' Exsurge Domine'' of Pope Leo X (1520), Martin Luther burned the document and appealed for a general council. In 1522 German diets joined in the appeal, with Charles V seconding and pressing for a council as a means of reunifying the Church and settling the Reformation controversies. Pope Clement VII (1523–1534) was vehemently against the idea of a council, agreeing with Francis I of France, after Pope Pius II, in his bull ''

In reply to the Papal bull '' Exsurge Domine'' of Pope Leo X (1520), Martin Luther burned the document and appealed for a general council. In 1522 German diets joined in the appeal, with Charles V seconding and pressing for a council as a means of reunifying the Church and settling the Reformation controversies. Pope Clement VII (1523–1534) was vehemently against the idea of a council, agreeing with Francis I of France, after Pope Pius II, in his bull ''Execrabilis

''Execrabilis'' is a papal bull issued by Pope Pius II on 18 January 1460 condemning conciliarism. The bull received its name from the opening word of its Latin text, which labelled as "execrable" all efforts to appeal an authoritative ruling of ...

'' (1460) and his reply to the University of Cologne (1463), set aside the theory of the supremacy of general councils laid down by the Council of Constance

The Council of Constance was a 15th-century ecumenical council recognized by the Catholic Church, held from 1414 to 1418 in the Bishopric of Constance in present-day Germany. The council ended the Western Schism by deposing or accepting the res ...

.

Pope Paul III

Pope Paul III ( la, Paulus III; it, Paolo III; 29 February 1468 – 10 November 1549), born Alessandro Farnese, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 13 October 1534 to his death in November 1549.

He came to ...

(1534–1549), seeing that the Protestant Reformation was no longer confined to a few preachers, but had won over various princes, particularly in Germany, to its ideas, desired a council. Yet when he proposed the idea to his cardinals, it was almost unanimously opposed. Nonetheless, he sent nuncio

An apostolic nuncio ( la, nuntius apostolicus; also known as a papal nuncio or simply as a nuncio) is an ecclesiastical diplomat, serving as an envoy or a permanent diplomatic representative of the Holy See to a state or to an international or ...

s throughout Europe to propose the idea. Paul III issued a decree for a general council to be held in Mantua, Italy, to begin on 23 May 1537. Martin Luther wrote the Smalcald Articles in preparation for the general council. The Smalcald Articles were designed to sharply define where the Lutherans could and could not compromise. The council was ordered by the Emperor and Pope Paul III to convene in Mantua on 23 May 1537. It failed to convene after another war broke out between France and Charles V, resulting in a non-attendance of French prelates. Protestants refused to attend as well. Financial difficulties in Mantua led the Pope in the autumn of 1537 to move the council to Vicenza, where participation was poor. The Council was postponed indefinitely on 21 May 1539. Pope Paul III then initiated several internal Church reforms while Emperor Charles V convened with Protestants and Cardinal Gasparo Contarini at the Diet of Regensburg Diet of Regensburg may refer any of the sessions of the Imperial Diet, Imperial States, or the prince-electors of the Holy Roman Empire which took place in the Imperial City of Regensburg (Ratisbon), now in Germany.

An incomplete lists of Diets o ...

, to reconcile differences. Mediating and conciliatory formulations were developed on certain topics. In particular, a two-part doctrine of justification was formulated that would later be rejected at Trent. Unity failed between Catholic and Protestant representatives "because of different concepts of ''Church'' and ''justification

Justification may refer to:

* Justification (epistemology), a property of beliefs that a person has good reasons for holding

* Justification (jurisprudence), defence in a prosecution for a criminal offenses

* Justification (theology), God's act of ...

''".

However, the council was delayed until 1545 and, as it happened, convened right before Luther's death. Unable, however, to resist the urging of Charles V, the pope, after proposing Mantua as the place of meeting, convened the council at Trent (at that time ruled by a prince-bishop under the Holy Roman Empire), on 13 December 1545; the Pope's decision to transfer it to Bologna in March 1547 on the pretext of avoiding a plague failed to take effect and the Council was indefinitely prorogued on 17 September 1549. None of the three popes reigning over the duration of the council ever attended, which had been a condition of Charles V. Papal legate

300px, A woodcut showing Henry II of England greeting the pope's legate.

A papal legate or apostolic legate (from the ancient Roman title ''legatus'') is a personal representative of the pope to foreign nations, or to some part of the Catholic ...

s were appointed to represent the Papacy.

Reopened at Trent on 1 May 1551 by the convocation of Pope Julius III (1550–1555), it was broken up by the sudden victory of Maurice, Elector of Saxony over Emperor Charles V and his march into surrounding state of Tirol on 28 April 1552. There was no hope of reassembling the council while the very anti-Protestant Paul IV was Pope. The council was reconvened by Pope Pius IV

Pope Pius IV ( it, Pio IV; 31 March 1499 – 9 December 1565), born Giovanni Angelo Medici, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 25 December 1559 to his death in December 1565. Born in Milan, his family considered ...

