tree swallow on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The tree swallow (''Tachycineta bicolor'') is a

The tree swallow's song consists of three parts: the chirp, the whine, and the gurgle. These sections may be repeated or omitted, and all can stand alone. The first, as the chirp call (sometimes divided into the contact call and solicitation call), is made by the female during copulation and in both sexes to stimulate the nestlings to beg or (in some populations) when their mate leaves or enters the nest cavity. The whine, generally consisting of a downward shift in frequency followed by an upward shift, may be given alone as the anxiety call, occasionally made in response to certain predators. The gurgle, as when it appears at the end of the song, is usually uttered twice. It is likely involved in pair bonding. The chatter call is used to advertise nest sites (the reason it is also known as the "nest-site advertising call") and is also given to intruding conspecifics. A short high-pitched submission call is sometimes uttered after an aggressive encounter with another tree swallow. While being physically restrained or in pain, a distress call may be given. The male often utters a ticking (or rasping) aggression call during copulation, and both sexes use it at the end of mobbing dives. The alarm call is given in reaction to predators and other intruders, and can serve to induce older nestlings to crouch and stop begging when a predator is near.

Communication between parents and offspring can be disrupted by human-generated noise. A 2014 study, for example, found that broods for whom white noise was played were less likely to crouch or stop begging in response to alarm calls. Parents did not alter their calls to compensate, likely increasing predation risk. Noise can also disrupt whether parents respond to begging, but this may be balanced out by the louder calls nestlings give when exposed to it. Increased begging effort, however, may be ineffective or costly for louder levels of noise.

The tree swallow's song consists of three parts: the chirp, the whine, and the gurgle. These sections may be repeated or omitted, and all can stand alone. The first, as the chirp call (sometimes divided into the contact call and solicitation call), is made by the female during copulation and in both sexes to stimulate the nestlings to beg or (in some populations) when their mate leaves or enters the nest cavity. The whine, generally consisting of a downward shift in frequency followed by an upward shift, may be given alone as the anxiety call, occasionally made in response to certain predators. The gurgle, as when it appears at the end of the song, is usually uttered twice. It is likely involved in pair bonding. The chatter call is used to advertise nest sites (the reason it is also known as the "nest-site advertising call") and is also given to intruding conspecifics. A short high-pitched submission call is sometimes uttered after an aggressive encounter with another tree swallow. While being physically restrained or in pain, a distress call may be given. The male often utters a ticking (or rasping) aggression call during copulation, and both sexes use it at the end of mobbing dives. The alarm call is given in reaction to predators and other intruders, and can serve to induce older nestlings to crouch and stop begging when a predator is near.

Communication between parents and offspring can be disrupted by human-generated noise. A 2014 study, for example, found that broods for whom white noise was played were less likely to crouch or stop begging in response to alarm calls. Parents did not alter their calls to compensate, likely increasing predation risk. Noise can also disrupt whether parents respond to begging, but this may be balanced out by the louder calls nestlings give when exposed to it. Increased begging effort, however, may be ineffective or costly for louder levels of noise.

During courtship, a male tree swallow attacks an unknown female. This can be stimulated through wing-fluttering flight by the female, which may be an invitation to court. The male may then take a vertical posture, with a raised and slightly spread tail and wings flicked and slightly drooped. This prompts the female to try to land on the male's back, but he flies to prevent this; this is repeated. After courting the female, the male flies to his chosen nest site, which the female inspects. During copulation, the male hovers over the female, and then mounts her, giving ticking calls. He then makes with the female while holding her neck feathers in his bill and standing on her slightly outstretched wings. Copulation occurs multiple times.

Eggs are laid from early May to mid-June (although this is happening earlier due to

During courtship, a male tree swallow attacks an unknown female. This can be stimulated through wing-fluttering flight by the female, which may be an invitation to court. The male may then take a vertical posture, with a raised and slightly spread tail and wings flicked and slightly drooped. This prompts the female to try to land on the male's back, but he flies to prevent this; this is repeated. After courting the female, the male flies to his chosen nest site, which the female inspects. During copulation, the male hovers over the female, and then mounts her, giving ticking calls. He then makes with the female while holding her neck feathers in his bill and standing on her slightly outstretched wings. Copulation occurs multiple times.

Eggs are laid from early May to mid-June (although this is happening earlier due to  The tree swallow has high rates of extra-pair paternity, 38% to 69% of nestlings being a product of extra-pair paternity, and 50% to 87% of broods containing at least one nestling that was the result of an extra-pair copulation. One factor that might contribute to this is that females have control over copulation, making paternity guards ineffective. This may be mitigated by more frequent copulations just before egg laying, according to a 2009 study which found that within-pair copulation attempts peaked three to one days before the first egg was laid and that more successful attempts during this period increased the share of within-pair young males had. This latter finding contradicts those of a 1993 and a 1994 study. Extra-pair paternity does not change the level of parental care the male contributes in the tree swallow. A significant number of extra-pair fathers may be floaters (those present at breeding grounds that presumably do not breed). A 2001 study found that out of 35 extra-pair nestlings, 25 were sired by local residents, three by residents of nearby sites, and seven by male floaters. In the tree swallow, floating thus helps males in good condition produce more chicks, while allowing males in bad condition to be successful by investing in parental care. There is also a significant population of female floaters; a 1985 study estimated that around 23% to 27% of females were floaters, of which about 47% to 79% were subadults.

Why females engage in extra-pair copulation and how they choose extra-pair mates is controversial. One theory, called the genetic compatibility hypothesis, states that increased offspring fitness results from increased

The tree swallow has high rates of extra-pair paternity, 38% to 69% of nestlings being a product of extra-pair paternity, and 50% to 87% of broods containing at least one nestling that was the result of an extra-pair copulation. One factor that might contribute to this is that females have control over copulation, making paternity guards ineffective. This may be mitigated by more frequent copulations just before egg laying, according to a 2009 study which found that within-pair copulation attempts peaked three to one days before the first egg was laid and that more successful attempts during this period increased the share of within-pair young males had. This latter finding contradicts those of a 1993 and a 1994 study. Extra-pair paternity does not change the level of parental care the male contributes in the tree swallow. A significant number of extra-pair fathers may be floaters (those present at breeding grounds that presumably do not breed). A 2001 study found that out of 35 extra-pair nestlings, 25 were sired by local residents, three by residents of nearby sites, and seven by male floaters. In the tree swallow, floating thus helps males in good condition produce more chicks, while allowing males in bad condition to be successful by investing in parental care. There is also a significant population of female floaters; a 1985 study estimated that around 23% to 27% of females were floaters, of which about 47% to 79% were subadults.

