Trent Affair on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The ''Trent'' Affair was a

The ''Trent'' Affair was a

On May 18 Russell had instructed Lyons to seek Confederate agreement to abide by the Paris Declaration. Lyons assigned this task to Robert Bunch, the British consul in

On May 18 Russell had instructed Lyons to seek Confederate agreement to abide by the Paris Declaration. Lyons assigned this task to Robert Bunch, the British consul in

Fairfax then boarded ''Trent'' from a cutter. Two cutters carrying a party of twenty men armed with pistols and cutlasses sidled up to ''Trent''. Fairfax, certain that Wilkes was creating an international incident and not wanting to enlarge its scope, ordered his armed escort to remain in the cutter. Upon boarding, Fairfax was escorted to an outraged Captain Moir, and announced that he had orders "to arrest Mr. Mason and Mr. Slidell and their secretaries, and send them prisoners on board the United States war vessel nearby". The crew and passengers then threatened Lieutenant Fairfax, and the armed party in the two cutters beside ''Trent'' responded to the threats by climbing aboard to protect him. Captain Moir refused Fairfax's request for a passenger list, but Slidell and Mason came forward and identified themselves. Moir also refused to allow a search of the vessel for contraband, and Fairfax failed to force the issue which would have required seizing the ship as a prize, arguably an act of war. Mason and Slidell made a formal refusal to go voluntarily with Fairfax, but did not resist when Fairfax's crewmen escorted them to the cutter.

Wilkes would later claim that he believed that ''Trent'' was carrying "highly important dispatches and were endowed with instructions inimical to the United States". Along with the failure of Fairfax to insist on a search of ''Trent'', there was another reason why no papers were found in the luggage that was carried with the envoys. Mason's daughter, writing in 1906, said that the Confederate dispatch bag had been secured by Commander Williams RN, a passenger on ''Trent'', and later delivered to the Confederate envoys in London. This was a clear violation of the Queen's Neutrality Proclamation.

International law required that when "contraband" was discovered on a ship, the ship should be taken to the nearest prize court for adjudication. While this was Wilkes' initial determination, Fairfax argued against this since transferring crew from ''San Jacinto'' to ''Trent'' would leave ''San Jacinto'' dangerously undermanned, and it would seriously inconvenience ''Trents other passengers as well as mail recipients. Wilkes, whose ultimate responsibility it was, agreed and the ship was allowed to proceed to St. Thomas, absent the two Confederate envoys and their secretaries.

''San Jacinto'' arrived in

Fairfax then boarded ''Trent'' from a cutter. Two cutters carrying a party of twenty men armed with pistols and cutlasses sidled up to ''Trent''. Fairfax, certain that Wilkes was creating an international incident and not wanting to enlarge its scope, ordered his armed escort to remain in the cutter. Upon boarding, Fairfax was escorted to an outraged Captain Moir, and announced that he had orders "to arrest Mr. Mason and Mr. Slidell and their secretaries, and send them prisoners on board the United States war vessel nearby". The crew and passengers then threatened Lieutenant Fairfax, and the armed party in the two cutters beside ''Trent'' responded to the threats by climbing aboard to protect him. Captain Moir refused Fairfax's request for a passenger list, but Slidell and Mason came forward and identified themselves. Moir also refused to allow a search of the vessel for contraband, and Fairfax failed to force the issue which would have required seizing the ship as a prize, arguably an act of war. Mason and Slidell made a formal refusal to go voluntarily with Fairfax, but did not resist when Fairfax's crewmen escorted them to the cutter.

Wilkes would later claim that he believed that ''Trent'' was carrying "highly important dispatches and were endowed with instructions inimical to the United States". Along with the failure of Fairfax to insist on a search of ''Trent'', there was another reason why no papers were found in the luggage that was carried with the envoys. Mason's daughter, writing in 1906, said that the Confederate dispatch bag had been secured by Commander Williams RN, a passenger on ''Trent'', and later delivered to the Confederate envoys in London. This was a clear violation of the Queen's Neutrality Proclamation.

International law required that when "contraband" was discovered on a ship, the ship should be taken to the nearest prize court for adjudication. While this was Wilkes' initial determination, Fairfax argued against this since transferring crew from ''San Jacinto'' to ''Trent'' would leave ''San Jacinto'' dangerously undermanned, and it would seriously inconvenience ''Trents other passengers as well as mail recipients. Wilkes, whose ultimate responsibility it was, agreed and the ship was allowed to proceed to St. Thomas, absent the two Confederate envoys and their secretaries.

''San Jacinto'' arrived in

Most Northerners learned of the ''Trent'' capture on November 16 when the news hit afternoon newspapers. By Monday, November 18, the press seemed "universally engulfed in a massive wave of chauvinistic elation". Mason and Slidell, "the caged ambassadors", were denounced as "knaves", "cowards", "snobs", and "cold, cruel, and selfish".

Everyone was eager to present a legal justification for the capture. The British consul in Boston remarked that every other citizen was "walking around with a Law Book under his arm and proving the right of the S. Jacintho to stop H.M.'s

Most Northerners learned of the ''Trent'' capture on November 16 when the news hit afternoon newspapers. By Monday, November 18, the press seemed "universally engulfed in a massive wave of chauvinistic elation". Mason and Slidell, "the caged ambassadors", were denounced as "knaves", "cowards", "snobs", and "cold, cruel, and selfish".

Everyone was eager to present a legal justification for the capture. The British consul in Boston remarked that every other citizen was "walking around with a Law Book under his arm and proving the right of the S. Jacintho to stop H.M.'s

in JSTOR

* Campbell, W. E. "The Trent Affair of 1861,". ''The (Canadian) Army Doctrine and Training Bulletin''. Vol. 2, No. 4, Winter 1999 pp. 56–65 * Carroll, Francis M. "The American Civil War and British Intervention: The Threat of Anglo-American Conflict." ''Canadian Journal of History'' (2012) 47 #1 * Chartrand, Rene. "''Canadian Military Heritage, Vol. II: 1755–1871''", Directorate of History, Department of National Defence of Canada, Ottawa, 1985 * * Donald, David Herbert, Baker, Jean Harvey, and Holt, Michael F. ''The Civil War and Reconstruction''. (2001) * Ferris, Norman B. ''The Trent Affair: A Diplomatic Crisis''. (1977) ; a major historical monograph. * Ferris, Norman B. ''Desperate Diplomacy: William H. Seward's Foreign Policy, 1861'' (1976) * Foreman, Amanda. ''A World on Fire: Britain's Crucial Role in the American Civil War'' (2011

excerpt

* Goodwin, Doris Kearns. ''Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln''. (2005) * Graebner, Norman A. "Northern Diplomacy and European Neutrality", in ''Why the North Won the Civil War'' edited by David Herbert Donald. (1960) (1996 Revision) * Hubbard, Charles M. ''The Burden of Confederate Diplomacy''. (1998) * Jones, Howard. ''Union in Peril: The Crisis Over British Intervention in the Civil War''. (1992) * Jones, Howard. ''Blue & Gray Diplomacy: A History of Union and Confederate Foreign Relations'' (Univ of North Carolina Press, 2010

online

* Mahin, Dean B. ''One War at A Time: The International Dimensions of the Civil War''. (1999) * Monaghan, Jay. ''Abraham Lincoln Deals with Foreign Affairs''. (1945). (1997 edition) * Musicant, Ivan. ''Divided Waters: The Naval History of the Civil War''. (1995) * Nevins, Allan. ''The war for the Union: The Improvised War 1861–1862''. (1959) * Niven, John. ''Salmon P. Chase: A Biography''. (1995) . * Peraino, Kevin. "Lincoln vs. Palmerston" in his ''Lincoln in the World: The Making of a Statesman and the Dawn of American Power'' (2013) pp. 120–69. * Taylor, John M. ''William Henry Seward: Lincoln's Right Hand''. (1991) * Walther, Eric H. ''William Lowndes Yancey: The Coming of the Civil War''. (2006) * Warren, Gordon H. ''Fountain of Discontent: The Trent Affair and Freedom of the Seas'', (1981) * Weigley, Russell F. ''A Great Civil War.'' (Indiana University Press, 2000)

in JSTOR

* Baxter, James P., III. "The British Government and Neutral Rights, 1861–1865." ''American Historical Review'' (1928) 34 #1

in JSTOR

* Fairfax, D. Macneil. "Captain Wilkes's Seizure of Mason and Slidell" in ''Battles and Leaders of the Civil War: North to Antietam'' edited by Robert Underwood Johnson and Clarence Clough Buel. (1885). * Hunt, Capt. O. E. ''The Ordnance Department of the Federal Army'', p. 124–154, New York; 1911 * Moody, John Sheldon, et al. ''The war of the rebellion: a compilation of the official records of the Union and Confederate armies''; Series 3 – Volume 1; United States. War Dept., p. 775 * Petrie, Martin (Capt., 14th) and James, Col. Sir Henry, RE – Topographical and Statistical Dept., War Office, ''Organization, Composition, and Strength of the Army of Great Britain'', London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office; by direction of the Secretary of State for War, 1863 (preface dated Nov., 1862)

Library of Congress Memory Archive for November 8

{{American Civil War, state=collapsed 1861 in the American Civil War 1861 in international relations 1861 in the United Kingdom November 1861 events Maritime incidents in November 1861 Foreign relations during the American Civil War History of the foreign relations of the United States International maritime incidents United Kingdom–United States relations War scare

The ''Trent'' Affair was a

The ''Trent'' Affair was a diplomatic incident {{Refimprove, date=December 2011

An international incident (or diplomatic incident) is a seemingly relatively small or limited action, incident or clash that results in a wider dispute between two or more nation-states. International incidents can ...

in 1861 during the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

that threatened a war between the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

and Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It is ...