(1559–1565) for the last time, meeting from 18 January 1562 at Santa Maria Maggiore

The Basilica of Saint Mary Major ( it, Basilica di Santa Maria Maggiore, ; la, Basilica Sanctae Mariae Maioris), or church of Santa Maria Maggiore, is a Major papal basilica as well as one of the Seven Pilgrim Churches of Rome and the larges ...

, and continued until its final adjournment on 4 December 1563. It closed with a series of ritual acclamations honouring the reigning Pope, the Popes who had convoked the Council, the emperor and the kings who had supported it, the papal legates, the cardinals, the ambassadors present, and the bishops, followed by acclamations of acceptance of the faith of the Council and its decrees, and of anathema for all heretics.

The history of the council is thus divided into three distinct periods: 1545–1549, 1551–1552 and 1562–1563. During the second period, the Protestants present asked for a renewed discussion on points already defined and for bishops to be released from their oaths of allegiance to the Pope. When the last period began, all intentions of conciliating the Protestants was gone and the Jesuits had become a strong force. This last period was begun especially as an attempt to prevent the formation of a general council including Protestants, as had been demanded by some in France.

The number of attending members in the three periods varied considerably. The council was small to begin with, opening with only about 30 bishops.O'Malley, 29 It increased toward the close, but never reached the number of the First Council of Nicaea (which had 318 members) nor of the First Vatican Council

The First Ecumenical Council of the Vatican, commonly known as the First Vatican Council or Vatican I was convoked by Pope Pius IX on 29 June 1868, after a period of planning and preparation that began on 6 December 1864. This, the twentieth ecu ...

(which numbered 744). The decrees were signed in 1563 by 255 members, the highest attendance of the whole council, including four papal legates, two cardinals, three patriarchs, twenty-five archbishops, and 168 bishops, two-thirds of whom were Italians. The Italian and Spanish prelates were vastly preponderant in power and numbers. At the passage of the most important decrees, not more than sixty prelates were present. Although most Protestants did not attend, ambassadors and theologians of Brandenburg, Württemberg, and Strasbourg attended having been granted an improved safe conduct

Safe conduct, safe passage, or letters of transit, is the situation in time of international conflict or war where one state, a party to such conflict, issues to a person (usually an enemy state's subject) a pass or document to allow the enemy ...

.

The French monarchy boycotted the entire council until the last minute when a delegation led by Charles de Guise, Cardinal of Lorraine finally arrived in November 1562. The first outbreak of the French Wars of Religion had occurred earlier in the year and the French Church, facing a significant and powerful Protestant minority in France, experienced iconoclasm violence regarding the use of sacred images. Such concerns were not primary in the Italian and Spanish Churches. The last-minute inclusion of a decree on sacred images was a French initiative, and the text, never discussed on the floor of the council or referred to council theologians, was based on a French draft.

Objectives and overall results

The main objectives of the council were twofold, although there were other issues that were also discussed: #To condemn the principles and doctrines of Protestantism and to clarify the doctrines of the Catholic Church on all disputed points. This had not been done formally since the 1530 '' Confutatio Augustana''. It is true that the emperor intended it to be a strictly general or truly ecumenical council, at which the Protestants should have a fair hearing. He secured, during the council's second period, 1551–1553, an invitation, twice given, to the Protestants to be present and the council issued a letter of safe conduct (thirteenth session) and offered them the right of discussion, but denied them a vote.Melanchthon

Philip Melanchthon. (born Philipp Schwartzerdt; 16 February 1497 – 19 April 1560) was a German Lutheran reformer, collaborator with Martin Luther, the first systematic theologian of the Protestant Reformation, intellectual leader of the Lu ...

and Johannes Brenz

Johann (Johannes) Brenz (24 June 1499 – 11 September 1570) was a German Lutheran theologian and the Protestant Reformer of the Duchy of Württemberg.

Early advocacy of the Reformation

Brenz was born in the then Imperial City of Weil der S ...

, with some other German Lutherans, actually started in 1552 on the journey to Trent. Brenz offered a confession and Melanchthon, who got no farther than Nuremberg, took with him the ''Confessio Saxonica''. But the refusal to give the Protestants the vote and the consternation produced by the success of Maurice in his campaign against Charles V in 1552 effectually put an end to Protestant cooperation.

#To effect a reformation in discipline or administration. This object had been one of the causes calling forth the reformatory councils and had been lightly touched upon by the Fifth Council of the Lateran under Pope Julius II. The obvious corruption in the administration of the Church was one of the numerous causes of the Reformation. Twenty-five public sessions were held, but nearly half of them were spent in solemn formalities. The chief work was done in committees or congregations. The entire management was in the hands of the papal legate. The liberal elements lost out in the debates and voting. The council abolished some of the most notorious abuses and introduced or recommended disciplinary reforms affecting the sale of indulgences, the morals of convents, the education of the clergy, the non-residence of bishops (also bishops having plurality of benefice

A benefice () or living is a reward received in exchange for services rendered and as a retainer for future services. The Roman Empire used the Latin term as a benefit to an individual from the Empire for services rendered. Its use was adopted by ...

s, which was fairly common), and the careless fulmination of censures, and forbade duelling. Although evangelical sentiments were uttered by some of the members in favour of the supreme authority of the Scriptures and justification by faith, no concession whatsoever was made to Protestantism.