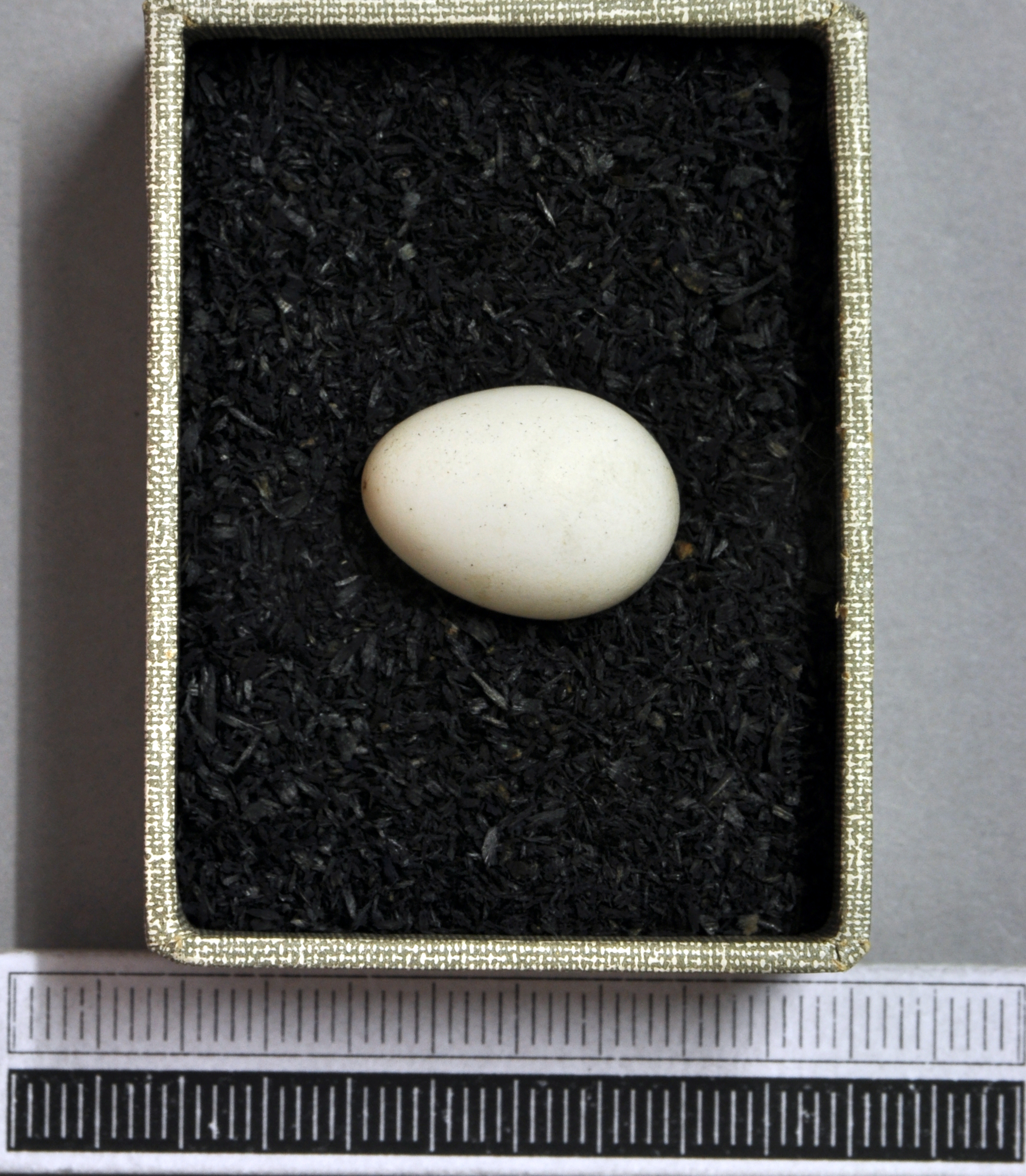

Why females engage in extra-pair copulation and how they choose extra-pair mates is controversial. One theory, called the genetic compatibility hypothesis, states that increased offspring fitness results from increased  The tree swallow lays a clutch of two to eight, although usually four to seven, pure white, and translucent at laying, eggs that measure about . These eggs are incubated by the female, usually after the second-to-last egg is laid, for 11 to 20 days, although most hatch after 14 to 15 days. About 88% of nests produce at least one nestling, but this can be lowered by poor weather and a younger breeding female. The eggs generally hatch in the order they were laid. They also hatch slightly asynchronously, with an average of 28 hours between when the first and final nestling emerges. This can result in a weight hierarchy where earlier-hatched chicks weigh more (especially early in the nestling period) than those hatched later, allowing the female to prioritize which chick to give food to during food shortages. This likely has its greatest effect early in the nestling period, as by 12 days after hatching, there are generally no significant weight differences. Infanticide of the chicks and eggs sometimes occurs when a male is replaced by another male. Infanticide usually does not occur when the clutch is not complete, as replacement males then have a chance to fertilize at least one egg. When the male arrives during incubation, it sometimes commits infanticide, but other times adopts the eggs, as there is a chance that some eggs were sired from the replacement male. If the replacement male arrives after the chicks hatch, infanticide is usually committed, though the female will sometimes prevent this.

Nests produced by females of better condition often have sex ratios skewed towards high quality males. A 2000 study hypothesized this to be because males have more variable reproductive success, and therefore that a high quality male produces more offspring than a female of similar quality.

The growth and survival of nestling tree swallows is influenced by their environment. In both younger and older nestlings (those between two and four days old and between nine and eleven days, respectively) growth is positively influenced by a higher maximum temperature, particularly in the former. A later hatching date negatively impacts growth, especially for younger nestlings. Older chicks grow somewhat faster when insects are abundant. Growth in younger nestlings increases with age, while in old nestlings, it decreases as they get older. Young tree swallows are able to thermoregulate at least 75% as effectively as the adult at an average age of 9.5 days when out of the nest, and from four to eight days old when in the nest (depending on the size of the brood). The nestlings fledge after about 18 to 22 days, with about 80% fledging success. Like hatching success, this is negatively affected by unfavourable weather and a younger female. Chicks may be preyed on by snakes and raccoons. This predation can be exacerbated by begging calls.

The tree swallow lays a clutch of two to eight, although usually four to seven, pure white, and translucent at laying, eggs that measure about . These eggs are incubated by the female, usually after the second-to-last egg is laid, for 11 to 20 days, although most hatch after 14 to 15 days. About 88% of nests produce at least one nestling, but this can be lowered by poor weather and a younger breeding female. The eggs generally hatch in the order they were laid. They also hatch slightly asynchronously, with an average of 28 hours between when the first and final nestling emerges. This can result in a weight hierarchy where earlier-hatched chicks weigh more (especially early in the nestling period) than those hatched later, allowing the female to prioritize which chick to give food to during food shortages. This likely has its greatest effect early in the nestling period, as by 12 days after hatching, there are generally no significant weight differences. Infanticide of the chicks and eggs sometimes occurs when a male is replaced by another male. Infanticide usually does not occur when the clutch is not complete, as replacement males then have a chance to fertilize at least one egg. When the male arrives during incubation, it sometimes commits infanticide, but other times adopts the eggs, as there is a chance that some eggs were sired from the replacement male. If the replacement male arrives after the chicks hatch, infanticide is usually committed, though the female will sometimes prevent this.

Nests produced by females of better condition often have sex ratios skewed towards high quality males. A 2000 study hypothesized this to be because males have more variable reproductive success, and therefore that a high quality male produces more offspring than a female of similar quality.

The growth and survival of nestling tree swallows is influenced by their environment. In both younger and older nestlings (those between two and four days old and between nine and eleven days, respectively) growth is positively influenced by a higher maximum temperature, particularly in the former. A later hatching date negatively impacts growth, especially for younger nestlings. Older chicks grow somewhat faster when insects are abundant. Growth in younger nestlings increases with age, while in old nestlings, it decreases as they get older. Young tree swallows are able to thermoregulate at least 75% as effectively as the adult at an average age of 9.5 days when out of the nest, and from four to eight days old when in the nest (depending on the size of the brood). The nestlings fledge after about 18 to 22 days, with about 80% fledging success. Like hatching success, this is negatively affected by unfavourable weather and a younger female. Chicks may be preyed on by snakes and raccoons. This predation can be exacerbated by begging calls.

migratory bird

Bird migration is a seasonal movement of birds between breeding and wintering grounds that occurs twice a year. It is typically from north to south or from south to north. Migration is inherently risky, due to predation and mortality.