. The U.S. Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage o ...

captured two Confederate

Confederacy or confederate may refer to:

States or communities

* Confederate state or confederation, a union of sovereign groups or communities

* Confederate States of America, a confederation of secessionist American states that existed between 1 ...

envoys from a British Royal Mail steamer; the British government protested vigorously. Washington ended the incident by releasing the envoys.

On November 8, 1861, , commanded by Union

Union commonly refers to:

* Trade union, an organization of workers

* Union (set theory), in mathematics, a fundamental operation on sets

Union may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

Music

* Union (band), an American rock group

** ''Un ...

Captain Charles Wilkes

Charles Wilkes (April 3, 1798 – February 8, 1877) was an American naval officer, ship's captain, and explorer. He led the United States Exploring Expedition (1838–1842).

During the American Civil War (1861–1865), he commanded ' during the ...

, intercepted the British mail packet

The mail or post is a system for physically transporting postcards, letters, and parcels. A postal service can be private or public, though many governments place restrictions on private systems. Since the mid-19th century, national postal syst ...

and removed, as contraband

Contraband (from Medieval French ''contrebande'' "smuggling") refers to any item that, relating to its nature, is illegal to be possessed or sold. It is used for goods that by their nature are considered too dangerous or offensive in the eyes o ...

of war, two Confederate envoys: James Murray Mason

James Murray Mason (November 3, 1798April 28, 1871) was an American lawyer and politician. He served as senator from Virginia, having previously represented Frederick County, Virginia, in the Virginia House of Delegates.

A grandson of George Ma ...

and John Slidell

John Slidell (1793July 9, 1871) was an American politician, lawyer, and businessman. A native of New York, Slidell moved to Louisiana as a young man and became a Representative and Senator. He was one of two Confederate diplomats captured by th ...

. The envoys were bound for Britain and France to press the Confederacy's case for diplomatic recognition

Diplomatic recognition in international law is a unilateral declarative political act of a state that acknowledges an act or status of another state or government in control of a state (may be also a recognized state). Recognition can be accorde ...

and to lobby for possible financial and military support.

Public reaction in the United States was to celebrate the capture and rally against Britain, threatening war. In the Confederate states, the hope was that the incident would lead to a permanent rupture in Anglo-American relations

Anglo-Americans are people who are English-speaking inhabitants of Anglo-America. It typically refers to the nations and ethnic groups in the Americas that speak English as a native language, making up the majority of people in the world who spe ...

and possibly even war, or at least diplomatic recognition by Britain. Confederates realized their independence potentially depended on intervention by Britain and France. In Britain, there was widespread disapproval of this violation of neutral rights

Neutral or neutrality may refer to:

Mathematics and natural science Biology

* Neutral organisms, in ecology, those that obey the unified neutral theory of biodiversity

Chemistry and physics

* Neutralization (chemistry), a chemical reaction in ...

and insult to their national honor. The British government demanded an apology and the release of the prisoners and took steps to strengthen its military forces in British North America

British North America comprised the colonial territories of the British Empire in North America from 1783 onwards. English overseas possessions, English colonisation of North America began in the 16th century in Newfoundland (island), Newfound ...

and the North Atlantic.

President Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

and his top advisors did not want to risk war with Britain over this issue. After several tense weeks, the crisis was resolved when the Lincoln administration released the envoys and disavowed Captain Wilkes's actions, although without a formal apology. Mason and Slidell resumed their voyage to Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

.

Background

Relations with the United States were often strained and even verged on war when Britain came near to supporting the Confederacy in the early part of theAmerican Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

. British leaders were constantly annoyed from the 1840s to the 1860s by what they saw as Washington's pandering to the mob, as in the Oregon boundary dispute

The Oregon boundary dispute or the Oregon Question was a 19th-century territorial dispute over the political division of the Pacific Northwest of North America between several nations that had competing territorial and commercial aspirations in ...

of 1844 to 1846. These tensions came to a head during the ''Trent'' affair; this time London would draw the line.

The Confederacy and its president, Jefferson Davis

Jefferson F. Davis (June 3, 1808December 6, 1889) was an American politician who served as the president of the Confederate States from 1861 to 1865. He represented Mississippi in the United States Senate and the House of Representatives as a ...

, believed from the beginning that European dependence on Southern cotton for its textile industry would lead to diplomatic recognition and intervention, in the form of mediation. Historian Charles Hubbard wrote:

The Union's main focus in foreign affairs was just the opposite: to prevent any British recognition of the Confederacy. The issues of the Oregon boundary dispute

The Oregon boundary dispute or the Oregon Question was a 19th-century territorial dispute over the political division of the Pacific Northwest of North America between several nations that had competing territorial and commercial aspirations in ...

, British involvement in Texas

Texas (, ; Spanish language, Spanish: ''Texas'', ''Tejas'') is a state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. At 268,596 square miles (695,662 km2), and with more than 29.1 million residents in 2 ...

, and the Canada–US border dispute had all been resolved in the 1840s, and despite the Pig War of 1859, a relatively minor border incident in the Pacific Northwest, Anglo-American relations had steadily improved throughout the 1850s. Secretary of State William H. Seward

William Henry Seward (May 16, 1801 – October 10, 1872) was an American politician who served as United States Secretary of State from 1861 to 1869, and earlier served as governor of New York and as a United States Senator. A determined oppon ...

, the primary architect of American foreign policy during the war, intended to maintain the policy principles that had served the country well since the American Revolution: non-intervention by the United States in the affairs of other countries and resistance to foreign intervention in the affairs of the United States and other countries in the Western Hemisphere

The Western Hemisphere is the half of the planet Earth that lies west of the prime meridian (which crosses Greenwich, London, United Kingdom) and east of the antimeridian. The other half is called the Eastern Hemisphere. Politically, the term We ...

.

British prime minister Lord Palmerston

Henry John Temple, 3rd Viscount Palmerston, (20 October 1784 – 18 October 1865) was a British statesman who was twice Prime Minister of the United Kingdom in the mid-19th century. Palmerston dominated British foreign policy during the period ...

urged a policy of neutrality. His international concerns were centered in Europe, where both Napoleon III

Napoleon III (Charles Louis Napoléon Bonaparte; 20 April 18089 January 1873) was the first President of France (as Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte) from 1848 to 1852 and the last monarch of France as Emperor of the French from 1852 to 1870. A nephew ...

's ambitions in Europe and Bismarck's rise in Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an em ...

were occurring. During the Civil War, British reactions to American events were shaped by past British policies and their own national interests, both strategically and economically. In the Western Hemisphere, as relations with the United States improved, Britain had become cautious about confronting the United States over issues in Central America

Central America ( es, América Central or ) is a subregion of the Americas. Its boundaries are defined as bordering the United States to the north, Colombia to the south, the Caribbean Sea to the east, and the Pacific Ocean to the west. ...

.

As a naval power, Britain had a long record of insisting that neutral nations honor its blockades of hostile countries. From the earliest days of the war, that perspective would guide the British away from taking any action that might have been viewed in Washington as a direct challenge to the Union blockade. From the perspective of the South, British policy amounted to ''de facto'' support for the Union blockade and caused great frustration.

The Russian Minister in Washington, Eduard de Stoeckl

Eduard Andreevich Stoeckl (russian: Эдуард Андреевич Стекль) (1804 in Constantinople – January 26, 1892 in Paris) was a Russian diplomat best known today for having negotiated the American purchase of Alaska on behalf of ...