#The Church is the ultimate interpreter of Scripture.Catechism of the Catholic Church Paragraph 85 Also, the Bible and church tradition (the tradition that composed part of the Catholic faith) were equally and independently authoritative.

#The relationship of faith and works in salvation was defined, following controversy over Martin Luther's doctrine of "justification by faith alone

''Justificatio sola fide'' (or simply ''sola fide''), meaning justification by faith alone, is a soteriological doctrine in Christian theology commonly held to distinguish the Lutheran and Reformed traditions of Protestantism, among others, fro ...

".

#Other Catholic practices that drew the ire of reformers within the Church, such as indulgences, pilgrimages, the veneration of saint

In religious belief, a saint is a person who is recognized as having an exceptional degree of Q-D-Š, holiness, likeness, or closeness to God. However, the use of the term ''saint'' depends on the context and Christian denomination, denominat ...

s and relics, and the veneration of the Virgin Mary were strongly reaffirmed, though abuses of them were forbidden. Decrees concerning sacred music and religious art, though inexplicit, were subsequently amplified by theologians and writers to condemn many types of Renaissance and medieval styles and iconographies

Iconology is a method of interpretation in cultural history and the history of the visual arts used by Aby Warburg, Erwin Panofsky and their followers that uncovers the cultural, social, and historical background of themes and subjects in the visu ...

, impacting heavily on the development of these art forms.

The doctrinal decisions of the council are set forth in decrees (''decreta''), which are divided into chapters (''capita''), which contain the positive statement of the conciliar dogmas, and into short canons (''canones''), which condemn the dissenting Protestant views with the concluding ''anathema sit'' ("let him be anathema").

Decrees

The doctrinal acts are as follows: after reaffirming the Niceno-Constantinopolitan Creed (third session), the decree was passed (fourth session) confirming that the deuterocanonical books were on a par with the other books of the canon (against Luther's placement of these books in the Apocrypha of

The doctrinal acts are as follows: after reaffirming the Niceno-Constantinopolitan Creed (third session), the decree was passed (fourth session) confirming that the deuterocanonical books were on a par with the other books of the canon (against Luther's placement of these books in the Apocrypha of his edition

His or HIS may refer to:

Computing

* Hightech Information System, a Hong Kong graphics card company

* Honeywell Information Systems

* Hybrid intelligent system

* Microsoft Host Integration Server

Education

* Hangzhou International School, ...

) and coordinating church tradition with the Scriptures as a rule of faith. The Vulgate translation was affirmed to be authoritative for the text of Scripture.

Justification

Justification may refer to:

* Justification (epistemology), a property of beliefs that a person has good reasons for holding

* Justification (jurisprudence), defence in a prosecution for a criminal offenses

* Justification (theology), God's act of ...

(sixth session) was declared to be offered upon the basis of human cooperation with divine grace as opposed to the Protestant doctrine of passive reception of grace. Understanding the Protestant "faith alone

''Justificatio sola fide'' (or simply ''sola fide''), meaning justification by faith alone, is a soteriological doctrine in Christian theology commonly held to distinguish the Lutheran and Reformed traditions of Protestantism, among others, fro ...

" doctrine to be one of simple human confidence in Divine Mercy

The Divine Mercy is a form of God's compassion, an act of grace based on trust or forgiveness. In Catholicism, it refers specifically to a devotion which had its origin in the apparitions of Jesus Christ reported by Faustina Kowalska.

Etymolog ...

, the Council rejected the " vain confidence" of the Protestants, stating that no one can know who has received the grace of God. Furthermore, the Council affirmed—against some Protestants—that the grace of God can be forfeited through mortal sin.

The greatest weight in the Council's decrees is given to the sacrament

A sacrament is a Christianity, Christian Rite (Christianity), rite that is recognized as being particularly important and significant. There are various views on the existence and meaning of such rites. Many Christians consider the sacraments ...

s. The seven sacraments were reaffirmed and the Eucharist

The Eucharist (; from Greek , , ), also known as Holy Communion and the Lord's Supper, is a Christian rite that is considered a sacrament in most churches, and as an ordinance in others. According to the New Testament, the rite was instit ...

pronounced to be a true propitiatory sacrifice as well as a sacrament, in which the bread and wine were consecrated

Consecration is the solemn dedication to a special purpose or service. The word ''consecration'' literally means "association with the sacred". Persons, places, or things can be consecrated, and the term is used in various ways by different grou ...