Th ...

of the family Hirundinidae

The swallows, martins, and saw-wings, or Hirundinidae are a family of passerine songbirds found around the world on all continents, including occasionally in Antarctica. Highly adapted to aerial feeding, they have a distinctive appearance. The t ...

. Found in the Americas

The Americas, sometimes collectively called America, are a landmass comprising the totality of North America and South America.''Webster's New World College Dictionary'', 2010 by Wiley Publishing, Inc., Cleveland, Ohio. When viewed as a sing ...

, the tree swallow was first described in 1807 by French ornithologist

Ornithology, from Ancient Greek ὄρνις (''órnis''), meaning "bird", and -logy from λόγος (''lógos''), meaning "study", is a branch of zoology dedicated to the study of birds. Several aspects of ornithology differ from related discip ...

Louis Vieillot as ''Hirundo bicolor''. It has since been moved to its current genus, '' Tachycineta'', within which its phylogenetic placement is debated. The tree swallow has glossy blue-green , with the exception of the blackish wings and tail, and white . The bill is black, the eyes dark brown, and the legs and feet pale brown. The female is generally duller than the male, and the first-year female has mostly brown upperparts, with some blue feathers. Juveniles have brown upperparts, and gray-brown-washed breasts. The tree swallow breeds in the US and Canada. It winters along southern US coasts south, along the Gulf Coast, to Panama and the northwestern coast of South America, and in the West Indies

The West Indies is an island subregion of the Americas, surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea, which comprises 13 independent island country, island countries and 19 dependent territory, dependencies in thr ...

.

The tree swallow nests either in isolated pairs or loose groups, in both natural and artificial cavities. Breeding can start as soon as early May, although this date is occurring earlier because of climate change

Present-day climate change includes both global warming—the ongoing increase in Global surface temperature, global average temperature—and its wider effects on Earth's climate system. Climate variability and change, Climate change in ...

, and it can end as late as July. This bird is generally socially monogamous (although about 8% of males are polygynous

Polygyny () is a form of polygamy entailing the marriage of a man to several women. The term polygyny is from Neoclassical Greek πολυγυνία (); .

Incidence

Polygyny is more widespread in Africa than in any other continent. Some scholar ...

), with high levels of extra-pair paternity. This can benefit the male, but since the female controls copulation, the lack of resolution on how this behavior benefits females makes the high level of extra-pair paternity puzzling. The female incubates the clutch

A clutch is a mechanical device that allows an output shaft to be disconnected from a rotating input shaft. The clutch's input shaft is typically attached to a motor, while the clutch's output shaft is connected to the mechanism that does th ...

of two to eight (but usually four to seven) pure white eggs for around 14 to 15 days. The chicks hatch slightly asynchronously, allowing the female to prioritize which chicks to feed in times of food shortage. They generally fledge about 18 to 22 days after hatching. The tree swallow is sometimes considered a model organism

A model organism is a non-human species that is extensively studied to understand particular biological phenomena, with the expectation that discoveries made in the model organism will provide insight into the workings of other organisms. Mo ...

, due to the large amount of research done on it.

An aerial , the tree swallow forages both alone and in groups, eating mostly insect

Insects (from Latin ') are Hexapoda, hexapod invertebrates of the class (biology), class Insecta. They are the largest group within the arthropod phylum. Insects have a chitinous exoskeleton, a three-part body (Insect morphology#Head, head, ...

s, in addition to mollusk

Mollusca is a phylum of protostomic invertebrate animals, whose members are known as molluscs or mollusks (). Around 76,000 extant species of molluscs are recognized, making it the second-largest animal phylum after Arthropoda. The ...

s, spider

Spiders (order (biology), order Araneae) are air-breathing arthropods that have eight limbs, chelicerae with fangs generally able to inject venom, and spinnerets that extrude spider silk, silk. They are the largest order of arachnids and ran ...

s, and fruit. The nestlings, like the adult, primarily eat insects, fed to it by both sexes. This swallow

The swallows, martins, and saw-wings, or Hirundinidae are a family of passerine songbirds found around the world on all continents, including occasionally in Antarctica. Highly adapted to aerial feeding, they have a distinctive appearance. The ...

is vulnerable to parasites, but, when on nestlings, these do little damage. The effect of disease can become stronger as a tree swallow gets older, as some parts of the immune system decline with age. Acquired T cell

T cells (also known as T lymphocytes) are an important part of the immune system and play a central role in the adaptive immune response. T cells can be distinguished from other lymphocytes by the presence of a T-cell receptor (TCR) on their cell ...

-mediated immunity, for example, decreases with age, whereas both innate and acquired humoral immunity

Humoral immunity is the aspect of immunity (medical), immunity that is mediated by macromolecules – including secreted antibodies, complement proteins, and certain antimicrobial peptides – located in extracellular fluids. Humoral immunity is ...

do not. Because of its large range and stable population, the tree swallow is considered to be least concern

A least-concern species is a species that has been evaluated and categorized by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) as not being a focus of wildlife conservation because the specific species is still plentiful in the wil ...

by the International Union for Conservation of Nature

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) is an international organization working in the field of nature conservation and sustainable use of natural resources. Founded in 1948, IUCN has become the global authority on the stat ...

. In the US, it is protected by the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918

The Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918 (MBTA), codified at (although §709 is omitted), is a United States federal law, first enacted in 1918 to implement the convention for the protection of migratory birds between the United States and Canada. ...

, and in Canada by the Migratory Birds Convention Act. This swallow is negatively affected by human activities, such as the clearing of forests; acidified lakes can force a breeding tree swallow to go long distances to find calcium-rich food items to feed to its chicks.

Taxonomy and etymology

The tree swallow was described as ''Hirundo bicolor'' byLouis Pierre Vieillot

Louis Pierre Vieillot (10 May 1748, Yvetot – 24 August 1830, Sotteville-lès-Rouen) was a French ornithologist.

Vieillot is the author of the first scientific descriptions and Linnaean names of a number of birds, including species he collected ...

in his ''Histoire naturelle des oiseaux de l'Amérique Septentrionale'', published in 1807. It was then placed in its current genus '' Tachycineta'' when Jean Cabanis

Jean Louis Cabanis (8 March 1816 – 20 February 1906) was a German ornithologist. He worked at the bird collections of the Natural History Museum in Berlin becoming its first curator of birds in 1850. He founded the ''Journal für Ornithologie ...

established it in 1850. In 1878, Elliott Coues

Elliott Ladd Coues (; September 9, 1842 – December 25, 1899) was an American army surgeon, historian, ornithologist, and author. He led surveys of the Arizona Territory, and later as secretary of the United States Geological and Geographi ...

suggested that the tree swallow, at the very least, be put in its own subgenus

In biology, a subgenus ( subgenera) is a taxonomic rank directly below genus.

In the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature, a subgeneric name can be used independently or included in a species name, in parentheses, placed between the ge ...