, noted, "The Cabinet of London is watching attentively the internal dissensions of the Union and awaits the result with an impatience which it has difficulty in disguising." De Stoeckl advised his government that Britain would recognize the Confederate States at its earliest opportunity. Cassius Clay

Muhammad Ali (; born Cassius Marcellus Clay Jr.; January 17, 1942 – June 3, 2016) was an American professional boxer and activist. Nicknamed "The Greatest", he is regarded as one of the most significant sports figures of the 20th century, a ...

, the US minister in Russia, stated, "I saw at a glance where the feeling of England was. They hoped for our ruin! They are jealous of our power. They care neither for the South nor the North. They hate both."

At the beginning of the Civil War, the U.S. minister to the Court of St. James was Charles Francis Adams. He made clear that Washington considered the war strictly an internal insurrection affording the Confederacy no rights under international law. Any movement by Britain towards officially recognizing the Confederacy would be considered an unfriendly act towards the United States. Seward's instructions to Adams included the suggestion that it be made clear to Britain that a nation with widely-scattered possessions, as well as a homeland that included Scotland and Ireland, should be very wary of "seting

Ing, ING or ing may refer to:

Art and media

* '' ...ing'', a 2003 Korean film

* i.n.g, a Taiwanese girl group

* The Ing, a race of dark creatures in the 2004 video game '' Metroid Prime 2: Echoes''

* "Ing", the first song on The Roches' 1992 ...

a dangerous precedent".

Lord Lyons

Richard Bickerton Pemell Lyons, 1st Earl Lyons (26 April 1817 – 5 December 1887) was a British diplomat, who was the favourite diplomat of Queen Victoria, during the four great crises of the second half of the 19th century: Italian unificat ...

, an experienced diplomat, was the British minister to the US. He warned London about Seward:

Despite his distrust of Seward, Lyons, throughout 1861, maintained a "calm and measured" diplomacy that contributed to a peaceful resolution to the ''Trent'' crisis.

Issue of diplomatic recognition (February–August 1861)

The ''Trent'' affair did not erupt as a major crisis until late November 1861. The first link in the chain of events occurred in February 1861, when the Confederacy created a three person European delegation consisting ofWilliam Lowndes Yancey

William Lowndes Yancey (August 10, 1814July 27, 1863) was an American journalist, politician, orator, diplomat and an American leader of the Southern secession movement. A member of the group known as the Fire-Eaters, Yancey was one of the m ...

, Pierre Rost, and Ambrose Dudley Mann. Their instructions from Confederate Secretary of State Robert Toombs

Robert Augustus Toombs (July 2, 1810 – December 15, 1885) was an American politician from Georgia, who was an important figure in the formation of the Confederacy. From a privileged background as a wealthy planter and slaveholder, Toomb ...

were to explain to these governments the nature and purposes of the southern cause, to open diplomatic relations, and to "negotiate treaties of friendship, commerce, and navigation". Toombs' instructions included a long legal argument on states' rights and the right of secession. Because of the reliance on the double attack of cotton and legality, many important issues were absent from the instructions including the blockade of Southern ports, privateering, trade with the North, slavery, and the informal blockade the Southerners had imposed whereby no cotton was being shipped out.

British leaders—and those on the Continent—generally believed that division of the U.S. was inevitable. Remembering their own unsuccessful attempt to keep their former American colonies in the Empire by force of arms, the British considered Union efforts to resist a ''fait accompli'' to be unreasonable, but they also viewed Union resistance as a fact that they had to deal with. Believing the war's outcome to be predetermined, the British saw any action they could take to encourage the end of the war as a humanitarian gesture. Lyons was instructed by Foreign Secretary Lord Russell to use his own office and any other parties who might promote a settlement of the war.

The commissioners met informally with Russell on May 3. Although word of Fort Sumter

Fort Sumter is a sea fort built on an artificial island protecting Charleston, South Carolina from naval invasion. Its origin dates to the War of 1812 when the British invaded Washington by sea. It was still incomplete in 1861 when the Battl ...

had just reached London, the immediate implications of open warfare were not discussed at the meeting. Instead the envoys emphasized the peaceful intent of their new nation and the legality of secession as a remedy to Northern violations of states' rights. They closed with their strongest argument: the importance of cotton to Europe. Slavery was discussed only when Russell asked Yancey whether the international slave trade

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

would be reopened by the Confederacy (a position Yancey had advocated in recent years); Yancey's reply was that this was not part of the Confederacy's agenda. Russell was noncommittal, promising the matters raised would be discussed with the full Cabinet.

In the meantime, the British were attempting to determine what official stance they should have to the war. On May 13, 1861, on the recommendation of Russell, Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until Death and state funeral of Queen Victoria, her death in 1901. Her reign of 63 years and 21 ...

issued a declaration of neutrality that served as recognition of Southern belligerency

A belligerent is an individual, group, country, or other entity that acts in a hostile manner, such as engaging in combat. The term comes from the Latin ''bellum gerere'' ("to wage war"). Unlike the use of ''belligerent'' as an adjective meaning ...

—a status that provided Confederate ships the same privileges in foreign ports that U.S. ships received. Confederate ships could obtain fuel, supplies and repairs in neutral ports but could not secure military equipment or arms. The availability of Britain's far-flung colonial ports made it possible for Confederate ships to pursue Union shipping throughout much of the world. France, Spain, the Netherlands, and Brazil followed suit. Belligerency also gave the Confederate government the opportunity to purchase supplies, contract with British companies, and purchase a navy to search out and seize Union ships. The Queen's proclamation made clear that Britons were prohibited from joining the military of either side, equipping any ships for military use in the war, breaking any proper blockade, and from transporting military goods, documents, or personnel to either side.

On May 18, Adams met with Russell to protest the declaration of neutrality. Adams argued that Great Britain had recognized a state of belligerency "before they he Confederacyhad ever showed their capacity to maintain any kind of warfare whatever, except within one of their own harbors under every possible advantage ��it considered them a maritime power before they had ever exhibited a single privateer upon the ocean." The major United States concern at this point was that the recognition of belligerency was the first step towards diplomatic recognition. While Russell indicated that recognition was not currently being considered, he would not rule it out in the future, although he did agree to notify Adams if the government's position changed.

Meanwhile, in Washington, Seward was upset with both the proclamation of neutrality and Russell's meetings with the Confederates. In a May 21 letter to Adams, which he instructed Adams to share with the British, Seward protested the British reception of the Confederate envoys and ordered Adams to have no dealings with the British as long as they were meeting with them. Formal recognition would make Britain an enemy of the United States. President Lincoln reviewed the letter, softened the language, and told Adams not to give Russell a copy but to limit himself to quoting only those portions that Adams thought appropriate. Adams in turn was shocked by even the revised letter, feeling that it almost amounted to a threat to wage war against all of Europe. When he met with Russell on June 12, after receiving the dispatch, Adams was told that Great Britain had often met with representatives of rebels against nations that Great Britain was at peace with, but that he had no further intention of meeting with the Confederate mission.

Further problems developed over possible diplomatic recognition when, in mid-August, Seward became aware that Britain was secretly negotiating with the Confederacy in order to obtain its agreement to abide by the Declaration of Paris

The Paris Declaration respecting Maritime Law of 16 April 1856 was an international multilateral treaty agreed to by the warring parties in the Crimean War gathered at the Congress at Paris after the peace treaty of Paris had been signed in Marc ...

. The 1856 Declaration of Paris prohibited signatories from commissioning privateers

A privateer is a private person or ship that engages in maritime warfare under a commission of war. Since robbery under arms was a common aspect of seaborne trade, until the early 19th century all merchant ships carried arms. A sovereign or deleg ...

against other signatories, protected neutral goods shipped to belligerents except for "contrabands of war", and recognized blockades only if they were proved effective. The United States had failed to sign the treaty originally, but after the Union declared a blockade of the Confederacy, Seward ordered the U.S. ministers to Britain and France to reopen negotiations to restrict the Confederate use of privateers.

On May 18 Russell had instructed Lyons to seek Confederate agreement to abide by the Paris Declaration. Lyons assigned this task to Robert Bunch, the British consul in

On May 18 Russell had instructed Lyons to seek Confederate agreement to abide by the Paris Declaration. Lyons assigned this task to Robert Bunch, the British consul in Charleston, South Carolina

Charleston is the largest city in the U.S. state of South Carolina, the county seat of Charleston County, and the principal city in the Charleston–North Charleston metropolitan area. The city lies just south of the geographical midpoint o ...

, who was directed to contact South Carolina

)''Animis opibusque parati'' ( for, , Latin, Prepared in mind and resources, links=no)

, anthem = " Carolina";" South Carolina On My Mind"

, Former = Province of South Carolina

, seat = Columbia

, LargestCity = Charleston

, LargestMetro = ...

Governor Francis Wilkinson Pickens

Francis Wilkinson Pickens (1805/1807January 25, 1869) was a political Democrat and Governor of South Carolina when that state became the first to secede from the United States.