into the Eucharist (thirteenth and twenty-second sessions). The term transubstantiation was used by the Council, but the specific Aristotelian explanation given by Scholasticism

Scholasticism was a medieval school of philosophy that employed a critical organic method of philosophical analysis predicated upon the Aristotelian 10 Categories. Christian scholasticism emerged within the monastic schools that translate ...

was not cited as dogmatic. Instead, the decree states that Christ is "really, truly, substantially present" in the consecrated forms. The sacrifice of the Mass was to be offered for dead and living alike and in giving to the apostles the command "do this in remembrance of me," Christ conferred upon them a sacerdotal power. The practise of withholding the cup from the laity was confirmed (twenty-first session) as one which the Church Fathers

The Church Fathers, Early Church Fathers, Christian Fathers, or Fathers of the Church were ancient and influential Christian theologians and writers who established the intellectual and doctrinal foundations of Christianity. The historical per ...

had commanded for good and sufficient reasons; yet in certain cases the Pope was made the supreme arbiter as to whether the rule should be strictly maintained. On the language of the Mass, "contrary to what is often said", the council condemned the belief that only vernacular languages should be used, while insisting on the use of Latin.O'Malley, 31

Ordination (twenty-third session) was defined to imprint an indelible character on the soul. The priesthood of the New Testament takes the place of the Levitical priesthood. To the performance of its functions, the consent of the people is not necessary.

In the decrees on marriage (twenty-fourth session) the excellence of the celibate

Celibacy (from Latin ''caelibatus'') is the state of voluntarily being unmarried, sexually abstinent, or both, usually for religious reasons. It is often in association with the role of a religious official or devotee. In its narrow sense, th ...

state was reaffirmed, concubinage condemned and the validity of marriage made dependent upon the wedding taking place before a priest and two witnesses, although the lack of a requirement for parental consent ended a debate that had proceeded from the 12th century. In the case of a divorce, the right of the innocent party to marry again was denied so long as the other party was alive, even if the other party had committed adultery. However the council "refused … to assert the necessity or usefulness of clerical celibacy

Clerical celibacy is the requirement in certain religions that some or all members of the clergy be unmarried. Clerical celibacy also requires abstention from deliberately indulging in sexual thoughts and behavior outside of marriage, because the ...

".

In the twenty-fifth and last session, the doctrines of purgatory, the invocation of saint

In religious belief, a saint is a person who is recognized as having an exceptional degree of Q-D-Š, holiness, likeness, or closeness to God. However, the use of the term ''saint'' depends on the context and Christian denomination, denominat ...

s and the veneration of relic

In religion, a relic is an object or article of religious significance from the past. It usually consists of the physical remains of a saint or the personal effects of the saint or venerated person preserved for purposes of veneration as a tangi ...

s were reaffirmed, as was also the efficacy of indulgences as dispensed by the Church according to the power given her, but with some cautionary recommendations, and a ban on the sale of indulgences. Short and rather inexplicit passages concerning religious images, were to have great impact on the development of Catholic Church art. Much more than the Second Council of Nicaea (787) the Council fathers of Trent stressed the pedagogical purpose of Christian images.

The council appointed, in 1562 (eighteenth session), a commission to prepare a list of forbidden books (''Index Librorum Prohibitorum

The ''Index Librorum Prohibitorum'' ("List of Prohibited Books") was a list of publications deemed heretical or contrary to morality by the Sacred Congregation of the Index (a former Dicastery of the Roman Curia), and Catholics were forbidden ...

''), but it later left the matter to the Pope. The preparation of a catechism

A catechism (; from grc, κατηχέω, "to teach orally") is a summary or exposition of doctrine and serves as a learning introduction to the Sacraments traditionally used in catechesis, or Christian religious teaching of children and adult c ...

and the revision of the Breviary

A breviary (Latin: ''breviarium'') is a liturgical book used in Christianity for praying the canonical hours, usually recited at seven fixed prayer times.

Historically, different breviaries were used in the various parts of Christendom, such a ...

and Missal

A missal is a liturgical book containing instructions and texts necessary for the celebration of Mass throughout the liturgical year. Versions differ across liturgical tradition, period, and purpose, with some missals intended to enable a pries ...

were also left to the pope. The catechism embodied the council's far-reaching results, including reforms and definitions of the sacraments, the Scriptures, church dogma, and duties of the clergy.

Ratification and promulgation

On adjourning, the Council asked the supreme pontiff to ratify all its decrees and definitions. This petition was complied with byPope Pius IV

Pope Pius IV ( it, Pio IV; 31 March 1499 – 9 December 1565), born Giovanni Angelo Medici, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 25 December 1559 to his death in December 1565. Born in Milan, his family considered ...