, ''Iridoprocne'', on the basis of its plumage, along with the white-winged swallow, Chilean swallow, white-rumped swallow, and mangrove swallow. By 1882, he had upgraded this to a full genus. Some authors continued to use this classification, with the addition of Tumbes swallow; however, genetic evidence supports the existence of a single genus, ''Tachycineta''. The tree swallow is also called the white-bellied swallow for its white underparts.

The generally accepted genus name is from Ancient Greek

Ancient Greek (, ; ) includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the classical antiquity, ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Greek ...

''takhykinetos'', "moving quickly", and the specific ''bicolor'' is Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

and means "two-coloured". The other genus name, ''Iridoprocne'', comes from the Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

''iris'', meaning rainbow, and Procne

Procne (; , ''Próknē'' ) or Progne is a minor figure in Greek mythology. She was an Athens, Athenian princess as the elder daughter of a king of Athens named Pandion I, Pandion. Procne was married to the king of Thrace, Tereus, who instead lu ...

, a figure who supposedly turned into a swallow.

How exactly the tree swallow is related to other members of ''Tachycineta'' is unresolved. In studies based on mitochondrial DNA

Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA and mDNA) is the DNA located in the mitochondrion, mitochondria organelles in a eukaryotic cell that converts chemical energy from food into adenosine triphosphate (ATP). Mitochondrial DNA is a small portion of the D ...

, it was placed basal (meaning it was the first offshoot in the species tree) within the North American-Caribbean clade

In biology, a clade (), also known as a Monophyly, monophyletic group or natural group, is a group of organisms that is composed of a common ancestor and all of its descendants. Clades are the fundamental unit of cladistics, a modern approach t ...

consisting of the violet-green swallow, golden swallow, and Bahama swallow. Although mitochondrial DNA is advocated as a better indicator of evolutionary changes because it evolves quickly, analyses based on it can suffer because it is only inherited from the mother, making it worse than nuclear DNA

Nuclear DNA (nDNA), or nuclear deoxyribonucleic acid, is the DNA contained within each cell nucleus of a eukaryotic organism. It encodes for the majority of the genome in eukaryotes, with mitochondrial DNA and plastid DNA coding for the rest. ...

from multiple loci at representing the phylogeny of a whole group. A study based on such nuclear DNA placed the tree swallow in the most basal position within ''Tachycineta'' as a whole (as a sister group

In phylogenetics, a sister group or sister taxon, also called an adelphotaxon, comprises the closest relative(s) of another given unit in an evolutionary tree.

Definition

The expression is most easily illustrated by a cladogram:

Taxon A and ...

to the rest of the genus).

Description

The tree swallow has a length between about and a weight of approximately . Wingspan ranges from . The male has mostly glossy blue-green , the wings and tail being blackish. The and the cheek patch are white, although the coverts are gray-brown. The bill is black, the eyes dark brown, and the legs and feet pale brown. The female is duller in color than the male, and sometimes has a brown forehead. The second-year female also has brown upperparts, with a variable number of blue feathers; some third-year females also retain a portion of this subadult plumage. According to a 1987 study, this likely allows a younger female to explore nest sites, as the resident male is usually less aggressive to a subadult female. A 2013 study found that the resident female was less aggressive towards second-year female models when they were presented separately from older models. Why the female eventually replaces its subadult plumage is unknown; it may allow males to assess female quality, as pairs mate assortatively based on plumage brightness. The juvenile tree swallow can be distinguished by its brown upperparts and gray-brown-washed breast.Voice

The tree swallow's song consists of three parts: the chirp, the whine, and the gurgle. These sections may be repeated or omitted, and all can stand alone. The first, as the chirp call (sometimes divided into the contact call and solicitation call), is made by the female during copulation and in both sexes to stimulate the nestlings to beg or (in some populations) when their mate leaves or enters the nest cavity. The whine, generally consisting of a downward shift in frequency followed by an upward shift, may be given alone as the anxiety call, occasionally made in response to certain predators. The gurgle, as when it appears at the end of the song, is usually uttered twice. It is likely involved in pair bonding. The chatter call is used to advertise nest sites (the reason it is also known as the "nest-site advertising call") and is also given to intruding conspecifics. A short high-pitched submission call is sometimes uttered after an aggressive encounter with another tree swallow. While being physically restrained or in pain, a distress call may be given. The male often utters a ticking (or rasping) aggression call during copulation, and both sexes use it at the end of mobbing dives. The alarm call is given in reaction to predators and other intruders, and can serve to induce older nestlings to crouch and stop begging when a predator is near.

Communication between parents and offspring can be disrupted by human-generated noise. A 2014 study, for example, found that broods for whom white noise was played were less likely to crouch or stop begging in response to alarm calls. Parents did not alter their calls to compensate, likely increasing predation risk. Noise can also disrupt whether parents respond to begging, but this may be balanced out by the louder calls nestlings give when exposed to it. Increased begging effort, however, may be ineffective or costly for louder levels of noise.

The tree swallow's song consists of three parts: the chirp, the whine, and the gurgle. These sections may be repeated or omitted, and all can stand alone. The first, as the chirp call (sometimes divided into the contact call and solicitation call), is made by the female during copulation and in both sexes to stimulate the nestlings to beg or (in some populations) when their mate leaves or enters the nest cavity. The whine, generally consisting of a downward shift in frequency followed by an upward shift, may be given alone as the anxiety call, occasionally made in response to certain predators. The gurgle, as when it appears at the end of the song, is usually uttered twice. It is likely involved in pair bonding. The chatter call is used to advertise nest sites (the reason it is also known as the "nest-site advertising call") and is also given to intruding conspecifics. A short high-pitched submission call is sometimes uttered after an aggressive encounter with another tree swallow. While being physically restrained or in pain, a distress call may be given. The male often utters a ticking (or rasping) aggression call during copulation, and both sexes use it at the end of mobbing dives. The alarm call is given in reaction to predators and other intruders, and can serve to induce older nestlings to crouch and stop begging when a predator is near.

Communication between parents and offspring can be disrupted by human-generated noise. A 2014 study, for example, found that broods for whom white noise was played were less likely to crouch or stop begging in response to alarm calls. Parents did not alter their calls to compensate, likely increasing predation risk. Noise can also disrupt whether parents respond to begging, but this may be balanced out by the louder calls nestlings give when exposed to it. Increased begging effort, however, may be ineffective or costly for louder levels of noise.

Distribution and habitat

The tree swallow breeds in North America. Its range extends to north-central Alaska and up to thetree line

The tree line is the edge of a habitat at which trees are capable of growing and beyond which they are not. It is found at high elevations and high latitudes. Beyond the tree line, trees cannot tolerate the environmental conditions (usually low ...

in Canada. It is found as far south as Tennessee in the eastern part of its range, California and New Mexico in the west, and Kansas in the center. It occasionally breeds further south in the US, and vagrants are sometimes found in the Arctic Circle

The Arctic Circle is one of the two polar circles, and the northernmost of the five major circle of latitude, circles of latitude as shown on maps of Earth at about 66° 34' N. Its southern counterpart is the Antarctic Circle.

The Arctic Circl ...

, the northern Pacific

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean, or, depending on the definition, to Antarctica in the south, and is bounded by the cont ...

, Greenland

Greenland is an autonomous territory in the Danish Realm, Kingdom of Denmark. It is by far the largest geographically of three constituent parts of the kingdom; the other two are metropolitan Denmark and the Faroe Islands. Citizens of Greenlan ...