A cousin of US Senator John C. Calhoun, Pickens was born into the ...

. Bunch exceeded his instructions: he bypassed Pickens, and openly assured the Confederates that agreement to the Paris Declaration was "the first step to ritishrecognition". His indiscretion soon came to Union ears. Robert Mure, a British-born Charleston merchant, was arrested in New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

. Mure, a colonel in the South Carolina militia, had a British diplomatic passport issued by Bunch, and was carrying a British diplomatic pouch (which was searched). The pouch contained some actual correspondence from Bunch to Britain, and also pro-Confederate pamphlets, personal letters from Southerners to European correspondents, and a Confederate dispatch which recounted Bunch's dealings with the Confederacy, including the talk of recognition.

When confronted, Russell admitted that his government was attempting to get agreement from the Confederacy to adhere to the provisions of the treaty relating to neutral goods (but not privateering), but he denied that this was in any way a step towards extending diplomatic relations to the Confederates. Rather than reacting as he had to the earlier recognition of belligerency, Seward let this matter drop. He did demand Bunch's recall, but Russell refused.

Under Napoleon III, France's overall foreign policy objectives were at odds with Britain's, but France generally took positions regarding the Civil War combatants similar to, and often supportive of, Britain's. Cooperation between Britain and France was begun in the U.S. between Henri Mercier, the French minister, and Lyons. For example, on June 15 they tried to see Seward together regarding the proclamation of neutrality, but Seward insisted that he meet with them separately.

Edouard Thouvenel was the French Foreign Minister for all of 1861 until the fall of 1862. He was generally perceived to be pro-Union and was influential in dampening Napoleon's initial inclination towards diplomatic recognition of Confederate independence. Thouvenel met unofficially with Confederate envoy Pierre Rost in June and told him not to expect diplomatic recognition.

William L. Dayton

William Lewis Dayton (February 17, 1807 – December 1, 1864) was an American politician, active first in the Whig Party and later in the Republican Party. In the 1856 presidential election, he became the first Republican vice-presidential ...

of New Jersey was appointed by Lincoln as U.S. minister to France. He had no foreign affairs experience and did not speak French, but was assisted a great deal by the U.S. consul general in Paris, John Bigelow

John Bigelow Sr. (November 25, 1817 – December 19, 1911) was an American lawyer, statesman, and historian who edited the complete works of Benjamin Franklin and the first autobiography of Franklin taken from Franklin's previously lost origina ...

. When Adams made his protest to Russell on the recognition of Confederate belligerency, Dayton made a similar protest to Thouvenel. Napoleon offered "his good office" to the United States in resolving the conflict with the South and Dayton was directed by Seward to acknowledge that "if any mediation were at all admissible, it would be his own that we should seek or accept."

When news of the Confederate victory at the First Battle of Bull Run

The First Battle of Bull Run (the name used by Union forces), also known as the Battle of First Manassas

reached Europe it reinforced British opinion that Confederate independence was inevitable. Hoping to take advantage of this battlefield success, Yancey requested a meeting with Russell but was rebuffed and told that any communications should be in writing. Yancey submitted a long letter on August 14 detailing again the reasons why the Confederacy should receive formal recognition and requesting another meeting with Russell. Russell's August 24 reply, directed to the commissioners "of the so-styled Confederate States of America" reiterated the British position that it considered the war as an internal matter rather than a war for independence. British policy would change only if "the fortune of arms or the more peaceful mode of negotiation shall have determined the respective positions of the two belligerents." No meeting was scheduled and this was the last communication between the British government and the Confederate envoys. When the ''Trent'' Affair erupted in November and December the Confederacy had no effective way to communicate directly with Great Britain and they were left totally out of the negotiation process.

By August 1861, Yancey was sick, frustrated, and ready to resign. In the same month, President Davis had decided that he needed diplomats in Britain and France. Specifically, ministers that would be better suited to serve as Confederate ministers, should the Confederacy achieve international recognition. He selected John Slidell

John Slidell (1793July 9, 1871) was an American politician, lawyer, and businessman. A native of New York, Slidell moved to Louisiana as a young man and became a Representative and Senator. He was one of two Confederate diplomats captured by th ...

of Louisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It is the 20th-smallest by area and the 25th most populous of the 50 U.S. states. Louisiana is borde ...

and James Mason of Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

. Both men were widely respected throughout the South, and had some background in foreign affairs. Slidell had been appointed as a negotiator by President Polk

Polk may refer to:

People

* James K. Polk, 11th president of the United States

* Polk (name), other people with the name

Places

*Polk (CTA), a train station in Chicago, Illinois

* Polk, Illinois, an unincorporated community

* Polk, Missouri ...

at the end of the Mexican War, and Mason had been chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee from 1847 to 1860.

R. M. T. Hunter of Virginia was the new Confederate Secretary of State. His instructions to Mason and Slidell were to emphasize the stronger position of the Confederacy now that it had expanded from seven to eleven states, with the likelihood that Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It shares borders with Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and Delaware and the Atlantic Ocean to ...

, Missouri

Missouri is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking List of U.S. states and territories by area, 21st in land area, it is bordered by eight states (tied for the most with Tennessee ...

, and Kentucky

Kentucky ( , ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States and one of the states of the Upper South. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to the north; West Virginia and Virginia to ...

would also eventually join the new nation. An independent Confederacy would restrict the industrial and maritime ambitions of the United States and lead to a mutually beneficial commercial alliance between Great Britain, France, and the Confederate States. A balance of power would be restored in the Western Hemisphere as the United States' territorial ambitions would be restricted. They were to liken the Confederate situation to Italy's struggles for independence which Britain had supported, and were to quote Russell's own letters which justified that support. Of immediate importance, they were to make a detailed argument against the legality of the Union blockade. Along with their formal written instructions, Mason and Slidell carried a number of documents supporting their positions.

Pursuit and capture (August–November 1861)

The intended departure of the envoys was no secret, and the Union government received daily intelligence on their movements. By October 1 Slidell and Mason were inCharleston, South Carolina

Charleston is the largest city in the U.S. state of South Carolina, the county seat of Charleston County, and the principal city in the Charleston–North Charleston metropolitan area. The city lies just south of the geographical midpoint o ...

. Their original plan was to run the blockade in , a fast steamer, and sail directly to Britain. But the main channel into Charleston was guarded by five Union ships, and ''Nashville''s draft was too deep for any side channels. A night escape was considered, but tides and strong night winds prevented this. An overland route through Mexico

Mexico (Spanish: México), officially the United Mexican States, is a country in the southern portion of North America. It is bordered to the north by the United States; to the south and west by the Pacific Ocean; to the southeast by Guatema ...

and departure from Matamoros was also considered, but the delay of several months was unacceptable.

The steamer ''Gordon'' was suggested as an alternative. She had a shallow enough draft to use the back channels and could make over 12 knots, more than enough to elude Union pursuit. ''Gordon'' was offered to the Confederate government either as a purchase for $62,000 or as a charter for $10,000. The Confederate Treasury could not afford this, but a local cotton broker, George Trenholm

George Alfred Trenholm (February 25, 1807 – December 9, 1876) was a South Carolina businessman, financier, politician, and slaveholding planter who owned several plantations and strongly supported the Confederate States of America. He was a ...

, paid the $10,000 in return for half the cargo space on the return trip. Renamed ''Theodora'', the ship left Charleston at 1 a.m. on October 12, and successfully evaded Union ships enforcing the blockade. On October 14, she arrived at Nassau

Nassau may refer to:

Places Bahamas

*Nassau, Bahamas, capital city of the Bahamas, on the island of New Providence

Canada

*Nassau District, renamed Home District, regional division in Upper Canada from 1788 to 1792

*Nassau Street (Winnipeg), ...

in the Bahamas

The Bahamas (), officially the Commonwealth of The Bahamas, is an island country within the Lucayan Archipelago of the West Indies in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic. It takes up 97% of the Lucayan Archipelago's land area and is home to ...

, but had missed connections with a British steamer going to St. Thomas in the Danish West Indies

The Danish West Indies ( da, Dansk Vestindien) or Danish Antilles or Danish Virgin Islands were a Danish colonization of the Americas, Danish colony in the Caribbean, consisting of the islands of Saint Thomas, U.S. Virgin Islands, Saint Thomas ...

, the main point of departure for British ships from the Caribbean to Britain. They discovered that British mail ships might be anchored in Spanish Cuba, and ''Theodora'' turned southwest towards Cuba. ''Theodora'' appeared off the coast of Cuba on October 15, with her coal bunkers nearly empty. An approaching Spanish warship hailed ''Theodora''. Slidell and George Eustis Jr. went aboard, and were informed that British mail packets docked at Havana

Havana (; Spanish: ''La Habana'' ) is the capital and largest city of Cuba. The heart of the La Habana Province, Havana is the country's main port and commercial center.