, on 26 January 1564, in the papal bull, '' Benedictus Deus'', which enjoins strict obedience upon all Catholics and forbids, under pain of ex-communication, all unauthorised interpretation, reserving this to the Pope alone and threatens the disobedient with "the indignation of Almighty God and of his blessed apostles, Peter and Paul." Pope Pius appointed a commission of cardinals to assist him in interpreting and enforcing the decrees.

The ''Index Librorum Prohibitorum

The ''Index Librorum Prohibitorum'' ("List of Prohibited Books") was a list of publications deemed heretical or contrary to morality by the Sacred Congregation of the Index (a former Dicastery of the Roman Curia), and Catholics were forbidden ...

'' was announced in 1564 and the following books were issued with the papal imprimatur: the Profession of the Tridentine Faith and the Tridentine Catechism (1566), the Breviary (1568), the Missal (1570) and the Vulgate (1590 and then 1592).

The decrees of the council were acknowledged in Italy, Portugal, Poland and by the Catholic princes of Germany at the Diet of Augsburg

The Diet of Augsburg were the meetings of the Imperial Diet of the Holy Roman Empire held in the German city of Augsburg. Both an Imperial City and the residence of the Augsburg prince-bishops, the town had hosted the Estates in many such sess ...

in 1566. Philip II of Spain

Philip II) in Spain, while in Portugal and his Italian kingdoms he ruled as Philip I ( pt, Filipe I). (21 May 152713 September 1598), also known as Philip the Prudent ( es, Felipe el Prudente), was King of Spain from 1556, King of Portugal from ...

accepted them for Spain, the Netherlands and Sicily inasmuch as they did not infringe the royal prerogative. In France, they were officially recognised by the king only in their doctrinal parts. Although the disciplinary or moral reformatory decrees were never published by the throne, they received official recognition at provincial synods and were enforced by the bishops. Holy Roman Emperors Ferdinand I Ferdinand I or Fernando I may refer to:

People

* Ferdinand I of León, ''the Great'' (ca. 1000–1065, king from 1037)

* Ferdinand I of Portugal and the Algarve, ''the Handsome'' (1345–1383, king from 1367)

* Ferdinand I of Aragon and Sicily, '' ...

and Maximilian II never recognized the existence of any of the decrees. No attempt was made to introduce it into England. Pius IV sent the decrees to Mary, Queen of Scots, with a letter dated 13 June 1564, requesting her to publish them in Scotland, but she dared not do it in the face of John Knox

John Knox ( gd, Iain Cnocc) (born – 24 November 1572) was a Scottish minister, Reformed theologian, and writer who was a leader of the country's Reformation. He was the founder of the Presbyterian Church of Scotland.

Born in Giffordgat ...

and the Reformation.

These decrees were later supplemented by the First Vatican Council

The First Ecumenical Council of the Vatican, commonly known as the First Vatican Council or Vatican I was convoked by Pope Pius IX on 29 June 1868, after a period of planning and preparation that began on 6 December 1864. This, the twentieth ecu ...

of 1870.

Publication of documents

A comprehensive history is found in Hubert Jedin's ''The History of the Council of Trent (Geschichte des Konzils von Trient)'' with about 2500 pages in four volumes: ''The History of the Council of Trent: The fight for a Council'' (Vol I, 1951); ''The History of the Council of Trent: The first Sessions in Trent (1545–1547)'' (Vol II, 1957); ''The History of the Council of Trent: Sessions in Bologna 1547–1548 and Trento 1551–1552'' (Vol III, 1970, 1998); ''The History of the Council of Trent: Third Period and Conclusion'' (Vol IV, 1976). The canons and decrees of the council have been published very often and in many languages. The first issue was by Paulus Manutius (Rome, 1564). Commonly used Latin editions are by Judocus Le Plat (Antwerp, 1779) and by Johann Friedrich von Schulte and Aemilius Ludwig Richter (Leipzig, 1853). Other editions are in vol. vii. of the ''Acta et decreta conciliorum recentiorum. Collectio Lacensis'' (7 vols., Freiburg, 1870–90), reissued as independent volume (1892); ''Concilium Tridentinum: Diariorum, actorum, epistularum, … collectio'', ed. Sebastianus Merkle (4 vols., Freiburg, 1901 sqq.); as well as Mansi, ''Concilia'', xxxv. 345 sqq. Note alsoCarl Mirbt

Carl Theodor Mirbt (July 21, 1860 in Gnadenfrei, Province of Silesia – September 27, 1929 in Göttingen) was a German Protestant church historian. He was a member of the history of religions school.

Biography

Mirbt studied theology from 1880 to ...

, ''Quellen'', 2d ed, pp. 202–255. An English edition is by James Waterworth (London, 1848; ''With Essays on the External and Internal History of the Council'').

The original acts and debates of the council, as prepared by its general secretary, Bishop Angelo Massarelli, in six large folio volumes, are deposited in the Vatican Library and remained there unpublished for more than 300 years and were brought to light, though only in part, by Augustin Theiner, priest of the oratory (d. 1874), in ''Acta genuina sancti et oecumenici Concilii Tridentini nunc primum integre edita'' (2 vols., Leipzig, 1874).