, and Europe. The wintering range is from California and southwestern Arizona in the west and southeastern Virginia in the east south along the Gulf Coast to the West Indies

The West Indies is an island subregion of the Americas, surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea, which comprises 13 independent island country, island countries and 19 dependent territory, dependencies in thr ...

, Panama

Panama, officially the Republic of Panama, is a country in Latin America at the southern end of Central America, bordering South America. It is bordered by Costa Rica to the west, Colombia to the southeast, the Caribbean Sea to the north, and ...

, and the northwestern South American coast. While migrating, this swallow often uses stop-over sites, spending an average of 57 days at these areas during autumn. To get to its wintering range, it often uses one of three flyways: the Western flyway, west of the Rocky Mountains

The Rocky Mountains, also known as the Rockies, are a major mountain range and the largest mountain system in North America. The Rocky Mountains stretch in great-circle distance, straight-line distance from the northernmost part of Western Can ...

; the Central flyway, between the Rocky Mountains and the Great Lakes

The Great Lakes, also called the Great Lakes of North America, are a series of large interconnected freshwater lakes spanning the Canada–United States border. The five lakes are Lake Superior, Superior, Lake Michigan, Michigan, Lake Huron, H ...

, stretching south into Eastern Mexico; and the Eastern flyway, from the Great Lakes east. When a swallow returns to nest, it usually does not change breeding sites.

The breeding habitat of this bird is primarily in open and wooded areas, especially those near water. It roosts every night during the non-breeding season, preferring to rest in cane

Cane or caning may refer to:

*Walking stick, or walking cane, a device used primarily to aid walking

* Assistive cane, a walking stick used as a mobility aid for better balance

* White cane, a mobility or safety device used by blind or visually i ...

or reed bed

A reedbed or reed bed is a natural habitat found in floodplains, waterlogged depressions and

estuaries. Reedbeds are part of a succession from young reeds colonising open water or wet ground through a gradation of increasingly dry ground. As ...

s over water, but it is also found over land and on trees and wires. Roosting sites are generally apart.

Behaviour

Because of the large amount of research on the tree swallow and how it willingly breeds in nest boxes, biologist Jason Jones recommended that it be considered amodel organism

A model organism is a non-human species that is extensively studied to understand particular biological phenomena, with the expectation that discoveries made in the model organism will provide insight into the workings of other organisms. Mo ...

. Although it is aggressive during the breeding season, this swallow is sociable outside of it, forming flocks sometimes numbering thousands of birds.

Breeding

The tree swallow nests in structures with pre-existing holes, both natural and artificial. These were once found only in forested regions, but the building of nest boxes has allowed this bird to expand into open habitats. This swallow usually nests in the area it bred the year before; only about 14% of females and 4% of males disperse to breed at a new site per year. Most do not go far, usually breeding at sites less than away from their original grounds. Dispersal is influenced by breeding success; of the adult females that fail to fledge a chick, about 28% disperse, compared to 5% of successful breeders. Natal dispersal (when a bird does not return to the site it was born at to breed) is common in the tree swallow and occurs more frequently than breeding dispersal. It nests both in loose groups and isolated pairs. When nesting in loose groups, nests are usually spaced at least apart, and those that are closer in distance are usually further apart in terms of laying date. In natural cavities, the tree swallow nests about apart from its neighbor. The nest hole in these situations is, on average, above ground level, although about 45% of them are less than above the ground. Higher cavities are likely favored because they reduce predation, while lower nest holes may be chosen to avoid competition. Entrance widths are often between , whereas entrance heights are more variable: a 1989 study found openings ranging from . Cavity volume is generally below . After finding a suitable place to nest, the male perches near it and calls frequently. A lack of sites can cause fights between birds, sometimes resulting in deaths. This swallow usually defends an area around the nest with a radius of about , as well as extra nests inside of that , by blocking the entrance to the nest and chasing intruders. The nest cup itself is made from grass, moss, pine needles, and aquatic plants collected mostly by the female, and is lined with feathers gathered primarily by the male in fights. The feathers may function to insulate the nest, decreasing incubation time and likely preventinghypothermia

Hypothermia is defined as a body core temperature below in humans. Symptoms depend on the temperature. In mild hypothermia, there is shivering and mental confusion. In moderate hypothermia, shivering stops and confusion increases. In severe ...

in chicks. In addition to faster growth for chicks, eggs cool slower in nests with feathers than those without. However, a study published in 2018 did not find a significant correlation between the number of feathers in nests that were artificially warmed versus those that were not. Additionally, it found that nests in St. Denis, Saskatchewan used significantly less feathers than those in Annapolis Valley

The Annapolis Valley is a valley and region in the province of Nova Scotia, Canada. It is located in the western part of the Nova Scotia peninsula, formed by a Trough (geology), trough between two parallel mountain ranges along the shore of the B ...

, despite the former being further north. However, temperatures in Nova Scotia (where Annapolis Valley is) are generally lower than those in Saskatchewan, possibly explaining the unexpected result.

During courtship, a male tree swallow attacks an unknown female. This can be stimulated through wing-fluttering flight by the female, which may be an invitation to court. The male may then take a vertical posture, with a raised and slightly spread tail and wings flicked and slightly drooped. This prompts the female to try to land on the male's back, but he flies to prevent this; this is repeated. After courting the female, the male flies to his chosen nest site, which the female inspects. During copulation, the male hovers over the female, and then mounts her, giving ticking calls. He then makes with the female while holding her neck feathers in his bill and standing on her slightly outstretched wings. Copulation occurs multiple times.

Eggs are laid from early May to mid-June (although this is happening earlier due to

During courtship, a male tree swallow attacks an unknown female. This can be stimulated through wing-fluttering flight by the female, which may be an invitation to court. The male may then take a vertical posture, with a raised and slightly spread tail and wings flicked and slightly drooped. This prompts the female to try to land on the male's back, but he flies to prevent this; this is repeated. After courting the female, the male flies to his chosen nest site, which the female inspects. During copulation, the male hovers over the female, and then mounts her, giving ticking calls. He then makes with the female while holding her neck feathers in his bill and standing on her slightly outstretched wings. Copulation occurs multiple times.

Eggs are laid from early May to mid-June (although this is happening earlier due to climate change

Present-day climate change includes both global warming—the ongoing increase in Global surface temperature, global average temperature—and its wider effects on Earth's climate system. Climate variability and change, Climate change in ...

) and chicks fledge between mid-June and July. Latitude is positively correlated with laying date, while female age and wing length (longer wings allow more efficient foraging) are negatively correlated. The tree swallow is likely an income breeder, as it breeds based on food abundance and temperatures during the laying season. This species is generally socially monogamous, but up to 8% of breeding males are polygynous

Polygyny () is a form of polygamy entailing the marriage of a man to several women. The term polygyny is from Neoclassical Greek πολυγυνία (); .

Incidence

Polygyny is more widespread in Africa than in any other continent. Some scholar ...

. Polygyny is influenced by territory: males having territories with nest boxes at least apart are more likely to be polygynous. It is suggested that this polygyny depends on the conditions during the laying season: better conditions, such as an abundance of food, allow females in polygyny who do not receive help foraging to lay more eggs.