, but that the last one had just left, and that the next one, the paddle steamer

A paddle steamer is a steamship or steamboat powered by a steam engine that drives paddle wheels to propel the craft through the water. In antiquity, paddle wheelers followed the development of poles, oars and sails, where the first uses wer ...

, would arrive in three weeks. ''Theodora'' docked in Cárdenas, Cuba on October 16, and Mason and Slidell disembarked. The two men decided to stay in Cardenas before making an overland trip to Havana to catch the next British ship.

Meanwhile, rumors reached the Federal government that Mason and Slidell had escaped aboard ''Nashville''. Union intelligence had not immediately recognized that Mason and Slidell had left Charleston on ''Theodora''. U.S. Navy Secretary Gideon Welles

Gideon Welles (July 1, 1802 – February 11, 1878), nicknamed "Father Neptune", was the United States Secretary of the Navy from 1861 to 1869, a cabinet post he was awarded after supporting Abraham Lincoln in the 1860 election. Although opposed ...

reacted to the rumor that Mason and Slidell had escaped from Charleston by ordering Admiral Samuel F. DuPont to dispatch a fast warship to Britain to intercept ''Nashville''. On October 15, the Union sidewheel steamer , under the command of John B. Marchand, began steaming towards Europe with orders to pursue ''Nashville'' to the English Channel

The English Channel, "The Sleeve"; nrf, la Maunche, "The Sleeve" (Cotentinais) or ( Jèrriais), (Guernésiais), "The Channel"; br, Mor Breizh, "Sea of Brittany"; cy, Môr Udd, "Lord's Sea"; kw, Mor Bretannek, "British Sea"; nl, Het Kana ...

if necessary. ''James Adger'' reached Britain and docked in Southampton

Southampton () is a port city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. It is located approximately south-west of London and west of Portsmouth. The city forms part of the South Hampshire built-up area, which also covers Po ...

Harbor in early November. The British government was aware that the United States would attempt to capture the envoys and believed they were on ''Nashville''. Palmerston Palmerston may refer to:

People

* Christie Palmerston (c. 1851–1897), Australian explorer

* Several prominent people have borne the title of Viscount Palmerston

** Henry Temple, 1st Viscount Palmerston (c. 1673–1757), Irish nobleman an ...

ordered a Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

warship to patrol within the three-mile limit around ''Nashvilles expected port of call, to assure that any capture would occur outside British territorial waters. This would avoid the diplomatic crisis that would result if ''James Adger'' pursued ''Nashville'' into British waters. When ''Nashville'' arrived on November 21, the British were surprised that the envoys were not on board.

The Union steam frigate

Steam frigates (including screw frigates) and the smaller steam corvettes, steam sloops, steam gunboats and steam schooners, were steam-powered warships that were not meant to stand in the line of battle. There were some exceptions like for exam ...

, commanded by Captain Charles Wilkes

Charles Wilkes (April 3, 1798 – February 8, 1877) was an American naval officer, ship's captain, and explorer. He led the United States Exploring Expedition (1838–1842).

During the American Civil War (1861–1865), he commanded ' during the ...

, arrived in St. Thomas on October 13. ''San Jacinto'' had cruised off the African coast for nearly a month before setting course westward with orders to join a U.S. Navy force preparing to attack Port Royal, South Carolina

Port Royal is a List of cities and towns in South Carolina, town on Port Royal Island in Beaufort County, South Carolina, Beaufort County, South Carolina, United States. The population was 14,220 at the 2020 census. It is part of the Hilton Head Is ...

. In St. Thomas, Wilkes learned that the Confederate raider CSS ''Sumter'' had captured three U.S. merchant ships near Cienfuegos

Cienfuegos (), capital of Cienfuegos Province, is a city on the southern coast of Cuba. It is located about from Havana and has a population of 150,000. Since the late 1960s, Cienfuegos has become one of Cuba's main industrial centers, especial ...

in July. Wilkes headed there, despite the unlikelihood that ''Sumter'' would have remained in the area. In Cienfuegos he learned from a newspaper that Mason and Slidell were scheduled to leave Havana on November 7 in the British mail packet , bound first for St. Thomas and then England. He realized that the ship would need to use the "narrow Bahama Channel, the only deepwater route between Cuba and the shallow Grand Bahama Bank". Wilkes discussed legal options with his second in command, Lt. D. M. Fairfax, and reviewed law books on the subject before making plans to intercept. Wilkes adopted the position that Mason and Slidell would qualify as "contraband", subject to seizure by a United States ship. Historians have concluded that there was no legal precedent for the seizure.Campbell, pp. 63–64.

This aggressive decision making was typical of Wilkes' command style. On one hand, he was recognized as "a distinguished explorer, author, and naval officer". On the other, he "had a reputation as a stubborn, overzealous, impulsive, and sometimes insubordinate officer". Treasury officer George Harrington had warned Seward about Wilkes: "He will give us trouble. He has a superabundance of self-esteem and a deficiency of judgment. When he commanded his great exploring mission he court-martialed nearly all his officers; he alone was right, everybody else was wrong."