Most of the official documents and private reports, however, which bear upon the council, were made known in the 16th century and since. The most complete collection of them is that of J. Le Plat, ''Monumentorum ad historicam Concilii Tridentini collectio'' (7 vols., Leuven, 1781–87). New materials(Vienna, 1872); by JJI von Döllinger ''(Ungedruckte Berichte und Tagebücher zur Geschichte des Concilii von Trient)'' (2 parts, Nördlingen, 1876); and August von Druffel, ''Monumenta Tridentina'' (Munich, 1884–97).

List of doctrinal decrees

Protestant response

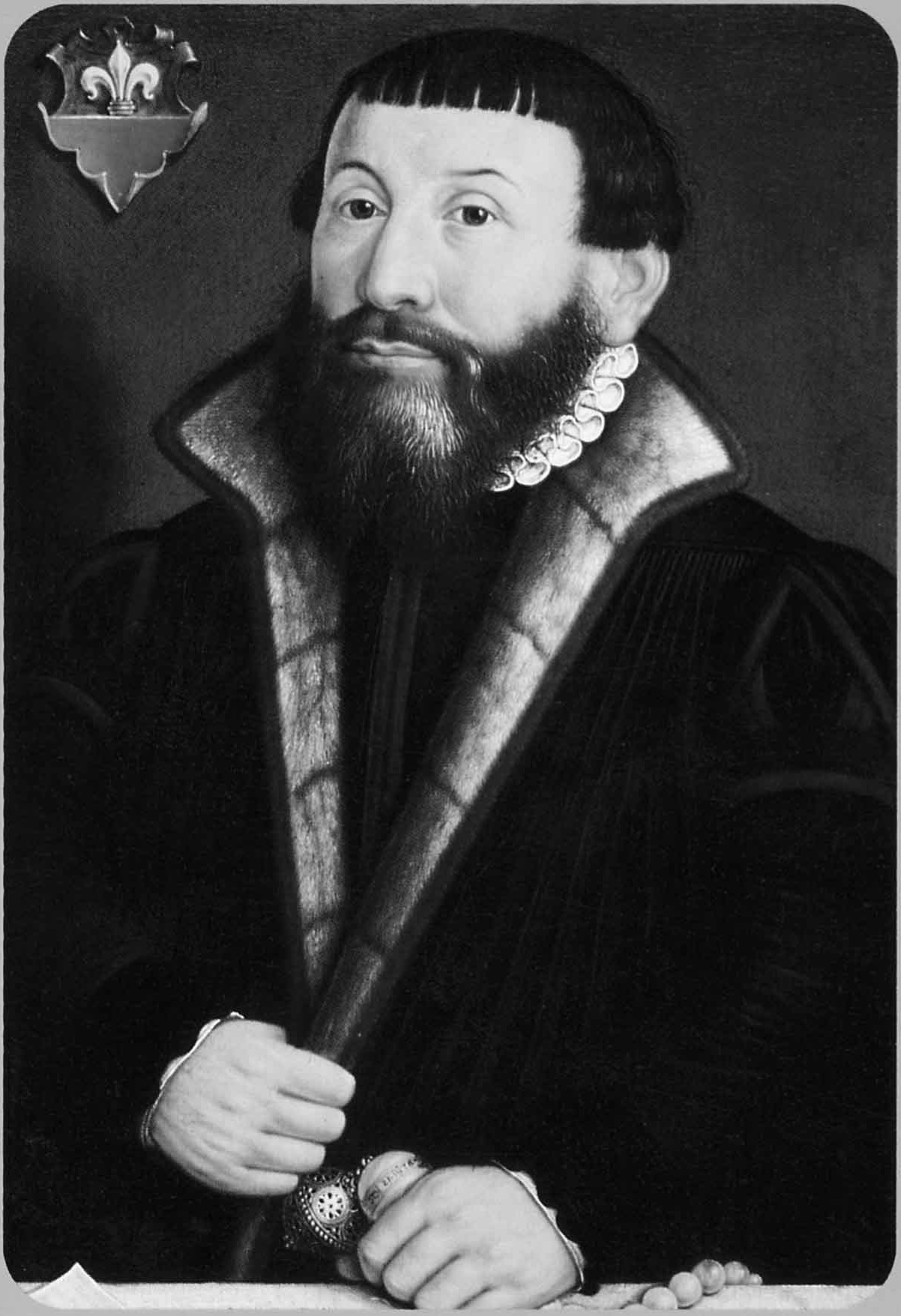

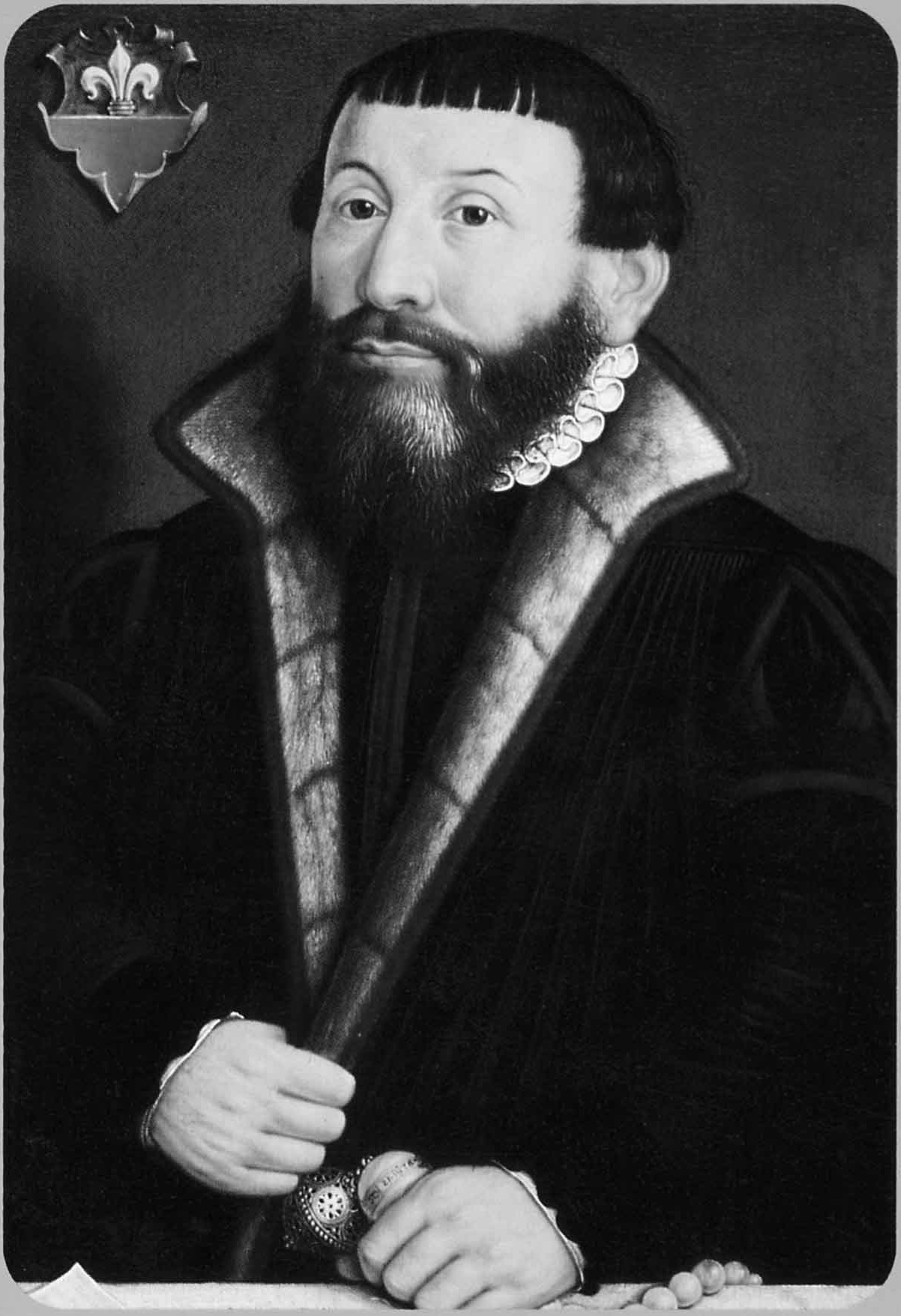

Out of 87 books written between 1546 and 1564 attacking the Council of Trent, 41 were written by Pier Paolo Vergerio, a former papal nuncio turned Protestant Reformer. The 1565–73 ''Examen decretorum Concilii Tridentini'' (''

Out of 87 books written between 1546 and 1564 attacking the Council of Trent, 41 were written by Pier Paolo Vergerio, a former papal nuncio turned Protestant Reformer. The 1565–73 ''Examen decretorum Concilii Tridentini'' (''Examination of the Council of Trent

''Examination of the Council of Trent'' (Latin: ''Examen Concilii Tridentini'', 1565–73) is a large theological work of Lutheran Reformer Martin Chemnitz.

The work was published in Latin as four volumes. It includes the decrees and canons of th ...

'') by Martin Chemnitz was the main Lutheran response to the Council of Trent. Making extensive use of scripture and patristic sources, it was presented in response to a polemical writing which Diogo de Payva de Andrada had directed against Chemnitz. The ''Examen'' had four parts: Volume I examined sacred scripture, free will, original sin, justification, and good works. Volume II examined the sacraments, including baptism, confirmation, the sacrament of the eucharist, communion under both kinds, the mass, penance, extreme unction, holy orders, and matrimony. Volume III examined virginity, celibacy, purgatory, and the invocation of saints. Volume IV examined the relics of the saints, images, indulgences, fasting, the distinction of foods, and festivals.