The tree swallow has high rates of extra-pair paternity, 38% to 69% of nestlings being a product of extra-pair paternity, and 50% to 87% of broods containing at least one nestling that was the result of an extra-pair copulation. One factor that might contribute to this is that females have control over copulation, making paternity guards ineffective. This may be mitigated by more frequent copulations just before egg laying, according to a 2009 study which found that within-pair copulation attempts peaked three to one days before the first egg was laid and that more successful attempts during this period increased the share of within-pair young males had. This latter finding contradicts those of a 1993 and a 1994 study. Extra-pair paternity does not change the level of parental care the male contributes in the tree swallow. A significant number of extra-pair fathers may be floaters (those present at breeding grounds that presumably do not breed). A 2001 study found that out of 35 extra-pair nestlings, 25 were sired by local residents, three by residents of nearby sites, and seven by male floaters. In the tree swallow, floating thus helps males in good condition produce more chicks, while allowing males in bad condition to be successful by investing in parental care. There is also a significant population of female floaters; a 1985 study estimated that around 23% to 27% of females were floaters, of which about 47% to 79% were subadults.

Why females engage in extra-pair copulation and how they choose extra-pair mates is controversial. One theory, called the genetic compatibility hypothesis, states that increased offspring fitness results from increased

The tree swallow has high rates of extra-pair paternity, 38% to 69% of nestlings being a product of extra-pair paternity, and 50% to 87% of broods containing at least one nestling that was the result of an extra-pair copulation. One factor that might contribute to this is that females have control over copulation, making paternity guards ineffective. This may be mitigated by more frequent copulations just before egg laying, according to a 2009 study which found that within-pair copulation attempts peaked three to one days before the first egg was laid and that more successful attempts during this period increased the share of within-pair young males had. This latter finding contradicts those of a 1993 and a 1994 study. Extra-pair paternity does not change the level of parental care the male contributes in the tree swallow. A significant number of extra-pair fathers may be floaters (those present at breeding grounds that presumably do not breed). A 2001 study found that out of 35 extra-pair nestlings, 25 were sired by local residents, three by residents of nearby sites, and seven by male floaters. In the tree swallow, floating thus helps males in good condition produce more chicks, while allowing males in bad condition to be successful by investing in parental care. There is also a significant population of female floaters; a 1985 study estimated that around 23% to 27% of females were floaters, of which about 47% to 79% were subadults.

Why females engage in extra-pair copulation and how they choose extra-pair mates is controversial. One theory, called the genetic compatibility hypothesis, states that increased offspring fitness results from increased heterozygosity

Zygosity (the noun, zygote, is from the Greek "yoked," from "yoke") () is the degree to which both copies of a chromosome or gene have the same genetic sequence. In other words, it is the degree of similarity of the alleles in an organism.

Mos ...

, and thus that female tree swallows would prefer to mate with males that are less genetically similar to them. Females may also choose sperm after copulation to ensure a compatible mate. In support of this theory, a 2007 study found that extra-pair offspring were more heterozygous than within-pair offspring. However, a 2005 paper discovered a slight negative correlation between a pair's genetic similarity and the proportion of extra-pair young in their nest. The good genes theory says that females choose extra-pair males based on the quality of their genes. This would explain why some tree swallows do not have any extra-pair young, whereas others do. However, most studies have not found phenotypic

In genetics, the phenotype () is the set of observable characteristics or traits of an organism. The term covers the organism's morphology (physical form and structure), its developmental processes, its biochemical and physiological propert ...

differences between extra-pair and within-pair males (although a 2007 study did find that older males with brighter plumage were more likely to mate outside of the pair bond). Additionally, according to a 2017 thesis, extra-pair offspring are no more likely to join their natal population than within-pair offspring. Another theory suggests that extra-pair paternity is context dependent, with extra-pair young outperforming within-pair young in certain situations, and underperforming in other environments. A 2017 dissertation, for example, found that extra-pair young were larger, heavier, and longer-winged than within-pair young when both were exposed to predator mounts, while within-pair young were heavier than extra-pair young when they were shown non-predator mounts. This thesis also found that within-pair young outperformed extra-pair young in terms of life-time fitness when they were raised in less-variable environments, suggesting that extra-pair offspring have less developmental plasticity than within-pair offspring. A 2018 study weakly supported this context dependent hypothesis, finding that extra-pair offspring were more likely to fledge than within-pair offspring in experimentally enlarged broods; however, neither telomere

A telomere (; ) is a region of repetitive nucleotide sequences associated with specialized proteins at the ends of linear chromosomes (see #Sequences, Sequences). Telomeres are a widespread genetic feature most commonly found in eukaryotes. In ...

length (a correlate of survival and reproductive success) nor size 12 days after hatching were significantly different among these young, and no significant differences between the two types were found in non-enlarged broods.

Studies attempting to prove the adaptability of extra-pair paternity for females have been criticized for the lack of positive effect that increased offspring fitness would have when compared with the potential cost of decreased fitness for the female, such as increased predation from searching for mates. Thus, theories based on the non-adaptivity of extra-pair paternity for females have been postulated. These theories are based on genetic constraint, where an allele resulting in a maladaptive behavior is maintained because it also contributes to a beneficial phenotype. The theory of intersexual antagonistic pleiotropy says that strong selection for extra-pair paternity in males (as seen in this bird) overrides the weak selection against extra-pair paternity in females. The hypothesis of intrasexual antagonistic pleiotropy, meanwhile, argues that extra-pair paternity is present because the genes regulating it have pleiotropic effects on aspects of female fitness, like within-pair copulation rate.

Feeding

The tree swallow forages up to above the ground singly or in groups. Its flight is a mix of flapping and gliding. During the breeding season, this is mostly within of the nest site. When it is foraging for nestlings, though, it usually goes up to from the nest, mostly staying in sight of it, and forages at a height up to . As well as being caught in flight, insects are sometimes taken from the ground, water, vegetation, and vertical surfaces. The tree swallow eats mostly insects, with some mollusks, spiders, and fruit. In North America, flies make up about 40% of the diet, supplemented with beetles and ants. Otherwise, the diet is about 90% flies. The insects taken are a mix of aquatic and terrestrial organisms; the former are an important source of omega-3 highly unsaturated fatty acids. This is because, although the tree swallow can convert the precursorα-Linolenic acid

α-Linolenic acid, also known as ''alpha''-linolenic acid (ALA) (from Greek ''alpha'' denoting "first" and ''linon'' meaning flax), is an ''n''−3, or omega-3, essential fatty acid. ALA is found in many seeds and oils, including flaxseed, ...

into highly unsaturated fatty acids like docosahexaenoic acid

Docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) is an omega−3 fatty acid that is an important component of the human brain, cerebral cortex, skin, and retina. It is given the fatty acid notation 22:6(''n''−3). It can be synthesized from alpha-linolenic acid or ...

, it cannot do so in the quantities needed. The seed and berry food is mainly from the genus ''Myrica

''Myrica'' is a genus of about 35–50 species of small trees and shrubs in the family Myricaceae, order Fagales. The genus has a wide distribution, including Africa, Asia, Europe, North America, and South America, and missing only from Antar ...

'', which is mainly taken in all four of the Northern Hemisphere seasons except summer. Crustaceans were also found to be important in the wintering diet in a study on Long Island, New York

Long Island is a densely populated continental island in southeastern New York (state), New York state, extending into the Atlantic Ocean. It constitutes a significant share of the New York metropolitan area in both population and land are ...

.