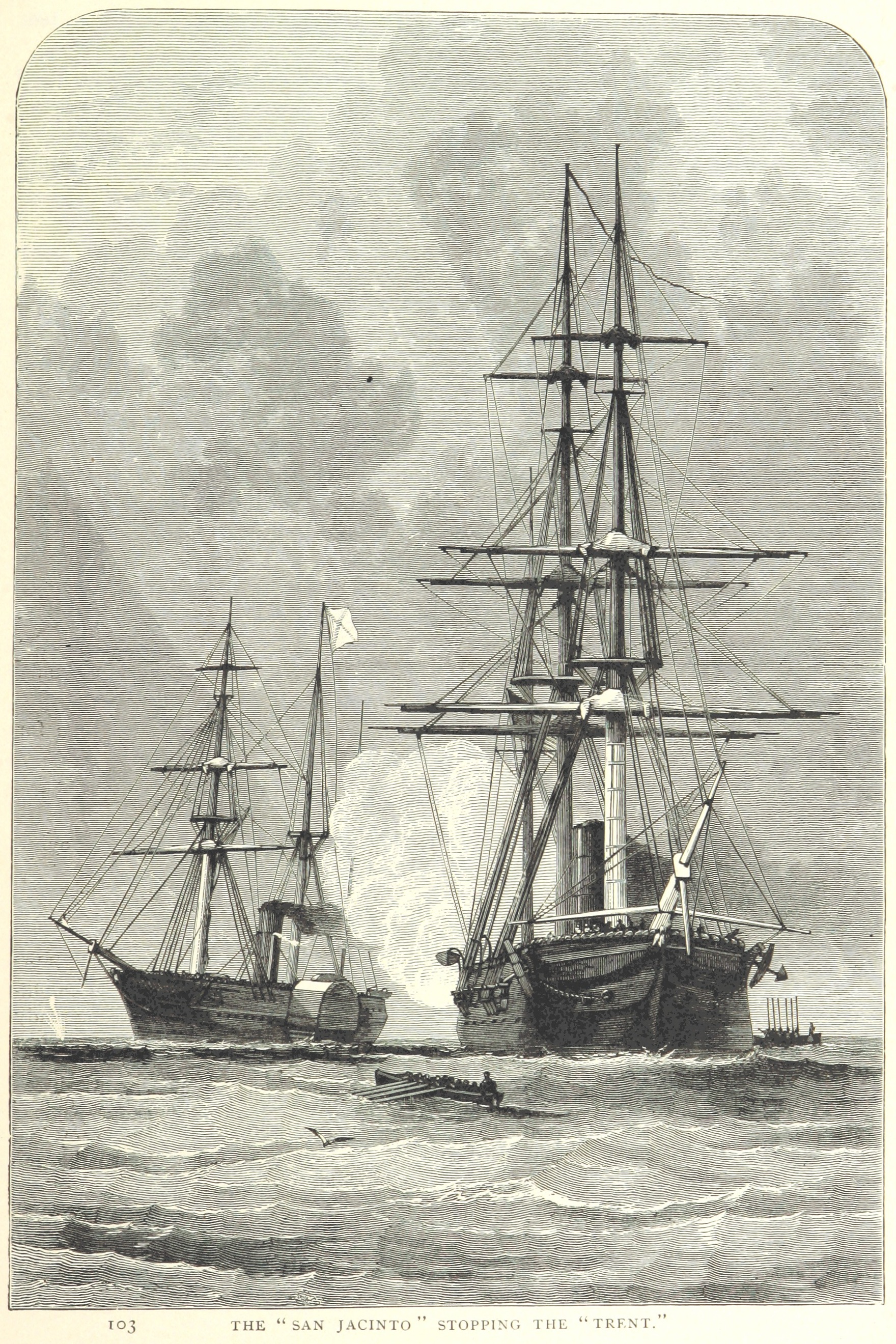

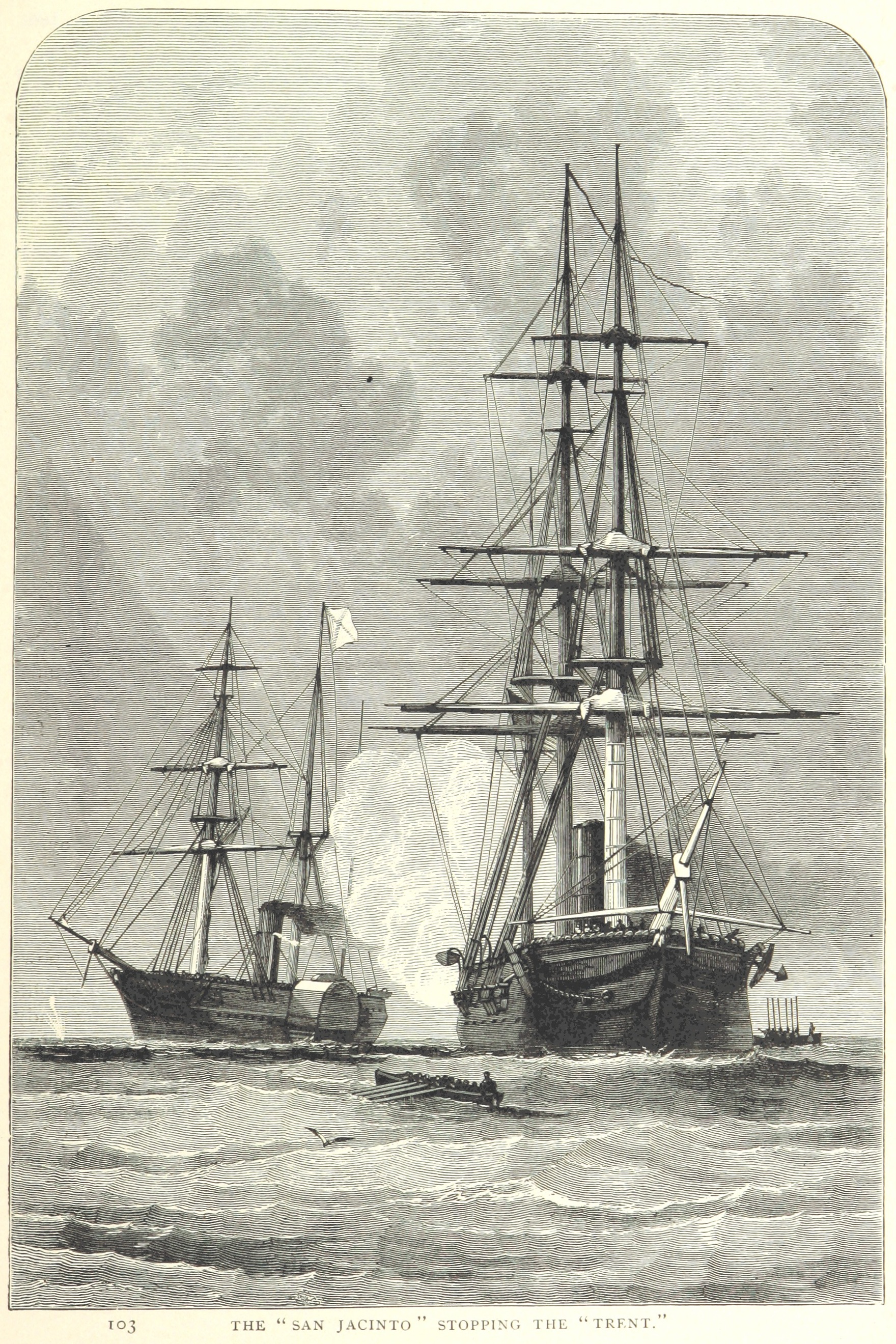

''Trent'' left on November 7 as scheduled, with Mason, Slidell, their secretaries, and Slidell's wife and children aboard. Just as Wilkes had predicted, ''Trent'' passed through Bahama Channel, where ''San Jacinto'' was waiting. Around noon on November 8, lookouts aboard the ''San Jacinto'' spotted ''Trent'', which unfurled the Union Jack

The Union Jack, or Union Flag, is the ''de facto'' national flag of the United Kingdom. Although no law has been passed making the Union Flag the official national flag of the United Kingdom, it has effectively become such through precedent. ...

as it neared. ''San Jacinto'' then fired a shot across the bow of ''Trent'', which Captain James Moir of ''Trent'' ignored. ''San Jacinto'' fired a second shot from her forward pivot gun which landed right in front of ''Trent''. ''Trent'' stopped after the second shot. Lieutenant Fairfax was summoned to the quarterdeck, where Wilkes presented him with the following written instructions:

Fairfax then boarded ''Trent'' from a cutter. Two cutters carrying a party of twenty men armed with pistols and cutlasses sidled up to ''Trent''. Fairfax, certain that Wilkes was creating an international incident and not wanting to enlarge its scope, ordered his armed escort to remain in the cutter. Upon boarding, Fairfax was escorted to an outraged Captain Moir, and announced that he had orders "to arrest Mr. Mason and Mr. Slidell and their secretaries, and send them prisoners on board the United States war vessel nearby". The crew and passengers then threatened Lieutenant Fairfax, and the armed party in the two cutters beside ''Trent'' responded to the threats by climbing aboard to protect him. Captain Moir refused Fairfax's request for a passenger list, but Slidell and Mason came forward and identified themselves. Moir also refused to allow a search of the vessel for contraband, and Fairfax failed to force the issue which would have required seizing the ship as a prize, arguably an act of war. Mason and Slidell made a formal refusal to go voluntarily with Fairfax, but did not resist when Fairfax's crewmen escorted them to the cutter.

Wilkes would later claim that he believed that ''Trent'' was carrying "highly important dispatches and were endowed with instructions inimical to the United States". Along with the failure of Fairfax to insist on a search of ''Trent'', there was another reason why no papers were found in the luggage that was carried with the envoys. Mason's daughter, writing in 1906, said that the Confederate dispatch bag had been secured by Commander Williams RN, a passenger on ''Trent'', and later delivered to the Confederate envoys in London. This was a clear violation of the Queen's Neutrality Proclamation.

International law required that when "contraband" was discovered on a ship, the ship should be taken to the nearest prize court for adjudication. While this was Wilkes' initial determination, Fairfax argued against this since transferring crew from ''San Jacinto'' to ''Trent'' would leave ''San Jacinto'' dangerously undermanned, and it would seriously inconvenience ''Trents other passengers as well as mail recipients. Wilkes, whose ultimate responsibility it was, agreed and the ship was allowed to proceed to St. Thomas, absent the two Confederate envoys and their secretaries.

''San Jacinto'' arrived in

Fairfax then boarded ''Trent'' from a cutter. Two cutters carrying a party of twenty men armed with pistols and cutlasses sidled up to ''Trent''. Fairfax, certain that Wilkes was creating an international incident and not wanting to enlarge its scope, ordered his armed escort to remain in the cutter. Upon boarding, Fairfax was escorted to an outraged Captain Moir, and announced that he had orders "to arrest Mr. Mason and Mr. Slidell and their secretaries, and send them prisoners on board the United States war vessel nearby". The crew and passengers then threatened Lieutenant Fairfax, and the armed party in the two cutters beside ''Trent'' responded to the threats by climbing aboard to protect him. Captain Moir refused Fairfax's request for a passenger list, but Slidell and Mason came forward and identified themselves. Moir also refused to allow a search of the vessel for contraband, and Fairfax failed to force the issue which would have required seizing the ship as a prize, arguably an act of war. Mason and Slidell made a formal refusal to go voluntarily with Fairfax, but did not resist when Fairfax's crewmen escorted them to the cutter.

Wilkes would later claim that he believed that ''Trent'' was carrying "highly important dispatches and were endowed with instructions inimical to the United States". Along with the failure of Fairfax to insist on a search of ''Trent'', there was another reason why no papers were found in the luggage that was carried with the envoys. Mason's daughter, writing in 1906, said that the Confederate dispatch bag had been secured by Commander Williams RN, a passenger on ''Trent'', and later delivered to the Confederate envoys in London. This was a clear violation of the Queen's Neutrality Proclamation.