In response, Andrada wrote the five-part ''Defensio Tridentinæ fidei

''Defensio Tridentinæ fidei'' (full title: ''Defensio Tridentinæ fidei catholicæ et integerrimæ quinque libris compræhensa aduersus hæreticorum detestabiles calumnias & præsertim Martini Kemnicij Germani'', or "A Defence of the Catholic and ...

'',Defensio

', 716 pages, free on Google Books. which was published posthumously in 1578. However, the ''Defensio'' did not circulate as extensively as the ''Examen'', nor were any full translations ever published. A French translation of the ''Examen'' by Eduard Preuss was published in 1861. German translations were published in 1861, 1884, and 1972. In English, a complete translation by Fred Kramer drawing from the original Latin and the 1861 German was published beginning in 1971.

See also

* Nicolas Psaume, bishop of Verdun * Black Legend (Spain) * PoperyNotes

References

* Bühren, Ralf van: ''Kunst und Kirche im 20. Jahrhundert. Die Rezeption des Zweiten Vatikanischen Konzils'' (Konziliengeschichte, Reihe B: Untersuchungen), Paderborn 2008, * O'Malley, John W., in ''The Sensuous in the Counter-Reformation Church'', Eds: Marcia B. Hall, Tracy E. Cooper, 2013, Cambridge University Press,google books

James Waterworth (ed.), ''The Canons and Decrees of the Sacred and Oecumenical Council of Trent'' (1848)

Further reading

* (with '' imprimatur'' of cardinal Farley) *Paolo Sarpi

Paolo Sarpi (14 August 1552 – 15 January 1623) was a Venetian historian, prelate, scientist, canon lawyer, and statesman active on behalf of the Venetian Republic during the period of its successful defiance of the papal interdict (1605–16 ...

, ''Historia del Concilio Tridentino'', London: John Bill,1619 (''History of the Council of Trent'', English translation by Nathaniel Brent

Sir Nathaniel Brent (c. 1573 – 6 November 1652) was an English college head.

Life

He was the son of Anchor Brent of Little Wolford, Warwickshire, where he was born about 1573. He became 'portionist,' or postmaster, of Merton College, Oxford, i ...

, London 1620, 1629 and 1676)

* Francesco Sforza Pallavicino, ''Istoria del concilio di Trento''. In Roma, nella stamperia d'Angelo Bernabò dal Verme erede del Manelfi: per Giovanni Casoni libraro, 1656-7

* John W. O'Malley: ''Trent: What Happened at the Council'', Cambridge (Massachusetts), The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2013,

* Hubert Jedin: ''Entstehung und Tragweite des Trienter Dekrets über die Bilderverehrung'', in: Tübinger Theologische Quartalschrift 116, 1935, pp. 143–88, 404–29

* Hubert Jedin: ''Geschichte des Konzils von Trient'', 4 vol., Freiburg im Breisgau 1949–1975 (A History of the Council of Trent, 2 vol., London 1957 and 1961)

* Hubert Jedin: ''Konziliengeschichte'', Freiburg im Breisgau 1959

* Mullett, Michael A. "The Council of Trent and the Catholic Reformation", in his ''The Catholic Reformation'' (London: Routledge, 1999, , pbk.), p. 29-68. ''N.B''.: The author also mentions the Council elsewhere in his book.

* Schroeder, H. J., ed. and trans. ''The Canons and Decrees of the Council of Trent: English Translation'', trans. nd introducedby H. J. Schroeder. Rockford, Ill.: TAN Books and Publishers, 1978. ''N.B''.: "The original 1941 edition contained oththe Latin text and the English translation. This edition contains only the English translation..."; comprises only the Council's dogmatic decrees, excluding the purely disciplinary ones.

* Mathias Mütel: ''Mit den Kirchenvätern gegen Martin Luther? Die Debatten um Tradition und auctoritas patrum auf dem Konzil von Trient'', Paderborn 2017 (= Konziliengeschichte. Reihe B., Untersuchungen)

External links

*The text of the Council of Trent

translated by J. Waterworth, 1848

also on Intratext

ZIP version of the documents of the Council of Trent

{{Authority control 1545 establishments in the Papal States 1563 disestablishments Counter-Reformation

Trent

Trent may refer to:

Places Italy

* Trento in northern Italy, site of the Council of Trent United Kingdom

* Trent, Dorset, England, United Kingdom Germany

* Trent, Germany, a municipality on the island of Rügen United States

* Trent, California, ...

Pope Julius III

Pope Paul III

Pope Pius IV

Pope Pius V

Trent

Trent may refer to:

Places Italy

* Trento in northern Italy, site of the Council of Trent United Kingdom

* Trent, Dorset, England, United Kingdom Germany

* Trent, Germany, a municipality on the island of Rügen United States

* Trent, California, ...

Prince-Bishopric of Trent