Both sexes feed the nestlings (although the male feeds the chicks less than the females) resulting in about 10 to 20 feedings per hour. The parents often use the chirp call to stimulate nestlings to beg. This is used more frequently with younger chicks, as they beg less than older chicks when the parent arrives with food but does not call. The likelihood of begging in the absence of parents also increases with age. The hatching order affects how much a chick is fed; last-hatched nestlings (in cases where hatching is asynchronous) are likely fed less than those hatched earlier. Nestlings closer to the entrance of the nest are also more likely to be fed, as are those who beg first and more frequently. The overall rate at which a brood is fed also increases with more begging. The diet itself is composed mostly of insects, those in the orders Diptera

Flies are insects of the order Diptera, the name being derived from the Greek δι- ''di-'' "two", and πτερόν ''pteron'' "wing". Insects of this order use only a single pair of wings to fly, the hindwings having evolved into advance ...

, Hemiptera

Hemiptera (; ) is an order of insects, commonly called true bugs, comprising more than 80,000 species within groups such as the cicadas, aphids, planthoppers, leafhoppers, assassin bugs, bed bugs, and shield bugs. They range in size from ...

, and Odonata

Odonata is an order of predatory flying insects that includes the dragonflies and damselflies (as well as the '' Epiophlebia'' damsel-dragonflies). The two major groups are distinguished with dragonflies (Anisoptera) usually being bulkier with ...

making up most of the diet. These insects are mostly up to in size, but sometimes are up to in length. In nests near lakes acidified by humans, calcium supplements, primarily fish bones, crayfish exoskeleton

An exoskeleton () . is a skeleton that is on the exterior of an animal in the form of hardened integument, which both supports the body's shape and protects the internal organs, in contrast to an internal endoskeleton (e.g. human skeleton, that ...

s, clam shells, and the shells of bird eggs, are harder to find. This forces the adult tree swallow to travel further than usual—sometimes up to away from the nest—to get these calcium supplements.

Survival

The tree swallow has an average lifespan of 2.7 years and a maximum of 12 years. About 79% of individuals do not survive their first year, and those that do face an annual mortality rate of 40% to 60%. Most deaths are likely the result of cold weather, which reduces insect availability, leading to starvation. Lifespan is associated with telomere length: a 2005 study that used return rates (to the breeding site of the previous year) as a proxy for survival found that those with the longest telomeres at one year of age had a predicted lifespan of 3.5 years, compared to the 1.2 years for those with the shortest telomeres. Whether short telomeres cause a reduction in fitness or are simply an indicator of it is unknown. Regardless, a 2016 thesis found that measures of condition were positively correlated with telomere length. Males also generally had longer telomeres than females, as did smaller-winged birds. Individuals with shorter telomeres may compensate for potential losses in fitness by increasing reproductive effort, whereas those with longer telomeres may decrease their investment, as evidenced by the smaller proportion of chicks females with longer telomeres fledged. Telomere length is highly heritable, and is especially dependent on that of the mother.Predation

The tree swallow is susceptible to a wide range of predators. Eggs, nestlings, and adults in the nest fall victim to black rat snakes,American crow

The American crow (''Corvus brachyrhynchos'') is a large passerine bird species of the family (biology), family Corvidae. It is a common bird found throughout much of North America. American crows are the New World counterpart to the carrion cro ...

s, American kestrel

The American kestrel (''Falco sparverius'') is the smallest and most common falcon in North America. Though it has been called the American sparrowhawk, this common name is a misnomer; the American kestrel is a true falcon, while neither th ...

s, common grackle

The common grackle (''Quiscalus quiscula'') is a species of large icterid bird found in large numbers through much of North America. First described in 1758 by Carl Linnaeus, the common grackle has three subspecies. Adult common grackles have a ...

s, northern flicker

The northern flicker or common flicker (''Colaptes auratus'') is a medium-sized bird of the woodpecker family. It is native to most of North America, parts of Central America, Cuba, and the Cayman Islands, and is one of the few woodpecker specie ...

s, chipmunk

Chipmunks are small, striped rodents of subtribe Tamiina. Chipmunks are found in North America, with the exception of the Siberian chipmunk which is found primarily in Asia.

Taxonomy and systematics

Chipmunks are classified as four genera: '' ...

s, deermice, domestic cat

The cat (''Felis catus''), also referred to as the domestic cat or house cat, is a small Domestication, domesticated carnivorous mammal. It is the only domesticated species of the family Felidae. Advances in archaeology and genetics have sh ...

s, weasel

Weasels are mammals of the genus ''Mustela'' of the family Mustelidae. The genus ''Mustela'' includes the least weasels, polecats, stoats, ferrets, and European mink. Members of this genus are small, active predators, with long and slend ...

s,Winkler, D. W.; Hallinger, K. K.; Ardia, D. R.; Robertson, R. J.; Stutchbury, B. J.; Chohen, R. R. (2011). Poole, A. F., ed. "Tree Swallow (''Tachycineta bicolor'')". ''The Birds of North America''. Ithaca, New York

Ithaca () is a city in and the county seat of Tompkins County, New York, United States. Situated on the southern shore of Cayuga Lake in the Finger Lakes region of New York (state), New York, Ithaca is the largest community in the Ithaca metrop ...

: Cornell Lab of Ornithology. American black bear

The American black bear (''Ursus americanus''), or simply black bear, is a species of medium-sized bear which is Endemism, endemic to North America. It is the continent's smallest and most widely distributed bear species. It is an omnivore, with ...

s, and raccoon

The raccoon ( or , ''Procyon lotor''), sometimes called the North American, northern or common raccoon (also spelled racoon) to distinguish it from Procyonina, other species of raccoon, is a mammal native to North America. It is the largest ...

s. While flying or perched, predators to the tree swallow include American kestrels, black-billed magpie

The black-billed magpie (''Pica hudsonia''), also known as the American magpie, is a bird in the corvid family found in the western half of North America. It is black and white, with the wings and tail showing black areas and iridescent hints ...

s, barred owl

The barred owl (''Strix varia''), also known as the northern barred owl, striped owl or, more informally, hoot owl or eight-hooter owl, is a North American large species of owl. A member of the true owl family, Strigidae, they belong to the genus ...

s, great horned owl

The great horned owl (''Bubo virginianus''), also known as the tiger owl (originally derived from early naturalists' description as the "winged tiger" or "tiger of the air") or the hoot owl, is a large owl native to the Americas. It is an extreme ...

s, merlins, peregrine falcon

The peregrine falcon (''Falco peregrinus''), also known simply as the peregrine, is a Cosmopolitan distribution, cosmopolitan bird of prey (raptor) in the family (biology), family Falconidae renowned for its speed. A large, Corvus (genus), cro ...

s, and sharp-shinned hawks. While evasive flight is the usual response to predators in free-flying swallows, mobbing behavior is common around the nest, and is directed not just towards predators, but also towards nest site competitors, who might be scared off by it. This behavior involves the swallow swarming and diving towards (but not actually striking) the intruder from around above the ground, usually giving soft ticking calls near the end and coming within about of the predator. It seems to alter the intensity of its attacks based on which predator approaches; a 1992 study found that ferrets elicited a more vigorous defense than black rat snakes, and a 2019 thesis similarly discovered that black rat snake models were dived at the least and eastern chipmunk

The eastern chipmunk (''Tamias striatus'') is a chipmunk species found in eastern North America. It is the only living member of the genus ''Tamias''.