International law required that when "contraband" was discovered on a ship, the ship should be taken to the nearest prize court for adjudication. While this was Wilkes' initial determination, Fairfax argued against this since transferring crew from ''San Jacinto'' to ''Trent'' would leave ''San Jacinto'' dangerously undermanned, and it would seriously inconvenience ''Trents other passengers as well as mail recipients. Wilkes, whose ultimate responsibility it was, agreed and the ship was allowed to proceed to St. Thomas, absent the two Confederate envoys and their secretaries.

''San Jacinto'' arrived in Hampton Roads

Hampton Roads is the name of both a body of water in the United States that serves as a wide channel for the James River, James, Nansemond River, Nansemond and Elizabeth River (Virginia), Elizabeth rivers between Old Point Comfort and Sewell's ...

, Virginia, on November 15, where Wilkes wired news of the capture to Washington

Washington commonly refers to:

* Washington (state), United States

* Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States

** A metonym for the federal government of the United States

** Washington metropolitan area, the metropolitan area centered o ...

. He was then ordered to Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

where he delivered the captives to Fort Warren, a prison for captured Confederates.

American reaction (November 16 – December 18, 1861)

Most Northerners learned of the ''Trent'' capture on November 16 when the news hit afternoon newspapers. By Monday, November 18, the press seemed "universally engulfed in a massive wave of chauvinistic elation". Mason and Slidell, "the caged ambassadors", were denounced as "knaves", "cowards", "snobs", and "cold, cruel, and selfish".

Everyone was eager to present a legal justification for the capture. The British consul in Boston remarked that every other citizen was "walking around with a Law Book under his arm and proving the right of the S. Jacintho to stop H.M.'s

Most Northerners learned of the ''Trent'' capture on November 16 when the news hit afternoon newspapers. By Monday, November 18, the press seemed "universally engulfed in a massive wave of chauvinistic elation". Mason and Slidell, "the caged ambassadors", were denounced as "knaves", "cowards", "snobs", and "cold, cruel, and selfish".

Everyone was eager to present a legal justification for the capture. The British consul in Boston remarked that every other citizen was "walking around with a Law Book under his arm and proving the right of the S. Jacintho to stop H.M.'s mail boat

Mail boats or postal boats are a boat or ship used for the delivery of mail and sometimes transportation of goods, people and vehicles in communities where bodies of water commonly separate or separated settlements, towns or cities often where b ...

". Many newspapers likewise argued for the legality of Wilkes' actions, and numerous lawyers stepped forward to add their approval. Harvard law professor Theophilus Parsons

Theophilus Parsons (February 24, 1750October 30, 1813) was an American jurist.

Life

Born in Newbury, Massachusetts to a clergyman father, Parsons was one of the early students at the Dummer Academy (now The Governor's Academy) before matricu ...

wrote, "I am just as certain that Wilkes had a legal right to take Mason and Slidell from the ''Trent'', as I am that our government has a legal right to blockade the port of Charleston." Caleb Cushing

Caleb Cushing (January 17, 1800 – January 2, 1879) was an American Democratic politician and diplomat who served as a Congressman from Massachusetts and Attorney General under President Franklin Pierce. He was an eager proponent of territor ...

, a prominent Democrat

Democrat, Democrats, or Democratic may refer to:

Politics

*A proponent of democracy, or democratic government; a form of government involving rule by the people.

*A member of a Democratic Party:

**Democratic Party (United States) (D)

**Democratic ...

, and former Attorney General

In most common law jurisdictions, the attorney general or attorney-general (sometimes abbreviated AG or Atty.-Gen) is the main legal advisor to the government. The plural is attorneys general.

In some jurisdictions, attorneys general also have exec ...

(under Franklin Pierce

Franklin Pierce (November 23, 1804October 8, 1869) was the 14th president of the United States, serving from 1853 to 1857. He was a northern Democrat who believed that the abolitionist movement was a fundamental threat to the nation's unity ...

) concurred: "In my judgment, the act of Captain Wilkes was one which any and every self-respecting nation must and would have done by its own sovereign right and power, regardless of circumstances." Richard Henry Dana Jr.

Richard Henry Dana Jr. (August 1, 1815 – January 6, 1882) was an American lawyer and politician from Massachusetts, a descendant of a colonial family, who gained renown as the author of the classic American memoir ''Two Years Before the Mast''. ...

, considered an expert on maritime law, justified the detention because the envoys were engaged "solely na mission hostile to the United States", making them guilty of "treason within our municipal law". Edward Everett

Edward Everett (April 11, 1794 – January 15, 1865) was an American politician, Unitarian pastor, educator, diplomat, and orator from Massachusetts. Everett, as a Whig, served as U.S. representative, U.S. senator, the 15th governor of Mass ...

, a former minister to Great Britain and a former Secretary of State, also argued that "the detention was perfectly lawful ndtheir confinement in Fort Warren will be perfectly lawful."

A banquet was given to honor Wilkes at the Revere House

Revere may refer to:

Brands and companies

*Revere Ware, a U.S. cookware brand owned by World Kitchen

* Revere Camera Company, American designer of cameras and tape recorders

*Revere Copper Company

* ReVere, a car company recognised by the Classi ...

in Boston on November 26. Massachusetts

Massachusetts (Massachusett language, Massachusett: ''Muhsachuweesut assachusett writing systems, məhswatʃəwiːsət'' English: , ), officially the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, is the most populous U.S. state, state in the New England ...

governor John A. Andrew

John Albion Andrew (May 31, 1818 – October 30, 1867) was an American lawyer and politician from Massachusetts. He was elected in 1860 as the 25th Governor of Massachusetts, serving between 1861 and 1866, and led the state's contributions to ...

praised Wilkes for his "manly and heroic success" and spoke of the "exultation of the American heart" when Wilkes "fired his shot across the bows of the ship that bore the British Lion at its head". George T. Bigelow, the chief justice of Massachusetts, spoke admiringly of Wilkes: "In common with all loyal men of the North, I have been sighing, for the last six months, for someone who would be willing to say to himself, 'I will take the responsibility. On December 2, Congress passed unanimously a resolution thanking Wilkes "for his brave, adroit and patriotic conduct in the arrest and detention of the traitors, James M. Mason and John Slidell" and proposing that he receive a "gold medal with suitable emblems and devices, in testimony of the high sense entertained by Congress of his good conduct".Charles Francis Adams Jr., p. 548.

But as the matter was given closer study, people began to have doubts. Secretary of the Navy

The secretary of the Navy (or SECNAV) is a statutory officer () and the head (chief executive officer) of the Department of the Navy, a military department (component organization) within the United States Department of Defense.

By law, the se ...

Gideon Welles

Gideon Welles (July 1, 1802 – February 11, 1878), nicknamed "Father Neptune", was the United States Secretary of the Navy from 1861 to 1869, a cabinet post he was awarded after supporting Abraham Lincoln in the 1860 election. Although opposed ...

reflected the ambiguity that many felt when he wrote to Wilkes of "the emphatic approval" of the Navy Department for his actions while cautioning him that the failure to take the ''Trent'' to a prize court "must by no means be permitted to constitute a precedent hereafter for the treatment of any case of similar infraction of neutral obligations". On November 24, the ''New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid d ...

'' claimed to find no actual on point precedent. Thurlow Weed

Edward Thurlow Weed (November 15, 1797 – November 22, 1882) was a printer, New York newspaper publisher, and Whig and Republican politician. He was the principal political advisor to prominent New York politician William H. Seward and was ins ...

's ''Albany Evening Journal'' suggested that, if Wilkes had "exercised an unwarranted discretion, our government will properly disavow the proceedings and grant England 'every satisfaction' consistent with honor and justice". It did not take long for others to comment that the capture of Mason and Slidell very much resembled the search and impressment practices that the United States had always opposed since its founding and which had previously led to the War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States of America and its indigenous allies against the United Kingdom and its allies in British North America, with limited participation by Spain in Florida. It bega ...

with Britain. The idea of humans as contraband failed to strike a resonant chord with many.

Henry Adams

Henry Brooks Adams (February 16, 1838 – March 27, 1918) was an American historian and a member of the Adams political family, descended from two U.S. Presidents.

As a young Harvard graduate, he served as secretary to his father, Charles Fr ...

wrote to his brother on the impressment issue:

People also started to realize that the issue might be resolved less on legalities and more on the necessity of avoiding a serious conflict with Britain. Elder statesmen James Buchanan

James Buchanan Jr. ( ; April 23, 1791June 1, 1868) was an American lawyer, diplomat and politician who served as the 15th president of the United States from 1857 to 1861. He previously served as secretary of state from 1845 to 1849 and repr ...

, Thomas Ewing

Thomas Ewing Sr. (December 28, 1789October 26, 1871) was a National Republican and Whig politician from Ohio. He served in the U.S. Senate as well as serving as the secretary of the treasury and the first secretary of the interior. He is als ...

, Lewis Cass

Lewis Cass (October 9, 1782June 17, 1866) was an American military officer, politician, and statesman. He represented Michigan in the United States Senate and served in the Cabinets of two U.S. Presidents, Andrew Jackson and James Buchanan. He w ...

, and Robert J. Walker all publicly came out for the necessity of releasing them. By the third week of December much of the editorial opinion started to mirror these opinions and prepare the American citizens for the release of the prisoners. The opinion that Wilkes had operated without orders and had erred by, in effect, holding a prize court on the deck of the ''San Jacinto'' was being spread.

The United States was initially very reluctant to back down. Seward had lost the initial opportunity to immediately release the two envoys as an affirmation of a long-held U.S. interpretation of international law. He had written to Adams at the end of November that Wilkes had not acted under instructions, but would hold back any more information until it had received some response from Great Britain. He reiterated that recognition of the Confederacy would likely lead to war.

Lincoln was at first enthused about the capture and reluctant to let them go, but as reality set in he stated:

On December 4, Lincoln met with Alexander Galt

Sir Alexander Tilloch Galt, (September 6, 1817 – September 19, 1893) was a politician and a father of the Canadian Confederation.

Early life

Galt was born in Chelsea, England on September 6, 1817. He was the son of John Galt, a Scottish ...

, the future Canadian Minister of Finance. Lincoln told him that he had no desire for troubles with England or any unfriendly designs toward Canada. When Galt asked specifically about the ''Trent'' incident, Lincoln replied, "Oh, that'll be got along with." Galt forwarded his account of the meeting to Lyons who forwarded it to Russell. Galt wrote that, despite Lincoln's assurances, "I cannot, however, divest my mind of the impression that the policy of the American Govt is so subject to popular impulses, that no assurance can be or ought to be relied on under present circumstances." Lincoln's annual message to Congress did not touch directly on the ''Trent'' affair but, relying on estimates from Secretary of War

The secretary of war was a member of the U.S. president's Cabinet, beginning with George Washington's administration. A similar position, called either "Secretary at War" or "Secretary of War", had been appointed to serve the Congress of the ...

Simon Cameron

Simon Cameron (March 8, 1799June 26, 1889) was an American businessman and politician who represented Pennsylvania in the United States Senate and served as United States Secretary of War under President Abraham Lincoln at the start of the Americ ...

that the U.S. could field a 3,000,000 man army, stated that he could "show the world, that while engaged in quelling disturbances at home we are able to protect ourselves from abroad".

Finance also played a role: Treasury Secretary

The United States secretary of the treasury is the head of the United States Department of the Treasury, and is the chief financial officer of the federal government of the United States. The secretary of the treasury serves as the principal a ...

Salmon P. Chase

Salmon Portland Chase (January 13, 1808May 7, 1873) was an American politician and jurist who served as the sixth chief justice of the United States. He also served as the 23rd governor of Ohio, represented Ohio in the United States Senate, a ...

was concerned with any events that might affect American interests in Europe. Chase was aware of the intent of New York banks to suspend specie

Specie may refer to:

* Coins or other metal money in mass circulation

* Bullion coins

* Hard money (policy)

* Commodity money

Commodity money is money whose value comes from a commodity of which it is made. Commodity money consists of objects ...

payments, and he would later make a lengthy argument at the Christmas cabinet meeting in support of Seward. In his diary, Chase wrote that the release of Mason and Slidell "…was like gall and wormwood to me. But we cannot afford delays while the matter hangs in uncertainty, the public mind will remain disquieted, our commerce will suffer serious harm, our action against the rebels must be greatly hindered." Warren notes, "Although the ''Trent'' affair did not cause the national banking crisis, it contributed to the virtual collapse of a haphazard system of war finance, which depended on public confidence."

On December 15 the first news on British reaction reached the United States. Britain first learned of the events on November 27. Lincoln was with Senator

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

Orville Browning

Orville Hickman Browning (February 10, 1806 – August 10, 1881) was an attorney in Illinois and a politician who was active in the Whig and Republican Parties. He is notable for his service as a U.S. Senator and the United States Secret ...

when Seward brought in the first newspaper dispatches, which indicated Palmerston was demanding a release of the prisoners and an apology. Browning thought the threat of war by Britain was "foolish" but said, "We will fight her to the death." That night at a diplomatic reception Seward was overheard by William H. Russell saying, "We will wrap the whole world in flames." The mood in Congress had also changed. When they debated the issue on December 16 and 17, Clement L. Vallandigham

Clement Laird Vallandigham ( ; July 29, 1820 – June 17, 1871) was an American politician and leader of the Copperhead faction of anti-war Democrats during the American Civil War. He served two terms for Ohio's 3rd congressional district in t ...

, a peace Democrat, proposed a resolution stating that the U.S. maintain the seizure as a matter of honor. The motion was opposed and referred to a committee by the vote of 109 to 16. The official response of the government still awaited the formal British response which did not arrive in America until December 18.

British reaction (November 27 – December 31, 1861)

When arrived inSouthampton

Southampton () is a port city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. It is located approximately south-west of London and west of Portsmouth. The city forms part of the South Hampshire built-up area, which also covers Po ...

and Commander Marchand learned from ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper ''The Sunday Times'' (fou ...

'' that his targets had arrived in Cuba, he reacted to the news by boasting that he would capture the two envoys within sight of the British shore if necessary, even if they were on a British ship. As a result of the concerns raised by Marchand's statements, the British Foreign Office requested a judicial opinion from the three Law Officers of the Crown (the queen's advocate, the attorney general, and the solicitor general) on the legality of capturing the men from a British ship. The written reply dated November 12 declared:

On November 12, Palmerston advised Adams in person that the British nonetheless would take offense if the envoys were removed from a British ship. Palmerston emphasized that seizing the Confederates would be "highly inexpedient in every way Palmerston could view it" and a few more Confederates in Britain would not "produce any change in policy already adopted". Palmerston questioned the presence of ''Adger'' in British waters, and Adams assured Palmerston that he had read Marchand's orders (Marchand had visited Adams while in Great Britain) which limited him to seizing Mason and Slidell from a Confederate ship.

The news of the actual capture of Mason and Slidell did not arrive in London until November 27. Much of the public and many of the newspapers immediately perceived it as an outrageous insult to British honor, and a flagrant violation of maritime law

Admiralty law or maritime law is a body of law that governs nautical issues and private maritime disputes. Admiralty law consists of both domestic law on maritime activities, and private international law governing the relationships between priva ...

. The ''London Chronicle

The ''London Chronicle'' was an early family newspaper of Georgian London. It was a thrice-a-week evening paper, introduced in 1756, and contained world and national news, and coverage of artistic, literary, and theatrical events in the capital ...

''s response was typical:

The London ''Standard'' saw the capture as "but one of a series of premeditated blows aimed at this country … to involve it in a war with the Northern States". A letter from an American visitor written to Seward declared, "The people are frantic with rage, and were the country polled I fear 999 men out of 1,000 would declare for immediate war." A member of Parliament stated that unless America set matters right the British flag should "be torn into shreds and sent to Washington for use of the Presidential water-closets". The seizure provoked one anti-Union meeting, held in Liverpool (later a hub of Confederate sympathy) and chaired by the future Confederate spokesman James Spence.Campbell, p. 67.

''The Times'' published its first report from the United States on December 4, and its correspondent, W. H. Russell, wrote of American reactions, "There is so much violence of spirit among the lower orders of the people and they are … so saturated with pride and vanity that any honorable concession … would prove fatal to its authors." ''Times'' editor John T. Delane took a moderate stance and warned the people not to "regard the act in the worst light" and to question whether it made sense that the United States, despite British misgivings about Seward that went back to the earliest days of the Lincoln administration, would "force a quarrel upon the Powers of Europe". This restrained stance was common in Britain: "the press, as a whole, preached calm and praised it too, noting the general moderation of public temper it perceived".

The government got its first solid information on the ''Trent'' from Commander Williams who went directly to London after he arrived in England. He spent several hours with the Admiralty

Admiralty most often refers to:

*Admiralty, Hong Kong

*Admiralty (United Kingdom), military department in command of the Royal Navy from 1707 to 1964

*The rank of admiral

*Admiralty law

Admiralty can also refer to:

Buildings

* Admiralty, Traf ...

and the Prime Minister. Initial reaction among political leaders was firmly opposed to the American actions. Lord Clarendon

Earl of Clarendon is a title that has been created twice in British history, in 1661 and 1776.

The family seat is Holywell House, near Swanmore, Hampshire.

First creation of the title