Etymology

The name "chipmunk" probably comes from the Ojibwe word (or possibly ''ajidamoonh ...

models the most. It is suggested that the snake prompted a weaker response because defense behaviors may be less effective and more dangerous to perform against it.

Parasites

The tree swallow is vulnerable to various parasites, such as the blood parasite ''Trypanosoma

''Trypanosoma'' is a genus of kinetoplastids (class Trypanosomatidae), a monophyletic group of unicellular parasitic flagellate protozoa. Trypanosoma is part of the phylum Euglenozoa. The name is derived from the Ancient Greek ''trypano-'' (b ...

''. It is also susceptible to the flea '' Ceratophyllus idius'' and the feather mites '' Pteronyssoides tyrrelli'', '' Trouessartia'', and (likely) '' Hemialges''. It is also probably afflicted by lice of the genera '' Brueelia'' and '' Myrsidea''. There is a correlation between the number of fleas on a bird and the number of young it is caring for. This relationship is speculated to arise from an improved microclimate for fleas due to a larger clutch. Nestlings also suffer from parasites, like blow-flies of the genus '' Protocalliphora'', which results in a loss of blood by nestlings. These parasites, though, are found in a majority of nests and do not seem to have a large effect on nestlings. A study published in 1992 found that the effects of blow-fly parasitism explained only about 5.5% of the variation in nestling mass.

Immunology

In the breeding female tree swallow, humoral immunocompetence (HIC) is inversely correlated with laying date. This means that, on average, a bird that lays its eggs earlier has a stronger antibiotic response to anantigen

In immunology, an antigen (Ag) is a molecule, moiety, foreign particulate matter, or an allergen, such as pollen, that can bind to a specific antibody or T-cell receptor. The presence of antigens in the body may trigger an immune response.

...

than a bird that lays later. A tree swallow that is handicapped by wing-clipping generally has a lower HIC. These relationships could be interpreted as supporting the conclusion that a female that lays earlier acquires a higher HIC, but the authors of the study that found the correlations believed this unlikely, due to the colder temperatures near the start of the breeding season. Instead, they thought that HIC could be a measure of quality, and that a higher quality female is able to lay earlier. The authors also postulated that it is an indicator of workload, as shown by the lower HIC of handicapped birds.

Higher quality female tree swallows (as measured by laying date) are able to maintain their reproductive effort while diverting resources to fight an immune challenge. Lower quality swallows are less able to do so; a 2005 study in Ithaca, New York, found that late-laying females with an artificially enlarged brood, although able to maintain offspring quality, had lower responses to an immune challenge than those that were of higher quality or did not have an enlarged brood. Whether a female chooses to prioritize offspring quality or immunocompetence is likely related to survival probabilities; a 2005 study discovered that females with an enlarged brood in Alaska, where survival rates are lower, had weaker immune responses, but kept reproductive effort steady, whereas those in Tennessee, with higher survival rates, had a stronger response but lower quality offspring.

In the tree swallow, some components of the immune system deteriorate with age. Acquired T cell

T cells (also known as T lymphocytes) are an important part of the immune system and play a central role in the adaptive immune response. T cells can be distinguished from other lymphocytes by the presence of a T-cell receptor (TCR) on their cell ...

-mediated immunity, for example, declines with age in the female tree swallow. But, the age of a female does not affect both the acquired and innate humoral immunity

Humoral immunity is the aspect of immunity (medical), immunity that is mediated by macromolecules – including secreted antibodies, complement proteins, and certain antimicrobial peptides – located in extracellular fluids. Humoral immunity is ...

; the lack of deterioration in the former contrasts with studies on barn swallow

The barn swallow (''Hirundo rustica'') is the most widespread species of swallow in the world, occurring on all continents, with vagrants reported even in Antarctica. It is a distinctive passerine bird with blue upperparts and a long, deeply f ...

s and female collared flycatchers. Because of this immunosenescence (a decrease in immune function with age), older females infected with a disease generally visit their nest less, resulting in their nestlings growing slower. They are also likely to lose weight because of an infection.

Status

The tree swallow is considered to beleast concern

A least-concern species is a species that has been evaluated and categorized by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) as not being a focus of wildlife conservation because the specific species is still plentiful in the wil ...

by the International Union for Conservation of Nature

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) is an international organization working in the field of nature conservation and sustainable use of natural resources. Founded in 1948, IUCN has become the global authority on the stat ...

. This is due to the bird's large range of about , and its stable population, estimated to be about 20,000,000 individuals. It is protected in the US by the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918

The Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918 (MBTA), codified at (although §709 is omitted), is a United States federal law, first enacted in 1918 to implement the convention for the protection of migratory birds between the United States and Canada. ...

, and in Canada by the Migratory Birds Convention Act. In some parts of the US, the range of this swallow has extended south, likely due to changes in land use, the reintroduction of beavers, and nest boxes installed for bluebird

The bluebirds are a North American group of medium-sized, mostly insectivorous or omnivorous passerine birds in the genus ''Sialia'' of the thrush family (Turdidae). Bluebirds are one of the few thrush genera in the Americas.

Bluebirds lay an ...

s. The tree swallow is negatively impacted by the clearing of forests and the reduction of marshes, the latter reducing the habitat available for wintering. This swallow has to compete for nest sites with the common starling

The common starling (''Sturnus vulgaris''), also known simply as the starling in Great Britain and Ireland, and as European starling in North America, is a medium-sized passerine bird in the starling family, Sturnidae. It is about long and ha ...

, house sparrow

The house sparrow (''Passer domesticus'') is a bird of the Old World sparrow, sparrow family Passeridae, found in most parts of the world. It is a small bird that has a typical length of and a mass of . Females and young birds are coloured pa ...

(both introduced to North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere, Northern and Western Hemisphere, Western hemispheres. North America is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South Ameri ...

), bluebirds, and the house wren (which also destroys nests without occupying them). Acidification of lakes can force this swallow to go relatively long distances to find calcium-rich items, and can result in chicks eating plastic. Other chemicals, like pesticides and other pollutants, can become highly concentrated in eggs, and PCBs are associated with the abandonment of a pair's clutch. Contamination from oil sands mine sites can negatively affect tree swallows by increasing the presence of toxins, as measured by the activity of ethoxyresorufin-''o''-deethylase (a detoxification enzyme) in nestlings. This normally has little influence on nestling and fledging, though extreme weather can reveal the effects: a 2006 study found that nestlings from wetlands most polluted by oil sands

Oil sands are a type of unconventional petroleum deposit. They are either loose sands, or partially consolidated sandstone containing a naturally occurring mixture of sand, clay, and water, soaked with bitumen (a dense and extremely viscous ...

processing material were more than 10 times more likely to die than those from a control site during periods of synchronized cold temperatures and heavy rainfall, compared to the lack of difference in mortality between the groups when the weather was less extreme. A 2019 paper, however, found that increased precipitation caused a similar decline in hatching and nestling success for nestlings both near and far from oil sands sites. In another study, birds exposed to mercury fledged, on average, one less chick than those not, an effect amplified by warm weather. In addition, cold weather events can rapidly reduce the availability of aerial insect prey, and in some populations with advancing reproduction may result in reduced offspring survival.

References

Notes

Citations

External links

{{Use dmy dates, date=July 2019 tree swallow tree swallow Birds of North America tree swallow tree swallow